刘精明_转型期城镇收入分配中的国家规制(英文)

政府规制理论

政府规制理论内容提要❑政府调节经济,以矫正市场失灵,它所采用的最惯常的手段就是经济政策。

❑微观经济政策是针对市场秩序和企业的,常用的手法就是规制。

❑宏观经济政策主要包括货币政策、财政政策、产业政策、收入政策以及在一定程度上实现国民经济的计划化。

❑本篇分析政府规制、财政政策、货币政策。

第九章政府规制主要内容❑政府规制的内容与方法❑政府规制失灵与规制的放松❑了解政府规制的过程背景知识:规制经济学“规制”(“Regulation”),是规制部门通过对某些特定产业或企业的产品定价、产业进入与退出、投资决策、危害社会环境与安全等行为进行的监督与管理。

实践中,无论发达国家还是发展中国家,对特定产业的规制已成为普遍的政府行为。

经济性规制与社会性规制依据规制性质的不同,规制可分为经济性规制与社会性规制。

经济性规制主要关注政府在约束企业定价、进入与退出等方面的作用,重点针对具有自然垄断、信息不对称等特征的行业。

社会性规制是以确保居民生命健康安全、防止公害和保护环境为目的所进行的规制,主要针对与对付经济活动中发生的外部性有关的政策。

规制经济学规制经济学是对政府规制活动所进行的系统研究,是产业经济学的一个重要分支。

对规制经济理论的研究主要分为两大派别:规制规范分析与规制实证分析。

代表人物规制规范分析学派产生于十九世纪,主要代表人物有查得威克、马歇尔、庇古、德姆塞茨、威廉姆森等。

规制实证分析学派萌芽于十九世纪法国经济学家迪普特(Dupuit,1849)的研究,在20世纪六十年代发展壮大,主要代表人物有斯蒂格勒、卡恩、帕尔兹曼、贝克尔等。

规制规范分析学派主要观点:由于市场机制不完善及存在市场失灵,如自然垄断、外部性等,因此应对企业活动进行规制,规制的目的是在确保资源配置效率情况下,保证公共利益不受损害。

规制实证分析学派主要观点:政府规制的目的并非是保护公共利益,而是为维护个别集团的利益,在规制者与被规制者之间的相互利用,并通过经验数据分析,佐证了所提出的观点。

环境规制、企业成本负担与劳动收入份额

环境规制、企业成本负担与劳动收入份额目录一、内容描述 (2)1.1 研究背景与意义 (3)1.2 文献综述 (4)1.3 研究方法与数据来源 (5)二、环境规制与企业成本负担 (6)2.1 环境规制的概念与类型 (7)2.2 环境规制对企业成本的影响机制 (9)2.3 行业差异与环境规制的成本效应 (10)2.4 政策背景与实践 (12)三、劳动收入份额的测度与分析 (13)3.1 劳动收入份额的测度方法 (15)3.2 劳动收入份额的变化趋势 (16)3.3 影响劳动收入份额的关键因素 (18)3.4 不同群体的劳动收入份额比较 (19)四、环境规制、企业成本负担与劳动收入份额的关系 (20)4.1 环境规制对劳动收入份额的直接影响 (22)4.2 环境规制通过企业成本负担间接影响劳动收入份额 (22)4.3 政策建议与实证检验 (23)五、结论与展望 (24)5.1 研究结论 (26)5.2 政策建议 (27)5.3 研究局限与未来展望 (28)一、内容描述本文档主要探讨环境规制、企业成本负担与劳动收入份额之间的关系。

随着环境保护意识的加强和环保法规的严格实施,环境规制对企业成本负担和劳动收入份额的影响日益凸显。

研究这一问题具有重要的理论和实践意义。

环境规制作为企业外部约束条件之一,对企业的生产经营活动产生直接影响。

环境规制政策的实施会导致企业面临更高的环境治理成本,进而影响企业的成本结构和竞争力。

企业需要投入更多的资金和资源来遵守环保法规,这将增加企业的成本负担。

环境规制与企业成本负担之间存在密切关系。

企业成本负担的变化会对劳动收入份额产生影响,当企业面临更高的成本负担时,为了保持盈利和竞争力,企业可能会采取一系列措施来降低成本,其中包括调整劳动力成本。

这可能导致企业降低工资水平或减少劳动力投入,进而影响劳动收入份额。

环境规制、企业成本负担与劳动收入份额之间存在一定的关联。

本文旨在通过分析环境规制政策的实施情况、企业成本负担的变化以及劳动收入份额的变动,探讨三者之间的内在联系和影响因素。

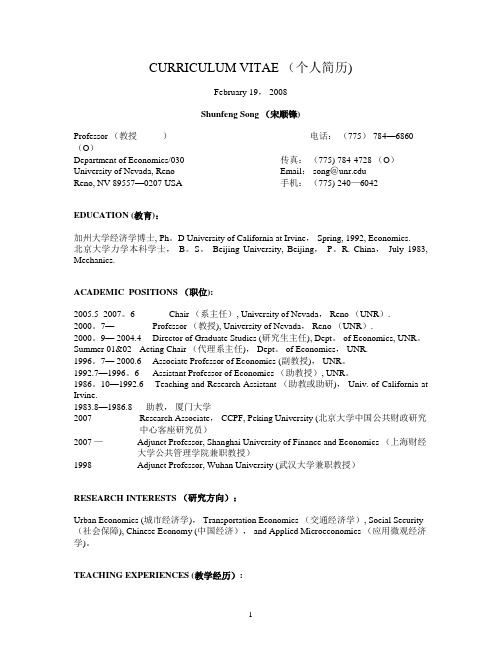

Curriculum Vitae (个人简历)

CURRICULUM VITAE (个人简历)February 19, 2008Shunfeng Song (宋顺锋)Professor (教授)电话:(775) 784—6860 (O)Department of Economics/030 传真:(775) 784-4728 (O)University of Nevada, Reno Email: song@Reno, NV 89557—0207 USA 手机:(775) 240—6042EDUCATION (教育):加州大学经济学博士, Ph。

D University of California at Irvine, Spring, 1992, Economics.北京大学力学本科学士,B。

S。

Beijing University, Beijing,P。

R. China,July 1983, Mechanics.ACADEMIC POSITIONS (职位):2005.5- 2007。

6 Chair (系主任), University of Nevada, Reno (UNR).2000。

7— Professor (教授), University of Nevada, Reno (UNR).2000。

9— 2004.4 Director of Graduate Studies (研究生主任), Dept。

of Economics, UNR。

Summer 01&02 Acting Chair (代理系主任), Dept。

of Economics, UNR.1996。

7— 2000.6 Associate Professor of Economics (副教授), UNR。

1992.7—1996。

6 Assistant Professor of Economics (助教授), UNR。

1986。

10—1992.6 Teaching and Research Assistant (助教或助研), Univ. of California at Irvine.1983.8—1986.8 助教,厦门大学2007 - Research Associate, CCPF, Peking University (北京大学中国公共财政研究中心客座研究员)2007 — Adjunct Professor, Shanghai University of Finance and Economics (上海财经大学公共管理学院兼职教授)1998 - Adjunct Professor, Wuhan University (武汉大学兼职教授)RESEARCH INTERESTS (研究方向):Urban Economics (城市经济学), Transportation Economics (交通经济学), Social Security (社会保障), Chinese Economy (中国经济), and Applied Microeconomics (应用微观经济学)。

