31 De novo CNVs in bipolar affective disorder and schizophrenia

De novo CNVs in bipolar affective disorder and schizophrenia

Lyudmila Georgieva 1,Elliott Rees 1,Jennifer L.Moran 2,Kimberly D.Chambert 2,Vihra Milanova 3,Nicholas Craddock 1,Shaun Purcell 4,5,Pamela Sklar 4,5,Steven McCarroll 2,Peter Holmans 1,Michael C.O’Donovan 1,Michael J.Owen 1and George Kirov 1,?

1

Medical Research Council Centre for Neuropsychiatric Genetics and Genomics,Institute of Psychological Medicine and Clinical Neurosciences,Cardiff University,Cardiff,UK,2Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research,Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard,Cambridge,MA,USA,3Department of Psychiatry,Medical University,So?a,Bulgaria,4Division of

Psychiatric Genomics,Department of Psychiatry,Mount Sinai School of Medicine,New York,NY,USA and 5Psychiatric and Neurodevelopmental Genetics Unit,Massachusetts General Hospital,Boston,MA,USA

Received May 19,2014;Revised and Accepted July 17,2014

An increased rate of de novo copy number variants (CNVs)has been found in schizophrenia (SZ),autism and developmental delay.An increased rate has also been reported in bipolar affective disorder (BD).Here,in a larger BD sample,we aimed to replicate these ?ndings and compare de novo CNVs between SZ and BD.We used Illumina microarrays to genotype 368BD probands,76SZ probands and all their parents.Copy number var-iants were called by PennCNV and ?ltered for frequency (<1%)and size (>10kb).Putative de novo CNVs were validated with the z-score algorithm,manual inspection of log R ratios (LRR)and qPCR probes.We found 15de novo CNVs in BD (4.1%rate)and 6in SZ (7.9%rate).Combining results with previous studies and using a cut-off of >100kb,the rate of de novo CNVs in BD was intermediate between controls and SZ:1.5%in controls,2.2%in BD and 4.3%in SZ.Only the differences between SZ and BD and SZ and controls were signi?cant.The median size of de novo CNVs in BD (448kb)was also intermediate between SZ (613kb)and controls (338kb),but only the comparison between SZ and controls was signi?cant.Only one de novo CNV in BD was in a con-?rmed SZ locus (16p11.2).Sporadic or early onset cases were not more likely to have de novo CNVs.We conclude that de novo CNVs play a smaller role in BD compared with SZ.Patients with a positive family history can also harbour de novo mutations.

INTRODUCTION

Bipolar affective disorder (BD)has a life-time risk of 1%in the general population and a 10-fold increased risk in ?rst-degree relatives (1).The heritability estimates range between 59and 87%(2–4).It is a complex genetic disorder,with a high degree of genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity (5).Genome-wide association studies based on common genetic variants have identi?ed a number of loci at compelling levels of statistical support (6–10).It has been estimated that about a third of the genetic variance in risk is contributed by common alleles that are tagged by SNPs on genotyping arrays (11).

Rare,moderate to highly penetrant copy number variants (CNVs)have been clearly established as risk factors for several neuropsychiatric disorders:schizophrenia (SZ),autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability/developmental delay (ID/DD)(12–16).Therefore,CNVs may also account for some of the unexplained heritability of BD.Studies on BD have yielded con?icting results,with modest enrichments for CNVs in some studies but not in others (17–22).An enrichment of de novo CNVs in individuals with BD was ?rst reported by Malhotra et al .(21)This team identi?ed 10CNVs in 185pro-bands,a rate of 5.4%(or 4.3%rate per person,as 2probands had 2CNVs each),compared with 4CNVs in 426controls

?

To whom correspondence should be addressed at:Medical Research Council Centre for Neuropsychiatric Genetics and Genomics,Institute of Psychological Medicine and Clinical Neurosciences,Cardiff University,Cardiff CF244HQ,UK.Tel:+442920688465;Fax:+442920687068;Email:kirov@https://www.360docs.net/doc/5e15252243.html,

#The Author 2014.Published by Oxford University Press.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://www.360docs.net/doc/5e15252243.html,/licenses/by/4.0/),which permits unrestricted reuse,distribution,and reproduction in any medium,provided the original work is properly cited.

Human Molecular Genetics,2014,Vol.23,No.246677–6683

doi:10.1093/hmg/ddu379

Advance Access published on July 23,2014

(a rate of0.9%)suggesting that this class of variants is involved in the disorder,particularly in early-onset cases.More recently, Noor et al.(23)found8de novo CNVs among215BD probands, a rate of3.7%.No new control group was tested in that study,but the rate was considered increased compared with control rates from previous studies of1–2%.

We aimed to investigate the role of de novo CNVs in the aeti-ology of BD in the largest sample of BD parent-proband trios tested to date and compare them with de novo CNVs found in SZ patients.

RESULTS

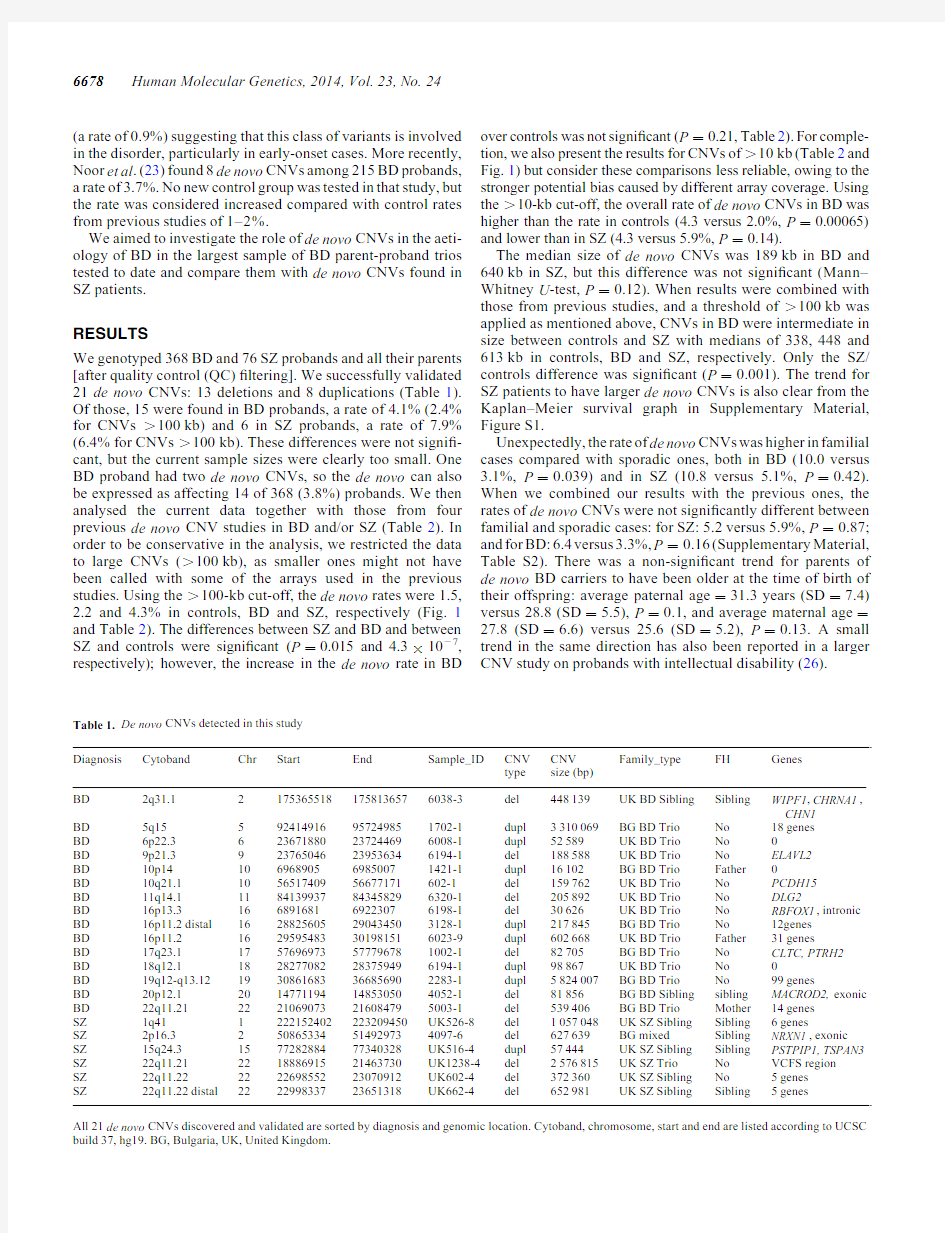

We genotyped368BD and76SZ probands and all their parents [after quality control(QC)?ltering].We successfully validated 21de novo CNVs:13deletions and8duplications(Table1). Of those,15were found in BD probands,a rate of4.1%(2.4% for CNVs.100kb)and6in SZ probands,a rate of7.9% (6.4%for CNVs.100kb).These differences were not signi?-cant,but the current sample sizes were clearly too small.One BD proband had two de novo CNVs,so the de novo can also be expressed as affecting14of368(3.8%)probands.We then analysed the current data together with those from four previous de novo CNV studies in BD and/or SZ(Table2).In order to be conservative in the analysis,we restricted the data to large CNVs(.100kb),as smaller ones might not have been called with some of the arrays used in the previous https://www.360docs.net/doc/5e15252243.html,ing the.100-kb cut-off,the de novo rates were1.5, 2.2and4.3%in controls,BD and SZ,respectively(Fig.1 and Table2).The differences between SZ and BD and between SZ and controls were signi?cant(P?0.015and4.3×1027, respectively);however,the increase in the de novo rate in BD over controls was not signi?cant(P?0.21,Table2).For comple-tion,we also present the results for CNVs of.10kb(Table2and Fig.1)but consider these comparisons less reliable,owing to the stronger potential bias caused by different array https://www.360docs.net/doc/5e15252243.html,ing the.10-kb cut-off,the overall rate of de novo CNVs in BD was higher than the rate in controls(4.3versus2.0%,P?0.00065) and lower than in SZ(4.3versus5.9%,P?0.14).

The median size of de novo CNVs was189kb in BD and 640kb in SZ,but this difference was not signi?cant(Mann–Whitney U-test,P?0.12).When results were combined with those from previous studies,and a threshold of.100kb was applied as mentioned above,CNVs in BD were intermediate in size between controls and SZ with medians of338,448and 613kb in controls,BD and SZ,respectively.Only the SZ/ controls difference was signi?cant(P?0.001).The trend for SZ patients to have larger de novo CNVs is also clear from the Kaplan–Meier survival graph in Supplementary Material, Figure S1.

Unexpectedly,the rate of de novo CNVs was higher in familial cases compared with sporadic ones,both in BD(10.0versus 3.1%,P?0.039)and in SZ(10.8versus5.1%,P?0.42). When we combined our results with the previous ones,the rates of de novo CNVs were not signi?cantly different between familial and sporadic cases:for SZ:5.2versus5.9%,P?0.87; and for BD:6.4versus3.3%,P?0.16(Supplementary Material, Table S2).There was a non-signi?cant trend for parents of de novo BD carriers to have been older at the time of birth of their offspring:average paternal age?31.3years(SD?7.4) versus28.8(SD?5.5),P?0.1,and average maternal age?27.8(SD?6.6)versus25.6(SD?5.2),P?0.13.A small trend in the same direction has also been reported in a larger CNV study on probands with intellectual disability(26).

