Self Image and Frequent Alcohol Use in Middle Adolescence

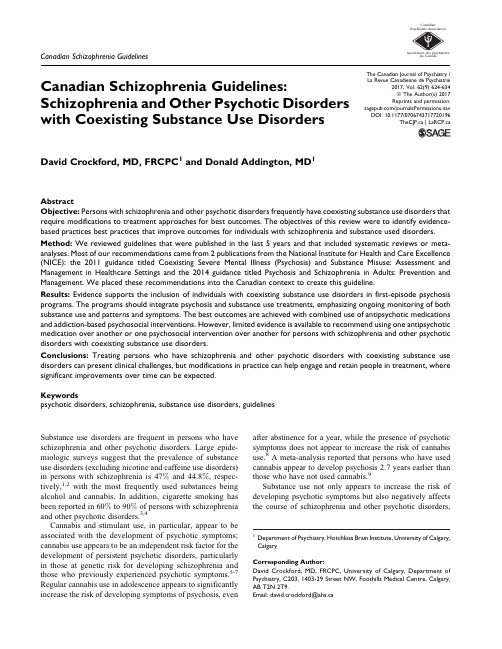

2017版加拿大精神分裂症指南

Abstract Objective: Persons with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders frequently have coexisting substance use disorders that require modifications to treatment approaches for best outcomes. The objectives of this review were to identify evidencebased practices best practices that improve outcomes for individuals with schizophrenia and substance used disorders. Method: We reviewed guidelines that were published in the last 5 years and that included systematic reviews or metaanalyses. Most of our recommendations came from 2 publications from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE): the 2011 guidance titled Coexisting Severe Mental Illness (Psychosis) and Substance Misuse: Assessment and Management in Healthcare Settings and the 2014 guidance titled Psychosis and Schizophrenia in Adults: Prevention and Management. We placed these recommendations into the Canadian context to create this guideline. Results: Evidence supports the inclusion of individuals with coexisting substance use disorders in first-episode psychosis programs. The programs should integrate psychosis and substance use treatments, emphasizing ongoing monitoring of both substance use and patterns and symptoms. The best outcomes are achieved with combined use of antipsychotic medications and addiction-based psychosocial interventions. However, limited evidence is available to recommend using one antipsychotic medication over another or one psychosocial intervention over another for persons with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders with coexisting substance use disorders. Conclusions: Treating persons who have schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders with coexisting substance use disorders can present clinical challenges, but modifications in practice can help engage and retain people in treatment, where significant improvements over time can be expected. Keywords psychotic disorders, schizophrenia, substance use disorders, guidelines

关于急救知识的简短的英文资料

关于急救知识的简短的英文资料1. 关于“急救学问”的英语作文范例指望可以帮到你,便利你更好的理解,也顺便附上相关的译文,要记得接受哦Frist aidIt is important for you to learn some knowledge about first aid in your daily life. If a person has an accident, he needs medical care before a doctor can befound. When you give first aid, you must pay attention to three things. First, when a person stops breathing, open his/her mouth and see if there is food at the bulk of his/her mouth. Second, if a person cannot breathe, do you best to start his/her breathing急救在日常生活中,学习一些急救学问,对一个人来说很重要。

假如一个人发生车祸,在医生到来之前,需要对他进行医疗护理,做急救时,应留意以下二点。

首先,假如他住手了呼吸,掰开他的嘴巴看看喉咙口有无食物。

其次,假如他不能呼吸,就实行人工呼吸的方法,尽快使他开头呼吸。

再其次,假如他伤的很重,应即将止血,然后送往医院。

假如他失血过多,达三分之一,那末他有可能会死。

很多不测大事也有可能在家里发生。

于是,家长们应把握一些急救常识,以便对付一些发生在孩子身上的大事。

假如孩子被动物咬伤,先用自来水冲洗伤口,然后送去看医生。

假如孩子被烫伤,先用自来水冲洗,降温,然后用一块洁净的干布盖住伤口。

假如烫伤很严峻,应去看医生。

假如割伤了手指,应先将伤口处理洁净,然后用一块纸包扎伤口。

英语保持身体健康的谚语

英语保持身体健康的谚语导读:本文是关于英语保持身体健康的谚语,如果觉得很不错,欢迎点评和分享!1、若要身体壮,饭菜嚼成浆。

If you want to be strong, chew the food into pulp.2、宁可锅中存放,不让肚子饱胀。

It's better to store it in a pot than to have a full stomach.3、娱乐有制,失制则精疲力竭。

Entertainment is institutionalized, but failure is exhausting.4、春捂秋冻,不生杂病。

Spring covers autumn frozen, no miscellaneous diseases.5、三餐不过饱,无病活到老。

Three meals are not enough, and you live to old age without illness.6、晚上少吃一口,肚里舒服一宿。

Eat less in the evening and have a comfortable night in your stomach.7、乐靠自得,趣靠自寻。

