Diversity and host specificity of endophytic Rhizoctonia-like fungi from tropical orchids

American Journal of Botany89(11):1852–1858.2002.

D IVERSITY AND HOST SPECIFICITY OF ENDOPHYTIC

R HIZOCTONIA-LIKE FUNGI FROM TROPICAL ORCHIDS1

J.T UPAC O TERO,2J AMES D.A CKERMAN,AND P AUL B AYMAN

Department of Biology,University of Puerto Rico,R?′o Piedras,P.O.Box23360,San Juan,Puerto Rico00931-3360USA All orchids have an obligate relationship with mycorrhizal symbionts.Most orchid mycorrhizal fungi are classi?ed in the form-genus Rhizoctonia.This group includes anamorphs of Tulasnella,Ceratobasidium,and Thanatephorus.Rhizoctonia can be classi?ed according to the number of nuclei in young cells(multi-,bi-,and uninucleate).From nine Puerto Rican orchids we isolated108 Rhizoctonia-like fungi.Our isolates were either bi-or uninucleate,the?rst report of uninucleate Rhizoctonia-like fungi as orchid endophytes.We sequenced the internal transcribed spacer(ITS)region of nuclear ribosomal DNA from26isolates and identi?ed four fungal lineages,all related to Ceratobasidium spp.from temperate regions.Most orchid species hosted more than one lineage,dem-onstrating considerable variation in mycorrhizal associations even among related orchid species.The uninucleate condition was not a good phylogenetic character in mycorrhizal fungi from Puerto Rico.All four lineages were represented by fungi from Tolumnia variegata,but only one lineage included fungi from Ionopsis utricularioides.Tropical epiphytic orchids appear to vary in degree of speci?city in their mycorrhizal interactions more than previously thought.

Key words:Ceratobasidium;orchid mycorrhizae;Puerto Rico;Rhizoctonia;speci?city.

All orchids have an obligate relationship with mycorrhizal symbionts during seed germination,with most of the symbi-onts being Rhizoctonia-like fungi(Arditti,1992).Understand-ing the mycorrhizal symbiosis is of great importance,as avail-ability of the fungal symbionts may play a key role in deter-mining orchid distribution and diversity.Furthermore,most studies of orchid mycorrhizal interactions have concentrated on terrestrial orchids from temperate regions,whereas the ma-jority of orchid species are epiphytes in tropical regions. Studies to date regarding the speci?city of orchid mycor-rhizal relationships have drawn con?icting conclusions.Two distinct approaches have been taken in the investigation of speci?city of orchid mycorrhizal relationships:(1)in vitro seed germination experiments and(2)taxonomic comparisons of fungi present in orchid roots of mature plants.One germina-tion study of epiphytic orchids suggesting speci?city(Cle-ments,1987)is balanced by another that suggests more gen-eralist interactions(Zettler,Burkhead,and Marshall,1999). Answering the question of speci?city depends on a thorough sampling and detailed taxonomy of orchid mycorrhizal fungi. The systematics of orchid mycorrhizal fungi has been stud-ied using both morphological(Warcup and Talbot,1966,1971; Currah,Hambleton,and Smreciu,1988;Rasmussen,1995), and molecular characters(Taylor and Bruns,1997,1999;Kris-tiansen et al.,2001).Rhizoctonia-like fungi include the ana-morphic(asexual)genera Ceratorhiza,Epulorhiza,Moniliop-sis,and Rhizoctonia(Moore,1988)of a variety of teleomorphs (sexual stages of Ceratobasidium,Thanatephorus,Tulasnella, and Sebacina;Warcup and Talbot,1966,1971).Some of these are well known as plant pathogens of a wide variety of crops

1Manuscript received5February2002;revision accepted16May2002. The authors thank P.Pabo′n,A.Carrillo,J.Garc?′a,and L.Fidalgo for as-sistance in the laboratory,J.E.Garc?′a-Arrara′s for use of facilities,N.S. Flanagan for support and comments on the manuscript,and A.Alegr?′a,P. Silverstone-Sopkin,and L.G.Naranjo of Universidad del Valle,Cali,Colom-bia for their inspiration.This research was supported from a grant from the Organization for Tropical Studies and a NSF-EPSCoR scholarship(EPS-9874782)to J.T.Otero and funds from NASA-IRA and NIH-RCMI to U.P.R. DNA sequencing was made possible by grant NSF DEB-9806792to W.O. McMillan.

2Author for reprint requests(e-mail:is975785@https://www.360docs.net/doc/f411659077.html,).(Sneh,Burpee,and Ogoshi,1991).Rhizoctonia are character-ized by right-angle branching,a constriction at the branch point,and a septum in the branch hypha near its point of origin.Frequently,they have chains of in?ated hyphae,known as monilioid cells(Sneh,Burpee,and Ogoshi,1991).Sexual stages are rarely encountered in the?eld or laboratory.Con-sequently,the broad vegetative criteria for identi?cation have resulted in paraphyletic taxonomy,with various unrelated fun-gi being grouped together.

One morphological feature that has helped in the classi?-cation of Rhizoctonia is the number of nuclei present in the young cells(Sneh,Burpee,and Ogoshi,1991).Multi-,bi-and uninucleate cells have been observed.The important plant pathogen species complex Rhizoctonia solani(teleomorphs: Thanatephorus,Ceratobasidiales)possesses multinucleate cells.Binucleate cells have been seen in fungi corresponding to the genus Ceratobasidium(Ceratobasidiales)and Tulasnella (Tulasnellales).Uninucleate strains occur in anamorphs of Ceratobasidium(Hietala,Vahala,and Hantula,2001),but have rarely been reported(Hietala,1997).

An additional way to classify these fungi is by anastomosis groups(AG).When two isolates belong to the same AG,their hyphae are able to fuse.Rhizoctonia solani has13AGs.The binucleate Rhizoctonia spp.include21AGs(Sneh,Burpee, and Ogoshi,1991),and the uninucleate Rhizoctonia spp.in-clude only one AG to date(Hietala,Sen,and Lilja,1994;Sen, Hietala,and Zelmer,1999).

The Rhizoctonia solani(multinucleate)AGs known to be associated with orchids are AG-6and AG-12(Carling,1996; Carling et al.,1999;but see Masuhara,Katsuya,and Yama-guchi,1993).Nevertheless,the most common group of orchid mycorrhizal fungi is binucleate Rhizoctonia(Currah et al., 1997).Uninucleate Rhizoctonia have not been previously re-ported from orchid roots.

Molecular systematics has substantially advanced the tax-onomy of Rhizoctonia spp.(Vilgalys and Gonza′lez,1990; Cubeta and Vilgalys,1997;Kuninaga et al.,1997;Salazar et al.,2000;Gonza′lez et al.,2001)and orchid mycorrhizae(Tay-lor and Bruns,1997,1999;Pope and Carter,2001;Kristiansen et al.,2001),mostly based on nuclear ribosomal internal tran-

1852

November 2002]

1853

O TERO ET AL .—T ROPICAL ORCHID MYCORRHIZAE T ABLE 1.

Study sites.

Site

Latitude

Longitude

Elevation (m)

Vegetation

Holdridge life zone

Cambalache Cayey

Charco Azul Dorado N.Dorado S.Guajataca Guanica Maricao Mona

Sabana Seca San Cristobal Tortuguero 18?30?N 18?05?N 18?05?N 18?20?N 18?15?N 18?25?N 18?00?N 18?15?N 18?05?N 18?25?N 18?15?N 18?27?N 66?20?W 66?00?W 66?05?W 66?35?W 67?00?W 67?00?W 67?15?W 67?00?W 67?55?W 66?10?W 66?10?W 66?30?W 20–40800–850600–6505–1020–40350–40020–50800–85020–4030–40600–6405–10Secondary forest Secondary forest Mature forest Secondary forest Secondary forest Mature forest Mature forest Mature forest Mature forest Secondary forest

Pasture with Psidium guajava Pasture with Randia aculeata Subtropical moist forest Subtropical wet forest Subtropical moist forest Subtropical moist forest Subtropical moist forest Subtropical moist forest Subtropical dry forest Subtropical wet forest Subtropical dry forest Subtropical moist forest Subtropical moist forest Subtropical moist forest

T ABLE 2.Host orchid species studied.

Species Subfamily/subtribe a No.popu-lations sampled No.plants sampled

Distribution b

Campylocentrum fasciola

Campylocentrum ?liforme Erythrodes plantaginea Epidendroideae/Angraecinae Epidendroideae/Angraecinae Orchidoideae/Goodyerinae 111221Greater Antilles and Central and South America Cuba,Hispaniola and Puerto Rico West Indies

Ionopsis satyrioides Epidendroideae/Oncidiinae 12Grater Antilles,Martinique,Panama and northern South America

Ionopsis utricularioides Epidendroideae/Oncidiinae 412Central America,Florida (USA),Galapagos Islands,Mexi-co,tropical South America and West Indies

Oeceoclades maculata Epidendroideae/Eulophiinae 12Tropical Africa,Florida,Panama,South America and West Indies

Oncidium altissimum Psychilis monensis Tolumnia variegata

Epidendroideae/Oncidiinae Epidendroideae/Laeliinae Epidendroideae/Oncidiinae

116

1220Lesser Antilles and Puerto Rico Mona Island Greater Antilles

a Based on Cameron et al.(1999)and Freudenstein and Chase (2001).b

Based on Ackerman (1995).

scribed spacer (ITS)sequences.Pope and Carter (2001)stud-ied ITS sequences of Rhizoctonia solani AGs including orchid mycorrhizal fungi from Australia.Kristiansen et al.(2001)am-pli?ed rDNA from terrestrial orchids of Europe and North America and sequenced a tropical mycorrhizal fungus from Asia.However,the phylogenetic relationships of most tropical orchid mycorrhizal fungi remain unknown.

In the present study we addressed the following questions:(1)What are the phylogenetic placement and diversity of Puerto Rican Rhizoctonia -like endophytes relative to other Rhizoctonia ?Based on the literature we expected to ?nd a variety of fungi related to Ceratobasidium ,Thanatephorus ,and Tulasnella .(2)What is the level of speci?city of epiphytic orchids for their Rhizoctonia -like fungi?If there is speci?city,then we expect that the fungi isolated from a single orchid species will belong to a single fungal clade.And ?nally,(3)what is the phylogenetic relationship between uni-and binu-cleate Rhizoctonia -like fungi associated with orchids?We ex-pected consistent differences in morphology and phylogeny between uni-and binucleate Rhizoctonia -like fungi from Puerto Rico.

