An Answer to the Question What is Enlightenment

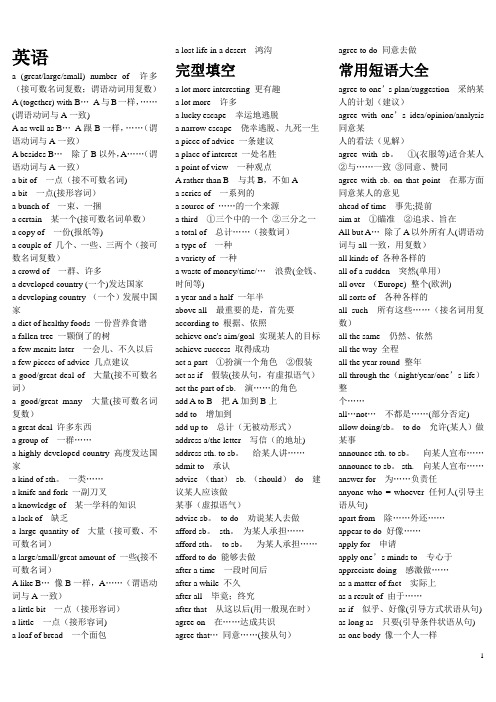

高考英语完形填空短语大全

英语a (great/large/small) number of 许多(接可数名词复数;谓语动词用复数)A (together) with B…A与B一样,……(谓语动词与A一致)A as well as B…A跟B一样,……(谓语动词与A一致)A besides B…除了B以外,A……(谓语动词与A一致)a bit of 一点(接不可数名词)a bit 一点(接形容词)a bunch of 一束、一捆a certain 某一个(接可数名词单数)a copy of 一份(报纸等)a couple of 几个、一些、三两个(接可数名词复数)a crowd of 一群、许多a developed country (一个)发达国家a developing country (一个)发展中国家a diet of healthy foods 一份营养食谱a fallen tree 一颗倒了的树a few menits later 一会儿、不久以后a few pieces of advice 几点建议a good/great deal of 大量(接不可数名词)a good/great many 大量(接可数名词复数)a great deal 许多东西a group of 一群……a highly-developed country 高度发达国家a kind of sth。

一类……a knife and fork 一副刀叉a knowledge of 某一学科的知识a lack of 缺乏a large quantity of 大量(接可数、不可数名词)a large/small/great amount of 一些(接不可数名词)A like B…像B一样,A……(谓语动词与A一致)a little bit 一点(接形容词)a little 一点(接形容词)a loaf of bread 一个面包a lost life in a desert 鸿沟完型填空a lot more interesting 更有趣a lot more 许多a lucky escape 幸运地逃脱a narrow escape 侥幸逃脱、九死一生a piece of advice 一条建议a place of interest 一处名胜a point of view 一种观点A rather thanB 与其B,不如Aa series of 一系列的a source of ……的一个来源a third ①三个中的一个②三分之一a total of 总计……(接数词)a type of 一种a variety of 一种a waste of money/time/…浪费(金钱、时间等)a year and a half 一年半above all 最重要的是,首先要according to 根据、依照achieve one's aim/goal 实现某人的目标achieve success 取得成功act a part ①扮演一个角色②假装act as if 假装(接从句,有虚拟语气)act the part of sb. 演……的角色add A to B 把A加到B上add to 增加到add up to 总计(无被动形式)address a/the letter 写信(的地址)address sth. to sb。