Joy depends on self-satisfaction, fun depends on self-seeking.8、冬不蒙首,春不露背。

Winter does not cover the head, spring does not reveal the back.9、哭一哭,解千愁。

Cry, relieve a thousand sorrows.10、心灵手巧,动指健脑。

Hand and soul, finger and brain.11、蔬菜是个宝,餐餐不可少。

Vegetables are a treasure and meals are indispensable.12、戒烟限酒,健康长久。

心理表现

Motivation and Emotion,Vol.25,No.1,2001(c 2001)Maintaining One’s Self-Image Vis-`a-Vis Others:The Role of Self-Affirmation in the Social Evaluation of the SelfSteven J.Spencer,1,3Steven Fein,2,3and Christine D.Lomore1Three studies examined how people maintain their self-images when they face threat to interpersonal aspects of the self.In Studies1and2,we found evidence that low self-esteem people lower their estimates of their performance when they expect immediate feedback in order to protect themselves from the interpersonal threat inherent in such feedback,and that self-affirmation reduces this tendency among low self-esteem people.In Study3,we found that when people are self-affirmed they are more likely to engage in upward social comparisons and less likely to engage in downward social comparisons.Together thesefindings suggest that people can cope with threats to interpersonal aspects of the self by affirming other important aspects of the self.The self,as that which can be an object to itself,is essentially a social structure,and it arisesout of social experience.Mead(1934,p.140)...the emotion that beckons me on is indubitably the pursuit of an ideal social self,a self thatis at least worthy of approving recognition by the highest possible judging companion...James(1910,p.46)As these quotes illustrate,the social nature of the self-concept has long been recognized.In particular they point to the reciprocal perceptions of self and others as playing a crucial role in the self-concept.Mead notes that we often form and manage our self-images by interacting with others.That is,how others view us 1Department of Psychology,University of Waterloo,Waterloo,Ontario,Canada.2Department of Psychology,Bronfman Science Center,Williams College,Williamstown, Massachusetts.3Address all correspondence to Steven Spencer,Department of Psychology,University of Waterloo, 200University Avenue,Waterloo,Ontario,Canada N2L3G1;e-mail:sspencer@watarts.uwaterloo.ca. Or to Steven Fein,Department of Psychology,Bronfman Science Center,Williams College, Williamstown,Massachusetts01267;e-mail:steven.fein@.410146-7239/01/0300-0041$19.50/0C 2001Plenum Publishing Corporation42Spencer,Fein,and Lomore influences our perception of ourselves.James notes that we care about how we stand in relation to others.That is,how we view others shapes our views of ourselves. We argue that this dynamic interplay between how we view others and how they view us(or how we think they view us),what we are calling the self vis-`a-vis others,is a fundamental part of self-image maintenance.There is a renewed emphasis in social psychology on this interpersonal nature of the self-concept.Baumeister and Leary(1995)argue that the desire to belong and be accepted by others is the strongest,most central human motivation.Research in a variety of literatures,such as on attachment theory(Bartholomew&Horowitz, 1991;Davila,Burge,&Hammen,1997;Hazan&Shaver,1987),interpersonal relationships(Baldwin&Holmes,1987;Berscheid&Reis,1988;Collins&Miller, 1994;Holmes,2000;Murray&Holmes,1993),and culture(Heine&Lehman, 1997;Kashima,Yamaguchi,Kim,Choi,Gelfand,&Masaki,1995;Kitayama& Markus,1999;Lee,Aaker,&Gardner,2000;Markus&Kitayama,1991),has highlighted the important role of others in the self-concept.Because the self-concept depends to such a large extent on these self-other perceptions,concerns about failures in this interpersonal aspect of the self can be particularly threatening to individuals,particularly in Western,individualistic cultures.Since James’s seminal work,the literature on the self-concept is replete with examples of how the self responds in defensive,biased ways to try to protect the self against such threats.For example,people may try to avoid or render ambiguous potentially important feedback about their performance on a task if they have reason to worry that this feedback could be threatening to the self vis-`a-vis others,they may present themselves in self-deprecating ways in hopes of avoiding the embarrassment of appearing to fail in front of others,or they may focus on downward rather than lateral or upward social comparison targets in order to salve a threatened self-image(e.g.,Baumeister,1998;Ferrari,1991;Festinger, 1954;Shepperd,1993;Shepperd&Arkin,1989;Taylor,Wood,&Lichtman,1983; Wills,1981,1991).In all of these examples,the individual may protect against an acute threat to the self-image,but perhaps at the cost of losing potentially valuable information for self-insight,improvement,or promotion.What has not been examined as extensively in previous research is how these interpersonal aspects of the self-concept work together with other important aspects of the self(e.g.,values,attitudes,and interests)in shaping people’s self-evaluations. In our earlier work(Fein&Spencer,1997)we demonstrated that people can use how they see the self vis-`a-vis others to cope with a threat to another important aspect of their self-image.More specifically,we found that when people made neg-ative evaluations of a stereotyped target,these evaluations restored their threatened self-image.For example,individuals who experienced a threat to their self-image in academics(i.e.,when they received negative feedback on an intelligence test) used their evaluations of others(i.e.,negative evaluations of members of a stereo-typed group)to feel better about themselves and restore a positive self-image.InSelf-Affirmation and Self-Image Vis-`a-Vis Others43 the present research we examine the converse:Can people use other important self-image resources to cope with threats to their self vis-`a-vis others?Self-affirmation theory(Steele,1988)proposes that when people experi-ence a self-image threat,they can respond to this threat by recruiting other self-resources—even ones that are unrelated to the threatened aspects of the self—to maintain an overall image of themselves as moral and capable.In the present research we extend this reasoning to test the hypothesis that people can buffer themselves from threats to their self-image vis-`a-vis others by recruiting or think-ing about other important aspects of their self-image.That is,although threats to one’s self-image vis-`a-vis others can be so onerous because of the important role of interpersonal dynamics in the self-concept,affirming other aspects of the self may ameliorate the impact of such threats,thereby enabling individuals to respond in less defensive,self-protective ways.We examine this issue in two ways.Thefirst pair of studies was designed to investigate how self-affirmation affects individuals’concern with self-presentation. In particular,we drew on research by Baumeister and his colleagues(Baumeister, 1998;Baumeister,Tice,&Hutton,1989)that found that people with low self-esteem respond to self-presentational concerns by engaging in self-protection.In