我国海运碳排放市场机制构建的进路统筹

第32卷㊀第1期太㊀㊀平㊀㊀洋㊀㊀学㊀㊀报Vol 32,No 12024年1月PACIFICJOURNALJanuary2024DOI:10.14015/j.cnki.1004-8049.2024.01.006曹兴国: 我国海运碳排放市场机制构建的进路统筹 ,‘太平洋学报“,2024年第1期,第72-85页㊂CAOXingguo, CoordinationofApproachestotheConstructionofMarket-BasedMechanismofMaritimeCarbonEmissionsinChina ,PacificJour⁃nal,Vol.32,No.1,2024,pp.72-85.我国海运碳排放市场机制构建的进路统筹曹兴国1(1.大连海事大学,辽宁大连116026)摘要:海运碳减排需要统筹运用包括市场机制在内的多种措施㊂欧盟推进单边海运碳排放交易机制虽然对市场机制在海运领域的运用具有正向推进价值,但基于其制度对共同但有区别责任原则的忽视等原因,与我国的航运利益并不相符㊂我国应当联合其他非欧盟国家反对欧盟的单边措施,并积极推进国际海事组织(IMO)层面多边海运碳排放市场机制的构建,推动海运碳排放真正实现公正公平的过渡㊂同时,在国内层面,基于国际国内统筹推进的整体要求,我国需要厘定基于国内立法的海运碳排放市场措施及其实施路径,构建相应的制度保障㊂关键词: 双碳 目标;海运碳排放;市场机制;共同但有区别责任原则;非更优惠待遇原则中图分类号:D920㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀文献标识码:A㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀文章编号:1004-8049(2024)01-0072-14收稿日期:2023⁃07⁃27;修订日期:2023⁃09⁃20㊂基金项目:本文系辽宁省社科基金项目 海运碳减排市场机制构建的制度协同研究 (L22CFX004)的阶段性研究成果㊂作者简介:曹兴国(1989 ),男,浙江绍兴人,大连海事大学法学院副教授㊁硕士生导师,法学博士,主要研究方向:海商法㊁国际法㊂∗作者感谢‘太平洋学报“编辑部匿名审稿专家提出的建设性修改意见,感谢孙爱迪在本文写作过程中的协助,文中错漏由笔者负责㊂①㊀2018年4月通过的船舶温室气体减排初步战略中提出的减排目标为:以2008年碳排放为基准,到2030年将海运业碳排放强度降低40%,到2050年碳排放强度降低70%(碳排放总量降低50%)㊂㊀㊀随着我国 双碳 目标的确立,碳排放治理已经不折不扣地成为我国生态文明建设以及参与国际气候治理的重要议题㊂海运业同样需要承担减排任务,并已在国际海事组织(以下简称IMO)的推进下取得积极进展㊂2022年,IMO海上环境保护委员会第76次会议(MEPC76)通过了‘国际防止船舶造成污染公约“(MARPOL公约)附则VI 关于降低国际航运碳强度 的修正案,通过现有船舶能效指数(EEXI)和碳强度指标(CII)评级机制对船舶的最低能效标准和营运的碳强度作出限制和评价,旨在从技术和运营两个方面提高船舶能效,降低碳强度水平㊂同时,2023年7月,IMO海上环境保护委员会第80次会议通过重新修订 船舶温室气体减排战略 ,进一步明确了以2008年为参照,国际海运温室气体年度排放总量到2030年至少降低20%,并力争降低30%;到2040年降低70%,并力争降低80%的减排新目标㊂①上述减排目标的实现,需要依赖一系列的减排措施,包括碳排放市场机制㊂所谓碳排放第1期㊀曹兴国:我国海运碳排放市场机制构建的进路统筹市场机制,亦可称为碳定价机制,其理念在于将碳排放权作为一种资源并对其定价,通过构建市场化机制解决碳排放的外部不经济性,从而实现减排目标㊂在过去,海运业因其显著的国际性和机制适用的复杂性,大多被排除在各国的碳排放市场机制之外㊂但2023年5月,欧盟通过2023/959号指令对欧盟碳排放交易体系指令进行修订,正式将海运业纳入欧盟碳排放交易体系㊂同时,在重新修订的IMO 船舶温室气体减排战略 中,也明确要求包括市场机制在内的一揽子中期减排措施应当在2025年确定并通过㊂①显然,在欧盟和IMO的推动下,海运碳排放市场机制的构建将大大提速,并引发单边及多边层面的连锁反应㊂海运碳排放市场机制的构建不仅关乎所有海运参与主体的利益,而且机制构建中的规则话语权争夺更关乎各国在海运相关产业的切实利益,影响未来的海运竞争格局㊂尤其在欧盟通过内部立法单边推动海运碳排放市场机制实施的背景下,海运碳排放市场机制的构建在某种程度上已经被 裹挟 ,其推进势在必行㊂因此,无论是主动引领还是被动参与,海运碳排放市场机制的构建是各国㊁各利益方都需要谋划和应对的重要议题㊂对我国而言,海运碳排放市场机制的构建是一个重要又复杂的议题,面临诸多挑战㊂首先,欧盟的单边海运碳排放交易机制将对我国航运业产生直接影响,我国如何开展有效应对亟需回应㊂其次,IMO主导下的多边市场机制构建仍面临不少分歧 选择何种市场机制方案,如何体现共同但有区别责任原则,通过何种方式实施等都有待细化讨论㊂此外,海运碳排放市场机制的构建不仅是国际层面的应对,我国也应当在国内层面以国际国内统筹推进为指引,统筹国内机制的构建㊂因此,海运碳排放市场机制的构建需要多个层面的进路统筹㊂本文旨在通过分析我国在双边㊁多边以及国内三个层面应对㊁参与㊁构建海运碳排放机制的需求和立场,探讨我国的应对策略和制度路径㊂一㊁海运碳排放市场机制的单边进路应对㊀㊀海运是一个高度国际化的行业㊂理想状态下,应当通过多边协调来推进海运碳排放市场机制的构建,但因多边层面协商进度不及预期,以欧盟为代表的单边行动已经着手推进海运碳排放机制的构建㊂1.1 以欧盟为代表的单边市场机制推进欧盟是碳排放市场机制的忠实推动者,其构建的碳排放交易体系被视为欧盟最主要的气候政策工具㊂欧盟的碳排放交易体系以2003年的‘欧盟排放权交易体系指令“为基础法律架构,后经多次修正㊂当前,欧盟碳排放交易体系的运行已经进入第四阶段,即以欧盟委员会在2021年7月发布的一系列气候计划与提案(Fitfor55)为依托,大幅提升碳市场的减排目标,并扩大覆盖的行业领域㊂海运业就属于此阶段扩大覆盖的行业领域范围之列㊂根据欧盟2023/959号指令,主管机关②将对5000总吨以上船舶在欧盟内部的港口之间整个航程100%的排放量,以及欧盟与非欧盟港口之间航程50%的排放量③收取排放配额㊂负责配额缴纳的责任主体为船公司,包括船东或从船东处承担船舶运营责任㊁并同意承担‘国际船舶安全运营和防止污染管理规则“规定的所有职责和责任的任何其他组织和个人(例如船舶管理人㊁光船承租人)㊂为了给机制的适用提37①②③IMO, 2023IMOStrategyonReductionofGHGEmissionsfromShips ,ResolutionMEPC.377(80),July7,2023,https://ww⁃wcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/OurWork/Environment/Documents/annex/2023%20IMO%20Strategy%20on%20Reduction%20of%20GHG%20Emissions%20from%20Ships.pdf,para.6.对于欧盟注册的船公司,其主管机关为船公司注册地所在的成员国;非欧盟注册的船公司,其主管机关为最近4个监测年度内停靠港口次数最多的成员国;而对于非欧盟注册且最近4个监测年度内也没有停靠过欧盟港口的公司,则其主管机关为该公司旗下船舶在欧盟境内抵达或开始其首个航程的成员国㊂纳入排放量计算的气体包括二氧化碳㊁甲烷和一氧化二氮㊂其中,甲烷和一氧化二氮将于2024年后纳入欧盟2015/757号条例,从2026年起纳入欧盟排放交易体系㊂太平洋学报㊀第32卷供一定的缓冲空间,指令规定了两年的过渡期:2024年和2025年分别纳入40%和70%的航运排放量,到2026年将纳入100%的航运排放量㊂同时,为防止班轮集装箱船舶利用挂靠港口的安排来规避机制的适用,该指令将建立一份位于欧盟以外,但距离某一成员国管辖港口不到300海里的相邻集装箱转运港口名单㊂船舶在名单中的港口进行的转运将不被计为与上一个非名单中转运港之间航程的中断㊂对于未能在每年9月30日前缴纳前一年排放配额的船公司,将面临每个未缴纳的排放配额(每吨二氧化碳当量的排放)100欧元的罚款㊂1.2 单边进路的辩证评估欧盟是当前世界三大海运市场之一,其海运碳排放政策措施将产生重大影响㊂这种影响,最直接地体现为航运公司的费用增加 