Planning Persuasive Argument

? 1996 C. Reed, D. Long and M. Fox

Proceedings of the ECAI’96 Workshop ‘Gaps and Bridges:

New Directions in Planning and Natural Language Generation’Edited by K. Jokinen, M. Maybury, M. Zock and I. Zukerman

Planning Persuasive Argument

Chris Reed 1, Derek Long 2 and Maria Fox 2

Abstract. Argument represents an opportunity for a system to convince a possibly sceptical or resistant audience of the veracity of its own beliefs. This ability is a vital component of rich communication, facilitating explanation, instruction, cooperation and conflict resolution. In this paper, a proposal is presented for the architecture of a system capable of constructing arguments which comprise not only logical structure but also the rhetoric which makes that structure persuasive. The design of the architecture has made use of the wealth of naturally occurring argument, which, unlike much natural language, is particularly suited to analysis due to its clear aims and structure. The proposed framework is based upon a core hierarchical planner conceptually split into four levels of processing, the highest being responsible for abstract, intentional and pragmatic guidance, and the lowest handling realisation into natural language. The higher levels will have control over both the logical form of the argument, and over matters of style and rhetoric, in order to produce as cogent and convincing an argument as possible.

1 INTRODUCTION

In this paper an architecture is presented for the autonomous construction of argument, outlining the components required for persuasive communication. Argument plays a crucial role for a communicative system as a means of persuading the human interlocutor to adopt some belief which is of interest to the system. This might be simply to improve the coherence between their beliefs or to obtain a specific effect such as an adoption of some new goal by the hearer, elicitation of particular information,or instruction upon some particular topic. Human-human argumentation makes heavy use of rhetorical embellishments, and the integration of precomputational models of rhetoric with the discourse planning required for the construction of the logical core of an argument forms the cornerstone of the current work.

In order to model argument and design a rubric for its automatic synthesis, it is necessary to have a clear understanding of its nature. Unlike much natural discourse, arguments always have clearly defined goals, and in particular, to persuade a particular audience of a particular proposition. This perhaps oversimplifies the issue, since rarely will an argument be instigated between two parties who believe thesis and antithesis,and even more rarely does argument terminate with both parties believing the same proposition. Importantly, despite the clarity an argument often has in its goals, the methods by which those goals are achieved are rarely at all clear. The process of argumentation itself is the same, regardless of the myriad situations in which it

1Department of Computer Science, University College London, Gower St.,London, WC1E 6BT, UK; C.Reed@https://www.360docs.net/doc/b34556819.html,

https://www.360docs.net/doc/b34556819.html,/staff/C.Reed

2 Department of Computer Science, Durham University, Durham, UK D.P.Long@https://www.360docs.net/doc/b34556819.html,; M.Fox@https://www.360docs.net/doc/b34556819.html, can occur - public oration, debating house discourse, legal argument, newspaper commentary, scientific papers, etc. What is different between these settings (and indeed between individual arguments) is the way in which various factors affect the presentation of the argument: the ways in which the bare facts can be put across. This moulding of an argument is accomplished through the use of rhetoric and forms an essential part of the framework examined below.

It is assumed throughout that the argument will ultimately be rendered in natural language, though the theory does not depend upon the assumption, since the framework employs intentional structures which are sufficiently abstract to remain unchanged by a shift to some more simple and restrictive artificial language.

2 OVERVIEW

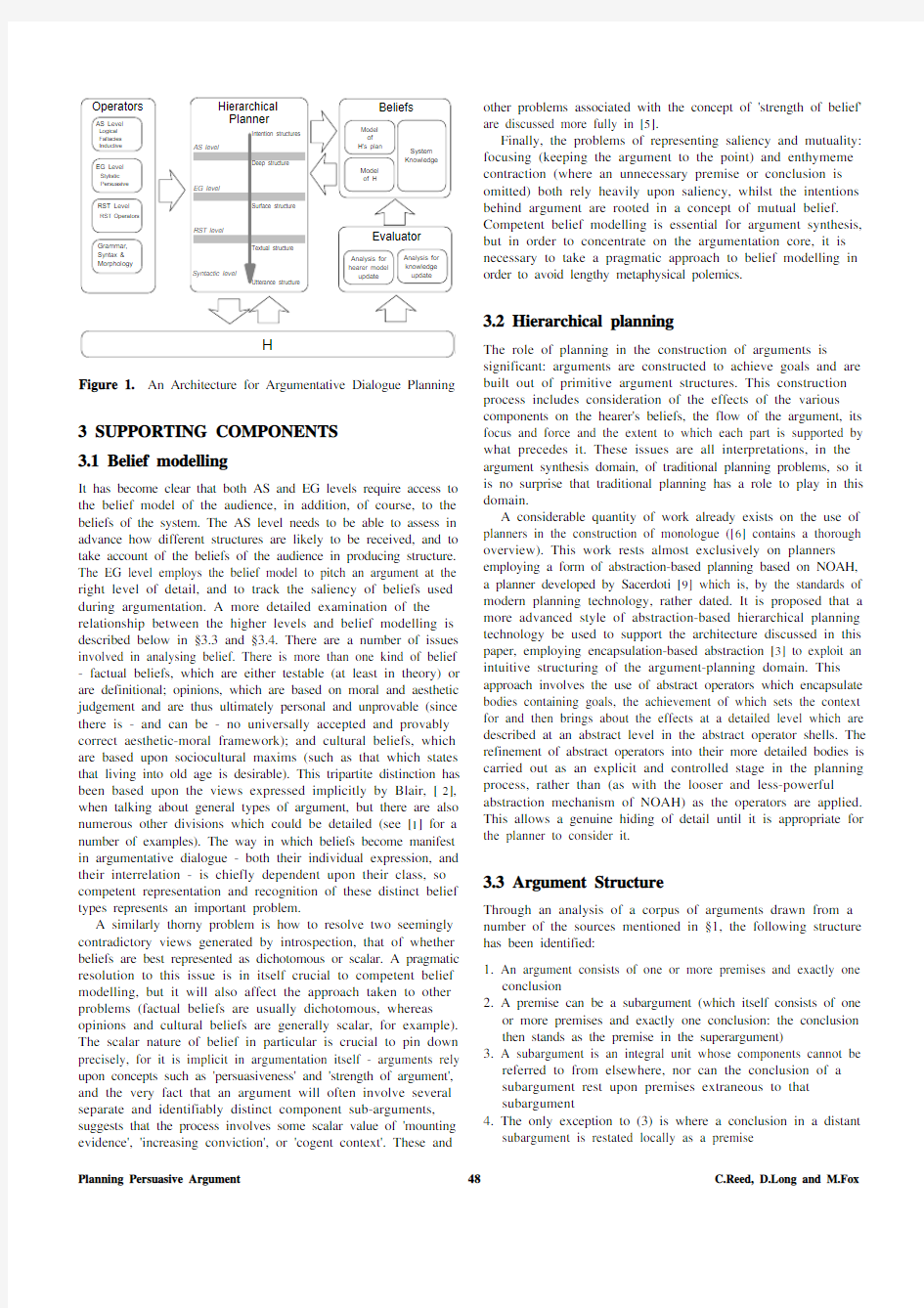

The architecture proposed in this paper rests in a hierarchical framework, reflecting the distinct though inter-related levels of structure within arguments identified through their analysis. There is a part of argument synthesis which is concerned with the resolution of syntax, expression and morphology, as with any natural language synthesis. This comprises the lowest level.Above this, there sits a level responsible for the coordination of sentence and intersentence relations, imposing structure at a more abstract level. This intermediate level is also responsible for handling aspects of communication such as focusing. Finally, at the higher pragmatic levels, new machinery and techniques are required to produce cogent argument. This generation can be accomplished through two complimentary levels, one of which handles the structural aspects of argument, and the other effecting complex modifications to that structure and controlling stylistic devices. The former, the Argument Structure (AS) level, is at the highest level of abstraction, since it produces the logical form of the argument employing predominantly intentional data structures,by using logical operators, fallacy 1 operators and inductive operators. This form is then augmented and modified by the subordinate Eloquence Generation (EG) level, which employs heuristics based upon rhetoric and contextual parameters, and is concerned with such properties of a speech as its length, detail,meter, ordering of subarguments, grouping of subarguments,enthymeme contraction, use of repetition, alliteration and so on.This architecture is summarised below in Fig.1.

