7A Survey of Corporate Governance

英语科技论文写作(一)

作业

• 结合你导师给定的课题查文献,列出相关 的文献:中、英文综述文章,中、英文博 士硕士论文、权威书籍、重要杂志文献。 • 查相关的专利、国内外目前开展的项目。

如何写科技学术论文

如何写英语科技学术论文

四川大学制造学院苏真伟教授

Brief CV of Zhenwei Su

• 2004-2009: Sichuan University, professor • 1997-2004: UK Universities visiting scholar,post-doc, research fellow • 1982-1997: Sichuan University, PhD, lecturer, associate professor • 1978-1982: Xian Jiaotong University, Mechanical Engineering Department • 1970-1978: Farmer or worker in Sichuan

如何了解我所在领域最具影响力 的研究人员?

如何选择合适的期刊发表论文?

当我们完成了某项研究之后,通常需要选 择一个合适的途径发表自己的研究成果, 那么怎样找到最合适自己研究领域的期刊 发表发表论文呢?您可以利用Web of Science数据库的检索结果分析功能 (Analyze)来解决这一问题。

眼睛犀利, 才能飞得高!

为什么要阅读文献

我们很多的时候,闷在实验室闭门 造车,实在不如稍抽出一点时间看看 文献。 我的大老板说,要想有成绩,别无 他法,只有读,读,大量的读文献, 尤其国外的。

主要的信息源

• 学术期刊(中文、英文) • 博士、硕士论文(中文、英文) • 学术网站(中文、英文) • 专利网站(中文、英文) • 书籍(中文、英文) 对低级研究人员:中文第一 对高级研究人员:英文第一

丹纳赫企业管治指南Danaher Corporate Governance Guidelines

DANAHER CORPORATIONCORPORATE GOVERNANCE GUIDELINESThe Board of Directors (the “Board”) of Danaher Corporation (the “Company”), acting on the recommendation of its Nominating and Governance Committee, has adopted these corporate governance principles (the "Guidelines") to promote the effective functioning of the Board and its committees, to promote the interests of stockholders, and to ensure a common set of expectations as to how the Board, its various committees, individual directors and management should perform their functions. These Guidelines are in addition to and are not intended to change or interpret any Federal or state law or regulation, including the Delaware General Corporation Law, or the Certificate of Incorporation or By-laws of the Company. The Board believes these Guidelines should be an evolving set of corporate governance principles, subject to alteration as circumstances warrant.I.The BoardA.Role of BoardThe business and affairs of the Company are managed by or under the direction of the Board in accordance with Delaware law. The Board's responsibility is to provide direction and oversight. The Board establishes the strategic direction of the Company and oversees the performance of the Company's business and management. The management of the Company is responsible for presenting strategic plans to the Board for review and approval and for implementing the Company's strategic direction. In performing their duties, the primary responsibility of the directors is to exercise their business judgment in the best interests of the Company.Certain specific corporate governance functions of the Board are set forth below:•Management Evaluation and Compensation. The Board has the responsibility to select and make decisions about the retention of the Company's Chief ExecutiveOfficer ("CEO") and to oversee the selection and performance of other executiveofficers. The Compensation Committee has the management evaluation andcompensation responsibilities set forth in the Compensation Committee charter.•Management Succession. The Board shall, with such assistance from the Nominating and Governance Committee as the Board shall request, review andconcur in a management succession plan, developed by the CEO, to ensure continuityin senior management. This plan, on which the CEO shall report at least annually,shall address: emergency CEO succession; CEO succession in the ordinary course ofbusiness; and succession for the other members of senior management.•Director Compensation. The Nominating and Governance Committee shall periodically review the form and amounts of director compensation and makerecommendations to the Board with respect thereto. The Board shall set the form andamounts of director compensation, taking into account the recommendations of theNominating and Governance Committee. Determination of director compensationshall be guided by three goals: compensation should fairly pay directors for workrequired consistent with a company of Danaher's size and scope; compensationshould align directors' interests with the long-term interests of shareholders; and thestructure of the compensation should be simple, transparent and easy for shareholdersto understand. Only non-management directors shall receive compensation forservices as a director. To create a direct linkage with corporate performance, theBoard believes that a meaningful portion of the total compensation of non-management directors should be provided and held in equity-based compensation.B.Board SizeThe Board’s size is set in accordance with the Company’s by-laws, to permit diversity of experience without hindering effective discussion or diminishing individual accountability. The Board will periodically review the size of the Board, and determine the size that is most effective in relation to future operations.C.Board Composition and IndependenceThe members of the Board should collectively possess a range of skills, knowledge, expertise (including business and other relevant experience) and backgrounds:•useful and appropriate to the effective oversight of the Company's business, and•appropriate to building a Board that is effective in collectively meeting the Company's strategic needs and serving the long-term interests of the shareholders.The Board shall consist of a majority of directors who qualify as independent directors (the “Independent Directors”) under the listing standards of the New York Stock Exchange (the “NYSE”). The Board shall review annually each director's relationships with the Company (either directly or as a partner, shareholder, or officer of an organization that has a relationship with the Company), if any. Following such annual review, only those directors whom the Board affirmatively determines have no material relationship with the Company (either directly or as a partner, shareholder, or officer of an organization that has a relationship with the Company) will be considered Independent Directors, subject to any additional independence qualifications that may be prescribed under the listing standards of the NYSE from time to time.The Board anticipates that the Company’s CEO will be regularly nominated to serve on the Board. The Board may also appoint or nominate other members of the Company’s management whose experience and role at the Company are expected to help the Board fulfill its responsibilities.D.Selection of NomineesThe Board will be responsible for the selection of all candidates for nomination or appointment as Board members. The Board's Nominating and Governance Committee shall beresponsible for identifying and recommending to the Board qualified candidates for Board membership, based primarily on the following criteria:•personal and professional integrity and character;•prominence and reputation in the candidate's profession;•skills, knowledge and expertise (including business or other relevant experience) useful and appropriate to the effective oversight of the Company's business;•the extent to which the interplay of the candidate's skills, knowledge, expertise and background with that of the other Board members will help build a Board that iseffective in collectively meeting the Company's strategic needs and serving the long-term interests of the shareholders;•the capacity and desire to represent the interests of the shareholders as a whole; and•availability to devote sufficient time to the affairs of the Company.E. Director Elections and ResignationsIn accordance with the Company’s By-laws, if none of our stockholders provides the Company notice of an intention to nominate one or more candidates to compete with the Board's nominees in a Director election, or if our stockholders have withdrawn all such nominations by the tenth day before the Company mails its notice of meeting to our stockholders, a nominee must receive more votes cast for than against his or her election or re-election in order to be elected or re-elected to the Board. The Board expects a Director to tender his or her resignation if he or she fails to receive the required number of votes for re-election. The Board shall nominate for election or re-election as Director only candidates who agree to tender, promptly following the annual meeting at which they are elected or re-elected as Director, irrevocable resignations that will be effective upon (i) the failure to receive the required vote at the next annual meeting at which they face re-election and (ii) Board acceptance of such resignation. In addition, the Board shall fill Director vacancies and new directorships only with candidates who agree to tender, promptly following their appointment to the Board, the same form of resignation tendered by other Directors in accordance with this Board Practice. If an incumbent Director fails to receive the required vote for re-election, the Nominating and Governance Committee will act on an expedited basis to determine whether to accept the Director's resignation and will submit such recommendation for prompt consideration by the Board. The Board expects the Director whose resignation is under consideration to abstain from participating in any decision regarding that resignation. The Nominating and Governance Committee and the Board may consider any factors they deem relevant in deciding whether to accept a Director's resignation.F. TenureWhen a director's principal occupation changes substantially from the position he or she held when most recently elected or appointed to the Board, the director shall tender a letter of proposed resignation from the Board to the chair of the Nominating and Governance Committee and the Company Secretary (which shall be effective only if accepted by the Board). The Nominating and Governance Committee shall review the director's continuation on the Board, and recommend to the Board whether, in light of all the circumstances, the Board should accept or reject such proposed resignation; provided, that in making such recommendation theNominating and Governance Committee shall consider, among such other factors as it deems relevant, that such director was elected by the shareholders of the Company.The Board does not believe that arbitrary term limits on directors' service are appropriate. The Board annually evaluates each director as part of the board and committee self-evaluation process described below.G. Limits on Other Board MembershipsDirectors should not serve on more than four boards of public companies in addition to the Board. Current positions in excess of these limits may be maintained unless the Board determines that doing so would impair the director's service on the Board. Directors should advise the Chairman of the Board (the “Chair”), the chair of the Nominating and Governance Committee and the Company Secretary before accepting membership on another board of directors or audit committee or any other significant committee assignment, or establishing any significant relationship with any business, institution or other governmental or regulatory entity, and should advise the Chair, the chair of the Nominating and Governance Committee and the Company Secretary of any other material change in circumstance or relationship that may impact a director's independence.H. Chairman of the BoardThe Board appoints the Chair. The offices of the Chair and the CEO shall be vested in separate persons.I. Lead Independent DirectorWhenever the Chair is not independent, a majority of the Independent Directors then in office will select a Lead Independent Director from among the Independent Directors. The Nominating and Governance Committee shall provide its recommendation as to which Independent Director should serve as the Lead Independent Director. The Lead Independent Director will:•preside at all meetings of the Board at which the Chair and the Chair of the Executive Committee are not present, including the executive sessions of non-managementdirectors;•have the authority to call meetings of the Independent Directors;•act as a liaison as necessary between the Independent Directors and the management directors; and•advise with respect to the Board’s agenda.J. Pledging of Danaher StockNo director or executive officer of the Company may pledge as security under any obligation any shares of Company common stock that he or she directly or indirectly owns and controls (provided that any shares of Company common stock directly or indirectly owned and controlled by any director or executive officer of the Company that were pledged as of February 21, 2013 (including any additional shares accruing thereto on or after such date as a result of any stock splits, stock dividends or similar transactions after such date) are not covered by this policy (“Permitted Pledged Shares”)). Permitted Pledged Shares shall not be counted toward the stockownership requirements set forth under the Danaher Stock Ownership Requirements for Directors and Executive Officers.II.Board and Committee MeetingsA. MeetingsThe Board has five regular meetings each year, and such special meetings as are deemed necessary, at which it reviews and discusses reports by management on the performance of the Company, its plans and prospects, as well as immediate, material issues facing the Company. The Chair, in consultation with appropriate members of the Board and with management, shall set the frequency and length of each meeting and the meeting agenda. Management will be responsible for ensuring that, a s a general rule absent exigent circumstances, Board members receive information prior to each Board meeting or committee meeting, as applicable, so that they have an opportunity to reflect properly on the matters to be considered at the meeting. Materials presented to Board members should provide the information needed for the Board members to make an informed judgment or engage in informed discussion.The Board welcomes attendance at Board meetings of senior officers of the Company. Invitations shall be extended by the Chair.Each director is expected to attend all scheduled Board meetings and meetings of committees on which he or she serves. Each director is also expected to review the materials provided by management and advisors in advance of the meetings of the Board and the committees on which such director serves.B. Board CommitteesThe Board has delegated authority to six standing committees: Audit, Compensation, Nominating and Governance, Finance, Executive and Science & Technology. Each committee, other than the Executive, Finance and Science & Technology Committees, is comprised solely of Independent Directors. Committee members and chairs will be appointed by the Board upon the recommendation of its Nominating and Governance Committee. There are no fixed terms for service on committees.Each Committee shall have the number of meetings provided for in its charter, with further meetings to occur (or action to be taken by unanimous written consent) when deemed necessary or desirable by the Committee chair. The Committee chairperson, in consultation with appropriate members of the Committee and with management, shall set the frequency and length of each meeting and the meeting agenda (consistent with any applicable charter requirements). Board members who are not members of a particular committee are welcome to attend meetings of that committee. The Committee chairperson shall report matters considered and acted upon to the full Board at the next regularly scheduled Board meeting. The Board believes that as a practice all Board members should receive notice of each Committee meeting and receive a copy of the minutes of each Committee meeting.C. Meetings of Non-Management DirectorsTo ensure free and open discussion and communication among the non-management directors, these directors shall meet in executive session at least twice per calendar year with nomembers of management present. To the extent the group of non-management directors includes any directors who are not independent, the Independent Directors shall meet in executive session at least once per calendar year.Normally, the meetings described in the preceding paragraph will occur prior to or following regularly scheduled board meetings. The Lead Independent Director shall preside at the aforementioned executive sessions.III.Director Orientation and Continuing EducationThe Chief Financial Officer, General Counsel, Chief Accounting Officer and Company Secretary shall be responsible for providing an orientation for new directors, and for periodically providing materials, briefings and other educational opportunities to permit them to become more familiar with the Company and to enable them to better discharge their duties as directors. Each new director shall, within six months of election to the Board, spend a day at corporate headquarters for personal briefing by senior management on the Company's business, strategic plans, financial statements and key policies and practices.IV.Self EvaluationThe Board and each of the Audit, Compensation and Nominating & Governance committees conduct a self-evaluation annually to assess whether it and its committees are functioning effectively. The Nominating and Governance Committee will solicit each director for his or her assessments of the effectiveness of the Board and the committees on which he or she serves, and will report annually to the Board with an assessment of the Board’s performance, which will be discussed with the full Board.The Nominating and Governance Committee’s assessment will focus on the members’ contributions (e.g., attendance, preparedness and participation) to the Board and its committees, the Board’s contributions to the Company and will identify areas for improvement in the performance of the Board and its committees.V.Access to Senior Management and Independent AdvisorsBoard members have full access to senior management and to information about the Company’s operations. Independent directors are encouraged to contact senior managers of the Company without senior corporate management present. In addition, the Board and its committees shall have the right at any time to retain independent outside financial, legal or other advisors, as they deem necessary and appropriate.。

