Genetics,Cytogenetics,and Epigenetics of Colorectal Cancer

?20

08

L

a n

d e

s

B

i o

s c i

e n

c e . D o

n o t

d

i s

t r

i b

u t e .

[Epigenetics 3:4, 193-198; July/August 2008]; ?2008 Landes Bioscience

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the most common cancer in non-smokers posing a significant health burden in the UK. Observational studies lend support to the impact of environmental factors especially diet on colorectal carcinogenesis. Significant advances have been made in understanding the biology of CRC carcinogenesis in particular epigenetic modifications such as DNA methylation. DNA methylation is thought to occur at least as commonly as inactivation of tumor suppressor genes. In fact compared with other human cancers, promoter gene methylation occurs most commonly within the gastrointestinal tract. Emerging data suggest the direct influence of certain micronutrients for example folic acid, selenium as well as interaction with toxins such as alcohol on DNA methylation. Such interactions are likely to have a mechanistic impact on CRC carcinogenesis through the methylation pathway but also, may offer possible therapeutic potential as nutraceuticals.

Introduction

In the UK, colorectal carcinoma (CRC) is the most common gastrointestinal tract malignancy with almost 30,000 new cases diag-nosed per annum and an average 40% five year survival although in some parts of Europe and United States this approaches 60%.1-4 This difference has been attributed in part due to variation in stage of presentation of the disease. Globally, the majority of cases occur in developed countries, particularly North America and Western Europe 5 with a world wide annual mortality of 600,000.2 Since the change to a Western dietary pattern in Japan, the incidence and mortality rates of CRC have increased markedly.6 Observational studies lend support to the influence of environmental factors which demonstrate an increase of colorectal cancer in migrants from low to high-risk countries, compared to age and sex matched controls.7 Geographical variation of CRC between east and west may also partly be explained by local customs—one such example is

consumption of green tea. This popular beverage in the Far East has been shown in murine models to possess anti-carcinogenic proper-ties.8 The importance of environmental exposure (especially diet) is further highlighted by the fact that only a small proportion of cancers can be attributed to germ line mutations. Doll and Peto 9 in 1981 initially concluded that diet caused cancer in up to 70% of the population in the USA and other industrialised countries. However a more realistic and generally accepted figure is probably up to a third in the variance of cancer incidence between populations can be attributed to habitual variation in diet, as highlighted in the recent World Cancer Research Fund report (WCRF/AICR 2007).10

Hence, this review is timely and will endeavour to examine the exisiting literature and summarize the influence of common dietary intakes such as alcohol, folate, selenium, green tea and phytoestro-gens on CRC risk with particular emphasis on mechanisms related to DNA methylation. These dietary substrates (alcohol, folate and selenium) were chosen as they have been shown in epidemiological studies to be associated with colon cancer.32-32,52,60 Although the role of phytoestrogens and green tea 51 in cancer prevention remains controversial, these substrates nevertheless represent proof of prin-ciple of dietary factors influencing DNA methylation. In addition, we introduce a novel concept of the ‘Methylation Health and Carcinogenesis pendulum model’ and the role of diet in maintaining this equilibrium.

DNA Methylation and Colorectal Cancer (CRC)

Epigenetic alterations (genetic alterations that do not alter the DNA sequence) such as DNA methylation, are among the most common molecular alterations in human cancers including colorectal cancer.11 The addition of a methyl group to the carbon-5 position of cytosine residue is the only common covalent modification of human DNA.12 It occurs almost exclusively at cytosines that are followed immediately by guanine (CpG dinucleotides). The majority of the genome displays a depletion of CpG dinucleotides and those that are present are nearly always methylated. Conversely, small stretches of DNA known as CpG islands (usually located within the promoter regions of human genes), whilst rich in CpG dinucleotides, are nearly always free of methylation. It is this methylation within the islands that has been shown to be associated with transcriptional inactivation of the corresponding gene.13 The methylation patterns are controlled by DNA methyltransferases (DNMT) as well as CpG

Review

A review of dietary factors and its influence on DNA methylation in colorectal carcinogenesis

R.P . Arasaradnam,1-3,* D.M. Commane,1 D. Bradburn 2 and J.C. Mathers 1

1Human Nutrition Research Centre; School of Clinical Medical Sciences; Newcastle University; Newcastle UK; 2Department of Surgery; Northumbria Healthcare NHS Trust;

Northumberland, United Kingdom; 3University Hospital Coventry & Warwick; Coventry UK

Key words: DNA methylation, colorectal cancer, diet, nutraceuticals, alcohol, folate, selenium

*Correspondence to: R.P . Arasaradnam; Newcastle University; Human Nutrition Research Centre 8; John St.; Coalville, Leicestershire LE67 8L UK; Email: r.p.arasaradnam@https://www.360docs.net/doc/8b12500540.html,

Submitted: 05/01/08; Accepted: 06/26/08

Previously published online as an Epigenetics E-publication:

https://www.360docs.net/doc/8b12500540.html,/journals/epigenetics/article/6508

?20

08

L

a n

d e

s B

i o

s c i

e n

c e . D o

n o t

d

i s

t r

i b

u t e .

methyl binding proteins (MBD), the latter of which is involved in ‘reading’ methylation marks.13,14

In CRC, as with other tumors, loss of genomic methylation is a frequent early event and correlates with disease severity and metastatic potential.15 Likewise, aberrant promoter hypermethylation which usually occurs at CpG islands is also thought to be an early event in CRC as it is detect-able in early precursor lesions.16 Feinberg and Vogelstein were the first to report changes in DNA hypomethylation in tumors compared with normal tissue.17 However, this concept was further complicated by the observation that most cancer types have both global hypomethylation and hyper-methylation in the gene promoter regions.17-19 Hypermethylation in promoter regions is associ-ated with transcriptional silencing which is at least as common as inactivation of tumor suppressor genes through DNA mutations.20,21 Virtually all pathways in colorectal carcinogenesis, for example loss of control of cell cycle regulation (p16INK4a , p14ARF ), silencing of DNA mismatch repair genes (MLH1, O 6-MGMT ), possible loss of function of apoptosis genes (DAPK, APAF-1) and altered carcinogen metabolism (GSTP1) involves promoter gene hypermethylation.22-24 Global hypomethyla-tion which has been observed in both colorectal cancer and adenomas 25,26 is thought to be able to induce regional de novo hypermethylation 27 as well as expression of oncogenes.28 However, there is still paucity of evidence to suggest a ‘cross talk’ between global and promoter gene methylation and it is likely that these events are independent of each other.

The ‘Methylation Equilibrium’ Concept

Unlike germ line mutations (which are heritable from one cell to its daughter), epigenetic changes such as DNA methylation are potentially reversible. Because gene expression can be re-established by demethylation of promoter regions,29 this offers the opportu-nity for the role of diet in cancer prevention. Hence any imbalance

between promoter hypermethylation and global hypometylation may potentially be reversed in order to achieve ‘normal’ methylation patterns i.e., ‘methylation equilibrium status’. In other words, it is plausible that the genome default methylation status is to maintain normal methylation patterns and thus gene expression, which, in disease is subsequently altered. We hypothesize that certain dietary factors may contribute directly to this equilibrium by preventing or encouraging either promoter hyper or global hypomethylation. This is in essence an extension of the ‘Health Pendulum’ concept.30 The Health Pendulum concept simply states that an individual can shift from the normal healthy state to a disease state as a result of external

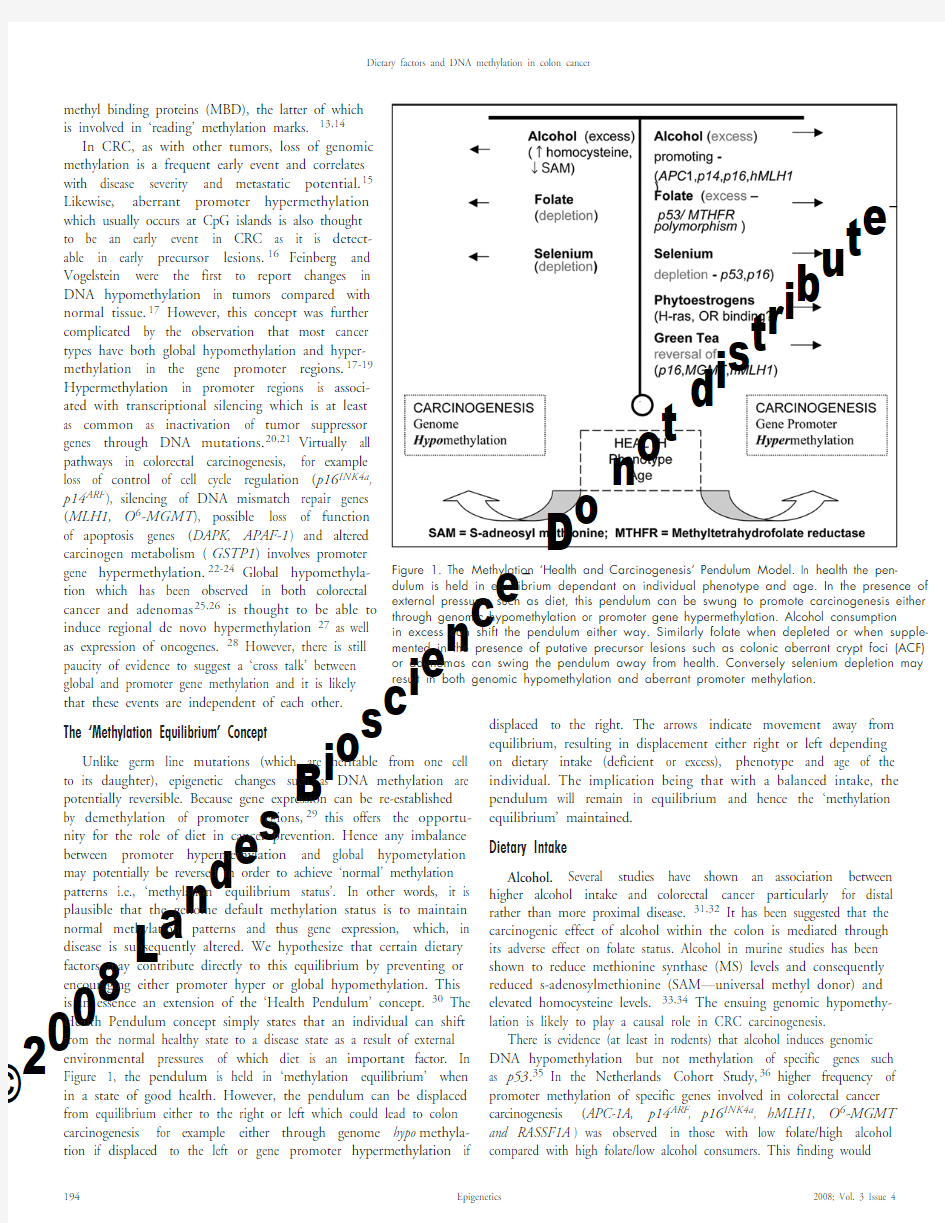

environmental pressures of which diet is an important factor. In Figure 1, the pendulum is held in ‘methylation equilibrium’ when in a state of good health. However, the pendulum can be displaced from equilibrium either to the right or left which could lead to colon carcinogenesis for example either through genome hypo methyla-tion if displaced to the left or gene promoter hypermethylation if displaced to the right. The arrows indicate movement away from equilibrium, resulting in displacement either right or left depending

