Fly piRNAs, PIWI Proteins, and the Ping-Pong Cycle

S n a p S h o t : F l y p i R N A s , P I W I P r o t e i n s , a n d t h e

P i n g -P o n g C y c l e

J o g e n d e r S . T u s h i r , P h i l l i p D . Z a m o r e , a n d Z h a o Z h a n g H H M I a n d D e p a r t m e n t o f B i o c h e m i s t r y a n d M o l e c u l a r P h a r m a c o l o g y , U n i v e r s i t y o f M a s s a c h u s e t t s M e d i c a l S c h o o l , W o r c e s t e r , M A 01605, U S A 634 Cell 139, October 30, 2009 ?2009 Elsevier Inc.

See online version for legend and references.

ctober 30, 2009 ?2009 Elsevier Inc. DOI 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.021

SnapShot: Fly piRNAs, PIWI

Proteins, and the Ping-Pong Cycle

Jogender S. Tushir, Phillip D. Zamore, and Zhao Zhang

HHMI and Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Pharmacology, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA 01605, USA

In animals, PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) repress expression of transposons and other repetitive genomic sequences, ensuring faithful transmission of the genetic material from one generation to the next. These 23–30 nucleotide-long small RNAs are generally found in the germline. They bind to “PIWI” proteins, a specialized subclass of the Argo-naute protein family, whose members use small RNA guides to silence gene expression. In zebrafish and Drosophila, piRNAs are required for fertility in both males and females, and loss of piRNAs results in male sterility in mice.

