Treatment options in hepatocellular carcinoma today

Scandinavian Journal of Surgery 100: 22–29, 2011

TreaTmenT opTions in hepaTocellular carcinoma Today

T. livraghi1, h. m?kisalo2, p.-d. line3

1 Interventional Radiology Department, Istituto Clinico Humanitas, Rozzano, Milano, Italy

2 Department of Surgery, Helsinki University Hospital, Helsinki, Finland

3 Department of Organ Transplantation, gastroenterology and nephrology, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway

absTracT

hepatocellular carcinoma (hcc) is the third most common cause of cancer related death worldwide. as over 90% of hccs arise in cirrhotic livers preventive methods and sur-veillance policies have been adopted in most countries with high prevalence of hepatitis b or c infected people. poor prognosis of hcc has shown some improvement during the last years. Targeted therapy with radiofrequency ablation (rFa), hepatic resection (hr), liver transplantation (lT), and transcatheter arterial chemoembolisation (Tace) seems to have an influence on this development. The heterogeneity of cirrhotic patients with hcc is still a big challenge. a patient with a small tumour in a cirrhotic liver may have a worse prognosis than a patient with a large tumor in a relatively preserved liver after “curative” hr. The choice of the treatment modality depends on the size and the number of tumours, the stage and the cause of cirrhosis and finally on the availability of various modalities in each centre.

Key words: HCC; hepatocellular carcinoma; radiofrequency ablation; percutaneous ablation procedures; percutaneous ethanol injection; intra-arterial therapy; transcatheter chemoembolization; liver resection; liver transplantation

Correspondence:

Heikki M?kisalo, M.D. Department of Surgery Helsinki University Hospital FI - 00029, Helsinki, Finland Email: heikki.makisalo@hus.fi influence of HCV infections transmitted before 1990 the incidence of HCC could be expected to decline after 5–10 years in the Western Europe. Thus, the metabolic syndrome, diabetes, non-alcoholic steato-hepatitis, and excessive alcohol consumption may be the main risk factors of HCC in the future.

Due to HCC’s grim prognosis, there has been a great research effort made in order to come up with efficient therapeutic strategies to cure this disease. Like most other solid tumours, surgery plays a fun-damental role in its treatment. Surgical resection (HR), local ablation therapies, and liver transplanta-tion (LT) are regarded as potentially curative treat-ment modalities depending on the size and number of tumors. It is estimated that curative treatment with either HR or radiofrequency ablation (RFA) can be offered only to 10% of all HCC patients having 3 or fewer 3 cm or smaller HCCs (3). However, with rou-tine screening of high-risk patients more early HCC cases are going to be diagnosed allowing radical treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) ranks fifth among the most prevalent cancers in the world and is the third most common cause of cancer related mortality (1). There is a marked variation in occurrence of HCC among geographic regions and between men and women. The latest age-adjusted annual incidence rates per 100.000 in men are 13 in Italy and 2 to 4 in the Nordic countries (2). The respective figures in females were 3 in Italy and 1 to 2 in the Nordic coun-tries. Along with HBV vaccination and with declining

23 Treatment options in hepatocellular carcinoma today

LT has been offered to selected patients with HCC. However, up until the mid nineties, the results were disappointing with reported overall five-year sur-vival rates ranging from 30 to 40%. In 1996, Mazzaf-erro and co-workers published a pivotal paper, dem-onstrating excellent 4-year survival data and low re-currence rates in patients with early stage, unresect-able HCC (4). This led to the formation of the globally utilised Milan criteria (solitary tumour less than 5 cm or up to three nodules each less than 3 cm) for select-ing HCC patients to LT.

STAgINg SySTEMS

The purpose of staging HCC tumours is to classify each case according to a certain predictable prognosis with optimal treatment. Staging is usually based on diagnostic radiological morphology. Classically, the TNM system has been utilised for classification of solid tumours and is as follows in HCC; T1: 1 nodule < 2 cm, T2: 1 nodule up to 5 cm or 3 nodules up to 3 cm, T3: one or more tumours > 5 cm, and T4: tumour extending into neighbouring organs.

