Estimating-the-foreclosure-effect-of-exclusive-dealing-Evidence-from-the-entry

英国诺丁汉大学讲义如何估计随机效应模型stata课件

英国诺丁汉大学讲义如何估计随机 效应模型stata

Estimation Methods for Multilevel

Models

Due to additional random effects no simple matrix formulae exist for finding estimates in multilevel models.

• Can easily be extended to more complex problems.

• Potential downside 1: Prior distributions required for all unknown parameters.

• Potential downside 2: MCMC estimation is much slower than the IGLS algorithm.

• Here there are 4 sets of unknown parameters:

,u,u2,e2

• We will add prior distributions

p(

),p(

),p( ) 2

2

u

英e 国诺丁汉大学讲义如何估计随机

重大突发事件对原油价格的影响

第29卷第3期系统上程理论与实践V01.29.NO.3 2009年3月Syst ems En gi ne e ri ng—Th eo r y&Pr ac ti ce Mar.,2009文章编号:1000—6788(2009)03-0010-06重大突发事件对原油价格的影响张殉·,余乐安·,黎建强。

,汪寿阳-(1.中国科学院数学与系统科学研究院,北京100190;2.香港城市大学管理科学系,香港)摘要基于结构性断点检验和常收益事件分析模型,分析了伊朗革命、海湾战争和伊拉克战争三次重大突发事件对原油价格的影响.结果表明:三次事件均对原油价格走势产生了显著影响,其中伊朗革命和伊拉克战争导致了油价结构性断点的产生.三次战争对油价的影响模式均满足危机模型.关键词原油价格;突发事件;事件分析;预测中图分类号F062.1文献标志码AEstimating the effects of extreme events to cr ud e oil pri ceZHANG Xunl,1ⅢLe-anl,LAI K i n Kcun92,WANG Shou-ya n91(1.A c a d e m y of Mathematics and Systems Science,Chinese Academy of Sciences,Beijing 100190,China;2.Department of Management Science,City University of Hong Kong,Hong Kon g,Ch i na)Ab s tr ac t Based structure breakpoint test and standard event analysis model,t hi s paper analyzes the effects of Iran revolution with following Iraq-Iran war,G ul f war and Iraq way to crude oil price.It proves that all the three wars made significant impacts crude oil price and their effects consistent with the crisis model.The Iran revolution with Iraq-Iran Way and the Iraq war structure breakpoints in crude oil price.Keyw ord s crude oil pri c e;e x tr e me events;event study;forecasting1引言原油是全球重要的战略资源.一直以来,各国对原油资源和定价权的争夺异常激烈,由此引发一系列突发事件,对原油价格产生重大影响,甚至改变了原油市场定价机制.对重大突发事件的分析,有利于深入了解原油这一特殊商品的价格形成机制.在进行国际原油价格预测时,正确评估已发生的突发事件对原油价格的影响,对将来可能发生的突发事件的影响进行推测,对判断未来的价格走势具有极其重要的作用[1-3】.影响油价的突发事件通常包括:地缘政治事件(如战争,产油区武装斗争,罢工),油气设备故障(输油管道损坏,炼油厂爆炸),O PEC政策,飓风等.按照突发事件对油价影响的性质,可以进一步分成三类事件:1)台阶式事件:造成原油价格的突变,并且价格水平不再恢复到事件之前.台阶式事件造成油价进化中结构性断点的产生,其对于油价的影响是长期的.典型事件如:1973年一1974年石油危机.2)脉冲式事件:油价受事件影响发生突然的上升或者下降,当事件影响过去之后又回复到以前的水平.脉冲式事件引起的往往是短收稿日期:2008-11.27 资助项目:国家自然科学基金(70601029,70221001)作者简介:汪寿阳,通讯作者,北京市海淀区中关村东路55号,电话:010-********,Em ai l:sy wa ng@a m ss.aE.c n万方数据第3期张殉,等:重大突发书件对原油价格的影响11期影响.典型#件如:1991年8月2日伊拉克突袭科威特.3)混合式与£件:同时包含台阶’于脉冲两种效应.由j:混合式事件从长期来看也属。

因果效应中的双重稳健估计值,让你的估计精准少误

因果效应中的双重稳健估计值,让你的估计精准少误现在Stata中一个估计处理效应的通用框架teffects,可以做的处理效应种类非常多,比如PSM,NNM,RA,IPW等。

teffects allows you to write a model for the treatment and a model for the outcome. We will show how—even if you misspecify one of the models—you can still get correct estimates using doubly robust estimators.In experimental data, the treatment is randomized so that a difference between the average treated outcomes and the average nontreated outcomes estimates the average treatment effect (ATE). Suppose you want to estimate the ATE of a mother’s smoking on her baby’s birthweight. The ethical impossibility of asking a random selection of pregnant women to smoke mandates that these data be observational. Which women choose to smoke while pregnant almost certainly depends on observable covariates, such as the mother’s age.We use a conditional model to make the treatment as good as random. More formally, we assume that conditioning on observable covariates makes the outcome conditionallyindependent of the treatment. Conditional independence allows us to use differences in model-adjusted averages to estimate the ATE.The regression-adjustment (RA) estimator uses a model for the outcome. The RA estimator uses a difference in the average predictions for the treated and the average predictions for the nontreated to estimate the ATE. Below we use teffects ra to estimate the ATE when conditioning on the mother’s marital status, her education level, whether she had a prenatal visit in the first trimester, and whether it was her first baby.Mothers’ smoking lowers the average birthweight by 231 grams.The inverse-probability-weighted (IPW) estimator uses a model for the treatment instead of a model for the outcome; it uses the predicted treatment probabilities to weight the observed outcomes. The difference between the weighted treated outcomes and the weighted nontreated outcomes estimates the ATE. Conditioning on the same variables as above, we now use teffects ipw to estimate the ATE:Mothers’ smoking again lowers the average birthweight by 231 grams.We could use both models instead of one. The shocking fact is that only one of the two models must be correct to estimate the ATE, whether we use the augmented-IPW (AIPW) combination proposed by Robins and Rotnitzky (1995) or the IPW-regression-adjust ment (IPWRA) combination proposed by Wooldridge (2010).The AIPW estimator augments the IPW estimator with a correction term. The term removes the bias if the treatment model is wrong and the outcome model is correct, and the term goes to 0 if the treatment model is correct and the outcome model is wrong.The IPWRA estimator uses IPW probability weights when performing RA. The weights do not affect the accuracy of the RA estimator if the treatment model is wrong and the outcome model is correct. The weights correct the RA estimator if the treatment model is correct and the outcome model is wrong.双重稳健估计值是如下两个:aipw和ipwra。

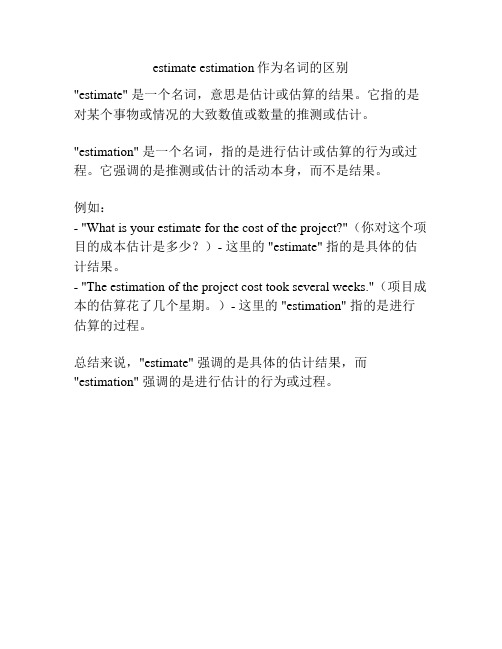

estimate estimation作为名词的区别

estimate estimation作为名词的区别

"estimate" 是一个名词,意思是估计或估算的结果。

它指的是对某个事物或情况的大致数值或数量的推测或估计。

"estimation" 是一个名词,指的是进行估计或估算的行为或过程。

它强调的是推测或估计的活动本身,而不是结果。

例如:

- "What is your estimate for the cost of the project?"(你对这个项目的成本估计是多少?)- 这里的 "estimate" 指的是具体的估计结果。

- "The estimation of the project cost took several weeks."(项目成本的估算花了几个星期。

)- 这里的 "estimation" 指的是进行估算的过程。

总结来说,"estimate" 强调的是具体的估计结果,而"estimation" 强调的是进行估计的行为或过程。

经管实证英文文献常用的缺失值处理方法

经管实证英文文献常用的缺失值处理方法Methods for Handling Missing Values in Empirical Studies in Economics and ManagementMissing values are a common issue in empirical studies in economics and management. These missing values can occur for a variety of reasons, such as data collection errors, non-response from survey participants, or incomplete information. Dealing with missing values is crucial for maintaining the quality and reliability of empirical findings. In this article, we will discuss some common methods for handling missing values in empirical studies in economics and management.1. Complete Case AnalysisOne common approach to handling missing values is to simply exclude cases with missing values from the analysis. This method is known as complete case analysis. While this method is simple and straightforward, it can lead to biased results if the missing values are not missing completely at random. In other words, if the missing values are related to the outcome of interest, excluding cases with missing values can lead to biased estimates.2. Imputation TechniquesImputation techniques are another common method for handling missing values. Imputation involves replacing missing values with estimated values based on the observed data. There are several methods for imputing missing values, including mean imputation, median imputation, and regression imputation. Mean imputation involves replacing missing values with the mean of the observed values for that variable. Median imputation involves replacing missing values with the median of the observed values. Regression imputation involves using a regression model to predict missing values based on other variables in the dataset.3. Multiple ImputationMultiple imputation is a more sophisticated imputation technique that involves generating multiple plausible values for each missing value and treating each set of imputed values as a complete dataset. This allows for uncertainty in the imputed values to be properly accounted for in the analysis. Multiple imputation has been shown to produce less biased estimates compared to single imputation methods.4. Maximum Likelihood EstimationMaximum likelihood estimation is another method for handling missing values that involves estimating the parametersof a statistical model by maximizing the likelihood function of the observed data. Missing values are treated as parameters to be estimated along with the other parameters of the model. Maximum likelihood estimation has been shown to produce unbiased estimates under certain assumptions about the missing data mechanism.5. Sensitivity AnalysisSensitivity analysis is a useful technique for assessing the robustness of empirical findings to different methods of handling missing values. This involves conducting the analysis using different methods for handling missing values and comparing the results. If the results are consistent across different methods, this provides more confidence in the validity of the findings.In conclusion, there are several methods available for handling missing values in empirical studies in economics and management. Each method has its advantages and limitations, and the choice of method should be guided by the nature of the data and the research question. It is important to carefully consider the implications of missing values and choose the most appropriate method for handling them to ensure the validity and reliability of empirical findings.。

