Phytoplankton–bacterial interactions mediate-2015

Phytoplankton–bacterial interactions mediate micronutrient colimitation at the coastal

Antarctic sea ice edge

Erin M.Bertrand a,b,1,John P.McCrow a,Ahmed Moustafa a,b,c,Hong Zheng a,Jeffrey B.McQuaid a,b,Tom O.Delmont d, Anton F.Post e,Rachel E.Sipler f,Jenna L.Spackeen f,Kai Xu g,Deborah A.Bronk f,David A.Hutchins g,

and Andrew E.Allen a,b,2

a Microbial and Environmental Genomics,J.Craig Venter Institute,La Jolla,CA92037;

b Integrative Oceanography Division,Scripps Institution of Oceanography,University of California,San Diego,La Jolla,CA92037;

c Department of Biology an

d Biotechnology Graduat

e Program,American University in Cairo,Cairo,Egypt11835;d Josephine Bay Paul Center,Marine Biological Laboratory,Woods Hole,MA02543;e Graduate School o

f Oceanography, University of Rhode Island,Narragansett,RI02882;f Department of Physical Sciences,Virginia Institute of Marine Science,Gloucester Point,VA23062;and

g Marine and Environmental Biology,Department of Biological Sciences,University of Southern California,Los Angeles,CA90089

Edited by David M.Karl,University of Hawaii,Honolulu,HI,and approved July2,2015(received for review January25,2015)

Southern Ocean primary productivity plays a key role in global ocean biogeochemistry and climate.At the Southern Ocean sea ice edge in coastal McMurdo Sound,we observed simultaneous cobalamin and iron limitation of surface water phytoplankton communities in late Austral summer.Cobalamin is produced only by bacteria and archaea,suggesting phytoplankton–bacterial in-teractions must play a role in this limitation.To characterize these interactions and investigate the molecular basis of multiple nutri-ent limitation,we examined transitions in global gene expression over short time scales,induced by shifts in micronutrient availabil-ity.Diatoms,the dominant primary producers,exhibited transcrip-tional patterns indicative of co-occurring iron and cobalamin deprivation.The major contributor to cobalamin biosynthesis gene expression was a gammaproteobacterial population,Oceanospir-illaceae ASP10-02a.This group also contributed significantly to metagenomic cobalamin biosynthesis gene abundance through-out Southern Ocean surface waters.Oceanospirillaceae ASP10-02a displayed elevated expression of organic matter acquisition and cell surface attachment-related genes,consistent with a mu-tualistic relationship in which they are dependent on phytoplankton growth to fuel cobalamin production.Separate bacterial groups, including Methylophaga,appeared to rely on phytoplankton for carbon and energy sources,but displayed gene expression patterns consistent with iron and cobalamin deprivation.This suggests they also compete with phytoplankton and are important cobalamin consumers.Expression patterns of siderophore-related genes of-fer evidence for bacterial influences on iron availability as well. The nature and degree of this episodic colimitation appear to be mediated by a series of phytoplankton–bacterial interactions in both positive and negative feedback loops. colimitation|Southern Ocean primary productivity|metatranscriptomics| phytoplankton–bacterial interactions|cobalamin

P rimary productivity and community composition in the South-ern Ocean play key roles in global change(1,2).The coastal Southern Ocean,particularly its shelf and marginal ice zones,is highly productive,with mean rates approaching300–450mg C m?2·d?1(3). As such,identifying factors controlling phytoplankton growth in these regions is essential for understanding the ocean’s role in past,present,and future biogeochemical cycles.Although irra-diance,temperature,and iron availability are often considered to be the primary drivers of Southern Ocean productivity(1,4), cobalamin(vitamin B12)availability has also been shown to play a role(5,6).Cobalamin is produced only by select bacteria and archaea and is required by most eukaryotic phytoplankton,as well as many bacteria that do not produce the vitamin(7).Co-balamin is used for a range of functions,including methio-nine biosynthesis and one-carbon metabolism.Importantly,phytoplankton that are able to grow without cobalamin prefer-entially use it when available;growth without the vitamin occurs at a metabolic cost via use of an alternative methionine synthase enzyme(MetE),rather than the more efficient,cobalamin-requiring version(MetH)(8).The presence of metE in phytoplankton ge-nomes does not follow phylogenetic or obvious biogeographical lines;for instance,there are examples of both coastal and open ocean diatoms that require B12absolutely,and some that use it facultatively(7).

Given the short residence time of the vitamin in productive, sunlit surface waters(on the order of hours to days;SI Appendix), it is likely that locally produced cobalamin is a predominant source of the vitamin to phytoplankton.Thaumarchaeota and cyanobacteria are hypothesized to be major contributors to oceanic cobalamin biosynthesis(9,10).In the coastal

Antarctic

Author contributions:E.M.B.and A.E.A.designed research;E.M.B.,H.Z.,J.B.M.,R.E.S.,J.L.S., K.X.,D.A.B.,and D.A.H.performed research;T.O.D.and A.F.P.contributed new reagents/ analytic tools;E.M.B.,J.P.M.,and A.M.analyzed data;and E.M.B.,J.P.M.,and A.E.A.wrote the paper.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Freely available online through the PNAS open access option.

Data deposition:The data reported in this paper have been deposited in the NCBI se-quence read archive(BioProject accession no.PRJNA281813;BioSample accession nos. SAMN03565520–SAMN03565531).Assembled contigs,predicted peptides,annotation,and transcript abundance data for this study can be found at https://https://www.360docs.net/doc/f35591546.html,/labs/ aallen/data/.

1Present address:Department of Biology,Dalhousie University,Halifax NS,Canada B3H4R2. 2To whom correspondence should be addressed.Email:aallen@https://www.360docs.net/doc/f35591546.html,.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.360docs.net/doc/f35591546.html,/lookup/suppl/doi:10. 1073/pnas.1501615112/-/DCSupplemental.

9938–9943|PNAS|August11,2015|vol.112|https://www.360docs.net/doc/f35591546.html,/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1501615112

Southern Ocean,cyanobacteria are scarce (11),and Thau-marchaeota appear to be important,in terms of abundance and contribution to cobalamin biosynthesis proteins,only in winter and springtime (12,13).Although seasonal trends in Southern Ocean cobalamin concentrations have yet to be investigated,these biogeographic data suggest that Austral summer Southern Ocean cobalamin production may be low relative to other sea-sons and locations.Indeed,cobalamin limitation has been ob-served in mid to late summer in the Ross Sea,but was absent in springtime (14).This leads to the hypothesis that reduced co-balamin supply in summer,along with enhanced demand by blooming diatoms,results in possible cobalamin limitation or cobalamin and iron colimitation of primary production.Despite hints that the microbial source of cobalamin during this sum-mertime period may be gammaproteobacterial (15),it has re-mained uncharacterized to date,rendering inquiry into interactions between microbial sources and sinks of the vitamin difficult.Although instances of mutualistic cobalamin-based interactions between bacteria and algal laboratory cultures have been iden-tified (16),little is known about microbial dynamics surrounding cobalamin production and exchange in the field.

Within McMurdo Sound,which connects the Ross Sea of the Southern Ocean with the McMurdo ice shelf,primary pro-duction rates can reach upward of 2gC m ?2·d ?1,with most an-nual production occurring between December and January (17).Because this area is highly influenced by coastal processes,it has generally been assumed that productivity in the region is not iron-limited (4).However,we show here that at the sea ice edge,

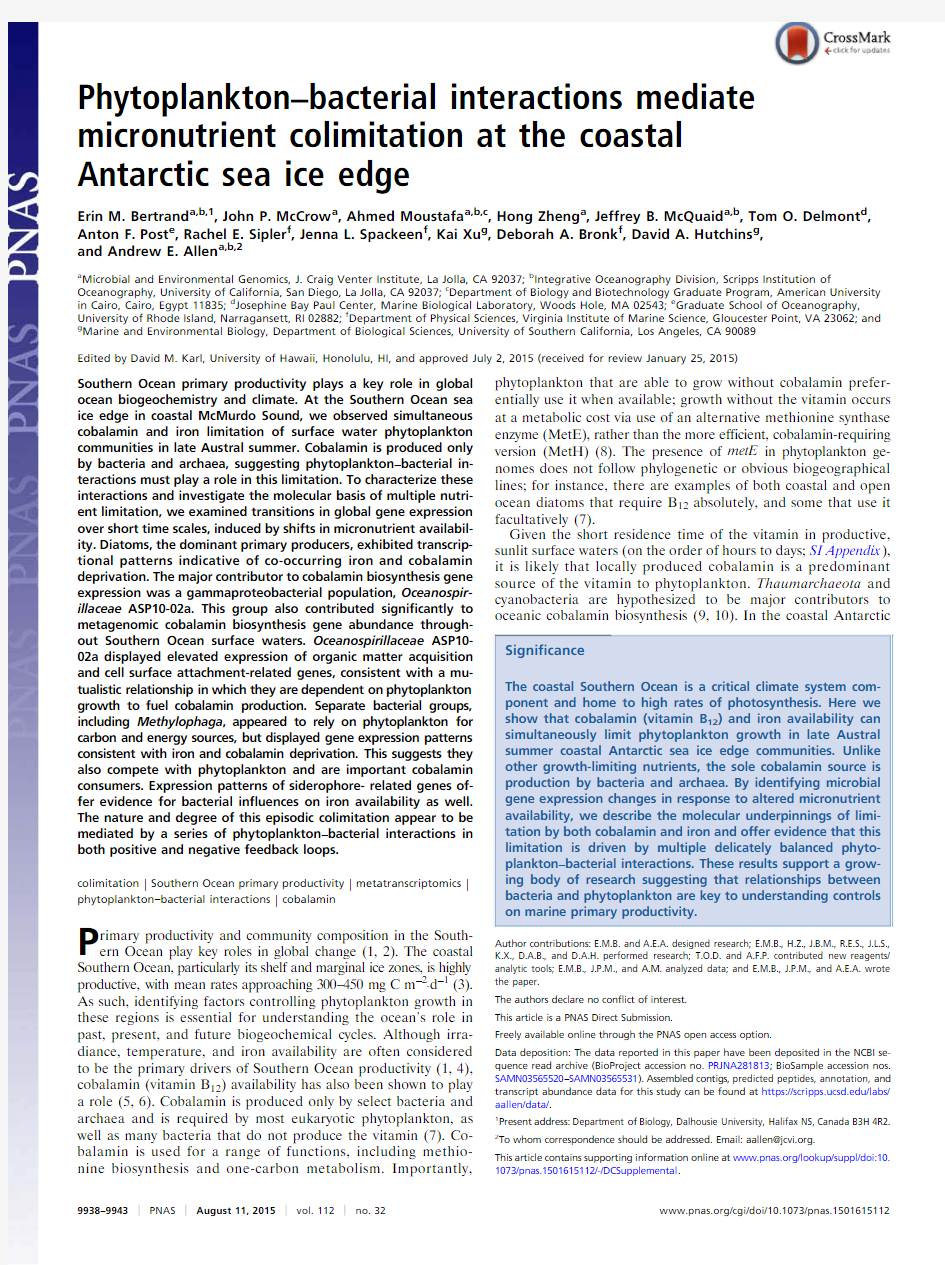

McMurdo Sound primary production was both iron-and co-balamin-limited in mid-January 2013,as well as 2015(Fig.1;SI Appendix ,Fig.S1).By examining co-occurring changes in bac-terial and phytoplankton transcriptional profiles in response to micronutrient manipulation during this colimited period,we identify specific bacterial and phytoplankton processes that contribute to cobalamin limitation and its relationship to iron dynamics in this key marine region.

