New Close Binary Systems from the SDSS-I (Data Release Five) and the Search for Magnetic Wh

a r X i v :0704.0789v 1 [a s t r o -p h ] 5 A p r 2007

Draft version February 1,2008

Preprint typeset using L A T E X style emulateapj v.10/09/06

NEW CLOSE BINARY SYSTEMS FROM THE SDSS–I (DATA RELEASE FIVE)AND THE SEARCH FOR

MAGNETIC WHITE DWARFS IN CATACLYSMIC VARIABLE PROGENITOR SYSTEMS

Nicole M.Silvestri 1,Mara P.Lemagie 1,Suzanne L.Hawley 1,Andrew A.West 2,Gary D.Schmidt 3,James Liebert 3,Paula Szkody 1,Lee Mannikko 1,Michael A.Wolfe 1,J.C.Barentine 4,Howard J.Brewington 4,Michael Harvanek 4,Jurik Krzesinski 5,Dan Long 4,Donald P.Schneider 6,and Stephanie A.Snedden 4

(Received 2007February 9)

Draft version February 1,2008

ABSTRACT

We present the latest catalog of more than 1200spectroscopically–selected close binary systems observed with the Sloan Digital Sky Survey through Data Release Five.We use the catalog to search for magnetic white dwarfs in cataclysmic variable progenitor systems.Given that approximately 25%of cataclysmic variables contain a magnetic white dwarf,and that our large sample of close binary systems should contain many progenitors of cataclysmic variables,it is quite surprising that we ?nd only two potential magnetic white dwarfs in this sample.The candidate magnetic white dwarfs,if con?rmed,would possess relatively low magnetic ?eld strengths (B WD <10MG)that are similar to those of intermediate–Polars but are much less than the average ?eld strength of the current Polar population.Additional observations of these systems are required to de?nitively cast the white dwarfs as magnetic.Even if these two systems prove to be the ?rst evidence of detached magnetic white dwarf +M dwarf binaries,there is still a large disparity between the properties of the presently known cataclysmic variable population and the presumed close binary progenitors.

Subject headings:binaries:close —cataclysmic variables —stars:low-mass —stars:magnetic ?elds

—stars:white dwarfs

1.INTRODUCTION

The evolution of stars in close binary systems leads to interesting stellar end-products such as cataclysmic variables (CVs),Type 1a supernovae,and helium–core white dwarfs (WDs).The period in which an evolved star ascends the asymptotic giant branch and engulfs a close companion in its evolving atmosphere,referred to as the common envelope phase,probably plays a dominant role in the evolution of these systems and as yet is poorly understood.The angular momentum of the system is believed to aid in the eventual ejec-tion of the common envelope to reveal the remnant WD and close companion.After the common envelope has been ejected,gravitational and magnetic braking work to decrease the orbital separation of the detached system (de Kool &Ritter 1993).This orbital evolution contin-ues through to the CV phase.The e?ect of the common envelope on the secondary star in these systems is an-other aspect of close binary evolution which is not well characterized.Plausible scenarios for the secondary com-1

Department of Astronomy,University of Washington,Box 351580,Seattle,W A 98195,USA;nms@https://www.360docs.net/doc/2410155615.html,,mlemagie@https://www.360docs.net/doc/2410155615.html,,slh@https://www.360docs.net/doc/2410155615.html,,szkody@https://www.360docs.net/doc/2410155615.html,,leeman@https://www.360docs.net/doc/2410155615.html,,maw2323@https://www.360docs.net/doc/2410155615.html,.

2Astronomy Department,601Campbell Hall,University of California,Berkeley,CA 94720,USA;awest@https://www.360docs.net/doc/2410155615.html, 3Department of Astronomy and Steward Observatory,Univer-sity of Arizona,Tucson,AZ 85721,USA;schmidt@https://www.360docs.net/doc/2410155615.html,,jliebert@https://www.360docs.net/doc/2410155615.html,.

4Apache Point Observatory,P.O.Box 59,Sunspot,NM 88349,USA;jcb@https://www.360docs.net/doc/2410155615.html,,hbrewington@https://www.360docs.net/doc/2410155615.html,,harvanek@https://www.360docs.net/doc/2410155615.html,,long@https://www.360docs.net/doc/2410155615.html,,sned-den@https://www.360docs.net/doc/2410155615.html,.

5Mt.Suhora Observatory,Cracow Pedagogical University,ul.Podchorazych 2,30-084Cracow,Poland;jurek@https://www.360docs.net/doc/2410155615.html,.6Department of Astronomy,Penn State University,PA 16802USA;dps@https://www.360docs.net/doc/2410155615.html,

panion range from accreting as much as 90%of its mass during this phase to escaping relatively unscathed from the common envelope,emerging in the same state as it entered (see Livio 1996,and references therein).

Recently,studies of close binary systems with WD companions (see for example Farihi et al.2005b,a;Pourbaix et al.2005;Silvestri et al.2006)have revealed yet another puzzling property of these systems.None of the WDs in close binary systems with low–mass,main se-quence companions appear to be magnetic (Liebert et al.2005).Close,non–interacting binary systems with WD primaries are quite common and are believed to be the direct progenitors to CVs (Langer et al.2000,and ref-erences therein).Magnetic WDs,stellar remnants with magnetic ?elds in excess of ~1MG,comprise only a small percentage of the isolated WD population (~2%,Liebert et al.2005).Note that the 2%magnetic WD fraction applies to magnitude–limited samples like the Palomar–Green (Liebert et al.1988).However,the same paper notes that magnetic WDs may generally have smaller radii than non–magnetic white dwarfs,due to higher mass.In a given volume,the density of mag-netic WDs may be ~10%of all WDs (Liebert et al.2003).The SDSS is also a magnitude limited sample so we assume a similar expected value for the close bi-naries.Our sample (as discussed in detail in §2)con-tains 1253potential close binary systems.Therefore we assume approximately 24of these binaries to harbor a magnetic WD.Possible implications of the small radii for magnetic WD +main sequence pairs will be dis-cussed in §5.However,more than 25%of the WDs in the currently identi?ed CV population are classi?ed as magnetic,and many have magnetic ?elds in excess of 10MG (see Wickramasinghe &Ferrario 2000).

Holberg et al.(2002)have compiled a list of 109known WDs within 20pc (and complete to within 13pc)that

2Silvestri et al.

have nearly complete information about the presence of a companion.Of the109WDs in their sample, 19±4have nondegenerate companions.Table7in Kawka et al.(2007)lists all known magnetic WDs as of June2006.Of the magnetic WDs listed in their table, 149have?eld strengths identi?able in SDSS-resolution spectra(B W D≥3MG).If the magnetic WDs in the Kawka et al.(2007)sample are assumed to be drawn from a similar sample then28±5.3would be expected to have nondegenerate companions,and yet none have been detected in the Kawka et al.(2007)sample.This is nearly a5σde?cit in magnetic WDs with nondegenerate companions.

Holberg&Magargal(2005)looked at the2MASS JHK s photometry of347WDs in the Palomar–Green sample.Of the347WDs,254had reliable infrared mea-surements of at least J magnitude.Of these,59had excesses indicative of a nondegenerate companion and another15showed“probable”excesses(Liebert et al. 2005).This gives a WD+dM fraction of23%(de?nite excess)and29%(including all probable excesses).If the Kawka et al.(2007)sample had the same frequency of of nondegenerate companions as the Palomar–Green sam-ple,they should have34and43,respectively.This is nearly as6σde?cit!

This apparent lack of magnetic WDs with main se-quence companions is not restricted to studies of close binaries.Low resolution spectroscopic surveys of more than500common proper motion binary systems dis-covered by Luyten et al.(1964);Luyten(1968,1972) and Giclas et al.(1971,1978)revealed no magnetic WDs paired with main sequence companions in these wide pairs(Smith1997;Silvestri et al.2005).In addition, Schmidt et al.(2003)and Vanlandingham et al.(2005) have identi?ed over100magnetic WDs in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey(SDSS,Gunn et al.1998;York et al. 2000;Stoughton et al.2002;Pier et al.2003;Gunn et al. 2006).As discussed by Liebert et al.(2005),this implies essentially no overlap between the close binary and mag-netic WD samples.

A new class of short–period,low accretion–rate polars (LARPS)identi?ed by Schmidt et al.(2005b)may ex-plain,in part,these“missing”magnetic WD systems. In these systems,the donor star has not?lled its Roche Lobe.The WD accretes material by capturing the stel-lar wind of the secondary.These CVs have accretion rates that are less than1%of accretion rates normally associated with CVs.The discovery of these systems sheds some light on the whereabouts of magnetic WD binaries,though as Schmidt et al.(2005b)point out, this still does not explain the apparent lack of long–period,detached magnetic WD systems.Thought to be the?rst detached binary with a magnetic WD,SDSS J121209.31+013627.7,a magnetic WD with a proba-ble brown dwarf(L dwarf)companion(Schmidt et al. 2005a)has been shown to be one of these LARP systems (Debes et al.2006;Koen&Maxted2006;Burleigh).To date,magnetic WDs have only been found as isolated ob-jects,in binaries with another degenerate object(WD or neutron star companion),or in CVs;none have a clearly main sequence companion.

