Diogenes and Alexander

Unit 4 Diogenes and Alexander教学教材

Background

➢ The first philosopher to outline these themes was Antisthenes (安提西尼), a pupil of Socrates in the late 5th century BC.

➢ He was followed by Diogenes of Sinope. ➢ Diogenes took Cynicism to its logical extremes and ➢ was followed by Crates of Thebes (克拉特斯). ➢ It disappeared in the late 5th century ➢ although some have claimed that early Christianity adopted

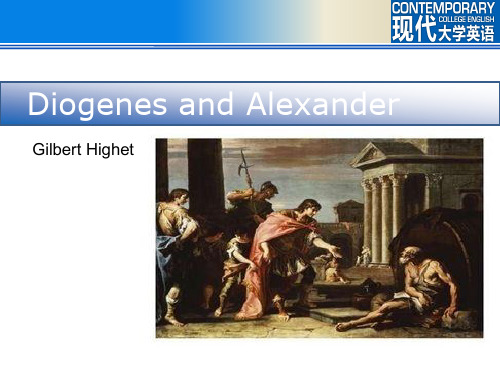

Diogenes and Alexander

Gilbert Highet

Diogenes and Alexander Unit 4

Diogenes

Background

Alexander

Background

➢ Diogenes (412 – 324 BC): Greek cynic philosopher ➢ lived in a tub ➢ nicknamed “the dog” ➢ emphasized self-sufficiency and need for natural, uninhibited

Background

➢ Plato (429 – 347 BC): Athenian philosopher, a disciple of Socrates and the teacher of Aristotle.

Diogenes and Alexander第奥真尼斯和亚历山大大帝(高教材料)

13

应用2

Aristotle , Alexander III

❖ 亚历山大大帝是亚里士多 德的弟子,他是一位智慧 非凡的人

❖ 亚历山大童年早期就显示 了在音乐和马术上的才华, 珍爱荷马诗歌,亚里士多 德给予他完整的口才和文 学训练,并且激发了他对 科学、医学和哲学的兴趣。

14

应用2

人物评论

❖ 亚历山大是历史上最富有戏剧性的人物,有关他生涯的确凿事

高“呼犬A“儒像 主狗 义一 ”样 (BC活y着n”ici。sCm人)们。把他他的们哲的学哲思学想叫为做

古希腊崇尚简朴的生活理想奠定了基础。

7

应用2

犬儒主义

❖ 犬儒主义是一种带着厌倦情绪的负面态度,对于他人行为 的动机与诚信都采取一种不信任的态度。

❖ 源于古希腊犬儒学派学者主张的哲学思潮。该派别由苏格

❖ 其主要教条是,人要摆脱世俗的利益而追求唯一值得拥有

的善.

Text in here

Text in here

❖ 倡导尽量少的改变自然,与自然和谐共处。不因人的过多 需求去改造自然,追求清静无为,小国寡民。

8

应用2

犬儒主义的发展

❖随着犬儒理念的流行,犬儒主义的内涵发生了微 妙的根本变化。早期的犬儒主义者是根据自身的 道德原则去蔑视世俗的观念;后期的犬儒主义者 依旧蔑视世俗的观念,但是却丧失了赖为准绳的 道德原则

Alexander III

❖ 亚历山大大帝(公元前 356-前323年),古 代马其顿国王,亚历山 大帝国皇帝,世界古代 史上著名的军事家和政 治家。

❖ 古代马其顿国王腓力二 世之子。

❖ 亚里士多德的学生之一。

11

应用2

亚历山大大帝

20岁继承王位 13岁随父出征

Unit_4_Diogenes_and_Alexander

For understandable reasons, Diogenes has never had a large following. However, Diogenes has never been forgotten either, especially in modern times.

…….and washed them down with a few handfuls of water scooped from the spring. (para.1) A few handfuls of -ful here is used as a noun suffix. e.g. a few mouthfuls of / a spoonful of honey/a glassful of beer.