Results and Discussion

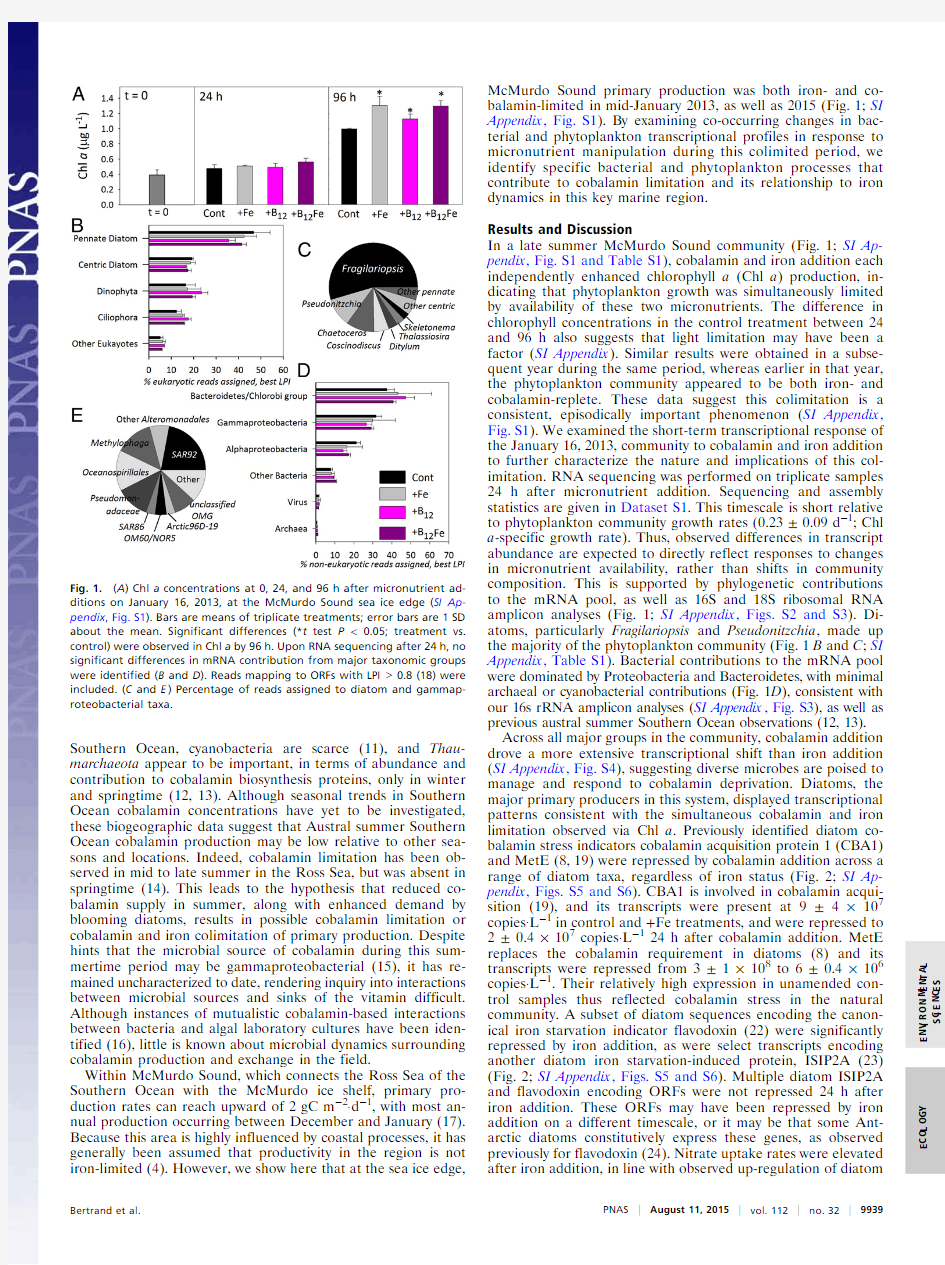

In a late summer McMurdo Sound community (Fig.1;SI Ap-pendix ,Fig.S1and Table S1),cobalamin and iron addition each independently enhanced chlorophyll a (Chl a )production,in-dicating that phytoplankton growth was simultaneously limited by availability of these two micronutrients.The difference in chlorophyll concentrations in the control treatment between 24and 96h also suggests that light limitation may have been a factor (SI Appendix ).Similar results were obtained in a subse-quent year during the same period,whereas earlier in that year,the phytoplankton community appeared to be both iron-and cobalamin-replete.These data suggest this colimitation is a consistent,episodically important phenomenon (SI Appendix ,Fig.S1).We examined the short-term transcriptional response of the January 16,2013,community to cobalamin and iron addition to further characterize the nature and implications of this col-imitation.RNA sequencing was performed on triplicate samples 24h after micronutrient addition.Sequencing and assembly statistics are given in Dataset S1.This timescale is short relative to phytoplankton community growth rates (0.23±0.09d ?1;Chl a -specific growth rate).Thus,observed differences in transcript abundance are expected to directly reflect responses to changes in micronutrient availability,rather than shifts in community composition.This is supported by phylogenetic contributions to the mRNA pool,as well as 16S and 18S ribosomal RNA amplicon analyses (Fig.1;SI Appendix ,Figs.S2and S3).Di-atoms,particularly Fragilariopsis and Pseudonitzchia ,made up the majority of the phytoplankton community (Fig.1B and C ;SI Appendix ,Table S1).Bacterial contributions to the mRNA pool were dominated by Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes,with minimal archaeal or cyanobacterial contributions (Fig.1D ),consistent with our 16s rRNA amplicon analyses (SI Appendix ,Fig.S3),as well as previous austral summer Southern Ocean observations (12,13).Across all major groups in the community,cobalamin addition drove a more extensive transcriptional shift than iron addition (SI Appendix ,Fig.S4),suggesting diverse microbes are poised to manage and respond to cobalamin deprivation.Diatoms,the major primary producers in this system,displayed transcriptional patterns consistent with the simultaneous cobalamin and iron limitation observed via Chl a .Previously identified diatom co-balamin stress indicators cobalamin acquisition protein 1(CBA1)and MetE (8,19)were repressed by cobalamin addition across a range of diatom taxa,regardless of iron status (Fig.2;SI Ap-pendix ,Figs.S5and S6).CBA1is involved in cobalamin acqui-sition (19),and its transcripts were present at 9±4×107copies ·L ?1in control and +Fe treatments,and were repressed to 2±0.4×107copies ·L ?124h after cobalamin addition.MetE replaces the cobalamin requirement in diatoms (8)and its transcripts were repressed from 3±1×108to 6±0.4×106copies ·L ?1.Their relatively high expression in unamended con-trol samples thus reflected cobalamin stress in the natural community.A subset of diatom sequences encoding the canon-ical iron starvation indicator flavodoxin (22)were significantly repressed by iron addition,as were select transcripts encoding another diatom iron starvation-induced protein,ISIP2A (23)(Fig.2;SI Appendix ,Figs.S5and S6).Multiple diatom ISIP2A and flavodoxin encoding ORFs were not repressed 24h after iron addition.These ORFs may have been repressed by iron addition on a different timescale,or it may be that some Ant-arctic diatoms constitutively express these genes,as observed previously for flavodoxin (24).Nitrate uptake rates were elevated after iron addition,in line with observed up-regulation of

diatom

Fig.1.(A )Chl a concentrations at 0,24,and 96h after micronutrient ad-ditions on January 16,2013,at the McMurdo Sound sea ice edge (SI Ap-pendix ,Fig.S1).Bars are means of triplicate treatments;error bars are 1SD about the mean.Significant differences (*t test P <0.05;treatment vs.control)were observed in Chl a by 96h.Upon RNA sequencing after 24h,no significant differences in mRNA contribution from major taxonomic groups were identified (B and D ).Reads mapping to ORFs with LPI >0.8(18)were included.(C and E )Percentage of reads assigned to diatom and gammap-roteobacterial taxa.

Bertrand et al.

PNAS |August 11,2015|vol.112|no.32|9939

E C O L O G Y

E N V I R O N M E N T A L S C I E N C E S

genes encoding nitrate transporters (SI Appendix ,Fig.S7).No-tably,alleviation of iron limitation was not required for this community to display signs of cobalamin stress,and vice versa,supporting the conclusion that these nutrients simultaneously limited community growth.Although it is possible that this re-sponse,along with the observed chlorophyll production pattern,could be produced if different groups within the primary pro-ducer community were limited by iron and others by cobalamin,a dominant diatom species in this experiment (Fragilariopsis cylindrus )was simultaneously iron-and cobalamin-deprived.CBA1,MetE,and ISIP2A sequences that showed >99–95%iden-tity (blastp)to this genome were repressed by cobalamin and iron additions,respectively (Table 1).These observations support a model for colimitation whereby growth can be reduced as a result of deprivation of two nutrients simultaneously (25).Certain types of colimitation,such as biochemical substitution or dependent limi-tation (25),do not have known molecular mechanisms pertaining to iron and cobalamin in eukaryotic phytoplankton.Rather,diatom cobalamin use appears to be largely independent of iron demand

and use (8),suggesting this is an instance of independent col-imitation (25).

Given that cobalamin is produced only by bacteria and archaea,a full understanding of cobalamin colimitation in phytoplankton requires interrogation of these communities as well.Through combining these transcriptome data with a genome sequence obtained from the assembly of metagenomic data recovered from another Southern Ocean surface water community,we identify the Oceanospirillaceae ASP10-02a population as the dominant source of transcriptional capacity for cobalamin bio-synthesis,contributing more than 70%of cobalamin biosynthesis-associated reads in this experiment (Fig.3;Dataset S2).We also suggest this group is a key contributor to cobalamin biosynthesis throughout Austral summer surface waters of the Southern Ocean,as it contributes the majority of cbiA/cobB (cobyrinic acid a,c-diamide synthase)metagenomic sequences from a range of Southern Ocean locations in that season,when Thaumarchaea and SAR324contributions are low (SI Appendix ,Fig.S8).Oce-anospirillaceae ASP10-02a also contributes a majority of CobU (adenosylcobinamide kinase)-encoding sequences in Southern Ocean metagenomes (SI Appendix ,Fig.S8).In addition,Oce-anospirillaceae ASP10-02a CbiA-derived peptides were previously detected in the Ross Sea [identified as Group RSB12(15);SI Appendix ,Fig.S9].The assembled Oceanospirillaceae ASP10-02a genome also recruited nearly 20%of all bacterial-assigned reads from this experiment,suggesting it is an important contributor to this community (Fig.3;Dataset S3).High expression levels of a diverse suite of organic compound acquisition genes,possible cell surface attachment-related genes (26),and photoheterotrophy genes were detected and attributed to Oceanospirillaceae ASP10-02a (SI Appendix ,Fig.S10).This key cobalamin producer may thus have been directly associated with phytoplankton cells and acquiring a wide range of phytoplankton-derived organic compounds as growth substrates,suggesting a mutualistic relationship.

Notably,Oceanospirillaceae ASP10-02a-attributed cobalamin biosynthesis pathway genes did not show differential expression upon vitamin addition.However,in other bacteria,genes at-tributed to the final steps in the pathway (e.g.,cobU )were re-pressed by cobalamin addition (Fig.3;Dataset S2).This latter part of the pathway can be referred to as the salvage and repair portion and is present in many bacterial genomes that do not encode the entire biosynthesis pathway (27).Although Ocean-ospirillaceae ASP10-2a contributed the majority of cobU reads,one ORF,most similar to a different gammaproteobacterial se-quence,contributed nearly 10%of cobU reads and was signifi-cantly repressed by cobalamin addition (Fig.3).This suggests that during this late Austral summer experiment,a subset of bacterial groups repressed cobalamin salvage under conditions of sufficient vitamin availability;increased cobalamin concen-trations appear to have resulted in reduced repair and reuse.Sequences most similar to this cobalamin-repressed cobU ORF are also highly represented in Southern Ocean metagenomics datasets in the Austral summer (SI Appendix ,Fig.S8;gamma-proteobacterium HTCC2134),suggesting repression of salvage and repair may be a widespread phenomenon.

Bacteria and archaea can also be important cobalamin con-sumers.Previous studies in the Ross Sea and other coastal ma-rine locations suggest bacteria are able to assimilate as much

R : l o g 2(+B 12/c o n t r o l )

10

5

-5

-10

10

15

20

5

A: log 2(+B 12)+log 2(control)

R : l o g 2(+F e /c o n t r o l )

10

5

-5

-10

10

15

20

5

A: log 2(+Fe)+log 2(control)

CBA1CBA1MetE

Helicase TF

MTRR

SHMT LHC

UAF

Cons. hyp.

Kinase

ISIP1

Cons. hyp.

ISIP3

ISIP2A

FLA LHC

Cons. hyp.

