A Bibliography of Publications about the GNU (Gnu is Not Unix) System

Gay and Lesbian Language

Annu.Rev.Anthropol.2000.29:243–85Copyright c2000by Annual Reviews.All rights reserved G AY AND L ESBIAN L ANGUAGEDon Kulick Department of Social Anthropology,Stockholm University,10691Stockholm,Sweden;e-mail:kulick@socant.su.seKey Words homosexuality,sexuality,desire s Abstract The past two decades have witnessed a minor explosion in publications dealing with the ways in which gay men and lesbians use language.In fact,though,work on the topic has been appearing in several disciplines (philology,linguistics,women’s studies,anthropology,and speech communication)since the 1940s.This review charts the history of research on “gay and lesbian language,”detailing earlier concerns and showing how work of the 1980s and 1990s both grows out of and differs from previous scholarship.Through a critical analysis of key assumptions that guide research,this review argues that gay and lesbian language does not and cannot exist in the way it is widely imagined to do.The review concludes with the suggestion that scholars abandon the search for gay and lesbian language and move on to develop and refine concepts that permit the study of language and sexuality,and language and desire.INTRODUCTION A recent anthology on postmodern sexualities,entitled (probably inevitably)Po-mosexuals (Queen &Schimel 1997),begins with a remark on language.The editors recall that at the 1996Lambda Literary Awards ceremony,a lesbian comic suggested that a new term was needed to replace the “lengthy and cumbersome yet politically correct tag currently used by and for our community:‘Lesbian,Gay,Bisexual,Transgendered,and Friends’”.The word the comic offered was “Sodomites.”Why not?the editors wonder:“[i]t’s certainly more succinct,and is actually less glib than it seems upon first reflection,for that is what most people assume LGBT&F actually means,anyway”(Queen &Schimel 1997:19,emphasis in original).What to collectively call people whose sexual and gendered practices and/or identities fall beyond the bounds of normative heterosexuality is an unavoidable and ultimately unresolvable problem.For a very short while,in the late 1960s,“gay”seemed to work.But that unifying moment passed quickly,as lesbians protested that “gay”both elided women and eclipsed their commitment to feminism (Johnson 1975,Penelope &Wolfe 1979:1–2,Shapiro 1990,Stanley 1974:391,0084-6570/00/1015-0243$14.00243A n n u . R e v . A n t h r o p o l . 2000.29:243-285. D o w n l o a d e d f r o m w w w .a n n u a l r e v i e w s .o r g A c c e s s p r o v i d e d b y T s i n g h u a U n i v e r s i t y o n 05/10/15. F o r p e r s o n a l u s e o n l y .244KULICKWhite 1980:239).Then,in the early 1990s,it seemed that “queer”might do the trick.Queer,however,has never been accepted by a large number of the people it was resurrected to embrace,and in activist contexts,the word has lately been turning up as just one more identity to be tacked on to the end of an already lengthy list.For example,the latest acronym,which I encountered for the first time at a queer studies conference in New York in April 1999,was LGBTTSQ.When I turned to the stylishly black-clad lesbian sitting beside me and inquired what this intriguing,sandwich-sounding clot of letters might mean,I was informed (in that tart,dismissive tone that New Yorkers use to convey their opinion that the addressee must have just crawled out from under some provincial rock)that it signified “Lesbian,Gay,Bisexual,Transgendered,Two-Spirit,Queer,or Questioning.”The coinage,dissemination,political efficacy,and affective appeal of acronyms like this deserve a study in their own right.What they point to is continued concern among sexual and gender-rights activists over which identity categories are to be named and foregrounded in their movement and their discussions.These are not trivial issues:A theme running through much gay,lesbian,and transgendered writings on language is that naming confers existence.This insistence appears in everything from coming-out narratives [“I have recalled my utter isolation at sixteen,when I looked up Lesbian in the dictionary,having no one to ask about such things,terrified,elated,painfully self aware,grateful it was there at all”(Grahn 1984:xii)],to AIDS activism [“The most momentous semantic battlefield yet fought in the AIDS war concerned the naming of the so-called AIDS virus”(Callen 1990:134)],to high philosophical treatises [“Only by occupying—being occupied by—the injurious term can I resist and oppose it”(Butler 1997b:104)].Zimmerman (1985:259–60)states the issue starkly (see also Nogle 1981:270–71,Penelope et al 1978):[C]ontemporary lesbian feminists postulate lesbian oppression as a mutilation of censoriousness curable by language.Lesbians do share the institutional oppression of all women and the denial of civil rights with gay men.But what lesbian feminists identify as the particular,unique oppression of lesbians—rightly or wrongly—is speechlessness,invisibility,inauthenticity.Lesbian resistance lies in correct naming;thus our powerflows from language,vision,and culture....Contemporary lesbian feminism is thus primarily a politics of language and consciousness.This kind of deep investment in language and naming means that it is necessary to tread gingerly when deciding what to call a review like this one,or when consid-ering what name to use to collectively designate the kinds of nonheteronormative sexual practices and identities that are the topic of discussion here.However,be-cause no all-encompassing appellation currently exists,and because no acronym (short,perhaps,of one consisting of the entire alphabet)can ever hope to keep all possible sexual and gendered identities equally in play and at the fore,I am forced to admit defeat from the start and apologize to all the Ls,Gs,Bs,Ts,TSs,Qs,Fs,and others who will not specifically be invoked every time I refer here,for theA n n u . R e v . A n t h r o p o l . 2000.29:243-285. D o w n l o a d e d f r o m w w w .a n n u a l r e v i e w s .o r g A c c e s s p r o v i d e d b y T s i n g h u a U n i v e r s i t y o n 05/10/15. F o r p e r s o n a l u s e o n l y .GAY AND LESBIAN LANGUAGE 245sake of simplicity,to “queer language.”As far as the title of this article is con-cerned,my inclination was to call it “Language and Sexuality,”because the unique contribution of the literature I discuss has been to draw attention to the fact that there is a relationship between language and sexuality (something that has largely been ignored or missed in the voluminous literature on language and gender).In the end,though,I decided to preserve the title assigned me by the editors of this Annual Review .1Although dry and in some senses “noninclusive,”at least it has the advantage of clearly stating what kind of work is summarized here.So this essay reviews work on gay and lesbian language.Twenty years ago,Hayes (1978)observed that the “sociolinguistic study of the language behavior of lesbians and gay men is hampered...[in part because]important essays have ap-peared in small circulation,ephemeral,or out-of-print journals”(p.201).Hayes believed that research could be aided by providing summaries of some of this difficult-to-obtain material [and his annotated bibliography (Hayes 1978,1979)remains a useful resource even today].My own view is that no academic dis-cussion can flourish if the material under debate is available to only a handful of scholars;on the contrary,the message conveyed by such discussions becomes one of exclusivity and arcaneness.In the interest of extending and opening up scholar-ship,this article therefore considers only published and relatively accessible work.This means that the abundance of unpublished conference papers listed in Ward’s (2000)invaluable bibliography is not discussed here.I also do not include papers printed in conference proceedings,such as the Berkeley Women and Language Conference,or the SALSA (Symposium about Language and Society at Austin)conference,because those proceedings are not widely distributed,and they are of-ten virtually impossible to obtain,especially outside the United States.Also,with few exceptions,neither do I consider literary treatments of the oeuvres of queer authors nor queer readings of literary,social,or cultural texts,even though many of those analyses have been foundational for the establishment and consolidation of queer theory (e.g.Butler 1990,1997a;Dollimore 1991;Doty 1993;Sedgwick 1985,1990).Instead,the focus here is on research that investigates how gays and lesbians talk.How has “gay and lesbian language”been theorized,documented,and analyzed?What are the achievements and limitations of these analyses?Before proceeding,however,a further word of contextualization:I agreed to write this text under the assumption that the amount of literature on this topic was small.I am clearly not alone in that belief:Romaine’s (1999)new textbook on language and gender devotes a total of three pages (out of 355)to a discussion of queer language;and Haiman’s (1998)recent book on sarcasm has a two-page section on “Gayspeak,”in which he declares that lack of research forces him to turn to The Boys in the Band (God help us)for examples (pp.95–97).A cutting-edge 1Actually,that title was “Gay,Lesbian,and Transgendered Language,”but because the issues raised by the language of transgendered individuals are somewhat different from those I wanted to emphasize here,I decided to review the linguistic and anthropological literature on transgendered language separately (Kulick 1999).A n n u . R e v . A n t h r o p o l . 