Global Shadow Banking Monitoring Report 2012 (2012年全球影子银行监控报告)

LSEG World-Check One 客户对手风险识别系统说明书

of Politically Exposed Person (PEP) relationships and networks, and is customisable to identify a variety of specific third-party risks.The platform enables:−Advanced name-matching algorithms−Rich data−Secondary matching−Fewer false positives−Faster match resolution−Batch upload−Ongoing rescreening−Superior relevant media content screening Leverage LSEG World-Check, software and servicesWorld-Check One combines World-Check with the next generation of screening software. The software is built to maximise our proprietary World-Check data, capitalising on the powerof multiple secondary identifiers and additional information fields. With Enhanced Due Diligence reports and our Screening Resolution Service, organisations can focus on the recordsthat matter most.Screening software designed for World-Check−LSEG World-Check−Single name checks for manual name checking−Initial and ongoing screening of millions of records−Batch Screening−API with Zero Footprint Screening−A user interface available in multiple languages−Watchlist Screening that enables the user to upload in-house and third-party lists to screen against −Media Check AI-powered negative media screening tool, which pinpoints the media content most relevant to helping you meet your regulatory and legislative compliance requirements also available as an optional add-on via the World-Check One API−Identify Ultimate Beneficial OwnershipPowered by market-leading Dun & Bradstreet UBO data, our opt-in feature UBO Check lets you search and screen for regulatory and reputational risk with World-Check Risk Intelligence, all on one platform−Improved workflowOur enhanced case management functionality facilitates better visibility and improved breakdownof records, to help speed up the remediation process−Vessel due diligenceWith IHS Maritime data, check vessels for ownership structure and IMOs, and screen for any sanction and/or regulatory risk with World-Check all on our Vessel Check feature−Identity VerificationIdentity Check enables organisations to verify the identity of individuals and businesses through adata-based identity verification approach, utilising independent and authoritative identity data sources.World-Check One benefits More precision World-Check One enables greater customisation and control at name-matching level to screen against specific lists and data sets, or specific fields within those data sets, such as gender, nationality and date of birth.Lowering false positives When combined with the configurable name-matching algorithms and filtering technology in World-Check One, multiple secondary identifiers in World-Check help to reduce false positives.Intelligent teamwork The case management tool enables managers to define customised workflow to route cases to the right individuals and specialist teams, thereby reducing cycle times, promoting speed and efficiency, and giving teams more time to focus on investigations of the highest concern.Get more done with less World-Check One is designed to reduce the burden of daily customer screening. Its customisable searches, reduced false positives, ongoing screening capability and improved workflow reduce cycle times.Streamline the screening processOur World-Check One API facilitates the integration oflarge volumes of information and advanced functionalities into existing workflows and internal systems. Thisincreases the operational efficiency of the screeningprocess for onboarding, Know Your Customer (KYC) and third-party risk due diligence.One solution to screen multiple listsWatchlist Screening allows users to upload internaland third-party lists to World-Check One and apply thematching logic to all data sets, ensuring minimisation offalse positives and consistency of results.More precise media screeningNegative media forms part of a best practice approach to customer due diligence and ongoing risk assessment. AI delivers next-generation media screening of unstructured media, along with improved relevancy of results andworkflow integration, to enable better decision-making.Audit trail* and reporting capabilitiesWorld-Check One provides an extensive auditingcapability, with date-stamped actions for the matchresolution process. It includes detailed reports that canbe used as part of management reporting and regulatory proof of due diligence.World-Check One delivers a more efficient approachBalancing the regulatory and operational burden requires organisations to take a more targeted approach towards customer due diligence. Firms often have to do more with less. They require moreefficiency from the tools, technology and operations that support customer due diligence.*Not applicable for clients that do not require an audit trail.World-Check One leveragesWorld-CheckFind hidden risk in business relationships and human networks.World-Check provides trusted information to help businesses comply with regulations and identify potential financial crime. Since its inception, World-Check has served the KYC and third-party screening needs of the world’s largest firms, simplifying day-to-day onboarding and monitoring decisions, and helping businesses comply with anti-money laundering and countering financing of terrorism legislation. World-Check data is sourced from the public domain, deduplicated, structured into individual reports and linked to associations or human networks. Each action is underpinned by a meticulous, regulated research process.In addition to 100 percent sanctions coverage, additional risk-based information is sourced from extensive global media research by more than 400 research analysts working in over 65 languages, covering 240 countries. Information is collated from an extensive network of thousands of reputable sources, including 700+ sanction, watch, regulatory and law enforcement lists, local and international government records, country-specific data sources, international adverse electronic and physical media searches, and English and foreign language data sources.Sophisticated softwareA unified platform approach to customer due diligence.Our highly scalable solution is built for single users or large teams to support a carefully targeted approach to screening during KYC onboarding, ongoing monitoring and rescreening cycles. The system makes remediation quicker and more intelligent, and is adaptable to meet regulation changes.Additional servicesWe help organisations to optimise their resources and reduce operational cost.Screening Resolution Service – Our service highlights positive and possible matches for any customer identification programme detecting heightened risk individuals and entities, screened againstWorld-Check.By using a managed service like Screening Resolution Service, you can reduce your cost of compliance and free up departments to focus their efforts on activities such as tracking and implementing regulatory change. LSEG Due Diligence Reports – Use our Due Diligence reports to help you comply with anti-money laundering, anti-bribery and corruption regulations, or ahead of a merger, acquisition or joint venture. Y ou can also use them for third-party risk assessment, onboarding decision-making and identifying beneficial ownership structures.Using only ethical and non-intrusive research methods, LSEG is committed to principles of integrity and accountability. Subjects are not aware when we carry out an investigation, and we never misrepresent our activities. LSEG has a dedicated risk and control team that performs regular audits of the service, and external accreditation to ISAE 3000 standard through Schellman & Company, LLC.LSEG World-Check One for Salesforce – World-Check One for Salesforce connects your customer and third-party data from Salesforce with our proprietary World-Check to help you decide whether to onboard the vast majority of entities being screened or use further due diligence.Collaboration toolsEnhanced enterprise-level case management capabilities facilitate work on cases with assigned colleagues and teams when investigating risk, to ensure all decisions and discussions are captured as part of your audit trail. Secondary matchingApply secondary matching rules at list level based on your approach. Greater control enables reduced false positives. User experienceProven user interface promotes minimum user interaction.Cross-team communicationLanguage capabilities, ideal for multinational companies and team remediation.Prove due diligenceEach step of the screening process is tracked and saved for auditing purposes. T o satisfy regulatory demands, organisations can retrieve a detailed report showing the decision-making process and the individuals involved during every stage of the remediation process.World-Check One’s easy-to-use interface helps compliance teams work more efficiently.454312LDA3267049/10-23。