Cell surf prot.

protease

A B

Fig.2.Differential transcript abundance patterns in diatoms 24h after micronutrient addition,comparing cobalamin addition versus control (A )and iron addition versus control (B )(20).Each pie represents a cluster of diatom ORFs identified using MCL (21).LPI-based phylogenies of clusters,including the top six most abundant diatom genera,are shown.Consensus annotations for clusters of interest are given.Cons.hyp,conserved hypo-thetical protein;flavodoxin,clade II flavodoxin;Helicase TF,helicase-like transcription factor;ISIP1,2A,3,iron starvation-induced proteins 1,2A,and 3;LHC,light-harvesting complex-associated proteins;FBA,fructose bisphosphate aldolase;MetE,cobalamin-independent methionine synthase;MTRR,methio-nine synthase reductase;SHMT,serine hydroxymethyltransferase;UAF,RNA polymerase I upstream activation factor.

Table 1. F.cylindrus was simultaneously cobalamin-and iron-stressed ORF

Protein Blast hit %ID

FDR Fe FDR B 12262323_522_1007+CBA19510.06231834_1_471+MetE 9910.005128213_185_1513?

ISIP2A

99

0.01

0.4

ORFs shown encode proteins with 95–99%identity (ID)to F.cylindrus sequences.FDR (false discovery rate)for differential expression in pairwise comparisons versus the control were calculated via edgeR.

9940|https://www.360docs.net/doc/f35591546.html,/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1501615112

Bertrand et al.

cobalamin as phytoplankton(14,28).We identified four se-quences encoding the bacterial cobalamin uptake protein BtuB in this study(Fig.3).One of two highly expressed BtuB-encoding genes is most similar to those from Methylophaga.Methylophaga also contributed significantly to the total bacterial portion of the metatranscriptomes analyzed here,suggesting it may be a quanti-tatively important cobalamin consumer in this study(Fig.3, Dataset S4).This group has previously been detected in other areas of the coastal Southern Ocean and across a range of ad-ditional marine locales(29–31).Characterized members of this group do not produce cobalamin(32–34),but contribute signif-icantly to both methanol and dimethylsulfide consumption in the surface ocean(30,31).Methylophaga displayed signatures of iron and cobalamin deprivation,with repressed cobalamin uptake functions upon cobalamin addition,and repressed iron complex uptake and elevated iron storage transcripts after iron addition (Fig.4).In addition to signs of micronutrient deprivation,the Methylophaga group strongly expressed genes for methanol and other one-carbon compound use.These include quinoprotein methanol dehydrogenase,the enzyme required for conversion of methanol to formaldehyde,which is the initial step in assimila-tory and dissimilatory methanol use(Fig.4).Importantly,as methanol is a ubiquitous,abundant phytoplankton waste product (35),this gammaproteobacterial group also couples methanol production via phytoplankton growth to competition for co-balamin and iron.

Strong iron binding ligand production by bacteria has long been thought to play a role in enhancing iron bioavailability in the ocean(e.g.,ref.36).Here,we document repression of genes encoding siderophore uptake proteins upon iron addition,sup-porting the notion that siderophores are a source of iron to bacteria under iron limited conditions(Dataset S5).In addition, we document significant induction of possible bacterial side-rophore biosynthesis genes upon iron addition(nonribosomal peptide biosynthesis;Dataset S5).Although counter to the ca-nonical negative Fur regulation of siderophore production,this induction is consistent with results from iron fertilization

studies,

A B

C

Fig.3.Oceanospirillaceae ASP10-02a contributes the majority of cobalamin

biosynthesis transcripts,and Methylophaga is an important contributor to

cobalamin uptake gene expression.All ORFs attributed to cobalamin bio-

synthesis gene cbiA/cobB,cobalamin salvage,and repair gene cobU and

cobalamin uptake gene btuB are shown with mean expression values in each

of four treatments(A and B).Those significantly(edgeR FDR<0.05)dif-

ferentially expressed upon B12addition are denoted with an asterisk.Best

blast hit and percentage identity for each ORF is given.A subset of co-

balamin salvage(cobU)and uptake(btuB)genes are repressed upon co-

balamin addition,whereas de novo synthesis does not appear to be

regulated by B12availability on this timescale.Overall Methylophaga and

Oceanospirillaceae ASP10-02a contributions to these transcriptomes and to

cbiA,cobU,and btuB expression are shown in C.Fraction of Methylophaga-

assigned(LPI>0.8)reads and the fraction of reads mapping to the Ocean-

ospirillaceae ASP10-2a genome(>99%identity)are shown as a percentage

of total assigned bacterial-assigned(LPI>0.8)reads.Percentage of cbiA,

cobU,and btuB reads that we assigned to Methylophaga and Ocean-

ospirillaceae ASP10-02a are also shown.

Fig.4.Abundant ORFs assigned to Methylophaga and their possible con-

nections to cobalamin and Fe responsive ORFs.Functions shown are those

assigned to the10most abundant Methylophaga-assigned ORFs,other

genes in the ribulose monophosphate pathway(RuMP),and select ORFs

that were significantly differentially expressed between Fe or cobalamin

treatments versus control.Genes encoding putative methanol de-

hydrogenase(1),formaldehyde-activating enzyme(2),and key enzymes

in the RuMP pathway(3,4)are among the most abundant Methylophaga

transcripts.Multiple ORFs containing di-iron monooxygenase domains

(7),as well as possible hydrophobic compound transporter domains(8),

are also highly expressed.These could be involved in acquisition and

metabolism of additional substrates.Functions with significantly differ-

ently expressed ORFs are highlighted in black(FDR<0.05control vs.+Fe)

and purple(FDR<0.05control vs.+B12)outlines and denoted with an

asterisk.Among those ORFs repressed upon B12addition are those encoding

putative B12acquisition functions(11,12).Those significantly repressed by

iron addition include FecA domain ORFs(9),likely involved in iron com-

plex uptake.ORFs induced by iron include iron storage bacterioferritin

domains(10).B12quotas were possibly related to formaldehyde metab-

olism,as methionine synthase(MetH)(11)is required for regeneration of

methylation capacity.Iron was possibly involved in formaldehyde dis-

similation via a variety of ferridoxin-type oxidoreductases.Black arrows

represent direct,known metabolic connections.Black dashed arrows

represent known connections via multiple steps.Gray arrows represent

hypothesized connections.

Bertrand et al.PNAS|August11,2015|vol.112|no.32|9941

E

C

O

L

O

G

Y

E

N

V

I

R

O

N

M

E

N

T

A

L

S

C

I

E

N

C

E

S

which have shown that iron additions may stimulate production of strong iron binding ligands in the ocean(36,37).

A series of feedback loops driven by phytoplankton-bacterial interactions thus appear to govern coupling of cobalamin and iron dynamics in this late Austral summer system(Fig.5).When iron is added to the system,for instance,as a result of pulsed aeolian input or melting sea ice,this will stimulate iron-limited phytoplankton growth.Availability of such iron may be enhanced as a result of bacterial ligand production,which is stimulated both by iron addition via a regulated response and,in a positive feedback loop,enhanced availability of phytoplankton-derived organic matter.Elevated phytoplankton-derived organic matter availability to bacteria is expected upon alleviation of iron limi-tation(38,39).In another positive feedback loop,cobalamin production increases,also as a result of this enhanced organic matter availability,providing a mechanism for further increasing phytoplankton growth.This may be counterbalanced by negative feedback loops in which phytoplankton and bacterial demand for cobalamin increase while bacterial salvage and repair of degraded cobalamin is reduced in response to increases in cobalamin supply(Figs.3and5).

In this experiment,cobalamin and iron addition alone each stimulated production,but together did not enhance Chl a be-yond the level of iron addition alone[described as subadditive-independent colimitation(40)].This suggests that,by96h,in situ cobalamin production may have been enhanced by iron addition, and a manipulative cobalamin addition was not required to generate cobalamin-replete conditions(Fig.1;SI Appendix,Fig. S1).This interpretation suggests the positive feedback loop(Fig.

5)may have dominated.Alternatively,it is possible that another nutrient may have become limiting(e.g.,manganese),preventing an additive effect.In contrast,previous summertime observations in the Ross Sea(5)documented a condition in which simultaneous cobalamin and iron addition stimulated substantial additional growth beyond iron addition alone[serial limitation(40)].In this instance,it appears that the negative feedback loops offset the positive,and upon iron addition,cobalamin demand was stim-ulated beyond production.Each of these types of colimitation (subadditive independent and serial)have been observed re-peatedly in marine,terrestrial,and freshwater systems for major nutrients(40).The results described here offer potential mecha-nisms that underpin microbial interactions and possibly drive this system into one type of colimitation over another.In addition, the potential light limitation observed here(Fig.1)could also interact with the described colimitation,for instance,by altering abiotic cobalamin degradation rates or influencing iron quotas, and warrants further investigation in future efforts.

Future work is also required to understand relative rates of the processes identified here,as well as controls on when and where the positive or negative feedback loops described prevail.How-ever,mechanisms by which bacterial community composition could substantially influence the net balance are apparent.It is also likely,given the highly seasonal nature of Southern Ocean microbial communities(12),that other important interactions may be at play during different times of year.It is clear,however, that late summer phytoplankton growth in this productive region is synergistically influenced by the availability of cobalamin and iron,which appears to be largely regulated by the interactions described here.We propose the term“interactive colimitation”to describe such scenarios,in which multiple limiting nutrient cycles are affected by one another through interactions among different microbial functional groups.This example of interac-tive colimitation was identified because of our relatively exten-sive understanding of the molecular mechanisms governing acquisition and management of these micronutrients.As studies of mutualism and competition between microbial groups ad-vance,we anticipate that additional instances of such interactive colimitation may be identified as important drivers of marine biogeochemical

processes.C

B

A

E

D

Fig.5.A series of feedback loops,driven by phytoplankton and bacterial dynamics,appears to control interactivity of cobalamin and iron.These feedback loops are described here as responses to pulsed iron input.Molecular support for feedback loops is shown(A)in the heat map of relative expression levels (log10)of diatom CBA1,MetE,clade2flavodoxin,and ISIP2A transcripts.Bacterial gene expression patterns supporting these feedback loops include(B) Methylophaga sp.methanol consumption(methanol dehydrogenase and key ribulose monophosphate pathway enzymes)and iron and cobalamin depri-vation[iron acquisition(FecA),iron storage(bacterioferritin),and cobalamin uptake(BtuB)]-related genes(C).Highly expressed Oceanospirillaceae ASP10-02a (D)organic matter transport and binding functions and possible adhesion functions(HecA family),as well as cobalamin biosynthesis,also support this model. Siderophore-related genes that were influenced(significant;FDR<0.05)by iron are shown,highlighting induction of possible Bacteriodetes-associated nonribosomal peptide synthase genes by iron addition(E)and repression of various proteobacterial Fe-complex uptake-related genes(details provided in Dataset S5).

9942|https://www.360docs.net/doc/f35591546.html,/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1501615112Bertrand et al.