2000.29:243-285. D o w n l o a d e d f r o m w w w .a n n u a l r e v i e w s .o r g A c c e s s p r o v i d e d b y T s i n g h u a U n i v e r s i t y o n 05/10/15. F o r p e r s o n a l u s e o n l y .246KULICKintroduction to lesbian and gay studies has chapters on everything from “queer geography”to “class,”but nothing on linguistics (Medhurst &Munt 1997);and textbooks by Duranti (1997)and Foley (1997)on anthropological linguistics and linguistic anthropology have not a word to say about gay,lesbian,or transgendered language.Even recent texts on “Gay English”and queer linguistics mention only a handful of references (Leap 1996,Livia &Hall 1997a).With those kinds of works in mind,imagine my surprise,then,when the literature searches I did for this article turned up almost 200titles.At that point,I felt compelled to ask myself why there seems to be such a widespread belief that there is so little research on gay and lesbian language?The obvious answer is because research on gay and lesbian language has had virtually no impact whatsoever on any branch of sociolinguistics or linguistic anthropology—even those dealing explicitly with language and gender,as is ev-idenced by the wan three pages in Romaine’s book [a recent exception that does discuss this literature in a wider context is Cameron (1998)].One might inevitably wonder if this lack of impact is somehow related to structures of discrimination in an academy that,until recently,actively discouraged any research on homosexu-ality that did not explicitly see it as deviance (Bolton 1995a,Lewin &Leap 1996).Another reason could be the one mentioned above,that work on gay and lesbian language has often appeared in obscure publications.Or it could be because work on this topic has no real disciplinary home.It is done by philologists,phoneti-cians,linguists,anthropologists,speech communication specialists,researchers in women’s studies,and others,many of whom seem to have little contact with the work published outside their own discipline.Finally,much of the research on gay and lesbian language consists of lists of in-group terms,discussion of terms for “homosexual,”debates about the pros and cons of words like “gay”and “queer,”or possible etymologies of words like “sod,”“dyke,”or “closet.”This is interesting information,but it is hardly the stuff from which pathbreaking theoriz-ing is likely to arise (Aman 1986/1987;Ashley 1979,1980,1982,1987;Bolton 1995b;Boswell 1993;Brownworth 1994;Cawqua 1982;Chesebro 1981b;Diallo &Krumholtz 1994;Dynes 1985;Fessler &Rauch 1997;Grahn 1984;Johansson 1981;Lazerson 1981;Lee 1981;Riordon 1978;Roberts 1979a,b;Shapiro 1988;Spears 1985;Stone 1981).Although all those reasons for mainstream lack of interest in work on queer language are possible and even likely,in this review I pursue a different line of thought:namely,that research on gay and lesbian language has had little impact because it is plagued by serious conceptual difficulties.One problem to which I return repeatedly is the belief in much work that gay and lesbian language is somehow grounded in gay and lesbian identities and instantiated in the speech of people who self-identify as gay and lesbian.This assumption confuses symbolic and empirical categories,it reduces sexuality to sexual identity,and it steers re-search away from examining the ways in which the characteristics seen as queer are linguistic resources available to everybody to use,regardless of their sexual orientation.In addition,a marked feature of much of the literature is its apparent A n n u . R e v . A n t h r o p o l . 2000.29:243-285. D o w n l o a d e d f r o m w w w .a n n u a l r e v i e w s .o r g A c c e s s p r o v i d e d b y T s i n g h u a U n i v e r s i t y o n 05/10/15. F o r p e r s o n a l u s e o n l y .GAY AND LESBIAN LANGUAGE 247unfamiliarity with well-established linguistic disciplines and methods of analysis,such as Conversation Analysis,discourse analysis,and pragmatics.That the Ency-clopedia of Homosexuality could refer to sociolinguistics,in 1990,as “an emerging discipline”(Dynes 1990:676)is indicative of the lag that exists in much of the lit-erature between linguistic and cultural theory and the work that is done on queer language.I structure this text as a critical review,with an equal emphasis on both those words.I also structure it as an argument.This essay makes a strong claim,namely that the object under focus here does not,in fact,exist.There is no such thing as gay or lesbian nguage,of course,is used by individuals who self-identify as gay and lesbian,and I review a number of dimensions of this language use,including vocabulary and the use by males of grammatically and semantically feminine forms to refer to other males.However,to say that some self-identified gay men and lesbians may sometimes use language in certain ways in certain contexts is not the same thing as saying that there is a gay or lesbian language.My argument is that the lasting contribution of research on gay and lesbian language is that it has alerted us to a relationship between language and sexuality,and it has prepared the ground for what could be an extremely productive exploration of language and desire.By having a clear sense of the limitations of the research on gay and lesbian language,and by pursuing some of its leads and building on some of its insights,future scholarship should be able to move away from the search for the linguistic correlates of contemporary identity categories and turn its attention to the ways in which language is bound up with and conveys desire.THE LA VENDER LEXICON In 1995,the anthropologist and linguist William Leap edited a book that he called Beyond the Lavender Lexicon .This title was chosen,Leap explains in his introduc-tory chapter,because “there is more to lesbian and gay communication than coded words with special meanings,and more to lesbian and gay linguistic research than the compilation of dictionaries or the tracing of single-word etymologies”(Leap 1995a:xvii–xviii).In expressing his desire to move “beyond”this kind of work,Leap succinctly summarized the overwhelming bulk of research that had been conducted on queer language since the 1940s.Until the 1980s,research on gay and lesbian language was pretty much syn-onymous with lists of and debates about the in-group terms used by male homo-sexuals.The reasons behind the gathering of these lists are diverse.In some cases the motivation seems to have been part of a civilizing crusade:“I believe that for the perfectly civilized person,obscenity would not exist,”declared Read (1977[1935]:16),in the introduction to his study of men’s room graffiti.[Ashley’s (1979,1980,1982,1987)book-length series of articles are more recent examples.]In others,there may have been a desire to crack a mysterious code—as late as 1949,respected academics like the Chicago sociologist E.W.Burgess could assert that A n n u . R e v . A n t h r o p o l . 2000.29:243-285. D o w n l o a d e d f r o m w w w .a n n u a l r e v i e w s .o r g A c c e s s p r o v i d e d b y T s i n g h u a U n i v e r s i t y o n 05/10/15. F o r p e r s o n a l u s e o n l y .248KULICKthe urban “homosexual world has its own language,incomprehensible to out-siders”(Burgess 1949:234).For a long time,there was also a philological interest in documenting the “lingo”of “subcultural”or “underworld”groups,like hobos,prostitutes,and homosexuals [see the dictionaries listed in Legman (1941:1156)and Stanley (1974:Note 1)].Finally,more sociologically oriented scholars have examined gay argot in order to be able to say something about “the sociocultural qualities of the group”that uses the words (Sonenschein 1969:281).Perhaps the earliest documentation in English of words that must have been used by at least some homosexual men was compiled by Allen Walker Read,a scholar who later became a professor of English at Columbia University.In the summer of 1928,Read [1977(1935)]embarked on an “extensive sight-seeing trip”throughout the Western United States and Canada,during which he took detailed notes on the writing that appeared in public rest-room walls.Read’s interest in this “folk epigraphy”was scientific:“I can only plead,”he pleaded,“that the reader believe my sincerity when I say that I present this study solely as an honourable attempt to throw light on a field of linguistics where light has long been needed”(p.29).Worried that his scientific study of men’s room graffiti might fall into the hands of “people to whom it would be nothing more than pornography”(p.28),Read printed the study privately in Paris in a limited edition of 75copies and had the cover embossed with an austere warning:“Circulation restricted to students of linguistics,folk-lore,abnormal psychology,and allied branches of social science.”Read has nothing to say about homosexual language in his book,but many of his entries (such as “When will you meet me and suck my prick.I suck them every day,”or “I suck cocks for fun”)have clear homosexual themes.As Butters (1989:2)points out,Read’s work “sheds light on a number of linguistic issues;for example:the absence of the word gay from any of Read’s collected graffiti tends to confirm the general belief among etymologists that the term did not exist in its popular meaning of “homosexual”before the 1950s.”2The first published English-language lexicon of “the language of homosexual-ity”was compiled by the folklorist and student of literary erotica Gershon Legman.Legman’s (1941)glossary appears as the final appendix in the first edition of a two-volume medical study of homosexuality [Henry (1941)—it was removed from later editions].The list contains 329items,139of which are identified as exclu-sively homosexual in use.As Doyle (1982:75)notes in his discussion of this text,some of the words on Legman’s list (such as “drag,”“straight,”and “basket”)have not only survived,but have passed into more general use.Others,such as the delightful “church-mouse”[“a homosexual who frequents churches and cathe-drals in order to grope or cruise the young men there”(Legman 1941,emphasis in original),or the curious “white-liver”(“a male or female homosexual who is completely indifferent to the opposite sex”),may well be extinct.2Butters’s remark seems refuted by Cory’s (1951)assertion that “gay is used throughout the United States and Canada [to mean homosexual]”,and “by the nineteen-thirties [gay]was the most common word in use among homosexuals themselves”(pp.110,107).Chauncey’s (1994:19)research on the origins and spread of the word “gay”supports Cory’s claims.A n n u . R e v . A n t h r o p o l . 