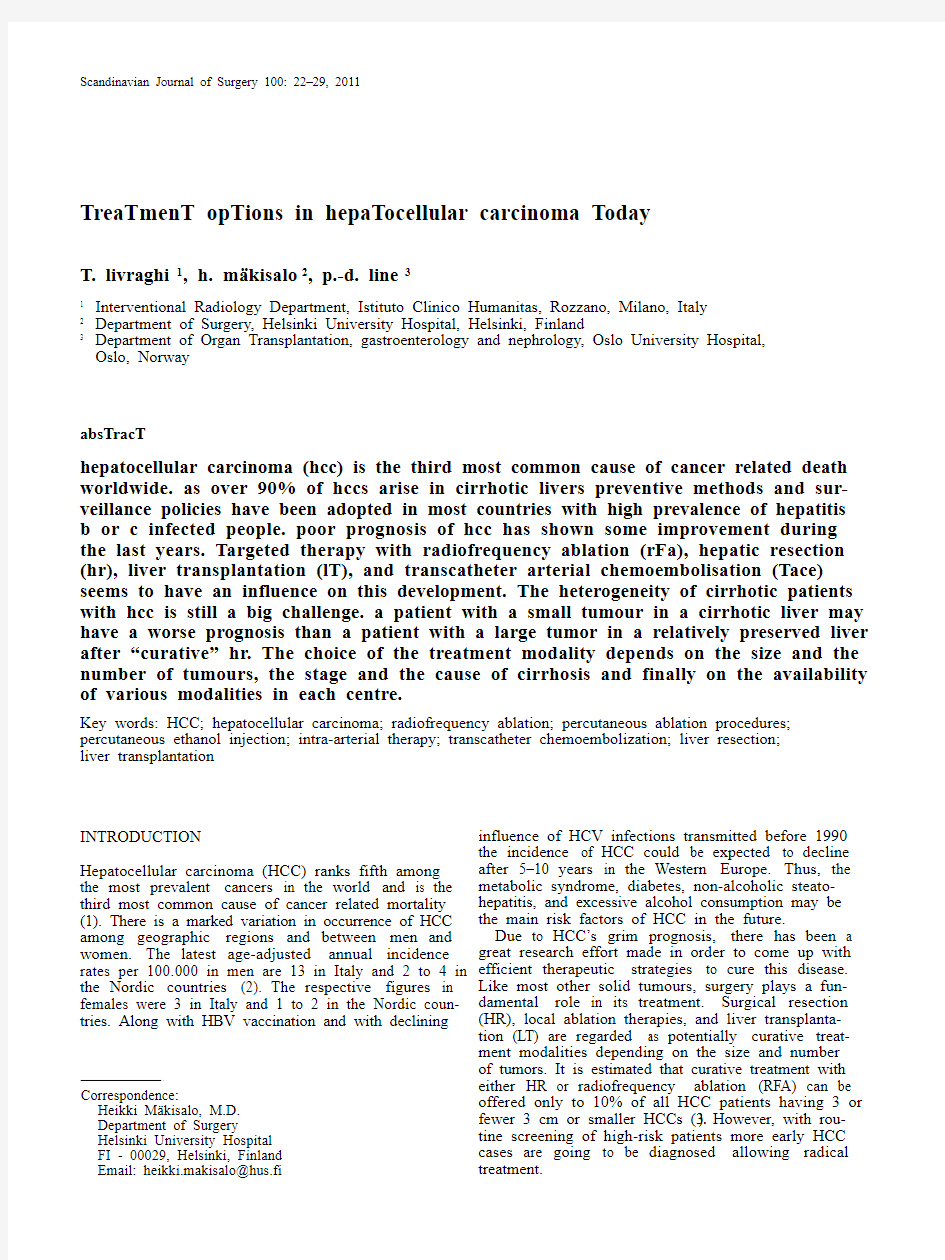

The significance of the liver function requires a more complex clinical classification system as a basis for therapeutic allocation. The Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system (Fig. 1) (5) is the only validated system which includes in addition to tumor burden patient’s performance status and liver func-tion when determining the prognosis after the treat-ment (6). BCLC THERApEUTIC FLOW-CHART

BCLC therapeutic flow-chart for HCC patients (Fig.

1) and its recommendations, because endorsed by EASL (the European Association for the Study of the Liver) and AASLD (American Association for the Study of Liver Disease), are the most applied world-wide (7). The main recommendations adopted by EASL and AASLD are:

a) patients who have a single lesion can be offered

surgical resection in the presence of cirrhosis with preserved liver function, normal bilirubin and he-patic vein pressure gradient < 10 mm Hg.

b) LT is an effective option for patients with HCC

corresponding to the Milan criteria.

c) Local ablation is a safe and effective therapy for

patients who cannot undergo resection, or as a bridge to transplantation. Alcohol injection and radiofrequency are equally effective for tumours < 2 cm. However, the necrotic effect of radiofre-quency is more predictable in all tumour sizes. d) No recommendations can be made regarding ex-

panding the listing criteria beyond the standard Milan criteria.

e) TACE (transcatheter arterial chemoembolisation)

is recommended as first line non-curative therapy for non surgical patients with large-multifocal HCC who do not have vascular invasion or extra-hepatic spread.

f) Systemic or selective intra-arterial chemotherapy

is not recommended and should not be used as standard cure.

Fig. 1. The Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system. Modified from Llovet et al (5).

24T. Livraghi, H. M?kisalo, P.-D. Line

IS THE BCLC FLOW-CHART STILL VALID?

The strictness of protocols for cancer treatment is uni-versal and the BCLC therapeutic flow-chart is not an exception. However, heterogeneity of HCC presenta-tions together with the variable stage of cirrhosis might require a less defined strategy. Furthermore, based on particular therapeutic experience and tech-nical improvements and refinements, some leading centres in recent years have queried certain BCLC/ AASLD treatment allocations and proposed different strategies.

In our opinion, with regard to percutaneous abla-tion therapies (pATs) such as percutaneous RFA or ethanol injection (pEI), and to intra-arterial therapies (IATs) such as TACE, BCLC/AASLD guidelines could currently be modified as follows.