In this study,we investigate a new large sample of close binary systems in an e?ort to uncover these“missing”magnetic WD binary systems.The sample comprises more than1200close binary systems containing a WD and main sequence star drawn from the SDSS,many of which were originally presented in Silvestri et al.(2006, hereafter,S06).We?nd that only two of the WDs in these pairs appear to be magnetic.Even if con?rmed, neither of these WDs has magnetic?eld strength compa-rable to those observed in the majority of magnetic(Po-lar)CV systems.We con?rm that the current CV and close binary populations are indeed disparate and show that more work is necessary to unravel this mystery.

In§2we introduce the catalog of close binary sys-tems through the public SDSS Data Release Five(DR5; Adelman-McCarthy et al.2007).We discuss our anal-ysis techniques in§3and we present our results in§2. Our discussion and concluding remarks are given in§5 and§6,respectively.

2.THE SDSS CLOSE BINARY CATALOG THROUGH DR5 The combined properties of the majority of close binaries in this paper are discussed in detail in Raymond et al.(2003)and S06.The S06cata-log was based on a preliminary list of spectroscopic plates released internally to the collaboration and as such does not include objects from~200plates re-leased with the?nal public Data Release Four(DR4; Adelman-McCarthy et al.2006).The additional systems from both DR4and DR5do not change the overall re-sults from analysis performed in S06,hence no new anal-ysis is presented here.We include this list in its en-tirety to complete the DR4catalog introduced by S06 and add over300new systems from the now public DR5 (Adelman-McCarthy et al.2007).This completes the catalog of close binary systems with a WD identi?ed through SDSS–I.More close binaries are being targeted in the SDSS–II(SEGUE)survey which will continue to increase the sample through2008.

The list of1253potential close binary systems given in Table1includes objects from all plates released with the public DR5,thereby superseding the S06DR4cat-alog.The technique used to search for these objects is the same as described in S06.As with that study,we do not include systems with low signal-to-noise ratios (S/N<5)and do not search for systems with non–DA WDs.We emphasize that our sample is not complete (or bias free)due to the selection e?ects imposed by our detection methods and due to the sporadic targeting of these objects in the SDSS spectroscopic survey as dis-cussed in S06.Thus,our sample represents primarily bright,DA WD+M dwarf binary systems.As evidenced by Smolˇc i′c et al.(2004),there are potentially thousands more WD+M dwarf binaries observed photometrically in the SDSS but not targeted for spectroscopy.Our cat-alog represents an interesting and statistically signi?cant sampling of these systems,the properties of which can be used to test models of close binary evolution(see Politano&Weiler2006,for example).

The list of plate numbers from which this sample has been drawn can be found at

https://www.360docs.net/doc/2410155615.html,/DR5/data/spectro/1d

Magnetic WDs in CV Progenitors

3

Fig.

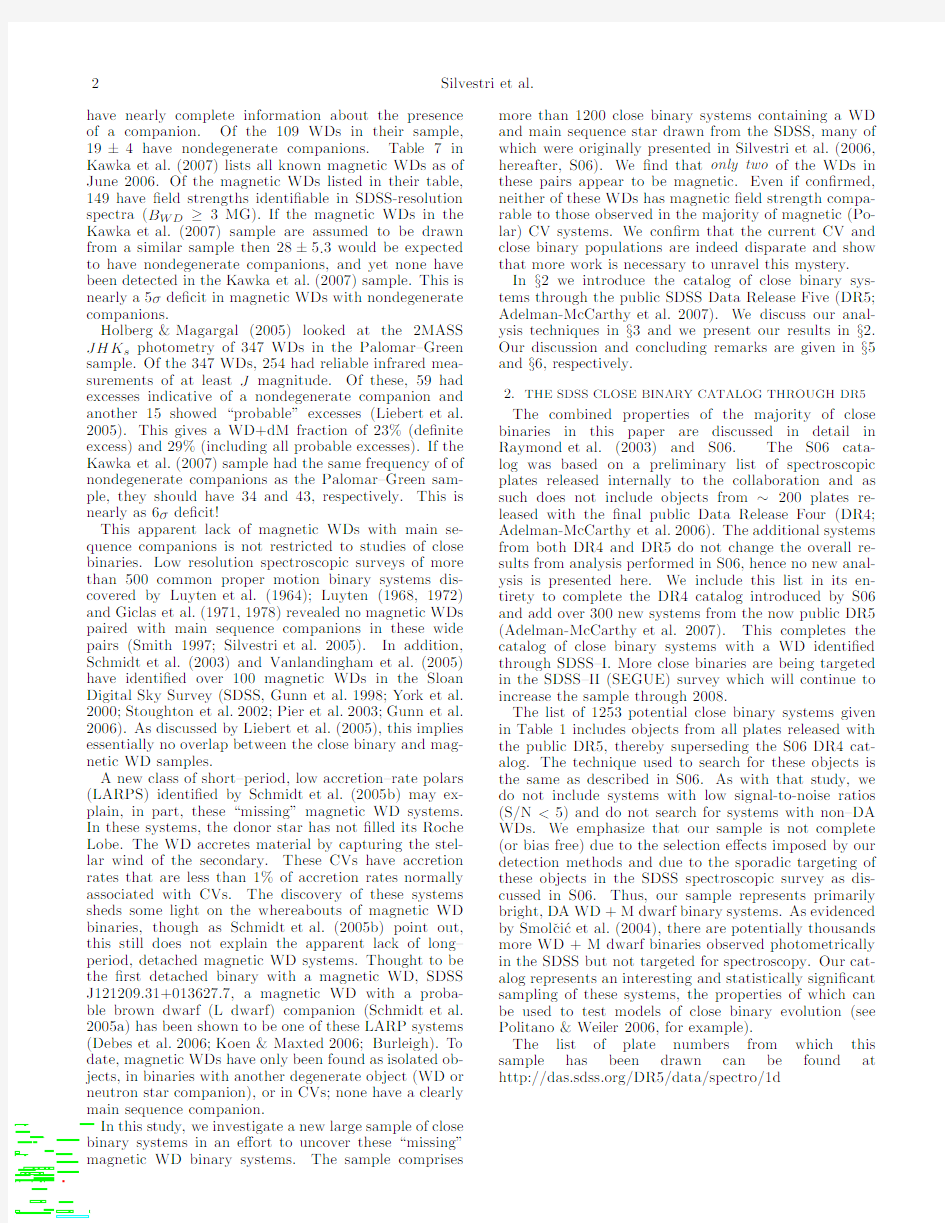

1.—Example of an M dwarf with excess blue ?ux (:+dM)from Table 1.The companion is seen as little more than excess blue ?ux in the M dwarf spectrum.Follow-up spectroscopy to resolve the companion is necessary to rule out the presence of a magnetic WD.Note:spectrum has been boxcar smoothed with a ?lter size of seven.

etc.)that are not part of the original SDSS–I survey.The ?rst four columns of Table 1list the SDSS identi-?er,the plate number,?ber identi?cation,and modi?ed Julian date (MJD)of the observation,followed by the spectral type of the components (determined visually)where Sp1represents the blue object and Sp2is the red object.Columns 6and 7give the J2000coordinates (in decimal degrees)for the object.The next 15columns give the ugriz PSF photometry (Fukugita et al.1996;Hogg et al.2001;Ivezi′c et al.2004;Smith et al.2002;Tucker et al.2006),photometric uncertainties (σugriz ),and reddening (A ugriz ).The magnitudes are not cor-rected for Galactic extinction.Column 23lists the SDSS data release in which the object was discovered as well as additional references in the literature.Additional notes for the objects are listed in column 24.

The objects identi?ed in Table 1as :+dM are likely M dwarfs with faint,cool WD companions.The dis-covery spectra for these objects reveal little more than excess blue ?ux at wavelengths shorter than 5000?A ,as shown in Figure 1.It is possible that some of these pairs may contain a magnetic WD;however,much higher S/N spectra are required to adequately characterize the blue component of these systems.

Similarly,the thirty nine objects identi?ed as WD+:or WD+:e (see Figure 8of S06)have either some ex-cess ?ux in the red or have emission at Balmer wave-lengths indicative of a faint,active,low–mass or sub–stellar companion.The companion to the magnetic WD in Schmidt et al.(2005a)was ?rst identi?ed by emission at H αin the SDSS discovery spectrum.Other than the emission at H αthis object had no other optical signa-ture of a companion.We are performing followup obser-vations using the ARC 3.5–m telescope at Apache Point Observatory to obtain radial velocities and near–infrared imaging of these objects to measure the orbital periods and categorize the probable low–mass companion’s spec-tral type.We have already con?rmed that none of these systems contain a magnetic WD.