Materials and Methods

On January16,2013,seawater was collected from3m depth at the sea ice edge in McMurdo Sound of the Ross Sea(77°36.999′S165°28.464′E),using trace metal clean technique.Triplicate bottles(2.7L)of each treatment(unamended control,+1nM added FeCl3,+200pM added cyanocobalamin,and+200pM cyanocobalamin and1nM Fe)were placed in an indoor incubator at0°C,~45μmol photons m?2·s?1of constant light.After24h,RNA samples were collected (450mL)and nitrate uptake and primary productivity rates were measured. Samples were taken for Chl a at0,24,and96h.RNA was extracted using the TRIzol reagent(Life Technologies).Ribosomal RNA was removed with Ribo-Zero Magnetic kits,and the resulting mRNA enrichment was purified and subjected to amplification and cDNA synthesis,using the Ovation RNA-Seq System V2 (NuGEN).One microgram of the resulting high-quality cDNA pool was frag-mented to a mean length of200bp,and Truseq(Illumina)libraries were pre-pared and subjected to paired-end sequencing via Illumina HiSeq.Reads were trimmed and filtered,contigs were assembled in CLC Assembly Cell(CLCbio), and ORFs were predicted(41).ORFs were annotated de novo for function via KEGG,KO,KOG,Pfam,and TigrFam assignments.Taxonomic classification was assigned to each ORF using a reference dataset,as described in the SI Appendix, and the Lineage Probability Index(LPI,as calculated in ref.18).edgeR was used to assign normalized fold change and determine which ORFs were significantly differentially expressed in pairwise comparisons between treatments,consid-ering triplicates,within a given phylogenetic grouping(42).For Fig.2,diatom ORFs[identified as diatom via LPI analyses;LPI>0.8(18)]were clustered using MCL(Markov cluster algorithm)(21),and these clusters were used to produce MANTA plots(20).For Oceanospirillaceae ASP10-02a genome as-sembly,water was collected from10m in the Amundsen Sea on December19, 2010.Metagenomic libraries were created with the OVATION ultralow kit (NuGen).Overlapping and gapped metagenomic DNA libraries were prepared for sequencing on a HiSeq platform(Illumina).CLC was used to assemble scaffolds,tetranucleotide frequencies of scaffolds were analyzed(43),and draft genomes were generated via binning scaffolds clustered(hierarchical)together in well-supported clades,refined using GC content and taxonomical affiliation (44).ORFs identified in metatranscriptomic analyses were mapped to the Oce-anospirillaceae ASP10-02a genome bin from the best-scoring nucleotide align-ment,using BWA-MEM with default parameters(45).ORFs with>99%similarity to the genome scaffold sequences were used for subsequent analyses of gene expression patterns within this https://www.360docs.net/doc/f35591546.html,plete materials and methods are given in the SI Appendix.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.We thank Nathan Walworth and Ariel Rabines for assistance in the laboratory and field and Rob Middag for iron concentration measurements in our cobalamin stock.We are grateful to Antarctic Sup-port Contractors,especially Jen Erxleben and Ned Corkran,for facilitating fieldwork and to Mak Saito for helpful comments on the manuscript.This study was funded by National Science Foundation(NSF)Antarctic Sciences Awards1103503(to E.M.B.),0732822and1043671(to A.E.A.),1043748 (to D.A.H.),1043635(to D.A.B.),and1142095(to A.F.P.);Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation Grant GBMF3828(to A.E.A.);and NSF Ocean Sciences Award 1136477(to A.E.A.).

1.Arrigo KR,et al.(1999)Phytoplankton community structure and the drawdown of

nutrients and CO2in the southern ocean.Science283(5400):365–367.

2.Matsumoto K,Sarmiento JL,Brzezinski M(2002)Silicic acid leakage from the Southern

Ocean:A possible explanation for glacial atmospheric pCO2.Global Biogeochem Cycles 16((3):5-1–5-3.

3.Arrigo KR,van Dijken GL,Bushinsky S(2008)Primary production in the Southern

Ocean,1997–2006.JGR Oceans113(C8):C08004.

4.Martin JH,Fitzwater SE,Gordon RM(1990)Iron deficiency limits plankton growth in

Antarctic waters.Global Biogeochem Cycles4:5–12.

5.Bertrand EM,et al.(2007)Vitamin B12and iron co-limitation of phytoplankton

growth in the Ross Sea.Limnol Oceanogr52(3):1079–1093.

6.Panzeca C,et al.(2006)B vitamins as regulators of phytoplankton dynamics.Eos

87(52):593–596.

7.Croft MT,Lawrence AD,Raux-Deery E,Warren MJ,Smith AG(2005)Algae acquire

vitamin B12through a symbiotic relationship with bacteria.Nature438(7064):90–93.

8.Bertrand EM,et al.(2013)Methionine synthase interreplacement in diatom cultures

and communities:Implications for the persistence of B12use by eukaryotic phyto-plankton.Limnol Oceanogr58(4):1431–1450.

9.Doxey AC,Kurtz DA,Lynch M,Sauder LA,Neufeld JD(2015)Aquatic metagenomes

implicate Thaumarchaeota in global cobalamin production.ISME J9(2):461–471. 10.Bonnet S,et al.(2010)Vitamin B12excretion by cultures of the marine cyanobacteria

Crocosphaera and Synechococcus.Limnol Oceanogr55(5):1959–1964.

11.Marchant HJ(2005)Cyanophytes.Antarctic Marine Protists,eds Scott FJ,Marchant HJ

(Australian Biological Resources Study,Canberra),pp324–325.

12.Wilkins D,et al.(2013)Key microbial drivers in Antarctic aquatic environments.FEMS

Microbiol Rev37(3):303–335.

13.Williams TJ,et al.(2012)A metaproteomic assessment of winter and summer bac-

terioplankton from Antarctic Peninsula coastal surface waters.ISME J6(10):1883–1900. 14.Bertrand EM,et al.(2011)Iron limitation of a springtime bacterial and phytoplankton

community in the ross sea:Implications for vitamin b(12)nutrition.Front Microbiol2:160.

15.Bertrand EM,Saito MA,Jeon YJ,Neilan BA(2011)Vitamin B??biosynthesis gene di-

versity in the Ross Sea:The identification of a new group of putative polar B??bio-synthesizers.Environ Microbiol13(5):1285–1298.

16.Kazamia E,et al.(2012)Mutualistic interactions between vitamin B12-dependent algae

and heterotrophic bacteria exhibit regulation.Environ Microbiol14(6):1466–1476.

17.Rivkin R(1991)Seasonal Patterns of Planktonic Production in McMurdo Sound,

Antarctica.Am Zool31(1):5–16.

18.Podell S,Gaasterland T(2007)DarkHorse:A method for genome-wide prediction of

horizontal gene transfer.Genome Biol8(2):R16.

19.Bertrand EM,et al.(2012)Influence of cobalamin scarcity on diatom molecular

physiology and identification of a cobalamin acquisition protein.Proc Natl Acad Sci USA109(26):E1762–E1771.

20.Marchetti A,et al.(2012)Comparative metatranscriptomics identifies molecular bases

for the physiological responses of phytoplankton to varying iron availability.Proc Natl Acad Sci USA109(6):E317–E325.

21.van Dongen S(2000)A cluster algorithm for graphs.Technical Report INS-R0010.

(National Research Institute for Mathematics and Computer Science in the Nether-lands,Amsterdam).

https://www.360docs.net/doc/f35591546.html,Roche J,Boyd PW,McKay RM,Geider RJ(1996)Flavodoxin as an in situ marker for

iron stress in phytoplankton.Nature382:802–805.

23.Allen AE,et al.(2008)Whole-cell response of the pennate diatom Phaeodactylum

tricornutum to iron starvation.Proc Natl Acad Sci USA105(30):10438–10443.24.Pankowski A,McMinn A(2009)Development of imunoassays for the iron-regualted

proteins ferredoxin and flavodoxin in polar microalgae.J Phycol45(3):771–783. 25.Saito MA,Goepfert TJ,Ritt JT(2008)Some thoughts on the concept of co-limitation:

Three definitions and the importance of bioavailability.Limnol Oceanogr53(1):276–290.

26.Rojas CM,Ham JH,Deng WL,Doyle JJ,Collmer A(2002)HecA,a member of a class of

adhesins produced by diverse pathogenic bacteria,contributes to the attachment,aggre-gation,epidermal cell killing,and virulence phenotypes of Erwinia chrysanthemi EC16on Nicotiana clevelandii seedlings.Proc Natl Acad Sci USA99(20):13142–13147.

27.Rodionov DA,Vitreschak AG,Mironov AA,Gelfand MS(2003)Comparative genomics of the

vitamin B12metabolism and regulation in prokaryotes.J Biol Chem278(42):41148–41159.

28.Koch F,et al.(2011)The effect of vitamin B12on phytoplankton growth and com-

munity structure in the Gulf of Alaska.Limnolog Oceanog56(3):1023–1034.

29.Grzymski JJ,et al.(2012)A metagenomic assessment of winter and summer bacter-

ioplankton from Antarctica Peninsula coastal surface waters.ISME J6(10):1901–1915.

30.Neufeld JD,Boden R,Moussard H,Sch?fer H,Murrell JC(2008)Substrate-specific

clades of active marine methylotrophs associated with a phytoplankton bloom in a temperate coastal environment.Appl Environ Microbiol74(23):7321–7328.

31.Vila-Costa M,et al.(2006)Phylogenetic identification and metabolism of marine

dimethylsulfide-consuming bacteria.Environ Microbiol8(12):2189–2200.

32.Boden R,Kelly DP,Murrell JC,Sch?fer H(2010)Oxidation of dimethylsulfide to tet-

rathionate by Methylophaga thiooxidans sp.nov.:A new link in the sulfur cycle.

Environ Microbiol12(10):2688–2699.

33.Villeneuve C,Martineau C,Mauffrey F,Villemur R(2012)Complete genome se-

quences of Methylophaga sp.strain JAM1and Methylophaga sp.strain JAM7.

J Bacteriol194(15):4126–4127.

34.Kim HG,Doronina NV,Trotsenko YA,Kim SW(2007)Methylophaga aminisulfidi-

vorans sp.nov.,a restricted facultatively methylotrophic marine bacterium.Int J Syst Evol Microbiol57(Pt9):2096–2101.

35.Dixon JL,Beale R,Nightingale PD(2013)Production of methanol,acetaldehyde,and

acetone in the Atlantic Ocean.Geophys Res Lett40(17):4700–4705.

36.Rue EL,Bruland KW(1997)The role of organic complexation on ambient iron

chemistry in the equatorial Pacific Ocean and the response of a mesoscale iron ad-dition experiment.Limnol Oceanogr42(5):901–910.

37.Kondo Y,et al.(2008)Organic iron(III)complexing ligands during an iron enrichment

experiment in the western subarctic North Pacific.Geophys Res Lett35(12):L12601.

38.Bequevort S,Lancelot C,Schoemann V(2007)The role of iron in bacterial degradation

of organic matter derived from Phaeocystis antarctica.Biogeochemistry83:119–135.

39.Rochelle-Newall EJ,Ridame C,Dimier-Hugueney C,L’Helguen S(2014)Impact of iron

limitation on primary production(dissolved and particulate)and secondary pro-duction in cultured Trichodesmium sp.Aquat Microb Ecol72(2):143–153.

40.Harpole WS,et al.(2011)Nutrient co-limitation of primary producer communities.

Ecol Lett14(9):852–862.

41.Rho M,Tang H,Ye Y(2010)FragGeneScan:Predicting genes in short and error-prone

reads.Nucleic Acids Res38(20):e191.

42.Robinson MD,McCarthy DJ,Smyth GK(2010)edgeR:A Bioconductor package for dif-

ferential expression analysis of digital gene expression data.Bioinformatics26(1):139–140.

43.Ihaka R,Gentleman R(1996)R:A language for data analysis and graphics.J Comput

Graph Stat5:299–314.

44.Brady A,Salzberg SL(2009)Phymm and PhymmBL:Metagenomic phylogenetic clas-

sification with interpolated Markov models.Nat Methods6(9):673–676.

45.Li H(2013)Aligning sequence reads,clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-

MEM.arXiv:1303.3997.