on dietary intake (deficient or excess), phenotype and age of the individual. The implication being that with a balanced intake, the pendulum will remain in equilibrium and hence the ‘methylation equilibrium’ maintained.Dietary Intake Alcohol. Several studies have shown an association between higher alcohol intake and colorectal cancer particularly for distal rather than more proximal disease.31,32 It has been suggested that the carcinogenic effect of alcohol within the colon is mediated through its adverse effect on folate status. Alcohol in murine studies has been shown to reduce methionine synthase (MS) levels and consequently reduced s-adenosylmethionine (SAM—universal methyl donor) and elevated homocysteine levels.33,34 The ensuing genomic hypomethy-lation is likely to play a causal role in CRC carcinogenesis.

There is evidence (at least in rodents) that alcohol induces genomic DNA hypomethylation but not methylation of specific genes such as p53.35 In the Netherlands Cohort Study,36 higher frequency of promoter methylation of specific genes involved in colorectal cancer carcinogenesis (APC-1A, p14ARF , p16INK4a , hMLH1, O 6-MGMT and RASSF1A ) was observed in those with low folate/high alcohol compared with high folate/low alcohol consumers. This finding would

Figure 1. The Methylation ‘Health and Carcinogenesis’ Pendulum Model. In health the pen-dulum is held in equilibrium dependant on individual phenotype and age. In the presence of external pressures such as diet, this pendulum can be swung to promote carcinogenesis either through genomic hypomethylation or promoter gene hypermethylation. Alcohol consumption in excess can shift the pendulum either way. Similarly folate when depleted or when supple-mented in the presence of putative precursor lesions such as colonic aberrant crypt foci (ACF) or adenomas can swing the pendulum away from health. Conversely selenium depletion may result in both genomic hypomethylation and aberrant promoter methylation.

?20

08

L

a n

d e

s B

i o

s c i

e n

c e . D o

n o t

d

i s

t r

i b

u t e .

suggest that the mechanistic link between high alcohol intake and increased CRC risk seems to be mediated through low folate status.Phytoestrogens. Phytoestrogens which include coumestans, isoflavones and lignans are plant derived oestrogen-like compounds. They are naturally occurring in many foods including fruits, legumes such as soy and rice.37 Phytoestrogens have several biological actions including anti-oestrogenic, anti-inflammatory and anti-carcinogenic effects.38,39

In vitro studies have suggested that phytoestrogens antagonise 17β-oestrodiol and compete for binding to oestrogen receptor (OR).40,41 CRC risk is known to be influenced by oestrogen expo-sure although the specific mechanism remains unknown.42 The ESR gene (oestrogen receptor gene) shows age related methylation and is methylated in colorectal adenoma 43 and sporadic colorectal neoplasia,44 suggesting that ESR methylation may predispose to colorectal neoplasia. In cell line studies, aberrant hypermethylation of the promoter region of the ESR gene has been shown to result in transcriptional silencing.45 Hence no OR will be available for binding thereby increasing overall circulating oestrogen levels and cancer risk. Clearly phytoestrogens will not have any beneficial effects once ESR gene is hypermethylated and it may be that its beneficial effects occur prior to ESR gene methylation. In rodents a proposed protec-tive mechanism of phytoestrogens has been promoter methylation of H-ras proto-oncogenes, although interestingly, no methylation was observed in either c-myc or c-fos proto-oncogenes.46 Whilst the bioavailability for these individual compounds is low, consump-tion in combination with other polyphenols, and possibly histone deacetylase inhibitors, may produce an enhanced effect on DNA methylation.47 Suffice to say current evidence would suggest that the protective role of phytoestrogens are heterogeneous, depending on target tissue 48 with little evidence to support direct influence on DNA methylation at least in the colonic epithelium.

Tea. Green tea, which is a popular beverage particularly in the Far East, has been shown in murine models to possess anti-carcinogenic properties.8 The major (polyphenol) ingredient, (-) epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) is a potent inhibitor of catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) activity.49 Both COMT and DNA methyl transferase (DNMT) belong to the same family of SAM dependant methyltransferases. Inhibition of DNMT by certain drugs such as 5-aza-deoxycytidine has been shown in mice to inhibit cancer growth, induce apoptosis and reduce tumor volume.50

In an in vitro experiment using HT 29 cells, (where molecular modelling was used to show that EGCG fits into the catalytic pocket of DNMT1) prevention of carcinogenesis is through competitive inhibition of DNMT1.51 The authors also showed resultant reversal of methylation in p16INK4a (tumor suppressor gene), retinoic acid receptor (RARB ), O 6-methylguanine methyltransferase (MGMT ) and hMLH1 genes. Thus green tea (EGCG) may inhibit DNMT causing CpG demethylation and reactivation of previously methyla-tion silenced genes. Moreover, high concentrations of EGCG are not required, 20 micromol being sufficient, which can be achieved in saliva and stomach. EGCG thus provides a good example of a food component with the capacity for reversal of aberrant methylation—at least in vitro.

Selenium. Interest in selenium and cancer prevention stemmed from early population based studies noting an inverse relationship between selenium status and carcinogenesis in particular colon

cancer in geographical areas where selenium was low in soil.52 The large Nutritional Prevention of Cancer T rial,53 which was a randomised double blind placebo controlled interventional trial provides the strongest evidence for the protective effect of selenium against colorectal cancer. Skin cancer was the primary focus of the trial and effects on CRC were secondary outcomes. The dose of selenium used was 200 mcg/day in the form of a yeast supplement. After a follow-up of 8,271 person years, the relative risk for all cancers in those supplemented with selenium was 0.5 with signifi-cant protection against CRC, lung and prostate.

Selenium is an essential trace element with both antioxidant and pro-apoptotic properties.54 In human fibroblasts, selenium in the form of Selenomethionine has also been shown to induce DNA repair.55 Other mechanisms whereby selenium deficiency may promote carcinogenesis can be seen in both cell culture (caco-2 cells) and animal studies. Both have demonstrated that in the colon, selenium deficiency causes global hypo methylation and in addition, promoter methylation of p53 and p16 genes.56 In addition, selenium supplementation has shown marked reduction in the number of aberrant crypt foci in the colon.57 In human colon cancer, selenium (sodium selenite) has been shown in to play a role in chemopre-vention by inhibiting DNA Methyltransferase (DNMT), thereby suppressing aberrant DNA methylation.58 Of note most studies have used selenomethionine as it is the major component of Se-enriched foods and has non-toxic properties.

Folic acid. Until recently, folate has been one of the nutrients most strongly implicated in terms of protection against CRC. An inverse relationship between folate intake and risk of colorectal adenoma was demonstrated in the Health Professionals Follow-Up study and in the Nurses Health study where the relative risk of adenomas was 0.66 for women and 0.63 for men in those with a higher intake of folate.59 Similarly in a review of 11 case control and cohort studies, a 40% risk reduction of CRC was seen in the highest consumers of folate.60 Conversely, recent results from the Polyp Prevention Group 61 has shown no reduction (RR 1.13 at 3–5 years follow up) in risk of adenoma recurrence with folic acid supplemen-tation (1 mg/day) even in susceptible individuals (low baseline folate status and those that consumed alcohol). Folate through its role in the one carbon metabolism is crucial for both DNA synthesis as well as methylation. Potential mechanisms for folate deficiency mediated carcinogenesis include (1) DNA damage 62 (uracil misincorporation), (2) increased cell proliferation,63 (3) aberrant global or promoter methylation,64 (4) MTHFR polymorphisms 65 and (5) possibly DNMT inhibition.66

Aberrant global and site specific methylation. In rodents, folate deficiency protects against whilst supplementation increases risk of development of cancer.67 Results from studies on the effect of folate deficiency on DNA methylation status are inconsistent, with some showing hypo methylation,68 no change 69 or hyper methylation.70 In the APC min mouse model, folate deficiency resulted in lower S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) levels—universal methyl donor, without affecting genomic DNA methylation status.66 Moreover, the effects of folate supplementation were less clear.71-73 In a recent randomised, double blind, placebo controlled intervention study of 31 patients with adenomatous polyps, Pufulete et al.74 has shown that supplementation with physiological amounts of folic acid (400 mcg/day) over a ten week period increased genomic DNA methylation in

?20

08

L

a n

d e

s B

i o

s c i

e n

c e . D o

n o t

d

i s

t r

i b

u t e .

both leucocytes (significantly) and rectal mucosa (non-significantly) with an accompanying fall (significant) in plasma homocysteine. The validity of measuring methylation status in the leucocyte as a surrogate marker of methylation within the colono-cyte remains unknown. Methylation status within rectal mucosa has been shown to be increased in patients with colorectal adenoma 75-76 and CRC 77 when supplemented with high doses of folate (5–10 mg/day) over 3–6 months. In the study by

Kim et al.76 however, both groups (patients with adenomas and placebo) showed an increase in rectal mucosa DNA methylation at one year. The above studies have used varying doses of folic acid over varying time courses with methylation measured

in different tissues which may explain the inconsistencies observed. Furthermore, in the aged, altered colonic physiology may mean inconsistent response to folate such that beneficial effects of folate are lost even when folate status is replete.73,78 Thus there is a fine balance

between preventing and promoting carcinogenesis depending on folate status—Figure 2.DNA methyltransferase (DNMT). The role of DNMT in partic-ular DNMT1, in promoting CRC in the presence of folate deficiency remains inconclusive. This enzyme is critical in catalysing methyla-tion reactions of cytosine residues in DNA. Thus deficiency of this enzyme would be expected to alter methylation status. However, T rasler et al.66 have shown that in the APC min mouse model, folate deficiency in the presence of DNMT deficiency reduced tumor load but had no effect on global genomic DNA methylation or promoter methylation of two specific genes (p53 and E-cadhedrin ; p53 unlike E-cadhedrin is normally methylated at the promoter region in CRC tumorogenesis). Furthermore, the observation of reduced tumor load in the presence of folate deficiency was noted only after the devel-opment of adenomas in this model.79 No effect on tumor load was

noted if the amount of folate in the diet was altered prior to develop-ment of adenomas.