据测算,如果按照每个碳排放配限额(EUA)90欧元的市价计算,预计海运业在2024年㊁2025年㊁2026年可能要分别承担高达31亿欧元㊁57亿欧元和84亿欧元的费用㊂①而在这些费用之外,欧盟单边进路的其他影响同样显著㊂(1)对海运碳排放市场机制构建的正向推动欧盟之所以决定率先将海运业纳入欧盟碳排放交易机制,一个重要的背景就是欧盟认为IMO层面的市场机制谈判虽有进展,但仍不足以实现巴黎协定确定的目标㊂因此,欧盟的单边立法固然有其实现自身减排战略的考虑,但也在很大程度上希望籍此反推和倒逼多边进程㊂IMO在随后通过经修订的减排战略,并明确将市场机制作为一揽子中期措施的一部分,也不无欧盟立法进程的影响㊂正如学者所言,相比于多边层面的谈判,打补丁式的单边路径(patchworkapproach)有时更有效,因为它可以破解多边协同的困境㊂而且,通过部分国家或者地区先行的政策探索和行业反馈,可以为多边层面更大规模的政策应用提供数据和证据支撑㊂②同时,依托在碳排放交易领域的实践经验,欧盟所构建的海运碳排放交易制度也确有其可取之处㊂首先,欧盟在制度方案上考虑了未来与IMO多边机制的协调问题㊂根据指令,如果未来IMO通过了多边市场机制,欧盟将根据IMO市场机制的内容㊁效果以及与欧盟机制的一致性等对本指令的内容重新进行评估,尽量避免对船公司的双重负担;如果IMO在2028年仍未采取全球市场措施,欧盟委员会应向欧洲议会和理事会提交一份报告,审查对欧盟港口与非欧盟港口之间航程超过50%部分的排放量是否需要实施配额分配和交易㊂其次,欧盟在将海运纳入碳排放交易体系时,吸收了当初将航空纳入碳排放交易体系的失败教训,③在此次针对海运的方案设计中做了不少调整㊂其中最显著的一点就是仅将进出欧盟港口的国际航程的50%排放量纳入,而非此前航空领域的全部排放量,试图以此缓和其他国家的抵制㊂最后,从制度的完整性上,欧盟的海运碳排放交易制度在既有碳排放交易制度的基础上做了很多细化的补充,形成了一套相对完整㊁具有可操作性的海运碳排放市场制度㊂例如为保障制度的执行,指令明确规定欧盟成员国可以拒绝不履行义务的船公司的船舶进入其港口,同时作为船旗国的欧盟成员国可以对当事船舶进行扣押㊂④因此,无论是否采取与欧盟一样的碳排放交易机制,欧盟海运碳排放交易制度的制度内容都或多或少地能对IMO和其他国家构建多边或者单边的海运碳排放市场机制带来参考价值㊂47①②③④ 欧盟碳排放交易体系生效后2024年航运业将承担30多亿欧元费用 ,新浪财经网,2023年7月7日,https://finance.sina.com.cn/esg/2023-07-07/doc-imyzwcer8222804.shtml㊂ZhengWan,etal., DecarbonizingtheInternationalShippingIndustry:SolutionsandPolicyRecommendations ,MarinePollutionBulletin,Vol.126,2018,p.433.欧盟曾在2008年通过2008/101/EU号指令,计划自2012年起将抵达或离开欧盟成员国境内机场的所有航班的碳排放纳入欧盟碳排放交易体系,但该计划因受到国际社会普遍的抵制而最终搁浅㊂Directive(EU)2023/959oftheEuropeanParliamentandtheCouncilofTheEuropeanUnionof10May2023 ,OfficialJournaloftheEuropeanUnion,May16,2023,https://eur-lex.europa.eu/le⁃gal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32023L0959,para.34.第1期㊀曹兴国:我国海运碳排放市场机制构建的进路统筹(2)对制度话语权的争夺在肯定欧盟单边进路积极价值的同时,我们同样需要认识到欧盟单边举措的政治意图,即对海运碳排放市场机制构建的话语权争夺,以及在此过程中的理念输出㊂事实上,提升欧盟在国际政治中的形象㊁维护欧盟的国际地位㊁占据国际道义的制高点,一直是欧盟推行积极的国际气候政策的根本目的㊂①具体而言,欧盟在海运领域推行碳排放交易制度的话语权导向最显著地体现在其对非更优惠待遇原则(NoMoreFavourableTreatment,NMFT)的贯彻上㊂非更优惠待遇原则强调所有的措施应当无差别地适用于所有国家的船舶,这显然与发展中国家在气候治理领域所主张的共同但有区别责任原则(CommonButDifferenti⁃atedResponsibility,CBDR)存在根本分歧,这也是发展中国家和发达国家在多边层面海运碳排放治理中一直争论㊁并阻碍减排共识达成的重要问题㊂②作为发达国家集团的代表,欧盟在其海运碳排放交易的制度方案中充分体现了其立场,将非更优惠待遇原则作为制度基础,未对发展中国家做任何特殊安排㊂非更优惠待遇原则是此前IMO公约普遍遵循的原则,主张其在碳减排领域适用的主要理由在于 方便旗 船屡见不鲜,船东的国籍可能与船舶的船旗国并不相同,船舶加油㊁运营和航行海域也可能分属不同国家,因而船旗国㊁燃料出售国㊁始发港㊁目的港或中转港所在国㊁货物生产国或消费国等都可以认为参与了温室气体排放,难以区别不同国家设定不同的减排标准㊂同时,鉴于国际海运产生的温室气体排放大部分发生在主权国家领土以外即公海上,按不同类型国家分别对海运碳减排以不同标准进行调整也是不合适的㊂③然而,严格强调该原则无疑也将忽视发达国家在气候治理领域的历史责任,忽视了中国等发展中国家作为新兴海运大国,其海运碳排放更多是 生存和发展性排放 的事实㊂此外,欧盟在海运领域适用碳排放交易制度,也会将欧盟碳排放交易制度本身追求国际话语权的一些内容带到海运领域㊂例如,通过倡导碳排放权交易机制的连接,欧盟不仅可以运用碳排放权交易规则影响其他国内碳排放权交易规则的制定,也可以随着连接规模的不断扩大,提升其碳排放权交易规则的国际化程度,最终从事实上上升为国际碳排放权交易规则㊂④1.3 我国应对单边市场机制的立场与措施欧盟雄心勃勃的海运碳排放交易制度与我国的海运利益并不相符㊂这种不相符性主要表现为欧盟的制度方案对共同但有区别责任原则的忽视与我国的一贯主张不符,也与我国海运业的发展利益不符㊂从运量的角度来看,海运中心东移已是不争的事实,现阶段对海运碳排放的控制主要限制的是包括我国在内的诸多新兴发展中国家海运业的未来发展空间㊂如果不顾历史事实和不同国家所处的发展阶段,苛求发展中国家在海运碳减排上承担与发达国家相同的责任,这对于发展中国家是不公平的㊂碳排放权是一种新的发展权,尤其在碳排放权分配方案的制定中应当考虑发展需求㊁人口数量㊁历史责任㊁公平正义原则等因素㊂⑤因此,我国历来主张碳减排遵循人际公平原则应贯穿历史和未来,既强调代内公平,也强调代际公平,各国所获得的碳排放权应受到其历史排放水平和人口数量的影响㊂⑥同时,我国海运业虽然在规模上已经处于世界前列,但现阶段凭既有技术和规模优势积累的行业优势很容易被新的技术和政策要求所57①②③④⑤⑥巩潇泫: 多层治理视角下欧盟气候政策决策研究 ,山东大学博士论文,2017年,第52页㊂YubingShiandWarwickGullett, InternationalRegulationonLow-CarbonShippingforClimateChangeMitigation:Development,Challenges,andProspects ,OceanDevelopment&InternationalLaw,Vol.49,No.2,2018,p.145.Jae-GonLee, InternationalRegulationsofGreenhouseGasEmissionsFromInternationalShipping ,Asia-PacificJournalofOceanLawandPolicy,Vol.4,No.1,2019,pp.53-78.参见赵骏㊁孟令浩: 我国碳排放权交易规则体系的构建与完善 基于国际法治与国内法治互动的视野 ,‘湖北大学学报“(哲学社会科学版),2021年第5期,第126页㊂参见杨泽伟: 碳排放权:一种新的发展权 ,‘浙江大学学报“(人文社会科学版),2011年第3期,第40-47页㊂参见王文军㊁庄贵阳: 碳排放权分配与国际气候谈判中的气候公平诉求 ,‘外交评论“,2012年第1期,第80页㊂太平洋学报㊀第32卷稀释甚至抹杀㊂例如我国传统造船业较为发达,而绿色低碳等新技术领域的造船仍有较大欠缺,结构性不平衡问题较为突出㊂①这意味着过去我们在传统造船领域的优势很可能将因为碳减排的新要求而遭到削弱㊂因此,与发达国家一样无差别地承担碳减排任务对我国海运业来说挑战大于机遇㊂而且我国与欧盟在碳排放市场机制建设上的理念和阶段差异,包括总量控制㊁配额分配方式㊁运行和交易管理等方面的差异,也决定了现阶段我国不可能跟随欧盟海运碳排放交易制度的步伐㊂例如,欧盟的碳价在2023年2月曾一度突破100欧元/吨,而目前中国碳市场的碳价仅约为60元/吨,两者在现阶段显然不具备对接的基础㊂此外,虽然有学者认为欧盟当前的海运碳排放交易制度符合国际海洋法和国际气候立法,②但其制度的合法性与有效性依然值得质疑㊂就合法性而言,虽然赋予一国国内环境保护法规以域外效力是当前及今后环境保护法规效力范围的发展趋势,也是多边环境保护条约的基本要求及制定目标,③但欧盟单方面将欧盟港口与非欧盟港口间航程的50%碳排放量纳入碳排放交易系统缺乏足够的依据,因为在欧盟管辖海域所产生的碳排放量未必达到了50%,欧盟很可能将船舶在其他国家和公海的航程所产生的碳排放纳入了自己的交易系统,涉嫌对自身管辖权的扩张和对其他国家排他性管辖权的侵犯㊂就有效性而言,单边路径不利于国际社会形成统一的减排规划和执行监督体系,甚至可能带来重复治理㊁管辖冲突等负面问题㊂而且欧盟单边行动很可能带来的直接效应是海运公司为减少在欧盟境内的碳排放,在进出欧盟的航线上投入更高技术标准的较新型船舶,而将旧船舶投入到其他航线,最终结果仅是改变了碳排放的地区分布,而非真正的碳减排㊂因此,可以参考当初国际社会抵制欧盟在航空领域推行碳排放交易制度的做法,对欧盟单边海运碳交易机制采取以下应对措施:第一,在通过双边对话表达我国反对立场的基础上,参考国际民航组织(ICAO)非欧盟成员国签署‘莫斯科宣言“共同反对欧盟单方面将国际航空纳入欧盟碳排放交易体系的做法,④联合IMO的非欧盟成员国,要求欧盟停止单边行动,形成对欧盟的国际压力㊂事实上,早在欧盟提出将碳排放交易体系扩展到海运业的立法提案时,国际航运公会(ICS)就曾对此提出异议,并通过影响分析向欧盟提出谨慎考虑实施区域性海运碳交易制度的提议㊂⑤第二,尝试推动IMO通过决议,对欧盟单边措施与国际共识的违背性予以认定并敦促其放弃单边措施㊂值得参考的是,国际民航组织第194届理事会曾通过决议,认为欧盟单边行为违反了‘芝加哥公约“第一条列出的国家主权原则,同时也违反了‘联合国气候变化框架公约“及其‘京都议定书“的相关原则和规定,敦促欧盟与国际社会合作应对航空排放问题㊂⑥此外,考虑到欧盟单边进路的重要原因是多边机制的谈判进度缓慢,因此通过积极推动IMO层面多边碳排放市场机制进程,使欧盟的单边进路不再具有必要性,可能是促使欧盟放弃单边措施的最有效理由㊂二㊁海运碳排放市场机制的多边进路统筹㊀㊀IMO是国际上协调各国海上航行安全和防67①②③④⑤⑥廖兵兵: 双碳 目标下我国航运实现碳中和路径研究 ,‘太平洋学报“,2022年第12期,第94页㊂ManolisKotzampasakis, IntercontinentalShippingintheEuropeanUnionEmissionsTradingSystem:A Fifty-Fifty AlignmentwiththeLawoftheSeaandInternationalClimateLaw? RECIEL,Vol.32,No.1,2023,pp.29-43.胡晓红: 欧盟航空碳排放交易制度及其启示 ,‘法商研究“,2011年第4期,第147页㊂我国签署 莫斯科宣言 反对欧盟单边征收航空碳税 ,中央政府门户网站,2012年2月23日,https://www.gov.cn/govweb/gzdt/2012-02/23/content_2075064.htm㊂ICS, InceptionImpactAssessmentfortheProposedAmend⁃mentoftheEUEmissionsTradingSystem(Directive2003/87/EC) ,November26,2020,https://www.ics-shipping.org/wp-content/up⁃loads/2020/11/Inception-Impact-Assessment-for-the-proposed-A⁃mendment-of-the-EU-Emissions-Trading-System-Directive-2003-87-EC.pdf.国际民航组织明确抗议欧盟航空征碳税计划受挫 ,中新网,2011年11月4日,https://www.chinanews.com/cj/2011/11-04/3437766.shtml㊂第1期㊀曹兴国:我国海运碳排放市场机制构建的进路统筹止船舶污染政策和制度的主要平台,有关海运碳排放市场机制的多边讨论也主要在IMO层面展开㊂2.1㊀IMO主导下的多边市场机制进程IMO有关海运碳排放市场机制的谈判进程经历了一个曲折的过程㊂在2006年召开的IMO海上环境保护委员会第55次会议通过的工作计划中,基于市场的措施被列为应考虑的减排措施之一,海运碳排放市场机制在IMO层面开始得到关注㊂但由于发达国家和发展中国家之间缺乏共识等因素,此后成员国和相关组织提出的多种方案都未经深入讨论和评估,直至2013年的IMO海上环境保护委员会第65次会议宣布暂停有关市场机制内容的进一步讨论㊂中断的市场机制讨论在2018年重新获得重视 IMO海上环境保护委员会第72次会议通过的‘IMO船舶温室气体减排初步战略“在中长期措施中明确提出考虑市场机制,并提出拟在2023年至2030年之间商定候选中期措施㊂此后,市场机制重新进入成员方视野,多国重启市场机制的讨论㊂在IMO海上环境保护委员会第79次会议期间,普遍形成的共识是将技术措施与经济措施相结合,特别是设计一揽子将温室气体燃料标准与经济措施(市场机制)相结合的措施,可以促进实现初始战略的目标,并筹集足够和可预测的收入,以刺激公正和公平的过渡㊂①此种共识的形成在很大程度上源于各国对碳排放市场机制价值的进一步认识和其他领域的经验积累,尤其是低碳㊁零碳燃料在短期内欠缺商业竞争力的情况下,各方意识到通过市场机制实现碳减排正向激励的必要性㊂目前,IMO层面有关市场机制的讨论已经进入到关键阶段,相关成员国和组织也在不断提出和完善各自的方案㊂2.2㊀多边市场机制的方案选择当前提交至IMO的候选方案都采用技术措施与市场机制相结合的形式,主要包括以下几种㊂(1)欧盟的温室气体燃料标准(GFS)+碳税(levy)方案温室气体燃料标准要求船舶在合规期内使燃料的温室气体强度(GFI)等于或低于某一限值㊂在过渡阶段,为避免低/零排放燃料供应不均产生的影响,将以自愿参加的灵活合规机制(FCM)为船方提供其他遵守温室气体燃料标准的方式:当船舶使用温室气体强度低于要求的燃料时将获得灵活合规单位(FCU),灵活合规单位可以交易给使用超过温室气体强度要求燃料的船舶以抵销其超标的排量㊂另外,温室气体燃料标准登记处以一定的价格提供温室气体补救单位(GHGRemedialUnits,GRU)以抵销超额排放,温室气体补救单位的价格应反映船用燃料价值链中温室气体减排的成本,并增加劝阻因素,以确保灵活合规单位是替代合规的首选手段㊂与温室气体燃料标准相结合,碳税为其市场机制部分,由IMO气候转型基金负责费用的征收与使用㊂温室气体燃料标准和征税都适用于全过程的温室气体排放(Well-to-Wake)㊂②(2)中国㊁国际航运公会㊁日本的基金与奖励(FundandReward)机制中国提议建立国际海运可持续基金与奖励(InternationalMaritimeSustainableFundandRe⁃ward,IMSF&R)机制㊂在最初方案中,中国等建77①②MEPC, ReportoftheMarineEnvironmentProtectionCom⁃mitteeonItsSeventy-NinthSession ,TheSeventy-NinthSessionoftheMarineEnvironmentProtectionCommittee,16to20May2022,MEPC79/15,paras.7,14,54.Austria,etal., CombinationofTechnicalandMarketBasedMid-TermMeasuresIllustratedbyCombiningtheGHGFuelStandardandaLevy ,The13thSessionoftheIntersessionalWorkingGrouponReductionofGHGEmissionsfromShips,5to9December2022,ISWG-GHG13/4/8;Austria,etal., ElaborationontheProposalofCombiningtheGHGFuelStandardandaLevy ,The15thSessionoftheIntersessionalWorkingGrouponReductionofGHGEmissionsfromShips,26to30June2023,ISWG-GHG15/3/2.关于温室气体燃料标准制度的解释,SeeAustria,etal., ProposalforaGHGFuelStandard ,The12thSessionoftheIntersessionalWorkingGrouponReductionofGHGEmissionsfromShips,16to20May2022,ISWG-GHG12/3/3;Austria,etal., FurtherDevelopmentoftheProposalforaGHGFuelStandard ,The13thSessionoftheIntersessionalWorkingGrouponReductionofGHGEmissionsfromShips,5to9De⁃cember2022,ISWG-GHG13/4/7.。

