The plant immune system植物免疫系统

REVIEWS

The plant immune system

Jonathan D.G.Jones 1&Jeffery L.Dangl 2

Many plant-associated microbes are pathogens that impair plant growth and reproduction.Plants respond to infection using a two-branched innate immune system.The first branch recognizes and responds to molecules common to many classes of microbes,including non-pathogens.The second responds to pathogen virulence factors,either directly or through their effects on host targets.These plant immune systems,and the pathogen molecules to which they respond,provide extraordinary insights into molecular recognition,cell biology and evolution across biological kingdoms.A detailed understanding of plant immune function will underpin crop improvement for food,fibre and biofuels production.Introduction

Plant pathogens use diverse life strategies.Pathogenic bacteria pro-liferate in intercellular spaces (the apoplast)after entering through gas or water pores (stomata and hydathodes,respectively),or gain access via wounds.Nematodes and aphids feed by inserting a stylet directly into a plant cell.Fungi can directly enter plant epidermal cells,or extend hyphae on top of,between,or through plant cells.Pathogenic and symbiotic fungi and oomycetes can invaginate feed-ing structures (haustoria),into the host cell plasma membrane.Haustorial plasma membranes,the extracellular matrix,and host plasma membranes form an intimate interface at which the outcome of the interaction is determined.These diverse pathogen classes all deliver effector molecules (virulence factors)into the plant cell to enhance microbial fitness.

Plants,unlike mammals,lack mobile defender cells and a somatic adaptive immune system.Instead,they rely on the innate immunity of each cell and on systemic signals emanating from infection sites 1–3.We previously reviewed disease resistance (R)protein diversity,poly-morphism at R loci in wild plants and lack thereof in crops,and the suite of cellular responses that follow R protein activation 1.We hypothesized that many plant R proteins might be activated indir-ectly by pathogen-encoded effectors,and not by direct recognition.This ‘guard hypothesis’implies that R proteins indirectly recognize pathogen effectors by monitoring the integrity of host cellular targets of effector action 1,4.The concept that R proteins recognize ‘patho-gen-induced modified self’is similar to the recognition of ‘modified self’in ‘danger signal’models of the mammalian immune system 5.It is now clear that there are,in essence,two branches of the plant immune system.One uses transmembrane pattern recognition receptors (PRRs)that respond to slowly evolving microbial-or pathogen-associated molecular patterns (MAMPS or PAMPs),such as flagellin 6.The second acts largely inside the cell,using the poly-morphic NB-LRR protein products encoded by most R genes 1.They are named after their characteristic nucleotide binding (NB)and leucine rich repeat (LRR)domains.NB-LRR proteins are broadly related to animal CATERPILLER/NOD/NLR proteins 7and STAND ATPases 8.Pathogen effectors from diverse kingdoms are recognized by NB-LRR proteins,and activate similar defence responses.NB-LRR-mediated disease resistance is effective against pathogens that can grow only on living host tissue (obligate biotrophs),or hemi-biotrophic pathogens,but not against pathogens that kill host tissue during colonization (necrotrophs)9.

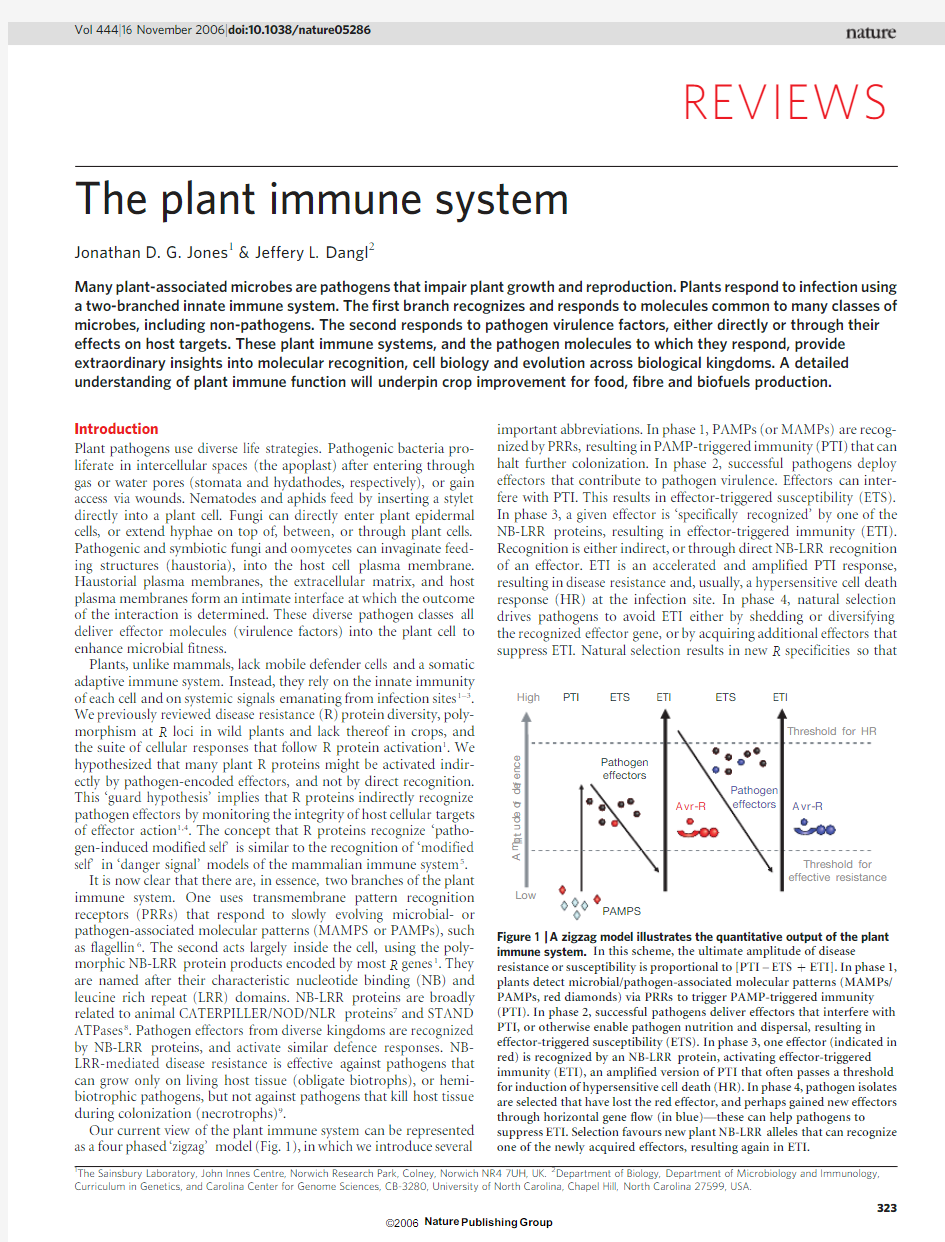

Our current view of the plant immune system can be represented as a four phased ‘zigzag’model (Fig.1),in which we introduce several

important abbreviations.In phase 1,PAMPs (or MAMPs)are recog-nized by PRRs,resulting in PAMP-triggered immunity (PTI)that can halt further colonization.In phase 2,successful pathogens deploy effectors that contribute to pathogen virulence.Effectors can inter-fere with PTI.This results in effector-triggered susceptibility (ETS).In phase 3,a given effector is ‘specifically recognized’by one of the NB-LRR proteins,resulting in effector-triggered immunity (ETI).Recognition is either indirect,or through direct NB-LRR recognition of an effector.ETI is an accelerated and amplified PTI response,resulting in disease resistance and,usually,a hypersensitive cell death response (HR)at the infection site.In phase 4,natural selection drives pathogens to avoid ETI either by shedding or diversifying the recognized effector gene,or by acquiring additional effectors that suppress ETI.Natural selection results in new R specificities so that

1

The Sainsbury Laboratory,John Innes Centre,Norwich Research Park,Colney,Norwich NR47UH,UK.2Department of Biology,Department of Microbiology and Immunology,Curriculum in Genetics,and Carolina Center for Genome Sciences,CB-3280,University of North Carolina,Chapel Hill,North Carolina 27599,

USA.

ETS

ETI

ETS

ETI

High

PTI

Figure 1|A zigzag model illustrates the quantitative output of the plant immune system.In this scheme,the ultimate amplitude of disease

resistance or susceptibility is proportional to [PTI –ETS 1ETI].In phase 1,plants detect microbial/pathogen-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs/PAMPs,red diamonds)via PRRs to trigger PAMP-triggered immunity (PTI).In phase 2,successful pathogens deliver effectors that interfere with PTI,or otherwise enable pathogen nutrition and dispersal,resulting in effector-triggered susceptibility (ETS).In phase 3,one effector (indicated in red)is recognized by an NB-LRR protein,activating effector-triggered immunity (ETI),an amplified version of PTI that often passes a threshold for induction of hypersensitive cell death (HR).In phase 4,pathogen isolates are selected that have lost the red effector,and perhaps gained new effectors through horizontal gene flow (in blue)—these can help pathogens to

suppress ETI.Selection favours new plant NB-LRR alleles that can recognize one of the newly acquired effectors,resulting again in ETI.

Vol 444j 16November 2006j doi:10.1038/nature05286

323

ETI can be triggered again.Below,we review each phase in turn,we update the experimental validation of the‘guard hypothesis’,and we consider future challenges in understanding and manipulating the plant immune system.We will not discuss the small RNA-based plant immune system active against viruses10or the active response of plants to herbivores11.

Microbial patterns and plant pattern recognition

We define basal disease resistance as that activated by virulent patho-gens on susceptible hosts.Thus,basal disease resistance is,at first glance,PTI minus the effects of ETS;however,there is also likely to be weak ETI triggered by weak recognition of effectors,as detailed below.Hence,the most accurate definition of basal defence would be‘PTI plus weak ETI,minus ETS’.The archetypal elicitor of PTI is bacterial flagellin,which triggers defence responses in various plants12.Flagellum-based motility is important for bacterial patho-genicity in plants6.A synthetic22-amino-acid peptide(flg22)from a conserved flagellin domain is sufficient to induce many cellular res-ponses13including the rapid(,1h)transcriptional induction of at least1,100Arabidopsis thaliana(hereafter Arabidopsis)genes14.A genetic screen using flg22defined the Arabidopsis LRR-receptor kinase FLS2,which binds flg22(ref.15).FLS2and mammalian TLR5recognize different flagellin domains6.FLS2is internalized fol-lowing stimulation by a receptor-mediated endocytic process that presumably has regulatory functions16.fls2mutants exhibit enhanced sensitivity to spray application of pathogenic Pseudomonas syringae pv.tomato DC3000(Pto DC3000),but not to syringe infiltration into the leaf apoplast14,17,suggesting that FLS2acts early against pathogen invasion.

Bacterial cold shock proteins and elongation factor Tu(EF-Tu) activate similar defence responses to flg22(refs18–20).Ef-Tu is recognized by an Arabidopsis LRR-kinase called EFR(ref.20).efr mutants support higher levels of transient transformation with Agrobacterium,suggesting that PTI might normally limit Agrobact-erium pathogenicity.Treatment with a conserved EF-Tu peptide induces expression of a gene set nearly identical to that induced by flg22(ref.20).Conversely,EFR transcription is induced by flg22. Hence,the responses to MAMPs/PAMPs converge on a limited num-ber of signalling pathways and lead to a common set of outputs that comprise PTI.Remarkably,mutations in genes required for NB-LRR function have no effect on early responses to flg22(ref.14).Thus, NB-LRR-dependent signalling and MAMP/PAMP-mediated signal-ling require partially distinct components.

Molecules that induce PTI are not easily discarded by the microbes that express them.Yet flagellin from various Xanthomonas campestris pv.campestris strains is variably effective in triggering FLS2-mediated PTI in Arabidopsis,and flagellin from Agrobacterium tumefaciens or Sinorhizobium meliloti is less active than that from P.syringae13.Ef-Tu from Pto DC3000is much less active in eliciting PTI in Arabidopsis than is Ef-Tu from Agrobacterium19.Limited variation also exists in PAMP responsiveness within a plant species.Arabidopsis accession Ws-0carries a point mutation in FLS2,rendering it non-responsive to flg22(ref.12).In fact,individual plant species recognize only a subset of potential PAMPs(ref.6).Neither PAMPs nor PRRs are invariant,and each can be subject to natural selection. Additional MAMPs/PAMPs and corresponding PRRs must exist, since Agrobacterium extracts elicit PTI on an fls2efr-1double mutant (ref.20).Other LRR kinases may encode additional PRRs whose transcription is stimulated by engagement of related PRRs.There are over200LRR-kinases in the Arabidopsis Col-0genome21;28of these are induced within30min of flg22treatment14.FLS2and EFR are members of an atypical kinase family that might have a plant immune system specific function22.There are also56Arabidopsis receptor-like proteins(RLPs)that encode type I transmembrane proteins with LRR ectodomains,but no intracellular kinase domains23.MAMP/PAMP elicitation might‘prime’further defence responses by elevating responsiveness to other microbial patterns14.Successful pathogens suppress PTI

What does a would-be pathogen,using its collection of effectors, need to achieve?Some effectors may serve structural roles,for example,in the extrahaustorial matrix that forms during fungal and oomycete infection24.Others may promote nutrient leakage or pathogen dispersal25.Many are likely to contribute to suppression of one or more components of PTI or ETI.The extent to which ETI and PTI involve distinct mechanisms is still an open question,and some effectors may target ETI rather than PTI,or vice versa(Fig.1). Plant pathogenic bacteria deliver15–30effectors per strain into host cells using type III secretion systems(TTSS).Bacterial effectors contribute to pathogen virulence,often by mimicking or inhibiting eukaryotic cellular functions26–28.A pathogenic P.syringae strain mutated in the TTSS,and unable to deliver any type III effectors, triggers a faster and stronger transcriptional re-programming in bean than does the isogenic wild-type strain29.This strain,representing the sum of all bacterial MAMPs/PAMPs,induces transcription of essen-tially the same genes as flg22(refs30–32).Hence,the type III effectors from any successful bacterial pathogen dampen PTI sufficiently to allow successful colonization33(Fig.1).