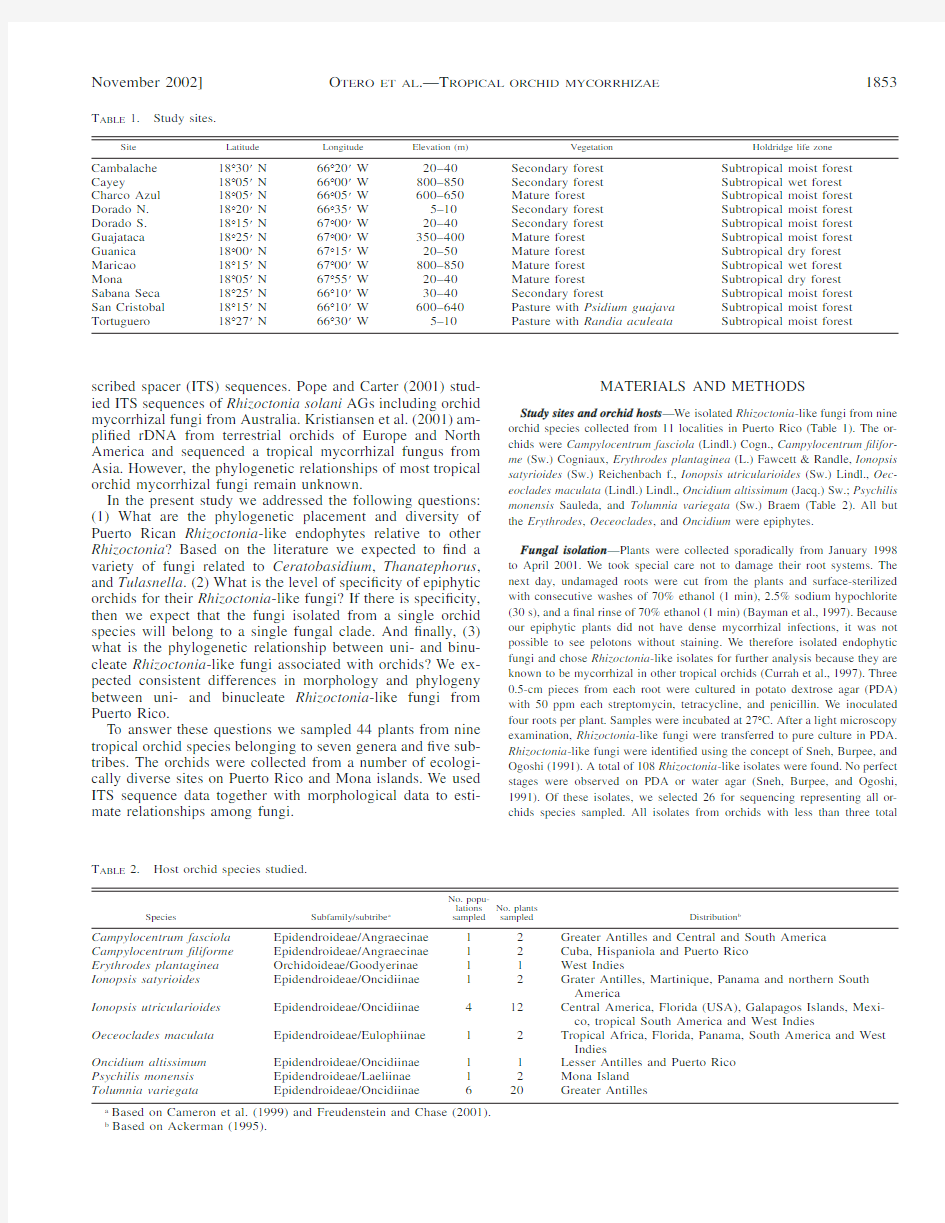

To answer these questions we sampled 44plants from nine tropical orchid species belonging to seven genera and ?ve sub-tribes.The orchids were collected from a number of ecologi-cally diverse sites on Puerto Rico and Mona islands.We used ITS sequence data together with morphological data to esti-mate relationships among fungi.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study sites and orchid hosts —We isolated Rhizoctonia -like fungi from nine orchid species collected from 11localities in Puerto Rico (Table 1).The or-chids were Campylocentrum fasciola (Lindl.)Cogn.,Campylocentrum ?lifor-me (Sw.)Cogniaux,Erythrodes plantaginea (L.)Fawcett &Randle,Ionopsis satyrioides (Sw.)Reichenbach f.,Ionopsis utricularioides (Sw.)Lindl.,Oec-eoclades maculata (Lindl.)Lindl.,Oncidium altissimum (Jacq.)Sw.;Psychilis monensis Sauleda,and Tolumnia variegata (Sw.)Braem (Table 2).All but the Erythrodes ,Oeceoclades ,and Oncidium were epiphytes.

Fungal isolation —Plants were collected sporadically from January 1998to April 2001.We took special care not to damage their root systems.The next day,undamaged roots were cut from the plants and surface-sterilized with consecutive washes of 70%ethanol (1min),2.5%sodium hypochlorite (30s),and a ?nal rinse of 70%ethanol (1min)(Bayman et al.,1997).Because our epiphytic plants did not have dense mycorrhizal infections,it was not possible to see pelotons without staining.We therefore isolated endophytic fungi and chose Rhizoctonia -like isolates for further analysis because they are known to be mycorrhizal in other tropical orchids (Currah et al.,1997).Three 0.5-cm pieces from each root were cultured in potato dextrose agar (PDA)with 50ppm each streptomycin,tetracycline,and penicillin.We inoculated four roots per plant.Samples were incubated at 27?C.After a light microscopy examination,Rhizoctonia -like fungi were transferred to pure culture in PDA.Rhizoctonia -like fungi were identi?ed using the concept of Sneh,Burpee,and Ogoshi (1991).A total of 108Rhizoctonia -like isolates were found.No perfect stages were observed on PDA or water agar (Sneh,Burpee,and Ogoshi,1991).Of these isolates,we selected 26for sequencing representing all or-chids species sampled.All isolates from orchids with less than three total

1854[Vol.89

A MERICAN J OURNAL

OF

B

OTANY Fig.1.Maximum likelihood tree of the ITS sequences of Ceratobasidium fungi.Numbers in the branches represent the bootstrapping percentage that supports the branch.Numbers in parentheses are the number of nuclei of each isolate.

isolates were included.Among isolates from T.variegata and I.utriculariodes (the most heavily sampled species)isolates were chosen based on morpho-logical diversity on PDA.

DNA isolation and ITS ampli?cation —The DNA of 26of the Rhizoctonia -like isolates was extracted following the procedure of Lee and Taylor (1990).The polymerase chain reaction (PCR)was performed using the primers ITS-1and ITS-4(White et al.,1990).The PCR products were cleaned using Qiaquick columns (Qiagen,Valencia,California,USA),according to the man-ufacturer’s instructions,and sequenced in both directions.Each 5-?L sequenc-ing reaction consisted of 1?L ABI PRISM BigDye Terminator Cycle Se-quencing Ready Reaction Mix (Applied Biosystems,Foster City,California,USA),1?L 5?dilution buffer (40mmol/L Tris HCl,pH 9,1mmol/L MgCl 2),1?mol/L of primer,and 2.5?mol/L template DNA.The sequencing cycle consisted of 95?C for 10s,50?C for 5s,and 60?C for 4min,for 40cycles.The sequencing product was precipitated in 60%isopropanol and re-suspended in 1.5?L of loading buffer (5:1de-ionized formamide:25mmol/L EDTA (pH 8.0),0.05%mass/volume blue dextran Amresco,Solon,Ohio,USA).Reactions were denatured at 90?C for 3min,loaded onto 6%ther-mopage acrylamide gels,and run on the ABI PRISM 377Sequencer (Applied Biosystems,Foster City,California,USA)for 4h.

We edited both strands of the sequences using the Sequencher 3.0program (Gene Codes Corporation,Ann Arbor,Michigan,USA),and the resulting consensus sequences were aligned with sequences published in GenBank.In order to align positions resulting from insertions and deletions (indels),se-quence alignment was performed using SOAP v1.05a (Lo ¨ytynoja and Mil-inkovitch,2001).Twenty-four Clustal W (Thomson,Higgins,and Gibbons,1994)alignments were produced,varying the gap opening penalty between 15and 25in steps of 2,and the gap extension penalty between 8and 14also in steps of 2.The resulting consensus alignments were assessed by eye.All isolates from O.maculata and some from P.monensis were excluded from the phylogenetic analysis because (1)we had no evidence that they were mycorrhizal fungi,(2)the sequences were not related to any known mycor-rhizal fungi,and (3)the sequences were so divergent that they precluded unambiguous alignment.The remaining sequences were subjected to a Mod-eltest 3.06to determine the mode of evolution to be used for phylogenetic analysis (Posada and Crandall,1998).We also included sequences of other uni-and binucleate Ceratobasidium gleaned from GenBank (https://www.360docs.net/doc/f411659077.html,/v89/)using a BLAST search with a minimum score.The optimal distance model for our data was an HKW85distance.A neighbor joining (NJ)and a heuristic search with maximum likelihood (ML)method were done with PAUP (Swofford,1998)and MacClade (Maddison and Mad-dison,1992)using multinucleate Rhizoctonia fungi as the outgroup to con-struct a phylogram.Because the data generated the same topology using both methods,we present the ML tree with bootstrap values of 1000replications from the NJ tree.Finally,a homology distance using a corrected p was con-structed to produce a similarity matrix.

Morphological measurements —Fungal growth rate was measured from the average of two perpendicular diameters of the colony taken every 24h.Hy-phal length and width and monilioid cell length and width were measured in 20cells for each culture using light microscopy at 400?after staining with toluidine blue (Goh,Sim,and Lim,1992).The number of nuclei per cell was determined in 20young cells by ?uorescence microscopy at 500?after stain-ing with 1%Hoescht 33342solution for 10min.Each set of measurements was repeated in three different subcultures.

Statistical analysis —Student’s t tests were used to test signi?cance of dif-ferences in growth and morphological data.This was done to compare uni-and binucleate fungi and to compare uninucleate fungi isolated from T.var-iegata with those from I.utricularioides .All analyses were performed using the Minitab 11statistical software (Minitab,State College,Pennsylvania,USA)after ensuring data were normally distributed.The proportion of uni-and binucleate fungi isolated from different orchid species was compared by Fisher’s exact test.

RESULTS

Variation in isolation of Rhizoctonia-like fungi —Success in isolation of Rhizoctonia -like fungi varied among the nine orchid species.Of the 528cultures attempted we isolated 108Rhizoctonia -like fungi.Isolations were most successful with Ionopsis satyrioides (8of 24cultures:33%success),I.utri-cularioides (32of 144:22%),and Tolumnia variegata (58of 240:24%).Success rate for the other species varied from 4to 13%.We attempted to isolate fungi from other orchids (e.g.,Epidendrum spp.,Lepanthes spp.)without success.A great variety of other endophytic fungi were isolated from orchid roots including Xylaria spp.,Pestalotia spp.,Colletotrichum spp.,and many unidenti?ed fungi (data not shown).Phylogenetic analysis and diversity —Most of the orchid endophytes we studied were closely related to each other and formed a well-supported group within Ceratobasidium (Fig.1).All endophytes were closely related to different anasto-mosis groups of Ceratobasidium spp.

Two main clades were found in the phylogenetic analysis.One,the ABC clade,included most isolates from epiphytic

November2002]1855

O TERO ET AL.—T ROPICAL ORCHID MYCORRHIZAE

T ABLE3.Minimum percentage of homology within and among clades

of the ITS-1and ITS-2using uncorrected p distance.A,B,C,and

D?the Puerto Rican orchid Rhizoctonia endophyte clades;Uni-F

?uninucleate Rhizoctonia from Finland(Hietala,Vahala,and Han-

tula,2001);R.solani?multinucleate(Kuninaga et al.,1997).

Clade A B C D Uni-F R.solani

ITS-1

A

B

C

D

Uni-F R.solani 97.71

88.26

88.70

76.14

75.70

70.98

96.69

92.37

79.81

79.58

70.96

95.68

77.87

78.19

69.91

92.71

80.68

70.35

99.26

71.0869.74

ITS-2

A

B

C

D

Uni-F R.solani 99.07

92.59

95.83

84.17

84.68

80.85

95.83

93.98

81.82

80.98

81.56

99.52

84.00

84.63

82.66

95.38

80.38

77.28

99.11

76.8687.71

T ABLE4.Number of uni-and binucleate Rhizoctonia-like fungi iso-

lates isolated from roots of Puerto Rican orchids by host species.

Host

Cultures

attempted Uninucleate Binucleate Total

Campylocentrum fasciola

Campylocentrum?liforme

Erythrodes plantaginea

Ionopsis satyrioides

Ionopsis utricularioides

Oeceoclades maculata

Oncidium altissimum

Psychilis monensis

Tolumnia variegata

24

24

12

24

144

24

12

12

240

2

29

?a

35

2

2

1

6

3

3

1

?

23

2

2

1

8

32

3

1

1

58

Total5046641108

a Psychilis monensis is excluded from the uninucleate and binucleate

columns because of culture contamination prior to examination for nu-

clei.

orchids from Puerto Rico;the other,D clade,included an iso-late from Oncidium altissimum and one from Tolumnia var-iegata(Fig.1).The ABC clade was supported by a bootstrap-ping index of99%and the D clade by100%.The ABC clade included three well-supported subclades of endophytic Rhi-zoctonia-like fungi from Puerto Rican orchids(A,B,and C); bootstrapping values for each subclade were100,94,and94%, respectively(Fig.1).The ABC clade was monophyletic and included22of the26isolated fungi from the orchid species Campylocentrum fasciola,C.?liforme,Ionopsis satyrioides,I. utricularioides,and Tolumnia variegata.This ABC clade in-cluded a sequence of Ceratobasidium sp.AG-Q(AF354095, isolated from soil in Japan;Gonza′lez et al.,2001)(Fig.1). The D clade grouped with Ceratobasidium AG-H(AF354089, isolated from soil in Japan;Gonza′lez et al.,2001).