STAgE 0 tumours include carcinoma in situ or very early single tumours smaller than 2 cm in diameter. The liver disease is not worse than Child-pugh class A cirrhosis and the patient should be fully active (performance status, pST 0). This stage is distin-guished from the stage A of the lack or rarity of perinodular neoplastic invasion. pathological speci-mens describe a well-differentiated nodule with in-distinct margins (the so-called “indistinct” type) that contains bile ducts and portal veins, to which the radiological pattern well correlates showing portal blood supply without tumour staining. To be exact, in relation to the local invasiveness, the correct cut-off of “very early” stage should have been fixed at 1.5 cm in size. In fact pathologists, between 1.5–2.0 cm, de-scribe nodules (the so-called “distinct” type or small advanced type) containing zones of less differenti-ated tissue with more intense proliferative activity that give rise to portal microinvasion or microsatel-lites in 10–20% of the cases (usually within 10 mm of the nodule). Increasing the diameter, the rate of mi-croinvasion increases proportionally, i.e. 30–60% in nodules 2–5 cm and up to 60–80% above 5 cm of size (8, 9).

When feasible, HR is considered the treatment of choice in patients who are not candidates for LT. This statement was not based on randomized controlled trials (RCTs) vs other options, but on the oncological assumption that HR is the more suitable option for obtaining complete tumour ablation with “safety margins” around it. This statement was established in spite of several cohort studies comparing HR and pATs that failed to demonstrate better results in fa-vour of HR (10–13). Now some RCTs are available, all revealing that OS rates in patients with early HCC are similar after pAT (principally RFA) and HR (14–16). In “very early” HCC, due to the smaller tumour size, RFA should probably offer even better overall sur-vival (OS) because of its higher local efficacy than in “early” HCC.

Are the safety margins around the tumour more safe with HR than RFA when treating “very early” tumours? Aiming to a safety margin RFA obtained a sustained complete response in 97.2% of 218 cases (17). According to the histopathological study of Sa-saki only one case of “very early” HCC out of 100 cases presented a microsatellite more than 10 mm distant (18). Of course, the best way to determine whether RFA is more effective than HR for “very early” stage would obviously be by direct compari-son in a RCT. However, the results in the studies re-viewed above indicate that the difference between the two approaches is fairly small, and the sample size required to ensure meaningful results is quite large. For this reason a trial of this sort is probably not fea-sible. To give shape to such a trial a recent Markov model analysis was applied (19). Its conclusion was that RFA followed by HR for the few cases of initial local treatment failure was nearly identical to HR re-garding OS, even with the best scenario for HR and the worst scenario for RFA. Albeit under an equiva-lent OS, RFA offers lower complication rate, negligi-ble perioperative mortality, lower ablation of non-neoplastic tissue, and lower costs by reducing treat-ment times, hospital stay, material used, and need for blood transfusions.

All the studies comparing RFA to pEI were in fa-vour of RFA, in terms of shortness of treatment, local efficacy, OS and disease free survival, while the only initial advantage of pEI was the relatively lower com-plications rate (20–21). When the learning curve was over and the risk conditions were known, the com-plications and mortality rates compared with those of pEI. However, pEI remains recommended in cases contraindicated for RFA and, of course, where RFA is not available.

In summary, referring to points “a” and “c” of AASLD recommendations, there are good reasons to suggest that RFA should replace HR as therapeutic gold standard for patients with “very early” HCC. Furthermore, RFA is preferable to pEI also in HCC < 2 cm in that it can obtain higher local efficacy in cases presenting perinodular invasiveness. However, RFA is comparable to HR only in centres with a high ex-perience of the procedure. The long learning-curve of RFA is much more difficult to achieve in countries with low prevalence of HCC.

Stage A tumours are early single tumours or 3 nod-ules smaller than 3 cm in diameter, Child-pugh class is A or B, and pST 0. Although demonstrating com-parable OS when comparing HR to pAT (10–13), these cohort studies were flawed by critical drawbacks in baseline characteristics between the groups, particu-larly regarding the better liver function for HR pa-tients. Severe fibrosis is not only associated with ear-lier liver failure but also with a higher risk of multi-centric carcinogenesis strongly influencing the final outcomes. Some of these studies compared OS ac-cording to the number and to the diameter of the nodules as well. Multiplicity resulted a favourable factor for patients treated with RFA, probably be-cause of the higher loss of nonneoplastic tissue after HR that could anticipate the liver decompensation. The efficacy of RFA is known to be size dependent. After pATs, OS of patients with nodules < 3 cm in diameter was higher than that of carriers of nodules with a diameter 3–5 cm. Why did the RCTs demon-strate that OS rates in patients with “early” HCC are similar after pAT (principally RFA) and HR, even with nodules > 3 cm (14–16)? In fact, it would be rea-sonable to expect better OS rates among patients sub-

25 Treatment options in hepatocellular carcinoma today

mitted to HR, which is seemingly the only method capable of ensuring complete ablation of nodules ac-companied by peritumoral microinvasion. The equi-valent outcome probably reflects the compensatory effects of certain advantages of RFA, i.e. less destruc-tion of normal tissue and lower morbidity rate, with respect to the higher local efficacy of HR.

In summary, there are good reasons suggesting that RFA should be coupled with HR as therapeutic gold standard for selected patients with “early” HCC, i.e. with Child-pugh class B, or with multiple tu-mours. With regards to the size, in single nodules > 3 cm HR remains the first option, while in nodules 2–3 cm a peer discussion is advisable, according to indi-vidual clinical parameters (age, site, associated dis-eases, risk conditions) and to the operator’s expertise. Of course, when the patient is considered inoperable, RFA can be indicated also in huge tumours, even in combination with other procedures (13,22).

