第一章 翻译研究名与实

21

内容提要

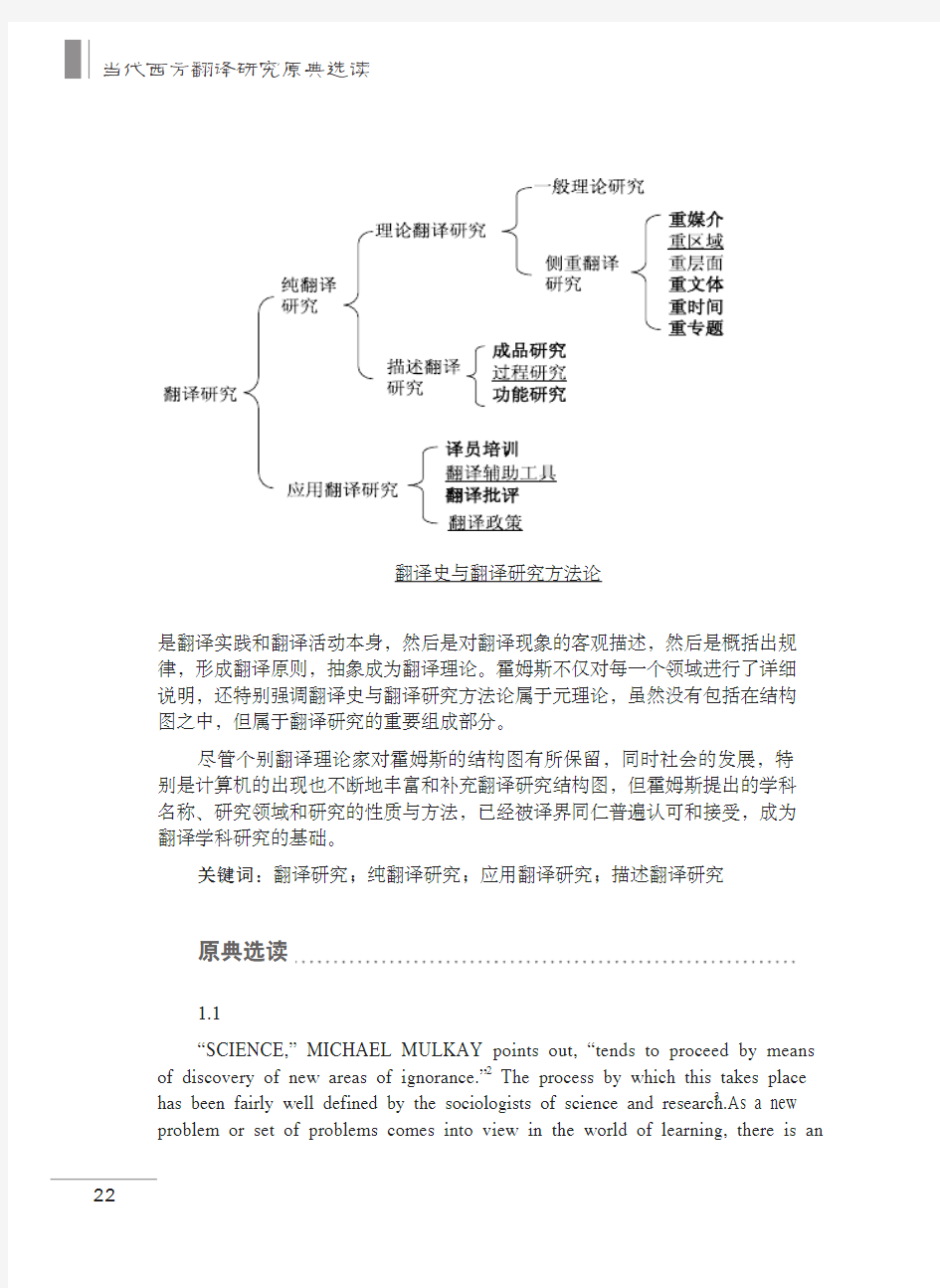

霍姆斯的这篇文章一直被翻译研究界视为具有划时代的重要意义。两千多年以来,人们对翻译的方方面面进行了不懈的探讨,但对翻译研究作为一门学科的研究对象、研究范围以及研究方法却不甚明了,或莫衷一是。首先,霍姆斯提出将翻译研究(Translation Studies )作为学科的称谓,并强调翻译研究是一门经验学科,研究对象是翻译活动(过程)和翻译作品;翻译研究的功能是不仅要探讨如何翻译,同时还要描述翻译现象和行为,解释、甚至预测未来的翻译。更重要的是,霍姆斯第一次详尽地描绘出翻译研究的结构图(见下页)。

对照这个图可以发现,翻译研究的领域比我们传统想像的要宽阔得多。黑体是我国研究较为深入的领域,而下划线表示还有待加强。此外,还有一些未开垦的处女地。这个结构图同时表示了翻译研究自下而上的发展路径:首先

作者简介

詹姆斯·霍姆斯(James Holmes ),著名的翻译理论家。生于美国艾奥瓦中部,曾就读于威廉·潘学院和布朗大学;1949年作为富布赖特交换教师到荷兰国际学院任教,1950年移居阿姆斯特丹,以自由编辑和诗歌翻译为业。1956年以非本族语使用者身份荣获翻译大奖,1964年任阿姆斯特丹大学翻译研究高级讲师。发表多篇有关翻译的论文,《翻译研究名与实》(The Name and Nature of Translation Studies, 1972)第一次比较完整系统地界定了翻译研究作为一个跨学科的研究领域,成为当代翻译研究划时代的重要文献,得到国际译界的普遍认可。本篇选自James Holmes 的Translated! Papers on Literary and Translation Studies ,由Rodopi 出版社于1994年出版。

第一章

翻译研究名与实

The Name and Nature of Translation Studies 1 James S. Holmes

当代西方翻译研究原典选读

22

翻译史与翻译研究方法论

是翻译实践和翻译活动本身,然后是对翻译现象的客观描述,然后是概括出规律,形成翻译原则,抽象成为翻译理论。霍姆斯不仅对每一个领域进行了详细说明,还特别强调翻译史与翻译研究方法论属于元理论,虽然没有包括在结构图之中,但属于翻译研究的重要组成部分。

尽管个别翻译理论家对霍姆斯的结构图有所保留,同时社会的发展,特别是计算机的出现也不断地丰富和补充翻译研究结构图,但霍姆斯提出的学科名称、研究领域和研究的性质与方法,已经被译界同仁普遍认可和接受,成为翻译学科研究的基础。

关键词:翻译研究;纯翻译研究;应用翻译研究;描述翻译研究

原典选读

1.1

“SCIENCE,” MICHAEL MULKAY points out, “tends to proceed by means of discovery of new areas of ignorance.” 2 The process by which this takes place has been fairly well defined by the sociologists of science and research.3 As a new problem or set of problems comes into view in the world of learning, there is an

第一章翻译研究名与实influx of researchers from adjacent areas, bringing with them the paradigms and models that have proved fruitful in their own fields. These paradigms and models

are then brought to bear on the new problem, with one of two results. In some situations the problem proves amenable to explicitation, analysis, explication, and

at least partial solution within the bounds of one of the paradigms or models, and in

that case it is annexed as a legitimate branch of an established field of study. In other situations the paradigms or models fail to produce sufficient results, and researchers become aware that new methods are needed to approach the problem.

In the second type of situation, the result is a tension between researchers investigating the new problem and colleagues in their former fields, and this tension

can gradually lead to the establishment of new channels of communication and the development of what has been called a new disciplinary utopia, that is, a new sense

of a shared interest in a common set of problems, approaches, and objectives on

the part of a new grouping of researchers. As W. O. Hagstrom has indicated, these

two steps, the establishment of communication channels and the development of

a disciplinary utopia, “make it possible for scientists to identify with the emerging discipline and to claim legitimacy for their point of view when appealing to university bodies or groups in the larger society.” 4

1.2

Though there are no doubt a few scholars who would object, particularly among the linguists, it would seem to me clear that in regard to the complex of problems clustered round the phenomenon of translating and translations,5 the second situation now applies. After centuries of incidental and desultory attention from a scattering of authors, philologians, and literary scholars, plus here and there

a theologian or an idiosyncratic linguist, the subject of translation has enjoyed a marked and constant increase in interest on the part of scholars in recent years, with

the Second World War as a kind of turning point. As this interest has solidified and expanded, more and more scholars have moved into the field, particularly from the adjacent fields of linguistics, linguistic philosophy, and literary studies, but also from such seemingly more remote disciplines as information theory, logic, and mathematics, each of them carrying with him paradigms, quasi-paradigms, models,

and methodologies that he felt could be brought to bear on this new problem.

At first glance, the resulting situation today would appear to be one of great confusion, with no consensus regarding the types of models to be tested, the kinds

of methods to be applied, the varieties of terminology to be used. More than that,

2

当代西方翻译研究原典选读

2 there is not even likemindedness about the contours of the field, the problem set, the discipline as such. Indeed, scholars are not so much as agreed on the very name for the new field.

Nevertheless, beneath the superficial level, there are a number of indications that for the field of research focusing on the problems of translating and translations Hagstrom’s disciplinary utopia is taking shape. If this is a salutary development (and I believe that it is), it follows that it is worth our while to further the development by consciously turning our attention to matters that are serving to impede it.

1.3

One of these impediments is the lack of appropriate channels of communication. For scholars and researchers in the field, the channels that do exist still tend to run via the older disciplines (with their attendant norms in regard to models, methods, and terminology), so that papers on the subject of translation are dispersed over periodicals in a wide variety of scholarly fields and journals for practising translators. It is clear that there is a need for other communication channels, cutting across the traditional disciplines to reach all scholars working in the field, from whatever background.