Unit 4 Diogenes and Alexander

Author: Gilbert Highet

Gilbert Highet (1906-1978) Scholarly and critical writers Born in Scotland and became American citizen Educated in Scotland and Oxford

II. Diogenes' meeting with Alexander(paras.11-17)

A. Alexander's presence in Corinth.(para.11) B. His motivation for visiting Diogenes.(paras.14-17) C. His brief exchange with Diogenes(paras.14-17)

Diogenes and Alexander基础英语

• • •

• • • • • • •

• • • • •

Reign:336–323 BC Full name: Alexander III of Macedon Titles: King of Macedon Hegemon of the Hellenic League Shahanshah of Persia Pharaoh of Egypt Lord of Asia Born: 20 or 21 July 356 BC Birthplace: Pella, Macedon Died:10 or 11 June 323 BC (aged 32) Place of death: Babylon Predecessor: Philip II of Macedon Successor:Alexander IV of Macedon Philip III of Macedon Wives: Roxana of Bactria Stateira II of Persia Parysatis II of Persia Offspring: Alexander IV of Macedon Dynasty: Argead dynasty Father: Philip II of Macedon Mother: Olympias of Epirus Religious beliefs: Greek polytheism

Diogenes and Alexander

Who is Diogenes

A Greek philosopher One of the founders of Cynic philosophy. Also known as Diogenes of Sinope, Diogenes the Cynic, or Diogenes the Dog. He was born in Sinope(modernday Sinop斯诺普, Turkey), an Ionian爱奥尼亚colony on the Black Sea, in 412 BC or 404 BC and died at Corinth科林斯 in 323 BC.

Diogenes and Alexander第奥真尼斯和亚历山大大帝备课讲稿

❖ 击 亚败 历的 山敌 大15人对% 经他常的5给同0%予代无人微有不着至极其的广关泛怀的、影爱35响护%,和从慰长藉7%远。的观点来看,亚 历山大远征客观上促进了东西方的文化交流。在希腊文化时代(亚历山

食住行方面的习俗等一切世俗。对身外之物一无所求,对

苦乐无T动ex于t in衷he。re

Text in hee

Text in here

Text in here

❖ 其主要教条是,人要摆脱世俗的利益而追求唯一值得拥有

的善.

Text in here

Text in here

❖ 倡导尽量少的改变自然,与自然和谐共处。不因人的过多 需求去改造自然,追求清静无为,小国寡民。

❖ 古代马其顿国王腓力二 世之子。

❖ 亚里士多德的学生之一。

亚历山大大帝

20岁继承王位 13岁随父出征

建立帝国 建立帝国

33岁去世 33岁去世

著名的军事家和政治家

❖ 他足智多谋,智勇双全,在11年的奋战中,他从 未打过一次败仗。

❖ 在担任马其顿国王的短短13年中,以其雄才大略。 东征西讨,先是确立了在全希腊的统治地位,后 又灭亡了波斯帝国。在横跨欧、亚的辽阔土地上, 建立起了亚历山大帝国。创下了前无古人的辉煌 业绩,促进了东西方文化的交流和经济的发展, 对人类社会的进展产生了重大的影响。

高“呼犬A“儒像 主狗 义一 ”样 (BC活y着n”ici。sCm人)们。把他他的们哲的学哲思学想叫为做

古希腊崇尚简朴的生活理想奠定了基础。

全版DiogenesandAlexander第奥真尼斯和亚历山大大帝报告.ppt

Text in here

beggar

Text in here

Text in here philoso pher

整理

Diogenes

Text in here

mission ary

CEO

Text in here

Text in here

Tet in here

Text inhere Text in here

❖ He was born in Sinope(modern-day Sinope,Turkey)and died at Corinth科林斯(希腊古 城)。

❖ His father was a banker.

整理

General Introduction

❖It is said that Diogenes aided his father in the banking business,and he became embroiled in a scandal involving the adulteration or defacement of the currency,and Diogenes was exiled from the city.From then,he lived in streets of Corinth , Athens ;And he became the prototype of Cynicism.