中国基本经济制度 双语

中国基本经济制度双语中国基本经济制度(Chinese Basic Economic System)中国基本经济制度是指在中国社会主义市场经济体制下的一系列经济制度安排和规定,以实现社会主义现代化建设为目标。

中国基本经济制度的双语解释如下:1. 公有制度(Public Ownership):•中文解释:公有制度是中国经济制度的基石,包括社会主义全民所有制和社会主义集体所有制。

国家保持对经济命脉的掌握,坚持公有制在国家资本主义中的主导地位。

•英文解释:Public ownership is the cornerstone of the Chinese economic system, including socialist public ownership and socialist collective ownership. The state maintains control over the economic lifelines, insisting on the dominant position of public ownership in state capitalism.2. 混合所有制(Mixed Ownership):•中文解释:混合所有制是在公有制的基础上,逐步引入非公有制经济成分,鼓励和规范私人经济的发展,促使社会主义经济更加多元化。

•英文解释:Mixed ownership is based on public ownership, gradually introducing non-public ownership components, encouraging and regulating the development of private economy, and making socialist economy more diversified.3. 市场机制(Market Mechanism):•中文解释:市场机制是在公有制为基础的前提下,通过市场调节资源配置,实现生产者、消费者和生产资料拥有者之间的有机联系,发挥市场在资源配置中的决定性作用。

论国民收入分配制度改革的宪法规制

第猿苑卷第员期圆园员员年员月徐州师范大学学报(哲学社会科学版)允援燥枣载怎扎澡燥怎晕燥则皂葬造哉灶蚤援(孕澡蚤造燥泽燥责澡赠葬灶凿杂燥糟蚤葬造杂糟蚤藻灶糟藻泽耘凿蚤贼蚤燥灶)灾燥造援猿苑,晕燥援员允葬灶援,圆园员员论国民收入分配制度改革的宪法规制黎晓武辛振宇(南昌大学法学院,江西南昌猿猿园园猿员)[关键词]国民收入分配制度;改革;宪法规制[摘要]目前,我国国民收入分配领域存在的问题主要有:初次分配没有突出“劳动正义”;再分配不够公平公正,且分配力度有限;第三次分配亟待加强,且制度体系有待完善;“灰色收入”大量存在。

造成这些问题有历史、法律、体制等方面的原因。

如不加快改革现行收入分配制度体系,那么现行收入分配制度造成的问题将不仅损害社会公平正义和抑制社会发展,而且会阻碍经济发展和制约社会主义优越性的发挥,甚至影响社会稳定。

然而,国民收入分配制度改革本质上是个宪法问题,其改革必须在宪法层面上进行,受国家与公民关系、宪政和谐共处思想、人民当家作主宪法理念、公民生存权和发展权的规制,国民收入分配制度改革应由全国人大来主导。

只有这样,改革才能成功,收入分配不公等问题才能够得到完满解决。

[中图分类号]云园源苑[文献标识码]粤[文章编号]员园园苑鄄远源圆缘(圆园员员)园员鄄园员园远鄄园远改革开放猿园多年来,我国在经济和社会领域取得了伟大成就,但同时也产生了一些突出的矛盾和问题,特别是在国民收入分配领域,分配不公、贫富分化等问题日益严重。

这些问题已经成为全社会所关注的热点,必须加快改革现行收入分配制度体系,以促进社会发展,保持社会稳定。

国民收入分配制度如何改革,已成为学界、政府有关部门和百姓的热议话题。

尤其是学者们(特别是经济学家们)对我国收入分配制度改革作了深入的探讨和研究,并提出了许多有价值的看法和建议。

然而,收入分配制度改革涉及多方既得利益,这些利益主体势必会对改革造成强大的阻力,讨论数年、数易其稿的“收入分配指导意见”和“工资条例”至今难以出台就是最好的明证。

中央文献重要术语英文翻译

中央文献重要术语译文发布区域协同发展coordinated development between regions城乡发展一体化urban-rural integration物质文明和精神文明协调发展ensure that cultural-ethical and materialdevelopment progress together军民融合发展战略military-civilian integration strategy经济建设和国防建设融合发展integrated development of the economy andnational defense京津冀协同发展coordinated development of the Beijing,Tianjin, and Hebei region综合立体交通走廊multimodal transport corridor居住证制度residence card system财政转移支付同农业转移人口市民化挂钩机制mechanism linking the transfer payments a local government receives to the number of former rural residents granted urban residency in its jurisdiction城镇建设用地增加规模同吸纳农业转移人口落户数量挂钩机制mechanism linking increases in the amount of land designated for urban development in a locality to the number of former rural residents granted urban residency there中国特色新型智库new type of Chinese think tanks马克思主义理论研究和建设工程Marxist Theory Research and DevelopmentProject哲学社会科学创新工程initiative to promote innovation inphilosophy and the social sciences网络内容建设工程initiative to enrich online content农村人居环境整治行动rural living environment improvementinitiative历史文化名村名镇towns and villages with rich historical andcultural heritage美丽宜居乡村 a countryside that is beautiful and pleasantto live in中文英文the全面建成小康社会决胜阶段society in all respects。

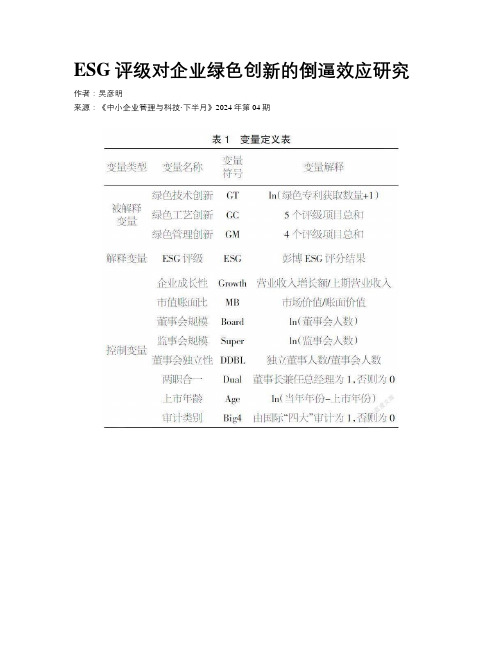

ESG评级对企业绿色创新的倒逼效应研究

ESG评级对企业绿色创新的倒逼效应研究作者:***来源:《中小企业管理与科技·下半月》2024年第04期【摘要】论文以沪深A股上市公司为例,探究了ESG评级与企业绿色创新的关系。