Table1.De novo CNVs detected in this study

Diagnosis Cytoband Chr Start End Sample_ID CNV

type CNV

size(bp)

Family_type FH Genes

BD2q31.121753655181758136576038-3del448139UK BD Sibling Sibling WIPF1,CHRNA1,

CHN1

BD5q15592414916957249851702-1dupl3310069BG BD Trio No18genes

BD6p22.3623671880237244696008-1dupl52589UK BD Trio No0

BD9p21.3923765046239536346194-1del188588UK BD Trio No ELAVL2

BD10p1410696890569850071421-1dupl16102BG BD Trio Father0

BD10q21.1105651740956677171602-1del159762UK BD Trio No PCDH15

BD11q14.11184139937843458296320-1del205892UK BD Trio No DLG2

BD16p13.316689168169223076198-1del30626UK BD Trio No RBFOX1,intronic BD16p11.2distal1628825605290434503128-1dupl217845BG BD Trio No12genes

BD16p11.21629595483301981516023-9dupl602668UK BD Trio Father31genes

BD17q23.11757696973577796781002-1del82705BG BD Trio No CLTC,PTRH2

BD18q12.11828277082283759496194-1dupl98867UK BD Trio No0

BD19q12-q13.121930861683366856902283-1dupl5824007BG BD Trio No99genes

BD20p12.12014771194148530504052-1del81856BG BD Sibling sibling MACROD2,exonic BD22q11.212221069073216084795003-1del539406BG BD Trio Mother14genes

SZ1q411222152402223209450UK526-8del1057048UK SZ Sibling Sibling6genes

SZ2p16.3250865334514929734097-6del627639BG mixed Sibling NRXN1,exonic SZ15q24.3157728288477340328UK516-4dupl57444UK SZ Sibling Sibling PSTPIP1,TSPAN3 SZ22q11.21221888691521463730UK1238-4del2576815UK SZ Trio No VCFS region

SZ22q11.22222269855223070912UK602-4del372360UK SZ Sibling No5genes

SZ22q11.22distal222299833723651318UK662-4del652981UK SZ Sibling Sibling5genes

All21de novo CNVs discovered and validated are sorted by diagnosis and genomic location.Cytoband,chromosome,start and end are listed according to UCSC build37,hg19.BG,Bulgaria,UK,United Kingdom.

6678Human Molecular Genetics,2014,Vol.23,No.24

To provide a further comparison of CNVs between BD and SZ,we assessed how many CNVs (transmitted or de novo )were found in 15CNV regions previously implicated in SZ (12)in the BD and SZ probands in the current study (i.e.in samples not used in the discovery of these associations).The results are presented in Table 3.The overall rate of these CNVs in BD is signi?cantly lower (1.35%)than that in the SZ sample (9%)(Fisher Exact test,P ?0.0007),and on six occa-sions,they were not transmitted to BD probands from carrier parents.In contrast,there were no non-transmitted CNVs from this list in the SZ sample.No person had two CNVs from this list.One previous study on BD found an increased rate of singleton deletions in subjects with an onset of illness before the age of 18

years (17).Another one (21)found an increased rate of de novo CNVs in early-onset BD cases.In the present study,the mean age at onset among BD probands with and without de novos was practically identical (22.6versus 22.8years),with a similar dis-tribution of ages (Fig.2).

Gene pathway analyses in the combined datasets did not reveal an enrichment of BD de novo CNV hits relative to control de novo CNVs after controlling for multiple testing (Sup-plementary Material).

DISCUSSION

We have conducted the largest analysis of de novo CNVs in BD to date (Table 2).We analysed BD and SZ families together,in order to compare the de novo rates with the same methods and arrays.

Frequency of de novo CNVs in BD

De novo CNVs were found in 4.1%of BD probands.This rate is increased compared with controls from previous studies,but lower than the 7.9%in SZ in the current sample.To obtain a more meaningful comparison,we included in our analyses data from previous large studies on de novo CNVs in SZ,BD and controls.In order to minimise possible bias caused by differ-ent array resolutions used in the different studies,we analysed these differences for CNVs .100kb (as these are more likely to be detected by all arrays).Table 2and Figure 1show the rates in these phenotypes in the combined data.The rate in BD probands was intermediate between those in controls and SZ (1.5versus 2.2versus 4.3%),although the rates in BD were not signi?cantly different from controls.Despite the weak statistical support,both comparisons (with cut-offs of 10and 100kb)show

Table https://www.360docs.net/doc/5e15252243.html,parison of rates and sizes of CNVs with previous de novo CNV studies

N trios

N CNVs (%).10kb Median size in kb .10kb N CNVs (%).100kb Median size in kb .100kb Current study BD 36815(4.1%)1899(2.4%)448SZ

766(7.9%)6405(6.4%)653Malhotra et al .(21)BD 18510(5.4%)1375(2.7%)611SZ 1779(5.1%)3486(3.4%)824CON

4264(0.9%)411(0.2%)1425Kirov et al.(24)SZ 66234(5.1%)32125(3.8%)574CON

262359(2.2%)25946(1.8%)320Xu et al .(25)SZ 20017(8.5%)26012(7.9%)489CON

1592(1.3%)28042(1.3%)2804Noor et al .(23)BD

2158(3.7%)763(1.4%)418Totals/P -value BD 76833(4.3%)13317(2.2%)448SZ 111566(5.9%)35648(4.3%)613CON

3208

65(2.0%)25949(1.5%)338P -value,BD versus CON 0.000650.140.21

0.74P -value,SZ versus CON 1.4310290.54 4.3310270.001P -value,BD versus SZ

0.14

0.079

0.015

0.44

All rates refer to the number of CNVs in the sample (rather than the number of carriers of CNVs).CNVs on the X-chromosome are excluded.Signi?cant results are shown in

bold.

Figure https://www.360docs.net/doc/5e15252243.html,parison of the de novo rates for CNVs .10and .100kb in controls (CON),BD and SZ,based on the studies listed in Table 2.

Human Molecular Genetics,2014,Vol.23,No.246679

similar trends,with the rates of de novo CNVs in BD being inter-mediate between controls and SZ (Fig.1).Potential role of speci?c CNVs in BD

The trend we observed for an increased rate of de novo CNVs in BD compared with controls is consistent with a small propor-tion of these loci playing a role in the pathogenesis of the dis-order.The more likely candidate loci are the following:the

deletion at DLG2,a gene implicated in SZ (24)and BD (23);the duplication at 16p11.2,as it is also implicated in SZ and BD (13,21)[our proband with de novo duplication was among the cases used in the original case–control study that found an association with BD (13)];the duplication of the ‘distal 16p11.2’locus,as it is an ID locus,while the reciprocal deletion is both an SZ and ID locus (15,27);the deletion at PCDH15,as mutations in this gene can cause deafness and Usher syndrome Type IF (https://www.360docs.net/doc/5e15252243.html,/entry/602083),a disorder with a possibly increased rate of psychosis and behavioural problems (28,29).

CNVs in BD might be less pathogenic than those found in SZ Overall de novo CNVs tended to be smaller in BD (median of 448kb)than in SZ (median of 613kb)in the combined datasets (Table 2).The lack of signi?cance might be due to the small sample sizes,as the distribution of CNV sizes suggests a trend for CNVs in SZ to be larger (Supplementary Material,Fig.S1).Previous case–control studies in BD also report that the rate of very large (.1Mb)and rare (,1%)CNVs in BD is similar or even lower than that in controls (18,22).Only two dele-tions and six duplications in BD probands in the current study were .1Mb (rates of 0.54and 1.62%,respectively,including transmitted CNVs).These rates are lower than those in previous controls analysed by us with the same methods:among 11255controls in our recent study,we reported rates of 0.65and 1.95%,respectively (30).A smaller proportion of CNVs in BD probands were also found at 15loci that have been shown to be pathogenic for SZ and other neurodevelopmental disorders,either as de novo ,or inherited (Table 3).The cumulative rate of 1.35%of these CNVs in BD patients is close to the 0.96%rate we reported among 11255controls and lower than the 2.49%among 6882SZ patients in our recent study (30).The strongest difference between the two disorders is for 15q11.2deletions,which were not transmitted from three unaffected

Table 3.Transmission status of CNVs at loci implicated in SZ [according to our review of the literature (12)]Locus

Position in Mb BD (N ?371)SZ (N ?78)

1q21.1del chr1:14657–147391T from BD F 1q21.1dup chr1:14657–147391T from healthy M

NRXN1del chr2:5015–51261de novo 3q29del chr3:19573–19734WBS dup chr7:7274–7414VIPR2dup chr7:15882–1589415q11.2del

chr15:2280–23093NT from healthy parents 5T (one M is SZ)

Angelman/Prader–Willi dup chr15:2482–284315q13.3del chr15:3113–324816p13.11dup chr16:1551–16301T

2NT from healthy parents 16p11.2distal del chr16:2882–290516p11.2dup chr16:2964–30201de novo

1NT from healthy M 17p12del chr17:1416–15431T from healthy F 17q12del chr17:3481–362022q11.2del

chr22:1902–2026

1de novo Total in probands

5(1.35%);6NT

7(9%);0NT

The ‘Total in probands’include transmissions +de novos .

T/NT,transmitted/not transmitted from a parent;M,mother;F,

father.

Figure 2.Age at onset among BD probands with de novo CNVs (black columns)and without de novos (dashed columns).

6680Human Molecular Genetics,2014,Vol.23,No.24

parents to their BD offspring,whereas such deletions were trans-mitted from three parents(one affected with SZ)to?ve SZ off-spring(including two affected SZ sib-pairs).In our previous study on BD,we also found a particularly low rate of15q11.2 deletions among1697cases(0.18%)(18),which is even lower than the0.28%in population controls(12).All these observa-tions suggest that very large and rare CNVs,and those shown to increase risk for SZ,ID and DD,play at best a very modest role in BD.

Cases with a positive family history also have an increased rate of de novo CNVs

It has generally been assumed that sporadic cases are more likely to carry de novo CNVs than familial cases.To test whether de novo CNVs are more common in sporadic cases,we strati?ed the sample by history of BD/SZ/psychotic disorder in?rst-degree relatives and found that the de novo CNV rate is not sig-ni?cantly different between familial and sporadic cases;in fact, it was higher in familial cases in the current study(Supplemen-tary Material,Table S2).The?rst study of de novo CNVs in SZ reported that they occur more frequently in sporadic cases(25), but a subsequent study(21)found that the rates of de novo CNVs in BD and SZ cohorts were similar in sporadic and familial cases. In our previous study on SZ(24),we considered the family history as positive only if it was present in parents(reasoning that siblings can have independent de novo CNVs)and found a slightly higher rate in sporadic https://www.360docs.net/doc/5e15252243.html,bining all these studies and re-coding our previous data(24)to include cases with affected siblings as well,we?nd that the rate of de novo CNVs is similar in familial and sporadic cases:5.2versus 5.9%for SZ and6.4versus3.3%for BD,respectively(the increased rate in familial BD cases is not signi?cant,P?0.16). Two examples of de novo CNVs in family history-positive cases are particularly striking.The16p11.2duplication has a high penetrance of34%for any neurodevelopmental disorder (31)but was found in the daughter of a father who also suffers with a severe form of BD(being de novo,that mutation is not found in the father).The exonic NRXN1deletion[penetrance of32%for any disorder(31)]was found in a SZ proband from a multiply affected family:the proband’s sister had schizo-affective disorder,she was married to a BD patient and her daughter had BD.No other family member had a pathogenic CNV.

