Insect herbivores drive real time ecological and evolutionary change in plant populaitons

19.B.Wilm,A.Ipenberg,N.D.Hastie,J.B.E.Burch,

D.M.Bader,Development 132,5317(2005).20.B.Zhou et al .,Nature 454,109(2008).

21.B.Lustig et al .,Mol.Cell.Biol.22,1184(2002).

22.S.Hayashi,A.P.McMahon,Dev.Biol.244,305(2002).23.Y.Ruzankina et al .,Cell Stem Cell 1,113(2007).24.N.Barker et al .,Nature 449,1003(2007).25.L.Topol et al .,J.Cell Biol.162,899(2003).26.A.J.Mikels,R.Nusse,PLoS Biol.4,e115(2006).

27.A.Sato,H.Yamamoto,H.Sakane,H.Koyama,A.Kikuchi,

EMBO J.29,41(2010).

28.T.Ishitani et al .,Mol.Cell.Biol.23,131(2003).29.G.J.Hannon,D.Beach,Nature 371,257(1994).

30.H.L.Moses,E.Y.Yang,J.A.Pietenpol,Cell 63,245(1990).31.S.Dennler et al .,EMBO J.17,3091(1998).

32.L.Grumolato et al .,Genes Dev.24,2517(2010).33.M.Yamada et al .,Dev.Dyn.239,941(2010).

34.A.Iavarone,J.Massagué,Nature 387,417(1997).35.N.R.Gough,Sci.Signal.1,eg8(2008).

36.T.P.Yamaguchi,A.Bradley,A.P.McMahon,S.Jones,

Development 126,1211(1999).

37.M.Ito et al .,Nature 447,316(2007).

Acknowledgments:We thank R.Kopan for comments on the manuscript,W.Pu for reagents,and R.Head and

C.Storer for the microarray analysis.This work was funded by the NIH (grant DK90251);the Pew Scholars Program in the Biomedical Sciences;grant 5T35DK074375(Trans-National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Short-Term Training for Medical Students);the Washington Univ.Digestive Disease Research Core (NIH grant P30-DK52574);and the Intramural Research Program of the NIH,National Cancer Institute,Center for Cancer Research.Microarray data are available on Array Express (accession no.E-MTAB-1175).

Materials transfer agreements will be required for the acquisition of the Wnt5a f/f mice from the National Cancer Institute and the L-WRN cell line from the Washington Univ.Medical School.The data presented in this manuscript are tabulated in the main paper and in the supplementary materials.

Supplementary Materials

https://www.360docs.net/doc/826732560.html,/cgi/content/full/science.1223821/DC1Materials and Methods Figs.S1to S14Tables S1to S3References (38–53)

25April 2012;accepted 21June 2012Published online 6September 2012;10.1126/science.1223821

Insect Herbivores Drive Real-Time Ecological and Evolutionary Change in Plant Populations

Anurag A.Agrawal,1,2*Amy P.Hastings,1Marc T.J.Johnson,3John L.Maron,4Juha-Pekka Salminen 5Insect herbivores are hypothesized to be major factors affecting the ecology and evolution of plants.We tested this prediction by suppressing insects in replicated field populations of a

native plant,Oenothera biennis ,which reduced seed predation,altered interspecific competitive dynamics,and resulted in rapid evolutionary https://www.360docs.net/doc/826732560.html,parative genotyping and phenotyping of nearly 12,000O.biennis individuals revealed that in plots protected from insects,resistance to herbivores declined through time owing to changes in flowering time and lower defensive ellagitannins in fruits,whereas plant competitive ability increased.This independent real-time evolution of plant resistance and competitive ability in the field resulted from the relaxation of direct selective effects of insects on plant defense and through indirect effects due to reduced herbivory on plant competitors.

T

he ubiquitous consumption of plants by insect herbivores represents one of the dominant species interactions on Earth and has been hypothesized to play a strong role in the diversification of plant species and their traits (1–3).The evolution of plant defense has been studied primarily with either a prospective or retrospective approach.Single-generation pro-spective approaches measure contemporary natural selection on resistance traits and make predictions about how those traits should evolve given esti-mates of their heritability (4–6).By contrast,ret-rospective studies compare populations or species that have diverged over time (7–9)and make in-ferences about the processes driving evolutionary change.More generally,temporal studies of natu-ral species interactions that influence evolutionary dynamics remain rare,and few have been exper-imental (9–12).Thus,we lack experimental field studies that quantify how species interactions in-fluence selection on traits and the evolutionary response to this selection.As such,it is not well

established how rapidly plants adapt to selection by herbivores,which traits are most important in the evolution of defense,and whether herbivory drives predictable parallel changes due to selec-tion across populations.

The ecology and evolution of plant-herbivore relationships is,in part,governed by the recipro-cal nature of their interaction and the complex-ity of communities.For example,plant traits and plant community structure are critical for determining insect occurrence and attack rates (1–3).Conversely,insects can directly reduce focal plant abundance (13)or indirectly affect plant abundance through changes in the density of co-occurring competitors (14).Thus,the evolution-ary dynamics of a focal plant species might be influenced through direct selection on resist-ance traits and/or by indirect selection on traits influencing competitive ability (15,16).Despite this likely scenario,our understanding of how species interactions influence the evolution of constituent community members is surprisingly limited (17).

We conducted a field study of the selective impact of insects and the evolutionary response

1

Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology,Cornell Uni-versity,Ithaca,NY 14853,USA.2Department of Entomol-ogy,Cornell University,Ithaca,NY 14853,USA.3Department of Biology,University of Toronto at Mississauga,Mississauga,ON L5L 1C6,Canada.4Division of Biological Sciences,University of Montana,Missoula,MT 59812,USA.5Laboratory of Organic Chemistry and Chemical Biology,Department of Chemistry,University of Turku,FI-20014Turku,Finland.

*To whom correspondence should be addressed.E-mail:

agrawal@https://www.360docs.net/doc/826732560.html,

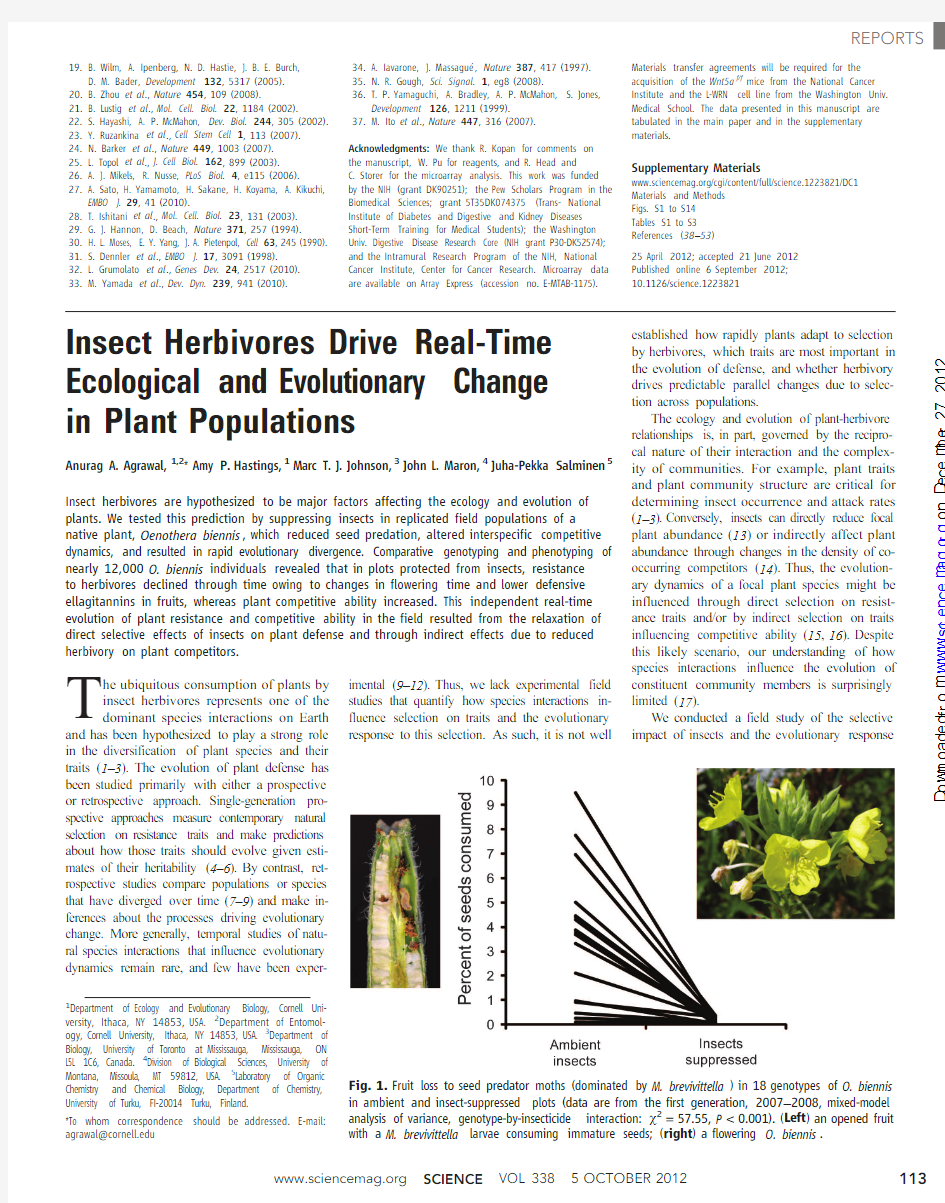

Fig.1.Fruit loss to seed predator moths (dominated by M.brevivittella )in 18genotypes of O.biennis in ambient and insect-suppressed plots (data are from the first generation,2007–2008,mixed-model analysis of variance,genotype-by-insecticide interaction:c 2=57.55,P <0.001).(Left )an opened fruit with a M.brevivittella larvae consuming immature seeds;(right )a flowering O.biennis .