Whilst this study is supportive of tumor load reduction in the

presence of folate and DNMT1 deficiency, it does not support

the hypothesis that the sole mechanism is through its effects on

DNMT1. In fact studies with DNMT1 gene knock out models have

shown that it is still possible to obtain a viable offspring suggesting

that other DNMTs (DNMT3a or 3b) play a role in de novo methyla-tion crucial for development.80Issues surrounding folic acid and its effect on methylation and

colorectal carcinogenesis remain complex. Folate seems to act as

a double edged sword; protective against initiation of carcinogen-esis 60,64,68,71,81-83 but also promoting carcinogenesis, for example, increase in mortality from breast cancer during pregnancy with folate supplementation.84 The way we consider alterations in folate status within colonocytes and its effect on carcinogenesis may also be important. For example, alteration in folate form and distribution (qualitative alterations) in relation to certain geno-types might be more informative than total folate concentrations

(quantitative changes) alone.

85Conclusions Genotypic differences will naturally result in variable individual benefits from certain nutrients. The aged hypothesis of the protective effect of fruits and vegetables against CRC through their anti-oxidant properties and induction of apoptosis is clearly not the whole story. Epigenetic mechanisms are well defined in CRC carcino-genesis 11,16-18,22-26 and dietary intake of common nutrients have been shown to alter this.52,57,72-75 Thus, diet may act as a form of chemoprevention to influence DNA methylation status. Moreover, a balanced nutrient intake may contribute directly to maintaining the ‘methylation equilibrium’ by preventing either promoter hyper or global hypo methylation (Fig. 1). Clearly, effects of nutrient status cannot be defined based on its effects on genomic DNA methylation alone but rather taking into consideration the individuals genotype,

age, tissue specificity and critically in the colon, anatomical site (e.g.,

proximal vs. distal colon).

It is not clear however as to ideal duration of exposure of these

dietary components to affect DNA methylation status or the optimal

dose of these compounds required to exert a chemopreventitive

effect. Current evidence has not identified a unified mechanistic link

between diet and DNA methylation in CRC carcinogenesis which,

may simply reflect the heterogeneous nature of such substrates.

Future Work The impact of certain micronutrients on DNA methylation adds to our current understanding of possible mechanisms of how diet is linked with colorectal cancer. However, the specific mechanistic effects of diet on DNA methylation requires further study for example, the effect on promoter methylation of tumor suppressor genes and alteration in transcript levels of DNMT1,3a and 3b by varying concentrations of a particular micronutrient. Once these mechanisms

Figure 2. The proposed ‘see saw’ schematic illustrates the fine balance prevention and promotion of carcino-genesis. Known factors such as genotype, duration of exposure to folate, ageing and folate status (in box) can

slide one way or the other thereby either preventing carcinogenesis (through increasing nucleotide synthesis)

or promoting carcinogenesis through (global or aberrant promoter methylation). The presence or absence of putative pre-cancerous lesions such as aberrant crypt foci (ACF) may act as the fulcrum forcing the ‘box’ to slide one way or the other.

?20

08

L

a n

d e

s B

i o

s c i

e n

c e . D o

n o t

d

i s

t r

i b

u t e .

have been elucidated, the next step would be human interventional trials using these substrates as nutraceuticals. Subsequent findings would then result in a paradigm shift moving us into an era of targeted modification of methylation patterns using diet.

References

1. Office of Population Censuses and Surveys. Cancer Statistics Registration 1989. England

and Wales. London: HMSO 1994; series MBI; No 22.

2. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en/. World Health Organisation Cancer

Statistics (February 2006).

3. NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York. Effective Health Care: The

management of colorectal cancer. Financial Times Healthcare 1997; 3:1-12.

4. A summary of the colorectal cancer screening workshops and background papers. National

Screening Committee London: Department of Health 1998.

5. Koba I, Yoshida S, Fujii T , Hosokawa K, Park SH, Ohtsu A, Oda Y, Muro K, Tajiri H,

Hasebe T. Diagnostic findings in endoscopic screening of superficial colorectal neoplasia: results from a prospective study. Jpn J Clin Oncol 1998; 28:542-5.

6. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures. American Cancer Society 1995.

7. McMichael AJ, Giles GG. Cancer in migrants to Australia: extending the descriptive epide-miological data. Cancer Res 1988; 48:751-6.

8. Yang CS, Maliakal P and Meng X. Inhibition of carcinogenesis by tea. Ann Rev Pharmacol

T oxicol 2002; 42:25-54.

9. Doll R and Peto R. The causes of cancer: quantitative estimates of avoidable risks of cancer

in the United States today. J Natl Cancer Inst 1981; 66:1191-308.

10. World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute of Cancer Research. Food, Nutrition and

the Prevention of Cancer: A Global Perspective. Washington, DC: World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute of Cancer Research 2007.

11. Bird A. DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory. Genes Dev 2002; 16:6-21. 12. Bird A. CpG rich islands and the function of DNA methylation. Nature 1986; 321:209-13. 13. Robertson KD. DNA methylation and chromatin—unravelling the tangled web. Oncogene

2002; 21:5361-79.

14. Hendrich B and T weedle S. The methyl CpG binding domain and the evolving role of

DNA methylation in animals. T rends Genet 2003; 19:269-77.

15. Widschwendfer M, Jiong G, Woods C, Muller MH, Fiegl H, Goebel G, Muller-Holzner E,

Zeimet AG, Laird PW , et al. DNA hypomethylation and ovarian cancer biology. Cancer Res 2004; 64:4472-80.

16. Chan AO, Broaddus RR, Houlihan PS, Issa JP , Hamilton SR, Rashid A. CpG island methy-lation in aberrant crypt foci of the colorectum. Am J Pathol 2002; 160:1823-30.

17. Feinberg AP , Vogelstein B. Hypomethylation distinguishes genes of some human cancers

from their normal counterparts. Nature 1983; 301:89-92.

18. Baylin SB, Herman JG, Graff JR, Vertino PM, Issa JP . Alterations in DNA Methylation: a

fundamental aspect of neoplasia. Adv Cancer Res 2001; 72:141-96.

19. Jones PA, Baylin SB. The fundamental role of epigenetic events in cancer. Nat Rev Genet

2002; 3:415-28.

20. Tsou JA, Hagen JA, Carpenter CL, Laird-Offringa IA. DNA Methylation analysis: a power-ful new tool for lung cancer diagnosis. Oncogene 2002; 21:5460-1.

21. Costello JF , Plass C. Methylation matters. J Med Genet 2001; 38:285-303.

22. Esteller M. CpG island hypermethylation and tumor suppressor genes: a booming present,

a brighter future. Oncogene 2002; 21:5427-40.

23. Dang DT, Chen F , Kohli M, Rago C, Cummins JM, Dang LH. Glutathione S-T ransferase

1 promotes tumorigenicity in HCT116 Human Colon Cancer Cells. Cancer Res 2005; 65:9485-94.

24. Bai HC, Joanna HM, Tong KFM, Chan WY, Ellen PS, Man KWLJ, Lee JHY, Sung WK.

Promoter hypermethylation of tumor-related genes in the progression of colorectal neopla-sia. Int J Cancer 2004; 112:846-53.

25. Goelz SE, Vogelstein B, Hamilton SR, Feinberg AP . Hypomethylation of DNA from benign

and malignant human colon neoplasms. Science 1985; 228:187-90.

26. Feinberg AP , Gehrke CW , Kuo KC, Ehrlich M. Reduced genomic 5-methylcytosine content

in human colonic neoplasia. Cancer Res 1988; 48:11159-61.

27. Sharrard RM, Royds JA, Rogers S, Shorthouse AJ. Patterns of methylation of the c-myc

gene in hima colorectal cancer progression. Br J Cancer 1992; 65:667-72.

28. Laird PW . The power and promise of DNA methylation markers. Nature Rev Cancer 2003;

3:253-66.

29. Robertson KD. DNA methylation and Human Disease. Nature Reviews Genet 2005;

6:597-609.

30. Mathers JC. Pulses and carcinogenesis: potential for the prevention of colon, breast and

other cancers. Br J Nutr 2002; 88:273-27.

31. Pederson G, Johansen C, Gronbaek M. Relations between amount and type of alcohol and

colon and rectal cancer in a Danish population based cohort study. Gut 2003; 52:861-67. 32. Stemmermann GN, Normura AMY, Choyou OH, Yoshizawa C. Prospective study of alco-hol intake and large bowel cancer. Dig Dis Sci 1990; 35:1414-20.

33. Barak AJ, Beckenhauer HC, T uma DJ, Badakhsh S. Effects of prolonged ethanol feeding on

methionine metabolism in rat liver. Biochem Cell Biol 1987; 65:230-3.

34. T rimble KC, Molloy AM, Scott JM, Weir DG. The effect of ethanol on one-carbon metabo-lism: increased methionine catabolism and lipotrope methyl-group wastage. Hepatology 1983; 18:984-9.

35. Choi SW, Stickel F , Baik HW, Kim YI, Seitz HK, Mason JB. Chronic alcohol consumption

induces genomic but not p53 specific DNA Hypomethylation in rat colon. J Nutr 1999; 129:1945-50.

36. van England M, Weijenberg MP , Roemen GMJM, Brink M, de Bruine AP , Goldbohm RA,

van den Brandt PA, Baylin SB, de Goejj AF , Herman JG. Effects of Folate and Alcohol in take on Promoter Methylation in Sporadic Colorectal Cancer: The Netherlands Cohort Study on Diet and Cancer. Cancer Res 2003; 63:3133-7.