Study1we replicated this phenomenon in our lab and in Study2we tested the question of whether self-affirmation can reduce the tendency toward self-protection that people with low self-esteem typically exhibit.Study3extended this research to examine a situation in which people in general,regardless of their trait levels of self-esteem,would respond in a self-protective manner,and we tested whether self-affirmation would reduce their need for self-protection,thereby freeing them to respond in ways that might promote rather than simply protect the self.More specifically,this study concerned how individuals use social comparisons as a means of shaping their own self-image. Comparing with someone who is doing better than oneself can be more threatening to the self than comparing with someone who seems inferior(Brickman&Bullman, 1977;Lockwood&Kunda,1997;Taylor&Lobel,1989;Wills,1981).Study3 tested the hypotheses that(1)when people experience a self-image threat,they are more likely to avoid such upward comparisons and instead seek comparisons with others who are doing worse than themselves,and(2)self-affirmation can reduce this tendency toward downward social comparison in the face of threat.STUDIES1AND2In this pair of studies we sought to replicate and extend previous research demonstrating that people with low self-esteem are likely to self-present in a more self-protective or deprecating manner than are people with high self-esteem, whose self-presentational style is likely to be more self-enhancing or aggrandizing44Spencer,Fein,and Lomore (see Baumeister,1998,and Baumeister et al.,1989for reviews).Various studies have shown,for example,that people with low self-esteem are less likely to take risks(Josephs,Larrick,Steele,&Nisbett,1992),are more concerned with their self-presentation(Baumeister,1982),and are less likely to report self-enhancement motivations(Wood,Giordano-Beech,Taylor,Michela,&Gaus,1994)than are their high self-esteem counterparts.Particularly relevant for the current studies is an experiment conducted by Shrauger(1972).Participants with either high or low self-esteem completed a task and estimated their performance.They completed this task either in front of an audience or without an audience.Although there was no difference between high-and low-self esteem participants in their actual performance,those with low self-esteem reported lower estimates of their performance than did the high self-esteem participants—but this difference emerged only in the presence of an audience.This pattern of results suggests that low self-esteem people may underestimate their performance when they are concerned about protecting themselves from how they are viewed by others.Study1was designed to replicate thisfinding and provide a further test of whether low self-esteem people underestimate their performance out of self-presentation concerns.Study2was designed to test whether self-affirmation could provide a buffer against these self-presentation concerns and enable people with low self-esteem to adopt the bolder,more ambitious self-judgment that is more characteristic of people with high self-esteem.Study1In Study1,participants with either high or low self-esteem completed a dif-ficult intelligence test and then estimated their performance.Before offering their estimates,the participants were informed either that they would receive immediate feedback on their performance,that the feedback on their performance would be de-layed because of a broken machine and not provided in a face-to-face setting,or that their test performance was anonymous and therefore no feedback would be avail-able.If people with low self-esteem underestimate their performance primarily due to self-presentation concerns,low self-esteem participants in this study should have reported lower estimates of their performance than high self-esteem participants only when they expected immediate,interpersonal feedback about their score.If low self-esteem people underestimate their performance for other reasons that do not reflect protecting their self-image vis-`a-vis others,then they also should have underestimated their performance in either or both of the other two conditions.MethodParticipants and Design.Forty-four women and26undergraduate students at a large university took part in the study to receive partial fulfillment of a courseSelf-Affirmation and Self-Image Vis-`a-Vis Others45 requirement.The participants were divided based on their scores on the Rosenberg (1965)self-esteem scale given at the beginning of the semester in a mass screening questionnaire.Those participants scoring in the top third of all respondents were designated as having high self-esteem,while participants scoring in the bottom third were designated as having low self-esteem.Participants scoring in the middle third were excluded to avoid misclassification.The experiment used a2(self-esteem)×3(feedback)factorial design.Partic-ipants with either relatively high or relatively low self-esteem were led to believe that either they would receive immediate feedback on their performance(imme-diate condition),that they could receive feedback on their performance in a few days via the mail(delayed,impersonal condition),or that their results would be anonymous(no feedback condition).Procedure.When participants came to the laboratory they were informed that they would be taking a new form of intelligence test.The test was actually a version of the Ammons and Ammons(1962)Quick Test of Intelligence.The test required participants to identify pictures that illustrate very difficult vocabulary words. Pretesting indicated that this population of participants would have considerable difficulty with the test.This test and procedure were similar to that used in Fein& Spencer(1997).Participants in the immediate feedback condition were told that the experi-menter would score their test after they completed it and that he would inform them of their score.Participants in the delayed,impersonal feedback condition were told that the experimenter usually scored the test right after theyfinished it but he would not be able to because the machine was broken,and that they could obtain their scores in three days via the mail if they wanted them.Participants in both of these conditions were told to put their names on their answer stly,participants in the anonymous condition were told the results of their test would be sent to the school of education and that their names would not be associated with their tests. These participants were told not to put their names on their answer sheets.The experimenter next explained the directions for the test and administered the test to all participants.Participants made their responses on an answer sheet that could be scored by machine.After the participants in the immediate-feedback conditionfinished the test,the experimenter collected the answer sheets saying,“I’ll take these and run them through the machine and bring you back a score.”In the delayed,impersonal condition the experimenter collected the answer sheets and noted on a pad the participant’s name and participant number.In the anonymous condition