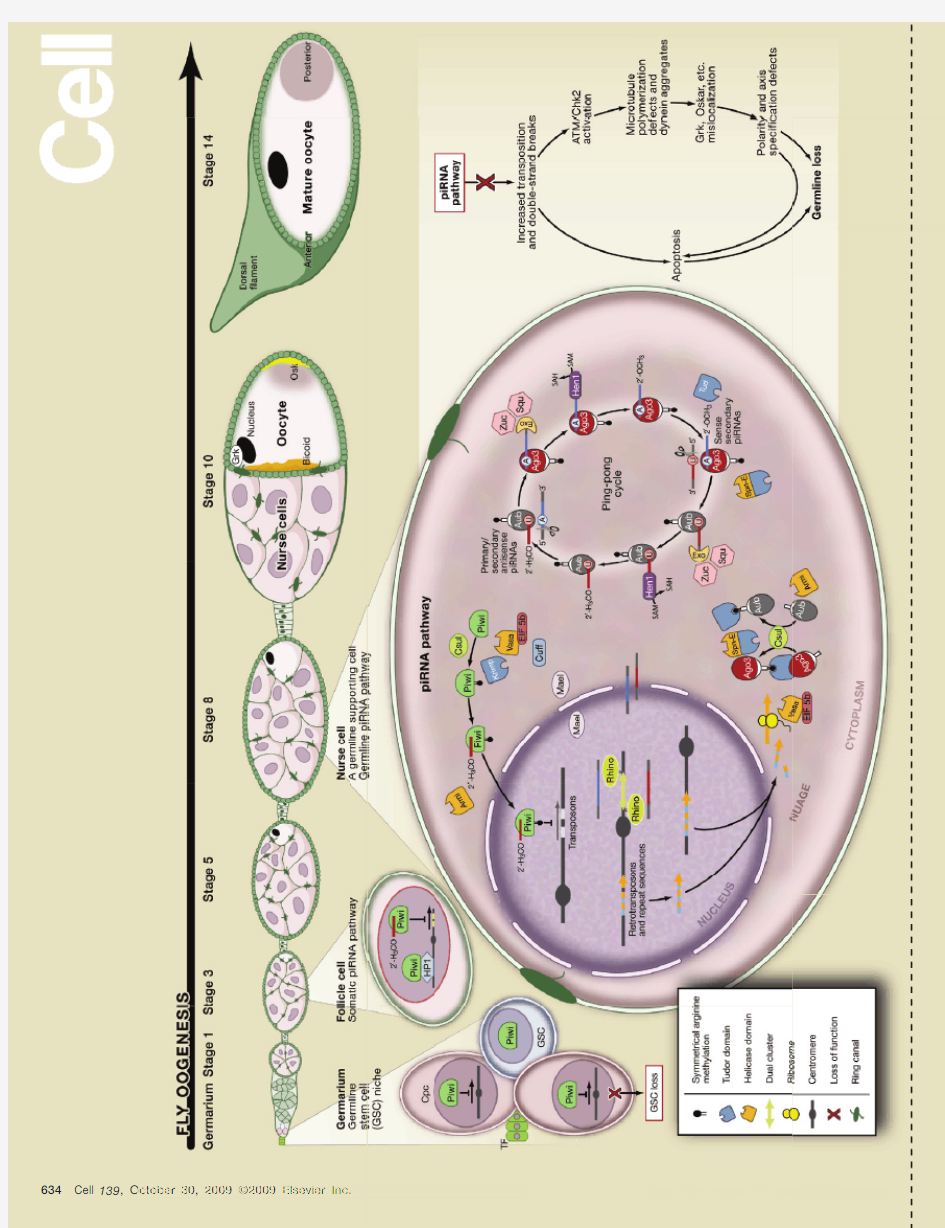

piRNAs in Fly Oogenesis

The three fly PIWI proteins—Piwi, Argonaute3 (Ago3), and Aubergine (Aub)—are expressed in both ovaries and testes. In ovaries, Piwi, which localizes to the nucleus, is found both in the germline and in two types of somatic cells: those that form the germline stem cell niche and the somatic follicle cells that surround the developing oocyte. Unlike Piwi, Ago3 and Aub reside in the nuage, a structure that rings the nucleus; Ago3 and Aub are restricted to the oocyte and its nurse cell sisters.

Drosophila piRNAs are produced in the nurse cells by a cycle of reciprocal, PIWI-protein catalyzed cleavage events that both amplify a small initial pool of primary piRNAs and bias the piRNA population toward antisense. This “ping-pong” cycle creates sense secondary piRNAs bound to Ago3. In turn, these sense piRNAs generate new antisense, Aub-bound piRNAs that can silence transposons and also create yet more sense piRNAs. It is not known if these events occur in the cytosol or the nuage.

Like other maternally deposited RNAs, piRNAs produced by ping-pong amplification are transported from the nurse cells to the oocyte via the ring canals, cytoplasmic bridges that link the 16 germline sister cells. Loss of piRNA pathway proteins such as Vasa, Aubergine, Spindle-E, Krimper, Armitage, Zucchini, Maelstrom—all of which are found in nuage—perturbs the embryonic axes. Remarkably, these polarity defects are a secondary consequence of activation of the double-stranded DNA break repair pathway, sug-gesting that piRNAs mainly function to block transposon mobilization in the oocyte.

In the somatic follicle cells, at least one source of piRNAs, the flamenco cluster, generates piRNAs directly and without ping-pong amplification. The unique organization of this locus ensures that nearly all of these piRNAs are antisense. How these piRNAs—which bind to Piwi rather than Aub or Ago3—are made is unknown.

Abbreviations

Cpc, cap cell; TF, terminal filament cell; GSC, germline stem cell; PIWI, P-element-induced wimpy testis; piRNA, PIWI-interacting RNAs; Mael, Maelstrom; eIF5b, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5b; HP1, heterochromatin protein 1; Rhino, a HP1 homolog; RTs, retrotransposons; Krimp, Krimper; Csul, Capsuleen; Hen1, Hua enhancer 1; Armi, Armitage; Aub, Aubergine; Ago3, Argonaute3; Spn-E, Spindle-E; Zuc, Zucchini; Squ, Squash; Cuff, Cutoff; Grk, Gurken; Osk, Oskar; SAM, S-adenosylmethionine; SAH, S-ade-nosylhomocysteine; Tud, Tudor protein; ATM, Ataxia-telangiectasia gene; Chk2, Checkpoint kinase 2; MT, microtubule.

RefeRences

Aravin, A.A., Naumova, N.M., Tulin, A.V., Vagin, V.V., Rozovsky, Y.M., and Gvozdev, V.A. (2001). Double-stranded RNA-mediated silencing of genomic tandem repeats and transpos-able elements in the D. melanogaster germline. Curr. Biol. 11, 1017–1027.

Brennecke, J., Malone, C.D., Aravin, A.A., Sachidanandam, R., Stark, A., and Hannon, G.J. (2008). An epigenetic role of maternally inherited piRNAs in transposon silencing. Science 322, 1387–1392.