In conclusion,this study con?rms previous suggestions that very large and rare CNVs,especially those implicated in neuro-developmental disorders(such as most of the CNVs listed in Table3),play a lesser role in BD compared with SZ.However, we did observe a non-signi?cant trend for the rate of de novo CNVs to be higher in BD than in controls,suggesting that larger and more powerful studies might reveal a signi?cant excess.In addition,several of the loci impacted by de novo CNVs have been previously implicated in neuropsychiatric dis-orders,which enhance their credibility as candidates for BD. These include16p11.2,DLG2and PCDH15.Finally,we also observed an excess of de novo mutations in familial cases of major psychiatric disorders.With hindsight this should not be surprising,as disorders of complex genetic inheritance are not due to single gene defects,but to an accumulation of a number of susceptibility factors.MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

The total sample(after QC)?ltering consists of449probands:368 with BD(256from Bulgaria and112from the UK)and76with SZ (15from Bulgaria and61from the UK).Three hundred and eighty-one probands were from parent-offspring trios(342with BDand39withSZ),42werefrom families with2affected siblings (16with BD and26with SZ)and21(10BD and11SZ)were from families with more complex structures,including families with a mixture of diagnoses(Supplementary Material,Table S1).Pro-bands affected with schizoaffective disorder were excluded from this study.Probands with a history of psychosis in a sibling or parent(50with BD and37with SZ)were included,as none of the risk CNVs identi?ed to date is suf?ciently penetrant to fully explain the disorder in carriers(31),and therefore,we wanted to test whether familial cases can also have de novo CNVs.The pro-portion of affected sibling pairs with SZ from the UK is very high because part of this cohort was recruited as affected sib-pairs for linkage analysis,whereas all BD trios were recruited speci?cally for studying parent-offspring trios.

The recruitment of families in Bulgaria has been described before(24).Each proband had a history of hospitalisation and was interviewed with an abbreviated version of the Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry(SCAN)(32).Con-sensus best-estimate diagnoses were made according to DSM-IV criteria by two researchers.This recruitment also included SZ trios,which have been genotyped with Affymetrix arrays and reported previously(24),apart from some families with different diagnoses that are reported here.In the UK,the BD patients were recruited and interviewed in person by GK,using the same rating instruments.Consensus best-estimate diagnoses were made by two researchers(G.K.and N.C.),based on the interview and hospital notes.The SZ families from the UK were recruited as part of sib-pair and case–control collections.The main purpose for the inclusion of SZ probands in the current study is to compare in an unbiased way(using identical methods),the de novo CNV rate between BD and SZ,and also to enlarge the sample of family history-positive cases,where fewer data are available from previous studies.Ethics committee approval for the study was obtained from the relevant research ethics commit-tees and all individuals provided written informed consent for participation.A small proportion of the probands from the UK have been included as cases in previous case–control studies: 55BD probands are in the Grozeva et al.study(18)and29SZ probands in the Kirov et al.study(33);however,they were not evaluated for de novo https://www.360docs.net/doc/5e15252243.html,parisons with d e novo CNVs from healthy control populations were made with probands from three previous studies(21,24,25).

Genotyping of blood-derived DNA from all samples was performed at the Stanley Centre for Psychiatric Research at the Broad Institute of MIT,USA on two arrays:HumanOmni Express-12v1(referred further for short as‘OmniExpress array’),containing730525probes,and any poorly performing samples were re-genotyped on HumanOmniExpressExome-8v1 (‘Combo array’),containing951117probes.The Combo array contains SNPs from both the Omni Express array and the Illu-mina HumanExome-12v1_A(‘Exome array’);however,for the analysis of Combo array data,we only used the probes present on the OmniExpress array(N?699865).

Human Molecular Genetics,2014,Vol.23,No.246681

CNV calling and QC

Raw intensity data were processed using Illumina Genome Studio software(v2011.1).SNPs were clustered using the current samples,and LRR and B-allele frequencies were gener-ated for CNV detection.PennCNV(34)was used to call CNVs following the standard protocol and adjusting for GC content. Sample-level QC was performed using the QC metrics generated by PennCNV.These include:LRR standard deviation,B-allele frequency drift,wave factor and total number of CNVs called per person.Samples were excluded if for any one of these metrics they constituted an outlier in their source dataset (details not presented).All poorly performing samples were re-genotyped on Combo arrays.If one family member making up a trio was excluded,then we excluded the whole trio,thus excluding33families.

All individual CNVs also went through QC?ltering.First,raw CNVs in the same sample were joined together if the distance separating them was,50%of their combined https://www.360docs.net/doc/5e15252243.html,Vs were then excluded if they were either,10kb,covered by ,10probes,overlapped with low copy repeats by.50%of their length(using PLINK)(35)or had a probe density of .20kb per probe.The remaining CNVs from each dataset were then analysed together and CNV loci with a frequency of .1%were excluded using PLINK.The putative de novo CNVs were validated with the median z-score outlier method (24),software freely available at http://x004.psycm.uwcm.ac. uk/~dobril/z_scores_cnvs.The z-score histograms of CNVs with marginal z-scores were manually inspected.For all putative de novo CNVs,the LRR and B-allele frequencies were also visu-ally inspected using Illumina Genome Studiov2011.1software. Validation of all remaining putative de novo CNVs was per-formed using real-time PCR based on SYBR-Green I?uores-cence with at least three primer sets per CNV.All samples were ampli?ed using Sensimix kit(Bioline,UK),and data were analysed using Rotor-Gene Q series software.Each primer set was compared with a primer set outside the CNV which served as‘control’and data were normalized using delta Ct(cycle threshold)values.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary Material is available at HMG online.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the participants and clinicians who took part in the study.

Con?ict of Interest statement.None declared.

FUNDING

The work at Cardiff University was funded by Medical Research Council(MRC)Centre(G0800509)and Program Grants (G0801418)and an MRC PhD Studentship to E.R.Funding for the recruitment of trios in Bulgaria was provided by the Janssen Research Foundation in1999–2004,Ref:045856. Funding for the recruitment of BD samples in the UK was pro-vided by the Wellcome Trust as a Training Fellowship to G.K.in1996–1999,Ref:045856.The samples were genotyped at the Broad Institute,USA,funded by a philanthropic gift to the Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research.Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by Research Councils UK.

REFERENCES

1.Craddock,N.and Jones,I.(1999)Genetics of bipolar disorder.J.Med.

Genet.,36,585–594.

2.Lichtenstein,P.,Yip,B.H.,Bjo¨rk,C.,Pawitan,Y.,Cannon,T.D.,Sullivan,

P.F.and Hultman,C.M.(2009)Common genetic determinants of

schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in Swedish families:a population-based https://www.360docs.net/doc/5e15252243.html,ncet,373,234–239.

3.Smoller,J.W.and Finn,C.T.(2003)Family,twin,and adoption studies of

bipolar disorder.Am.J.Med.Genet.C Semin.Med.Genet.,123C,48–58.

4.McGuf?n,P.,Rijsdijk,F.,Andrew,M.,Sham,P.,Katz,R.and Cardno,A.

(2003)The heritability of bipolar affective disorder and the genetic

relationship to unipolar depression.Arch.Gen.Psychiatry,60,497–502.

5.Potash,J.B.,Toolan,J.,Steele,J.,Miller,E.B.,Pearl,J.,Zandi,P.P.,Schulze,

T.G.,Kassem,L.,Simpson,S.G.,Lopez,V.et al.(2007)The bipolar disorder phenome database:a resource for genetic studies.Am.J.Psychiatry,164, 1229–1237.

6.Ferreira,M.A.,O’Donovan,M.C.,Meng,Y.A.,Jones,I.R.,Ruderfer,D.M.,

Jones,L.,Fan,J.,Kirov,G.,Perlis,R.H.,Green,E.K.et al.(2008)

Collaborative genome-wide association analysis supports a role for ANK3 and CACNA1C in bipolar disorder.Nat.Genet.,40,1056–1058.

7.Cichon,S.,Mu¨hleisen,T.W.,Degenhardt,F.A.,Mattheisen,M.,Miro′,X.,

Strohmaier,J.,Steffens,M.,Meesters,C.,Herms,S.,Weingarten,M.et al.

(2011)Genome-wide association study identi?es genetic variation in

neurocan as a susceptibility factor for bipolar disorder.Am.J.Hum.Genet., 88,372–381.

8.Group,P.G.C.B.D.W.(2011)Large-scale genome-wide association

analysis of bipolar disorder identi?es a new susceptibility locus near ODZ4.

Nat.Genet.,43,977–983.

9.Green,E.K.,Grozeva,D.,Forty,L.,Gordon-Smith,K.,Russell,E.,Farmer,

A.,Hamshere,M.,Jones,I.R.,Jones,L.,McGuf?n,P.et al.(2013)

Association at SYNE1in both bipolar disorder and recurrent major

depression.Mol.Psychiatry,18,614–617.

10.Green,E.K.,Hamshere,M.,Forty,L.,Gordon-Smith,K.,Fraser,C.,Russell,

E.,Grozeva,D.,Kirov,G.,Holmans,P.,Moran,J.L.et al.(2013)Replication

of bipolar disorder susceptibility alleles and identi?cation of two novel

genome-wide signi?cant associations in a new bipolar disorder case-control sample.Mol.Psychiatry,18,1302–1307.

11.Lee,S.H.,Ripke,S.,Neale,B.M.,Faraone,S.V.,Purcell,S.M.,Perlis,R.H.,

Mowry,B.J.,Thapar,A.,Goddard,M.E.,Witte,J.S.et al.(2013)Genetic relationship between?ve psychiatric disorders estimated from genome-wide SNPs.Nat.Genet.,45,984–994.

12.Rees,E.,Walters,J.T.,Georgieva,L.,Isles,A.R.,Chambert,K.D.,Richards,

A.L.,Mahoney-Davies,G.,Legge,S.E.,Moran,J.L.,McCarroll,S.A.et al.

(2014)Analysis of copy number variations at15schizophrenia-associated loci.Br.J.Psychiatry,204,108–114.

13.McCarthy,S.E.,Makarov,V.,Kirov,G.,Addington,A.M.,McClellan,J.,

Yoon,S.,Perkins,D.O.,Dickel,D.E.,Kusenda,M.,Krastoshevsky,O.et al.

(2009)Microduplications of16p11.2are associated with schizophrenia.

Nat.Genet.,41,1223–1227.