o n D e c e m b e r 27, 2012

w w w .s c i e n c e m a g .o r g D o w n l o a d e d f r o m

to this selection in the native forb common evening primrose,Oenothera biennis(Onagraceae)(18). We established16replicate plots planted with 60individual seedlings of O.biennis,containing equivalent frequencies of18uniquely identi-fied genotypes(19).Half of the plots were treated biweekly during each growing season with esfenvalerate,a nonsystemic insecticide(insect suppression treatment,supplementary text2a); the remaining plots received an equivalent amount of water as a control(ambient insect treat-ment).Because O.biennis is annual or biennial, primarily selfing,and has a genetic system that suppresses recombination and segregation of al-leles,we could track changes in frequencies of each planted genotype within each replicate population over multiple generations(19).Plots were not fur-ther weeded or otherwise manipulated,allowing the natural assembly and early succession of plant species with and without insects(supplementary text2b).We previously summarized our sam-pling methods,the effects of flowering phenology on insect attack,and plant life-history evolution in the ambient insect plots(19).Here,we address the effects of experimental insect suppression on ecological and evolutionary change in O.biennis, including changes in genotypic composition,de-fensive chemistry,competitive ability,and flow-ering time.

Although there were three native species of specialist seed predator moths at our site,fruit loss in O.biennis was dominated by Mompha

brevivittella,which was>5times as abundant as

M.stellella and Schinia florida combined,the

other two common specialists.The18O.biennis

genotypes varied substantially in their resistance

to these seed predators(Fig.1),and insect sup-

pression created an environment with potential-

ly large differences in natural selection.Despite

increases in O.biennis abundance in the first

2years of the experiment(reaching up to4000

individuals per plot in2009),recruitment was

substantially lower in the insect suppression

plots compared to ambient controls(Fig.2).This

reduction in O.biennis density coincided with

a rise in the abundance of common dandelion,

Taraxacum officinale(Asteraceae),an early suc-

cessional weed that dominated our plots and

was twice as abundant in plots where insects

were suppressed compared to controls(Fig.2

and fig.S1).

A specialist seed-feeding beetle of T.officinale,

Glocianus punctiger,was significantly reduced by

insect suppression,and a highly abundant gener-

alist moth caterpillar at the site,Noctua pronuba,

showed a preference for T.officinale over O.biennis

(supplementary text2c).Thus,we hypothesized

that the release of T.officinale from its herbivores

led to competitive suppression of O.biennis.In-

deed,populations of O.biennis and T.officinale

showed a negative correlation at the population

level(simple correlation,N=16,r=–0.523,P=

0.038),and an independent field experiment at

the same site confirmed that T.officinale inhibits

early establishment of O.biennis(supplementary

text2d).Because O.biennis requires light for ger-

mination,we hypothesize that T.officinale likely

affects germination as well as early seedling sur-

vival.Therefore,insect suppression substantially

affected plant competitors in addition to our focal

species.

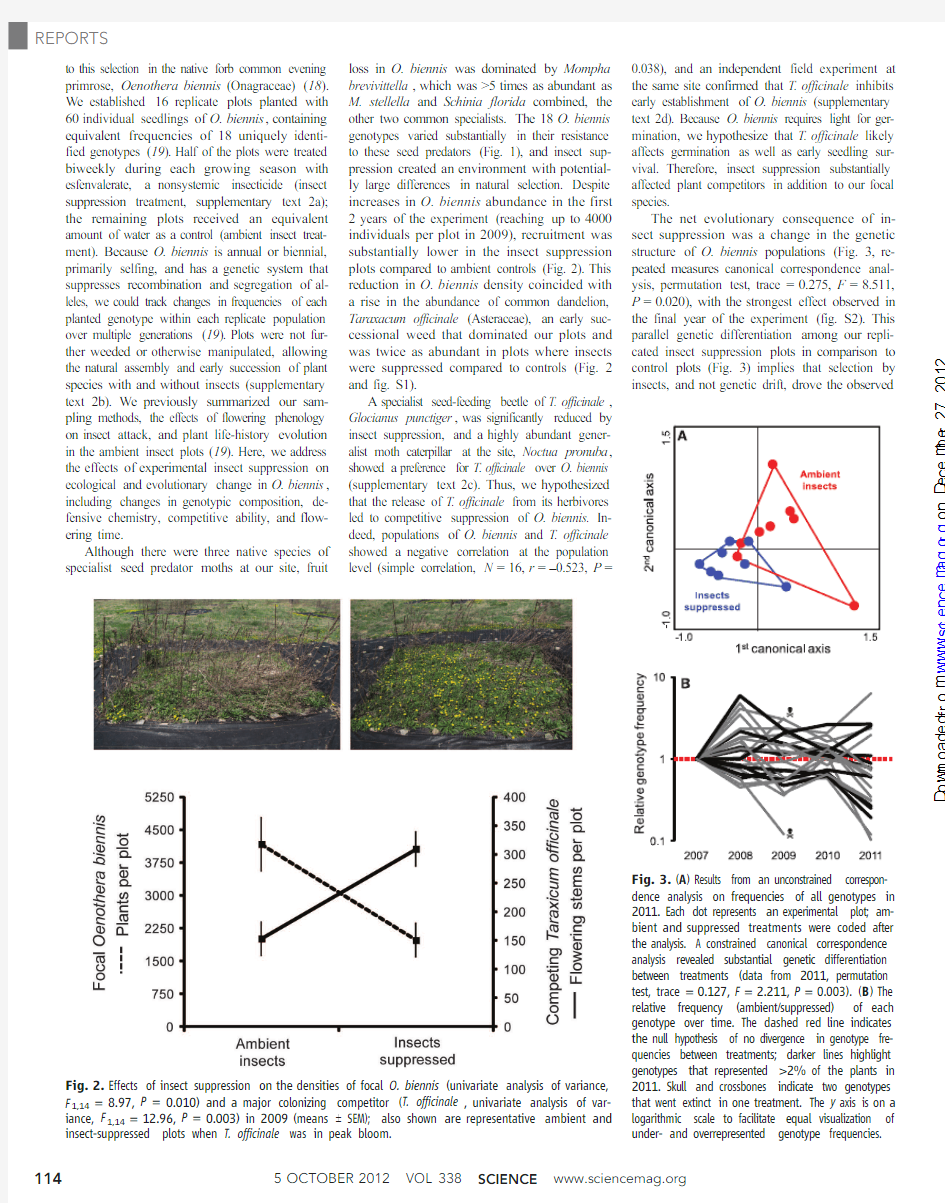

The net evolutionary consequence of in-

sect suppression was a change in the genetic

structure of O.biennis populations(Fig.3,re-

peated measures canonical correspondence anal-

ysis,permutation test,trace=0.275,F=8.511,

P=0.020),with the strongest effect observed in

the final year of the experiment(fig.S2).This

parallel genetic differentiation among our repli-

cated insect suppression plots in comparison to

control plots(Fig.3)implies that selection by

insects,and not genetic drift,drove the

observed

Fig.2.Effects of insect suppression on the densities of focal O.biennis(univariate analysis of variance,

F1,14=8.97,P=0.010)and a major colonizing competitor(T.officinale,univariate analysis of var-

iance,F1,14=12.96,P=0.003)in2009(means T SEM);also shown are representative ambient and

insect-suppressed plots when T.officinale was in peak

bloom.

Fig.3.(A)Results from an unconstrained correspon-

dence analysis on frequencies of all genotypes in

2011.Each dot represents an experimental plot;am-

bient and suppressed treatments were coded after

the analysis.A constrained canonical correspondence

analysis revealed substantial genetic differentiation

between treatments(data from2011,permutation

test,trace=0.127,F=2.211,P=0.003).(B)The

relative frequency(ambient/suppressed)of each

genotype over time.The dashed red line indicates

the null hypothesis of no divergence in genotype fre-

quencies between treatments;darker lines highlight

genotypes that represented>2%of the plants in

2011.Skull and crossbones indicate two genotypes

that went extinct in one treatment.The y axis is on a

logarithmic scale to facilitate equal visualization of

under-and overrepresented genotype frequencies.

o

n

D

e

c

e

m

b

e

r

2

7

,

2

1

2

w

w

w

.

s

c

i

e

n

c

e

m

a

g

.

o

r

g

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

genotypic evolution.At the end of the experi-ment,1of the original18genotypes was entire-ly extirpated,and two additional genotypes were represented only in insect suppression plots(Fig.

3).Only six genotypes consistently maintained a frequency of2%or higher within the popula-tions.Three novel genotypes,derived from out-crossing events between known parents,each also reached>2%of the populations in2011(sup-plementary text2e).Thus,across both treatments, nine genotypes dominated all plots(>2%each) at the end of the experiment.Genotypic even-ness was>50%higher in insect suppression plots compared to controls(Smith and Wilson’s even-ness index,E var,univariate analysis of variance, F1,14=15.037,P=0.002),suggesting an erosion of genotypic variance in the presence of insect herbivores.Nonetheless,insect suppression af-fected neither genotypic richness(univariate anal-ysis of variance,F1,14=0.287,P=0.600)nor diversity(Simpson’s index,univariate analysis of variance,F1,14=0.377,P=0.549).