An_Answer_to_the_Question_What_is_Enlightenment

An Answer to the Question: What is Enlightenment? (1784)Enlightenment is man's emergence from his self-imposed immaturity. Immaturity is the inability to use one's understanding without guidance from another. This immaturity is self-imposed when its cause lies not in lack of understanding, but in lack of resolve and courage to use it without guidance from another. Sapere Aude! [dare to know] "Have courage to use your own understanding!"--that is the motto of enlightenment.Laziness and cowardice are the reasons why so great a proportion of men, long after nature has released them from alien guidance (natura-liter maiorennes), nonetheless gladly remain in lifelong immaturity, and why it is so easy for others to establish themselves as their guardians. It is so easy to be immature. If I have a book to serve as my understanding, a pastor to serve as my conscience, a physician to determine my diet for me, and so on, I need not exert myself at all. I need not think, if only I can pay: others will readily undertake the irksome 令人烦恼的work for me. The guardians who have so benevolently taken over the supervision of men have carefully seen to it that the far greatest part of them (including the entire fair sex) regard taking the step to maturity as very dangerous, not to mention difficult. Having first made their domestic livestock dumb, and having carefully made sure that these docile温驯的creatures will not take a single step without the go-cart 童车to which they are harnessed, these guardians then show them the danger that threatens them, should they attempt to walk alone. Now this danger is not actually so great, for after falling a few times they would in the end certainly learn to walk; but an example of this kind makes men timid and usually frightens them out of all further attempts.Thus, it is difficult for any individual man to work himself out of the immaturity that has all but become his nature. He has even become fond of this state and for the time being is actually incapable of using his own understanding, for no one has ever allowed him to attempt it. Rules and formulas, those mechanical aids to the rational use, or rather misuse, of his natural gifts, are the shackles束缚of a permanent immaturity. Whoever threw them off would still make only an uncertain leap over the smallest ditch, since he is unaccustomed to this kind of free movement. Consequently, only a few have succeeded, by cultivating their own minds, in freeing themselves from immaturity and pursuing a secure course.But that the public should enlighten itself is more likely; indeed, if it is only allowed freedom, enlightenment is almost inevitable. For even among the entrenched 根深蒂固的guardians of the great masses a few will always think for themselves, a few who, after having themselves thrown off the yoke束缚of immaturity, will spread the spirit of a rational appreciation for both their own worth and for each person's calling to think for himself. But it should be particularly noted that if a public that was first placed in this yoke by the guardians is suitably aroused by some of those who are altogether incapable of enlightenment, it may force the guardians themselves to remain under the yoke--so pernicious致命的is it to instill prejudices, for they finally take revenge upon their originators, or on their descendants. Thus a public can only attain enlightenment slowly. Perhaps a revolution can overthrow autocratic despotism and profiteering or power-grabbing oppression, but it can never truly reform a manner of thinking; instead, new prejudices, just like the old ones they replace, will serve as a leash 约束for the great unthinking mass.Nothing is required for this enlightenment, however, except freedom; and the freedom in question is the least harmful of all, namely, the freedom to use reason publicly in all matters. But on all sides I hear: "Do not argue!" The officer says, "Do not argue, drill!" The tax man says, "Do not argue, pay!" The pastor says, "Do not argue, believe!" (Only one ruler in the World says, "Argue as much as you want and about what you want, but obey!") In this we have examples of pervasive restrictions on freedom. But which restriction hinders enlightenment and which does not, but instead actually advances it? I reply: The public use of one's reason must always be free, and it alone can bring about enlightenment among mankind; the private use of reason may, however, often be very narrowly restricted, without otherwise hindering the progress of enlightenment. By the public use of one's own reason I understand the use that anyone as a scholar makes of reason before the entire literate world. I call the private use of reason that which a person may make in a civic post or office that has been entrusted to him. Now in many affairs conducted in the interests of a community, a certain mechanism is required by means of which some of its members mustconduct themselves in an entirely passive manner so that through an artificial unanimity the government may guide them toward public ends, or at least prevent them from destroying such ends. Here one certainly must not argue, instead one must obey. However, insofar as this part of the machine also regards himself as a member of the community as a whole, or even of the world community, and as a consequence addresses the public in the role of a scholar, in the proper sense of that term, he can most certainly argue, without thereby harming the affairs for which as a passive member he is partly responsible. Thus it would be disastrous if an officer on duty who was given a command by his superior were to question the appropriateness or utility of the order. He must obey. But as a scholar he cannot be justly constrained from making comments about errors in military service, or from placing them before the public for its judgment. The citizen cannot refuse to pay the taxes imposed on him; indeed, impertinent 无礼的;不相干的criticism of such levies, when they should be paid by him, can be punished as a scandal (since it can lead to widespread insubordination). But the same person does not act contrary to civic duty when, as a scholar, he publicly expresses his thoughts regarding the impropriety or even injustice of such taxes. Likewise a pastor is bound to instruct his catecumens and congregation in accordance with the symbol of the church he serves, for he was appointed on that condition. But as a scholar he has complete freedom, indeed even the calling, to impart to the public all of his carefully considered and well-intentioned thoughts concerning mistaken aspects of that symbol, as well as his suggestions for the better arrangement of religious and church matters. Nothing in this can weigh on his conscience. What he teaches in consequence of his office as a servant of the church he sets out as something with regard to which he has no discretion to teach in accord with his own lights; rather, he offers it under the direction and in the name of another. He will say, "Our church teaches this or that and these are the demonstrations it uses." He thereby extracts for his congregation all practical uses from precepts to which he would not himself subscribe with complete conviction, but whose presentation he can nonetheless undertake, since it is not entirely impossible that truth lies hidden in them, and, in any case, nothing contrary to the very nature of religion is to be found in them. If he believed he could find anything of the latter sort in them, he could not in good conscience serve in his position; he would have to resign. Thus an appointed teacher's use of his reason for the sake of his congregation