14.Malhotra,D.and Sebat,J.(2012)CNVs:harbingers of a rare variant

revolution in psychiatric genetics.Cell,148,1223–1241.

15.Girirajan,S.,Rosenfeld,J.A.,Coe,B.P.,Parikh,S.,Friedman,N.,Goldstein,

A.,Filipink,R.A.,McConnell,J.S.,Angle,

B.,Meschino,W.S.et al.(2012)

Phenotypic heterogeneity of genomic disorders and rare copy-number

variants.N.Engl.J.Med.,367,1321–1331.

16.Sanders,S.J.,Ercan-Sencicek,A.G.,Hus,V.,Luo,R.,Murtha,M.T.,

Moreno-De-Luca,D.,Chu,S.H.,Moreau,M.P.,Gupta,A.R.,Thomson,S.A.

et al.(2011)Multiple recurrent de novo CNVs,including duplications of the 7q11.23Williams syndrome region,are strongly associated with autism.

Neuron,70,863–885.

17.Zhang,D.,Cheng,L.,Qian,Y.,Alliey-Rodriguez,N.,Kelsoe,J.R.,

Greenwood,T.,Nievergelt,C.,Barrett,T.B.,McKinney,R.,Schork,N.et al.

(2009)Singleton deletions throughout the genome increase risk of bipolar disorder.Mol.Psychiatry,14,376–380.

6682Human Molecular Genetics,2014,Vol.23,No.24

18.Grozeva,D.,Kirov,G.,Ivanov,D.,Jones,I.R.,Jones,L.,Green,E.K.,

St Clair,D.M.,Young,A.H.,Ferrier,N.,Farmer,A.E.et al.(2010)Rare copy number variants:a point of rarity in genetic risk for bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.Arch.Gen.Psychiatry,67,318–327.

19.McQuillin,A.,Bass,N.,Anjorin,A.,Lawrence,J.,Kandaswamy,R.,Lydall,

G.,Moran,J.,Sklar,P.,Purcell,S.and Gurling,H.(2011)Analysis of genetic

deletions and duplications in the University College London bipolar disorder case control sample.Eur.J.Hum.Genet.,19,588–592.

20.Priebe,L.,Degenhardt,F.A.,Herms,S.,Haenisch,B.,Mattheisen,M.,

Nieratschker,V.,Weingarten,M.,Witt,S.,Breuer,R.,Paul,T.et al.(2012) Genome-wide survey implicates the in?uence of copy number variants

(CNVs)in the development of early-onset bipolar disorder.Mol.Psychiatry, 17,421–432.

21.Malhotra,D.,McCarthy,S.,Michaelson,J.J.,Vacic,V.,Burdick,K.E.,

Yoon,S.,Cichon,S.,Corvin,A.,Gary,S.,Gershon,E.S.et al.(2011)High frequencies of de novo CNVs in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.Neuron, 72,951–963.

22.Grozeva,D.,Kirov,G.,Conrad,D.F.,Barnes,C.P.,Hurles,M.,Owen,M.J.,

O’Donovan,M.C.and Craddock,N.(2013)Reduced burden of very large and rare CNVs in bipolar affective disorder.Bipolar Disord.,15,893–898.

23.Noor,A.,Lionel,A.C.,Cohen-Woods,S.,Moghimi,N.,Rucker,J.,Fennell,

A.,Thiruvahindrapuram,

B.,Kaufman,L.,Degagne,B.,Wei,J.et al.(2014)

Copy number variant study of bipolar disorder in Canadian and UK

populations implicates synaptic genes.Am.J.Med.Genet.B

Neuropsychiatr.Genet.,165B,303–313.

24.Kirov,G.,Pocklington,A.J.,Holmans,P.,Ivanov,D.,Ikeda,M.,Ruderfer,

D.,Moran,J.,Chambert,K.,Toncheva,D.,Georgieva,L.et al.(2012)De

novo CNV analysis implicates speci?c abnormalities of postsynaptic

signalling complexes in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia.Mol.Psychiatry, 17,142–153.

25.Xu,B.,Roos,J.L.,Levy,S.,van Rensburg,E.J.,Gogos,J.A.and

Karayiorgou,M.(2008)Strong association of de novo copy number

mutations with sporadic schizophrenia.Nat.Genet.,40,880–885.

26.Hehir-Kwa,J.Y.,Rodr?′guez-Santiago,B.,Vissers,L.E.,de Leeuw,N.,

Pfundt,R.,Buitelaar,J.K.,Pe′rez-Jurado,L.A.and Veltman,J.A.(2011)

De novo copy number variants associated with intellectual disability have

a paternal origin and age bias.J.Med.Genet.,48,776–778.

27.Guha,S.,Rees,E.,Darvasi,A.,Ivanov,D.,Ikeda,M.,Bergen,S.E.,

Magnusson,P.K.,Cormican,P.,Morris,D.,Gill,M.et al.(2013)Implication of a rare deletion at distal16p11.2in schizophrenia.JAMA Psychiatry,70, 253–260.

28.Domanico,D.,Fragiotta,S.,Trabucco,P.,Nebbioso,M.and Vingolo,E.M.

(2012)Genetic analysis for two Italian siblings with usher syndrome and schizophrenia.Case Rep.Ophthalmol.Med.,2012,380863.

29.Rao,N.P.,Danivas,V.,Venkatasubramanian,G.,Behere,R.V.and

Gangadhar,B.N.(2010)Comorbid bipolar disorder and Usher syndrome.

Prim.Care Companion J.Clin.Psychiatry,12.

30.Rees,E.,Walters,J.T.,Chambert,K.D.,O’Dushlaine,C.,Szatkiewicz,J.,

Richards,A.L.,Georgieva,L.,Mahoney-Davies,G.,Legge,S.E.,Moran, J.L.et al.(2014)CNV analysis in a large schizophrenia sample implicates deletions at16p12.1and SLC1A1and duplications at1p36.33and CGNL1.

Hum.Mol.Genet.,23,1669–1676.

31.Kirov,G.,Rees,E.,Walters,J.T.,Escott-Price,V.,Georgieva,L.,Richards,

A.L.,Chambert,K.D.,Davies,G.,Legge,S.E.,Moran,J.L.et al.(2014)The

penetrance of copy number variations for schizophrenia and developmental delay.Biol.Psychiatry,75,378–385.

32.Wing,J.K.,Babor,T.,Brugha,T.,Burke,J.,Cooper,J.E.,Giel,R.,Jablenski,

A.,Regier,D.and Sartorius,N.(1990)SCAN.Schedules for clinical

assessment in neuropsychiatry.Arch.Gen.Psychiatry,47,589–593. 33.Kirov,G.,Grozeva,D.,Norton,N.,Ivanov,D.,Mantripragada,K.K.,

Holmans,P.,Craddock,N.,Owen,M.J.,O’Donovan,M.C.,Consortium,I.S.

et al.(2009)Support for the involvement of large copy number variants in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia.Hum.Mol.Genet.,18,1497–1503.

34.Wang,K.,Li,M.,Hadley,D.,Liu,R.,Glessner,J.,Grant,S.F.,Hakonarson,

H.and Bucan,M.(2007)PennCNV:an integrated hidden Markov model

designed for high-resolution copy number variation detection in

whole-genome SNP genotyping data.Genome Res.,17,1665–1674.

35.Purcell,S.,Neale,B.,Todd-Brown,K.,Thomas,L.,Ferreira,M.A.,Bender,

D.,Maller,J.,Sklar,P.,de Bakker,P.I.,Daly,M.J.et al.(2007)PLINK:a tool

set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses.

Am.J.Hum.Genet.,81,559–575.

Human Molecular Genetics,2014,Vol.23,No.246683

Nova 存储功能介绍

Nova 软文介绍 Nova系列分为入门级和专业级存储:入门级存储系列有丰富的功能和很高的性能,采用1.2GHz IOP ,PCIe2.0带宽、SAS存储采用2个6Gb SAS 主机接口,ISCSI存储则采用4个1Gb ISCSI主机接口,单制器配置。机架式机箱可以安装12/16/24块6Gb SAS 或SATA硬盘和通过RAID 级别0,1,3,5,6,10 等保护所有数据,友好的图形用户界面和快速安装程序,使非技术用户在配置一个基本的存储设置,不到5个步骤即可简单完成。存储容量的扩展可以通过mini SAS 扩展端口连接一台JBOD扩展箱进行扩充存储容量。适合中小企业数据管理以及视频监控应用系统最理想的存储解决方案。为客户寻找具有价格竞争力的存储解决方案

Nova专业级存储采用新一代8Gb FC和6Gb SAS技术来平衡性能,混合主机接口和丰富的功能,采用1.2GHz IOP ,PCIe2.0带宽、FC存储采用4/8个8Gb FC主机接口和2/4 1G ISCSI主机接口,SAS存储则采用2/4个6Gb SAS主机接口和2/4 1G ISCSI主机接口,单控制器和双控制器配置。机架式机箱可以安装 12/16/24块6Gb SAS 或SATA硬盘和通过RAID 级别0,1,3,5,6,10等保护所有数据,友好的图形用户界面和快速安装程序,使非技术用户在配置一个基本的存储设置,不到5个步骤即可简单完成。存储容量的扩展可以通过mini SAS 扩展端口连接一台JBOD扩展箱进行扩充存储容量。使它成为一个非常适合高性能要求的数字内容创建和企业的虚拟化环境。 功能与优势 1.模块化设计:允许自定义配置,适合任何环境下的性能和容量要求; 2.高性能: NOVA专业级FC主机读写可达3200MB/秒高I/O带宽,SAS主机可 达3000MB/Sec高I/O带宽,让更多的数据流,和更多的用户同时工作,能满足大部份应用(入门级ISCSI 主机接口读写可达可达400M,适合中小企业和监控等应用);

摘要对微观经济学的概念和基本理论框架进行简单介绍,阐述当.