37. Garreau B, Vallette G, Aldercreutz H, Wahala K, Makela T, Benassayag C, Nunez EA.

Phytoestrogens: New Ligands for rat and human a fetoprotein. Biochem Bophys Acta 1991; 1094:339-45.

38. Aldercreutz H, Mousavi Y, Clark J, Hockerstedt K, Hamalainen E, Wakala K, Makela T,

Hase T. Dietary Phytoestrogens and cancer: In vitro and in vivo studies. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 1992; 41:331-7.

39. Dijsselbloem N, Vanden Berghe W, De Naeyer A, Haegeman G. Soy isoflavone phytochem-icals in IL-6 affections. Multipurpose nutraceuticals at the crossroads of hormone replace-ment, anti-cancer and anti-inflammatory therapy. Biochem Pharmacol 2004; 68:1171-85. 40. Barkhem T, Carlsson B, Nilsson Y, Enmark E, Gustaffson JA, Nilsson S. Differential

response of oestrogen receptor α and oestrogen receptor β to partial oestrogen agonists/antagonists. Mol Pharmacol 1998; 54:105-12.

41. Morito K, Aomori T, Hirose T, Kinjo J, Hasegawa J, Ogawa S, Inoue S, Muramatsu M,

Masamune Y. Interaction of phytoestrogens with oestrogen receptors α and β (11). Biol Pharm Bull 2002; 25:48-52.

42. Di Leo A, Messa C, Cavallinni A, Linsalata M. Oestrogen and colorectal cancer. Curr Drug

Targets Immune Endocr Metabol Disord 2001; 1:1-12.

43. Woodson K, Weisenberger DJ, Campan M, Laird PW, Tangrea J, Johnson LL, Schatzkin A,

Lanza E. Gene-specific methylation and subsequent risk of colorectal adenomas among par-ticipants of the polyp prevention trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers 2005; 14:1219-23. 44. Issa JP , Ottavino YL, Celano P , Hamilton SR, Davidson NE, Baylin SB. Methylation of the

oestrogen receptor CpG island links ageing and neoplasia in human colon. Nat Genet 1994; 7:536-40.

45. Ottaviano YL, Issa JP , Parl FF , Smith HS, Baylin SB, Davidson NE. Methylation of the

oestrogen receptor gene CpG island marks loss of oestrogen receptor expression in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res 1994; 1:2445-555.

46. Lyn-Cook BD, Blann E, Payne PW, Bo J, Sheehan D, Medlock K. Methylation profile and

amplification of proto-oncogenes in rat pancreas induced phytoestrogens. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1995; 208:116-9.

47. Fang M, Chen D, Yang CS. Dietary Polyphenols may affect DNA methylation. J Nutr

2007; 137:223-8.

48. Shenouda NS, Zhou C, Browning JD, Ansell PJ, Sakla MS, Lubahn DB, MacDonald RS.

Phytoestrogens in common herbs regulate prostate cancer cell growth in vitro. Nutr Cancer 2004; 49:200-8.

49. Lu H, Meng X, Li C, Patten C, Sheng S, Hong J, Bai N, Winik B, Ho CT, Yang CS.

Glucoronides of tea catechins: enzymology of biosynthesis and biological activities. Drug Metab Dispos 2003; 31:452-61.

50. Christman JK. 5-Azacytidine and 5-aza deoxycytidine as inhibitors of DNA methylation:

mechanistic studies and their implications of cancer therapy. Oncogene 2002; 21:5483-95. 51. Fang MZ, Wang Y, Ai N, Hou Z, Sun Y, Lu H, Welsh W, Yang CS. Tea polyphenol (-)

epigallocatechin-3-Gallate inhibits DNA methyltransferase and reactivates methylation silenced genes in cancer cell lines. Cancer Res 2003; 63:7563-70.

52. Clark LC, Cantor KP , Allaway WH. Selenium in forage crops and cancer mortality in US

countries. Environ Health 1991; 46:37-42.

53. Clark LC, Combs GF Jr, T urnbull BW, Slate EH, Chalker DK, Chow J, Davis LS, Glover RA,

Graham GF , Gross EG, et al. Effects of selenium supplementation for cancer prevention in patients with carcinoma of skin. A randomised controlled trial. Nutritional Prevention of Cancer Study Group. JAMA 1996; 276:1957-63.

54. Johnson IT. Mechanisms and anticarcinogenic effects of diet-related apoptosis in the intes-tinal mucosa. Nutr Res Rev 2001; 14:229-56.

55. Seo YR, Sweeney C, Smith ML. Selenomethionine induction of DNA repair in human

fibroblasts. Oncogene 2002; 21:3663-9.

56. Davis CD, Uthus EO, Finley JW. Dietary selenium and arsenic affect DNA methylation in

vitro in Caco-2 cells and in vivo in rat liver and colon. J Nutr 2000; 130:2903-09.

57. Baines AT, Holubec H, Basye JL, Thorne P , Bhattacharyya AK, Spallholz J, Shriver B, Cui H,

Roe D, Clark LC, et al. The effects of dietary selenomethionine on polyamines and azoxymethane-induced aberrant crypts. Cancer Lett 2000; 160:193-8.

58. Fiala ES, Staretz ME, Pandya GA, El-Bayoumy K, Hamilton SR. Inhibition of DNA

cytosine methyltransferase by chemopreventitive selenium compounds, determined by an improved assay for DNA cytosine methyltransferase and DNA cytosine methylation. Carcinogenesis 1998; 19:597-604.

59. Giovannucci E, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Rimm EB, T richopoulos D, Rosner BA, Speizer FE,

Willett WC. Folate, methionine and alcohol intake and risk of colorectal adenoma. JNCI 1993; 85:875-84.

60. Giovannucci E. Epidemiologic studies of folate and colorectal neoplasia: a review. J Nutr

2002; 132:2350-5.

61. Cole BF , Baron JA, Sandler RS, Haile RW , Ahnen DJ, Bresalier RS, McKeown-Evssen G,

Summers RW , Rothstein RI, Burke CA, et al. Polyp prevention study group. Folic acid for the prevention of colorectal adenomas: a randomised clinical trial. JAMA 2007; 297:2351-9.

?20

08

L

a n

d e

s B

i o

s c i

e n

c e . D o

n o t

d

i s

t r

i b

u t e .

62. Duthie SJ, Narayanan S, Blum S, Pirie L, Brand GM. Folate deficiency in vitro induces

uracil misincorporation, DNA hypomethylation and inhibits DNA excision repair in immortalised normal human colon epithelial cells. Nutr Cancer 2000; 37:127-33.

63. Nensey YM, Arlow FL, Majumdar APN. Ageing increased responsiveness of colorectal

mucosa to carcinogen stimulation and protective role of folic acid. Dig Dis Sci 1995; 40:396-401.

64. Kim YI. Folate and DNA methylation: A mechanistic link between folate deficiency and

colorectal cancer? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2004; 13:511-9.

65. Crott JW , Mashiyama ST , Ames BN, Fenech MF . Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase

C677T polymorphism does not alter folic acid deficiency induced uracil misincorporation into human lymphocytes DNA in vitro. Carcinogenesis 2001; 22:1019-25.

66. T rasler J, Deng L, Melnyk S, Pogribny I, Hiou-Tim F , Sibani S, Oakes C, Li E, James SJ,

Rozen R. Impact of DNMT1 deficiency with and without low folate diets on tumor num-bers and DNA methylation in Min mice. Carcinogenesis 2003; 24:39-45.

67. Kim YI. Folate: a magic bullet or double edged sword for colorectal cancer prevention. Gut

2006; 55:1387-9.

68. Balaghi M, Wagner C. DNA methylation in folate deficiency: use of CpG methylase.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1993; 193:1184-90.

69. Kim YI, Christman JK, Fleet JC, Cravo ML, Salomon RN, Smith D, Ordovas J, Selhub J,

Mason JB. Moderate folate deficiency does not cause global hypomethylation of hepatic and colonic DNA or c-myc specific hypomethylation of colonic DNA in rats. Am J Clin Nutr 1995; 61:1083-90.

70. Kim YI, Pogribny IP , Basnakian AG, Miller JW, Selhub J, James SJ, Mason JB. Folate

deficiency in rats induces DNA strand breaks and hypomethylation within p53 tumor sup-pressor gene. Am J Clin Nutr 1997; 65:46-52.

71. Jacob RA, Pinalto FS, Henning SM, Zhang JZ, Swendseid ME. In vivo methylation capac-ity is not impaired in healthy men during a short-term dietary folate and methyl group restriction. J Nutr 1995; 125:1495-502.

72. Jacob RA, Gretz DM, T aylor PC, James SJ, Pogribny IP , Miller BJ, Henning SM, Swenseid ME.

Moderate folate depletion increases plasma homocysteine and decreases lymphocyte DNA methylation in post-menopausal women. J Nutr 1998; 128:1204-12.

73. Rampersaud GC, Kauwell GP , Hutson AD, Cerda JJ, Bailey LB. Genomic DNA methyla-tion decreases in response to moderate folate depletion in elderly women. Am J Clin Nutr 2000; 72:98-1003.

74. Pufulet M, Al-Ghaniem R, Khulshal A, Appleby P , Harris N, Gout S, Emery PW, Sanders

TAB. Effect of folic acid supplementation on genomic DNA methylation in patients with colorectal adenoma. Gut 2005; 54:648-53.

75. Cravo ML, Pinto AG, Chaves P , Cruz JA, Lage P , Nobre-Leitao C, Costa Mira F . Effect

of folate supplementation on DNA methylation of rectal mucosa in patients with colonic adenomas: correlation with nutrient intake. Clin Nutr 1998; 17:45-9.

76. Kim YI, Baik HW , Fawaz K, Knox T, Lee YM, Norton R, Libby E, Mason JB. Effects of

folate supplementation on two provisional molecular markers of colon cancer: a prospective randomised trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2001; 96:184-95.

77. Cravo ML, Fidalgo P , Pereira AD, Gouveia-Oliveira A, Chaves P , Selhub J, Mason JB,

Mira FC, Leitao CN. DNA methylation as an intermediate biomarker in colorectal cancer: modulation by folic acid supplementation. Eur J Cancer Prev 1994; 3:473-9.