Note that the 'intermediate level' has, in the figure, been labelled 'RST level': the functionality proposed for this level is in line with much of the work carried out on Rhetorical Structure Theory [7]. (The inclusion of RST has also led to the Eloquence Generation level being so named: the more appropriate 'Rhetoric level' is open to confusion with RST).

1 Lists of informal fallacies are common. though rarely identical; see, for

example, [12].

Figure 1. An Architecture for Argumentative Dialogue Planning

3 SUPPORTING COMPONENTS 3.1 Belief modelling

It has become clear that both AS and EG levels require access to the belief model of the audience, in addition, of course, to the beliefs of the system. The AS level needs to be able to assess in advance how different structures are likely to be received, and to take account of the beliefs of the audience in producing structure.The EG level employs the belief model to pitch an argument at the right level of detail, and to track the saliency of beliefs used during argumentation. A more detailed examination of the relationship between the higher levels and belief modelling is described below in §3.3 and §3.4. There are a number of issues involved in analysing belief. There is more than one kind of belief - factual beliefs, which are either testable (at least in theory) or are definitional; opinions, which are based on moral and aesthetic judgement and are thus ultimately personal and unprovable (since there is - and can be - no universally accepted and provably correct aesthetic-moral framework); and cultural beliefs, which are based upon sociocultural maxims (such as that which states that living into old age is desirable). This tripartite distinction has been based upon the views expressed implicitly by Blair, [2],when talking about general types of argument, but there are also numerous other divisions which could be detailed (see [1] for a number of examples). The way in which beliefs become manifest in argumentative dialogue - both their individual expression, and their interrelation - is chiefly dependent upon their class, so competent representation and recognition of these distinct belief types represents an important problem.

A similarly thorny problem is how to resolve two seemingly contradictory views generated by introspection, that of whether beliefs are best represented as dichotomous or scalar. A pragmatic resolution to this issue is in itself crucial to competent belief modelling, but it will also affect the approach taken to other problems (factual beliefs are usually dichotomous, whereas opinions and cultural beliefs are generally scalar, for example).The scalar nature of belief in particular is crucial to pin down precisely, for it is implicit in argumentation itself - arguments rely upon concepts such as 'persuasiveness' and 'strength of argument',and the very fact that an argument will often involve several separate and identifiably distinct component sub-arguments,suggests that the process involves some scalar value of 'mounting evidence', 'increasing conviction', or 'cogent context'. These and

other problems associated with the concept of 'strength of belief'are discussed more fully in [5].

Finally, the problems of representing saliency and mutuality:focusing (keeping the argument to the point) and enthymeme contraction (where an unnecessary premise or conclusion is omitted) both rely heavily upon saliency, whilst the intentions behind argument are rooted in a concept of mutual https://www.360docs.net/doc/b34556819.html,petent belief modelling is essential for argument synthesis,but in order to concentrate on the argumentation core, it is necessary to take a pragmatic approach to belief modelling in order to avoid lengthy metaphysical polemics.

3.2 Hierarchical planning

The role of planning in the construction of arguments is significant: arguments are constructed to achieve goals and are built out of primitive argument structures. This construction process includes consideration of the effects of the various components on the hearer's beliefs, the flow of the argument, its focus and force and the extent to which each part is supported by what precedes it. These issues are all interpretations, in the argument synthesis domain, of traditional planning problems, so it is no surprise that traditional planning has a role to play in this domain.

A considerable quantity of work already exists on the use of planners in the construction of monologue ([6] contains a thorough overview). This work rests almost exclusively on planners employing a form of abstraction-based planning based on NOAH,a planner developed by Sacerdoti [9] which is, by the standards of modern planning technology, rather dated. It is proposed that a more advanced style of abstraction-based hierarchical planning technology be used to support the architecture discussed in this paper, employing encapsulation-based abstraction [3] to exploit an intuitive structuring of the argument-planning domain. This approach involves the use of abstract operators which encapsulate bodies containing goals, the achievement of which sets the context for and then brings about the effects at a detailed level which are described at an abstract level in the abstract operator shells. The refinement of abstract operators into their more detailed bodies is carried out as an explicit and controlled stage in the planning process, rather than (as with the looser and less-powerful abstraction mechanism of NOAH) as the operators are applied.This allows a genuine hiding of detail until it is appropriate for the planner to consider it.

3.3 Argument Structure

Through an analysis of a corpus of arguments drawn from a number of the sources mentioned in §1, the following structure has been identified:

1.An argument consists of one or more premises and exactly one conclusion

2.A premise can be a subargument (which itself consists of one or more premises and exactly one conclusion: the conclusion then stands as the premise in the superargument)

3.A subargument is an integral unit whose components cannot be referred to from elsewhere, nor can the conclusion of a subargument rest upon premises extraneous to that subargument

4.The only exception to (3) is where a conclusion in a distant subargument is restated locally as a premise

Analyses based on similar theories are performed in many texts: see for example, [13]. It is this structure which the AS level constructs, linking premises to conclusions through the use of three groups of operators: standard logical relations, rhetorical fallacies, and inductively reasoned implications.

The first group comprises Modus Ponens, Modus Tollens, Conjunction, Disjunctive Syllogism, Hypothetical Syllogism and Constructive Dilemma (MP being by far the most common). The second group comprises around two dozen fallacies which, though illogical, are very common in natural language. Some are, without a doubt, tricks of the rhetorician, designed to mislead the audience (Red Herring and Straw Man, for example), whilst most are used quite inadvertently, but nevertheless assist in strengthening an argument (at least in the perceptions of some audiences) without recourse to factual support. To implement the use of fallacies could be seen as a violation of Grice's first maxim for successful communication, the maxim of quality, which demands sincerity and truthfulness (if the system employs a rhetorical trick, it is in some ways 'cheating'), but since humans generally utilise fallacies unwittingly, there would appear to be no lack of sincerity unless there is devious intent behind their application. Their use would be heavily constrained by tight preconditions specifying contextual factors in addition to both system knowledge and assumed audience beliefs. (If the preconditions were to include some analysis of the hearer's susceptibility to the fallacy, it could then be argued that there is some measure of devious intent).

Finally, there are the inductive operators, which are of three types: inductive generalisation, causal (based on Mill's methods) and analogical. All three will have preconditions that are again tightly specified for context and belief, but with the additional constraint of the 'criteria of inductive strength', ie. the requirements for their application to produce an inductively strong argument.

3.4 Eloquence Generation

Although the EG level also employs a number of operators, the bulk of its functionality is based on the application of heuristics. The first task of the EG level is to control stylistic presentation, comprising much relatively low level fine-tuning such as the vocabulary range, syntactic construction (eg. the ratio of active to passive constructions) and the frequency of specific devices such as alliteration, repetition, metaphor and analogy. There are a large number of such factors detailed in the stylistic literature - see [10] for an overview. To date, such factors have been controlled by quite artificial and simplistic means, typically, the user setting a number of variables to particular values. For the instantiations to be made and altered 'on-the-fly', the EG level must refer to a body of parameters, in addition to the belief model of the audience and context, all of which are modified dynamically.

One vitally important parameter affecting the argument is the relationship which the speaker wishes to create or maintain with the hearer. This relationship is established through stylistic rather than structural means, and is not necessarily divorced from other aims: if a hearer accepts the speaker's authoritative stance, for example, the speaker may be able to use the relationship to reinforce his statements. Attempts at instigating different relationships between speaker and hearer account (at least in part) for a number of complex phenomena - humour, for example, is frequently used to establish the speaker as a friend (and therefore reliable and truthful). Such phenomena are not intended to fall inside the scope of this work.

The technical and general competence of the hearer are also important parameters to be considered at the outset. General competence determines the hearer's ability to understand complex argumentation (and to some extent, complex grammar); technical competence enables the argument to pitched at the right level, and affects the choice of appropriate vocabulary.

The initial goals of the argument are also best viewed as a parameter: as mentioned above, the primary goal in different situations (debating house, soap box, law courts, etc.) is subtly different: convincing an opponent is probably the most usual goal, but arguments are also used to impress, to instruct, to confound, to counter, to deceive and to provoke. Importantly, there are often several concurrent goals, such that a number of goal-dependent heuristics could be active at any one stage. Many of the EG level's suggestions are affected - vocabulary, grammar, gross structure and content all depend, to some extent, upon the system’s goals.