拉人底应的当Te学摒xt 生弃in 安一he提切re 西世尼俗(的A事n物ti,st包h括en宗e教s)、创礼Te立x节t。i、n本h惯e意r常e是的指衣

食住行方面的习俗等一切世俗。对身外之物一无所求,对

苦乐无T动ex于t in衷he。re

Text in hee

DiogenesandAlexander奥真尼斯和亚历山大大帝PPT课件

• 犬儒一词的演变证明,从愤世嫉俗到玩世不恭,其间只有一步之差。

第8页/共18页

Alexander the Great

古代马其顿国王,亚历山大帝国皇帝 世界古代史上著名的军事家和政治家 亚里士多德的学生之一 人物死因及人物评论

第9页/共18页

Alexander III

亚历山大大帝(公元 前356-前323年) ,古代马其顿国王, 亚历山大帝国皇帝, 世界古代史上著名的 军事家和政治家。

give wealth to others, hope to herself, she will bring me endless wealth

第16页/共18页

Thank You!

L/O/G/O

第17页/共18页

感谢您的观看!

第18页/共18页

大灾难来临的前兆,此时有一人却说:“女神殿的焚毁日,已有一个男孩在同日诞生,此儿以后 将要灭亡全亚洲。”

• 他还是亚里士多德的弟子,是一位智慧非凡的人,一般认为,亚历山大是位颇受人喜爱 的人物。他认识到了非希腊人不一定是野蛮人,这确实表现了他远比当时的大多数希腊

思想家更具有远见卓识。他对被击败ቤተ መጻሕፍቲ ባይዱ敌人经常给予无微不至的关怀、爱护和慰藉。

A

B

C

第6页/共18页

犬儒主义

• 犬儒主义是一种带着厌倦情绪的负面态度,对于他人行为的动机与诚信都 采取一种不信任的态度。

【正式版】DiogenesandAlexander第奥真尼斯和亚历山大大帝PPT资料

优选DiogenesandAlexander第奥真 尼斯和亚历山大大帝ppt

1

戴奥真尼斯

2

犬儒主义

3

亚历山大大帝

4 评论,死因,相关名言

Diogenes 戴奥真尼斯/第欧根尼

❖ Diogenes(412-324 BC) was a famous

本意是指人应当摒弃一切世俗的事物,包括宗教、礼节、惯常的衣食住行方面的习俗等一切世俗。

❖ 其主要教条是,人要摆脱世俗的利益而追求唯一值得拥有 古古代代马 马其其顿顿国国王王腓,力亚二历世山之大T子帝e。国x皇t i帝n here

Text in here

亚历山大是历史上最富有戏剧性的人物,有关他生涯的确凿事实十分富有戏剧性,有关他的名字就有许多种传说。

Text in here

beggar

Text in here

Text in here

philoso pher

Diogenes

Text in here

mission ary

CEO

Text in here

Text in here

Tet in here

Text inhere Text in here

主要思想

Text in here

Greek philosopher , 其主要教条是,人要摆脱世俗的利益而追求唯一值得拥有的善.