摘要: 对微观经济学的概念和基本理论框架进行简单介绍,阐述当前微观经济学所研究的基本问题、方法等,介绍微观经济学的基本假设和研究方法,最后简要指出当前微观经济学理论中存在的一些问题及理论发展。 关键词:微观经济学; 框架; 缺陷与发展

1 微观经济学的基本概念及其理论框架 1.1 微观经济学的基本概念 我们现在所学的微观经济学又称现代微观经济学,主要以马歇尔的新古典经济理论为框架,即在给定资源稀缺程度或生产力条件下,以单个经济单位(消费者、厂商、要素所有者和政府)为研究对象,通过研究单个经济单位行为和相应的经济变量单项数值的决定来说明价格机制如何解决资源配置问题,同时也将古典经济框架下的一些问题:分工与专业化及组织结构重新引入新古典经济理论为框架加以分析和讨论,如规模经济、范围经济、学习效应、科斯定理等,当然随着理论的深入发展和现实解释的需要也引进一些新的理论(信息经济学、博弈论、市场失灵、政府失灵、不确定条件下的消费选择等),以对新古典经济理论为框架进行重要的补充的一门社会科学。 1.2 微观经济学的基本理论框架(见图1) 图1 新古典框架下的微观经济学 2 微观经济学的基本问题及其根本解决 一是微观经济学的基本问题主要是生产什么、生产多少和如何生产和为谁生产。 二是基本问题的根本解决方法有:第一,资源配置的有效性。由于资源是稀缺的,在资源配置时既要考虑其目标也要考虑其效率,因为资源配置目标的实现依赖于资源配置效率的不断提高,同时资源配置的效率直接影响到一个社会的经济效率;第二,资源配置的方式。主要有计划、市场、风俗习惯等。 3 微观经济学的基本假设及其研究方法 3.1 微观经济学的基本假设

诺和诺德产品介绍

诺和诺德公司(novo nordisk)是一家致力于人类健康、以先进的生物技术造福患者、医生和社会的世界领先生物制药公司。诺和诺德公司在行业内拥有最为广泛的糖尿病治疗产品,其中包括最先进的胰岛素给药系统产品,80多年来一直是世界糖尿病研究和药物开发领域的主导。此外,诺和诺德还在止血管理、生长保健激素以及激素替代疗法等多方面居世界领先地位。诺和诺德总部位于丹麦首都哥本哈根,现今在全球79个国家设有分支机构,6个国家设有生产厂,员工超过26,300名,销售遍及180个国家。 诺和灵胰岛素:是短效胰岛素和中效胰岛素混合制剂,需要餐前半小时注射,作用时间较长,容易出现下一餐前低血糖; 诺和锐胰岛素:是超短效胰岛素类似物和中效胰岛素混合制剂,餐前10分钟内注射即可,作用更快,有效控制餐后血糖同时,不易出现下一餐前低血糖。 诺和锐30(Novomix30 ) 本品主要成份及其化学名称为:本品含30%可溶性门冬胰岛素和70%精蛋白门冬胰岛素,100U/ml,其活性成份为门冬胰岛素(通过基因重组技术,利用酵母生产的)。1单位(1U)相当于6nmol,0.035mg不含盐的无水门冬胰岛素。 优泌林70/30 (精蛋白锌重组人胰岛素混合注射液) 主要成份:30%重组人胰岛素(常规人胰岛素) 70%精蛋白锌重组人胰岛素(中效人胰岛素)

优泌乐(赖脯胰岛素注射液) 诺和锐特充和诺和锐30特充有什么区别? 首先,特充是指剂型,是相对于笔芯说的。是把笔芯预填充进一根简易的笔里面,打完抛弃的。 其次,诺和锐是一种改变了人胰岛素分子结构的速效胰岛素,它的起效更快,回落更快,可以紧邻餐前注射,控制餐后血糖。而诺和锐30是有30%的诺和锐,另外有70%是与精蛋白结晶的诺和锐,这70%的成分由于结晶所以释放的非常缓慢,目的是控制空腹血糖。 (注:文档可能无法思考全面,请浏览后下载,供参考。可复制、编制,期待你的好评与关注)

高通量测序常用名词解释

什么是高通量测序? 高通量测序技术(High-throughput sequencing,HTS)是对传统Sanger测序(称为一代测序技术)革命性的改变, 一次对几十万到几百万条核酸分子进行序列测定, 因此在有些文献中称其为下一代测序技术(next generation sequencing,NGS )足见其划时代的改变, 同时高通量测序使得对一个物种的转录组和基因组进行细致全貌的分析成为可能, 所以又被称为深度测序(Deep sequencing)。 什么是Sanger法测序(一代测序) Sanger法测序利用一种DNA聚合酶来延伸结合在待定序列模板上的引物。直到掺入一种链终止核苷酸为止。每一次序列测定由一套四个单独的反应构成,每个反应含有所有四种脱氧核苷酸三磷酸(dNTP),并混入限量的一种不同的双脱氧核苷三磷酸(ddNTP)。由于ddNTP 缺乏延伸所需要的3-OH基团,使延长的寡聚核苷酸选择性地在G、A、T或C处终止。终止点由反应中相应的双脱氧而定。每一种dNTPs和ddNTPs的相对浓度可以调整,使反应得到一组长几百至几千碱基的链终止产物。它们具有共同的起始点,但终止在不同的的核苷酸上,可通过高分辨率变性凝胶电泳分离大小不同的片段,凝胶处理后可用X-光胶片放射自显影或非同位素标记进行检测。 什么是基因组重测序(Genome Re-sequencing) 全基因组重测序是对基因组序列已知的个体进行基因组测序,并在个体或群体水平上进行差异性分析的方法。随着基因组测序成本的不断降低,人类疾病的致病突变研究由外显子区域扩大到全基因组范围。通过构建不同长度的插入片段文库和短序列、双末端测序相结合的策略进行高通量测序,实现在全基因组水平上检测疾病关联的常见、低频、甚至是罕见的突变位点,以及结构变异等,具有重大的科研和产业价值。 什么是de novo测序 de novo测序也称为从头测序:其不需要任何现有的序列资料就可以对某个物种进行测序,利用生物信息学分析手段对序列进行拼接,组装,从而获得该物种的基因组图谱。获得一个物种的全基因组序列是加快对此物种了解的重要捷径。随着新一代测序技术的飞速发展,基因组测序所需的成本和时间较传统技术都大大降低,大规模基因组测序渐入佳境,基因组学研究也迎来新的发展契机和革命性突破。利用新一代高通量、高效率测序技术以及强大的生物信息分析能力,可以高效、低成本地测定并分析所有生物的基因组序列。 什么是外显子测序(whole exon sequencing) 外显子组测序是指利用序列捕获技术将全基因组外显子区域DNA捕捉并富集后进行高通量测序的基因组分析方法。外显子测序相对于基因组重测序成本较低,对研究已知基因的SNP、Indel等具有较大的优势,但无法研究基因组结构变异如染色体断裂重组等。 什么是mRNA测序(RNA-seq) 转录组学(transcriptomics)是在基因组学后新兴的一门学科,即研究特定细胞在某一功能状态下所能转录出来的所有RNA(包括mRNA和非编码RNA)的类型与拷贝数。Illumina 提供的mRNA测序技术可在整个mRNA领域进行各种相关研究和新的发现。mRNA测序不对引物或探针进行设计,可自由提供关于转录的客观和权威信息。研究人员仅需要一次试验即可快速生成完整的poly-A尾的RNA完整序列信息,并分析基因表达、cSNP、全新的转录、全新异构体、剪接位点、等位基因特异性表达和罕见转录等最全面的转录组信息。简单的样

临床研究常用统计方法概述

临床研究常用统计方法概述 金雪娟周俊时智英葛均波 (复旦大学附属中山医院,上海市心血管病研究所,上海200032) 经过周密设计和科学实施的临床研究还需要规范的数据管理和统计分析,才能得到可靠的结论。随着计算机技术和统计分析软件发展,近年来,统计理论和方法发展非常迅速。临床医师日常繁忙的工作使得他们很少有时间系统学习医学统计理论,及时了解一些实用、有效的新方法。在此,我们介绍目前临床研究最常用的一些统计分析方法,以实用、易懂为原则,重点综述各种方法的适用条件。 1 几个基本概念和统计量 1.1 数据的类型 数据(Data)是统计分析的基础。统计分析方法的选择取决于不同的数据类型。最常见的数据类型有两种,分类数据(Categorical Data)或称定性数据(Qualitative Data)和定量数据(Qulantitative Data) 或称计量数据(Numerical Data)。 分类数据类型:分类数据的分层大于2时,又称为多分类数据(Polytomous Data)。分类数据类型有无序(Nominal Categorial)和有序(Ordinal Categorieal)。无序数据如性别(男、女)、血型(A、B、O、AB 型)等。有序数据如肿瘤的分级(I级、II级、III级)、疼痛的程度(轻、中、重)等,以及在临床研究设计中,经常看到的“非常好、好、一般、差”这样的数据类型。不同类型的分类数据在统计分析方法上也不同,并不是大家所熟悉的x2检验所能全部涵盖的。 定量数据类型:包括连续性数据(Continuous Data),如身高、体重以及不连续性数据(Discrete Data),如妇女的产次,疾病的复发次数等。 1.2 常用的描述性统计量 最常用的描述集中趋势的统计量为算术均数(Arithmetic Mean),但其值易受极端值影响。可以采用 中位数(Median)、修整均数(Trimmed Mean,去除最大和最小值后的算术均数)或Winsorized均数(Winsorized Mean,极端值用最接近的非极端值替代后的算术均数)来代替。对于数值呈几何分布的资料,则可采用几何均数(Geometric Mean)。 临床研究论文中常采用均数±标准差或均数±标准误来表示定量数据的分布特征。标准差(Standard Deviation)为方差(Variance)的平方根,表示个体数值与样本均数间的离散程度;标准误(Standard Error)为均数的标准差,表示样本统计量与总体参数间的离散程度,标准误越小,总体均数的95%可信区间(confident interval,CI)越窄,也就是说样本均数对总体均数的代表性越好。虽然不同的统计学家对论文中应该引用哪种表达方式有争议,但两种方式均用于描述正态分布的计量数据。在医学论文中,采用标准差或标准误应该说明。对于非对称数据只用均数±标准差或标准误表达是不恰当的,可以采用中位数结合四分位数间距(Inter-quartile Range)表示。 1.3 显著性水平(a)和P值

公司LOG

公司介绍: 联想电脑L O G的含义: 联想品牌定位;“科技创造自由”同时包含了如下品牌特性:诚信创新有活力优质专业的服务。 这个主题是通过品牌名称和标识同时在文字和现象上体现出来的。 lenovo 读成【len,neueu】,发音上和联想的联相近,而novo是拉丁语,译为“新的,创新”。Lenovo可演绎为“创新的联想”或“联想的创新”。整个标识采用现代“sans serit”字体,以达到设计简洁和易读的目的。在”e”上向上倾斜的一笔暗示着联想在提升客户生活和工作质量中都占有很重要的地位。同时,标识采用独居现代感的蓝色,意味着专业企业精神和科技。 联想电脑L O G的发展史: 1988年联想(HK-0992)在香港创立时早已知道市场上有很多Legend公司,但联想当时并没有想到现在规模如此庞大,当联想进军国际时“Legend”竟成为绊脚石,联想将“Legend”更名为“Lenovo”,成为进军国际的第一步,象征着联想从“传奇”走向“创新”的里程。 50年代末期日本“东京通讯工业公司”创始人盛田昭夫平认为,公司名称外国人不容易念,决定改名为 Sony(JP-6758;新力索尼),同时希望改变日本产品在国际间品质低劣的形象。据北京晨报报导,40多年后在大陆一家公司正做着类似的事情,将“Legend”换成“ Lenovo”,联想复制Sony的开始,希望也能复制Sony 今日的辉煌成绩。 联想在2001年计划走向国际化发展时发现“Legend ”成为海外扩张的绊脚石。联想集团助理总裁李岚表示,“Legend”这个名字在欧洲几乎所有国家都被注册了,注册范围涵盖计算机、食品、汽车等各个领域。 联想总裁杨元庆在解读这个全新的字母组合时表示,“novo”是一个拉丁词根,代表“新意”,“le”取自原先的“Legend”,承继“传奇”之意,整个单词寓意为“创新的联想”。报导指出,打江山时需要缔造“传奇”,想基业常青则要