participants folded their answer sheets,put them in an envelope,and then sealed,addressed,and mailed the envelope(a campus mailbox was in the room).Following these procedures,all participants received a questionnaire contain-ing the dependent measures,and the experimenter left the room.To preserve the integrity of the cover story,the questionnaire posed somefiller questions about the clarity of the directions and the pictures used in the test.More importantly,the questionnaire instructed the participants to use a100-point scale to estimate the46Spencer,Fein,and Lomore test score they thought the average student would earn,and to use the same scale to estimate their own test score.The questionnaire also asked the participants to use a9-point scale to rate how valid they felt the test was.After the participants completed the questionnaire,the experimenter returned and debriefed the participants thoroughly.ResultsOur primary hypothesis was that low self-esteem participants would estimate lower scores for themselves than would high self-esteem participants when they expected to receive immediate feedback,but that their estimates would not differ from those of high self-esteem participants if they thought they would not be told their scores right away or at all.A2(level of self-esteem)×3(feedback condition)analysis of variance (ANOV A)of participants’estimates of their scores revealed a significant main effect for level of self-esteem,with high self-esteem participants estimating higher scores than low self-esteem participants F(1,72)=9.60,p<.01.There was also a significant main effect for feedback condition,indicating that participants who expected immediate disclosure estimated lower scores than did participants in the other conditions F(2,72)=10.00,p<.001.Most importantly,these main effects were qualified by a significant interaction,F(2,72)=5.07,p<.01.As can be seen in Fig.1,this interaction conformed to our predictions.When participants expected to receive immediate feedback,those with low self-esteem offered significantly lower estimates of their performance than did high self-esteem participants,but this difference did not emerge in the other conditions.Fisher’s Least Significant Difference post hoc contrasts revealed that the mean for low self-esteem participants who expected immediate feedback was significantly lower than the means in each of the other conditions(p’s<.05).No other means were significantly different from each other.There were no significant differences in the participants’ratings of valid-ity of the test(F’s<2.7,p’s>.10),or in their actual performance on the test (F’s<1.5,p’s>.10).With the exception of a significant main effect of feed-back condition,F(2,72)=3.60,p<.05,there also were no effects on the estimates of the score of the average person(F’s<2.7,p’s>.10).Participants who expected immediate feedback tended to estimate lower scores(M=51.31)than did par-ticipants in the delayed,impersonal feedback condition(M=58.04),who in turn tended to give lower estimates than did participants in the anonymous condition (M=60.80),although none of these differences reached statistical significance. Although this main effect had not been predicted,it does not appear to raise any alternative interpretations of the primary pattern of results in this study,particularly in light of the fact that high and low self-esteem participants did not differ in these estimates.Self-Affirmation and Self-Image Vis-`a-Vis Others47Fig.1.Estimated performance on the intelligence test as a function of self-esteem anddisclosure condition.DiscussionThe results of Study1demonstrated that when participants with low self-esteem expected immediate,face-to-face feedback on their performance,they re-ported lower scores than did their high self-esteem counterparts,presumably to protect themselves from appearing foolish in the eyes of the experimenter.When their self-presentational concerns were minimized by the absence of the prospect of immediate,face-to-face feedback,low self-esteem participants did not differ from those with high self-esteem.These results provide a conceptual replication of Shrauger’s(1972)research demonstrating that low self-esteem people reduce their estimates of their perfor-mance in front of an audience whereas high self-esteem people do not.The current research also extends Shrauger’sfindings by demonstrating that the lower estimates of low self-esteem people only occurs when there is a potential encounter between the participant and those who know about his or her score.Simply knowing that48Spencer,Fein,and Lomore they,or someone else,would know their score in the future was not enough to cause participants with low self-esteem to report lower estimates.This difference between the immediate-feedback and delayed-feedback con-ditions is consistent with research on self-presentation and impression manage-ment suggesting that self-presentation concerns are much stronger when they occur in the immediate situation(Baumeister,1982;Schlenker,1980;Shepperd, Ouellette,&Fernandez,1996;Tedeschi,1981).It is also consistent with research by Gilovich,Kerr,and Medvec(1993)who found that people become less con-fident about their performance and more self-critical as they are about to receive feedback.If we assume that low self-esteem people experience a greater drop in their confidence and more self-doubts than do high self-esteem people in this situation then it is not surprising that they would report lower estimates of their performance.Study2Having established in Study1that people with low self-esteem may be prone to self-deprecation when in a situation in which they have reason to be concerned about their self-image vis-`a-vis others,we designed Study2to test whether self-affirmation can alleviate these concerns.In this study all participants were placed in the situation in which self-presentational concerns would be relatively high—they were told that they would receive immediate feedback about their performance on the difficult intelligence test.Before making their estimates,however,half of the participants completed a value scale that was self-affirming and half completed a value scale that was not self-affirming.Among the participants who were not self-affirmed,we expected to replicate the results of the immediate disclosure condition in Study1—i.e., low self-esteem participants would give lower estimates of their performance than would high self-esteem participants.Among those who were self-affirmed,how-ever,we expected no difference between high and low self-esteem participants’estimates.MethodParticipants and Design.Thirty-three women and31undergraduate students at a large university took part in this study to fulfill part of a course requirement. Using the same procedure as in Study1,the participants were divided based on their scores on the Rosenberg(1965)self-esteem scale.The experiment used a2×2factorial design.Thefirst factor was the partic-ipant’s level of self-esteem(high or low),and the second was the self-affirmation manipulation.Self-Affirmation and Self-Image Vis-`a-Vis Others49 Procedure.When participants came to the