Bertrand et al.PNAS|August11,2015|vol.112|no.32|9943E

C

O

L

O

G

Y

E

N

V

I

R

O

N

M

E

N

T

A

L

S

C

I

E

N

C

E

S

水性聚氨酯性能优缺点

水性聚氨酯的优点: 聚氨酯的全名叫聚氨基甲酯。水性聚氨酯是以水代替有机溶剂作为分散介质的新型聚氨酯体系,其分子结构中含氨基甲酸酯基、脲键和离子键,内聚能高,粘结力强,且可通过改变软段长短和软硬段的比例调节聚氨酯性能。 水性聚氨酯乳液相比较与溶剂型聚氨酯具有以下优点: (1)由于水性聚氨酯以水作分散介质,加工过程无需有机溶剂,因此对环境无污染,对操作人员无健康危害,并且水性聚氨酯气味小、不易燃烧,加工过程安全可靠。 (2)水性聚氨酯体系中不含有毒的-NCO基团,由于水性聚氨酯无有毒有机溶剂,因此产品中无有毒溶剂残留,产品安全、环保,无出口限制。 (3)水性聚氨酯产品的透湿透汽性要远远好于同类的溶剂型聚氨酯产品,因为水性聚氨酯的亲水性强,因此和水的结合能力强,所以其产品具有很好的透湿透汽性。 (4)水作连续相,使得水性聚氨酯体系粘度与聚氨酯树脂分子量无关,且比固含量相同的溶剂型聚氨酯溶液粘度低,加工方便,易操作。 (5)水性聚氨酯的水性体系可以与其它水性乳液共混或共聚共混,可降低成本或得到性能更为多样化的聚氨酯乳液,因此能带来风格和性能各异的合成革产品,满足各类消费者的需求。 并且,由于近年来溶剂价格高涨和环保部门对有机溶剂使用和废物排放的严格限制,使水性聚氨酷取代溶剂型聚氨酷成为一个重要发展方向。 水性聚氨酯膜的优点: 水性聚氨酯树脂成膜好,粘接牢固,涂层耐酸、耐碱、耐寒、耐水,透气性好,耐屈挠,制成的成品手感丰满,质地柔软,舒适,具有不燃、无毒、无污染等优点。将成革的透氧气性、透湿性、低温耐曲折性、耐干湿擦性、耐老化性等,与溶剂型聚氨酯涂饰后的合成革进行了对比研究。结果表明,经水性聚氨酯涂饰的合成革的透氧量达到了4583.53 mg/(em3·h),为溶剂型的1.5倍,且透水汽量达到了615.53 mg/(cm3·h),约为溶剂型的8倍;低温耐曲折次数大于4万次,为溶剂型的2倍。采用水性聚氨酯替代传统的溶剂型聚氨酯完成合成革的

水性聚氨酯丙烯酸酯复合乳液的合成研究

第19卷第3期 厦门理工学院学报Vol.19No.32011年9月Journal of Xiamen University of Technology Sep.2011 [收稿日期]2010-11-19[修回日期]2011-07-08 [基金项目]漳州职业技术学院科研计划项目(ZZY1111) [作者简介]陈建福(1982-),男,助教,硕士,从事应用化学研究.E- mail :qjf1996@https://www.360docs.net/doc/f35591546.html, 水性聚氨酯丙烯酸酯复合乳液的合成研究 陈建福 (漳州职业技术学院食品与生物工程系,福建漳州363000) [摘要]采用种子溶胀乳液聚合法,以水性聚氨酯为种子,甲基丙烯酸甲酯和丙烯酸丁酯为单体制 备水性聚氨酯丙烯酸酯复合乳液,考察了聚合温度、搅拌速度、引发剂种类、引发剂用量及反应时间对聚合过程的影响.结果表明:适宜的聚合温度控制为85?;适宜的搅拌速率为150 250r /min ;采用水溶性引发剂时引发效率较高,过硫酸钾的最佳用量为0.8%;随着反应时间的增加,乳液粒径先减小后增大. 用红外光谱对聚氨酯丙烯酸酯乳液进行分析,表明丙烯酸酯参与了反应. [关键词]水性聚氨酯;丙烯酸酯;复合乳液;合成 [中图分类号]TQ323.8[文献标志码]A [文章编号]1008-3804(2011)03-0069-05 随着人们对清洁生产方式、环保法规的日益关注以及石油化工产品成本的不断升高,水性涂料越 来越受到人们的关注 [1-3].水性聚氨酯涂料是以水替代有机溶剂作为分散介质发展起来的新兴高分子材料,水性聚氨酯特殊的分子结构及聚集状态使其具有优良的耐磨蚀、柔韧性、附着力、耐化学品及软硬随温度变化不大等优点,但水性聚氨酯乳液的自增稠性差、固含量偏低、涂膜的耐水性和光泽性 不足[4-6] .丙烯酸酯类乳液则具有良好的耐水性、耐候性及物理机械性能,用丙烯酸酯类乳液对水性聚氨酯进行改性,可以把两者的性能有机结合起来,从而制备综合性能优良的水性聚氨酯丙烯酸酯(PUA )复合乳液[7-8].本文采用种子溶胀乳液聚合法,不外加乳化剂,合成稳定性好、综合性能优良的丙烯酸酯共聚改性水性聚氨酯乳液,对合成工艺条件进行了系统的探讨.1 实验部分1.1主要原料和试剂 甲苯二异氰酸酯(TDI )、聚酯多元醇(M n =2000)、二羟甲基丙酸(DPMA ),工业级;N ,N -二甲基甲酰胺(DMF )、三乙胺(TEA )、乙二胺,分析纯,用4A 分子筛脱水;甲基丙烯酸甲酯(MMA )、丙烯酸丁酯(BA )、二月桂酸二丁基锡(DBTDL )、过硫酸钾(KPS )、过硫酸铵(APS )、过氧化苯甲酰(BPO )、偶氮二异丁腈(AIBN )等为化学纯,其他试剂均为分析纯. 1.2PUA 复合乳液的制备 将一定量的聚酯多元醇在120?真空脱水,将计量好的甲苯二异氰酸酯缓慢滴加到装有冷凝管、机械搅拌和通氮管的三口烧瓶里,升温到75?反应2h ,加入DMPA 及催化剂,升温到85?反应,隔一定时间取样并测定异氰酸酯基含量(NCO%,质量分数,下同),当NCO%达到理论值时降温到40?,加入丙烯酸酯以降低体系粘度,用三乙胺中和,然后在快速搅拌下加入含有乙二胺的去离子水进行乳化分散,再将乳液升温至85?,加入剩余量的丙烯酸酯单体,并在3h 内滴完引发剂,保温2h 后出料. 1.3性能测试与表征 1)异氰酸酯基含量的测定

丙烯酸酯改性水性聚氨酯的研究进展

丙烯酸酯改性水性聚氨酯的研究进展 简述了丙烯酸酯改性水性聚氨酯4种常用的改性方法:嵌段共聚改性、接枝共聚改性、核-壳乳液聚合改性和互穿聚合物网络改性(IPN);综述了国内外丙烯酸酯改性水性聚氨酯研究进展。 标签:水性聚氨酯;丙烯酸酯;改性 1 前言 聚氨酯(PU)性能优异,具有良好的力学性能、耐磨性、柔韧性、耐化学品性,附着力强、成膜温度低、保光性好,可以室温固化,因此在涂料、胶粘剂及油墨等许多领域都得到广泛的应用[1,2]。目前聚氨酯油墨、胶粘剂等多以溶剂型为主,有机挥发物(VOC)对大气污染,严重破坏了人类的生态环境[3,4]。水性聚氨酯(WPU)以水为分散介质,不含有机溶剂,不燃、无毒、不污染环境、易运输保存,使用方便且软硬度可调、耐低温、耐磨性好及粘附力强,特别适用于烟、酒、食品、饮料、药品、儿童玩具等卫生条件要求严格的包装印刷品[5~7]。然而,WPU还存在耐水性差、耐高温性能不佳、固含量低等缺点。为了提高乳液及膜性能,扩大应用范围,需对PU乳液进行适当的改性。丙烯酸酯乳液具有较好的耐水性、耐候性,但存在硬度大、不耐溶剂等缺点。用丙烯酸酯对WPU改性,可优势互补[8~10]。 2 丙烯酸酯改性WPU的方法 目前,丙烯酸酯改性WPU的主要制备方法有嵌段共聚、接枝共聚、核-壳乳液聚合和互穿聚合物网络(IPN)[11]。 2.1 嵌段共聚 丙烯酸酯嵌段共聚改性WPU的方法主要有双预聚体法和不饱和化合物封端法2种[12]。双预聚体法是用丙烯酸酯改性WPU的较早的方法之一,此法首先制得含羧基和羟基的聚丙烯酸酯,再制备以—NCO封端的水性聚氨酯预聚体溶液,然后水性聚氨酯预聚体溶液和聚丙烯酸酯反应,最后进行扩链,即可得到嵌段共聚物。不饱和化合物封端法是用具有C=C的不饱和化合物对水性聚氨酯预聚体封端,再与丙烯酸酯单体共聚[13]。 任天斌等[14,15]以甲苯二异氰酸酯、聚异丙二醇、甲基丙烯酸羟乙酯及二羟甲基丙酸为原料,通过分子设计合成了带有双键的阴离子水性聚氨酯预聚体(APUA)可聚合乳化剂。陈焕钦[16,17]等也研究了聚氨酯-丙烯酸酯共聚乳液的结构形态、稳定性、胶粒的粒径、流变性、力学性能、热学性能等。路剑威等[18]利用不饱和化合物封端法合成了丙烯酸酯改性WPU分散体,发现膜的耐光性和耐热性都有不同程度的提高,而且涂膜的微区结晶程度明显下降。李延科[19]等用PA对PU进行共混及共聚改性,比较结果表明:共聚改性的PUA乳液的粒

丙烯酸改性水性聚氨酯涂料研究与应用

丙烯酸改性水性聚氨酯涂料的研究与应用 摘要:本文主要综述了丙烯酸改性水性聚氨酯涂料的目前研究状况及其应用,介绍其国内外发展状况,研究进展以及其特性。 关键词:聚氨酯、涂料、丙烯酸、改性、发展状况. 涂料是起保护、装饰和功能作用的一类精细化工产品。它广泛应用于各类建筑物的装饰保护、各类钢铁设施(如码头、海洋石油钻井平台、石油化工装备、输送管道、输变电塔和桥梁等)的防腐保护以及各种工业制品(如飞机、火箭、人造卫星、汽车、船舶、机械电子和轻工家电等)的装饰保护等,可以说涂料在人民的生活中已无处不在,涂料已经与国民经济的各行各业紧密联系在一块了,因此涂料的生产和消费水平已成为一个国家经济发展水平的重要标志之一。 水性涂料由于以水为分散介质,而且由于水性涂料主要由水作为溶剂,不仅成本会远低于有机溶剂(可比溶剂型涂料低20%),还具有运输、贮存安全方便,可节约大量安全经费等优点。涂料的性能主要取决于基料,要提高水性涂料的性能,应该从研究开发高性能水性树脂着手。目前水性涂料中应用最多的是聚氨酯(PU)乳液和聚丙烯酸酯(PA)乳液,二者在性能上具有很强的互补性,由二者通过化学共聚改性得到的聚氨酯一丙烯酸酯(PUA)复合乳液可以配制性能优异的水性涂料,并可用作塑料涂料、汽车修补用罩光涂料以及一般工业用涂料等。 聚氨酯从20世纪30年代开始发展,而在40年代才有少量水性聚氨酯的研究,如1943年德国化学家Schlack在乳化剂及保护胶体存在下,将二异氰酸酯在水中乳化首次成功制备出聚氨酯乳液。1953年Du Pont公司的研究人员将二异氰酸酯基团聚氨酯预聚体的甲苯溶液分散于水,用二元胺扩链,合成了水性聚氨酯。但是当时聚氨酯材料科学刚刚起步,水性聚氨酯还未受到重视直至1967年才首次工业化,1972年拜耳公司正式将聚氨酯水分散体作为皮革涂料进行大批量生产。20世纪七八十年代,美、德、日等国的一些水性聚氨酯产品已从试制阶段发展为实际生产和应用,一些公司有多种牌号的水性聚氨酯产品供应,如德国Bayer公司的Dis percoll KA等系列、美国Wyandotte化学公司的X及E等系列、日本光洋产业公司的水性乙烯基聚氨酯胶黏剂KR系列等。自20世纪90年代后期,水性聚氨酯的应用领域开始不断拓宽,在PVC黏结、汽车内饰件、涂层、涂料等方面都有一定的工业化应用. 我国从1972年开始研究水性聚氨酯,20世纪90年代,安徽大学、丹东轻化工研究院、成都科技大学(现四川大学分部)等的PUD技术成果都先后被转化。目前,我国已有不少领域应用水性聚氨酯产品,但其中许多高档产品仍然不能自给,因此自主研发高性能水性聚氨酯就成为国内聚氨酯领域最热门的方向之一。 1.水性聚氨酯的性能特点: 水性聚氨酯包括聚氨酯水溶液,水分散液和水乳液,是以水为介质的二元胶态体系。它不含或含很少量的有机溶剂,其粒径小于0.1,具有较好的分散稳定性,不仅保留了传统的溶剂型聚氨酯的一些优良性能,而且还具有生产成本低、安全不燃烧、不污染环境、不易损伤被涂饰表面、易操作和改性等优点对纸张、 -1-