Excellent reviews discuss cellular processes targeted by bacterial type III effectors26–28,34;we highlight only new examples.The P.syr-ingae HopM effector targets at least one ARF-GEF protein likely to be involved in host cell vesicle transport35.HopM functions redundantly with the unrelated effector AvrE in P.syringae virulence36suggesting that manipulation of host vesicle transport is important for success-ful bacterial colonization.AvrPto and AvrPtoB are unrelated type III effectors that may contribute to virulence by inhibiting early steps in PTI,upstream of MAPKKK(ref.37).Like other type III effectors, AvrPtoB is a bipartite protein.The amino terminus contributes to virulence;the carboxy terminus may have a function in blocking host cell death38,39.A domain from the AvrPtoB C terminus folds into an active E3ligase,suggesting that its function involves host protein degradation40.The Yersinia effector YopJ,a member of the AvrRxv family of effectors from phytopathogenic bacteria,inhibits MAP kinase cascades by acetylation of phosphorylation-regulated residues on a MEK protein41.Many additional bacterial type III effectors protein families have been identified26–28;their targets and functions await definition.

Effectors from plant pathogens that are eukaryotic are poorly understood.Fungal and oomycete effectors can act either in the extracellular matrix or inside the host cell.For example,the tomato RLPs,Cf-2,Cf-4,Cf-5and Cf-9respond specifically to extracellular effectors produced by Cladosporium fulvum42.Other fungal and oomycete effectors probably act inside the host cell;they are recog-nized by NB-LRR proteins.For example,the gene encoding the oomycete effector Atr13from Hyaloperonospora parasitica exhibits extensive allelic diversity between H.parasitica strains matched by diversity at the corresponding Arabidopsis RPP13NB-LRR locus43. Diversity is also observed across H.parasitica Atr1and Arabidopsis RPP1alleles44.Atr1and Atr13carry signal peptides for secretion from H.parasitica.They share with each other,and with the Phytophthora infestans Avr3a protein,an RxLR motif,that enables import of Plasmodium effectors into mammalian host cells45.This is consistent with the taxonomic proximity of oomycetes and Plasmodium.Races of the flax rust fungus Melampsora lini express Avr genes recognized by specific alleles of the flax L,M and P NB-LRR proteins.These haustorial proteins carry signal peptides for fungal export and can function inside the plant cell46,47.How they are taken up by the host cell is unknown.However,the barley powdery mildew(Blumeria graminis f.sp.hordei)Avrk and Avra10proteins,recognized by the NB-LRR barley genes Mlk and Mla10,contain neither obvious signal peptides nor RxLR motifs,yet are members of large gene families in Blumeria and Erysiphe species48.How these oomycete and fungal effectors are delivered to the host cell and contribute to pathogen virulence is unknown.

REVIEWS NATURE j Vol444j16November2006 324

Pathogens produce small molecule effectors that mimic plant hor-mones.Some P syringae strains make coronatine,a jasmonic acid mimic that suppresses salicylic-acid-mediated defence to biotrophic pathogens49,50and induces stomatal opening,helping pathogenic bacteria gain access to the apoplast51.PTI involves repression of auxin responses,mediated in part by a micro-RNA that is also induced during abscisic-acid-mediated stress responses52.Gibberellin is pro-duced by the fungal pathogen Gibberella fujikuroi leading to‘foolish seedling’syndrome,and cytokinin produced by many pathogens can promote pathogen success through retardation of senescence in infected leaf tissue.The interplay between PTI and normal hormone signalling,and pathogen mimics that influence it,is just beginning to be unravelled.

Indirect and direct host recognition of pathogen effectors Effectors that enable pathogens to overcome PTI are recognized by specific disease resistance(R)genes.Most R genes encode NB-LRR proteins;there are,125in the Arabidopsis Col-0genome.If one effector is recognized by a corresponding NB-LRR protein,ETI ensues.The recognized effector is termed an avirulence(Avr)pro-tein.ETI is a faster and stronger version of PTI30–32that often culmi-nates in HR53(Fig.1).HR typically does not extend beyond the infected cell:it may retard pathogen growth in some interactions, particularly those involving haustorial parasites,but is not always observed,nor required,for ETI.It is unclear what actually stops pathogen growth in most cases.

Very little is known about the signalling events required to activate NB-LRR-mediated ETI.NB-LRR proteins are probably folded in a signal competent state by cytosolic heat shock protein90and other receptor co-chaperones54,55.The LRRs seem to act as negative regu-lators that block inappropriate NB activation.NB-LRR activation involves intra-and intermolecular conformational changes and may resemble the induced proximity mechanism by which the related animal Apaf-1protein activates programmed cell death56. NB-LRR activation results in a network of cross-talk between res-ponse pathways deployed,in part,to differentiate biotrophic from necrotrophic pathogen attack9.This is maintained by the balance between salicylic acid,a local and systemic signal for resistance against many biotrophs,and the combination of jasmonic acid and ethylene accumulation as signals that promote defence against necro-trophs9.Additional plant hormones are likely to alter the salicylic-acid–jasmonic-acid/ethylene signalling balance.Arabidopsis mutants defective in salicylic acid biosynthesis or responsiveness are compro-mised in both basal defence and systemic acquired resistance(SAR)57. NB-LRR activation induces differential salicylic-acid-and ROS-dependent responses at and surrounding infection sites,and system-ically58.The NADPH-oxidase-dependent oxidative burst that accom-panies ETI represses salicylic acid-dependent cell death spread in cells surrounding infection sites59.Local and systemic changes in gene expression are mediated largely by transcription factors of the WRKY and TGA families60.

Several NB-LRR proteins recognize type III effectors indirectly,by detecting products of their action on host targets,consistent with the ‘guard hypothesis’1.The key tenets of this hypothesis are that:(1)an effector acting as a virulence factor has a target(s)in the host;(2)by manipulating or altering this target(s)the effector contributes to pathogen success in susceptible host genotypes;and(3)effector per-turbation of a host target generates a‘pathogen-induced modified-self’molecular pattern,which activates the corresponding NB-LRR protein,leading to ETI.Three important consequences of this model, now supported by experimental evidence,are that:(1)multiple effec-tors could evolve independently to manipulate the same host target, (2)this could drive the evolution of more than one NB-LRR protein associated with a target of multiple effectors,and(3)these NB-LRRs would be activated by recognition of different modified-self patterns produced on the same target by the action of the effectors in(1).

RIN4,a211-amino-acid,acylated61and plasma-membrane-asso-ciated protein,is an archetypal example of a host target of type III effectors that is guarded by NB-LRR proteins(Fig.2).It is manipu-lated by three different bacterial effectors,and associates in vivo with two Arabidopsis NB-LRR proteins(Fig.2a and2b).Two unrelated type III effectors,AvrRpm1and AvrB,interact with and induce phos-phorylation of RIN4(ref.62).This RIN4modification is predicted to activate the RPM1NB-LRR protein.A third effector,AvrRpt2is a cysteine protease63,activated inside the host cell64,that eliminates RIN4by cleaving it at two sites61,65.Cleavage of RIN4activates the RPS2NB-LRR protein66,67.Activation of both RPM1and RPS2 requires the GPI-anchored NDR1protein,and RIN4interacts with NDR168.

If RIN4was the only target for these three effectors,then its elim-ination would abolish their ability to add virulence to a weakly patho-genic strain.However,elimination of RIN4demonstrated that it is not the only host target for AvrRpm1or AvrRpt2in susceptible(rin4 rpm1rps2)plants69.Additionally,AvrRpt2can cleave in vitro several Arabidopsis proteins that contain its consensus cleavage site65.Hence, any effector’s contribution to virulence might involve manipulation of several host targets,and the generation of several modified-self molecules.However,the perturbation of only one target is sufficient for NB-LRR activation.RIN4negatively regulates RPS2and RPM1 (and only these two NB-LRR proteins)69,70.But what is the function of RIN4in the absence of RPS2and RPM1?In rpm1rps2plants, AvrRpt2or AvrRpm1(and possibly other effectors)manipulate RIN4(and possibly associated proteins or other targets)in order to suppress PTI71.Thus,plants use NB-LRR proteins to guard against pathogens that deploy effectors to inhibit PAMP-signalling.Addi-tional examples of indirect recognition are detailed in Fig.2;these include both intra-and extra-cellular recognition of pathogen-induced modified self.

Not all NB-LRR recognition is indirect,and there are three exam-ples of direct Avr-NB-LRR interaction72–74.The flax L locus alleles encode NB-LRR proteins that interact in yeast with the correspond-ing AvrL proteins,providing the first evidence that effector diversity determining NB-LRR recognition can be correlated perfectly with effector–NB-LRR-protein interaction72.Both L and AvrL proteins are under diversifying selection,arguing for a direct evolutionary arms race.The allelic diversity of other fungal and oomycete patho-gen effectors,and of their corresponding host NB-LRR proteins as described above,also suggests direct interaction,though this remains to be demonstrated.

The evolutionary radiation of several hundred thousand angio-sperm plant species,140–180million years ago was probably accompanied by many independent cases of pathogen co-evolution, particularly of host-adapted obligate biotrophs.Most plants resist infection by most pathogens;they are said to be‘non-hosts’.This non-host resistance could be mediated by at least two mechanisms. First,a pathogen’s effectors could be ineffective on a potential new, but evolutionarily divergent,host,resulting in little or no suppres-sion of PTI,and failure of pathogen growth.Alternatively,one or more of the effector complement of the would-be pathogen could be recognized by the NB-LRR repertoire of plants other than its co-adapted host,resulting in ETI.These two scenarios predict different outcomes with respect to the timing and amplitude of the response they would trigger,and they also give rise to different evolutionary pressures on both host and pathogen.

Non-host resistance in Arabidopsis against the non-adapted barley pathogen,B.graminis f.sp.hordei(Bgh)normally involves the rapid production of cell wall appositions(physical barriers)and anti-microbial metabolites at the site of pathogen entry,but no HR. Arabidopsis penetration(pen)mutants are partially compromised in this response.PEN2is a peroxisomal glucosyl hydrolase75,and PEN3encodes a plasma membrane ABC transporter76.PEN2and PEN3are both recruited to attempted fungal entry sites,apparently to mediate the polarized delivery of a toxin to the apoplast75,76.The

NATURE j Vol444j16November2006REVIEWS

325

actin cytoskeleton probably contributes to this response 77,perhaps as a track for PEN2-containing peroxisomes and/or vesicles.This pre-invasion non-host resistance is genetically separable from a post-invasion mechanism that requires additional elements that regulate both PTI and ETI 78.Elimination of both PEN2and PTI/ETI signal-ling transforms Arabidopsis into a host for an evolutionarily non-adapted fungal pathogen 75.This suggests that non-host resistance comprises mechanistically distinct layers of resistance.

The PEN1syntaxin acts in a different pre-invasion non-host res-istance pathway.PEN1is likely to be part of a ternary SNARE com-plex that secretes vesicle cargo to the site of attempted fungal invasion,contributing to formation of cell wall appositions 79–81.Specific seven-transmembrane MLO (mildew resistance locus O)family members negatively regulate PEN1-dependent secretion at sites of attempted pathogen ingress 79,80.Recessive mlo mutations in either Arabidopsis or barley result in resistance to the respective co-evolved powdery mildew pathogens 82.Hence,in both Arabidopsis and barley,these fungi might suppress PEN1-mediated disease res-istance by activation of MLO.This remarkable set of findings implies that a common host cell entry mechanism evolved in powdery mil-dew fungi at or before the monocot–dicot divergence.PEN2and PEN3genes are induced by flg22,indicating that they might be involved in PTI.