他认为除了自然的需要必须满足外,其他的任何东西,包括社会生活和文化生活,都是不自然的、无足轻重的。

one of the founder 东征西讨,先是确立了在全希腊的统治地位,后又灭亡了波斯帝国。

高“呼犬A“儒像 主狗 义一 ”样 (BC活y着n”ici。sCm人)们。把他他的们哲的学哲思学想叫为做

Diogenes-and-Alexander-翻译

Lesson 18 ——Diogenes and Alesander他躺在光溜溜的地上,赤着脚,胡子拉茬的,半裸着身子,模样活像个乞丐或疯子。

可他就是他,而不是别的什么人。

大清早,他随着初升的太阳睁开双眼,搔了搔痒,便像狗一样在路边解手。

他在公共喷泉边抹了把脸,向路人讨了一块面包和几颗橄榄,然后蹲在地上大嚼起来,又掬起几捧泉水送入肚中。

他没工作在身,也无家可归,是一个逍遥自在的人。

街市上熙熙攘攘,到处是顾客、商人、奴隶、异邦人,这时他也会在其中转悠一二个钟头。

人人都认识他,或者都听说过他。

他们会问他一些尖刻的问题,而他也尖刻地回答。

有时他们丢给他一些食物,他很有节制地道一声谢;有时他们恶作剧地扔给他卵石子,他破口大骂,毫不客气地回敬。

他们拿不准他是不是疯了。

他却认定他们疯了,只是他们的疯各有各的不同;他们令他感到好笑。

此刻他正走回家去。

他没有房子,甚至连一个茅庐都没有。

他认为人们为生活煞费苦心,过于讲究奢华。

房子有什么用处?人不需要隐私;自然的行为并不可耻;我们做着同样的事情,没什么必要把它们隐藏起来。

人实在不需要床榻和椅子等诸如此类的家具,动物睡在地上也过着健康的生活。

既然大自然没有给我们穿上适当的东西。

那我们惟一需要的是一件御寒的衣服,某种躲避风雨的遮蔽。

所以他拥有一张毯子——白天披在身,晚上盖在身上——他睡在一个桶里,他的名字叫狄奥根尼。

人们称他为“狗”,把他的哲学叫做“犬儒哲学”。

他一生大部分时光都在希腊的克林斯城邦度过,那是一个富裕、懒散、腐败的城市,他挖苦嘲讽那里的人们,偶尔也把矛头转向他们当中的某个人。

他的住所不是木材做成的,而是泥土做的贮物桶。

这是一个破桶,显然是人们弃之不用的。

住这样的地方他并不是第一个,但他确实是第一个自愿这么做的人,这出乎众人的想法。

狄奥根尼不是疯子,他是一个哲学家,通过戏剧、诗歌和散文的创作来阐述他的学说;他向那些愿意倾听的人传道;他拥有一批崇拜他的门徒。

Diogenes and Alexander 戴奥吉尼斯和亚历山大

Only twenty, Alexander was far older and wiser than his years. Like all Macedonians he loved drinking, but he could usually handle it; and toward women he was nobly restrained and chivalrous. Like all Macedonians he loved fighting; he was a magnificent commander, but he was not merely a military automaton. He could think. At thirteen he had become a pupil of the greatest mind in Greece, Aristotle. No exact record of his schooling survives. It is clear, though, that Aristotle took the passionate, half-barbarous boy and gave him the best of Greek culture. He taught Alexander poetry; the young prince slept with the Iliad under his pillow and longed to emulate Achilles, who brought the mighty power of Asia to ruin. He taught him philosophy, in particular the shapes and uses of political power: a few years later Alexander was to create a supranational empire that was not merely a power system but a vehicle for the exchange of Greek and Middle Eastern cultures.Aristotle taught him the principles of scientific research: during his invasion of the Persian domains Alexander took with him a large corps of scientists, and shipped hundreds of zoological specimens back to Greece for study. Indeed, it was from Aristotle that Alexander learned to seek out everything strange which might be instructive. Jugglers and stunt artists and virtuosos of the absurd he dismissed with a shrug; but on reaching India he was to spend hours discussing the problems of life and death with naked Hindu mystics, and later to see one demonstrate Yoga self-command by burning himself impassively to death.Now, Alexander was in Corinth to take command of the League of Greek States which, after conquering them, his father Philip created as a disguise for the New Macedonian Order. He was welcomed and honored and flattered. He was the man of the hour, of the century; he was unanimously appointed commander-in-chief of a new expedition against old, rich, corrupt Asia. Nearly everyone crowded to Corinth in order to congratulate him, to seek employment with him, even simply to see him:。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Diogenes and Alexander Lying on the bare earth, shoeless, bearded, half-naked, he looked like a beggar or a lunatic. He was one, but not the other. He had opened his eyes with the sun at dawn, scratched, done his business like a dog at the roadside, washed at the public fountain, begged a piece of breakfast bread and a few olives, eaten them squatting on the ground, and washed them down with a few handfuls of water scooped from the spring. (Long ago he had owned a rough wooden cup, but he threw it away when he saw a boy drinking out of his hollowed hands.) Having no work to go to and no family to provide for, he was free. As the market place filled up with shoppers and merchants and slaves and foreigners, he had strolled through it for an hour or two. Everybody knew him, or knew of him. They would throw sharp questions at him and get sharper answers. Sometimes they threw bits of food, and got scant thanks; sometimes a mischievous pebble, and got a shower of stones and abuse. They were not quite sure whether he was mad or not. He knew they were mad, each in a different way; they amused him. Now he was back at his home. It was not a house, not even a squatter's hut. He thought everybody lived far too elaborately, expensively, anxiously. What good is a house? No one needs privacy; natural acts are not shameful; we all do the same things, and need not hide them. No one needs beds and chairs and such furniture: the animals live healthy lives and sleep on the ground. All we require, since nature did not dress us properly, is one garment to keep us warm, and some shelter from rain and wind. So he had one blanket — to dress him in the daytime and cover him at night — and he slept in a cask. His name was Diogenes. He was the