Key Points from NCEP Guidelines - 39健康网

故障预测与健康管理(PHM)- 可靠性

/The_Re liability Calendar/Webinars ‐ liability_Calendar/Webinars_ _Chinese/Webinars_‐_Chinese.html

Prognostics

TM

Prognostics and Health Management Fundamentals

• • • • • • • •

3

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Emerson Appliance Controls Emerson Appliance Solutions Emerson Network Power Emerson Process Management Engent, Inc. Ericsson AB Essex Corporation Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc. Exponent, Inc. Fairchild Controls Corp. Filtronic Comtek GE Healthcare General Dynamics, AIS & Land Sys. General Motors Guideline Hamlin Electronics Europe Hamilton Sundstrand Harris Corp Henkel Technologies Honda Honeywell Howrey, LLP Intel Instituto Nokia de Technologia Juniper Networks Johnson and Johnson Johns Hopkins University Kimball Electronics L-3 Communication Systems LaBarge, Inc Lansmont Corporation Laird Technologies LG, Korea Liebert Power and Cooling Lockheed Martin Aerospace Lutron Electronics Maxion Technologies, Inc. Microsoft

2020年美国心脏学会CPR与ECC指南摘要翻译

成人心脏骤停自主循环恢复后治疗流程图

图 7. 成人心脏骤停自主循环恢复后治疗流程图。

对心脏骤停恢复自主循环后的成人患者进行多模式神 经预测时建议采取的方法

图 8. 对心脏骤停恢复自主循环后的成人患者进行多模式神经预测时建议采取的方法。

四、孕妇心脏骤停院内 ACLS 流程图

图 9. 孕妇心脏骤停院内 ACLS 流程图。

COR 和LOE 分布

图 2.《2020年美国心脏协会心肺复苏及心血管急救指南》中总共 491 条建议的 COR 和 LOE 百分比分布。*

* 结果为 491 条建议的百分比,涉及成人基础和高级生命支持、儿童基础和高级生命支持、新生儿生命支持、复苏教育科学和救治系统。 缩略语:COR,建议类别;EO,专家意见;LD,有限数据;LOE,证据等级;NR,非随机;R,随机。

• 此外,美国医院收治的成人患者中约有1.2%发生院内心脏骤停 (THKCA),与OHCA相比,IHCA预后明显更好,并持续改善。

• 2020年指南对有关成人基础生命支持(BLS)和高级心血管生命支持 (ACLS)的建议予以合并。主要新变化包括:

• ·强化流程图和视觉辅助工具,为BLS和ACLS复苏场景提供易于记忆 的指导。

一、概述

主题

成人基础和 高级生命支持

儿童基础和 高级生命支持

新生儿 生命支持

复苏教育科学

救治系统

推荐级别和证据级别

图 1. 在患者救治的临床策略、干预、治疗或诊断中使用推荐级别和证据级别(更新于 2019 年 5 月)*

推荐级别和证据级别

图 1. 在患者救治的临床策略、干预、治疗或诊断中使用推荐级别和证据级别(更新于 2019 年 5 月)*

2010(旧):如果成人猝倒或无反应患者 呼吸不正常,非专业施救者不应检查脉 搏,而应假定存在心脏骤停。医务人员 应在不超过 10 秒时间内检查脉搏,如 在该时间内并未明确触摸到脉搏,施救 者应开始胸外按压。

围术期患者营养支持规范指南规范.doc

成人围手术期营养支持指南中华医学会肠外肠内营养学分会自2006年中华医学会肠外肠内营养学分会制定《临床诊疗指南:肠内肠外营养学分册》至今已有10年,为了更好地规范我国的临床营养实践,我们按照当今国际上指南制定的标准流程,根据发表的文献,参考各国和国际性营养学会的相关指南,综合专家意见和临床经验进行回顾和分析,并广泛征求意见,多次组织讨论和修改,最终形成本指南。

