科学文献

科技文献的定义

科技文献的定义科技文献是指记录科学研究成果、科技发展动态和科技管理经验的文献资料。

它是科学研究、技术创新和科技管理的重要依据和参考,对于推动科技进步和社会发展具有重要的作用。

科技文献的主要特点是准确性、权威性和时效性。

作为科学研究成果的记录,科技文献要求准确地反映研究方法、实验数据和结论,确保信息的真实性和可靠性。

同时,科技文献也需要具备权威性,即来源于有专业知识和经验的科学家、工程师和技术专家,经过同行评议和学术机构认可的论文、报告和专著等。

此外,科技文献还要具备时效性,及时反映科技发展的最新成果和动态,使读者能够及时了解科技前沿和最新趋势。

科技文献主要包括学术论文、科技报告、专利文献、技术标准和科技期刊等。

学术论文是科学研究成果的主要表现形式,它通过系统的实验或理论分析,提出新的理论、方法和结论,通过同行评议后发表在学术期刊上。

科技报告是研究项目的成果报告或研究机构的研究成果总结,它通常包含研究目的、方法、实验结果和结论等内容。

专利文献是专利申请和授权的文件,记录了发明创造的具体技术方案和实施方式。

技术标准是科技发展的规范和指南,通过规定产品的技术要求和测试方法,保障产品的质量和安全。

科技期刊是科学研究成果的重要发布渠道,它定期出版学术论文和研究报告,提供科技信息的交流和共享平台。

科技文献的利用可以促进科学研究的发展和技术创新的进步。

科学家和工程师可以通过查阅和分析科技文献,了解前人的研究成果和经验,避免重复劳动和错误,为自己的研究工作奠定基础。

科技管理人员可以通过研究科技文献,掌握科技发展的动态和趋势,制定科技政策和计划,引导科技创新和产业升级。

工程师和技术人员可以通过科技文献,学习新的技术方法和应用案例,提高自己的专业能力和技术水平。

科技文献是科学研究、技术创新和科技管理的重要资源和工具。

科技工作者应该重视科技文献的收集和利用,不断更新自己的知识和技能,推动科技进步和社会发展。

同时,科技出版机构和科技管理部门也应该加强对科技文献的管理和服务,提高科技文献的质量和影响力,为科技创新提供有力支持。

高中生如何有效阅读科学文献

高中生如何有效阅读科学文献科学文献是高中生学习科学知识的重要资源,它们包含了前沿的研究成果和学术观点。

然而,对于许多高中生来说,阅读科学文献可能是一项具有挑战性的任务。

本文将介绍一些帮助高中生有效阅读科学文献的方法和技巧。

一、选择适合的文献在开始阅读科学文献之前,高中生应该学会选择适合自己的文献。

首先,他们可以通过在学校图书馆或在线数据库中搜索关键词来找到相关的文献。

其次,他们应该根据自己的学习目标和兴趣选择文献。

例如,如果他们对生物学感兴趣,那么可以选择与生物学相关的研究论文。

二、了解文献的结构科学文献通常由摘要、引言、方法、结果和讨论等部分组成。

高中生在阅读文献之前,应该先了解这些部分的作用和内容。

摘要通常是文献的概要,可以帮助读者快速了解研究的目的和主要结果。

引言部分介绍了研究的背景和目的,方法部分描述了研究的实验设计和数据采集方法,结果部分展示了实验结果,讨论部分对结果进行解释和分析。

三、注意关键词和术语科学文献中常常使用一些专业的术语和关键词,高中生应该学会识别和理解这些术语。

他们可以通过查阅词典或在线资源来解释这些术语的含义。

此外,高中生还可以将这些术语和关键词记录下来,以便在阅读过程中进行参考和复习。

四、提问和思考在阅读科学文献时,高中生应该保持积极的思考和提问的态度。

他们可以思考文献中的研究问题、实验设计和结果,并提出自己的疑问和观点。

通过提问和思考,他们可以更好地理解文献的内容,并培养批判性思维能力。