单位招聘考试PTN专业(试卷编号161)

单位招聘考试PTN专业(试卷编号161)1.[单选题]R860设备最大支持本地会话的ID为()A)1200B)1800C)1000答案:B解析:2.[单选题]当前SPN网络中,ISIS协议一般使用()层次A)1) LEVEL1B)2) LEVEL2C)3) LEVEL 1/2答案:B解析:3.[单选题]SPE从NPE学到核心网路由后,不再向其他UPE和SPE发布,只向UPE发布一条()A)默认路由B)明细路由C)黑洞路由答案:A解析:4.[单选题]烽火CiTRANS R865设备共有()槽位,其中业务槽位()个A)32/24B)32/26C)30/24D)30/26答案:A解析:5.[单选题]U31服务器对应的SQL Server默认的用户名是A)RootB)ZTEC)adminD)sa答案:D解析::SNMPB)读团体名:fiber-RO读写团体名:fiber-RW安全名:fiberhome组名:onlye访问控制列表名称:SNMPC)用户组名:NMS用户名:fiberhome访问控制列表名:SNMPD)以上说法均不正确答案:C解析:7.[单选题]OAM测试,做的一条百兆业务,测试环回帧功能时,设置完成后,需要在源站的哪个盘上点右键进行“状态监视”A)上话业务的ESJ1盘B)XCUJ1盘C)XSJ1盘D)NMUJ1盘答案:B解析:8.[单选题]对于CES业务,当AC侧需要加载保护时,如果加载的是1+1保护,那么主备AC端口会受到2份完全一样的报文,此时该如何转发?()A)与传统网络一样,同样进行仿真转发,再还原B)对与两份完全一样的报文,在备用AC端口进行丢弃C)对与两份完全一样的报文,在接入侧设备进行选收D)对与两份完全一样的报文,在接入侧设备进行并收,透传给基站答案:B解析:9.[单选题]下面评估内容不属于结构评估的是A)超大环和超长链B)成环率C)超大汇聚节点D)双归保护结构答案:D解析:10.[单选题]PTN640设备在配置1:1保护时,LSP标签值正向与反向( )A)可以相同;B)一定相同;C)一定不同;D)没有要求。

网络安全口语

网络安全口语随着互联网的飞速发展,网络安全已经成为我们生活中不可忽视的问题。

在日常生活和工作中,我们经常会涉及到网络安全的话题,因此学习一些网络安全口语是非常必要的。

本文将为您介绍一些常用的网络安全口语,帮助您更好地保护个人信息和网络安全。

1. 信息保护 (Information Protection)- Could you please encrypt my files? (请为我的文件加密。

)- Remember to set a strong password for your accounts. (记得为你的账户设置一个强密码。

)- Be cautious when sharing personal information online. (在网上共享个人信息时要小心。

)- Have you enabled two-factor authentication for your email? (你的电子邮件启用了双重认证吗?)- Have you backed up your important files? (你备份了重要文件吗?) - Don't click on suspicious links or download unknown attachments. (不要点击可疑的链接或下载未知附件。

)- It's important to keep your antivirus software up to date. (保持你的防病毒软件更新很重要。

)- Make sure to log out of your accounts when using public computers. (在使用公共计算机时一定要退出你的账户。