founder of the creed called Cynicism (doggishness); he spent much of his life in the rich, lazy, corrupt Greek city of Corinth, mocking and satirizing its people, and occasionally converting one of them. His home was not a barrel made of wood; too expensive. It was a storage jar made of earthenware, no doubt discarded because a break had made it useless. He was not the first to inhabit such a thing. But he was the first who ever did so by choice, out of principle. Diogenes was not a lunatic. He was a philosopher who wrote plays and poems and essays expounding his doctrine; he talked to those who cared to listen; he had pupils who admired him. But he taught chiefly by example. All should live naturally, he said, for what is natural is normal and cannot possibly be evil or shameful. Live without conventions, which are artificial and false; escape complexities and extravagances: only so can you live a free life. The rich man believes he possesses his big house with its many rooms and its elaborate furniture, his expensive clothes, his horses and servants and his bank accounts. He does not. He depends on them, he worries about them, he spends most of his life's energy looking after them; the thought of losing them makes him sick with anxiety. They possess him. He is their slave. In order to procure a quantity of false, perishable goods he has sold the only true, lasting good, his own independence. There have been many men who grew tired of human society with its complications, and went away to live simply — in a small farm, in a quiet village, or in a hermit's cave. Not so Diogenes. He was a missionary. His life's aim was clear to him: it was "to restamp the currency": to take the clean metal of human life, to erase the old false conventional markings, and to imprint it with its true values. The other great philosophers of the fourth century B.C., such as Plato and Aristotle, taught mainly their own private pupils. But for Diogenes, laboratory and specimens and lecture halls and pupils were all to be found in a crowd of ordinary people. Therefore, he chose to live in Athens or Corinth, where travelers from all over the Mediterranean world constantly came and went. And, by design, he publicly behaved in such ways as to show people what real life was. He thought most people were only half-alive, most men only half-men. At bright noonday he walked through the market place carrying a lighted lamp and inspecting the face of everyone he met. They asked him why. Diogenes answered "I'm trying to find a man." To a gentleman whose servant was putting on his shoes for him, Diogenes said, "You won't be really happy until he wipes your nose for you: that will come after you lose the use of your hands." Once there was a war scare so serious that it stirred even the lazy, profit-happy Corinthians. They began to drill, clean their weapons, and rebuild their neglected fortifications. Diogenes took his old cask and began to roll it up and down. "When you are all so busy," he said, "I feel I ought to do something!" And so he lived — like a dog, some said, because he cared nothing for the conventions of society, and because he showed his teeth and barked at those he disliked. Now he was lying in the sunlight, contented and happy, happier (he himself used to boast) than the Shah of Persia. Although he knew he was going to have an important visitor, he would not move. The little square began to fill with people — page boys, soldiers, secretaries, officers, diplomats, they all gradually formed a circle around Diogenes. He looked them over, as a sober man looks at a crowd of tottering drunks, and shook his head. He knew who they were. They were the servants of Alexander, the conqueror of Greece, the Macedonian king, who was visiting his new realm. Only twenty, Alexander was far older and wiser than his years. Like all Macedonians he loved drinking, but he could usually handle it; and toward women, he was nobly restrained and chivalrous. Like all Macedonians he loved fighting; he was a magnificent commander, but he was not merely a military automaton. He could think. At 13 he had become a pupil of the greatest mind in Greece, Aristotle, who gave him the best of Greek culture. He taught Alexander poetry: the young prince slept with the Iliad under his pillow and longed to emulate Achilles, who brought the mighty power of Asia to ruin. He taught him philosophy, in particular the shapes and uses of political power. And he taught him the principles of scientific research: during his invasion of Persia, Alexander took with him a large corps of scientists, and shipped hundreds of zoological specimens back to Greece for study. Indeed, it was from Aristotle that Alexander learned to seek out everything strange which might be instructive. Now Alexander was in Corinth to take command of the League of Greek States, which his father Philip had created. He was welcomed and honored and flattered. He was