2.1

But I should like to focus our attention on two other impediments to the development of a disciplinary Utopia. The first of these, the lesser of the two in importance, is the seemingly trivial matter of the name for this field of research. It would not be wise to continue referring to the discipline by its subject matter as has been done at this conference, for the map, as the General Semanticists constantly remind us, is not the territory, and failure to distinguish the two can only further confusion.

Through the years, diverse terms have been used in writings dealing with translating and translations, and one can find references in English to “the art” or “the craft” of translation, but also to the “principles” of translation, the “fundamentals” or the “philosophy”. Similar terms recur in French and German. In some cases the choice of term reflects the attitude, point of approach, or background of the writer; in others it has been determined by the fashion of the moment in scholarly terminology.

第一章翻译研究名与实There have been a few attempts to create more “learned” terms, most of them with the highly active disciplinary suffix -ology. Roger Goffin, for instance,

has suggested the designation “translatology” in English, and either its cognate or traductologie in French.6 But since the -ology suffix derives from Greek, purists reject a contamination of this kind, all the more so when the other element is

not even from Classical Latin, but from Late Latin in the case of translatio or Renaissance French in that of traduction. Yet Greek alone offers no way out, for “metaphorology”, “metaphraseology”, or “metaphrastics” would hardly be of aid to

us in making our subject clear even to university bodies, let alone to other “groups

in the larger society.”7 Such other terms as “translatistics” or “translistics”, both of which have been suggested, would be more readily understood, but hardly more acceptable.

2.2.1

Two further, less classically constructed terms have come to the fore in recent years. One of these began its life in a longer form, “the theory of translating” or “the theory of translation” (and its corresponding forms: “Theorie des übersetzens”,

“théorie de la traduction”). In English (and in German) it has since gone the way

of many such terms, and is now usually compressed into “translation theory”

(übersetzungstheorie). It has been a productive designation, and can be even more

so in future, but only if it is restricted to its proper meaning. For, as I hope to make clear in the course of this paper, there is much valuable study and research being done in the discipline, and a need for much more to be done, that does not, strictly speaking, fall within the scope of theory formation.

2.2.2

The second term is one that has, to all intents and purposes, won the

field in German as a designation for the entire discipline.8 This is the term

übersetzungswissenschaft, constructed to form a parallel to Sprachwissenschaft, Literaturwissenschaft, and many other Wissenschaften. In French, the comparable designation, “science de la traduction”, has also gained ground, as have parallel terms in various other languages.

One of the first to use a parallel-sounding term in English was Eugene Nida, who in 1964 chose to entitle his theoretical handbook Towards a Science

of Translating.9 It should be noted, though, that Nida did not intend the phrase

as a name for the entire field of study, but only for one aspect of the process of translating as such.10 Others, most of them not native speakers of English, have been

2

当代西方翻译研究原典选读

2 more bold, advocating the term “science of translation” (or “translation science”) as the appropriate designation for this emerging discipline as a whole. Two years ago this recurrent suggestion was followed by something like canonization of the term when Bausch, Klegraf, and Wilss took the decision to make it the main title to their analytical bibliography of the entire field.11

It was a decision that I, for one, regret. It is not that I object to the term übersetzungswissenschaft, for there are few if any valid arguments against that designation for the subject in German. The problem is not that the discipline is not a Wissenschaft, but that not all Wissenschaften can properly be called sciences. Just as no one today would take issue with the terms Sprachwissenschaft and Literaturwissenschaft, while more than a few would question whether linguistics has yet reached a stage of precision, formalization, and paradigm formation such that it can properly be described as a science, and while practically everyone would agree that literary studies are not, and in the foreseeable future will not be, a science in any true sense of the English word, in the same way I question whether we can with any justification use a designation for the study of translating and translations that places it in the company of mathematics, physics, and chemistry, or even biology, rather than that of sociology, history, and philosophy – or for that matter of literary studies.

2.3

There is, however, another term that is active in English in the naming of new disciplines. This is the word “studies”. Indeed, for disciplines that within the old distinction of the universities tend to fall under the humanities or arts rather than the sciences as fields of learning, the word would seem to be almost as active in English as the word Wissenschaft in German. One need only think of Russian studies, American studies, Commonwealth studies, population studies, communication studies. True, the word raises a few new complications, among them the fact that it is difficult to derive an adjectival form. Nevertheless, the designation “translation studies” would seem to be the most appropriate of all those available in English, and its adoption as the standard term for the discipline as a whole would remove a fair amount of confusion and misunderstanding. I shall set the example by making use of it in the rest of this paper. A greater impediment than the lack of a generally accepted name in the way of the development of translation studies is the lack of any general consensus as to the scope and structure of the discipline. What constitutes the field of translation studies? A few would say it coincides with comparative (or contrastive) terminological and lexicographical studies; several look upon it as practically

第一章翻译研究名与实identical with comparative or contrastive linguistics; many would consider it largely synonymous with translation theory. But surely it is different, if not always distinct, from the first two of these, and more than the third. As is usually to be found in the case of emerging disciplines, there has as yet been little meta-reflection on the nature

of translation studies as such—at least that has made its way into print and to my attention. One of the few cases that I have found is that of Werner Koller, who has given the following delineation of the subject: “übersetzungswissenschaft ist zu verstehen als Zusammenfassung und überbegriff für alle Forschungsbemühungen,

die yon den Ph?nomenen ‘übersetzen’ und ‘übersetzung’ ausgehen oder auf diese

Ph?nomene zielen.” (Translation studies is to be understood as a collective and inclusive designation for all research activities taking the phenomena of translating

and translation as their basis or focus. 12)

3.1

From this delineation it follows that translation studies is, as no one I suppose would deny, an empirical discipline. Such disciplines, it has often been pointed out, have two major objectives, which Carl G. Hempel has phrased as “to describe particular phenomena in the world of our experience and to establish general principles by means of which they can be explained and predicted.”13 As a field of pure research—that is to say, research pursued for its own sake, quite apart from any direct practical application outside its own terrain—translation studies thus has two main objectives: (1) to describe the phenomena of translating and translation(s) as

they manifest themselves in the world of our experience, and (2) to establish general principles by means of which these phenomena can be explained and predicted. The

two branches of pure translation studies concerning themselves with these objectives

can be designated descriptive translation studies (DTS) or translation description (TD) and theoretical translation studies (ThTS) or translation theory (TTh).

3.1.1

Of these two, it is perhaps appropriate to give first consideration to descriptive translation studies, as the branch of the discipline which constantly maintains the closest contact with the empirical phenomena under study. There would seem to be three major kinds of research in DTS, which may be distinguished by their focus as product-oriented, function-oriented, and process-oriented.

2

当代西方翻译研究原典选读

2

3.1.1.1

Product-oriented DTS, that area of research which describes existing translations, has traditionally been an important area of academic research in translation studies. The starting point for this type of study is the description of individual translations, or text-focused translation description. A second phase is that of comparative translation description, in which comparative analyses are made of various translations of the same text, either in a single language or in various languages. Such individual and comparative descriptions provide the materials for surveys of larger corpuses of translations, for instance, those made within a specific period, language, and/or text or discourse type. In practice the corpus has usually been restricted in all three ways: seventeenth-century literary translations into French, or medieval English Bible translations. But such descriptive surveys can also be larger in scope, diachronic as well as (approximately) synchronic, and one of the eventual goals of product-oriented DTS might possibly be a general history of translation – however ambitious such a goal may sound at this time.

3.1.1.2

Function-oriented DTS is not interested in the description of translations in themselves, but in the description of their function in the recipient socio-cultural situation: it is a study of contexts rather than texts. Pursuing such questions as which texts were (and, often as important, were not) translated at a certain time in a certain place, and what influences were exerted in consequence, this area of research is one that has attracted less concentrated attention than the area just mentioned, though it is often introduced as a kind of a sub-theme or counter-theme in histories of translations and in literary histories. Greater emphasis on it could lead to the development of a field of translation sociology (or—less felicitous but more accurate, since it is a legitimate area of translation studies as well as of sociology—socio-translation studies).

3.1.1.3

Process-oriented DTS concerns itself with the process or act of translation itself. The problem of what exactly takes place in the “little black box” of the translator’s “mind” as he creates a new, more or less matching text in another language has been the subject of much speculation on the part of translation’s theorists, but there has been very little attempt at systematic investigation of this process under laboratory conditions. Admittedly, the process is an unusually

第一章翻译研究名与实complex one, one which, if I. A. Richards is correct, “may very probably be the most complex type of event yet produced in the evolution of the cosmos.’’14 But psychologists have developed and are developing highly sophisticated methods for analysing and describing other complex mental processes, and it is to be hoped that

in future this problem, too, will be given closer attention, leading to an area of study

that might be called translation psychology or psycho-translation studies.

3.1.2

The other main branch of pure translation studies, theoretical translation studies or translation theory, is, as its name implies, not interested in describing existing translations, observed translation functions, or experimentally determined translating processes, but in using the results of descriptive translation studies, in combination with the information available from related fields and disciplines, to evolve principles, theories, and models which will serve to explain and predict what translating and translations are and will be.

3.1.2.1

The ultimate goal of the translation theorist in the broad sense must undoubtedly be to develop a full, inclusive theory accommodating so many elements

that it can serve to explain and predict all phenomena falling within the terrain of translating and translation, to the exclusion of all phenomena falling outside it. It hardly needs to be pointed out that a general translation theor y in such a true sense

of the term, if indeed it is achievable, will necessarily be highly formalized and, however the scholar may strive after economy, also highly complex.

Most of the theories that have been produced to date are in reality little more

than prolegomena to such a general translation theory. A good share of them, in fact,

are not actually theories at all, in any scholarly sense of the term, but an array of axioms, postulates, and hypotheses that are so formulated as to be both too inclusive (covering also non-translatory acts and non-translations) and too exclusive (shutting

out some translatory acts and some works generally recognized as translations).