3.THE SEARCH FOR MAGNETIC WDS

Schmidt et al.(2003)and Vanlandingham et al.(2005)demonstrated that magnetic WDs with ?eld strengths as low as ~3MG can be e?ectively measured using SDSS spectra.Visual inspection of the systems in our sample reveals no obvious magnetic WDs in spectra with good S/N (>10)(Lemagie et al.2004).Most are classical WD +M dwarf close binaries as shown in Figure 2.Of interest are the lower quality spectra,where the features

Fig. 2.—A Typical WD+dM System:SDSS J140723.03+003841.7,the superposition of a DA (hydrogen atmosphere)WD and a M4red dwarf star.H αemission is visible in many of these systems and is a result of chromspheric activity on the surface of the M star,perhaps enhanced due to the in?uence of the WD.The lack of broad Zeeman absorption features in the hydrogen lines indicates that the magnetic ?eld strength of the WD is very low (compare with Figure 4).

of the WD are less obvious because of low S/N and/or contamination by the spectral features of the close M dwarf companion.These e?ects make it di?cult to iden-tify small magnetic ?eld e?ects on the WD absorption features.Thus,relatively low magnetic ?elds (B WD <10MG)are not easily recognized in the combined spectrum.

3.1.The Simulated Magnetic Binary Systems

Given the di?culties associated with visually identi-fying features in these systems,we developed a method to search for the characteristic Zeeman splitting of the DA WD absorption features that is also sensitive to low magnetic ?eld WDs.We use a program that attempts to match absorption features in magnetic DA WD mod-els (see Kemic 1974b,a;Schmidt et al.2003,and refer-ences therein for details on the models)through an it-erative method of smoothing and searching the stellar spectrum.To develop a robust program to search for magnetic WDs in close binaries we ?rst tested our pro-gram on WDs of known magnetic ?eld strength.We used the magnetic DA WDs with ?eld strengths between 1.5MG ≤B WD ≤30MG from Schmidt et al.(2003)and Vanlandingham et al.(2005)as our test sample.We then constructed model spectra at every half–MG be-tween 1.5MG ≤B WD ≤30MG,each with magnetic ?eld inclinations of 30?,60?,and 90?.The program was able to match (using a χ2minimization)the magnetic ?eld strength of each of the magnetic WDs to within ±5MG of the value quoted in Schmidt et al.(2003).

We then constructed a sample of simulated SDSS spec-tra of magnetic binary systems.The simulated binaries were created by adding the spectra of magnetic WDs used in our initial test from Schmidt et al.(2003)and Vanlandingham et al.(2005)to the M star templates of Hawley et al.(2002).We ?rst normalized all spectra at a wavelength of 6500?A ,and then combined them with ?ux ratios of 1:4(WD:M dwarf)to 4:1to replicate the range of ?ux ratios observed in the close binary sample (see Figure 3)7.This created a sample of binaries which represent the average brightness and spectral type dis-tribution of the majority of the systems in Table 1(i.e.DA WDs and M0–M5dwarfs).

Figure 4is an example of one of the simulated magnetic

7

Note that 6500?A is the midpoint of the SDSS combined blue and red spectra,as plotted in Figure 3.In reality the SDSS spectra extend to below 3900?A and to nearly 10000?A .

4Silvestri et

al. Fig.3.—Comparison of simulated and observed pre–cataclysmic

variable(PCV)systems.Left Hand

Column:Simulated magnetic PCVs produced by adding WD spectra from Schmidt et al.(2003) to M dwarf spectra from Hawley et al.(2002)with brightness ratios as speci?ed at6500?A.Right Hand Column:Observed PCVs from Silvestri et al.(2006).

Fig.4.—A Simulated System.Top Left Panel:A13MG mag-netic WD from Schmidt et al.(2003).Top Right Panel:Template M4dwarf star from Hawley et al.(2002).Bottom Panel:addition of the magnetic WD and template M dwarf,assuming equal?ux density at6500?A.

binary systems.The upper left hand panel is the SDSS spectrum of a13MG magnetic WD,the upper right hand panel is the spectrum of a template M4dwarf star. The bottom panel is the addition(superposition)of the two spectra with a?ux ratio of1:1at6500?A.As shown, this WD with a relatively moderate magnetic?eld,when combined with the spectrum of an average M dwarf,is clearly detected at the resolution of the SDSS spectra(R ~1800).

3.2.Results from the Simulated Systems

We found that detecting the presence of a WD mag-netic?eld depends most strongly on the spectral type and relative?ux of the M dwarf companion.Due to the selection e?ects of the close binary sample(see S06for details),the majority of the M dwarfs in these binaries have spectral sub–types between M0–M4.In SDSS spec-tra,early M dwarf spectral types contribute nearly as much?ux in the blue portion of the spectrum(4000–7000?A)as they do in the red(7000–10000?A).The spectrum of the blue magnetic WD is then superimposed onto the numerous blue molecular features of the M dwarf.This makes the small absorption features stemming from the subtle in?uence of a weak magnetic?eld di?cult to de-tect.

We plot a subset of our simulated pairs to demon-strate some of these issues in Figure5and Figure6. In Figure5we selected four early–type template M dwarfs(WD+M0=open squares,WD+M1=open circles,WD+M2=open triangles,and WD+M3= crosses)from Hawley et al.(2002)and added them to a range of magnetic WDs from Schmidt et al.(2003)and Vanlandingham et al.(2005).The quoted value from

Fig. 5.—Left Hand Panel:Subset of the simulated binary sys-tems comprised of early–M dwarfs from Hawley et al.(2002)paired with magnetic WDs and literature values from Schmidt et al. (2003)and Vanlandingham et al.(2005)with B WD≤10MG. Right Hand Panel:Same M dwarfs from Left Panel paired with magnetic WDs with B WD≥10MG.The measured values are from our program.In both panels,the?lled triangles represent single WDs,open squares are WD+M0,open circles are WD+M1, open triangles are WD+M2,and crosses are WD+M3.The solid line has a slope of one and the dashed lines are±5MG.Refer to §3.2of the text for details.

Fig. 6.—Left Hand Panel:Subset of the simulated binary sys-tems comprised of late-M dwarfs from Hawley et al.(2002)paired with magnetic WDs and literature values from Schmidt et al. (2003)and Vanlandingham et al.(2005)with B WD≤10MG. Right Hand Panel:Same M dwarfs from Left Panel paired with magnetic WDs with B WD≥10MG.The measured values are from our program.In both panels,the?lled triangles represent single WDs,open squares are WD+M4,open circles are WD+M5, open triangles are WD+M6,and crosses are WD+M7.The solid line has a slope of one and the dashed lines are±5MG.Refer to §3.2of the text for details.

Schmidt et al.(2003)for the magnetic?eld strength of each of these WDs represents the“Literature B WD”value on the x–axis.The“Measured B WD”is the value returned by the program.Values returned by the pro-gram that matched the literature values fall along the solid line.The dashed lines represent±5MG of the literature value.Figure6is the same except we add the same magnetic WDs to later–type M dwarf tem-plates(WD+M4=open squares,WD+M5=open cir-cles,WD+M6=open triangles,and WD+M7=crosses). The solid triangles represent the tests using the isolated WD spectra.

In both Figures5and6the program returns the value of the single WD to within~±2MG for the large ma-jority of the systems.The uncertainty of the?tted value and the spread in values increases for magnetic?elds of3 MG or less when the magnetic WD is paired with an M dwarf of comparable brightness.The?ux minima associ-ated with the Zeeman features for such low?eld strengths are just barely resolvable in high S/N spectra of isolated SDSS WDs(see Schmidt et al.2003).The added com-plexity of the M dwarf molecular features and the gen-erally lower S/N spectra make it di?cult to measure the magnetic features for low magnetic?eld strengths.How-

Magnetic WDs in CV Progenitors

5

Fig.7.—Here,we plot the ?ux ratio (WD ?ux/M dwarf

[dM])versus the di?erence between the literature value (from Schmidt et al.2003;Vanlandingham et al.2005)of the magnetic ?eld strength (B Lit )and the measured magnetic ?eld strength (B Mea )as determined from the WD H α(top panel),H β(center panel),and H γ(bottom panel)absorption features.Error bars are from the χ2?t.Refer to §3.2of the text for details.

ever,WDs with magnetic ?elds ≥4MG were easily mea-sured at all M dwarf spectral types.

In both Figures,the largest discrepancies between the literature and measured values occur when the WD’s magnetic ?eld is between 12MG ≤B WD ≤18MG;this is true when the WD is paired with both early–and late–type M dwarfs.Inspection of the model results in-dicates that at these ?eld strengths,the Zeeman features overlap on wavelengths with strong M dwarf molecular features,causing confusion in the identi?cation of the fea-ture.However,WD spectra with these and larger ?eld strengths are quite easily recognized visually so we are con?dent that no systems with ≥10MG have escaped notice,though the exact value of the ?eld strength would be more uncertain.

In Figure 7,we demonstrate the e?ect of the relative ?ux ratio (WD:M dwarf [dM])on the identi?cation of the magnetic ?eld strength of WDs in the simulated binary sample.The Figure gives the relative ?ux ratio versus the di?erence between the magnetic ?elds quoted in the literature and those returned by the program.We use the same B WD distribution in Figure 7as used in Fig-ure 5and Figure 6.The literature values (B Lit )are from Schmidt et al.(2003)and Vanlandingham et al.(2005).The three panels show ratios determined using H α(top),H β(center),and H γ(bottom).The program consis-tently returns the quoted B WD as determined from H βuntil the ?ux contribution from the M dwarf is nearly double the ?ux contribution from the WD.The program returns the magnetic ?eld from the H αfeature to within ±5MG until the ?ux contribution from the M dwarf is nearly 1.5×the ?ux from the WD.The B WD as mea-sured by H γis consistently 15–25MG larger than the B WD value in the literature at any ?ux ratio.The con-tribution of a relatively clean spectral region near H β,to-gether with the fairly strong Zeeman signal at this wave-length makes H βa reliable indicator of WD magnetic ?eld strength for binaries with ?ux ratios up to 1:2.