is merely private, because, however large the congregation is, this use is always only domestic; in this regard, as a priest, he is not free and cannot be such because he is acting under instructions from someone else. By contrast, the cleric--as a scholar who speaks through his writings to the public as such, i.e., the world--enjoys in this public use of reason an unrestricted freedom to use his own rational capacities and to speak his own mind. For that the (spiritual) guardians of a people should themselves be immature is an absurdity that would insure the perpetuation of absurdities.But would a society of pastors, perhaps a church assembly or venerable presbytery (as those among the Dutch call themselves), not be justified in binding itself by oath to a certain unalterable symbol in order to secure a constant guardianship over each of its members and through them over the people, and this for all time: I say that this is wholly impossible. Such a contract, whose intention is to preclude forever all further enlightenment of the human race, is absolutely null and void, even if it should be ratified by the supreme power, by parliaments, and by the most solemn peace treaties. One age cannot bind itself, and thus conspire, to place a succeeding one in a condition whereby it would be impossible for the later age to expand its knowledge (particularly where it is so very important), to rid itself of errors,and generally to increase its enlightenment. That would be a crime against human nature, whose essential destiny lies precisely in such progress; subsequent generations are thus completely justified in dismissing such agreements as unauthorized and criminal. The criterion of everything that can be agreed upon as a law by a people lies in this question: Can a people impose such a law on itself? Now it might be possible, in anticipation of a better state of affairs, to introduce a provisional order for a specific, short time, all the while giving all citizens, especially clergy, in their role as scholars, the freedom to comment publicly, i.e., in writing, on the present institution's shortcomings. The provisional order might last until insight into the nature of these matters had become so widespread and obvious that the combined (if not unanimous) voices of the populace could propose to the crown that it take under its protection those congregations that, in accord with their newly gained insight, had organized themselves under altered religious institutions, but without interfering with those wishing to allow matters to remain as before. However, it is absolutely forbidden that they unite into a religious organization that nobody may for the duration of a man's lifetime publicly question, for so do-ing would deny,render fruitless, and make detrimental to succeeding generations an era in man's progress toward improvement. A man may put off enlightenment with regard to what he ought to know, though only for a short time and for his own person; but to renounce it for himself, or, even more, for subsequent generations, is to violate and trample man's divine rights underfoot. And what a people may not decree for itself may still less be imposed on it by a monarch, for his lawgiving authority rests on his unification of the people's collective will in his own. If he only sees to it that all genuine or purported improvement is consonant with civil order, he can allow his subjects to do what they find necessary to their spiritual well-being, which is not his affair. However, he must prevent anyone from forcibly interfering with another's working as best he can to determine and promote his well-being. It detracts from his own majesty when he interferes in these matters, since the writings in which his subjects attempt to clarify their insights lend value to his conception of governance. This holds whether he acts from his own highest insight--whereby he calls upon himself the reproach, "Caesar non eat supra grammaticos."'--as well as, indeed even more, when he despoils his highest authority by supporting the spiritual despotism of some tyrants in his state over his other subjects.If it is now asked, "Do we presently live in an enlightened age?" the answer is, "No, but we do live in an age of enlightenment." As matters now stand, a great deal is still lacking in order for men as a whole to be, or even to put themselves into a position to be able without external guidance to apply understanding confidently to religious issues. But we do have clear indications that the way is now being opened for men to proceed freely in this direction and that the obstacles to general enlightenment--to their release from their self-imposed immaturity--are gradually diminishing. In this regard, this age is the age of enlightenment, the century of Frederick.A prince who does not find it beneath him to say that he takes it to be his duty to prescribe nothing, but rather to allow men complete freedom in religious matters--who thereby renounces the arrogant title of tolerance--is himself enlightened and deserves to be praised by a grateful present and by posterity as the first, at least where the government is concerned, to release the human race from immaturity and to leave everyone free to use his own reason in all matters of conscience. Under his rule, venerable pastors, in their role as scholars and without prejudice to their official duties, may freely and openly set out for the world's scrutiny their judgments and views, even where these occasionally differ from the accepted symbol. Still greater freedom is afforded to those who are not restricted by an official post. This spirit of freedom is expanding even where it must struggle against the external obstacles of governments that misunderstand their own function. Such governments are illuminated by the example that the existence of freedom need not give cause for the least concern regarding public order and harmony in the commonwealth. If only they refrain from inventing artifices to keep themselves in it, men will gradually raise themselves from barbarism.I have focused on religious matters in setting out my main point concerning enlightenment, i.e., man's emergence from self-imposed immaturity, first because our rulers have no interest in assuming the role of their subjects' guardians with respect to the arts and sciences, and secondly because that form of immaturity is both the most pernicious and disgraceful of all. But the manner of thinking of a head of state who favors religious enlightenment goes even further, for he realizes that there is no danger to his legislation in allowing his subjects to use reason publicly and to set before the world their thoughts concerning better formulations of his laws, even if this involves frank criticism of legislation currently in effect. We have before us a shining example, with respect to which no monarch surpasses the one whom we honor.But only a ruler who is himself enlightened and has no dread of shadows, yet who likewise has a well-disciplined, numerous army to guarantee public peace, can say what no republic may dare, namely: "Argue as much as you want and about what you want, but obey!" Here as elsewhere, when things are considered in broad perspective, a strange, unexpected pattern in human affairs reveals itself, one in which almost everything is paradoxical. A greater degree of civil freedom seems advantageous to a people's spiritual freedom; yet the former established impassable boundaries for the latter; conversely, a lesser degree of civil freedom provides enough room for all fully to expand their abilities. Thus, once nature has removed the hard shell from this。