董事会特征、会计报告可靠性与债务成本

Board characteristics, accounting report integrity, and the cost of debt,Ronald C. Anderson a, Sattar A. Mansi b, David M. Reeb c*a Kogod School of Business, American University, Washington, DC 20016, USAb Pamplin College of Business, Virginia Tech, Blacksburgh, VA 24061, USAc Fox School of Business, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA 19122, USAReceived 21 February 2003; received in revised form 26December 2003; accepted 16 January 2004AbstractCreditor reliance on accounting-based debt covenants suggests that debtors are potentially concerned with board of director characteristics that influence the integrity of financial accounting reports. In a sample of S&P 500 firms, we find that the cost of debt is inversely related to board independence and board size. We also find that fully independent audit committees are associated with a significantly lower cost of debt financing. Similarly, yield spreads are also negatively related to audit committee size and meeting frequency. Overall, these results provide market-based evidence that boards and audit committees are important elements affecting the reliability of financial reports.JEL classification:M4, K0, G3Keywords:Audit Committee Composition; Board Composition; Corporate Governance; Financial Statements; and Accounting Information_________,We would like to thank Anup Agrawal, Mark DeFond (the referee), Augustine Duru, Scott Lee, Bob Thompson, and seminar participants at American University, Temple University, Texas Tech, Virginia Tech and S.P. Kothari (the editor) for their helpful suggestions. All remaining errors are the sole responsibility of the authors.*Corresponding author. Present address: Fox School of Business, Temple University, 205 Spakman Hall, Philadelphia, PA 19122, USA; Tel.: +1-215-204-6117; fax: +1-215-204-1697.E-mail address: dreeb@ (D. Reeb)1. IntroductionAccounting-based numbers are a persistent and traditional standard that creditors use to assess firm health and viability. Smith and Warner (1979) note for instance, that such criteria have been used in lending agreements and debt covenants for hundreds of years. Firms violating these accounting-based standards allow debt holders, as senior claimants, to liquidate projects or renegotiate lending contracts (DeFond and Jiambalvo (1994)). Managers as such, may have incentives to issue misleading financial statements to conceal negative news and thereby provide private personal benefits or potential shareholder benefits (Dechow, Sloan, and Sweeney (1996)). The importance creditors place on accounting numbers and the countervailing managerial incentives to manipulate these reports suggests that bondholders potentially exhibit great concern over factors influencing the reliability and validity of the financial accounting process (Smith (1993) and Leftwich (1983)).1From a creditor’s perspective, perhaps one of the most important factors influencing the integrity of the financial accounting process involves the board of directors.2 Boards of directors, among other tasks, are charged with monitoring and disciplining senior management, and lending agreements typically require that boards supply audited financial statements to the firm’s creditors (Daley and Vigeland (1983), DeFond and Jiambalvo (1994), and Dichev and Skinner (2002)). Klein (2002a), Carcello and Neal (2000), Beasley (1996), and Dechow, Sloan, and Sweeney (1996) examine the importance of directors monitoring the financial accounting process and document a relation between board characteristics and manipulation of accounting information. Board attributes that influence the validity of accounting statements may thus be of great importance to creditors. Smith1 Anecdotal accounts in the popular press are illustrative. For example, recent announcements concerning the reliability of the financial statements at Levi Straus led to a sharp reduction in the price of Levi’s bonds (see Wall Street Journal, June 2, 2003, p. A3).2 Swiss Venture Funds for instance, typically requires a non-voting seat on a firm’s board of directors (board observation rights) for the firm to obtain Swiss Venture’s private-unsecured debt. Similarly, Caltius, UPS, Alliance Capital, and numerous other firms in the private debt market typically seek observation rights for board of director meetings. Thus, as Standard & Poor’s note in their credit rating documentation, board oversight of the accounting information process is a paramount concern in assessing firm default risk.and Warner (1979) suggest that creditors price the firm’s debt to reflect the difficulties in ensuring the validity of the lending agreement, indicating that if board structure is an important oversight element in the financial accounting process, debt prices may be sensitive to board of director characteristics.In this study, we examine the relation between board structure and the cost of debt financing. Assuming independent directors are superior monitors of management and likely to provide credible financial reports, we test whether the firm’s cost of debt (yield spread) decreases in the proportion of independent directors on the board. We also examine the relation between board size and the cost of debt financing. Klein (1998, 2002b) indicates that the number of directors on the board affects committee assignments and board monitoring. Similarly, Adams and Mehran (2001) suggest that bigger boards increase monitoring effectiveness and provide for greater board expertise. As such, we posit that debt yields are negatively related to board size as larger boards may increase the level of managerial monitoring (i.e., a greater number of guards) and enhance the financial accounting process.3For most large firms, boards of directors delegate direct oversight of the financial accounting process to a subcommittee of the full board, the audit committee. Audit committees are responsible for recommending the selection of external auditors to the full board; ensuring the soundness and quality of internal accounting and control practices; and monitoring external auditor independence from senior management. Recent regulations put forth by the major stock exchanges requiring that a minimum of three independent directors serve on the audit committee suggest that committee independence and size may be integral factors for firms in delivering meaningful financial reports (Klein (2002a)). Carcello and Neal (2000) provide support for this argument by documenting a relation between greater audit committee independence and the quality of financial reporting. If3 Lipton and Lorsch (1992), Jensen (1993), and Yermack (1996) argue that larger boards are less effective in group decision-making and strategy formulation, which suggests that equity holders would have divergent interests from debtors on board size. We explore this issue in greater detail in Section 2.audit committee composition influences the financial accounting process, we then anticipate that corporate debt yields will exhibit an inverse relation to committee independence and size.Using a sample of 252 industrial firms from the Lehman Brothers Fixed Income database and the S&P 500, we find that board independence is associated with a lower cost of debt financing. After controlling for industry and firm specific attributes, our analysis indicates that debt costs (using non-provisional publicly traded debt) are 17.5 basis points lower for firms with boards dominated by independent directors (51 percent independents) relative to firms with insider-stacked boards (25 percent independents). We also find a negative relation between board size and the cost of debt financing. Specifically, we find that an additional board member is associated with about a 10 basis point lower cost of debt financing. The results are robust to various measures of board independence, board size, endogeneity, non-linear specifications, and are both economically and statistically significant. Overall, our empirical results indicate that bondholders view board independence as an important element in the pricing of the firm’s debt, suggesting that creditors are sensitive to board attributes that affect reporting validity.The analysis also indicates that creditors view audit committees and their characteristics as important elements in the financial accounting process. Specifically, we find that the cost of debt is about 15 basis points lower for firms with fully-independent audit committees relative to those with insiders or affiliates on the committee. Focusing on the size of audit committees, we find that committee size ranges from one to 12 directors, with most committees having either 4 or 5 members. The analysis indicates that for the average-size audit committee, an additional board member is associated with a 10.6 basis point lower cost of debt. Although, the reduction in the cost of debt for this additional audit committee member appears large, an additional member results in approximately a 20% change in committee size.4 One implication of these results is that creditors4 One potential concern is that the audit committee size results are an artifact of firm size. Although we control for firm size in our primary regressions, we also perform subsequent tests in Section5 that use audit committee size scaled by firm size and size-based subset tests (with similar results). In addition, it is important to note that this lower cost of debt is for an additional audit committee member in the average size committee. As audit committee size continues toview audit committees with 4 or 5 members very differently than those with only one or two members. Overall, these results suggest that creditors view audit committees as an important device in ensuring the reliability of accounting reports.We also conduct supplemental analysis on independent director attributes. Monks and Minnow (1995) and Beasley (1996) suggest that director expertise or occupational characteristics may influence the board’s ability to effectively monitor management and the firm. Our results indicate that independent-director employment characteristics (executive, retired, academic, etc.), while all significantly related to lower debt costs, are not substantively different from one another. Recent passage of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act by the US Congress also requires that at least one “financial expert” serve on the firm’s audit committee.5 In light of this new regulation, we also investigate whether financial experts influence the cost of debt financing. Consistent with our earlier results on director employment characteristics, we find no relation between debt costs and financial experts serving on the audit committee. In sum, these tests suggest that the primary concern of creditors is the presence of independent directors on the board and audit committee, as opposed to director expertise.The investigation also suggests that director equity ownership is not related to the cost of debt financing. In contrast, board tenure is positively related to corporate yield spreads, suggesting that as director tenure increases, managers are potentially more able to influence or sway board opinion. Audit-committee meeting frequency also exhibits a negative relation to debt costs, indicating bondholder concern with directors actively monitoring the financial accounting process.increase, we find a diminishing cost of debt for each additional member. For example, at the top decile of the distribution for audit committee size, the analysis suggests only a 5 basis point lower cost of debt.5 The Sarbanes-Oxley Act specifies that for a director to be classified as a financial expert that the individual should have knowledge through education or work experience of: (i) Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), (ii) preparing or auditing public company financial statements, (iii) applying GAAP in connection with accounting estimates, accruals and reserves, (iv) internal accounting controls and, (v) the audit committee function. Due to a large number of registrant complaints, the SEC expanded the definition of a financial expert to include any director that has supervised any finance or accounting personnel – essentially suggesting that any executive who has managed a financial/accounting employee is a financial expert. For the tests in this paper, we use a narrower definition of financial expert. Section 3 provides greater detail on our categorization.Although our results are consistent with the hypothesis that board structure influences the accounting reports that creditors use in managing lending agreements, an alternative explanation for the observed relation focuses on firm performance. Specifically, Monks and Minnow (1995) argue that board monitoring can improve the quality of managerial decision-making and lead to better firm performance; suggesting that better firm performance results in lower yield spreads. Prior literature however, provides little evidence of independent boards improving firm performance (see Hermalin and Weisbach (2003)). Still, we include several proxies for firm performance (e.g. cash flows, credit ratings, etc.) in our analysis to alleviate this concern. In addition, the results indicate that audit committee structure – a direct link between boards and financial reporting – affects the cost of debt. Finally, because audit committee characteristics may simply capture full board attributes, we examine whether audit committee characteristics exhibit incremental explanatory power over full board traits. Again we observe a negative relation between audit committee attributes and the cost of debt financing; suggesting that the link between debt costs and audit/board characteristics is the financial accounting process. However, to the extent that these measures do not fully capture firm performance, both the accounting process hypothesis and firm performance potentially