4.TWO POSSIBLE MAGNETIC WDS IN THE DR5CLOSE

BINARY SAMPLE

The method employed by S06to split the binary sys-tem into its two component spectra through an itera-tive method of ?tting and subtracting WD model at-mospheres and template M dwarf spectra was not used on these objects.There are no obviously strong mag-netic WDs in the sample,suggesting that any possibly magnetic WDs must possess relatively weak ?elds.The

Fig.8.—Two potential magnetic DA WD +M dwarf pairs as identi?ed by our program.The tentative magnetic ?eld strengths are 8MG ±5MG (top)and 3MG +5/?3MG (bottom)as deter-mined from the H αand H βWD absorption features.

subsequent ?tting and subtraction of model WDs and template M dwarfs adds noise to the spectrum which would make detection of an already weak magnetic ?eld even more di?cult.Also,we would be subtracting a non–magnetic WD model from the spectrum of a poten-tially magnetic WD in our attempt to improve the M dwarf template ?t.This adds absorption features where none actually exist,further corrupting the WD spectrum.Given these complications,we chose to work with the original composite SDSS discovery spectra.

Table 2lists the properties of the only two close bi-nary systems ?agged by our program as containing po-tential magnetic WDs:SDSS J082828.18+471737.9and SDSS J125250.03?020608.1.The ?rst four columns are the same as for Table 1,followed by the R.A.and Decl.(J2000coordinates).The tentative magnetic ?eld strengths (in MG),inclination of the WD magnetic ?eld to the line of sight (in degrees)and the spectral types of the components are listed in Columns 7–9.For each of these systems the magnetic ?eld strength estimate is based upon a match to at least two of the three Balmer features (H α,H β,and/or H γ)to within ±5MG of the model minima.The last six columns give the ugriz pho-tometry and the SDSS data release for the objects.Refer to Table 1for a full listing of photometric errors,redden-ing and alternate literature sources.

Figure 8displays the spectra of these two objects,which have relatively low S/N (~5at H α)The iden-ti?cation of the magnetic ?eld strength was determined from the H αand H βfeatures in each spectrum,which upon closer inspection may show some Zeeman splitting.The best ?t model for SDSS J082828.18+471737.9has a magnetic ?eld strength of 8MG and an inclination of 90?,while the best ?t model for SDSS J125250.03?020608.1has a magnetic ?eld strength of 3MG and an inclina-tion of 90?.H βappears to be distorted in both systems,indicating a potential broadening of a few MG ?eld,how-ever H γand H δwould show more splitting than H βbut both appear to be relatively sharp in comparison.H βmay be a?ected by TiO features from the M dwarf and there does appear to be a minor glitch in the blue por-tion of the spectrum,indication di?culty with SDSS ?ux calibration.

5.DISCUSSION

Of the 1253potential close binary systems in the DR5catalog,there were 168systems that we could not mea-sure with our program.These include the :+dM systems and binaries with non-DA WDs.We were not able to unambiguously determine if the :+dM systems have a

6Silvestri et al.

magnetic or a non–magnetic WD as the blue component is barely visible in most of the:+dM SDSS spectra.Un-til we can identify the companion,we can not make any statement about magnetism in these objects.The:+dM cases where a blue component is seen in the spectrum which must be a WD,but too faint even to classify the type may include(a)cases where the WD is simply very cool,but also(b)magnetic WDs of suitably warmer ef-fective temperature but with smaller radii.These need to be reobserved in the blue with a spectrograph and tele-scope of large aperture.We made no attempt to measure the DB WDs because we lack viable magnetic DB WD models;however,all of the DB spectra matched well to non–magnetic DB WD models,so we believe it is un-likely that any of the WDs in these pairs are magnetic. We could not measure the pairs with DC WDs because there are no features with which we can detect a magnetic ?eld and therefore cannot rule out magnetism without employing polarimetry or other methods of identifying a magnetic?eld in these objects.

Of the remaining binary systems,we?nd only two that may contain WDs with weak magnetic?elds.Our automatic detection methods are sensitive to magnetic ?elds between3MG≤B WD≤30MG;?eld strengths larger than this are easily identi?ed by visual inspec-tion.Therefore,there is a signi?cant shortage of close binary systems that could be the progenitors of the large Intermediate–Polar and Polar CV populations.

As mentioned in§1,Schmidt et al.(2005b)discuss six newly identi?ed low accretion rate magnetic binary sys-tems as being the probable progenitors to magnetic CVs. The magnetic?eld strengths of the WDs in these sys-tems are fairly high,with most around60MG.These objects are clearly pre-Polars and provide an obvious link between post–common envelope,detached binaries and Polars.The existence of these objects,however only adds to the mystery.If observations of these objects are possi-ble then why have no detached binary systems with large magnetic?eld WDs been detected?

Perhaps selection e?ects are to blame.Schmidt et al. (2005b)discuss the various selection e?ects associated with targeting these pre–Polars with the SDSS.As is the case with the majority of the close binary systems, the pre–Polars were targeted by the SDSS QSO target-ing pipeline(Richards et al.2002)which accounts for the narrow range of magnetic?eld strengths found in these objects.In the case of signi?cantly lower or higher mag-netic?eld strengths,the pre–Polars resemble an ordinary WD+M dwarf binary in color–color space and are re-jected by the QSO targeting algorithm.It is possible that this selection e?ect accounts for the lack of close binary magnetic systems targeted by the SDSS as well.Arguing against this explanation is the large number of detached close binary systems in our sample,and the fact that the pre–Polars were observed by the SDSS.It is quite sur-prising that a detached system with a WD magnetic?eld in the range required to detect these pre–Polars has not been observed,if such objects exist.

Another selection e?ect discussed by Liebert et al. (2005)argues that magnetic WDs,on average,are more massive than non–magnetic WDs;this implies smaller WD radii and therefore less luminous WDs.Faint,mas-sive WDs in competition with the?ux from an M star companion might go undetected in an optical survey because they are hidden by the more luminous,non–degenerate companion.This would imply an unusually small mass ratio(q=M2/M1)for the initial binary if the progenitor of the magnetic white dwarf were mas-sive(3-8M⊙).Thus,the magnetics may usually have been paired with an A-G star.However,the vast major-ity of polars and intermediate polars with strongly mag-netic primaries have M dwarf companions.Perhaps they were whittled down from more massive stars by mass transfer.The LARPS are selected for spectroscopy be-cause of their peculiar colors,which arise because of the isolated cyclotron harmonics.As Schmidt et al.(2005b, 2007)point out,the WDs in LARPS are generally rather faint(cool)and,in one case,undetected.So the large mass/small radius selection e?ect would also apply to the pre–Polars which have been observed by SDSS.

6.CONCLUSIONS

We present a new sample of close binary systems through the Data Release Five of the SDSS.This cat-alog includes more than1200WD+M dwarf binary systems and represents the largest catalog of its kind to date.

We have?t magnetic DA WD models(see Schmidt et al.2003,and references therein)to the1100 DA WD+M dwarf close binaries in the DR5sample. Only two have been found to potentially harbor a mag-netic DA WD of low(B WD<10MG)magnetic?eld strength.Neither of these potential magnetic WDs are convincing cases,though follow–up spectroscopy to im-prove the S/N or polarimetry on these objects should be performed to completely rule out the presence of a magnetic?eld.

The remaining~100close binaries comprised of M dwarfs with excess blue?ux(:+dM)and binaries with non–DA WDs require other means of detecting mag-netic?elds.Methods that are sensitive to magnetic ?elds weaker than3MG should also be employed on this sample to detect possible Intermediate–Polar progenitors that may have escaped detection with our methods. Even if future spectroscopic or polarimetric observa-tions reveal the two DA WD candidates to be magnetic, their?eld strengths will likely prove to be quite low.A sample of two,detached,low magnetic?eld WD binaries is not representative of the majority of known magnetic WDs in CVs nor would it comprise an adequate progen-itor population for the newly discovered magnetic pre–Polars described in Schmidt et al.(2005b).The question of where the progenitors to magnetic CVs are remains unanswered by the current spectroscopically identi?ed close binary population.

This work was supported by NSF Grant AST02–05875 (NMS,SLH),a University of Washington undergraduate research grant(MPL),NSF grant AST03–06080(GDS), and NSF grant AST03–07321(JL).

Funding for the SDSS and SDSS–II has been pro-vided by the Alfred P.Sloan Foundation,the Partic-ipating Institutions,the National Science Foundation, the U.S.Department of Energy,the National Aeronau-tics and Space Administration,the Japanese Monbuka-gakusho,the Max Planck Society,and the Higher Educa-tion Funding Council for England.The SDSS Web Site is https://www.360docs.net/doc/2410155615.html,/.