3.1.2.2

Others, though they too may bear the designation of “general” translation theories (frequently preceded by the scholar’s protectively cautious “towards”), are

in fact not general theories, but partial or specific in their scope, dealing with only

one or a few of the various aspects of translation theory as a whole. It is in this area

2

当代西方翻译研究原典选读

0of partial theories that the most significant advances have been made in recent years, and in fact it will probably be necessary for a great deal of further research to be conducted in them before we can even begin to think about arriving at a true general theory in the sense I have just outlined. Partial translation theories are specified in a number of ways. I would suggest, though, that they can be grouped together into six main kinds.

3.1.2.2.1

First of all, there are translation theories that I have called, with a somewhat unorthodox extension of the term, medium-restricted translation theories, according to the medium that is used. Medium-restricted theories can be further subdivided into theories of translation as performed by humans (human translation), as performed by computers (machine translation), and as performed by the two in conjunction (mixed or machine-aided translation). Human translation breaks down into (and restricted theories or “theories” have been developed for) oral translation or interpreting (with the further distinction between consecutive and simultaneous) and written translation. Numerous examples of valuable research into machine and machine-aided translation are no doubt familiar to us all, and perhaps also several into oral human translation. That examples of medium-restricted theories of written translation do not come to mind so easily is largely owing to the fact that their authors have the tendency to present them in the guise of unmarked or general theories.

3.1.2.2.2

Second, there are theories that are area-restricted. Area-restricted theories can be of two closely related kinds; restricted as to the languages involved or, which is usually not quite the same, and occasionally hardly at all, as to the cultures involved. In both cases, language restriction and culture restriction, the degree of actual limitation can vary. Theories are feasible for translation between, say, French and German (language-pair restricted theories) as opposed to translation within Slavic languages (language-group restricted theories) or from Romance languages to Germanic languages (language-group pair restricted theories). Similarly, theories might at least hypothetically be developed for translation within Swiss culture (one-culture restricted), or for translation between Swiss and Belgian cultures (cultural-pair restricted), as opposed to translation within Western Europe (cultural-group restricted) or between languages reflecting a pre-technological culture and the languages of contemporary Western culture (cultural-group pair restricted).

第一章翻译研究名与实Language-restricted theories have close affinities with the work being done in comparative linguistics and stylistics (though it must always be remembered that

a language-pair translation grammar must be a different thing from a contrastive grammar developed for the purpose of language acquisition). In the field of culture-restricted theories there has been little detailed research, though culture restrictions, by being confused with language restrictions, sometimes get introduced

into language-restricted theories, where they are out of place in all but those rare cases where culture and language boundaries coincide in both the source and target situations. It is moreover no doubt true that some aspects of theories that are presented as general in reality pertain only to the Western cultural area.

3.1.2.2.3

Third, there are rank-restricted theories, that is to say, theories that deal

with discourses or texts as wholes, but concern themselves with lower linguistic ranks or levels. Traditionally, a great deal of writing on translation was concerned almost entirely with the rank of the word, and the word and the word group are

still the ranks at which much terminologically-oriented thinking about scientific

and technological translation takes place. Most linguistically-oriented research, on

the other hand, has until very recently taken the sentence as its upper rank limit, largely ignoring the macro-structural aspects of entire texts as translation problems.

The clearly discernible trend away from sentential linguistics in the direction of textual linguistics will, it is to be hoped, encourage linguistically-oriented theorists

to move beyond sentence-restricted translation theories to the more complex task of developing text-rank (or “rank-free”) theories.

3.1.2.2.4

Fourth, there are text-type (or discourse-type) restricted theories, dealing with

the problem of translating specific types or genres of lingual messages. Authors

and literary scholars have long concerned themselves with the problems intrinsic to translating literary texts or specific genres of literary texts; theologians, similarly, have devoted much attention to questions of how to translate the Bible and other sacred works. In recent years some effort has been made to develop a specific theory for the translation of scientific texts. All these studies break down, however, because we still lack anything like a formal theory of message, text, or discourse types. Both Bühler’s theory of types of communication, as further developed by the Prague structuralists, and the definitions of language varieties arrived at by linguists particularly of the British school provide material for criteria in defining text types

1

当代西方翻译研究原典选读

2that would lend themselves to operationalization more aptly than the inconsistent and mutually contradictory definitions or traditional genre theories. On the other hand, the traditional theories cannot be ignored, for they continue to play a large part in creating the expectation criteria of translation readers. Also requiring study is the important question of text-type skewing or shifting in translation.

3.1.2.2.5

Fifth, there are time-restricted theories, which fall into two types: theories regarding the translation of contemporary texts, and theories having to do with the translation of texts from an older period. Again there would seem to be a tendency to present one of the theories, that having to do with contemporary texts, in the guise of a general theory; the other, the theory of what can perhaps best be called cross-temporal translation, is a matter that has led to much disagreement, particularly among literarily oriented theorists, but to few generally valid conclusions.

3.1.2.2.6

Finally, there are problem-restricted theories, theories which confine themselves to one or more specific problems within the entire area of general translation theory, problems that can range from such broad and basic questions as the limits of variance and invariance in translation or the nature of translation equivalence (or, as I should prefer to call it, translation matching) to such more specific matters as the translation of metaphors or of proper names.

3.1.2.3

It should be noted that theories can frequently be restricted in more than one way. Contrastive linguists interested in translation, for instance, will probably produce theories that are not only language-restricted but rank- and time-restricted, having to do with translations between specific pairs of contemporary temporal dialects at sentence rank. The theories of literary scholars, similarly, usually are restricted as to medium and text type, and generally also as to culture group; they normally have to do with written texts within the (extended) Western literary tradition. This does not necessarily reduce the worth of such partial theories, for even a theoretical study restricted in every way—say a theory of the manner in which subordinate clauses in contemporary German novels should be translated into written English—can have implications for the more general theory towards which scholars must surely work. It would be wise, though, not to lose sight of such a truly general theory, and wiser still not to succumb to the delusion that a body of restricted

第一章翻译研究名与实theories—for instance, a complex of language-restricted theories of how to translate sentences—can be an adequate substitute for it.

3.2

After this rapid overview of the two main branches of pure research in translation studies, I should like to turn to that branch of the discipline which is, in Bacon’s words, “of use” rather than “of light”: applied translation studies. 15

3.2.1

In this discipline, as in so many others, the first thing that comes to mind when

one considers the applications that extend beyond the limits of the discipline itself is

that of teaching. Actually, the teaching of translating is of two types which need to

be carefully distinguished. In the one case, translating has been used for centuries as

a technique in foreign-language teaching and a test of foreign-language acquisition. I shall return to this type in a moment. In the second case, a more recent phenomenon, translating is taught in schools and courses to train professional translators. This second situation, that of translator training, has raised a number of questions that fairly cry for answers: questions that have to do primarily with teaching methods, testing techniques, and curriculum planning. It is obvious that the search for well-founded, reliable answers to these questions constitutes a major area (and for the

time being, at least, the major area) of research in applied translation studies.

3.2.2

A second, closely related area has to do with the needs for translation aids,

both for use in translator training and to meet the requirements of the practising translator. The needs are many and various, but fall largely into two classes: (1) lexicographical and terminological aids and (2) grammars. Both these classes of aids have traditionally been provided by scholars in other related disciplines, and it could hardly be argued that work on them should be taken over in toto as areas of applied translation studies. But lexicographical aids often fall far short of translation needs,

and contrastive grammars developed for language-acquisition purposes are not really

an adequate substitute for variety-marked translation-matching grammars. There would seem to be a need for scholars in applied translation studies to clarify and define the specific requirements in that aids of these kinds should fulfil if they are to meet the needs of practising and prospective translators, and to work together with lexicologists and contrastive linguists in developing them.

当代西方翻译研究原典选读

3.2.3

A third area of applied translation studies is that of translation policy. The task of the translation scholar in this area is to render informed advice to others in defining the place and role of translators, translating, and translations in society at large: such questions, for instance, as determining what works need to be translated in a given socio-cultural situation, what the social and economic position of the translator is and should be, or (and here I return to the point raised above) what part translating should play in the teaching and learning of foreign languages. In regard to that last policy question, since it should hardly be the task of translation studies to abet the use of translating in places where it is dysfunctional, it would seem to me that priority should be given to extensive and rigorous research to assess the efficacy of translating as a technique and testing method in language learning. The chance that it is not efficacious would appear to be so great that in this case it would seem imperative for program research to be preceded by policy research.

3.2.4

A fourth, quite different area of applied translation studies is that of translation criticism. The level of such criticism is today still frequently very low, and in many countries still quite uninfluenced by developments within the field of translation studies. Doubtless the activities of translation interpretation and evaluation will always elude the grasp of objective analysis to some extent, and so continue to reflect the intuitive, impressionist attitudes and stances of the critic. But closer contact between translation scholars and translation critics could do a great deal to reduce the intuitive element to a more acceptable level.

3.3.1

After this brief survey of the main branches of translation studies, there are two further points that I should like to make. The first is this: in what has preceded, descriptive, theoretical, and applied translation studies have been presented as three fairly distinct branches of the entire discipline, and the order of presentation might be taken to suggest that their import for one another is unidirectional, translation description supplying the basic data upon which translation theory is to be built, and the two of them providing the scholarly findings which are to be put to use in applied translation studies. In reality, of course, the relation is a dialectical one, with each of the three branches supplying materials for the other two, and making use of the findings with which they in turn provide it. Translation theory, for instance,

第一章翻译研究名与实cannot do without the solid, specific data yielded by research in descriptive and applied translation studies, while on the other hand one cannot even begin to work in

one of the other two fields without having at least an intuitive theoretical hypothesis

as one’s starting point. In view of this dialectical relationship, it follows that, though

the needs of a given moment may vary, attention to all three branches is required if

the discipline is to grow and flourish.