explain the documented relation.This research contributes to the literature in several important ways. First, our analysis suggests that debt holders exhibit interest in board and audit committee monitoring of the financial accounting process. Second, our analysis supports the notion that board independence and board size influence the cost of debt financing. We interpret this to suggest that bondholders are concerned with governance mechanisms that limit managerial opportunism and improve the financial accounting process. Third, our analysis suggests larger, more independent audit committees provide a measurable and significant benefit to the firm, namely through a lower cost of debt financing. These results support recent regulatory and listing requirements (see NYSE, NASDAQ, recent SEC proposals, and the Sarbanes-Oxley Act) concerning audit committee independence; as well as calls for more actively involved audit committees. Fourth, we find thatdirector independence, rather than director expertise, is the more relevant issue in the cost of debt capital. In aggregate, our analysis provides market-based evidence to suggest that boards and audit committees are important mechanisms in overseeing the financial accounting process.The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 develops our testable hypothesis and section 3 describes our sample and gives summary statistics. Section 4 provides the multivariate analysis and section 5 examines alternative specifications and test procedures. Section 6 concludes the paper.2. Board Characteristics and Monitoring the Financial Accounting ProcessThe Securities and Exchange Commission, the Financial Accounting Standards Board, and the major stock exchanges regularly emphasize the role of board of directors in overseeing the financial accounting process. Boards comprising mostly employee or employee-related directors may be more willing to conceal negative information to gain private benefits or to limit stakeholder intervention in the firm. Recent reports in the financial press suggest that some boards “shut their eyes when the numbers are squishy or even fraudulent,” leading to several well-publicized scandals.6 Yet, Beasley (1996), Dechow, Sloan, and Sweeney (1996), and Fama and Jensen (1983) suggest that independent directors are more willing to provide effective oversight and disclosure due to their desire to maintain their reputations. In the debate over director efficacy, prior literature primarily focuses on four board characteristics; (i) board independence, (ii) board size, (iii) committee structure, and (iv) specific occupational characteristics or expertise of independent directors. In the following sub-sections, we develop testable hypotheses on the relation between debt yields and board structure.2.1. Board Independence, the Financial Accounting Process, and the Cost of Debt FinancingSmith and Warner (1979) and Kalay (1982) observe that bondholders’ concerns lie with 6New York Times (1/26/03) pages B1 and B12 (The Revolution That Wasn’t).protecting their investment.7 One of the more important elements in bondholders’ ability to protect their investments is the firm’s financial accounting numbers. Creditors use accounting numbers to judge compliance with debt covenants and to administer lending agreements (DeFond and Jiambalvo (1994) and Daley and Vigeland (1983)).Boards of directors have a primary responsibility of overseeing the firm’s financial reporting process. Boards meet routinely with the firm’s accounting staff and external auditors to review financial statements, audit procedures, and internal control mechanisms (Klein (2002a)). As such, bondholder’s potentially view boards of directors and, in particular, board structure as critical elements in delivering credible and relevant financial statements.Prior literature generally posits that board of director independence from senior management provides, among other things, the most effective monitoring and control of firm activities. Byrd and Hickman (1992) for instance, suggest that independent directors contribute expertise and objectivity that minimizes managerial entrenchment and expropriation of firm resources. Beasley (1996) and Dechow, Sloan, and Sweeney (1996) find that the proportion of independent directors on the board (board independence) is inversely related to the likelihood of financial statement fraud. More recently, Klein (2002a) documents a negative relation between abnormal accruals and director independence from senior management. If independent boards provide superior oversight of the financial accounting process, then we expect bondholders to directly benefit through greater transparency and validity in accounting reports. This leads to our first testable hypothesis:Hypothesis 1: Greater board independence is associated with lower corporate-debt yield spreads.2.2. Board Size, the Financial Accounting Process, and the Cost of Debt FinancingRecent research also indicates that board size may play an important role in directors’ ability7 Branch (2000) and Perumpral, Davidson, and Sen (1999) discusses creditor rights and fiduciary responsibilities in bankruptcy. Mansi, Maxwell, and Miller (2003) discuss the impact of auditor choice and tenure on creditors, while Begley (1990) discusses debt covenants and accounting choices. Betker (1995) examines creditor and board issuesto monitor and control managers. Lipton and Lorsh (1992) and Jensen (1993) for instance, argue that because of difficulties in organizing and coordinating large groups of directors, board size is negatively related to the board’s ability to advise and engage in long-term strategic planning. In contrast, Adams and Mehran (2002) and Yermack (1996) suggest that some firms require larger boards for effective monitoring. Chaganti, Mahajan, and Sharma (1985) posit that large boards are valuable for the breadth of their services. Klein (2002b) for instance, finds that board committee assignments are influenced by board size since large boards have more directors to spread around. As such, she suggests that board monitoring is increasing in board size due to the ability to distribute the work load over a greater number of observers. Monks and Minow (1995) and Lipton and Lorsch (1992) extend this argument by suggesting that larger (smaller) boards are able to commit more (less) time and effort to overseeing management.8 If large boards are more effective monitors of the financial accounting process, then bondholders should benefit through improved financial transparency and reliability. This leads to our second testable hypothesis:Hypothesis 2: Larger boards of directors are associated with lower corporate-debt yield spreads.2.3. Audit Committee Structure and Cost of Debt FinancingAlthough boards of directors are responsible for oversight of the financial accounting process, this task is often delegated to a subcommittee of the full board, the audit committee. The audit committee plays an important role because it is concerned with establishing and monitoring the accounting processes to provide relevant and credible information to the firm’s stakeholders (Pincus et al. (1989), Beasley (1996)). The 1999 Blue Ribbon Committee Report (co-sponsored by the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) and the National Association of Security Dealers (NASD))in default and Duke and Hunt (1990) discuss creditor demands for monitoring.8 Monks and Minow (1995) note that most companies typically have several committees and that larger boards allow for fewer committee assignments per director. In this context, a larger board provides for greater task sharing and potentially better monitoring. However, the negative aspects to larger boards may be quite relevant to shareholders, such as increased formalism, slower decision-making, and greater inflexibility.indicates that independent audit committee members are better able to protect the reliability of the accounting process. Following the report, the NYSE and the NASD, along with the SEC, proposed that listed firms maintain standing audit committees with at least three independent directors; with the express purpose of monitoring the accounting information process (Klein (2002a)). If independent audit committees provide more reliable accounting information (relative to insider-stacked committees), then we expect the cost of debt to be related to audit committee composition. This leads to our third hypothesis:Hypothesis 3: Greater audit committee independence is associated with lower corporate-debt yield spreads.2.4. Audit Committee Size and Cost of Debt FinancingThe recent regulations put forth by the major stock exchanges stipulating that audit committees comprise at least three members implies that governing bodies deem audit committee size as an integral attribute in controlling the accounting process. Pincus et al. (1989) suggest that audit committees are an expensive monitoring mechanism and that firms with greater agency costs are potentially more willing to bear these expenses. In this context, firms with larger audit committees are willing to devote greater resources to overseeing the financial accounting process. A firm with an audit committee composed of only a couple of members would, on average, have less time to devote to overseeing the hiring of auditors, questioning management, and meeting with internal control system personnel. If large audit committees better protect and control financial standards than small committees, we then expect greater accounting transparency and a lower cost of debt financing. This leads to our fourth testable hypothesis:Hypothesis 4: Larger audit committees are associated with lower corporate-debt yield spreads.2.5. Director Characteristics, the Financial Accounting Process, and the Cost of Debt FinancingEffective monitoring also requires both expertise and proper incentives (Beasly (1996)). Fama and Jensen (1983) suggest that independent directors are effective monitors because of reputation concerns and their desire to obtain additional director positions. Jensen and Meckling (1976) argue that director equity-ownership creates powerful incentives for directors to monitor management. Generally, the literature suggests that professional directors and directors with equity stakes are associated with greater monitoring.Brickly, Coles, and Terry (1994) report that retired executives from other companies are also effective monitors. Similarly, Monks and Minow (1995) suggest that academics are less effective directors relative to those with business experience. As monitoring expertise increases, managerial opportunism becomes less prevalent, causing the value of investor claims to increase. Furthermore, effective monitoring is potentially an acquired skill, suggesting boards with greater tenure provide greater monitoring. However, as board tenure increases, managers may be better able to influence or sway director opinion, indicating director tenure exhibits an inverse relation to oversight of the financial accounting process. If director experience, tenure, or equity ownership creates incentives for independent directors to more closely monitor firm management, then we expect bondholders to benefit through credible and transparent financial statements. This leads to our fifth testable hypothesis:Hypothesis 5: Greater board expertise (ownership) is associated with lower corporate-debt yield spreads.Finally, we focus on audit-committee director attributes and committee meeting frequency. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act requires that audit committees include at least one “financial expert.” Similar to our arguments on director experience, we posit that financial experts on the audit committee lead to greater rigor in financial reporting. The 1999 Blue Ribbon Committee Report likewise advocates that the audit committee, as the watchdog of the financial accounting process, can best assure the quality of the financial statements by having at least 4 meetings a year (Morrissey (2000)).If financial expertise on the audit committee or committee meeting frequency improves the financial accounting process, we anticipate a negative relation between these attributes and debt costs. This leads to our final two hypotheses:Hypothesis 6: Financial expertise on the audit committee is associated with lower corporate-debtyield spreads.Hypothesis 7: Audit committee meeting frequency is associated with lower corporate-debt yield spreads.3. Data Description3.1. The SampleFor our sample, we collect information on firms that are in both the Lehman Brothers Fixed Income database (LBFI) and the S&P 500 Industrial Index (as of December 31, 1992). The LBFI provides month-end security-specific information on bonds that are in the Lehman Brothers Indices. The goal of the database is to provide a representative sample of outstanding publicly traded debt. Information is provided on coupons, yields, maturities, credit ratings from Moody’s and S&P, bid prices, durations, convexities, holding period returns, call and put provisions, and sinking fund provisions. Lehman Brothers selects bonds for inclusion in the database based on firm size, liquidity, credit ratings, subordination, and maturity. The database contains non-provisional bonds of differing maturities, differing credit ratings, and differing debt claims (senior and subordinated debt). Although the database does not contain the universe of traded debt, we have no reason to suspect any systematic bias within the sample. We exclude financial and utility firms from the sample because of the potential effect of regulations on debt yields.We manually collect data from corporate proxy statements on board structure, audit committee composition, and other governance characteristics for the S&P 500 Industrial firms. To gather firm-specific financial data not already included in the Lehman Brothers Database, we use the。