Magnetic WDs in CV Progenitors7 The SDSS is managed by the Astrophysical Research

Consortium for the Participating Institutions.The Par-

ticipating Institutions are the American Museum of Nat-

ural History,Astrophysical Institute Potsdam,Univer-

sity of Basel,University of Cambridge,Case Western

Reserve University,University of Chicago,Drexel Uni-

versity,Fermilab,the Institute for Advanced Study,the

Japan Participation Group,Johns Hopkins University,

the Joint Institute for Nuclear Astrophysics,the Kavli

Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology,the

Korean Scientist Group,the Chinese Academy of Sci-

ences(LAMOST),Los Alamos National Laboratory,the

Max–Planck–Institute for Astronomy(MPIA),the Max–

Planck–Institute for Astrophysics(MPA),New Mexico

State University,Ohio State University,University of

Pittsburgh,University of Portsmouth,Princeton Uni-

versity,the United States Naval Observatory,and the

University of Washington.

8Silvestri et al.

REFERENCES

Abazajian,K.,et al.2003,AJ,126,2081

—.2004,AJ,128,502

—.2005,AJ,129,1755

Adelman-McCarthy,J.K.,et al.2006,ApJS,162,38

—.2007,ApJS,submitted

(Burleigh),M.R.,et al.2006,MNRAS, accepted,[astro-ph/0609366],accepted,[astro

de Kool,M.,&Ritter,H.1993,A&A,267,397

Debes,J.H.,L′o pez-Morales,M.,Bonanos,A.Z.,&Weinberger, A.J.2006,ApJ,647,L147

Eisenstein, D.,et al.2006,AJ,accepted[astro-ph/0606700], accepted[astro

Farihi,J.,Becklin,E.E.,&Zuckerman,B.2005a,ApJS,161,394 Farihi,J.,Zuckerman,B.,&Becklin,E.E.2005b,Astronomische Nachrichten,326,964

Fukugita,M.,Ichikawa,T.,Gunn,J.E.,Doi,M.,Shimasaku,K., &Schneider,D.P.1996,AJ,111,1748

Giclas,H.L.,Burnham,R.,&Thomas,N.G.1971,Lowell proper motion survey Northern Hemisphere.The G numbered stars. 8991stars fainter than magnitude8with motions≥0′′.26/year (Flagsta?,Arizona:Lowell Observatory,1971)

Giclas,H.L.,Burnham,Jr.,R.,&Thomas,N.G.1978,Lowell Observatory Bulletin,8,89

Gunn,J.E.,et al.1998,AJ,116,3040

—.2006,AJ,131,2332

Hawley,S.L.,et al.2002,AJ,123,3409

Hogg,D.W.,Finkbeiner,D.P.,Schlegel,D.J.,&Gunn,J.E. 2001,AJ,122,2129

Holberg,J. B.,&Magargal,K.2005,in ASP Conf.Ser.334: 14th European Workshop on White Dwarfs,ed.D.Koester& S.Moehler,419–+

Holberg,J.B.,Oswalt,T.D.,&Sion,E.M.2002,ApJ,571,512 Ivezi′c,ˇZ.,et al.2004,Astronomische Nachrichten,325,583 Kawka,A.,Vennes,S.,Schmidt,G.D.,Wickramasinghe,D.T.,& Koch,R.2007,ApJ,654,499

Kemic,S.B.1974a,ApJ,193,213

—.1974b,ApJ,193,213

Kleinman,S.J.,et al.2004,ApJ,607,426

Koen,C.,&Maxted,P.F.L.2006,MNRAS,371,1675 Langer,N.,Deutschmann,A.,Wellstein,S.,&H¨o?ich,P.2000, A&A,362,1046

Lemagie,M.P.,Silvestri,N.M.,Hawley,S.L.,Schmidt,G.D., Liebert,J.,&Wolfe,M.A.2004,in Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society,1515Liebert,J.,Bergeron,P.,&Holberg,J.B.2003,AJ,125,348 Liebert,J.et al.2005,AJ,129,2376

Liebert,J.,et al.1988,PASP,100,1302

Livio,M.1996,in ASP Conf.Ser.90:The Origins,Evolution,and Destinies of Binary Stars in Clusters,https://www.360docs.net/doc/2410155615.html,one&J.-C. Mermilliod,291

Luyten,W.J.1968,Univ.Minnesota,Minneapolis,$fasc.1-57,$ 1963-81,1963,13,1(1968),13,1

—.1972,Proper Motion Survey with the48-inch Telescope, Univ.Minnesota,29,1(1972),29,1

Luyten,W.J.,Anderson,J.H.,&University Of Minnesota.Observatory.1964,Publications of the Astronomical Observatory University of Minnesota

Pier,J.R.,Munn,J.A.,Hindsley,R.B.,Hennessy,G.S.,Kent, S.M.,Lupton,R.H.,&Ivezi′c,ˇZ.2003,AJ,125,1559 Politano,M.,&Weiler,K.P.2006,ApJ,641,L137

Pourbaix,D.,et al.2005,A&A,444,643

Raymond,S.N.,et al.2003,AJ,125,2621

Richards,G.T.,et al.2002,AJ,123,2945

Schmidt,G.D.,Szkody,P.,Henden,A.,Anderson,S.F.,Lamb, D.Q.,Margon,B.,&Schneider,D.P.2007,ApJ,654,521 Schmidt,G. D.,Szkody,P.,Silvestri,N.M.,Cushing,M. C., Liebert,J.,&Smith,P.S.2005a,ApJ,630,L173

Schmidt,G.D.,et al.2003,ApJ,595,1101

—.2005b,ApJ,630,1037

Schuh,S.,&Nagel,T.2006,in ASP Conf.Ser.,The15th European Workshop on White Dwarfs,ed.R.Napiwotzki&M.Burleigh, accepted[astro–ph/0610324]

Silvestri,N.M.,Hawley,S.L.,&Oswalt,T.D.2005,AJ,129,2428 Silvestri,N.M.,et al.2006,AJ,131,1674

Smith,J.A.1997,Ph.D.Thesis,Florida Institute of Technology Smith,J.A.,et al.2002,AJ,123,2121

Smolˇc i′c,V.,et al.2004,ApJ,615,L141

Stoughton,C.,et al.2002,AJ,123,485

Tucker,D.L.,et al.2006,Astronomische Nachrichten,327,821 van den Besselaar,E.J.M.,Roelofs,G.H.A.,Nelemans,G.A., Augusteijn,T.,&Groot,P.J.2005,A&A,434,L13 Vanlandingham,K.M.,et al.2005,AJ,130,734 Wickramasinghe,D.T.,&Ferrario,L.2000,PASP,112,873 York,D.G.,et al.2000,AJ,120,1579

Magnetic WDs in CV Progenitors

9

TABLE 1

The SDSS–I DR5Catalog of Close Binary Systems.

Identi?er Plate FiberID MJD Sp1+Sp2a

R.A.b Decl.u psf σu A u g psf σg A g r psf σr A r (SDSS J)(deg)(deg)(1)(2)(3)(4)(5)(6)(7)(8)(9)(10)(11)(12)(13)(14)

(15)(16)001029.87+003126.2038854551793DZ:+dM 2.6244800.5239621.930.190.1420.850.040.1019.980.030.08001726.63?002451.2068715352518DA+dMe 4.36099?00.4142219.680.040.1419.290.030.1019.030.020.07001733.59+004030.4038961451795DA+dM 4.3899600.6751122.100.400.1320.790.140.1019.590.030.07001749.24?000955.3038911251795DA+dMe 4.45519?00.1653916.570.020.1316.870.020.1017.030.010.07002620.41+144409.5

0753

079

52233

DA+dMe

6.58505

14.73597

17.57

0.01

0.27

17.35

0.01

0.20

17.34

0.02

0.15

Note .—Table 1is published in its entirety in the electronic edition of the AJ.A portion is shown here for guidance regarding its form and content.ugriz photometry has not been cor

a Sp1:Spectral type of the WD,Sp2:Spectral type of the low–mass dwarf (see Silvestri et al.2006,for details on Sp determination);e:emission detected visually.

b R.A.and Decl.ar

(2003,2004,2005);DR[4,5]:Adelman-McCarthy et al.(2006,2007);R03:published in Raymond et al.(2003);K04:published in Kleinman et al.(2004);B05:published in van den Besse Silvestri et al.(2006);E06:published in Eisenstein et al.(2006);P05:published in Pourbaix et al.(2005);KM:published in Koen &Maxted (2006);SN:published in Schuh &Nagel (2006)

white dwarf.

10Silvestri et al.

TABLE2

Two Potential Magnetic White Dwarf Binary Systems.