2000.29:243-285. D o w n l o a d e d f r o m w w w .a n n u a l r e v i e w s .o r g A c c e s s p r o v i d e d b y T s i n g h u a U n i v e r s i t y o n 05/10/15. F o r p e r s o n a l u s e o n l y .GAY AND LESBIAN LANGUAGE 249Although Legman gives careful definitions of the words he lists,he had little to say about “the language of homosexuality,”except to note that male homosexuals frequently “substitut[e]feminine pronouns and titles for properly masculine ones”(1941:1155),and that lesbians do not have an extensive in-group vocabulary.3The brevity of Legman’s (1941)discussion means that the first real analysis of homosexual language appears not to have occurred until 1951,when Donald Cory [a pseudonym of Edward Sagarin (Hayes 1978:203)]included a 10-page chap-ter on language in his book (Cory 1951:103–13).Cory’s main argument about what he called “homosexual ‘cantargot’”was that it had been created because homosexuals had “a burning need”(p.106)for words that did not denote them pejoratively (for more recent instances of this viewpoint,see Karlen 1971:517–18,Zeve 1993:35).Hence,his discussion focused on words that homosexuals invented to call one another,particularly the word “gay”.Cory believed that words like “gay”were positive,in that they transcended social stereotypes,and in doing so,they allowed in-group conversation to be “free and unhampered”(1951:113).Ul-timately,however,homosexual slang was an attenuated slang;one that had “failed to develop in a natural way”(p.103)because it could only be used in secre-tive in-group communication,due to societal taboos on discussing homosexuality at all.After Cory’s text,little was published in English until the 1960s,when Cory &LeRoy (1963)included an 89-word lexicon as an appendix to their book,and when several other word lists were printed extremely obscurely.4The 1960s also saw the publication of what appears to be the first lexicon of words used by lesbians:Giallombardo’s (1966:204–13)298-word glossary of terms,many of them referring to lesbian sexuality and relationships,used by inmates in a women’s 3Legman (1941:1156)offers two explanations for this:the first having to do with “[t]he tradition of gentlemanly restraint among lesbians [that]stifles the flamboyance and con-versational cynicism in sexual matters that slang coinage requires”;the second being that “[l]esbian attachments are sufficiently feminine to be more often emotional than simply sexual”—hence,an extensive sexual vocabulary would be superfluous.Penelope &Wolfe (1979:11)suggest other reasons for the absence of an elaborate lesbian in-group vocabulary.They argue that such an absence is predictable,given that,in their opinion,the vocabulary ofmale homosexuals (and of males in general)is misogynist.“How would a group of women gain a satisfactorily expressive terminology if the only available terms were derogatory toward women?”they ask.In addition,they note that lesbians “have been socially and historically invisible...and isolated from each other as a consequence,and have never had a cohesive community in which a Lesbian aesthetic could have developed”(1979:12).4A mimeographed pamphlet,entitled “The Gay Girl’s Guide to the U.S.and Western World,”described as consisting of “campy definitions of coterie terms from the male homosexual world of the post-World War II period;includes French,German and Russian terms”(Dynes 1985:156,emphasis in original)has appeared in several editions and seems to have been published as early as 1949(Hayes 1978:203).The names of the three authors of the text are pseudonyms,and no publisher is given.I have been unable to locate it.I have also been unable to locate two of the lists mentioned by Sonenschein (1969),Hayes (1978),and Dynes (1985);namely Guild (1965)and Strait (1964).A n n u . R e v . A n t h r o p o l . 2000.29:243-285. D o w n l o a d e d f r o m w w w .a n n u a l r e v i e w s .o r g A c c e s s p r o v i d e d b y T s i n g h u a U n i v e r s i t y o n 05/10/15. F o r p e r s o n a l u s e o n l y .250KULICKprison.Furthermore,it was not until the 1960s that the study of homosexual slang began to be conducted by researchers who were not philologists or amateur social scientists,like Cory.Giallombardo,for example,was a trained sociologist.And anticipating Families We Choose (Weston 1991)by more than 20years,she devoted an entire chapter to how an elaborate system of named kin relationships organized social and sexual relationships between the female prisoners she studied.Another early analysis of the social functions of gay slang was anthropologist Sonenschein’s (1969)article.Sonenschein argued that gay slang is not primarily about isolation or secrecy,as previous writers had suggested (e.g.Cory 1951;also recall Burgess’s assertion that the language of homosexuals was “incomprehensible to outsiders”).Instead,homosexual slang serves communicative functions,the most important of which is to “reinforce group cohesiveness and reflect common interests,problems,and needs of the population”(Sonenschein 1969:289).In light of later work that came to make assumptions about the existence of a gay or lesbian speech community and stress the “authenticity”of lesbian and gay speech (Leap 1996,Moonwomon 1995),it is interesting to note that early claims like Sonenschein’s about the supposed group cohesiveness of the homo-sexual subculture were being challenged even as they were being made.For example,Farrell (1972)analyzed a questionnaire completed by 184respondents in “a large midwestern city”and provided a list of 233vocabulary items that he asserts “reflect...the preoccupations of the homosexual”(p.98).This idea of “the homosexual”was harshly attacked by Conrad &More (1976),who argued that if Kinsey’s reckoning that 10%of the American population is gay was correct,there must be enormous variation between homosexuals,and there can be no such thing as “the homosexual”or a single homosexual subculture.To refute Farrell’s conclusions,they administered a questionnaire consisting of 15words from Far-rell’s list to two groups of students—one gay (recruited through the campus’Gay Student Union),and the other self-defined as straight.The students were asked to define all the words they could.Conrad &More concluded that not only did all the homosexual students not know the entire vocabulary (knowledge seemed to increase with age),there was also no statistically significant difference between the gay and straight students’understanding of the terms.In other words,there is no basis,in the opinion of Conrad &More (1976),to assume that homosexuals constitute a “language defined sub-culture”(p.25).This point was later stated in even starker terms by Penelope &Wolfe (1979),who begin a paper on gay and lesbian language with the assertion that “[a]ny discussion involving the use of such phrases as ‘gay community,’‘gay slang,’or ‘gayspeak’is bound to be misleading,because two of its implications are false:first,that there is a homogenous commu-nity composed of Lesbians and gay males,that shares a common culture or system of values goals,perceptions,and experience;and second,that this gay community shares a common language”(p.1).Penelope &Wolfe base this outright rejection of the notions of gay commu-nity or gay language partly on an earlier study that examined gay slang (Stanley A n n u . R e v . A n t h r o p o l . 2000.29:243-285. D o w n l o a d e d f r o m w w w .a n n u a l r e v i e w s .o r g A c c e s s p r o v i d e d b y T s i n g h u a U n i v e r s i t y o n 05/10/15. F o r p e r s o n a l u s e o n l y .GAY AND LESBIAN LANGUAGE 2511970).5In that study,Penelope distributed a questionnaire through homosexual networks,in which respondents were asked to define 26terms and suggest two of their own.On the basis of 67completed questionnaires,Penelope argued that homosexual slang was not known by all homosexuals—there was,in other words,no homogenous homosexual subculture that shared a common language.Knowl-edge of homosexual slang varied according to gender and according to whether the respondent lived in an urban center or a rural town.She proposed that homosexual slang should be thought of as consisting of a core vocabulary,known by both men and women over a large geographical distance (Penelope’s discussion concerned only the United States),and a fringe vocabulary,known mostly by gay men in large urban centers.Penelope argued that the core vocabulary,consisting of items such as “butch,”“dyke,”“one-night stand,”and “Mary!,”is known to many het-erosexuals,thereby making it “not so effective as a sign of group solidarity as the slang of other subcultures”(Stanley 1970:50).It is the fringe vocabulary which is “the most interesting from a linguistic point of view”(p.53),partly because it is generally unknown to heterosexuals and hence qualifies as a true marker of group membership,and also because many terms in the fringe vocabulary arise from par-ticular syntactic patterns [Penelope lists six:compounds (size queen,meat rack),rhyme compounds (kiki,fag hag),exclamations (For days!),puns (Give him the clap),blends (bluff—a Texas lesbian blend of “butch”and “fluff”to signify “an individual who plays either the aggressive or the passive role”),and truncations (bi,homo,hetero)].While discussions like these about the relationship between gay slang and “the homosexual subculture”were being conducted in scholarly journals,the mag-nificent,still unsurpassed Mother of all gay glossaries,The Queen’s Vernacular appeared,first published in 1972by a small press in San Francisco (Rodgers n.d.).Making all previous attempts to document gay slang look like shopping lists scribbled on the back of a paper bag,Rodgers’s magnum opus contains over 12,000entries.And not only is it lavishly illustrated with enough venomous quips and arch mots to last any amply betongued queen at least a weekend [“My dear,your hair looks as if you’ve dyed”(p.207);“He was big enough to make a bead on my rosary of life”(p.173);“Stop pittypooing around and tell me what the bitch said”(p.149)];with entries ranging from anekay (Hawaiian-English gay slang for “heterosexual man”)to Zelda (Cape Town queenspeak for “pure-blooded Zulu”),The Queen’s Vernacular also carefully documents the extraordinary range and variation of homosexual slang that existed throughout the English-speaking world.Although Dynes (1985:156)is correct in noting 5During the course of her long career,the lesbian feminist linguist and writer Julia Penelope has published articles under the surnames Stanley,Penelope Stanley,and Penelope.In the references for this review,those articles are listed alphabetically under the names that appeared on the original publications.In the text,I consistently refer to the author as Penelope,since that is the name under which she has been publishing for many years.A n n u . R e v . A n t h r o p o l . 2000.29:243-285. D o w n l o a d e d f r o m w w w .a n n u a l r e v i e w s .o r g A c c e s s p r o v i d e d b y T s i n g h u a U n i v e r s i t y o n 05/10/15. F o r p e r s o n a l u s e o n l y .。