研究结果表明,ESG评级促进了企业的绿色技术创新、绿色工艺创新及绿色管理创新,在使用一系列稳健性检验方法进行检验后结论依然成立,在落实“双碳”目标的背景下为企业的可持续发展提供了新的经验证据。

【关键词】ESG;绿色技术创新;绿色工艺创新;绿色管理创新【中图分类号】F273.1;X322 【文献标志码】A 【文章编号】1673-1069(2024)04-0047-031 引言当前,全球环境约束日益严格,企业绿色转型势在必行,越来越多的企业推动生产工艺和运营管理绿色化转型,从而履行社会责任,以树立良好的社会形象。

与此同时,大众环境理念和政府环境规制日益加强,促使更多的投资者从单纯关注企业的财务表现转变为追求长期效益和社会责任履行。

ESG,即环境、社会和公司治理,作为新兴投资理念和企业评价标准,能够为投资者发现具有发展潜力和社会责任感的优质企业提供重要参考。

本文将绿色创新细分为3个维度,考察ESG评级能否倒逼企业绿色创新,为丰富ESG微观效应和促进企业绿色创新提供重要的启示。

2 理论分析与研究假设2.1 ESG评级与绿色技术创新ESG评级全面考量企业在环境、社会和公司治理等方面的表现,为绿色技术创新提供了强大动力。

第一,ESG评级要求企业在创新过程中充分考虑对环境的影响,直接推动了企业对绿色技术的重视和投入,通过对绿色技术的积极研发和应用,有助于降低企业运营对环境的负面影响;第二,ESG评级引导更多的投资者在关注企业财务表现的同时,将企业的环保表现和社会责任的承担状况作为投资决策的依据,进而为企业绿色技术创新提供了强大的市场动力,企业通过提升自身综合表现,树立良好的企业形象和信誉。

良好的口碑有助于缓解企业的融资约束,吸引更多的环保投资者加大对企业生态科技的投入,进而为绿色技术创新提供稳定的资金支持。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

State Regulation in Income Distribution in Urban Areas during the Transitional PeriodLiu Jingming*本研究透过职业阶层、教育与政治资本三个重要因素,侧重分析了市场化改革过程中国家力量对劳动力市场中收入分配的影响。