The two remaining isolates were jto048(from Psychilis mo-nensis of Mona Island),and jto109(from the terrestrial orchid E.plantaginea).The sequence from isolate jto109grouped with Ceratobasidium sp.AG-A,AG-Bo and Rhizoctonia AG-A.The sequence from jto048had no close matches.

Four groups of isolates had identical ITS sequences when the informative alignable bases were considered(jto075and jto091from I.satyroides;jto024and jto032,isolated from I. utricularioides;jto043and jto047from I.utricularioides;and jto071,jto072,jto115,jto118,and jto124,isolated from I.sa-tyroides,C.fasciola,and C.?liforme;Fig.1).In all cases the fungi with identical sequences came from the same study site; in one case(jto071and jto072)the isolates came from the same root and might have been a single colony.

The minimum homology among clades A,B,C,and D was always greater than92.7%(Table3).The homology among uninucleate Rhizoctonia from Finland and C.bicorne was 99.3%for ITS-1and99.1%for ITS-2.On the other hand,the homology among the R.solani samples was lower,69.7%for ITS-1and87.7%for ITS-2.

The most intensively sampled orchid species differed in the level of speci?city with their endophytic fungi.Five plants of T.variegata from four sites produced?ve isolates that be-longed to four different subclades(A,B,C,and D).On the other hand,four plants of I.utricularioides from two sites produced seven isolates that belonged to just one subclade(B).

Uni-vs.binucleate Rhizoctonia—Of108Rhizoctonia-like fungi,66(62.2%)were uninucleate(Table4).One isolate had both uni-and binucleate cells.There were no consistent ge-netic differences between uni-and binucleate fungi isolated from Puerto Rican orchids(Fig.1).Subclades A,B,and C had a mix of uni-and binucleate fungi.The only clade com-posed entirely of binucleate fungi was clade D,which had only two samples.Tropical,mycorrhizal Rhizoctonia that were uni-nucleate belonged to a distinct clade from the pathogenic uni-nucleate fungi from Finland and Norway(Hietala,Vahala,and Hantula,2001).

All three of the orchid species from which more than three fungi were isolated had at least one uninucleate Rhizoctonia-like fungus.In Tolumnia variegata,the most extensively sam-pled orchid species,60.3%of Rhizoctonia-like fungi were uni-nucleate.Ionopsis utricularioides had the highest proportion of uninucleate Rhizoctonia-like fungi with90.6%.The pro-portion of uninucleate Rhizoctonia-like fungi isolated from I. utricularioides was signi?cantly different from T.variegata (?2?9.20;df?1;P?0.002),I.satyroides(Fisher’s exact test,df?1,P?0.0005)and O.maculata(Fisher’s exact test, df?1,P?0.003).

The proportion of uninucleate Rhizoctonia-like fungi varied among sites(?2?40.6;df?5;P?0.0001).In the South Dorado site97.1%of fungi were uninucleate.Other well-rep-resented sites were San Cristo′bal,Tortuguero,and Cambalache with50.0,44.4,and55.5%,respectively.All fungi from Sa-bana Seca were uninucleate,but sample size was small(N?5).Differences among sites were not solely due to distribution of species:for isolates from T.variegata alone,there was a signi?cant difference among sites in the proportion of uninu-cleate Rhizoctonia-like fungi(?2?18.5;df?2;P?0.001). Morphological data were signi?cantly different between uni-and binucleate fungi for two of?ve parameters.There were differences in growth rate(measured centimetres per day) (uninucleate:mean?1.85;binucleate:mean?1.27;t?7.53, df?48,P?0.001)and width of monilioid cells(uninucleate: mean?11.3?m;binucleate:mean?10.9?m;t?2.10,df ?82,P?0.04),but not in hyphal length(uninucleate:mean ?45.0?m;binucleate:mean?47.4?m;t?1.22,df?73, P?0.23),hyphal width(uninucleate:mean?5.8?m;bi-nucleate:mean?5.8?m;t?0.03,df?65,P?0.98)and monilioid cell length(uninucleate:mean?21.6?m;binucle-ate:mean?21.4?m;t?0.23,df?62,P?0.82). Morphological differences among fungi from different or-

1856[Vol.89

A MERICAN J OURNAL OF

B OTANY

chid hosts were signi?cant for growth rate(F

2,291?10.66,P

K0.001),but not for hyphal length(F

2,291?0.38,P?0.68)

or hyphal width(F

2,291?

0.47,P?0.63).

DISCUSSION

Phylogenetic relationships—This is the?rst time that phy-logenetic relationships of Rhizoctonia-like fungi from tropical orchids have been studied using molecular methods.The phy-logenetic tree(Fig.1)suggests that the Puerto Rican Rhizoc-tonia-like endophytes of orchids are anamorphs of the genus Ceratobasidium.Most of the endophytic Rhizoctonia-like fun-gi from this study formed a monophyletic group(clade ABC, Fig.1).This clade also included Ceratobasidium AG-Q,iso-lated from soil in Japan.Ceratobasidium AG-H,also from Japanese soil,was the closest known relative to clade D.Cer-atobasidium AG-D from Japan and Ceratobasidium CAG-1 from USA were related to clades ABC and D.The teleo-morphs of AG-Q and AG-D are Ceratobasidium cornigerum (Bourd.)Rogers and C.gramineum(Ikata&T.Matsuura)On-iki,Ogoshi&Araki,respectively(Sneh,Burpee,and Ogoshi, 1991),suggesting that orchid endophytes belonging to clades ABC and D include at least two species.Unfortunately,we were not able to induce sexual structures under laboratory con-ditions,a common problem in this group(Vilgalys and Cubeta, 1994).

The two terrestrial orchids,Oeceoclades and Erythrodes, had fungi very different than epiphytic orchids.Isolates from Oeceoclades were too divergent to be included in our phylo-genetic analysis.The fungus isolated from E.plantaginea was closely related to three isolates of Ceratobasidium AG-A, which are separate from clades ABC and D. Ceratobasidium spp.are known as pathogens of turfgrasses and cereals(Currah et al.,1997)and have been reported as orchid endophytes in Australia,North America,and tropical Asia(Currah et al.,1997).Ceratorhiza,the anamorphic genus of Ceratobasidium(Currah,1991),is one of the most common endophytes isolated from temperate orchids(Zelmer and Cur-rah,1995;Currah et al.,1997),but has only once been re-ported from Neotropical orchids(Richardson,Currah,and Hambleton,1993).

There have been few attempts to isolate and identify Rhi-zoctonia-like fungi from neotropical orchids.Ceratorhiza goodyerae-repentis was reported in Campylocentrum macu-latum(Lindl.)Rolfe and Rodriguezia compacta Schltr.from Costa Rica(Richardson,Currah,and Hambleton,1993;Rich-ardson and Currah,1995).In Puerto Rico multinucleate Rhi-zoctonia-like fungi were isolated from Lepanthes spp.(Bay-man et al.,1997)and from bark of trees with orchid epiphytes (Tremblay et al.,1998).Endophytic fungal communities from tropical orchid roots are very rich and include both Rhizoc-tonia-like and non-Rhizoctonia-like fungi(Richardson,Cur-rah,and Hambleton,1993;Richardson and Currah,1995;Bay-man et al.,1997)yet little is known of their role in orchid biology.To choose only Rhizoctonia-like endophytes for my-corrhizal studies may miss fungi critical for orchid establish-ment.An alternative is to isolate pelotons for culturing(Had-ley,1970;Rasmussen,1995)or DNA ampli?cation(Kristian-sen et al.,2001).Unfortunately,many epiphytic tropical or-chids do not have the massive mycorrhizal infections of terrestrial orchids,making it dif?cult to isolate pelotons. There is evidence that our endophytic Rhizoctonia-like fungi are potential mycorrhizal symbionts(in the sense of Masuhara and Katsuya,1994).Morphology of pelotons in adult roots of Campylocentrum spp.,Ionopsis spp.,and Tolumnia variegata match the morphology of cultured Rhizoctonia-like fungi.Ad-ditionally,symbiotic germination experiments in vitro with seeds from I.utricularioides and T.variegata resulted in sig-ni?cantly enhanced development of orchid seedlings(J.T. Otero,P.Bayman and J.D.Ackerman,unpublished data). How divergent are subclades A,B,C,and D?A possible way to answer this question is to compare the levels of genetic variability within each clade and subclade with those of related fungal species.Percentage homology of ITS sequences among and within anastomosis groups of Rhizoctonia solani has been determined(Kuninaga et al.,1997).The minimum ITS-1and ITS-2sequence homology within A,B,and C subclades(Table 3)was higher than that reported for R.solani AG-1,but similar to R.solani AG-3and AG-4(Kuninaga et al.,1997).The minimum homology among endophytic subclades A,B,C,and D was higher than that among R.solani AG groups.A,B,C, and D are distinct entities that have similar levels of variation in the ITS regions as anastomosis groups of R.solani.How-ever,these comparisons are approximate because the algorithm used by Kuninaga et al.(1997)employed different weightings than the one used here.ITS-1was more variable than ITS-2 among Puerto Rican clades and also in R.solani(Kuninaga et al.,1997).

Uninucleate Rhizoctonia-like endophytes—The uninucle-ate condition has been reported in Rhizoctonia quercus(Bur-pee,Sanders,and Cole,1980)and in a Rhizoctonia pathogenic on wheat(Hall,1986).The only well-known species of uni-nucleate Rhizoctonia-like fungi occurs as a seedling pathogen of conifer nurseries in Finland and Norway(Hietala,Sen,and Lilja,1994).The reproductive structures of these fungi pro-duced under laboratory conditions were typical of Ceratobas-idium and?t the morphological concept of Ceratobasidium bicorne Erikss.&Ryv.(Hietala,1997).Molecular data con-?rmed this liaison(Hietala,Vahala,and Hantula,2001;Fig.

1).From molecular markers,uninucleate Rhizoctonia was con-sidered a genetically homogenous group,distinct from binu-cleate Rhizoctonia spp.(Lilja,Hietala,and Karjalainen,1996; Hietala,Vahala,and Hantula,2001).

The hyphal widths reported from the Finnish and Norwe-gian fungi(Hietala,Sen,and Lilja,1994)were similar to those obtained in this study.Additionally,monilioid cell widths and lengths from Puerto Rico?t within the range reported by Hie-tala,Sen,and Lilja(1994),but they found much more varia-tion than we did.Nevertheless,the analysis of ITS sequences shows that they are in different lineages within Ceratobasi-dium(Fig.1).This observation suggests that the uninucleate condition has appeared independently in two clades,the ABC clade from Puerto Rico and the uninucleate clade from Finland and Norway.We found an isolate with both uni-and binucle-ate cells,suggesting that the uninucleate condition may be plastic even in a single mycelium.The co-occurrence of uni-and binucleate cells in the same hyphae was also observed in Rhizoctonia from Finland(Hietala,Sen,and Lilja,1994).Mor-phological data show that the main difference between uni-and binucleate Rhizoctonia of orchid roots is the mycelial growth rate.Thus,changes between uni-and binucleate states may be associated with physiological or developmental pro-cesses.

In general,the uninucleate condition is rare(Hietala,1997), but our data suggest that it may be more common in epiphytic

November2002]1857

O TERO ET AL.—T ROPICAL ORCHID MYCORRHIZAE

orchids.Nonetheless,the proportion of uni-and binucleate Rhizoctonia-like fungi varied among species(Table4).Binu-cleate fungi were more broadly distributed among orchid spe-cies than uninucleate ones,but T.variegata and I.utricular-ioides had signi?cantly more uninucleate isolates than would be expected.