)- Avoid using public Wi-Fi for sensitive transactions. (避免在公共Wi-Fi环境下进行敏感交易。

美版paypal风控注意事项

美版paypal风控注意事项随着互联网的发展,我们的支付方式也越来越多样化。

PayPal作为一种国际通用的支付方式,已经成为人们在国际交易中最受欢迎的方法之一。

然而,在使用PayPal的同时,我们也需要了解它的一些风险控制注意事项。

下面就来了解一下美版PayPal风控注意事项。

1.网络安全意识PayPal账户的安全性非常重要,一个账户的安全性取决于用户的个人信息及登录密码是否泄露。

我们需要提高网络安全意识,设置强密码,避免在可疑网站上输入个人信息。

2.账户安全PayPal账户被窃取是用户遭受支付风险的一种常见情况。

为了确保账户安全,请启用两步验证(2FA)和检查有关账户安全的选项,如使用钓鱼邮件报告功能、电话验证等。

如果您是商家,请遵守PayPal 的安全要求并确保您的网站是安全的。

3.交易安全PayPal的交易安全机制包括卖家保护和买家保护,让我们花费更少但依然保证交易安全。

当接收到付款时,卖家应该立即发货并在PayPal界面上标注交付方式和时间,避免与买家产生交易诉讼。

对于买家来说,需要确保对方的主页、评价、历史交易等信息均是真实有效的。

4.系统更新在购物、支付完成后,需要对电脑操作系统和浏览器进行更新和维护。

PayPal的官方网站和客户端在升级器中会通知您升级安全版本,保持官方的支付服务最佳体验。

5.遵循PayPal规定PayPal有严格的使用规定,需要向PayPal输入真实姓名和地址等资料,只有做到合法合规,才能让自己的PayPal账户更加安全。

同时,也需要遵守PayPal服务条款和协议,并在使用支付功能时遵守PayPal 的规定。

总结在使用美版PayPal时,我们需要提高个人的网络安全意识,设置强密码,并且检查并更新电脑系统,尽力确保账户、交易和信息的安全。

此外,需要仔细阅读并遵循PayPal的规定,确保使用方式符合规范。

通过这些措施,我们能更好地保护我们的PayPal账号和交易,让我们的支付过程更加稳定和可靠。

2012datacenter密钥

2012年,美国国家安全局(NSA)的前雇员爱德华·斯诺登爆料,揭露了美国政府秘密监控计划Prism,其中泄露了一份对被监控数据中心的密钥。

这一事件引发了全球范围内的轰动,也引发了对数据安全和隐私保护的深刻思考。

在这篇文章中,我们将对2012datacenter密钥这一事件进行分析和解读。

一、事件背景1.斯诺登爆料2012年,爱德华·斯诺登向《卫报》和《华盛顿邮报》提供了大量的证据,揭露了美国政府秘密监控计划Prism。

Prism被揭露后,人们发现美国政府通过此计划可以对全球范围内的通讯数据进行监控和窃取。

这一事件引起了全球范围内的关注和愤怒,亦引发了对数据安全和隐私保护的广泛讨论。

二、事件影响1.全球关注2012年,Prism事件成为全球关注的焦点,并引发了关于政府监控行为和个人隐私保护权利的激烈讨论。

人们开始对政府的监控行为提出质疑,并加大了对数据安全和隐私保护的关注程度。

2.数据中心密钥泄露在Prism事件中,斯诺登泄露了一份对被监控数据中心的密钥,这一行为引发了对数据中心安全性的质疑。

数据中心一直被视为各个行业的重要基础设施,而其安全性更是备受重视。

密钥的泄露给数据中心的安全性带来了严重的挑战和危机。

三、事件启示1.数据中心安全性问题Prism事件中密钥的泄露凸显了数据中心的安全性问题。

数据中心的安全性一直备受关注,而此次事件的发生引发了对数据中心安全性的深刻思考。

数据中心在承载着各种重要信息和数据的也面临着来自外部的安全威胁和挑战。

数据中心安全性的加强势在必行。

2.数据隐私保护Prism事件引发了对数据隐私保护的讨论。

人们开始重新审视自己的个人隐私权利,并对政府和企业在数据收集和利用方面的行为进行了持续关注和监督。

数据隐私保护成为了社会的热点话题,也催生了相关法律法规的出台和完善。

四、对策建议1.加强数据中心安全管理对于数据中心来说,加强安全管理是至关重要的。

数据中心需要采取一系列有效的措施,包括加密技术、权限管理、入侵检测等,以保障数据的安全性和完整性。

中美两国影子银行系统比较与建议

模 式 。 即政 府 制定 专 门的监 管 美 两 国影 子 银 行 跟商 业 银 行 的 影 子银行 体系监管 评述提 出 : 监

法 律 , 设 立 全 国性 的 监 管 机 类 似度不 同 。美 国的投资 银行 、 管 评 述 主 张赋 予 融 资渠 道 狭 窄 并 构 。二是 监 管 机构 设 置 状况 类 对 冲 基金 等 非 银行 金 融 机 构所 银 行特许 专营权 , 门从 事投 资 专 似 。美 国监 管 机构 包 括 美 国 国 发 挥 的融 资 中介作 用 跟 一 般 意 银 行业务 ; 监管评 述提 出通过对 会和证券 交易 委员会 , 日常 监管 义上 的银行极 为类 似 , 只是 监管 融 资 渠道 狭 窄 银行 开 放 中 央银

( ) 一 中美 两 国影 子 银行 体 律来 规范投 资银行 ; 而我 国只有 大 部 分来 自股 票 承销 发 行 以及 系 的共 同点 。一是 监 管 模式 类 《 券法》 证券 投资基金 法》 证 和《 ,

