An Accelerated Lambda Iteration Method for Multilevel Radiative Transfer III. Noncoherent E

物理学名词

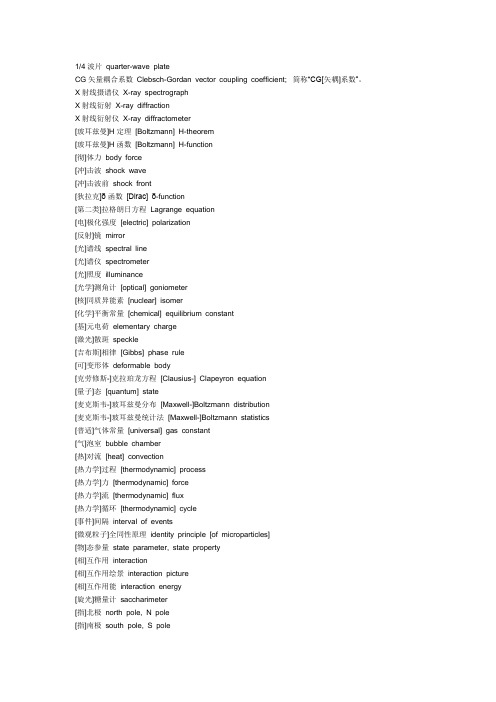

1/4波片quarter-wave plateCG矢量耦合系数Clebsch-Gordan vector coupling coefficient; 简称“CG[矢耦]系数”。

X射线摄谱仪X-ray spectrographX射线衍射X-ray diffractionX射线衍射仪X-ray diffractometer[玻耳兹曼]H定理[Boltzmann] H-theorem[玻耳兹曼]H函数[Boltzmann] H-function[彻]体力body force[冲]击波shock wave[冲]击波前shock front[狄拉克]δ函数[Dirac] δ-function[第二类]拉格朗日方程Lagrange equation[电]极化强度[electric] polarization[反射]镜mirror[光]谱线spectral line[光]谱仪spectrometer[光]照度illuminance[光学]测角计[optical] goniometer[核]同质异能素[nuclear] isomer[化学]平衡常量[chemical] equilibrium constant[基]元电荷elementary charge[激光]散斑speckle[吉布斯]相律[Gibbs] phase rule[可]变形体deformable body[克劳修斯-]克拉珀龙方程[Clausius-] Clapeyron equation[量子]态[quantum] state[麦克斯韦-]玻耳兹曼分布[Maxwell-]Boltzmann distribution[麦克斯韦-]玻耳兹曼统计法[Maxwell-]Boltzmann statistics[普适]气体常量[universal] gas constant[气]泡室bubble chamber[热]对流[heat] convection[热力学]过程[thermodynamic] process[热力学]力[thermodynamic] force[热力学]流[thermodynamic] flux[热力学]循环[thermodynamic] cycle[事件]间隔interval of events[微观粒子]全同性原理identity principle [of microparticles][物]态参量state parameter, state property[相]互作用interaction[相]互作用绘景interaction picture[相]互作用能interaction energy[旋光]糖量计saccharimeter[指]北极north pole, N pole[指]南极south pole, S pole[主]光轴[principal] optical axis[转动]瞬心instantaneous centre [of rotation][转动]瞬轴instantaneous axis [of rotation]t 分布student's t distributiont 检验student's t testK俘获K-captureS矩阵S-matrixWKB近似WKB approximationX射线X-rayΓ空间Γ-spaceα粒子α-particleα射线α-rayα衰变α-decayβ射线β-rayβ衰变β-decayγ矩阵γ-matrixγ射线γ-rayγ衰变γ-decayλ相变λ-transitionμ空间μ-spaceχ 分布chi square distributionχ 检验chi square test阿贝不变量Abbe invariant阿贝成象原理Abbe principle of image formation阿贝折射计Abbe refractometer阿贝正弦条件Abbe sine condition阿伏伽德罗常量Avogadro constant阿伏伽德罗定律Avogadro law阿基米德原理Archimedes principle阿特伍德机Atwood machine艾里斑Airy disk爱因斯坦-斯莫卢霍夫斯基理论Einstein-Smoluchowski theory 爱因斯坦场方程Einstein field equation爱因斯坦等效原理Einstein equivalence principle爱因斯坦关系Einstein relation爱因斯坦求和约定Einstein summation convention爱因斯坦同步Einstein synchronization爱因斯坦系数Einstein coefficient安[培]匝数ampere-turns安培[分子电流]假说Ampere hypothesis安培定律Ampere law安培环路定理Ampere circuital theorem安培计ammeter安培力Ampere force安培天平Ampere balance昂萨格倒易关系Onsager reciprocal relation凹面光栅concave grating凹面镜concave mirror凹透镜concave lens奥温电桥Owen bridge巴比涅补偿器Babinet compensator巴耳末系Balmer series白光white light摆pendulum板极plate伴线satellite line半波片halfwave plate半波损失half-wave loss半波天线half-wave antenna半导体semiconductor半导体激光器semiconductor laser半衰期half life period半透[明]膜semi-transparent film半影penumbra半周期带half-period zone傍轴近似paraxial approximation傍轴区paraxial region傍轴条件paraxial condition薄膜干涉film interference薄膜光学film optics薄透镜thin lens保守力conservative force保守系conservative system饱和saturation饱和磁化强度saturation magnetization本底background本体瞬心迹polhode本影umbra本征函数eigenfunction本征频率eigenfrequency本征矢[量] eigenvector本征振荡eigen oscillation本征振动eigenvibration本征值eigenvalue本征值方程eigenvalue equation比长仪comparator比荷specific charge; 又称“荷质比(charge-mass ratio)”。