五、扩展阅读阅读科学文献不仅限于一篇文章,高中生可以通过扩展阅读来深入了解某个主题。

例如,他们可以查阅相关的综述文章、书籍或其他研究论文,以获取更全面的知识。

扩展阅读还可以帮助高中生了解当前研究领域的热点问题和最新进展。

六、记录和总结在阅读科学文献时,高中生应该养成记录和总结的习惯。

他们可以使用笔记本或电子工具来记录重要的观点、关键词和疑问。

此外,他们还可以将阅读的内容进行总结和归纳,以便后续的学习和复习。

如何阅读科学文献

如何阅读科学文献阅读科学文献对于科研工作者和学术界的人士非常重要。

通过阅读科学文献,我们可以了解最新的研究进展,与同行进行交流与合作,提高自身的学术能力和水平。

然而,对于一些初学者或者对特定领域不熟悉的人来说,阅读科学文献可能是一项具有挑战性的任务。

在本文中,我将分享一些关于如何阅读科学文献的方法和技巧。

一、了解文献的分类和来源科学文献通常可以分为多种类型,包括期刊论文、会议论文、学位论文、专著和技术报告等。

这些文献来源的权威性和可信度有所不同,应根据需要选择合适的文献进行阅读。

常见的文献数据库包括PubMed、Scopus、Web of Science等,可以通过检索关键词或者作者的姓名来查找相关的文献。

二、阅读文献之前的准备工作在阅读科学文献之前,我们可以进行一些准备工作,以提高阅读效率和理解能力。

首先,要了解相关领域的基本知识和术语,这样在阅读文献时就能更好地理解和理解作者的观点和实验内容。

其次,可以查找文献的综述或者评论性文章,了解该领域的发展和当前的研究进展,从而对文献有一个整体的了解。

最后,可以制定一个阅读计划,设定合理的阅读时间和目标,提高阅读的效率。

三、阅读科学文献的技巧1. 精读和泛读结合对于篇幅较长或者对自己比较重要的文献,可以进行精读。

在精读时,要认真阅读摘要和介绍部分,了解研究的背景和目的,然后逐段、逐句进行仔细阅读,理解作者的实验设计和研究结果。

在阅读过程中,可以做一些标记或者写下关键点,以便于后续的回顾和整理。

对于篇幅较长或者对自己不是很重要的文献,可以进行泛读。

在泛读时,可以关注文献的结构、图表和重点段落,了解作者的主要观点和研究结果。

泛读可以帮助快速获取信息,筛选出对自己研究有用的文献。

2. 多角度阅读在阅读科学文献时,要注意从多个角度进行思考和分析。

可以思考文献的创新点、实验设计、结果解释以及与其他相关文献的联系。

可以尝试用自己的话总结和表达作者的观点和结论,以帮助更好地理解文献内容。

科学文献的名词解释

科学文献的名词解释

文献:

1. Abstract

2. Bibliographic Database

3. Editor

4. Index

一、Abstract:

抽象是科学文献中概述性段落的内容,即文章的摘要,它在文献的开头,能简要介绍文献的内容和目的,是科学文献查找、分析和利用的重要基础。

Abstract由一般性问题、技术方法、重要结果、结论和指出事实的综述性的评论组成,概述文献的内容及方法,是检索文献信息的重要依据。

二、Bibliographic Database:

文献数据库是以文献数据为基础建立起来的文献信息体系,其主要内容是存储文献信息(如书籍、期刊、报纸、图书、报告摘要、摘录、贴文等)的元数据,并提供跨文献的快速检索的功能。

一般而言,文献数据库由代表文献的描述性元数据(如题名、作者、出版社、出版日期等)和用于检索所建立的全文索引组成。

三、Editor:

编辑是指组织、审查和整理文献内容,以便发表的这类编辑服务活动。

编辑可以编排、修改、撰写、组织文献,编辑从文献撰写、组织和修订等方面起着协调作用,以确保出版物的质量。

四、Index:

索引是科学文献检索的一个重要技术工具,它的主要目的是使读者能够轻松找到所需要的信息。

索引包括有关文献的词汇表,能够提供有用的参考资料,而无需检查整个文献的文本内容。

另外,索引还可以帮助读者了解文献的整体框架,有利于从文献中快速获取信息。

十大科技文献源

十大科技文献源科技的发展日新月异,不断推动着人类社会的进步。

以下是十大科技文献源,它们记录了人类在不同领域的探索和创新。

1.《自然》(Nature)作为世界上最古老的科学杂志之一,《自然》杂志为读者提供了丰富的科学研究成果和前沿的科技进展。

它既包括基础科学领域的研究,也关注应用科学的发展。

2.《科学》(Science)《科学》杂志是世界上最有影响力的综合性科学杂志之一,涵盖了各个学科领域的最新研究成果。

它以其高质量的科学报道和严谨的学术评审而闻名,是科学界的权威之一。

3.《人工智能》(Artificial Intelligence)《人工智能》期刊聚焦于人工智能领域的研究和应用,包括机器学习、自然语言处理、计算机视觉等。

它发布的论文对于推动人工智能技术的发展具有重要意义。

4.《物理评论快报》(Physical Review Letters)《物理评论快报》是物理学领域最具影响力的学术期刊之一,发表了许多重要的物理学突破性研究。

它以其简洁、精确和具有启发性的论文而受到广泛关注。

5.《细胞》(Cell)《细胞》杂志是细胞生物学和分子生物学领域的顶级期刊之一,报道了该领域的最新研究成果和突破性发现。

它对于理解生命的基本机制和疾病的发生机理具有重要意义。

6.《计算机视觉国际会议》(Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition)计算机视觉是人工智能领域的一个重要分支,该会议是该领域最重要的学术会议之一。

它汇集了来自全球的顶尖研究人员,分享了最新的计算机视觉技术和应用。

7.《美国国家科学院院刊》(Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences)《美国国家科学院院刊》是美国国家科学院的官方期刊,发表了各个学科领域的重要研究成果。

它是一本跨学科的期刊,涵盖了自然科学、社会科学和工程技术等领域。

8.《医学》(The Lancet)《医学》杂志是世界上最具影响力的医学期刊之一,发表了许多重要的医学研究。

科学阅读的方法和技巧

科学阅读的方法和技巧一、选择合适的文献1. 学术期刊:选择相关领域的学术期刊,如《Nature》、《Science》等,这些期刊发布的论文通常是经过同行评议且质量较高的。

2. 学术数据库:如Google学术、PubMed等,可以通过关键词检索相关文献。

3.学术会议:参考学术会议的论文集,了解最新的研究进展。

4.专业书籍:选择有权威性的专业书籍,如教科书、专著等。

二、调整阅读策略科学文献通常包含大量的专业术语和公式,阅读起来较为困难。

为了更好地理解文献内容,可以采用以下阅读策略:1.预览:先浏览全文的标题、摘要和关键词,了解文献的大致内容和观点。

2.筛选:根据自己的兴趣和研究方向,选择有重要参考价值的章节或段落进行重点阅读。

3.聚焦:在阅读过程中,将注意力聚焦在关键词、论证主线和实验结果等重要内容上。

4.意识流:尽量保持集中的阅读时间,避免受到干扰和分散注意力。

5.笔记:在阅读过程中做好笔记,记录关键信息和自己的理解和思考。

三、理解文献内容科学文献通常采用科学语言和专业术语,为了更好地理解文献内容,可以采用以下方法:1.查阅词典和参考书:查阅相关课本、词典、参考书籍等,弄清楚不熟悉的术语和概念。