似 。我 国对 投 资银 行 的监 管模 还 需 要 出 台相 关 的法 律 来 填补 美 国投行 。 四是 中美 两 国影子

量 的金融 风险 , 终 引发 全球金 理 办法》 最 。 占 1%左右 , 0 且收 益与金 融衍 生

融 危 机 。本 文 比较 了 中美 两 国

( ) 二 中美 两 国影 子 银 行 体 品有着 紧密的联 系。20 年 , 0 7 只

的影 子银行 体系 , 出了强化我 系 的不 同点 。一是 中美 两 国监 有 高盛 的杠 杆 率 ( 提 总负 债/ 资 净

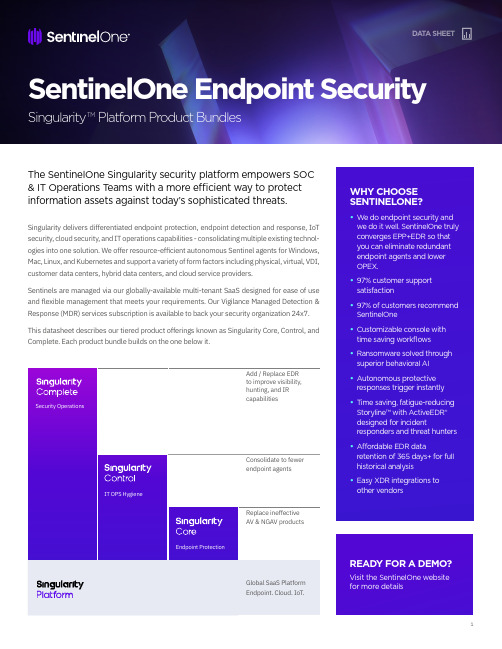

SentinelOne Singularity安全平台产品说明书

SentinelOne Endpoint SecuritySingularity TM Platform Product BundlesGlobal SaaS implementation. Highly available. Choice of locality (US, EU, APAC).Flexible administrative authentication and authorization: SSO, MFA, RBAC Administration customizable to match your organizational structure 365 days threat incident historyIntegrated SentinelOne ThreatIntelligence and MITRE ATT&CKThreat IndicatorsData-driven dashboard securityanalyticsConfigurable notifications by emailand syslogSingularity Marketplace ecosystem ofbite-sized, 1-click appsSingle API with 340+ functionsCore is the bedrock of all SentinelOne endpoint security offerings. It is our entry-level endpoint security product for organizations that want to replace legacy AV or NGAV with an EPP that is more effective and easy to manage. Core also offers basic EDR functions demonstrating the true merging of EPP+EDR capabilities. Threat Intelligence is part of our standard offering and integrated through our AI functions and SentinelOne Cloud. Singularity Core features include:• Built-in Static AI and Behavioral AI analysis prevent anddetect a wide range of attacks in real time before they causedamage. Core protects against known and unknown malware,Trojans, hacking tools, ransomware, memory exploits, scriptmisuse, bad macros, and more.• Sentinels are autonomous which means they apply prevention and detection technology with or without cloud connectivity and will trigger protective responses in real time.• Recovery is fast and gets users back and working in minuteswithout re-imaging and without writing scripts. Any unautho-rized changes that occur during an attack can be reversed with 1-Click Remediation and 1-Click Rollback for Windows.• Secure SaaS management access. Choose from US, EU, APAC localities. Data-driven dashboards, policy management by site and group, incident analysis with MITRE ATT&CK integration,and more.Control is made for organizations seeking the best-of-breed security found in Singularity Core with the addition of “security suite” features for endpoint management. Control includes all Core features plus:• Firewall Control for control of network connectivity to and from devices including location awareness• Device Control for control of USB devices and Bluetooth/BLEperipherals• Rogue visibility to uncover devices on the network that needSentinel agent protection• Vulnerability Management, in addition to ApplicationInventory, for insight into 3rd party apps that have knownvulnerabilities mapped to the MITRE CVE databaseSingularity Platform Features & Offerings All SentinelOne customers have access to these SaaS management console features:Complete is made for enterprises that need modern endpoint protec-tion and control plus advanced EDR features that we call ActiveEDR®. Complete also has patented Storyline™ tech that automatically contex-tualizes all OS process relationships [even across reboots] every second of every day and stores them for your future investigations. Storyline™ saves analysts from tedious event correlation tasks and gets them to the root cause fast. Singularity Complete is designed to lighten the load on security administrators, SOC analysts, threat hunters, and incident responders by automatically correlating telemetry and mapping it into the MITRE ATT&CK® framework. The most discerning global enterpris-es run Singularity Complete for their unyielding cybersecurity demands. Complete includes all Core and Control features plus:• Patented Storyline™ for fast RCA and easy pivots• Integrated ActiveEDR® visibility to both benignand malicious data•D ata retention options to suit every need,from 14 to 365+ days• Hunt by MITRE ATT&CK ® Technique• Mark benign Storylines as threats for enforcement bythe EPP functions•C ustom detections and automated hunting rules withStoryline Active Response (STAR™)•T imelines, remote shell, file fetch, sandbox integrations,and moreVigilance MDR Services SubscriptionSentinelOne Vigilance Managed Detection & Response (MDR) is a ser-vice subscription designed to augment customer security organizations. Vigilance MDR adds value by ensuring that every threat is reviewed, acted upon, documented, and escalated as needed. In most cases we interpret and resolve threats in about 20 minutes and only contact you for urgent matters. Vigilance MDR empowers customers to focus only on the incidents that matter making it the perfect endpoint add-on solution for overstretched IT/SOC Teams.More info:/global-services/services-overview/SentinelOne Readiness Services SubscriptionSentinelOne Readiness is an advisory subscription service designed to guide your Team before, during, and after product installation with a structured methodology that gets you up and running fast and keeps your installation healthy over time. Readiness customers are guided through deployment best practices, provided periodic agent upgrade assistance, and receive quarterly ONEscore TM health check-ups to en-sure your SentinelOne estate is optimized.More info:/global-services/readiness/Impressive capabilities. Easy to deployand use EDR.Director of Cybersecurity - Heathcare1B - 3B USD“Single platform the SOC can rely on.Security & Risk Management - Finance50M - 250M USD“Increased efficiency. We’ve absolutelyseen an ROI.Global InfoSec Director - Manufacturing10B - 25B USD“Global Support & Service OfferingsSentinelOne Readiness Deployment & Ongoing Health SubscriptionAvailableGLOBAL DA T A CENTERS US, Frankfurt, T okyo, A WS GovCloud Highly AvailableSENTINELONE LOCA TIONS Mountain View, CA (HQ) T el Aviv , Boston, Amsterdam, T okyo, Oregon USInnovative. Trusted. Recognized.Record Breaking ATT&CK Evaluation • No missed detections. 100% visibility • Most Analytic Detections 2 years running • Zero Delays. Zero Config ChangesA Leader in the 2021 Magic Quadrant for Endpoint Protection Platforms Highest Ranked in all Critical Capabilities Report Use Cases4.998% of Gartner Peer Insights TM Voice of the Customer Reviewers recommend SentinelOneAbout SentinelOne。

网络越境使用指南:畅游全球互联网(八)