3.3.2

The second point is that, in each of the three branches of translation studies, there are two further dimensions that I have not mentioned, dimensions having to

do with the study, not of translating and translations, but of translation studies itself.

One of these dimensions is historical: there is a field of the history of translation theory, in which some valuable work has been done, but also one of the history

of translation description and of applied translation studies (largely a history of translation teaching and translator training) both of which are fairly well virgin territory. Likewise there is a dimension that might be called the methodological or meta-theoretical, concerning itself with problems of what methods and models can

best be used in research in the various branches of the discipline (how translation theories, for instance, can be formed for greatest validity, or what analytic methods

can best be used to achieve the most objective and meaningful descriptive results),

but also devoting its attention to such basic issues as what the discipline itself comprises.

This paper has made a few excursions into the first of these two dimensions,

but all in all it is meant to be a contribution to the second. It does not ask above all

for agreement. Translation studies has reached a stage where it is time to examine

the subject itself. Let the meta-discussion begin.

Notes

1 Written in August 1972, this paper is presented in its second pre-publication

form with only a few stylistic revisions. Despite the intervening years, most of

my remarks can, I believe, stand as they were formulated, though in one or two

places I would phrase matters somewhat differently if I were writing today. In

section 3.1.2.2.4, for instance, subsequent developments in textual linguistics,

particularly in Germany, are noteworthy. More directly relevant, the dearth of

meta-reflection on the nature of translation studies, referred to at the beginning

当代西方翻译研究原典选读

of section 3, is somewhat less striking today than in 1972, again thanks largely to German scholars. Particularly relevant is Wolfram Wilss’ as yet unpublished paper “Methodische Probleme der allgemeinen und angewandten üersetzungswissenschaft”, read at a colloquium on translation studies held in Germersheim, West Germany, 31 May 1975.

2 Michael Mulkay, “Cultural Growth in Science”, in Barry Barness (ed.), Sociology of Science: Selected Readings(Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin; Modern Sociology Readings), pp. 126-141 (abridged reprint of “Some Aspects of Cultural Growth in the Natural Sciences”, Social Research, 36 [1969], No. 1), quotation p. 136.

3 See e.g. W. O. Hagstrom, “The Differentiation of Disciplines”, in Barnes, pp. 121-125 (reprinted from Hagstrom, The Scientific Community [New York: Basic Books, 1965], pp. 222-226).

4 Hagstrom, p. 123.

5 Here and throughout, these terms are used only in the strict sense of interlingual translating and translation. On the three types of translation in the broader sense of the word, intralingual, interlingual, and intersemiotic, see Roman Jakobson, “On Linguistic Aspects of Translation”, in Reuhen A. Brower (ed.), On Translation (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1959), pp. 232-239.

6 Roger Goffin, “Pour une formation universitaire ‘sui generis’ du traducteur: Réflexions sur certain aspects méthodologiques et sur la recherche scientifique dans le domaine de la traduction”, Meta, 16 (1971), 57-68, see esp. p. 59.

7 See the Hagstrom quotation in section 1.1. above.

8 Though, given the lack of a general paradigm, scholars frequently tend to restrict the meaning of the term to only a part of the discipline. Often, in fact, it would seem to be more or less synonymous with “translation theory”.

9 Eugene Nida, Towards a Science of Translating,with Special Reference to Principles and Procedures Involved in Bible Translating (Leiden: Brill, 1964).

10 Cf. Nida’s later enlightening remark on his use of the term: “the science of translation (or, perhaps more accurately stated, the scientific description of the processes involved in translating)”, Eugene A. Nida, “Science of Translation”, Language, 45 [1969], 483-498, quotation p. 483 n. 1; my italics).

第一章翻译研究名与实11 K. Richard Bausch, Josef Klegraf, and Wolfram Wilss, The Science of Translation: An Analytical Bibliography (Tübingen: Tübinger Beitr?ge zur Linguistik). Vol. I (1970; TBL, No. 21) covers the years 1962-1969; Vol.

II(1972; TBL, No. 33) the years 1970-1971 plus a supplement over the years covered by the first volume.

12 Werner Koller, “übersetzen, übersetzung und üIbersetzer. Zu schwedischen Symposien über Probleme der übersetzung”, Babel, 17 (1971), 311, quotation p. 4. See further in this article (also p. 4) the summary of a paper “Ubersetzungspraxis, Ubersetzungstheorie und Ubersetzungswissenschaft” presented by Koller at the Second Swedish-German Translators’ Symposium, held in Stockholm, 23-24 October 1969.

13 Carl G. Hempel, Fundamentals of Concept Formation in Empirical Science (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1967; International Encyclopedia of Social Science, Foundations of the Unity of Sciences, II, Fasc. 7), p. 1.

14 I. A. Richards, “Toward a Theory of Translating”, in Arthur F. Wright (ed.), Studies in Chinese Thought (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1953; also published as Memoirs of the American Anthropological Association, 55 [1953], Memoir 75), pp. 247-262.

15 Bacon’s distinction was actually not between two types of research in

the broader sense, but of experiments: “Experiments of Use” as against “Experiments of Light”. See S. Pit Corder, “Problems and Solutions in Applied Linguistics”, paper presented in a plenary session of the 1972 Copenhagen

Congress of Applied Linguistics.

延伸阅读

Baker, Mona. (Ed.) (1998). Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies.

London / New York: Routledge.

Toury, Gideon. (1995). Descriptive Translation Studies and Beyond.

Amsterdam / Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Venuti, Lawrence. (Ed.) (2000). The Translation Studies Reader. London / New York: Routledge.

当代西方翻译研究原典选读

思考题

1、简述霍姆斯主张用“翻译研究”作为学科名称的理由。

2、霍姆斯对翻译研究的定义是什么?

3、简述描写翻译研究涵盖的领域。

4、简述理论翻译研究与描写翻译研究之间的关系。

5、为什么说翻译史与翻译方法论虽然没有被包括在结构图之内,但同样

属于翻译研究的重要组成部分?

第一章 翻译研究名与实

21 内容提要 霍姆斯的这篇文章一直被翻译研究界视为具有划时代的重要意义。两千多年以来,人们对翻译的方方面面进行了不懈的探讨,但对翻译研究作为一门学科的研究对象、研究范围以及研究方法却不甚明了,或莫衷一是。首先,霍姆斯提出将翻译研究(Translation Studies )作为学科的称谓,并强调翻译研究是一门经验学科,研究对象是翻译活动(过程)和翻译作品;翻译研究的功能是不仅要探讨如何翻译,同时还要描述翻译现象和行为,解释、甚至预测未来的翻译。更重要的是,霍姆斯第一次详尽地描绘出翻译研究的结构图(见下页)。 对照这个图可以发现,翻译研究的领域比我们传统想像的要宽阔得多。黑体是我国研究较为深入的领域,而下划线表示还有待加强。此外,还有一些未开垦的处女地。这个结构图同时表示了翻译研究自下而上的发展路径:首先 作者简介 詹姆斯·霍姆斯(James Holmes ),著名的翻译理论家。生于美国艾奥瓦中部,曾就读于威廉·潘学院和布朗大学;1949年作为富布赖特交换教师到荷兰国际学院任教,1950年移居阿姆斯特丹,以自由编辑和诗歌翻译为业。1956年以非本族语使用者身份荣获翻译大奖,1964年任阿姆斯特丹大学翻译研究高级讲师。发表多篇有关翻译的论文,《翻译研究名与实》(The Name and Nature of Translation Studies, 1972)第一次比较完整系统地界定了翻译研究作为一个跨学科的研究领域,成为当代翻译研究划时代的重要文献,得到国际译界的普遍认可。本篇选自James Holmes 的Translated! Papers on Literary and Translation Studies ,由Rodopi 出版社于1994年出版。 第一章 翻译研究名与实 The Name and Nature of Translation Studies 1 James S. Holmes

《大学》原文和译文

《大学》原文及译文 大学简介 《大学》原本是《礼记》中的一篇。宋代人把它从《礼记》中抽出来,与《论语》、《孟子》、《中庸》相配合,到朱熹撰《四书章句集注》时,便成了“四书”之一。 按朱熹和宋代另一位著名学者程颐的看法,《大学》是孔子及其门徒留下来的遗书,是儒学的人门读物。所以,朱熹把它列为“四书”之首。 朱熹又认为收在礼记中的《大学》本子有错乱,便把它重新编排了一番,分为“经”和“传”两个部分。其中“经”一章,是孔子的原话,由孔子的学生曾子记录;“传”十章,是曾子对“经”的理解和阐述,由曾子的学生记录。 这样一编排,便有了我们今天所见到的《大学》版本。 【原文】 大学之道,在明明德,在亲民,在止于至善。 知止而后有定,定而后能静,静而后能安,安而后能虑,虑而后能得。 物有本末,事有终始。知所先后,则近道矣。 【译文】 大学的宗旨在于弘扬光明正大的品德,在于使人弃旧图新,在于使人达到最完善的境界。知道应达到的境界才能够志向坚定;志向坚定才能够镇静不躁;镇静不躁才能够心安理得;心安理得才能够思虑周详;思虑周详才能够有所收获。 每样东西都有根本有枝末,每件事情都有开始有终结。明白了这本末始终的道理,就接近事物发展的规律了。