Non-host resistance can also be mediated by parallel ETI res-ponses.For example,four bacterial effectors from a tomato pathogen

Less pathogen growth

(RIN4

RIN4

a

b

to AvrRpm1 activity on RIN4 and other targets

+P +P

+P

+P +P

+P

+P

+P Less pathogen growth

(rps2RIN4 and other targets

c

Less pathogen growth

(rps5d

Less pathogen growth

(prf e

Activation of Cf-2-dependent

defence response

host

host

Inhibition of Rcr3 protease activity by the Avr2 protease inhibitor contributes to disease

Figure 2|Plant immune system activation by pathogen effectors that generate modified self molecular patterns.a ,Arabidopsis RPM1is a

peripheral plasma membrane NB-LRR protein.It is activated by either the AvrRpm1or the AvrB effector proteins.AvrRpm1enhances the virulence of some P.syringae strains on Arabidopsis as does AvrB on soybeans.AvrRpm1and AvrB are modified by eukaryote-specific acylation once delivered into the cell by the type III secretion system (red syringe)and are thus targeted to the plasma membrane.The biochemical functions of AvrRpm1and AvrB are unknown,although they target RIN4,which becomes phosphorylated (1P),and activate RPM1,as detailed in the text.In the absence of RPM1,AvrRpm1and AvrB presumably act on RIN4and other targets to contribute to virulence.Light blue eggs in this and subsequent panels represent as yet unknown proteins.b ,RPS2is an NB-LRR protein that resides at the plasma membrane.It is activated by the AvrRpt2cysteine protease type III effector from P.syringae .Auto-processing of AvrRpt2by a host cyclophilin reveals a consensus,but unconfirmed,myristoylation site at the new amino terminus,suggesting that it might also be localized to the host plasma membrane.AvrRpt2is the third effector that targets RIN4.Cleavage of RIN4by AvrRpt2leads to RPS2-mediated ETI.In the absence of RPS2,AvrRpt2presumably cleaves RIN4and other targets as part of its virulence function.c ,RPS5is an Arabidopsis NB-LRR protein localized to a membrane fraction,probably via acylation.RPS5is NDR1-independent.It is activated by the AvrPphB cysteine protease effector from P.syringae 100.AvrPphB is cleaved,acylated and delivered to the host plasma membrane.Activated AvrPphB cleaves the Arabidopsis PBS1serine-threonine protein kinase,leading to RPS5activation.The catalytic activity of cleaved PBS1is required for RPS5

activation,suggesting that this ‘modified-self’fragment retains its enzymatic activity as part of the RPS5activation mechanism 100.To date,no function has been ascribed to PBS1in the absence of RPS5.d ,Pto is a tomato serine-threonine protein kinase.Pto is polymorphic and hence satisfies the genetic criteria for the definition of a disease resistance protein.Pto activity requires the NB-LRR protein Prf,and the proteins form a molecular complex 101.Prf is monomorphic,at least in the tomato species analysed to date.Pto is the direct target of two unrelated P.syringae effectors,AvrPto and AvrPtoB,each of which contributes to pathogen virulence in pto mutants 102.It is thus likely that Prf guards Pto (refs 101,103).The Pto kinase is apparently not required for PTI,though there may be redundancy in its function because it is a member of a gene family.e ,The transmembrane RLP Cf-2guards the extracellular cysteine protease Rcr3.Cf-2recognizes the C.fulvum

extracellular effector Avr2,which encodes a cysteine protease inhibitor.Avr2binds and inhibits the tomato Rcr3cysteine protease.Mutations in Rcr3result in the specific loss of Cf-2-dependent recognition of Avr2.Hence,Cf-2seems to monitor the state of Rcr3,and activates defence if Rcr3is inhibited by Avr2(ref.104).

REVIEWS

NATURE j Vol 444j 16November 2006

326

unable to colonize soybean can each trigger specific soybean R genes when delivered from a soybean pathogen 83.Deletion of these effector genes from the tomato pathogen diminishes its virulence on tomato,but does not allow it to colonize soybean 84.Hence,there might be other factors lacking in this strain that are required to colonize soy-bean.Also,a widely distributed,monomorphic effector acting as an avirulence protein is sufficient to render Magnaporthe oryzae strains unable to colonize rice.Its presence in over 50strains that successfully colonize perennial ryegrass suggests a virulence function 85.Finally,Arabidopsis non-host resistance to Leptosphaeria maculans ,a fungal pathogen of Brassica ,is actually mediated by unlinked NB-LRR pro-teins present in each parent of a cross between two accessions 86.Hence,cryptic NB-LRR mediated responses acting in parallel can limit pathogen host range.

Pathogens dodge host surveillance

The effectiveness of ETI selects for microbial variants that can avoid NB-LRR-mediated recognition of a particular effector (Fig.3).Effector allele frequencies are likely to be influenced by their mode of action.The diversity of both flax rust AvrL alleles and oomycete Atr13and Atr1alleles suggests one means of effector evolution.These proteins are likely to interact directly in planta with proteins encoded by alleles of the flax L and Arabidopsis RPP1and RPP13loci,respect-ively.The high level of diversifying selection among these effector alleles is presumably selected by host recognition,and hence acts on effector residues that are probably not required for effector function.In contrast,effectors providing biochemical functions that gen-erate modifications of host targets are likely to be under purifying selection 87.NB-LRR activation via recognition of pathogen-induced modified self provides a mechanism for host perception of multiple effectors evolved to compromise the same host target (Fig.2).For selection to generate an effector that escapes ETI,the effector is likely to lose its nominal function.The simplest pathogen response to host recognition is to jettison the detected effector gene,provided the population’s effector repertoire can cover the potential loss of fitness

on susceptible hosts.In fact,effector genes are often associated with mobile genetic elements or telomeres and are commonly observed as presence/absence polymorphisms across bacterial and fungal strains.Indirect recognition of effector action,via recognition of pathogen-induced modified self,is likely to enable relatively stable,durable and evolutionarily economic protection of the set of cellular machinery targeted by pathogen effectors.

ETI can also be overcome through evolution of pathogen effectors that suppress it directly (Fig.1).For example,in P.syringae pv.phaseolicola,the AvrPphC effector suppresses ETI triggered by the AvrPphF effector in some cultivars of bean,whereas,as its name implies,AvrPphC itself can condition avirulence on different bean cultivars 88.Other cases of bacterial effectors acting to dampen or inhibit ETI have been observed 38.Genetic analysis in flax rust revealed so-called inhibitor genes that function to suppress ETI trig-gered by other avirulence genes 89.Hence,it seems likely that some effectors suppress the ETI triggered by other effectors.

Microbial evolution in response to ETI may result in two extremes of NB-LRR evolution.NB-LRR gene homologues in diverse Arabidopsis accessions accumulate evolutionary novelty at different rates at different loci 90.Some NB-LRR genes are not prone to duplica-tion,and are evolving relatively slowly.Their products are perhaps stably associated with a host protein whose integrity they monitor,retarding diversification.Others are evolving more rapidly and may interact directly with rapidly evolving effectors 91,92.What might drive these evolutionary modes (Fig.3)?In pathogen populations,the frequency of an effector gene will be enhanced by its ability to pro-mote virulence,and reduced by host recognition.For example,in the flax/flax rust system,avirulence gene frequency in the rust is elevated on plant populations with a lower abundance of the corresponding R genes,consistent with avr genes increasing pathogen fitness 93.Hence,natural selection should maintain effector function in the absence of recognition.But effector function has a cost that is dependent on the frequency of the corresponding R gene.And R genes may exact a fitness cost in the host 94.Thus,if effector frequency drops in a patho-gen population,hosts might be selected for loss of the corresponding R allele,and the frequency-dependent cycle would continue (Fig.3).

Challenges and opportunities for the future

We need to define the repertoire and modes of action of effectors from pathogens with diverse life histories.This will help to define the comprehensive set of host targets,as well as the evolutionary pres-sures acting on both hosts and pathogens.For example,if the major-ity of bacterial effectors evolve under purifying selection to maintain intrinsic function 87,then a population-wide set of unrelated micro-bial effectors might converge onto a limited set of NB-LRR-asso-ciated host targets.These stable associations of NB-LRR proteins and the host proteins whose integrity they monitor are presumably being challenged by newly evolved,or newly acquired,effectors that can still surreptitiously manipulate the target in the service of viru-lence.

We need to understand the haustorial interface.Rewiring of host and microbe vesicle traffic will probably underpin haustorial differ-entiation.We do not yet know whether the extrahaustorial mem-brane is derived from the host plasma membrane or is a newly synthesized,novel host membrane.High-throughput sequencing renders it feasible to index the gene complements of obligate bio-trophs like powdery and downy mildews,and rusts.Genomics can be also be used to identify the genes expressed by the pathogen over a time course of infection.The presence of a signal peptide and (in the case of oomycetes)an RxLR motif,can then be used to computa-tionally identify the complement of effector candidates.With the development of appropriate high-throughput delivery systems,it will be possible to investigate their functions,and their ability to impinge on PTI and/or ETI,on both host plants and other plant species.Do the transcriptional controls of PTI and ETI,which culminate in similar outputs,overlap?Several effectors can be nuclear localized 95,96

.

Selection for Resisted pathogen Resistant plants R1 at high frequency

E1

for Mutated or jettisoned E1

Ineffective R1Sensitive plants

Virulent pathogen R1Sensitive plants Virulent pathogen Sensitive plants R1 at low frequency

Figure 3|Co-evolution of host R genes and the pathogen effector

complement.A pathogen carries an effector gene (E1)that is recognized by a rare R1allele (top).This results in selection for an elevated frequency of R1in the population.Pathogens in which the effector is mutated are then selected,because they can grow on R1-containing plants (right).R1effectiveness erodes,and,because at least some R genes have associated fitness costs 94,plants carrying R1can have reduced fitness (bottom),resulting in reduced R1frequencies.The pathogen population will still contain individuals with E1.In the absence of R1,E1will confer increased fitness,and its frequency in the population will increase (left).This will lead to resumption of selection for R1(top).In populations of plants and pathogens,this cycle is continuously turning,with scores of effectors and many alleles at various R loci in play.

NATURE j Vol 444j 16November 2006

REVIEWS

327

The RRS1R protein is perhaps a Rosetta Stone chimaera of NB-LRR and WRKY transcription factor74.A TATA-binding protein accessory factor,AtTIP49a,interacts with RPM1and other NB-LRR proteins, and is a negative regulator of defence97.Two nucleoporins and impor-tins are required for the output response of an ectopically activated NB-LRR protein98,99.Notably,the prototypic animal CATERPILLAR protein is CIITA,a transcriptional co-activator of MHC class II res-ponse to viral infection that is,in turn,the target of viral proteins that aim to shut it down7.Whether NB-LRR proteins are transcriptional co-regulators is at present unknown.

We need to know what causes pathogen growth arrest.Because plants are sessile,they must continuously integrate both biotic and abiotic signals from the environment.Plants lack circulating cells,so these responses also need to be partitioned both locally over several cell diameters and systemically over metres.Understanding the spa-tial interplay of PTI,ETI,and plant hormone and abiotic stress-signalling systems is in its infancy.

Finally,we need to understand the population biology of pathogen effectors,and their co-evolving host NB-LRR genes.Knowledge of their allele frequencies and their spatial distribution in wild ecosys-tems should tell us more about the evolution of this fascinating ancient immune system and how we might deploy it more effectively to control disease.

1.Dangl,J.L.&Jones,J.D.G.Plant pathogens and integrated defence responses to

infection.Nature411,826–833(2001).

2.Ausubel,F.M.Are innate immune signaling pathways in plants and animals

conserved?Nature Immunol.6,973–979(2005).

3.Chisholm,S.T.,Coaker,G.,Day,B.&Staskawicz,B.J.Host–microbe interactions:

shaping the evolution of the plant immune response.Cell124,803–814(2006).

4.van der Biezen,E.A.&Jones,J.D.G.Plant disease resistance proteins and the

gene-for-gene concept.Trends Biochem.Sci.23,454–456(1998).

5.Matzinger,P.The danger model:a renewed sense of self.Science296,301–305

(2002).

6.Zipfel,C.&Felix,G.Plants and animals:a different taste for microbes?Curr.Opin.

Plant Biol.8,353–360(2005).

7.Ting,J.P.&Davis,B.K.CATERPILLER:a novel gene family important in immunity,

cell death,and diseases.Annu.Rev.Immunol.23,387–414(2005).

8.Leipe,D.D.,Koonin,E.V.&Aravind,L.STAND,a class of P-loop NTPases

including animal and plant regulators of programmed cell death:multiple,

complex domain architectures,unusual phyletic patterns,and evolution by

horizontal gene transfer.J.Mol.Biol.343,1–28(2004).

9.Glazebrook,J.Contrasting mechanisms of defense against biotrophic and

necrotrophic pathogens.Annu.Rev.Phytopathol.43,205–227(2005).

10.Voinnet,O.Induction and suppression of RNA silencing:insights from viral

infections.Nature Rev.Genet.6,206–220(2005).

11.Kessler,A.&Baldwin,I.T.Plant responses to insect herbivory:the emerging

molecular analysis.Annu.Rev.Plant Biol.53,299–328(2002).

12.Gomez-Gomez,L.&Boller,T.Flagellin perception:a paradigm for innate

immunity.Trends Plant Sci.7,251–256(2002).

13.Felix,G.,Duran,J.D.,Volko,S.&Boller,T.Plants have a sensitive perception

system for the most conserved domain of bacterial flagellin.Plant J.18,265–276 (1999).

14.Zipfel,C.et al.Bacterial disease resistance in Arabidopsis through flagellin

perception.Nature428,764–767(2004).

15.Chinchilla,D.,Bauer,Z.,Regenass,M.,Boller,T.&Felix,G.The Arabidopsis

receptor kinase FLS2binds flg22and determines the specificity of flagellin

perception.Plant Cell18,465–476(2006).

16.Robatzek,S.,Chinchilla,D.&Boller,T.Ligand-induced endocytosis of the pattern

recognition receptor FLS2in Arabidopsis.Genes Dev.20,537–542(2006). 17.Sun,W.,Dunning,F.M.,Pfund,C.,Weingarten,R.&Bent,A.F.Within-species

flagellin polymorphism in Xanthomonas campestris pv campestris and its impact on elicitation of Arabidopsis FLAGELLIN SENSING2-dependent defenses.Plant Cell18, 764–779,doi:10.1105/tpc.105.037648(2006).