在国家规制影响较大的劳动力市场部门,职业阶层间收入差距较小;人力资本回报的提高受国家改革计划的影响明显。

而在新生的市场经济部门,不仅阶层间收入不平等扩展迅速,而且体力劳动者的市场境遇也大大低于国有部门和集体部门。

由于更多地受国家政治过程的影响,政治资本对改革后新生代劳动力的工资收益的影响呈现出随进入劳动力市场的时间而快速下降的态势。

I. Background of This ResearchThe introduction of the market economic factor into the economic system of socialist countries and the growth of this factor have given rise to a series of important theoretical issues and triggered a “market transition de-bate” (MTD). The man who provoked this debate is Victor Nee, who, based on his in-vestigations in the countryside of Fujian Province in East China, put forward a series of theoretical hypotheses about market tran-sition and changes in the social stratifying mechanism. In his opinion, during the mar-ket transition the marketing ability of direct producers will gradually replace redistribu-tion power and become the main profit earn-ing mechanism in the marketization process; as a result, the role of redistribution power and political capital will fall and direct pro-ducers will be the main beneficiaries. In the debate that followed arose a series of com-petitive hypotheses and different theoretical orientations produced widely divergent em-pirical research conclusions. Many scholars have realized the crux of the matter: studies on changes in the social stratifying mecha-nism should start with the concrete social process and cannot be restricted to this or that analytical framework or normal paradigm.This debate centered round “redistribu-tion power.” It overlooked the possible nega-tive results of the marketization itself – the growth of inequalities within the market and the rapid comparative decline of the “direct producers” in market sectors – and ignored some important problems that should have received attention.Firstly, the concept of “redistribution power” has two levels of meaning: first, the power delegated by the former redistribu-tion system; second, the power enjoyed by government departments and state-owned/STATE REGULATION IN INCOME DISTRIBUTION IN URBAN AREAS47collective economic sectors during the mar-ket-oriented reform. Both sides to the de-bate did not strictly distinguish between the two levels. In fact, with the deepening of the marketizing process, the former “redis-tribution” departments like the state-owned and collective enterprises have found a place, to various degrees, in the field of the market economy while social organizations, includ-ing government departments, have all come under the impact of market principles and their form of power is somewhere in the continuity from redistribution to market;1 the empirical facts of “redistribution power”listed in the dispute are, to a large extent, only an admixture with market power.Secondly, when Victor Nee introduced the theory of human capital into studies on changes in the social stratification mecha-nism in China he took the unified, balanced and fully competitive labor market as a ref-erence frame. But he seemed not to take into account the various forces capable of chang-ing the nature and structure of the labor market in China in the rapid modernization drive and the changing social reform process, for instance institutional factors, administra-tive intervention and the almost inexhaust-ible “surplus” rural labor. As a matter of fact, these factors have produced an effect on the model of human capital return in the labor market that should by no means be overlooked.Thirdly, the proposition of “political capital return” seems to leave more leeway for discussion. In agreement with the social stratifying mechanism in all other countries, social resources and opportunities are also distributed according to people’s occupa-tional positions in socialist countries. Wage scales and benefits and earnings in kind or money for individuals are determined not according to whether they are Party mem-bers but according to their jobs, posts or positions. Although a lot of studies indicate that the acquisition of positions is related to Party member status most of the studies on political capital return do not distinguish be-tween the effects of the two and therefore attribute, wholly or partly, the variance that should have been explained by the variable of “occupational stratum” to the variable of “Party member status.”Most importantly, both sides to the dis-pute overlooked the changing process of political life that is more closely related to the variable of “political capital.” The social transformation in China since 1976 has in-volved a social transition from a politicized society to an economy-led society and the social stratification has changed from politi-cal to economic stratification.2 This means that the effect of political capital on resources distribution and other aspects of social life began to change before the marketization process was triggered. Changes in the ef-fect on political capital return are not neces-sarily correlated to the marketization process. Moreover, even if they are correlated, to some extent, to each other, we need to take into consideration the fact that the reform towards marketization is carried out under the guidance of state power. The political restructuring promoted by the state in order to promote the building of political power during the market transition has a more di-rect bearing on the effects of “political capital.” We therefore have reason to believe48SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CHINA Summer 2007the effects of “political capital” are more likely to follow the course of changes in political life in the whole country, and do not simply cling to the marketization process.II. State Regulation in the Marketization ProcessThe viewpoints of this paper are as follows: “marketization” has been one of the important processes in the social changes since the initiation of reform in China, but it is not an isolated and “omnipotent” force for social change; the impact of the market economy on social process, social stratum structure and the stratification mechanism has also depended on the political process within society, the model of relations among the forces of different social strata and the role of state power.First of all, the state-led marketization reform is a political and economic process with the state as a key player and its main objective is to use the market economy model to transform the original economic growth structure and economic development model so as to build up national economic strength and comprehensive competitiveness and raise the national standard of living. “State-led”means that the market-oriented reform pro-cess is in the hands of the state and the ma-jor plans of social and economic reform are all made after taking stock of the situation and in accordance with long-term national interests, embracing many important prin-ciples of national interests for which the market cannot provide a replacement. A mar-ket economy follows mainly market laws, but the impact of the market economy and marketizing process on people’s social, cul-tural and political life and social interest rela-tions is logically under the control and regu-lation of the state.Next, the essence of market principles is competition rather than protection and they stress efficiency rather than fairness. The marketization process may therefore result in a lot of social injustice – it is here that state regulation is needed.Karl Polanyi once said there is “no mar-ket road to a market economy.” In order to “avoid the ”getting drowned “inherent in the self-regulating market” the development of the market economy in the West has always been accompanied by the introduction of protective social measures to counter the market forces. The history of market economy development in Europe and America shows that a completely self-regu-lating market would eventually lead to reces-sion and turmoil and that a bigger “cake”would only go bad. Without the self-protec-tion of the social community, the logic of the market would turn all of us and our so-cial relations into commodities. In this sense,“state regulation” serves as a guarantee for realizing the established objective in the marketization process: ensuring the stable and orderly operation of the whole society and preventing social rupture, or generating a new mechanism of social fusion where social rupture occurs.Then, how does the state-led market-ization process influence the changes in the str ucture and mecha nism of soc ial stratification?The market as an economic model was chosen in China because, first of all, it couldSTATE REGULATION IN INCOME DISTRIBUTION IN URBAN AREAS49effectively solve the bottlenecks in the eco-nomic process at that time such as lack of incentives and low efficiency. But the model for sharing the fruits of economic growth is a social institutional arrangement, a result of interactions of the three forces – the state, social strata and market transactions. The influence of social strata on the social model of distribution is expressed as relations of power operation inside the society, includ-ing the power transactions in the market. This means that power does not rashly give up its basic claims on resources, opportunities and living conditions just because it is labelled “redistribution” or “market.” While regulat-ing the market economy and society, the state may restrict and influence the above power relations with the aid of ideological orientation, administrative mechanisms, policy making and the inertia of established social institutions.On the basis of the above line of thinking, this paper will focus on tests of the following three research hypotheses.Hypothesis 1: The income gap among different strata widens as the degree of marketization increases, while state regula-tion has a considerable restraining effect on income gaps in the labor market.1.1 In the newly emerging market eco-nomic sector, along with industrial upgrading, the expansion of the size of enterprises and increasing maturity in their business administration, management and technology become more and more important in the pri-vate economic sector (including foreign-funded enterprises) and pay for people in management and technological positions rap-idly increases.1.2 In the private economic sector, in view of changes in the labor market struc-ture and the excessive supply of surplus rural labor manual workers (or “direct pro-ducers” as Nee calls them) get much less pay than in the early days of marketization.1.3 In the state-owned, collective and public sectors and government departments, under the protective regulation of the state (mainly for manual workers) the income gaps among occupational strata are smaller and changing more slowly.In the first place, in the newly emerging market economic sector, wages for labor fluctuate with the conditions in the labor market.Before the 1990s, the employment of workers in the urban areas of China had to be carried out through work units under the planned economy model. The migration of labor was severely restricted by various fac-tors such as work units and the residence registration system with the private economic sector having an insufficient supply of labor. The situation changed drastically after the publication of remarks made by Deng Xiaoping during his inspection tour of South China in 1991 and 1992; millions upon mil-lions of surplus rural laborers flowed into the cities in an endless stream (the so-called “tide of migrant laborers”), providing suffi-cient cheap labor for the rapid progress of the private economic sector. In almost the same period, the incessant reforms in state-owned and collective enterprises, especially the reform of state-owned enterprises that be-gan around 1994 and was characterized by optimization of grouping and enterprise restructuring, almost totally broke the mo-50SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CHINA Summer 2007nopoly of labor resources by the state-owned sector. In the period from 1998 to 2003, the number of state-owned enterprises and state-owned holding enterprises dropped from 238,000 to 150,000, by 40%, and cumula-tive number of laid-off workers over the six years reached 30.90 million.3 The over-sup-ply of labor brought down the relative in-come of manual workers in the private eco-nomic sector.However, the situation is somewhat dif-ferent in the labor market subject to state regulation. When the average income out-side the official structure rises by a large margin the government can increase the wages of those inside the official structure by means of expanding the fiscal budget in order to keep an overall income balance in the labor market. On the other hand, as a residue of the past state regulation measures, the model of egalitarian distribution contin-ues to play its part and the old practice that wages are permitted to rise but not to fall still prevails, helping protect the wage income of manual workers inside the official structure.Hypothesis 2: Market competition serves as the basic source for the rise in returns to human capital but in the parts of the labor market with strong state regulation the rise in returns to human capital hinges more on policy readjustments.In the opinion of the author, the admin-istrative mechanism for raising the returns to human capital functions only when the “planning opportunity” appears. While the government has been guiding market-ori-ented economic reform, the human capital under government regulation has been gradu-ally affected by the ever-deepening market competition. The multifarious forms of en-terprise reform such as buying out length of service and enterprises going into bankruptcy and merger have removed batch after batch of older, technically less capable workers and staff from the official labor market, giving the restructured enterprises an opportunity to construct a new income distribution mechanism. And the timing of the appear-ance of these new “planning opportunities”has been chosen in accordance with the progress of the market-oriented reform pro-moted by the state.As a matter of fact, while the low-level labor markets in urban areas were gradually unified under the continuous pounding of the “tide of migrant laborers” and “laying-off and unemployment,” two important changes took place in the high-end labor market: the re-form of government departments and the setting up of human resource markets. The extensive building up of the market for tal-ent brought order into the competition in the high-end labor market and the price of talent also became clearer, providing relatively dis-tinct information for the labor market under state regulation. Since the introduction of reform and opening-up, the Chinese govern-ment has carried out five large-scale reforms of government departments and taken a se-ries of supplementary measures in the re-form of the cadre and personnel system. By June 2002, 1.15 million cadres and employ-ees had been culled from the Party and gov-ernment departments at all levels from the central authorities down to townships and towns. By adopting a sweeping approach to reducing redundant personnel and enforcingSTATE REGULATION IN INCOME DISTRIBUTION IN URBAN AREAS51new wage scales human capital returns in government departments quickly achieved equilibrium with those in the external market.Hypothesis 3: State regulation not only plays its role in direct intervention in the la-bor market, but also produces effects on socio-economic life by maintaining a con-ceptual or ideological orientation, thus chang-ing the assessment in the labor market of some special factors (for example, political capital).After the smashing of the “Gang of Four” in 1976 and the shift of focal point in the work of the Party Central Committee to economic construction in 1978, great changes took place in the atmosphere of political and social life in China, marking, as Professor Li Qiang said, a shift from politi-cal stratification to economic stratification. In times with political stratification as the dominant principle, the distribution of better occupational positions and career paths was directly related to political status, class back-ground and political creed. After the launch-ing of reform and opening-up, the assess-ment criteria in employment and promotion began to shift, signifying that the effect of the returns to political capital for those who joined the army of workers after this point in time has gradually fallen over time and has fluctuated with the changes in the political climate.The specific mechanism might be de-duced as follows:(1) With the politicized society left be-hind and reform and opening-up ushered in, all sorts of recruiting units have gradually given up the former politically oriented cri-teria (political status, family background, etc.)for employment and given more emphasis to non-political criteria like educational back-ground in their recruitment of new employees, with political capital becoming less and less important for acquiring one’s first position.