风云卫星数据和产品应用手册讲解

风云卫星数据和产品应用手册第1章概述1.1 FY-3A卫星概况风云三号A气象卫星(简称FY-3A)是我国的第二代太阳同步极轨气象卫星。

风云三号气象卫星将实现全球、全天候、多光谱、三维、定量对地观测。

风云三号星发射总质量为2450kg,发射尺寸:4.38m×2m×2m,卫星长期功耗1130W。

卫星本体由服务舱、推进舱与有效载荷舱组成。

服务舱采用中心承力筒和隔板结构,主要安装电源、测控、数管及姿轨控分系统的部件和设备、推进舱采用中心承筒和隔板结构,主要安装推进系统设备以及蓄电池组和放电调节器。

有效载荷舱隔板和构架结构,主要安装探测仪器的探测头部,舱内主要安装探测仪器的电子设备等。

风云三号A卫星有十一台遥感探测仪器。

遥感数据通过两个实时传输信道(HRPT和MPT)和一个延时传输信道(DPT)进行传输。

风云三号A卫星设计寿命为3年。

1.2 主要技术指标1.2.1 卫星轨道⑴轨道类型:近极地太阳同步轨道⑵轨道标称高度:831公里⑶轨道倾角:98.81°⑷入轨精度:半长轴偏差: |Δa|≤5公里轨道倾角偏差:|Δi|≤0.1°轨道偏心率≤0.003⑸标称轨道回归周期为5.79天⑹轨道保持偏心率:≤0.00013⑺交点地方时漂移:2年小于15分钟⑻卫星发射窗口:降交点地方时10:051.2.2 卫星姿态⑴姿态稳定方式:三轴稳定⑵三轴指向精度:≤0.3°⑶三轴测量精度:≤0.05°⑷三轴姿态稳定度:≤4×10-3 °/s1.2.3 太阳帆板对日定向跟踪1.2.4 星上记时⑴记时方式:J2000日计数和日毫秒计数⑵记时单位:1毫秒⑶时间精度(星地总精度):小于20毫秒1.2.5 遥感探测仪器性能指标1.2.5.1 可见光红外扫描辐射计(VIRR)(1)通道数、各通道波段范围、灵敏度见表1-1。

(2)空间分辨率:星下点分辨率1.1Km(3)扫描范围:±55.4°(4)扫描器转速:6线/秒(5)每条扫描线采样点数:2048(6)MTF≥0.3(7)通道配准:飞行方向/扫描方向星下点配准精度<0.5个像元(8)扫描抖动:<0.8个IFOV(9)通道信号衰减:<15%/2年(10)量化等级:10比特(11)定标精度:可见光和近红外通道:CH1、2、7、8、9 7%(反射率)CH6、10 10%(反射率)红外通道:1k(270k)。

高温气冷堆用碳毡材料导热系数测量及反问题计算

原

子ห้องสมุดไป่ตู้

能

科

学

技

术

$ % & ' ! " ( % ' # # ( % ; ' ) * # !