The Cost of Diversity:the Diversification Discount and Inefficient Investment

THE JOURNAL OF FINANCE•VOL.LV,NO.1•FEBRUARY2000The Cost of Diversity:The Diversification Discount and Inefficient InvestmentRAGHURAM RAJAN,HENRI SERVAES,and LUIGI ZINGALES*ABSTRACTWe model the distortions that internal power struggles can generate in the allo-cation of resources between divisions of a diversified firm.The model predicts thatif divisions are similar in the level of their resources and opportunities,funds willbe transferred from divisions with poor opportunities to divisions with good op-portunities.When diversity in resources and opportunities increases,however,re-sources can f low toward the most inefficient division,leading to more inefficientinvestment and less valuable firms.We test these predictions on a panel of diver-sified U.S.firms during the period from1980to1993and find evidence consistentwith them.T HE FUNDAMENTAL QUESTION IN THE THEORY of the firm,raised by Coase~1937! more than60years ago,is how decisions taken inside a hierarchy differ from those taken in the marketplace.Coase suggested that decisions within a hierarchy are determined by power considerations rather than relative prices.If this is indeed the case,why,and when,does the hierarchy domi-nate the market?A major obstacle to progress in this area has been the lack of data.Data on internal decisions made by firms are generally proprietary.Even when they are available to researchers,it is difficult to find a comparable group of decisions taken in the market.A notable exception is the capital allocation decision in diversified firms.Since1978,public panies have been forced to disclose their data on sales,profitability,and investments by major lines of business~segments!.An analysis of a small sample of multisegment firms reveals that segments correspond,by and large,to distinct internal *Rajan is from the University of Chicago,Servaes is from the London Business School and University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,and Zingales is from the University of Chicago. Rajan and Zingales acknowledge financial support from the Center for Research on Security Prices at the University of Chicago.Servaes acknowledges financial support from the O’Herron and McColl faculty fellowships,University of North Carolina at Chapel ments from Sugato Bhattacharya,Judy Chevalier,Glenn Ellison,Milton Harris,Steven Kaplan,Owen La-mont,Colin Mayer,Todd Milbourn,Vikram Nanda,Jay Ritter,RenéStulz,Robert Vishny,Ralph Walkling,Wanda Wallace,two anonymous referees,and especially Mitchell Petersen are grate-fully ments from participants in seminars at AT Kearney~London!,the University of Chicago,Cornell University,the University of Georgia,the University of Florida, the University of Illinois,the London School of Economics,New York University,Northwestern University,Ohio State University,the College of William&Mary,Vanderbilt University,and Yale University were useful.3536The Journal of Financeunits of the firm.Since the investment decision is perhaps the most impor-tant of corporate decisions,these data allow researchers an opportunity to compare decisions taken by units within hierarchies with decisions taken by independent units in the same industry,and thus obtain insights on how hierarchies and markets differ.Previous research~Lamont~1997!and Shin and Stulz~1998!!has shown that resource allocation in diversified firms does appear different from that in focused firms and seems to ignore traditional market indicators of the value of investment such as Tobin’s q.Moreover,there seems to be a con-nection between resource~mis!allocation and the value of diversified firms. Berger and Ofek~1995!find that investment by diversified firms in seg-ments that have low q is correlated with the discount at which these firms trade.So perhaps such misallocation explains why diversified firms trade, on average,at a discount relative to a portfolio of single-segment firms in the same industries~Lang and Stulz~1994!,Berger and Ofek~1995!,Ser-vaes~1996!,Lins and Servaes~1999!!.But these facts simply heighten the puzzle.What is it in a hierarchy that makes diversified firms misallocate funds?Moreover,what accounts for the wide dispersion in diversified firm values,with fully39.3percent trading at a premium in1990?1To answer these questions,we first need a theoretical framework to un-derstand the phenomenon.At least three kinds of models have been pro-posed to explain how the divisions of diversified firms behave differently from stand-alone firms.Efficient Internal Capital Market models typically suggest that diversification creates value.By forming an internal capital market where the internally generated cash f lows can be pooled,diversified firms can allocate resources to their best use~e.g.,see Li and Li~1996!, Matsusaka and Nanda~1997!,Stein~1997!,Weston~1970!,and Williamson ~1975!!.2Clearly,these models do not explain the misallocation of resources to divisions with poor opportunities.Agency cost models have sometimes been offered as explanations for the potential investment distortions in diversified firms.Because top manage-ment in the diversified firm has greater opportunities to undertake projects, and potentially greater resources to do so if diversification relaxes con-straints imposed by imperfect external capital markets,it might overinvest1Also,the evidence on the value of diversification,as indicated by the stock price reaction to the decision to diversify,is decidedly mixed.Morck,Shleifer,and Vishny~1990!show that acquiring firms in the1980s experience negative returns when they announce unrelated ac-quisitions.John and Ofek~1995!find that announcement returns are greater when diversified firms in the late1980s announce asset sales that increase focus.By contrast,Schipper and Thompson~1983!document positive announcement period returns when conglomerates an-nounced acquisition programs in the1960s,and Matsusaka~1993!and Hubbard and Palia ~1999!find positive returns to announcements of diversifying acquisitions in the1960s and 1970s during the conglomerate merger wave.2Also see Billett and Mauer~1997!,Denis and Thothadri~1999!,Gertner,Scharfstein,and Stein~1994!,Milbourn and Thakor~1996!,and Harris and Raviv~1996,1997!for other recent papers on the costs,benefits,and workings of internal capital markets.The Cost of Diversity37 resources~e.g.,see Stulz~1990!and Matsusaka and Nanda~1997!!.Though we believe that agency theories could explain generic overinvestment—for example,the decision to diversify could be viewed as an attempt by the CEO to entrench herself~e.g.,Shleifer and Vishny~1989!!—it is more difficult to see how these theories could explain the internal misallocation of funds;the CEO should exploit all potential sources of value inside the firm,skimming her agency rents only from the overall pie.Inf luence cost models are a third class of models that attempt to explain the decisions of diversified firms.In Meyer,Milgrom,and Roberts~1992!, managers of divisions that have a bleak future have an incentive to attempt to inf luence the top management of the firm to channel resources in their direction.Of course,in the spirit of inf luence cost models,top management sees through these lobbying efforts.Thus,no resources are,in fact,misal-located to the divisions,though costs are incurred in lobbying activities.As a result,it is again hard to explain the evidence on misallocation with these models.3Since existing theories need substantial embellishment to explain the mis-allocation of funds in diversified firms and the cross-sectional variation in value,Occam’s Razor suggests a different approach.We develop a model of capital allocation under two basic assumptions.First,headquarters has lim-ited power over its divisions:it can redistribute resources ex ante,but it cannot commit to a future distribution of surplus.Second,surplus is distrib-uted among divisions through negotiations,and divisions can affect the share of surplus they receive through their choice of investment.4Questions of how the power to take decisions,or capture surplus,is distributed within the firm then become central to determining whether the firm does better or worse than the market.A brief description of our model may help fix ideas.We assume that the diversified firm consists of two divisions,each led by a divisional manager. Each manager starts with an endowment of resources that the headquarters can either transfer to the other division or leave in place.The retained re-sources can be invested in one of two projects:an“efficient”investment and a“defensive”investment.The former is the optimal investment for the firm in a world where all contracts can be perfectly enforced.The latter offers lower returns,but protects the investing division better against poaching by the other division.53Hard,though not impossible.The prospect of enhanced inf luence costs can lead to changes, ex ante,in real decisions like allocations or organizational structure.These ideas have been separately explored in Fulghieri and Hodrick~1997!,Scharfstein and Stein~1997!,and Wulf ~1997!.As we will argue later,the precise nature of the misallocation we document is hard to reconcile with inf luence cost models.4Our model is best characterized as a model of power-seeking,and is most related to papers by Shleifer and Vishny~1989!,Skaperdas~1992!,Hirshleifer~1995!,and Rajan and Zingales ~2000!.5That managers have a choice between investments that alter their power is well recognized in the literature;see Shleifer and Vishny~1989!and Stole and Zwiebel~1996!.38The Journal of FinanceDivisional managers have autonomy in choosing investments and are self interested.Even though the efficient investment maximizes firm value, a divisional manager may prefer the defensive investment that would ben-efit her more directly,especially when her resources and opportunities are much better than the other division’s.The reason is quite simple.Once the divisional manager makes the unprotected,albeit efficient,investment,she will have to share some of the surplus created with the other division.Of course,if the other division also makes the efficient investment,our man-ager will get a piece of the surplus created by the other division.If the surplus created by the other division is not too small relative to what she is giving up,the divisional manager will prefer the efficient investment. Thus appropriate incentives are created for both divisions only when they do not differ too much in the surplus—which is the product of resources and opportunities—they create.Diversity in resources and opportunities is costly for investment incentives.Clearly,the investment distortions would not arise if headquarters could design precise rules to share ex post surplus.In practice,sharing rules are likely to be determined by factors other than considerations of ex ante optimality—such as the ex post bargaining power of the divisions. Although headquarters cannot contract on how divisions will share the surplus ex post,it can transfer funds ex ante.Some transfers will certainly be made because one division has better opportunities than the other.If stand-alone divisions face imperfect capital markets and cannot borrow as much as they need,the transfers to deserving divisions~“winner-picking”in Stein’s~1997!felicitous language!is one way the diversified firm adds value.But transfers will also be made so as to improve the incentives to un-dertake the efficient investment.Since incentives are distorted away from the optimal because of diversity~of opportunities and resources!,transfers will be made in a direction that makes divisions less diverse—from divi-sions that are large and have good opportunities to divisions that are small and have poor investment opportunities.Thus,the diversified firm may misallocate some funds at the margin~relative to the first-best!to prevent greater average investment distortions.The more diverse a firm’s divisions are,the greater the need to reallocate funds in this way.Thus corporate redistribution may be a rational second-best attempt to head off a third-best outcome.We are not the first to argue that politics inf luences investment decisions in firms.6However,our simple model of internal capital allocation based on power considerations has the advantage of identifying a clear proxy for what6For example,Chandler~1966,p.166!describes the capital budgeting process at General Motors under Durand’s management in the following way:“When one of them@Division Man-agers#had a project why he would vote for his fellow members;if they would vote for his project,he would vote for theirs.It was a sort of horse trading.”The Cost of Diversity39 drives inefficient allocations:the diversity of investment opportunities and resources among the divisions of the firm.Moreover,it offers detailed test-able implications on the direction of f lows between divisions.We test the implications of the theory for a panel of diversified U.S.firms during the period1980to1993using the segment data on COMPUSTAT. Our theory suggests that whether a segment receives or makes transfers in a diversified firm depends not so much on its opportunities~proxied for by Tobin’s q)as on its size-weighted opportunities,and the way these are dis-persed across segments in that firm.We show that our theory has a greater ability to predict internal capital allocation than the Efficient Internal Mar-ket theory.Moreover,allocations toward the relatively low q segments of a diversified firm,on average,outweigh allocations to its relatively high q segments as the dispersion in weighted opportunities~which we call diver-sity!increases.Of course,this may simply ref lect the channeling of funds to low q seg-ments that are inefficiently being rationed by the market.For this reason, we test the relationship between diversity and value.We find the greater the diversity,the lower the diversified firm’s value relative to a portfolio of single-segment firms.This effect persists even after we correct for the ex-tent to which the diversified firm is focused in specific industries,so our measure of diversity captures something different from traditional measures of diversification.The empirical results,taken together,provide striking evidence that