On the basis of annual estimates of genotype frequencies in each plot and genotype-specific means of M.brevivittella attack measured in control plots during2007,we found that experi-mental suppression of insects resulted in evolu-tion of relaxed plant defense(Fig.4).We next determined the evolutionary response of traits re-sponsible for this divergence in resistance.We had previously shown that the extent of early-season flowering(number of open or senesced flowers after50%of the plants had at least a

single open flower)positively correlated with

M.brevivittella attack in2years(19)(i.e.,later-

flowering plants suffered less damage).There

was no difference between treatments in the first

year of our study(2007),as early season flower-

ing was not different among the two treatments

(univariate analysis of variance,F1,14=0.320,

P=0.581);by2010,there was a significant shift

toward earlier flowering in plots with suppressed

insects(univariate analysis of variance,F1,14=

6.105,P=0.027).This effect was even stronger

in2011(Fig.4,univariate analysis of variance,

F1,14=7.025,P=0.019)and was predictable on

the basis of genotype frequencies and genotype-

specific means for early flowering(Fig.4).Thus,

a predicted response to selection was evident in

only three to four generations.We found no dif-

ference in annual versus biennial phenotypes of

O.biennis(repeated measures multivariate anal-

ysis of variance,F1,14=0.935,P=0.350).

O.biennis produces diverse hydrolyzable tan-

nins,including the largest ellagitannins known

from any plant species(20),and these com-

pounds have very high oxidative capacity,nega-

tively affecting insect herbivores(21).One trimer,

oenothein A(fig.S3),was the dominant ellagitan-

nin in O.biennis fruits(up to7.8%dry mass).We

previously showed that oenothein A is favored

by natural selection in O.biennis leaves(6),and

its production in fruits was negatively geneti-

cally correlated with M.brevivittella attack in

the current study(simple correlation,N=17,r=

–0.491,P=0.045)(supplementary text2f),im-

plicating a role of this compound in defense.

Despite a genetic correlation between foliar and

fruit ellagitannin chemistry(simple correlation,

N=18,r=0.848,P<0.001),only fruit chem-

istry significantly diverged in our experimental

plots(Fig.4),suggesting that selection was stron-

gest for defense against flower-and fruit-feeding

herbivores like M.brevivittella.A negative genetic

correlation between early-season flowering and

the production of oenothein A in fruits(simple

correlation,N=23,r=–0.67,P<0.001)is con-

sistent with the rapid and joint evolution of these

traits(i.e.,early flowering with low oenothein A

in insect-suppressed plots)(Fig.4).

Given that insect suppression not only affected

herbivory on O.biennis,but also resulted in stron-

ger plant competition through larger T.officinale

populations,we hypothesized that O.biennis

would evolve greater competitive ability in the

absence of insects.We measured the relative com-

petition index(RCI)in total above-and below-

ground biomass of different genotypes in an

independent experiment(fig.S4).We then used

these genotype-specific values of competitive

ability to determine if the competitive phenotypes

diverged between control and insect-suppressed

plots.Insect suppression resulted in the evolution

of enhanced competitive ability relative to am-

bient insect plots(Fig.4),and because this effect

was not genetically correlated with

early-season

Fig.4.Phenotypic evolution in O.biennis plots.(A)In the presence of seed

predator insects,higher plant resistance evolved[estimated by multiplying

genotype-specific means measured in control(ambient insect)plots by genotype

frequencies in each plot](repeated measures multivariate analysis of variance,

F1,14=6.322,P=0.025),and this effect did not vary over time(time-by-

treatment interaction,repeated measures multivariate analysis of variance,

F3,12=1.459,P=0.275).(B)Earlier flowering was observed in the insect

suppression plots(univariate analysis of variance,F1,14=7.025,P=0.019).

We confirmed that this was an evolutionary response by multiplying genotype-

specific means by genotype frequencies(univariate analysis of variance,F1,14=

4.530,P=0.050);the former field assessment includes the possible effects of

phenotypic plasticity,whereas the latter is based on genotypic values.(C)Leaf

defensive chemistry did not diverge(univariate analysis of variance,F1,14=

1.716,P=0.211)but fruit chemistry changed(univariate analysis of variance,

F1,14=8.917,P=0.010)as predicted by genotypic means and genotype

frequencies.(D)Competitive ability of O.biennis when grown with T.officinale;

plants in the insect-suppressed plots evolved a greater ability to maintain above-

and belowground biomass(relative competition index)when grown with a com-

petitor than when grown alone(repeated measures multivariate analysis of

variance,F1,14=5.189,P=0.038);this effect did not vary over time(repeated

measures multivariate analysis of variance,time-by-treatment interaction(F3,12=

0.072,P=0.974).All panels show means T SEM;ns,not significant.

o

n

D

e

c

e

m

b

e

r

2

7

,

2

1

2

w

w

w

.

s

c

i

e

n

c

e

m

a

g

.

o

r

g

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

flowering(simple correlation,N=23,r=–0.157, P=0.474),the production of oenothein A(sim-ple correlation,N=23,r=0.035,P=0.871), or resistance to M.brevivittella(simple correla-tion,N=17,r=–0.255,P=0.241),responses to natural selection were unconstrained by genet-ic correlations.The evolution of increased suscep-tibility to herbivores and enhanced competitive ability was jointly favored by the suppression of insects.

Concurrent evolution of herbivore resistance and competitive ability was only partially predict-able from annual measures of natural selection. We correlated trait values against lifetime seed production in each year,hypothesizing that we would observe divergent slopes concordant with the divergent evolutionary change that we ob-served between our two treatments.Although we found significantly divergent natural selection between ambient and insect suppression plots for the two resistance traits,this effect was ob-served in only1of4years(fig.S5).Nonetheless, when differences in natural selection were ob-served,they were in the predicted direction on the basis of the observed evolutionary change (table S1).Thus,annual measures of natural selec-tion predicted from fecundity were not strong predictors of evolutionary change,which suggests that selection on other components of fitness con-tribute to observed evolutionary responses(19).

Our study provides definitive evidence for the rapid evolution of insect-mediated plant resist-ance traits in real time,supporting current interest in reciprocal feedbacks between evolutionary change and ecological dynamics(17,19,22,23). We highlight how biotic environmental factors simultaneously alter ecological and evolutionary dynamics.Specifically,our finding that multiple herbivores attacking co-occurring host plants can

alter competitive interactions is likely quite gen-

eral in natural ecosystems(14,24,25),and the

rapid evolutionary responses observed confirm

predicted interactive effects of herbivory and com-

petition on plant evolution(15,16).Given that

O.biennis is a poor competitor,we predict that

evolutionary shifts in resistance and competitive

ability allow this species to persist for longer pe-

riods of time during succession.

References and Notes

1.P.R.Ehrlich,P.H.Raven,Evolution18,586(1964).

2.G.S.Fraenkel,Science129,1466(1959).

3.D.J.Futuyma,A.A.Agrawal,Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A.

106,18054(2009).

4.J.Fornoni,P.L.Valverde,J.Nú?ez-Farfán,Evolution58,

1696(2004).

5.R.Mauricio,M.D.Rausher,Evolution51,1435(1997).

6.M.T.J.Johnson,A.A.Agrawal,J.L.Maron,J.P.Salminen,

J.Evol.Biol.22,1295(2009).

7.R.F.Bode,A.Kessler,J.Ecol.100,795(2012).

8.G.A.Desurmont,M.J.Donoghue,W.L.Clement,

A.A.Agrawal,Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A.108,7070

(2011).

9.A.R.Zangerl,M.R.Berenbaum,Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A.

102,15529(2005).

10.P.H.Thrall,J.J.Burdon,Science299,1735(2003).

11.P.R.Grant,B.R.Grant,Science296,707(2002).

12.D.A.Reznick,H.Bryga,J.A.Endler,Nature346,357

(1990).

13.J.L.Maron,E.Crone,Proc.Biol.Sci.273,2575(2006).

14.W.P.Carson,R.B.Root,Ecol.Monogr.70,73

(2000).

15.A.A.Agrawal,https://www.360docs.net/doc/826732560.html,u,P.A.Hamb?ck,Q.Rev.Biol.81,

349(2006).

16.M.Uriarte,C.D.Canham,R.B.Root,Ecology83,2649

(2002).

17.T.W.Schoener,Science331,426(2011).

18.Materials and methods are available as supplementary

materials on Science Online.

19.A.A.Agrawal,M.T.J.Johnson,A.P.Hastings,J.L.Maron,

Am.Nat.10.1086/666727(2012);https://www.360docs.net/doc/826732560.html,/stable/

10.1086/666727.

20.M.Karonen,J.Parker,A.Agrawal,J.P.Salminen,Rapid

Commun.Mass Spectrom.24,3151(2010).

21.R.V.Barbehenn,C.P.Jones,A.E.Hagerman,M.Karonen,

J.P.Salminen,J.Chem.Ecol.32,2253(2006).

22.N.G.Hairston Jr.,S.P.Ellner,M.A.Geber,T.Yoshida,

J.A.Fox,Ecol.Lett.8,1114(2005).

23.M.T.J.Johnson,M.Vellend,J.R.Stinchcombe,Philos.Trans.

R.Soc.Lond.B Biol.Sci.364,1593(2009).

24.J.Lubchenco,S.D.Gaines,Annu.Rev.Ecol.Syst.12,405

(1981).

25.A.A.Agrawal,Ecology85,2118(2004).