金融学精选专题-教学大纲

《金融学精选专题》教学大纲课程编号:151423B课程类型:□通识教育必修课□通识教育选修课□专业必修课☑专业选修课□学科基础课总学时:48 讲课学时:48 实验(上机)学时:0学分:3适用对象:金融学(数据与计量分析)专业本科生先修课程:无一、教学目标金融学精选专题是为金融学(数据与计量分析)专业本科生而开设的课程,没有先修课程要求。

通过本门课程的教学,使学生了解时下金融学前沿话题、探索金融研究方法、培养学生对金融学术的兴趣。

教学过程中,本课程采用课堂讲授与课堂讨论相结合的方式,详细介绍各个金融研究领域话题的发展历史,现状以及前沿话题。

本课程主要目标为:了解经典文章和模型、了解金融研究的发展历史和发展趋势、掌握金融研究的基本方法、探索金融研究的未来发展趋势。

二、教学内容及其与毕业要求的对应关系(一)教学内容1.知识体系专题1:资本结构专题2:公司治理专题3:分红政策专题4:并购重组专题5:房地产金融专题6:行为金融专题7:资本资产定价(上)专题8:资本资产定价(下)2.本课程教学重点本课程主要包括八个专题,覆盖公司金融和资本资产定价两大领域中的前沿专题。

本课程的重点为金融学各个领域的前沿学术研究问题。

本课程以讲授金融学中的经典理论和模型为基础,着重讲授金融研究的发展和和当代金融研究的热点问题。

本课程与金融学其他基础课程有部分重合,例如资本结构专题会和公司金融和金融衍生品课程中的内容有少量重合。

重合部分不是本课程的讲授重点。

为帮助学生理解课堂讲授的内容,本课程会适当回顾金融学基础知识,但不会作为重点讲授内容。

(二)教学方法和手段本课程采用课堂讲授与课堂讨论相结合的方式。

本课程的授课语言为英语。

针对每个专题,老师着重讲解经典文章和经典模型。

此外,老师将选取每个金融领域最前沿的文章,让学生在课堂进行汇报与分组讨论。

每个小组选择一个专题,对前沿文章进行汇报,其他学生参与课堂讨论。

课堂汇报与讨论推荐学生选用英文。

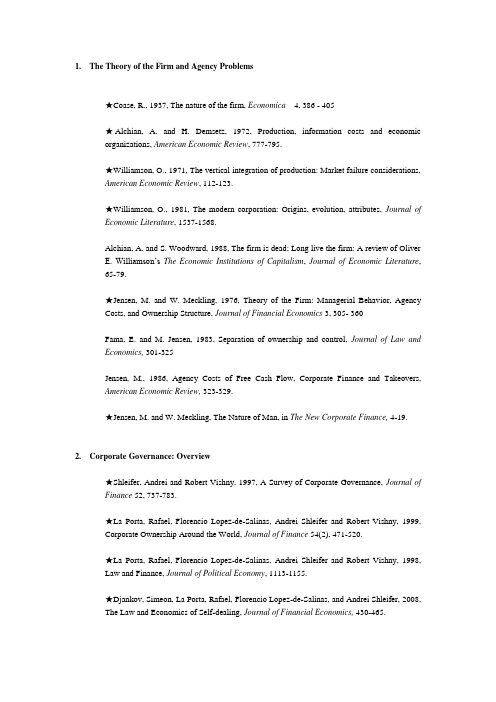

美国公司法证券法历年经典论文列表

美国是世界上公司法、证券法研究最为发达的国家之一,在美国法学期刊(Law Review & Journals)上每年发表400多篇以公司法和证券法为主题的论文。

自1994年开始,美国的公司法学者每年会投票从中遴选出10篇左右重要的论文,重印于Corporate Practice Commentator,至2008年,已经评选了15年,计177篇论文入选。