Speci?city in orchid mycorrhizae—Since the discovery that fungi are involved in orchid seed germination(Bernard,1909), speci?city in orchid mycorrhizae has been controversial(Har-ley and Smith,1983).Previous studies found either that or-chids are speci?c(Clements,1987;Taylor and Bruns,1997) or generalist(Hadley,1970;Smreciu and Currah,1989;Ma-suhara and Katsuya,1989,1991;Masuhara,Katsuya,and Ya-maguchi,1993;Rasmussen,1995)in their mycorrhizal sym-bioses.However,data from an extensive study of European orchids suggests that the degree of speci?city is variable among species(Muir,1989).

Speci?city is best assessed in a comparative context.For that reason,the difference in speci?city between Tolumnia variegata and Ionopsis utricularioides—two species similar in distribution,ecology,and taxonomic af?nity—is striking.En-dophytes from T.variegata appeared in all four subclades,but those from I.utricularoides appeared only in the B subclade (Fig.1).Tolumnia variegata has also been shown to be highly variable in morphology(Ackerman and Galarza-Pe′rez,1991) and isozymes(Ackerman and Ward,2000),but most compo-nents of variation were found to be within populations.Fur-thermore,Puerto Rican populations form a single taxon(Ack-erman,1995).These data suggest that I.utricularoides may be more speci?c than T.variegata in its association with Rhi-zoctonia-like fungi.Variation in speci?city was also evident within a single genus,as I.satyrioides had fungi in three sub-clades(A,B,and C)whereas those from I.utricularioides were in only one(subclade B).

Non-photosynthetic orchids are considered to have special-ist mycorrhizal associations in the sense that they can involve only ectomycorrhizal fungi rather than Rhizoctonia-like fungi (Taylor and Bruns,1997;but see McKendrick et al.,2002). However,the amount of variation shown by these ectomycor-rhizae(Taylor and Bruns,1997)is comparable to that of Rhi-zoctonia-like fungi of T.variegata,an orchid that we argue is a relative generalist in its mycorrhizal associations.

In conclusion,our data show(1)Puerto Rican epiphytic orchids are associated with Ceratobasidium spp.that may be undescribed but closely related to temperate isolates;(2)many mycorrhizal fungi from Puerto Rican orchids were uninucle-ate;(3)the uninucleate condition is not a good phylogenetic character in mycorrhizal fungi from Puerto Rico;and(4)spec-i?city of the orchid mycorrhizal association varies dramatical-ly even among closely related species.Although some species, such as non-photosynthetic orchids from temperate regions, have particular mycorrhizal fungi(Taylor and Bruns,1997), orchids appear to vary in degree of speci?city in their mycor-rhizal interactions more than previously thought.

LITERATURE CITED

A CKERMAN,J.D.1995.An orchid?ora of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands.

Memoirs of the New York Botanical Garden73:1–203.

A CKERMAN,J.D.,AND M.G ALARZA-P E′REZ.1991.Patterns and maintenance

of extraordinary variation in the Caribbean orchid,Tolumnia(Oncidium) variegata.Systematic Botany16:182–194.

A CKERMAN,J.D.,AND S.W ARD.1999.Genetic variation in a widespread

epiphytic orchid:where is the evolutionary potential?Systematic Botany 24:282–291.

A RDITTI,J.1992.Fundamentals of orchid biology.John Wiley,New York,

New York,USA.

B AYMAN,P.,L.L EBRO′N,R.L.T REMBLAY,AND J.L ODGE.1997.Variation

in endophytic fungi from roots and leaves of Lepanthes(Orchidaceae).

New Phytologist135:143–149.

B ERNARD,N.1909.L’evolution dans la symbiose.Annales des Sciences Na-

turelles Botanique,Paris9:1–196.

B URPEE,L.L.,P.L.S ANDERS,H.

C OLE,AN

D R.T.S HERWOOD.1980.Anas-

tomosis groups among isolates of Ceratobasidium cornigerum and re-lated fungi.Mycologia72:689–701.

C AMERON,K.M.,M.W.C HASE,W.M.W HITTEN,P.J.K ORES,D.C.J AR-

RELL,V.A.A LBERT,T.Y UKAWA,H.G.H ILLS,AND D.H.G OLDMAN.

1999.A phylogenetic analysis of the Orchidaceae:evidence from rbc L nucleotide sequences.American Journal of Botany86:208–224.

C ARLING,D.E.1996.Grouping in Rhizoctonia solani by hyphal anastomosis

reaction.In B.Sneh,S.Jabaji-Hare,S.Neate,and G.Dijst[eds.],Rhi-zoctonia species:taxonomy,molecular biology,ecology,pathology and control,37–47.Kluwer,Dordrecht,Netherlands.

C ARLING,D.E.,E.J.P OPE,K.A.B RAINARD,AN

D D.A.C ARTER.1999.

Characterization of mycorrhizal isolates of Rhizoctonia solani from an orchid including AG-12,a new anastomosis group.Phytopathology89: 942–946.

C LEMENTS,M.A.1987.Orchid-fungus-host associations of epiphytic orchids.

In K.Saito and R.Tanaka[eds.],Proceedings of the12th World Orchid Conference,80–83.12th World Orchid Conference,Tokyo,Japan.

C UBETA,M.A.,AN

D R.V ILGALYS.1997.Population biology of the Rhizoc-

tonia solani complex.Phytopathology87:480–484.

C URRAH,R.S.1991.Taxonomic and developmental aspects of the fungal

endophytes of terrestrial orchid mycorrhizae.Lindleyana6:211–213.

C URRAH,R.S.,S.H AMBLETON,AN

D A.S MRECIU.1988.Mycorrhizae and

mycorrhizal fungi of Calypso bulbosa.American Journal of Botany75: 739–752.

C URRAH,R.S.,L.W.Z ETTLER,S.H AMBLETON,AN

D K.A.R ICHARDSON.

1997.Fungi from orchid mycorrhizae.In J.Arditti and A.M.Pridgeon [eds.],Orchid biology:reviews and perspectives,vol.VII,117–170.Klu-wer,Dordrecht,Netherlands.

F REUDENSTEIN,J.V.,AND M.W.C HASE.2001.Analysis of mitocondrial

nad1b-c intron sequences in Orchidaceae:utility and coding of length-change characters.Systematic Botany26:643–657.

G OH,C.J.,A.A.S IM,AND G.L IM.1992.Mycorrhizal associations in some

tropical orchids.Lindleyana7:13–17.

G ONZA′LEZ,D.,D.E.C ARLING,S.K UNINAGA,R.V ILGALYS,AND M.C UB-

ETA.2001.Ribosomal DNA systematics of Ceratobasidium and Than-atephorus with Rhizoctonia anamorphs.Mycologia93:1138–1150.

H ADLEY,G.1970.Non-speci?city of symbiotic infection in orchid mycor-

rhizae.New Phytologist69:1015–1023.

H ALL,G.1986.A species of Rhizoctonia with uninucleate hyphae isolated

from roots of winter wheat.Transactions of the British Mycological So-ciety87:466–471.

H ARLEY,J.L.,AND S.E.S MITH.1983.Mycorrhizal symbiosis.Academic

Press,London,UK.

H IETALA,A.1997.The mode of infection of a pathogenic uninucleate Rhi-

zoctonia sp.in conifer seedling roots.Canadian Journal of Forest Re-search27:471–480.

H IETALA,A.M.,R.S EN,AND A.L ILJA.1994.Anamorphic and teleomorphic

characteristics of a uninucleate Rhizoctonia sp.isolated from the roots of nursery grown conifer seedlings.Mycological Research98:1044–1050.

H IETALA,A.M.,J.V AHALA,AND J.H ANTULA.2001.Molecular evidence

suggests that Ceratobasidium bicorne has an anamorph known as a co-nifer pathogen.Mycological Research105:555–562.

K RISTIANSEN,K.A.,D.L.T AYLOR,R.K JOLLER,H.N.R ASMUSSEN,AND S.

R OSENDAHL.2001.Identi?cation of mycorrhizal fungi from single pe-lotons of Dactylorhiza majalis(Orchidaceae)using single-strand confor-mation polymorphism and mitochondrial ribosomal large subunit DNA sequences.Molecular Ecology10:2089–2093.

K UNINAGA,S.,T.N ATSUAKI,T.T AKEUCHI,AND R.Y OKOSAWA.1997.Se-quence variation of the rDNA ITS regions within and between anasto-mosis groups in Rhizoctonia solani.Current Genetics32:237–243.

L EE,S.B.,AND J.W.T AYLOR.1990.Isolation of DNA from fungal mycelia and single spores.In M.A.Innis,D.H.Gelfand,J.J.Snisnsky,and T.

1858[Vol.89

A MERICAN J OURNAL OF

B OTANY

J.White[eds.],PCR protocols:a guide to methods and applications, 282–287.Academic Press,San Diego,California,USA.

L ILJA,A.,A.M.H IETALA,AND R.K ARJALAINEN.1996.Identi?cation of a uninucleate Rhizoctonia sp.by pathogenicity,hyphal anastomosis and RAPD analysis.Plant Pathology45:997–1006.

L O¨YTYNOJA,A.,AND M.C.M ILINKOVITCH.2001.SOAP,cleaning multiple alignments for unstable blocks.Bioinformatics17:573–574.

M ADDISON,W.P.,AND D.R.M ADDISON.1992.MacClade:analysis of phy-logeny and character evolution,version3.Sinauer,Sunderland,Massa-chusetts,USA.

M ASUHARA,G.,AND K.K ATSUYA.1989.Effects of mycorrhizal fungi on seed germination and early growth of three Japanese terrestrial orchids.

Scientia Horticulturae37:331–337.

M ASUHARA,G.,AND K.K ATSUYA.1991.Fungal coil formation of Rhizoc-tonia repens in seedlings of Galeola septentrionalis(Orchidaceae).Bo-tanical Magazine of Tokyo104:275–281.

M ASUHARA,G.,AND K.K ATSUYA.1994.In situ and in vitro speci?city be-tween Rhizoctonia spp.and Spiranthes sinensis(Persoon)Ames.var.

amoena(M.Bieberstein)Hara(Orchidaceae).New Phytologist127:711–718.

M ASUHARA,G.,K.K ATSUYA,AND K.Y AMAGUCHI.1993.Potential for sym-biosis of Rhizoctonia solani and binucleate Rhizoctonia with seeds of Spiranthes amoena var.amoena in vitro.Mycological Research97:746–752.

M C K ENDRICK,S.L.,J.R.L EAKE,B.L.T AYLOR,AND B.J.R EAD.2002.

Symbiotic germination and the development of the myco-heterotroph Neottia nidus-avis in nature and its requirement for locally distributed Sebacina spp.New Phytologist154:233–248.

M OORE,R.T.1988.The genera Rhizoctonia-like fungi:Ascorhizoctonia,Cer-atorhiza gen.Nov.,Eupulorhiza gen.nov.,Moniliopsis,and Rhizoctonia.

Mycotaxon29:91–99.

M UIR,H.J.1989.Germination and mycorrhizal fungus compatibility in Eu-ropean orchids.In H.W.Prichard[ed.],Modern methods in orchid con-servation:the role of physiology,ecology and management,39–56.Cam-bridge University Press,Cambridge,UK.

P OPE,E.J.,AND D.A.C ARTER.2001.Phylogenetic placement and host speci?city of mycorrhizal isolates AG-6and AG-12in the Rhizoctonia solani species complex.Mycologia93:712–719.

P OSADA,D.,AND K.A.C RANDALL.1998.Modeltest:testing the model of DNA substitution.Bioinformatics14:817–818.

R ASMUSSEN,H.N.1995.Terrestrial orchids:from seeds to mycotrophic plants.Cambridge University Press,Cambridge,UK.

R ICHARDSON,K.A.,AND R.S.C URRAH.1995.The fungal community as-sociated with the roots of some rainforest epiphytes of Costa Rica.Sel-byana16:49–73.

R ICHARDSON,K.A.,R.S.C URRAH,AND S.H AMBLETON.1993.Basidio-mycetous endophytes from the roots of Neotropical epiphytic Orchida-ceae.Lindleyana8:127–137.