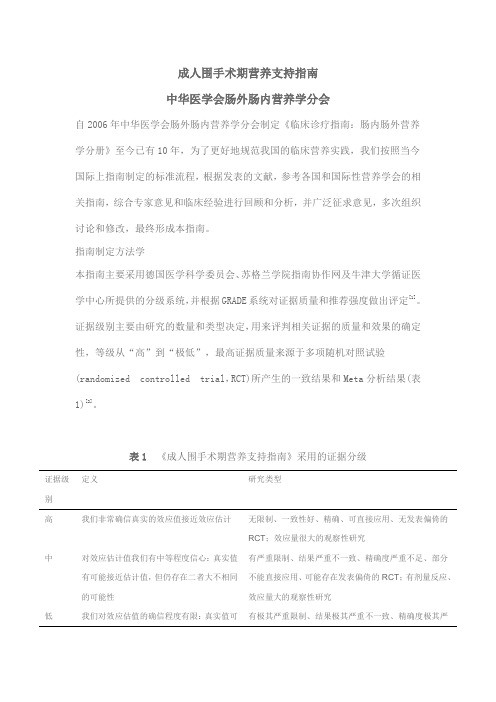

指南制定方法学本指南主要采用德国医学科学委员会、苏格兰学院指南协作网及牛津大学循证医学中心所提供的分级系统,并根据GRADE系统对证据质量和推荐强度做出评定[1]。

证据级别主要由研究的数量和类型决定,用来评判相关证据的质量和效果的确定性,等级从“高”到“极低”,最高证据质量来源于多项随机对照试验(randomized controlled trial,RCT)所产生的一致结果和Meta分析结果(表1)[2]。

表1《成人围手术期营养支持指南》采用的证据分级证据级别定义研究类型高我们非常确信真实的效应值接近效应估计无限制、一致性好、精确、可直接应用、无发表偏倚的RCT;效应量很大的观察性研究中对效应估计值我们有中等程度信心:真实值有可能接近估计值,但仍存在二者大不相同的可能性有严重限制、结果严重不一致、精确度严重不足、部分不能直接应用、可能存在发表偏倚的RCT;有剂量反应、效应量大的观察性研究低我们对效应估值的确信程度有限:真实值可有极其严重限制、结果极其严重不一致、精确度极其严能与估计值大不相同重不足、大部分不能直接应用、很有可能存在发表偏倚的RCT;观察性研究极低我们对效应估计值几乎没有信心:真实值很可能与估计值大不相同有非常严重限制、结果非常严重不一致的RCT;结果不一致的观察性研究;非系统的观察性研究(病例系列研究、病例报告)注:RCT为随机对照试验根据PICO系统构建合适的临床问题,通过相应的关键词进行系统文献检索,文献搜索资源中,一级文献数据库包括MEDLINE、PubMed、EmBase、中国生物医学文献数据库,二级文献数据库包括Cochrane Database of Systemic Reviews、the National Guideline Clearinghouse,再利用Google学术搜索进行搜索(含电子出版物),搜索时间截至2016年3月29日。

美国胸外科协会关于脓胸管理的共识指南(2020完整版)

美国胸外科协会关于脓胸管理的共识指南(2020完整版)方法AATS指导委员会选择了脓胸的管理作为一个适合用于制定临床指南的主题,共同主席(K.Robert Shen,MD和Benjamin Kozower,MD)被任命去创建一个脓胸管理指南工作组,该工作组将在2015年4月之前为AATS指导委员会制定脓胸管理指南。