【原文】 古之欲明明德于天下者,先治其国。欲治其国者,先齐其家。欲齐其家者,先修其身。欲修其身者,先正其心。欲正其心者,先诚其意。欲诚其意者,先致其知;致知在格物。物格而后知至,知至而后意诚,意诚而后心正,心正而后身修,身修而后家齐,家齐而后国治,国治而后天下平。 【译文】 古代那些要想在天下弘扬光明正大品德的人,先要治理好自己的国家;要想治理好自己的国家,先要管理好自己的家庭和家族;要想管理好自己的家庭和家族,先要修养自身的品性;要想修养自身的品性,先要端正自己的心思;要想端正自己的心思,先要使自己的意念真诚;要想使自己的意念真诚,先要使自己获得知识;获得知识的途径在于认识、研究万事万物。 通过对万事万物的认识,研究后才能获得知识;获得知识后意念才能真诚;意念真诚后心思才能端正;心思端正后才能修养品性;品性修养后才能管理好家庭和家族;管理好家庭和家族后才能治理好国家;治理好国家后天下才能太平。 【原文】 自天子以至于庶人,壹是皆以修身为本。其本乱而末治者,否矣。其所厚者薄,而其所薄者厚,未之有也! 【译文】 上自国家君王,下至平民百姓,人人都要以修养品性为根本。若这个根本被扰乱了,家庭、家族、国家、天下要治理好是不可能的。不分轻重缓急、本末倒置却想做好事情,这也同样是不可能的! 【原文】 《康诰》曰:“克明德。”《太甲》曰:“顾是天之明命。”《帝典》曰:“克

大学英语2翻译原文及答案

Unit1 1.背离传统需要极大的勇气 1) It takes an enormous amount of courage to make a departure from the tradition. 2.汤姆过去很腼腆,但这次却非常勇敢能在大庭广众面前上台表演了。 2) Tom used to be very shy, but this time he was bold enough to give a performance in front of a large audience. 3.很多教育家认为从小培养孩子的创新精神是很可取的。 3) Many educators think it desirable to foster the creative spirit in the child at an early age. 4.假设那幅画确实是名作,你觉得值得购买吗? 4) Assuming (that) this painting really is a masterpiece, do you think it’s worthwhile to buy/purchase it? 5.如果这些数据统计上市站得住脚的,那它将会帮助我们认识正在调查的问题。 5) If the data is statistically valid, it will throw light on the problem we are investigating. Unit2 1.该公司否认其捐款有商业目的。 1) The company denied that its donations had a commercial purpose.

the-name-and-nature-of-translation-studies《翻译学的名与实》

I. 霍姆斯其人:1924-1986 生平:霍姆斯出生在美国Iowa爱荷华州,后在宾夕法尼亚州的哈弗福德Haverford学院学习英语文学,1949年受富布莱特项目Fulbright Project资助来到荷兰,从此荷兰成为他的第二故乡。他虽然一直保留美国国籍,但绝大部分时间是在荷兰度过的。 霍姆斯师从阿姆斯特丹大学荷兰文学系主任,接触了大量荷语文学作品。他从五十年代处就开始将荷语文学介绍到英语世界,此间也没有间断自己的诗歌创作,他的翻译理论研究工作则始于60年代末期。在他的老师改任阿姆斯特丹大学综合文学系主任后,霍姆斯被聘为该系教师,除教授文学翻译实践外,他还率先开设了翻译理论课程。霍姆斯同时还在以培养翻译人才为目标的阿姆斯特丹翻译学院任教。他极力促成将该学院并入阿姆斯特丹大学人文学院,但1982年二者正式合并并且成立翻译系以后,作为翻译领域最重要的学者,霍姆斯没有顺理成章地成为该系教授,原因之一是他没有博士学位,另一方面则是因为它的同性恋行为、反传统的着装及他在翻译方面的见解为该系一些教员所不容,而霍姆斯也无意为他人而改变自己的生活方式。他于1985年辞去在阿姆斯特丹大学的教职,次年因艾滋病去世,时年62岁。 成就:霍姆斯在诗歌创作、诗歌翻译和翻译理论研究等方面都有突出成就。 首先,他是一个诗歌翻译家。 霍姆斯最大的贡献在于充当荷兰在英语世界中的文学大使,使世界认识到荷兰文学的存在。他的第一部译作是1955年出版的《当代荷兰诗选》,在此后30多年的翻译生涯中,他介绍过荷语地区几乎所有重要诗人的作品。 早在1956年,霍姆斯获得象征荷兰文学翻译界最高荣誉的马丁内斯·那霍夫奖(Martinus Nijhoff Prize),成为第一位获此殊荣的外国人。他还在晚年1984年获得弗兰芒地区首届荷兰语文学奖,是迄今为止唯一获得两个翻译奖项的人。 其次,霍姆斯是一个同性恋诗人。 霍姆斯的诗作既有韵律诗又有自由体诗,绝大多数都是同性恋题材。之前他也翻译过一些有同性恋倾向的诗歌。顾忌到作品中过于直露的描写会给自己带来麻烦,霍姆斯在多数作品中都采用笔名,晚年出版的内容相对含蓄才署了真名。 第三,霍姆斯是一个编辑。 作为“翻译研究系列丛书”的总主编,霍姆斯推出了一系列翻译理论著作,来扶植翻译界的同仁和后辈。此外他还与人合办文学刊物。 最后,霍姆斯是个翻译理论家。低地国家,特指荷兰、比利时和卢森堡。因其海拔低而得名。

大学全文及解释

大学全文及解释文件排版存档编号:[UYTR-OUPT28-KBNTL98-UYNN208]

《大学》全文及解释1大学之道,在明明德,在亲民,在止于至善。 译文:于大学的宗旨在弘扬光明正大的品德,在于使人弃旧图新,在于使人达到最完善的境界 2知止而后有定,定而后能静,静而后能安,安而后能虑,虑而后能得。 译文:知道应达到的境界才能够志向坚定;志向坚定才能够镇静不躁;镇静不躁才能够心安理得;心安理得才能够思虑周详;思虑周详才能够有所收获。 3物有本末,事有终始。知所先后,则近道矣。 【译文】每样东西都有根本有枝末,每件事情都有开始有终结。明白了这本末始终的道理,就接近事物发展的规律了 4【原文】 古之欲明明德于天下者,先治其国。欲治其国者,先齐其家。欲齐其家者,先修其身。欲修其身者,先正其心。欲正其心者,先诚其意。欲诚其意者,先致其知;致知在格物。物格而后知至,知至而后意诚,意诚而后心正,心正而后身修,身修而后家齐,家齐而后国治,国治而后天下平。 【译文】 古代那些要想在天下弘扬光明正大品德的人,先要治理好自己的国家;要想治理好自己的国家,先要管理好自己的家庭和家族;要想管理好自己的家庭和家族,先要修养自身的品性;要想修养自身的品性,先要端正自己的心思;要想端正自己的心思,先要使自己的意念真诚;要想使自己的意念真诚,先要使自己获得知识;获得知识的途径在于认识、研究万事万物。

通过对万事万物的认识,研究后才能获得知识;获得知识后意念才能真诚;意念真诚后心思才能端正;心思端正后才能修养品性;品性修养后才能管理好家庭和家族;管理好家庭和家族后才能治理好国家;治理好国家后天下才能太平。 5物物格而后知至,知至而后意诚,意诚而后心正,心正而后身修,身修而后家齐,家齐而后国治,国治而后天下平 译文:通过对万事万物的认识、研究后才能获得知识;获得知识后意念才能真诚;意念真诚后心思才能端正;心思端正后才能修养品性;品性修养后才能管理好家庭和家族;管理好家庭和家族后才能治理好国家;治理好国家后天下才能太平 6【原文】 自天子以至于庶人,壹是皆以修身为本。其本乱而末治者,否矣。其所厚者薄,而其所薄者厚,未之有也! 【译文】 上自国家君王,下至平民百姓,人人都要以修养品性为根本。若这个根本被扰乱了,家庭、家族、国家、天下要治理好是不可能的。不分轻重缓急、本末倒置却想做好事情,这也同样是不可能的! 7【原文】“如切如磋”者,道学也;“如琢如磨”者,自修也;。 【译文】这里所说的“像加工骨器,不断切磋”,是指做学问的态度;这里所说的“像打磨美玉,反复琢磨”,是指自我修炼的精神; 8君子贤其贤而亲其亲;小人乐其乐而利其利,此以没世不忘也。 【译文】君主贵族们能够以前代的君王为榜样,尊重贤人,亲近亲族,一般平民百姓也都蒙受恩泽,享受安乐,获得利益。所以,虽然前代君王已经去世,但人们是永远不会忘记他们的。 9【原文】所谓致知在格物者,言欲致吾之知,在即物而穷其理也

《大学》原文和译文对照

原文译文

大学之道,在明明德,在亲民,在止于至善。 知止而后有定,定而后能静,静而后能安,安而后能虑,虑而后能得。物有本末,事有终始,知所先后,则近道矣。 古之欲明明德于天下者,先治其国,欲治其国者,先齐其家;欲齐其家者,先修其身;欲修其身者,先正其心;欲正其心者,先诚其意;欲诚其意者,先致其知;致知在格物。 物格而后知至,知至而后意诚,意诚而后心正,心正而后身修,身修而后家齐,家齐而后国治,国治而后天下平。 自天子以至于庶人,一是皆以修身为本。其本乱而末治者,否矣;其所厚者薄,而其所薄者厚,未之有也。此谓知本,此谓知之至也。 所谓诚其意者,毋自欺也。如恶恶臭,如好好色,此之谓自谦。故君子必慎其独也。小人闲居为不 大学的宗旨在于弘扬光明正大的品德,在于使人弃旧图新,在于使人达到最完善的境界。 知道应达到的境界才能够志向坚定;志向坚定才能够镇静不躁;镇静不躁才能够心安理得;心安理得才能够思虑周祥;思虑周祥才能够有所收获。每样东西都有根本有枝未,每件事情都有开始有终结。明白了这本末始终的道理,就接近事物发展的规律了。 古代那些要想在天下弘扬光明正大品德的人,先要治理好自己的国家;要想治理好自己的国家,先要管理好自己的家庭和家族;要想管理好自己的家庭和家族,先要修养自身的品性;要想修养自身的品性,先要端正自己的心思;要想端正自己的心思,先要使自己的意念真诚;要想使自己的意念真诚,先要使自己获得知识;获得知识的途径在于认识、研究万事万物。