78. Choi SW , Friso S, Dolnikowski GG, Edmondson AN, Smith DE, Mason JB. Biochemical

and molecular aberrations in the rat colon due to folate depletion are age specific. J Nutr 2003; 133:1206-12.

79. Song J, Sohn KJ, Medline A, Ash C, Gallinger S, Kim YI. Chemopreventitive effects of

dietary folate on intestinal polyps in APC +/- hMSH2-/- mice. Cancer Res 2000; 60:3191-9. 80. Okamo M, Bell DW , Haber DA, Li E. DNA methyltransferasesDNMT3a and DNMT3b

are essential for de novo methylation and mammalian development. Cell 1999; 99:247-57. 81. Slattery ML, Potter JD, Samonwitz W , Schaffer D, Lepert M. Methylenetetrahydrofolate

reductase, diet and risk of colon cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 1999; 8:513-8. 82. Ma J, Stampfer MJ, Giovanucci E, Artigas C, Hunter DJ, Fuchs C, Willett WC, Selhub J,

Hennekens CH, Rozen R. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reducatse polymorphism, dietary interactions, and risk of colorectal cancer. Cancer Res 1997; 57:1098-109.

83. Giovannucci E. Epidemiologic studies of folate and colorectal neoplasia: A Review. J Nutr

2002; 132:2350-5.

84. Charles D, Ness AR, Campbell D, Davey-Smith G, Hall MH. Taking folate in pregnancy

and risk of maternal breast cancer. Br Med J 2004; 329:1375-6.

85. Choi SW . Vitamin B12 deficiency: a new risk factor for breast cancer? Nutr Rev 1999;

57:250-3.

遗传学名词解释

1 Chromosomal disorders:染色体结构和数目异常而导致的疾病。如Down’s综合征(+21),猫叫综合征(5p-)。 2 Single gene disorders: 由于控制某个性状的等位基因突变导致的疾病称之。 3 Polygenic disorders:一些常见病和多发病的发生由遗传因素和环境因素共同决定,遗传因素中不是一对等位基因,而是多对基因共同作用于同一个性状。 4 Mitochondrial disorders:是指线粒体DNA上的基因突变导致所编码线粒体蛋白质结构和数目异常,导致线粒体病。线粒体是位于细胞质中的细胞器,故随细胞质(母系)遗传。 4 Somatic cell disorders: 体细胞中遗传物质突变导致的疾病。 5 分离律 (Law of segregation)基因在体细胞内成对存在,在生殖细胞形成过程中,同源染色体分离,成对的基因彼此分离,分别进入不同的生殖细胞。细胞学基础:同源染色体的分离。 6 自由组合律(law of independent assortment)在生殖细胞形成过程中,不同的非等位基因,可以相互独立的分离,有均等的机会组合到—个生殖细胞的规律性活动。 7 连锁与互换定律-(law of linkage and crossing over)位于同一染色体上的两个基因,在生殖细胞形成时,如果它们相距越近,一起进入同一生殖细胞的可能性越大;如果相距较远,它们之间可以发生交换。 8 Gene mutation: DNA分子中的核苷核序列发生改变,导致遗传密码编码信息改变,造成基因表达产物蛋白质的氨基酸变化,从而引起表型的改变。 9 Point mutation:指单个碱基被另一个碱基替代。转换(transition):嘧啶之间或嘌呤之间的替代。颠换(transversion):嘧啶和嘌呤之间的替代。 10 Same sense mutation:碱基替换后,所编码的氨基酸没有改变。多发生于密码子的第三个碱基。 11 Missense mutation:碱基替换后,改变了氨基酸序列。错义突变多发生于密码子的第一、二个碱基 12 Nonsense mutation:碱基替换后,编码氨基酸的密码子变为终止密码子(UAA、UGA、UAG),多肽链合成提前终止。 13 Frame shift mutation:在DNA编码序列中插入或丢失一个或几个碱基,造成插入或缺失点下游的DNA编码框架全部改变,其结果是突变点以后的氨基酸序列发生改变 14 dynamic mutation :人类基因组中的一些重复序列在传递过程中重复次数发生改变导致遗传病的发生,称动态突变。

JAVA常见名词解释

JAVA常见名词解释 面向对象: 面向对象程序设计(Object-Oriented Programming)是一种起源于六十年代,发展已经将近三十年的程序设计思想。其自身理论已十分完善,并被多种面向对象程序设计语言(Object-Oriented Programming Language,以下简称OOPL)实现。对象是对现实世界实体的模拟,由现实实体的过程或信息牲来定义。一个对象可被认为是一个把数据(属性)和程序(方法)封装在一起的实体,这个程序产生该对象的动作或对它接受到的外界信号的反应。这些对象操作有时称为方法。区别面向对象的开发和传统过程的开发的要素有:对象识别和抽象、封装、多态性和继承。(参见百度百科:面向对象) 面向对象要素:封装、多态、继承 Java名词解释: Abstract class 抽象类:抽象类是不允许实例化的类,因此一般它需要被进行扩展继承。 Abstract method 抽象方法:抽象方法即不包含任何功能代码的方法。 Access modifier 访问控制修饰符:访问控制修饰符用来修饰Java中类、以及类的方法和变量的访问控制属性。 Anonymous class 匿名类:当你需要创建和使用一个类,而又不需要给出它的名字或者再次使用的使用,就可以利用匿名类。 Anonymous inner classes 匿名内部类:匿名内部类是没有类名的局部内部类。 API 应用程序接口:提供特定功能的一组相关的类和方法的集合。

Array 数组:存储一个或者多个相同数据类型的数据结构,使用下标来访问。在Java中作为对象处理。 Automatic variables 自动变量:也称为方法局部变量method local variables,即声明在方法体中的变量。 AWT抽象窗口工具集:一个独立的API平台提供用户界面功能。 Base class 基类:即被扩展继承的类。 Blocked state 阻塞状态:当一个线程等待资源的时候即处于阻塞状态。阻塞状态不使用处理器资源 Call stack 调用堆栈:调用堆栈是一个方法列表,按调用顺序保存所有在运行期被调用的方法。 Casting 类型转换:即一个类型到另一个类型的转换,可以是基本数据类型的转换,也可以是对象类型的转换。 char 字符:容纳单字符的一种基本数据类型。 Child class 子类:见继承类Derived class Class 类:面向对象中的最基本、最重要的定义类型。 Class members 类成员:定义在类一级的变量,包括实例变量和静态变量。 Class methods 类方法:类方法通常是指的静态方法,即不需要实例化类就可以直接访问使用的方法。 Class variable 类变量:见静态变量Static variable Collection 容器类:容器类可以看作是一种可以储存其他对象的对象,常见的容器类有Hashtables和Vectors。 Collection interface 容器类接口:容器类接口定义了一个对所有容器类的公共接口。

泛读教程答案

U n i t1R e a d i n g R t r a t e g i e s Section A Word Pretest 1----5 B C B B B 6----10 A A C C B Reading Skill 2----5 CBCA 6----9 BBAA Vocabulary Building 1 d. practicable/practical e. practiced 2. a.worthless b. worthy c. worthwhile d.worth e.worth 3. a.vary b.variety c.variation d.various/varied e.Various 4. a.absorbing b.absorbed c.absorb d.absorption e.absorbent 2 1.a.effective b.efficient c.effective 2.a.technology b.technique 3.a.middle b.medium c.medium Cloze Going/about/trying expectations/predictions questions answers Predictions/expectations tell know/foretell end Develop/present worth Section B 1----4 TFTT 5----8 CBCC 9----11 TFF 12----17 CAACCA Section C 1----4 FFTF 5----8 FTTT Unit 2 Education Section A Word Pretest 1----5 ABACC 6----11 ABABCC Reading Skill 4----6 CBB 1----6 FTFFTT Vocabulary Building 1 1. mess 2. preference 3. aimlessly 4. remarkable/marked 5.decisive 6.shipment 7. fiery 8.physically 9.action 10.housing 2 1. a.aptitude b.attitude 2. a.account b.counted c. counted 3. a.talent b.intelligence

遗传学名词解释大全

autoregulation 自我调节:基因通过自身的产物来调节转录。 autosome 常染色体:性染色体以外的任何染色体。 auxotroph 营养缺陷型:微生物的一种突变体,它不能合成生长所需的物质,培养时必须在培养基中加入此物质才能生长。 back mutation 回复突变:见reversion bacteriophage (phage) 一种感染细菌的病毒。 balance model 平衡模型:关于遗传变异比例的一种模型,它认为自然选择维持了群体中大量遗传变异的存在。 balanced polymorphism 平衡多态现象:稳定的遗传多态现象是由自然选择来维持的。 Barr body 巴氏小体:在正常雌性哺乳动物的核中有一个高度凝聚的染色质团,它是一个失活的X染色体。 base analog 碱基类似物:一种化学物质,其分子结构和DNA的碱基相似,在DNA的代谢过程中有时会取代正常碱基,结果使DNA的碱基发生突变。 bead theory 串珠学说:已被否定的学说,认为基因附着在染色体上,就象项链上的串珠。它既是突变单位又是重组单位。 binary fission 二分分裂:一个细胞分裂为大小相近的两个子细胞的过程。binomial distribution 二项分布:具有两种可能结果的 biparental zygote 双亲合子:又称双亲遗传(biparental inheriance),衣藻(chlamydomonas) 的合子含有来自双亲的DNA。这种细胞一般很少见。 biochemical mutation 生化突变,见自发突变(autotrophic mutation)。bivalent 二价体:在第一次减数分裂时彼此联合的一对同源染色体。bottleneck effect 瓶颈效应:一种类型的漂变。当群体很小时产生这种效应,结果使基因座中有的基因丢失了。 branch-point sequence 分支点顺序:在哺乳动物细胞中的保守顺序:YNCURAY(Y: 嘧啶,R:嘌呤, N:任何碱基),位于核mRNA内含子和II 类内含子3'端附近,其中的A可通过5'-2'连接的方式和内含子5'端相连接,在剪接时形成套马索状结构。 broad-sense heritability 广义遗传力:表型方差中所含遗传方差的百分比。cotplot 浓度时间乘积图:一个样本单位单链DNA分子复性动力学曲线。以结合为双链的量为纵坐标,以DNA浓度和时间的乘积为横坐标作出的DNA复性动力学曲线 C value C值:生物单倍体基因所含的DNA总量。 CAAT element CAAT元件:真核启动子上游元件之一,常位于上游-80bp附近,其功能是控制转录起始频率,保守顺序是 5'-GGCCAATCT-3'。 cancer 癌:恶性肿瘤,细胞失控,异常分裂且在生物体内可播散。 5'-capping -5'加帽:在 mRNA加工的过程中在前体 mRNA分子的5'端加上甲基核苷酸的“帽子”。 catabolite repression (glucose effect) 分解代谢物阻遏(糖效应):当糖存在时能诱发细菌操纵子的失活,即使操纵子的诱导物存在也是如此。 cDNA 互补DNA:以mRNA为模板,以反转录酶催化合成的DNA的拷贝。 cDNA clone cDNA分子克隆:将cDNA片段装在载体上转化细菌扩增出多克隆的过程,最终可建立cDNA文库。