共同主席集合组成了一个多学科专家小组,包括5名胸外科医生、1名介入放射科医生、1名传染病专家和1名介入性肺病专家。

委员会成员的任务是进行全面的文献检索,并根据对文献的审查提出建议。

成员们还对支持建议的证据的质量进行了分级,并评估了每一项建议的风险-效益。

工作成员小组根据医学机构(IOM)公布的标准对证据水平(LOE)进行分级(图1)。

在制定准则时,我们参考了IOM 2011年“我们可以相信的临床实践指南:制定可信赖的临床实践指南的标准”(/cpgStandard),并且遵循了IOM的建议。

利用三次排定的电话会议安排了指南所涵盖的专题,并审查了文献审查摘要和建议。

所有会议的议程事先分发,会议记录随后分发。

所有电话会议都由AATS工作人员记录下来,以改进笔记的转录。

随后举行了为期一天的面对面会议,正式就最后建议进行表决,以提交给AATS的议员,并审查终稿。

需要对对所有建议进行投票表决。

对最后文件的接受要求每项建议的认可均超过75%。

图1.用于指导现有已发表证据的分级模式,以及干预对患者结果的预期效果引言脓胸,来自希腊被称为“脓液在胸部”。

脓胸最常见的前兆是细菌性肺炎和随后的胸腔积液。

引起脓胸的其他原因包括:肺癌、食管破裂、胸部钝性或穿透性创伤、纵隔炎伴胸膜累及、呼吸道和食管感染先天性囊肿、膈肌以下来源的累及、颈椎和胸椎感染以及术后病因。

脓胸是一种古老的疾病,仍然是一个重要的临床问题。

尽管有了抗生素的广泛使用和肺炎球菌疫苗的提供,脓胸仍然是肺炎最常见的并发症,也是全世界发病和死亡的一个重要原因。

JNC7美国高血压指南 (JNC7中文版)

美国预防、检测、评估与治疗高血压全国联合委员会第七次报告(JNC 7)摘要“美国预防、检测、评估与治疗高血压全国联合委员会第七次报告(JNC 7)”是预防和治疗高血压的新指南。

主要内容包括:(1)50岁以上成人,收缩压(SBP)≥140 mm Hg是比舒张压(DBP)更重要的心血管疾病(CVD)危险因素;(2)血压从115/75 mm Hg 起,每增加20/10 mm Hg ,CVD的危险性增加一倍;55岁血压正常的人,未来发生高血压的危险为90%。

(3)收缩压120—129 mm Hg或舒张压 80—89 mm Hg,为高血压前期(prehypertensive),应改善生活方式以预防CVD;(4) 噻嗪类利尿剂用于大多数无合并证的高血压患者,可单独或与其它类型的降压药联合应用。

有高危险因素时,应首选其它类型的降压药(血管紧张素转换酶抑制剂(ACEI),血管紧张素受体拮抗剂(ARBs),β受体阻滞剂,钙拮抗剂(CCBs));(5)大多数高血压患者需要2种或2种以上的降压药来达到目标血压(<140/90 mm Hg, 糖尿病或慢性肾病患者<130/80 mm Hg);(6)如血压超过目标血压20/10 mm Hg以上,应考虑选用2种降压药作为初始用药,其中一种通常为噻嗪类利尿剂;(7)只有在患者积极配合的前提下,最细致的临床医生选用最有效的治疗,才能够控制好血压。

患者的治疗效果较好并信任医生时,会更好地配合治疗。

情感交流可使医生赢得信任,有助于提高疗效。

最后,指南委员会指出最重要的仍然是负责医生的判断力。

30多年来,美国国家高血压教育计划(NHBPEP)协作委员会一直在美国国立心肺血液研究所(NHLBI)的管理下,NHBPEP由39个主要专业、公立和志愿组织以及7个联邦机构组成。