压电陶瓷原材料的处理和选择

压电陶瓷原材料的处理和选择 压电陶瓷主要工艺介绍 原材料的本质将对压电陶瓷的最终性能产生决定性的影响。压电陶瓷与传统的陶瓷最大的区别是它对原料的纯度,细度,颗粒尺寸和分布,反应活性,晶型,可利用性以及成本都必须加以全面考虑和控制。 原材料在很大程度上,可决定压电陶瓷元件性能参数的高低,对工艺的顺利进行有重要影响因此,对所用元材料的性能必须有所了解,选择原材料必须符合经济合理的原则。 压电陶瓷所用的各种原料,一般都是各种金属氧化物,有时也采用各种钛酸盐,锆酸盐,锡酸盐,铁酸盐和碳酸盐等。目前压电陶瓷生产上所用的各种原材料,具有很强的地方性,原材料的质量往往随产地和批号的不同而有很大的区别和差异。严重影响了生产质量的稳定性。因此掌握原材料质量对产品性能的影响,进而在生产中预以有效的控制,对确保产品的质量有很大的现实意义。 总的来说,压电陶瓷材料所用的原材料可以分为化工原料和矿物原料二大类。凡是经由化工厂加工处理而提供的原料称为化工原料如BaCO3. SrCO3. CaCO3. MgCO3. Pb3O4. TiO2. ZrO2. Nb2O5. La2O3等,而直接由矿山开采,只经过适当加工的原料就称为矿物原料。常用的矿物原料有粘土,长石,石英,滑石,菱镁矿,大理石,白云石等。 一般的日用瓷,普通的电工瓷和部分的无线电陶瓷如{滑石瓷等}几乎都是用矿物原料配成的,而压电和强介电容器等无线电陶瓷则几乎完全是由化工原料配制而成的。 原料的纯度,细度,{或称粒度}和活性是衡量原料质量的三个重要指标。不论制造钛酸钡,钛酸铅,还是制造二元系锆钛酸铅以及三元系铌镁酸铅等压电陶瓷元件,二氧化钛,二氧化锆,氧化铅或四氧化三铅等,都是主要原材料,一般都在10~60%范围内。 一. 原料的纯度 纯度就是原料的纯净程度,相对来说也是指原料的含杂程度。纯度越高的原料所含的杂质种类和数量越少。化工原料按纯度可分为工业纯和试剂纯二大类。而试剂纯的原料按纯度高低又可分为四级,各种化工原料的主要特点如表1所示。工业纯的原料生产量大,供应稳定,同批产品的一致性和活性都较好,价格也较便宜。因此在能够保证产品产量的前提下应该尽可能选用工业纯原料,以降低成本;但工业纯原料的纯度较低;不同批号原料的纯度波动较大。试剂纯原料的纯度虽较高但在价格方面却要比工业纯原料贵几倍,至几十倍,纯度高的原材料,固然含杂质少,但烧结温度较高,最佳烧结温度也较窄,给烧结带来一定的困难。工业纯原料的纯原料的纯度不高,但是对陶瓷产品性能危害的杂质只有一,二种,因此如果在化工厂采取特殊措施除去这些杂质,又添加某些能改善性能的微量添加剂,而不进行全面的提纯,则不仅原料的成本将进一步大幅度降低,也能更符合陶瓷生产的要求。纯度较低的一些元材料,有的杂质还可以在烧结过程中起到矿化剂或助溶剂的作用,反而使烧结温度较低,最佳温度范围较宽,在一定程度上起到有利作用。这种特定的工业纯原料有时也称为“陶瓷纯”或“电容器纯”。 原材料中含有各种各样的杂质,对压电陶瓷元件的不同型号,配方的作用和影响也各不相同。所以应区别对待,对具体情况需具体分析。对产品性能和工艺过程最敏感的原料应选择较高的纯度;与原料的化学性质相近,能形成置换式固溶体的杂质的最高含量可以略高;对那些能使晶格发生严重畸变的杂质,或者能在晶体中产生自由电子和空穴的“施主杂质”和“受主杂质”以及变价过渡元素{SiO2}的最高含量必须严格控制,有时这类杂质即使只有0.1wt%就会使物理性能严重恶化而完全失去使用阶值。如K+,Na+,等卤族元素将使铁电,压电陶瓷材料的绝缘电阻显著降低,使极化时容易击穿,损耗增大,介电常数和机电耦合系数Kp下降,其总含量控制在0.01%以下。一般来说,在制作PZT压电陶瓷元件中,二氧化钛,二氧化锆和四氧化三铅可采用工业级材料,它们的纯度均能达到98%以上。实际生产中原材料的主成分含量都是采用化学分析方法测定,杂质含量则常在已有经验基础上采用半定量的光谱分析,必要时也可进行x射线衍射分析和电子探针微区分析。 对不同原材料所含不同杂质的允许量是不同的。这主要根据下述三个因素来决定: 1 杂质的类型可分为有害与有利两种。一类是有害杂质,特别是异价离子,如硼B,碳C,磷P,硫S,AL等。由于它们对制品的绝缘,介电性能产生极大影响,有时既使配料中含量在0.1%以下,影响也很大。因此,要求象这类有害杂质的量越少越好。另一类是有利杂质,对与铅离子Pb2+同属二价或与钛离子Ti4+,锆离子Zr4+同属四价,而离子半径相近,能形成置换固溶体的杂质,如钙Ca2+,锶Sr2+,钡Ba2+,镁Mg2+,锡Sn2+,鉿Hf4+等离子。这类杂质离子在配料中可以允许含量稍高一些,一般在0.2~0.5%范围内,对制品性能没有坏的影响,对工艺反而有利。接

水性聚氨酯合成、改性及应用前景

水性聚氨酯合成、改性及应用前景 摘要:随着水性聚氨酯合成与改性工艺的不断进步,水性聚氨酯的应用也得到了极大地提升,反过来由于水性聚氨酯涂料的优异性能以及其极好的应用前景近些年来有关于水性聚氨酯的合成与改性研究也是如火如荼。本文主要介绍了水性聚氨酯涂料的合成方法,综述了水性聚氨酯的改性方法,包括丙烯酸酯改性、环氧树脂改性、有机硅改性、纳米材料改性和复合改性,并对水性聚氨酯涂料的发展进行了展望。 关键字:水性聚氨酯;合成;改性;丙烯酸酯;有机硅。 水性聚氨酯是以水代替有机溶剂作为分散介质的新型聚氨酯体系,也称水分散聚氨酯、水系聚氨酯或水基聚氨酯。水性聚氨酯以水为溶剂,无污染、安全可靠、机械性能优良、相容性好、易于改性等优点。水性聚氨酯可广泛应用于涂料、胶粘剂、织物涂层与整理剂、皮革涂饰剂、纸张表面处理剂和纤维表面处理剂。水性聚氨酯虽然具有很多优良的性能,但是仍然有许多不足之处。如耐水性差、耐溶剂性不良、硬度低、表面光泽差等缺点,由于水性聚氨酯的这些缺点,我们需要对其进行改性,目前常见的改性方法有丙烯酸酯改性、环氧树脂改性、有机硅改性、纳米材料改性和复合改性等,本文将对水性聚氨酯的合成与改性进行阐述。 一、水性聚氨酯的合成 水性聚氨酯的制备可采用外乳化法和自乳化法。目前水性聚氨酯的制备和研究主要以自乳化法为主。自乳化型水性聚氨酯的常规合成工艺包括溶剂法(丙酮法)、预聚体法、熔融分散法、酮亚胺等。丙酮法是先制得含端基的高粘度预聚体,加入丙酮、丁酮或四氢呋喃等低沸点、与水互溶、易于回收的溶剂,以降低粘度,增加分散性,同时充当油性基和水性基的媒介。反应过程可根据情况来确定加入溶剂的量,然后用亲水单体进行扩链,在高速搅拌下加入水中,通过强力剪切作用使之分散于水中,乳化后减压蒸馏回收溶剂,即可制得PU 水分散体系。

水性聚氨酯涂料

双组份水性氨酯的概述 在分子结构中含有氨基甲酸酯重复链节的高分子化合物称为聚氨酯(简称PU )树脂。它由二(或多)异氰酸酯、二(或多)元醇与二(或多)元胺通过逐步聚合反应生成。反应机理如式(1.1)所示: nOCN R NCO +nOH R'CONH R NHCO O ()O nOH R'n 组份水性聚氨酯涂料是由组分A (多异氰酸酯预聚物,如多异氰酸酯的二聚体、三聚体或是它们与羟基化合物生成的低分子量的聚合物)以及组分B (含多羟基的水分散体系,即多元醇组分)组成。双组份水性聚氨酯涂料的成功制备,是聚氨酯涂料史上的一个新的突破。 按使用形式水性聚氨酯涂料可分为单组份水性聚氨酯涂料、双组份水性聚氨酯涂料。 聚氨酯树脂即聚氨基甲酸酯树脂,指树脂中含有相当数量的氨酯键的树脂,链中含有交替的软链段和硬链段,使得其聚集态结构为多相结构,这决定了聚氨酯涂料优良的耐磨、柔韧等性能, 自20 世纪40 年代出现以来,在涂料、弹性体、泡沫塑料及粘合剂等方面均已获得广泛应用。随着社会对挥发性有机化合物(VOC)含量危害认识的提高,在原溶剂型聚氨酯涂料的高性能上极大减少了VOC 含量的水性聚氨酯涂料成为发展最为迅速的高分子材料。水性单组分聚氨酯涂料施工方便,但存在耐化学品性、耐磨性、耐热性、硬度等诸多性能的不足。而双组分水性聚氨酯涂料具有成膜温度低、附着力强、耐磨性好、硬度大以及耐化学品、耐侯性好等优越性能,可取代溶剂型双组分聚氨酯涂料,广泛应用于汽车、木器、塑料、工业维护等诸多领域的表面装饰和防护。 1.2水性聚氨酯国外的发展史 1937年德国化学家Otto Bayer 教授首先利用异氰酸酯与多元醇化合物发生加聚反应制得聚氨酯树脂,随后英、美等国家于1945~1949年从联邦德国获得了有关聚氨酯制造技术,并在1953年相继实现工业化[5]。水性聚氨酯的研究开发及其生产几乎与聚氨酯树脂的工业化同时进行。 1943年德国化学家Schlack 在乳化剂及保护胶体存在下,将二异氰酸酯在水

植物与微生物联合修复土壤石油污染

植物与微生物联合修复土壤石油污染

植物-微生物联合修复土壤石油污染 目录 1 我国的石油污染概况: .... 错误!未定义书签。 2 土壤石油污染危害:...... 错误!未定义书签。 3 土壤石油污染历来修复技术及进展:错误!未定义书签。 3.1微生物修复 (3) 3.2植物修复 (3) 4 植物与微生物联合修复土壤石油污染: (3) 4.1 植物与微生物联合修复土壤石油污染 具体实验引用: (4) 4.1.1 [实验目的] (4) 4.1.2 [方法] (4) 4.1.3 [实验结果] (4) 4.1.4 [实验结论] (4) 4.2 植物与微生物联合修复土壤石油污染 结合实验的理论分析: (4) 5植物-微生物联合修复土壤石油污染技术展望: (7) 参考文献 (7)

植物-微生物联合修复土壤石油污染 (1.郑州大学,河南郑州10459) 摘要石油污染土壤的生物修复技术具有成本低、简便高效、对环境影响小等优点,正逐步成为石油污染治理研究的热点领域,具有广阔的发展前景。介绍了我国的石油污染概况及生物修复技术在石油污染治理中的应用,重点对石油污染土壤的微生物修复、植物修复、植物-微生物联合修复技术的研究进展及各自的优点、局限性进行了综述,并提出了石油污染土壤生物修复技术研究的重点领域。