普通遗传学(第2版)杨业华课后习题及答案

1 复习题 1. 什么是遗传学?为什么说遗传学诞生于1900年? 2. 什么是基因型和表达,它们有何区别和联系? 3. 在达尔文以前有哪些思想与达尔文理论有联系? 4. 在遗传学的4个主要分支学科中,其研究手段各有什么特点? 5. 什么是遗传工程,它在动、植物育种及医学方面的应用各有什么特点? 2 复习题 1. 某合子,有两对同源染色体A和a及B和b,你预期在它们生长时期体细胞的染色体组成应该是下列哪一种:AaBb,AABb,AABB,aabb;还是其他组合吗? 2. 某物种细胞染色体数为2n=24,分别指出下列各细胞分裂时期中的有关数据: (1)有丝分裂后期染色体的着丝点数 (2)减数分裂后期I染色体着丝点数 (3)减数分裂中期I染色体着丝点数 (4)减数分裂末期II的染色体数 3. 假定某杂合体细胞内含有3对染色体,其中A、B、C来自母体,A′、B′、C′来自父本。经减数分裂该杂种能形成几种配子,其染色体组成如何?其中同时含有全部母亲本或全部父本染色体的配子分别是多少? 4. 下列事件是发生在有丝分裂,还是减数分裂?或是两者都发生,还是都不发生? (1)子细胞染色体数与母细胞相同 (2)染色体复制 (3)染色体联会 (4)染色体发生向两极运动 (5)子细胞中含有一对同源染色体中的一个 (6)子细胞中含有一对同源染色体的两个成员 (7)着丝点分裂 5. 人的染色体数为2n=46,写出下列各时期的染色体数目和染色单体数。 (1)初级精母细胞(2)精细胞(3)次级卵母细胞(4)第一级体(5)后期I (6)末期II (7)前期II (8)有丝分裂前期(9)前期I (10)有丝分裂后期 6. 玉米体细胞中有10对染色体,写出下列各组织的细胞中染色体数目。 (1)叶(2)根(3)胚(4)胚乳(5)大孢子母细胞

遗传学名词解释

遗传学名词解释 11、性状:生物体或其组成部分所表现的形态、生理或行为特征称为性状(character/trait) 13、相对性状:不同生物个体在单位性状上存在不同的表现,这种同一单位性状的相对差异 称为相对性状 14、显性(dominate)性状:在子一代中出现来的某一亲本的性状。 15、隐性 (recessive)性状:在子一代中未出现来的某一亲本的性状。 17、基因型(genotype):指生物个体基因组合,表示生物个体的遗传组成,又称遗传型; 18、表现型(phenotype):指生物个体的性状表现,简称表型。 19、纯合基因型:具有一对相同基因的基因型称为纯合基因型(homozygous genotype),如 CC和cc;这类生物个体称为纯合体(homozygote)。 ●显性纯合体(dominant homozygote), 如:CC. ●隐性纯合体(recessive homozygote), 如:cc. 21、基因的分离定律:一对等位基因在杂合体中各自保持其独立性,在配子形成时,彼此分 开,随机地进入不同的配子,在一般情况下:F1杂合体的配子分离比 为1:1,F2表型分离比是3:1,F2基因型分离比为1:2:1 22、测交(test cross)法:即把被测验的个体与隐性纯合亲本杂交,根据侧交子代(Ft)的 表现型和比例测知该个体的基因型。 23、独立分配定律:支配两对(或两对以上)不同性状的等位基因,在杂合状态时保持其独 立性。配子形成时,各等位基因彼此独立分离,不同对的基因自由组合。 24、系谱分析法:用图解表明一个家族中某种性状(或遗传疾病)发生的情况,进而判断该 性状(或遗传疾病)的遗传方式。 27、外显率(penetrance):指在特定环境中,某一基因型(常指杂合子)个体显示出预期表型 的频率(以百分比表示)。就是说同样的基因型在一定的环境中有的 个体表达了,而有的个体可能没有表达,这样外显率就小于100% ——不完全外显。外显率为100%——完全外显 28、表现度(expressivity):是指具有相同基因型的个体之间基因表达的变化程度。 29、共显性/并显性:一对等位基因的两个成员在杂合体中都表达的遗传现象。 30、镶嵌显性:由于等位基因的相互作用,双亲的性状在子代同一个体的不同部位表现的镶 嵌图式。 31、隐性致死基因:在杂合时不影响个体的生活力,但在纯合时有致死效应的基因。 32、显性致死基因(dominant lethal gene):在杂合状态下即表现致死作用的致死基因 33、复等位基因:在群体中占据某同源染色体同一座位的两个以上的决定同一性状的基因 34、基因互作:基因在决定同一生物性状表现时,所表现出来的相互作用。 35、互补基因:两对非等位的显性基因同时存在并影响生物的某同一性状时才使之表现该性 状,其中任一基因发生突变都会导致同一突变性状出现,这类基因称为互补基因。 37、叠加效应:不同基因对性状产生相同影响,只要两对等位基因中存在一个显性基因,表 现为一种性状;双隐性个体表现另一种性状;F2产生15:1的性状分离比例。 这类作用相同的非等位基因叫做叠加基因 38、上位效应:影响同一性状的两对非等位基因中的一对基因(显性或隐性)掩盖另一对显 性基因的作用时,所表现的遗传效应称为上位效应,其中的掩盖者称为上位 基因,被掩盖者称为下位基因。 39、显性上位:在上位效应中,起掩盖作用的是一个显性基因,使另一个显性基因的表型被 抑制,孟德尔F2表型比率被修饰为12:3:1

遗传学课后习题答案

遗传学复习资料 第一章绪论 1、遗传学:是研究生物遗传和变异的科学 遗传:亲代与子代相似的现象就是遗传。如“种瓜得瓜、种豆得豆” 变异:亲代与子代、子代与子代之间,总是存在着不同程度的差异,这种现象就叫做变异。 2、遗传学研究就是以微生物、植物、动物以及人类为对象,研究他们的遗 传和变异。遗传是相对的、保守的,而变异是绝对的、发展的。没有遗传,不可能保持性状和物种的相对稳定性;没有变异,不会产生新的性状,也就不可能有物种的进化和新品种的选育。遗传、变异和选择是生物进化和新品种选育的三大因素。 3、1953年瓦特森和克里克通过X射线衍射分析的研究,提出DNA分子结构 模式理念,这是遗传学发展史上一个重大的转折点。 第二章遗传的细胞学基础 原核细胞:各种细菌、蓝藻等低等生物有原核细胞构成,统称为原核生物。 真核细胞:比原核细胞大,其结构和功能也比原核细胞复杂。真核细胞含有核物质和核结构,细胞核是遗传物质集聚的主要场所,对控制细胞发育和性状遗传起主导作用。另外真核细胞还含有线粒体、叶绿体、内质网等各种膜包被的细胞器。真核细胞都由细胞膜与外界隔离,细胞内有起支持作用的细胞骨架。 染色质:在细胞尚未进行分裂的核中,可以见到许多由于碱性染料而染色较深的、纤细的网状物,这就是染色质。 染色体:含有许多基因的自主复制核酸分子。细菌的全部基因包容在一个双股环形DNA构成的染色体内。真核生物染色体是与组蛋白结合在一起的线状DNA 双价体;整个基因组分散为一定数目的染色体,每个染色体都有特定的形态结构,染色体的数目是物种的一个特征。 染色单体:由染色体复制后并彼此靠在一起,由一个着丝点连接在一起的姐妹染色体。 着丝点:在细胞分裂时染色体被纺锤丝所附着的位置。一般每个染色体只有一个着丝点,少数物种中染色体有多个着丝点,着丝点在染色体的位置决定了染色体的形态。 细胞周期:包括细胞有丝分裂过程和两次分裂之间的间期。其中有丝分裂过程分为: (1)DNA合成前期(G1期);(2)DNA合成期(S期); (3)DNA合成后期(G2期);(4)有丝分裂期(M期)。 同源染色体:生物体中,形态和结构相同的一对染色体。 异源染色体:生物体中,形态和结构不相同的各对染色体互称为异源染色体。 无丝分裂:也称直接分裂,只是细胞核拉长,缢裂成两部分,接着细胞质也分裂,从而成为两个细胞,整个分裂过程看不到纺锤丝的出现。在细胞分裂的整个过程中,不象有丝分裂那样经过染色体有规律和准确的分裂。 有丝分裂:包含两个紧密相连的过程:核分裂和质分裂。即细胞分裂为二,各含有一个核。分裂过程包括四个时期:前期、中期、后期、末期。在分裂过程中经过染色体有规律的和准确的分裂,而且在分裂中有纺锤丝的出现,故称有丝分裂。

java专业术语

1.API:Java ApplicationProgrammingInterface APT(应用程序接口) 2.AWT:Abstract WindowToolkit AWT(抽象窗口工具集) 3.JFC:JavaTM Foundation Classes(JFC)(Java基础类) 4.JNI:JavaTMNative Interface JNI(Java本地接口) 5.JSP:JavaServerTM Pages(Java编程语言代码) 6.J2EETM:JavaTM 2PlatformEnterpriseEdition J2EE(Java2企业版-平台提供一个基于组件设计、开发、集合、展开企业应用的途径) 7.J2METM:JavaTM 2MicroEdition J2ME(Java2精简版-API规格基于J2SETM,但是被修改成为只能适合某种产品的单一要求) 8.JVM:JavaTM VirtualMachinel JVM(Java虚拟机) 9.JDKTM:JavaDeveloper'sKit JDK(Java开发工具集) A: 10.AJAX:Asynchronous JavaScript and XML(异步) 11.annotation:注解 12.Ant 13.AOP:aspect-oriented programming(面向方向编程) 14.application:应用 15.argument:参数 B: 16.B2B:Business-to-Business(业务对业务) 17.BAM:Business Activity Monitoring(业务活动监测) 18.BMP:bean-managed persistence, Bean(管理的持久化) 19.BPEL:Business Process Excursion Language(业务流程执行语言) 20.BPM:Business Process Modeling(业务流程建模) 21.build:建立、编译 C: 22.C2B:Consumer-to-Business(客户对业务) 23.CAD:Computer Aided Design(计算机辅助设计) 24.CAM:Computer Aided Modeling(计算机辅助建模) 25.case-insensitive:大小写不敏感 26.case-sensitive:大小写敏感 27.container:容器 28.cluster:集群 29.CMP:container-managed persistence(容器管理的持久化) https://www.360docs.net/doc/8b12500540.html,ponent:组件,部件 31.configuration:配置 32.context:上下文,环境 33.control:控件 34.convention:约定 35.CORBA:Common Object Request Broker Architecture(公共对象请求代理体系) 36.COS:Common Object Services(公共对象服务)