Acknowledgments:We thank A.Alfano,F.Chen,S.Cook-Patton,

P.Cooper,T.Dodge,N.Durfee,A.Erwin,M.Falise,J.Goldstein,

E.Kearney,A.Knight,S.McArt,J.Peters,S.Rasmann,A.Smith,

T.Ramsey,E.Reyes,M.Weber,and E.Woods for help with

field work and discussion;T.Zhao,J.Yi,and A.Koivuniemi for

assistance with chemical analyses;and J.Good,N.Hairston,

S.McArt,T.Züst,and the Plant Interactions Group at Cornell

University for comments.Molecular work for this study was

conducted in the Evolutionary Genetics Core Facility at Cornell

University with support from V.Askinazi,S.Bogdanowicz,

R.Harrison,https://www.360docs.net/doc/826732560.html,rson,and E.Reyes.Chemical analyses on an

ultraperformance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry

system were made possible by a Strategic Research Grant of

University of Turku.This study was primarily supported by a

U.S.NSF grant(EAGER DEB-0950231),and for this we thank

L.Gough.M.T.J.J.was supported by the Natural Sciences and

Engineering Research Council of Canada,the Government

of Ontario,and a Connaught Early Researcher Award;

J.L.M.was supported by NSF grants DEB0614406and

DEB-0915409;J.-P.S was supported by the Academy of Finland

(grant258992).Data sets for genotype frequencies described

in this paper are available in the DRYAD data repository

under https://www.360docs.net/doc/826732560.html,/10.5061/dryad.6331s.This paper is

dedicated to Paul Feeny and Dick Root.

Supplementary Materials

https://www.360docs.net/doc/826732560.html,/cgi/content/full/338/6103/113/DC1

Materials and Methods

Supplementary Text

Figs.S1to S5

Table S1

References(26–32)

12June2012;accepted13August2012

10.1126/science.1225977

Natural Enemies Drive Geographic Variation in Plant Defenses

Tobias Züst,1*?Christian Heichinger,2Ueli Grossniklaus,2Richard Harrington,3 Daniel J.Kliebenstein,4,5Lindsay A.Turnbull1

Plants defend themselves against attack by natural enemies,and these defenses vary widely across populations.However,whether communities of natural enemies are

a sufficiently potent force to maintain polymorphisms in defensive traits is largely unknown.Here,we exploit the genetic resources of Arabidopsis thaliana,

coupled with39years of field data on aphid abundance,to(i)demonstrate that geographic patterns in a polymorphic defense locus(GS-ELONG)are strongly

correlated with changes in the relative abundance of two specialist aphids;and(ii) demonstrate differential selection by the two aphids on GS-ELONG,using a multigeneration selection experiment.We thereby show a causal link between variation

in abundance of the two specialist aphids and the geographic pattern at GS-ELONG,which highlights the potency of natural enemies as selective forces.

I ntraspecific genetic variation is essential in

enabling species to respond rapidly to evolu-tionary challenges such as changing environ-mental conditions(1)or the emergence of novel

pests and pathogens(2).This diversity often re-

flects the balance between the strength of local

selection and the current and historical levels of

population substructure and gene flow(3,4).

Geographic analyses of genetic variation in

several plant species have revealed clear genetic

signals of local adaptation(5),caused by differ-

ences in the selective regime among locations.

These analyses are further supported by reciprocal

transplant experiments,in which home genotypes

generally outperform those transplanted from

other populations(6,7).Although the drivers of

local adaptation often remain unidentified,there

1Institute of Evolutionary Biology and Environmental Studies

and Zürich-Basel Plant Science Center,University of Zürich,

Zürich CH-8057,Switzerland.2Institute of Plant Biology and

Zürich-Basel Plant Science Center,University of Zürich,Zürich

CH-8008,Switzerland.3Rothamsted Insect Survey,AgroEcol-

ogy Department,Rothamsted Research,Harpenden AL52JQ,

UK.4Department of Plant Sciences,University of California at

Davis,Davis,CA95616,USA.5DynaMo Center of Excellence,

Department of Plant Biology and Biotechnology,University of

Copenhagen,Copenhagen DK-1871,Denmark.

*To whom correspondence should be addressed.E-mail:

tobias.zuest@https://www.360docs.net/doc/826732560.html,

?Present address:Department of Ecology and Evolutionary

Biology,Cornell University,Ithaca,NY14853,USA.

o

n

D

e

c

e

m

b

e

r

2

7

,

2

1

2

w

w

w

.

s

c

i

e

n

c

e

m

a

g

.

o

r

g

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

经纬仪,全站仪操作步骤

电子经纬仪操作步骤 经纬仪是测量工作中的主要测角仪器,由照准部、度盘、基座等部分组成。经纬仪根据度盘刻度和读数方式的不同,分为游标经纬仪,光学经纬仪和电子经纬仪。目前我国较为普遍使用的是电子经纬仪,游标经纬仪和光学经纬仪已逐渐淘汰。 下图为经纬仪各部件组成名称:

经纬仪的安置: 1 、架设仪器: 三脚架调成等长并使架头高度与观测者身高适宜,打开三脚架,使架头大致水平,将经纬仪固定在三脚架上,拧紧连接螺旋,置于测站点之上。 2 、对中: 对中就是使仪器的中心与测站点位于同一铅垂线上。用双手各提一条架脚前后、左右摆动,同时使架头大致保持水平状态,眼观对中标志(激光或十字丝交点)与测站点重合,同时使架头大致保持水平 状态,放稳并踩实架脚。

3 、整平: 整平的目的是使仪器竖轴铅垂,水平度盘水平。根据水平角的定义,是两条方向线的夹角在水平面上的投影,水平度盘一定要水平。(1)粗平:伸缩脚架腿,使圆水准气泡居中。同时检查对中标志是否偏离地面测站点。如果偏离了,旋松三角架上的连接螺旋,平移仪器基座使对中标志精确对准测站点的中心,拧紧连接螺旋并使圆水准气泡居中。 (2)精平:旋转照准部,使其水准管与基座上的任意两只脚螺旋的连线方向平行(图a)。双手同时相向转动两只脚螺旋,使水准管气泡居中;然后将照准部旋转90°(图b),旋转第三只脚螺旋,使气泡居中;如此反复进行,直到水准管在任何方向,气泡均居中为止。 4 、瞄准与读数: 首先将望远镜对向明亮的背景或天空,旋转目镜使十字丝变清晰;然后旋转照准部和望远镜,通过望远镜上的粗瞄准器大概瞄准目标,并将照准部和望远镜制动螺旋制紧;再旋转照准部和望远镜的微动螺旋照准目标,注意检查并消除视差。最后进行读数。

RealTimeRTPCR常见问题分析

Real-Time RT-PCR常见问题分析 1.某一孔荧光信号特别强 问题:同一批样品,其中某一个荧光信号特别强? 原因:①试剂配制时反应液没完全溶化,导致探针量在一管中增多;②试剂配制时没有充分混匀致各管中各成分的量不同;③也可能是PCR仪热槽被荧光物质污染,这 时就要清除热槽中的污染; 2. 扩增曲线有一向上或向下的尖峰 问题:扩增曲线有一向上或向下的尖峰? 原因:①反应过程中电压不稳定;②可能在20循环左右仪器有停下或者仪器有开盖,使得光线突然增强;③如果尖峰向下,也可能是卤素灯老化所致,这时应更换;

3. 部分样本扩增效率过低 问题:部分样本扩增效率过低? 原因:①提取液残留,一定程度抑制了PCR反应;②反应液未严格取量混匀或分装不均匀;③试剂失效; 4.阴性对照或空白对照翘尾,可能原因:1、模板提取环境有污染。2、模板提取操作有 污染。3、配液过程存在污染。 问题:阴性对照或空白对照翘尾? 原因:①模板提取环境有污染;②模板提取操作有污染;③试剂配制过程存在污染;

5. 直线型扩增曲线 问题:直线型扩增曲线? 原因:①探针部分降解(探针降解原因:a.探针反复冻融――稀释的探针可在4℃保存至少3个月,应避免反复冻融;b.探针在光线下暴露时间太长);②反应液中有PCR抑 制物; 6.没有扩增曲线 问题:没有扩增曲线? 原因:①PCR参数设置错误,在设计循环参数时将荧光信号读取时间设在反应的第一步,即stage 1阶段;②电脑设定了自动休眠;

7.基线下滑 问题:扩增曲线有一个下滑阶段? 原因:基线选取范围不对,可试着将基线范围改大一些,这一问题常因试剂质量所致;8.扩增曲线断裂 问题:扩增曲线断裂? 原因:基线选取范围不对,基线终点大于Ct值,这通常是由于模板DNA浓度过高所致,因Ct值<15,而基线范围仍取3-15,其中包含部分扩增信号,导致标准差偏大, 阈值过高,解决办法:减少基线终点至Ct值前4个循环,重新分析数据 9.样品浓度跨度过大 样品浓度过高,至阳性样品扩增曲线在后面循环中呈一向下的直线,原因及解决办法同“扩增曲线断裂”。

经纬仪的使用方法(免费)

第三节经纬仪的使用 一、安臵仪器 安臵仪器是将经纬仪安臵在测站点上,包括对中和整平两项内容。对中的目的是使仪器中心与测站点标志中心位于同一铅垂线上;整平的目的是使仪器竖轴处于铅垂位臵,水平度盘处于水平位臵。 1.初步对中整平 (1)用锤球对中,其操作方法如下: 1)将三脚架调整到合适高度,张开三脚架安臵在测站点上方,在脚架的连接螺旋上挂上锤球,如果锤球尖离标志中心太远,可固定一脚移动另外两脚,或将三脚架整体平移,使锤球尖大致对准测站点标志中心,并注意使架头大致水平,然后将三脚架的脚尖踩入土中。 2)将经纬仪从箱中取出,用连接螺旋将经纬仪安装在三脚架上。调整脚螺旋,使圆水准器气泡居中。 3)此时,如果锤球尖偏离测站点标志中心,可旋松连接螺旋,在架头上移动经纬仪,使锤球尖精确对中测站点标志中心,然后旋紧连接螺旋。 (2)用光学对中器对中时,其操作方法如下: 1)使架头大致对中和水平,连接经纬仪;调节光学对中器的目镜和物镜对光螺旋,使光学对中器的分划板小圆圈和测站点标志的影像清晰。 2)转动脚螺旋,使光学对中器对准测站标志中心,此时圆水准器气泡偏离,伸缩三脚架架腿,使圆水准器气泡居中,注意脚架尖位臵不得移动。 2.精确对中和整平