临床科研设计报告书的撰写~final

临床医学研究项目申报书的撰写 第一节概述 一、科学研究的基本程序 二、临床科研类型 三、科研项目申请前的准备 第二节研究设计报告书的基本内容与撰写方法 一、项目名称及摘要 二、立项依据 三、研究目标、研究内容及拟解决的关键科学问题 四、研究方案与可行性分析 五、项目的特色与创新之处 六、年度研究计划及预期研究结果 七、研究基础与研究团队介绍 八、医学伦理学问题 九、经费预算 十、对照检查提纲 科学研究的本质是创造知识,从事新知识的生产,因此科学研究工作是一种非常复杂的、难度较高的脑力劳动,它具有继承性、创造性、探索性等基本特点。临床医学是一门理论进展快且实践性强的学科,临床医学科学研究对推动临床医学发展的作用越来越明显。如何做好临床医学的科学研究,提升临床医学在疾病诊治、预后、病因学等方面的研究水平,是每一位临床医生和临床医学学生面临的挑战。因此,在了解临床医学科学研究的种类及研究基本程序的基础上,掌握临床医学研究项目申报书要领,撰写出高质量的申报书,是医院学术水平和研究能力的反应,是学科发展的标志,也是每一位临床医学工作者基本素质的体现。

第一节概述 一、科学研究的基本程序 科学研究的全过程包括提出问题、验证假说和得出结论。其基本程序及主要步骤包括,查阅文献、提出临床医学科学问题、凝练科学问题、提出科学假说、制定研究计划及设计研究方案,撰写项目申报书,获得项目的资助,实验观察或调查、研究资料的整理与数据处理、总结分析、归纳研究结论、撰写研究报告及其推广应用等。 二、临床科研类型 要撰写高质量的临床医学研究项目申报书,首先要了解临床科研类型,按临床医学科学研究的任务来源、科技活动类型及研究内容可归纳为以下几方面。 按任务来源分类可分为纵向科研任务、横向科研任务及自由选题项目。 1.纵向科研任务是指各级政府主管部门下达的课题及项目,包括国家自然科学基金委员会设立的各类科学研究基金,政府管理部门科研基金,如科技部卫生部的科学研究基金,以及单位科研基金。 2.横向科研任务是以横向科技合同为依据的,它主要由企业、事业单位及其它机构委托进行,研究经费一般由委托单位提供。 3.自由选题是根据学科发展和科技人员的专长,结合医疗卫生工作的实际需要由科技人员自己提出的研究课题。 按科技活动类型分类,有基础研究、应用研究及发展研究。 1.基础研究是以认识自然现象,探索自然规律为目的,没有或者只有笼统的社会应用设想的研究活动。 2.应用研究主要针对某个特定的有实际应用价值的目标开展的研究。 3.发展研究也称开发研究,是运用基础研究和应用研究的知识,推广新材料、新产品、新设计、新流程和新方法,或对之进行重大的、实质性改进的创造活动。 三、科研项目申请前的准备 1.文献调研文献查阅是课题选择的前提,是产生或形成临床医学科学问题假设的前提,通过文献查阅,了解本学科的整体发展水平,当前学科研究的热

理财的基本概念

理财的基本概念 1、理财概念 理财是一个范畴很广的概念。从理财的主体来说,个人、家庭、公司、政府部门至国家等都有理财活动,但我们在此阐述的主要是个人或家庭理财。个人理财、家庭理财实际上是同一回事(只是由于个人理财多指结婚前的个人理财行为,而家庭理财是结婚成家后的家庭理财行为)。在国外,一般叫个人理财;在国内,我们认为叫家庭理财比较合适,因为中国是一个重视家庭,家庭观念比较重的国家,以家庭为主体进行理财的活动更加普遍。所以,在本书中提到理财说的多是家庭理财。 2、个人(家庭)理财概念 个人(家庭)理财就是管理自己和自己家庭的财富,进而提高财富效能的经济活动。理财也就是对资本金和负债资产的科学合理的运作。通俗的来说,理财就是赚钱、省钱、花钱之道,理财就是打理钱财。 个人(家庭)理财是一门新兴的实用科学,它是以经济学为指导(追求利益最大化目标)、以会计学为基础(客观忠实记录)、以财务学为手段(计划与满足未来财务需求、维持资产负债平衡)的边缘科学。 个人(家庭)理财貌似一件非常平凡的事情,实际上却很有学问。我认为:个人(家庭)理财既是一门科学,也是一门学问。我们要以科学、理性的态度来对待它。只有这样,才能最终实现我们理财的目标。 3、理财的综合涵义 1)理财是打理一生的财富。是以对财富持之以恒的追求为目标,而不仅仅是为了解决眼前的燃眉之急。 2)理财是现金流量管理。每个人一出生就需要化钱来满足自己的需求(现金流出)、也需要赚钱来来养活自己(现金流入)。因此不管现在是否有钱,每个人都需要理财,每个人都都不得不面对理财。事实上,许多人每月的支出计划,投资计划、还贷透支行为和开源节流的行为都是在进行投资理财,只是你可能没有意识到罢了。 3)理财涵盖了风险管理。因为未来具有不确定性,隐含各类的风险,包括人身风险、财产风险和市场风险,这都会影响到每个人的现金流入(收入中断风险)和现金流出(费用递增风险)。所以,理财从另外一个角度来说就是对风险进行控制和管理。 4、个人(家庭)理财的理财途径 (1)赚钱收入。人的一生的收入包含运用个人资源所产生的工作收入及运用金钱资源所产生的理财收入;工作收入是靠人赚钱,理财收入是用钱赚钱,由此可知理财的范围比赚钱与投资都还要广。

新百伦公司简介

新百伦(New Balance)战略营销分析 目录 一.公司简介 1.公司文化 2.公司业绩现状 3.产品简介 二.战略分析部分(PEST) 1.政治 2.经济 3.社会 4.技术 三、战略制定部分 1.新百伦的SWOT分析 2.文化发展策略 3.品牌运作策略 4.营销策略 四、新百伦的4P分析 五、新百伦的行业分析 六.对新百伦的几点建议

一、公司简介 1906年,New Balance创立于美国波士顿,专门替脚型特殊的人生产运动鞋。一直以来,新百伦(New Balance)公司极为用心的致力于制鞋工艺。至今,一个持续100多年的品牌,仍然不断以新兴的科技,开发更符合人体工学的鞋款。现已成为众多成功企业家和政治领袖爱用的品牌,在美国及许多国家被誉为“总统慢跑鞋”,“慢跑鞋之王”。于2003年正式登陆中国。 1.新百伦公司文化 新百伦New Balance公司拥有其独特的文化: 坚持出品多宽度、多高度的鞋款:这是针对人性出发的设计,也是最基本的关怀,带给每一位消费者最舒适贴近的鞋型。 New Balance不与运动明星签约。因为适合明星的鞋,不一定适合大部分的消费者穿着,所以New Balance公司将费用投入在产品的研发上,以提高产品质量,增加顾客满意。New Balance相信“鞋子就是最好的代言人”。 2.新百伦业绩状况 目前,美国市场仍然是新百伦的第一大市场,中国市场是新百伦的第三大市场,仅次于日本市场,2009年,新百伦在中国大陆市场的销售增长达40%;而新百伦专业跑步鞋的销售增长更是达到80%。2009年,大中华区营业额达9.67亿欧元。此前有媒体援引业内观察人士的估计,大陆市场大约占阿迪达斯大中华区营业额的84%,据此计算,阿迪达斯在大陆市场的销售额约73亿,低于新百伦的营业额。 3.产品简介 鞋款系列 (1)美国鞋 美国原厂制造,结合各种顶尖技术和完美材质,成为尊贵地位的象征,是许多政治领袖和成功企业家的最爱。 (2)功能性跑鞋 New Balance慢跑鞋针对各消费阶层的需要,推出方向控制、稳定避震、避震和轻量四大系列,为消费者提供绝佳的避震和稳定功能,以满足每位跑者的需要。(3)竞赛鞋 New Balance一直是竞赛跑鞋的领导品牌,提供吸震、避震、稳定且轻量的竞赛鞋,适合不同距离竞赛穿着,是竞赛跑者的最佳选择。 (4)越野跑鞋

高通量测序 名词解释

高通量测序基础知识汇总 一代测序技术:即传统的Sanger测序法,Sanger法是根据核苷酸在待定序列模板上的引物点开始,随机在某一个特定的碱基处终止,并且在每个碱基后面进行荧光标记,产生以A、T、C、G结束的四组不同长度的一系列核苷酸,每一次序列测定由一套四个单独的反应构成,每个反应含有所有四种脱氧核苷酸三磷酸(dNTP),并混入限量的一种不同的双脱氧核苷三磷酸(ddNTP)。由于ddNTP缺乏延伸所需要的3-OH 基团,使延长的寡聚核苷酸选择性地在G、A、T或C处终止,使反应得到一组长几百至几千碱基的链终止产物。它们具有共同的起始点,但终止在不同的的核苷酸上,可通过高分辨率变性凝胶电泳分离大小不同的片段,通过检测得到DNA碱基序列。 二代测序技术:next generation sequencing(NGS)又称为高通量测序技术,与传统测序相比,二代测序技术可以一次对几十万到几百万条核酸分子同时进行序列测定,从而使得对一个物种的转录组和基因组进行细致全貌的分析成为可能,所以又被称为深度测序(Deep sequencing)。NGS主要的平台有Roche(454 & 454+),Illumina(HiSeq 2000/2500、GA IIx、MiSeq),ABI SOLiD等。 基因:Gene,是遗传的物质基础,是DNA或RNA分子上具有遗传信息的特定核苷酸序列。基因通过复制把遗传信息传递给下一代,使后代出现与亲代相似的性状。 DNA:Deoxyribonucleic acid,脱氧核糖核酸,一个脱氧核苷酸分子由三部分组成:含氮碱基、脱氧核糖、磷酸。脱氧核糖核酸通过3',5'-磷酸二酯键按一定的顺序彼此相连构成长链,即DNA链,DNA链上特定的核苷酸序列包含有生物的遗传信息,是绝大部分生物遗传信息的载体。