主要的作用之一是发布指南并促进对高血压的知晓、预防、治疗和控制。

自1997年预防、检测、评估与治疗高血压全国联合委员会第六次报告(JNC VI)公布后1,已有许多大型临床试验结果发表。

Guidelines for the Older Adult With CKD

In the LiteratureGuidelines for the Older Adult With CKDCommentary on Leipzig RM,Whitlock EP,Wolff TA,et al;for the US Preventive Services Task Force Geriatric Workgroup.Reconsidering the approach to prevention recommendations for older adults.Ann Intern Med.2010;153(12):809-814.When treating older patients,clinicians have to make complex decisions to prioritize amongmany available preventive and therapeutic interven-tions.There is a large overlap between older age and chronic kidney disease (CKD):in the United States,25million individuals are 70years or older and almost half of them have CKD.1Vice versa,23million US residents have CKD and almost half are 70years or older.1,2Nephrology guidelines are a driving force for stan-dardization of care and professional self-improve-ment in the management of patients with CKD.3Clinical practice guidelines are tools to support deci-sion making by practitioners,patients,and policy makers.However,they repeatedly have been criti-cized as not being applicable to complex patients.4-6There is an inherent tension between making guide-lines simple and evidence-based versus sufficiently detailed and applicable to individuals with varying disease severity,comorbidity,and prognosis.Guide-lines may never perfectly address complex patients because this usually requires judgment along with extrapolation of evidence from less complex and often younger populations.Ultimately,guideline pan-els must choose between providing no recommenda-tion when evidence is of low quality versus issuing discretionary recommendations based on extrapola-tion of evidence and experts’best guesses.Some clinicians have voiced frustration with the former approach 7and a preference for the latter.8This sug-gests that some clinicians may be willing to tolerate greater uncertainty for guideline panels to address more complex issues.9Therefore,guideline panels have to develop new approaches to purposefully and transparently consider important complexity and its potential impact on expected benefits and harms of recommended actions.10Leipzig et al 11propose a refined approach,which published in 2010in theAnnals of Internal Medicine ,to better address the needs of older adults when developing guidelines on preventive services.WHAT DOES THIS IMPORTANT STUDY SHOW?The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)issues evidence-based recommendations for screen-ing and prevention.Its recommendations are devel-oped using an evidence-based framework that guides the approach and scope of systematic evidence re-view.The USPSTF convened a geriatric subgroup of its methods work group to address challenges in topic prioritization,evidence review,and guideline develop-ment regarding preventive services for older adults.The article by Leipzig et al on behalf of this group 11and its accompanying editorial 12refer to and build on the USPSTF’s systematic review of fall prevention in geriatric populations.13The USPSTF proposes 3new approaches,stating that selection of the most appropri-ate approach for each of its guideline topics will be determined on the basis of the available evidence for the condition under review,an understanding of its natural history and pathophysiologic process,and an understanding of the intervention mechanisms under consideration.First,the USPSTF plans to address issues specific to persons of older age when commissioning a system-atic review for diseases prevalent in older adults (eg,primary care screening for depression).It proposes to specifically consider adults 65years or older and to stratify recommendations according to age.Second,the USPSTF proposes to expand the typi-cal analytic framework when developing recommen-dations concerning geriatric syndromes.In the case of the USPSTF recommendations for prevention of falls,this entailed consideration of several common interre-lated risk factors for falls and functional limitations,along with the various interventions targeting each risk factor.Third,the USPSTF proposes to bundle recommen-dations for related topics to make recommendations more consistent,interlinked,and comprehensive.For example,a guideline for prevention of bone fractures would contain sections with recommendations about calcium and vitamin D supplements,screening for osteoporosis,and prevention of falls.Originally publishedonline June 13,2011.Address correspondence to Katrin Uhlig,MD,MS,Division of Nephrology,Tufts Medical Center,800Washington St,Boston,MA 02111.E-mail:kuhlig@ .©2011by the National Kidney Foundation,Inc.0272-6386/$36.00doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.05.001HOW DOES THIS STUDY COMPARE WITHPRIOR STUDIES?Many guideline recommendations currently focus on only single diseases,do not stratify their recommen-dations for older versus younger adults,do not con-sider burden of comorbid illnesses,or do not specifi-cally state the expected time frame for a favorable risk-benefit ratio.4,6,14-16First,older individuals often are under-represented in clinical trials,thus limiting the quality and scope of direct evidence in this population.However,older adults and individuals with greater comorbidity gener-ally have an increased mortality risk,a greater number of potentially relevant outcomes,and an increased risk of treatment-related adverse events.These factorsare likely to alter benefits and harms of many