S ALAZAR,O.,M.C.J ULIAN,M.Y ACUMACHI,AND V.R UBIO.2000.Phylo-

genetic grouping of cultural types of Rhizoctonia solani AG2-2based on ribosomal ITS sequences.Mycologia92:505–509.

S EN,R.,A.H IETALA,AND C.Z https://www.360docs.net/doc/f411659077.html,mon anastomosis and ITS-RFLP groupings among binucleate Rhizoctonia isolates representing root endophytes of Pinus sylvestris,Ceratorhiza spp.from orchid mycorrhizas and a phytopathogenic anastomosis group.New Phytologist144:331–341.

S MRECIU,E.A.,AND R.S.C URRAH.1989.Symbiotic germination of seeds of terrestrial orchids of North America and Europe.Lindleyana4:6–15. S NEH,B.,L.B URPEE,AND A.O GOSHI.1991.Identi?cation of Rhizoctonia species.American Phytopathological Society,St.Paul,Minnesota,USA. S WOFFORD,D.L.1998.PAUP:phylogenetic analysis using parsimony and other methods,version4.0.0d54,https://www.360docs.net/doc/f411659077.html,boratory of Molecular System-atics,Smithsonian Institution,Washington,D.C.,USA.

T AYLOR,L.D.,AND T.D.B RUNS.1997.Independent,specialized invasion of ectomycorrhizal mutualism by two nonphotosynthetic orchids.Pro-ceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,USA94:4510–4515.

T AYLOR,L.D.,AND T.D.B RUNS.1999.Population,habitat and genetic correlates of mycorrhizal specialization in the‘‘cheating’’orchids Cor-allorhiza maculata and C.mertensiana.Molecular Ecology8:1719–1732.

T HOMSON,J.D.,D.G.H IGGINS,AND T.J.G IBBONS.1994.CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting,position-speci?c gap penalties and weight matrix choice.Nucleic Acids Research22:4673–4680.

T REMBLAY,R.L.,J.K.Z IMMERMAN,L.L EBRON,P.B AYMAN,I.S ASTRE,F.

A XELROD,AND J.A LERS-G ARCIA.1998.Host speci?city and low repro-

ductive success in the rare endemic Puerto Rican orchid Lepanthes car-itensis.Biological Conservation85:297–304.

V ILGALYS,R.,AND M.A.C UBETA.1994.Molecular systematics and popu-lation biology of Rhizoctonia.Annual Review of Phytopathology32: 135–155.

V ILGALYS,R.,AND D.G ONZA′LEZ.1990.Ribosomal DNA restriction frag-ment length polymorphisms in Rhizoctonia solani.Phytopathology80: 151–158.

W ARCUP,J.H.,AND P.H.B.T ALBOT.1966.Perfect states of some Rhizoc-tonia.Transactions of the British Mycological Society49:427–435.

W ARCUP,J.H.,AND P.H.B.T ALBOT.1971.Perfect states of Rhizoctonia associated with orchids III.New Phytologist70:35–40.

W HITE,T.J.,T.B RUNS,S.L EE,AND J.W.T AYLOR.1990.Ampli?cation and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics.In M.A.Innis,D.H.Gelfand,J.J.Sninsky,and T.J.White[eds.],PCR protocols:a guide to methods and applications,315–322.Academic Press,New York,New York,USA.

Z ELMER,C.D.,AND R.S.C URRAH.1995.Evidence for fungal liaison be-tween Corallorhiza tri?da(Orchidaceae)and Pinus contorta(Pinaceae).

Canadian Journal of Botany73:862–866.

Z ETTLER,L.W.,J.C.B URKHEAD,AND J.A.M https://www.360docs.net/doc/f411659077.html,e of a mycorrhizal fungus from Epidendrum conopseum to germinate seed of Encyclia tampensis in vitro.Lindleyana14:102–105.

“的、地、得”用法分析及练习(后附答案)

“的、地、得”用法分析及练习(后附答案) 一、的、地、得用法分析: “的”后面跟的都是表示事物名称的词或词语,如:敬爱的总理、慈祥的老人、戴帽子的男孩、珍贵的教科书、鸟的天堂、伟大的祖国、有趣的情节、优雅的环境、可疑的情况、团结友爱的集体、他的妈妈、可爱的花儿、谁的橡皮、清清的河水...... “地”后面跟的都是表示动作的词或词语,如:高声地喊、愉快地唱、拼命地逃、疯狂地咒骂、严密地注视、一次又一次地握手、迅速地包围、沙沙地直响、斩钉截铁地说、从容不迫地申述、用力地踢、仔细地看、开心地笑笑......” “得”前面多数是表示动作的词或词语,少数是形容词;后面跟的都是形容事物状态的词或词语,表示怎么怎么样的,如:走得很快、踩得稀烂、疼得直叫唤、瘦得皮包骨头、红得发紫、气得双脚直跳、理解得十分深刻、乐得合不拢嘴、惊讶得目瞪口呆、大得很、扫得真干净、笑得多甜啊...... 二、的、地、得用法补充说明: 1、如果“de”的后面是“很、真、太”等这些词,十有八九用“得”。 2、有一种情况,如“他高兴得一蹦三尺高”这句话里,后面的“一蹦三尺高”虽然是表示动作的,但是它是来形容“高兴”的程度的,所以也应该用“得”。

三、的、地、得用法总结: 1、“的”前面的词语一般用来修饰、限制“的”后面的事物,说明“的”后面的事物怎么样。结构形式一般为:修饰、限制的词语+的+名词。 2、“地”前面的词语一般用来形容“地”后面的动作,说明“地”后面的动作怎么样。结构方式一般为:修饰、限制的词语+地+动词。 3、“得”后面的词语一般用来补充说明“得”前面的动作怎么样,结构形式一般为:动词(形容词)+得+补充、说明的词语。 四、的、地、得用法例句: 1. 蔚蓝色的海洋,波涛汹涌,无边无际。 2. 向日葵在微风中向我们轻轻地点头微笑。 3. 小明在海安儿童公园玩得很开心。 五、“的、地、得”的读音: “的、地、得”是现代汉语中高频度使用的三个结构助词,都起着连接作用;它们在普通话中都各自有着各自的不同的读音,但当他们附着在词,短语,句子的前面或后面,表示结构关系或某些附加意义的时候都读轻声“de”,没有语音上的区别。 但在书面语中有必要写成三个不同的字,这样可以区分他们在书面语用法上的不同。这样做的好处,就是可使书面语言精确化。

标点符号用法分析

标点符号用法 一、标点符号 标点符号:辅助文字记录语言的符号,是书面语的有机组成部分,用来表示语句的停顿、语气以及标示某些成分(主要是词语)的特定性质和作用。 句子:前后都有较大停顿、带有一定的语气和语调、表达相对完整意义的语言单位。 复句:由两个或多个在意义上有密切关系的分句组成的语言单位,包括简单复句(内部只有一层语义关系)和多重复句(内部包含多层语义关系)。 分句:复句内两个或多个前后有停顿、表达相对完整意义、不带有句末语气和语调、有的前面可添加关联词语的语言单位。 陈述句:用来说明事实的句子。 祈使句:用来要求听话人做某件事情的句子。 疑问句:用来提出问题的句子。 感叹句:用来抒发某种强烈感情的句子。 词语:词和短语(词组)。词,即最小的能独立运用的语言单位。短语,即由两个或两个以上的词按一定的语法规则组成的表达一定意义的语言单位,也叫词组。 二、分类 标点符号分为点号和标号两大类。

点号的作用是点断,主要表示说话时的停顿和语气。点号又分为句末点号和句内点号。 句末点号用在句末,表示句末停顿和句子的语气,包括句号、问号、叹号。 句内点号用在句内,表示句内各种不同性质的停顿,有逗号、顿号、分号、冒号。 标号的作用是标明,主要标示某些成分(主要是词语)的特定性质和作用。包括引号、括号、破折号、省略号、着重号、连接号、间隔号、书名号、专名号、分隔号。 (一)句号 1.用于句子末尾,表示陈述语气。使用句号主要根据语段前后有较大停顿、带有陈述语气和语调,并不取决于句子的长短。 2.有时也可表示较缓和的祈使语气和感叹语气。 请您稍等一下。 我不由地感到,这些普通劳动者也是同样值得尊敬的。 (二)问号 主要表示句子的疑问语气。形式是“?”。 1.用于句子末尾,表示疑问语气(包括反问、设问等疑问类型)。使用问号主要根据语段前后有较大停顿、带有疑问语气和语调,并不取决于句子的长短。 2.选择问句中,通常只在最后一个选项的末尾用问号,各个选项之间一般用逗号隔开。当选项较短且选项之间几乎没有停顿时,选项之间可不用逗号。当选项较多或较长,或有意突出每个选项的独立性时,也可每个选项之后都用问号。 3.问号也有标号的用法,即用于句内,表示存疑或不详。 马致远(1250?―1321)。 使用问号应以句子表示疑问语气为依据,而并不根据句子中包含有疑问词。当含有疑问词的语段充当某种句子成分,而句子并不表示疑问语气时,句末不用问号。

定语从句用法分析

定语从句用法分析 定语从句在整个句子中担任定语,修饰一个名词或代词,被修饰的名词或代词叫先行词。定语从句通常出现在先行词之后,由关系词(关系代词或关系副词)引出。 eg. The boys who are planting trees on the hill are middle school students 先行词定语从句 #1 关系词: 关系代词:who, whom, whose, that, which, as (句子中缺主要成份:主语、宾语、定语、表语、同位语、补语), 关系副词:when, where, why (句子中缺次要成份:状语)。 #2 关系代词引导的定语从句 关系代词引导定语从句,代替先行词,并在句中充当主语、宾语、定语等主要成分。 1)who, whom, that 指代人,在从句中作主语、宾语。 eg. Is he the man who/that wants to see you?(who/that在从句中作主语) ^ He is the man who/whom/ that I saw yesterday.(who/whom/that在从句中作宾语) ^ 2)whose 用来指人或物,(只用作定语, 若指物,它还可以同of which互换)。eg. They rushed over to help the man whose car had broken down. Please pass me the book whose cover is green. = the cover of which/of which the cover is green. 3)which, that指代物,在从句中可作主语、宾语。 eg. The package (which / that)you are carrying is about to come unwrapped. ^ (which / that在从句中作宾语,可省略) 关系代词在定语从句中作主语时,从句谓语动词的人称和数要和先行词保持一致。 eg. Is he the man who want s to see you? #3.关系副词引导的定语从句 关系副词when, where, why引导定语从句,代替先行词(时间、地点或理由),并在从句中作状语。 eg. Two years ago, I was taken to the village where I was born. Do you know the day when they arrived? The reason why he refused is that he was too busy. 注意: 1)关系副词常常和"介词+ which"结构互换 eg. There are occasions when (on which)one must yield (屈服). Beijing is the place where(in which)I was born. Is this the reason why (for which)he refused our offer? * 2)在非正式文体中,that代替关系副词或"介词+ which",放在时间、地点、理由的名词,在口语中that常被省略。 eg. His father died the year (that / when / in which)he was born. He is unlikely to find the place (that / where / in which)he lived forty years ago.

comparison的用法解析大全

comparison的用法解析大全 comparison的意思是比较,比喻,下面我把它的相关知识点整理给大家,希望你们会喜欢! 释义 comparison n. 比较;对照;比喻;比较关系 [ 复数 comparisons ] 词组短语 comparison with 与…相比 in comparison adj. 相比之下;与……比较 in comparison with 与…比较,同…比较起来 by comparison 相比之下,比较起来 comparison method 比较法 make a comparison 进行比较 comparison test 比较检验 comparison theorem 比较定理 beyond comparison adv. 无以伦比 comparison table 对照表 comparison shopping 比较购物;采购条件的比较调查 paired comp arison 成对比较 同根词 词根: comparing adj. comparative 比较的;相当的 comparable 可比较的;比得上的 adv. comparatively 比较地;相当地 comparably 同等地;可比较地 n.