关键词石油污染土壤微生物修复植物修复 1 我国的石油污染概况: 我国作为石油生产、消费大国,由于生产条件、环保技术等方面相对落后,石油污染问题相当突出。据统计,我国有机污染土壤面积约为0.2亿hm2,其中石油污染占相当比例。我国自1978年原油年产量突破1亿t大关而成为世界十大产油国之一以来,目前勘探开发的油气田和油气藏已有400多个,年产石油污染土壤近10万t,累计堆放量近50万t。以油田为例,每口油井污染的土地面积为200~500m2,全国共有油井20万口,由此造成的土壤污染可达8000万m2,这一数值每年还在增长中。据统计,我国每年有60万t石油经跑、冒、滴、漏途径进入环境,对土壤、地下水、地表水造成污染。此外,污灌也是造成土壤石油污染的原因之一,如沈抚灌区污灌面积达0.87万hm2,全国类似农田有10万hm2,致使农作物中污染物严重超标,农产品质量低下,同时也造成了严重的地下水污染。随着石油开采和使用量的增加,大量的石油及其产品进入环境,不可避免地对环境造成了污染,给生物和人类带来了严重危害。 2 土壤石油污染危害: 1)80%以上的落地原油被截留在50cm以上的表层土壤中,逐渐积累导致土壤结构破坏,影响土壤通透性并对农作物的生长和发育造成很大的负面影响。 2)同时,石油类污染物还可以通过根系吸收后残留在植物体内,通过食物链影响人体健康。 20世纪80年代以来,土壤的石油烃类污染成为世界各国普遍关注的环境问 题。 3 土壤石油污染历来修复技术及进展: 有蒸汽法、抽气法、有机溶剂法、水力冲洗法、氧化法、热处理法、微生物法、植物法等修复技术。其中,天然微生物的生物降解作用已成为消除环境中石油烃类污染的主要机制。 3.1 微生物修复 微生物修复是研究最多、应用也最为广泛的一种生物修复方法。由此产生一系列生物修复技术如土耕法、生物通气法、预制床法、堆肥法、生物反应器等。微生物修复技术是利用土壤中的土著菌或向污染土壤中接种选育的高效降

水性聚氨酯涂料.doc

水性聚氨酯涂料的特点及改性应用综述 学院:材料与化工学院 专业:高分子材料与工程 班级:110311班 姓名:李辽辽 学号:110311122

水性聚氨酯涂料的特点及改性应用综述 李辽辽 (班级:11班学号:110311122) 摘要:介绍水性聚氨酯涂料的分类、特点及其改性应用 关键字:水性聚氨酯涂料;改性;应用 0引言 聚氨酯(又称聚氨基甲酸酯)是指分子主链结构中含有氨基甲酸酯(-NH0COO-)重复单元的高分子聚合物,通常由多异氰酸酯与含活泼氢的聚多元醇反应生成。水性聚氨酯(WPU)是以水代替其他有机溶剂作为分散介质的聚氨酯体系,形成的 WPU 乳液及其胶膜具有优异的机械性能、耐磨性、耐化学品性和耐老化性等特点,可广泛用于轻化纺织、皮革加工、涂料、建筑和造纸等行业。随着世界各国对环境保护的日益重视,越来越多的学者致力于水性聚氨酯涂料的开发,有效限制挥发性有机溶剂的毒害性。虽然水性聚氨酯具有一些优良的性能,但仍有许多不足之处。如硬度低、耐溶剂性差、表面光泽差、涂膜手感不佳等缺点。由于水性聚氨酯在实际应用中存在诸多问题,因此需要对其进行改性。其改性方法主要包括环氧树脂改性、丙烯酸酯改性、有机硅改性、多元改性等。 2水性聚氨酯涂料的特点与分类 2.1水性聚氨酯涂料的特点[1] 水性聚氨酯涂料是以水为介质的二元胶态体系。它不含或含很少量的有机溶剂,粒径小于0.1nm,具有较好的分散稳定性,不仅保留了传统的溶剂型聚氨酯涂料的一些优良性能,而且还具有生产成本低、安全不燃烧、不污染环境、不易损伤被涂饰表面、易操作和改性等优点,对纸张、木材、纤维板、塑料薄膜、金属、玻璃和皮革等均有良好的粘附性。 2.2水性聚氨酯涂料的分类 目前的水性聚氨酯主要包括单组分水性聚氨酯涂料、双组分水性聚氨酯涂料和特种涂料三大类。 2.2.1单组分水性聚氨酯涂料 单组分水性聚氨酯涂料是以水性聚氨酯树脂为基料并以水为分散介质的一类涂料。通过交联改性的水性聚氨酯涂料具有良好的贮存稳定性、涂膜机械性能、耐水性、耐溶剂性及耐老化性能,而且与传统的溶剂型聚氨酯涂料的性能相近,是水性聚氨酯涂料的一个重要发展方向。目前的品种主要包括热固型聚氨酯涂料和含封闭异氰酸酯的水性聚氨酯涂料等几个品种:a.热固型聚氨酯涂料。交联的聚氨酯能增加其耐溶剂性及水解稳定性。聚氨酯水分散体在应用时与少量外加交联剂混合组成的体系叫热固型水性聚氨酯涂料,也叫做外交联水性聚氨酯涂料。b.含封闭异氨酸酯的水性聚氨酯涂料。该涂料的成膜原料由多异氰酸酯组分和含羟基组分两部分组成。多异氰酸酯被苯酚或其它含单官能团的活泼氢原子的化合物所封闭,因此两部分可以合装而不反应,成为单组分涂料,并具有良好的贮藏稳定性。c.室温固化水性聚氨酯涂料。对于某些热敏基材和大型制件,不能采用加热的方式交联,必须采用室温交联的水性聚氨酯涂料。通过与水分散性多异氰酸酯结合,可以改进水性端羟基聚氨酯预聚物/丙烯酸酯混合物,尤其是羟基丙烯酸酯混合物的性能。此类水性聚氨酯涂料,采用特制的多异氰酸酯交联剂,即含(-NCO)端基的异氰酸酯预聚物,经亲水处理后分散于各种含羟基聚合物中而形成的分散体,与多种含羟基聚合物水分散体组成能在室温固化的聚氨酯水性涂料。 d.固化水性聚氨酯涂料。光固化水性聚氨酯涂料采用电子束辐射、紫外光辐射的高强度辐射引发低活性的聚物体系产生交联固化。 2.2.2双组分水性聚氨酯涂料 双组分聚氨酯涂料具有成膜温度低、附着力强、耐磨性好、硬度大以及耐化学品、耐候性好等优越性能,广泛作为工业防护、木器家具和汽车涂料。水性双组分聚氨酯涂料将双组分溶剂型聚氨酯涂料的高性能和水性涂料的低 VOC含量相结合,成为涂料工业的研究热点。水性双组分聚氨酯涂料

改性水性聚氨酯及其粘接性能

改性水性聚氨酯及其粘接性能 综述了水性聚氨酯的改性方法,包括环氧树脂改性、丙烯酸酯改性、有机硅改性、有机氟改性、纳米材料改性、复合改性。比较了各种改性方法的优缺点,指出了水性聚氨酯胶粘剂所存在的问题,展望了水性聚氨酯胶粘剂改性发展趋势。 标签:水性聚氨酯(WPU);胶粘剂;改性 聚氨酯(PU)是在高分子链的主链上含有重复的氨基甲酸酯键结构单元(—NHCOO—)的高分子化合物,具有成膜强度高、柔韧性好、粘附力强,良好的耐磨、耐水、耐化学药品等优点,广泛应用于涂料、胶粘剂、油墨等领域[1~4]。随着环境保护压力的增大,溶剂型聚氨酯胶粘剂应用受到限制。WPU胶粘剂具有不燃、气味小、不污染环境、节能等优点[5~7],正面临前所未有的发展机遇。 1 水性聚氨酯改性 WPU主要是线性热塑性高分子,由于分子间缺乏交联,分子质量较低,所以WPU存在干燥速度慢、耐水耐溶剂性差和胶膜力学强度低等缺点[8,9]。为了改善WPU胶的综合性能,扩大应用领域,必须对其进行改性。 1.1 环氧树脂改性 环氧树脂具有一系列优良的性能[10]。用环氧树脂改性WPU可以形成各种性能新颖的材料。环氧树脂改性方式主要有3种:机械共混、接枝共聚和环氧开环共聚。 Fu等[11]以1,4-丁二醇(BDO)和二羟甲基丙酸(DMPA)为扩链剂,合成了环氧树脂改性WPU乳液。实验结果表明,当环氧树脂E20质量分数为8%时,改性乳液具有更好的综合性能,胶膜的机械性能和热稳定性更好。由此环氧树脂改性的WPU乳液制得的胶粘剂能够满足汽车内饰胶的需求。 Xi等[12]以甲苯二异氰酸酯(TDI)和聚丙烯乙二醇2000(PPG)为原料与环氧树脂反应制备互穿聚合物网络PU胶粘剂。考查了环氧树脂含量对PU胶的形态结构、导电性、热稳定性和粘接性能的影响。结果表明,环氧树脂能改善PU胶的形态结构,提高胶膜的热稳定性和粘接强度。 1.2 丙烯酸酯改性 利用丙烯酸酯改性聚氨酯乳液主要有物理共混和共聚改性2种方法。其中共聚乳液制备方法包括:①共混交联法,即PU乳液和PA乳液共混后,外加交联剂进行交联;②乳液共聚法[13],一般在聚氨酯链中引入不饱和双键,再利用双

水性丙烯酸

水性丙烯酸树脂体系 水性涂料,包括水性木器漆是以水为分散介质和稀释剂的涂料。不常用的溶剂型涂料不同,其配方体系是一个更加复杂的体系。配方设计时,不仅要关注聚合物的类型、乳液及分散体的性能,还需要合理选择各种助剂并考虑到各成分之间的相互影响进行合理匹配。有时还要针对特殊要求选用一些特殊添加剂,形成适用的配方。 配方的基本组成 1) 水性树脂:这是成膜的基料,决定了漆膜的主要功能。 2) 成膜助剂:在水挥发后,使乳液或分散体微粒形成均匀致密的膜,并改善低温条件下的成膜性。 3) 抑泡剂和消泡剂:抑制生产过程中漆液中产生的气泡并能使已产生的气泡逸出液面并破泡。 4) 流平剂:改善漆的施工性能,形成平整的、光洁的涂层。 5) 润湿剂:提高漆液对底材的润湿性能,改进流平性,增加漆膜对底材的附着力。 6) 分散剂:促进颜填料在漆液中的分散。 7) 流变助剂:对漆料提供良好流动性和流平性,减少涂装过程中的弊病。 8) 增稠剂:增加漆液的黏度,提高一次涂装的湿膜厚度,并且对腻子和实色漆有防沉淀和防分层的作用。 9) 防腐剂:防止漆液在贮存过程中霉变。 10) 香精:使漆液具有愉快的气味 11) 着色剂:主要针对色漆而言,使得水性漆具有所需颜色。着色剂包括颜料和染料两大类,颜料用于实色漆(不显露木纹的涂装),染料用于透明色漆(显露木纹的涂装)。 12) 填料:主要用于腻子和实色漆中,增加固体分并降低成本。 13) pH 调节剂:调整漆液的pH 值,使漆液稳定。 14) 蜡乳液或蜡粉:提高漆膜的抗划伤性和改善其手感。 15) 特殊添加剂:针对水性漆的特殊要求添加的助剂,如防锈剂(铁罐包装防止过早生锈)、增硬剂(提高漆膜硬度)、消光剂(降低漆膜光泽)、抗划伤剂、增滑剂(改善漆膜手感)、抗粘连剂 (防止涂层叠压粘连)、交联剂(制成双组分漆,提高综合性能)、憎水剂(使涂层具有荷叶效应)、耐磨剂(增加涂层的耐磨性)、紫外线吸收剂(户外用漆抗老化,防止发黄)等。 16) 离子水:配方设计时往往还要添加少量的去离子水以便制漆。 水性树脂

PMMN-PZT四元系压电陶瓷材料的研究

第2期电子元件与材料 Vol.23 No.2 2004年2月ELECTRONIC COMPONENTS & MATERIALS Feb. 2004 PMMN-PZT四元系压电陶瓷材料的研究 杨为中1孙清池2张云1 1. 四川大学材料科学与工程学院 2. 天津大学材料学院无机非金属材料系 摘要: 研究了铌镁酸铅—铌锰酸铅—锆钛酸铅(PMMN-PZT)四元系统压电陶瓷材料的配方 在相界附近研究了四种不同配方的PMMN-PZT压电陶瓷性能测试 确定了较佳的配方组成研究表明 适宜的烧结温度为1200极化电场为3000 V/mm 33 T/介质损耗tg 压电常数d 33为290×10?12C/N机电耦合系数k P 为0.55 关键词: 铌镁酸铅压电陶瓷 2004 ; polarizing field 3 000 V/mm; polarizing temperature 150 33T/0.004; d 33 290×10-12 C/N, g 33 28.0×10-3 Vm/N, k p 0.55, Q m 1200. Key words: PMMN; PZT; piezoelectric ceramics; electric properties 1965年 Pb(Zr1-x Ti x)O3的基础上添加具有复合 钙钛矿型结构的第三组分铌镁酸 铅 ,研制成了PbTiO3-PbZrO3-Pb(Mg1/3Nb2/3)O 3三元系压电陶瓷[1] ?úPCM相图中 由于在相界附近的组成 因此以获得诸性能都能满足使用性能要求的压电材料可以通过在PCM中添加微量MnO2CoO Cr2O3等改善PCM的烧结性弹性性能及机械品质因数等以各种不同复合钙钛矿型化合物为第三组分及第四组分的三元系 使压电陶瓷的研究前景更为广阔随组分及制作工艺不同 笔者在相界附近研究一定配比的PMMN-PZT四元系压电陶瓷的组成 以得到一种较佳的压电陶瓷材料 分析纯Pb3O4Nb2O5 ZrO2CeO2 7%的聚乙烯醇溶液 银浆 2003-08-28 修回日期 杨为中四川乐山人硕士功能陶瓷材料Tel: (028)85410272电子陶瓷 万方数据