diver-sity in investment opportunities between segments within firms leads to dis-torted investment allocations and hence value differences between diversified firms.Diversified firms can trade at a premium if their diversity is low.As a case in point,General Electric,perhaps the most admired U.S.conglomerate, is at the8th percentile of our sample over the entire sample period in terms of diversity,and at the75th percentile in terms of relative value.More generally,we believe that our evidence sheds light on how decisions within firms can differ from decisions made in markets.A firm is a collec-tion of commonly held,and mutually specialized critical resources.7Though the common control of key resources gives certain agents in the firm the power to shape transactions that would otherwise not be possible in the marketplace~such as the transfer of resources!,the absence of a clear de-marcation to property rights within the firm can create inefficient power struggles~also see Rajan and Zingales~1998a!!.Thus,our finding that a measure of the distortions created by power~i.e.,diversity!relates to the discount diversified firms trade at suggests,first,that the use of power may indeed explain why transactions within firms are different from transac-tions in markets and,second,that neither hierarchies nor markets need dominate.Coase’s emphasis on power is far from empty!7See Kumar,Rajan,and Zingales~1999!for a more detailed exposition of Critical Resource theories of the firm.40The Journal of FinanceThe rest of the paper is organized as follows.In Section I we present the framework of our simple stripped-down model.In Section II we derive some testable implications from the model.Section III describes the sample,the tests,and the results.Conclusions follow.I.The ModelWe want to analyze resource allocation in diversified firms.Therefore,we focus on firms operating in different lines of business.For the purposes of our analysis,the distinction between vertically integrated divisions and un-related divisions is unimportant.In fact,the distortions we want to study may arise whenever different organizational units operate within the same hierarchy,so long as at least one dimension of their operations~e.g.,raising and allocating resources!is integrated.Our model,therefore,does not apply to a leveraged buyout fund,where each subunit is a firm that operates sep-arately from the other subunits on every dimension,including financing~see Jensen~1989!!.A.TimingConsider a world with four dates,0,1,2,and3.A firm is composed of two divisions,A and B,each of which is headed by a manager who,for simplicity, will be thought of as representing the entire human capital of her division. Each manager wants to maximize the surplus that accrues to her division at date2.We assume,by contrast,that headquarters maximizes the surplus created by the entire firm.8The two divisions interact on three dimensions.At date0,the headquar-ters can reallocate resources between the two divisions.At date1,divisions choose investments.The type of investment chosen affects the“property right”a division has on the cash f low produced because,depending on it,a division may have the opportunity to poach on the surplus created by the other division.At date2,the divisions split the total surplus according to their relative power.Everything is predetermined at date3:Production takes place and surplus is shared according to the date2contract.So date 3is only for completeness.To summarize,the sequence of events is pre-sented in Figure1.We now detail the interactions on the previous three dates.8In Rajan,Servaes,and Zingales~1997!,we model this more precisely by assuming that headquarters controls the physical assets of the firm~which are crucial for production!,and thus gets a share of the total surplus in bargaining with the divisions.If we assume that headquarters first bargains with the divisions after which the divisions further subdivide the surplus,headquarters will always get a constant share of the surplus,and hence has an in-centive to maximize the surplus created by the firm.The Cost of Diversity41Figure1.Timing of the events.B.Resources and TransfersEach division j starts with an initial endowment of resources,l0j,that can be invested.We assume that these resources include any potential borrow-ing from outside.The initial level of resources could also be thought of as the resources the division would be able to invest if it were a stand-alone firm. The quantity of these resources are assumed to be limited despite unlimited investment opportunities~see later!because external capital markets are imperfect.For simplicity,we assume that headquarters can transfer all of a divi-sion’s resources to the other,though we will see that in equilibrium it will not always choose to do so.The total resources division A has available for investment at date1is then l1Aϭl0AϪt,and division B has l1Bϭl0Bϩt.C.InvestmentEach division can allocate its date1resources,l1j,to one of two kinds of investments.One investment is technologically efficient in that it maximizes returns;however,it leaves the surplus exposed to potential expropriation by the other division.Alternatively,the division could make a defensive invest-ment,which protects the surplus created at the cost of lower returns. Some examples are useful to fix ideas.The protective investment could be overly specialized~as in Shleifer and Vishny~1989!!so that only the division knows how to run it.This prevents the project from ever being turned over to the other division.Moreover,the durable resources employed on the project, such as employees,would also become so specialized that they could never be poached by the other division.Of course,the excess specialization would reduce the returns of such a project relative to a more general investment that could be subject to interference by the other division.The protective investment could reduce a division’s dependence on the other division.One of the authors once worked in a commercial bank with three subunits.One subunit had leased dedicated long-distance telephone lines to connect its representatives in each of the bank’s branches.The lines were barely used and since the subunits shared space in the branches,it would have been a simple matter for the other subunits to share access to the lines and also connect their representatives.Rather than spending resources to42The Journal of Financeaugment the common usage of the existing lines~efficient!,the other sub-units decided to lease their own lines~protective!because they felt their dependence on the first subunit would compromise their ability to bargain over issues such as transfer prices for funds.The protective investment could be one that stays within the well-defined turf of a division,even though it is efficient for the division to venture out.Bertelsmann,the German conglomerate,had separate divi-sions for publishing and new media.The development of book sales through the Internet provided a wonderful opportunity to the book division,as well as a substantial threat to its existing business.Yet the book division ig-nored the opportunity,preferring to focus on book sales through traditional channels,which were clearly its protected turf,and ignoring the efficient Internet investment that could well become part of the new media divi-sion’s empire.9Let the gross return at date3per dollar invested in efficient investment at date1be a j.Since defensive investments are wasteful of resources,the gross return to them is then a jϪg,where g is a positive quantity.To tie our hands,we assume that there are no savings or diseconomies from joint production.We only assume that if two divisions are under common ownership,resources can be reshuff led between the two.As we shall show,this reshuff ling has a positive side~the possibility that re-sources can be reallocated to their highest value use as in Stein~1997!! and a negative side~that a division may distort its investment in order to obtain“property rights”in the surplus it creates!.Thus,both the benefits and costs of a diversified firm spring from the same source:the use of power rather than arm’s length contracts to govern transactions within the firm.D.ContractibilityAccounting controls can ensure that the funds transferred to a division are invested,but a division~and the headquarters!cannot contract on the type of investment that is to be made by the other division.Myers~1977!has a detailed discussion as to why it is difficult to contract on investment;the nature of the“right”physical investment is based on the division’s judgment about the state,which is hard to specify ex ante or verify ex post.Also,much of the investment may not be in physical assets but may enhance the divi-sion’s human capital which,again,is hard to contract upon.We also make another assumption that is standard in the incomplete con-tract literature~see Grossman and Hart~1986!!:The surplus that is to be produced at the final date cannot be contracted on before date2because the state will be realized then and the state-contingent surplus that will be pro-9See the survey in The Economist,November211998,p.10.The Cost of Diversity43 duced may be hard to specify up front.As shown by Hart and Moore~1999!, this incompleteness of long-term contracts can be rationalized in a world where all contracts can be renegotiated.At date2,however,after the uncertainty about the state that will prevail is resolved,it is possible to strike deals,after bargaining,over the division of date3cash f low.Date3is separated from date2only for expositional convenience,and these dates could be thought of as very close together so that the deals could be thought of as enforceable spot deals.E.Date2PayoffsA divisional manager who chooses the defensive investment ensures that the surplus his division creates is well protected against any actions by the other division.Moreover,since the investment does not consume all his time and resources,he can attempt to poach on the surplus created by the other division if the other division made the efficient,albeit unprotected, investment.Thus,if each divisional manager chooses the defensive investment,there is no room for power seeking inside the firm and each division will retain its product—that is,~a jϪg!l1j.If one divisional manager,say A,chooses the defensive investment and B does not,then A will have the opportunity of trying to grab some of B’s surplus.If A attempts such a grab,B can defend himself,but at substan-tially greater cost than if he had chosen the defensive investment up front. Specifically,a fraction of the surplus produced by B is dissipated in ex post jockeying for advantage.The payoff B gets is then~a BϪu!l1B where u.g. For simplicity,we assume that the surplus division A grabs is almost fully matched by its cost of poaching,and it gets~a AϪg!l1Aϩe where e is a small number.Finally,if both divisional managers choose the technologically efficient investment,both are fully involved in productive activity,and neither has the time to poach.Of course,knowing this,neither bothers to defend.Thus, when both divisions choose the efficient investment,dissipation will be avoided and we assume the total surplus~a A l1Aϩa B l1B!is split equally between the two divisions.10The assumption of equal split is not crucial.We will discuss the robustness of the result to changes in this assumption in Section II.D.1110That headquarters does not get any of the surplus is only for simplicity.None of our results would be changed if headquarters gets a constant fraction of the surplus because of its control of the firm’s physical assets~see footnote7!.11It is possible to formalize all this.For example,let poaching consume real resources.Skaper-das~1992!shows that when the opportunity cost of poaching is high,cooperation~i.e.,no poach-ing!is an equilibrium.When division A makes the defensive investment and division B does not,A’s opportunity cost of poaching is low since the defensive investment has low returns.By contrast,when A makes the efficient investment,the opportunity cost of poaching is high,and both divisions would be content not to poach.44The Journal of FinanceF.First BestIdeally,all the resources should be transferred to the division with the highest return a j.12This division should allocate all the resources to the efficient investment.As we will show,resources may not all be transferred to the division with the highest use for them because such a transfer can destroy the division’s incentive to make the efficient investment.In what follows,we will examine how transfers and allocations are distorted away from the first-best.II.Equilibrium ImplicationsGiven the anticipated payoffs from date2bargaining,at date1division j ~jʦA,B!has the incentive to make the efficient investment if division k is expected to do so,and1Ϫ@a j l1jϩa k l1k#Ն~a1jϪg!l1j.~1!2Since a similar inequality should hold for division k also,both divisions have the requisite incentives if1Ϫ@a j l1jϩa k l1k#ՆMax@~a1jϪg!l1j,~a1kϪg!l1k#.~2!2It is easily checked that this is a necessary and sufficient condition for the efficient investment to be an equilibrium at date1.Now let us effect a sim-ple change of variables so that b jϭa jϪg.Furthermore,without loss of generality,let b j l1jՆb k l1k.Then the right-hand side of inequality~2!sim-plifies to b j l1j and the whole expression can be rewritten asg~l1jϩl1k!Ն~b j l1jϪb k l1k!.~3!For a fixed total amount of resources,~l1Aϩl1B!,this inequality implies that the product of resources and potential returns cannot be too diverse across divisions.The intuition is straightforward.Division j~which is the division that can contribute the most to surplus in the following period!will choose the effi-cient investment only if division k contributes enough surplus to make it worthwhile.Division k will not be able to contribute enough if its resource-weighted opportunities,b k l1k,are small relative to j’s.If so,division j will not make the efficient investment,and neither will k.Therefore,too much diversity in potential contributions to the common pool will lead to a break-12Of course,in practice,returns will not be constant with scale.Some resources will be retained by the division with lower a j so as to undertake essential investments such as maintenance.。