善,无所不至;见君子而后厌然,掩其不善,而著其善。人之视己,如见其肺肝然,则何益矣。此谓诚于中,形于外。 故君子必慎其独也。曾子曰:“十目所视,十手所指,其严乎!”富润屋,德润身,心广体胖,故君子必诚其意。 《诗》云:“赡彼淇澳,绿竹猗猗;有斐君子,如切如磋,如琢如磨;瑟兮涧兮,赫兮喧兮;有斐君子,终不可煊兮。”如切如磋者,道学也;如琢如磨者,自修也;瑟兮涧兮者,恂溧也;赫兮喧兮则,威仪也;有斐君子,终不可煊兮者,道盛德至善,民之不能忘也。 《诗》云:“于戏!前王不忘。”君子贤其贤而亲其亲,小人乐其乐而利其利,此以没世不忘也。 《康诰》曰:“克明德。”《大甲》曰:“顾是天之明命。”《帝典》曰:“克明峻德。”皆自明也。 汤之《盘铭》曰:“苟日新,日 通过对万事万物的认识、研究后才能获得知识;获得知识后意念才能真诚;意念真诚后心思才能端正;心思端正后才能修养品性;品性修养后才能管理好家庭和家族;管理好家庭和家族后才能治理好国家;治理好国家后天下才能太平。 上自国家元首,下至平民百姓,人人都要以修养品性为根本。若这个根本被扰乱了,家庭、家族、国家、天下要治理好是不可能的。不分轻重缓急,本末倒置却想做好事情,这也同样是不可能的!这就叫做抓住了根本,这就叫知识达到顶点了。 使意念真诚的意思是说,不要自己欺骗自己。要像厌恶腐臭的气味一样,要像喜爱美丽的女人一样,一切都发自内心。所以,品德高尚的人哪怕是在一个人独处的时候,也一定要谨慎。品德低下的人在私下里无恶不作,一见到品德高尚的人便躲躲闪闪,掩盖自己所做的坏事而自吹自擂。

大学体验英语(第三版)课文原文及翻译

Frog Story蛙的故事 A couple of odd things have happened lately.最近发生了几桩怪事儿。 I have a log cabin in those woods of Northern Wisconsin.I built it by hand and also added a greenho use to the front of it.It is a joy to live in.In fact,I work out of my home doing audio production and en vironmental work.As a tool of that trade I have a computer and a studio.我在北威斯康星州的树林中有一座小木屋。是我亲手搭建的,前面还有一间花房。住在里面相当惬意。实际上我是在户外做音频制作和环境方面的工作——作为干这一行的工具,我还装备了一间带电脑的工作室。 I also have a tree frog that has taken up residence in my studio.还有一只树蛙也在我的工作室中住了下来。 How odd,I thought,last November when I first noticed him sitting atop my sound- board over my computer.I figured that he(and I say he,though I really don’t have a clue if she is a he or vice versa)would be more comfortable in the greenhouse.So I put him in the greenhouse.Back he ca me.And stayed.After a while I got quite used to the fact that as I would check my morning email and online news,he would be there with me surveying the world.去年十一月,我第一次惊讶地发现他(只是这样称呼罢了,事实上我并不知道该称“他”还是“她”)坐在电脑的音箱上。我把他放到花房里去,认为他待在那儿会更舒服一些。可他又跑回来待在原地。很快我就习惯了有他做伴,清晨我上网查收邮件和阅读新闻的时候,他也在一旁关注这个世界。 Then,last week,as he was climbing around looking like a small gray/green human,I started to won der about him.可上周,我突然对这个爬上爬下的“小绿人或小灰人”产生了好奇心。 So,there I was,working in my studio and my computer was humming along.I had to stop when Tree Frog went across my view.He stopped and turned around and just sat there looking at me.Well,I sat b ack and looked at him.For five months now he had been riding there with me and I was suddenly over taken by an urge to know why he was there and not in the greenhouse,where I figured he’ d liv e a happier frog life.于是有一天,我正在工作室里干活,电脑嗡嗡作响。当树蛙从我面前爬过时,我不得不停止工作。他停下了并转过身来,坐在那儿看着我。好吧,我也干脆停下来望着他。五个月了,他一直这样陪着我。我突然有一股强烈的欲望想了解他:为什么他要待在这儿而不乐意待在花房里?我认为对树蛙来说,花房显然要舒适得多。 “Why are you here,”I found myself asking him.“你为什么待在这儿?”我情不自禁地问他。 As I looked at him,dead on,his eyes looked directly at me and I heard a tone.The tone seemed to h it me right in the center of my mind.It sounded very nearly like the same one as my computer.In that tone I could hear him“say”to me,“Because I want you to understand.”Yo.That was weird.“Understa nd what?”my mind jumped in.Then,after a moment of feeling this communication,I felt I understoo d why he was there.I came to understand that frogs simply want to hear other frogs and to communic ate.Possibly the tone of my computer sounded to him like other tree frogs.我目不转睛地盯着他,他也直视着我。然后我听到一种叮咚声。这种声音似乎一下子就进入了我的大脑中枢,因为它和电脑里发出来的声音十分接近。在那个声音里我听到树蛙对我“说”:“因为我想让你明白”。唷,太不可思议了。“明白什么?”我脑海中突然跳出了这个问题。然后经过短暂的体验这种交流之后,我觉得我已经理解了树蛙待在这儿的原因。我开始理解树蛙只是想听到其他同类的叫声并与之交流。或许他误以为计算机发出的声音就是其他树蛙在呼唤他。 Interesting.真是有趣。 I kept working.I was working on a story about global climate change and had just received a fax fro m a friend.The fax said that the earth is warming at1.9degrees each decade.At that rate I knew that the maple trees that I love to tap each spring for syrup would not survive for my children.My beautiful Wisconsin would become a prairie by the next generation.我继续工作。我正在写一个关于全球气候变化的故事。有个朋友刚好发过来一份传真,说地球的温度正以每十年1.9度的速度上升。我知道,照这种速度下去,每年春天我都爱去提取树浆的这片枫林,到我孩子的那一代就将不复存在。我的故乡美丽的威斯康星州也会在下一代变成一片草原。 At that moment Tree Frog leaped across my foot and sat on the floor in front of my computer.He th en reached up his hand to his left ear and cupped it there.He sat before the computer and reached up his right hand to his other ear.He turned his head this way and that listening to that tone.Very focuse d.He then began to turn a very subtle,but brilliant shade of green and leaped full force onto the com puter.此刻,树蛙从我脚背跳过去站在电脑前的地板上。然后他伸出手来从后面拢起左耳凝神倾听,接着他又站在电脑前伸出右手拢起另一支耳朵。他这样转动着脑袋,聆听那个声音,非常专心致志。他的皮肤起了微妙的变化,呈现出一种亮丽的绿色,然后他就用尽全力跳到电脑上。 And then I remembered the story about the frogs that I had heard last year on public radio.It said fr ogs were dying around the world.It said that because frogs’skin is like a lung turned inside out,their s

1《大学》全文及注释

《大学》 全文及翻译 大学之道,在明明德,在亲民,在止于至善。知止而后有定,定而后能静,静而后能安,安而后能虑,虑而后能得。物有本末,事有终始。知所先后,则近道矣。 《大学》的宗旨,在于弘扬高尚的德行,在于关爱人民,在于达到最高境界的善。知道要达到“至善”的境界方能确定目标,确定目标后方能心地宁静,心地宁静方能安稳不乱,安稳不乱方能思虑周详,思虑周详方能达到“至善”。凡物都有根本、有末节,凡事都有终端、有始端,知道了它们的先后次序,就与《大学》的宗旨相差不远了。

古之欲明明德于天下者,先治其国。欲治其国者,先齐其家。欲齐其家者,先修其身。欲修其身者,先正其心。欲正其心者,先诚其意。欲诚其意者,先致其知。致知在格物。物格而后知至,知至而后意诚,意诚而后心正,心正而后身修,身修而后家齐,家齐而后国治,国治而后天下平。 在古代,意欲将高尚的德行弘扬于天下的人,则先要治理好自己的国家;意欲治理好自己国家的人,则先要调整好自己的家庭;意欲调整好自己家庭的人,则先要修养好自身的品德;意欲修养好自身品德的人,则先要端正自己的心意;意欲端正自己心意的人,则先要使自己的意念真诚;意欲使自己意念真城的人,则先要获取知识;获取知识的途径则在于探究事理。探究事理后才能获得正确认识,认识正确后才能意念真城,意念真诚后才能端正心意,心意端正后才能修

养好品德,品德修养好后才能调整好家族,家族调整好后才能治理好国家,国家治理好后才能使天下大平。自天子以至于庶人,一是皆以修身为本。其本乱而末治者否矣。其所厚者薄,而其所薄者厚,未之有也。此谓知本,此谓知之至也。 从天子到普通百姓,都要把修养品德作为根本。人的根本败坏了,末节反倒能调理好,这是不可能的。正像我厚待他人,他人反而慢待我;我慢待他人,他人反而厚待我这样的事情,还未曾有过。这就叫知道了根本,这就是认知的最高境界。 所谓诚其意者,毋自欺也。如恶恶臭,如好好色,此之谓自谦。故君子必慎其独也。小人闲居为不善,无所不至,见君子而后厌然,掩其不善而著其善。人之视己,如见其肺肝然,则何益矣。此谓诚于中,形于