以下是每年入选的论文列表:2008年(以第一作者姓名音序为序):1.Anabtawi, Iman and Lynn Stout. Fiduciary duties for activist shareholders. 60 Stan. L. Rev. 1255-1308 (2008).2.Brummer, Chris. Corporate law preemption in an age of global capital markets. 81 S. Cal. L. Rev. 1067-1114 (2008).3.Choi, Stephen and Marcel Kahan. The market penalty for mutual fund scandals. 87 B.U. L. Rev. 1021-1057 (2007).4.Choi, Stephen J. and Jill E. Fisch. On beyond CalPERS: Survey evidence on the developing role of public pension funds in corporate governance. 61 V and. L. Rev. 315-354 (2008).5.Cox, James D., Randall S. Thoma s and Lynn Bai. There are plaintiffs and…there are plaintiffs: An empirical analysis of securities class action settlements. 61 V and. L. Rev. 355-386 (2008).6.Henderson, M. Todd. Paying CEOs in bankruptcy: Executive compensation when agency costs are low. 101 Nw. U. L. Rev. 1543-1618 (2007).7.Hu, Henry T.C. and Bernard Black. Equity and debt decoupling and empty voting II: Importance and extensions. 156 U. Pa. L. Rev. 625-739 (2008).8.Kahan, Marcel and Edward Rock. The hanging chads of corporate voting. 96 Geo. L.J. 1227-1281 (2008).9.Strine, Leo E., Jr. Toward common sense and common ground? Reflections on the shared interests of managers and labor in a more rational system of corporate governance. 33 J. Corp. L. 1-20 (2007).10.Subramanian, Guhan. Go-shops vs. no-shops in private equity deals: Evidence and implications.63 Bus. Law. 729-760 (2008).2007年:1.Baker, Tom and Sean J. Griffith. The Missing Monitor in Corporate Governance: The Directors’ & Officers’ Liability Insurer. 95 Geo. L.J. 1795-1842 (2007).2.Bebchuk, Lucian A. The Myth of the Shareholder Franchise. 93 V a. L. Rev. 675-732 (2007).3.Choi, Stephen J. and Robert B. Thompson. Securities Litigation and Its Lawyers: Changes During the First Decade After the PSLRA. 106 Colum. L. Rev. 1489-1533 (2006).4.Coffee, John C., Jr. Reforming the Securities Class Action: An Essay on Deterrence and Its Implementation. 106 Colum. L. Rev. 1534-1586 (2006).5.Cox, James D. and Randall S. Thomas. Does the Plaintiff Matter? An Empirical Analysis of Lead Plaintiffs in Securities Class Actions. 106 Colum. L. Rev. 1587-1640 (2006).6.Eisenberg, Theodore and Geoffrey Miller. Ex Ante Choice of Law and Forum: An Empirical Analysis of Corporate Merger Agreements. 59 V and. L. Rev. 1975-2013 (2006).7.Gordon, Jeffrey N. The Rise of Independent Directors in the United States, 1950-2005: Of Shareholder V alue and Stock Market Prices. 59 Stan. L. Rev. 1465-1568 (2007).8.Kahan, Marcel and Edward B. Rock. Hedge Funds in Corporate Governance and Corporate Control. 155 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1021-1093 (2007).ngevoort, Donald C. The Social Construction of Sarbanes-Oxley. 105 Mich. L. Rev. 1817-1855 (2007).10.Roe, Mark J. Legal Origins, Politics, and Modern Stock Markets. 120 Harv. L. Rev. 460-527 (2006).11.Subramanian, Guhan. Post-Siliconix Freeze-outs: Theory and Evidence. 36 J. Legal Stud. 1-26 (2007). (NOTE: This is an earlier working draft. The published article is not freely available, and at SLW we generally respect the intellectual property rights of others.)2006年:1.Bainbridge, Stephen M. Director Primacy and Shareholder Disempowerment. 119 Harv. L. Rev. 1735-1758 (2006).2.Bebchuk, Lucian A. Letting Shareholders Set the Rules. 119 Harv. L. Rev. 1784-1813 (2006).3.Black, Bernard, Brian Cheffins and Michael Klausner. Outside Director Liability. 58 Stan. L. Rev. 1055-1159 (2006).4.Choi, Stephen J., Jill E. Fisch and A.C. Pritchard. Do Institutions Matter? The Impact of the Lead Plaintiff Provision of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act. 835.Cox, James D. and Randall S. Thomas. Letting Billions Slip Through Y our Fingers: Empirical Evidence and Legal Implications of the Failure of Financial Institutions to Participate in Securities Class Action Settlements. 58 Stan. L. Rev. 411-454 (2005).6.Gilson, Ronald J. Controlling Shareholders and Corporate Governance: Complicating the Comparative Taxonomy. 119 Harv. L. Rev. 1641-1679 (2006).7.Goshen , Zohar and Gideon Parchomovsky. The Essential Role of Securities Regulation. 55 Duke L.J. 711-782 (2006).8.Hansmann, Henry, Reinier Kraakman and Richard Squire. Law and the Rise of the Firm. 119 Harv. L. Rev. 1333-1403 (2006).9.Hu, Henry T. C. and Bernard Black. Empty V oting and Hidden (Morphable) Ownership: Taxonomy, Implications, and Reforms. 61 Bus. Law. 1011-1070 (2006).10.Kahan, Marcel. The Demand for Corporate Law: Statutory Flexibility, Judicial Quality, or Takeover Protection? 22 J. L. Econ. & Org. 340-365 (2006).11.Kahan, Marcel and Edward Rock. Symbiotic Federalism and the Structure of Corporate Law.58 V and. L. Rev. 1573-1622 (2005).12.Smith, D. Gordon. The Exit Structure of V enture Capital. 53 UCLA L. Rev. 315-356 (2005).2005年:1.Bebchuk, Lucian Arye. The case for increasing shareholder power. 118 Harv. L. Rev. 833-914 (2005).2.Bratton, William W. The new dividend puzzle. 93 Geo. L.J. 845-895 (2005).3.Elhauge, Einer. Sacrificing corporate profits in the public interest. 80 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 733-869 (2005).4.Johnson, . Corporate officers and the business judgment rule. 60 Bus. Law. 439-469 (2005).haupt, Curtis J. In the shadow of Delaware? The rise of hostile takeovers in Japan. 105 Colum. L. Rev. 2171-2216 (2005).6.Ribstein, Larry E. Are partners fiduciaries? 2005 U. Ill. L. Rev. 209-251.7.Roe, Mark J. Delaware?s politics. 118 Harv. L. Rev. 2491-2543 (2005).8.Romano, Roberta. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act and the making of quack corporate governance. 114 Y ale L.J. 1521-1611 (2005).9.Subramanian, Guhan. Fixing freezeouts. 115 Y ale L.J. 2-70 (2005).10.Thompson, Robert B. and Randall S. Thomas. The public and private faces of derivative lawsuits. 57 V and. L. Rev. 1747-1793 (2004).11.Weiss, Elliott J. and J. White. File early, then free ride: How Delaware law (mis)shapes shareholder class actions. 57 V and. L. Rev. 1797-1881 (2004).2004年:1Arlen, Jennifer and Eric Talley. Unregulable defenses and the perils of shareholder choice. 152 U. Pa. L. Rev. 577-666 (2003).2.Bainbridge, Stephen M. The business judgment rule as abstention doctrine. 57 V and. L. Rev. 83-130 (2004).3.Bebchuk, Lucian Arye and Alma Cohen. Firms' decisions where to incorporate. 46 J.L. & Econ. 383-425 (2003).4.Blair, Margaret M. Locking in capital: what corporate law achieved for business organizers in the nineteenth century. 51 UCLA L. Rev. 387-455 (2003).5.Gilson, Ronald J. and Jeffrey N. Gordon. Controlling shareholders. 152 U. Pa. L. Rev. 785-843 (2003).6.Roe, Mark J. Delaware 's competition. 117 Harv. L. Rev. 588-646 (2003).7.Sale, Hillary A. Delaware 's good faith. 89 Cornell L. Rev. 456-495 (2004).8.Stout, Lynn A. The mechanisms of market inefficiency: an introduction to the new finance. 28 J. Corp. L. 635-669 (2003).9.Subramanian, Guhan. Bargaining in the shadow of takeover defenses. 113 Y ale L.J. 621-686 (2003).10.Subramanian, Guhan. The disappearing Delaware effect. 20 J.L. Econ. & Org. 32-59 (2004)11.Thompson, Robert B. and Randall S. Thomas. The new look of shareholder litigation: acquisition-oriented class actions. 57 V and. L. Rev. 133-209 (2004).2003年:1.A yres, Ian and Stephen Choi. Internalizing outsider trading. 101 Mich. L. Rev. 313-408 (2002).2.Bainbridge, Stephen M. Director primacy: The means and ends of corporate governance. 97 Nw. U. L. Rev. 547-606 (2003).3.Bebchuk, Lucian, Alma Cohen and Allen Ferrell. Does the evidence favor state competition in corporate law? 90 Cal. L. Rev. 1775-1821 (2002).4.Bebchuk, Lucian Arye, John C. Coates IV and Guhan Subramanian. The Powerful Antitakeover Force of Staggered Boards: Further findings and a reply to symposium participants. 