【要点梳理_高考英语】一轮基础知识复习:选修7Unit2

(desire

2 accompany vt.陪同,陪伴(keep sb. company);伴随,与……同时 发生(happen with);为……伴奏

•应试指导 (1)分词作状语的考查 (2)作为高级词汇替换go with

accompany sb. to some place陪伴某人去某地 accompany sb. at/on用……为某人伴奏 accompany...with/by与……同时存在或发生 keep sb. company陪伴某人 in company with与……一起 companion n.同伴,伙伴

27.thinking n.思想;思考→think vi.& vt.想;认为→thought n.思想;思 考 28.obey vt.& vi.服从;顺从→disobey vt.& vi.(反义词)不服从;违抗 29.declare vt.宣布;声明;表明;宣称→declaration n.宣言;公告;布 告;告示 30.talent n.天才;特殊能力;才干→talented adj.有才气的;有才能的 31.awful adj.极坏的;极讨厌的;可怕的;(口语)糟透的→awfully adv. 极;非常地 32.elegant adj. 优 雅 的 ; 高 雅 的 ; 讲 究 的 →elegance n. 高 雅 ; 优 雅 →elegantly adv.高雅地;雅致地

16.set aside 将……放在一边;为……节省或保留(钱或时间) 17.leave...alone不管;别惹;让……一个人待着;和……单独在 一起 18.assessment n.评价;评定→assess vt.评价;评定 19.affection n.喜爱;爱;感情→affect vt.感动;影响 20.desire n.渴望;欲望;渴求 vt.希望得到;想要→desirable adj. 渴望的;有欲望的 21.satisfaction n.满意;满足;令人满意的事物→satisfactory adj. 令人满意的→satisfy vt.使感到满意

国外英语高考试卷真题

Part 1: Listening Comprehension (25 points)Section 1: Short Conversations (5 points)Listen to the following five short conversations. Choose the best answer for each question.1. A. The man wants to buy a book.B. The woman wants to borrow a book.C. The man doesn't have a book.D. The woman doesn't have a book.2. A. The man is late for work.B. The woman is late for work.C. The man is late for school.D. The woman is late for school.3. A. The man is a teacher.B. The woman is a teacher.C. The man is a student.D. The woman is a student.4. A. The man is in a bookstore.B. The woman is in a bookstore.C. The man is in a library.D. The woman is in a library.5. A. The man is going to the gym.B. The woman is going to the gym.C. The man is going to the park.D. The woman is going to the park.Section 2: Long Conversations (10 points)Listen to the following two long conversations. Choose the best answer for each question.6. A. They are discussing the weather.B. They are discussing their vacation plans.C. They are discussing their study plans.D. They are discussing their future career plans.7. A. They are going to the beach.B. They are going to the mountains.C. They are going to a city.D. They are going to a museum.8. A. She wants to become a doctor.B. She wants to become a teacher.C. She wants to become a lawyer.D. She wants to become an engineer.Section 3: Short Passages (10 points)Listen to the following three short passages. Choose the best answer for each question.9. A. The passage is about a man who lost his job.B. The passage is about a woman who won a prize.C. The passage is about a boy who saved his mother's life.D. The passage is about a girl who discovered a new planet.10. A. The author is happy.B. The author is sad.C. The author is angry.D. The author is surprised.11. A. The author is a teacher.B. The author is a student.C. The author is a parent.D. The author is a doctor.12. A. The passage is about a book.B. The passage is about a movie.C. The passage is about a play.D. The passage is about a song.Part 2: Reading Comprehension (25 points)Section 1: Multiple-Choice Questions (15 points) Read the following passage and answer the questions.13. What is the main idea of the passage?A. The author is traveling to a new country.B. The author is exploring a new city.C. The author is learning a new language.D. The author is meeting new people.14. Why does the author want to learn a new language?A. To travel to new countries.B. To explore new cities.C. To meet new people.D. To improve their communication skills.15. What is the author's favorite language?A. Spanish.B. French.C. German.D. Italian.Section 2: True or False Questions (10 points)Read the following passage and answer the questions.16. The author has traveled to many countries.17. The author wants to learn a new language to travel to new countries.18. The author's favorite language is French.19. The author is learning a new language to improve their communication skills.20. The author has met many new people while traveling.Part 3: Writing (50 points)21. Write a letter to a friend describing your favorite place to visit. Include details about the place, why you like it, and what you do there.22. Write an essay about the importance of learning a second language. Include reasons why learning a second language is important, how it can benefit you, and examples of people who have learned a second language.。