英语专业学士论文写作要求

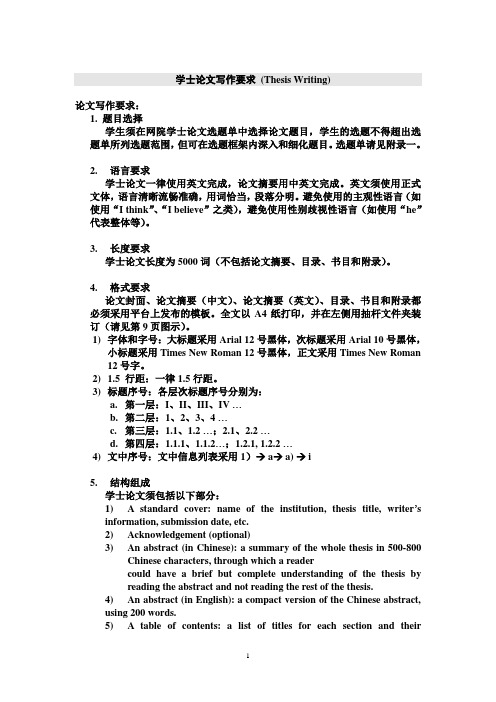

学士论文写作要求(Thesis Writing)论文写作要求:1. 题目选择学生须在网院学士论文选题单中选择论文题目,学生的选题不得超出选题单所列选题范围,但可在选题框架内深入和细化题目。

选题单请见附录一。

2.语言要求学士论文一律使用英文完成,论文摘要用中英文完成。

英文须使用正式文体,语言清晰流畅准确,用词恰当,段落分明。

避免使用的主观性语言(如使用“I think”、“I believe”之类),避免使用性别歧视性语言(如使用“he”代表整体等)。

3.长度要求学士论文长度为5000词(不包括论文摘要、目录、书目和附录)。

4.格式要求论文封面、论文摘要(中文)、论文摘要(英文)、目录、书目和附录都必须采用平台上发布的模板。

全文以A4纸打印,并在左侧用抽杆文件夹装订(请见第9页图示)。

1)字体和字号:大标题采用Arial 12号黑体,次标题采用Arial 10号黑体,小标题采用Times New Roman 12号黑体,正文采用Times New Roman12号字。

2) 1.5 行距:一律1.5行距。

3)标题序号:各层次标题序号分别为:a.第一层:I、II、III、IV …b.第二层:1、2、3、4 …c.第三层:1.1、1.2 …;2.1、2.2 …d.第四层:1.1.1、1.1.2…;1.2.1, 1.2.2 …4)文中序号:文中信息列表采用1)→ a→ a) → i5.结构组成学士论文须包括以下部分:1) A standard cover: name of the institution, thesis title, writer’sinformation, submission date, etc.2)Acknowledgement (optional)3)An abstract (in Chinese): a summary of the whole thesis in 500-800Chinese characters, through which a readercould have a brief but complete understanding of the thesis byreading the abstract and not reading the rest of the thesis.4)An abstract (in English): a compact version of the Chinese abstract,using 200 words.5) A table of contents: a list of titles for each section and theircorresponding page numbers.6) A body (See 6 for detailed information below)7) A bibliography: a list of books and articles that have been referredto in the body. (Y ou need to refer to at least 5 sources.)8)Appendices (Optional)6.内容要求论文的内容要求强调论点、论据和结论的清晰性、逻辑性和科学性。