55 Stan. L. Rev. 885-917 (2002).5.Choi, Stephen J. and Jill E. Fisch. How to fix Wall Street: A voucher financing proposal for securities intermediaries. 113 Y ale L.J. 269-346 (2003).6.Daines, Robert. The incorporation choices of IPO firms. 77 N.Y.U. L. Rev.1559-1611 (2002).7.Gilson, Ronald J. and David M. Schizer. Understanding venture capital structure: A taxexplanation for convertible preferred stock. 116 Harv. L. Rev. 874-916 (2003).8.Kahan, Marcel and Ehud Kamar. The myth of state competition in corporate law. 55 Stan. L. Rev. 679-749 (2002).ngevoort, Donald C. Taming the animal spirits of the stock markets: A behavioral approach to securities regulation. 97 Nw. U. L. Rev. 135-188 (2002).10.Pritchard, A.C. Justice Lewis F. Powell, Jr., and the counterrevolution in the federal securities laws. 52 Duke L.J. 841-949 (2003).11.Thompson, Robert B. and Hillary A. Sale. Securities fraud as corporate governance: Reflections upon federalism. 56 V and. L. Rev. 859-910 (2003).2002年:1.Allen, William T., Jack B. Jacobs and Leo E. Strine, Jr. Function over Form: A Reassessment of Standards of Review in Delaware Corporation Law. 26 Del. J. Corp. L. 859-895 (2001) and 56 Bus. Law. 1287 (2001).2.A yres, Ian and Joe Bankman. Substitutes for Insider Trading. 54 Stan. L. Rev. 235-254 (2001).3.Bebchuk, Lucian Arye, Jesse M. Fried and David I. Walker. Managerial Power and Rent Extraction in the Design of Executive Compensation. 69 U. Chi. L. Rev. 751-846 (2002).4.Bebchuk, Lucian Arye, John C. Coates IV and Guhan Subramanian. The Powerful Antitakeover Force of Staggered Boards: Theory, Evidence, and Policy. 54 Stan. L. Rev. 887-951 (2002).5.Black, Bernard and Reinier Kraakman. Delaware’s Takeover Law: The Uncertain Search for Hidden V alue. 96 Nw. U. L. Rev. 521-566 (2002).6.Bratton, William M. Enron and the Dark Side of Shareholder V alue. 76 Tul. L. Rev. 1275-1361 (2002).7.Coates, John C. IV. Explaining V ariation in Takeover Defenses: Blame the Lawyers. 89 Cal. L. Rev. 1301-1421 (2001).8.Kahan, Marcel and Edward B. Rock. How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Pill: Adaptive Responses to Takeover Law. 69 U. Chi. L. Rev. 871-915 (2002).9.Kahan, Marcel. Rethinking Corporate Bonds: The Trade-off Between Individual and Collective Rights. 77 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1040-1089 (2002).10.Roe, Mark J. Corporate Law’s Limits. 31 J. Legal Stud. 233-271 (2002).11.Thompson, Robert B. and D. Gordon Smith. Toward a New Theory of the Shareholder Role: "Sacred Space" in Corporate Takeovers. 80 Tex. L. Rev. 261-326 (2001).2001年:1.Black, Bernard S. The legal and institutional preconditions for strong securities markets. 48 UCLA L. Rev. 781-855 (2001).2.Coates, John C. IV. Takeover defenses in the shadow of the pill: a critique of the scientific evidence. 79 Tex. L. Rev. 271-382 (2000).3.Coates, John C. IV and Guhan Subramanian. A buy-side model of M&A lockups: theory and evidence. 53 Stan. L. Rev. 307-396 (2000).4.Coffee, John C., Jr. The rise of dispersed ownership: the roles of law and the state in the separation of ownership and control. 111 Y ale L.J. 1-82 (2001).5.Choi, Stephen J. The unfounded fear of Regulation S: empirical evidence on offshore securities offerings. 50 Duke L.J. 663-751 (2000).6.Daines, Robert and Michael Klausner. Do IPO charters maximize firm value? Antitakeover protection in IPOs. 17 J.L. Econ. & Org. 83-120 (2001).7.Hansmann, Henry and Reinier Kraakman. The essential role of organizational law. 110 Y ale L.J. 387-440 (2000).ngevoort, Donald C. The human nature of corporate boards: law, norms, and the unintended consequences of independence and accountability. 89 Geo. L.J. 797-832 (2001).9.Mahoney, Paul G. The political economy of the Securities Act of 1933. 30 J. Legal Stud. 1-31 (2001).10.Roe, Mark J. Political preconditions to separating ownership from corporate control. 53 Stan. L. Rev. 539-606 (2000).11.Romano, Roberta. Less is more: making institutional investor activism a valuable mechanism of corporate governance. 18 Y ale J. on Reg. 174-251 (2001).2000年:1.Bratton, William W. and Joseph A. McCahery. Comparative Corporate Governance and the Theory of the Firm: The Case Against Global Cross Reference. 38 Colum. J. Transnat’l L. 213-297 (1999).2.Coates, John C. IV. Empirical Evidence on Structural Takeover Defenses: Where Do We Stand?54 U. Miami L. Rev. 783-797 (2000).3.Coffee, John C., Jr. Privatization and Corporate Governance: The Lessons from Securities Market Failure. 25 J. Corp. L. 1-39 (1999).4.Fisch, Jill E. The Peculiar Role of the Delaware Courts in the Competition for Corporate Charters. 68 U. Cin. L. Rev. 1061-1100 (2000).5.Fox, Merritt B. Retained Mandatory Securities Disclosure: Why Issuer Choice Is Not Investor Empowerment. 85 V a. L. Rev. 1335-1419 (1999).6.Fried, Jesse M. Insider Signaling and Insider Trading with Repurchase Tender Offers. 67 U. Chi. L. Rev. 421-477 (2000).7.Gulati, G. Mitu, William A. Klein and Eric M. Zolt. Connected Contracts. 47 UCLA L. Rev. 887-948 (2000).8.Hu, Henry T.C. Faith and Magic: Investor Beliefs and Government Neutrality. 78 Tex. L. Rev. 777-884 (2000).9.Moll, Douglas K. Shareholder Oppression in Close Corporations: The Unanswered Question of Perspective. 53 V and. L. Rev. 749-827 (2000).10.Schizer, David M. Executives and Hedging: The Fragile Legal Foundation of Incentive Compatibility. 100 Colum. L. Rev. 440-504 (2000).11.Smith, Thomas A. The Efficient Norm for Corporate Law: A Neotraditional Interpretation of Fiduciary Duty. 98 Mich. L. Rev. 214-268 (1999).12.Thomas, Randall S. and Kenneth J. Martin. The Determinants of Shareholder V oting on Stock Option Plans. 35 Wake Forest L. Rev. 31-81 (2000).13.Thompson, Robert B. Preemption and Federalism in Corporate Governance: Protecting Shareholder Rights to V ote, Sell, and Sue. 62 Law & Contemp. Probs. 215-242 (1999).1999年(以第一作者姓名音序为序):1.Bankman, Joseph and Ronald J. Gilson. Why Start-ups? 51 Stan. L. Rev. 289-308 (1999).2.Bhagat, Sanjai and Bernard Black. The Uncertain Relationship Between Board Composition and Firm Performance. 54 Bus. Law. 921-963 (1999).3.Blair, Margaret M. and Lynn A. Stout. A Team Production Theory of Corporate Law. 85 V a. L. Rev. 247-328 (1999).4.Coates, John C., IV. “Fair V alue” As an A voidable Rule of Corporate Law: Minority Discounts in Conflict Transactions. 147 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1251-1359 (1999).5.Coffee, John C., Jr. The Future as History: The Prospects for Global Convergence in Corporate Governance and Its Implications. 93 Nw. U. L. Rev. 641-707 (1999).6.Eisenberg, Melvin A. Corporate Law and Social Norms. 99 Colum. L. Rev. 1253-1292 (1999).7.Hamermesh, Lawrence A. Corporate Democracy and Stockholder-Adopted By-laws: Taking Back the Street? 73 Tul. L. Rev. 409-495 (1998).8.Krawiec, Kimberly D. Derivatives, Corporate Hedging, and Shareholder Wealth: Modigliani-Miller Forty Y ears Later. 1998 U. Ill. L. Rev. 1039-1104.ngevoort, Donald C. Rereading Cady, Roberts: The Ideology and Practice of Insider Trading Regulation. 99 Colum. L. Rev. 1319-1343 (1999).ngevoort, Donald C. Half-Truths: Protecting Mistaken Inferences By Investors and Others.52 Stan. L. Rev. 87-125 (1999).11.Talley, Eric. Turning Servile Opportunities to Gold: A Strategic Analysis of the Corporate Opportunities Doctrine. 108 Y ale L.J. 277-375 (1998).12.Williams, Cynthia A. The Securities and Exchange Commission and Corporate Social Transparency. 112 Harv. L. Rev. 1197-1311 (1999).1998年:1.Carney, William J., The Production of Corporate Law, 71 S. Cal. L. Rev. 715-780 (1998).2.Choi, Stephen, Market Lessons for Gatekeepers, 92 Nw. U. L. Rev. 916-966 (1998).3.Coffee, John C., Jr., Brave New World?: The Impact(s) of the Internet on Modern Securities Regulation. 