A number of other parameters have also been identified, including the speaker's potential gain from 'winning' the argument (and the speaker's gain as perceived by the hearer), the speaker's investment, or potential losses, suffered in losing the argument, the medium in which the argument is expressed and aspects of the speaker's model of the hearer's beliefs such as possible scepticism or bias. For example, advertisements usually have the aim of convincing the hearer to buy the product. In addition though, there are aims connected with the product identity, the particular advertising campaign, and often the speaker-hearer relationship. An attempt is frequently made to hide or play down the speaker's involvement and gain, whilst very careful analysis is made of the audience at which the advertisement is aimed, and the consequent weaknesses and beliefs of that audience.

Some of the EG heuristics are much less dependent upon these parameters: those aiding in the premise-conclusion ordering, for example, rely almost entirely upon general principles (though do also make use of factors such as the general tone of the argument). There are three possible statement orderings in an argument: Conclusion-First (C P*), Conclusion-Last (P* C), and Conclusion-Sandwich (P* C P*). The first is usually used where the P* are examples (in the case of factual conclusions: for opinions, the P* would often be analogies), especially when the hearer is being led to a hasty generalisation from the P* to the C. Conclusion-First is also used when the initial conclusion is deliberately provocative -the construction being used to draw attention to the argument (and consequently it is unusual to find a weak argument structured with the Conclusion-First ordering). It can also be forced should a premise not be accepted by the hearer, and require a sub-argument in its support. Conclusion-Last is the usual choice for longer, more complex or less convincing arguments (indeed some arguments are less convincing precisely because they are longer or more complex). It is also used for 'thin end of the wedge' argument and for grouping together premises which individually lend only very weak support to the conclusion. The Conclusion-Sandwich construction is rarer, usually occurring when the speaker has completed a Conclusion-Last argument which has not been accepted and therefore requires further support.

Finally, there are a number of features controlled by the EG level which lie somewhere between the stylistic and the rhetoric: repetition and alliteration, for example, can prove extremely effective in constructing eloquent and compelling argument. It is interesting to note that almost all of EG heuristics are devices listed by classical texts as figures and tropes. Indeed this is a uniquely interesting property of the EG level: the emphasis it puts in utilisation of ideas posited in precomputational treatises,

especially the classical texts of Cicero and Aristotle ([4], for example) and the ideas developed in the late middle ages and renaissance (the nineteenth century texts [12] and [2] have been used as source material for much of the analysis). This fact poses unique challenges as well as affording unique advantages: on the one hand, the ideas are clear and unbiased, whilst on the other, may be difficult to transcribe to implementation. The EG level should not be seen in a purely augmenting role - it is responsible for the production of an argument which is compelling and effective (for a human audience), and it is for this reason that the texts mentioned above are seen as being of vital importance.

3.5 Intention

One of the key functions of both the AS and EG levels is to maintain a representation of the intention behind utterances. RST has been widely criticised for its restrictive handling of intention [8], [14], thus the AS and EG levels have to manipulate rather different data structures from those employed at lower levels (which would appear quite reasonable, given the difference in data structures at the RST level compared with lower levels). At the highest level of abstraction, intentions form goals employed in the planning process. This is a similar approach to that of [8], which views intentions as communicative goals (and, similarly, there are also some goals which are not intention-laden - these correspond to linguistic goals). The planning of the next level also uses intentions in this way, but in addition, intentions effect longer-term control with a much wider scope by taking on the parameter-like role of maintenance goals (as distinct from fulfillable achievement goals). Importantly, the abstraction-based planning enables any operator in the plan, regardless of its hierarchical position, to be justified (or explained, or replanned) using the intention(s) which motivated it.

In order to fully address the questions of intention driven rhetoric mentioned in this and preceding sections, the current work is concentrating specifically on the higher, more abstract functionality. The remaining, lower level functionality required to realise the abstract intentional structures into natural language utterances will be provided by a system such as LOLITA [11], a large scale, domain independent natural language system, in which a natural language generation algorithm is already implemented which subsumes responsibility for solving certain low-level text generation planning problems.

3.6 Interaction

It is intended that the system should be fully interactive, and enter into dynamic natural language dialogue with a human interlocutor. There are a number of issues specific to this goal, most obviously, the differences between monologue and dialogue. Both monologue and dialogue require belief modelling of the audience (at the very least for argument, and quite possibly for all natural language); during production of a monologue however, no opportunity is presented for checking, revising and refining the audience model, which makes extended arguments simpler to construct (with no need to modify the plan according to new information regarding the beliefs of the hearer), but as a consequence, rather less likely to succeed at convincing a hearer of the proposition in hand. Work on monologue-formed argument would probably be easier to tackle in the short term, but it ignores many critical aspects of modelling which are of longer term interest, in particular, in monologue the classical planning assumptions of perfect knowledge of effects and environment state can be employed, while with dialogue it is necessary to consider the problems of uncertainty, imperfect knowledge (and the need to acquire knowledge) and plan failure.

During true dialogue, then, competent belief revision is essential. This revision process is nontrivial and forms an important part of the functioning of the AS and EG levels, drawing in particular from the work of Gardenfors and Galliers, [5], for implementation.

Dialogue also affords an opportunity for the application of argument to the areas in which it is most useful: negotiation and conflict resolution (where the interlocutors may not already be disposed to helping one another). The literature details much work on negotiatory communication (eg. [15], which emphasises conflict resolution in non-cooperative domains). Much of this work has assumed agent-agent communication, whereas in this paper it is proposed that a similar approach could be adopted in modelling natural language human-computer interaction, in situations in which user and system have differing goals.

4 CONCLUSION

This paper has presented an outline of the architecture required for constructing extended arguments from the highest level of pragmatic, intention-rich goals to a string of utterances, using a core hierarchical planner employing structural and rhetorical operators and heuristics. The proposed architecture is the first clear framework which presents a computational view of the rhetorical means used by humans to create cogent argument.

Work is currently underway to characterise the parameters and operators involved in the early stages of argument synthesis, and in particular, a careful analysis is being performed of the role of intentions in the planning process. The architecture proposed will facilitate implementation of an HCI system capable of dealing with situations in which its own goals conflict with those of the user, or in which persuading the user to adopt new beliefs is a nontrivial task, whose success cannot be guaranteed.

5 BIBLIOGRAPHY

[1] Ackermann, R.J. (1972) Belief and Knowledge, Anchor, New York

[2] Blair, H. (1838) Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres, Charles Daly

[3] Fox, M. & Long., D. (1995) "Hierarchical Planning using Abstraction",

IEE Proceedings on Control Theory and Applications

[4] Freese, J.H. (trans), Aristotle (1926) The Art of Rhetoric, Heinmann

[5] Galliers, J.R. (1992) ''Autonomous belief revision and communication''

in Gardenfors, P., (ed), Belief Revision, Cambridge University Press, pp220-246

[6] Hovy, E. H. (1993) "Automated Discourse Generation Using Discourse

Structure Relations", Artificial Intelligence63, pp341-385

[7] Mann, W.C., Thompson, S.A. (1986) ''Rhetorical structure theory'' in

Kempen, G., (ed), Natural Language Generation, Kluwer, pp279-300 [8] Moore, J.D., Pollack, M.E. (1992) ''A Problem for RST: The Need for

Multi-Level Discourse Analysis'', Comp. Ling.18 (4), pp537-544

[9] Sacerdoti, E.D. (1977) A Structure for Plans and Behaviour, Elsevier

[10]Sandell, R. (1977) Linguistic Style and Persuasion, Academic Press

[11]Smith, M.H., Garigliano, R. & Morgan, R.C. (1994) ''Generation in the

LOLITA system'' in Proc.7th Intl. Workshop on NLG, Kennebunkport

[12]Whately, R. (1855) Logic, Richard Griffin, London

[13]Wilson, B.A. (1980) Anatomy of Argument, University Press America

[14]Young, R.M., Moore, J.D. (1994) ''DPOCL'' in Proc. 7th Intl.