18.Felix,G.&Boller,T.Molecular sensing of bacteria in plants.The highly conserved

RNA-binding motif RNP-1of bacterial cold shock proteins is recognized as an elicitor signal in tobacco.J.Biol.Chem.278,6201–6208(2003).

19.Kunze,G.et al.The N terminus of bacterial elongation factor Tu elicits innate

immunity in Arabidopsis plants.Plant Cell16,3496–3507(2004).

20.Zipfel,C.et al.Perception of the bacterial PAMP EF-Tu by the receptor EFR

restricts Agrobacterium-mediated transformation.Cell125,749–760(2006). 21.Shiu,S.H.&Bleecker,A.B.Expansion of the receptor-like kinase/Pelle gene

family and receptor-like proteins in Arabidopsis.Plant Physiol.132,530–543

(2003).

22.Dardick,C.&Ronald,P.Plant and animal pathogen recognition receptors signal

through non-RD kinases.PLoS Pathog2,e2(2006).23.Fritz-Laylin,L.K.,Krishnamurthy,N.,Tor,M.,Sjolander,K.V.&Jones,J.D.

Phylogenomic analysis of the receptor-like proteins of rice and Arabidopsis.Plant Physiol.138,611–623(2005).

24.Schulze-Lefert,P.&Panstruga,R.Establishment of biotrophy by parasitic fungi

and reprogramming of host cells for disease resistance.Annu.Rev.Phytopathol.41, 641–667(2003).

25.Badel,J.L.,Charkowski,A.O.,Deng,W.L.&Collmer,A.A gene in the

Pseudomonas syringae pv.tomato Hrp pathogenicity island conserved effector locus,hopPtoA1,contributes to efficient formation of bacterial colonies in planta and is duplicated elsewhere in the genome.Mol.Plant Microbe Interact.15,

1014–1024(2002).

26.Grant,S.R.,Fisher,E.J.,Chang,J.H.,Mole,B.M.&Dangl,J.L.Subterfuge and

manipulation:type III effector proteins of phytopathogenic bacteria.Annu.Rev.

Microbiol.60,425–449,doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.60.080805.142251(2006).

27.Abramovitch,R.B.,Anderson,J.C.&Martin,G.B.Bacterial elicitation and evasion

of plant innate immunity.Nature Rev.Mol.Cell Biol.7,601–611(2006).

28.Mudgett,M.B.New insights to the function of phytopathogenic bacterial type III

effectors in plants.Annu.Rev.Plant Biol.56,509–531(2005).

29.Jakobek,J.L.,Smith,J.A.&Lindgren,P.B.Suppression of bean defense responses

by Pseudomonas syringae.Plant Cell5,57–63(1993).

30.Thilmony,R.,Underwood,W.&He,S.Y.Genome-wide transcriptional analysis of

the Arabidopsis thaliana interaction with the plant pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv.tomato DC3000and the human pathogen Escherichia coli O157:H7.Plant J.46, 34–53(2006).

31.Tao,Y.et al.Quantitative nature of Arabidopsis responses during compatible and

incompatible interactions with the bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas syringae.Plant Cell15,317–330(2003).

32.Truman,W.,de Zabala,M.T.&Grant,M.Type III effectors orchestrate a complex

interplay between transcriptional networks to modify basal defence responses during pathogenesis and resistance.Plant J.46,14–33(2006).

33.Nomura,K.,Melotto,M.&He,S.Y.Suppression of host defense in compatible

plant–Pseudomonas syringae interactions.Curr.Opin.Plant Biol.8,361–368

(2005).

34.Desveaux,D.,Singer,A.U.&Dangl,J.L.Type III effector proteins:doppelgangers

of bacterial virulence.Curr.Opin.Plant Biol.9,376–382(2006).

35.Nomura,K.et al.A bacterial virulence protein suppresses host innate immunity to

cause plant disease.Science313,220–223,doi:10.1126/science.1129523(2006).

36.DebRoy S.,Thilmony,R.,Kwack,Y-B.,Nomura,K.&He,S.Y.A family of conserved

bacterial effectors inhibits salicylic acid-mediated basal immunity and promotes disease necrosis in plants.Proc.Natl https://www.360docs.net/doc/b0254483.html,A101,9927–9932(2004). 37.He,P.et al.Specific bacterial suppressors of MAMP signaling upstream of

MAPKKK in Arabidopsis innate immunity.Cell125,563–575(2006).

38.Abramovitch,R.B.,Kim,Y.J.,Chen,S.,Dickman,M.B.&Martin,G.B.

Pseudomonas type III effector AvrPtoB induces plant disease susceptibility by inhibition of host programmed cell death.EMBO J.22,60–69(2003).

39.de Torres,M.et al.Pseudomonas syringae effector AvrPtoB suppresses basal

defence in Arabidopsis.Plant J.47,368–382,10.1111/j.1365–313X.2006.02798.x (2006).

40.Janjusevic,R.,Abramovitch,R.B.,Martin,G.B.&Stebbins,C.E.A bacterial

inhibitor of host programmed cell death defenses is an E3ubiquitin ligase.Science 311,222–226(2006).

41.Mukherjee,S.et al.Yersinia YopJ acetylates and inhibits kinase activation by

blocking phosphorylation.Science312,1211–1214(2006).

42.Rivas,S.&Thomas,C.M.Molecular interactions between tomato and the leaf

mold pathogen Cladosporium fulvum.Annu.Rev.Phytopathol.43,395–436(2005).

43.Allen,R.L.et al.Host–parasite coevolutionary conflict between Arabidopsis and

downy mildew.Science306,1957–1960(2004).

44.Rehmany,A.P.et al.Differential recognition of highly divergent downy mildew

avirulence gene alleles by RPP1resistance genes from two Arabidopsis lines.Plant Cell17,1839–1850(2005).

45.Bhattacharjee,S.et al.The malarial host-targeting signal is conserved in the Irish

potato famine pathogen.PLoS Pathog2,e50(2006).

46.Dodds,P.N.,Lawrence,G.J.,Catanzariti,A.M.,Ayliffe,M.A.&Ellis,J.G.The

Melampsora lini AvrL567avirulence genes are expressed in haustoria and their products are recognized inside plant cells.Plant Cell16,755–768(2004).

47.Catanzariti,A.M.,Dodds,P.N.,Lawrence,G.J.,Ayliffe,M.A.&Ellis,J.G.

Haustorially expressed secreted proteins from flax rust are highly enriched for avirulence elicitors.Plant Cell18,243–256(2006).

49.Zhao,Y.et al.Virulence systems of Pseudomonas syringae pv.tomato promote

bacterial speck disease in tomato by targeting the jasmonate signaling pathway.

Plant J.36,485–499(2003).

50.Brooks,D.M.,Bender,C.L.&Kunkel,B.N.The Pseudomonas syringae phytotoxin

coronatine promotes virulence by overcoming salicylic acid-dependent defences in Arabidopsis thaliana.Mol.Plant Pathol.6,629–640(2005).

51.Melotto,M.,Underwood,W.,Koczan,J.,Nomura,K.&He,S.The innate immune

function of plant stomata against bacterial invasion.Cell126,969–980(2006).

52.Navarro,L.et al.A plant miRNA contributes to antibacterial resistance by

repressing auxin signaling.Science312,436–439(2006).

53.Greenberg,J.T.&Yao,N.The role and regulation of programmed cell death in

plant–pathogen interactions.Cell.Microbiol.6,201–211(2004).

54.Schulze-Lefert,P.Plant immunity:the origami of receptor activation.Curr.Biol.14,

R22–R24(2004).

REVIEWS NATURE j Vol444j16November2006 328

55.Holt,B.F.III,Belkhadir,Y.&Dangl,J.L.Antagonistic control of disease resistance

protein stability in the plant immune system.Science309,929–932(2005). 56.Takken,F.L.,Albrecht,M.&Tameling,W.I.Resistance proteins:molecular

switches of plant defence.Curr.Opin.Plant Biol.9,383–390(2006).

57.Durrant,W.E.&Dong,X.Systemic acquired resistance.Annu.Rev.Phytopathol.

42,185–209(2004).

58.Dorey,S.et al.Spatial and temporal induction of cell death,defense genes,and

accumulation of salicylic acid in tobacco leaves reacting hypersensitively to a fungal glycoprotein.Mol.Plant Microbe Interact.10,646–655(1997).

59.Torres,M.A.,Jones,J.D.&Dangl,J.L.Pathogen-induced,NADPH oxidase-

derived reactive oxygen intermediates suppress spread of cell death in

Arabidopsis thaliana.Nature Genet.37,1130–1134(2005).

60.Eulgem,T.Regulation of the Arabidopsis defense transcriptome.Trends Plant Sci.

10,71–78(2005).

61.Kim,H.S.et al.The Pseudomonas syringae effector AvrRpt2cleaves its

C-terminally acylated target,RIN4,from Arabidopsis membranes to block RPM1 activation.Proc.Natl https://www.360docs.net/doc/b0254483.html,A102,6496–6501(2005).

62.Mackey,D.,Holt,B.F.III,Wiig,A.&Dangl,J.L.RIN4interacts with Pseudomonas

syringae type III effector molecules and is required for RPM1-mediated disease resistance in Arabidopsis.Cell108,743–754(2002).

63.Axtell,M.J.,Chisholm,S.T.,Dahlbeck,D.&Staskawicz,B.J.Genetic and

molecular evidence that the Pseudomonas syringae type III effector protein

AvrRpt2is a cysteine protease.Mol.Microbiol.49,1537–1546(2003).

64.Coaker,G.,Falick,A.&Staskawicz,B.Activation of a phytopathogenic bacterial

effector protein by a eukaryotic cyclophilin.Science308,548–550(2005). 65.Chisholm,S.T.et al.Molecular characterization of proteolytic cleavage sites of

the Pseudomonas syringae effector AvrRpt2.Proc.Natl https://www.360docs.net/doc/b0254483.html,A102,

2087–2092(2005).

66.Mackey,D.,Belkhadir,Y.,Alonso,J.M.,Ecker,J.R.&Dangl,J.L.Arabidopsis RIN4

is a target of the type III virulence effector AvrRpt2and modulates RPS2-

mediated resistance.Cell112,379–389(2003).

67.Axtell,M.J.&Staskawicz,B.J.Initiation of RPS2-specified disease resistance in

Arabidopsis is coupled to the AvrRpt2-directed elimination of RIN4.Cell112,

369–377(2003).

68.Day,B.,Dahlbeck,D.&Staskawicz,B.J.NDR1interaction with RIN4mediates the

differential activation of multiple disease resistance pathways.Plant Cell

(September29,doi:10.1105/tpc.106.0446932006).

69.Belkhadir,Y.,Nimchuk,Z.,Hubert,D.A.,Mackey,D.&Dangl,J.L.Arabidopsis

RIN4negatively regulates disease resistance mediated by RPS2and RPM1

downstream or independent of the NDR1signal modulator,and is not required for the virulence functions of bacterial type III effectors AvrRpt2or AvrRpm1.Plant Cell16,2822–2835(2004).

70.Day,B.et al.Molecular basis for the RIN4negative regulation of RPS2disease

resistance.Plant Cell17,1292–1305(2005).

72.Dodds,P.N.et al.Direct protein interaction underlies gene-for-gene specificity

and coevolution of the flax resistance genes and flax rust avirulence genes.Proc.

Natl https://www.360docs.net/doc/b0254483.html,A103,8888–8893(2006).

73.Jia,Y.,McAdams,S.A.,Bryan,G.T.,Hershey,H.P.&Valent,B.Direct interaction

of resistance gene and avirulence gene products confers rice blast resistance.

EMBO J.19,4004–4014(2000).

74.Deslandes,L.et al.Physical interaction between RRS1-R,a protein conferring

resistance to bacterial wilt,and PopP2,a type III effector targeted to the plant nucleus.Proc.Natl https://www.360docs.net/doc/b0254483.html,A100,8024–8029(June3,doi:10.1073/

pnas.12306601002003).

75.Lipka,V.et al.Pre-and postinvasion defenses both contribute to nonhost

resistance in Arabidopsis.Science310,1180–1183,doi:10.1126/science.1119409 (2005).

76.Stein,M.et al.Arabidopsis PEN3/PDR8,an ATP binding cassette transporter,

contributes to nonhost resistance to inappropriate pathogens that enter by direct penetration.Plant Cell18,731–746,doi:10.1105/tpc.105.038372(2006).

77.Yun,B.W.et al.Loss of actin cytoskeletal function and EDS1activity,in

combination,severely compromises non-host resistance in Arabidopsis against wheat powdery mildew.Plant J.34,768–777(2003).

78.Feys,B.J.et al.Arabidopsis SENESCENCE-ASSOCIATED GENE101stabilizes and

signals within an ENHANCED DISEASE SUSCEPTIBILITY1complex in plant innate immunity.Plant Cell17,2601–2613(2005).

79.Collins,N.C.et al.SNARE-protein-mediated disease resistance at the plant cell

wall.Nature425,973–977(2003).

80.Assaad,F.F.et al.The PEN1syntaxin defines a novel cellular compartment upon

fungal attack and is required for the timely assembly of papillae.Mol.Biol.Cell15, 5118–5129(2004).

81.Bhat,R.A.,Miklis,M.,Schmelzer,E.,Schulze-Lefert,P.&Panstruga,R.