2.加深背景知识:扩大自己的科学背景知识,了解相关领域的基本原理和理论框架。

3.多角度理解:通过阅读多个文献,了解不同研究观点和方法,从不同角度思考和分析问题。

4.精确解释:将复杂的概念或内容用自己的语言重新解释一遍,以确保自己理解透彻。

四、分析论证逻辑科学文献通常有一定的逻辑结构,分析论证逻辑有助于深入理解文献内容。

可以采用以下方法:1.总结主旨:通过阅读摘要、引言和结论等部分,总结文献的主旨和观点。

4.反思批判:对文献的内容进行批判性思考,发现可能存在的问题和不足之处。

五、扩展思考和应用1.感知科学思维:思考作者是如何发现问题、提出假设、设计实验和得出结论的,借鉴科学思维方法。

2.拓展思考:将文献中的观点与自己的观点进行比较和对比,思考存在的差异和原因,并以此为基础进行拓展思考。

科学文献阅读技巧详解

科学文献阅读技巧详解科学文献阅读技巧详解在科学研究的道路上,掌握有效的文献阅读技巧至关重要。

想象一下,文献就像是一座座深奥的宝库,里面珍藏着无数宝贵的知识和经验。

然而,要想从这些宝库中获取有用的信息,需要具备一定的技巧和策略。

首先,当你面对一篇新的科学文献时,它可能会显得有些“冷漠”。

不过,不要担心,这只是因为它还没有“认识”你。

开始阅读前,先浏览摘要部分,这就像与文献“打个招呼”,让它知道你对它感兴趣。

接下来,进入文献的正文部分,你会发现它有如一位导游,带领你探索未知的领域。

要有耐心,不要急于求成。

有时候,文献会使用复杂的术语和句子,就像在说一门外语一样。

这时,不妨反复阅读,逐步理解每一个词语背后的含义,就像与文献进行一场深入的交流。

在阅读过程中,可以时常停下来思考,并做好记录。

文献常常会提出问题或者让你有新的启发,这就像它在与你进行互动,促使你深入思考。

记得,做好笔记非常重要,这有助于你将碎片化的信息整理成有条理的知识体系。

此外,不要忽视文献中的图表和数据。

它们就像文献的“视觉演示”,通过直观的方式展示研究结果。

深入理解图表背后的数据,有助于你更全面地把握文献的核心内容。

最后,要保持批判性思维。

就像与一位智者交谈一样,不要轻易接受文献中的每一个观点。

要学会提出问题,评估实验设计的有效性,并思考研究结果的可能局限性。

这样,你才能更好地理解文献,甚至为未来的研究提供新的思路和方法。

总结来说,科学文献阅读并非一项简单的任务,它需要技巧和耐心。

通过与文献建立良好的互动关系,你将能够开启一段充满发现和启发的学术之旅。

不断地练习和改进阅读技巧,相信你定能在科学研究的道路上越走越远。

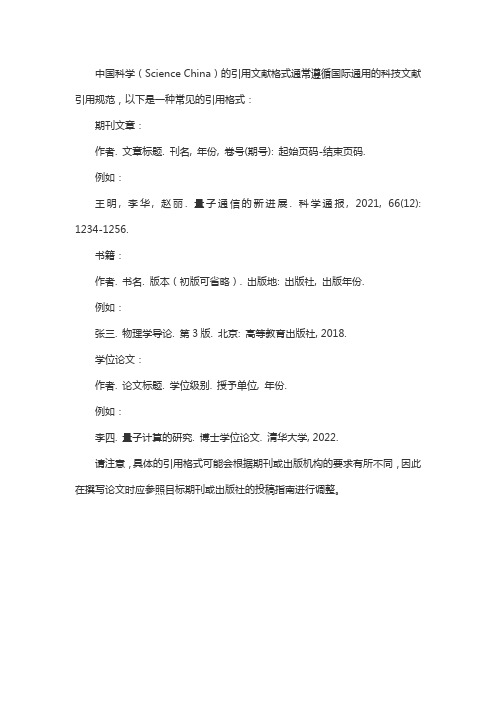

中国科学引用文献格式

中国科学(Science China)的引用文献格式通常遵循国际通用的科技文献引用规范,以下是一种常见的引用格式:

期刊文章:

作者. 文章标题. 刊名, 年份, 卷号(期号): 起始页码-结束页码.