+ , % . /0 1 2 3 / . 2 1 / 27 1 89 2 / : 1 % & % 4 56 4 5

高温气冷堆用碳毡材料导热系数测量 及反问题计算

李聪新 任!成 杨星团 " 姜胜耀 孙艳飞

清华大学 核能与新能源技术研究院 先进反应堆工程与安全教育部重点实验室 北京 !# * * * " !

摘要 碳纤维材料已成为核能 航天等领域不可或缺 的 重 要 功 能 材 料 在高温气冷堆及其相关实验中需 要使用大量碳纤维保温材料 但由于目前测试方法的限制 相关材料物性参数测量数 据 严 重 不 足 尤其 是缺乏高温 #* 致其使用受到限制 为此 清华大 学 核 能 与 新 能 源 技 术 研 究 院 * * h 以上的热物性参数 研制了模拟高温气冷堆温度 环境氛围的材料测试装置 可提供 #@ * * h以下的材料性能测试根据该 详细介绍了采用 非 线 性 导 热 反 问 题 方 法 确 定 材 料 温 度 相 关 导 热 系 装置一次典型实验过程的测量数据 非稳态热传导原理求解反问题的简 明 算 法 该方法既 数的完整过程和具体算法 提出了一种依据稳态 也可为其他反问题算法提供良好的迭 代 初 值 实 验 确 定 了 高 温 气 冷 堆 用 碳 毡 保 温 材 料 在 可单独使用 将为高温气冷堆相关实验和其他特高温条件下的应用提供重要参考 #@ * * h 以下的导热系数 关键词 高温气冷堆 碳毡保温材料 高温 导热系数 导热反问题 中图分类号 9 = B B )!!! 文献标志码 +!!! 文章编号 # * * * ? @ A B # ) * # ! # # ? # A C @ ? * A D G' ) * # !' % F Q . 7 1 ' * * * > ! " # # *' C > B " 5 5

Ansys热分析教程(全)

章节内容概述

• 第7章-续 – 例题 6 - 低压气轮机箱的热分析

• 第 8 章 - 辐射 – 辐射概念的回顾 – 基本定义 – 辐射建模的可选择方法 – 辐射矩阵模块 – 辐射分析例题 - 使用辐射矩阵模块进行热沉分析,隐式和非隐式方 法。

• 第 9 章 - 相变 – 基本模型/术语 – 在 ANSYS中求解相变 – 相变例题 - 飞轮铸造分析

传导

• 传导的热流由传导的傅立叶定律决定:

q*

=

− Knn

∂T ∂n

=

heat

flow

rate

per

unit

area

in

direction

n

Where, Knn = thermal conductivity in direction n

T = temperature

∂T = thermal gradient in direction n ∂n

• 负号表示热沿梯度的反向流动(i.e., 热从热的部分流向冷的).

q*

T

dT

dn

n

对流

• 对流的热流由冷却的牛顿准则得出:

q* = hf (TS − TB ) = heat flow rate per unit area between surface and fluid

Where, hf = convective film coefficient TS = surface temperature TB = bulk fluid temperature

• 第 6 章 - 复杂的, 时间和空间变化的边界条件 – 表格化的热边界条件 (载荷) – 基本变量 – 用户定义的因变变量

章节内容概述

2046 J. Opt. Soc. Am. AVol. 20, No. 11November 2003 Martí-López et al.

London WC1E 6JA, UK

Simon R. Arridge Department of Computer Science, University College London, Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT, UK

OCIS codes: 170.5280, 290.7050, 290.1990.

