高中生经典英文小说阅读欣赏与写作系列 The Father

高中生经典英文小说阅读欣赏与写作系列The Affair at Coulter's Notch

The Affair at Coulter's Notchby Ambrose Bierce"Do you think, Colonel, that your brave Coulter would like to put one of his guns in here?" the general asked.He was apparently not altogether serious; it certainly did not seem a place where any artillerist, however brave, would like to put a gun. The colonel thought that possibly his division commander meant good-humoredly to intimate that in a recent conversation between them Captain Coulter's courage had been too highly extolled."General," he replied warmly, "Coulter would like to put a gun anywhere within reach of those people," with a motion of his hand in the direction of the enemy."It is the only place," said the general. He was serious, then.The place was a depression, a "notch," in the sharp crest of a hill. It was a pass, and through it ran a turnpike, which reaching this highest point in its course by a sinuous ascent through a thin forest made a similar, though less steep, descent toward the enemy. For a mile to the left and a mile to the right, the ridge, though occupied by Federal infantry lying close behind the sharp crest and appearing as if held in place by atmospheric pressure, was inaccessible to artillery. There was no place but the bottom of the notch, and that was barely wide enough for the roadbed. From the Confederate side this point was commanded by two batteries posted on a slightly lower elevation beyond a creek, and a half-mile away. All the guns but one were masked by the trees of an orchard; that one--it seemed a bit of impudence--was on an open lawn directly in front of a rather grandiose building, the planter's dwelling. The gun was safe enough in its exposure--but only because the Federal infantry had been forbidden to fire. Coulter's Notch--it came to be called so--was not, that pleasant summer afternoon, a place where one would "like to put a gun."Three or four dead horses lay there sprawling in the road, three or four dead men in a trim row at one side of it, and a little back, down the hill. All but one were cavalrymen belonging to the Federal advance. One was a quartermaster. The general commanding the division and the colonel commanding the brigade, with their staffs and escorts, had ridden into the notch to have a look at the enemy's guns--which had straightway obscured themselves in towering clouds of smoke. It was hardly profitable to be curious about guns which had the trick of the cuttle-fish, and the season of observation had been brief. At its conclusion--a short remove backward from where it began--occurred the conversation already partly reported."It is the only place," the general repeated thoughtfully, "to get at them."The colonel looked at him gravely. "There is room for only one gun, General--one against twelve.""That is true--for only one at a time," said the commander with something like, yet not altogether like, a smile. "But then, your brave Coulter--a whole battery in himself."The tone of irony was now unmistakable. It angered the colonel, but he did not know what to say. The spirit of military subordination is not favorable to retort, nor even to deprecation.At this moment a young officer of artillery came riding slowly up the road attended by his bugler. It was Captain Coulter. He could not have been more than twenty-three years of age. He was of medium height, but very slender and lithe, and sat his horse with something of the air of a civilian. In face he was of a type singularly unlike the men about him; thin, high-nosed, gray-eyed, with a slight blond mustache, and long, rather straggling hair of the same color. There was an apparent negligence in his attire. His cap was worn with the visor a trifle askew; his coat was buttoned only at the sword-belt, showing a considerable expanse of white shirt, tolerably clean for that stage of the campaign. But the negligence was all in his dress and bearing; in his face was a look of intense interest in his surroundings. His gray eyes, which seemed occasionally to strike right and left across the landscape, like search-lights, were for the most part fixed upon the sky beyond the Notch; until he should arrive at the summit of the road there was nothing else in that direction to see. As he came opposite his division and brigade commanders at the road-side he saluted mechanically and was about to pass on. The colonel signed to him to halt."Captain Coulter," he said, "the enemy has twelve pieces over there on the next ridge. If I rightly understand the general, he directs that you bring up a gun and engage them."There was a blank silence; the general looked stolidly at a distant regiment swarming slowly up the hill through rough undergrowth, like a torn and draggled cloud of blue smoke; the captain appeared not to have observed him. Presently the captain spoke, slowly and with apparent effort:"On the next ridge, did you say, sir? Are the guns near the house?""Ah, you have been over this road before. Directly at the house.""And it is--necessary--to engage them? The order is imperative?"His voice was husky and broken. He was visibly paler. The colonel was astonished and mortified. He stole a glance at the commander. In that set, immobile face was no sign; it was as hard as bronze. A moment later the general rode away, followed by his staff and escort. The colonel, humiliated and indignant, was aboutto order Captain Coulter in arrest, when the latter spoke a few words in a low tone to his bugler, saluted, and rode straight forward into the Notch, where, presently, at the summit of the road, his field-glass at his eyes, he showed against the sky, he and his horse, sharply defined and statuesque. The bugler had dashed down the speed and disappeared behind a wood. Presently his bugle was heard singing in the cedars, and in an incredibly short time a single gun with its caisson, each drawn by six horses and manned by its full complement of gunners, came bounding and banging up the grade in a storm of dust, unlimbered under cover, and was run forward by hand to the fatal crest among the dead horses. A gesture of the captain's arm, some strangely agile movements of the men in loading, and almost before the