例如:

王明, 李华, 赵丽. 量子通信的新进展. 科学通报, 2021, 66(12): 1234-1256.

书籍:

作者. 书名. 版本(初版可省略). 出版地: 出版社, 出版年份.

例如:

张三. 物理学导论. 第3版. 北京: 高等教育出版社, 2018.

学位论文:

作者. 论文标题. 学位级别. 授予单位, 年份.

例如:

李四. 量子计算的研究. 博士学位论文. 清华大学, 2022.

请注意,具体的引用格式可能会根据期刊或出版机构的要求有所不同,因此在撰写论文时应参照目标期刊或出版社的投稿指南进行调整。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

ENVIRONMETRICSEnvironmetrics 2006;17:623–633Published online in Wiley InterScience ().DOI:10.1002/env.768Probabilistic risk assessment for wildfires zD.R.Brillinger 1,*,y ,H.K.Preisler 2and J.W.Benoit 31Statistics Department,University of California,Berkeley,CA 94720-3860,U.S.A.2Pacific Southwest Research Station,USDA Forest Service,Albany,CA 94710,U.S.A.3Pacific Southwest Research Station,USDA Forest Service,Riverside,CA 92507,U.S.A.SUMMARYForest fires are an important societal problem.They cause extensive damage and substantial funds are spent preparing for and fighting them.This work develops a stochastic model useful for probabilistic risk assessment,specifically to estimate chances of fires at a future time given explanatory variables.Questions of interest include:Are random effects needed in the risk model?and if yes,How is the analysis to be implemented?An exploratory data analysis approach is taken using both fixed and random effects models for data concerning the Federal Lands in the state of California during the period 2000–2003.Published in 2006by John Wiley &Sons,Ltd.key words :biased sampling;false discovery rate;forest fires;generalized mixed model;penalized quasi-likelihood;risk1.INTRODUCTIONThe concern of the work is wildfires in the Federal Lands of California.A previous paper (Brillinger et al .,2004)was concerned with the same problems but for the case of Oregon.For comparative purposes,this paper parallels it to a close extent.The goal is to estimate probabilities associated with the occurrence of wildfires,for example,the probability that a fire might occur in a specified region during some given day,week,or month of the year.Explanatory variables such as elevation and fire danger indices are available.In particular,one may wish to estimateProb f fire in particular region and time period j explanatories gwhere the (future)time period may be short or long term.Various sources of variability arise.One follows from the response,Y ,being binary and Bernoulli distributed.Another follows from the year to Received 29October 2004Published in 2006by John Wiley &Sons,Ltd.Revised 14July 2005*Correspondence to:D.R.Brillinger,Statistics Department,University of California,367Evans,Berkeley,CA 94720-3860,U.S.A.y E-mail:brill@ z This article is a ernment work and is in the public domain in the U.S.A.Contract/grant sponsor:NSF;contract/grant number:DMS-02-03921.Contract/grant sponsor:U.S.Forest Service;contract/grant number:02-JV-11272165-02.year changes.The latter is dealt with here by introducing a random effect,I ,for year.One then wishes an estimate ofE I f Prob f fire in particular region and time period j explanatories ;I ggSpatial and daily (fixed)effects are included in the model as smooth additive functions g 1ðx ;y Þand g 2ðd Þ,respectively of space ðx ;y Þand day of the year d .The year effect,I ,is also additive to the linear predictor.An estimate of var f I g is obtained via quasi-likelihood estimation.Figure 1shows the basic data in a derived form.Figure 1(a)gives the locations of all of the fires in the data set.Figure 1(b)gives the daily totals over the 4years.The latter appears as a smooth curve plus quite a number of larger outliers in the summer fire season.As an example of projecting daily counts the Yosemite National Forest is considered.2.STATISTICAL BACKGROUNDThe model used is a particular case of the generalized mixed effects model,for example (Breslow and Clayton,1993).The vector Y ,and the matrices X and Z are given.The linear predictor takes the form¼X þZbFigure 1.