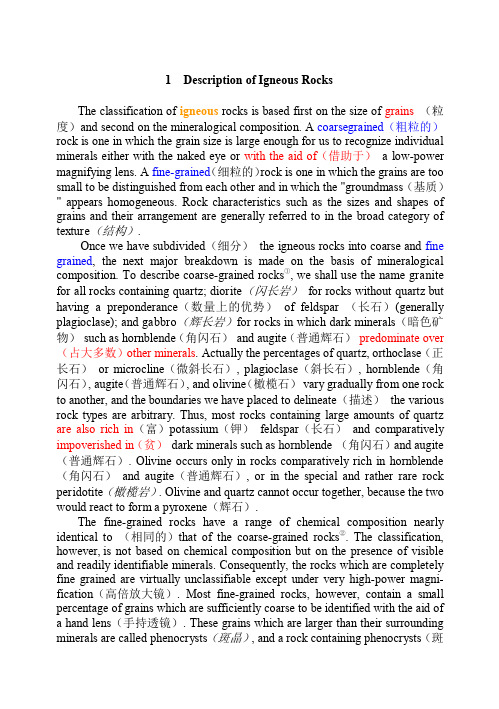

中国地质大学(北京)考博专业英复习材料

晶) is said to have a porphyritic texture(斑状结构). The classification of fine-grained rocks, then, is based on the proportion of minerals which form phenocrysts and these phenocrysts (斑晶)reflect the general composition of the remainder(残留) of the rock. The fine-grained portion of a porphyritic(斑岩) rock is generally referred to as the groundmass(基质) of the phenocrysts. The terms "porphyritic" and "phenocrysts" are not restricted to fine-grained rocks but may also apply to coarse-grained rocks which contain a few crystals distinctly larger than the remainder. The term obsidian(黑曜岩) refers to a glassy rock of rhyolitic(流纹岩) composition. In general, fine-grained rocks consisting of small crystals cannot readily be distinguished from③ glassy rocks in which no crystalline material is present at all. The obsidians, however, are generally easily recognized by their black and highly glossy appearanceass of the same composition as obsidian. Apparently the difference between the modes of formation of obsidian and pumice is that in pumice the entrapped water vapors have been able to escape by a frothing(起泡) process which leaves a network of interconnected pore(气孔) spaces, thus giving the rock a highly porous (多孔的)and open appearance(外观较为松散). ④ Pegmatite(结晶花岗岩) is a rock which is texturally(构造上地) the exact opposite of obsidian. ⑤ Pegmatites are generally formed as dikes associated with major bodies of granite (花岗岩) . They are characterized by extremely large individual crystals (单个晶体) ; in some pegmatites crystals up to several tens of feet in length(宽达几十英尺)have been identified, but the average size is measured in inches (英寸) . Most mineralogical museums contain a large number of spectacular(壮观的) crystals from pegmatites. Peridotite(橄榄岩) is a rock consisting primarily of olivine, though some varieties contain pyroxene(辉石) in addition. It occurs only as coarse-grained intrusives(侵入), and no extrusive(喷出的) rocks of equivalent chemical composition have ever been found. Tuff (凝灰岩)is a rock which is igneous in one sense (在某种意义上) and sedimentary in another⑥. A tuff is a rock formed from pyroclastic (火成碎 屑的)material which has been blown out of a volcano and accumulated on the ground as individual fragments called ash. Two terms(igneous and sedimentary) are useful to refer solely to the composition of igneous rocks regardless of their textures. The term silicic (硅质 的)signifies an abundance of silica-rich(富硅) and light-colored minerals(浅 色矿物), such as quartz, potassium feldspar(钾长石), and sodic plagioclase (钠长石) . The term basic (基性) signifies (意味着) an abundance of dark colored minerals relatively low in silica and high in calcium, iron, and

bibliography

bibliographyBibliographyIntroduction:In the academic and research world, the importance of a bibliography cannot be overstated. A bibliography is a comprehensive list of the sources used in a research paper, thesis, or any other written work. It serves multiple purposes, including acknowledging the original authors and their contributions, avoiding plagiarism, providing additional sources for readers to explore, and establishing the credibility of the work.Purpose of a Bibliography:The primary purpose of a bibliography is to give credit to the authors of referenced works. By citing the sources used, researchers show respect for the original authors' ideas and expertise. Additionally, a bibliography allows readers to verify the information presented in the paper and delve deeper into the topic. It also serves as a roadmap for future researchers who want to explore the same or related subjects.Components of a Bibliography:A bibliography typically includes various components, depending on the citation style used. The most common elements found in a bibliography are:1. Author's Name: The surname and first name or initials of the author should be provided. In the case of multiple authors, all their names should be listed.2. Title of the Work: The title of the book, article, or document being referenced should be included. If it is an article or chapter within a larger work, it should be enclosed in quotation marks.3. Publication Information: This includes the name of the book or journal, the publisher, and the publication date. For journals, the volume and issue numbers, as well as the page range, should also be mentioned.4. Web Sources: When citing online sources, the URL, access date, and any associated digital object identifier (DOI) shouldbe included. In some cases, if the webpage does not provide the author's name or publication date, it may be omitted.5. Additional Information: Depending on the citation style, additional information such as the edition, translator's name, or specific page numbers may be required.Citation Styles:There are various citation styles used in different academic disciplines. The most widely used citation styles include:1. APA (American Psychological Association): Commonly used in social sciences, education, and psychology-related fields.2. MLA (Modern Language Association): Primarily used in humanities and liberal arts subjects.3. Chicago/Turabian: Used for history, social sciences, and natural sciences.4. Harvard: Widely used in the sciences and social sciences.5. IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers): Mainly used in engineering, computer science, and information technology.Each citation style has specific guidelines for formatting the bibliography and in-text citations, so it is crucial to adhere to the specific style required by the institution or publisher.Benefits of a Bibliography:Apart from acknowledging the original sources and preventing plagiarism, a well-constructed bibliography offers several benefits to both the writer and the reader. These include:1. Enhancing Credibility: By providing a comprehensive list of references, the author demonstrates that their work is built upon a sound foundation and relies on accurate and reliable information.2. Extending Knowledge: Readers can use the bibliography to explore additional sources related to the topic. This not onlyimproves their understanding but also allows them to explore different perspectives and build their own knowledge base.3. Simplifying the Research Process: Researchers can save time and effort by referring to the bibliography of a well-written paper. Often, the bibliography itself directs readers to key works, eliminating the need for them to search for relevant sources from scratch.Conclusion:In conclusion, a bibliography is an indispensable component of any academic or research paper. It serves as a testament to the author's academic integrity, provides a roadmap for further exploration, and allows readers to verify and extend their knowledge. By understanding the purpose and components of a bibliography and adhering to the appropriate citation style, researchers can ensure that their work remains credible and contributes to the existing body of knowledge.。

NSABP乳腺癌系列临床试验

编辑课件

14

B-10试验

背景:70年代免疫调节剂成为热点,治疗肿瘤的效果? 入组1977-1990 随访8年 病例 256 乳癌根治术、改良根治,腋LN+:

编辑课件

23

B-24试验

B-17证实放疗对切缘阴性有效,对切缘阳性效果? 入组1991- 随访5年 病例 1804 弥漫性导管原位癌DCIS:病灶切除,切缘阳性

第一组 放疗 第二组 放疗+TAM5年 结果 TAM组同侧2.1%,对侧1.8%,远处0.2% 结论 对切缘阳性的广泛DCIS,病灶切除+放疗+ TAM, 如此低的复发率说明仍是一种可行的治疗方

化疗组可减低保乳术后同侧乳房复发率

编辑课件

18

B-19试验

入组1988-1996 随访5年 病例 1095 改良根治、保乳手术,ER-、腋LN-:

第一组 MTX→5-FU 第二组 CMF 结果 CMF组 DFS,DDFS,明显提高,减低保乳术 后同侧乳房复发率及远处转移,但副作用较 大,对50岁以上患者无明显优势

第一组 TAM +氮芥+5-FU 第二组 TAM +氮芥+5-FU+阿霉素 结果 2组间 DFS,OS无明显差异

结论 TAM与化疗联合应用,可能会影响化疗效果 B-09也有这种现象

编辑课件

17

B-13试验

入组1981-1996 随访8年 病例 760 改良根治、保乳手术,ER-、腋LN-:

第一组 MTX→5-FU+四氢叶酸 第二组 不化疗 结果 化疗组 DFS,DDFS,OS明显提高。

高三英语学术文章单选题50题

高三英语学术文章单选题50题1. In the scientific research paper, the term "hypothesis" is closest in meaning to _.A. theoryB. experimentC. conclusionD. assumption答案:D。

解析:“hypothesis”的意思是假设,假定。

“assumption”也表示假定,假设,在学术语境中,当提出一个假设来进行研究时,这两个词意思相近。

“theory”指理论,是经过大量研究和论证后的成果;“experiment”是实验,是验证假设或理论的手段;“conclusion”是结论,是研究之后得出的结果,所以选D。

2. The historical article mentioned "feudal system", which refers to _.A. democratic systemB. hierarchical social systemC. capitalist systemD. modern political system答案:B。

解析:“feudal system”是封建制度,它是一种等级森严的社会制度。

“democratic system”是民主制度;“capitalist system”是资本主义制度;“modern political system”是现代政治制度,与封建制度完全不同概念,所以选B。

3. In a literary review, "metaphor" is a figure of speech that _.A. gives human qualities to non - human thingsB. compares two different things without using "like" or "as"C. uses exaggeration to emphasize a pointD. repeats the same sound at the beginning of words答案:B。