网络越境使用指南:畅游全球互联网网络的发展为我们提供了一个广阔的信息交流平台,让我们能够随时随地获取各种知识和享受各种娱乐。

然而,由于地理位置和政策的限制,我们有时无法正常访问全球互联网上的资源。

本文将为大家提供一些网络越境使用的指南,帮助大家畅游全球互联网。

一、选择适合的VPN工具VPN(虚拟专用网络)是一种可以建立安全连接的技术,可以让用户通过一个中继服务器访问Internet,并将用户的真实IP地址隐藏起来。

选择适合的VPN工具是网络越境使用的基础。

目前市面上有很多不同的VPN服务提供商,用户可以根据自己的需求选择。

在选择时,需要考虑以下几个因素:1. 服务器数量和分布:服务器数量越多、分布越广,越能提供更好的访问体验。

2. 速度和稳定性:网络连接速度较快且稳定的VPN服务,可以保证流畅的上网体验。

3. 隐私政策:选择有严格隐私政策的VPN,以保护个人信息安全。

4. 价格:不同VPN服务提供商的价格各异,用户可以根据自己的财力状况选择适合的服务。

在选择VPN工具时,还需要关注该服务是否符合自己所在地区的法律法规,以免违反相关规定。

二、访问全球内容使用VPN工具可以让我们绕过地理限制,访问全球范围的互联网资源。

以下是一些建议,帮助大家畅游全球互联网:1. 海外视频娱乐:有些视频网站和流媒体平台的内容在特定地区是无法访问的。

通过选择合适的VPN服务器,我们可以突破地域限制,畅享全球的视频娱乐资源。

2. 获取全球资讯:不同地区有不同的新闻报道和资讯资源。

通过使用VPN,我们可以访问境外的新闻网站和社交媒体,了解更多全球范围内的动态和信息。

3. 跨境购物和电商:有时我们会想购买海外特色产品或者通过跨境电商平台购物。

通过选择适合的VPN服务器,我们可以访问到特定地区的电商网站,享受全球购物的便利。

4. 跨国工作和学习:对于一些需要跨国交流的工作或学习任务,使用VPN可以轻松地访问到国外的网站和资源,提高工作和学习效率。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Global Shadow Banking Monitoring Report 201218 November 2012Table of contentsExecutive Summary (3)Introduction (6)1.Methodology (6)2.Overview of macro-mapping results (8)3.Cross-jurisdiction analysis (12)3.1Structure of financial systems (12)3.2Growth trends of non-bank financial intermediaries across jurisdictions (14)position of non-bank financial intermediaries (15)4.1Breakdown by sub-sectors of non-bank financial intermediaries at end-2011 (15)4.2Recent trends in sub-sectors (18)5.Interconnectedness between banks and shadow banking entities (non-bank financial intermediaries) (20)5.1Analysing interconnectedness between banks and shadow banking entities (20)5.2High-level analysis of interconnectedness (21)5.3Data Issues for further enhancement of monitoring (23)6.Finance Companies - Overview of Survey Responses (25)6.1Definition and types of finance companies (25)6.2Regulatory frameworks (25)6.3Policy tools and monitoring frameworks to address shadow banking risks (26)6.4Business models (26)6.5Risks (27)Annex 1: Template used for the data collection exerciseAnnex 2: Share of total assets by jurisdictionAnnex 3: Survey questionnaire on finance companiesAnnex 4: “Possible Additional Measures of Interconnectedness between Banks and Shadow Banking System”Annex 5: Country case studies on (i) Dutch Special Financial Institutions (ii) Financial Companies in India and (iii) Securities Lending in the United States.Executive SummaryThe “shadow banking system” can broadly be described as “credit intermediation involving entities and activities outside the regular banking system”. Although intermediating credit through non-bank channels can have advantages, such channels can also become a source of systemic risk, especially when they are structured to perform bank-like functions (e.g. maturity transformation and leverage) and when their interconnectedness with the regular banking system is strong. Therefore, appropriate monitoring and regulatory frameworks for the shadow banking system needs to be in place to mitigate the build-up of risks.The FSB set out its initial recommendations to enhance the oversight and regulation of the shadow banking system in its report to the G20 in October 2011.1 Based on the commitment made in the report, the FSB has conducted its second annual monitoring exercise in 2012 using end-2011 data. In the 2012 exercise coverage was broadened to include 25 jurisdictions and the euro area as a whole, compared to 11 jurisdictions and the euro area in the 2011 exercise. The addition of new jurisdictions brings the coverage of the monitoring exercise to 86% of global GDP and 90% of global financial system assets.The exercise was conducted by the FSB Analytical Group on Vulnerabilities (AGV), the technical working group of the FSB Standing Committee on Assessment of Vulnerabilities (SCAV), using quantitative and qualitative information, and followed a similar methodology as that used for the 2011 exercise. Its primary focus is on a “macro-mapping” based on national Flow of Funds and Sector Balance Sheet data (hereafter Flow of Funds), that looks at all non-bank financial intermediation2 to ensure that data gathering and surveillance cover the areas where shadow banking-related risks to the financial system might potentially arise.The main findings from the 2012 exercise are as follows3:•According to the “macro-mapping” measure, the global shadow banking system, as conservatively proxied by “Other Financial Intermediaries” grew rapidly before the crisis, rising from $26 trillion in 2002 to $62 trillion in 2007.4 The size of the totalsystem declined slightly in 2008 but increased subsequently to reach $67 trillion in 2011 (equivalent to 111% of the aggregated GDP of all jurisdictions). Compared to last year’s estimate, expanding the coverage of the monitoring exercise has increasedthe global estimate for the size of the shadow banking system by some $5 to $6trillion.•The shadow banking system’s share of total financial intermediation has decreased since the onset of the crisis and has remained at around 25% in 2009-2011, after having peaked at 27% in 2007. In broad terms, the aggregate size of the shadowbanking system is around half the size of banking system assets.1/publications/r_111027a.pdf2Unless otherwise mentioned, non-bank financial intermediation (or intermediaries) excludes intermediation by insurance companies, pension funds and public financial institutions.3The figures in this report are subject to change until the report is published.4“Other Financial Intermediaries” are a category of Flow of Funds that comprises financial institutions that are not: banks, central banks, public financial institutions, insurance companies or pension funds.•The US has the largest shadow banking system, with assets of $23 trillion in 2011, followed by the euro area ($22 trillion) and the UK ($9 trillion). However, the US’share of the global shadow banking system has declined from 44% in 2005 to 35% in2011. This decline has been mirrored mostly by an increase in the shares of the UKand the euro area.•There is a considerable divergence among jurisdictions in terms of: (i) the share of non-bank financial intermediaries (NBFIs) in the overall financial system; (ii) relative size of the shadow banking system to GDP; (iii) the activities undertaken bythe NBFIs; and (iv) recent growth trends.•The Netherlands (45%) and the US (35%) are the two jurisdictions where NBFIs are the largest sector relative to other financial institutions in their systems5. The share ofNBFIs is also relatively large in Hong Kong (around 35%), the euro area (30%), Switzerland, the UK, Singapore, and Korea (all around 25%).•Jurisdictions where NBFIs are the largest relative to GDP are Hong Kong (520%), the Netherlands (490%), the UK (370%), Singapore (260%) and Switzerland (210%).Part of this concentration can be explained by the fact that these jurisdictions are significant international financial centres that host activities of foreign-ownedinstitutions.•After the crisis (2008-2011), the shadow banking system continued to grow although at a slower pace in seventeen jurisdictions (half of them being emerging markets anddeveloping economies undergoing financial deepening) and contracted in the remaining eight jurisdictions.