(a)Fire locations;the blocked off upper right area is the state of Nevada;(b)4-year total for each day of the year 624 D.R.BRILLINGER,H.K.PREISLER AND J.W.BENOITPublished in 2006by John Wiley &Sons,Ltd.Environmetrics 2006;17:623–633RISK ASSESSMENT625 with the vector fixed and the random vector b normal with mean0and covariance matrix R.Further there exists an inverse link function h such thatE f Y j b g¼hð ÞIt is also assumed thatvar f Y j b g¼vð Þwith v a known function.These assumptions may be used to set down a penalized quasi-likelihood function(Green1987; Schall1991;Breslow and Clayton,1993)and an iterative scheme may be set up to evaluate the parameters.The function glmmPQL()of Venables and Ripley(2002),which uses the linear mixed effects function lme()of Pinheiro and Bates(2000),is used in the computations presented below.The estimates obtained may be used in turn to estimate E f b j Y g.A common alternative to attacking the model directly is to use afixed effects procedure and take the random effects as parameters and then compute the sample variance of the estimates obtained.In Sub-section4.1below the false discovery rate(FDR)is used to describe the certainty of an estimated spatial effect.A null hypothesis that there is no spatial effect is considered.The FDR is defined as the fraction of false rejections of the null hypothesis among all rejections.It is useful here because hypotheses are being examined for each spatial pixel.There are various FDR procedures for controlling the indicated rate.The one used here is due to Benjamini and Yekutieli(2001).3.THE CASE OF CALIFORNIAThefires studied occurred in California Federal lands during the period2000–2003.These lands make up an important part of the state.Data for the full year were used.Spatial pixels that were1km by1km were used.This meant that the data set was very large.Because of this only a sample of the locations where nofires occurred was used.All the space-time cells(voxels)withfires were included.For each day a sample of voxels with nofires was taken.The number of voxels sampled each day was proportional to the total number offires on that day,proportional to a smoothed version of Figure1b.Having in mind the problem and the data available,a number of models may be considered.Set Y¼1;0according to whether there has been afire or not in a particular spatial pixel and time period. Suppose,to begin,that thefixed explanatories used are location,ðx;yÞ,and day of the year,d.The further explanatory year,I,is taken asfixed in Model II and random in Model III below.In the models,g1and g2are respectively smooth splines for location and day of the year. Model I:With Y,binary-valued andðx;yÞand dfixedlogit Prob f Y¼1j x;y;d g¼g1ðx;yÞþg2ðdÞð1ÞModel II:With I,afixed factor for yearlogit Prob f Y¼1j x;y;d;I g¼g1ðx;yÞþg2ðdÞþIð2ÞModel III:With I,a factor whose effects are independent normals with mean0and variance(2logit Prob f Y¼1j x;y;d;I g¼g1ðx;yÞþg2ðdÞþIð3ÞPublished in2006by John Wiley&Sons,Ltd.Environmetrics2006;17:623–633Writing¼g1ðx;yÞþg2ðdÞfor Model III,and assuming I to be normal,the probability of afire isProb f Y¼1j explanatories g¼Zexp f þ(z gð1þexp f þ(z gÞ0ðzÞd zwith0ð:Þthe density function of the standard normal.The distribution of Y in Model III is logit-normal.An added detail of the current set up is that the no-fire cases were sampled.Interestingly,with the logit link,one has a generalized linear model with an offset of logð1=%Þ.The new logit is simply logit p0¼logit pþlogð1=%Þ,i.e.,an offset.One reference is Maddala(1992,p.330).This meantthat Figure2.The estimated spatial and daily effects for Model I,(a)Provides an image plot of the estimated spatial effect.The darker values correspond to increasedfire risk.In(b),the vertical lines provide approximate95%confidence limits about asmoothed version of the solid line626 D.R.BRILLINGER,H.K.PREISLER AND J.W.BENOITPublished in2006by John Wiley&Sons,Ltd.Environmetrics2006;17:623–633standard generalized linear model computer programs could be used for the analysis.The offset is not indicated in