遗传学名词解释

名词解释: 1、遗传与变异:生物通过繁殖的方式来繁衍种族,保持生命在世代间的连续,保持子代与亲代的相似与类同,这种现象叫遗传,遗传的本质就是遗传物质通过不断地复制和传递,保持亲代与子代间的相似与类同,与此同时,亲代与子代之间,子代个体之间总存在着不同程度的差异,包括环境差异与遗传物质差异,这种差异就是变异。 2、遗传变异:变异不一定都能遗传,只有由遗传物质改变导致的变异可以传递给后代,这种变异叫遗传变异。 3、遗传学: 经典定义:研究生物的遗传和变异现象及其规律的一门学科。 现代定义: (1)在生物的群体、个体、细胞和基因等层次上研究生命信息(基因)的结构、组成、功能、变异、传递(复制)和表达规律与调控机制的一门科学--基因学。 (2)研究基因和基因组的结构与功能的学科。 名词解释: 1、性状:在遗传学上,把生物表现出来的形态特征和生理特征统称为性状。 2、相对性状:同一性状的两种不同表现形式叫相对性状。 3、显性性状:孟德尔把F1表现出来的性状叫显性性状,F1不表现出来的性状叫隐性性状。 4、性状分离现象:孟德尔把F2中显现性状与隐性性状同时表现出来的现象叫做性状分离现象。 5、等位基因与非等位基因:等位基因是指位于同源染色体上,占有同一位点,但以不同的方式影响同一性状发育的两个基因。非等位基因指位于不同位点上,控制非相对性状的基因。 6、自交:F1代个体之间的相互交配叫自交。 7、回交:F1代与亲本之一的交配叫回交。 8、侧交:F1代与双隐性个体之间的交配叫侧交。 9、基因型和表型 基因型是生物体的遗传组成,是性状得以表现的内在物质基础,是肉眼看不到的,要通过杂交试验才能检定。如cc,CC,Cc。 表型是生物体所表现出来的性状,是基因型和内外环境相互作用的结果,是肉眼可以看到的。如花的颜色性状。 10、纯合体、杂合体 由两个同是显性或同是隐性的基因结合的个体,叫纯合体,如CC,cc。由一个显性基因与一个隐性基因结合而成的个体,叫杂合体,如Cc。 11、真实遗传 指纯合体的物种所产生的子代表型与亲本表型相同的现象。纯合体所产生的后代性状不发生分离,能真实遗传,杂合体自交产生的后代性状要发生分离,它不能真实遗传。 名词解释: 1、染色体与染色质:是指核内易于被碱性染料着色的无定形物质,是由DNA、组蛋白、非组蛋白及少量RNA组成的复合体,以纤丝状存在于核膜内面。当细胞分裂时,核内的染色质便螺旋化形成一定数目和形状的染色体。两者是同一物质在细胞分裂过程中表现的不同形态。核内遗传物质就集中在这染色体上。 2、常染色质与异染色质:着色较浅,呈松散状,分布在靠近核的中心部分,是遗传的活性部位。着色较深,呈致密状,分布在靠近核内膜处,是遗传的惰性部位。又分结构异染色质或组成型异染色质和兼性异染色质。前者存在于染色体的着丝点区及核仁组织区,后者在间期时仍处于浓缩状态, 3、核小体:是染色质的基本结构单位,直径10nm,其核心是由四种组蛋白(H2A、H2B、H3、H4各2分子共8分子)构成的扁球体。 4、同源染色体:指形态、结构和功能相似的一对染色体,他们一条来自父本,一条来自母本。 5、联会:分别来自父母本的同源染色体逐渐成对靠拢配对,这种同源染色体的配对称为联会。

刘祖洞遗传学习题答案

第六章 染色体和连锁群 1、在番茄中,圆形(O )对长形(o )是显性,单一花序(S )对复状花序(s )是显性。这两对基因是连锁的,现有一杂交 得到下面4种植株: 圆形、单一花序(OS )23 长形、单一花序(oS )83 圆形、复状花序(Os )85 长形、复状花序(os )19 问O —s 间的交换值是多少 解:在这一杂交中,圆形、单一花序(OS )和长形、复状花序(os )为重组型,故O —s 间的交换值为:%20%10019 85832319 23=?++++= r 2、根据上一题求得的O —S 间的交换值,你预期 杂交结果,下一代4种表型的比例如何 解: O_S_ :O_ss :ooS_ :ooss = 51% :24% :24% :1%, 即4种表型的比例为: 圆形、单一花序(51%), 圆形、复状花序(24%), 长形、单一花序(24%), 长形、复状花序(1%)。 3、在家鸡中,白色由于隐性基因c 与o 的两者或任何一个处于纯合态有色要有两个显性基因C 与O 的同时存在,今有下列的交配: ♀CCoo 白色 × ♂ccOO 白色 ↓ 子一代有色 子一代用双隐性个体ccoo 测交。做了很多这样的交配,得到的后代中,有色68只,白

色204只。问o —c 之间有连锁吗如有连锁,交换值是多少 解:根据题意,上述交配: ♀ CCoo 白色 ccOO 白色 ♂ ↓ 有色CcOo ccoo 白色 ↓ 有色C_O_ 白色(O_cc ,ooC_,ccoo ) 416820468=+ 4 3 68204204=+ 此为自由组合时双杂合个体之测交分离比。 可见,c —o 间无连锁。 (若有连锁,交换值应为50%,即被测交之F1形成Co :cO :CO :co =1 :1 :1 :1的配子;如果这样,那么c 与o 在连锁图上相距很远,一般依该二基因是不能直接测出重组图距来的)。 4、双杂合体产生的配子比例可以用测交来估算。现有一交配如下: 问:(1)独立分配时,P= (2)完全连锁时,P= (3)有一定程度连锁时,p= 解:题目有误,改为:)2 1( )21 (aabb aaBb Aabb AaBb p p p p -- (1)独立分配时,P = 1/4; (2)完全连锁时,P = 0; (3)有一定程度连锁时,p = r /2,其中r 为重组值。 5、在家鸡中,px 和al 是引起阵发性痉挛和白化的伴性隐性基因。今有一双因子杂种公鸡 al Px Al px 与正常母鸡交配,孵出74只小鸡,其中16只是白化。假定小鸡没有一只早期死亡,而px 与al 之间的交换值是10%,那么在小鸡4周龄时,显出阵发性痉挛时,(1)在白化小鸡中有多少数目显出这种症状,(2)在非白化小鸡中有多少数目显出这种症状 解:上述交配子代小鸡预期频率图示如下: ♀W Al Px al Px Al px ♂

普通遗传学名词解释(英文)