laboratory,they were informed that they would be completing two tasks.Thefirst task was described as a preliminary study of values(this was actually the self-affirmation manipulation)and the second task was described as concerning a new form of intelligence test.Except for the self-affirmation manipulation,the materials and procedure were identical to those used in the immediate-feedback condition of Study1.Manipulation of self-affirmation.Half of the participants were randomly as-signed to the self-affirmation condition and half were assigned to the no-affirmation condition.The manipulation was similar to that used by Tesser&Cornell(1991). In a mass testing session at the beginning of the term participants rank ordered the importance of several values(adapted from values characterized by Allport, Vernon,&Lindzey,1951),including“business/economics,”“art/music/theatre,”“social life/relationships,”and“science/pursuit of knowledge.”When participants came to the lab those in the self-affirmation condition were asked to complete a value scale that corresponded to the value they had ranked as most important to them in mass testing.Participants in the no-affirmation condition,in contrast,were asked to complete a value scale that corresponded to the value they had ranked as least important to them in mass testing.ResultsOur primary hypothesis was that relative to participants with high self-esteem, those with low self-esteem would estimate lower scores if they were not affirmed, but that this difference would be eliminated if they were self-affirmed.A2(level of self-esteem)×2(self-affirmation manipulation)ANOV A for par-ticipants’estimates of their score revealed only a significant interaction,F(1,60)= 4.36,p<.05.As can be seen in Fig.2,participants’estimates of their performance on the intelligence test conformed to our predictions.Fisher’s Least Significant Difference post hoc contrasts revealed that the low self-esteem participants who were not self-affirmed estimated significantly lower scores than did the partici-pants in each of the other conditions.No other conditions differed significantly from each other.There were no significant differences in ratings of the validity of the test (F’s<1),or in participants’actual performance on the test(F’s<1).There also were no significant differences in participants’estimates of the score of the average person(F’s<1.5,p’s>.20).DiscussionThesefindings suggest that self-affirmation ameliorated the otherwise height-ened concern that participants with low self-esteem had with self-presentation.As in Study1,when participants were not self-affirmed,those with low self-esteem50Spencer,Fein,and LomoreFig.2.Estimated performance on the intelligence test as a function of self-esteem and self-affirmation condition.reported lower estimates of their performance than did high self-esteem partici-pants.When they were self-affirmed,in contrast,those with low self-esteem re-ported much higher scores,which were roughly the same as those given by the participants with high self-esteem.These results suggest that when people with low self-esteem are induced to think about an important value in another domain of their self-concept,they become less concerned with protecting themselves from the awkward social exchange that might occur if they predict a score that turns out to be too high.The results of Study2raise two important points.First,people with low self-esteem can be self-affirmed.Although self-affirmation theory has never proposed that low self-esteem people would not experience self-affirmation when writing about an important value,some empiricalfindings have called this into question. Steele,Spencer,and Lynch(1993)found that when high and low self-esteem participants completed a self-esteem scale prior to making a difficult decision,those with high self-esteem showed no dissonance-reducing rationalization of their choice,whereas those with low self-esteem showed an especially large amount of dissonance-reducing rationalization.This difference implied thatfilling out the self-esteem scale served as a self-affirmation for high self-esteem people,but had no such effect for low self-esteem people.It is not implausible that taking stock in one’s self-esteem would be affirming for those rich in self-esteem but not for those who are more lacking in this commodity.In an even more relevant study,Dodgson and Wood(1998)gave high and low self-esteem participants negative feedback and measured the participants’activa-tion of their personal strengths and weaknesses.The results indicated that those with high self-esteem exhibited increased activation of their strengths after failure but those with low self-esteem did not,suggesting that high but not low self-esteem people were able to spontaneously recruit self-affirmational resources after failure.Findings such as these raise the question of whether low self-esteem people could benefit from self-affirmation.The results of the current study,however, suggest that even if people with low self-esteem people might have difficulty spontaneously recruiting self-affirmational resources,they can indeed be affirmed by being induced to think about a self-relevant value.These results also demonstrate that being able to self-affirm can be important for people with low self-esteem because it can reduce their concern with threats to their self-image vis-`a-vis others.This suggests that although concern about how one is viewed by others is an important part of how people maintain their self-image,it is not so important that other self-image resources cannot reduce the impact of this threat.A question raised by this reasoning is whether these other self-image resources must also concern interpersonal aspects of the self in order to reduce the threat to the self-image vis-`a-vis others.In our study,one of the values for which participants completed a value scale was“social life/relationships.”Clearly this is quite relevant to the interpersonal nature of the self.The other values,however,were less directly relevant,such as“science/pursuit of knowledge.”Although this had not been our intention when we designed the study,we examined this issue by re-analyzing the data according to whether or not the participants in the self-affirmation condition completed the most interpersonal value scale.Of the32participants who received the self-affirmation instructions,17ranked“social life/relationships,”as their most important value and15ranked one of the other values as their most important.4 Given this distribution,we conducted a2(level of self-esteem)×2(whether or not they ranked“social life/relationships”as their most important value)ANOV A on the estimates given by the participants in the self-affirmation conditions.This 4The participants in the no-affirmation condition completed a value scale for the value that they ranked as least important.Only two of the32participants in this condition ranked“social life/relationships,”as their least important value.This distribution is not surprising,given the theory and research that we have reviewed that suggest that relationships are a central part of the self-concept.。