1. INTRODUCTION

Optical tomography (OT) deals with the problem of retrieving spatial functions of internal physical properties of a body from a set of optical measurements.1 Examples of such functions are scattering and absorption coefficients (in biomedical applications) or the refractive index (in plasma physics research). Since biological tissues are relatively low absorbing in the optical window ranging from ϭ 700 nm to ϭ 1000 nm, most medical applications of OT are carried out in that range. Unfortunately, most biological tissues also strongly scatter light, which represents a serious problem for viewing the body’s internal structures and characterizing biological processes by optical methods.2–4

氨基酸的结晶

Crystallization of Amino Acids on Self-AssembledMonolayers of Rigid Thiols on GoldAlfred Y.Lee,†,‡Abraham Ulman,†,§and Allan S.Myerson*,‡Department of Chemical and Environmental Engineering,Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago,Illinois60616,and Department of Chemical Engineering,Chemistry and Material Science,and the NSF MRSEC for Polymers at Engineered Interfaces,Polytechnic University,Brooklyn,New York11201Received March6,2002.In Final Form:May3,2002Self-assembled monolayers(SAMs)of rigid biphenyl thiols are employed as heterogeneous nucleants for the crystallization of L-alanine and DL-valine.Powder X-ray diffraction and interfacial angle measurements reveal that the L-alanine crystallographic planes corresponding to nucleation are{200}, {020},and{011}on SAMs of4′-hydroxy-(4-mercaptobiphenyl),4′-methyl-(4-mercaptobiphenyl),and4-(4-mercaptophenyl)pyridine on gold(111)surfaces,respectively.In the case of DL-valine,monolayer surfaces that act as hydrogen bond acceptors(e.g.,4′-hydroxy-(4-mercaptobiphenyl)and4-(4-mercaptophenyl)-pyridine)induce the racemic crystal to nucleate from the{020}plane whereas the nucleating plane for the4′-methyl-(4-mercaptobiphenyl)surface is the fast-growing{100}face.The observation of crystal nucleation and orientation can be attributed to the strong interfacial interactions,in particular,hydrogen bonding,between the surface functionalities of the monolayer film and the individual molecules of the crystallizing phase.Molecular modeling studies are also undertaken to examine the molecular recognition process across the interface between the surfactant monolayer and the crystallographic planes.Similar to binding studies of solvents and impurities on crystal habit surfaces,binding energies between SAMs and particular amino acid crystal faces are calculated and the results are in good agreement with the observed nucleation planes of the amino acids.In addition to L-alanine and DL-valine,the interaction of SAMs and mixed SAMs of rigid thiols on the morphology of R-glycine is examined(Kang,J.F.;Zaccaro, J.;Ulman,A.;Myerson,ngmuir2000,16,3791),and similarly the calculations are in good agreement. These results suggest that binding energy calculations can be a valid method to screen self-assembled monolayers as potential templates for nucleation and growth of organic and inorganic crystals.I.IntroductionCrystallization from solution is a two-step process: nucleation,the birth of a crystal,and crystal growth,the growth of the crystal to larger sizes.2In this process, prenucleation aggregates(or clusters)are formed by individual molecules,which become stable nuclei,upon reaching a critical size,and further grow into macroscopic crystals.Homogeneous nucleation is very rare and re-quires high supersaturation to surmount the activation barrier,∆G crit.However,for a fixed supersaturation the activation barrier can be lowered by decreasing the surface energy of the aggregate,for instance,by introducing a foreign surface or substance.3This foreign surface(or substance)includes“tailor-made”additives,4impurities,5 organic single crystals,6Langmuir monolayers7floating at the air-water interface,and self-assembled monolayers (SAMs)immersed in