•National authorities have also performed more detailed analyses of their NBFIs in the form of case studies, examples of which are presented in Annex 56. Although further data and more in-depth analysis may be needed, these studies illustrate theapplication of risk factor analysis (e.g. maturity/liquidity transformation, leverage, regulatory arbitrage) to narrow down to a subset of entities and activities that mightpose systemic risk.•Among the jurisdictions where data is available, interconnectedness risk tends to be higher for shadow banking entities than for banks. Although further analysis may beneeded with more cross-border and prudential information, shadow banking entitiesseem to be more dependent on bank funding and are more heavily invested in bankassets, than vice versa.•Regarding finance companies, which are a focus area for this year’s report, the survey responses from 25 participating jurisdictions suggest the existence of a widerange of business models covered under the same label. The responses also underlined the important role finance companies play in providing credit to the realeconomy, especially by filling credit voids that are not covered by other financial 5According to case studies presented in annex 5, a closer analysis of the Dutch shadow banking sector shows that most non-bank entities are so-called special financial institutions (SFIs) rather than shadow banks, which are mainly tax-driven.6These case studies are examples of applying the proposed framework to the currently available data in certain member jurisdictions and do not necessarily represent the assessment of the FSB.institutions. A few jurisdictions have also emphasised the need to enhance monitoring of the sector as finance companies may be liable to specific risk factorsand/or regulatory arbitrage. However, since the size of the sector is limited, participating jurisdictions do not see significant systemic risks arising from this sector at present.Going forward, the monitoring exercise should benefit from continuous improvement and thorough follow-up by jurisdictions of identified gaps and data inconsistencies. It is also important that the monitoring framework remains sufficiently flexible, forward-looking and adaptable to capture innovations and mutations that could lead to growing systemic risks and arbitrage.Further improvements in data availability and granularity will be essential for the monitoring exercise to be able to adequately capture the magnitude and nature of risks in the shadow banking system. This is especially relevant for those jurisdictions that lack fully developed Flow of Fund statistics (e.g. China, Russia, Saudi Arabia) or have low granularity at the sector level resulting in a relatively large share of unidentified NBFIs (e.g. UK, euro area-wide Flow of Funds). Data enhancing efforts may leverage off on-going initiatives to improve Flow of Funds statistics (e.g. the IMF/FSB Data Gaps initiatives) or on supervisory information and market intelligence as a complement to Flow of Funds data. Survey data or market estimates can also be used more extensively for those parts of the shadow banking system (e.g. hedge funds) for which Flow of funds do not provide a reliable estimate.The use of additional analytical methods based on market, supervisory and other data to conduct deeper assessment of risks, for example, maturity transformation, leverage and interconnectedness (see as an illustration Annex 4) would also provide significant value added to the report.Lastly, the mostly entity-based focus of the “macro-mapping” should be complemented next year by obtaining more granular data on assets/liabilities (e.g. repos, deposits) or expanding activity-based monitoring, to cover developments in relevant markets where shadow banking activity may occur, such as repo markets, securities lending and securitisation. In addition to existing supervisory and market information, the implementation of some of the shadow banking regulatory recommendations, such as the transparency recommendations from the FSB Workstream on securities lending and repos (WS5), is expected to provide the necessary data for such an enriched monitoring.77/publications/r_121118b.pdfIntroductionEfficient monitoring of the size and of the adaptations and mutations of shadow banking are important elements for strengthening the oversight of this sector, which is a key priority for the FSB and the G20. In its report “Shadow Banking: Strengthening Oversight and Regulation” to the G20 (hereafter October 2011 Report)8, the FSB set out approaches for effective monitoring of the shadow banking system and has published the results of its first attempt to map the shadow banking system using data from eleven of its member jurisdictions9 and the euro area. It also committed to conducting annual monitoring exercises to assess global trends and risks in the shadow banking system through its Standing Committee on Assessment of Vulnerabilities (SCAV), drawing on the enhanced monitoring framework defined in the report.Based on this commitment, the FSB recently conducted its annual monitoring exercise for 2012, significantly broadening the range of jurisdictions covered to include all 24 FSB member jurisdictions, Chile10, and the euro area. This expanded coverage enhances the comprehensive nature of the monitoring, since participating jurisdictions represent in aggregate 86% of global GDP and 90% of global financial system assets (up from 60% and 70% per cent, respectively). The exercise was conducted by the Analytical Group on Vulnerabilities (AGV), the technical working group of the SCAV, during summer 2012, using end-2011 data as well as additional qualitative information and market intelligence. This report summarises the preliminary results of the 2012 monitoring exercise.1.MethodologyIn its October 2011 report, the FSB broadly defined shadow banking as the system of credit intermediation that involves entities and activities fully or partially outside the regular banking system, and set out a practical two-step approach in defining the shadow banking system:•First, authorities should cast the net wide, looking at all non-bank credit intermediation to ensure that data gathering and surveillance cover all areas whereshadow banking-related risks to the financial system might potentially arise.