大学全文及译文

《大学》全文及译文 大学之道,在明明德,在亲民,在止于至善。知止而后有定,定而后能静,静而后能安,安而后能虑,虑而后能得。物有本末,事有终始,知所先后,则近道矣。 古之欲明明德于天下者,先治其国,欲治其国者,先齐其家;欲齐其家者,先修其身;欲修其身者,先正其心;欲正其心者,先诚其意;欲诚其意者,先致其知,致知在格物。物格而后知至,知至而后意诚,意诚而后心正,心正而后身修,身修而后家齐,家齐而后国治,国治而后天下平。自天子以至于庶人,壹是皆以修身为本。其本乱而末治者,否矣。其所厚者薄,而其所薄者厚,未之有也。此谓知本,此谓知之至也。 所谓诚其意者,毋自欺也。如恶恶臭,如好好色,此之谓自谦。故君子必慎其独也。小人闲居为不善,无所不至,见君子而后厌然,拚其不善,而着其善。人之视己,如见其肝肺然,则何益矣。此谓诚于中形于外。故君子必慎其独也。曾子曰:“十目所视,十手所指,其严乎!”富润屋,德润身,心广体胖,故君子必诚其意。诗云:“赡彼淇澳,绿竹猗猗,有斐君子,如切如磋,如琢如磨,瑟兮涧兮,赫兮喧兮,有斐君子,终不可煊兮。”如切如磋者,道学也;如琢如磨者,自修也;瑟兮涧兮者,恂溧也;赫兮喧兮则,威仪也;有斐君子,终不可煊兮者,道盛德至善,民之不能忘也。诗云:“于戏!前王不忘。”君子贤其贤而亲其亲,小人乐其乐而利其利,此以没世不忘也。康诰曰:“克明德。”大甲曰:“顾是天之明命。”帝典曰:“克明峻德。”皆自明也。汤之盘铭曰:“苟日新,日日新,又日新。”康诰曰:“作新民。”诗云:“周虽旧邦,其命维新。”是故君子无所不用其极。诗云:“邦畿千里,唯民所止。”诗云:“绵蛮黄鸟,止于丘隅。”子曰:“于止,知其所止,可以人而不如鸟乎?”诗云:“穆穆文王,于缉熙敬止。”为人君止于仁,为人臣止于敬,为人子止于孝,为人父止于慈,与国人交止于信。子曰:“听讼,吾犹人也,必也使无讼乎!”无情者不得尽其辞,大畏民志,此谓知本。

文言文的实词与例句翻译

文言文的实词及例句翻译 1、爱 爱护 例:父母之爱子,则为之计深远(爱护) 《触龙说太后》译文:父母疼爱子女,就应该替他们做长远打算。 喜欢,爱好 例:爱纷奢,人亦念其家(喜欢,爱好) 《阿房宫赋》译文:统治者爱好繁华奢侈,人民也都顾念自己的家。 舍不得,吝惜,爱惜 例:齐国虽褊小,我何爱一牛(吝惜)《齐桓晋文之事》译文:齐国虽然土地狭小,我怎么会吝惜一条牛? 爱慕,欣赏 例:予独爱莲之出淤泥而不染(爱慕,欣赏) 《爱莲说》译文:我只欣赏莲花从污泥中生长出来却不沾染(污秽)。 恩惠 例:古之遗爱也(恩惠) 《左传》译文:(子产执政之道,)正是古人遗留下的恩惠啊。 隐蔽,躲藏 例:爱而不见,搔首踯躅(隐蔽,躲藏) 《诗经静女》译文:却隐藏起来找不到,急得我搔头又徘徊。 怜惜,同情 例:爱其二毛(怜惜,同情)《左传》译文:怜惜鬓发花白的老人。 2、安 安全,安稳,安定 例:风雨不动安如山(安稳) 《茅屋为秋风所破歌》译文:风雨无忧安稳如大山 安抚,抚慰 例:则宜抚安,与结盟好(安抚,抚慰) 《赤壁之战》译文:就应当安慰他们,与他们结盟友好

安置、安放 例:离山十里有王平安营(安置、安放)《失街亭》译文:距离山十里地有王王平在那里安置营寨。 使安 例:既来之,则安之(使安定)《季氏将伐颛臾》译文:他们来了,就得使他们安心。 疑问代词:哪里,怎么 例:将军迎操,欲安所归乎(哪里) 《赤壁之战》译文:将军您迎顺操,想要得到一个什么归宿呢? 养生 例:衣食所安(养生) 《刿论战》译文:衣服、食品这些养生的东西。 3、被 读音一:bèi 被子(名词) 例:一日昼寝帐中,落被于地(被子) 《修之死》译文:一天白天,(操)正在大帐中睡觉的时候,被子掉到地上了。 覆盖(动词) 例:大雪逾岭,被南越中数州(覆盖)《答韦中立论师道书》译文:大雪越过南岭。覆盖了南越之地的几个州郡。 遭受,遇到,蒙受 例:世之有饥穰,天之行也,禹、汤被之矣(蒙受,遭受)《论积贮疏》译文:年成有好坏(荒年、丰年),(这是)大自然常有的现象,夏禹、商汤都遭受过。 加 例:幸被齿发,何敢负德(加)《柳毅传》译文:承蒙您的大恩大德,我怎敢忘记? 介词,表示被动 例:信而见疑,忠而被谤,能无怨乎(表示被动)《屈原列传》译文:诚信而被怀疑,尽忠却被诽谤,能没有怨愤吗? 读音二:p,通"披" 穿在身上或披在身上

《大学》全文及解释

《大学》全文及解释 1大学之道,在明明德,在亲民,在止于至善。 译文:于大学的宗旨在弘扬光明正大的品德,在于使人弃旧图新,在于使人达到最完善的境界 2知止而后有定,定而后能静,静而后能安,安而后能虑,虑而后能得。 译文:知道应达到的境界才能够志向坚定;志向坚定才能够镇静不躁;镇静不躁才能够心安理得;心安理得才能够思虑周详;思虑周详才能够有所收获。 3物有本末,事有终始。知所先后,则近道矣。 【译文】每样东西都有根本有枝末,每件事情都有开始有终结。明白了这本末始终的道理,就接近事物发展的规律了 4【原文】 古之欲明明德于天下者,先治其国。欲治其国者,先齐其家。欲齐其家者,先修其身。欲修其身者,先正其心。欲正其心者,先诚其意。欲诚其意者,先致其知;致知在格物。物格而后知至,知至而后意诚,意诚而后心正,心正而后身修,身修而后家齐,家齐而后国治,国治而后天下平。 【译文】 古代那些要想在天下弘扬光明正大品德的人,先要治理好自己的国家;要想治理好自己的国家,先要管理好自己的家庭和家族;要想管理好自己的家庭和家族,先要修养自身的品性;要想修养自身的品性,先要端正自己的心思;要想端正自己的心思,先要使自己的意念真诚;要想使自己的意念真诚,先要使自己获得知识;获得知识的途径在于认识、研究万事万物。通过对万事万物的认识,研究后才能获得知识;获得知识后意念才能真诚;意念真诚后心思才能端正;心思端正后才能修养品性;品性修养后才能管理好家庭和家族;管理好家庭和家族后才能治理好国家;治理好国家后天下才能太平。 5物物格而后知至,知至而后意诚,意诚而后心正,心正而后身修,身修而后家齐,家齐而后国治,国治而后天下平 译文:通过对万事万物的认识、研究后才能获得知识;获得知识后意念才能真诚;意念真诚后心思才能端正;心思端正后才能修养品性;品性修养后才能管理好家庭和家族;管理好家庭和家族后才能治理好国家;治理好国家后天下才能太平 6【原文】 自天子以至于庶人,壹是皆以修身为本。其本乱而末治者,否矣。其所厚者薄,而其所薄者厚,未之有也! 【译文】 上自国家君王,下至平民百姓,人人都要以修养品性为根本。若这个根本被扰乱了,家庭、家族、国家、天下要治理好是不可能的。不分轻重缓急、本末倒置却想做好事情,这也同样是不可能的! 7【原文】“如切如磋”者,道学也;“如琢如磨”者,自修也;。 【译文】这里所说的“像加工骨器,不断切磋”,是指做学问的态度;这里所说的“像打磨美玉,反复琢磨”,是指自我修炼的精神; 8君子贤其贤而亲其亲;小人乐其乐而利其利,此以没世不忘也。 【译文】君主贵族们能够以前代的君王为榜样,尊重贤人,亲近亲族,一般平民百姓也都蒙受恩泽,享受安乐,获得利益。所以,虽然前代君王已经去世,但人们是永远不会忘记他们的。

《大学》全文及翻译

《大学》全文及翻译 【原文】 大学之道,在明明德,在亲民,在止于至善。 知止而后有定,定而后能静,静而后能安,安而后能虑,虑而后能得。 物有本末,事有终始。知所先后,则近道矣。 【译文】 大学的宗旨在于彰显光明正大(人生本来的)的品德,在于亲厚百姓,在于达到最完美的境界。 知道应达到的最完美的境界,而后能够志向坚定;志向坚定而后能够心静(志向专一,心无旁骛);心静下来而后能够身心俱安(不为外物所牵累、所转移);身心俱安而后能够慎思明辨;慎思明辨而后能够有所收获。 每样东西都有根本、有枝末,每件事情都有开始、有结束。明白了这本末和始终的道理(有纲目,有步骤,有层次,有递进,有因果),就接近了(人、物、事的)自然规律。 【原文】 古之欲明明德于天下者,先治其国。欲治其国者,先齐其家。欲齐其家者,先修其身。欲修其身者,先正其心。欲正其心者,先诚其意。欲诚其意者,先致其知;致知在格物。 物格而后知至,知至而后意诚,意诚而后心正,心正而后身修,身修而后家齐,家齐而后国治,国治而后天下平。