遗传(heredity):指亲代与子代之间相似的现象。 变异(variation):指亲代与子代之间、子代个体之间存在的差异。 染色体(chromosome):指细胞分裂过程中,由染色质聚缩而呈现为一定数目和形态的复合结构。 有丝分裂(mitosis):又称间接分裂,是高等植物细胞分裂的主要方式,包含细胞核分裂和细胞质分裂两个紧密相连的过程。 减数分裂(meiosis):又称成熟分裂,是性母细胞成熟时,配子形成过程中发生的一种特殊的有丝分裂方式。由于形成子细胞内染色体数目比性母细胞减少一半,因此称为减数分裂。 联会(synapsis):减数分裂偶线期开始出现同源染色体配对现象,即联会。 姊妹染色单体(sister chromatid):二价体中一条染色体的两条染色单体,互称为姊妹染色单体。 同源染色体(homologous chromosome):指形态、结构和功能相似的一对染色体,他们一条来自父本,一条来自母本。 性状(character):生物体所表现的形态特征和生理特性的总称。 单位性状(unit character):把生物体所表现的性状总体区分为各个单位,这些分开来的性状称为单位性状。 相对性状(contrasting character) 等位基因(allele):位于同源染色体上,位点相同,控制着同一性状的基因。 测交(test cross):是指被测验的个体与隐性纯合体间的杂交。 基因型(genotype):也称遗传型,生物体全部遗传物质的组成,是性状发育的内因。表现型(phenotype):生物体在基因型的控制下,加上环境条件的影响所表现性状的总和。 染色单体(Chromatid)又称染色分体,是染色体的一部分。在减数分裂或有丝分裂过程中,复制了的染色体中的两条子染色体。 非姐妹染色单体(non-sister chromatid):两个同源染色体中由不同着丝点相连的染色单体,就叫非姐妹染色单体。 着丝粒(centromere):在细胞分裂时染色体被纺锤丝所附着的位置。一般每个染色体只有一个着丝点粒,少数物种中染色体有多个着丝粒,着丝粒在染色体的位置决定了染色体的形态。 基因(gene):指携带有遗传信息的DNA序列,是控制性状的基本遗传单位,亦即一段具有功能性的DNA序列。基因通过指导蛋白质的合成来表达自己所携带的遗传信息,从而控制生物个体的性状表现。 相对性状(contrasting character):是指同种生物的各个体间同一性状的不同表现类型。 突变型基因(Mutant gene)为DNA分子中发生碱基对的增添、缺失或改变,而引起的基因结构的改变 端粒(Telomeres)是线状染色体末端的DNA重复序列。端粒是线状染色体末端的一种特殊结构,在正常人体细胞中,可随着细胞分裂而逐渐缩短。 动粒(Kinetochore)是真核细胞染色体中位于着丝粒两侧的3层盘状特化结构,其化学本质为蛋白质,是非染色体性质物质附加物,与染色体的移动有关。 野生型基因(wild type gene):在自然群体中往往有一种占多数座位的等位基因,称为野生型基因。 自交(selfing):指来自同一个体的雌雄配子的结合或具有相同基因型个体间的交 配或来自同一无性繁殖系的个体间的交配。 纯合子(Homozygote) :是指同一位点 (locus) 上的两个等位基因相同的基因型个体 , 如AA,aa。相同的纯合子间交配所生后代不出现性状的分离。分为隐性纯合子和显性纯合子。 杂合子(heterozygote) :是指同一位点上的两个等位基因不相同的基因型个 体 , 如Aa。杂合子间交配所生后代会出现性状的分离。 分离定律(law of segregation):为孟德尔遗传定律之一。决定相对性状的一对等位基因同时存在于杂种一代(F1)的个体中,但仍维持它们各自的个体性,在配子形成时互相分开,分别进入一个配子细胞中去。 相引相(coupling phase)两个显性性状连接在一起遗传,而两个隐性性状连接在一起遗传的杂交组合。 相斥相(repulsion phase)两个性状分别为甲和乙,甲显性性状与乙隐性性状连接在一起遗传,而乙显性性状和甲隐性性状连接在一起遗传的杂交组合。 选择(select):改变基因频率的最重要因素,也是生物进化的驱动力量。包括自然选择和人工选择。 宋体的是在汉语的遗传学书上的;黑体的是老师说的;华文新魏的是百度的。 遗传距离(genetic distance):两个基因在同一染色体上的相对距离,通常以交换值来表示。 两点测验(two-point testcross):是基因定位最基本的方法。首先通过一次杂交和一次用隐性亲本来测交来确定两对基因是否连锁,然后再根据其交换值来确定它们在同一染色体上的位置。 三点测验(three-point testcross):是基因定位最常用的方法,它是通过1次杂交和1次用隐性亲本测交,同时确定3对基因在染色体上的位置。 常染色体(autosome):生物多对染色体中,除性染色体外的其余各对染色体统称为常染色体。 性染色体(sex chromosome):在生物多对染色体中,直接与性别决定有关的一条或一对染色体。 常染色质(euchromatin):常染色质是指间期核内染色质纤维折叠压缩程度低,处于伸展状态,用碱性染料染色时着色浅的那些染色质。 异染色质(heterochromatin):在细胞周期中,间期、早期或中、晚期,某些染色体或染色体的某些部分的固缩常较其他的染色质早些或晚些,其染色较深或较浅,具有这种固缩特性的染色体称为异染色质。 限性遗传(sex-limited inheritance):指位于Y染色体(XY型)或W染色体(ZW 型)上的基因所控制的遗传性状只局限于雄性或雌性上表现的现象。 性别影响遗传(sex-influenced inheritance,又称从性遗传sex-controlled inheritance):与限性遗传不同,它是位于常染色体上的基因所控制的性状,是由于内分泌及其他关系使某些性状或只出现于雌雄一方;或在一方为显性,另一方为隐性的现象。 连锁强度 数量性状(quantitative trait):表现连续变异的遗传性状。(指在一个群体内的各个体间表现为连续变异的性状) 质量性状(qualitative trait/discrete characters):表现不连续变异的遗传性状。(指属性性状,即能观察而不能量测的性状,是指同一种性状的不同表现型之间不存在连续性的数量变化,而呈现质的中断性变化的那些性状。) 基因座(locus):一个特定的基因在染色体上的特定位置。 遗传率(又叫遗传力,heritability):指遗传方差在总方差(表型方差)中所占的比值,可以作为杂种后代进行选择的一个指标。 广义遗传率h2B(heritability in the broad sense):指遗传方差占总方差(表型方差)的比值。 狭义遗传率h2N(heritability in the narrow sense):指基因加性方差占总方差的比值。现实(选择)遗传率(Reality(select) heritability):通过选择结果也可以估算群体的遗传率,这个遗传率叫做现实遗传率,用hR表示。 选择反响(Select response)the degree of respond to mating the selected parent 选择差(selection difference):选择强度即标准化的选择差)指的是要留种的个体表型均值与畜群表型平均数之差。 杂种优势(heterosis):指两个遗传组成不同的亲本杂交产生的杂种一代,在生长势、生活力、繁殖力、产量和品质上比其双亲优越的现象。 超亲遗传(transgressive inheritance):指在数量性状的遗传中,杂种第二代及以后的分离世代群体中,出现超越双亲性状的新表型的现象。 复等位基因(multiple allele):同一位点的基因可能有两种以上的形式,遗传学把同源染色体相同位点上存在的3个或3个以上的等位基因称为复等位基因。 连锁群(linkage group):存在于同一染色体上的基因群。(位于同一条染色体上的所有基因座) 互补群(Complementation group):能与其它的互补群发生互补反应、同一个野生型基因产生的一系列(所有的)突变基因。除野生型外其它位点统称为一个互补群。整倍体(euploid):染色体数是x整倍数的个体或细胞称为整倍体。 非常整体(?) 非整倍体(aneuploid):在正常合子染色体数(2n)的基础上增加或减少1条或若干条染色体的个体或细胞。 单倍体(haploid):指具有配子染色体数(n)的个体或细胞。 多倍体(polyploid):三倍和三倍以上的整倍体统称为多倍体。 同源多倍体(autopolyploid):染色体组相同的多倍体叫做同源多倍体。所有染色体组来自同一物种,一般是由二倍体经染色体数目加倍形成的。 异源多倍体(allopolyploid):染色体组不同的多倍体叫做异源多倍体,其染色体组来自不同物种,一般是由不同种、属间的杂交种经染色体数目加倍形成的。 双二倍体(amphidiploid):异源四倍体中,由于两个种的染色体各具有两套,因而又叫做双二倍体。 单体(monosomic);在亚倍体中,染色体数比正常2n少一条的个体或细胞叫做单体,其染色体组成为2n-1=(n-1)II+I。 单倍体(haploid);单倍体是指具有配子染色体数(n)的个体或细胞。 单价体(univalent);本应联会而未联会的染色体。 二价体(bivalent);一对配对的同源染色体称二价体 三价体(trivalent);在减数分裂中,发生联会的三个染色体配成一组的多价体,称为三价体或三价染色体 缺体(nullisomic);对染色体的两条全部丢失了的个体或细胞成为缺体,其染色体组成为2n-2=(n-1)II。 四体(tetrasomic);在正常2n基础上,某一对染色体多了两个成员的个体或细胞称为四体,其染色体组成为2n+2=(n-1)II+IV。 双单体(double monosomic);两对染色体各缺少一条的个体或细胞称为双单体。 三体(trisomic);在正常2n的基础上,增加一条染色体的个体或细胞称为三体,其染色体组成为2n+1=(n-1)II+III。 双三体(double trisomic):在正常2n基础上,有两对染色体各自都增加一条的个体或细胞称为双三体。 超倍体(hyperploid);染色体数多于2n的非整倍体称为超倍体。 亚倍体(hypoploid);染色体数少于2n的非整倍体称为亚倍体。 缺失(deficiency);缺失是指染色体的某一片段丢失了。 重复(duplication);重复是指染色体多了自身的某一区段。 易位(translocation);异位是指染色体上某一区段移接到其非同源染色体上。 倒位(inversion);倒位指染色体中发生了某一区段倒转。 缺失圈(deficiency loop);中间缺失杂合体在偶线期和粗线期可能观察到二价体上形成环状或瘤状突起——缺失圈或缺失环 重复圈(duplication loop);重复杂合体在减数分裂联会时,如果重复区段较长,重复区段会被排挤出来,成为二价体的一个突出的环或瘤——重复圈或重复环。 感受态(competence);细胞处于能够吸收外源DNA的状态称感受态,处于感受态的细胞称作感受态细胞。 原养型(prototroph);能在矿物培养基上合成自身必需的有机化合物的细菌。 辅养型(auxotroph);一个细菌失去了合成一种至数种有机化合物的能力从而导致其不能再矿物培养基上生长。 接合(conjugation);接合是指遗传物质从供体——“雄性”转移到受体——“雌性”的过程。 转化(transformation);转化是指某些细菌(或其他生物)通过其细胞膜摄取周围供体的DNA片段,并将此外源DNA片段通过重组整合到自己染色体组的过程。 性导(sexduction);性导是指接合时由F’因子所携带的外源DNA转移到细菌染色体的过程。 转导(transduction);转导是指以噬菌体为媒介所进行的细菌遗传物质重组的过程。 质粒(plasmid);质粒是指存在于细胞中能独立进行自主复制的染色体外遗传因子。F细胞(F cells);F因子为致育因子,含有F因子的细胞即为F细胞。 F+细胞(F+cell);含有自主状态的F因子的细胞。 高频率重组(hfr)细胞(high frequency recombination);带有一个整合的F因子的细胞叫做高频重组细胞,即hfr细胞。 群体遗传学(population genetics);群体遗传学是研究群体的遗传结构及其变化规律的遗传学分支学科。应用数学和统计学方法研究群体中基因频率和基因型频率以及影响这些频率的选择效应和突变作用。 基因型频率(genotype frequency);指某一特定基因型的个体占群体的百分率。基因频率(gene frequency)。某一特定基因占该基因座基因总数的百分率。 隐性性状(recessive character):孟德尔把在子一代未表现出来的性状称为隐性性状。 显性作用() 不完全显性(incomplete dominance):杂种F1的性状表现是双亲性状的中间型。 共显性(codominance)一对等位基因的两个成员在杂合体中都表达的遗传现象。 加性(additive allelic effect) 在多基因决定的数量性状中,各基因独自产生的效应。 干扰(interference,I)一个单交换发生后,在它邻近再发生第二次单交换的机会就会减少的现象。 正干扰(positive interference):一个单交换发生后,对它临近位置再发生第二个单交换有抑制或减弱的作用为正干扰。 负干扰(negative interference) 一个单交换发生后,对它临近位置再发生第二个单交换有促进或增强的作用为正干扰。 连锁遗传(linkage inheritance)在同一同源染色体上的非等位基因连在一起而遗传的现象。 连锁(linkage)指位于同一对染色体上的非等位基因总是联系在一起遗传的现象。