高通量测序基础知识

高通量测序基础知识简介 陆桂 什么是高通量测序? 高通量测序技术(High-throughput sequencing,HTS)是对传统Sanger测序(称为一代测序技术)革命性的改变,一次对几十万到几百万条核酸分子进行序列测定, 因此在有些文献中称其为下一代测序技术(next generation sequencing,NGS )足见其划时代的改变, 同时高通量测序使得对一个物种的转录组和基因组进行细致全貌的分析成为可能, 所以又被称为深度测序(Deep sequencing)。 什么是Sanger法测序(一代测序) Sanger法测序利用一种DNA聚合酶来延伸结合在待定序列模板上的引物。直到掺入一种链终止核苷酸为止。每一次序列测定由一套四个单独的反应构成,每个反应含有所有四种脱氧核苷酸三磷酸(dNTP),并混入限量的一种不同的双脱氧核苷三磷酸(ddNTP)。由于ddNTP缺乏延伸所需要的3-OH基团,使延长的寡聚核苷酸选择性地在G、A、T或C处终止。终止点由反应中相应的双脱氧而定。每一种dNTPs和ddNTPs的相对浓度可以调整,使反应得到一组长几百至几千碱基的链终止产物。它们具有共同的起始点,但终止在不同的的核苷酸上,可通过高分辨率变性凝胶电泳分离大小不同的片段,凝胶处理后可用X-光胶片放射自显影或非同位素标记进行检测。 什么是基因组重测序(Genome Re-sequencing) 全基因组重测序是对基因组序列已知的个体进行基因组测序,并在个体或群体水平上进行差异性分析的方法。随着基因组测序成本的不断降低,人类疾病的致病突变研究由外显子区域扩大到全基因组范围。通过构建不同长度的插入片段文库和短序列、双末端测序相结合的策略进行高通量测序,实现在全基因组水平上检测疾病关联的常见、低频、甚至是罕见的突变位点,以及结构变异等,具有重大的科研和产业价值。 什么是de novo测序 de novo测序也称为从头测序:其不需要任何现有的序列资料就可以对某个物种进行测序,利用生物信息学分析手段对序列进行拼接,组装,从而获得该物种的基因组图谱。获得一个物种的全基因组序列是加快对此物种了解的重要捷径。随着新一代测序技术的飞速发展,基因组测序所需的成本和时间较传统技术都大大降低,大规模基因组测序渐入佳境,基因组学研究也迎来新的发展契机和革命性突破。利用新一代高通量、高效率测序技术以及强大的生物信息分析能力,可以高效、低成本地测定并分析所有生物的基因组序列。 什么是外显子测序(whole exon sequencing) 外显子组测序是指利用序列捕获技术将全基因组外显子区域DNA捕捉并富集后进行高通量测序的基因组分析方法。外显子测序相对于基因组重测序成本较低,对研究已知基因的SNP、Indel等具有较大的优势,但无法研究基因组结构变异如染色体断裂重组等。

量化研究与统计分析

1 第一讲量化研究与统计分析 1-1、量化研究的基本概念 1-2、量表分析步骤 1-3、量表的编码 1-4、复选题及其它方式的数据建文件

1-1、量化研究的基本概念 一、概述 社会科学领域研究的二个主要范畴: 1、量的资料(quantitative data)分析 2、质的研究(qualitative research)。 量的数据分析,受到信息科学进步的影响,数据的处理更为简易也较为客观,因而社会科学中多数研究论文仍倾向于量的研究。 量的研究主要采取逻辑实证主义的论点,重视变量间因果关系或变量间的相关,重视的是假设演绎取向法,强调受试取样的代表性,以使研究结果能有效推论到样本的母群体。 二、量化研究的方法 (一)、量化研究的统计方法 1.描述统计学(descriptive statistics) 2.推论统计学(inferential statistics) 目的:为了解整个研究母群体的特性。在社会科学领域中,由于母群体数目大多过于庞大,在时间、人力、物力、财力等考虑上,无法全部抽取母群体作为统计分析的对象,因而只能以随机或其它抽样的方式,抽取母群体中具代表性的样本作为研究分析的对象,再根据样本统计分析结果,推论到整个母群的性质。如:研究新课标施行后,我国中学生的学习情况,只能以部分学生的学习情况去推断全国学生的学习情况。 缺点:在推论统计学中,由于是根据样本特性再推论到整个母群属性,因而可能包含取样误差与推论误差存在,也就是此研究推论会有可能犯错的机率(probability)。

(二)、量化研究的设计方法: 1.调查法:分访问调查及问卷调查法; 2.实验法:分真正实验设计与准实验设计法; 量化研究的主要特征,皆要经由观察、测验、量表、问卷以取得研究实施的数据资料,作为假设验证的基础,因而如何搜集有效度的资料,如何配合研究目的与研究架构,选用合适的统计方法,以作为支持或否定原假设的证据资料,就显得格外重要。 (三)、量化研究的步骤:选题—设计问卷、调查—分析数据—给出结论1.选择与定义问题 研究问题必须是可以检验的假设,或研究者领域所感兴趣、有价值或重要性的问题,问题可以经过资料搜集、分析来加以检验或回答。量化研究问题可能是研究者感兴趣的主题;或有价值性的问题;或研究者认为是社会科学领域中重要的问题,此部份可以由相关文献的研究分析,挖掘相关研究的主题。制定研究主题后,要拟定研究架构,草拟研究问题及要检验的研究假设,并对重要的关键词,给予完整的概念性定义及操作型定义。 2.执行研究的程序 完整的实施程序包括样本或受试者的选择,测量工具的改进,数据的搜集。执行研究的程序就是决定抽样的方式,预试及正式问卷各抽取多少受试者,发展、编制或修订研究的测量工具,研究工具是否要先经专家效度检验? 3.资料分析 资料分析通常包括一个以上统计技巧的应用。数据分析的结果可提供研究者检验研究假设或回答研究问题。数据分析要根据检验的研究假设及变量性质,选用合适而正确的统计方法,包括预试问卷的信效度

(完整版)测序常用名词解释整理

高通量测序领域常用名词解释大全 什么是高通量测序? 高通量测序技术(High-throughput sequencing,HTS)是对传统Sanger测序(称为一代测序技术)革命性的改变, 一次对几十万到几百万条核酸分子进行序列测定, 因此在有些文献中称其为下一代测序技术(next generation sequencing,NGS )足见其划时代的改变, 同时高通量测序使得对一个物种的转录组和基因组进行细致全貌的分析成为可能, 所以又被称为深度测序(Deep sequencing)。 什么是Sanger法测序(一代测序) Sanger法测序利用一种DNA聚合酶来延伸结合在待定序列模板上的引物。直到掺入一种链终止核苷酸为止。每一次序列测定由一套四个单独的反应构成,每个反应含有所有四种脱氧核苷酸三磷酸(dNTP),并混入限量的一种不同的双脱氧核苷三磷酸(ddNTP)。由于ddNTP缺乏延伸所需要的3-OH基团,使延长的寡聚核苷酸选择性地在G、A、T或C处终止。终止点由反应中相应的双脱氧而定。每一种dNTPs和ddNTPs的相对浓度可以调整,使反应得到一组长几百至几千碱基的链终止产物。它们具有共同的起始点,但终止在不同的的核苷酸上,可通过高分辨率变性凝胶电泳分离大小不同的片段,凝胶处理后可用X-光胶片放射自显影或非同位素标记进行检测。

什么是基因组重测序(Genome Re-sequencing) 全基因组重测序是对基因组序列已知的个体进行基因组测序,并在个体或群体水平上进行差异性分析的方法。随着基因组测序成本的不断降低,人类疾病的致病突变研究由外显子区域扩大到全基因组范围。通过构建不同长度的插入片段文库和短序列、双末端测序相结合的策略进行高通量测序,实现在全基因组水平上检测疾病关联的常见、低频、甚至是罕见的突变位点,以及结构变异等,具有重大的科研和产业价值。 什么是de novo测序 de novo测序也称为从头测序:其不需要任何现有的序列资料就可以对某个物种进行测序,利用生物信息学分析手段对序列进行拼接,组装,从而获得该物种的基因组图谱。获得一个物种的全基因组序列是加快对此物种了解的重要捷径。随着新一代测序技术的飞速发展,基因组测序所需的成本和时间较传统技术都大大降低,大规模基因组测序渐入佳境,基因组学研究也迎来新的发展契机和革命性突破。利用新一代高通量、高效率测序技术以及强大的生物信息分析能力,可以高效、低成本地测定并分析所有生物的基因组序列。

量化研究与质化研究(精编)

量化研究与质化研究 一、概念上的区别 1、量化研究:运用心理测量、心理实验、心理调查等方法获得数量化的研究资料,并运用数学、统计等方法对资料进行分析,以获得研究结论的方法。 2、质化研究:运用历史回顾、文献分析、访问、观察、参与经验等方法获得研究资料,并用非量化的方法,主要是个人的经验,对资料进行分析,以获得研究结论的方法。 二、研究目标:控制预测取向与意义理解取向 1、量化研究:着眼于代表一般性的群体,探求心理与行为的普遍模式和一般规律,从而对行为进行控制和预测。 2、质化研究:着眼于研究特殊的个体,旨在揭示个体独特心理和行为特征,从而描述和解释特定研究情境中人们的经验,理解社会以及人们日常生活的意义。 三、研究对象:客观实在取向和主观唯心取向 1、量化研究:(1)以实证主义作为其哲学基础,强调事物是客观存在于人类之外的、不依赖于人的主观意识而独立存在。(2)客观现象是可以被认识的,人们可以通过经验的方法感知客观世界,把握客观世界的规律。(3)因此,量化研究的对象是一些事实、变量和固定不变的客观事物,研究者通过经验的、数量化的方法发现研究对象运动变化的规律。研究者和研究对象是主体和客体的关系,彼此独立分离。 2、质化研究:以现象学、释义学、建构主义为哲学基础,认为社会科学不像自然科学那样客观化、理性化,社会学科的研究对象是人及人类的主观意识,带有主观性,事件伴随事件、地点而变化,因此,人们不能独立地认识现实,现实也不能被完全了解,都要受到社会、历史、经济、文化等因素的影响和制约。研究者和研究对象之间是主题与主题的关系,彼此影响,密切联系。 四:研究方法:经验证实取向与解释建构取向 1、量化研究:(1)量化研究预先假定一个独立的实在,再用实验、测量等方法进行验证,借助于可靠的数据,从外部观察者的立场来观察研究社会生活实践,是一个演绎推理的过程。(2)具体方法上,量化研究是按照统计学的原则随机取样,抽取出代表一般性的普通样本。在数据收集方面,一般用观察法、量表法、问卷法和实验法来搜集数据,这些方法在实施之前都已经设计好,不允许随意改动。实验过程中有严格的控制。数据分析通过专门的分析手段,如统计学方法、计算机软件等,研究者可以利用他们解释数据并预测因果或相关关系。 2、质化研究:(1)质化研究的前提是研究者根据自己已有的知识、兴趣、主观价值判断来选择研究问题,研究者进入被研究者的立场,描述、分析人类社会中的文化和行为,研究者认为自身就是研究内容的一部分,强调观察到的世界是由研究者构建出来的,承认自己在知识建构中的核心地位。(2)具体方法上,质化研究多采用目的性取样,抽取出典型的样本;数据搜集方面,质化研究者根据自身丰富的经验和直觉判断决定如何对被试样本进行访谈和调查,并借助于文献、实物寻找出所要研究问题的相关材料。在数据解释方面,质化研究者依赖研究者个人的主观认知建构,包括直觉和推理,用日常语言进行描述,不受任何外在标准的束缚。 五、关系 1、二者实际上是相辅相成,互相促进的。最终目标都是为了解释、预测和控制。 2、研究过程中,质化研究也会采用一些数量化的手段,借助数据来进行判断、推理,形成结论。量化研究的假设部分和研究结论部分一般也是质化性质的,离不开质化的研究思维和方法。