troops along the way had ceased to hear the rattle of the wheels, a great white cloud sprang forward down the slope, and with a deafening report the affair at Coulter's Notch had begun.It is not intended to relate in detail the progress and incidents of that ghastly contest--a contest without vicissitudes, its alternations only different degrees of despair. Almost at the instant when Captain Coulter's gun blew its challenging cloud twelve answering clouds rolled upward from among the trees about the plantation house, a deep multiple report roared back like a broken echo, and thenceforth to the end the Federal cannoneers fought their hopeless battle in an atmosphere of living iron whose thoughts were lightnings and whose deeds were death.Unwilling to see the efforts which he could not aid and the slaughter which he could not stay, the colonel ascended the ridge at a point a quarter of a mile to the left, whence the Notch, itself invisible, but pushing up successive masses of smoke, seemed the crater of a volcano in thundering eruption. With his glass he watched the enemy's guns, noting as he could the effects of Coulter's fire--if Coulter still lived to direct it. He saw that the Federal gunners, ignoring those of the enemy's pieces whose positions could be determined by their smoke only, gave their whole attention to the one that maintained its place in the open--the lawn in front of the house. Over and about that hardy piece the shells exploded at intervals of a few seconds. Some exploded in the house, as could be seen by thin ascensions of smoke from the breached roof. Figures of prostrate men and horses were plainly visible."If our fellows are doing so good work with a single gun," said the colonel to an aide who happened to be nearest, "they must be suffering like the devil from twelve. Go down and present the commander of that piece with my congratulations on the accuracy of his fire."Turning to his adjutant-general he said, "Did you observe Coulter's damned reluctance to obey orders?""Yes, sir, I did.""Well, say nothing about it, please. I don't think the general will care to make any accusations. He will probably have enough to do in explaining his own connection with this uncommon way of amusing the rear-guard of a retreating enemy."A young officer approached from below, climbing breathless up the acclivity. Almost before he had saluted, he gasped out:"Colonel, I am directed by Colonel Harmon to say that the enemy's guns are within easy reach of our rifles, and most of them visible from several points along the ridge."The brigade commander looked at him without a trace of interest in his expression. "I know it," he said quietly.The young adjutant was visibly embarrassed. "Colonel Harmon would like to have permission to silence those guns," he stammered."So should I," the colonel said in the same tone. "Present my compliments to Colonel Harmon and say to him that the general's orders for the infantry not to fire are still in force."The adjutant saluted and retired. The colonel ground his heel into the earth and turned to look again at the enemy's guns."Colonel," said the adjutant-general, "I don't know that I ought to say anything, but there is something wrong in all this. Do you happen to know that Captain Coulter is from the South?""No; was he, indeed?""I heard that last summer the division which the general then commanded was in the vicinity of Coulter's home--camped there for weeks, and--""Listen!" said the colonel, interrupting with an upward gesture. "Do you hear that?""That" was the silence of the Federal gun. The staff, the orderlies, the lines of infantry behind the crest--all had "heard," and were looking curiously in the direction of the crater, whence no smoke now ascended except desultory cloudlets from the enemy's shells. Then came the blare of a bugle, a faint rattle of wheels; a minute later the sharp reports recommenced with double activity. The demolished gun had been replaced with a sound one."Yes," said the adjutant-general, resuming his narrative, "the general made the acquaintance of Coulter's family. There was trouble--I don't know the exact nature of it--something about Coulter's wife. She is a red-hot Secessionist, as they all are, except Coulter himself, but she is a good wife and high-bred lady. There was a complaint to army headquarters. The general was transferred to this division. It is odd that Coulter's battery should afterward have been assigned to it."The colonel had risen from the rock upon which they had been sitting. His eyeswere blazing with a generous indignation."See here, Morrison," said he, looking his gossiping staff officer straight in the face, "did you get that story from a gentleman or a liar?""I don't want to say how I got it, Colonel, unless it is necessary"--he was blushing a trifle--"but I'll stake my life upon its truth in the main."The colonel turned toward a small knot of officers some distance away. "Lieutenant Williams!" he shouted.One of the officers detached himself from the group and coming forward saluted, saying: "Pardon me, Colonel, I thought you had been informed. Williams is dead down there by the gun. What can I do, sir?"Lieutenant Williams was the aide who had had the pleasure of conveying to the officer in charge of the gun his brigade commander's congratulations."Go," said the colonel, "and direct the withdrawal of that gun instantly. No--I'll go myself."He strode down the declivity toward the rear of the Notch at a break-neck pace, over rocks and through brambles, followed by his little retinue in tumultuous disorder. At the foot of the declivity they mounted their waiting animals and took to the road at a lively trot, round a bend and into the Notch. The spectacle which they encountered there was appalling!Within that defile, barely broad enough for a single gun, were piled the wrecks of no fewer than four. They had noted the silencing of only the last one disabled--there had been a lack of men to replace it quickly with another. The dbris lay on both sides of the road; the men had managed to keep an open way between, through which the fifth piece was now firing. The men?