52 Bus. Law. 1195-1233 (1997).ngevoort, Donald C., Organized Illusions: A Behavioral Theory of Why Corporations Mislead Stock Market Investors (and Cause Other Social Harms). 146 U. Pa. L. Rev. 101-172 (1997).ngevoort, Donald C., The Epistemology of Corporate-Securities Lawyering: Beliefs, Biases and Organizational Behavior. 63 Brook. L. Rev. 629-676 (1997).6.Mann, Ronald J. The Role of Secured Credit in Small-Business Lending. 86 Geo. L.J. 1-44 (1997).haupt, Curtis J., Property Rights in Firms. 84 V a. L. Rev. 1145-1194 (1998).8.Rock, Edward B., Saints and Sinners: How Does Delaware Corporate Law Work? 44 UCLA L. Rev. 1009-1107 (1997).9.Romano, Roberta, Empowering Investors: A Market Approach to Securities Regulation. 107 Y ale L.J. 2359-2430 (1998).10.Schwab, Stewart J. and Randall S. Thomas, Realigning Corporate Governance: Shareholder Activism by Labor Unions. 96 Mich. L. Rev. 1018-1094 (1998).11.Skeel, David A., Jr., An Evolutionary Theory of Corporate Law and Corporate Bankruptcy. 51 V and. L. Rev. 1325-1398 (1998).12.Thomas, Randall S. and Martin, Kenneth J., Should Labor Be Allowed to Make Shareholder Proposals? 73 Wash. L. Rev. 41-80 (1998).1997年:1.Alexander, Janet Cooper, Rethinking Damages in Securities Class Actions, 48 Stan. L. Rev. 1487-1537 (1996).2.Arlen, Jennifer and Kraakman, Reinier, Controlling Corporate Misconduct: An Analysis of Corporate Liability Regimes, 72 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 687-779 (1997).3.Brudney, Victor, Contract and Fiduciary Duty in Corporate Law, 38 B.C. L. Rev. 595-665 (1997).4.Carney, William J., The Political Economy of Competition for Corporate Charters, 26 J. Legal Stud. 303-329 (1997).5.Choi, Stephen J., Company Registration: Toward a Status-Based Antifraud Regime, 64 U. Chi. L. Rev. 567-651 (1997).6.Fox, Merritt B., Securities Disclosure in a Globalizing Market: Who Should Regulate Whom. 95 Mich. L. Rev. 2498-2632 (1997).7.Kahan, Marcel and Klausner, Michael, Lockups and the Market for Corporate Control, 48 Stan. L. Rev. 1539-1571 (1996).8.Mahoney, Paul G., The Exchange as Regulator, 83 V a. L. Rev. 1453-1500 (1997).haupt, Curtis J., The Market for Innovation in the United States and Japan: V enture Capital and the Comparative Corporate Governance Debate, 91 Nw. U.L. Rev. 865-898 (1997).10.Skeel, David A., Jr., The Unanimity Norm in Delaware Corporate Law, 83 V a. L. Rev. 127-175 (1997).1996年:1.Black, Bernard and Reinier Kraakman A Self-Enforcing Model of Corporate Law, 109 Harv. L. Rev. 1911 (1996)2.Gilson, Ronald J. Corporate Governance and Economic Efficiency: When Do Institutions Matter?, 74 Wash. U. L.Q. 327 (1996)3. Hu, Henry T.C. Hedging Expectations: "Derivative Reality" and the Law and Finance of the Corporate Objective, 21 J. Corp. L. 3 (1995)4.Kahan, Marcel & Michael Klausner Path Dependence in Corporate Contracting: Increasing Returns, Herd Behavior and Cognitive Biases, 74 Wash. U. L.Q. 347 (1996)5.Kitch, Edmund W. The Theory and Practice of Securities Disclosure, 61 Brooklyn L. Rev. 763 (1995)ngevoort, Donald C. Selling Hope, Selling Risk: Some Lessons for Law From Behavioral Economics About Stockbrokers and Sophisticated Customers, 84 Cal. L. Rev. 627 (1996)7.Lin, Laura The Effectiveness of Outside Directors as a Corporate Governance Mechanism: Theories and Evidence, 90 Nw. U.L. Rev. 898 (1996)lstein, Ira M. The Professional Board, 50 Bus. Law 1427 (1995)9.Thompson, Robert B. Exit, Liquidity, and Majority Rule: Appraisal's Role in Corporate Law, 84 Geo. L.J. 1 (1995)10.Triantis, George G. and Daniels, Ronald J. The Role of Debt in Interactive Corporate Governance. 83 Cal. L. Rev. 1073 (1995)1995年:公司法:1.Arlen, Jennifer and Deborah M. Weiss A Political Theory of Corporate Taxation,. 105 Y ale L.J. 325-391 (1995).2.Elson, Charles M. The Duty of Care, Compensation, and Stock Ownership, 63 U. Cin. L. Rev. 649 (1995).3.Hu, Henry T.C. Heeding Expectations: "Derivative Reality" and the Law and Finance of the Corporate Objective, 73 Tex. L. Rev. 985-1040 (1995).4.Kahan, Marcel The Qualified Case Against Mandatory Terms in Bonds, 89 Nw. U.L. Rev. 565-622 (1995).5.Klausner, Michael Corporations, Corporate Law, and Networks of Contracts, 81 V a. L. Rev. 757-852 (1995).6.Mitchell, Lawrence E. Cooperation and Constraint in the Modern Corporation: An Inquiry Into the Causes of Corporate Immorality, 73 Tex. L. Rev. 477-537 (1995).7.Siegel, Mary Back to the Future: Appraisal Rights in the Twenty-First Century, 32 Harv. J. on Legis. 79-143 (1995).证券法:1.Grundfest, Joseph A. Why Disimply? 108 Harv. L. Rev. 727-747 (1995).2.Lev, Baruch and Meiring de V illiers Stock Price Crashes and 10b-5 Damages: A Legal Economic, and Policy Analysis, 47 Stan. L. Rev. 7-37 (1994).3.Mahoney, Paul G. Mandatory Disclosure as a Solution to Agency Problems, 62 U. Chi. L. Rev. 1047-1112 (1995).4.Seligman, Joel The Merits Do Matter, 108 Harv. L. Rev. 438 (1994).5.Seligman, Joel The Obsolescence of Wall Street: A Contextual Approach to the Evolving Structure of Federal Securities Regulation, 93 Mich. L. Rev. 649-702 (1995).6.Stout, Lynn A. Are Stock Markets Costly Casinos? Disagreement, Mark Failure, and Securities Regulation, 81 V a. L. Rev. 611 (1995).7.Weiss, Elliott J. and John S. Beckerman Let the Money Do the Monitoring: How Institutional Investors Can Reduce Agency Costs in Securities Class Actions, 104 Y ale L.J. 2053-2127 (1995).1994年:公司法:1.Fraidin, Stephen and Hanson, Jon D. Toward Unlocking Lockups, 103 Y ale L.J. 1739-1834 (1994)2.Gordon, Jeffrey N. Institutions as Relational Investors: A New Look at Cumulative V oting, 94 Colum. L. Rev. 124-192 (1994)3.Karpoff, Jonathan M., and Lott, John R., Jr. The Reputational Penalty Firms Bear From Committing Criminal Fraud, 36 J.L. & Econ. 757-802 (1993)4.Kraakman, Reiner, Park, Hyun, and Shavell, Steven When Are Shareholder Suits in Shareholder Interests?, 82 Geo. L.J. 1733-1775 (1994)5.Mitchell, Lawrence E. Fairness and Trust in Corporate Law, 43 Duke L.J. 425- 491 (1993)6.Oesterle, Dale A. and Palmiter, Alan R. Judicial Schizophrenia in Shareholder V oting Cases, 79 Iowa L. Rev. 485-583 (1994)7. Pound, John The Rise of the Political Model of Corporate Governance and Corporate Control, 68 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1003-1071 (1993)8.Skeel, David A., Jr. Rethinking the Line Between Corporate Law and Corporate Bankruptcy, 72 Tex. L. Rev. 471-557 (1994)9.Thompson, Robert B. Unpacking Limited Liability: Direct and V icarious Liability of Corporate Participants for Torts of the Enterprise, 47 V and. L. Rev. 1-41 (1994)证券法:1.Alexander, Janet Cooper The V alue of Bad News in Securities Class Actions, 41 UCLA L.Rev. 1421-1469 (1994)2.Bainbridge, Stephen M. Insider Trading Under the Restatement of the Law Governing Lawyers, 19 J. Corp. L. 1-40 (1993)3.Black, Bernard S. and Coffee, John C. Jr. Hail Britannia?: Institutional Investor Behavior Under Limited Regulation, 92 Mich. L. Rev. 1997-2087 (1994)4.Booth, Richard A. The Efficient Market, portfolio Theory, and the Downward Sloping Demand Hypothesis, 68 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1187-1212 (1993)5.Coffee, John C., Jr. The SEC and the Institutional Investor: A Half-Time Report, 15 Cardozo L. Rev 837-907 (1994)6.Fox, Merritt B. Insider Trading Deterrence V ersus Managerial Incentives: A Unified Theory of Section 16(b), 92 Mich. L. Rev. 2088-2203 (1994)7.Grundfest, Joseph A. Disimplying Private Rights of Action Under the Federal Securities Laws: The Commission's Authority, 107 Harv. L. Rev. 961-1024 (1994)8.Macey, Jonathan R. Administrative Agency Obsolescence and Interest Group Formation: A Case Study of the SEC at Sixty, 15 Cardozo L. Rev. 909-949 (1994)9.Rock, Edward B. Controlling the Dark Side of Relational Investing, 15 Cardozo L. Rev. 987-1031 (1994)。