Brennecke, J., Aravin, A.A., Stark, A., Dus, M., Kellis, M., Sachidanandam, R., and Hannon, G.J. (2007). Discrete small RNA-generating loci as master regulators of transposon activity in Drosophila. Cell 128, 1089–1103.

Gunawardane, L.S., Saito, K., Nishida, K.M., Miyoshi, K., Kawamura, Y., Nagami, T., Siomi, H., and Siomi, M.C. (2007). A slicer-mediated mechanism for repeat-associated siRNA 5′ end formation in Drosophila. Science 315, 1587–1590.

Kirino, Y., Kim, N., de Planell-Saguer, M., Khandros, E., Chiorean, S., Klein, P.S., Rigoutsos, I., Jongens, T.A., and Mourelatos, Z. (2009). Arginine methylation of Piwi proteins catalysed by dPRMT5 is required for Ago3 and Aub stability. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 652–658.

Klattenhoff, C., Xi, H., Li, C., Lee, S., Xu, J., Khurana, J.S., Schultz, N., Koppetsch, B.S., Nowosielska, A., Seitz, H., et al. (2009). The Drosophila HP1 homolog Rhino is required for transposon silencing and piRNA production by dual strand clusters. Cell 138, 1137–1149.

Li, C., Vagin, V.V., Lee, S., Xu, J., Ma, S., Xi, H., Seitz, H., Horwich, M.D., Syrzycka, M., Honda, B.M., et al. (2009). Collapse of germline piRNAs in the absence of Argonaute3 reveals somatic piRNAs in flies. Cell 137, 509–521.

Lim, A.K., Tao, L., and Kai, T. (2009). piRNAs mediate posttranscriptional retroelement silencing and localization to pi-bodies in the Drosophila germline. J. Cell Biol. 186, 333–342. Malone, C.D., Brennecke, J., Dus, M., Stark, A., McCombie, W.R., Sachidanandam, R., and Hannon, G.J. (2009). Specialized piRNA pathways act in germline and somatic tissues of the Drosophila ovary. Cell 137, 522–535.

Vagin, V.V., Sigova, A., Li, C., Seitz, H., Gvozdev, V., and Zamore, P.D. (2006). A distinct small RNA pathway silences selfish genetic elements in the germline. Science 313, 320–324.

634.e1Cell 139, October 30, 2009 ?2009 Elsevier Inc. DOI 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.021

上市公司重大资产重组管理办法 中英文

上市公司重大资产重组管理办法 Measures for the Administration of Material Asset Reorganization of Listed Companies 颁布机关:中国证券监督管理委员会 Promulgating Institution: China Securities Regulatory Commission 文号:中国证券监督管理委员会令第109号 Document Number: Order No.109 of the China Securities Regulatory Commission 颁布时间: Promulgating Date: 10/23/2014 10/23/2014 实施时间: Effective Date: 11/23/2014 11/23/2014 效力状态: Validity Status: 有效 Valid 第一章总则 Chapter 1: General Provisions 第一条为了规范上市公司重大资产重组行为,保护上市公司和投资者的合法权益,促进上市公司质量不断提高,维护证券市场秩序和社会公共利益,根据《公司法》、《证券法》等法律、行政法规的规定,制定本办法。 Article 1 These Measures are formulated pursuant to the provisions of the Company Law, the Securities Law and other relevant laws and administrative regulations, for the purposes of regulating material asset reorganization of listed companies, protecting the lawful rights and interests of listed companies and investors, and promoting the constant improvement of the quality of listed companies, and maintaining the order of the securities market and the social public interests. 第二条本办法适用于上市公司及其控股或者控制的公司在日常经营活动之外购买、出售资产或者通过其他方式进行资产交易达到规定的比例,导致上市公司的主营业务、资产、收入发生重大变化的资产交易行为(以下简称重大资产重组)。 Article 2 These Measures shall be applicable to asset trading behaviors, other than the daily business activities, conducted by a listed company or companies held or controlled by it, such as the purchase and sale of assets, or asset trading by other means that reach a specified proportion, thereby causing major changes to the main business, assets, or income of that listed company (hereinafter, "material asset reorganization"). 上市公司发行股份购买资产应当符合本办法的规定。 Purchase of assets by a listed company by means of issuing shares shall be in compliance with the provisions of these Measures.