expressions(1),(2),or(3)as they are the basic models.4.RESULTS4.1.Fitting and assessing Models I and IIModel I involvesfitting the sum of smooth functions,specifically splines,ofðx;yÞand d.Figure2 shows thefitted spatial and day effects.Figures2(a)and2(b)look like smoothed version of Figure1. Figure2(b)shows thefitted effect of day as a solid curve.The effect is seen to peak around day200and be smaller for September through April.The vertical lines about the curve provide approximate95% marginal confidence limits graphed about a smoothed form of^g2ðdÞ.The limits were computed via a jackknife dropping years in turn.Figure3(a)provides the estimated spatial effect in contour form.As in Figure2(a)one notes reduced risk in the eastern and western parts of the state.Figure3(b)shows the results of controlling the overall FDR at level0.01.There is strong evidence for a spatial effect around much of the region of study.Projections of future counts are of basic interest in this work,for example,the expectedfire count for a given region and months.To obtain these,one sums probabilities over pixels of the selected region,and days of the year,specifically one computesX iexp f^ i gð1þexp f^ i gÞð4Þwhere i sums over the pixels in the region,the days of the selected month and^ i¼^g1ðx i;y iÞþ^g2ðd iÞAs an example,predictions are presented for the Yosemite National Park in the Federal Lands of California.Figure4provides estimates of the expected count offires for Yosemite National Park each month derived via expression(4).(Yosemite is indicated by the dot in the left-hand panel of Figure3(a).)One sees the expected count peaking,just below a level of34fires,in July.The distribution of a future count can be approximated by a Poisson with the indicated estimated expected count.4.2.Results offitting Model IIINext consideration turns to Model III,i.e.,including a random effect for year.Thefitting is carried out via penalized quasi-likelihood implemented as the function glmmPQL(),(Venables and Ripley,2002).Doing so,one obtains for the standard error of the year effect ^(¼0:157.The program output also includes X =ffiffiffin p ¼1:062,where X is square root of the estimate of the dispersion statistic.This value suggests that the logistic-normal model is fitting the data rather well.Figure 5shows the estimated daily effects.There are not great changes from the Model I results presented in Figure 2(a).An estimate of the expected number of fires for some region and future occasion is provided byX i Zexp f ^ i þ^(z g ð1þexp f ^ i þ^(z gÞ0ðz Þd z ð5Þwith i again labeling the pixels of the region of concern and the days of the month,and ^i ¼^g 1ðx i ;y i Þþ^g 2ðd i Þ.The integral in expression (5)is evaluated numerically and the results are given in Figure 6a.Uncertainties may be derived via the jackknife splitting on year.In some circumstances an estimate ofProb f At least one fire in a particular region and monthgFigure 5.The estimated daily effects for Model IIIRISK ASSESSMENT 629Published in 2006by John Wiley &Sons,Ltd.Environmetrics 2006;17:623–633is desired.With an approximate Poisson process of intensity offires"ðx0;y0;d0Þ,and a region M this probability is given by1ÀexpÀZM "ðx0;y0;d0Þd x0d y0d d0whose integrand may be approximated by expression(4).The results are given in Figure6(b). Figure6(a)may be compared with Figure4.The two are very similar.It may be noted that^(is small, 0.157.Figure7gives estimates of the random year effects,that is E f I j data g for each of the of the years 2000–2003.Such effects are sometimes referred to as shrunken effects.4.3.Model assessmentThe response is binary,Y¼0;1and so various of the classical model effect procedures are not particularly effective.However,uniform residuals are an aid to assessing goodness offit,in varioussuch nonstandard cases,(Brillinger and Preisler,1983;Brillinger,1996).In the binary case,these may be computed as follows:suppose Prob f Y¼1j explanatories g¼ and that U1and U2denote independent uniforms