comparative 比较级;对手 comparing 比较 comparability 相似性;可比较性 v. comparing 比较;对照(compare的ing形式) 双语例句 He liked the comparison. 他喜欢这个比喻。 There is no comparison between the two. 二者不能相比。 Your conclusion is wrong in comparison with their conclusion. 你们的结论与他们的相比是错误的。 comparison的用法解析大全相关文章: 1.by的用法总结大全

基于语料库的“人家”用法分析

基于语料库的“人家”用法分析 “人家”是北方方言中口语化的指称代词,语义非常丰富。不同的指称用法蕴含说话人不同的情感态度,如称羡讽刺、同情自怜,从而达到不同的语用效果,即语用移情或语用离情的效果。本文借助于语料库,为分析“人家”的用法及语用效果提供了科学的支撑和有力的支持。 标签:“人家” 语用效果语用功能 一、引言 “人家”既可以用作旁指代词,虚指除自己以外的“别人”,又可以用作第三人称代词,实指“他”或“他们”,也可以和“人家”后面的名词性成分构成同位语,有复指的用法。此外,“人家”还可以用来指称自己或是听话人“你”或“您”。“人家”有如此丰富的指称用法蕴含了说话人怎样的情感态度?本文从语用学的角度,借助语料库这一工具对“人家”一词的用法进行具体分析。 (一)研究内容 本文要探讨的问题如下:1.“人家”的具体用法有哪些?哪些常用,哪些不常用?2.“人家”在不同的语境、不同的用法中主要表达说话人怎样的情感态度? 3.“人家”在使用中语用移情功能多还是语用离情功能多? 笔者认为,“人家”不同指称义的使用,直接体现着言者对不同人际关系的评判,蕴含着言者不同的情感态度。过去对“人家”的研究主要集中在句法层面和语义层面,从语用层面进行分析研究的相对匮乏,并且大多只是从少量例子出发,作出概括分析,带有强烈的主观色彩。因此借用语料库这一工具,对“人家”的用法及语用效果进行科学客观的分析,是本文的根本出发点。 (二)研究方法 本文首先利用国家语委现代汉语平衡语料库检索出1794个包含“人家”的语料。其次,利用Concordance Sampler抽样软件,抽取出500个样本逐个进行分析,剔除不符合条件的名词用法,剩余404个“人家”作代词的语料。再次,通过人工标记的方法,按照指称对象的不同,对“人家”的用法进行分类。最后,由于“人家”的基本义“别人”使用时比较客观,不带感情色彩,因而笔者对“人家”其余四种用法的166个语料一一分析了其表达的说话人的情感倾向,进而分析其语用表达效果。 二、“人家”的用法分析 “人家”的归属问题,历来备受争议。本文综合各家之言,将“人家”的用法分为5类:1.旁指;2.复指;3.第一人称;4.第二人称;5.第三人称。通过对所得语

虚词“了”的用法分析

虚词“了”的用法分析 摘要:现代汉语中,虚词“了(le)”不论是在口语中,还是书面语中,使用频 率都比较高。虚词“了”有两个,语气词“了”和助词“了”。两者字形、读音相同,但具体用法和语法作用却不相同。 关键字: 虚词“了”、语气词、助词、具体用法、语法作用 正文: 注意:语气词“了”和助词“了”可同在句末。且都在句子末尾,可能是助词“了”,也有可能是语气词“了”,但意思有区别。 如:她写了。(“了”若是语气词,则表示动作在进行,若“了”是助词,则表示动作已经完成) 一、助词“了”。 1.紧跟在动词之后,表示动作的完成。 如:1)王春生从来没有忘了他爹的惨死跟妈的眼泪。(周立波《暴风骤雨》) 2)还没有等到发榜,全国高校统考开始了,我当然还应该参1《谈谈句末的“了”》张兰英-《东岳丛林》-2005

加。(余秋雨《霜冷长河》) 也可以表示将要发生的事情或假设可能发生的事情的完成。如:跟他们谈话就是我的工作,你要有什么话等我闲了再谈吧。(《赵树理选集》) 2.如果动词之后紧跟着另外一个动词或形容词作补语时,“了”就放在了补语之后。 如:1) "祥哥!"她往前凑了凑,"我把东西都收拾好了。"(老舍《骆驼祥子》) 2)他决定去拉车,就拉车去了。(老舍《骆驼祥子》) 3) 整整的三年,他凑足了一百块钱!(老舍《骆驼祥子》) 3. “了”放在由两个动词构成的并列词组后面(表示两个动词同时或者连续完成)。 如:这项政策的实施进一步巩固和加强了海内外中华儿女大团结。 4. 连谓句、兼语句中,助词“了”一般用在后一动词之后2。如:她找我借了两本书。连谓句强调前一动作完成后才开始后一动作时,兼语句前一动作完成时,助词“了”可在前一动词后。如:临时组织了一些人去支援五车间。 5. 有些动词后面的助词“了”表示动作有了结果,即加在动词后面的“掉”很相似。这类动词有:泼、扔、放、碰、砸、捧、磕、撞、踩、伤、杀、宰、切、冲、卖、还、毁、忘、丢、关、喝、吃、咽、吞、涂、抹、擦等。这个意义的“了”可以用在命令句和‘把’字句。2吕叔湘《现代汉语八百词》(1981商务印书馆)第315页。

“是”的用法分析

“是”的用法分析 序言 “是”的一些用法在古代有,但是现代已经不用或使用频率很低,还有些现代才出现,古时候没有。现代汉语中“是”在书面语和口语中出现的频率也是比较高的,但目前相关研究有的从“是”的词性分析有的从语法成份方面分析。为了尽量全面深入的了解并应用“是”,从而正确熟练的使用,使我们所学理论更好的联系实际应用,所以有必要对“是”的用法进行分析。 第一章:“是”的词性分析 汉语中,词性往往决定了一个字或词的用法与含义。所以我们首先从词性角度对“是”进行研究,从而分析它的用法。 一:“是”作形容词。 (一):表示对的,正确的。例如: 1:陶渊明《归去来兮辞》中:“实迷途其未远,觉今是而昨非”。(实在是误入迷途还不算太远,已经觉悟到现在是对的而过去是错的。) 2:斗争历史短的, 可以因其短而不负责; 斗争历史长的, 可以因其长而自以为是。对于诸如此类的东西, 如果没有自觉性, 那它们就会成为负担或包袱。(《毛泽东选集》第901页) (二):表示概括,凡是,任何。比如: 1:“是个有良知的人都会这么做”。 2:“是学生就要用心学习。” 二:“是”作代词。 表示此这。例如 1:林嗣环《口技》中“当是时,妇手拍儿声,口中呜声,儿含乳啼声,大儿初醒声,夫叱大儿声,一时齐发,众妙毕备”(这时候,妇人用手拍孩子的声音,口中呜呜哼唱的声音,小孩子含着乳头啼哭的声音,大孩刚刚醒来的声音,丈夫大声呵斥大孩子的声音,同时都响了起来,各种声音都表演得惟妙惟肖)。中的是可以解释为此或这的意思。 2:明朝张岱的代表作《湖心亭看雪》中:“是日更定,余拿一小舟,拥毳衣炉火,独往湖心亭看雪。”(这一天初更以后,我乘着一只小船,穿着毛皮衣,带着火炉,独自前往湖心亭欣赏雪景。) 三:“是”作名词。 (一):表示特定组织的事物或业务。比如范晔的《后汉书?桓谭冯衍列传》中“君臣不合,则国是无从定矣”。 “国事”与“国是”是近义同音词,二者都是名词,都指国家的政务、政事。但二者同中有异:

借代手法具体用法分析

借代手法具体用法分析 本文是关于借代手法具体用法分析,感谢您的阅读! 关于借代这种修辞手法,各类文章中的论述已经颇为详尽。一般来说,恰当地运用借代可以突出事物的本质特征,可以增强语言的形象性,可以使文章简洁精练,可以使文章语言富有变化和有幽默感……实际上,古典诗词里的借代还有其他一些方面的作用。 一、巧用借代,避免重复用字 李白《送羽林陶将军》中有“万里横戈探虎穴,三杯拔剑舞龙泉”一句。龙泉在古代常常被借代指宝剑。《送羽林陶将军》中,因为前面已用过“剑”字,故而后面才用龙泉代之;否则,一句中出现两个“剑”字——拔“剑”舞“剑”,不但会造成用词的重复,还会破坏这首诗的韵律。这首诗是一首三韵小律,押“先”韵,“剑”不合此韵,“泉”则在此韵之内。 白居易《赋得古原草送别》中有“远芳侵古道,晴翠接荒城”一句。“远芳”,即远处的芳草;“晴翠”,是沐浴在阳光下更加翠绿的青草。这两个词在词义上没有太大的区别。但是,如果两句都用芳草、绿草之类的词语描绘,显然会违背诗词不宜重复用字的审美规律。因此,诗人才用“远芳”和“晴翠”两个不同的词语借指草。这真是匠心独运之笔! 白居易《大林寺桃花》中有“人间四月芳菲尽,山寺桃花始盛开”一句。“芳菲”,本是花的香味,此处借代为花,从而避免了与下一句中出现的“花”重复,使用得真是恰到好处。如果不用借代,而是

写成类似“人间四月花开尽”之类的句子,则不但犯了重字之忌,还会弄得全诗索然寡味。 二、巧用借代,严守诗词格律 苏轼《江城子·密州出猎》中有“左牵黄,右擎苍”之句。词中的“黄”和“苍”本来是分别指黄犬和苍鹰的颜色,这里是用“黄”代指黄犬,用“苍”代指苍鹰。显然,词句如果不用借代,而是将其写成“左牵黄犬,右擎苍鹰”之类的句子,不仅大煞风景,还严重违背了词牌的要求。因为,“江城子”这个词牌要求所填之词第二句和第三句必须都是三个字,而且平仄排列必须是“仄平平,仄平平”,显然“左牵黄犬,右擎苍鹰”的写法根本不合格律要求。写成“左牵犬,右擎鹰”又会如何呢?显然,这样写虽然没有破坏词牌对字数的要求,但根本不合押韵的规则。因此,无论从表达手段还是从韵律要求角度看,以上两种假设都不如以颜色借代进行表述来得更妙。此外,以“黄”和“苍”入词,还直接给黄犬和苍鹰这两个意象着上了鲜明的色彩,进而突出了其形象特征,使整首词更加有了意境美。毋庸置疑,苏轼借“黄”代“犬”,借“苍”代“鹰”,不仅严守了词的格律,而且还使词句更加生动形象了。“左牵黄,右擎苍”真可谓不可多得的神来之笔。 三、巧用借代,使表达更加委婉含蓄 白居易在《长恨歌》 里为什么不直接写唐明皇好色而是要借“汉皇”言之呢?这是因为李隆基是诗人的前朝皇帝,其不能违背“为尊者讳”“为长者讳”

whatever的用法与分析

whatever的用法 Whatever有两个用法,一是引导名词性从句(如主语从句、宾语从句、表语从句),二是用于引导让步状语从句. 1.用于引导名词性从句 Whatever she did was right.她做的一切都是对的. Whatever she did was right.她做的一切都是对的. I will do whatever you wish.我可做任何你想我做的事. Give them whatever they desire.他们想要什么就给他们什么. Whatever I have is at your service.我所有的一切都由你使用. You may do whatever you want to do.无论你想做什么事,你都可以做. I’ll just say whatever comes into my head.一我想到什么就说什么. One should stick to whatever one has begun.开始了的事就要坚持下去. She would tell him whatever news she got.她得到的任何消息都会告诉他. I’m going to learn whatever my tutor wishes.我将学习任何我的导师愿意我学的东西. College students are seen doing whatever work they can find.我们可以看到,只要有工作,大学生们什么都干. Do whatever she tells you and you'll have peace.她叫你干什么你就干什么,那你就太平了. 2.用于引导让步状语从句 Whatever we said,he'd disagree.无论我们说什么,他都不同意. Whatever happened I must be calm.不管发生什么情况我都要镇静. We’ll go along together whatever happens.不管发生什么情况我们都要起干. Don’t lose heart whatever difficulties you meet.不管遇到什么困难都不要灰心. Whatever you do,I won't tell you my secret.不管你做什么,我都不会把我的秘密告诉你. Whatever happens,we'll meet here tonight.不管发生什么事情,我们今晚都在这儿碰头. Whatever happens,the first important thing is to keep cool.不管发生什么事,头等重要的是保持冷静. 【注意1】 whatever还可用于加强语气,相当于what ever,what on earth等.如: Whatever is the matter?这是怎么回事? Whatever does he mean? 【注意2】 Whatever从句有时可以省略.如: Whatever your argument,I shall hold to my decision.不管你怎样争辩,我还是坚持自己的决定.