Identi?er Plate Fiber MJD R.A.Decl.B i Sp1+Sp2u g r i z Release SDSS J(deg)(deg)(MG)(deg)

(1)(2)(3)(4)(5)(6)(7)(8)(9)(10)(11)(12)(13)(14)(15) 082828.18+471737.9054933851981127.11742+47.29387890DA+dM20.4120.3520.3319.5819.02DR1 125250.03?020608.1033834351694193.20846?02.10227390DA+dM19.2519.1218.8918.3117.82DR1

对翻译中异化法与归化法的正确认识

对翻译中异化法与归化法的正确认识 班级:外语学院、075班 学号:074050143 姓名:张学美 摘要:运用异化与归化翻译方法,不仅是为了让读者了解作品的内容,也能让读者通过阅读译作,了解另一种全新的文化,因为进行文化交流才是翻译的根本任务。从文化的角度考虑,采用异化法与归化法,不仅能使译文更加完美,更能使不懂外语的人们通过阅读译文,了解另一种文化,促进各民族人们之间的交流与理解。翻译不仅是语言符号的转换,更是跨文化的交流。有时,从语言的角度所作出的译文可能远不及从文化的角度所作出的译文完美。本文从翻译策略的角度,分别从不同时期来说明人们对异化法与归化法的认识和运用。 关键词:文学翻译;翻译策略;异化;归化;辩证统一 一直以来,无论是在我国还是在西方,直译(literal translation)与意译(liberal translation)是两种在实践中运用最多,也是被讨论研究最多的方法。1995年,美籍意大利学者劳伦斯-韦努蒂(Lawrence Venuti)提出了归化(domestication)与异化(foreignization)之说,将有关直译与意译的争辩转向了对于归化与异化的思考。归化与异化之争是直译与意译之争的延伸,是两对不能等同的概念。直译和意译主要集中于语言层面,而异化和归化则突破语言的范畴,将视野扩展到语言、文化、思维、美学等更多更广阔的领域。 一、归化翻译法 Lawrwnce Venuti对归化的定义是,遵守译入语语言文化和当前的主流价值观,对原文采用保守的同化手段,使其迎合本土的典律,出版潮流和政治潮流。采用归化方法就是尽可能不去打扰读者,而让作者向读者靠拢(the translator leaves the reader in peace, as much as possible, and moves the author towards him)。归化翻译法的目的在于向读者传递原作的基本精神和语义内容,不在于语言形式或个别细节的一一再现。它的优点在于其流利通顺的语言易为读者所接受,译文不会对读者造成理解上的障碍,其缺点则是译作往往仅停留在内容、情节或主要精神意旨方面,而无法进入沉淀在语言内核的文化本质深处。 有时归化翻译法的采用也是出于一种不得已,翻译活动不是在真空中进行的,它受源语文化和译语文化两种不同文化语境的制约,还要考虑到两种文化之间的

翻译中的归化与异化

“异化”与“归化”之间的关系并评述 1、什么是归化与异化 归化”与“异化”是翻译中常面临的两种选择。钱锺书相应地称这两种情形叫“汉化”与“欧化”。A.归化 所谓“归化”(domestication 或target-language-orientedness),是指在翻译过程中尽可能用本民族的方式去表现外来的作品;归化翻译法旨在尽量减少译文中的异国情调,为目的语读者提供一种自然流畅的译文。Venuti 认为,归化法源于这一著名翻译论说,“尽量不干扰读者,请作者向读者靠近” 归化翻译法通常包含以下几个步骤:(1)谨慎地选择适合于归化翻译的文本;(2)有意识地采取一种自然流畅的目的语文体;(3)把译文调整成目的语篇体裁;(4)插入解释性资料;(5)删去原文中的实观材料;(6)调协译文和原文中的观念与特征。 B.“异化”(foreignization或source-language-orientedness)则相反,认为既然是翻译,就得译出外国的味儿。异化是根据既定的语法规则按字面意思将和源语文化紧密相连的短语或句子译成目标语。例如,将“九牛二虎之力”译为“the strength of nine bulls and two tigers”。异化能够很好地保留和传递原文的文化内涵,使译文具有异国情调,有利于各国文化的交流。但对于不熟悉源语及其文化的读者来说,存在一定的理解困难。随着各国文化交流愈来愈紧密,原先对于目标语读者很陌生的词句也会变得越来越普遍,即异化的程度会逐步降低。 Rome was not built in a day. 归化:冰冻三尺,非一日之寒. 异化:罗马不是一天建成的. 冰冻三尺,非一日之寒 异化:Rome was not built in a day. 归化:the thick ice is not formed in a day. 2、归化异化与直译意译 归化和异化,一个要求“接近读者”,一个要求“接近作者”,具有较强的界定性;相比之下,直译和意译则比较偏重“形式”上的自由与不自由。有的文中把归化等同于意译,异化等同于直译,这样做其实不够科学。归化和异化其实是在忠实地传达原作“说了什么”的基础之上,对是否尽可能展示原作是“怎么说”,是否最大限度地再现原作在语言文化上的特有风味上采取的不同态度。两对术语相比,归化和异化更多地是有关文化的问题,即是否要保持原作洋味的问题。 3、不同层面上的归化与异化 1、句式 翻译中“归化”表现在把原文的句式(syntactical structure)按照中文的习惯句式译出。

翻译的归化与异化

万方数据

万方数据

万方数据

万方数据

翻译的归化与异化 作者:熊启煦 作者单位:西南民族大学,四川,成都,610041 刊名: 西南民族大学学报(人文社科版) 英文刊名:JOURNAL OF SOUTHWEST UNIVERSITY FOR NATIONALITIES(HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCE) 年,卷(期):2005,26(8) 被引用次数:14次 参考文献(3条) 1.鲁迅且介亭杂文二集·题未定草 2.刘英凯归化--翻译的歧路 3.钱钟书林纾的翻译 引证文献(15条) 1.郭锋一小议英语翻译当中的信达雅[期刊论文]-青春岁月 2011(4) 2.许丽红论汉英语言中的文化差异与翻译策略[期刊论文]-考试周刊 2010(7) 3.王笑东浅谈汉英语言中的差异与翻译方法[期刊论文]-中国校外教育(理论) 2010(6) 4.王宁中西语言中的文化差异与翻译[期刊论文]-中国科技纵横 2010(12) 5.鲍勤.陈利平英语隐喻类型及翻译策略[期刊论文]-云南农业大学学报(社会科学版) 2010(2) 6.罗琴.宋海林浅谈汉英语言中的文化差异及翻译策略[期刊论文]-内江师范学院学报 2010(z2) 7.白蓝跨文化视野下文学作品的英译策略[期刊论文]-湖南社会科学 2009(5) 8.王梦颖探析汉英语言中的文化差异与翻译策略[期刊论文]-中国校外教育(理论) 2009(8) 9.常晖英汉成语跨文化翻译策略[期刊论文]-河北理工大学学报(社会科学版) 2009(1) 10.常晖对翻译文化建构的几点思考[期刊论文]-牡丹江师范学院学报(哲学社会科学版) 2009(4) 11.常晖认知——功能视角下隐喻的汉译策略[期刊论文]-外语与外语教学 2008(11) 12.赵勇刚汉英语言中的文化差异与翻译策略[期刊论文]-时代文学 2008(6) 13.常晖.胡渝镛从文化角度看文学作品的翻译[期刊论文]-重庆工学院学报(社会科学版) 2008(7) 14.曾凤英从文化认知的视角谈英语隐喻的翻译[期刊论文]-各界 2007(6) 15.罗琴.宋海林浅谈汉英语言中的文化差异及翻译策略[期刊论文]-内江师范学院学报 2010(z2) 本文链接:https://www.360docs.net/doc/2410155615.html,/Periodical_xnmzxyxb-zxshkxb200508090.aspx

归化与异化翻译实例

翻译作业10 Nov 15 一、请按归化法(Domestication)翻译下列习语。 Kill two birds with one stone a wolf in sheep’s clothing strike while the iron is hot. go through fire and water add fuel to the flames / pour oil on the flames spring up like mushrooms every dog has his day keep one’s head above water live a dog’s life as poor as a church mouse a lucky dog an ass in a lion’s skin a wolf in sheep’s clothing Love me, love my dog. a lion in the way lick one’s boots as timid as a hare at a stone’s throw as stupid as a goose wet like a drown rat as dumb as an oyster lead a dog’s life talk horse One boy is a boy, two boys half a boy, and three boys nobody. Man proposes, God disposes. Cry up wine and sell vinegar (cry up, to praise; extol: to cry up one's profession) Once bitten, twice shy. An hour in the morning is worth two in the evening. New booms sweep clean. take French leave seek a hare in a hen’s nest have an old head on young shoulder Justice has long arms You can’t teach an old dog Rome was not built in a day. He that lives with cripples learns to limp. Everybody’s business is nobody’s business. The more you get, the more you want. 二、请按异化法(foreignization)翻译下列习语。 Kill two birds with one stone a wolf in sheep’s clothing

清华大学《控制工程基础》课件-4

则系统闭环传递函数为 假设得到的闭环传递函数三阶特征多项式可分解为 令对应项系数相等,有 二、高阶系统累试法 对于固有传递函数是高于二阶的高阶系统,PID校正不可能作到全部闭环极点的任意配置。但可以控制部分极点,以达到系统预期的性能指标。 根据相位裕量的定义,有 则有 则 由式可独立地解出比例增益,而后一式包含两个未知参数和,不是唯一解。通常由稳态误差要求,通过开环放大倍数,先确定积分增益,然后计算出微分增益。同时通过数字仿真,反复试探,最后确定、和三个参数。 设单位反馈的受控对象的传递函数为 试设计PID控制器,实现系统剪切频率 ,相角裕量。 解: 由式,得 由式,得 输入引起的系统误差象函数表达式为