on the intervalsð0;1À Þ;ð1À ;1Þ,respectively,then the variateU¼U1Âð1ÀYÞþU2ÂYhas a uniform distribution on the intervalð0;1Þ.Whereas when Prob f Y¼1j explanatories g¼ 0,then E f U g¼ð1þ À 0Þ=2for example.We refer to U,when an estimate of^ is used,as a uniform residual and write^U.We refer toÈÀ1ð^UÞas a normal residual.Working with the normal residuals has the advantage of spreading the values out.Various traditional residual plots may now be constructed, for example normal probability plots involving the normal residualsÈÀ1ð^UÞor plots ofÈÀ1ð^UÞversus explanatories.The right-hand panel of Figure8shows notched boxplots of the normal residuals of Model I against the year.The graph suggests that year need not be in the model as an explanatory.The left-hand panel provides a normal probability plot and there appears not much to be concerned with.Figure9provides similar plots for Model III,but now the explanatory in the right-hand panel is elevation.Again there is little indication that this explanatory need be included.The left-hand showslittle evidence against the distributional assumptions made.boxplots for each year’s normal residuals.The notches are very small hereRISK ASSESSMENT6335.SUMMARY AND DISCUSSIONTwo distinct models,onefixed effect and the other random effect,have been set down and studied. Theirfit has been assessed by probability and residual plots.One question in the work was whether a random effect was in fact needed.An answer to this is:yes, the context of the situation and the desire for estimates of future probabilities more or less guarantees so.It was noted how close the estimate of the random effect variance derived fromfixed effect modeling was to that based on random effects modeling.Turning to the promised comparisons with the Oregon results,the same methodology appears to work equally well with both the California and Oregon data.The work that has been presented is preliminary and exploratory.It is meant to lead to possible approaches in the full modeling effort.Further details of the approach may be found in Brillinger et al.(2003)and Preisler et al.(2004). This work parallels that of Brillinger et al.(2004)and Preisler and Benoit(2004)closely.REFERENCESBenjamini Y,Yekutieli D.2001.The control of false discovery rate in multiple testing under dependency.Annals of Statistics29: 1165–1188.Breslow NE,Clayton DG.1993.Approximate inference in generalized linear models.Journal of American Statistical Association88:9–25.Brillinger DR,Preisler HK,Benoit JW.2003.Risk assessment:a forestfire example.Statistics and Science:A Festschrift for Terry Speed.V ol.40IMS Lecture Notes;177–196.Brillinger DR,Preisler HK,Naderi HM.2004.Wildfire chances and probabilistic risk assessment.In Proceedings of the Sixth International Symposium on Spatial Accuracy Assessment in Natural Resource and TIES,Portland Maine,USA. Brillinger DR,Preisler HK.1983.Maximum likelihood estimation in a latent variable problem.Studies in Econometrics,Time Series and Multivariate Statistics.Academic Press:New York;31–65.Brillinger DR.1996.An analysis of an ordinal-valued time series.In Lecture Notes in Statistics,V ol.115.Springer:New York. Green PF.1987.Penalized likelihood for general semi-parametric regression models.International Statistical Review55:245–259.Maddala GS.1992.Introduction to Econometrics(2nd edn).MacMillan:New York.Pinheiro JC,Bates DM.2000.Mixed-effects Models in S-PLUS.Springer:New York.Preisler HK,Benoit JW.2004.A state space model for predicting wildlandfire risk.In Proceedings of the Joint Statistics Meetings,Toronto.Preisler HK,Brillinger DR,Burgan RE,Benoit JW.2004.Probability based models for estimating wildfire risk.International Journal of Wildland Fire13:133–142.Schall R.1991.Estimation in generalized linear models with random effects.Biometrika78:719–727.Venables WN,Ripley BD.2002.Modern Applied Statistics with S(4th edn).Springer:New York.Published in2006by John Wiley&Sons,Ltd.Environmetrics2006;17:623–633。