(1)整平 先转动照准部,使水准管平行于任意一对脚螺旋的连线,如图3-7a 所示,两手同时向内或向外转动这两个脚螺旋,使气泡居中,注意气泡移动方向始终与左手大拇指移动方向一致;然后将照准部转动90°,如图3-7b 所示,转动第三个脚螺旋,使水准管气泡居中。再将照准部转回原位臵,检查气泡是否居中,若不居中,按上述步骤反复进行,直到水准管在任何位臵,气泡偏离零点不超过一格为止。 (2)对中 先旋松连接螺旋,在架头上轻轻移动经纬仪,使锤球尖精确对中测站点标志中心,或使对中器分划板的刻划中心与测站点标志影像重合;然后旋紧连接螺旋。锤球对中误差一般可控制在3mm 以内,光学对中器对中误差一般可控制在1mm 以内。 对中和整平,一般都需要经过几次“整平—对中—整平”的循环过程,直至整平和对中均符合要求。 二、瞄准目标 (1)松开望远镜制动螺旋和照准部制动螺旋,将望远镜朝向明亮背景,调节目镜对光螺旋,使十字丝清晰。 (2)利用望远镜上的照门和准星粗略对准目标,拧紧照准部及望远镜制动螺旋;调节物镜对光螺旋,使目标影像清晰,并注意消除图3-7 经纬仪的整平

经纬仪使用及操作的步骤(光学对中法)

经纬仪使用及操作的步骤(光学对中法) 1、架设仪器: 将经纬仪放置在架头上,使架头大致水平,旋紧连接螺旋。 2、对中: 目的是使仪器中心与测站点位于同一铅垂线上。可以移动脚架、旋转脚螺旋使对中标志准确对准测站点的中心。 3、整平: 目的是使仪器竖轴铅垂,水平度盘水平。根据水平角的定义,是两条方向线的夹角在水平面上的投影,所以水平度盘一定要水平。 粗平:伸缩脚架腿,使圆水准气泡居中。 检查并精确对中:检查对中标志是否偏离地面点。如果偏离了,旋松三角架上的连接螺旋,平移仪器基座使对中标志准确对准测站点的中心,拧紧连接螺旋。 精平:旋转脚螺旋,使管水准气泡居中。 4、瞄准与读数: ①目镜对光:目镜调焦使十字丝清晰。 ②瞄准和物镜对光:粗瞄目标,物镜调焦使目标清晰。注意消除视差。精瞄目标。 ③读数: 调整照明反光镜,使读数窗亮度适中,旋转读数显微镜的目镜使刻划线清晰,然后读数。 现在很多都是使用全站仪,全站仪的使用(以拓普康全站仪为例进行介绍)介绍: (1)测量前的准备工作

1)电池的安装(注意:测量前电池需充足电) ①把电池盒底部的导块插入装电池的导孔。 ②按电池盒的顶部直至听到“咔嚓”响声。 ③向下按解锁钮,取出电池。 2)仪器的安置。 ①在实验场地上选择一点,作为测站,另外两点作为观测点。 ②将全站仪安置于点,对中、整平。 ③在两点分别安置棱镜。 3)竖直度盘和水平度盘指标的设置。 ①竖直度盘指标设置。 松开竖直度盘制动钮,将望远镜纵转一周(望远镜处于盘左,当物镜穿过水平面时),竖直度盘指标即已设置。随即听见一声鸣响,并显示出竖直角。 ②水平度盘指标设置。 松开水平制动螺旋,旋转照准部360,水平度盘指标即自动设置。随即一声鸣响,同时显示水平角。至此,竖直度盘和水平度盘指标已设置完毕。注意:每当打开仪器电源时,必须重新设置和的指标。 4)调焦与照准目标。 操作步骤与一般经纬仪相同,注意消除视差。 (2)角度测量 1)首先从显示屏上确定是否处于角度测量模式,如果不是,则按操作转换为距离模式。 2)盘左瞄准左目标A,按置零键,使水平度盘读数显示为0°00′00〃,顺时针旋转照准部,瞄准右目标B,读取显示读数。

引物设计原则(含Realtime引物)

1.引物最好在模板cDNA的保守区内设计。 DNA序列的保守区是通过物种间相似序列的比较确定的。在NCBI上搜索不同物种的同一基因,通过序列分析软件(比如DNAman)比对(Alignment),各基因相同的序列就是该基因的保守区。 2.引物长度一般在15~30碱基之间。 引物长度(primer length)常用的是18-27 bp,但不应大于38,因为过长会导致其延伸温度大于74℃,不适于Taq DNA 聚合酶进行反应。 3.引物GC含量在40%~60%之间,Tm值最好接近72℃。 GC含量(composition)过高或过低都不利于引发反应。上下游引物的GC含量不能相差太大。另外,上下游引物的Tm值(melting temperature)是寡核苷酸的解链温度,即在一定盐浓度条件下,50%寡核苷酸双链解链的温度。有效启动温度,一般高于Tm值5~10℃。若按公式Tm= 4(G+C)+2(A+T)估计引物的Tm值,则有效引物的Tm为55~80℃,其Tm 值最好接近72℃以使复性条件最佳。 4.引物3′端要避开密码子的第3位。 如扩增编码区域,引物3′端不要终止于密码子的第3位,因密码子的第3位易发生简并,会影响扩增的特异性与效率。 5.引物3′端不能选择A,最好选择T。 引物3′端错配时,不同碱基引发效率存在着很大的差异,当末位的碱基为A时,即使在错配的情况下,也能有引发链的合成,而当末位链为T时,错配的引发效率大大降低,G、C 错配的引发效率介于A、T之间,所以3′端最好选择T。 6. 碱基要随机分布。 引物序列在模板内应当没有相似性较高,尤其是3’端相似性较高的序列,否则容易导致错误引发(False priming)。降低引物与模板相似性的一种方法是,引物中四种碱基的分布最好是随机的,不要有聚嘌呤或聚嘧啶的存在。尤其3′端不应超过3个连续的G或C,因这样会使引物在GC富集序列区错误引发。 7. 引物自身及引物之间不应存在互补序列。 引物自身不应存在互补序列,否则引物自身会折叠成发夹结构(Hairpin)使引物本身复性。这种二级结构会因空间位阻而影响引物与模板的复性结合。引物自身不能有连续4个碱基的互补。 两引物之间也不应具有互补性,尤其应避免3′ 端的互补重叠以防止引物二聚体(Dimer与Cross dimer)的形成。引物之间不能有连续4个碱基的互补。 引物二聚体及发夹结构如果不可避免的话,应尽量使其△G值不要过高(应小于4.5kcal/mol)。否则易导致产生引物二聚体带,并且降低引物有效浓度而使PCR 反应不能正常进行。 8. 引物5′ 端和中间△G值应该相对较高,而3′ 端△G值较低。 △G值是指DNA 双链形成所需的自由能,它反映了双链结构内部碱基对的相对稳定性,△G 值越大,则双链越稳定。应当选用5′ 端和中间△G值相对较高,而3′ 端△G值较低(绝对值不超过9)的引物。引物3′ 端的△G 值过高,容易在错配位点形成双链结构并引发DNA 聚合反应。(不同位置的△G值可以用Oligo 6软件进行分析) 9.引物的5′端可以修饰,而3′端不可修饰。 引物的5′ 端决定着PCR产物的长度,它对扩增特异性影响不大。因此,可以被修饰而不影响扩增的特异性。引物5′ 端修饰包括:加酶切位点;标记生物素、荧光、地高辛、Eu3+等;引入蛋白质结合DNA序列;引入点突变、插入突变、缺失突变序列;引入启动子序列等。引物的延伸是从3′ 端开始的,不能进行任何修饰。3′ 端也不能有形成任何二级结构可能。 10. 扩增产物的单链不能形成二级结构。

经纬仪的操作步骤

经纬仪的操作步骤 1、HR—右旋(顺时针)水平角,HL—左旋(逆时针)水平角。 2、经纬仪的操作步骤(光学对中法) 1 、架设仪器: 将经纬仪放置在架头上,使架头大致水平,旋紧连接螺旋。 2 、对中: 目的是使仪器中心与测站点位于同一铅垂线上。可以移动脚架、旋转脚螺旋使对中标志准确对准测站点的中心。

3 、整平: 目的是使仪器竖轴铅垂,水平度盘水平。根据水平角的定义,是两条方向线的夹角在水平面上的投影,所以水平度盘一定要水平。 粗平:伸缩脚架腿,使圆水准气泡居中。 检查并精确对中:检查对中标志是否偏离地面点。如果偏离了,旋松三角架上的连接螺旋,平移仪器基座使对中标志准确对准测站点的中心,拧紧连接螺旋。 精平:旋转脚螺旋,使管水准气泡居中。 4 、瞄准与读数: ①目镜对光:目镜调焦使十字丝清晰。 ②瞄准和物镜对光:粗瞄目标,物镜调焦使目标清晰。注意消除视差。