Stage B tumours are intermediate, multinodular tu-mours, and the patients have either Child A or B cir-rhosis and are of pST 0. It is worth emphasizing that the “intermediate” stage includes a very wide range of tumoural presentations, i.e. from four small to doz-ens (or uncountable) tumours of various sizes occu-pying a large part of the liver. Such a variety of pos-sibilities makes it difficult to compare the trials con-cerning the IAT results. Of note, the survival im-provement after conventional TACE (cTACE) seems to be marginal, as one meta-analysis did not find a significant OS difference between treatment versus supportive care alone (23). Unlike some earlier RCTs were in favour of cTACE a more recent RCT was not able to demonstrate an improvement in OS after cTACE versus inactive treatments (24). The key clini-cal problem is whether all patients with “intermedi-ate” stage should receive cTACE or only a subgroup of them. To date, cTACE has been considered the standard option for patients with “intermediate” stage, even though several important issues remain to be clarified, including what is the best chemother-apeutic drug (doxorubicin, cisplatin, mitomycin, etc), what is its best dosage, what is the best embolisation agent (gelatin sponge, autologous blood clots, poly-vinyl alcohol particles, etc), what is the efficacy of Lipiodol, and what is the optimum time interval for re-treatment (scheduled or “on demand”). However, the evidence of an additive antitumoural effect with consequent higher efficacy and better OS of cTACE versus cTAE is unavailable, suggesting that ischemia might be the more important factor inducing tumour response after cTACE. For this reason IAT is a con-tinuous “work in progress” field. To improve the modest, if any, therapeutic efficacy of cTACE and to reduce its induced ischemic damage to the non-neo-plastic tissue and its systemic toxicity, some new techniques were recently proposed. TAE with small spherical embolic particles (25) and TACE with non-resorbable hydrogel drug-eluting beads (DEB) capa-ble of being loaded with anthracyclin derivates such as doxorubicin, seem to offer such advantages. An-other possibility is offered by advancements in mi-crocatheter technology, which facilitates “ultraselec-tive” catheterization of nodule feeders and the over-flow of Lipiodol into the portal vein, a factor associ-ated with lower local recurrence (26).

The multikinase inhibitor sorafenib has antiangio-genic and antiproliferative properties and is the first agent to demonstrate a statistically significant im-provement in OS (27). Sorafenib is now considered as standard care of patients with advanced HCC in many centres to patients having Child A cirrhosis and good performance status. Sorafenib is also used in an adjuvant setting after surgery or RFA (STORM trial) and combined with TACE (SpACE trial, phase II, www.clinical https://www.360docs.net/doc/942960833.html,).

Referring to point “e” of AASLD recommenda-tions, cTACE is no longer regarded as the standard treatment of “intermediate” stage, being comparable to cTAE. However, new selective techniques, such as TAE with small particles, TACE with DEB or “ultrase-lective” TACE seem to be more effective obtaining a not negligible rate of complete responses, and avoid-ing the damage of nonneoplastic tissue. In advanced HCC with preserved liver function sorafenib may be considered as a palliative treatment.

OpERATIVE OpTIONS ARE STILL NEEDED

IN HCC

Despite emphasizing the role of ablative treatment of potentially curable HCC, HR and LT remain as the basic treatment modalities in certain indications. Liver resection.It is reasonable that with surveil-lance programs RFA is the mainstay in areas with a high prevalence of HCC associated to viral hepatitis. Elsewhere most of tumours are found in a sympto-matic phase and quite often in a non-cirrhotic liver as well. In these cases HR can still be regarded as the “gold standard” when feasible. Without aggressive treatment of these patients with the best supportive care the median survival is less than 1 year (28).

As a result of advances in surgical techniques and peri-operative management the hospital mortality after HR is practically zero and morbidity less than 20% when resecting livers of healthy or Child A cir-rhotic patients in experienced centres (29). Similar 5-year survival has been seen regardless the patient had cirrhosis or not but disease-free survival is de-creased in cirrhotic patients (30). Tolerance to HR de-pends, however, on the degree of impaired liver func-tion and portal hypertension. If the patient has sig-nificant portal hypertension 5-year survival is only 25% compared to 74% in patients without portal hy-pertension and with normal bilirubin level (31). One of the advantages of HR over RFA suggested has been a better contol of micrometastases with ana-tomic resections. A large Japanese study on 72.744 patients with a single HCC showed an improved disease-free survival after an anatomical subsegmen-tectomy than after non-anatomical minor hepatec-tomy but only when the tumour size was between 2 cm and 5 cm (32). In congruence, in the consensus statement for the treatment of HCC the Japanese So-ciety of Hepatology (JSH) preserved HR to tumours more than 3 cm in diameter and 3 or less in number in patients with Child A cirrhosis (33). HR was also

26T. Livraghi, H. M?kisalo, P.-D. Line

regarded as an alternative to RFA in smaller tu-mours.

Significant risk factors for early recurrence are tu-mour rupture, venous invasion and cirrhosis, whereas viral replication in viral hepatitis and multiple tu-mours increase the risk for late recurrence (34,35). Controversy exists related to the surgical margin as HCC seldom recurs to the resection surface (36,37). Nevertheless, it is highly recommended that the tu-mour should not be exposed during the surgery.