treat-ments.Furthermore,patients’values regarding the importance of certain outcomes may change as age or the burden of comorbid conditions increases.Second,the traditional framework used by the USPSTF and other guideline development entities usually is based on a linear disease model in which a risk factor is linked to a well-described disease out-come and a simple intervention for the risk factor affects the outcome (Fig 1A).Treatment decisions for individuals with CKD usually are more complex given the higher burden of comorbid diseases,such as hypertension,diabetes,and cardiovascular disease (Fig 1B-C ).Geriatric syndromes also consist of a complex cluster of risk factors that interact witheachFigure 1.Disease models increase in complexity with increasing numbers of disease conditions,treatments,and outcomes considered,such as in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD)or of older age.Circles indicate diseases,rectangles indicate outcomes,and rounded rectangles indicate treatments.Disease model for treatment of (A)hypertension (HTN)without CKD or other comorbid conditions.Disease models for treatment of (B)HTN in patients with CKD;(C)patients with CKD and a cluster of additional common comorbid conditions:HTN,diabetes mellitus (DM),congestive heart failure (CHF),and cardiovascular disease (CVD);(D)patients with CKD and a cluster of geriatric syndromes:functional disability,frailty,and polypharmacy;and (E)older patients with CKD and clusters of common comorbid conditions,as well as geriatric syndromes (the overlap of C and D).Abbreviations:BP,blood pressure;QOL,quality of life.In the Literatureother and variably impact on a spectrum of clinical outcomes and disease states(Fig1D),and this com-plexity is compounded further in the overlap of CKD comorbidities and geriatric syndromes(Fig1E).Im-provements in multifactorial conditions may require multipronged interventions.Along with traditional discrete clinical events,meaningful outcomes for older adults include functional disability and cognitive im-pairment.A major challenge lies in the current lack of routine and standardized collection of valid and respon-sive measures for functional outcomes.Even when available,it is challenging to define clinically mean-ingful differences and compare effects,often on con-tinuous scales,across different outcomes.Third,guidelines for the same topic often are presented in piecemeal fashion.Different guideline developers have ownership of particular diseases, interventions,or outcomes,which may lead to redundancy and differences in recommendations. Bundling of recommendations for a patient with a cluster of diseases requires reconciling the exper-tise of generalists with that of multidisciplinary specialists.WHAT SHOULD CLINICIANS ANDRESEARCHERS DO?The implications of the USPSTF recommendations detailed by Leipzig et al are directly applicable to guideline development and clinical research in nephrol-ogy.Most current evidence-based CKD guidelines pertain to treatment rather than screening.Neverthe-less,the approaches for prevention recommendations for older adults suggested by the USPSTF are relevant to evidence review and guideline development for individuals with CKD.Many patients with CKD are older and there may be important differences in the pathophysiologic process and natural history of CKD for older versus younger adults.5,17,18Following thefirst suggestion of the USPSTF, adults of older age a priori should be a subgroup of interest for clinical practice recommendations about CKD.Evidence review should involve assessment of the degree to which older individuals were included in relevant studies and how risk relationships and treat-ment effects may differ.Harms assessments need to consider alterations in drug metabolism,possible drug interactions,and greater risks from invasive interven-tions in older patients.Estimating the expected bal-ance between benefits and harms needs to consider older adults’overall shorter life expectancy versus the chronicity of the disease and the possibility of differ-ent preferences or values regarding treatment goals. Recommendations for older adults with CKD may need to be worded differently or assigned a different strength.Going forward,older adults should consti-tute prespecified subgroups in trials and cohort studies of CKD.To overcome limitations of subgroup effects, risk-stratification tools should incorporate age along with level of estimated glomerularfiltration rate and albuminuria and other risk factors to more comprehen-sively categorize risks and explore the heterogeneity of treatment effects.14,19Following the second USPSTF recommendation, CKD guidelines need to address topics of particular importance to older individuals,for example,func-tional disability,frailty,falls,polypharmacy,depres-sion,and decision making regarding renal replacement therapy,among others.Outcome measures that will reliably assess quality of life and functional performance in meaningful increments need to be studied.20Future research needs to evaluate the preferences of individuals with CKD and the value that these individuals attach to various states of health and risk,along with the degree of variability and factors that impact on these preferences and values,such as older age.21 Finally,as suggested by the USPSTF,we need to reconcile and prioritize across myriad guidelines for the same target population.Weighing the relative merits of various strategies necessitates stepping back from a