Recruitment and interaction dynamics of plant penetration resistance

components in a plasma membrane microdomain.Proc.Natl https://www.360docs.net/doc/b0254483.html,A102, 3135–3140(2005).82.Consonni,C.et al.Conserved requirement for a plant host cell protein in powdery

mildew pathogenesis.Nature Genet.38,716–720(2006).

83.Kobayashi,D.Y.,Tamaki,S.J.&Keen,N.T.Cloned avirulence genes from the

tomato pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv.tomato confer cultivar specificity on soybean.Proc.Natl https://www.360docs.net/doc/b0254483.html,A86,157–161(1989).

84.Lorang,J.M.,Shen,H.,Kobayashi,D.,Cooksey,D.&Keen,N.T.avrA and avrE in

Pseudomonas syringae pv.tomato PT23play a role in virulence on tomato plants.

Mol.Plant Microbe Interact.7,208–215(1994).

85.Peyyala,R.&Farman,M.L.Magnaporthe oryzae isolates causing gray leaf spot of

perennial ryegrass possess a functional copy of the AVR1–CO39avirulence gene.

Mol.Plant Pathol.7,157–165(2006).

86.Staal,J.,Kaliff,M.,Bohman,S.&Dixelius,C.Transgressive segregation reveals

two Arabidopsis TIR-NB-LRR resistance genes effective against Leptosphaeria maculans,causal agent of blackleg disease.Plant J.46,218–230(2006).

87.Rohmer,L.,Guttman,D.S.&Dangl,J.L.Diverse evolutionary mechanisms shape

the type III effector virulence factor repertoire in the plant pathogen Pseudomonas syringae.Genetics167,1341–1360(2004).

88.Tsiamis,G.et al.Cultivar-specific avirulence and virulence functions assigned to

avrPphF in Pseudomonas syringae pv.phaseolicola,the cause of bean halo-blight disease.EMBO J.19,3204–3214(2000).

https://www.360docs.net/doc/b0254483.html,wrence,G.L.,Mayo,G.M.E.&Shepherd,K.W.Interactions between genes

controlling pathogenicity in the flax rust fungus.Phytopathol.71,12–19(1981).

90.Bakker,E.G.,Toomajian,C.,Kreitman,M.&Bergelson,J.A.Genome-wide survey

of R gene polymorphisms in Arabidopsis.Plant Cell181803–1818(2006).

91.Kuang,H.,Woo,S.S.,Meyers,B.C.,Nevo,E.&Michelmore,R.W.Multiple genetic

processes result in heterogeneous rates of evolution within the major cluster disease resistance genes in lettuce.Plant Cell16,2870–2894(2004).

92.Van der Hoorn,R.A.,De Wit,P.J.&Joosten,M.H.Balancing selection favors

guarding resistance proteins.Trends Plant Sci.7,67–71(2002).

93.Thrall,P.H.&Burdon,J.J.Evolution of virulence in a plant host-pathogen

metapopulation.Science299,1735–1737(2003).

94.Tian,D.,Traw,M.B.,Chen,J.Q.,Kreitman,M.&Bergelson,J.Fitness costs of

R-gene-mediated resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana.Nature423,74–77(2003).

95.Kemen,E.et al.Identification of a protein from rust fungi transferred from

haustoria into infected plant cells.Mol.Plant Microbe Interact.18,1130–1139

(2005).

96.Szurek,B.,Marois,E.,Bonas,U.&Van den Ackervecken,G.Eukaryotic features of

the Xanthomonas type III effector AvrBs3:protein domains involved in

transcriptional activationand the interaction with nuclear importin receptors from pepper.Plant J.26,523–534(2001).

97.Holt,B.F.III.et al.An evolutionarily conserved mediator of plant disease

resistance gene function is required for normal Arabidopsis development.Dev.Cell 2,807–817(2002).

98.Palma,K.,Zhang,Y.&Li,X.An importin a homolog,MOS6,plays an important

role in plant innate immunity.Curr.Biol.15,1129–1135(2005).

99.Zhang,Y.&Li,X.A putative nucleoporin96is required for both basal defense and

constitutive resistance responses mediated by suppressor of npr1–1,constitutive1.

Plant Cell17,1306–1316,doi:10.1105/tpc.104.029926(2005).

100.Shao,F.et al.Cleavage of Arabidopsis PBS1by a bacterial type III effector.Science 301,1230–1233(2003).

101.Mucyn,T.S.et al.The NB-ARC-LRR protein Prf interacts with Pto kinase in vivo to regulate specific plant immunity.Plant Cell(October6,doi:10.1105/

tpc.106.0440162006).

102.Abramovitch,R.B.&Martin,G.B.AvrPtoB:a bacterial type III effector that both elicits and suppresses programmed cell death associated with plant immunity.

FEMS Microbiol.Lett.245,1–8(2005).

103.Wu,A.J.,Andriotis,V.M.,Durrant,M.C.&Rathjen,J.P.A patch of surface-exposed residues mediates negative regulation of immune signaling by tomato Pto kinase.Plant Cell16,2809–2821(2004).

104.Rooney,H.C.et al.Cladosporium Avr2inhibits tomato Rcr3protease required for Cf-2-dependent disease resistance.Science308,1783–1786(2005). Acknowledgements We thank S.Grant,D.Hubert,J.McDowell,M.Nishimura, R.Panstruga,J.Rathjen,P.Schulze-Lefert,S.Somerville and C.Zipfel for their critical comments,and our various colleagues for permission to cite their unpublished results.We apologize to the many colleagues whose work could not be discussed owing to strict page limits.Our labs are supported by grants from the NIH,NSF and DOE(JLD)and from the Gatsby Charitable Trust,the BBSRC and the EU(JDGJ).

Author Contributions JDGJ and JLD conceived and wrote the review together. Author Information Reprints and permissions information is available at

https://www.360docs.net/doc/b0254483.html,/reprints.The authors declare no competing financial interests. Correspondence should be addressed to J.J.(jonathan.jones@https://www.360docs.net/doc/b0254483.html,)or J.L.D. (dangl@https://www.360docs.net/doc/b0254483.html,).

NATURE j Vol444j16November2006REVIEWS

329

植物免疫的机制

植物免疫的机制 摘要:植物具有特异与动物的免疫机制,它表现在避病性、抗病性及耐病性三方面,是植物在于病原物对抗并协同进化的过程中获得的。植物在受到病原物入侵后,不亲和植株能通过在入侵部位识别诱导因子,再通过各种信号传递途径引起预存诱导防卫系统及诱导防卫系统的应答,依靠物理性及化学性的防御机制,阻止病原物的入侵,同时整株植株获得诱导性系统抗性。 关键词:植物;免疫机制 Mechanisms of Plants’ immunity Summary: Plants have immune mechanisms which are different from animals, they represent at three ways—preventing, resisting and enduring. These mechanisms are obtained by antagonizing and evolving with pathogens. After invaded by pathogens, antipathic plants can recognize inducing factors in invasive place, response by prestored inducible system and inducible system throught many kinds of signal ways, stop pathogens’ invading by physics and chemistry recovery mechanisms and obtain inductivity systemic fastness at the same time. Key words: plants; immune mechanisms. 在自然环境中,植物与各种病原物的接触无时无处不在,但在大多数情况下,植物却能正常生长发育并繁衍后代,这是因为植物在其长期演化过程中,形成了多种与病原物对抗的途径,获得了免疫性。由于植物营固着生活,不像动物般能通过运动来躲避病原物,也不具有动物般的神经系统及体液循环系统,因此,植物的免疫具有不同于动物的特点。 1.植物免疫性的表现 植物的免疫性表现在避病性、抗病性及耐病性三方面。 1.1.植物的避病性 自然界的各种病原物几乎都有一个最适宜的发生和传播期,这是因为病原物的生长、传播及繁殖对周围的自然环境有一定的要求,如温度、湿度、酸碱度等,使其生长周期与节气相关。比如马铃薯晚疫病的病原菌大量发生和传播的最适条件是低温和高湿,对应我国华北地区就是七、八月份的雨季。同时,植物对某些病害又有一个最易染病期,上述的马铃薯晚疫病的最易染病期就在现蕾之后。不难发现这是由病原物的入侵特性决定的,如病原物特定的入侵途径、特定的入侵部位等,使其入侵与植物的生长周期相关。 如此一来,有的植物就可以通过发展出使其最易染病期避开病原物大量发生和传播期的免疫的机制而免受或少受病原物入侵,即获得了避病性。 植物的避病性的获得相信是生物间协同进化的结果,即由于自然选择的作用,最易染病期与病原物大量发生和传播期相一致的植物因受病原物入侵而灭亡,不能通过繁殖而将其基因传给后代,而最易染病期与病原物大量发生和传播期不一致的植物却得以繁衍,使种群的基因频率发生改变,最终种群获得了避病性。 1.2.植物的抗病性 植物的抗病性是指植物直接抵抗病原物入侵的特性,包括抗侵入、抗寄生及抗再侵染三方面。 1.2.1.抗入侵 抗入侵是指植物在受到病原物通过机械力量或酶类溶解植物表层或植物的伤口的方式入侵时,依靠其表面角质层、蜡质层、木栓层等结构,或者较迅速地愈合伤口,或者在被入

植物免疫反应研究进展

植物免疫反应研究进展 摘要:植物在与病原微生物共同进化过程中形成了复杂的免疫防卫体系。植物的先天免疫系统可大致分为两个层面:PTI和ETI。病原物相关分子模式(PAMPs)诱导的免疫反应PTI 是植物限制病原菌增殖的第一层反应,效益分子(effectors)引发的免疫反应ETI是植物的第二层防卫反应。本文主要对植物与病原物之间的相互作用以及植物的免疫反应作用机制进行了综述,为进一步广泛地研究植物与病原微生物间的相互作用提供了便利条件。 关键词:植物免疫;机制;PTI;ETI 植物在长期进化过程中形成了多种形式的抗性,与动物可通过位移来避免侵染所不同的是,植物几乎不能发生移动,只有通过启动内部免疫系统来克服侵染,植物的先天免疫是适应的结果是同其他生物协同进化的结果。植物模式识别受体(pattern recognition receptors)识别病原物模式分子(pathogen associated molecular patterns, PAMPs), 激活体内信号途径,诱导防卫反应, 限制病原物的入侵, 这种抗性称为病原物模式分子引发的免疫反应(PAMP-triggered immunity, PTI)[1]。为了成功侵染植物,病原微生物进化了效应子(effector)蛋白来抑制病原物模式分子引发的免疫反应。同时,植物进化了R基因来监控、识别效应子, 引起细胞过敏性坏死(hypersensitive response, HR),限制病原物的入侵,这种抗性叫效应分子引发的免疫反应(effector-triggered immunity, ETI)[2]。 1 病原物模式分子引发的免疫反应 1.1植物的PAMPs PAMPs是病原微生物表面存在的一些保守分子。因为这些分子不是病原微生物所特有的,而是广泛存在于微生物中,它们也被称为微生物相关分子模式 (Microbe-associated molecular pattern, MAMPs)。目前在植物中确定的PAMPs有:flg22和elf18,csp15,以及脂多糖,还有在真菌和卵菌中的麦角固醇,几丁质和葡聚糖等。有研究证明在水稻中发现了两个包含LysM结构域的真菌细胞壁激发子,LysM 结构域在原核和真核生物中都存在,与寡聚糖和几丁质的结合有关,在豆科植物中克隆了两个具有LysM结构域的受体蛋白激酶,是致瘤因子(Nod-factor)的受体,在根瘤菌和植物共生中必不可少,这说明PAMPs在其它方面的功能。在这些PAMPs中flg22和elf18的研究比较深入,Felix 等

天然免疫系统细胞

第二章天然免疫系统细胞 学时数:3 目的要求: 1.掌握:免疫系统的组成,主要参与天然免疫应答的免疫细胞的种类、表面标志和受体,以及各类细胞的主要生物学作用。 2.熟悉:上述免疫细胞的来源及发育。 教学内容: 1.免疫系统由免疫组织与器官,免疫细胞和免疫分子组成,主要参与天然免疫应答的免疫细胞包括各类吞噬细胞,NK细胞,肥大细胞,嗜酸性粒细胞和嗜碱性粒细胞。 2.单核吞噬细胞系统的命名,巨噬细胞重要的膜分子及巨噬细胞的免疫学功能、中性粒细胞的膜分子及功能。 3.NK细胞毒细胞的来源和发育,NK细胞受体,NK细胞的主要生物学作用。 4.肥大细胞和嗜碱性粒细胞的分布,受体活化方式及功能。 5.嗜酸性粒细胞,血小板,红细胞及内皮细胞的主要免疫学作用。 第四章天然免疫系统细胞 [本章主要内容] 机体担负免疫功能的物质基础是免疫系统(immune system)。免疫系统由免疫组织与器官、免疫细胞和免疫分子组成。免疫系统可分为天然免疫系统(即非特异性免疫系统)和获得性免疫系统(即特异性免疫系统)。免疫细胞是指参与免疫应答及与免疫应答有关的细胞。主要参与天然免疫应答的免疫细胞包括:吞噬细胞、NK细胞、肥大细胞、嗜碱性粒细胞和嗜酸粒细胞等。 一、吞噬细胞 (一)单核吞噬细胞系统:指血液中的单核细胞(monocyte)和组织中的巨噬细胞(macrophage, MΦ)。巨噬细胞来自于血液中的单核细胞。发育过程:造血干细胞?髓样前体细胞?单核母细胞?前单核细胞?单核细胞(在血液中停留数小时至数天)?巨噬细胞(脾、淋巴结、肝、胸腺、腹腔、皮肤、神经系统及其它结缔组织等)。巨噬细胞在不同组织有不同的命名,如肝脏的Kupffer细胞、脑组织的小胶质细胞、肺脏的尘细胞和骨组织的破骨细胞等。 1.单核-巨噬细胞表面主要膜分子: (1) 介导巨噬细胞吞噬摄取微生物等抗原的受体:清洁受体(scavenger receptor)、LPS 受体(CD14)、甘露糖受体(单核细胞不表达)和补体受体(complement receptor, CR),如FcγRⅢ(CD16)等。 (2) 为巨噬细胞提供活化信号的受体:TLR-4(toll-like receptor-4)和TLR-2等。 (3) 递呈抗原和协同刺激T细胞活化的分子:MHC Ⅱ类分子和B7分子。 另外,单核及巨噬细胞有较强的黏附于塑料或玻璃表面的性质,可利用此特性分离单核细胞和巨噬细胞。 2.主要免疫学功能: (1) 非特异吞噬杀伤作用:吞噬病原微生物和处理清除损伤及衰老的细胞。受刺激活化,产生毒性物质,如过氧化氢(H2O2)、氧离子(O2-)和一氧化氮(NO) 等。 (2) 抗原递呈作用:摄取、处理抗原并递呈给T细胞识别,使T细胞活化,介导特异性免疫应答。 (3) 免疫调节作用:巨噬细胞吞噬抗原活化后,可合成分泌多种细胞因子,如IL-1、IL-6、IL-8、IL-12和TNF-α,参与免疫调节。