solution.1Tailor-made additives or auxiliaries are designer impurities that have one part which resembles the crystallizing species and another part that is chemically or structurally different from the solute molecule.4,8These additives disrupt the bonding sequence in the crystals,thereby lowering the growth rate of the affected faces as evident in the case of L-alanine where hydrophobic amino acids such as L-leucine and L-valine inhibited the development of specific crystal faces,while in the presence of hydrophilic amino acids the crystal morphology did not change.9In addition to being habit modifiers,these molecular additives can also control polymorphism,where the impurities inhibit the growth of one polymorph and,in turn,promote the growth of the other polymorph.10Nucleation promoters such as organic single crystals and self-assembled monolayers have also been used to control polymorph selectivity,based on geometric match-ing between the molecular clusters and the ledges of the crystal substrates11and interfacial hydrogen bonding between the monolayer film and solute clusters,12respec-*To whom correspondence should be addressed.Phone:312 5677010.Fax:3125677018.E-mail:myerson@.†Polytechnic University.‡Illinois Institute of Technology.§NSF MRSEC for Polymers at Engineered Interfaces.(1)Kang,J.F.;Zaccaro,J.;Ulman,A.;Myerson,ngmuir2000, 16,3791.(2)(a)Myerson,A.S.Handbook of Industrial Crystallization,2nd ed.;Butterworth-Heinemann:Boston,2002.(b)Myerson,A.S.Mo-lecular Modeling Applications in Crystallization;Cambridge Uni-versity Press:New York,1999.(c)Mullin,J.W.Crystallization,4th ed.;Butterworth-Heinemann:Boston,2001.(3)Turnbull,D.J.Chem.Phys.1949,18,198.(b)Fletcher,N.H.J. Chem.Phys.1963,38,237.(4)Weissbuch,I.;Lahav,M.;Leiserowitz,L.In Molecular Modeling Applications in Crystallization;Myerson, A.S.,Ed.;Cambridge University Press:New York,1999;p166.(5)Meenan,P.A.;Anderson,S.R.;Klug,D.L.In Handbook of Industrial Crystallization,2nd ed.;Myerson,A.S.,Ed.;Butterworth Heinemann:Boston,2002;p67.(6)Carter,P.W.;Ward,M.D.J.Am.Chem.Soc.1993,115,11521.(7)(a)Rapaport,H.;Kuzmenko,I.;Berfeld,M.;Kjaer,K.;Als-Nielsen, J.;Popovitz-Biro,R.;Weissbuch,I.;Lahav,M.;Leiserowitz,L.J.Phys. Chem.B2000,104,1399.(b)Frostman,L.M.;Ward,ngmuir 1997,13,330.(8)(a)Berkovitch-Yellin,Z.;Ariel,S.;Leiserowitz,L.J.Am.Chem. Soc.1985,105,765.(b)Addadi,L.;Weinstein,S.;Gate,E.;Weissbuch,I.;Lahav,M.J.Am.Chem.Soc.1982,104,4610.(9)Li,L.;Lechuga-Ballesteros,D.;Szkudlarek,B.A.;Rodriguez-Hornedo,N.J.Colloid Interface Sci.1994,168,8.(10)(a)Weissbuch,I.;Lahav,M.;Leiserowitz,L.Adv.Mater.1994, 6,952.(b)Davey,R.J.;Blagden,N.;Potts,G.D.;Docherty,R.J.Am. Chem.Soc.1997,119,1767.5886Langmuir2002,18,5886-589810.1021/la025704w CCC:$22.00©2002American Chemical SocietyPublished on Web06/22/2002tively.Similar to Langmuir monolayers,self-assembled monolayers can be used as an interface across which stereochemical matching13and hydrogen bonding14in-teraction can transfer order and symmetry from the monolayer surface to a growing crystal.However,SAMs and mixed SAMs15lack the mobility of molecules at an air-water interface and hence the possibility to adjust lateral positions to match a face of a nucleating crystal. This is clearly evident in the case of the SAMs of rigid biphenyl thiols,where even conformational adjustment is not possible.Recently,SAMs of4-mercaptobiphenyl have been shown to be more superior to those of al-kanethiolates and are stable model surfaces.16Further-more,the ability to engineer surface functionalities at the molecular level makes SAMs of rigid thiols very attractiveas templates for heterogeneous nucleation. Organosilane monolayer films have been used to promote nucleation and growth of calcium oxalate mono-hydrate crystals17and have been employed in“biomimetic”synthesis as observed in the oriented growth of CaCO318 and iron hydroxide crystals.19Functionalized SAMs of alkanethiols have also been shown to control