--they looked like demons of the pit! All were hatless, all stripped to the waist, their reeking skins black with blotches of powder and spattered with gouts of blood. They worked like madmen, with rammer and cartridge, lever and lanyard. They set their swollen shoulders and bleeding hands against the wheels at each recoil and heaved the heavy gun back to its place. There were no commands; in that awful environment of whooping shot, exploding shells, shrieking fragments of iron, and flying splinters of wood, none could have been heard. Officers, if officers there were, were indistinguishable; all worked together--each while he lasted--governed by the eye. When the gun was sponged, it was loaded; when loaded, aimed and fired. The colonel observed something new to his military experience--something horrible and unnatural: the gun was bleeding at the mouth! In temporary default of water, the man sponging had dipped his sponge into a pool of comrade's blood. In all this work there was no clashing; the duty of the instant was obvious. When one fell, another, looking a trifle cleaner, seemed to rise from the earth in the dead man's tracks, to fall in his turn.With the ruined guns lay the ruined men--alongside the wreckage, under it and atop of it; and back down the road--a ghastly procession!--crept on hands and knees such of the wounded as were able to move. The colonel--he had compassionately sent his cavalcade to the right about-- had to ride over those who were entirely dead in order not to crush those who were partly alive. Into that hell he tranquilly held his way, rode up alongside the gun, and, in the obscurity of the last discharge, tapped upon the cheek the man holding the rammer--who straightway fell, thinking himself killed. A fiend seven times damned sprang out of the smoke to take his place, but paused and gazed up at the mounted officer with an unearthly regard, his teeth flashing between his black lips, his eyes, fierce and expanded, burning like coals beneath his bloody brow. The colonel made an authoritative gesture and pointed to the rear. The fiend bowed in token of obedience. It was Captain Coulter.Simultaneously with the colonel's arresting sign, silence fell upon the whole field of action. The procession of missiles no longer streamed into that defile of death, for the enemy also had ceased firing. His army had been gone for hours, and the commander of his rear-guard, who had held his position perilously long in hope to silence the Federal fire, at that strange moment had silenced his own. "I was not aware of the breadth of my authority," said the colonel to anybody, riding forward to the crest to see what had really happened. An hour later his brigade was in bivouac on the enemy's ground, and its idlers were examining, with something of awe, as the faithful inspect a saint's relics, a score of straddling dead horses and three disabled guns, all spiked. The fallen men had been carried away; their torn and broken bodies would have given too great satisfaction.Naturally, the colonel established himself and his military family in the plantation house. It was somewhat shattered, but it was better than the open air. The furniture was greatly deranged and broken. Walls and ceilings were knocked away here and there, and a lingering odor of powder smoke was everywhere. The beds, the closets of women's clothing, the cupboards were not greatly dam-aged. The new tenants for a night made themselves comfortable, and the virtual effacement of Coulter's battery supplied them with an interesting topic.During supper an orderly of the escort showed himself into the dining-room and asked permission to speak to the colonel."What is it, Barbour?" said that officer pleasantly, having overheard the request."Colonel, there is something wrong in the cellar; I don't know what-- somebody there. I was down there rummaging about.""I will go down and see," said a staff officer, rising."So will I," the colonel said; "let the others remain. Lead on, orderly."They took a candle from the table and descended the cellar stairs, the orderly invisible trepidation. The candle made but a feeble light, but presently, as they advanced, its narrow circle of illumination revealed a human figure seated on the ground against the black stone wall which they were skirting, its knees elevated, its head bowed sharply forward. The face, which should have been seen in profile, was invisible, for the man was bent so far forward that his long hair concealed it; and, strange to relate, the beard, of a much darker hue, fell in a great tangled mass and lay along the ground at his side. They involuntarily paused; then the colonel, taking the candle from the orderly's shaking hand, approached the man and attentively considered him. The long dark beard was the hair of a woman--dead. The dead woman clasped in her arms a dead babe. Both were clasped in the arms of the man, pressed against his breast, against his lips. There was blood in the hair of the woman; there was blood in the hair of the man. A yard away, near an irregular depression in the beaten earth which formed the cellar's floor--fresh excavation with a convex bit of iron, having jagged edges, visible in one of the sides--lay an infant's foot. The colonel held the light as high as he could. The floor of the room above was broken through, the splinters pointing at all angles downward. "This casemate is not bomb-proof," said the colonel gravely. It did not occur to him that his summing up of the matter had any levity in it.They stood about the group awhile in silence; the staff officer was thinking of his unfinished supper, the orderly of what might possibly be in one of the casks on the other side of the cellar. Suddenly the man whom they had thought dead raised his head and gazed tranquilly into their faces. His complexion was coal black; the cheeks were apparently tattooed in irregular sinuous lines from the eyes downward. The lips, too, were white, like those of a stage negro. There was blood upon his forehead.The staff officer drew back a pace, the orderly two paces."What are you doing here, my man?" said the colonel, unmoved."This house belongs to me, sir," was the reply, civilly delivered."To you? Ah, I see! And these?""My wife and child. I am Captain Coulter."。