小学生“的、地、得”用法口诀、用法分析、用法练习(后附答案)

小学生“的、地、得”用法口诀、用法分析、用法练习(后附答案) “的、地、得”口诀儿歌 的地得,不一样,用法分别记心上, 左边白,右边勺,名词跟在后面跑。 美丽的花儿绽笑脸,青青的草儿弯下腰, 清清的河水向东流,蓝蓝的天上白云飘, 暖暖的风儿轻轻吹,绿绿的树叶把头摇, 小小的鱼儿水中游,红红的太阳当空照, 左边土,右边也,地字站在动词前, 认真地做操不马虎,专心地上课不大意, 大声地朗读不害羞,从容地走路不着急, 痛快地玩耍来放松,用心地思考解难题, 勤奋地学习要积极,辛勤地劳动花力气, 左边两人双人得,形容词前要用得, 兔子兔子跑得快,乌龟乌龟爬得慢, 青青竹子长得快,参天大树长得慢, 清晨锻炼起得早,加班加点睡得晚, 欢乐时光过得快,考试题目出得难。 一、的、地、得用法分析:

“的”后面跟的都是表示事物名称的词或词语,如:敬爱的总理、慈祥的老人、戴帽子的男孩、珍贵的教科书、鸟的天堂、伟大的祖国、有趣的情节、优雅的环境、可疑的情况、团结友爱的集体、他的妈妈、可爱的花儿、谁的橡皮、清清的河水...... “地”后面跟的都是表示动作的词或词语,如:高声地喊、愉快地唱、拼命地逃、疯狂地咒骂、严密地注视、一次又一次地握手、迅速地包围、沙沙地直响、斩钉截铁地说、从容不迫地申述、用力地踢、仔细地看、开心地笑笑......” “得”前面多数是表示动作的词或词语,少数是形容词;后面跟的都是形容事物状态的词或词语,表示怎么怎么样的,如:走得很快、踩得稀烂、疼得直叫唤、瘦得皮包骨头、红得发紫、气得双脚直跳、理解得十分深刻、乐得合不拢嘴、惊讶得目瞪口呆、大得很、扫得真干净、笑得多甜啊...... 二、的、地、得用法补充说明: 1、如果“de”的后面是“很、真、太”等这些词,十有八九用“得”。 2、有一种情况,如“他高兴得一蹦三尺高”这句话里,后面的“一蹦三尺高”虽然是表示动作的,但是它是来形容“高兴”的程度的,所以也应该用“得”。 三、的、地、得用法总结:

“了”的用法分析

“了”的用法分析 (一)“了1”、“了2”的出现顺序问题现代汉语的“了”,一般认为可以分成两个“了”。一是用于动词后表示完成体的“了1”,一是用于句尾表示情状改变的“了2”;。 1、动态助词“了1”的功能和用法动态助词“了1”用在动词后表示动作完成或实现。注意 : 1)“了 1”虽然表示完成,但受使用环境及说话人主观意志等因素的影响,有时完成也不用“了1”。在下列情况之下不能使用“了1”。a、多次性,反复性经常性(即还在进行的动词,到发出的动作是过去发生的)动作行为后不可。如:*他从上大学开始, 一直学了汉语。* 我每年都在上海过了很长时间。b、不表示具体动作,没有完成意义的动词不可。如:* 现在他很想念了陆地上的生活。* 我去年就盼望了来北京。* 刚开始在北京生活,我感觉了很难。“想念”、“盼望”、“感觉”都是表示人的一种带有经常性或持久性的精神状态,不是一般的行为动作动词,后边不应该带动态助词“了1”。c、带宾语从句的动词后不可。如:*在很小的时候, 我就发现了我很喜欢中国。* 我发誓了我一定要学好汉语。* 我决定了暑假去旅游。句中“发现”、“决定”、“发誓”等后面都带了小句宾语。按照汉语的规则,带小句宾语的动词后面不能用助词“了1”。 tob_id_5128 d、兼语句中前一动词后不可。如:* 他请求了我原谅他。* 去年公司派了我去上海出差。* 我们都劝了她不要再等了。e、连动句中后一动词表示前一动词的目的时,前一动词后不可。如:* 昨天朋友来了看望我。* 他去了火车站买票。* 我们已经想了办法解决这个问题。f、前一动作是后一动作的行为方式时前一动词后不应该用“了1”。如:* 老师笑了介绍自己。* 他指了墙上的照片告诉我们,那就是他爸爸。前一动作是后一动作的伴随状态,并不表示前一动作结束后再出现后一动作,这时应该用“着”而不用“了1”。g、否定副词”没”和”了1”不同现,即“没+动词+了”是错误的。如:* 早上我没吃饭了. * 过去我没去过了上海。但如果否定副词“没有”前面如出现表示时间段的词语,即“时间段+没+动词+了”则是正确的。如: 我三天没吃饭了。 他一个星期没来上课了。这是因为句中的“了”实际上是语气词“了2”,是说“没吃饭”和“没来上课”这种状态持续三天了、一个星期了。其中“了”不是和动词直接联系在一起的,而是和时间段联系在一起的。同时,我们还应该注意“没(有)+名词+了”也是正确的。如:我没钱了。瓶子里没水了。这是因为句中的“没(有)”是动词而不是否定副词,句尾的“了”是语气词“了2”,而不是动态助词“了1”。

标点符号的正确用法分析

写论文网标点符号的正确用法公文常见标点符号用法正文 导航 公文常见标点符号用法 字号:大中小 公务活动中易用错读错的标点和字词 一、公文中易误用的标点 1.在题序后面误用顿号。 例如:第一、第二、首先、其次、等等,顿号(、)应改为逗号(,)。 (一)、(二)、(三)、(1)、(2)、(3)、①、②、③、等等,这些序号既然用了括号,就不能再加顿号及其他标点。 1、2、3、A、B、C、a、b、c、等等,阿拉伯数字和拉丁字母作序号时后面不用顿号,应该用下脚圆点号“.”(只有中文数字序号后面才使用顿号如“一、二、三、等”)。 2.冒号“:” 误为比号“︰”。 3.破折号误为两个一字线“——”或一个化学单键号“—”,破折号应为“——”。把“——”改为“——”的方法是:将其刷黑再选择成黑体,两个一字线就连在一起了。 4.表示数量范围的数字之间误用了一字线“—”或半字线“-”,应该用浪纹线“~”,如11月1日~11月5日,2~3天,20~30人,等等。浪纹线“~”可在插入菜单中的特殊符号里查找,也可在新罗马字体下按Shift+~。 5.省略号(……)误用为(……),省略号形状按规定应该为六个连点,还有在省略号前后保留了顿号、逗号、分号的也不对。 如:雄伟庄严的人民大会堂,是首都最著名的建筑之一,……。(省略号前后的标点符号应该删去) 6.阿拉伯数字表示时间时,小时与分钟之间应当使用英文冒号,如6:00、23:00,不能使用中文冒号,如6:00、23:00,也不能用比号(︰)。(中文冒号:)(比号︰)(英文冒号:) 7.公文的编号应该用“〔〕”不能用“[]”,如渝教语〔2008〕3号。 二、公文中易误用的数字 1.二〇〇六年不能写成二00六年、二○○六年、二零零六年,应在插入菜单里面的“日期和时间”里添加。 2. 表示概数使用了错误的形式,如3、4天,7、8个人,等等。表述这样的概数应该使用中文数字,并且数字之间不使用标点,如:一两天,三四天,七八个人,等等。 三、公文中易用错的字(黑体字是正确的,括号里的字是错误的) 安(按)装濒bīn(频)临部(布)署 检察(查)院惊诧(咤)精粹(萃)

常用虚词用法分析:者

常用虚词用法分析:者 本文是关于常用虚词用法分析:者,感谢您的阅读! 常用虚词用法分析:者 是文言文中最常见的虚词,常用作结构助词和语气词。 一、用作助词 1.用在动词、形容词或动宾词组之后,组成名词性的“者”字结构,有指代作用。相当于“……的人”、“……的事物”。例如:(1)此不为远者小而近者大乎?(《两小儿辩日》)——这不是离我们远的东西看着就小,离我们近的东西看着就大吗? (2)负者歌于途,行者休于树。(《醉翁亭记》)——背着东西的人在路上唱歌,徒步行走的人在树下休息。 2.“者”跟它前面的词语组成比况性结构,用在句末,表示相似于某种状况,常与“若”、”似”配合使用,相当于“象……样子”。“象……似的”。例如:(1)然往来视之,觉无异能者。(《黔之驴》)——但是(老虎)来回观察毛驴,觉得(毛驴)象没有什么特殊本领似的。 (2)言之,貌若甚戚者。(《捕蛇者说》)——(他说着这些话,脸上好象很悲伤的样子。 3、用在数词的后面,一般指几种人或事物。例如:嗟夫!予尝求古仁人之心,或异二者之为。(《岳阳楼记》)——唉!我曾经探求过古代仁人的心理,也许不同于以上两种人的心理活动。 二、用作语气词 1.用在判断句中的主语之后,表示提顿或判断。例如:陈胜者,

阳城人也。(《陈涉世家》)——陈胜是阳城人。 2.用在叙述句或描写句的主语之后,表示提顿。有时:语前加一“有”字,形成“有……者”的格式。一般可不译也可译为“的”。例如: (1)北山愚公者,年且九十。(《愚公移山》)——北山愚公年纪将近九十岁。 (2)有蒋氏者,专其利三世矣。(《捕蛇者说》)——有(个)姓蒋的独享那(捕蛇的)利益三代了。 3.用在因果复句的前一分句句末,把结果或现象提示出来,后一分句申述原因或理由。例如:(1)然而不胜者,是天时不如地利也。(《孟子》)二章)——(虽然如此),但是却不能取胜,这是因为占有天时不如占有地利(更重要)。 (2)不以木为之者,文理有疏密,沾水则高下不平。(《活板》)——不用木料做字模,是因为木料的纹理有疏密,沾上水就高低不平了。 感谢您的阅读,本文如对您有帮助,可下载编辑,谢谢

是的用法分析

是的用法分析 Company Document number:WTUT-WT88Y-W8BBGB-BWYTT-19998

“是”的用法分析 序言 “是”的一些用法在古代有,但是现代已经不用或使用频率很低,还有些现代才出现,古时候没有。现代汉语中“是”在书面语和口语中出现的频率也是比较高的,但目前相关研究有的从“是”的词性分析有的从语法成份方面分析。为了尽量全面深入的了解并应用“是”,从而正确熟练的使用,使我们所学理论更好的联系实际应用,所以有必要对“是”的用法进行分析。 第一章:“是”的词性分析 汉语中,词性往往决定了一个字或词的用法与含义。所以我们首先从词性角度对“是”进行研究,从而分析它的用法。 一:“是”作形容词。 (一):表示对的,正确的。例如: 1:陶渊明《归去来兮辞》中:“实迷途其未远,觉今是而昨非”。(实在是误入迷途还不算太远,已经觉悟到现在是对的而过去是错的。) 2:斗争历史短的, 可以因其短而不负责; 斗争历史长的, 可以因其长而自以为是。对于诸如此类的东西, 如果没有自觉性, 那它们就会成为负担或包袱。(《毛泽东选集》第901页) (二):表示概括,凡是,任何。比如: 1:“是个有良知的人都会这么做”。 2:“是学生就要用心学习。” 二:“是”作代词。 表示此这。例如 1:林嗣环《口技》中“当是时,妇手拍儿声,口中呜声,儿含乳啼声,大儿初醒声,夫叱大儿声,一时齐发,众妙毕备”(这时候,妇人用手拍孩子的声音,口中呜呜哼唱的声音,小孩子含着乳头啼哭的声音,大孩刚刚醒来的声音,丈夫大声呵斥大孩子的声音,同时都响了起来,各种声音都表演得惟妙惟肖)。中的是可以解释为此或这的意思。 2:明朝张岱的代表作《湖心亭看雪》中:“是日更定,余拿一小舟,拥毳衣炉火,独往湖心亭看雪。”(这一天初更以后,我乘着一只小船,穿着毛皮衣,带着火炉,独自前往湖心亭欣赏雪景。) 三:“是”作名词。 (一):表示特定组织的事物或业务。比如范晔的《后汉书桓谭冯衍列传》中“君臣不合,则国是无从定矣”。 “国事”与“国是”是近义同音词,二者都是名词,都指国家的政务、政事。但二者同中有异: 1:词义范围不同,“国事”既可以指对国家有重大影响的事情,也可以指一般的国家事务;而“国是”则专指国家决策、规划等重大事务。