植物免疫学

植物免疫学 第一章绪论 Table of Contents 1.1 抗病性利用与植物病害防治 植物病害是作物生产的最大威胁之一 ?1844—1846年,马铃薯晚疫病流行,造成爱尔兰饥荒 ?1870年,咖啡锈病流行,斯里兰卡的咖啡生产全部毁产 ?1942年,水稻胡麻斑病流行,造成孟加拉饥荒 ?1950年,小麦条锈病大流行,我国损失小麦120亿斤 ?1970年、1971年,玉米小斑病流行,美国玉米遭受重大损失 1.1 抗病性利用与植物病害防治 抗病性利用在植物病害防治中的作用 ?利用抗病性来防治植物病害,是人类最早采用的防治植物病害的方法 ?“综合治理”策略中,抗病性利用是最基本、最重要的措施 ?经济、简便、易行,且不污染环境 1.2 植物免疫学 1.2.1 植物免疫学 植物免疫学(plant immunology)是关于植物抗病性原理和应用的综合学科,以植物与病原物的相互作用为主线,探索植物免疫的本质,合理实行人为干预,以达到有效而持久控制植物病害的目的 植物病理学的一门新兴分支学科 系统研究植物的抗病性的类型、机制和遗传、变异规律及植物抗病性合理利用,使其在植物病害防治中发挥应有的作用 1.2 植物免疫学 1.2.2 植物免疫学的研究内容 ①植物抗病性的性质、类型、遗传特点和作用机制 ②植物病原物致病性的性质、类型、遗传特点和作用机制 ③植物与病原物的识别机制和抗病信号的传递途径 ④植物抗病性鉴定技术、抗病种质资源、抗病育种和抗病基因工程 ⑤病原物群体毒性演化规律、监测方法和延长品种抗病性持久度的途径和方法 ⑥人工诱导植物免疫的原理和方法 1.2 植物免疫学 1.2.3 植物免疫学与其它学科的关系 ?以植物病理学、生物化学、遗传学和分子生物学为基础 ?基础理论层面:与植物病原学、植物生理学、真菌生理学、细胞学、生物物理学等学科有密切关系?应用层面:与植物育种学关系最密切,与植物保护学、作物栽培学、植物遗传工程、农业生物技术、田间试验与统计等学科有密切关系 ?在植物病理学各分支学科中,植物免疫学与生理植物病理学、分子植物病理学最接近,内容有所重叠,但学科范畴和侧重点不同 1.3 植物免疫学发展简史 1.19世纪中期至20世纪初期阶段(萌芽阶段) ?1380年,英国选种家J. Clark用马铃薯“早玫瑰”品种与“英国胜利”杂交育成抗晚疫病品种“马德波特?沃皮特” ?L. Liebig,1863发现增施磷肥可提高马铃薯对晚疫病的抗性,偏施氮肥可加重发病 ?1896年,J. Eriksson和E. Hening发现小麦对锈病的反应有严重感染、轻度感染和近乎完全抵抗3种类型,

人体的免疫系统

人体的免疫系统 人体的免疫系统 人体的免疫系统像一支精密的军队,24小时昼夜不停地保护着我们的健康。它是一个了不起的杰作!在任何一秒内,免疫系统都能协调调派不计其数、不同职能的免疫“部队”从事复杂的任务。它不仅时刻保护我们免受外来入侵物的危害,同时也能预防体内细胞突变引发癌症的威胁。如果没有免疫系统的保护,即使是一粒灰尘就足以让人致命。 根据医学研究显示,人体百分之九十以上的疾病与免疫系统失调有关。而人体免疫系统的结构是繁多而复杂的,并不在某一个特定的位置或是器官,相反它是由人体多个器官共同协调运作。骨髓和胸腺是人体主要的淋巴器官,外围的淋巴器官则包括扁桃体、脾、淋巴结、集合淋巴结与盲肠。这些关卡都是用来防堵入侵的毒素及微生物。当我们喉咙发痒或眼睛流泪时,都是我们的免疫系统在努力工作的信号。长久以来,人们因为盲肠和扁桃体没有明显的功能而选择割除它们,但是最近的研究显示盲肠和扁桃体内有大量的淋巴结,这些结构能够协助免疫系统运作。 自从抗生素发明以来,科学界一直致力于药物的发明,期望它能治疗疾病,但事与愿违,研究人员逐渐发现,人们

对化学药物的使用只会刺激免疫系统中的某种成分,但它无法替代免疫系统的功能,并且还会产生对人体健康有害的副作用,扰乱免疫系统平衡。反而是人体本身的防御机制--免疫系统,具有不可思议的力量。而适当的营养却能使免疫系统全面有效地运作,有助于人体更好地防御疾病、克服环境污染及毒素的侵袭。营养与免疫系统之间密不可分、相互促进的关联,成就了营养免疫学创立的理论基础。 综合起来,免疫系统具有以下的功能: 一、保护:使人体免于病毒、细菌、污染物质及疾病的攻击。 二、清除:新陈代谢后的废物及免疫细胞与敌人打仗时遗留下来的病毒死伤尸体,都必须藉由免疫细胞加以清除。 三、修补:人体细胞具有自我修补功能,而免疫系统则为其提供了最好的协助。免疫细胞可以杀死体内的病毒和细菌,同时自身细胞立即修补受损的器官和组织。虽然它的力量令人赞叹,但仍可能因为持续摄取不健康的食物而失效。研究已证实,适当的营养可强化免疫系统的功能,换言之,影响免疫系统强弱的关键,就在于精确平衡的营养,不均衡的营养会使免疫细胞功能减弱,不纯净的营养会使免疫细胞产生失调,导致慢性疾病。营养免疫学的研究焦点就在于如何藉着适当的营养滋养身体,以维持免疫系统的最佳状态,进而使我们的免疫系统更强健,这是由陈昭妃博士撷取中国人对本草植物的使用心得,并融合对于营养免疫学的深入研究所

植物免疫学 精华版

利用抗病性来防治植物病害,是人类最早采用防治植物病害的方法。也是最为经济、安全、有效地防病、控病技术。是当今最受欢迎的防病技术 植物免疫学(plant immunology)是一门专门研究植物抗病性及其应用方法的新兴科学。系统研究病原物的致病性及其遗传规律,植物抗病性的分类、抗病机制、遗传和变异规律、病原物与寄主植物之间相互作用及其应用方法 1905年比芬证明小麦抗条锈病符合孟德尔遗传规律。 1917年,Stakman 发现小麦杆锈菌内有生理小种的分化 Flor 1942 “基因对基因假说(gene-for-gene hypothesis),开启了寄主病菌互作及植物抗病机制的研究。 1992年克隆了第一个植物抗病基因,即玉米的Hm1基因。1993年克隆了首个符合基因对基因关系的R基因番茄的Pto基因 植物抗病性是指植物避免、中止或阻滞病原物侵入与扩展,减轻发病和损失程度的一类特性。 抗病性和植物其他性状一样,都是适应性的一种表现,是进化的产物。 协同进化——在长期的进化中,寄主和病原物相互作用,相互适应,各自不断变异而又相互选择,病原物发展出种种形式和程度的致病性,寄主也发展出种种的抗病性,这就叫协同进化 专性寄生物,不杀死寄主,和平共处,寄主植物产生过敏性坏死反应进行抵抗 被动抗病性,指植物受侵染前就具备的、或说是不论或否与病原物遭遇也必然具备的某些既存现状,当受到侵染即其抗病作用。 主动抗病性,指受侵染前并不出现、或不受侵染不会表现出来的遗传潜能,而当受到侵染的激发后才立即产生一系列保卫反应而表现出的抗病性,又叫这种抗病性为保卫反应。 持久抗病性——某品种在小种易变异的地区,多年大面积种植,该品种抗病性始终未变,则这一抗病性为持久抗病性,或极可能为持久抗病性。 在小种—品种水平上的致病力称为毒性 小种间侵袭力的差异是在对品种有毒力的条件下比较的,小种—品种间无特异性相互关系, 为数量性状。 毒素是病原物分泌的一种在很低浓度下能对植物造成病害的非蛋白类次生代谢物质生理小种是种、变种或专化型内在形态上无差异,但对不同品种的致病力不同的生物型或生物型群所组成的群体。 生物型是生理小种内由遗传一致的个体所组成的群体 毒力频率:一种病原物群体中的对某一个抗病品种有毒力的菌株出现的频率。 突变:病原物的毒性突变是病原物某一菌系在毒性方面对原有菌系突然偏离,即在毒性方面发生飞跃性质的变异 类型: 按产生方式分为自发突变(自然条件下发生的)和诱导突变(人工用物理、化学等因素诱发的); 按产生机制分为基因突变(又称点突变,是病原真菌细菌DNA或病毒RNA分子上基因范围内分子结构的改变,1对或少数几对碱基发生变异)和染色体畸变(染色体畸变是指染色体的某一区段发生缺失、倒位、重复和易位)。 按变异方向分为正向突变和回复突变 准性生殖指一些营养体为菌丝体的单倍性子囊菌如一些霉菌可以不经过减数分裂,在菌丝体细胞内进行细胞核的融合、染色体的交换和重组,进而产生后代的过程

植物先天免疫系统

植物先天免疫系统 植物先天免疫系统是植物古老的防御系统,正是由于这一系统的存在使得能够侵染植物的病原物只是微生物中很小的一部分,大部分的有害生物则被拒之门外。“免疫”的概念最初来源于动物学家对脊椎动物的研究,后来植物学家发现植物也和脊椎动物一样存在一套类似免疫系统。脊椎动物形成了一套复杂的适应性或获得性免疫体系,涉及对特定病原体的识别和抗体及针对特定抗原的细胞毒性T-细胞。身体的第一道防线,即我们生来就有的防线,是先天免疫功能。这种功能取决于身体中先天已经编好程序的、由树状细胞、巨噬细胞、自然杀手细胞和抗菌肽等对微生物的识别。植物由于没有哺乳动物的移动防卫细胞和适应性免疫反应,因此依靠每个细胞的先天免疫力以及从感染点在植物内各处发送的信号来进行免疫。植物先天免疫系统是病原菌入侵突破了植物第一道防线(植物体的机械障碍)之后的防御系统。 Jones 和 Dangl(2006)依据当前植物先天免疫系统研究进展提出了一个四阶段的拉链模式(a four phased ‘zigzag’ model),为认识植物先天免疫系统提供了新的认识。Bent和Mackey(2007)对这个新的四阶段模式进行了更详细的注解(图1)。这个新的模式甚至被大家誉为植物病理学新的“中心法则”,这个重要的模式阐述了植物和病原物相互作用的进化过程。这个模式中病原物与植物的互作分为四个阶段:第一个阶段,植物模式识别受体(pattern recognition receptor, PRRs)识别微生物保守的PAMPs,激活PAMPs分子引发的植物免疫反应(PAMP-triggered immunity, PTI)使得大多数的病原物不能致病;第二个阶段,某些进化的病原物分泌出一些毒性因子,这些毒性因子抑制PTI导致植物产生效应因子激活的感病性(effector-triggered susceptibility, ETS);第三个阶段,植物进化出专一的R基因直接或间接识别病原物特异拥有的效应因子,产生效应因子激活的免疫反应 (effector-triggered immunity, ETI),ETI加速和放大PTI使植物产生抗病性;第四个阶段,在自然选择的压力下迫使病原物产生新的效应因子或者增加新的额外的效应因子来抑制ETI,而植物在自然选择的压力下产生新的R基因以激活ETI维持自己的生存。在这个模式中我们可以看到R基因在植物抗病中起着重要的作用,而病原相关分子模式引发的基础免疫反应将许多潜在的病原物拒之门外。 (1 )病原相关分子模式引发的先天免疫反应 病原相关分子模式引发的先天免疫反应是植物“自己”与“非己”识别,对入侵物的识别是免疫防御的起始,最终引发防御反应系统。这种“非己”识别是植物细胞膜表面存在的某些特异的、可溶的或与细胞膜结合的模式识别受体对微生物的表面物质的识别,这些物质称为微生物/病原相关分子模式。 (2) 病原物的病原相关分子模式 PAMPs是一类寄主中不存在的,进化上保守的,对于病原物的生存来说有重要功能的分子(Gómez-Gómez and Boller, 2002; Nürnberger and Brunner, 2002)。在动物中PAMPs主要包括病原菌表面的蛋白质,核酸及碳水化合物(carbohydrates):脂多糖(lipopolysaccharide),肽聚糖识别蛋白(peptidoglycan),脂磷壁酸(lipoteichoic acids)等。各种病原体相关分子模式加起来超过1000种(Mackey and McFall,2006)。 以产生氧爆破(oxidative burst)、乙烯增加和对病原菌的抗性(Kunze et al., 2004)。由于植