父与子高中英语读后感

父与子高中英语读后感After reading "Father and Son" in high school, I was deeply moved by the complex relationship between the father and the son. The story depicts the struggles and conflicts that arise between the two characters as they try to understand each other and find common ground. It also highlights the importance of communication and empathy in maintaining a healthy relationship.The father, who is a strict and traditional man, hashigh expectations for his son. He wants his son to followin his footsteps and take over the family business. However, the son has different dreams and aspirations, which creates tension between them. The son feels pressured to live up to his father's expectations, while the father struggles to accept his son's choices.Throughout the story, the son tries to bridge the gap between himself and his father by expressing his thoughts and feelings. He seeks his father's approval and understanding, but often feels rejected and misunderstood. The father, on the other hand, is portrayed as a man of fewwords, making it difficult for the son to connect with him on a deeper level.As the story unfolds, we see the father and songrappling with their differences and trying to find a wayto reconcile their conflicting desires. It is a powerful reminder of the complexity of parent-child relationshipsand the challenges of generational gaps.This story made me reflect on the importance of open communication and mutual respect in family dynamics. Italso shed light on the struggles that many young peopleface when trying to assert their independence while seeking validation from their parents. The story serves as a poignant reminder that understanding and acceptance are crucial in fostering strong and healthy relationshipswithin a family.阅读完《父与子》这篇文章后,我深受父子之间复杂关系的感动。