五年级英语哲学思考应用单选题50题

五年级英语哲学思考应用单选题50题1. Tom saw a poor man on the street. He thought about whether to give him some money. What is this kind of thinking called?A. Moral thinkingB. Scientific thinkingC. Artistic thinkingD. Historical thinking答案:A。

本题考查哲学中的道德思考。

选项A“Moral thinking”指的是道德思考,看到穷人并思考是否给予帮助属于道德范畴的思考。

选项B“ Scientific thinking”是科学思考,与帮助穷人的情境无关。

选项C“Artistic thinking”是艺术思考,不符合该情境。

选项D“Historical thinking”是历史思考,也不适用。

2. Mary broke her classmate's pen by accident. She thought about how to apologize. What kind of thinking is this?A. Logical thinkingB. Aesthetic thinkingC. Ethical thinkingD. Philosophical thinking答案:C。

本题考查伦理思考。

选项C“Ethical thinking”指的是伦理思考,因意外弄坏同学的笔并思考如何道歉,涉及到对行为对错及如何弥补的思考,属于伦理范畴。

选项A“Logical thinking”是逻辑思考,这里重点不是逻辑推理。

选项B“Aesthetic thinking”是美学思考,与道歉无关。

选项D“Philosophical thinking”哲学思考范围太宽泛,不具体针对此情境。

3. Jack saw a bird building a nest. He wondered why the bird did that. What kind of thinking is this?A. Curiosity-driven thinkingB. Practical thinkingC. Theoretical thinkingD. Abstract thinking答案:A。

Unit2BridginngCulturesUsinglanguage课件高中英语人教版选择性

While-reading

Read the text again and fill in the blanks.

Persons Opinions

Reasons

economic pressure and the pressure

Wang Disadvantages of studying abroad

★connectors 衔接词

How to write an argumentative letter?

salutatio

opinion

signature

reason1

details

reason2

details

reason3

details

conclusion

Use connectors(连接词)

第二部分 输入您的标题文字

LOGO

Connectors expressing opinion Point of view:in my opinionas far as l know /as far as I am concerned /personnally(speaking Summary:in short /to sum up /all in all in conclusion/summary generally speaking Restating:in other words/ that means that is to say

tips When you write an argumentative piece,use connecting phrases to lead readers through your process of reasoning.Good logical connectors will help your audience understand your point of view,whether they agree with you or not!

小学下册第15次英语第4单元真题

26.My dad is a _____ (商人) who travels internationally.

27.I want to be a _______ when I grow up (我长大后想成为_______).

19.The __________ is known for its preserved wildlife.

20.ers only bloom at ______ (晚上). Some flo

21.A ____ is a small creature that loves to play in the grass.

74.The chemical symbol for thulium is _____.

75.My favorite animal is a _______ (小猫) because it is so cute.

76.The ______ provides a habitat for many species.

61.The chemical formula for silicon dioxide is ______.

62.The chemical formula for ethylene glycol is ______.

63.The park is ________ and fun.

64.What do you call a place where books are kept?

77.What do we call a large area of land that is covered with grass?