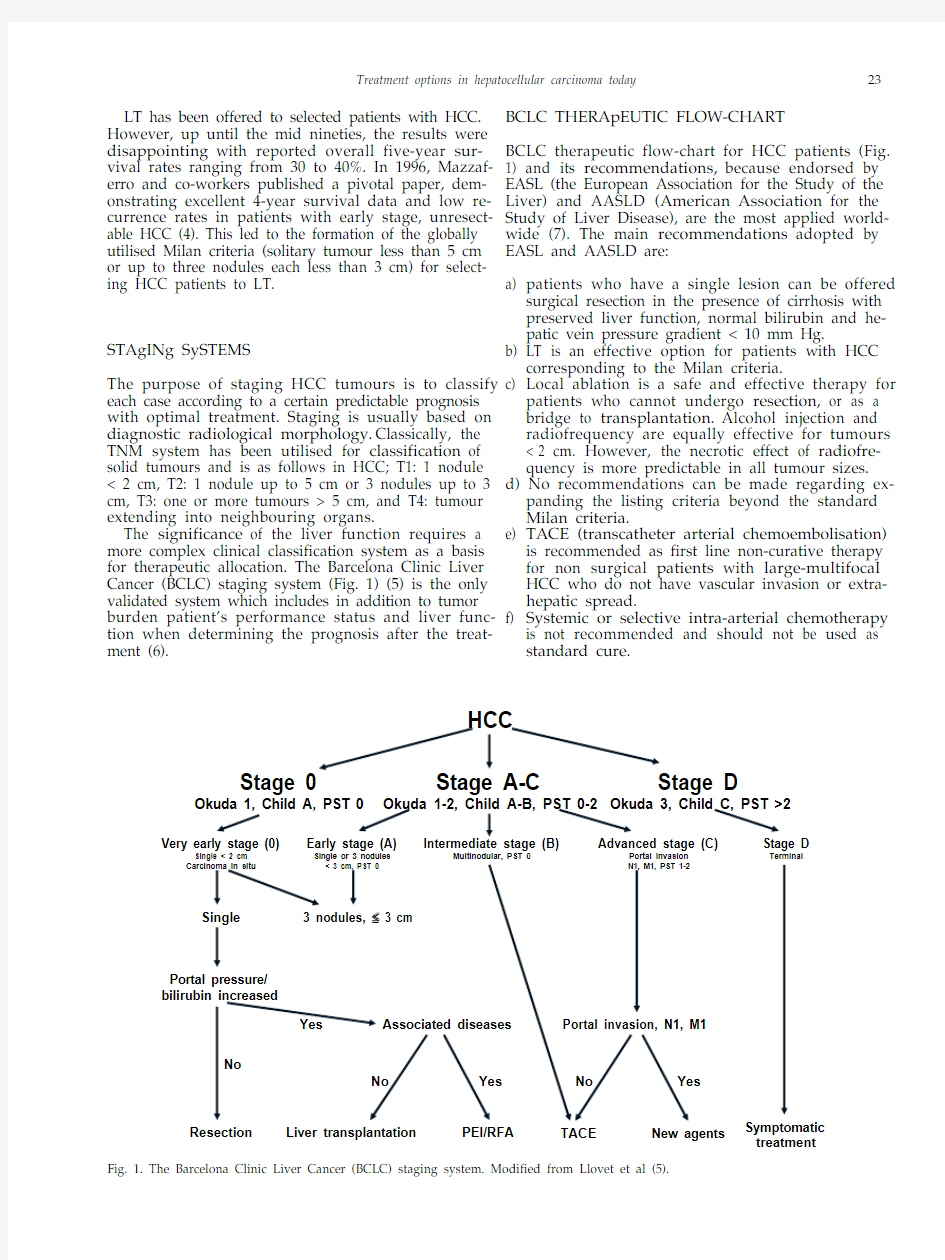

Vascular invasion is a prognostic indicator of HCC despite the treatment modality and its risk is high in tumours more than 5 cm in diameter (38). Neither HR nor LT are usually recommended when vascular in-vasion has been established. However, when feasible HR is the only alternative of a large HCC without proven dissemination (Fig. 2).

Liver transplantation. Excellent results after LT us-ing Milan criteria from the study by Mazzaferro have been reproduced multiple times by other researchers, and the results seem to be robust and valid across different populations and etiologic backgrounds (39). However, only a minority of HCC patients can be treated with LT due to the scarcity of organs available for transplantation and increasing waiting times in most countries.

Selection criteria . Independently of TNM stage, the presence of vascular invasion is a determining pa-rameter for aggressive disease and recurrence follow-ing LT or HR, but this factor can only be assessed on histology and is thus not available for preoperative evaluation (40). TNM stage 2 (T2) comprises the Mi-lan criteria. The prognosis of patients exceeding these limitations is more unpredictable, and the Milan cri-teria can in this sense be viewed as a surrogate marker for “absence” of vascular invasion. Another prognos-tic factor of significance is alpha-fetoprotein (AFp). AFp level higher than 400 μg/l is a sign of either ag-gressive and/or advanced disease (40). The problem in a population setting, however, is that AFp levels are not sensitive and specific enough to be of true staging value, whereas it can be of significance in the judgement of an individual patient (40).

In a cohort study of multiple centres, the impact of staging on post explant pathology (diameter of larg-est tumour, number of nodules and vascular inva-sion) survival was explored and correlated to post

transplant survival and recurrence (41). The results

A B

C D

Fig. 2. A and B represent a large hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with a good prognosis after right lobectomy. C and D: Child B cirrho-sis with a 3 cm HCC and a suspected satellite nodus less than 1 cm in the right lobe. Liver transplantation was the only option available for the patient.