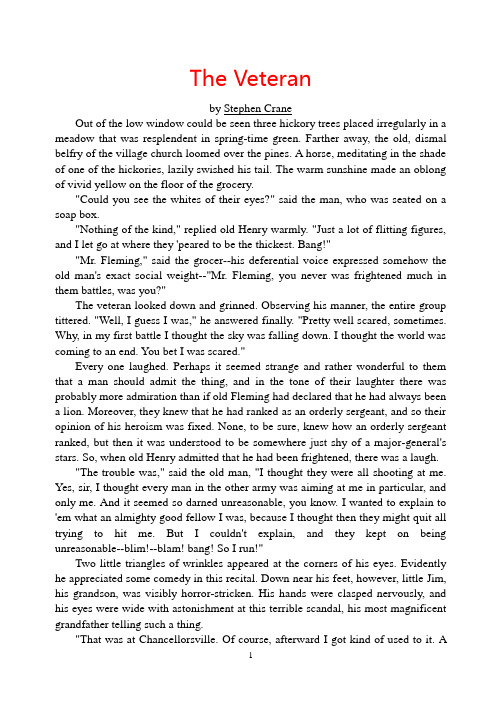

高中生经典英文小说阅读与欣赏系列 The Veteran

The Veteranby Stephen CraneOut of the low window could be seen three hickory trees placed irregularly in a meadow that was resplendent in spring-time green. Farther away, the old, dismal belfry of the village church loomed over the pines. A horse, meditating in the shade of one of the hickories, lazily swished his tail. The warm sunshine made an oblong of vivid yellow on the floor of the grocery."Could you see the whites of their eyes?" said the man, who was seated on a soap box."Nothing of the kind," replied old Henry warmly. "Just a lot of flitting figures, and I let go at where they 'peared to be the thickest. Bang!""Mr. Fleming," said the grocer--his deferential voice expressed somehow the old man's exact social weight--"Mr. Fleming, you never was frightened much in them battles, was you?"The veteran looked down and grinned. Observing his manner, the entire group tittered. "Well, I guess I was," he answered finally. "Pretty well scared, sometimes. Why, in my first battle I thought the sky was falling down. I thought the world was coming to an end. You bet I was scared."Every one laughed. Perhaps it seemed strange and rather wonderful to them that a man should admit the thing, and in the tone of their laughter there was probably more admiration than if old Fleming had declared that he had always been a lion. Moreover, they knew that he had ranked as an orderly sergeant, and so their opinion of his heroism was fixed. None, to be sure, knew how an orderly sergeant ranked, but then it was understood to be somewhere just shy of a major-general's stars. So, when old Henry admitted that he had been frightened, there was a laugh."The trouble was," said the old man, "I thought they were all shooting at me. Yes, sir, I thought every man in the other army was aiming at me in particular, and only me. And it seemed so darned unreasonable, you know. I wanted to explain to 'em what an almighty good fellow I was, because I thought then they might quit all trying to hit me. But I couldn't explain, and they kept on being unreasonable--blim!--blam! bang! So I run!"Two little triangles of wrinkles appeared at the corners of his eyes. Evidently he appreciated some comedy in this recital. Down near his feet, however, little Jim, his grandson, was visibly horror-stricken. His hands were clasped nervously, and his eyes were wide with astonishment at this terrible scandal, his most magnificent grandfather telling such a thing."That was at Chancellorsville. Of course, afterward I got kind of used to it. Aman does. Lots of men, though, seem to feel all right from the start. I did, as soon as I 'got on to it,' as they say now; but at first I was pretty well flustered. Now, there was young Jim Conklin, old Si Conklin's son--that used to keep the tannery--you none of you recollect him--well, he went into it from the start just as if he was born to it. But with me it was different. I had to get used to it."When little Jim walked with his grandfather he was in the habit of skipping along on the stone pavement, in front of the three stores and the hotel of the town, and betting that he could avoid the cracks. But upon this day he walked soberly, with his hand gripping two of his grandfather's fingers. Sometimes he kicked abstractedly at dandelions that curved over the walk. Any one could see that he was much troubled."There's Sickles's colt over in the medder, Jimmie," said the old man. "Don't you wish you owned one like him?""Um," said the boy, with a strange lack of interest. He continued his reflections. Then finally he ventured: "Grandpa--now--was that true what you was telling those men?""What?" asked the grandfather. "What was I telling them?""Oh, about your running.""Why, yes, that was true enough, Jimmie. It was my first fight, and there was an awful lot of noise, you know."Jimmie seemed dazed that this idol, of its own will, should so totter. His stout boyish idealism was injured.Presently the grandfather said: "Sickles's colt is going for a drink. Don't you wish you owned Sickles's colt, Jimmie?"The boy merely answered: "He ain't as nice as our'n." He lapsed then into another moody silence.* * * * *One of the hired men, a Swede, desired to drive to the county seat for purposes of his own. The old man loaned a horse and an unwashed buggy. It appeared later that one of the purposes of the Swede was to get drunk.After quelling some boisterous frolic of the farm hands and boys in the garret, the old man had that night gone peacefully to sleep, when he was aroused by clamouring at the kitchen door. He grabbed his trousers, and they waved out behind as he dashed forward. He could hear the voice of the Swede, screaming and blubbering. He pushed the wooden button, and, as the door flew open, the Swede, a maniac, stumbled inward, chattering, weeping, still screaming: "De barn fire! Fire! Fire! De barn fire! Fire! Fire! Fire!"There was a swift and indescribable change in the old man. His face ceased instantly to be a face; it became a mask, a grey thing, with horror written about themouth and eyes. He hoarsely shouted at the foot of the little rickety stairs, and immediately, it seemed, there came down an avalanche of men. No one knew that during this time the old lady had been standing in her night-clothes at the bedroom door, yelling: "What's th' matter? What's th' matter? What's th' matter?"When they dashed toward the barn it presented to their eyes its usual appearance, solemn, rather mystic in the black night. The Swede's lantern was overturned at a point some yards in front of the barn doors. It contained a wild little conflagration of its own, and even in their excitement some of those who ran felt a gentle secondary vibration of the thrifty part of their minds at sight of this overturned lantern. Under ordinary circumstances it would have been a calamity.But the cattle in the barn were trampling, trampling, trampling, and above this noise could be heard a humming like the song of innumerable bees. The old man hurled aside the great doors, and a yellow flame leaped out at one corner and sped and wavered frantically up the old grey wall. It was glad, terrible, this single flame, like the wild banner of deadly and triumphant foes.The motley crowd from the garret had come with all the pails of the farm. They flung themselves upon the well. It was a leisurely old machine, long dwelling in indolence. It was in the habit of giving out water with a sort of reluctance. The men stormed at it, cursed it; but it continued to allow the buckets to be filled only after the wheezy windlass had howled many protests at the mad-handed men.With his opened knife in his hand old Fleming himself had gone headlong into the barn, where the stifling smoke swirled with the air currents, and where could be heard in its fulness the terrible chorus of the flames, laden with tones of hate and death, a hymn of wonderful ferocity.He flung a blanket over an old mare's head, cut the halter close to the manger, led the mare to the door, and fairly kicked her out to safety. He returned with the same blanket, and rescued one of the work horses. He took five horses out, and then came out himself, with his clothes bravely on fire. He had no whiskers, and very little hair on his head. They soused five pailfuls of water on him. His eldest son made a clean miss with the sixth pailful, because the old man had turned and was running down the decline and around to the basement of the barn, where were the stanchions of the cows. Some one noticed at the time that he ran very lamely, as if one of the frenzied horses had smashed his hip.The cows, with their heads held in the heavy stanchions, had thrown themselves, strangled themselves, tangled themselves--done everything which the ingenuity of their exuberant fear could suggest to them.Here, as at the well, the same thing happened to every man save one. Their hands went mad. They became incapable of everything save the power to rush into dangerous situations.The old man released the cow nearest the door, and she, blind drunk with terror, crashed into the Swede. The Swede had been running to and fro babbling. He carried an empty milk-pail, to which he clung with an unconscious, fierce enthusiasm. He shrieked like one lost as he went under the cow's hoofs, and the milk-pail, rolling across the floor, made a flash of silver in the gloom.Old Fleming took a fork, beat off the cow, and dragged the paralysed Swede to the open air. When they had rescued all the cows save one, which had so fastened herself that she could not be moved an inch, they returned to the front of the barn, and stood sadly, breathing like men who had reached the final point of human effort.Many people had come running. Some one had even gone to the church, and now, from the distance, rang the tocsin note of the old bell. There was a long flare of crimson on the sky, which made remote people speculate as to the whereabouts of the fire.The long flames sang their drumming chorus in voices of the heaviest bass. The wind whirled clouds of smoke and cinders into the faces of the spectators. The form of the old barn was outlined in black amid these masses of orange-hued flames.And then came this Swede again, crying as one who is the weapon of the sinister fates: "De colts! De colts! You have forgot de colts!"Old Fleming staggered. It was true: they had forgotten the two colts in the box-stalls at the back of the barn. "Boys," he said, "I must try to get 'em out." They clamoured about him then, afraid for him, afraid of what they should see. Then they talked wildly each to each. "Why, it's sure death!" "He would never get out!" "Why, it's suicide for a man to go in there!" Old Fleming stared absent-mindedly at the open doors. "The poor little things!" he said. He rushed into the barn.When the roof fell in, a great funnel of smoke swarmed toward the sky, as if the old man's mighty spirit, released from its body--a little bottle--had swelled like the genie of fable. The smoke was tinted rose- hue from the flames, and perhaps the unutterable midnights of the universe will have no power to daunt the colour of this soul.。