企业重组【外文翻译】

外文翻译 Corporate Restructuring Material Source:https://www.360docs.net/doc/d46750567.html, Author:Giuliano Iannotta The Holdout Problem When claimants are unable to find an agreement, they might not approve the restructuring plan, even when this will produce a sub-optimal outcome, such as a liquidation (which will waste the value of the firm “as a going concern”) or a formal bankruptcy procedure (which is more expensive and possibly leads to inferior result for creditors): this is the holdout problem. The likelihood of approval of the restructuring plan will depend on several factors, such as the number and sophistication of the claimants, the relative cost of the plan relative to other solutions, etc. For example, in the presence of many small bondholders it might be very difficult to get the restructuring plan approved, as some of them might believe they will be better off not approving the proposed plan. In other terms, when there is public debt (i.e., bonds) outstanding the holdout problem can be particularly severe. Scale down, maturity extension, or debt-for-equity swap might be very difficult if every bondholder has to agree to the term changes. Consider for example an exchange offer where outstanding debt is exchanged with equity (debt-for-equity swap): in other words, creditors take over the distressed firm. In such a situation, the bondholders who do not tender might benefit at the expense of those who do. Suppose the firm’s asset value is $100, with public debt outstanding for$120 (10 bondholders, each holding one bond with face value $12). The firm’s asset liquidation value is only$80: there is therefore an incentive to keep the firm doing business. Suppose the exchange offer is contingent on achieving a 50% tendering rate. If all bondholders tender, the firm will have the balance sheet reported in Table 10.1. The value to each bondholder will be $10, with a loss of $2: under liquidation each bondholders would receive just $8. Now suppose that only five bondholders tender: the exchange offer would succeed, but the five “holdout” bondholders will be better off. Indeed, the balance sheet of the firm would be that reported in Table 10.2.

外文翻译----过渡和企业重组在预算的作用

Transition and enterprise restructuring the role of budget Abstract:The focus of analysis is on the impact of financial leverage as a measure of bankruptcy costs on enterprise restructuring, based on budget constraints in the economy. Data of Bulgarian manufacturing firms allow comparison of firm behavior under soft and hard budget constraints as distinguished by the inception of a currency board in 1997. Controlling for change in sales, firm size and type of ownership, statistically significant relationship between financial leverage and firm restructuring through labor adjustments is found to exist under hard budget. 1 Introduction The impact of budget constraints on firm behavior in transition economies has been recognized in a number of studies where elimination of labor hording is identified as an important component of enterprise-restructuring policies (e.g., Grosfeld and Roland, 1996; Coricelli and Djankov, 2001). A large theoretical and empirical literature, summarized in Kornai et al. (2003), has identified the causes and channels of soft budget constraints (SBC). However, the effects of the heavy indebtedness resulting from SBC in transition economies and the influence of corporate capital structure on firm restructuring and economic efficiency have not been fully explored. In the finance literature, research has long been focused on how financial leverage and bankruptcy costs influence operating behavior and efficiency (e.g., Titman, 1984; Perotti and Spier, 1993; Sharpe, 1994; Rajan and Zingales, 1995). The main finding is that higher levels of debt in the capital structure discipline firms and force them to make optimal resource allocation decisions. This paper analyzes the impact of financial leverage on firm restructuring, based on budget constraints in the economy. The analysis explores an important channel through which the hardening of budget constraints is expected to cause active labor adjustment and enterprise restructuring. The empirical analysis uses data on more than 1500 Bulgarian manufacturing firms over the period 1994–2000. During the first half of the period, SBC were widespread and combined with inconsistent economic policies led to a severe financial crisis, which was followed by the inception of a currency board in mid-1997 and significant hardening of the budget constraints. Thus, data allow us to compare firm behavior under soft and hard budget constraints. Under hard budget constraints, a statistically significant relationship is found between determinants of the level of bankruptcy costs, such as firm size and financial leverage, and restructuring through labor adjustments. Ceteris paribus, the elimination of excess labor is more substantial in smaller and more highly leveraged firms. This relationship is not present under SBC. 2 Analytical framework and hypotheses The costs of adjusting firm labor force arise through the costs of hiring, training and firing employees, or the quasi-fixed components of the labor input (Oi, 1962; Fay and