210878169_ESG_表现与企业经营风险

价值工程0引言ESG 是指经济主体从环境(Environment )、社会(Social )和治理(Governance )三个方面对企业进行综合评价的方法。

20世纪80年代以来,随着企业管理者和投资者利益冲突不断加剧,以及生态环境日益遭到破坏,越来越多的企业开始意识到在制定经营决策时要综合考虑社会责任和环境责任[1]。

环境、社会和公司治理为主的责任投资理念和可持续发展理念逐渐得到人们的关注和认可。

1992年,联合国环境规划署提出,希望金融机构在进行投资决策时考虑环境、社会和公司治理因素。

自此以后,国际上关于ESG 的关注持续升温,各类组织和机构提出一系列ESG 评价指标,逐渐形成完整的ESG 评价体系[2]。

由于国内ESG 投资还处于初期发展阶段,研究内容相对较少,但是ESG 责任中所包含的环境责任、社会责任和公司治理方面的研究如火如荼。

目前,投资者在投资决策时把公司ESG 表现作为一个重要的标准之一。

而公司对ESG 活动进行投入,会降低经营过程中的不确定性,缓解融资约束[3],提高风险抵御能力。

本文在回顾和借鉴国内外研究成果的前提下,试图找出ESG 表现是否会影响企业经营风险,以及如何影响企业经营风险?1文献综述近年来,ESG 表现得到了政府和相关投资者的重视,使得企业越来越重视社会责任的承担和履行,ESG 表现成为衡量企业绩效的重要标准之一。

目前,关于ESG 表现的经济后果主要体现在以下几个方面。

在企业绩效方面,袁业虎等(2021)[4]研究发现,媒体关注度高的企业,ESG 表现越好,其企业绩效水平越高。

但是,Ruan 等(2020)[5]研究发现,ESG 表现与公司绩效是负相关的。

在企业价值方面,何音等(2019)[6]研究发现,企业积极履行一定的社会责任,有利于提高顾客对企业的认同感,进而提升企业价值。

根据Li 等(2018)[7]研究发现,上市公司ESG 披露水平越高,越有利于提升公司价值。

文献导读