A. DesertB. PrairieC. ForestD. WetlandB

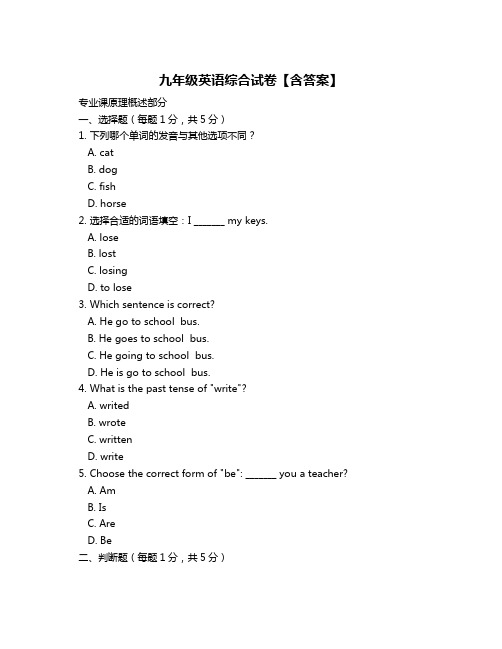

九年级英语综合试卷【含答案】

九年级英语综合试卷【含答案】专业课原理概述部分一、选择题(每题1分,共5分)1. 下列哪个单词的发音与其他选项不同?A. catB. dogC. fishD. horse2. 选择合适的词语填空:I _______ my keys.A. loseB. lostC. losingD. to lose3. Which sentence is correct?A. He go to school bus.B. He goes to school bus.C. He going to school bus.D. He is go to school bus.4. What is the past tense of "write"?A. writedB. wroteC. writtenD. write5. Choose the correct form of "be": _______ you a teacher?A. AmB. IsC. AreD. Be二、判断题(每题1分,共5分)1. "The cat is playing under the table." This sentence is in the present continuous tense. ( )2. "I have seen that movie three times." "Have" is the past tense here. ( )3. "She doesn't like apples." This means she likes apples. ( )4. "They are going to the park tomorrow." This sentence is about a future plan. ( )5. "Can you help me?" is a question. ( )三、填空题(每题1分,共5分)1. I _______ (to be) a doctor when I grow up.2. He _______ (to go) to the supermarket yesterday.3. They _______ (to watch) a movie now.4. We _______ (to have) a party next week.5. She _______ (to do) her homework every evening.四、简答题(每题2分,共10分)1. What is the difference between "I do" and "I am doing"?2. Write the past tense of "eat".3. How do you form the future tense with "will"?4. What is the plural form of "child"?5. Give an example of an adverb.五、应用题(每题2分,共10分)1. Translate: "Ellos van al cine mañana."2. Correct the mistake: "She don't like apples."3. Write a question: "You speak French."4. Make a negative sentence: "They play football every weekend."5. Change to indirect speech: "He sd, 'I am hungry.'"六、分析题(每题5分,共10分)1. Analyze the following sentence: "The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog."2. Expln the difference between "affect" and "effect".七、实践操作题(每题5分,共10分)1. Write a short dialogue between two people meeting for the first time.2. Describe your favorite hob, including why you like it and how often you do it.八、专业设计题(每题2分,共10分)1. 设计一个简单的英语学习计划,包括每天的学习内容和目标。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