Workshop on NLG, Kennebunkport, Maine, pp13-20

[15]Zlotkin, G. & Rosenchein, J.S. (1990) "Negotiation and Conflict

Resolution in Non-Cooperative Domains", Proc. AAAI’90, pp100-105

成语使用常见错误类型

成语使用常见错误类型 (一)、望文生义 例如:在浦东国际机场边检大厅,有这样一位服务标兵,她无论出现在哪里,脸上始终挂着一抹微笑,真诚、甜美、亲切,让人难以释怀。(2010山东卷) “释怀”指(爱憎、悲喜、思念)很难在心中消除。此处说的是“真诚、甜美、亲切”,应改用“让人难以忘怀”。这里误解词语 (二)、用错对象 例如:上届冠军挪威队以全胜战绩出线,表现十分出色,其卫冕雄心及雄厚实力令人刮目相看。(2010江西卷) “刮目相看”,指别人已有进步,不能再用老眼光去看。这里用错对象。 (三)、褒贬不当

例:现在我们单位职工上下班或步行、或骑车,为的是倡导绿色、低碳生活。尤为可喜的是,始作俑者是我们新来的局长。(2010全国Ⅰ) 褒贬色彩失当。“俑”,指古代殉葬用的木制或陶制的俑人。“始作俑者”,开始制作俑的人,比喻首先做某件坏事的人。此处贬词褒用。 (四)、语义重复 例:在飞驰的高速列车上,人们津津乐道地谈论着乘坐高铁出行带来的快捷 与方便。(2010湖南卷) “津津乐道地谈论着”不妥,很明显“津津乐道”已经包含了“说”这一动作,后面再接“谈论”语意重复,改为“兴致勃勃”比较好。 (五)、不合语境 例如:近年来,在种种灾害面前,各级政府防患未然,及时启动应急预案,力

争把人民的生命财产损失降到最低限度。(2010江苏卷) “防患未然”用于灾难没有发生之前。不合语境。 (六)、两栖词语 有些成语有两种或两种以上的含义,两种或两种以上的感情色彩,这称为词语的“两栖现象”。要判断成语运用正确与否,需用它的多个含义和色彩去斟酌。 例:生命的价值在于厚度而不在于长度,在于奉献而不在于获取……院士的一番话入木三分,让我们深受教育。(2010江苏卷) “入木三分”,形容书法有力,也用来比喻议论深刻。这里使用恰当。

persuasive paper(说服性文章)

Student Can’t Cook in the Dormitory Every day, many students are talking about that students whether be allowed to cooking in the dormitory or not. In many colleges, there exist the phenomena that many student cooking in the dormitory. But for their own benefit, they shouldn’t. First of all, cooking can only use electricity in the dorm. Under that condition will consume large amounts of electricity, and it will cost a lot of money. The fee will be borne by the school. School, of course, is not willing to spend much more money, so schools will prohibit students cooking in the dorm. Next, there are a lot of students in the dormitory, including a lot of things such as books, clothes, etc. So the security hidden danger is especially serious. In particular, some old buildings’ fire control facilities have been aging. If an electronic leakage or burning takes place in the old dorm unluckily will result in serious consequences. And it is difficult for the crowd to withdraw from the scene on time lead to the situation that it is hard to control the accident quickly, will inevitably cause enormous life and property losses. Finally, the tragedy has occurred before, should deserves everybody’s attention. A few years ago there was a girl cooking in the dormitory and caused a fire, and let the whole room burning. The girls of whole room jumped off the balcony for life but they all failed and died. From what have been discussed, it is necessary to stop and prevent students from cooking in the dorm.

成语使用错误常见类型资料讲解

七上成语运用 一、成语使用常见错误类型 对策一:吃透词义,多识记多积累成语的意蕴是约定俗成的,而且许多源自典故,加之有些成语中的语素还含有生僻的古义,这就造成了成语理解上的难度。如果不仔细辨析,一瞥而过,就容易造成望文生义的错误。 有些成语的理解能够利用“先分析后综合”的方法进行,如“巧夺天工”,主谓结构,“夺”,胜过,“天工”,天然的精巧,那么“巧”必然不能是天然的了。例题: 1、有的同学学作文,文不加点,字迹潦草,阅读这样的文章,真叫人头疼。(╳) 【解析】“文不加点”常被错误理解为写文章不加标点符号,其实它的真实含义是形容写文章很快,不用涂改就写成(点:涂上一点,表示删去) 2、这部精彩的电视剧播出时,人们在家里守着荧屏,几乎万人空巷,街上静悄悄的。(╳) 【解析】“万人空巷”是指家家户户的人都从巷子里出来了,形容庆祝、欢迎等盛况。不能按照字面意思理解为家家户户都在屋内,巷子里空了。 对策二:平时注意成语的使用对象有些成语有特定的使用对象,如果把握不准,就容易扩大使用范围或误作他用。例题: 1、博物馆里保存着大量有艺术价值的石刻作品,上面的各种花鸟虫兽、人物形象栩栩如生,美轮美奂。 【解析】“美轮美奂” “轮”是“高大”的意思“奂”是“众多”的意思,适用的对象应是高大的建筑物而非人物形象。 2、宽敞明亮的教室里,72名同学济济一堂,畅谈着美好的理想。 【解析】“济济一堂”特指人才。(形容很多有才能的人聚集在一起。)「备注」: “感同身受”指替蒙受恩惠的人向施恩者表示答谢,不用于受恩惠者本人。 “相濡以沫”用于患难中,不用于平时。 “炙手可热”用于人有权势,而不用于物。 “崭露头角”多指青少年。 “萍水相逢”用于陌生人初次见面。 “浩如烟海”是形容文献、资料非常丰富。

成语使用中常见错误类型以及对策

成语使用中常见错误类型以及对策 (一)误解词语,望文生义 成语的意蕴是约定俗成的,而且许多源自典故,加之有些成语中的语素还含有生僻的古义,这就造成了成语理解上的难度。如果不仔细辨析,一瞥而过,就容易造成望文生义的错误 (二)用错对象,张冠李戴 有些成语有特定的使用对象,如果把握不准,就容易扩大使用范围或误作他用。 (三)色彩失当,语境不分 成语从色彩上分为感情色彩、语体色彩和谦敬色彩。从感情色彩上又可分为褒义、中性、贬义;从语体色彩上分为书面语和口语;从谦敬色彩上分为谦辞和敬辞。在使用中,必须辨明色彩,否则就会误用。(四)语义重复,自相矛盾 虽然成语在句子中的意思是准确的,但还要防止与句中其他词语意义重复或矛盾 (五)搭配不当,不合习惯 有些成语还应该注意它的词性用法以及它的词义轻重与语境是否协调。 1、下列句子中,加点成语运用不恰当的一句是() A、这一段时期,“非典”似乎已销声匿迹,但是医学专家反复提醒,这种疾病可能只是暂时消失,很可能会卷士重来。 B、一直以来,对网吧的治理很难取得显著成效。这样无形中助长了一些违法经营者的嚣张气焰,对国家的规定更加熟视无睹。 C、叶圣陶先生说,苏州园林是我国各地园林的标本。去年到苏州游览了几个园林,果然觉得名正言顺。 D、刘慧卿因参与“台独”分子研讨会,并发表支持“台独”的言论,连日遭到社会各界人士的口诛笔伐。 2、选出加点成语运用不正确的一项是( ) A、五月的油城,鲜花盛开,姹紫嫣红,十分绚丽。 B、日本厚生省政务官森冈正宏公然称日本二战甲级战犯“在日本国内已经不是罪人”,如此信口雌黄,实在令人吃惊。 C、有个别学生上网成瘾,执迷不悟,浪费了大好年华。 D、高速公路上,南来北往的汽车滔滔不绝。 3、下列句中加点成语使用不正确的一项是()