IEEE期刊写作入门

How to Use the IEEEtran B IB T E X StyleMichael Shell,Member,IEEEAbstract—This article describes how to use the IEEEtran.bst B IB T E X stylefile to produce bibliographies that conform to the standards of the publications of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers(IEEE).Index Terms—bibliography,B IB T E X,IEEE,L A T E X,paper,style, template,typesetting.I.I NTRODUCTIONT HE IEEEtran.bst B IB T E X stylefile described in this document can be used with B IB T E X to produce L A T E X bibliographies of high quality that are suitable for use in IEEE publications.Other potential applications include thesis and academic work,especially when such work is in the area of electrical and/or computer engineering.This document applies to version 1.10and later of the IEEEtran B IB T E X style.Prior versions do not have all of the features described here.IEEEtran.bst will display the version number on the user’s console during execution.The most recent version of this package can be obtained on CTAN[1] and may also be mirrored at various places within IEEE’s website[2].It is assumed that the reader has a basic understanding of the operation and use of B IB T E X.Documentation for the use of B IB T E X includes the user’s guide[3]as well as supplementary information which addresses frequently asked questions[4].The large collection of sample bibliographies and string definitions at the T E X User Group Bibliography Archive may also be of help[5].General support for B IB T E X related questions can be obtained in the internet newsgroup comp.text.tex.Note that the references section of this document is used for two purposes:(1)to provide information where additional information can be found;and(2)to provide examples of references created using the IEEEtran B IB T E X style.Thefirst few citations above fall into thefirst category,while virtually all of the citations that follow will serve as examples and are not meant to be actually referred to.Hopefully,it will be clear from context which way a particular reference is used.II.I NSTALLATIONThe IEEEtran B IB T E X package consists of the following files:IEEEtran_bst_HOWTO.pdf:This documentation.Manuscript created on June20,2002;revised September27,2002.The opinions expressed here are entirely that of the author.No warranty is expressed or er assumes all risk.M.Shell is with the Georgia Institute of Technology.Email:mshell@ See[1]for current contact information.IEEEtran.bst:The standard IEEEtran B IB T E X stylefile (unsorted,i.e.,references will appear in the order in which they are cited).IEEEtranS.bst:The IEEEtran B IB T E X stylefile,but with additional sorting code(similar to that of plain.bst)which sorts the entries based on the names of the authors,editors, organizations,etc.May be of interest for non-IEEE related work.Do not use for work that is to be submitted to the IEEE. IEEEexample.bib:A B IB T E X database that contains the references shown in the references section of this document. Users can copy the entries therein to serve as starting tem-plates.The entries also have comments which may be of additional help.IEEEfull.bib:Afile that contains a comprehensive set of B IB T E X string definitions for the full names of IEEE journals and magazines.Because IEEE’s bibliography style uses abbreviated journal names,thisfile’s intended use is for work that is not to be submitted to the IEEE.IEEEabrv.bib:Same as above,but contains the abbreviated form of the journal and magazine names.Recommended for work that is to be submitted to the IEEE.IEEEbcpat.bib:Older versions of IEEE B IB T E X stylefiles usually provide several string definitions(“acmcs,”“acta,”etc.) for a few of the popular computer related journals.However,it is inappropriate to provide journal name definitions within.bst files as this prevents entries that use them from working with other.bstfiles(that may not contain the needed definitions). Furthermore,these older definitions are not abbreviated as needed for IEEE related work.IEEEtran.bst does not provide the older definitions as it is designed to work with the newer “external”IEEEabrv.bib definitions instead.To provide for backward compatibility,IEEEbcpat.bib contains these obsolete definitions and can be loaded prior to any existing database files that still depend on them.Do not use the IEEEbcpat.bib definitions for new entries,or work that is to be submitted to the IEEE.B IB T E X.bstfiles can be accessed system-wide when they are placed in the<texmf>/bibtex/bstdirectory,where<texmf>is the root directory of the user’s T E X installation.Similarly,system-wide.bibfiles(IEEEful-l.bib and IEEEabrv.bib)can be placed in<texmf>/bibtex/bibOn some L A T E X systems,the directory look-up tables will need to be refreshed after making additions or deletions to the systemfiles.For teT E X and fpT E X systems this is accomplished via executingc 2002Michael Shelltexhashas root.MikT E X users can runinitexmf-uto accomplish the same thing.Users not willing or able to install thefiles system-wide can make the copies local,but will then have to provide the path(full or relative)as well as thefilename when referring to them in L A T E X.III.U SAGEIEEEtran.bst is invoked using the normal L A T E X bibliography commands:\bibliographystyle{IEEEtran}\bibliography{IEEEabrv,mybibfile}String definitionfiles must be loaded before any databasefiles containing entries that utilize them—so thefile names within the\bibliography command must be listed in a proper order.In standard B IB T E X fashion,new documents will require a L A T E X run followed by a B IB T E X run and then two more L A T E X runs in order to resolve all of the references.An additional series of runs will be required as citations are added to the document.A.Resource RequirementsIEEE’s bibliography style has several unique attributes that increase the complexity of B IB T E X styles that attempt to mimic it.Because the primary design goal of IEEEtran.bst is to reproduce the IEEE bibliography style as accurately and as fully as possible,IEEEtran.bst will consume significantly more computation resources(especially memory)during execution than many other B IB T E X stylefiles.Most modern B IB T E X installations will be able to meet these demands without prob-lem.However,some earlier B IB T E X platforms,especially those running on the MS Windows operating system,may be unable to provide the required memory space.Such platforms often provide as an alternative the higher-capacity1“8-bit B IB T E X”in the form of a“bibtex8”executable which IEEEtran.bst is fully compatible ers who encounter B IB T E X resource limitations should upgrade their B IB T E X installation.More details on this topic can be found in[4].B.Nonstandard ExtensionsAnother,related,issue is that IEEEtran.bst provides exten-sions beyond the standard B IB T E X entry types andfields.These additional features are necessary for IEEE style work and were designed to closely follow the existing as well as“probable future”releases of the standard B IB T E X styles.Nevertheless, users should be aware that many current B IB T E X styles may not be compatible with B IB T E X databases that employ ad-vanced features of IEEEtran.bst.B IB T E X will generate an error 1However,command options may be needed to obtain the higher capacity, e.g.,bibtex8-H e bibtex8-help to list the possible options.if it encounters a(cited)entry type that the stylefile does not support,but unsupportedfields within an entry will simply be ignored.For this reason,users are encouraged to keep all nonstandard entry types in a B IB T E X database(.bib)file of their own.The nonstandard IEEEtran.bst entry types are:(1)“electronic”which is used for internet references;(2)“patent”which is used for patents;(3)“periodical”which is used for journals and magazines;and(4)“standard”which is used for published standards.The most important extensions to the supportedfields will now be briefly mentioned.1)The URL Field:Every entry type supports an optional URL entryfield for documents that are available on the internet.URLs will appear at the end of the bibliography entry and proceeded by the words“[Online].Available:”as is shown in[1].IEEE does not place any punctuation at the end of a URL as this could be mistaken as being part of the URL. URLs are notoriously difficult to break properly.IEEEtran.bst places all URL text within a\url{}command so as to provide“plug-and-play”use with packages that provide such a command.It strongly suggested that,when using entries with URLs,the popular L A T E X package url.sty[6]is also loaded to provide some intelligence in URL line breaking.Alternatively, the hyperref.sty package[7]also provides a\url command. However,unless the user needs hyperlinks,url.sty might be a better approach because it is“lightweight”and less likely to exhibit compatibility issues.Users should be aware that version1.5and prior of url.sty interacts with B IB T E X(version0.99c and prior)in way that can result in the anomalous appearance of“%”symbols within the URLs.To avoid this problem,it is recommended that users modify(or possibly upgrade)their url.sty package if they are using version1.5or earlier.The following code,2when placed just after where the url.sty package(version1.5)is loaded,or at the end of the definitions within the url.styfile(just before the\endinput line),will correct the problem by configuring url.sty to ignore“%”symbols that are immediately followed by line feeds within the\url command:\begingroup\makeatletter\g@addto@macro{\UrlSpecials}{%\endlinechar=13\catcode\endlinechar=12\do\%{\Url@percent}\do\ˆˆM{\break}}\catcode13=12%\gdef\Url@percent{\@ifnextcharˆˆM{\@gobble}{\mathbi n{\mathchar‘\%}}}%\endgroup%If the T E X system is used by others,the original url.sty should be retained and the modified version given a different name (e.g.,”url15b.sty”).Note that any renamed stylefile needs its“\ProvidesPackage”line updated to reflect the current filename or else L A T E X will issue a(harmless)warning.The\url command from recent versions of hyperref.sty does not exhibit this problem.For more details,see[4]. Even with intelligent URL breaking,formatting an entry with a URL can still pose challenges as URLs