令单位加速度输入的稳态误差,利用上式,可得 试探法 采用试探法,首先仅选择比例校正,使系统闭环后满足稳定性指标。然后,在此基础上根据稳态误差要求加入适当参数的积分校正。积分校正的加入往往使系统稳定裕量和快速性下降,此时再加入适当参数的微分校正,保证系统的稳定性和快速性。以上过程通常需要循环试探几次,方能使系统闭环后达到理想的性能指标。 齐格勒-尼柯尔斯法 (Ziegler and Nichols ) 对于受控对象比较复杂、数学模型难以建立的情况,在系统的设计和调试过程中,可以考虑借助实验方法,采用齐格勒-尼柯尔斯法对PID调节器进行设计。用该方法系统实现所谓“四分之一衰减”响应(”quarter-decay”),即设计的调节器使系统闭环阶跃响应相临后一个周期的超调衰减为前一个周期的25%左右。 当开环受控对象阶跃响应没有超调,其响应曲线有如下图的S形状时,采用齐格勒-尼柯尔斯第一法设定PID参数。对单位阶跃响应曲线上斜率最大的拐点作切线,得参数L 和T,则齐格勒-尼柯尔斯法参数设定如下: (a) 比例控制器: (b) 比例-积分控制器: , (c) 比例-积分-微分控制器: , 对于低增益时稳定而高增益时不稳定会产生振荡发散的系统,采用齐格勒-尼柯尔斯第二法(即连续振荡法)设定参数。开始只加比例校正,系统先以低增益值工作,然后慢慢增加增益,直到闭环系统输出等幅度振荡为止。这表明受控对象加该增益的比例控制已达稳定性极限,为临界稳定状态,此时测量并记录振荡周期Tu和比例增益值Ku。然后,齐格勒-尼柯尔斯法做参数设定如下: (a) 比例控制器:

翻译术语归化和异化

归化和异化这对翻译术语是由美国著名翻译理论学家劳伦斯韦努蒂(Lawrence Venuti)于1995年在《译者的隐身》中提出来的。 归化:是要把源语本土化,以目标语或译文读者为归宿,采取目标语读者所习惯的表达方式来传达原文的内容。归化翻译要求译者向目的语的读者靠拢,译者必须像本国作者那样说话,原作者要想和读者直接对话,译作必须变成地道的本国语言。归化翻译有助于读者更好地理解译文,增强译文的可读性和欣赏性。 异化:是“译者尽可能不去打扰作者,让读者向作者靠拢”。在翻译上就是迁就外来文化的语言特点,吸纳外语表达方式,要求译者向作者靠拢,采取相应于作者所使用的源语表达方式,来传达原文的内容,即以目的语文化为归宿。使用异化策略的目的在于考虑民族文化的差异性、保存和反映异域民族特征和语言风格特色,为译文读者保留异国情调。 作为两种翻译策略,归化和异化是对立统一,相辅相成的,绝对的归化和绝对的异化都是不存在的。在广告翻译实践中译者应根据具体的广告语言特点、广告的目的、源语和目的语语言特点、民族文化等恰当运用两种策略,已达到具体的、动态的统一。 归化、异化、意译、直译 从历史上看,异化和归化可以视为直译和意译的概念延伸,但又不完全等同于直译和意译。直译和意译所关注的核心问题是如何在语言层面处理形式和意义,而异化和归化则突破了语言因素的局限,将视野扩展到语言、文化和美学等因素。按韦努蒂(Venuti)的说法,归化法是“把原作者带入译入语文化”,而异化法则是“接受外语文本的语言及文化差异,把读者带入外国情景”。(Venuti,1995:20)由此可见,直译和意译主要是局限于语言层面的价值取向,异化和归化则是立足于文化大语境下的价值取向,两者之间的差异是显而易见的,不能混为一谈。 归化和异化并用互补、辩证统一 有些学者认为归化和异化,无论采取哪一种都必须坚持到底,不能将二者混淆使用。然而我们在实际的翻译中,是无法做到这么纯粹的。翻译要求我们忠实地再现原文作者的思想和风格,而这些都是带有浓厚的异国情调的,因此采用异化法是必然;同时译文又要考虑到读者的理解及原文的流畅,因此采用归化法也是必然。选取一个策略而完全排除另一种策略的做法是不可取的,也是不现实的。它们各有优势,也各有缺陷,因此顾此失彼不能达到最终翻译的目的。 我们在翻译中,始终面临着异化与归化的选择,通过选择使译文在接近读者和接近作者之间找一个“融会点”。这个“融会点”不是一成不变的“居中点”,它有时距离作者近些,有时距离读者近些,但无论接近哪

翻译中的归化与异化

姓名:徐中钧上课时间:T2 成绩: 翻译中的归化与异化 归化与异化策略是我们在翻译中所采取的两种取向。归化是指遵从译出语文化的翻译策略取向,其目的是使译文的内容和形式在读者对现实了解的知识范围之内,有助于读者更好地理解译文,增强译文的可读性。异化是指遵从译入语文化的翻译策略取向,其目的是使译文保存和反映原文的文化背景、语言传统,使读者能更好地了解该民族语言和文化的特点。直译和意译主要是针对的是形式问题,而归化和异化主要针对意义和形式得失旋涡中的文化身份、文学性乃至话语权利的得失问题,二者不能混为一谈。 在全球经济一体化趋势日益明显的今天,人们足不出门就能与世界其他民族的人进行交流。无论是国家领导人会晤、国际经济会议,还是个人聚会、一对一谈话,处于不同文化的两个民族都免不了要进行交流。如果交流的时候不遵从对方的文化背景,会产生不必要的误会,造成不必要的麻烦。在2005年1月20 日华盛顿的就职典礼游行活动中,布什及其家人做了一个同时伸出食指和小指的手势。在挪威,这个手势常常为死亡金属乐队和乐迷使用,意味着向恶魔行礼。在电视转播上看到了这一画面的挪威人不禁目瞪口呆,这就是文化带来的差异。人们日常生活中的习语、修辞的由于文化差异带来的差别更是比比皆是,如以前的“白象”电池的翻译,所以文化传播具有十分重要的意义。由此可见,借助翻译来传播文化对民族间文化的交流是很有必要的。 一般来说,采取归化策略使文章变得简单易懂,异化使文章变得烦琐难懂。归化虽然丢掉了很多原文的文化,但使读者读起来更流畅,有利于文化传播的广度。采取异化策略虽然保存了更多的异族文化,能传播更多的异族文化,有利于文化传播的深度,但其可读性大大降低。归化和异化都有助于文化的传播,翻译时应注意合理地应用归化与异化的手段。对于主要是表意的译文,应更多地使用归化手段,反之则更多地使用异化手段。 要使翻译中文化传播的效果达到最好,译者应该考虑主要读者的具体情况、翻译的目的、译入文的内容形式等具体情况而动态地采取归化与异化的手段。 文章字符数:920 参考文献: 论异化与归化的动态统一作者:张沉香(即讲义) 跨文化视野中的异化/归化翻译作者:罗选民https://www.360docs.net/doc/2410155615.html,/llsj/s26.htm

翻译的归化与异化

【摘要】《法国中尉的女人》自1969年面世以来,凭借着高度的艺术价值,吸引了国内外学者的眼球。在中国市场上也流传着此书的多个译本,本文就旨在透过《法国中尉的女人》中的两处题词的译作分析在具体翻译文本中如何对待归化与异化的问题。 【关键词】《法国中尉的女人》;题词;归化;异化 一、归化与异化 在翻译领域最早提出归化与异化两个词的学者是美国翻译学者韦努蒂。归化一词在《翻译研究词典》中的定义为:归化指译者采用透明、流畅的风格以尽可能减弱译语读者对外语语篇的生疏感的翻译策略。异化一词的定义为:指刻意打破目的语的行文规范而保留原文的某些异域特色的翻译策略。韦努蒂主张在翻译的过程中更多的使用异化,倡导看起来不通顺的译文,注重突出原文的异域风格、语言特色与文化背景。 二、如何看待归化与异化 鲁迅说对于归化与异化,我们不能绝对的宣称哪种是绝对的好的,另一种是绝对的不好的。翻译的过程中归化与异化是相辅相成互相补充的,具体使用哪种方法不仅需要依据翻译目的以及译文的读者群来判断。这也正是本文对待归化异化的一个态度。下面就通过分析刘蔺译本与陈译本在处理《法国中尉的女人》第五章的引言丁尼生《悼念集》时的例子来具体分析这一点。对于原文 at first as death, love had not been, or in his coarsest satyr-shape had bruised the herb and crush’d the grape, 刘蔺译本将此处翻译为 啊,天哪,提这样的问题 又有保益?如果死亡 首先意味着生命了结, 那爱情,如果不是 在涓涓细流中戛然中止, 就是一种平庸的友情, 或是最粗野的色迷 在树林中肆意饕餮, 全不顾折断茎叶, 揉碎葡萄―― 而此时陈译本却将此诗译作 哦,我啊,提出一个无益的问题 又有何用?如果人们认为死亡 就是生命的终结,那么,爱却不是这样, 否则,爱只是在短暂的空闲时 那懒散而没激情的友谊, 或者披着他萨梯粗犷的外套 已踩伤了芳草,并摧残了葡萄, 在树林里悠闲自在,开怀喝吃。 两篇译作各有千秋,从这首诗整体着眼刘蔺译本更趋向于归化手法,陈译本更倾向于异化处理。刘蔺译本将satyr一词译色迷采用了归化的技巧,而陈译本却将satyr一词译为萨梯,采用了异化的手法。satyr原指人羊合体的丛林之神,其实刘蔺译本与陈译本在处理satyr 时采用不同的方法就是因为翻译目的及读者文化群不同引起的。1986年出的刘蔺译本出版时,