我的人生演讲稿大全

我的人生演讲稿1 水烧到99℃不算开,最后只要再加热1℃,就能突破物理形态的临界线,从液态变为气态。 走完了99步,人们都说最后一步最难迈,最难走。其实这最后一步和99 步的每一步,没有什么两样,只是人们在迈这一步时自己吓唬自己,容易放弃,不去坚持罢了。无论做什么事,只要敢于坚持,决不放弃,那些不可能的事,也会变为可能。 10年前,我在《环球》杂志上读过一个很感人的真实故事。故事的主人公是个年轻貌美的女子,一天,跟随丈夫在山顶拍照,突然丈夫一脚踩空,随即向万丈深渊滑去,周围是陡峭的山崖,两手无任何抓处。就在这十分危急的一瞬间,妻子两手抱住崖边的树干,用嘴咬住了丈夫的上衣。这时丈夫悬在空中,妻子又不能松手,只好用两排洁白细碎的牙齿承受着一个高大的身躯。妻子不停地对自己说:“咬紧牙关,坚持,再坚持!”她美丽的牙齿和嘴唇被血染得鲜红鲜红。半个小时后,被游客发现,才把他俩救上来。这位妻子身单力薄,为什么会在紧要关头,爆发出这么大的承受力和忍耐力?一位生理学家认为:“身体机能对紧急状况产生反应时,肾上腺能大量分泌出激素,传到整个身体,能产生额外的力量。”如果从心理方面分析,这种生理现象,产生于人的心智和精神的力量。这位妻子能咬紧牙关,一再坚持,是因为她心里只有一个念头:千万千万不能松口,否则丈夫就会跌进万丈深渊。人有了心智和精神力量的支配,就连死神也怕咬紧牙关! 要问成功有什么秘诀,丘吉尔在剑桥大学讲演时回答得很好:“我的成功秘诀有三个:第一是,决不放弃;第二是,决不,决不放弃;第三是,决不,决不,决不放弃。” 决不放弃,就是坚持,它来自于人的毅力。毅力是人类最可贵的财富,在走向成功的路上,没有任何东西能代替毅力。热情不能,有一时热情的人往往在最后一步退缩,这已屡见不鲜;聪明也代替不了毅力,因为世上失败的聪明人太多了。

Persuasive Techniques Handout

Persuasion Persuasion: Writing that attempts to get an audience to make a VOLUNTARY CHANGE. Your topic should be one of some importance, not just personal preference. Audience: Those who disagree with you or who are at least undecided on the issue. 2 Big Persuasive Concerns (from Aristotle) Logos(Facts and opinions based on facts) Ethos (The reader’s perception of the writer: Writers need to present themselves as knowledgeable and fair people. Are the sources of the writer’s knowledge clear and dependable? Is the author fair to the other side? Does the author pay attention to opponents’ objections?) 8 Persuasive Techniques Must do to be effective 1. Have a clear thesis: Make it clear who you want to do what (part of logos) 2. Give reasons supported by facts to make your case. A fact is a statement that can be indisputably verified (logos) 3. Pay attention to your opponent's views: State the beliefs and feelings of the other side and the reasons why your audience doesn't want to change (ethos). 4. Respect the opponent: Keep your tone polite (ethos). Useful, but not absolutely essential 5. Seek common ground: Find things you can both agree on from the start (ethos) 6. Make concessions: Admit any weaknesses on your own side (ethos) 7. Seek compromise: Be willing to bend a little (ethos) 8. Use vivid examples: Try to move the emotions of your audience (Aristotle called this pathos) 2 Practices That Don't Persuade 1. Dishing out sarcasm and insults 2. Ignoring your opponent

成语使用错误常见类型

七上成语运用 令狐采学 一、成语使用常见错误类型 (一)误解词语,望文生义对策一:吃透词义,多识记多积累成语的意蕴是约定俗成的,而且许多源自典故,加之有些成语中的语素还含有生僻的古义,这就造成了成语理解上的难度。如果不仔细辨析,一瞥而过,就容易造成望文生义的错误。有些成语的理解能够利用“先分析后综合”的方法进行,如“巧夺天工”,主谓结构,“夺”,胜过,“天工”,天然的精巧,那么“巧”必然不能是天然的了。例题: 1、有的同学学作文,文不加点,字迹潦草,阅读这样的文章,真叫人头疼。(╳)【解析】“文不加点”常被错误理解为写文章不加标点符号,其实它的真实含义是形容写文章很快,不用涂改就写成(点:涂上一点,表示删去) 2、这部精彩的电视剧播出时,人们在家里守着荧屏,几乎万人空巷,街上静悄悄的。(╳) 【解析】“万人空巷”是指家家户户的人都从巷子里出来了,形容庆祝、欢迎等盛况。不能按照字面意思理解为家家户户都在屋内,巷子里空了。(二)用错对象,张冠李戴对策二:平时注意成语的使用对象有些成语有特定的使用对象,如果把握不准,就容易扩大使用范围或误作他用。例题: 1、博物馆里保存着大量有艺术价值的石刻作品,上面的各种花鸟虫兽、人物形象栩栩如生,美轮美奂。 【解析】“美轮美奂” “轮”是“高大”的意

思“奂”是“众多”的意思,适用的对象应是高大的建筑物而非人物形象。 2、宽敞明亮的教室里,72名同学济济一堂,畅谈着美好的理想。 【解析】“济济一堂”特指人才。(形容很多有才能的人聚集在一起。) 「备注」:“感同身受”指替蒙受恩惠的人向施恩者表示答谢,不用于受恩惠者本人。“相濡以沫”用于患难中,不用于平时。“炙手可热”用于人有权势,而不用于物。“崭露头角”多指青少年。“萍水相逢”用于陌生人初次见面。“浩如烟海”是形容文献、资料非常丰富。 “汗牛充栋” 形容藏书非常多。“豆蔻年华”指女子十三四岁时。 “慷慨解囊”用于帮助别人。 “天伦之乐”用于一家人。 (三)色彩失当,语境不分成语从色彩上分为感情色彩、语体色彩和谦敬色彩。从感彩上又可分为褒义、中性、贬义;从语体色彩上分为书面语和口语;从谦敬色彩上分为谦辞和敬辞。在使用中,必须辨明色彩,否则就会误用。 1、误用褒贬,情感错位对策三:注意感情色彩,辨明褒贬成语和有些词语一样是有感情色彩的,使用成语时,须要使成语的感情色彩和语境的色彩保持一致,语境褒则褒,语境贬则贬,中性语境则使用中性词。 (1)班里的不良现象已经蔚然成风,再不治理就会带来严重后果。 【解析】蔚然成风:指事情逐渐发展、盛行,形成一种好的风尚。在这里“不良现象”是贬义,使用“蔚然成风”不恰当(2)这些年轻的科学家决心以无所不为的勇气,克服重重困难,去探索大自然的奥秘。 【解析】无所不为:没有不做的事。指什么坏

演讲稿我的人生

演讲稿我的人生 篇一:我的人生演讲稿(李福义) 我的人生 亲爱的同学们: 大家好,我今天演讲的题目是:我的人生。 同学们,一艘轮船之所以能在浩瀚的海洋上远行,是因为有灯标为他指引方向。一个人在人生的道路上,也应该有一个远大的目标。所以,我的人生应该先确定一个目标,然后找到一个实现目标的方法。 远大志向可以陶冶一个人的情操。千百年来,多少仁人志士无不是先立大志而后成大器;又有多少凡夫俗子,碌碌无为,虚度年华。历史的见证告诉我们每一个人:“人无志则不立。” 我的人生理想:做一个能为国家,能为社会,能为家人做出贡献的人。但是,应该怎样去做呢?一、规定在什么时候采取什么方法步骤达到什么目标。使自己一步步地靠近小目标走向大目标;二、培养良好的生活、学习习惯,能自然而然地按照一定的秩序去努力。无论碰到什么困难挫折也要坚持完成计划,达到规定的目标;三、要找出每天学习和思考最佳的时间,如有的同学早晨头脑清醒,最适合于记忆和思考;有的则晚上学习效果更好。要在最佳时间里总结昨天完成的任务和学到的知识,然后再思考下一步的安排。