讲述父爱的英文小说作文

讲述父爱的英文小说作文英文:Fatherly love is something that cannot be described in words. It is a feeling that is beyond explanation and can only be experienced. My father has always been the pillar of strength in my life, and his love has been my guiding light. He has always been there for me, through thick and thin, and has never once let me down.One of the most memorable instances of my father's love was when I was going through a tough time in my life. I was struggling with my studies and was feeling demotivated. My father sensed my distress and took me out for a walk. We talked about everything under the sun, and he gave me some valuable advice that I still remember to this day. He told me that failure is not the end of the road and that I should never give up on my dreams.Another example of my father's love was when I got intoa car accident. I was shaken and scared, but my father rushed to the scene and stayed with me until everything was sorted out. He held my hand and told me that everything was going to be okay. His presence gave me the strength to get through that difficult time.My father's love is unconditional, and he has always been my biggest cheerleader. He has taught me to be strong, independent, and to never give up on myself. He has always been there to pick me up when I fall and has never once judged me for my mistakes. I am grateful for his love and support, and I know that I can always count on him to be there for me.中文:父爱是一种无法用言语描述的感觉。

2024届高三英语二轮复习读后续写亲情类—父亲的爱讲义素材

2024届高三英语二轮复习读后续写亲情类—父亲的爱讲义素材读后续写原文中文He was 50 years old when I was born. I didn't know why he was home instead of Mom, but I was young and the only one of my friends who had their dad around. I considered myself very lucky. 我出生时他已经50岁了。

我不知道他为什么在家而不是妈妈呆在家里,但我还小,而且我是我所有朋友中唯一一个父亲在身边的。

我觉得自己非常幸运。

Dad did so many things for me during my grade school years. He convinced the school bus driver to pick me up at my house instead of the usual bus stop that was six blocks away. He always had my lunch ready for me when I came home. 在我小学的岁月里,爸爸为我做了很多事情。

他说服校车司机在我家接我,而不是在离家六个街区的常规公交车站。

每当我回家,他总是有我的午餐准备好。

As I got a little older, I wanted to move away from those "childish" signs of his love. But he wasn't going to give up. 随着我慢慢长大,我想摆脱他那些“孩子气”的爱的表现。

但他并未放弃。

In high school and no longer able to go home for lunch, I began taking my own. Dad would get up a little earlier and make it for me. The outside of the sack might be covered with a heart inscribed with "Dad-n-Angie K. K. ". Inside there would be a napkin with that same heart or an "I loveyou." 在高中,我不能再回家吃午饭,我开始自己带饭。

2024年高中英语作文《我的父亲》

My father is a man of many facets, a figure who has influenced my life in ways that are both profound and subtle. Hes not just a father hes a mentor, a friend, and a source of endless inspiration. Growing up, Ive seen him as a towering presence, guiding me through the complexities of life with wisdom and patience.As a child, I was always in awe of my fathers work ethic. He would rise before the sun, ready to tackle the day with a vigor that seemed almost superhuman. His dedication to his job was unwavering, and it taught me the value of hard work and commitment. I remember the countless evenings when he would come home exhausted, yet he never failed to ask about my day or help me with my homework. His tireless nature was a testament to his strength and resilience, qualities that I have come to admire and strive to emulate.One of the most significant lessons I learned from my father was the importance of integrity. He always emphasized the need to be honest, even when it was difficult. There were times when I was tempted to take shortcuts or bend the truth, but my fathers example made me realize that honesty is the foundation of trust and respect. His unwavering commitment to doing the right thing, even when no one was watching, has been a guiding principle in my life.My father was also a man of few words, but when he spoke, his words carried weight. He believed in the power of silence and the value of thoughtful reflection. This has taught me to be mindful of the words I choose and to consider the impact they may have on others. His quietstrength and introspective nature have shaped my approach to communication and conflict resolution.Beyond his work and personal values, my father was also a man of many talents. He had a knack for fixing things around the house, from a broken faucet to a malfunctioning appliance. His ability to solve problems and create solutions inspired me to be resourceful and innovative. Ive learned that with a bit of creativity and determination, theres always a way to overcome obstacles.One of the most vivid memories I have of my father is his love for the outdoors. He would often take me on hikes and camping trips, teaching me to appreciate the beauty of nature and the importance of preserving our environment. These experiences instilled in me a deep respect for the natural world and a desire to protect it for future generations.My fathers influence extends beyond just his actions and words. His presence has been a constant source of comfort and reassurance. There were times when I felt lost or unsure of my path, but my fathers unwavering support and belief in me gave me the courage to face my fears and pursue my dreams.In conclusion, my father has been a beacon of inspiration, guiding me through life with his wisdom, strength, and love. He has taught me the importance of hard work, integrity, and resilience, and has shown me the value of silence and reflection. His love for the outdoors and his resourcefulness have inspired me to be innovative and protective of ourenvironment. Above all, his unwavering support and belief in me have given me the courage to face lifes challenges headon. My father is not just a role model he is the embodiment of the best qualities a person can possess, and I am grateful for every lesson he has imparted to me.。