“是”的用法分析

“就是”得用法分析 序言 “就是”得一些用法在古代有,但就是现代已经不用或使用频率很低,还有些现代才出现,古时候没有。现代汉语中“就是"在书面语与口语中出现得频率也就是比较高得,但目前相关研究有得从“就是”得词性分析有得从语法成份方面分析.为了尽量全面深入得了解并应用“就是”,从而正确熟练得使用,使我们所学理论更好得联系实际应用,所以有必要对“就是”得用法进行分析。 第一章:“就是”得词性分析 汉语中,词性往往决定了一个字或词得用法与含义.所以我们首先从词性角度对“就是”进行研究,从而分析它得用法。 一:“就是”作形容词. (一):表示对得,正确得.例如: 1:陶渊明《归去来兮辞》中:“实迷途其未远,觉今就是而昨非"。( 实在就是误入迷途还不算太远,已经觉悟到现在就是对得而过去就是错得。) 2:斗争历史短得,可以因其短而不负责;斗争历史长得,可以因其长而自以为就是。对于诸如此类得东西,如果没有自觉性,那它们就会成为负担或包袱。(《毛泽东选集》第901页) (二):表示概括,凡就是,任何。比如: 1:“就是个有良知得人都会这么做”。 2:“就是学生就要用心学习。" 二:“就是"作代词. 表示此这。例如 1:林嗣环《口技》中“当就是时,妇手拍儿声,口中呜声,儿含乳啼声,大儿初醒声,夫叱大儿声,一时齐发,众妙毕备”(这时候,妇人用手拍孩子得声音,口中呜呜哼唱得声音,小孩子含着乳头啼哭得声音,大孩刚刚醒来得声音,丈夫大声呵斥大孩子得声音,同时都响了起来,各种声音都表演得惟妙惟肖)。中得就是可以解释为此或这得意思. 2:明朝张岱得代表作《湖心亭瞧雪》中:“就是日更定,余拿一小舟,拥毳衣炉火,独往湖心亭瞧雪。"(这一天初更以后,我乘着一只小船,穿着毛皮衣,带着火炉,独自前往湖心亭欣赏雪景.) 三:“就是”作名词。 (一):表示特定组织得事物或业务。比如范晔得《后汉书?桓谭冯衍列传》中“君臣不合,则国就是无从定矣”. “国事”与“国就是"就是近义同音词,二者都就是名词,都指国家得政务、政事.但二者同中有异: 1:词义范围不同,“国事”既可以指对国家有重大影响得事情,也可以指一般得国家事务;而“国就是"则专指国家决策、规划等重大事务。 2:适用对象不同,“国事”可用于国内,也可用于国际,如“国事访问"就是一国首脑接受她国邀请所作得正式访问;“国就是”所指得国家大事则严格限用于国人在中央所议之国家大事。在我国,人民代表大会就是人民行使国家权力得机构,全国人大代表到北京参加全国人民代表大会就就是“共商国就是"。 3:语体色彩不同,“国事”就是颇具口语色彩得词,“国就是"就是用于书面语得文言词。明黄道周《节寰袁公传》:“疏上,夺俸一年。呜呼!国就是所归,往往如此矣.” 4:语法功能不同,作为名词,二者都能作主语、宾语,但“国事"还能作定语,如“国事访问”;而“国就是”就无此用法。 所以在使用得时候要注意区分二者差异. (二)表姓氏。就是姓.齐大夫之后。本氏姓,后改,见三国吴志就是仪传.又,汉有就是盛、就是迁,见隶释.南北朝时,鲜卑族代北复姓就是奴氏、就是云氏,皆改为汉姓就是氏。

Or和and的用法 解析

Or和and的用法 一、连词or主要用法分述如下: 1、用在选择疑问句中连结被选择的对象,意为“或者,还是”。例如: Is he a doctor or a teacher? 他是医生还是教师? Did you do your homework or watch TV last night? 你昨晚做作业还是看电视了? Are they singing or reading English? 他们是在唱歌还是在读英语? 下列两个疑问句中的并列成份由于使用了不同的连词,因而句式有所不同。试比较: A、Does he like milk and bread? 他喜欢牛奶或者面包吗? B、Does he like milk or bread? 他喜欢牛奶还是面包? 分析:A 句中使用了连词and,是一般疑问句,对其作肯定或否定回答应用:Yes, he does. No, he doesn't. B句中使用了并列连词or,因而是选择疑问句,对其回答

不用“yes”或“no”,而应根据实际情况直接选择回答:He likes milk.或:He likes bread. 2、用于否定句中连结并列成分,表示“和,与”之意。例如: There isn't any air or water on the moon.月球上既没有空气也没有水。 The baby is too young. He can't speak or walk.那婴儿太小,他不会说话,也不会走路。 He hasn't got any brothers or sisters.他没有兄弟和姐妹。 肯定句中并列连词应用and,在把含有and的肯定句改为否定句时,莫忘把连词and改为or。例如: The students sang and danced in the park yesterday. →The students didn't sing or dance in the park yesterday. 3、用于句型“祈使句+or+陈述句”中,表示在以祈使句为条件下的相反假设,意为“否则,要不然”。例如:

虚词“了”的用法分析

现代汉语结课论文 题目:虚词“了”的用法分析姓名:周永乐 学号:2013504059 院系:文学艺术学院中文系 专业:汉语言文学 班级:2013级3班 指导老师:余静

虚词“了”的用法分析 周永乐 (石河子大学文学艺术学院中文系 2013级汉语言文学3班) 摘要:现代汉语中,虚词“了(le)”不论是在口语中,还是书面语中,使用频 率都比较高。虚词“了”有两个,语气词“了”和助词“了”。两者字形、读音相同,但具体用法和语法作用却不相同。 关键字: 虚词“了”、语气词、助词、具体用法、语法作用 正文: 注意:语气词“了”和助词“了”可同在句末。且都在句子末尾,可能是助词“了”,也有可能是语气词“了”,但意思有区别。 如:她写了。(“了”若是语气词,则表示动作在进行,若“了”是助词,则表示动作已经完成) 一、助词“了”。 1.紧跟在动词之后,表示动作的完成。 如:1)王春生从来没有忘了他爹的惨死跟妈的眼泪。(周立波《暴风骤雨》) 1《谈谈句末的“了”》张兰英-《东岳丛林》-2005

2)还没有等到发榜,全国高校统考开始了,我当然还应该参加。(余秋雨《霜冷长河》) 也可以表示将要发生的事情或假设可能发生的事情的完成。如:跟他们谈话就是我的工作,你要有什么话等我闲了再谈吧。(《赵树理选集》) 2.如果动词之后紧跟着另外一个动词或形容词作补语时,“了”就放在了补语之后。 如:1) "祥哥!"她往前凑了凑,"我把东西都收拾好了。"(老舍《骆驼祥子》) 2)他决定去拉车,就拉车去了。(老舍《骆驼祥子》) 3) 整整的三年,他凑足了一百块钱!(老舍《骆驼祥子》) 3. “了”放在由两个动词构成的并列词组后面(表示两个动词同时或者连续完成)。 如:这项政策的实施进一步巩固和加强了海内外中华儿女大团结。 4. 连谓句、兼语句中,助词“了”一般用在后一动词之后2。如:她找我借了两本书。连谓句强调前一动作完成后才开始后一动作时,兼语句前一动作完成时,助词“了”可在前一动词后。如:临时组织了一些人去支援五车间。 5. 有些动词后面的助词“了”表示动作有了结果,即加在动词后面的“掉”很相似。这类动词有:泼、扔、放、碰、砸、捧、磕、撞、踩、伤、杀、宰、切、冲、卖、还、毁、忘、丢、关、喝、吃、咽、2吕叔湘《现代汉语八百词》(1981商务印书馆)第315页。

“的、地、得”用法分析及练习(后附答案)解读

“的、地、得”用法分析及练习(后附答案 一、的、地、得用法分析: “的” 后面跟的都是表示事物名称的词或词语, 如:敬爱的总理、慈祥的老人、戴帽子的男孩、珍贵的教科书、鸟的天堂、伟大的祖国、有趣的情节、优雅的环境、可疑的情况、团结友爱的集体、他的妈妈、可爱的花儿、谁的橡皮、清清的河水 ...... “地”后面跟的都是表示动作的词或词语,如:高声地喊、愉快地唱、拼命地逃、疯狂地咒骂、严密地注视、一次又一次地握手、迅速地包围、沙沙地直响、斩钉截铁地说、从容不迫地申述、用力地踢、仔细地看、开心地笑笑...... ” “得”前面多数是表示动作的词或词语,少数是形容词;后面跟的都是形容事物状态的词或词语, 表示怎么怎么样的, 如:走得很快、踩得稀烂、疼得直叫唤、瘦得皮包骨头、红得发紫、气得双脚直跳、理解得十分深刻、乐得合不拢嘴、惊讶得目瞪口呆、大得很、扫得真干净、笑得多甜啊 ...... 二、的、地、得用法补充说明 : 1、如果“ de ”的后面是“很、真、太”等这些词,十有八九用“得” 。 2、有一种情况,如“他高兴得一蹦三尺高”这句话里,后面的“一蹦三尺高”虽然是表示动作的,但是它是来形容“高兴”的程度的,所以也应该用“得” 。 三、的、地、得用法总结: 1、“的”前面的词语一般用来修饰、限制“的”后面的事物,说明“的”后面的事物怎么样。结构形式一般为:修饰、限制的词语 +的 +名词。 2、“地” 前面的词语一般用来形容“地” 后面的动作, 说明“地” 后面的动作怎么样。结构方式一般为:修饰、限制的词语 +地 +动词。 3、“得” 后面的词语一般

用来补充说明“得” 前面的动作怎么样, 结构形式一般为:动词(形容词 +得 +补充、说明的词语。 四、的、地、得用法例句: 1. 蔚蓝色的海洋,波涛汹涌,无边无际。 2. 向日葵在微风中向我们轻轻地点头微笑。 3. 小明在海安儿童公园玩得很开心。 五、“的、地、得”的读音: “的、地、得”是现代汉语中高频度使用的三个结构助词,都起着连接作用; 它们在普通话中都各自有着各自的不同的读音, 但当他们附着在词,短语,句子的前面或后面,表示结构关系或某些附加意义的时候都读轻声“ de ” ,没有语音上的区别。 但在书面语中有必要写成三个不同的字, 这样可以区分他们在书面语用法上的不同。这样做的好处,就是可使书面语言精确化。 【练习】 一、请你正确填写“ 的、地、得” 。 1、清晨,可爱(多多兴高采烈(来到金灿灿(葵花园。她兴奋(东瞧瞧,西看看,一会儿轻轻(摸摸, 一会儿细细(闻闻,情不自禁(翩翩起舞。 2、呀!怎么变成红色(天啦?明明兴奋(手舞足蹈,高兴(跳起来。他情不自禁(大喊:“ 我要飞! ” 3、机灵 ( 猴子在宁静 ( 湖边尽情 ( 玩耍, 它高兴 ( 忘了回家 . 4、小明(心情好(不得了,他(嘴里哼着歌,脸上挂着甜甜(微笑。