the oriented growth of CaCO3.20This was also evident in the hetero-geneous nucleation and growth of malonic acid crystals21 on alkanethiolate SAMs on gold where the monolayer composition strongly influenced the orientation of the malonic acid crystals.Additionally,functionalized alkane-thiolate SAMs have enhanced the growth of protein crystals.22More recently,SAMs and mixed SAMs of rigid thiols served as templates.1It was observed that glycine nucleated in the R-form independent of the hydroxyl and pyridine surface concentration and the morphology of the glycine crystal was very sensitive to the OH and pyridine site densities.Self-assembled monolayers on solid surfaces offer many advantages for enhanced crystal nucleation.In this work, SAMs of rigid thiols on gold are employed to investigate the effects of interfacial molecular recognition on nucle-ation and growth of L-alanine and DL-valine crystals.In addition,molecular modeling techniques are employed to examine the affinity between monolayer surfaces and particular amino acid crystal faces and to gain a better understanding of the molecular recognition events oc-curring.The modeling techniques employed are similar to studies of solvent and additive interactions on crystal habit23but have never been applied to organic monolayer films as templates for nucleation.II.Experimental SectionMaterials.Anhydrous ethanol was obtained from Pharmco (Brookfield,CT).L-Alanine(CH3CH(NH2)CO2H),and DL-valine ((CH3)2CHCH(NH2)CO2H)were purchased from Aldrich and used without further purification.Distilled water purified with a Milli-Q water system(Millipore)was used.Details of the synthesis of the4′-substituted4-mercaptobiphenyl(see Figure1)are described elsewhere.24Gold Substrate and Monolayer Preparation.Glass slides were cleaned in ethanol in an ultrasonic bath at40°C for10min. The slides were next treated in a plasma chamber at an argon pressure of0.1Torr for30min.Afterward,they were mounted in the vacuum evaporator(Key High Vacuum)on a substrate holder,approximately15cm above the gold cluster.The slides were baked overnight in a vacuum(10-7Torr)at300°C.Gold (purity>99.99%)was evaporated at a rate of3-5Å/s until the film thickness reached1000Å;the evaporation rate and film thickness were monitored with a quartz crystal microbalance (TM100model from Maxtek Inc.).The gold substrates were annealed in a vacuum at300°C for18h.After cooling to room temperature,the chamber was filled with high-purity nitrogen and the gold slides were either placed into the adsorbing solution right after the ellipsometric measurement was performed or stored in a vacuum desiccator for later use.25Atomic force microscopy(AFM)studies24revealed terraces of Au(111)with typical crystalline sizes of0.5-1µm2.Monolayers were formed by overnight(∼18h)immersion of clean substrates in10µm ethanol solutions of the thiols.The substrates were removed from the solution,rinsed with copious amounts of absolute ethanol to remove unbound thiols,and blown dry with a jet of nitrogen. Contact angle measurements,IR spectroscopy,and ellipsometry showed that after1h,90%or more of the SAMs are formed.26 Thus,to ensure equilibrium SAMs,the gold substrates were left overnight in the dipping solution.Crystal Growth.Nucleation and growth experiments were carried out in Quartex jars(1oz.)at25°C.Supersaturated solutions(25%)of L-alanine and DL-valine were obtained by dissolving 4.58g and 1.95g in22.0g of Millipore water, respectively.The solutions were heated to65°C for90min in an ultrasonic bath to obtain complete dissolution.The solutions were cooled to room temperature for90min before the SAMs were carefully introduced and aligned vertically to the wall. Macrocrystals of L-alanine and DL-valine nucleated at the surfaces(11)(a)Bonafede,S.J.;Ward,M.D.J.Am.Chem.Soc.1995,117, 7853.(b)Mitchell,C.A.;Yu,L.;Ward,M.D.J.Am.Chem.Soc.2001, 123,10830.(12)Carter,P.W.;Ward,M.D.J.Am.Chem.Soc.1994,116,769.