打开父亲这本书作文

打开父亲这本书作文英文回答:Opening the book written by my father, I am immediately transported into a world of memories and emotions. The words on the pages seem to come alive, as if my father is right there beside me, sharing his wisdom and experiences. It is a treasure trove of knowledge and insight, and I am grateful to have this opportunity to delve into his thoughts and ideas.As I flip through the pages, I am struck by the depth and breadth of topics covered in the book. From personal anecdotes to philosophical musings, my father's words resonate with me on a profound level. He has a unique way of capturing the essence of life and distilling it into simple, yet powerful, messages. I find myself nodding in agreement and reflecting on my own experiences as I read each chapter.One of the things that stands out to me is my father's emphasis on the importance of family. He writes about the unconditional love and support that parents provide, and how it shapes us into the individuals we become. This resonates with me deeply, as I have always felt fortunate to have a loving and supportive family. My father's words serve as a reminder to cherish and nurture these relationships, as they are the foundation of our happiness and well-being.Another theme that runs through the book is the power of perseverance and resilience. My father shares stories of his own struggles and challenges, and how he overcame them through sheer determination and hard work. This serves as a source of inspiration for me, as I navigate my own path in life. It reminds me that success is not always easy or immediate, but with perseverance, anything is possible.Furthermore, my father's book delves into the complexities of human relationships. He explores the dynamics of friendships, romantic relationships, and even professional connections. He offers insights on how tonavigate these relationships with empathy, understanding, and open communication. This resonates with me, as I have experienced both the joys and challenges of various relationships in my own life. My father's words serve as a guide, reminding me of the importance of nurturing these connections and approaching them with kindness and respect.In conclusion, opening my father's book is like opening a window into his soul. The words he has written are a testament to his wisdom, experiences, and love. I amgrateful to have this opportunity to learn from him and to carry his words with me as I navigate my own journey. My father's book is not just a collection of words on a page, but a legacy that will continue to inspire and guide me throughout my life.中文回答:打开父亲这本书,我立刻被带入了一个充满回忆和情感的世界。

英语阅读文章MyFather父爱无边

英语阅读文章MyFather父爱无边英语阅读文章My Father父爱无边My father was a self-taught mandolin player. He was oneof the best string instrument players in our town. He could not read music, but if he heard a tune a few times, he could play it. When he was younger, he was a member of a small country music band. They would play at local dances and on a few occasions would play for the local radio station. He often told us how he had auditioned and earned a position ina band that featured Patsy Cline as their lead singer. Hetold the family that after he was hired he never went back. Dad was a very religious man. He stated that there was a lot of drinking and cursing the day of his audition and he didnot want to be around that type of environment.Occasionally, Dad would get out his mandolin and play for the family. We three children: Trisha, Monte and I, George Jr., would often sing along. Songs such as the Tennessee Waltz, Harbor Lights and around Christmas time, the well-known rendition of Silver Bells. "Silver Bells, Silver Bells, its Christmas time in the city" would ring throughout the house. One of Dad's favorite hymns was "The Old Rugged Cross". We learned the words to the hymn when we were very young, and would sing it with Dad when he would play and sing. Another song that was often shared in our house was a song that accompanied the Walt Disney series: Davey Crockett. Dad only had to hear the song twice before he learned it well enoughto play it. "Davey, Davey Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier" was a favorite song for the family. He knew we enjoyed the songand the program and would often get out the mandolin after the program was over. I could never get overhow he could play the songs so well after only hearing them a few times. I loved to sing, but I never learned how to play the mandolin. This is something I regret to this day.Dad loved to play the mandolin for his family he knew we enjoyed singing, and hearing him play. He was like that. If he could give pleasure to others, he would, especially his family. He was always there, sacrificing his time and efforts to see that his family had enough in their life. I had to mature into a man and have children of my own before I realized how much he had sacrificed.I joined the United States Air Force in January of 1962. Whenever I would come home on leave, I would ask Dad to play the mandolin. Nobody played the mandolin like my father. He could touch your soul with the tones that came out of that old mandolin. He seemed to shine when he was playing. You could see his pride in his ability to play so well for his family.When Dad was younger, he worked for his father on the farm. His father was a farmer and sharecropped a farm for the man who owned the property. In 1950, our family moved from the farm. Dad had gained employment at the local limestone quarry. When the quarry closed in August of 1957, he had to seek other employment. He worked for Owens Yacht Company in Dundalk, Maryland and for Todd Steel in Point of Rocks, Maryland. While working at Todd Steel, he was involved in an accident. His job was to roll angle iron onto a conveyor so that the welders farther up the production line would have it to complete their job. On this particular day Dad got the third index finger of his left hand mashed between two piecesof steel. The doctor who operated on the finger could not save it, and Dad ended up having the tip of the finger amputated. He didn't lose enough of the finger where it would stop him picking up anything, but it did impact his ability to play the mandolin.After the accident, Dad was reluctant to play the mandolin. He felt that he could not play as well as he had before the accident. When I came home on leave and asked him to play he would make excuses for why he couldn't play. Eventually, we would wear him down and he would say "Okay, but remember, I can't hold down on the strings the way I used to" or "Since the accident to this finger I can't play as good". For the family it didn't make any difference that Dad couldn't play as well. We were just glad that he would play. When he played the old mandolin it would carry us back to a cheerful, happier time in our lives. "Davey, Davey Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier", would again be heard in thelittle town of Bakerton, West Virginia.In August of 1993 my father was diagnosed with inoperable lung cancer. He chose not to receive chemotherapy treatments so that he could live out the rest of his life in dignity. About a week before his death, we asked Dad if he would play the mandolin for us. He made excuses but said "okay". He knew it would probably be the last time he would play for us. He tuned up the old mandolin and played a few notes. When I looked around, there was not a dry eye in the family. We saw before us a quiet humble man with an inner strength that comes from knowing God, and living with him in one's life. Dad would never play the mandolin for us again. We felt at the time that he wouldn't have enough strength to play, and。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