focus on a particular intervention or outcome and shifting to a focus on improving overall health and survival.Synthesis of research evidence across various interventions requires advances in methods to deal with indirect comparisons and combine dispa-rate benefits and harms.In guideline groups,this widens both the scope and needed clinical and method expertise.Regardless,any guideline panel attempting to extrapolate imperfect evidence to a complex patient,be it an older adult or a patient with CKD,will need to exercise more judgment than for simpler target populations.Guideline users will have to accept that differences of opinion will alter assessments and recommendations,as might future research.Guideline developers bear the re-sponsibility of transparently communicating uncer-tainty and judgments to their audience.Katrin Uhlig,MD,MSTufts Medical CenterBoston,MassachusettsCynthia Boyd,MD,MPH Johns Hopkins University School of MedicineBaltimore,MarylandACKNOWLEDGEMENTSWe thank Jenny Lamont,MS,for editorial support and help drafting thefigure.Dr Boyd is supported by the Paul Beeson Career Development Award Program(NIA K23AG032910,AFAR,the John A.Hart-ford Foundation,the Atlantic Philanthropies,the Starr Foundation,Uhlig and Boydand an anonymous donor),the Robert Wood Johnson Physician Faculty Scholars Program,and the Johns Hopkins Bayview Center for Innovative Medicine.Financial Disclosure:Dr Uhlig is supported by the National Kidney Foundation for conducting evidence reviews and provid-ing methods support for KDIGO(Kidney Disease:Improving Global Outcomes)guidelines.Drs Uhlig and Boyd are supported by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality to develop an approach for improving clinical practice guidelines for complex patients(AHRQ R21HS18597-01).REFERENCES1.Levey AS,Stevens LA,Schmid CH,et al.A new equation to estimate glomerularfiltration rate.Ann Intern Med.2009;150(9): 604-612.2.Stevens LA,Coresh J,Levey AS.CKD in the elderly—old questions and new challenges:World Kidney Day2008.Am J Kidney Dis.2008;51(3):353-357.3.Uhlig K,Balk EM,Lau J,Levey AS.Clinical practice guidelines in nephrology—for worse or for better.Nephrol Dial Transplant.2006;21(5):1145-1153.4.Boyd CM,Darer J,Boult C,Fried LP,Boult L,Wu AW. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases:implications for pay for perfor-mance.JAMA.2005;294(6):716-724.5.O’Hare AM,Kaufman JS,Covinsky KE,Landefeld CS, McFarland LV,Larson EB.Current guidelines for using angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II-receptor antago-nists in chronic kidney disease:is the evidence base relevant to older adults?Ann Intern Med.2009;150(10):717-724.6.Shaneyfelt TM,Centor RM.Reassessment of clinical prac-tice guidelines:go gently into that good night.JAMA.2009;301(8): 868-869.7.Petitti DB,Teutsch SM,Barton MB,et al.Update on the methods of the U.S.Preventive Services Task Force:insufficient evidence.Ann Intern Med.2009;150(3):199-205.8.Balk EM,Uhlig ing GRADE for international guide-lines on kidney disease.2010./expert/ expert-commentary.aspx?idϭ16436.Accessed February23,2011.9.VanLare JM,Conway PH,Sox HC.Five next steps for a new national program for comparative-effectiveness research.N Engl J Med.2010;362(11):970-973.10.Boyd C,Leff B,Kent D,Uhlig K.A framework to improve guidelines for patients with multimorbidity[abstract].Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg.2010;143:42.11.Leipzig RM,Whitlock EP,Wolff TA,et al;for the US Preventive Services Task Force Geriatric Workgroup.Reconsider-ing the approach to prevention recommendations for older adults. Ann Intern Med.2010;153(12):809-814.12.Tinetti ME.Making prevention recommendations relevant for an aging population.Ann Intern Med.2010;153(12):843-844.13.Michael YL,Whitlock EP,Lin JS,Fu R,O’Connor EA, Gold R;US Preventive Services Task Force.Primary care-relevant interventions to prevent falling in older adults:a systematic evi-dence review for the U.S.Preventive Services Task Force.Ann Intern Med.2010;153(12):815-825.14.Kent DM,Hayward RA.Limitations of applying summary results of clinical trials to individual patients:the need for risk stratification.JAMA.2007;298(10):1209-1212.15.Greenfield S,Kravitz R,Duan N,Kaplan SH.Heterogene-ity of treatment effects:implications for guidelines,payment,and quality assessment.Am J Med.2007;120(4)(suppl1):S3-9.16.Scott IA,Guyatt GH.Cautionary tales in the interpretation of clinical studies involving older persons.Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(7):587-595.17.O’Hare AM,Choi AI,Bertenthal D,et al.Age affects outcomes in chronic kidney disease.J Am Soc Nephrol.2007; 18(10):2758-2765.18.Murtagh FE,Addington-Hall JM,Higginson IJ.End-stage renal disease:a new trajectory of functional decline in the last year of life.J Am Geriatr Soc.2011;59(2):304-308.19.Kent DM,Rothwell PM,Ioannidis JP,Altman DG,Hayward RA.Assessing and reporting heterogeneity in treatment effects in clinical trials:a proposal.Trials.2010;11:85.20.No authors listed.Patient-reported outcomes in clinical trials of chronic kidney disease-related therapies.Workshop co-sponsored by the National Kidney Foundation and the US Food and Drug Administration.2011./profession-als/physicians/ProConference.cfm.Accessed March15,2011. 21.Butler M,Talley KMC,Burns R,et al.Prevention in Older Adults:Values in Older Adults Related to Primary and Secondary Prevention.Rockville,MD:Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality;2011.In the Literature。