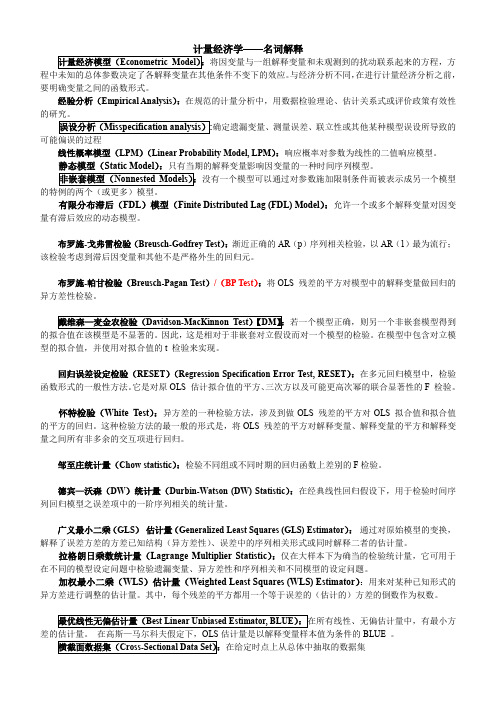

计量经济学(重要名词解释)

——名词解释将因变量与一组解释变量和未观测到的扰动联系起来的方程,方程中未知的总体参数决定了各解释变量在其他条件不变下的效应。

与经济分析不同,在进行计量经济分析之前,要明确变量之间的函数形式。

经验分析(Empirical Analysis):在规范的计量分析中,用数据检验理论、估计关系式或评价政策有效性的研究。

确定遗漏变量、测量误差、联立性或其他某种模型误设所导致的可能偏误的过程线性概率模型(LPM)(Linear Probability Model, LPM):响应概率对参数为线性的二值响应模型。

没有一个模型可以通过对参数施加限制条件而被表示成另一个模型的特例的两个(或更多)模型。

有限分布滞后(FDL)模型(Finite Distributed Lag (FDL) Model):允许一个或多个解释变量对因变量有滞后效应的动态模型。

布罗施-戈弗雷检验(Breusch-Godfrey Test):渐近正确的AR(p)序列相关检验,以AR(1)最为流行;该检验考虑到滞后因变量和其他不是严格外生的回归元。

布罗施-帕甘检验(Breusch-Pagan Test)/(BP Test):将OLS 残差的平方对模型中的解释变量做回归的异方差性检验。

若一个模型正确,则另一个非嵌套模型得到的拟合值在该模型是不显著的。

因此,这是相对于非嵌套对立假设而对一个模型的检验。

在模型中包含对立模型的拟合值,并使用对拟合值的t 检验来实现。

回归误差设定检验(RESET)(Regression Specification Error Test, RESET):在多元回归模型中,检验函数形式的一般性方法。

它是对原OLS 估计拟合值的平方、三次方以及可能更高次幂的联合显著性的F 检验。

怀特检验(White Test):异方差的一种检验方法,涉及到做OLS 残差的平方对OLS 拟合值和拟合值的平方的回归。

这种检验方法的最一般的形式是,将OLS 残差的平方对解释变量、解释变量的平方和解释变量之间所有非多余的交互项进行回归。

15预期报酬率和资本成本

权益成本的计算

假设BW现在的普通股价格每股$64.80, 每股股利

$3, 同时每年股利的增长速度为 8%并持续下去.

ke ke ke

= ( D1 / P0 ) + g = ($3(1.08) / $64.80) + 0.08 = 0.05 + 0.08 = 0.13 or 13%

第6页,共58页。

企业的综合资本成本

资本成本 是企业各种不同融资来源 的必要报酬率.

企业的资本成本是一个个独立资本成本的 加权平均 ---综合资本成本。

15.7

Van Horne and Wachowicz, Fundamentals of Financial Management, 13th edition. © Pearson Education Limited 2009. Created by Gregory Kuhlemeyer.

第4页,共58页。

价值的创造

如果一个项目的收益超过了金融市场 所要求的收益,就有超额收益。

有超额收益的项目—表现为有正 的NPV---可以带来公司股票价格上升 。

即:投资项目产生价值的创造。

15.5

Van Horne and Wachowicz, Fundamentals of Financial Management, 13th edition. © Pearson Education Limited 2009. Created by Gregory Kuhlemeyer.