may contain long segments within which breaks are not possible(or at least 2This T E X code can also be obtained from[4].strongly discouraged).In its publications,IEEE deals with this problem by allowing the interword space to stretch more than usual.To accomplish this,IEEEtran.bst automatically engages a“super-stretch”feature for every entry that contains a URL. The interword spacing within entries that contain URLs is allowed to stretch up to four times normal without causing underfull hbox warnings.Reference[1]illustrates this feature. Section VII discusses how users can control the amount of allowed stretch in entries with URLs.Alternatively,the default value of this stretch factor can be adjusted via a L A T E X command,which must be placed before the bibliography begins:\providecommand\BIBentryALTinterwordstretchfac tor{2.5}However,these adjustment mechanisms are of limited use because reducing the stretch factor usually just results in underfull hbox warnings.Another way to handle problem URLs is to configure url.sty to allow more possible break points.2)The Language Field:IEEEtran.bst supports an optional languagefield which allows alternate hyphenation patterns to be used for the title and/or booktitlefields when thesefields are in language other than the default.For examples,see sections V-N and VI-B as they each contain a reference that uses the languagefield.This feature is especially important for languages that alter the spelling of words based on how they are hyphenated.Unlike some other B IB T E X stylefiles,the use of the Babel package is not required to use this feature.In fact,Babel.sty should not be loaded with IEEEtran.cls as the former can interfere with the latter.However,the names given in the languagefield must follow Babel’s convention for the names of the hyphenation patterns.See the Babel documentation for details[8].It is a T E X limitation that,to be available for use,a hyphen-ation pattern must be loaded within a“formatfile”(memory image)and,therefore,cannot be loaded when running a.tex file.A list of available patterns is displayed on the console each time L A T E X is started.If a requested hyphenation pattern is not available,the default will be used and a warning will be ers wishing to add hyphenation patterns will need to activate the desired ones in their<texmf>/tex/generic/config/language.datfile and rebuild their L A T E X formatfile3.Adding hyphenation patterns does reduce the amount of memory available to T E X, so it cannot be done with impunity.3)Expanded Use of the Howpublished Field:The standardB IB T E X styles support the howpublishedfield for the booklet and misc entry types.IEEEtran.bst extends this to also include electronic,manual,standard and techreport.The rational for doing this is because,with these entry types,there is often a need to explain in what form the given work was pro-duced.The additional information provided by howpublished 3On teT E X(UNIX)and fpT E X systems this can be accomplished simply by running“fmtutil--all”as root.For MiKT E X users,the command “initexmf--dump”will do the trick.is placed,as given,in normal font,just after the title(or booktitle,if used)of the entry.IEEE exploits this feature most often for electronic ref-erences,but it has application with any entry whose exact form would be unclear without additional information(unlike optional notes which tend to be more“by the way”in nature). See section V for more details.e With Cross-referenced EntriesIEEE bibliographies do not normally contain references that refer to other references.Therefore,IEEEtran.bst does not format entries that use cross references(via the crossreffield) any differently from entries that don’t.Nevertheless,it does allow the entries using the crossreffield to silently inherent any missingfields from their respective cross-referenced entries in the standard B IB T E X manner.However,users who take advantage of this“parent/child”feature are cautioned that B IB T E X will automatically,and without warning,add a cross-referenced entry to the end of the bibliography if the number of references using the cross-reference is equal to or greater than “min-crossrefs.”Because such additional entries are unwanted in IEEE style,users who employ cross-referenced entries need to ensure that the cross-referenced entries are not added to the bibliography.The default value of min-crossrefs on most B IB T E X systems is two.Unfortunately,this value is set when B IB T E X is compiled and cannot be altered within.bst files.However,B IB T E X does offer a way to control it on the command line.Therefore,when using cross-referenced entries,users must remember to set min-crossrefs to a large value(greater than the number of bibliography entries)when invoking B IB T E X:bibtex-min-crossrefs=900myfileBecause cross-referenced entries must always appear after any entries that refer to them,it is recommended that the cross-referenced entries be kept in separate(.bib)file(s)so that they can be loaded after the other(.bib)databasefiles:\bibliography{IEEEabrv,mybibfile,myxrefbibs} IV.E XAMPLES OF THE T HREE M OST C OMMONLY U SEDE NTRY T YPESJournal articles,conference papers and books account for the vast majority of references in most IEEE bibliographies. It may be helpful to the user to briefly illustrate a simple example of each of these common entry types before divulging into ones with more complex or obscure details.A typical journal article entry looks like@article{IEEEexample:article_typical,author="S.Zhang and C.Zhu and J.K.O.Sinand P.K.T.Mok",title="A Novel Ultrathin Elevated ChannelLow-temperature Poly-{Si}{TFT}", journal=IEEE_J_EDL,volume="20",month=nov,year="1999",pages="569-571"};which is shown as reference[9].Using an entry key prefix that is used only by the given databasefile(“IEEEexample”in the above entry)ensures that the entry key will remain unique even if multiple databasefiles are used simultaneously.Although initials are used for thefirst names here,users are encouraged to use full names whenever they are known as IEEEtran.bst will automatically abbreviate names as needed(but B IB T E X styles that use full names will require them to be present). Likewise,it is a good idea to provide all the authors’names rather than using“and others”to get“et al.”[10].Section VII describes how IEEEtran.bst can be configured to force the use of“et al.”if the number of names exceeds a set limit. Within the title,braces are used to preserve the capitaliza-tion of acronyms.The journal name is entered as a string that is defined in the IEEEabrv.bibfile.Not only does this approach reduce the probability of spelling mistakes,but it allows the user to instantly switch to full journal names by using the IEEEfull.bib definitions instead(not for use with work to be submitted to the IEEE).In like fashion,the month is entered as a standard B IB T E X three letter code4so that the month format can automatically be controlled by the string(macro)month name definitions provided within every.bstfile.It is generally a good idea to also provide the journal number,but many journal article references in IEEE publi-cations do not show the number.Section VII discusses how the user can configure IEEEtran.bst to ignore journal numbers for articles.A typical paper in a conference proceedings entry looks like @inproceedings{IEEEexample:conf_typical,author="R.K.Gupta and S. D.Senturia",title="Pull-in Time Dynamics as a Measureof Absolute Pressure",booktitle="Proc.{IEEE}International Workshopon Microelectromechanical Systems({MEMS}’97)",address="Nagoya,Japan",month=jan,year="1997",pages="290-294"};which is shown as reference[11].IEEE typically prepends“Proc.”to the conference name (when forming the booktitlefield):booktitle="Proc.{ECOC}’99",IEEEtran.bst does not do this automatically as it may not be appropriate for every conference.The conference entry type is also available as an alias for inproceedings.There is no functional difference between the two.Finally,a typical book entry looks like@book{IEEEexample:book_typical,author="B. D.Cullity",title="Introduction to Magnetic Materials", publisher="Addison-Wesley",address="Reading,MA",year="1972"};4For reference,these are:jan,feb,mar,apr,may,jun,jul,aug,sep,oct, nov and dec.which is shown as reference[12].One of the unusual attributes of IEEE bibliography references is that,when formatting entries,they precede the publisher address with a period and a larger than normal space.V.S UPPORTED E NTRY T YPESThefields that are recognized by each entry type are shown at the beginning of each of the subsections below.A bold font indicates a requiredfield,while a slanted font is used to indicatefields that are extensions that may not be supported by the standard B IB T E X styles for the given entry type.The reader is reminded that IEEEexample.bibfile contains the actual B IB T E X entries that were used to make the references demonstrated here.A.ArticleSupportedfields:author,title,language, journal,volume,number,pages,month,year,note, url.Another typical journal article is shown in[13].Because the referenced journal was not published by the IEEE,the IEEEabrv.bibfile will not contain the needed string definition. So,the user will either have to make his/her own supple-mentary string definitionfile,or enter the abbreviated journal name directly into the journalfield.See published IEEE bibliographies for examples of how to properly abbreviate the journal name at hand.Note also how IEEE uses small spaces to divide page(and other)numbers withfive digits or more into groups of three.As mentioned previously,the display of the numberfield for articles can be controlled(see section VII).Sometimes it is desirable to put extra information into the monthfield such as the day,or additional months[14].This is accomplished by using the B IB T E X concatenation operator “#”:month=sep#"/"#oct,1)Articles Pending Publication:Articles that have not yet been published can be handled as a misc type with a note[15]: @misc{IEEEexample:TBPmisc,author="M.Coates and A.Hero and R.Nowakand B.Yu",title="Internet Tomography",howpublished=IEEE_M_SP,month=may,year="2002",note="to be published"};(date information is optional)or they can be handled as