2013美国成人超重和肥胖管理指南

2021 AHA/ACC/TOS成人超重和肥胖管理指南:美国心脏病学会/美国心脏协会实践指南专责组/肥胖协会报告2021 AHA/ACC/TOS Guideline for the Management of Overweight and Obesity in Adults:A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines andThe Obesity SocietyMichael D. Jensen, Donna H. Ryan, Caroline M. Apovian, Jamy D. Ard, Anthony G. Comuzzie, Karen A. Donato, Frank B.Hu, Van S. Hubbard, John M. Jakicic, Robert F. Kushner, Catherine M. Loria, Barbara E. Millen, Cathy A. Nonas, F.Xavier Pi-Sunyer, June Stevens, Victor J. Stevens, Thomas A. Wadden, Bruce M. Wolfe and Susan Z. YanovskiCirculation. published online November 12, 2021;Circulation is published by the American Heart Association, 7272 Greenville Avenue, Dallas, TX 75231Copyright © 2021 American Heart Association, Inc. All rights reserved.Print ISSN:0009-7322. Online ISSN: 1524-4539本文网上版与更新信息和效劳,位于互联网:Data Supplement (unedited) a2021 AHA/ACC/TOS成人超重和肥胖管理指南美国心脏病学会/美国心脏协会实践指南专责组/肥胖协会报告美国心肺康复协会〔American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation〕,美国药师协会〔American Pharmacists Association〕,美国营养协会〔American Society for Nutrition〕,美国预防心脏病协会〔American Society for Preventive Cardiology〕,美国高血压协会〔American Society of Hypertension〕,黑人心脏病医生协会〔Association of Black Cardiologists〕,全国血脂协会〔National Lipid Association〕,预防心血管护理协会〔Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association〕,内分泌协会〔The Endocrine Society〕和妇女心脏〔WomenHeart〕:全国妇女心脏病联合会〔The National Coalition for Women with Heart Disease〕认可专家组成员Michael D. Jensen, MD, Co-ChairDonna H. Ryan, MD, Co-ChairCaroline M. Apovian, MD, Catherine M. Loria, PhD,FACP FAHA*Jamy D. Ard, MD Barbara E. Millen, DrPH, RD Anthony G. Comuzzie, PhD Cathy A. Nonas, MS, RD Karen A. Donato, SM* F. Xavier Pi-Sunyer, MD,MPHFrank B. Hu, MD, PhD,FAHAJune Stevens, PhDVan S. Hubbard, MD, PhD*Victor J. Stevens, PhD John M. Jakicic, PhD Thomas A. Wadden, PhD Robert F. Kushner, MD Bruce M. Wolfe, MD Susan Z. Yanovski, MD*方法学成员Harmon S. Jordan, ScDKarima A. Kendall, PhDLinda J. LuxRoycelynn Mentor-Marcel, PhD,MPHLaura C. Morgan, MAMichael G. Trisolini, PhD, MBAJanusz Wnek, PhDACCF/AHA专责组成员Jeffrey L. Anderson, MD, FACC, FAHA, ChairJonathan L. Halperin, MD, FACC, FAHA, Chair-ElectNancy M. Albert, PhD, CCNS, CCRN, FAHA Judith S. Hochman, MD, FACC, FAHABiykem Bozkurt, MD, PhD, FACC, FAHA Richard J. Kovacs, MD, FACC, FAHARalph G. Brindis, MD, MPH, MACC E. Magnus Ohman, MD, FACCLesley H. Curtis, PhD, FAHA Susan J. Pressler, PhD, RN, FAAN,FAHADavid DeMets, PhD Frank W. Sellke, MD, FACC, FAHARobert A. Guyton, MD, FACC Win-Kuang Shen, MD, FACC, FAHA预防指南分会Sidney C. Smith, Jr, MD, FACC, FAHA, ChairGordon F. Tomaselli, MD, FACC, FAHA, Co-Chair*当然委员。