全基因组从头测序(de novo测序)

全基因组从头测序(de novo测序) https://www.360docs.net/doc/5e15252243.html,/view/351686f19e3143323968936a.html 从头测序即de novo 测序,不需要任何参考序列资料即可对某个物种进行测序,用生物信息学分析方法进行拼接、组装,从而获得该物种的基因组序列图谱。利用全基因组从头测序技术,可以获得动物、植物、细菌、真菌的全基因组序列,从而推进该物种的研究。一个物种基因组序列图谱的完成,意味着这个物种学科和产业的新开端!这也将带动这个物种下游一系列研究的开展。全基因组序列图谱完成后,可以构建该物种的基因组数据库,为该物种的后基因组学研究搭建一个高效的平台;为后续的基因挖掘、功能验证提供DNA序列信息。华大科技利用新一代高通量测序技术,可以高效、低成本地完成所有物种的基因组序列图谱。包括研究内容、案例、技术流程、技术参数等,摘自深圳华大科技网站 https://www.360docs.net/doc/5e15252243.html,/service-solutions/ngs/genomics/de-novo-sequencing/ 技术优势: 高通量测序:效率高,成本低;高深度测序:准确率高;全球领先的基因组组装软件:采用华大基因研究院自主研发的SOAPdenovo软件;经验丰富:华大科技已经成功完成上百个物种的全基因组从头测序。 研究内容: 基因组组装■K-mer分析以及基因组大小估计;■基因组杂合模拟(出现杂合时使用); ■初步组装;■GC-Depth分布分析;■测序深 度分析。基因组注释■Repeat注释; ■基因预测;■基因功能注释;■ ncRNA 注释。动植物进化分析■基因家族鉴定(动物TreeFam;植物OrthoMCL);■物种系统发育树构建; ■物种分歧时间估算(需要标定时间信息);■基因组共线性分析; ■全基因组复制分析(动物WGAC;植物WGD)。微生物高级分析 ■基因组圈图;■共线性分析;■基因家族分析; ■CRISPR预测;■基因岛预测(毒力岛); ■前噬菌体预测;■分泌蛋白预测。 熊猫基因组图谱Nature. 2010.463:311-317. 案例描述 大熊猫有21对染色体,基因组大小2.4 Gb,重复序列含量36%,基因2万多个。熊猫基因组图谱是世界上第一个完全采用新一代测序技术完成的基因组图谱,样品取自北京奥运会吉祥物大熊猫“晶晶”。部分研究成果测序分析结果表明,大熊猫不喜欢吃肉主要是因为T1R1基因失活,无法感觉到肉的鲜味。大熊猫基因组仍然具备很高的杂合率,从而推断具有较高的遗传多态性,不会濒于灭绝。研究人员全面掌握了大熊猫的基因资源,对其在分子水平上的保护具有重要意义。 黄瓜基因组图谱黄三文, 李瑞强, 王俊等. Nature Genetics. 2009. 案例描述国际黄瓜基因组计划是由中国农业科学院蔬菜花卉研究所于2007年初发起并组织,并由深圳华大基因研究院承担基因组测序和组装等技术工作。部分研究成果黄瓜基因组是世界上第一个蔬菜作物的基因组图谱。该项目首次将传

量化研究之名词释义

量化研究之名詞釋義 撰寫研究計畫或研究報告時,須將有關的名詞作明確的界定,此類名詞,限於研究問題(problem)中出現的為限。研究者對於名詞定義(definition of terms),皆不逾現有的用法與知識為度,一方面能使這些名詞, 一、非研究變項之名詞釋義 (一)研究對象 研究對象之「名詞釋義」,大都直接就研究本身之「研究對象」予以定義。例如: 音樂資優生 本研究所稱之音樂資優生,係指通過甄試,就讀於國小、國中及高中音樂班 的學生。 資料來源:楊如馨(2000)。音樂資優學生之父母管教方式、A型性格、認知風格與音樂表演焦慮之關係。國立臺南師範學院國民教育研究所碩士論文。 (二)研究範圍 研究範圍之「名詞釋義」,大都直接就研究本身之「研究範圍」予以定義。例如: 高級工業職業學校(vocational industrial high school) 狹義的高級工業職業學校係指一所高級職業學校僅僅設有工業類科之單一 職類的高級工業職業學校,而廣義的高級工業職業學校應該包括僅設工業類 科之高級工業職業學校、或併設工業類科之工商、工農、工家等雙職類之高 級職業學校、以及附設工業類科之高級中學和綜合高中。本研究所稱之高級 工業職業學校係指我國教育體制下之公私立高級工業職業學校、以及工業類 科班級數比例在二分之一以上之工農、農工、工商、商工、工家職業學校與 高級中等學校。 資料來源:張瑞村(1998)。高級工業職業學校校長領導行為、教師組織承諾與學校效能關係之研究。 國立政治大學教育研究所博論文。

二、研究變項之名詞釋義 研究變項之名詞釋義宜包括「概念性定義」(conceptual definition)與「操作性定義」(operational definition)。 例如: 父母管教方式 父母管教方式係指父母親所採用之管教子女生活作息與行為表現的策略(王 鍾和,民84)。本研究之父母管教方式指的乃是父母對其子女的期望與平日 管教子女所採用的態度與方法。父母期望是指為人父母者對其子女的行為表 現與未來成就發展所寄予的期望(張世平,民72)。本研究係以受試者在研 究者自編的「父母管教方式量表」三個分量表:(1)期望與鼓勵;(2)要求 與責備;(3)規定與限制中所得之分數,作為評量的指標。 上述「父母管教方式」之名詞釋義,可以分為二部分,前半段為「概念性定義」,即: 父母管教方式係指父母親所採用之管教子女生活作息與行為表現的策略(王 鍾和,民84)。本研究之父母管教方式指的乃是父母對其子女的期望與平日 管教子女所採用的態度與方法。父母期望是指為人父母者對其子女的行為表 現與未來成就發展所寄予的期望(張世平,民72)。 後半段則為「操作性定義」,即: 本研究係以受試者在研究者自編的「父母管教方式量表」三個分量表:(1) 期望與鼓勵;(2)要求與責備;(3)規定與限制中所得之分數,作為評量的 指標。 資料來源:楊如馨(2000)。音樂資優學生之父母管教方式、A型性格、認知風格與音樂表演焦慮之關係。國立臺南師範學院國民教育研究所碩士論文。

农作物重要品种全基因组de novo测序

首页 科技服务 医学检测 科学与技术 市场与支持 加入我们 关于我们 提供领先的基因组学解决方案Providing Advanced Genomic Solutions 参考文献 [ 1 ] Li Y, Zhou G, Jiang W, et al. De novo assembly of soybean wild relatives for pan-genome analysis of diversity and agronomic traits[J]. Nature biotechnology, 2014, 32(10): 1045-1052. [ 2 ] Da Silva C, Zamperin G, et al. The high polyphenol content of grapevine cultivar tannat berries is conferred primarily by genes that are not shared with the reference genome. Plant Cell, 2013, 25(12):4777-88. [ 3 ] Qi XP, Li M, et al. Identification of a novel salt tolerance gene in wild soybean by whole-genome sequencing. Nature Communica- tions, 2014(5). 挖掘特异基因 解析特有性状 重要品种 全基因组 de novo 所研究品种 小片段文库大片段文库 HiSeq测序(>100X) 基因组组装 注释 全基因组序列比对 转录组遗传图谱等辅助验证 重要农艺性状解析 基因家族聚类分析 所研究品种基因组序列 已发表品种 基因组序列 已发表品种基因集合 所研究品种基因集合 变异检测 小的插入 缺失 SNP 倒位 易位大的插入 缺失 基因挖掘 新基因鉴定拷贝数扩增基因基因丢失正选择基因鉴定 物种 品种 发表杂志(年份) 物种 品种发表杂志(年份) 大豆 棉花 番茄 土豆 水稻 葡萄猪栽培大豆7种野生大豆 野生耐盐大豆雷德氏棉 亚洲棉 陆地棉栽培番茄 抗病番茄栽培土豆 耐寒土豆 Nature (2010) Nature Biotechnology (2014) Nature Communications (2014) Nature (2012)Nature Genetics (2014)Nature Biotechnology (2015)Nature (2012) Nature Genetics (2014) Nature (2011) Plant Cell (2015) 栽培水稻(粳稻)栽培水稻(籼稻) 短花药野生稻 非洲栽培稻五种野生稻三种栽培稻葡萄 丹娜葡萄杜洛克猪藏猪 Science (2002)Science (2002) 野生大豆泛基因组 阅读原文>> 诺禾致源的项目经验 诺禾致源在动植物全基因组测序领域一直处于领先地位, 以第一通讯作者发表基因组文章5篇(影响因子累计152.474),其中2篇为杂志封面文章。 近年来,诺禾通过自主研发软件与技术革新,成功地将项目周期压缩至14个月内,费用降低一半以上。 特有基因检测 对7株代表性野生大豆品种进行全基因组de novo 测序及比较基因组分析,发现每个大豆品种中有1,000~3,000个品种特有的基因。 高变区变异检测 在传统测序方法中,将研究物种短reads 比对参考基因组无法检测到变异位点;在全基因组de novo 方法中,将组装后的超长序列比对参考基因组可准确识别高变区域内的所有变异位点。性状解析方案设计 通过对重要品种高深度(>100X)测序,并进行基因组组装注释: 找到传统测序无法鉴定的高度变异位点,找到更多更准确的SNP位点;找到参考基因组中 所不存在的基因——品种特有基因。 2. 耐盐大豆耐盐基因的发现 2014年,研究人员对一株耐盐大豆开展了全基因组de novo 测序,并与栽培大豆基因组进行全基因组比对,通过一条跨过长达388 Kb 的重要功能区的scaffold,发现了巨大的结构变异,从而成功鉴定出耐盐基因。该基因在栽培大豆中被插入了一个长达3.4 Kb 的反转座子,影响了阳离子转运体功能,从而使栽培大豆失去了耐盐能力。 传统的测序手段,采用的是短reads 比对,因而对这类大的结构变异检测精度差、灵敏度低、甚至难以实现检测,而全基因组de novo 测序则能很好的克服该问题。阅读原文>> 案例分享 1. 丹娜葡萄全基因组测序揭示高丹宁含量性状的分子机制 丹娜葡萄被认为是丹宁含量最高的葡萄品种之一,由于富含丹宁等抗氧化分子,被认为有延缓衰老的作用。通过对其基因组测序,研究人员发现与丹宁合成有关的关键酶,几乎都能找到新的基因。很显然,只依赖已有的参考基因组,完全无法了解丹娜葡萄高丹宁含量这一性状的遗传基础,而全基因组de novo 测序则完美回答了该问题。阅读原文>> 重要品种基因组的价值 一些物种,虽然已有参考基因组,但仍然无法找到性状关联基因。 一方面,参考基因组与研究物种差异太大; 另一方面,性状相关基因处于基因组快速进化区域,变异极大,传统测序手段难以鉴定。 目前,de novo测序在有参品种重要性状探究方面的应用愈发广泛, 相关研究结果常见于国际顶级杂志上。