27 Treatment options in hepatocellular carcinoma today

show that the diameter of the largest tumour is a more important predictor for survival and recurrence than the number of nodules (Fig. 2). Furthermore, a subgroup of patients where the sum of the diameter of the largest tumour and the total number of nodules were equal to seven, (“up to seven” criteria), dis-played a survival benefit that was not significantly different from those within the Milan criteria. An-other approach to tumour morphologic criteria has been total tumour volume (TTV). This has the advan-tage of excluding the number of nodules which are of less significance than size. TTV of less than 115 cm3 has proven to provide similar results as the Milan criteria (35, 42).

Transplantation beyond the Milan criteria. The con-cept of limiting transplantation to BCLC A patients is inherently linked to the scarcity of liver grafts avail-able. Due to the unpredictable availability, different waiting times and local or national guidelines of the LT indications with respect to tumour size and stages vary.

In general, the outcome after LT for HCC should ideally be comparable to transplantation for benign indications. If transplants are performed outside the established criteria, this should not lead to extended waiting times or exclusion of other patients. In coun-tries where the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) is used for liver allocation, HCC patients within the Milan criteria are granted extra points to ensure access to transplantation within reasonable time.

In the Asian countries, the availability of deceased donor grafts is very low or absent. Hence, the major-ity of grafts are derived from a living donor. In living donation, the question of excluding other recipients from the access to LT becomes irrelevant. Living do-nation enables the waiting times to be short and might also encourage transplantation of patients on extended criteria.

In Scandinavia, LT for HCC comprises 7.9% of all transplants performed, reflecting a low incidence of the disease. Concomitantly, the waiting times in the Nordic countries are in international comparison short, particularly in Norway, Finland and Sweden, and somewhat longer in Denmark (43). Apparently this fact might have an impact on the LT indications. The overall five-year survival for LT for HCC in the Nordic countries is 57.4%, indicating that a propor-tion transplants are most likely done on extended criteria (43). Is this an acceptable outcome in LT? The survival data from registries like the Nordic Liver Transplant Registry (NLTR) or the European Liver Transplant Registry (ELTR) indicate that LTs in cases with the actual 5 year survival of about 50%, such as reLT for hepatitis C are still performed (43, 44). Transplantation on extended criteria does, how-ever, raise certain issues of concern. patients with more advanced disease have an increased risk of dropout on the waiting list, particularly when the waiting times exceed more than 100 days (31). Con-versely, very short waiting times might preclude the natural selection process and lead to transplantation of poor candidates that have a very high likelihood of recurrence and short post transplant survival (45). This might be of particular relevance in living donor transplantation, and increased recurrence rates com-pared to whole graft deceased donor grafts have been reported in the literature (46).

Strategies such as neoadjuvant treatment or down-staging to improve outcome in extended criteria transplantation have been suggested. Neoadjuvant treatments are given prior to the transplant procedure in order to improve post transplant outcome, whereas downstaging is a term describing lowering the pa-tients’ morphological stage. Bridging, on the other hand, is a related strategy to keep patients that qual-ify for transplantation able to stay on the waiting list for an extended time, i.e. preventing them from drop-ping out (45).

In all these instances, locoregional therapies RFA or TACE can be utilised (47). There are data available, suggesting that the rate of dropouts might be reduced by adopting bridging strategies for T2 tumours where the waiting times exceed 6 months (45). Furthermore, some studies suggest that the response to TACE or RFA as downstaging modalities can be utilised as a selection criteria for transplantation in patients out-side Milan (48). It has been proposed that a proper response to downstaging should be evaluated by both radiology (Milan criteria) and reduction in AFp levels (47). Conventional Recist criteria appears to be poorly adapted for evaluating the response to TACE and RFA, and new, modified criteria (mRecist – mod-ified Recist) have been proposed (49).

Another attempt to improve survival after LT in HCC is to modify the immunosuppressive regimen. Immunosuppression is in itself associated with an increased risk of malignancy and might facilitate tu-mour growth and metastasis. Anti-proliferative agents, like the m-Tor inhibitor rapamycin, could possibly offer an oncological benefit, particularly in patients outside the Milan criteria (50). A large ran-domised study comparing conventional immunosup-pression to rapamycin that might give a better answer to this question is underway (51).

HEpATIC RESECTION OR LIVER TRANSpLANTATION?

The excellent results after LT using the Milan criteria in HCC patients are impaired with the scarcity of organs as the dropout rate may be up to 30% because of progression of the disease during the waiting time (28). HR has been estimated to yield similar results as LT on the intention-to-treat- basis (52). However, five-year disease-free survival even after curative HR of small HCCs has been only 22–36% (30, 53) and on long-term the recurrence may be regarded as almost universal. Thus the best long-term result of a multifo-cal HCC could be reached with LT. Nevertheless, LT may have a significant role in the treatment of HCC only in countries of low prevalence of HCC leaving both RFA and HR as the treatments of choice in the high prevalence areas. With a close follow-up recur-rent tumours should be treated actively with RFA. In addition, there is an evidence that the results of

a salvage LT after HR are not inferior to primary LTs

(54). According to poon et al. almost 80% of patients primarily treated with “curative” HR could later be

28T. Livraghi, H. M?kisalo, P.-D. Line

treated with LT (30). A rapid recurrence after HR re-fers to a metastatic disease and late recurrences to metachronic tumours with a better prognosis after LT (34). In fact, early recurrence within one year could be regarded as a contraindication to LT.