斯普拉巴托(卑斯卡迪芬)(鼻吸)说明书

Spravato™ (esketamine)(Intranasal)Document Number: IC-0481 Last Review Date: 10/01/2020Date of Origin: 05/13/2019Dates Reviewed: 05/2019, 07/2019, 02/2020, 10/2020I.Length of Authorization•Initial: 4 weeks•Renewal: 4 weeks for first renewal; 3 months for subsequent renewalsII.Dosing LimitsA.Quantity Limit (max daily dose) [Pharmacy Benefit]:•Induction (weeks 1 to 4): 2 kits/week (84 mg kit); (one 56 mg kit Day 1)•Maintenance (weeks 5 to 8): 1 kit/week (84 mg kit)B.Max Units (per dose and over time) [Medical Benefit]:Treatment Resistant Depression−Induction (weeks 1 to 4): 84 mg twice weekly (56 mg Day 1)−Maintenance (weeks 5 to 8): 84 mg weeklyMajor Depressive Disorder (MDD)− 2 kits (84 mg kit) weeklyIII.Initial Approval Criteria•Patient is at least 18 years old; AND•Patient has a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) diagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD); AND•Patient must have a baseline assessment using any validated depression rating scale (e.g., Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale [MADRS], Hamilton Depression Rating Scale[HAM-D], Patient Health Questionnaire Depression Scale [PHQ-9], Beck DepressionInventory [BDI]); AND•Esketamine is prescribed by or in consultation with a psychiatrist or psychiatric mental health nurse practitioner (PMHNP); AND•Patient must NOT have a current or prior DSM-5 diagnosis of any of the following: o Concomitant psychotic disorder; ORo MDD with psychosis; ORo Bipolar or related disorders; ORo Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD); ORo History of moderate to severe substance or alcohol use disorder; ORo Personality disorder; AND•Patient must NOT have any of the following conditions:o Aneurysmal vascular disease; ORo Arteriovenous malformation; ORo History of intracerebral hemorrhage; ORo Uncontrolled hypertension (greater than 140/90 mmHg in patients less than 65 years old or greater than 150/90 mmHg in patients 65 or older); AND•Patient must NOT be pregnant; AND•Patient must NOT have intellectual disability; AND•Patient must NOT have known hypersensitivity to any component of the product; AND •Patient is NOT receiving concomitant ketamine therapy; AND•Patient must be taking esketamine in conjunction with an antidepressant medication (esketamine is not to be used as monotherapy); AND•Attestation that prescriber’s healthcare setting is certified in the Spravato Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) program; AND•Attestation that the prescriber will check blood pressure prior to each visit AND is capable of monitoring patient as directed following administration, ensuring patient has been stable for at least 2 hours, with baseline or decreasing blood pressure, prior to cessation ofmonitoring; AND•Prescriber attestation that he/she has reviewed the dosing schedule with the patient; AND •Prescriber attestation that patient understands and is committed to receiving scheduled doses AND has the capability of being available twice a week with adequate transportation to and from treatment facility; ANDTreatment-Resistant Depression (TRD) †•Patient has a history of adherence with oral therapy (compliant with at least 80% of their doses as evident by refill history or prescriber attestation during current depressiveepisode); AND•Patient has failed a trial of antidepressant augmentation therapy for a duration of at least 6weeks in the current depressive episode with at least 1 of the following, unlesscontraindicated or clinically significant adverse effects are experienced (see ‘failed trial’ asdefined above):o An antidepressant from a different class; ORo An atypical antipsychotic; ORo Lithium; AND•Patient has tried psychotherapy alone or in combination with oral antidepressants, if psychotherapy resource available; AND•Patient must NOT have failed prior ketamine treatment for MDD; AND•Patient is NOT receiving concomitant electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), or deep brain stimulation(DBS); AND•Patient has failed a trial of at least 2 antidepressants of different classes for a duration of at least 6 weeks each at generally accepted doses in the current depressive episode, unlesscontraindicated or clinically significant adverse effects are experienced (‘Failed trial’ isdefined as less than 50% reduction in symptom severity using any validated depressionrating scale)Depressive Symptoms In Patients With Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) With Acute Suicidal Ideation/Behavior †•Patient must meet criteria for acute inpatient hospitalization per prescriber attestation; OR •Patient has recently been discharged from a hospital in which treatment with esketamine has been initiated† FDA Approved Indication(s)IV.Renewal Criteria•Patient must continue to meet the above criteria; AND•Patient has not experienced unacceptable toxicity (dissociation, cognitive impairment, etc.);AND•Prescriber attestation that patient has committed to receiving all scheduled doses thus far in treatment and will continue to do so; AND•Patient must demonstrate disease improvement and/or stabilization as a result of the medication, as documented by a 50% reduction in symptom severity using any validateddepression rating scale.V.Dosage/AdministrationDoseTreatment- resistant depression (TRD) Induction (administer twice per week):•Day 1: 56 mg•Weeks 1 to 4 subsequent doses: 56 mg or 84 mg Maintenance:•Weeks 5 to 8: 56 mg or 84 mg once weekly•Weeks 9 and after: 56 mg or 84 mg once every 2 weeks or once weekly** Dosing frequency should be individualized to the least frequent dosing to maintain remission/response.Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) Administer Spravato in conjunction with an oral antidepressant (AD).