第5页,共58页。

价值创造的主要来源

行业吸引力

产品周期的 增长阶段

竞争性进入 的障碍

其他保护措施

例如专利、 临时的垄断权、

寡头定价

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Estimating the foreclosure effect of exclusive dealing:Evidence from the entry of specialty beer producers ☆Chia-Wen ChenDepartment of Economics,National Taipei University,151University Road,San Shia District,New Taipei City 23741,Taiwana b s t r a c ta r t i c l e i n f o Article history:Received 7June 2012Received in revised form 22July 2014Accepted 22July 2014Available online 6August 2014JEL classi fication:L42L12K21Keywords:Exclusive dealing Foreclosure EntryBeer industryThis paper estimates an entry model to study the effect of exclusive dealing between Anheuser Busch and its distributors on rival brewers'entry decisions and consumer surplus.The entry model accounts for post-entry de-mand conditions and strategic spillover effects.I recover a brewer's fixed costs using a two-step estimator and find spillover effects on brewers'entry decisions.I find that a brewer has higher fixed costs at locations where Anheuser Busch employ exclusive distributors,but the effect is only statistically signi ficant in certain local areas.The estimates also show that a brewer is less likely to enter a location that is farther from its brewery,has lower expected demand,or is smaller in store size.I implement counterfactual experiments to study the effect of banning exclusive contracts between Anheuser Busch and its distributors.The results show that the welfare improvement associated with banning such contracts is very small.©2014Elsevier B.V.All rights reserved.1.IntroductionAn exclusive dealing contract is a vertical agreement between a manufacturer and a distributor that forbids the distributor from pro-moting other manufacturers'products.Such a contract is controversial in competition policy,because of the potential foreclosure effects.For example,in 1997Anheuser Busch launched an incentive program that provided discounts and other bene fits to distributors that went ex-clusively with Anheuser Busch.At that time,many microbreweries complained they were being dropped by distributors due to this practice.The theory suggests that exclusive dealing can be ef ficiency-enhancing,because it encourages investment in manufacturer –distributor relationships,but it also suggests that exclusive dealing can be anticompetitive due to raising rivals'entry costs.In practice,theextent to which exclusive dealing enhances investments in a vertical relationship or dampens competition remains an empirical question to be explored.1This paper examines whether exclusive contracts between a dominant firm and its distributors have a foreclosure effect.More importantly,by quantifying the magnitude of diverted sales from a potential foreclosed firm to the dominant firm and the changes in consumer surplus,this paper looks at the motivations behind exclusive dealing and the welfare implications from banning such contracts.The empirical setting is the U.S.beer industry.Aside from mainstream mass producers (Anheuser Busch,Miller,and Coors),many entrepre-neurs entered this industry during the microbrew movement that took off in the 1980s.Most microbreweries founded during this eraInternational Journal of Industrial Organization 37(2014)47–64☆I would like to thank Christopher Knittel,as well as A.Colin Cameron,Joonsuk Lee,Julie Holland Mortimer,David Rapson,Victor Stango,and three anonymous referees for their valuable comments.I would also like to thank the seminar participants at the University of California at Davis,University of Connecticut,University of Leicester,National Taipei University,Academia Sinica,and Shanghai University of Finance and Economics for many helpful comments.I am particularly grateful to John Pauley and The Nielsen Company for allowing me access to the data used in this paper.I also thank James Arndorfer for sharing his industry insights.E-mail address:cwzchen@.tw .1The foreclosure argument led the courts to condemn exclusive dealing contracts be-tween dominant firms and their distributors after the enactment of the Clayton Act in 1914.However,the Chicago school's defense of exclusive dealing started to prevail in the 1970s,and since then the courts have emphasized a rule of reason approach to such provisions.For earlier cases where the courts were against exclusive dealing,see Standard Fashion Co.v.Magrane-Houston Co.,258U.S.346(1922)and Standard Oil Co.of California et al.v.United States,337U.S.293(1949).For decisions favoring exclusive contracts,see Tampa Electric Co.v.Nashville Coal Co.,365U.S.320(1961)and Beltone Electronics Corp.,100F.T.C.68(1982).In Europe,a recent practice by Intel,which provided rebates and cash bene fits to manufacturers and retailers in exchange for purchasing most of their products from Intel,was found to be anticompetitive by the European Commission and resulted in a €1.06billion fine in2009./10.1016/j.ijindorg.2014.07.0070167-7187/©2014Elsevier B.V.All rightsreserved.Contents lists available at ScienceDirectInternational Journal of Industrial Organizationj o u r n a l h om e p a g e :w w w.e l s e v i e r.c o m /l o c a t e /i j i owere clustered on the West Coast along the“Interstate5corridor”from San Francisco to Seattle.2The boom ended with a shakeout in the late 1990s.One particular factor that may have contributed to the shakeout is Anheuser Busch's exclusive dealing program beginning in1997, which eliminated one of the most dominant distribution vehicles from its rivals'choice set.Because there were other distributors available in the market,the extent of the foreclosure effect requires further exami-nation.The main task of this paper is to model each specialty beer producer's entry decision for a location in a setting where theirfixed entry costs may be affected by(1)exclusive dealing between Anheuser Busch and its distributors and(2)spillover effects resulting from other entrepreneurs'entry decisions.I then take the estimates from the anal-ysis to perform counterfactual experiments.This paper contributes to the literature and policy discussion of exclu-sive contracts in several ways.First,even though the theoretical literature on exclusive dealing has presented many fruitful insights,the effect of exclusive dealing is still ambiguous.Empirically,the data availability problem and the fact that a distributor's enrollment into an exclusive pro-gram and a brewer's entry decision are both endogenous to unobserved market conditions have resulted in few empirical studies in this area. For example,all things being equal,a distributor that serves an area with a higher demand for domestic products is more likely to enroll into such a program compared to another one that serves an area with a lower demand for domestic products.In addition,demand conditions directly affect domestic specialty beer producers'entry decisions into a market and result in an endogeneity problem.To this end,I collect entry data of specialty beer producers and address the endogeneity problem by controlling for consumers'demand for beer products in a setting of dif-ferentiated products,which is different from most previous empirical works in this area(Rojas,2010;Sass,2005).3I show that without account-ing for the endogeneity of the exclusivity decision,estimates of exclusive dealing on the probability of entry are biased upwards.4Another major contribution of this paper is to take advantage of demand-side estimates to conduct counterfactual experiments.I study whether a foreclosure-based motivation alone can rationalize Anheuser Busch's continuing support for exclusive contracts,as well as to what extent the consumer surplus would increase if such contracts were pared to a previous work(Asker,2005)that tests the fore-closure hypothesis and focuses mainly on the supply side,this paper quantifies the potential benefits on consumer surplus from banning exclusive dealing by removing the foreclosure effect and expanding consumers'choice sets,which is not directly addressed in the previous literature(Asker,2005;Chen,2013;Rojas,2010;Sass,2005).5From an antitrust policy's perspective,such an estimate of consumer surplus is crucial in evaluating vertical restraints in the marketplace.I show that even when efficiency gains from exclusive contracts are not acknowledged and even when exclusive contracts have raised rivals' entry costs in some local areas,if the antitrust agency adopts a consum-er surplus standard(as it currently does)rather than a total welfare standard to evaluate vertical restraints,then policy intervention in banning such contracts may be ineffectual.6Inferences about the foreclosure effect through direct comparisons of entry patterns can suffer from omitted variable bias,because post-entry market outcomes may differ across locations andfirms.Thus,I estimate the demand for beer to construct counterfactual expected post-entry sales.With the panel structure of the dataset,I can control for invariant brand and locationfixed effects.I estimate the demand system using a nested logit model.The model allows the substitution patterns to vary based on product segments(e.g.,country origin or style of beer)and has more reasonable substitution patterns than a simple logit model.7This paper also builds on empirical studies that estimate static entry games.Bresnahan and Reiss(1991)show how to estimate an equilibri-um model of entry for symmetricfirms with data on market character-istics and the number offirms.Similar to Bresnahan and Reiss(1991),I allow both total variable profits andfixed costs to depend on the num-ber of brewers.Moreover,given that I observe a pool of global potential entrants,along with their actual sales and entry patterns,my model al-lows heterogeneous brewers to produce differentiated products with differentfixed costs.8Following recent developments in estimating strategic games (Augereau et al.,2006;Bajari et al.,2010;Ellickson and Misra,2008; Seim,2006;Sweeting,2009),I model the entry behavior of specialty beer producers using an incomplete information framework that helps to incorporate a large number of players in the game.In this setup,a brewer's entry decision depends on the expected market profitability and private information.I estimate the model following a two-step esti-mation procedure,similar to that of Ellickson and Misra(2008)and Bajari et al.