CONCLUSION

During the last years the major influence on the prog-nosis of HCC in developed countries has been achieved by surveillance, early diagnosis, and multi-disciplinary treatment of the disease. After detecting the tumour a targeted therapy with RFA, HR, TACE, or LT or with their combinations gives the patient the best chance for survival. Neoadjuvant therapy and downstaging strategies as well as novel immunosup-pressive regimens might be of relevance, but further studies are needed to validate these measures in liver transplantation for HCC.

REFERENCES

1. Rampone B, Schiavone B, Martino A, et al: Current manage-

ment strategy of hepatocellular carcinoma.World J gastroen-terol 2009;15:3210–3216

2. Mcglynn KA, Tsao L, Hsing AW, et al: International trends and

patterns of primary liver cancer. Int J Cancer 2001;94:290–296 3. Kudo M: Radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carci-

noma: updated review in 2010. Oncology 2010;78:113–124 4. Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, et al: Liver transplantation

for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in pa-tients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 1996;334:693–699

5. Llovet JM, Bru C, Bruix J: prognosis of hepatocellular carci-

noma: the BCLC staging classification. Semin Liver Dis 1999;19: 329–338

6. Marrero JA, Fontana RJ, Barrat A, et al: prognosis of hepatocel-

lular carcinoma: comparison of 7 staging systems in an Amer-ican cohort. Hepatology 2005;41:707–716

7. Bruix J, Sherman M: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma.

Hepatology 2005;42:1208–1236

8. Kojiro M, Nakashima O: Histopathologic evaluation of hepa-

tocellular carcinoma with special reference to small early stage tumors. Semin Liver Dis 1999;19:287–296

9. Okusaka T, Okada S, Ueno H, et al: Satellite lesions in patients

with small hepatocellular carcinoma with reference to clinico-pathologic features. Cancer 2002;95:1931–1937

10. Livraghi T, Bolondi L, Buscarini L, et al: No treatment, resec-

tion and ethanol injection in hepatocellular carcinoma: a ret-rospective analysis of survival in 391 patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol 1995;22:522–526

11. Hong SN, Lee Sy, Choi MS, et al: Comparing the outcomes of

radiofrequency ablation and surgery in patients with a single small hepatocellular carcinoma and well-preserved hepatic function. J Clin gastroenterol 2005;39:247–252

12. Wakai T, Shirai y, Suda T, et al: Long-term outcomes of hepa-

tectomy vs percutaneous ablation for treatment of hepatocel-lular carcinoma. World J gastroenterol 2006;12:546–552

13. Nanashima A, Masuda J, Miuma S, et al: Selection of treatment

modality for hepatocellular carcinoma according to the modi-fied Japan Integrated Staging score. World J gastroenterol 2008;14:58–63

14. Huang gT, Lee pH, Tsang yM, et al: percutaneous ethanol

injection versus surgical resection for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective study. Ann Surg 2005;

242:236–242

15. Chen MS, Li JQ, Zheng y, et al: A prospective randomized

trial comparing percutaneous local ablative therapy and par-tial hepatectomy for small hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg 2006;243:321–328

16. Lu MD, Kuang M, Liang LJ, et al: Surgical resection versus

percutaneous thermal ablation for early-stage hepatocellular

carcinoma: a randomized clinical trial. Zhonghua yi Xue Za Zhi 2006;86:801–805

17. Livraghi T, Meloni F, Di Stasi M, et al: Sustained complete re-

sponse and complications rates after radiofrequency ablation of very early hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: Is resection still the treatment of choice? Hepatology 2008;47:82–89

18. Sasaki y, Imaoka S, Ishiguro S, et al: Clinical features of small

hepatocellular carcinomas as assessed by histologic grades.

Surgery 1996;119:252–260

19. Cho yK, Kim JK, Kim WT, et al: Hepatic resection versus ra-

diofrequency ablation for very early stage hepatocellular car-cinoma: a Markov model analysis. Hepatology 2010;51:1–7 20. Bouza C, Lopez-Cuadrado T, Alcazar R, et al: Meta-analysis of

percutaneous radiofrequency ablation versus ethanol injection in hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC gastroenterology 2009;9:31–40

21. Orlando A, Leandro g, Olivo M, et al: Radiofrequency thermal

ablation vs percutaneous ethanol injection for small hepatocel-lular carcinoma: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.

Am J gastroenterol 2009;104:514–524

22. Livraghi T, Meloni F, Morabito A, et al: Multimodal image-

guided tailored therapy of early and intermediate hepatocel-lular carcinoma: long-term survival in the experience of a single radiologic referral center. Liver Transpl 2004;10:S98–106

23. geschwind JF, Ramsey DE, Choti MA, ym: Chemoemboliza-

tion of hepatocellular carcinoma: results of a meta-analysis.

Am J Clin Oncol 2003;26:344–349

24. Doffoel M, Bonnetain F, Bouch Vetter D, et al: Multicentre

randomised phase III trial comparing tamoxifen alone or with transarterial lipiodol chemoembolisation for unresectable he-patocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients. Eur J Cancer 2008;

44:528–538

25. Maluccio MA, Covey AM, porat LB, et al: Transcatheter arte-

rial embolization with only particles for the treatment of un-resectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2008;

19:862–869

26. Miyayama S, Mitsui T, Zen y, et al: Histopatological findings

after ultraselective transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res 2009;39:374–381 27. Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al: Sorafenib in advanced

hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2008;359:378–90 28. Llovet JM, Bruix J: Novel advancements in the management of

hepatocellular carcinoma in 2008. J Hepatol 2008;48(Suppl

1):S20–37

29. Kamiyama T, Nakanishi K, yokoo H, et al: perioperative man-

agement of hepatic resection toward zero mortality and mor-bidity: analysis of 793 consecutive cases in a single institution.