The Fatherby Bjørnstjerne BjørnsonTHE man whose story is here to be told was the wealthiest and most influential person in his parish; his name was Thord Overaas. He appeared in the priest's study one day, tall and earnest. "I have gotten a son," said he, "and I wish to present him for baptism.""What shall his name be?""Finn,—after my father.""And the sponsors?"They were mentioned, and proved to be the best men and women of Thord's relations in the parish."Is there anything else?" inquired the priest, and looked up.The peasant hesitated a little."I should like very much to have him baptized by himself," said he, finally."That is to say on a week-day?""Next Saturday, at twelve o'clock noon.""Is there anything else?" inquired the priest."There is nothing else;" and the peasant twirled his cap, as though he were about to go.Then the priest rose. "There is yet this, however," said he, and walking toward Thord, he took him by the hand and looked gravely into his eyes: "God grant that the child may become a blessing to you!"One day sixteen years later, Thord stood once more in the priest's study."Really, you carry your age astonishingly well, Thord," said the priest; for he saw no change whatever in the man."That is because I have no troubles," replied Thord.To this the priest said nothing, but after a while he asked: "What is your pleasure this evening?""I have come this evening about that son of mine who is to be confirmed to-morrow.""He is a bright boy.""I did not wish to pay the priest until I heard what number the boy would have when he takes his place in church to-morrow.""He will stand number one.'"So I have heard; and here are ten dollars for the priest.""Is there anything else I can do for you?" inquired the priest, fixing his eyes on Thord."There is nothing else."Thord went out.Eight years more rolled by, and then one day a noise was heard outside of the priest's study, for many men were approaching, and at their head was Thord, who entered first.The priest looked up and recognized him."You come well attended this evening, Thord,""I am here to request that the banns may be published for my son; he is about to marry Karen Storliden, daughter of Gudmund, who stands here beside me.""Why, that is the richest girl in the parish.""So they say," replied the peasant, stroking back his hair with one hand.The priest sat a while as if in deep thought, then entered the names in his book, without making any comments, and the men wrote their signatures underneath. Thord laid three dollars on the table."One is all I am to have," said the priest."I know that very well; but he is my only child, I want to do it handsomely."The priest took the money."This is now the third time, Thord, that you have come here on your son's account.""But now I am through with him," said Thord, and folding up his pocket-book he said farewell and walked away.The men slowly followed him.A fortnight later, the father and son were rowing across the lake, one calm, still day, to Storliden to make arrangements for the wedding."This thwart is not secure," said the son, and stood up to straighten the seat on which he was sitting.At the same moment the board he was standing on slipped from under him; he threw out his arms, uttered a shriek, and fell overboard."Take hold of the oar!" shouted the father, springing to his feet and holding out the oar.But when the son had made a couple of efforts he grew stiff."Wait a moment!" cried the father, and began to row toward his son.Then the son rolled over on his back, gave his father one long look, and sank.Thord could scarcely believe it; he held the boat still, and stared at the spot where his son had gone down, as though he must surely come to the surface again. There rose some bubbles, then some more, and finally one large one that burst; and the lake lay there as smooth and bright as a mirror again.For three days and three nights people saw the father rowing round and round the spot, without taking either food or sleep; he was dragging the lake for the bodyof his son. And toward morning of the third day he found it, and carried it in his arms up over the hills to his gard.It might have been about a year from that day, when the priest, late one autumn evening, heard some one in the passage outside of the door, carefully trying to find the latch. The priest opened the door, and in walked a tall, thin man, with bowed form and white hair. The priest looked long at him before he recognized him. It was Thord."Are you out walking so late?" said the priest, and stood still in front of him."Ah, yes! it is late," said Thord, and took a seat.The priest sat down also, as though waiting. A long, long silence followed. At last Thord said:"I have something with me that I should like to give to the poor; I want it to be invested as a legacy in my son's name."He rose, laid some money on the table, and sat down again. The priest counted it."It is a great deal of money," said he."It is half the price of my gard. I sold it today."The priest sat long in silence. At last he asked, but gently:"What do you propose to do now, Thord?""Something better."They sat there for a while, Thord with downcast eyes, the priest with his eyes fixed on Thord. Presently the priest said, slowly and softly:"I think your son has at last brought you a true blessing.""Yes, I think so myself," said Thord, looking up, while two big tears coursed slowly down his cheeks.。