(2010),and use the demand estimates to control for post-entry sales.The estimation is done in three steps.Thefirst step esti-mates the equilibrium entry probabilities implied by the model.The second step estimates the demand for ing the demand estimates and the beliefs about rivals'entry probabilities,I construct expected post-entry sales.The third step then plugs the above estimates into the likelihood function to recover a brewer'sfixed costs.Economic theories vary in their explanations of exclusive contracts. Traditionally,the Chicago school has argued that exclusive dealing can-not be used as a device for monopolization(Bork,1978;Posner,1976): if the sole purpose of exclusive contacts were to restrict competition, then downstream buyers would never sign them in thefirst place,be-cause doing so would only lower the potential total surplus.Incentive theories show that exclusive dealing enhances incentives for invest-ment when investments made by parties in a bilateral relationship have external effects on outside parties(Bernheim and Whinston, 1998;Besanko and Perry,1993;Klein and Murphy,1988;Martimort, 1996;Marvel,1982;Segal and Whinston,2000a).92Tremblay and Tremblay(2005)provide an excellent treatment on the history of the microbrewery movement.Most specialty beer producers remain microbreweries,but some of them(Boston Beer Company and Sierra Nevada Brewing Company)have grown successfully and are no longer microbreweries.3Sass(2005)studies a cross-sectional survey of381beer distributors in1997andfinds that exclusive dealers on average generate higher prices and larger sales for their sup-pliers,which is more consistent with the incentive-based theory.Rojas(2010)looks at a scanner dataset of63metropolitan areas from1988to1992and uses average exclusive dealing intensity that a brand has in other cities in the same region as an instrumental var-iable for the exclusive dealing decision.Hefinds that exclusive dealing increases con-sumers'willingness to pay and provides a cost advantage forfirms.4Another possible source of endogeneity is the extent to which a distributor can effec-tively increase local demand over its products due to legal restrictions.For example,Sass (2005)considers state laws banning outdoor advertising of malt beverages and argues that these laws influence participation in the exclusive program across states.In this pa-per,I do not address this kind of endogeneity because this paper's empirical setting is en-tirely in Northern California,and so the legal environment is more homogeneous than the one considered in Sass(2005).5When products are differentiated,the introduction of new products with quality im-provements can improve consumer surplus significantly,and counterfactual analysis based solely on a single dimension(the average price or an aggregate sales measure) may underestimate the foreclosure effects on consumer welfare.6I thank anonymous referees for directing me to a consumer surplus approach and for pointing out that if Anheuser Busch adopts an exclusive contract for efficiency reasons, then equilibrium prices are likely to be lower.If this is the case,one can interpret the result in this paper as that the collateral damage in blocking some craft breweries from operating is small.7The nested logit model has wide applications in estimating transportation and energy demand and is also applied to other industries such as automobiles,movies,home videos, and banking(Chiou,2008;Dick,2008;Einav,2007;Goldberg,1995).In particular,Ho et al. (2012)estimate a nested logit model in the context of empirical analyses of vertical contracts.8Berry(1992)first estimates a model of entry in the airline industry that allows forfirm heterogeneity infixed costs.This present paper exploits data on beer prices and sales and allows afirm's variable profits to also depend on rivals'identities.9In fact,Segal and Whinston(2000a)show that restricting a distributor's external trad-ing opportunities increases the level of investment when a distributor's investment has a substitutable effect,i.e.,investment devoted to one brand hurts the value of other brands in the same distribution network;or when a manufacturer's investment has a comple-mentary(positive spillover)effect.48 C.-W.Chen/International Journal of Industrial Organization37(2014)47–64Anticompetitive arguments focus on the foreclosure effect of exclu-sive dealing.In this literature,manufacturers either sign exclusive con-tracts with lower-cost buyers,trying to raise their rivals'costs,or with a large number of buyers,trying to foreclose the market directly when facing minimum economies of scale.10Segal and Whinston(2000b) point out that whether manufacturers can successfully carry out the above“naked exclusion”scheme depends on how well they are able to exploit the coordination problem faced by buyers.11Most previous studies of exclusive dealing in the U.S.beer industry find efficiency reasons more consistent with empirical evidence (Chen,2013;Rojas,2010;Sass,2005).Specifically,using variation gen-erated from distribution contract changes,Chen(2013)finds that a brand's market share is higher when the brand's distributor has fewer external trading opportunities.12Nevertheless,most of the above pa-pers assume that products are homogeneous and do not speak to the effect of exclusivity on consumer surplus and its foreclosure effect when products are differentiated,which is the main focus of this paper.There is a growing empirical literature on estimating industry models with vertical restraints(in particular,Asker,2005;Ho et al., 2012;Crawford and Yurukoglu,2012;Lee,2013;Conlon and Mortimer,2013;Sinkinson,2014).13More closely related to my paper is Asker(2005),who also studies exclusive contracts in the beer indus-try and takes a structural approach in a differentiated product frame-work to recover the costs incurred and the promotional efforts made of distributors in exclusive and less exclusive markets.Asker(2005)finds that distributors in less exclusive markets are not more efficient than distributors in exclusive markets and rejects the foreclosure hy-pothesis.Even though the main focus of Asker(2005)is on the supply side,the beer products in his analysis are mainly produced by domestic or foreign mass-producers,which are unlikely to be forced out of the market due to exclusive dealing in thefirst place.By contrast,the struc-tural approach in this paper allows me to directly look at the entry patterns offirms that are more likely to be foreclosed,and more impor-tantly,to estimate the effect of banning exclusive dealing on consumer surplus.Ifind that the demand for beer is elastic and that the price of a spe-cialty beer product is lower at locations closer to its producer's estab-lishment.Controlling for prices,I alsofind that consumers enjoy a product more if it is locally brewed.Thesefindings explain why most specialty beer producers are not present in every location.I then take the demand estimates to the model of entry.When strategic interac-tions are not allowed in the model,exclusive dealing shows no impact on a specialty beer producer's entry decision.Once strategic interactions are allowed,Ifind that in some local markets,a store with an Anheuser Busch exclusive distributor is associated with a reduction of6per-centage points(21%)in a specialty beer producer's entry probability, suggesting a foreclosure effect due to exclusive dealing.I also show that a specialty beer producer has lowerfixed costs at a location where the number of rivals is larger.The result implies thatfirms can benefit from clustering their strategic decisions,which is similar to the findings in previous studies that estimate strategic effects,such as Ellickson and Misra(2008),Sweeting(2009),Bajari et al.(2010),and Vitorino(2012).Finally,I use demand estimates to carry out counterfactual experi-ments that remove exclusive dealing.The magnitude of the foreclosure effect is too small to claim that Anheuser Busch's exclusive dealing pro-gram is entirely driven by a foreclosure motivation.Thus,the decrease in entry probabilities in some local markets is more likely to be a side-effect of exclusive contracts.I do notfind much change in welfare due to banning exclusive dealing contracts between Anheuser Busch and its distributors.In fact,I show that adding more specialty brands does not provide much benefit to consumers:when exclusive dealing is re-moved in a market,the change in aggregate consumer welfare is only $15per store per quarter.This result,complemented by thefindings from Sass(2005),Rojas(2010),and Chen(2013)supporting the effi-ciency motives behind exclusive dealing,reinforces that banning exclu-sive contracts in the current beer industry is hardly welfare improving.This paper proceeds as follows.I begin by examining the industry and the data.I then describe the model of demand and entry behavior. Next,I discuss the corresponding estimating procedures and identifica-tion issues.Finally,I present the empirical results and discuss the impli-cations and potential future research.2.Industry backgroundThe U.S.beer industry has nearly3000brewing establishments and accounts for approximately$100billion in annual sales.14During the sample period of the data(2006–2008),Anheuser Busch,Miller,and Coors collectively held nearly80%of the market,with Anheuser Busch being the most dominantfirm in the industry(50%market share).15 Since the end of Prohibition,the industry has been heavily regulated by state laws,under which vertical integration between manufacturers, distributors,and retailers is not allowed.The vertically-separated “three-tier system”(manufacturing,distribution,and retailing)is one of the main features of the beer industry.16Beer manufacturers rely on distributors to transport and rotate their products in local markets so as to guarantee product availability and freshness.Distributors are also responsible for point-of-sale promotion-al activities.Building and maintaining good relationships with distribu-tors to receive adequate promotional support are thus vital to a brewer's success,especially when it comes to entering a new market or launching a new advertising campaign.While a brewery would prefer its distribu-tors to be exclusive and to devote as much promotion efforts to its prod-ucts as possible,it may not be in the best interest of distributors to build a relationship with just one brewery.To maintain a stable cash stream and warehouse/route efficiency,a distributor is more likely to prefer having all the best-selling products in its brand portfolio.Conflicts of interest handling multiple brands from competing breweries at the same time often render lower promotional efforts than what would be10Salop and Scheffman(1983),Aghion and Bolton(1987),Rasmusen et al.