J Am Coll Surg 2010;211:443–449

30. poon RT, Fan ST, Lo CM, et al: Long-term prognosis after resec-

tion of hepatocellular carcinoma associated with hepatitis B-related cirrhosis. J Clin Oncol 2000;18:1094–1101

31. Llovet JM, Fuster J, Bruix J: Intention-to-treat analysis of surgi-

cal treatment for early hepatocellular carcinoma: resection versus transplantation. Hepatology 1999;30:1434–1440

32. Eguchi S, Kanematsu T, Arii S, et al: Comparison of the out-

comes between an anatomical subsegmentectomy and a non-anatomical minor hepatectomy for single hepatocellular carci-nomas based on a Japanese nationwide survey. Surgery 2008;

143:469–475

33. Kudo M: Real practice of hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan:

conclusions of the Japan Society of Hepatology 2009 Kobe Congress. Oncology 2010;78(Suppl 1):180–188

34. poon RT, Fan ST, Ng IO, et al: Different risk factors and prog-

nosis for early and late intrahepatic recurrence after resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer 2000;89:500–507

35. Toso C, Asthana S, Bigam DL, et al: Reassessing selection cri-

teria prior to liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma utilizing the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients data-base. Hepatology 2009;49:832–838

36. poon RpT, Fan ST, Ng IO, et al: Significance of resection margin

in hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma: a critical reap-praisal. Ann Surg 2000;231:544–551

37. Shi M, guo Rp, Lin XJ, et al: partial hepatectomy with wide

versus narrow resection margin for solitary hepatocellular car-cinoma: a prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg 2007;245:36–43

38. Kaibori M, Ishizaki M, Matsui K, et al: predictors of microvas-

cular invasion before hepatectomy for hepatocellular carci-noma. J Surg Oncol 2010;102:462–446

29 Treatment options in hepatocellular carcinoma today

39. Tanwar S, Khan SA, grover VpB, et al: Liver transplantation

for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J gastroenterol 2009;15: 5511–5516

40. McHugh pp, gilbert J, Vera S, et al: Alpha-fetoprotein and tu-

mour size are associated with microvascular invasion in ex-planted livers of patients undergoing transplantation with hepatocellular carcinoma. HpB (Oxford) 2010;12:56–61

41. Mazzaferro V, Llovet JM, Miceli R, et al: predicting survival

after liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular car-cinoma beyond the Milan criteria: a retrospective, exploratory analysis. Lancet Oncol 2008;10:35–43

42. Toso C, Trotter J, Wei A, et al: Total tumor volume predicts risk

of recurrence following liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl 2008;14:1107–1115 43. Nordic Liver Transplant Registry, Annual report 2009: http://

https://www.360docs.net/doc/942960833.html,/ANNUAL_REpORT_2009_FI-NAL.pdf

44. European Liver Transplant Registry: https://www.360docs.net/doc/942960833.html,/

45. Marsh JW, Schmidt C: The Milan criteria: no room on the met-

ro for the king? Liver Transpl 2010;16:252–255

46. Majno p, Mentha g, Toso C: Transplantation for hepatocellular

carcinoma: Management of patients on the waiting list. Liver Transpl 2010;16:S2–S11

47. Vakili K, pomposelli JJ, Cheah yL, et al: Living donor liver

transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: increased recur-rence but improved survival. Liver Transpl 2009;15:1861–1866

48. Toso C, Mentha g, Kneteman NM, et al: The place of down-

staging for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2010;52:930–93649. Otto g, Herber S, Heise M, et al: Response to transarterial

chemoembolization as a biological selection criterion for liver transplantation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl 2006;12:1260–1267

50. Lencioni R, Llovet JM: Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assess-

ment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis 2010;30:52–60

51. Toso C, Merani S, Bigam DL, et al: Sirolimus-based immuno-

suppression is associated with increased survival after liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2010;51:1237–1243

52. Schitzbauer AA, Zuelke C, graeb C, et al: A prospective ran-

domised, open-labeled, trial comparing sirolimus-containing versus mTOR-inhibitor-free immunosuppression in patients undergoing liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma.

BMC Cancer 2010;10:190

53. Shah SA, Cleary Sp, Tan JC, et al: An analysis of resection vs

transplantation for early hepatocellular carcinoma: defining the optimal therapy at a single institution. Ann Surg Oncol 2007;14:2608–2614

54. Chua TC, Saxena A, Chu F, et al: Clinicopathological determi-

nants of survival after hepatic resection of hepatocellular car-cinoma in 97 patients—experience from an Australian Hepa-tobiliary Unit. J gastrointest Surg 2010;14:1370–1380

55. Margarit C, Escartín A, Castells L, et al: Resection for hepato-

cellular carcinoma is a good option in Child-Turcotte-pugh class A patients with cirrhosis who are eligible for liver trans-plantation. Liver Transpl 2005;11:1242–1251 Received: December 15, 2010