•Second, for policy purposes, authorities should narrow the focus to the subset of non-bank credit intermediation where there are (i) developments that increase systemicrisk (in particular maturity/liquidity transformation, imperfect credit risk transfer and/or leverage), and/or (ii) indications of regulatory arbitrage that is underminingthe benefits of financial regulation.Based on the above approach, the FSB recommended that authorities enhance their monitoring framework to assess shadow banking risks through the application of a stylised monitoring process, guided by seven high-level principles. This process would require authorities to first assess the broad scale and trends of non-bank financial intermediation in 8/publications/r_111027a.pdf9These were Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Korea, the Netherlands, Spain, the UK and the US.10Chile participates in the AGV and voluntarily participated in the exercise.the financial system (“macro-mapping”), drawing on information sources such as Flow of Funds and Sector Balance Sheet data (hereafter Flow of Funds data), and complemented with other relevant information such as supervisory data. Authorities should then narrow down their focus to credit intermediation activities that have the potential to pose systemic risks, by focusing in particular on activities involving the four key risk factors as set out in the second step (i.e. maturity/liquidity transformation, imperfect credit risk transfer and/or leverage).In line with these recommendations, the 2012 annual monitoring exercise primarily focused on the “macro-mapping” or the first phase of the stylised monitoring process through collecting the following data and information from 25 jurisdictions and the euro area:(i) Flow of Funds data as of end-201111based on the template used for the 2011monitoring exercise and recommended in the October 2011 report (Annex 1);(ii) A short analysis of national trends in shadow banking; and(iii) Additional data and qualitative information on “finance companies” based on a survey questionnaire.In addition, on a voluntary basis, several jurisdictions provided case studies on specific entities or activities involved in non-bank financial intermediation in their jurisdictions.12 Flow of Funds data are a useful source of information in mapping the scale and trends of non-bank credit intermediation. They provide generally high quality, consistent data on the bank and non-bank financial sectors’ assets and liabilities, and are available in most jurisdictions, though there is room for improvement.13 The components related to the non-bank financial sector, and especially the “Other Financial Intermediaries (OFIs)” sector (which typically includes NBFIs that cannot be categorised as insurance corporations or pension funds or public sector financial entities), can be used to obtain a conservative proxy of the size of the shadow banking system14 and its evolution over time.In order to cast the net wide, the macro-mapping needs to be conservative in nature, looking at all non-bank financial intermediation so as to cover all areas where shadow banking-related risks might potentially arise (for example through adaptation and mutations). This would alert the authorities to areas where adaptations and mutations could lead to points of risk in the system. Authorities could then conduct more detailed monitoring for policy purposes, with an eye towards identifying the subset of non-bank financial intermediation where there are (i) developments that increase systemic risk (in particular maturity/liquidity transformation, 11For Switzerland, end-2010 data were used for Other Financial Intermediaries.12Australia, France, India, Korea, Mexico, the Netherlands, the UK and the US submitted case studies on a voluntary basis.These were discussed at the AGV meeting on 17-18 July.13Some jurisdictions still lack Flow of Funds statistics, and have to use other data sources which may be less consistent.Even when Flow of Funds data are available, their granularity and definitions differs across jurisdictions and have been adjusted as necessary. In the October 2011 report, the FSB recommended that member jurisdictions improve the granularity of the Flow of Funds data, and expects the quality of its annual monitoring exercise to increase as a result of improvements in Flow of Funds statistics. This will also be supported by the international initiative to improve the Flow of Funds data under the IMF/FSB Data Gaps initiative based on recommendation 15 in the report by the IMF/FSB to the G20 on The financial crisis and information gaps, November 2009.14For example, see Pozsar et al. (2010) Shadow Banking, FRBNY Staff Reports, July, Bakk-Simon et al. (2012) Shadow Banking in the Euro Area: An Overview, ECB Occasional Paper Series, April, and Deloitte Centre for Financial Services (2012) The Deloitte Shadow Banking Index: Shedding light on banking’s shadows.imperfect credit risk transfer and/or leverage), and/or (ii) indications of regulatory arbitrage that is undermining the benefits of financial regulation (Exhibit 1-1).Measuring the shadow banking systemSimplified conceptual image Exhibit 1-12.Overview of macro-mapping resultsThe main results of the 2012 exercise at macro-mapping the shadow banking system can be briefly summarised as below:•Aggregating Flow of Funds data from 20 jurisdictions (Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, China, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Mexico, Russia,Saudi Arabia, Singapore, South Africa, Switzerland, Turkey, UK and the US) and theeuro area data from the European Central Bank (ECB),assets in the shadowbanking system in a broad sense (or NBFIs, as conservatively proxied by financialassets of OFIs15) grew rapidly before the crisis, rising from $26 trillion in 2002 to$62 trillion in 2007. The total declined slightly to $59 trillion in 2008 but increasedsubsequently to reach $67 trillion in 2011 (Exhibit 2-1).•Expanding the coverage of the monitoring exercise has increased the global estimate for the size of the shadow banking system by some $5 to 6 trillion in aggregate,bringing the 2011 estimate from $60 trillion with last year’s narrow coverage to $67trillion with this year’s broader coverage. The newly included jurisdictions contributing most to this increase were Switzerland ($1.3 trillion), Hong Kong ($1.3trillion), Brazil ($1.0 trillion) and China ($0.4 trillion).15OFIs comprise of all financial institutions that are not classified as banks, insurance companies, pension funds, public financial institutions, or central banks.Total assets of financial intermediaries20 jurisdictions and euro area Exhibit 2-1Source: National flow of funds data.•The shadow banking system’s share of total financial intermediation has decreased since the onset of the crisis and has been recently stable at a level around 25% of thetotal financial system (Exhibit 2-2), after having peaked at 27% in 2007. Inaggregate, the size of the shadow banking system in a broad sense is around half thesize of banking system assets.Share of total financial assets20 jurisdictions and euro area Exhibit 2-2Source: National flow of funds data.•The size of the shadow banking system (or NBFIs), as conservatively proxied by assets of OFIs, was equivalent to 111% of GDP in aggregate for 20 jurisdictionsand the euro area at end-2011 (Exhibit 2-3), after having peaked at 128% of GDPin 2007.Assets of non-bank financial intermediaries20 jurisdictions and the euro area Exhibit 2-3Source: National Flow of Funds data.• The US has the largest shadow banking system, with assets of $23 trillion in2011 on this proxy measure, followed by the euro area ($22 trillion) and the UK ($9trillion). However, its share of the total shadow banking system for 20jurisdictions and the euro area has declined from 44% in 2005 to 35% in 2011 (Exhibit 2-4).16 The decline of the US share has been mirrored by an increase in theshares of the UK and the euro area.Share of assets of non-bank financial intermediaries 20 jurisdictions and euro areaExhibit 2-4Source: National flow of funds data.16 Changes in the national shares may also reflect shifts in exchange rates and changes in accounting treatments.These aggregates count as a conservative estimate of the size of the shadow banking system, across a number of dimensions. Firstly, the category “other financial intermediaries” may include entities that are not engaged in credit intermediation. The range of entities included in this category can vary from one jurisdiction to another. Secondly, “financial assets” include non-credit instruments that may constitute part of the long credit intermediation “chain”. Third, in some cases total assets are used rather than financial assets, because of data limitations.The remainder of this report examines the composition and growth of the shadow banking system in more detail.