an article type with the pending status in the yearfield[16]:@article{IEEEexample:TBParticle,author="N.Kahale and R.Urbanke",title="On the Minimum Distance of Paralleland Serially Concatenated Codes", journal=IEEE_J_IT,year="submitted for publication"};B.BookSupportedfields:author and/or editor,title, language,edition,series,address,publisher, month,year,volume,number,note,url.Books may have authors[12],editors[17]or both[18].Note that the standard B IB T E X styles do not support book entries with both author and editorfields,but IEEEtran.bst does. The standard B IB T E X way of entering edition numbers is in capitalized ordinal word form:edition="Second",IEEEtran.bst can automatically convert up to the tenth edition to the“Arabic ordinal”form(e.g.,“2nd”)that IEEE uses.For editions over the tenth in references that are to be used in IEEE style bibliographies,it is best to enter editionfields in the“Arabic ordinal”form(e.g.,“101st”).A book may also be part of a series and have a volume or number[19].C.InbookSupportedfields:author and/or editor,title, language,edition,series,address,publisher, month,year,volume,number,chapter,type,pages, note,url.Inbook is used to reference a part of a book,such as a chapter[20]or selected page(s)[21].The typefield can be used to override the word chapter(for which IEEE uses the abbreviation“ch.”)when the book uses parts,sections,etc., instead of chapterstype="sec.",D.IncollectionSupportedfields:author,title,booktitle, language,edition,series,editor,address, publisher,month,year,volume,number,chapter, type,pages,note,url.Incollection is used to reference part of a book having its own title[22].Like book,incollection supports the series[23], chapter and pagesfields[24].Also,the typefield can be used to override the word chapter.IEEE sometimes uses incollection somewhat like inproceed-ings when the book in question is a composition of articles from various conferences[25].For such use,the differences between incollection and inproceedings are minor—one distinctive sign is that,with incollection,the volume number appears after the date,while with inproceedings it appears before.To better support such use,IEEEtran.bst,unlike the standard B IB T E X styles,does not require a publisherfield for incollection entries.E.BookletSupportedfields:author,title,language, howpublished,organization,address,month,year, note,url.Booklet is used for printed and bound works that are not formally published.IEEEtran.bst formats titles of booklets like articles—not like manuals and books.A primary difference between booklet and unpublished is that the former is/was distributed by some means.Booklet is rarely used in IEEE bibliographies.F.ManualSupportedfields:author,title,language,edition, howpublished,organization,address,month,year, note,url.Technical documentation is handled by the manual entry type[26].Note that the cited example places the databook part number with the title.Perhaps a more correct approach would be to put this information into the howpublishedfield instead[27].However,other B IB T E X styles will probably not support the howpublishedfield for manuals.G.Inproceedings/ConferenceSupportedfields:author,title,intype, booktitle,language,series,editor,volume, number,organization,address,publisher,month, year,paper,type,pages,note,url.References of papers in conference proceedings are handled by the inproceedings or conference entry types.These two types are functionally identical and can be used interchange-ably.If desired,the days of the conference can be added to the month via the B IB T E X concatenation operator“#”[28]: month=dec#"5--9,",Although not common with conference proceedings,the volume and numberfields are also supported[29].Note that, unlike the other entry types,IEEE places such information prior to the date.From IEEE’s viewpoint,the location and date of the conference may form the dividing point between information related to identifying which proceedings and information that pertains to the location of the information referenced therein(pages,etc.).IEEEtran.bst supports a paperfield(a nonstandard exten-sion)for paper numbers[30]:paper="11.3.4",The typefield can be used to override the default paper type (“paper”)[31]:type="postdeadline paper",Section VII describes how these extensions can be disabled if desired for journals with bibliographies that tend not to display such information(while allowing the user to retain such information in the database entries for those journals that do).There are events that happen during conferences that may not be in the written proceedings record(speeches,etc.). Sometimes it is necessary to reference such things.For these occasions,IEEEtran.bst supports the intypefield(a nonstan-dard extension)which can override the word“in”in the reference[32]:intype="presented at the",Note that when using intype,the booktitlefield is no longer italicized because the book that contains the written conference record is no longer what is being referred to.H.ProceedingsSupportedfields:editor,title,language,series, volume,number,organization,address,publisher, month,year,note,url.It is rare to need to reference an entire conference proceed-ings,but,if necessary,the proceedings entry type can be used to do so.I.MastersthesisSupportedfields:author,title,language,type, school,address,month,year,note,url.Master’s(or minor)theses can be handled with the master-sthesis entry type[33].The optional typefield can be used to override the words“Master’s thesis”if a different designation is desired[34]:type="M.Eng.thesis",J.PhdthesisSupportedfields:author,title,language,type, school,address,month,year,note,url.The phdthesis entry type is used for Ph.D.dissertations (major theses)[35].Like mastersthesis,the typefield can be used to override the default designation.K.TechreportSupportedfields:author,title,language, howpublished,institution,address,number,type, month,year,note,url.Techreport is used for technical reports[36].The optional typefield can be used to override the default designation “Tech.Rep.”[37],[38].L.UnpublishedSupportedfields:author,title,language,month, year,note,url.The unpublished entry type is used for documents that have not been formally published.IEEE typically just uses “unpublished”for the required notefield[39].M.Electronic(IEEEtran.bst extension)Supportedfields:author,month,year,title, language,howpublished,organization,address, note,url.IEEEtran.bst provides the electronic entry type for internet references[40],[41].IEEEtran.bst also provides the aliases “online,”“internet,”and“webpage”for compatibility with some existing B IB T E X database and stylefiles.However,“electronic”should be used for all new work.IEEE formats electronic references differently by not using italics or quotes and separatingfields with periods rather than commas.Also, the date is enclosed within parentheses and is placed closer to the title.This is probably done to emphasize that electronic references may not remain valid on the rapidly changing internet.Note also the liberal use of the howpublishedfield to describe the form or category of the entries.The organization and addressfields may also be used[42].N.Patent(IEEEtran.bst extension)Supportedfields:author,title,language,assignee, address,nationality,type,number,day,dayfiled, month,monthfiled,year or yearfiled,note,url. Patents are supported by IEEEtran.bst.The nationalityfield provides a means to handle patents from different countries [43],[44]nationality="United States",ornationality="Japanese",Note that,with the exception of the U.S.,the word for the nationality of a patent is not usually the same as the word for the country that issued the patent.The nationality for a U.S.patent can be entered either as“U.S.”or“United States.”IEEEtran.bst will automatically detect and convert the latter form to“U.S.”as is done by IEEE.The nationality should be capitalized.The assignee and address(of the assignee)fields are not used by IEEE or IEEEtran.bst.However,they are provided, and proper values should be assigned to them(if known)for all patent entries as other B IB T E X styles may use them.The typefield provides a way to override the“patent”description with other patent related descriptions such as “patent application”or“patent request”[45]:type="Patent Request",In order to provide full support for both patents and patent applications,two sets of datefields are provided.One set pertains to the date the patent was granted(day,month and year)the other pertains to the date the patent application wasfiled(dayfiled,monthfiled and yearfiled).There is a slight complication because IEEE displays only one date for references of patents or patent applications.IEEEtran.bst looks for the presence of the year and yearfiledfiles.If the year field is present,the set pertaining to the date granted is used. Otherwise,IEEEtran.bst uses the set pertaining to the date filed.O.Periodical(IEEEtran.bst extension)Supportedfields:editor,title,language,series, volume,number,organization,month,year,note, url.The periodical entry type is used for journals and magazines [46].P.Standard(IEEEtran.bst extension)Supportedfields:author,title,language, howpublished,organization or institution,type, number,revision,address,month,year,note,url.。

世界几大著名图书馆英文介绍

1815.After a period of decline

during the mid-19th century the Library of Congress began to grow rapidly in both size and importance after the American Civil War, culminating in the construction of a separate library building and the transference of all copyright deposit holdings to the Library

bookshelves, while the British Library reports about 625 kilometers (388 mi) of shelves. The Library of Congress holds about 147 million items with 33 million books against approximately 150 million items with 25 million books for the British Library

• The Library makes millions of digital objects, comprising tens of petabytes (10的15次方字节), available at its American Memory site. American Memory is a source for public domain image resources, as well as audio, video, and archived Web content. Nearly all of the lists of holdings, the catalogs of the library, can be consulted directly on its web site.

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。