美国心脏协会美国心脏病学会胆固醇管理指南要点

美国心脏协会/美国心脏病学会胆固醇管理指南要点2018年11月10日在芝加哥召开的美国心脏协会(AHA)科学年会上,2018 AHA/美国心脏病学会(ACC)联手发布了新版胆固醇管理指南(“新指南”,下同)。

新指南在2013版指南基础上结合最新临床研究证据进行更新,强调健康生活方式和预防,突出基于心血管风险的个体化治疗策略,并对非他汀类降低胆固醇药物如依折麦布、前蛋白转化酶枯草溶菌素9(PCSK9)抑制剂等给予了推荐。

一、新指南要点:(一)强调所有人都应保持心脏健康的生活方式,以降低动脉粥样硬化性心血管疾病(ASCVD)风险。

在20~39岁的年轻人中,终生风险(lifetime risk)评估有助于临床医生与患者间的风险讨论,并强调努力改善生活方式。

对所有年龄段的人来说,生活方式治疗是代谢综合征的主要干预措施。

(二)在临床ASCVD患者中,使用高强度他汀治疗或最大耐受剂量的他汀治疗以降低低密度脂蛋白胆固醇(LDL-C),LDL-C自基线应降低≥50%。

(三)极高危的ASCVD患者,包括多个严重ASCVD事件史或1个严重ASCVD事件史和多个高风险因素,如果使用最大耐受剂量的他汀治疗后,LDL-C水平仍≥70mg/dL(≥1.8mmol/L),加用依折麦布是合理的;如果使用最大耐受剂量的他汀和依折麦布治疗后,LDL-C水平仍≥70mg/dL(≥1.8mmol/L),加用PCSK9抑制剂是合理的,但长期(>3年)安全性还不确定,而且基于2018年前半年的价格,其成本效益很低。

(四)对于未计算10年ASCVD风险的严重原发性高胆固醇血症患者[LDL-C≥190mg/dL(≥4.9mmol/L)],可以直接启动高强度他汀治疗。

如果LDL-C水平仍≥100mg/dL(≥2.6mmol/L),加用依折麦布是合理的。

如果在他汀+依折麦布治疗后,LDL-C水平仍≥100mg/dL(≥2.6mmol/L),且患者有多种因素会增加后续的ASCVD事件风险,可考虑使用PCSK9抑制剂,但基于前述(第3条)原因,其经济学价值较低。