免疫调节免疫调节知识点总结详细

免疫调节核心知识点列表梳理 1.与免疫有关的细胞 2.两种免疫类型比较 5.特异性免疫的类型及其应用 3.体液免疫与细胞免疫之间的区别

4.过敏反应产生的抗体与正常免疫反应产生的抗体比较 6.免疫失调与人体健康 免疫调节知识点

第一道防线:皮肤、粘膜等(痰,烧伤) 非特异性免疫(先天免疫) 第二道防线:体液中杀菌物质(溶菌酶)、吞噬细胞 (伤口化脓) 1、免疫 特异性免疫(获得性免疫)第三道防线:体液免疫和细胞免疫 (最主要的免疫方式) 在特异性免疫中发挥免疫作用的主要是淋巴细胞(T 淋巴细胞和B 淋巴细胞) 2、免疫系统的功能:防卫功能、监控和清除功能(癌症问题)。 来源:能够引起机体产生特异性免疫反应的物质, 主要是外来物质(如: 细菌、病毒、),其次也有自身的物质(人体中坏死、变异的细胞、组织癌细胞,),还有(移殖器官)。 ① 抗原 (抗原决定簇) 本质:蛋白质或糖蛋白 特性:异物性(外来物质),大分子性(相对分子质量很大),特异性(只 与相应的抗体或效应T 细胞发生特异性结合) 。(特异性) ②抗体: 抗体与抗原结合产生细胞集团或沉淀,从而抑制抗原的繁殖或对人体细胞的 黏附(并不能直接杀死抗原)最后被吞噬细胞吞噬消化。 ③淋巴细胞的产生过程: B 浆细胞 抗体 骨髓造血干细胞 胸腺 T T 细胞 与靶细胞结合 淋巴因子(干扰素 白细胞介素) 功能1)增强淋巴因子的杀伤力 2)能够诱导产生更多的淋巴因子(白细胞介素-2) 3、 体液免疫过程:(抗原没有进入细胞) 记忆B 细胞的作用:可以在抗原消失很长一段时间内保持对这种抗原的记忆,当再接触这种抗原时,能迅速增殖和分化,产生浆细胞从而产生抗体。(有的记忆细胞可以保留一辈子,如天花病毒,有的则很短,如流感病毒) 4、体液免疫 抗原 吞 噬 细 胞 (处理) (呈递) T 细胞 细胞 (识别) B 细胞 B 细胞 形成沉淀 感应阶段 反应阶段 效应阶段 (二次免疫)

植物免疫学

名词 1.生理小种:是病原菌种、变种或专化型内形态特征相同,但生理特性不同的类群,可以通过对寄主品种的致病性,即毒性的差异区分开来。 2.变种:除了寄生专化性差异外形态特征和生理性状也有所不同。 3.专化型:并无形态差异,但对寄主植物的属和种的专化性不同。 4.致病变种:细菌在种下设置致病变种,系以寄主范围和致病性来划分的组群,相当于真菌的专化型。 5.毒素:是植物病原真菌和细菌在代谢过程中产生的小分子非酶类化合物,亦称微生物毒素,能在非常低的浓度范围内干扰植物正常的生理功能,诱发植物产生与微生物侵染相似的症状。 6.定性抗病性:抗病性若用定性指标来衡量和表示,则称为定性抗病性,亦称为质量抗病性。 7.定量抗病性:用定量指标来表示的抗病性称为定量抗病性,亦称数量抗病性。衡量抗病性的定量指标种类很多,如发病率、严重度、病情指数等。 8.病害反应型:即是一种定性指标,它反映了寄主和病原物相互斗争的性质。 9.主动抗病性:诱导性状所确定的抗病性为主动抗病性,是病原物侵染所诱导的。最典型的为过敏性坏死坏死反应。 10.防卫反应:植物主动抗病性反应也称为防卫反应,防卫反应的发生反应了侵染诱导的植物代谢过程的改变。 11.过敏性反应:又称过敏性坏死反应,简称HR反应,指植物对不亲和性病原物侵染表现高度敏感的现象。发生此反应时,侵染点细胞及其邻近细胞迅速死亡,病原物受到遏制。 12.主效基因抗病性:由单个或少数几个主效基因控制被称为单基因抗病性或寡基因抗病性,统称为主效基因抗病性。 13.微效基因抗病性:由多数基因控制,各个基因单独作用微小,这称为多基因抗病性或微效基因抗病性。 14.幽灵效应:被病原菌克服的主效基因对定量抗病性有所贡献,但并不能用以完全说明定量抗病性,主效基因抗病性这种作用被称为残余效应或幽灵效应。15.小种专化抗病性:农作物品种的抗病性可能仅仅对某个或某几个小种有效,而不能抵抗其他小种,这种抗病性类型是小种专化性抗病性。 16.小种非专化抗病性:不具有小种专化性抗病性的则称为小种非专化抗病性,常作为品种的背景抗病性而存在,也被称为一般抗病性。 17.持久抗病性:若某一品种在适于发病的环境中长期而广泛的种植后仍能保持其抗病性,则它所具有的这种抗病性就是持久抗病性。 18.诱导抗病性:又称获得抗病性,是指植物经病原物接种,或经生物因子、化学物质或物理因子处理所激发的,针对病原物再侵染的抗病性。 19.系统获得抗病性:是指过敏性局部侵染所诱导的系统抗病性。 20.诱导系统抗病性:指由植物根围生防菌所诱导的系统抗病性。 21.病原物衍生抗病性:由病原物提供的基因在植物中表达的抗病性,称为病原物衍生抗病性。 22.激发子:激发诱导抗病性的各种因子统称为诱导因素也称激发子。有生物因素,非生物因素,也有外源的和内源的。 23.木质化作用:木质化作用是在细胞壁、胞间层和细胞质等不同部位产生和积

免疫系统的组成和功能

免疫系统的组成和功能 人体内有一个免疫系统,它是人体抵御病原菌侵犯最重要的保卫系统。这个系统由免疫器官(骨髓、胸腺、脾脏、淋巴结、扁桃体、小肠集合淋巴结、阑尾等)、免疫细胞(淋巴细胞、单核吞噬细胞、中性粒细胞、嗜碱粒细胞、嗜酸粒细胞、肥大细胞、血小板等),以及免疫分子(补体、免疫球蛋白、细胞因子等)组成。 免疫系统是机体防卫病原体入侵最有效的武器,它能发现并清除异物、外来病原微生物等引起内环境波动的因素。但其功能的亢进会对自身器官或组织产生伤害。在很多由于自身免疫引起的疾病中,CD4+ T细胞起着重要的作用。免疫系统分为固有免疫和适应免疫,其中适应免疫又分为体液免疫和细胞免疫。 在感染过程中,各免疫器官、组织、细胞和分子间互相协作、互相制约、密切配合,共同完成复杂的免疫防御功能。病原体侵入人体后,首先遇到的是天然免疫功能的抵御。一般经7-10天,产生了获得性免疫;然后两者配合,共同杀灭病原体。免疫系统具有以下的功能:(高中生物疑问,关注101答疑网…) 保护 使人体免于病毒、细菌、污染物质及疾病的攻击。 清除 新陈代谢后的废物及免疫细胞与敌人打仗时遗留下来的病毒死伤尸体,都必须藉由免疫细胞加以清除。 修补 免疫细胞能修补受损的器官和组织,使其恢复原来的功能。健康的免疫系统是无可取代的,虽然它的力量令人赞叹,但仍可能因为持续摄取不健康的食物而失效。研究已证实,适当的营养可强化免疫系统的功能,换言之,影响免疫系统强弱的关键,就在于精确平衡的营养,不均衡的营养会使免疫细胞功能减弱,不纯净的营养会使免疫细胞产生失调,导致慢性疾病。营养免疫学的研究焦点就在于如何藉着适当的营养滋养身体,以维持免疫系统的最佳状态,进而使我们的免疫系统更强健。 免疫系统的功能为您介绍这些,人体免疫系统是人的一道自然屏障,可以与疾病斗争。

第二章免疫系统

第二章免疫系统 免疫系统(immunesystem)是动物机体执行免疫功能的机构。 由三大部分组成:免疫器官、免疫细胞、免疫相关分子(抗体、补体、细胞因子) 第一节免疫器官 和其他免疫细胞发生、分化、成熟、定居和增殖以及产生免疫应答的场所。 根据功能的不同,免疫器官可分为: 中枢免疫器官(centralimmuneorgan)、外周免疫器官(peripheralimmuneorgan) 一、中枢免疫器官 又称初级免疫器官(primaryimmuneorgan),是淋巴细胞等免疫细胞发生、分化和成熟的场所,包括骨髓、胸腺、法氏囊 共同特点: 1.在胚胎发育的早期出现; 2.具有诱导淋巴细胞增殖分化为免疫活性细胞的功能,也是淋巴干细胞增殖分 化为免疫活性细胞的场所; 3.如果在新生期切除这类器官,可造成淋巴细胞因不能正常的发育分化而机体 缺乏具有功能的淋巴细胞,出现免疫缺陷、免疫功能低下甚至丧失。 (一)骨髓 是各种血细胞和 功能:1.是机体最重要的造血器官,出生后所有的血细胞来自于骨髓多能干细胞; 2.是重要的免疫器官,是各种免疫细胞发生和分化的场所。 3.对于人和哺乳动物而言,骨髓也是参与体液免疫的重要器官,是发生再次体液免疫应答的主要部位。 (二)胸腺 是T淋巴细胞发育成熟的场所。 不同动物的胸腺其大小、形态、数量、存在位置不同: 大多位于胸腔前纵隔中,分左右两叶,猪、马、牛、犬、鼠等可延伸至颈部直达甲状腺; 鸡的胸腺为左右两侧每侧6—7个球状物,呈念珠状,位于两侧颈沟中; 鸭、鹅的胸腺为颈部两侧各5个叶。 胸腺退化的情况 1、生理性退化(ageinvolution) 又称年龄性退化 胸腺的大小因年龄不同而差异很大,就其与体重的相对大小而言,在初生时最大, D.毒性药物 E.应激反应 F.其它因素:肿瘤,器官移植

植物免疫诱抗蛋白的生理生化机制与植物免疫的机制

植物免疫诱抗蛋白的生理生化机制与植物免疫的机制 在自然环境中,植物与各种病原物的接触无时无处不在,但在大多数情况下,植物却能正常生长发育并繁衍后代,这是因为植物在其长期演化过程中,形成了多种与病原物对抗的途径,获得了免疫性。由于植物营固着生活,不像动物般能通过运动来躲避病原物,也不具有动物般的神经系统及体液循环系统,因此,植物的免疫具有不同于动物的特点。 植物免疫诱抗蛋白的生理生化机制 1、什么是植物免疫诱抗蛋白? 植物免疫诱抗蛋白是以色列著名农业生物科研机构——“Galilee-Green(嘉利利-绿色)实验室”最新科研成果,它基于细胞信号转导途径,可直接与植物细胞壁的果胶化合物结合,引起Cl、Ca、K、H、Cu、Zn离子通道和多种酶的激活,这些因子在植物抗病信号通路中起着重要的作用。在对植物进行处理后,可以诱导激发植物对多种病害的主动抵御,具有显著的增强植物抗性功能。植物免疫诱抗蛋白还可以诱导植物抗虫,促进植物生长发育,具有明显的增产和改善品质效果。在以色列“Galilee-Green(嘉利利-绿色)实验室”过去近6年的田间试验中证明,植物免疫诱抗蛋白可以诱导90多种作物对70余种病害及20多种虫害的抗性,对病虫害的防治效果为40%~80%,并且可以使作物增产10-75%。 2、植物免疫诱抗蛋白的生理生化机制 植物受病原物侵染时,侵染部位“氧化激增”,局部细胞主动程序化死亡,产生过敏反应,继而引起一系列的防卫性变化,产生对病原菌侵染的系统获得抗性。植物免疫诱抗蛋白诱导产生的抗病信号由内源信号分子SA、JA、Et和NO完成,经过一系列的基囚表达,植物体内会产生大量的酶催化活动,产生一系列相应生理生化指标的防卫化反应,催化一些诱导型抗病物质的合成,这些相关的抗病物质主要有植物保卫素、酚类、木质素、HRGP等。植物对病原物侵入的生理生化反应是通过酶催化活动实现的,与植物抗病相关的酶主要有苯丙氨酸解氨酶、B—l,3一葡聚糖酶、4一香豆酸辅酶A联结酶、多酚氧化酶、几丁质酶、过氧化物酶、过氧化氢酶、抗坏血酸过氧化物酶、超氧化物歧化酶和一氧化氮合成酶