立志需要辛勤的汗水去浇灌,也需要努力的付出去滋润。“宝剑锋从磨砺出,梅花香自苦寒来。”所以能不能成功就看我们的志向的大小和付诸的实践如何了。” 我的人生掌握在自己手里。让我们珍惜时间,走好人生的每一步! 篇二:我的人生规划-演讲稿 我的人生规划 ――XX演讲比赛的冠军作品 导演张艺谋在陕北拍电影时见到一个孩童,夕阳西下骑在牛背上悠闲地哼着陕北小调,就问:“娃,你在干啥?”孩童很悠闲地答:“我在放牛!”“为啥放牛?”“放牛挣钱!”“挣钱干嘛?”“挣钱娶媳妇!”“娶媳妇干嘛?”“娶媳妇生娃!”“生娃干嘛?”“生娃放牛!”八岁的小男孩就这样规划好了他的人生:放牛—挣钱—娶媳妇—生娃再放牛。 我想!诸位同学来到这里一定不是想继续过着这种放牛—挣钱—娶媳妇—生娃再放牛的日子吧。 肯定不是!那么,我们就应该脱离这种祖祖辈辈的循环!规划属于我们自己的全新人生!所谓我的人生我来选择! 如何来选择并规划我们的人生呢? 规划人生必须有一个明确的志向! 古人云:有志之士立长志,无志之士常立志。没有明确志向的人常立志,常立志有什么不好呢?举个例子说吧!有

A_Persuasive_Speech_Sample

A Persuasive Speech Sample A. INTRODUCTION "Tells your audience what you are going to tell them" and establishes the foundation for your speech. A good Introduction 'draws the map' for the journey. For a Persuasive Speech an Introduction consists of 1. Attention-Getter: A statement, visual or sound (or combination)that startles, gains attention and makes your audience sit up.... Who here communicates with others? Today, I want to describe to you what I call the 8th Wonder of the World. This wonder is right up there with the Pyramids, with the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, with the Collossus of Rhodes. It is not though of the ancient world. It is though a marvel of engineering and cooperation amongst the nations of the world. Today as well as the telephone, I use the Internet, I use eMail. The Internet is a way of connecting computers together around the world using the telephone cables. eMail is electronic mail that is distributed across the Internet. Putting these together, I can almost communicate anywhere anytime. Did you know, that "the number of emails sent on an average day was approximately 10 billion in 2002 and by 2005, this amount is expect to triple to 35 billion emails sent each day" (Source: IDC news release, 'Email Deluge Continues With No End In Sight, IDC Says': October 10, 2000) Do you know that they are all asleep in Australia? Last year I rang to ask a business question to only get the night security guard. It was good of him to take my call. Now I email at any time and receive the needed information back as soon as the other office is open. 2. Bond > Link-to Audience: Identify a personal connection in the audiences' life, eg their use of the 'device' or system, or their emotional experience (grief and sorrow, happiness). How many here use the telephone to connect with another?

成语使用中常见错误类型以及对策

成语使用中常见错误类型以及对策(一)、误解词语,望文生义 成语的意蕴是约定俗成的,而且许多源自典故,加之有些成语中的语素还含有生僻的古义,这就造成了成语理解上的难度。如果不仔细辨析,一瞥而过,就容易造成望文生义的错误。 有些成语的理解能够利用“先分析后综合”的方法进行,如“巧夺天工”,主谓结构,“夺”,胜过,“天工”,天然的精巧,那么“巧”必然不能是天然的了。 例题: 1、就在公安部门准备收网时,这帮家伙为虎作伥,毫不收敛,在罪行簿上又添新笔。(╳) 2、这部精彩的电视剧播出时,人们在家里守着荧屏,几乎万人空巷,街上静悄悄的。(╳) 3、第二次世界大战时,德国展开了潜艇战,于是使用水声设备来寻找潜艇,成了同盟国要解决的首当其冲的问题。(╳)(首当其冲:首先受到攻击或遭受灾难) 4、这个小毛病不足为训,下次改掉就行了,何必大动干戈呢?(╳) 5、今年初上海鲜牛奶市场燃起竞相降价的烽火,销售价格甚至低于成本,这对消费者来说倒正好可以火中取栗。(╳)(火中取栗:受人利用,冒了风险,吃了苦头,却没得到好处) 6、北大荒虽然天荒地老,但经农垦战士的开发,已经成为商品粮基地。(╳)(天荒地老:指经过的时间很久)

7、我们应该向先进企业学习,起初可能是邯郸学步,但终究会走出自己的路来。 (邯郸学步:比喻生硬的模仿,不但学不到人家的本领,反而连自己原有的长处也丢掉了。) 8、“9·11”事件之后,美国股市势如破竹的下跌趋势,令世界经济雪上加霜。(╳) (势如破竹:比喻节节胜利,毫无阻碍) 9、美国政府在台湾问题上的危言危行,只能是搬起石头砸自己的脚。(╳) (危言危行:讲正直的话,做正直的事。) 10、全面提高学生素质,减轻学生负担,在社会上引起了轩然大波。(轩然大波:常用于比喻大的纠纷或风潮) 11、教育学生要讲究方式方法,不能总是耳提面命,摆家长作风。(╳) 12、作家不深入生活,坐在家里管窥蠡测,就创作不出群众喜欢的作品。(管窥蠡测:比喻对事物的观察了解片面狭隘,十分有限。应改为“闭门造车”) 对策一:吃透词义,多识记多积累 【备注】: A、鼎足之势三人成虎不为己甚目无全牛杯弓蛇影侧目而视叹为观止金瓯无缺细大不捐安土重迁坐地分赃差强人意一团和气别无长物大方之家

我的人生我做主演讲稿

篇一:我的人生我做主演讲稿 [我的生活我做主演讲稿] 在座的各位同学: 你们好,今天想必大家十分高心,因为此时此刻我们迎来了进入小学生活的第一次演讲,而对于我十分感谢大家可以在这里听我的演讲。 我的人生我做主。我们就应该趁着年轻,有志气,有勇气,有胆气,去拼,去闯,去搏。人生就如花儿一般。它总是在不同的季节里开放。如果所有的鲜花都在春天开放完毕了,到了夏天,秋天,冬天没有任何花朵开放,你还会觉得这个自然界是如此美丽吗?肯定不会。所以我们的人生应象夏荷的清香,秋菊的“城尽带黄金甲”,冬梅豪放的诗意。而我们的人生同样又象连绵不绝的山脉一样,犹如珠穆朗玛蜂,困难重重,总是有无数的高峰在眼前,需要我们去征服,而一旦我们登上高峰后,生命中无限的风光就会展现出来,整个世界都在你的眼皮底下。当然,攀登并不是一件轻而一举的事,你必须付出很多代价。然而这种代价都是值得的,如果你要去另一个山头,你必须从山底开始重新开始攀爬,因为没有任何两个山头是连在一起的。如果说山谷代表人生的低谷,而为攀爬到山顶所碰到的困难,痛苦和失败是不是都是你今后成功的基础呢?是的。越是碰到痛苦,挫折。如果你能坚定你的往往前走,你的人生必定你做主。当我们走向谷底,并且能爬到谷峰。当你回头再看的时候,必然会发现人生充满了起起伏伏的优美故事。这时,我们的人生充满了精彩,并且是炫目的。 人生里面总是有所缺少,你得到什么,也就失去什么。重要的是你应该知道自己到底要什么。追两只兔子的人,难免会一无所获。况且会失去更多。所以我们应当学会珍惜。 以上是我对人生的理解,并如何做到我的人生我做主。最后,在座的每一位,我衷心的希望大家。一个人只要时刻保持幸福的感觉,才会使自己更加热爱生命,热爱生活,只有快乐,愉快的心情,才是创造力和人生动力的源泉。只有不断自己创造快乐与快乐相处的人,才能远离痛苦与烦恼,才会拥有快乐的人生。而这个人必定是在座的每一位。 篇二:幸福小主人竞选演讲稿:我的人生我做主 幸福小主人竞选演讲稿:我的人生我做主 幸福小主人竞选演讲稿:我的人生我做主 敬爱的老师,亲爱的同伴们: 大家好! 在家庭中我是个“自立小主人”,一天天长大,我力所能及的事儿也越来越多:承担自己房间的卫生,定期整理小书架,起床后叠被子,饭前准备碗筷,中午回家拖一遍地,晚饭后刷碗,周末在爸爸妈妈指导下学做菜,等等。每一种体验都带给我不一样的感受:整个地面拖完后我会满头大汗,做饭的时候经常手忙脚乱,在做这些的时候我深深体会着爸爸妈妈对于我的成长所赋予的无私与辛劳,也希望自己的分担会让爸爸妈妈感到欣慰。对了,我还把自己做凉拌黄瓜的体验写成一篇文章《“金钩香脆块”诞生记》,发表在《少先队活动》杂志上,收