An Answer to the Question: What is Enlightenment? (1784) Enlightenment is man's emergence from his self-imposed immaturity. Immaturity is the inability to use one's understanding without guidance from another. This immaturity is self-imposed when its cause lies not in lack of understanding, but in lack of resolve and courage to use it without guidance from another. Sapere Aude! [dare to know] "Have courage to use your own understanding!"--that is the motto of enlightenment.Laziness and cowardice are the reasons why so great a proportion of men, long after nature has released them from alien guidance (natura-liter maiorennes), nonetheless gladly remain in lifelong immaturity, and why it is so easy for others to establish themselves as their guardians. It is so easy to be immature. If I have a book to serve as my understanding, a pastor to serve as my conscience, a physician to determine my diet for me, and so on, I need not exert myself at all. I need not think, if only I can pay: others will readily undertake the irksome work for me. The guardians who have so benevolently taken over the supervision of men have carefully seen to it that the far greatest part of them (including the entire fair sex) regard taking the step to maturity as very dangerous, not to mention difficult. Having first made their domestic livestock dumb, and having carefully made sure that these docile creatures will not take a single step without the go-cart to which they are harnessed, these guardians then show them the danger that threatens them, should they attempt to walk alone. Now this danger is not actually so great, for after falling a few times they would in the end certainly learn to walk; but an example of this kind makes men timid and usually frightens them out of all further attempts.Thus, it is difficult for any individual man to work himself out of the immaturity that has all but become his nature. He has even become fond of this state and for the time being is actually incapable of using his own understanding, for no one has ever allowed him to attempt it. Rules and formulas, those mechanical aids to the rational use, or rather misuse, of his natural gifts, are the shackles of a permanent immaturity. Whoever threw them off would still make only an uncertain leap over the smallest ditch, since he is unaccustomed to this kind of free movement. Consequently, only a few have succeeded, by cultivating their own minds, in freeing themselves from immaturity and pursuing a secure course.But that the public should enlighten itself is more likely; indeed, if it is only allowed freedom, enlightenment is almost inevitable. For even among the entrenched guardians of the great masses a few will always think for themselves, a few who, after having themselves thrown off the yoke of immaturity, will spread the spirit of a rational appreciation for both their own worth and for each person's calling to think for himself. But it should be particularly noted that if a public that was first placed in this yoke by theguardians is suitably aroused by some of those who are altogether incapable of enlightenment, it may force the guardians themselves to remain under the yoke--so pernicious is it to instill prejudices, for they finally take revenge upon their originators, or on their descendants. Thus a public can only attain enlightenment slowly. Perhaps a revolution can overthrow autocratic despotism and profiteering or power-grabbing oppression, but it can never truly reform a manner of thinking; instead, new prejudices, just like the old ones they replace, will serve as a leash for the great unthinking mass. Nothing is required for this enlightenment, however, except freedom; and the freedom in question is the least harmful of all, namely, the freedom to use reason publicly in all matters. But on all sides I hear: "Do not argue!" The officer says, "Do not argue, drill!" The tax man says, "Do not argue, pay!" The pastor says, "Do not argue, believe!" (Only one ruler in the World says, "Argue as much as you want and about what you want, but obey!") In this we have examples of pervasive restrictions on freedom. But which restriction hinders enlightenment and which does not, but instead actually advances it? I reply: The public use of one's reason must always be free, and it alone can bring about enlightenment among mankind; the private use of reason may, however, often be very narrowly restricted, without otherwise hindering the progress of enlightenment. By the public use of one's own reason I understand the use that anyone as a scholar makes of reason before the entire literate world. I call the private use of reason that which a person may make in a civic post or office that has been entrusted to him. Now in many affairs conducted in the interests of a community, a certain mechanism is required by means of which some of its members must conduct themselves in an entirely passive manner so that through an artificial unanimity the government may guide them toward public ends, or at least prevent them from destroying such ends. Here one certainly must not argue, instead one must obey. However, insofar as this part of the machine also regards himself as a member of the community as a whole, or even of the world community, and as a consequence addresses the public in the role of a scholar, in the proper sense of that term, he can most certainly argue, without thereby harming the affairs for which as a passive member he is partly responsible. Thus it would be disastrous if an officer on duty who was given a command by his superior were to question the appropriateness or utility of the order. He must obey. But as a scholar he cannot be justly constrained from making comments about errors in military service, or from placing them before the public for its judgment. The citizen cannot refuse to pay the taxes imposed on him; indeed, impertinent criticism of such levies, when they should be paid by him, can be punished as a scandal (since it can lead to widespread insubordination). But the same person does not act contrary to civic duty when, as a scholar, he publicly expresses his thoughts regarding the impropriety or even injustice of such taxes. Likewise a pastor is bound to instruct his catecumens and congregation in accordance with the symbol of the church he serves, for he was appointed on thatcondition. But as a scholar he has complete freedom, indeed even the calling, to impart to the public all of his carefully considered and well-intentioned thoughts concerning mistaken aspects of that symbol, as well as his suggestions for the better arrangement of religious and church matters. Nothing in this can weigh on his conscience. What he teaches in consequence of his office as a servant of the church he sets out as something with regard to which he has no discretion to teach in accord with his own lights; rather, he offers it under the direction and in the name of another. He will say, "Our church teaches this or that and these are the demonstrations it uses." He thereby extracts for his congregation all practical uses from precepts to which he would not himself subscribe with complete conviction, but whose presentation he can nonetheless undertake, since it is not entirely impossible that truth lies hidden in them, and, in any case, nothing contrary to the very nature of religion is to be found in them. If he believed he could find anything of the latter sort in them, he could not in good conscience serve in his position; he would have to resign. Thus an appointed teacher's use of his reason for the sake of his congregation is merely private, because, however large the congregation is, this use is always only domestic; in this regard, as a priest, he is not free and cannot be such because he is acting under instructions from someone else. By contrast, the cleric--as