【译文】 古代那些想要治理天下的人,先要治理好自己的国家;想要治理好自己的国家,先要管理好自己的家庭;想要管理好自己的家庭,先要修养自身的德性;想要修养自身的德性,先要端正自己的心;想要端正自己的心,先要使自己的意念真诚;想要使自己的意念真诚,先要使自己明辨事理;明辨事理的途径在于探究万事万物。 对万事万物探究之后,就能明辨事理;明辨事理之后,意念就能真诚;意念真诚之后,心就能端正;心端正之后,德性就得到修养;德性得到修养之后,家庭就能管理好;家庭管理好之后,国家就能治理好;国家治理好之后,就能管理好天下,使天下太平。 【原文】 自天子以至于庶人,壹是皆以修身为本。其本乱而末治者,否矣。其所厚者薄,而其所薄者厚,未之有也! 【译文】 上自天子,下至百姓,人人都要以修养自身德性为根本。没有这个根本,却想把家庭、国家、天下都治理好,那是不可能的。心想厚待而实际薄待,心想薄待而实际厚待,这种情况是没有的(所有人都不会违背自己的内心,其做任何事情都是受内心的支配。诚于善则行善,诚于恶则行恶)。 【原文】

《大学》全文及解释(精品)

《大学》全文及解释 1大学之道,在明明德,在亲民,在止于至善。 译文:于大学的宗旨在弘扬光明正大的品德,在于使人弃旧图新,在于使人达到最完善的境界 2知止而后有定,定而后能静,静而后能安,安而后能虑,虑而后能得. 译文:知道应达到的境界才能够志向坚定;志向坚定才能够镇静不躁;镇静不躁才能够心安理得;心安理得才能够思虑周详;思虑周详才能够有所收获。 3物有本末,事有终始。知所先后,则近道矣. 【译文】每样东西都有根本有枝末,每件事情都有开始有终结。明白了这本末始终的道理,就接近事物发展的规律了 4【原文】 古之欲明明德于天下者,先治其国。欲治其国者,先齐其家。欲齐其家者,先修其身。欲修其身者,先正其心.欲正其心者,先诚其意。欲诚其意者,先致其知;致知在格物。物格而后知至,知至而后意诚,意诚而后心正,心正而后身修,身修而后家齐,家齐而后国治,国治而后天下平。 【译文】 古代那些要想在天下弘扬光明正大品德的人,先要治理好自己的国家;要想治理好自己的国家,先要管理好自己的家庭和家族;要想管理好自己的家庭和家族,先要修养自身的品

性;要想修养自身的品性,先要端正自己的心思;要想端正自己的心思,先要使自己的意念真诚;要想使自己的意念真诚,先要使自己获得知识;获得知识的途径在于认识、研究万事万物。...感谢阅览... 通过对万事万物的认识,研究后才能获得知识;获得知识后意念才能真诚;意念真诚后心思才能端正;心思端正后才能修养品性;品性修养后才能管理好家庭和家族;管理好家庭和家族后才能治理好国家;治理好国家后天下才能太平。 5物物格而后知至,知至而后意诚,意诚而后心正,心正而后身修,身修而后家齐,家齐而后国治,国治而后天下平 译文:通过对万事万物的认识、研究后才能获得知识;获得知识后意念才能真诚;意念真诚后心思才能端正;心思端正后才能修养品性;品性修养后才能管理好家庭和家族;管理好家庭和家族后才能治理好国家;治理好国家后天下才能太平 6【原文】 自天子以至于庶人,壹是皆以修身为本。其本乱而末治者,否矣。其所厚者薄,而其所薄者厚,未之有也! 【译文】 上自国家君王,下至平民百姓,人人都要以修养品性为根本。若这个根本被扰乱了,家庭、家族、国家、天下要治理好是不可能的.不分轻重缓急、本末倒置却想做好事情,这也同样

最新《大学》原文和翻译

原文: 大学之道,在明明德,在亲民,在止于至善。知止而后有定,定而后能静,静而后能安,安而后能虑,虑而后能得。物有本末,事有终始,知所先后,则近道矣。古之欲明明德于天下者,先治其国,欲治其国者,先齐其家;欲齐其家者,先修其身;欲修其身者,先正其心;欲正其心者,先诚其意;欲诚其意者,先致其知,致知在格物。物格而后知至,知至而后意诚,意诚而后心正,心正而后身修,身修而后家齐,家齐而后国治,国治而后天下平。自天子以至于庶人,壹是皆以修身为本。其本乱而末治者,否矣。其所厚者薄,而其所薄者厚,未之有也。此谓知本,此谓知之至也。所谓诚其意者,毋自欺也。如恶恶臭,如好好色,此之谓自谦。故君子必慎其独也。小人闲居为不善,无所不至,见君子而后厌然,拚其不善,而著其善。人之视己,如见其肝肺然,则何益矣。此谓诚于中形于外。故君子必慎其独也。曾子曰:“十目所视,十手所指,其严乎!”富润屋,德润身,心广体胖,故君子必诚其意。诗云:“赡彼淇澳,绿竹猗猗,有斐君子,如切如磋,如琢如磨,瑟兮涧兮,赫兮喧兮,有斐君子,终不可煊兮。”如切如磋者,道学也;如琢如磨者,自修也;瑟兮涧兮者,恂溧也;赫兮喧兮则,威仪也;有斐君子,终不可煊兮者,道盛德至善,民之不能忘也。诗云:“于戏!前王不忘。”君子贤其贤而亲其亲,小人乐其乐而利其利,此以没世不忘也。康诰曰:“克明德。”大甲曰:“顾是天之明命。”帝典曰:“克明峻德。”皆自明也。汤之盘铭曰:“苟日新,日日新,又日新。”康诰曰:“作新民。”诗云:“周虽旧邦,其命维新。”是故君子无所不用其极。诗云:“邦畿千里,唯民所止。”诗云:“绵蛮黄鸟,止于丘隅。”子曰:“于止,知其所止,可以人而不如鸟乎?”诗云:“穆穆文王,于缉熙敬止。”为人君止于仁,为人臣止于敬,为人子止于孝,为人父止于慈,与国人交止于信。子曰:“听讼,吾犹人也,必也使无讼乎!”无情者不得尽其辞,大畏民志,此谓知本。所谓修身在正其心者,身有所忿惕则不得其正,有所恐惧则不得其正,有所好乐则不得其正,有所忧患则不得其正。心不在焉,视而不见,听而不闻,食而不知其味,此谓修身在正其心。所谓齐其家在修其身者,人之其所亲爱而辟焉,之其所贱恶而辟焉,之其所敬畏而辟焉,之其所哀矜而辟焉,之其所敖惰而辟焉,故好而知其恶,恶而知其美者,天下鲜矣。故谚有之曰:“人莫之其子之恶,莫知其苗之硕。”此谓身不修,不可以齐其家。所谓治国必齐其家者,其家不可教,而能教人者无之。故君子不出家而成教于国。孝者,所以事君也;弟者,所以事长也;慈者,所以使众也。康诰曰:“如保赤子。”心诚求之,虽不中,不远矣。未有学养子而后嫁者也。一家仁,一国兴仁;一家让,一国兴让;一人贪戾,一国作乱,其机如此。此谓一言贲事,一人定国。尧舜率天下以仁,而民从之;桀纣率天下以暴,而民从之。其所令,反其所好,而民不从。是故君子有诸己而后求诸人,无诸己而后非诸人。所藏乎身不恕,而能喻诸人者,未之有也。故治国在齐其家。诗云:“桃之夭夭,其叶蓁蓁,之子于归,宜其家人。”宜其家人而后可以教国人。诗云:“宜兄宜弟。”宜兄宜弟,而后可以教国人。诗云:“其仪不忒,正是四国。”其为父子兄弟足法,而后民法之也。此谓治国在齐其家。所谓平天下在治其国者,上老老而民兴孝,上长长而民兴弟,上恤孤而民不倍,是以君子有挈矩之道也。所恶于上,毋以使

翻译中词义的以虚代实

英语知识 英语中以虚代实,即以抽象名词指具体的人或物质的汉译。 有人认为:有必要把它们(指抽象名词)译的比较具体、明确来保证与原文相适应的可读性。我们需要首先弄清的一个问题是:将抽象名词译的比较具体、明确,究竟是指通过“译”这一手段将其“加工”成含义具体的名词呢?还是此类抽象名词本身即含有具体的意义?这是一个涉及如何正确理解及认识英语中一部分抽象名词的带普遍性意义的问题。客观情况是:英语中的一些抽象名词在特定的上下文中的含义是具体的而并非是抽象的。以有人所引的例句为例:As a boy, he was the despair of all his teachers. 句中的despair的固有含义之一是:somebody that causes loss of hope,令人失望的人。 以虚代实的抽象名词能大大简洁英语的表达,是一种不为鲜见的语言现象。就其特征而言,此类抽象名词可作何种分类呢?据笔者管见,似可分成两大类。一类是指形形色色的“人”的抽象名词,如: Is Jane a possibility (=a suitable person) as a wife for Richard? 简是做理查德妻子的合适人选吗? Our son has been a disappointment(=someone dissapointing) to us. 我们的儿子成了令我们失望的人。 He's an influence (= the person that has the power to produce a good moral effect) for good in the town. 他是这城里影响他人行善的人。 His skill at games made him the admiration (= a person that causes such feelings) of his friends. 他的运动技巧使他成为友人称羡的人。 His new car made him the envy (= a person that makes someone