−The recommended dosage of Spravato for the treatment ofdepressive symptoms in adults with MDD with acute suicidalideation or behavior is 84 mg twice per week for 4 weeks.−Dosage may be reduced to 56 mg twice per week based ontolerability.−After 4 weeks of treatment with Spravato, evidence of therapeutic benefit should be evaluated to determine need for continuedtreatment.−The use of Spravato, in conjunction with an oral antidepressant,beyond 4 weeks has not been systematically evaluated in thetreatment of depressive symptoms in patients with MDD with acute suicidal ideation or behavior.VI.Billing Code/Availability InformationHCPCS:•J3490 – Unclassified drugs•S0013 – Esketamine, nasal spray, 1 mg: 1 billable unit = 1 mg•*G2082 – Office or other outpatient visit for the evaluation and management of an established patient that requires the supervision of a physician or other qualified healthcare professional and provision of up to 56 mg of esketamine nasal self-administration,includes 2 hours post-administration observation•*G2083 – Office or other outpatient visit for the evaluation and management of an established patient that requires the supervision of a physician or other qualified healthcare professional and provision of greater than 56 mg esketamine nasal self-administration,includes 2 hours post-administration observation* Required for Medicare part B claims. For non-Medicare, those that do not accept the G Codes, providers may continue to report separate codes for the drug and service using the miscellaneous drug code (J3490– unclassified drug) for Spravato and the most appropriate E/M CPT® code for the service.NDC:•56 mg Dose Kit: Unit-dose carton containing two 28 mg nasal spray devices (56 mg total dose): 50458-0028-xx•84 mg Dose Kit: Unit-dose carton containing three 28 mg nasal spray devices (84 mg total dose): 50458-0028-xxVII.References1.Spravato [dossier]. Titusville, NJ; Janssen; July 2020.2.Papakostas GI. Incidence, impact, and current management strategies for treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. Medscape. Available at:https:///viewarticle/574817_1. Accessed May 3, 2019.3.American Psychiatric Association Work Group on Major Depressive Disorder. Practiceguideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. 3rd ed. October 2010.Available at:https:///pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf.Accessed May 3, 2019.4.Major Depression. National Institute of Mental Health. Available at:https:///health/statistics/major-depression.shtml. Accessed May 3, 2019.5.Johnston KM, Powell LC, Anderson IM, et al. The burden of treatment-resistant depression:a systematic review of the economic and quality of life literature. J Affect Disord. 2019; 242:195-210. DOI: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.06.045.6.American Psychiatric Association Work Group on Major Depressive Disorder. Practiceguideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. 3rd ed. October 2010.Available at: https:///psychiatrists/practice/clinical-practice-guidelines.Accessed May 3, 2019.7.Socci C, Medda P, Toni C, et al. Electroconvulsive therapy and age: age-related clinicalfeatures and effectivenes s in treatment resistant major d epressive episode. J Affect Disord. 2018;227:627-632.Appendix 1 – Covered Diagnosis CodesICD-10 DescriptionF32.0 Major depressive disorder, single episode, mildF32.1 Major depressive disorder, single episode, moderateF32.2 Major depressive disorder, single episode, severe without psychotic featuresF32.3 Major depressive disorder, single episode, severe with psychotic featuresF32.4 Major depressive disorder, single episode, in partial remissionF32.5 Major depressive disorder, single episode, in full remissionF32.9 Major depressive disorder, single episode, unspecifiedF33.0 Major depressive disorder, recurrent, mildF33.1 Major depressive disorder, recurrent, moderateF33.2 Major depressive disorder, recurrent severe without psychotic featuresF33.3 Major depressive disorder, recurrent, severe with psychotic symptomsF33.40 Major depressive disorder, recurrent, in remission, unspecifiedF33.41 Major depressive disorder, recurrent, in partial remissionF33.42 Major depressive disorder, recurrent, in full remissionF33.8 Other recurrent depressive disordersF33.9 Major depressive disorder, recurrent, unspecifiedAppendix 2 – Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)Medicare coverage for outpatient (Part B) drugs is outlined in the Medicare Benefit Policy Manual (Pub. 100-2), Chapter 15, §50 Drugs and Biologicals. In addition, National Coverage Determination (NCD), Local Coverage Determinations (LCDs), and Articles may exist and compliance with these policies is required where applicable. They can be found at: /medicare-coverage- database/search/advanced-search.aspx. Additional indications may be covered at the discretion of the health plan.Medicare Part B Covered Diagnosis Codes (applicable to existing NCD/LCD/Article): N/AMedicare Part B Administrative Contractor (MAC) JurisdictionsJurisdiction Applicable State/US Territory ContractorE (1) CA, HI, NV, AS, GU, CNMI Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLCF (2 & 3) AK, WA, OR, ID, ND, SD, MT, WY, UT, AZ Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC5 KS, NE, IA, MO Wisconsin Physicians Service Insurance Corp (WPS)6 MN, WI, IL National Government Services, Inc. (NGS)H (4 & 7) LA, AR, MS, TX, OK, CO, NM Novitas Solutions, Inc.8 MI, IN Wisconsin Physicians Service Insurance Corp (WPS) N (9) FL, PR, VI First Coast Service Options, Inc.J (10) TN, GA, AL Palmetto GBA, LLCM (11) NC, SC, WV, VA (excluding below) Palmetto GBA, LLCL (12) DE, MD, PA, NJ, DC (includes Arlington &Novitas Solutions, Inc.Fairfax counties and the city of Alexandria in VA)K (13 & 14) NY, CT, MA, RI, VT, ME, NH National Government Services, Inc. (NGS)15 KY, OH CGS Administrators, LLC。