精瞄目标。 ③读数: 调整照明反光镜,使读数窗亮度适中,旋转读数显微镜的目镜使刻划线清晰,然后读数。 现在很多都是使用全站仪,全站仪的使用(以拓普康全站仪为例进行介绍)介绍: (1)测量前的准备工作 1)电池的安装(注意:测量前电池需充足电) ①把电池盒底部的导块插入装电池的导孔。 ②按电池盒的顶部直至听到“咔嚓”响声。

③向下按解锁钮,取出电池。 2)仪器的安置。 ①在实验场地上选择一点,作为测站,另外两点作为观测点。 ②将全站仪安置于点,对中、整平。 ③在两点分别安置棱镜。 3)竖直度盘和水平度盘指标的设置。 ①竖直度盘指标设置。 松开竖直度盘制动钮,将望远镜纵转一周(望远镜处于盘左,当物镜穿过水平面时),竖直度盘指标即已设置。随即听见一声鸣响,并显示出竖直角。 ②水平度盘指标设置。

水准仪经纬仪使用方法详细图解

水 准 测 量 基本知识 1.水准测量原理 工程上常用的高程测量方法有几何水准测量、三角高程测量、GPS 测高及在特定对象和条件下采用的物理高程测量,其中几何水准测量是目前高程测量中精度最高、应用最普遍的测量方法。 如图2-1所示,设在地面A 、B 两点上竖立标尺(水准尺),在A 、B 两点之间安置水准仪,利用水准仪提供一条水平视线,分别截取A 、B 两点标尺上读数a 、b ,显然 A B H a H b +=+ A 、 B 两点的高差h AB 可写为 AB h a b =- A 点高程H A 已知, 求出 B 点高程 B A AB H H h =+ 我们规定A 点水准尺读数a 为后视读数,B 点水准尺读数b 为前视读数。 图 2-1 如果A 、B 两地距离较远时,可以用连续水准测量的方法。中间可设置转点TP (临时高程传递点,须放置尺垫),如图2-2所示 11h a =, 333h a b =-,……, n n n h a b =-。 123......AB n i h h h h h h =+++=∑

于是,可以求得A 、B 之间的高程差 AB i i h a b =-∑∑ B 点高程 B A AB H H h =+. 图 2-2 2.水准仪介绍: 水准仪是提供水平视线的仪器,按精度分,水准仪通常有DS 05、DS 1、DS 3等几种。其中“D ”和“S ”分别为“”和“水准仪”首字汉语拼音的首字母,而下标是仪器的精度指标,即每千米测量中的偶然误差(以mm 为单位)。目前常用的水准仪从构造上可分为两大类:利用水准管来获得水平视线的“微倾式水准仪”和利用补偿器来获得水平视线的“自动安平水准仪”。此外,还有一种新型的水准仪——“电子水准仪”,它配合条形码标尺,利用数字化图像处理的方法,可自动显示高程和距离,使水准测量实现了自动化。 水准仪主要由望远镜、水准器、基座三部分组成。 (1) DS 3微倾式水准仪 1.仪器介绍

经纬仪操作步骤

经纬仪的基本操作为:对中、整平、瞄准和读数。 (一)对中 对中的目的是使仪器度盘中心与测站点标志中心位于同一铅垂线上。操作步骤为: 张开脚架,调节脚架腿,使其高度适宜,并通过目估使架头水平、架头中心大致对准测站点。 从箱中取出经纬仪安置于架头上,旋紧连接螺旋,并挂上锤球。如锤球尖偏离测站点较远,则需移动三脚架,使锤球尖大致对准测站点,然后将脚架尖踩实。 略微松开连接螺旋,在架头上移动仪器,直至锤球尖准确对准测站点,最后再旋紧连接螺旋。 (二)整平 整平的目的是调节脚螺旋使水准管气泡居中,从而使经纬仪的竖轴竖直,水平度盘处于水平位置。其操作步骤如下: 1.旋转照准部,使水准管平行于任一对脚螺旋[如图3-7A ]。转动这两个脚螺旋,使水准管气泡居中。

2.将照准部旋转90°,转动第三个脚螺旋,使水准管气泡居中[如图3-7B] 图3-7 整平 3.按以上步骤重复操作,直至水准管在这两个位置上气泡都居中为止。使用光学对中器进行对中、整平时,首先通过目估初步对中(也可利用锤球),旋转对中器目镜看清分划板上的刻划圆圈,再拉伸对中器的目镜筒,使地面标志点成像清晰。转动脚螺旋使标志点的影像移至刻划圆圈中心。然后,通过伸缩三脚架腿,调节三脚架的长度,使经纬仪圆水准器气泡居中,再调节脚螺旋精确整平仪器。接着通过对中器观察地面标志点,如偏刻划圆圈中心,可稍微松开连接螺旋,在架头移动仪器,使其精确对中,此时,如水准管气泡偏移,则再整平仪器,如此反复进行,直至对中、整平同时完成。 瞄准 瞄准目标的步骤如下: 1.目镜对光:将望远镜对向明亮背景,转动目镜对光螺旋,使十字丝成像清晰。

经纬仪操作方法步骤图解

在这里经纬仪操作方法步骤详解图解添加日志标题 经纬仪操作方法步骤详解图解 步骤图解 1、连接螺旋:旋紧连接螺旋, 将仪器固定在三脚架上。 2、调节三脚架:将三脚架打开, 调节高度适中,三条架腿分别 处于测站周围。如果地面松软, 应将架腿踩实。 3、光学对中器:调节光学对中 器的目镜和物镜,使地面清晰 成像。

4、脚螺旋:调节脚螺旋,将仪器精确整平。 5、水平制动螺旋:旋紧水平制动螺旋,照准部被固定。望远镜无法在水平方向内转动。 6、水平微动螺旋:水平制动螺旋旋紧后,旋转水平微动螺旋,照准部在水平方向内微微转动。 7、竖直制动螺旋:旋紧竖直制动螺旋,望远镜被固定在支架上无法转动。

8、目镜调焦螺旋:转动目镜调焦螺旋,使十字丝清晰。 9、水平度盘反光镜:调整水平度盘反光镜,读书窗内数字明亮。 10、竖直度盘反光镜:调整竖直度盘反光镜,使读数窗内读数明亮。 11、读数显微镜:调节读数显微镜,使读书清晰。

12、配盘手轮:调整配盘手轮, 改变水平度盘读数。 水准仪操作步骤方法详解图解 发布: 2009-10-06 09:32 | 作者: admin | 查看: 4次水准仪操作步骤方法详解图解 步骤图解 1、安放三角架:调节三脚架腿至适当 高度,尽量保持三脚架顶面水平。如 果地面松软,应将架腿踩入土中。 2、连接螺旋:旋紧连接螺旋, 将水准仪和三脚架连接在一 起。

3、脚螺旋:调节脚螺旋,使圆水准气泡居中。 4、制动螺旋:旋紧制动螺旋,望远镜被固定。 5、水平微动螺旋:在制动螺旋旋紧后,调节水平微动螺旋,望远镜在水平方向内微小转动。 6、目镜调焦螺旋:调节目镜调焦螺旋,使十字丝清晰成像。

经纬仪全站仪操作步骤

电子经纬仪操作步骤经纬仪是测量工作中的主要测角仪器,由照准部、度盘、基座等部分组成。经纬仪根据度盘刻度和读数方式的不同,分为游标经纬仪,光学经纬仪和电子经纬仪。目前我国较为普遍使用的是电子经纬仪,游标经纬仪和光学经纬仪已逐渐淘汰。 下图为经纬仪各部件组成名称: 经纬仪的安置: 1 、架设仪器: 三脚架调成等长并使架头高度与观测者身高适宜,打开三脚架,使架头大致水平,将经纬仪固定在三脚架上,拧紧连接螺旋,置于测站点之上。 2 、对中: 对中就是使仪器的中心与测站点位于同一铅垂线上。用双手各提一条架脚前后、左右摆动,同时使架头大致保持水平状态,眼观对中标志(激光或十字丝交点)与测站点重合,同时使架头大致保持水平状态,放稳并踩实架脚。 3 、整平: 整平的目的是使仪器竖轴铅垂,水平度盘水平。根据水平角的定义,是两条方向线的夹角在水平面上的投影,水平度盘一定要水平。 (1)粗平:伸缩脚架腿,使圆水准气泡居中。同时检查对中标志是否偏离地面测站点。如果偏离了,旋松三角架上的连接螺旋,平移仪器基座使对中标志精确对准测站点的中心,拧紧连接螺旋并使圆水准气泡居中。

(2)精平:旋转照准部,使其水准管与基座上的任意两只脚螺旋的连线方向平行(图a)。双手同时相向转动两只脚螺旋,使水准管气泡居中;然后将照准部旋转90°(图b),旋转第三只脚螺旋,使气泡居中;如此反复进行,直到水准管在任何方向,气泡均居中为止。 4 、瞄准与读数: 首先将望远镜对向明亮的背景或天空,旋转目镜使十字丝变清晰;然后旋转照准部和望远镜,通过望远镜上的粗瞄准器大概瞄准目标,并将照准部和望远镜制动螺旋制紧;再旋转照准部和望远镜的微动螺旋照准目标,注意检查并消除视差。最后进行读数。 5、水平角测量 在建筑工程施工中,经纬仪主要用于水平角测量,下面只简单介绍一下经纬仪测量水平角的基本步骤: 如图所示: (1)安置经纬仪置于o点,精确调平仪器,使经纬仪处于水平角度测量模式,照准第一个目标A,制动。 (2)按置零键,设置A方向的水平度盘读数为0°00′00"。 (3)顺时针旋转望远镜,照准第二个目标B,制动。此时显示的水平度盘读数即为两方向间的水平夹角β。 竖直角的测量与水平角的测量方法一致,数值也同时显示,若要测量竖直角按上述方法操作,同时读取竖直角即可。 全站仪操作步骤