《交通规划》课程教学大纲

《交通规划》课程教学大纲 课程编号:E13D3330 课程中文名称:交通规划 课程英文名称:Transportation Planning 开课学期:秋季 学分/学时:2学分/32学时 先修课程:管理运筹学,概率与数理统计,交通工程学 建议后续课程:城市规划,交通管理与控制 适用专业/开课对象:交通运输类专业/3年级本科生 团队负责人:唐铁桥责任教授:执笔人:唐铁桥核准院长: 一、课程的性质、目的和任务 本课程授课对象为交通工程专业本科生,是该专业学生的必修专业课。通过本课程的学习,应该掌握交通规划的基础知识、常用方法与模型。课程具体内容包括:交通规划问题分析的一般方法,建模理论,交通规划过程与发展历史,交通调查、出行产生、分布、方式划分与交通分配的理论与技术实践,交通网络平衡与网络设计理论等,从而在交通规划与政策方面掌握宽广的知识和实际的操作技能。 本课程是一间理论和实践意义均很强的课程,课堂讲授要尽量做到理论联系实际,模型及其求解尽量结合实例,深入浅出,使学生掌握将交通规划模型应用于实际的基本方法。此外,考虑到西方在该领域内的研究水平,讲授时要多参考国外相关研究成果,多介绍专业术语的英文表达方法以及相关外文刊物。课程主要培养学生交通规划的基本知识、能力和技能。 二、课程内容、基本要求及学时分配 各章内容、要点、学时分配。适当详细,每章有一段描述。 第一章绪论(2学时) 1. 交通规划的基本概念、分类、内容、过程、发展历史、及研究展望。 2. 交通规划的基本概念、重要性、内容、过程、发展历史以及交通规划中存在的问题等。

第二章交通调查与数据分析(4学时) 1. 交通调查的概要、目的、作用和内容等;流量、密度和速度调查;交通延误和OD调查;交通调查抽样;交通调查新技术。 2. 交通中的基本概念,交通流量、速度和密度的调查方法,调查问卷设计与实施,调查抽样,调查结果的统计处理等。 第三章交通需求预测(4学时) 1. 交通发生与吸引的概念;出行率调查;发生与吸引交通量的预测;生成交通量预测、发生与吸引交通量预测。 2. 掌握交通分布的概念;分布交通量预测;分布交通量的概念,增长系数法及其算法。 3. 交通方式划分的概念;交通方式划分过程;交通方式划分模型。 第四章道路交通网络分析(4学时) 1. 交通网络计算机表示方法、邻接矩阵等 2. 交通阻抗函数、交叉口延误等。 第五章城市综合交通规划(2学时) 1. 综合交通规划的任务、内容;城市发展战略规划的基本内容和步骤 2. 城市中长期交通体系规划的内容、目标以及城市近期治理规划的目标与内容 第六章城市道路网规划(2学时) 城市路网、交叉口、横断面规划及评价方法。 第七章城市公共交通规划(2学时) 城市公共交通规划目标任务、规划方法、原则及技术指标。 第八章停车设施规划(2学时) 停车差设施规划目标、流程、方法和原则。 第九章城市交通管理规划(2学时) 城市交通管理规划目标、管理模式和管理策略。 第十章公路网规划(2学时) 公路网交通调查与需求预测、方案设计与优化。 第十一章交通规划的综合评价方法(2学时) 1. 交通综合评价的地位、作用及评价流程和指标。 2. 几种常见的评价方法。 第十二章案例教学(2学时)

中国旅游文本汉英翻译的归化和异化演示教学

中国旅游文本汉英翻译的归化和异化

中国旅游文本汉英翻译的归化和异化 内容摘要:自改革开放政策执行以来,我国旅游业一直呈现迅速繁荣发展趋势,旅游业在我国国民经济发展中扮演着十分重要的角色。与此同时,旅游类翻译已经被视为一条将我国旅游业引往国际市场的必经之路。为了能够让国外游客更清楚地了解中国的旅游胜地,我们应该对旅游翻译加以重视。尽管国内的旅游资料翻译如同雨后春笋般涌现,但在旅游翻译中仍存在许多问题,尤其是翻译策略的选择问题。归化与异化作为处理语言形式和文化因素的两种不同的翻译策略,无疑对旅游翻译的发展做出了巨大贡献。本文将重点讨论在汉英旅游翻译中,译者该如何正确的处理归化和异化问题,实现归化和异化的有机结合,从而达到理想的翻译水平。从归化与异化的定义、关系、以及归化和异化在旅游翻译中的应用与意义进行论述。 关键词:旅游文本归化翻译异化翻译 关于翻译中归化和异化的定义,国内外的专家学者已经做了很多的描述。为了使得本文读者更好地了解什么是翻译中的归化和异化,作者将介绍这两种翻译方法的关键不同,包括两者的定义以及两者之间的关系。

从他们的定义,很容易找到归化和异化之间的差异。通过对比,这两种策略有各自的目的、优点和语言样式。归化是指翻译策略中,应使作为外国文字的目标语读者尽可能多的感“流畅的风格,最大限度地淡化对原文的陌生感的翻译策略”(Shuttleworth & Cowie,1997:59)。换句话说,归化翻译的核心思想是译者需要更接近读者。归化的目的在于向读者传递最基本精神和内容含义。这种翻译策略明显的优势就是读者可以很容易地接受它流畅的语言风格。例如,济公是个中国神话中的传奇人物。不过,外国人可能没有在这种明确的翻译方式下获得信息。因此,适合的翻译方法是找出西方国家中类似济公这样的人物。因此最终的翻译为:济公是一个中国神话中的传奇人物(类似于西方文化中的罗宾汉)。这样的翻译更容易被目的语读者所接受。“异化是指在在翻译策略中,使译文打破目地语的约束,迁就外来文化的语言特点以及文化差异。”(Venuti,2001:240)这一战略要求“译者尽可能不去打扰作者,让读者向作者靠拢。”(Venuti,1995:19)归化可能保留源语的主要信息。异化的目的是使读者产生一种非凡的阅读体验。异化可以容纳外语的表达特点,将自身向外国文化靠拢,并将特殊的民族文化考虑在内。例如,如果将“岳飞庙和墓”翻译成英语,可以翻译为:“Yue Fei’s

英语论文 归化与异化翻译

2010届本科生毕业设计(论文) 毕业论文 Domestication or Foreignism-oriented Skills in Translation 学院:外国语学院 专业:姓名:指导老师:英语专业 xx 学号: 职称: xx 译审 中国·珠海 二○一○年五月

xx海学院毕业论文 诚信承诺书 本人郑重承诺:我所呈交的毕业论文Domestication or Foreignism-oriented Skills in Translation 是在指导教师的指导下,独立开展研究取得的成果,文中引用他人的观点和材料,均在文后按顺序列出其参考文献,论文使用的数据真实可靠。 承诺人签名: 日期:年月日

Domestication or Foreignism-oriented Skills in Translation ABSTRACT Translation, a bridge between different languages and cultures, plays an indispensable role in cross-culture communication. However, as a translator, we have to choose which strategy to deal with the cultural differences between the source language and the target language in the process of translation where there exists two major translation strategies--- domestication and foreignization. In this thesis, I will discuss these strategies and their application from translation, linguistics, and cross-cultural communication perspectives. In the thesis, I will first talk about the current research of the domestication and foreignization in the translation circle as well as point out the necessity for further research. Then, I will illustrate the relationship between linguistics and translation as well as between culture and translating and next systematically discuss these two translation strategies including their definitions, the controversy in history and their current studies. Besides, I will continue to deal with such neglected factors as may influence the translator’s choice of translation strategies: the type of the source text (ST), the translation purposes, the level of the intended readers, the social and historical background, the translator’s attitude and so on. Finally, from the linguistic and cultural perspectives, the thesis makes a comparative study of the application of domestication and foreignization by analyzing typical examples from the two English versions of Hong Lou Meng translated by Yang Xianyi and David Hawkes respectively. The thesis will conclude that these two translation strategies have their respective features and applicable value. I sincerely hope that this research into translation strategies will enlighten translators and make a little contribution to the prosperity of