植物免疫学 简答题

1,植物的抗病性类别有哪些? 1)寄主抗病性和非寄主抗病性 2)基因抗病性和生理抗病性 3)避病、耐病、抗病、抗再侵染 4)被动抗病性和主动抗病性 5)主效基因抗病性和微效基因抗病性 6)垂直抗病性和水平抗病性 2,侵染力的指标有哪几个 1)孢子萌发速度 2)定植速度 3)产孢速度 3,病原物侵袭手段有哪些?举例说明 1)机械伤害大麦网斑病、葡萄黑痘病 2)酶解 3)毒素黄曲霉毒素 4,毒素的作用机理是什么? 1)对细胞膜的破坏 2)对线粒体的破坏 3)对叶绿体的破坏 4)影响DNA表达 5,致病毒素可分为哪几种? 1)选择性毒素 hv、hs、hmt 2)非选择性毒素黑斑毒素 6,生长调节性物质有哪几种?作用各是什么? 1)生长素低浓度促进植物生根、发芽,高浓度抑制 2)赤霉素保花保果、打破休眠、治疗病害 3)细胞分裂素促进细胞分裂,组织培养,促进器官形成 4)乙烯抑制生长,促进果实成熟。去雄催熟保花提高作物品质 7,植物病原菌生理小种鉴定的原理及程序是什么? 原理:根据供试菌系在寄主上的感抗反应来鉴别小众的类型 1)病叶采集 2)菌种繁殖 3)接种鉴别寄主 4)发病调查记载 5)小种和新小种的确定 8,柯赫氏法则包括什么内容? 1)这种微生物的的发生往往与某种病害有联系,发生这种病害往往就有这种微生物存 在 2)从病组织上可以分离得到这种微生物的纯培养并且可以在各种培养基上研究它的 性状 3)将培养的菌种接种到健全的寄主上能又发出与原来相同的病害 4)从接种后发病的寄主上能再分离培养得到相同的微生物 9,症状的类型? 1)典型症状

2)综合症 3)并发症 4)隐症现象 10,病害发生后光合作用的变化? 1)光合速率,降低 2)叶绿体功能,数量减少、形态和大小改变、片层损伤、体膜跑囊化、叶绿体核糖体 含量下降。 3)光化学反应,活性降低 4)二氧化碳吸收量,降低 5)光合碳同化,速率降低 6)光合产物积累及运输,受阻 11,病害发生后核酸和蛋白质的变化? 核酸: 1)病原真菌:侵染前期,叶肉组织内RNA含量增加,侵染中后期,RNA含量下降。 DNA含量变化较小 2)病毒TMV:病毒侵染后,由于病毒基因组的复制,寄主体内病毒RNA增多,寄主 RNA 合成受到抑制 3)细菌:在冠瘿土壤杆菌侵染引起的肿瘤组织中RNA含量显著增多 蛋白质: 1)病原真菌:受侵染早期,病株总氮量和蛋白质含量增高;侵染中后期,蛋白质水解 酶增多,蛋白质含量下降,总氮量上升,但游离的氨基酸增多 2)病毒:被病毒侵染后常导致寄主蛋白的变相合成,以满足病毒外壳蛋白大量合成的 需要 3)细菌:受侵染后,抗病寄主和感病寄主中蛋白质的合成能力有明显冲突 12,病害发生后水分生理的变化有哪些? 1)病株出现缺水症状 2)病株叶片蒸腾作用的变化:提高或降低 3)病株体内水分运输的变化:根系吸水能力降低和导流液上升受阻 13,抗病鉴定的基本要求是什么? 1)目标明确 2)结果正确 3)全面衡量 4)经济快速 5)实行标准化 6)实行联合鉴定 14,田间抗病鉴定的优点有哪些? 1)能在群体和个体两个层次认识抗病性 2)可揭示植株各发育阶段的抗病性水平变化 3)能较全面的发映出抗病类型和水平 4)鉴定结果能代表品种在实际生产中的实际表现 15,保护植物抗病性的策略有哪些? 1)利用遗传多样性来控制病菌的变异 2)综合利用主效基因抗病性和微效基因抗病性 3)应用栽培措施提高植物抗病性

昆虫天然免疫的研究进展

昆虫天然免疫的研究进展 摘要:昆虫是目前地球陆地上最繁盛的物种类群,是人类取之不尽的资源宝库。近年来,昆虫的免疫在其基础和应用研究方面受到极大关注,通过实验来研究与昆虫免疫相关的机制、信号等问题,对害虫防治、益虫防病、开发利用抗菌物、研究人类免疫机制等有着非常重要的现实意义。 关键词: 昆虫;天然免疫;体液免疫;细胞免疫 Abstract:At present, insect is the most blooming species on the earth. And it is also a treasure-house of kinds of resources for humanity. For the past few years, the fundamental researches and application researches of insect immunity have been paid close attention to. Many scientific researchers study the mechanism and signal that related to insect’s immunity by doing experiments. It is of significance for pest control, preventing disease of beneficial insect, developing and using antibacterial material, studying humanity immunity and so on. Key words: Insect;Innate immunity;Humeral immunity;Cellular immunity 昆虫作为生物界分布最广、数量众多的一类群体, 在长期的进化过程中具备了高度的适应能力和独特的免疫体系。虽然昆虫没有像人一样的获得性免疫反应能力,但是昆虫拥有高效的先天性免疫反应系统。昆虫的先天性免疫系统包括体液免疫和细胞免疫两部分, 它们协同作用吞噬和清除血淋巴中的外源入侵物。[冯从经,陆剑锋,黄建华,等,2009]本文主要基于目前对昆虫天然免疫的研究进展做一简介。 1.体液免疫 1.1抗菌肽 抗菌肽(AMPs),具有广谱抗菌活性和高效杀菌性,一直以来都承载着人类的一个梦想——取代抗生素。人类已经发现多种抗菌肽,测定出其结构,并获得抗菌肽基因,如Mdatta2基因[柳峰松,孙玲玲,唐婷,等,2011]、MdDpt基因[柳峰松,王丽娜,唐婷,等,2009]。根据氨基酸组成和结构特征, 一般可以把昆虫抗细菌肽分为 4类:即形成两性分子α-螺旋的抗细菌肽类、有分子内二硫桥的抗细菌肽类、富含脯氨酸的抗细菌肽类及富含甘氨酸的抗细菌多肽类。[柳峰松,王丽娜,唐婷,李伟,2009]昆虫抗菌肽中除绝大多数对细菌具有广谱高效的抑杀作用外, 近 10 年来也陆续发现了10多种抗真菌肽。昆虫抗真菌肽可分成两类: 昆虫组成性抗真菌肽、经免疫诱导在血淋巴中产生的抗真菌肽, 即昆虫免疫诱导型抗真菌肽[谢咸升,董建臻,李静,等,2011]。 AMPs 的产生主要由以下两个不同信号转导途径的活化而产生的: Toll途径和Imd途径,这两种途径通过激活不同的转录因子来调控不同AMPs 的基因表达。[王英,黄复生,2008]昆虫抗菌肽既具有种的差异性,又具有一定的同源性,抗菌物质在昆虫中普遍存在,可能是昆虫—植物—病原菌长期协同进化在免疫学上的体现,可以作为抗性资源利用[谢咸升,李静,董建臻,等,2009]。但是目前对抗菌肽作用机制仍需进一步研究,面对病原菌抗药性的升级, 抗菌肽及其基

植物多糖及免疫调节作用

植物多糖及免疫调节作用 1 植物多糖免疫活性概述 植物多糖免疫活性研究是植物多糖药理研究的热点,到目前为止已发现200余种植物多糖具有免疫活性。植物多糖对免疫系统的调节作用,主要表现为免疫增强或免疫刺激。它能够激活巨噬细胞、自然杀伤细胞等固有性免疫细胞,促进T淋巴细胞、B淋巴细胞的增殖、抗体的生成,促进细胞因子的分泌。更多研究显示,多糖还对细胞黏附分子等也有一定影响。此外,多糖具有免疫原性,可用来构建新的疫苗,具有广阔的发展前景和社会经济效益。 2 植物多糖对非特异性免疫的影响 非特异性免疫是生物体在长期种系进化过程中形成的一系列防御机制。固有免疫在个体出生时就具备,产生非特异性抗感染免疫作用。主要包括吞噬细胞,自然杀伤细胞(NK),树突状细胞(DC)等。 2.1 植物多糖对巨噬细胞的影响 巨噬细胞分定居的巨噬细胞和游走的巨噬细胞两类。游走巨噬细胞由血液中单核细胞衍生而来。它具有强大的吞噬杀菌和吞噬清除体内凋亡细胞及其他异物的能力,并能分泌多种细胞因子等,参与炎症反应等作用。寇小红等用小鼠巨噬细胞系Raw264.7检测绿茶多糖免疫活性,发现对小鼠巨噬细胞Raw264.7有显著活性,能促进小鼠巨噬细胞生成NO的活性,在浓度达到100 μg/ml左右时的促进活性效果最强[1]。郑尧等观察到口服或注射甘草多糖后,能显著提高小鼠网状内皮系统中的单核巨噬细胞吞噬功能[2]。王学梅等研究芦荟多糖对鸡免疫功能的影响,发现添加芦荟多糖的实验组,吞噬指数均高于对照组,并且随着饲粮芦荟多糖浓度的增加,吞噬指数也增大[3]。 2.2 植物多糖对NK细胞的影响 NK细胞在机体抗肿瘤和早期抗病毒和胞内寄生菌感染的免疫过程中起重要作用。严全能等在观察羊栖菜多糖对小鼠免疫功能的调节作用的实验中,发现羊栖菜多糖提高小鼠NK细胞杀伤活性[4]。王剑等通过体外细胞毒性检测、小鼠脾淋巴细胞增殖实验、NK细胞活性测定等实验,对川牛膝多糖的免疫活性进行了研究,研究结果表明,川牛膝多糖体外在10~300 μg/mL浓度范围内能够增

植物免疫学考试

一.名词解释: 1.抗病性(resistance)—是指植物避免、中止或阻滞病原物侵入与扩展,减轻发病和损失程度的 一类特性。抗病性是指寄主植物抵抗或抑制病原物侵染的能力。不同植物对病原物抗病能力的表现有差异。 2.避病性(avoidance):植物因不能接触病原物或接触的机会减少而不发病或发病减少的现象。 植物可能因时间错开或空间隔离而躲避或减少了与病原物的接触,前者称为“时间避病”,后者称为“空间避病”。 3.病情指数(disease index):是全面考虑发病率与严重度两者的综合指标。 4.毒素(toxin):是植物病原真菌和细菌代谢过程中产生的,能在非常低的浓度范围内干扰植物 正常生理功能,对植物有毒害的非酶类化合物。 5.抗病性(resistance to disease):是指植物避免、中止或阻滞病原物侵入与扩展,减轻发病 和损失程度的一类特性。 6.耐病性(tolerance):一些寄主植物在受到病原物浸染以后,虽然表现明显的病害症状,甚至 相当严重,但仍然可以获得较高的产量。有人称此为抗损害性或耐害性。 7.真菌(fungus):是具有细胞核、能产孢而无叶绿素的生物。它们一般都能进行有性或(和) 无性繁殖,并常有分枝的丝状营养体,典型的具有几丁质或纤维素的细胞壁。 8.植物保卫素(phytoalexin):是植物受到病原物侵染后或受到多种生理的、物理的刺激后所产 生或积累的一类低分子量抗菌性次生代谢产物。也称为植物抗毒素,它是由植物——病原物相互作用或者作为伤害和其他生理刺激而产生的一种抗生素。泛指对病原物有杀伤作用从而减轻对植物的侵染和致病能力的非酶类小分子化合物。植物保卫素(phytoalexin)是植物受到病原物侵染后或受到多种生理的、物理的刺激后所产生或积累的一类低分子量抗菌性次生代谢产物。 植物保卫素对真菌的毒性较强. 9.准性生殖(parasexuality):指异核体真菌菌丝细胞中两个遗传物质不同的细胞核可以结合成 杂合二倍体的细胞核,这种二倍体细胞核在有丝分裂过程中可以发生染色体交换和单倍体化,最后形成遗传物质重组的单倍体的过程。 10.转导——是指供体细菌的遗传物质通过噬菌体转移给受体细菌,导致受体细菌基因改变的现 象。 11.转主寄生:真菌必须在两种不同的寄主植物上寄生生活才能完成其生活史的,称为转主寄生。这两种寄生植物均称为转主寄生。 12.有性生殖和准性生殖:有性生殖是真菌经过两性结合或性器官的结合而进行繁殖的方式,一般经过质配、核配和减数分裂。准性生殖是真菌不经过两性结合和减数分裂而通过异核二倍体的有丝分裂和单倍体化实现染色体的交换与重组的特殊繁殖方式,一般经过质配、核配和单倍体化或不均等分裂。 11.内含体:指植物感染病毒后,有些产物会与病毒的核酸、寄主的蛋白等物质聚集起来,形成的 具有一定形状的复合体。 12.基因对基因学说:由Flor(1956)提出的一个学说,对应于寄主方面的每一个决定抗病性的基 因,病菌方面也存在一个致病性的基因。寄主-病原物体系中,任何一方的每个基因,都只有在另一方相对应的基因作用下才能鉴定出来。