Real-Time PCR详细介绍

荧光定量PCR实验指南 来源:易生物实验浏览次数:901网友评论0 条 荧光定量PCR实验指南 关键词:荧光实验指南 第一部分 一、基本步骤: 1、目的基因(DNA和mRNA)的查找和比对; 2、引物、探针的设计; 3、引物探针的合成; 4、反应体系的配制; 5、反应条件的设定; 6、反应体系和条件的优化; 7、荧光曲线和数据分析; 8、标准品的制备; 二、技术关键: 1、目的基因(DNA和mRNA)的查找和比对; 从https://www.360docs.net/doc/826732560.html,/网点的genbank中下载所需要的序列。下载的方式有两种:一为打开某个序列后,直接点击“save”,保存格式为“.txt”文件。保存的名称中要包括序列的物种、序列的亚型、

序列的注册号。然后,再打开DNAstar软件中的Editseq软件,点击“file”菜单中的“import”,打开后点击“save”,保存为“.seq”文件。另一种直接用DNAstar软件中的Editseq软件,点击“file”菜单中的“openentrezsequence”,导入后保存为“.seq”文件,保存的名称中要包括序列的物种、序列的亚型、序列的注册号。然后要对所有的序列进行排序。用DNAstar软件中的Seqman软件,点击“sequence”菜单中的“add”,选择要比较的“.seq”的所有文件,点击“add”或“adda ll”,然后点击“Done”导入要比较的序列,再点击“assemble”进行比较。横线的上列为一致性序列,所有红色的碱基是不同的序列,一致的序列用黑色碱基表示。有时要设定比较序列的开始与结尾。有时因为参数设置的原因,可能分为几组(contig),若想全部放在一组中进行比较,就调整“project”菜单下的“parameter”,在“assembling”内的“minimum math percentage”默认设置为80,可调低即可。再选择几个组,点击“contig”菜单下的“reassemble contig”即可。选择高低的原则是在保证所分析的序列在一个“contig”内的前提下,尽量提高“minimum math percentage”的值。有时因此个别序列原因,会出现重复序列,碱基的缺失或插入,要对“contig”的序列的排列进行修改,确保排列是每个序列的真实且排列同源性最好的排列。然后,点击“save”保存即可。分析时,主要是观察是否全部为一致性的黑色或红色,对于弥散性的红色是不可用的。 2、引物和探针设计 2.1引物设计

经纬仪使用教程讲解

经纬仪及角度测量 第一节 角度测量原理 角度测量包括水平角测量和竖直角测量,是测量的三项基本工作之一。角度测量最常用的仪器是经纬仪。水平角测量用于计算点的平面位置,竖直角测量用于测定高差或将倾斜距离改算成水平距离。 一、水平角测量原理 水平角是地面上一点到两目标的方向线投影到水平面上的夹角,也就是过这两方向线所作两竖直面间的二面角。用β表示,角值范围0o~360 o。如图3-1所示,设A 、B 、C 是任意三个位于地面上不同高程的点,B 1A 1、B 1C 1为空间直线BA 、BC 在水平面上的投影,B 1A 1与B 1C 1的夹角β就是为地面上BA 、BC 两方向之间的水平角。 为了测出水平角的大小,可以设想在B 点的上方水平地安置一个带有顺时针刻画、注记的圆盘,并使其圆心O 在过B 点的铅垂线上,有一刻度盘和在刻度盘上读数的指标。观测水平角时,刻度盘中心应安放在过测站点的铅垂线上,直线BA 、BC 在水平圆盘上的投影是om 、on ,此时如果能读出om 、on 在水平圆盘上的读数m 和n ,那么水平角β就等于m 减去n ,即n m -=β。 因此,用于测量水平角的仪器必须有一个能读数的度盘,并能使之水平。为了瞄准不同方向,该度盘应能沿水平方向转动,也能高低俯仰。当度盘高低俯仰时,其视准独应划出一竖直面,这样才能使得在同一竖直面内高低不同的目标有相同的水平度盘读数。 经纬仪就是根据上述要求设计制造的一种测角仪器。 图3-1 水平角测量原理 图3-2 竖直角测量原理 二、竖直角测量原理 竖直角是同一竖直面内视线与水平线间的夹角。角值范围为-90°~+ 90°。视线向上倾斜,竖直角为仰角,符号为正。视线向下倾斜,竖直角为俯角,符号为负。 竖直角与水平角一样,其角值也是度盘上两个方向读数之差。不同的是竖直角的两个方向中必有一个是水平方向。任何类型的经纬仪,制作上都要求当竖直指标水准管气泡居中,望远镜视准轴水平时,其竖盘读数是一个固定值。因此,在观测竖直角时,只要观测目标点一个方向并读取竖盘读数便可算得该目标点的竖直角,而不必观测水平方向。

经纬仪操作规程

经纬仪操作规程 Document serial number【UU89WT-UU98YT-UU8CB-UUUT-UUT108】

经伟仪操作规程 一、操作前准备: 1、到达工作地点后,要先打开经纬仪箱盖,使仪器与环境一致。 2、打开三角架,调节好脚架高度使架头大致水平,稳固地架设在所测角点的上方。 3、用中心连接螺钉将经纬仪固连在在角架上。 二、操作规程: 1、对中: (1)对中时,在连接中心螺旋的钩上悬挂垂球移动三角架,使垂球尖大致对准测站点,将三角架的各脚稳固地踩入地中。 (2)若垂球尖偏离测站点较大,需平移脚架,使垂球尖大致对准测站点,再踩紧脚架;若偏离较小,可略旋移连接中心螺旋,将仪器在架头的圈孔范围内移动,使垂球尖对准测站点,再拧紧连接中心螺旋。 (3)使用光学对中器进行对中时,应首先目估对中和使仪器概略整平。用光学对中器是地,先要对光,然后将仪器在架头上平移,交替使用对中和整平的方法,直到测站点的像落在对中器圆圈的中央,达到既对中又整平。,最后拧紧中心连接螺旋。 2、整平: (1)使照准部水准管平行于任意两个脚螺旋中心的连线方向。 (2)两手同时向内或外旋转这两个脚螺旋,使气泡居中。

(3)旋转照准部90°,使水准管垂直于上述两个脚螺旋连线的方向,然后用第三个脚螺旋使气泡居中。 3、反复多项上述步骤,直至照准部转到任意位置,气泡偏离中央均不超过半格时为止。瞄准: (1)调节目镜使十字丝最清晰,然后用望远镜上的准星和照门(或粗瞄准器),先从镜外找到目标。 (2)当在望远镜内看到目标后,拧紧水平制动螺旋,调节对光螺旋,消除视差,然后调节水平微动螺旋,用十字丝精确瞄准目标。 4、水平角观测方法: (1)测回法,只适用于观测两个方向的单角。 (2)盘左位置。 (3)松开照准部和望远镜照部,由望远镜外的制动螺旋(或板手)转动通过照门和准星粗略瞄准左目标A,拧紧制动螺旋,仔细对光,用照准部与望远镜的微动螺旋,精确瞄准A目标,读取的水平度盘读数。 (4)松开照准部和望远镜制动螺旋,顺时针转动照准部,用上述同样方法瞄准目标B,读记水平度盘读数。 (5)以上两步称上半测回,测得该角角值。 (6)盘右位置。 (7)松开照准部和望远镜制动螺旋,倒转望远镜,逆时针转动照准部、瞄准B点,读记水平度盘读数。 (8)再松开照准部和望远镜制动螺旋,逆时针方向转动照部,瞄准A,读记水平度盘读数。

realtimePCR和RT-PCR详解及其区别要点

real-time PCR技术的原理及应用 摘要:一、实时荧光定量PCR原理(一)定义:在PCR反应体系中 加入荧光基团,利用荧光信号累积实时监测整个PCR进程,最后通过标准曲线对未知模板进行定量分析的方法。(二)实时原理 1、常规PCR技术:对PCR扩增反应的终点产物进行定量和定性分析无法对起始模板准 一、实时荧光定量PCR原理 (一)定义:在PCR反应体系中加入荧光基团,利用荧光信号累积实时监测整个PCR进程,最后通过标准曲线对未知模板进行定量分析的方法。 (二)实时原理 1、常规PCR技术: 对PCR扩增反应的终点产物进行定量和定性分析无法对起始模板准确定量,无法对扩增反应实时检测。 2、实时定量PCR技术: 利用荧光信号的变化实时检测PCR扩增反应中每一个循环扩增产物量的变化,通过Ct值和标准曲线的分析对起始模板进行定量分析 3、如何对起始模板定量?