(2) With the politicized society left be-hind and reform and opening-up ushered in, political considerations have been gradually relegated to a secondary place and non-political factors like education and knowl-edge have received great attention in career advancement within social and economic organizations, with political capital becom-ing less important in individuals’ career progression.(3) Since individuals’ first jobs are of utmost importance for their careers, the oc-cupational assessment criteria in the labor market when individuals seek their first job may exert a significant influence over their life journeys and have a direct bearing on their career progression.As a result, we can arrive at this deduc-tive hypothesis: because of a change in the orientation of state regulation over social, economic and political life throughout the country, the returns to political capital in the future labor market for those who entered the labor market after the beginning of re-form will gradually decline over time.III. Findings and AnalysesThis paper chooses data from the na-tional urban sample surveys at five points of time after the reform began in the cities in China (1988, 1995, 1996, 2000 and 2003) in order to draw an outline of the changes in52SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CHINA Summer 2007wage earnings in the labor market. The data for 1988 and 1995 are from the individual urban samples of the two surveys of “The Income Distribution of Chinese Residents”jointly conducted by Zhao Renwei and Li Shi from the Institute of Economics under the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and the foreign scholars Keith Griffin and Carl Riskin (CHIP88 and CHIP95); the data for 1996 is from the joint studies by Professor Li Qiang from Renmin University of China, Donald Treiman and Andrew Walder, with the ur-ban samples being selected for the purpose of analysis; the data for 2000 is from the “Survey of Ten Cities,” one of the major projects supported by the National Social Sciences Fund during the Ninth Five-year Plan, presided over by Professor Zheng Hangsheng from Renmin University of China; and the data for 2003 are from the Chinese General Social Survey conducted jointly by the Survey Research Centre of Hong Kong University of Science and Tech-nology and the Department of Sociology of Renmin University of China (CGSS2003).1. Basic modelThe analyses of the data at the five points of time in this study take the following OLS (ordinary least square) model (Equation 1a) as the basic model:In Equation 1a, t indicates different point of time of data, i indicates sample individual in the investigation at different point of time. Ln(Y) is the natural logarithm of monthly income. S is number of years of schooling, W is length of service (= age – number of years of schooling – 7) and W2 is the square of length of service / 100. These are three Mincer equation variables. Female and Party are two dummy variables, indicating respec-tively sex (female = 1) and Party memberstatus (Party member = 1);repre-sents dummy variables of four sectors of the labor market. The labor market is divided into five sectors: the Party and government departments and organizations, public institutions, state-owned enterprises, collec-tive enterprises and the private economy. All those employed by individual proprietors, Sino-foreign joint ventures, co-production, solely foreign-owned or foreign-funded en-terprises are classified in the private economic sector. In the model the private economic sector serves as the reference.Since Equation 1a may be rendered into the following general form:(Equation 1b)Therefore, the OLS model with com-parisons of points of time is as follows:(Equation 2)(Equation 1a)STATE REGULATION IN INCOME DISTRIBUTION IN URBAN AREAS53indicates the effect coefficient ma-trix of the benchmark year (the two bench-mark years in the two comparisons are 1988 and 1996 respectively);represents the cross effect of dummy variables of comparison years ( ) and the vector matrix is the effect change matrix of comparison years in rela-tion to the benchmark year.2. Income gap among social strata(Equation 3)We examine with Equation 3 the income gap among social strata in different sectors at various points of time. is the vector matrix of all the independent variables ex-cept “occupational stratum” in Equation 1a;represent respectively supervi-sory staff and specialized technical person-nel (dummy variables) in different sectors; clerks are not investigated cross sectors.The results of the model indicated that in the labor market in 1988 the income of specialized technical personnel was 11.85%higher than that of manual workers in the Party and government departments, public institutions, state-owned and collective enterprises while in the private-owned economic sector the income of specialized technical personnel was lower than that of manual workers [only 61.5% of manual workers’income]. But the latter situation rapidly changed: in the labor market, the ratio of the income of specialized technical personnel to that of manual workers increased by 140%in 1995 over 1988 in the pri-vate-owned economic sector while the fig-ure was only 6.5% in the Party and govern-ment departments, and not statistically significant. In state-owned and collective enterprises, the figure was 11%. The rela-tive income of specialized technical person-nel was slightly lower in 2003 than in 1996 in the labor market sectors under strong state regulation but the figure was 77%higher in the privately owned economic sector.The income gap between supervisory staff and manual workers across the sec-tors was similar to that between specialized technical personnel and manual workers. It can be concluded that the income gap be-tween supervisory staff and manual work-ers was obviously much bigger in the pri-vately owned economic sector than in the Party and government departments, public institutions and state-owned and collective enterprises, and the gap was widening at a greater pace. Take the labor market in 2003 for example: the income gap between super-visory staff and manual workers was 2.07 times in the privately-owned economic sec-tor and was 75% (p < 0.01) higher than that between supervisory staff and manual work-ers in the Party and government departments, public institutions and state-owned and col-lective enterprises. The relative income gap between supervisory staff and manual work-ers in the privately-owned economic sector widened by 54% in 2003 com-pared to that in 1996, while the figure was 6 ~ 7% in Party and government departments, public institutions and state-owned and col-lective enterprises and was not statistically54SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CHINA Summer 2007significant.We can gain the following basic empiri-cal understanding from the above analysis: in the years from 1988 to 2003 the income gap between occupational strata in the whole labor market became increasingly wide, es-pecially in the privately owned economic sector, while the manual workers still remain-ing in the state-owned and collective sector under strong state regulation received more protection.3. Variance in the rate of return to edu-cation in different sectors(Equation 4)We examine with Equation 4 the vari-ance in the rate of return to education in dif-ferent sectors at various points of time.is the vector matrix of all the independent variables except “years of schooling” in Equation 1a; indicates the years of school-ing of sample individuals belonging to dif-ferent sectors and represents the rate of return to education in the five sectors.In different periods, the rise in the rate of return to education in different sectors varies widely. The data at the two timepoints in 1988 and 1995 demonstrate that the rate of return to education in the privately-owned economic sector reached more than 7%, sig-nificantly higher than that in the other four sectors under strong state regulation; the situ-ation was the same in 1996. However, in the labor market in 2003, the rate of return to education increased by a big margin in all the five sectors (by 4%~7%) and the gaps across the sectors were already insignificant. The rate of return to education increased by a bigger margin in the Party and government departments and the other three sectors un-der strong state regulation in 2003 than in 1996, but the increase in the rate of return in the privately-owned economic sector was not statistically significant and was smaller than that in the Party and government depart-ments and the state-owned enterprises. The rapid increase of the rate of return to educa-tion from 1996 to 2003 was an indication that the enterprise restructuring in the middle and late 1990s and the reform of govern-ment departments starting from 1998 had a substantial effect on raising the return to human capital.4. Test of the hypotheses about the “re-turn to political capital”In the MTD literature, the logic of ar-gument about returns to political capital is clear: political capital combines with power to reap the benefits of “redistribution.” This means that if political capital is related to power, “then political capital combined with power will yield political capital gains not en-joyed by non-power strata.” We can test this statement by designing an interactive model of Party membership and occupational stratum.(Equation 5)We use Equation 5 to estimate the inter-active effects between Party membership and occupational strata in two models, one in-cluding all samples and the other including all samples except the privately-owned eco-nomic sector: between Party members andSTATE REGULATION IN INCOME DISTRIBUTION IN URBAN AREAS55specialized technical personnel, between Party members and supervisory staff and between Party members and clerical personnel. The results show that the inter-actions between Party membership and oc-cupational strata have a clear negative effect. For example, in the labor market of 2003, the model that includes all samples shows that the supervisory staff who were not Party m e m b e r s h a d a n i n c o m e29% () higher than that of the supervisory staff who were Party mem-bers and the model that includes all samples except the privately-owned economic sec-tor also shows a corresponding figure of 13. 5%. These figures prove the situation is just the reverse of the argument that political capi-tal combined with power leads to more benefits.In the view of the author, the marketized reform guided by the state is carried out, first of all, against the background of the chang-ing political climate throughout the country. The shift in social life from political to eco-nomic dominance has produced a direct im-pact on recruitment of labor, job arrange-ments and career advancement and the changed guiding principle for social life has had a sustained influence over the labor mar-ket process which finds its expression in the new generation cohorts of the working population. To test this hypothesis, the au-thor designed the following “moving cohort”regression model.(Equation 6)In Equation 6, subscript k indicates a group of continuous cohorts. Take the analy-sis of data in CGSS2003 for example: we take, first of all, a certain point of time K as the starting point (e.g., K = 1962), then se-lect those people who first entered the labor market in 1962 and the following nine years as the first cohort sample and carry out the first regression analysis according to Equa-tion 6. In the second regression we take the point of time K + 1 (= 1963) as the starting point, then select the people who first en-tered the labor market in 1963 and the fol-lowing nine years as the second cohort sample and carry out the second regression analysis. The rest is done in the same manner. Finally, the coefficients of the return to po-litical capital from this moving cohort sample group are used to portray the changing trend.As indicated by Figure 1, changes in the return to political capital for the labor mar-ket cohorts at the three timepoints are basi-cally identical. In the labor market of 1988, the return to political capital rises slowly be-fore the 1977 cohort but falls rapidly after the 1977 cohort. Looking again at the labor market of 1996, the return to political capital peaked at 24% with the 1975 cohort and then, beginning from the 1976 cohort, falls continuously and rapidly. Only around the 1984 cohort does it begin to fluc-tuate a little and then touches bottom with the 1989 cohort. In the labor market of 2003, the cohort with which the return to political capital begins to fall continuously and rap-idly appears even earlier (the 1973 cohort). This shows that the role of political capital for the newer cohorts was not only affected by the social and political changes in China when they sought their first jobs, but could。