(1991),and Bernheim and Whinston(1998)provide theoretical foreclosure arguments for exclusive dealing.For a recent theoretical treatment on vertical exclusion without an explicitly writ-ten exclusive contract,see Asker and Bar-Isaac(2014).11Simpson and Wickelgren(2007),Abito and Wright(2008),and Doganoglu and Wright(2010)also provide settings that allow exclusive dealing to achieve inefficient out-comes.Simpson and Wickelgren(2007)and Abito and Wright(2008)consider the casewhen buyers compete,and Doganoglu and Wright(2010)study exclusive contracts under the network effect.12Chen(2013)exploits a distribution deal between Anheuser Busch and InBev in2007 to study the effect of allowing more brands to have access to exclusive distribution net-works on brand level outcomes in Northern California.The result suggests InBev brands' market shares to be higher once they were allowed access to Anheuser Busch's exclusive distribution networks.In addition,other brands'market shares were lower when their distributor gained InBev products.The results are consistent with an incentive-based ex-planation forfirms preferring exclusive contracts.13For a thorough review of earlier empirical studies on vertical integration and vertical restraints,see Lafontaine and Slade(2007)and Lafontaine and Slade(2008).14Statistics are obtained from the Beer Institute website.15The industry has become even more concentrated after two mergers ler and Coors formed a joint venture.Anheuser Busch then merged with InBev,the biggest brewer in Europe.16The extent to which administrators regulate alcoholic beverages vary by state and in alcohol content.For beer,most states regulate private licensed retailers and distributors and adopt the three-tier system to restrict private ownership across different tiers.For wine and spirits,several so-called control states buy alcohol directly from manufacturers and act as monopolies in the wholesale and retail distribution tiers.For recent studies that examine possible welfare losses created by state regulations on alcoholic beverages,see Seim and Waldfogel(2013),Miravete et al.(2014),and Conlon and Rao(2014).49C.-W.Chen/International Journal of Industrial Organization37(2014)47–64considered optimal from a brewer's perspective.One of the main effi-ciency arguments for exclusive dealing is to create a loyal vertical rela-tionship and enhance a distributor's promotional investments.17 The beer industry is divided into three segments:domestic macro brands,imported brands,and specialty brands.The top three domestic mass-producers(Anheuser Busch,Miller,and Coors)focus on“regular domestic beer,”which are mainstream,lower-priced,light lager prod-ucts with large package size options.Imported brands include products (usually well-established ones)from foreign countries that are typically priced higher than domestic beer.The last category,domestic specialty brands,refers to domestic brands that emphasizeflavor and taste. According to Tremblay and Tremblay(2005),specialty beer producers emulate the business model of wineries in Northern California by pro-viding“boutique”products in small batches.They advocate the taste of“real beer”and encourage consumers to choose craft beer instead of beer that contains a high concentration of adjuncts and that lacksflavor. Sierra Nevada Brewing and Boston Beer Company are pioneers of the microbrewery movement during the1980s and are the most successful and nationally known companies in this segment.Mostfirms of specialty beer products enjoy a higher market share in geographic areas closer to their brewery,which is consistent with Bronnenberg et al.(2009).18Taking Sierra Nevada Brewing as an exam-ple,while it has a1%market share across all stores in the sample data,in Chico,California where its brewery is located,it has an average8%mar-ket share,putting it very close to Anheuser Busch's market share(9%in Chico,10%overall).Because Sierra Nevada is so successful in Chico,one might presume that it would be difficult for other microbreweries to break into store shelves there.However,the store that carries the most number of California specialty beer brands is also in Chico(39 brands per store on average,compared to24brands per store on aver-age).In this specific case,the entry of a rival microbrewery does not seem to create an entry barrier for otherfirms.In the empirical setting, a potential spillover effect is taken into account by allowingfixed costs to depend on the expected number of specialty beer producers.I also allow a“locally brewed”effect when I estimate consumers'demand for beer and consider the possibility that the distance between a grocery store and a product's brewery does affect the entry pattern of specialty beer producers.19In response to consumers'demand for specialty brands,top domes-tic mass-producers acquired several microbreweries and introduced their own brands of specialty beer in the late1990s.Anheuser Busch launched an incentive program during the late1990s,called“100per-cent share of mind.”The program provided discounts and other benefits for distributors in exchange for exclusivity with Anheuser Busch.As a result,many brands of other breweries were dropped by their Anheuser Busch distributors.Fig.1illustrates the impact of Anheuser Busch's ex-clusive dealing program in the three-tier system.In panel(a),specialty and imported products are allowed to share distribution networks with Anheuser Busch.It presents that Microbrewery1chooses to hire an Anheuser Busch distributor while Microbrewery2chooses to work with a Miller distributor.In panel(b),because the Anheuser Busch's dis-tributor is exclusive,all of the specialty and imported products that are not affiliated with Anheuser Busch are squeezed out of Anheuser Busch's distribution network and are crowded out to other distribution networks.Given that the other two leading brewers(Miller and Coors)rarely share distribution networks with Anheuser Busch,exclusive dealing cannot completely foreclose all distribution channels.Nevertheless, Anheuser Busch's exclusive dealing program may raise distribution costs for potential entrants by(1)enhancing rival distributors' bargaining power and by(2)forcing rival brewers to use less efficient distributors,thus reducing the likelihood of entry events.When most of the specialty and imported brands from competing breweries are crowded out into one distribution network,it enhances the distributor's bargaining power,which raises the entry barrier for a prospective mi-crobrewery into a new market.The crowding-out effect also intensifies incentive conflicts within a distribution network and may drive a distributor's promotional efforts of a brand further away from its opti-mal level.Finally,exclusive dealing may raise rivals'costs by forcing them to team up with smaller or less efficient distributors,because Anheuser Busch is the biggest competitor in the industry and its distri-bution networks are often viewed as a superior promotional vehicle due to its economies of scale in distribution.203.DataThe scanner dataset is provided by Nielsen.The dataset contains weekly price and sales data of the malt beverage category for all stores of a major grocery chain in Northern California from April2006to April2008.The original dataset comes at the Universal Product Code (UPC)level,which includes all sales records from all packaging options for all brands.I collapse the data to a quarterly brand level to take into account that some specialty brands may have very little(or even no) sales within a week or a month at the UPC level,and because the de-mand estimates from quarterly data are more likely to be suitable for policy analysis.21I search a product's website for information on the product's country of origin(domestic or foreign)and product owner-ship.For domestic specialty beer producers,I calculate the distance from a store to thefirm's nearest establishment(brewery or brewpub) using Google's map service.I also collect data on local contract rents at the zip code area level(“Gross Rent”)from Census2000as a further control for a location'sfixed costs.22The scanner dataset also includes a product category variable,made up of light,lager,ale,stout/porter,malt liquor,and non-alcoholic(alco-hol by volume of less than0.5%)beer,and three categories for alterna-tive malt beverage.Due to product similarity,I assign all alternative malt beverages to one style(alternative)and generate a new style specifically for domestic mainstream lager products.23In this way,I end up with eight different product styles.Data on Anheuser Busch exclusive distributors and their territories are from the California Beer and Beverage Distributors(CBBD)annual17Both manufacturers and distributors can make investments to enhance the value of their relationships.For example,a brewer can provide training programs on consumer be-havior for distributors.Similarly,a distributor can make efforts to secure better shelf space for its brewers.These investments not only increase the value of vertical relationships,butalso alter bargaining positions between the parties involved.In the former case,if training lessons are not specific to the relationship,then providing training lessons may hurt a brewer's ex-post bargaining power.On the contrary,if promotional efforts are tailored to a brewer,then such investments can hurt a distributor's ex-post bargaining power.Se-gal and Whinston(2000a)point out that when investments have external values and are not contractible,exclusivity can lead to a higher level of investments under some circum-stances.Therefore,an important motivation for exclusive dealing is to address the incen-tive problems in vertical relationships.18Bronnenberg et al.(2009)find an early entry advantage for several consumption goods,such as beer,coffee,and mayonnaise.The order of entry into a market is correlated with the rank of market share and perceived product quality.19The dummy variable“locally brewed”is set to be1when the brewery is located within a10-mile radius of a store.20Economies of scale are important in distribution.For example,Bump Williams,an IRS industry analyst,notes that“there's nobody better than these three networks(Anheuser Busch,Coors,and Miller).They can get these beers on shelves overnight.”See Kesmodel (2007).21I divide total revenue during a quarter by the number of six-packs sold during a quar-ter to calculate a product's price at the quarterly level.When products are storable goods, using temporary price promotions in weekly data to identify price elasticities can lead to an overestimation of price sensitivity(Hendel and Nevo,2006).22In Census2000,“Gross Rent”is defined to include“contract rent and estimated aver-age monthly cost of utilities(electricity,gas,water,and sewer)and fuels(oil,coal,kero-sene,wood,etc.)if these are paid by the renter.”23I define a product to be domestic mainstream lager if it is a lager product from one of the three biggest domestic competitors in the industry and has large package size options.50 C.-W.Chen/International Journal of Industrial Organization37(2014)47–64。