a scholar who speaks through his writings to the public as such, i.e., the world--enjoys in this public use of reason an unrestricted freedom to use his own rational capacities and to speak his own mind. For that the (spiritual) guardians of a people should themselves be immature is an absurdity that would insure the perpetuation of absurdities.But would a society of pastors, perhaps a church assembly or venerable presbytery (as those among the Dutch call themselves), not be justified in binding itself by oath to a certain unalterable symbol in order to secure a constant guardianship over each of its members and through them over the people, and this for all time: I say that this is wholly impossible. Such a contract, whose intention is to preclude forever all further enlightenment of the human race, is absolutely null and void, even if it should be ratified by the supreme power, by parliaments, and by the most solemn peace treaties. One age cannot bind itself, and thus conspire, to place a succeeding one in a condition whereby it would be impossible for the later age to expand its knowledge (particularly where it is so very important), to rid itself of errors,and generally to increase its enlightenment. That would be a crime against human nature, whose essential destiny lies precisely in such progress; subsequent generations are thus completely justified in dismissing such agreements as unauthorized and criminal. The criterion of everything that can be agreed upon as a law by a people lies in this question: Can a people impose such a law on itself? Now it might be possible, in anticipation of a better state of affairs, to introduce a provisional order for a specific, short time, all the while giving all citizens, especially clergy, in their role as scholars, the freedom to comment publicly, i.e., in writing, on the present institution'sshortcomings. The provisional order might last until insight into the nature of these matters had become so widespread and obvious that the combined (if not unanimous) voices of the populace could propose to the crown that it take under its protection those congregations that, in accord with their newly gained insight, had organized themselves under altered religious institutions, but without interfering with those wishing to allow matters to remain as before. However, it is absolutely forbidden that they unite into a religious organization that nobody may for the duration of a man's lifetime publicly question, for so do-ing would deny, render fruitless, and make detrimental to succeeding generations an era in man's progress toward improvement. A man may put off enlightenment with regard to what he ought to know, though only for a short time and for his own person; but to renounce it for himself, or, even more, for subsequent generations, is to violate and trample man's divine rights underfoot. And what a people may not decree for itself may still less be imposed on it by a monarch, for his lawgiving authority rests on his unification of the people's collective will in his own. If he only sees to it that all genuine or purported improvement is consonant with civil order, he can allow his subjects to do what they find necessary to their spiritual well-being, which is not his affair. However, he must prevent anyone from forcibly interfering with another's working as best he can to determine and promote his well-being. It detracts from his own majesty when he interferes in these matters, since the writings in which his subjects attempt to clarify their insights lend value to his conception of governance. This holds whether he acts from his own highest insight--whereby he calls upon himself the reproach, "Caesar non eat supra grammaticos."'--as well as, indeed even more, when he despoils his highest authority by supporting the spiritual despotism of some tyrants in his state over his other subjects.If it is now asked, "Do we presently live in an enlightened age?" the answer is, "No, but we do live in an age of enlightenment." As matters now stand, a great deal is still lacking in order for men as a whole to be, or even to put themselves into a position to be able without external guidance to apply understanding confidently to religious issues. But we do have clear indications that the way is now being opened for men to proceed freely in this direction and that the obstacles to general enlightenment--to their release from their self-imposed immaturity--are gradually diminishing. In this regard, this age is the age of enlightenment, the century of Frederick.A prince who does not find it beneath him to say that he takes it to be his duty to prescribe nothing, but rather to allow men complete freedom in religious matters--who thereby renounces the arrogant title of tolerance--is himself enlightened and deserves to be praised by a grateful present and by posterity as the first, at least where the government is concerned, to release the human race from immaturity and to leave everyone free to use his own reason in all matters of conscience. Under his rule, venerable pastors, in their role asscholars and without prejudice to their official duties, may freely and openly set out for the world's scrutiny their judgments and views, even where these occasionally differ from the accepted symbol. Still greater freedom is afforded to those who are not restricted by an official post. This spirit of freedom is expanding even where it must struggle against the external obstacles of governments that misunderstand their own function. Such governments are illuminated by the example that the existence of freedom need not give cause for the least concern regarding public order and harmony in the commonwealth. If only they refrain from inventing artifices to keep themselves in it, men will gradually raise themselves from barbarism.I have focused on religious matters in setting out my main point concerning enlightenment, i.e., man's emergence from self-imposed immaturity, first because our rulers have no interest in assuming the role of their subjects' guardians with respect to the arts and sciences, and secondly because that form of immaturity is both the most pernicious and disgraceful of all. But the manner of thinking of a head of state who favors religious enlightenment goes even further, for he realizes that there is no danger to his legislation in allowing his subjects to use reason publicly and to set before the world their thoughts concerning better formulations of his laws, even if this involves frank criticism of legislation currently in effect. We have before us a shining example, with respect to which no monarch surpasses the one whom we honor.But only a ruler who is himself enlightened and has no dread of shadows, yet who likewise has a well-disciplined, numerous army to guarantee public peace, can say what no republic may dare, namely: "Argue as much as you want and about what you want, but obey!" Here as elsewhere, when things are considered in broad perspective, a strange, unexpected pattern in human affairs reveals itself, one in which almost everything is paradoxical. A greater degree of civil freedom seems advantageous to a people's spiritual freedom; yet the former established impassable boundaries for the latter; conversely, a lesser degree of civil freedom provides enough room for all fully to expand their abilities. Thus, once nature has removed the hard shell from this kernel for which she has most fondly cared, namely, the inclination to and vocation for free thinking, the kernel gradually reacts on a people's mentality (whereby they become increasingly able to act freely), and it finally even influences the principles of government, which finds that it can profit by treating men, who are now more than machines, in accord with their dignity.I. KantKonigsberg in Prussia, 30 September 1784。