通过Ct值和标准曲线对起始模板进行定量分析. 4、几个概念: (1)扩增曲线: (2)荧光阈值: (3)Ct值:

CT值的重现性: 5、定量原理: 理想的PCR反应: X=X0*2n 非理想的PCR反应: X=X0 (1+Ex)n

n:扩增反应的循环次数 X:第n次循环后的产物量 X0:初始模板量 Ex:扩增效率 5、标准曲线 6、绝对定量 1)确定未知样品的 C(t)值 2)通过标准曲线由未知样品的C(t)值推算出其初始量

7、DNA的荧光标记: 二、实时荧光定量PCR的几种方法介绍 方法一:SYBR Green法 (一)工作原理 1、SYBR Green 能结合到双链DNA的小沟部位

经纬仪的使用方法

1、HR—右旋(顺时针)水平角,HL—左旋(逆时针)水平角。 2、经纬仪的操作步骤(光学对中法) 1 、架设仪器: 将经纬仪放置在架头上,使架头大致水平,旋紧连接螺旋。 2 、对中: 目的是使仪器中心与测站点位于同一铅垂线上。可以移动脚架、旋转脚螺旋使对中标志准确对准测站点的中心。 3 、整平: 目的是使仪器竖轴铅垂,水平度盘水平。根据水平角的定义,是两条方向线的夹角在水平面上的投影,所以水平度盘一定要水平。 粗平:伸缩脚架腿,使圆水准气泡居中。 检查并精确对中:检查对中标志是否偏离地面点。如果偏离了,旋松三角架上的连接螺旋,平移仪器基座使对中标志准确对准测站点的中心,拧紧连接螺旋。 精平:旋转脚螺旋,使管水准气泡居中。 4 、瞄准与读数: ①目镜对光:目镜调焦使十字丝清晰。 ②瞄准和物镜对光:粗瞄目标,物镜调焦使目标清晰。注意消除视差。精瞄目标。 ③读数: 调整照明反光镜,使读数窗亮度适中,旋转读数显微镜的目镜使刻划线清晰,然后读数。现在很多都是使用全站仪,全站仪的使用(以拓普康全站仪为例进行介绍)介绍: (1)测量前的准备工作 1)电池的安装(注意:测量前电池需充足电) ①把电池盒底部的导块插入装电池的导孔。

②按电池盒的顶部直至听到“咔嚓”响声。 ③向下按解锁钮,取出电池。 2)仪器的安置。 ①在实验场地上选择一点,作为测站,另外两点作为观测点。 ②将全站仪安置于点,对中、整平。 ③在两点分别安置棱镜。 3)竖直度盘和水平度盘指标的设置。 ①竖直度盘指标设置。 松开竖直度盘制动钮,将望远镜纵转一周(望远镜处于盘左,当物镜穿过水平面时),竖直度盘指标即已设置。随即听见一声鸣响,并显示出竖直角。 ②水平度盘指标设置。 松开水平制动螺旋,旋转照准部360,水平度盘指标即自动设置。随即一声鸣响,同时显示水平角。至此,竖直度盘和水平度盘指标已设置完毕。注意:每当打开仪器电源时,必须重新设置和的指标。 4)调焦与照准目标。 操作步骤与一般经纬仪相同,注意消除视差。 (2)角度测量 1)首先从显示屏上确定是否处于角度测量模式,如果不是,则按操作转换为距离模式。2)盘左瞄准左目标A,按置零键,使水平度盘读数显示为0°00′00〃,顺时针旋转照准部,瞄准右目标B,读取显示读数。 3)同样方法可以进行盘右观测。 4)如果测竖直角,可在读取水平度盘的同时读取竖盘的显示读数。 (3)距离测量 1)首先从显示屏上确定是否处于距离测量模式,如果不是,则按操作键转换为坐标模式。2)照准棱镜中心,这时显示屏上能显示箭头前进的动画,前进结束则完成坐标测量,得出距离,HD为水平距离,VD为倾斜距离。 (4)坐标测量 1)首先从显示屏上确定是否处于坐标测量模式,如果不是,则按操作键转换为坐标模式。2)输入本站点O点及后视点坐标,以及仪器高、棱镜高。

realtime pcr 阈值设定

Data Analysis on the ABI P RISM? 7700 Sequence Detection System: Setting Baselines and Thresholds Overview In order for accuracy and precision to be optimal, the assay must be properly evaluated and a few adjustments need to be made. There are three important parameters to be assessed: ?Baseline ?Threshold ?Ct value Data Analysis Tutorial To accurately reflect the quantity of a particular target within a reaction, i.e.the amount of PCR product, it is critical that the point of measurement be accurately determined. Real-time analysis on the ABI P RISM? 7700 Sequence Detection System involves three principle determinants for more accurate, reproducible data. Baseline Value During PCR, changing reaction conditions and environment can influence fluorescence. In general, the level of fluorescence in any one well corresponds to the amount of target present. Fluorescence levels may fluctuate due to changes in the reaction medium creating a background signal. The background signal is most evident during the initial cycles of PCR prior to significant accumulation of the target amplicon. During these early PCR cycles, the background signal in all wells is used to determine the “baseline fluorescence” across the entire reaction plate. The goal of data analysis is to determine when target amplification is sufficiently above the background signal, facilitating more accurate measurement of fluorescence. Threshold The threshold is the numerical value assigned for each run, which reflects a statistically significant point above the calculated baseline. Ct Value The Threshold Cycle (Ct) reflects the cycle number at which the fluorescence generated within a reaction crosses the threshold. The Ct value assigned to a particular well thus reflects the point during the reaction at which a sufficient number of amplicons have accumulated, in that well, to be at a statistically significant point above the baseline.

realtime 数据处理

内参基因:18s for control, 18s for treatment sample 目的基因:control sample, treatment sample 复孔取平均值 △Ct for control sample = Ct of comtrol sample - Ct 18s for control △Ct for treatment sample = Ct of treatment sample - Ct 18s for treatment sample △△Ct = △Ct for treatment sample - △Ct for control sample 2^(-△△Ct) 2^(-△△Ct) =1 means miRNA expression no change 2^(-△△Ct) <1 means expression decrease after treatment 2^(-△△Ct) >1 means expression increase after treatment 我以前是这么做的。不合理的地方,可以拍砖。 第一步,将数据(Ct mean)拷贝到excel。 第二步,计算△Ct。在excel内,计算B2-E2, B3-E3,。。。

第三步,取对照组的△Ct的算术平均数。excel里面是:average (f5,f6,f7) ,得到对照组的△Ct的算术平均数4.242524433 第四步,将F栏内的各个△Ct减去对照组的△Ct,这就是△△Ct。 第五步,将I栏里面的各数,取相反数。也就是(-△△Ct) 第六步,算出2(-△△Ct),excel里面的方程是power(2,N),N指的是(-△△Ct)所在位置。

罗氏realtimepcr操作指南

一.配制好反应体系,封好膜。接通LC480与电脑电源,电脑帐号operator,密码LC480,点击LC480软件,登录帐号user,密码Master1。 二.开始实验:点击,在列表中选择对应的程序,如H1N1或HBV,点击窗口右下角的,点击软件界面右下角的,输入实验文件名点击窗口右下角的开 始实验。 三.编辑子集:点击subset editor,点击左下角的,按ctrl键的同时鼠标选择本次实验的孔,最后点击应用。注意,一次实验可以同时运行相同扩增参数的多个实验 (如H1N1、HIV与HCV),那么可以分别设置多个子集 设置样品:先在subset中选择本次实验的子集,点击左上角的,样品输入样品名,再选择标准品类型和浓度或者阳性 对照/阴性对照 四.数据分析: 实验运行完成后进入,选择Abs Quant/Fit Ppoint, 在窗口中的Subset(第二行)中选择本次实验的子集,点 击软件界面中上方的,在Noise Band中调节 noise band高度,使之处于对数增长期并高于所有噪音信 号,如右图。 再点击进入,点击软件界面中间偏右的 自动设置阈值或手工调节阈值(鼠标左键按住拖动或在 输入阈值大小),再点击软件界面左下角的,软 件左下方出现每个样品的Ct值或浓度值等以及平均值标准误等信 息,该部分可以鼠标拖动滑块或鼠标拖曳、 鼠标点击软件右上角的为本次分析命名,如输入H1N1或其它名称 五.报告输出打印:点击软件右侧的保存当前实验的分析结果,再点击软件左侧的, 选择需要输出的分析结果,如H1N1, 点击软件中部左侧的detailed 分析中建议选择results或standard curve,点击软件界 面左下方的,生成PDF报告,如装了打印机,直接 点击软件中间上方的,或者点击,选择pdf文 件保存位置后点击save保存

罗氏realtime PCR操作指南(Roche LightCycler480)

LightCycler ? 480 系统快速操作指南 1 一.配制好反应体系,封好膜。接通LC480与电脑电源,电脑帐号operator ,密码LC480,点击LC480软件 ,登录帐号user ,密码Master1。 二.开始实验:点击 ,在列表中选择对应的程序,如H1N1或HBV ,点击窗口右下角的,点击软件界面右下角的,输入实验文件名点击窗口右下角的开始实验。 三.编辑子集:点击 subset editor ,点击左下角的,按ctrl 键的同时鼠标选择本次实验的孔,最后点击应用。注意,一次实验可以同时运行相同扩增参数的多个实验(如H1N1、HIV 与HCV ),那么可以分别设置多个子集 设置样品:先在subset 中选择本次实验的子集,点击左上角的,样品输入样品名,再选择标准品类型和浓度或者阳性对照/阴性对照 四.数据分析: 实验运行完成后进入,选择Abs Quant/Fit Ppoint ,在窗 口中的Subset (第二行)中选择本次实验的子集,点击软 件界面中上方的,在Noise Band 中调节 noise band 高度,使之处于对数增长期并高于所有噪音信号,如 右图。 再点击进入,点击软件界面中间偏右的 再点击软件界面左下角的 值或浓度值等以及平均值标准误等信 息,该部分可以鼠标拖动滑块或鼠标拖曳、 鼠标点击软件右上角的为本次分析命名,如输入H1N1或其它名称 五.报告输出打印:点击软件右侧的保存当前实验的分析结果,再点击软件左侧的,点击软件中部左侧的detailed 选择需要输出的分析结果,如H1N1, 分析中建议选择results 或standard curve ,点击软件界面左 下方的,生成PDF 报告,如装了打印机,直接 点击软件中间上方的 ,或者点击,选择pdf 文件保存位置后点击save 保存