植物与微生物联合修复土壤石油污染

植物-微生物联合修复土壤石油污染 目录 1 我国的石油污染概况: ................................................................................ 错误!未定义书签。 2 土壤石油污染危害:................................................................................. 错误!未定义书签。 3 土壤石油污染历来修复技术及进展:..................................................... 错误!未定义书签。 3.1微生物修复 (3) 3.2植物修复 (3) 4 植物与微生物联合修复土壤石油污染: (3) 4.1 植物与微生物联合修复土壤石油污染具体实验引用: (4) 4.1.1 [实验目的] (4) 4.1.2 [方法] (4) 4.1.3 [实验结果] (4) 4.1.4 [实验结论] (4) 4.2 植物与微生物联合修复土壤石油污染结合实验的理论分析: (4) 5植物-微生物联合修复土壤石油污染技术展望: (7) 参考文献 (7)

植物-微生物联合修复土壤石油污染 (1.郑州大学,河南郑州10459) 摘要石油污染土壤的生物修复技术具有成本低、简便高效、对环境影响小等优点,正逐步成为石油污染治理研究的热点领域,具有广阔的发展前景。介绍了我国的石油污染概况及生物修复技术在石油污染治理中的应用,重点对石油污染土壤的微生物修复、植物修复、植物-微生物联合修复技术的研究进展及各自的优点、局限性进行了综述,并提出了石油污染土壤生物修复技术研究的重点领域。 关键词石油污染土壤微生物修复植物修复 1 我国的石油污染概况: 我国作为石油生产、消费大国,由于生产条件、环保技术等方面相对落后,石油污染问题相当突出。据统计,我国有机污染土壤面积约为0.2亿hm2,其中石油污染占相当比例。我国自1978年原油年产量突破1亿t大关而成为世界十大产油国之一以来,目前勘探开发的油气田和油气藏已有400多个,年产石油污染土壤近10万t,累计堆放量近50万t。以油田为例,每口油井污染的土地面积为200~500m2,全国共有油井20万口,由此造成的土壤污染可达8000万m2,这一数值每年还在增长中。据统计,我国每年有60万t石油经跑、冒、滴、漏途径进入环境,对土壤、地下水、地表水造成污染。此外,污灌也是造成土壤石油污染的原因之一,如沈抚灌区污灌面积达0.87万hm2,全国类似农田有10万hm2,致使农作物中污染物严重超标,农产品质量低下,同时也造成了严重的地下水污染。随着石油开采和使用量的增加,大量的石油及其产品进入环境,不可避免地对环境造成了污染,给生物和人类带来了严重危害。 2 土壤石油污染危害: 1)80%以上的落地原油被截留在50cm以上的表层土壤中,逐渐积累导致土壤结构破坏,影响土壤通透性并对农作物的生长和发育造成很大的负面影响。 2)同时,石油类污染物还可以通过根系吸收后残留在植物体内,通过食物链影响人体健康。 20世纪80年代以来,土壤的石油烃类污染成为世界各国普遍关注的环境问题。 3 土壤石油污染历来修复技术及进展: 有蒸汽法、抽气法、有机溶剂法、水力冲洗法、氧化法、热处理法、微生物法、植物法等修复技术。其中,天然微生物的生物降解作用已成为消除环境中石油烃类污染的主要机制。 3.1 微生物修复 微生物修复是研究最多、应用也最为广泛的一种生物修复方法。由此产生一

改性水性丙烯酸-聚氨酯涂料

改性水性丙烯酸-聚氨酯涂料 朱梦羚(上海理工大学环境工程学院) 摘要:介绍了几种由物理或化学改性得的水性丙烯酸-聚氨酯涂料。综述了经改进后的水性丙烯酸-聚氨酯涂料,在乳液性能、拉伸强度、耐水性、耐化学性质、硬度综合性能的提高,以及新型水性丙烯酸-聚氨酯涂料替代传统溶剂型聚氨酯涂料的可能性。 关键词:水性;聚氨酯;改性;涂料 引言:随着国家对于涂料污染的控制,水性丙烯酸-聚氨酯涂料,以其不易燃,低挥发,硬度等综合性能上的优势,渐渐替代了市面上传统型的溶剂型聚氨酯涂料。本文将详细比较环氧树脂改性聚氨酯-丙烯酸酯乳液;水性双组分丙烯酸酯聚氨酯涂料;自交联型水性丙烯酸—聚氨酯杂化体;阳离子型水性丙烯酸酯聚氨酯塑料涂料;高固体含量水性聚氨酯丙烯酸酯复合乳液;丙烯酸乙酯改性水性聚氨酯涂料这几种改性水性丙烯酸-聚氨酯涂料的改性特点以及其改性后的综合性能进行比较介绍。 1.环氧树脂改性聚氨酯-丙烯酸酯乳 液 环氧树脂改性聚氨酯-丙烯酸酯乳液指的是在目前市场上流行的两种水性溶液基料(PA)聚丙烯酸酯乳液和(PU)聚氨酯乳液所制备的备聚氨酯一丙烯酸酯(PUA)复合乳液中加入环 氧树脂改性所得的环氧树脂改性聚氨酯-丙烯酸酯乳液(PEUA),其在吸水率上明显降低,在硬度等综合性能上也有一定提高。 环氧树脂改性聚氨酯-丙烯酸酯乳液在共聚改性上是使用的化学共聚改性,即在反应初期加入环氧树脂;相比在反应后期加入环氧树脂的物理共聚改性中可以使得形成颗粒小,外观好的乳液,使得乳液的性能有了一定的提高,并且PEUA在耐水性、耐化学性也有提高。 在整个的制作工艺流程中,所加的环氧树脂的质量分数为3%~4%最好,多了虽然乳液的稳定性会提高,但液 膜的耐水性会下降。 2.水性双组分丙烯酸酯聚氨酯涂料 水性双组分丙烯酸酯聚氨酯涂是通过使用内乳化剂二羟甲基丙酸(DMPA)异氰酸酯改性,并与丙烯酸酯多元醇反应得到的一种水性双组分的改性丙烯酸-聚氨酯涂料。其涂抹具有良好的延展性和耐水性,外观上也有改善。 由于改性后的涂料中还有大量的氢键,使得涂料形成的涂抹具有良好的耐磨性。并且当使用的内乳化剂二羟甲基丙酸(DMPA)的质量分数为4%时,所形成的涂膜的延展性,耐磨性,抗水性最佳。因为当DMPA质量分数为4%时,此时的交联度最佳,使得涂膜中的分子亲水性较差,即耐水性最好。 在中和度的选择为100%为宜,此 时的中和度,乳液的颗粒大小适中, 形成的涂膜的外观较好,涂膜所需的 干燥时间也比较短。 在各项性能与相同类型的国外产 品相比也相差无几,同时在延展性上 更好,吸水率也更低。 3.自交联型水性丙烯酸-聚氨酯 杂化体 自交联型水性丙烯酸-聚氨酯杂 化体的特点在于利用了丙烯酸酯类单 体不用于水,而形成的丙烯酸酯树脂 为溶质,聚氯酯为溶剂的水性分散系 的新型水性聚氨酯涂料。该涂料具有

弛豫铁电单晶铌镁酸铅_钛酸铅研究前沿

0引言 压电、铁电单晶与陶瓷是一类重要的、国际竞争极为激烈的多功能材料。利用其力、热、电、光、声 和化学等方面的特殊性能,可对各类信息进行检测、转换、处理和存储,在工业、民用和国防军事等领域应用非常普遍,如医学超声波换能器、水声换能器阵列、声表面波电子器件和电光调制器等。近年来,对弛豫铁电单晶铌镁酸铅-钛酸铅[(1-x )Pb (Mg 1/3Nb 2/3)O 3-xPbTiO 3(PMN-xPT )](其中x 指晶体中PbTiO 3的含量)的基础理论与应用研究吸引了诸多科学工作者的密切关注[1-5]。主要原因在于其机电性能十分优异,例如沿晶体本征[001]方向极化的PMN-33%PT 单晶,其压电系数d33可达2820pC/N ,超过传统PZT 陶瓷四倍有余;电机耦合系数k 33能达到0.94,也远远优于传统铁电晶体或陶瓷材料。 在单晶生长方面,我国中科院上海硅酸盐研究所[2-4]、西安交通大学[5]等相关研究单位都可以批量 生产高质量的PMN-xPT 铁电单晶,且生长方法比较成熟,重复性和稳定性较好,某些方面甚至达到或超越了国际先进水平。长成晶体的尺寸、数量与质量已经接近实际应用场合对该系列单晶材料的要求,这为单晶的器件应用以及产品的商业化奠定了基础。因此,PMN-xPT 单晶极有希望成为下一代宽带、高灵敏度、高分辨率医学超声波换能器,大位移微驱动器及其它机电功能器件的核心材料。本文拟从准同型相界、全矩阵宏观机电系数、损耗和光学、声学性能等方面对PMN-xPT 铁电单晶进行介绍。1PMN-xPT 单晶的准同型相界 室温下,弛豫铁电单晶PMN-xPT 随组分x 的变化会发生组分诱导铁电相变,并存在一个三方相 (自发极化方向为[111])和四方相(自发极化方向为[001])共存的准同型相界,且单晶在相界附近的压电性能最好。准同型相界(morphotropic phase boundary ,MPB ),最早由Jaffe 等人[6]在上世纪70年代研究PZT 压电陶瓷时提出,他发现PZT 材料在Zr/Ti 比为53/47时存在一个准同型相界,相界处三方相和四方相共存。1989年,Choi 等人[7]通过研究不同组分(x=0.275-0.4)PMN-xPT 陶瓷的介电和热释电性质,确定了的相界在x=0.33附近。年,Guo 等人[8]研究了不同组分PMN-xPT 在[001]弛豫铁电单晶铌镁酸铅-钛酸铅研究前沿 张锐,孙恩伟,李秀明,王竹,项阳 (哈尔滨工业大学物理系,黑龙江哈尔滨150080) 摘要:弛豫铁电单晶铌镁酸铅-钛酸铅[(1-x)Pb(Mg1/3Nb2/3)O3-xPbTiO3(PMN-xPT)]具有非常优异的机电性能,吸引了诸多科研领域的学者,从基础理论与实际应用等方面开展了研究工作。该文从PMN-xPT 单晶的准同型相界、全矩阵宏观机电系数、光学与声学性能等方面,系统评述了此体系铁电材料相较于传统铁电材料的特色,介绍了PMN-xPT 单晶在国内外相关研究领域的研究进展及发展方向。理论计算与实验结果表明,PMN-xPT 单晶有望极大地提高医学超声波换能器、水声换能器、声表面波机电器件等的频带宽度、灵敏度及图像分辨率等性能。 关键词:弛豫铁电单晶;PMN-xPT ;机电系数;电光系数;声导波 作者简介:张锐(1973-),男,陕西西安人,哈尔滨工业大学物理系教授,博士生导师,从事弛豫型铁电PMN-PT 和PZN-PT 单晶测试理论与技术方法研究。 中图分类号:TM221.051文献标识码:A 文章编号:1006-2165(2009)06-0086-04收稿日期:2009-06-13 □物理学 第29卷第6期2009年11月大庆师范学院学报JOURNAL OF DAQING NORMAL UNIVERSITY Vol.29No.6 November ,2009