高考成语常见错误类型

高考成语常见错误类型 Document number:WTWYT-WYWY-BTGTT-YTTYU-2018GT

第三节成语 第一部分成语误用分析 辨别成语使用正误的考题,这几年的高考语文试题中每年都有。由于学生平时对词语掌握得不够好,失分率很高。为解决这个难点,现把成语误用的情况进行具体的分析并附上练习,以供师生参考。 1、不明词义而误 例一: (1)、这部精彩的电视剧播出时,几乎万人空巷,人们在家里守着荧屏,街上静悄悄的。(1997年全国试题) (2)、家用电器降价刺激了市民消费欲的增长,原本趋于滞销的彩电,现在一下子成了炙手可热的商品。(1999年全国试题) (3)、我本就对那里的情况不熟悉,你却应派我去,这不是差强人意吗(1993年试题) (4)、第二次世界大战时,德国展开了潜艇战,于是使用水声设备来寻找潜艇,成了同盟国要解决的首当其冲的问题。(1995年全国试题) 分析:(1)中的“万人空巷”意思是众多人都从胡同里跑出来,多用来形容庆祝、欢迎等盛况.(2)中“炙手可热”是说手一接近就觉得热,比喻气焰很盛,权势很大.(3)中“差强人意”意思是稍微适合人的心意。(4)中“首当其冲”意思是首先受到冲击或伤害。这四个成语的意思都与该句句意不和,这种错误都是不明词义造成的。 2、不明色彩而误 例二: (1)齐白石画展在美术馆开幕了,国画研究院的画家竞相观摩,艺术爱好者也趋之若鹜。(1997全国试题) (2)为了救活这家濒临倒闭的工厂,新上任的厂领导积极开展市场调查,狠抓产品质量和开发,真可谓处心积虑。(1998全国试题) (3)这些年轻的科学家决心以无所不为的勇气,克服重重困难,去探索大自然的奥秘。(1995全国试题) (4)这家伙明知罪行严重,但却从容不迫地在抹桌子,好象啥事也没有发生。(模拟试题) 分析:(1)中的“趋之若骛”比喻许多人争着去追逐不好的事物,(2)中的“处心积虑”指千方百计地盘算(干坏事),(3)中的“无所不为”是说啥坏事都能干得出来,(4)中的“从容不迫”形容非常镇静、不慌不忙的样子。前三个词都用于贬义,与句意不和;后一个词用于褒义,也与句意不和:它们在该句中的使用都是错误的。这些使用的错误都是不明色彩而造成的。 3、不合逻辑而误 例三: (1)翘首西望,海面托着的是披着银发的苍山。苍山如屏,洱海如镜,真是巧夺天工。(1992 全国试题)

我的人生观演讲稿

我的人生观演讲稿 每个人都有自己的人生观,那么大家对于人生观的理解是怎样的呢?以下是小编收集的相关演讲稿,仅供大家阅读参考! 我的人生观演讲稿一各位…..(称呼) 大家好! 一个人满怀希望和激情,热爱生活,珍视生命,勇敢坚强地战胜困难并不断开拓人生新境界,其背后一定有一种正确的人生观作为精神支柱。现在,我以我的亲身经历,从四个方面去阐述我的人生观。 人生须认真。我以认真的态度对待人生,明确生活目标和肩负责任,既清醒地看待生活,又积极认真地面对生活。我在工作生活中正确地认识和处理人生遇到的各种问题,,对自己负责,对家庭负责,对国家和生活负责,自觉承担起自己应尽的责任,满眶热情地投入生活、学习和工作中。身为一名护士,六年来,我一直在自己的岗位上兢兢业业,一心一意为人民服务,时时处处为人民着想,助人为乐,造福人民,时刻惦记着病人,为他们排忧解难,给他们无微不至的关怀。 人生当务实。我自己从人生的实际出发,以科学的态度看待人生,以务实的精神创造人生,以求真务实的作风做好每一件事。我把远大的理想寓于具体的行动中,我虽然中专毕业,但我理想远大,勇攀高峰,函授了本科,向着更广阔

的人生目标迈进!就这样,我要从小事做起,从身边事做起,脚踏实地、一步一个脚印地实现人生目标。 人生应乐观。我乐观向上、热爱生活、对人生充满自信。许多事情不会总是紧如人意,但要始终保持乐观向上的人生态度,不能因为没有满足自己的期望或者遇到困难和挫折,就消极悲观、畏难退缩。我个人性格比较开朗、善良、简单、多才多艺,经常参加单位举办的各种活动,比如舞蹈、唱歌、排球等等。我在陶冶情操的同时,还如期地收获了爱情。要相信生活是美好的,前途是光明的,遇到事情要想得开做人要心胸开达,优化性格,热爱生命,乐观向上。 人生要进取。人生实践是一个创造的过程。我要以开拓进取的态度迎接人生的各种挑战,不断领悟美好的人生真谛,体验生活的快乐和幸福。还要积极进取,不断丰富人生的意义。我要始终保持蓬勃朝气、昂扬锐气,充分发挥生命的创造力、为社会做贡献中提升生命价值,在创造中书写人生的灿烂篇章! 在今后,我继续以饱满的热情,高昂的斗志,积极的心态投入到日常学习工作中,去书写更辉煌的人生,去开创更美好的未来! 我的演讲到此结束,谢谢大家。 我的人生观演讲稿二各位领导、各位老师: 下午好,我已将近不惑之年,说年轻也不年轻,说老又

成语运用中的十大错误类型

成语运用中的十大错误类型 第一类望文生义第二类对象误用 第三类褒贬颠倒第四类语义轻重的误用 第五类语境不合第六类形义相近的误用 第七类多重含义的误用第八类表意重复 第九类语法功能的误用第十类谦敬错位 第一类望文生义 1.明日黄花:比喻过时的事物或消息。 2.火中取栗:比喻被别人利用去干冒险事,付出了代价而得不到好处。 3.万人空巷:形容庆祝、欢迎等盛况。 4.不刊之论:指正确的不可修改的言论。 5.不为已甚:指对人的责备或责罚要适可而止。 6.望洋兴叹:比喻做事时因力不胜任或没有条件而感到无可奈何。 7.不足为训:不值得作为效法的准则或榜样。 8.因人成事:依靠别人把事情办好。 9.升堂入室:比喻学问或技能由浅入深,循序渐进,达到了高深的地步。 10. 不名一文:名:指占有。形容穷到极点,连一文钱也没有。 11.久假不归:长期地借用,不归还。 12.司马青衫:比喻因遭遇相似而表示的同情。 13.数典忘祖:比喻忘掉自己本来的情况或事物的本源。 14.大动干戈:比喻大张声势地行事。 15.高山流水:比喻知己、知音或乐曲高妙。 16.不绝如缕:形容局势危急或声音细微悠长。 17.不翼而飞:比喻东西突然丢失。 18. 首当其冲:比喻最先受到冲击、压力、攻击,或遭受灾难。 19.别无长cháng物:长物:多余的东西。除一身之外再没有多余的东西。原指生活俭朴。现形容人贫穷。 20.进退维谷:形容进退两难。 21.如坐春风:比喻得到教益或感化。 22.春风化雨:比喻良好的教育 23.间不容发:形容情势极其危急。 24.祸起萧墙:指祸乱从内部发生。 25.炙手可热:形容权势大,气焰盛,使人不敢接近。 26.一衣带水:指虽有江河湖海相隔,但距离不远,不足以成为交往的阻碍。

我的人生演讲稿3篇

我的人生演讲稿3篇 人生要进取。 我的人生演讲稿一尊敬的各位评委、来宾,亲爱的同学们:大家好!我演讲的题目是《彩绘职业蓝图,塑造完美人生》。 我的演讲完毕,谢谢大家! 我的人生演讲稿二老师们、同学们: 大家好! 一个人满怀希望和激情,热爱生活,珍视生命,勇敢坚强地战胜困难并不断开拓人生新境界,其背后一定有一种正确的人生观作为精神支柱。就这样,我要从小事做起,从身边事做起,脚踏实地、一步一个脚印地实现人生目标。 在今后,我继续以饱满的热情,高昂的斗志,积极的心态投入到日常学习工作中,去书写更辉煌的人生,去开创更美好的未来! 我的演讲到此结束,谢谢大家。 我的人生演讲稿三人生就是活的一种方式,就是生活,在每个人考虑自己的生活时,其实我也在考虑自己的生活方式,找录属于自己的人生。 虽然我不知道自己能走多远,但我知道我已经走过了十多年的人生历程。在过去的一段路程中,我也经历了很多很多生活中大小琐事,甚至比常人多了几分坎坷和痛苦,但我也明白了很多人生的哲理。生命随时在流逝,就在笔尖滑动时,我的生命也在伴随着这一滑动在一秒一秒地流逝,这是不可抗据的事情,我唯一能做的就是找寻自