英语保持身体健康的谚语

英语保持身体健康的谚语导读:1、若要身体壮,饭菜嚼成浆。

If you want to be strong, chew the food into pulp.2、宁可锅中存放,不让肚子饱胀。

It's better to store it in a pot than to have a full stomach.3、娱乐有制,失制则精疲力竭。

Entertainment is institutionalized, but failure is exhausting.4、春捂秋冻,不生杂病。

Spring covers autumn frozen, no miscellaneous diseases.5、三餐不过饱,无病活到老。

Three meals are not enough, and you live to old age without illness.6、晚上少吃一口,肚里舒服一宿。

Eat less in the evening and have a comfortable night in your stomach.7、乐靠自得,趣靠自寻。

Joy depends on self-satisfaction, fun depends on self-seeking.8、冬不蒙首,春不露背。

Winter does not cover the head, spring does not reveal the back.9、哭一哭,解千愁。

Cry, relieve a thousand sorrows.10、心灵手巧,动指健脑。

Hand and soul, finger and brain.11、蔬菜是个宝,餐餐不可少。

Vegetables are a treasure and meals are indispensable.12、戒烟限酒,健康长久。

Stop smoking and limit alcohol, and keep healthy for a long time.13、中午睡觉好,犹如捡个宝。

Teenage BehaviorUnderstanding Trends

Teenage BehaviorUnderstanding Trends Teenage Behavior: Understanding TrendsAs teenagers go through adolescence, they experience significant changes in their physical, emotional, and social development. These changes often manifest in their behavior, which can be confusing and frustrating for parents, teachers, and other adults. Understanding teenage behavior trends can help us better support and guide young people during this critical stage of their lives.1. Risk-taking behaviorOne of the most common teenage behavior trends is risk-taking behavior. Adolescents are more likely to engage in risky activities such as drug and alcohol use, reckless driving, and unprotected sex. This behavior is often driven by a desire to assert independence and take risks, as well as peer pressure and a lack of awareness of the potential consequences.2. Mood swingsTeenagers also experience frequent mood swings, which can be challenging for parents and caregivers to navigate. Hormonal changes, stress, and social pressures can all contribute to these emotional ups and downs. It is important to understand that these mood swings are a normal part of adolescent development and to provide a supportive and non-judgmental environment for young people to express their feelings.3. Social media useThe rise of social media has had a significant impact on teenage behavior trends. Many young people spend hours each day scrolling through social media feeds, comparing themselves to others, and seeking validation through likes and comments. This can lead to feelings of anxiety, depression, and low self-esteem. It is important for parents and caregivers to monitor their children's social media use and encourage healthy habits and boundaries.4. Sleep patternsAdolescents often have irregular sleep patterns, staying up late and sleeping in on weekends. This can be attributed to a variety of factors, including biological changes, academic demands, and social activities. Lack of sleep can have negative effects on physical and mental health, including increased risk of obesity, depression, and anxiety. Encouraging healthy sleep habits, such as setting a consistent bedtime and avoiding screens before bed, can help support teenagers' overall well-being.5. Identity formationDuring adolescence, young people are also developing their sense of identity. They are exploring their interests, values, and beliefs, and trying to figure out who they are and where they fit in the world. This can lead to experimentation with different styles, activities, and social groups. It is important for adults to support this process of identity formation and provide opportunities for young people to explore their interests and passions.6. Communication challengesFinally, teenage behavior trends can also include communication challenges. Adolescents may struggle to communicate effectively with adults, feeling misunderstood or dismissed. They may also struggle to express their emotions and needs in a healthy and constructive way. It is important for adults to practice active listening, empathy, and open communication with young people, creating a safe and supportive environment for them to express themselves.In conclusion, understanding teenage behavior trends is essential for supporting young people during this critical stage of their development. By recognizing the challenges they face and providing a supportive and non-judgmental environment, we can help teenagers navigate the ups and downs of adolescence and emerge as confident and resilient adults.。

具有强抗噪声能力的图像分割方法

第31卷第3期 红外与激光工程 2002年6月Vol.31No.3 Infrared and Laser Engineering J un.2002具有强抗噪声能力的图像分割方法曹永锋,郑建生,万显容(武汉大学电子信息学院通信系,湖北武汉 430079) 摘要:尽可能多地综合利用图像整体和细部信息,是精确分割图像、提取特征的关键。

流域思想利用了整体信息,应用于梯度图像上,兼顾了细部信息。

引入待分割物体全局连通性,将这种方法用于物体与背景的分割,得到了极好的分割效果,对噪声有极强的抑制能力,同时具有原理简单、分割结果为连续单像素边缘、边缘定位准确、可以同时标记多个区域等优点。

给出了形态学流域算法的基本原理及数学实现,同时也总结了方法的缺点和解决途径。

关 键 词: 数学形态学; 流域算法; 抗噪声; 图像分割; 轮廓提取中图分类号:TP391 文献标识码:A 文章编号:100722276(2002)0320208204Method of im age segmentation with high anti2noise perform anceCAO Y ong2feng,ZHEN G Jian2sheng,WAN Xian2rong(Department of Communication,College of Electronic Information,Wuhan University,Wuhan430079,China)Abstract:The key problem of accurate image segmentation and character extraction is to utilize information of both whole image and local sections as much as possible.Idea of drainage area based onwhole image information takes account of local information when it is applied on gradient image.Ex2cellent segmentation result and the ability of restraining image noise are obtained when this approach isused in the segmentation of object and background and the overall connectivity of object to be segment2ed is lead in.Advantages,such as simple principle,connected single pixel edge output,accurate edgeorientation and simultaneous output of different signaled areas,are proven.The principle and mathe2matical description of the watershed algorithm are shown,and the disadvantages and resolving strategyare summarized.K ey w ords: Mathematical morphology; Watershed algorithm; Anti2noise;Image segmen2tation; Contour extraction 收稿日期:2001212204作者简介:曹永锋(19762),男,河北省冀州市人,助教,在职研究生,主要从事图像处理、机器视觉和SAR图像处理分析等方面的研究。