•Section 3 offers a more detailed cross-jurisdiction analysis of the size of the shadow banking system, and growth trends since the onset of the crisis. It shows aconsiderable divergence among jurisdictions in terms of: (i) the importance of NBFIs in the overall financial system (% share within the financial system); (ii)size relative to real economy (GDP); and (iii) growth trends, especially after thecrisis.Jurisdictions where NBFIs are large relative to the financial system and have experienced robust growth since 2007 may deserve more in-depth investigation (e.g.the UK). For emerging market and developing economies where the NBFI sector isgrowing at a strong pace but remains small overall, the challenge consists in strikingan appropriate balance between the need for increasing financial inclusion and broadening access to finance, including through NBFIs, and the importance ofpreserving financial stability.•Section 4 provides a detailed analysis of the components of the shadow banking system, as conservatively proxied by OFIs, and growth trends since the onset of thecrisis. Investment funds other than MMFs seem to constitute the largest share (35%of OFIs in 2011), followed by structured finance vehicles (10%). The size of all sub-sectors of OFIs is, on aggregate, either stable or declining since 2007, with the largest declines affecting MMFs and structured finance vehicles.•Thanks to improvements in the granularity of data provided by certain countries, the share of the unidentified component (“others”) within the OFI sector has beenreduced from 36% last year (with data from 11 jurisdictions) to 18% this year (withdata for 25 jurisdictions) and 33% (with data for 20 jurisdictions and the euro area).However, since other jurisdictions with a large shadow banking system (e.g. the euroarea and the UK) lack granular data for NBFIs, further improvement in the Flow ofFunds statistics or adjustments by other data sources is essential to obtain a betterpicture of this sector.•Systemic risks stemming from interconnectedness between banks and shadow banking entities are examined in Section 5. Among the various measures to capturesuch risks, (i) direct credit exposures and (ii) funding dependence across sectors areassessed based on data submitted from some jurisdictions. A cross-jurisdictioncomparison of jurisdictions where data is available shows that there is wide variationin the degree of interconnectedness between the two sectors in different financial systems. However, in most jurisdictions, interconnectedness risk tends to be higher for shadow banking entities than for banks. Shadow banking entities seem to be moredependent on bank funding and are more heavily invested in bank assets, than viceversa. This assessment may be improved with wider data coverage, more granulardata, and supplementing the assessment by additional information, for instance sourced from prudential regulators.•Finally, a brief summary of responses to the additional survey questionnaire on finance companies is set out in Section 6. The responses from 25 participating jurisdictions suggest the existence of a wide range of businesses covered under thecategory “finance companies”, a term that broadly refers to non-banks that provideloans to other entities. While the composition of this sector varies across jurisdictions, the responses underlined the importance of finance companies in providing credit to the real economy especially to fill credit voids that are notcovered by other financial institutions. A few jurisdictions have also emphasised theneed to enhance monitoring of the sector as finance companies may be liable to specific risk factors and/or regulatory arbitrage. However, since the size of the sectoris limited, participating jurisdictions do not see significant risks at present from asystemic point of view.3.Cross-jurisdiction analysisFlow of Funds data allow for cross-jurisdiction comparisons of the structure of financial systems and of the importance and growth of NBFIs as conservatively proxied by OFIs (see template in Annex 1).3.1Structure of financial systemsThree main groups of jurisdictions emerge when analysing the structure of financial systems based on the share of banks, insurance companies and pension funds, other NBFIs/OFIs, public financial institutions and central banks in the total (see Annex 2 and Exhibit 3-1): • A first group includes advanced economies characterised by a dominant share of banks combined with a limited share of OFIs that does not exceed 20%. Jurisdictionssuch as Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, Spain fall in this category.• A second group includes economies where the share of OFIs is above 20% of the total financial system and relatively similar, or higher, to that of banks. For instance,the Netherlands, the UK, the US, fall in this category.• A third group includes emerging market and developing economies where the share of public financial institutions or the central bank is significant, often on account ofhigh foreign exchange reserves or sovereign wealth funds, and where the share ofOFIs is relatively low. This group includes jurisdictions such as Argentina17, China,Indonesia, Russia and Saudi Arabia.17In Argentina, foreign currency deposits constituted by the banks pursuant to liquidity regulations are included in the assets of the Central Bank. These regulations require banks to make foreign currency deposits at the Central Bank in compliance with requirements associated with their own obligations denominated in foreign currency.Three examples of different financial structuresShare of total assets by jurisdiction, in per cent Exhibit 3-1Source: National flow of funds data.Size of other financial intermediariesAs a percentage of GDP, by jurisdiction Exhibit 3-2AR = Argentina; AU = Australia; BR = Brazil; CA = Canada; CH = Switzerland; CL = Chile; CN = China; DE = Germany; ES = Spain; FR = France; HK = Hong Kong; ID = Indonesia; IN = India; IT = Italy; JP = Japan; KR = Korea; MX = Mexico; NL = Netherlands; RU = Russia; SA = Saudi Arabia; SG = Singapore; TR = Turkey; UK = United Kingdom; US = United States; XM = Euro area; ZA = South Africa.1 20 jurisdictions and euro area.Sources: National flow of funds data; IMF.Globally, the shadow banking system, as conservatively proxied by OFIs, represents on average 25% of financial system assets and 111% of the aggregated GDP, for the sample of 20 participating jurisdictions and the euro area. As shown in Exhibit 3-2, these aggregate numbers mask wide disparities between jurisdictions. Five jurisdictions (Hong Kong, the Netherlands, the UK, Singapore and Switzerland) are characterised by a large size of NBFIs relative to GDP, which is partly attributable to the fact that these countries also have large。