己的人生。 时光的车轮向前滚动,社会的发展日新月异,而我也在长大,心灵也在长大,世间万物都在变,唯一不变的是我的信念,我的理想。 人生并不好找寻,它对我来说有时是一种无形的生活方式,处于虚幻和缥缈之间,有时又分外清晰,似乎伸手可及。于是我迷茫了,我害怕了,慌乱无措了,我不知道该怎么办才好。 直到有一天,一觉醒来突然发现我已经十五岁了,十五岁是美好的青春时期,我们并没有什么压力,只有那永不衰竭的青春动力和活力,我们早已充满力量的电流,等待我们的是放手一搏,创造辉煌,顷刻间,我发现我有激情了,有思想了,有目标了。我找回了自己,找回了属于自己的人生,虽然无法言明,但我的理智告诉我。它就是我要找的人生。继而一种力量催逼着我走上属于自己的人生道路。 我终于明白,找回自己,尽自己的努力做到尽己完美,也就找到了自己的人生。

中学考试常见成语使用错误归类

中考常见成语使用错误归类!! 成语误用原因分析之一:张冠李戴 每个成语都有共适用范围和对象,若使用不当,张冠李戴,就要闹出笑话。 1、翘首西望,海面托着的就是披着银发的苍山。苍山如屏,洱海如镜,真是巧夺开工。(“巧夺开工”用于描述人工制作的东西,对象错) 2、博物馆里保存着大量有艺术价值的石刻作品,上面的各种花鸟虫兽,人物形象栩栩如生,美轮美奂。 3、她终于认识了自己,战胜了自我。在新的学年里,她德智体美劳全面发展,并驾齐驱,被评为优秀学生干部。(“并驾齐驱”用来陈述两个或两个以上的对象,范围错) 4、他呀,做起事来可麻利了,无论做什么都倚马可待。(“倚马可待”特指人的文思敏捷,范围错) 5、突然,一个影子如白驹过隙般地一闪而过,快捷如飞。(“白驹过隙”比喻时间过得很快,对象错) 6、三月的呼伦贝尔大草原草长莺飞,春光迷人。(“草长莺飞”是形容江南春色的词语,对象错) 7、公园里摆放的各种盆栽菊花,姹紫嫣红,微风一吹,更是风姿绰约。(“风姿绰约”形容女子姿态优美,对象错)。 8、文章生动细致的描写了小麻雀的外形、动作和神情,在叙述、描写和议论中,倾注着强烈的感情,读来楚楚动人,有很强的感染力。

(“楚楚动人”是形容女人打扮光鲜,姿态娇柔,能打动人。对象错)9、他从小就喜欢画画,常在纸上信笔涂鸦,现在他画的鸟已是栩栩如生。(“信笔涂鸦”是指写字,不是画画,范围错) 10 这对老朋友分别了近半个世纪,没想到这次居然大街上萍水相逢,于是站在路边畅谈起来。(“萍水相逢”比喻素不相识的人偶然相遇。用该成语形容老朋友相遇属对象误用。) 成语误用原因分析之二:望文生义 有些成语的意蕴是约定俗成的,我们看到某一不明含义的成语,如果只从字面上去附会,就极易出现望文生义的毛病,作出错误的或片面的解释。 1、这部精彩的电视剧播出时,几乎万人空巷,人们在家里守着荧屏,街上显得静悄悄的。(“万人空巷”是说人们都从巷子里出来到大街上,多形容庆祝、欢迎等盛况;本句从语势上看,要表述的是人们闭门不出在家里欣赏电视剧) 2、成都五牛俱乐部一二三线球队请的主教练及外援都是清一色的德国人,其雄厚财务令其他甲B球队望其项背。(“望其项背”是“能够望见脖子和背,表示赶得上比得上”,此当作“只能望见项背,形容差得远”来理解了。) 3、第二次世界大战时,德国展开了潜艇战,于是使用水声设备来寻找潜艇,成为同盟国要解决的首当其冲的问题。(“首当其冲”比例

我的人生演讲稿作文800字5篇

我的人生演讲稿作文800字5篇 不论你的人生似戏,似梦或似曲,参与的人,永远都不止你一个,当有很多人参与了,也会有人逐渐离开,悲伤是必然的,然而也不必过于惶恐,人生,靠的是一个过程,贪的是一个信念,也应该做到:记住该记住的,忘记该忘记的,改变能改变的,接受不能改变的。下面给大家分享一些关于我的人生演讲稿作文800字5篇,供大家参考。 我的人生演讲稿作文800字(1) 敬爱的教师,亲爱的同学: 大家好: 沉湎与文字,只是把梦想堆砌,无边的思绪在指尖流溢,挥洒出朵朵心莲。眷顾的年华,藏在夜里细细咀嚼,随意铺叙,在浅浅岁月流光之中,铭刻一段心音。 写过的信笺迹痕,或多或少会被时间遗忘,被心搁置,如同一些人,一些事,但我却始终如一,最自在勇敢的,依然是那云卷云舒,素心素笔,自乐安然。风淡,旧寒依依,一念舍得,一念放下,一切尤自心定。有了离意,懂了心思,便用时间矫正思想,用守望迎接虔诚。 人生三态:生存,生活,生命。每种状态,或多或少都被繁华与喧嚣的现实所影响,所纠结。有的人徘徊着,有的人困惑着,有的人一如往昔继续着悠悠生活。无论是哪种状态,在人生不断抵达的过程中,只要清醒就行,只要宁静就好,只要希望在心就好。于此一生,似曾相识,却又是与众不同。这一世,不可代替,不可复制,不可重新来过。独一无二的人生华年,每一季节都是有颜色的,既已知晓,那就好好充实自己的生活。 时光轻转,流年翩然,几重岁月,微笑浅淡。我知道,这一切状况与心绪有关。

曾经的执念,是不懈坚持,渴望生花之妙随心而舞,在指尖落定。所谓永远,到底有多远?重山之外,念意悠悠,漂泊零落又添悲凉,何以为期? 本来静心,却又忧心。一笺心语一生梦,怎奈,这丝丝寂寞,冷暖红尘,都在指尖。人生四季,多少情感辗转,相遇、别离,美好、悲凉,冷冷暖暖,只如云烟。多少忧伤,在指尖下流走,划满了心酸。是否,思索太多,会觉得迷惘?是否,执念过深,会觉得心累? 这一半春花,一半秋月,一半明媚,一半忧伤,一半喧嚣,一半沉寂。生活总是这样跌宕起伏,此生彼长,来来往往,看似无常,却是有常。它没有我们想象中的那样美,也没有想象中的那样差,我们不也每天都矛盾地向前走吗?人活一世,不仅仅是来过,有所留念过,而是要没有白来,没白活,没白过。活出了自己所喜欢的方式风格,就是最好的活法。 我的人生演讲稿作文800字(2) 尊敬的老师,亲爱的同学: 大家下午好: 念一些人,写一方字,温一壶山水,我期盼着有一日,也能够拥抱暖阳,轻轻地聆听一草一木低语,只愿安静些,再安静一些。有些记忆在心底轻轻打捞,仿佛于眼前,就可以细细斟酌一句一字,如此随性随心,如此简简单单。归于本真,素心素颜,素笺素笔,安之若素。走进淡泊,走进心灵宁静,如此静静煮一壶静好,与心底潺潺对酌,与岁月对语,如此想来甚好! 然繁华三千,众生芸芸,谁可逃脱岁月如流的洗涤,谁可跳跃七情六欲的侵蚀,终也是在婆娑之中牵强起舞,晨暮依旧,而过往悄然行走于光阴一旁,一左一右,以一种节奏渐行渐远。听风数雨的日子,有人懂得便好。