(13)(a)Landau,E.M.;Levanon,M.;Leiserowitz,L.;Lahav,M.;Sagiv, J.Nature1985,318,353.(b)Weissbuch,I.;Berfeld,M.;Bouwman,W.; Kjaer,K.;Als,J.;Lahav,M.;Leiserowitz,L.J.Am.Chem.Soc.1997, 119,933.(14)Weissbuch,I.;Popvitz,R.;Lahav,M.;Leiserowitz,L.Acta Crystallogr.1995,B51,115.(15)For a review on SAMs of thiols on gold see:(a)Ulman,A.An Introduction to Ultrathin Organic Films:From Langmuir-Blodgett to Self-Assembly;Academic Press:Boston,1991.(b)Ulman,A.Chem. Rev.1996,96,1533.(16)(a)Kang,J.F.;Ulman,A.;Liao,S.;Jordan,R.J.Am.Chem.Soc. 1998,120,9662.(b)Kang,J.F.;Jordan,R.;Ulman,ngmuir1998,14,3983.(17)Campbell,A.A.;Fryxell,G.E.;Graff,G.L.;Rieke,P.C.; Tarasevich,B.J.Scanning Microsc.1993,7(1),423.(18)Archibald,D.D.;Qadri,S.B.;Gaber,ngmuir1996,12, 538.(19)Tarasevich,B.J.;Rieke,P.C.;Liu,J.Chem.Mater.1996,8,292.(20)Aizenberg,J.;Black,A.J.;Whitesides,G.M.J.Am.Chem.Soc. 1999,121,4500.(21)Frostman,L.M.;Bader,M.M.;Ward,ngmuir1994, 10,576.(22)Ji,D.;Arnold,C.M.;Graupe,M.;Beadle,E.;Dunn,R.V.;Phan, M.N.;Villazana,R.J.;Benson,R.;Colorado,R.,Jr.;Lee,T.R.;Friedman, J.M.J.Cryst.Growth2000,218,390.(23)(a)Docherty,R.;Meenan,P.In Molecular Modeling Applications in Crystallization;Myerson,A.S.,Ed.;Cambridge University Press: New York,1999;p106.(b)Myerson,A.S.;Jang,S.M.J.Cryst.Growth 1995,156,459.(c)Walker,E.M.;Roberts,K.J.;Maginn,ngmuir 1998,14,5620.(d)Evans,J.;Lee,A.Y.;Myerson,A.S.In Crystallization and Solidification Properties of Lipids;Widlak,N.,Hartel,R.W.,Narine, S.,Eds.;AOCS Press:Champaign,IL,2001;p17.(24)Kang,J.F.;Ulman,A.;Liao,S.;Jordan,R.;Yang,G.;Liu,G. Langmuir2001,17,95.(25)(a)Jordan,R.;Ulman,A.J.Am.Chem.Soc.1998,120,243.(b) Jordan,R.;Ulman,A.;Kang,J.F.;Rafailovich,M.;Sokolov,J.J.Am. Chem.Soc.1999,121,1016.(26)Ulman,A.Acc.Chem.Res.2001,34,855.Figure1.Rigid4′-substituted4-mercaptobiphenyls.Crystallization of Amino Acids on Thiol SAMs Langmuir,Vol.18,No.15,20025887and near the edge of the substrates.Only crystals having visible SAM area around them were considered,and the rest were discarded.The chosen crystals attached to the substrates were removed from the solution and stored in a vacuum desiccator for later analysis.Due to the strong adhesion of the crystal face to the SAM surface,gold marks were often observed on the crystal face that nucleated on the SAM surface.Characterization.A Rudolph Research AutoEL ellipsometer was used to measure the thickness of the monolayer surface.The He -Ne laser (632.8nm)light fell at 70°on the sample and reflected into the analyzer.Data were taken over five to seven spots on each sample.The measured thickness of the SAMs of biphenyl thiols ranged from 12to 14Å,assuming a refractive index of 1.462for all films.Powder X-ray diffraction patterns of crystalline L -alanine and DL -valine were obtained with a Rigaku Miniflex diffractometer with Cu K R radiation (λ)1.5418Å).All samples were manually ground into fine powder and packed in glass slides for analysis.Data were collected from 5°to 50°with a step size of 0.1°.Crystal habits of L -alanine and DL -valine were indexed by measuring the interfacial angles using a two-circle optical goniometer.All possible measured interfacial angles were compared with the theoretical values derived from the unit cell parameters of L -alanine and DL -valine crystals.27,28III.Modeling SectionIII.1.General.All of the binding energy calculations,including molecular mechanics and dynamics simulations,are carried out with the program Cerius 2.The overall methodology and procedures are summarized in Figure 2.The crystal structures of each amino acid are obtained from the Cambridge Crystallographic Database (ref codes GLYCIN17,LALNIN12,and VALIDL for R -glycine,L -alanine,and DL -valine,respectively).To accurately predict the crystal morphology,molecular mechanics simulations using a suitable potential function (or force field)are performed.In this work,molecular simulations are carried out using the DREIDING 2.21force field.29The van der Waals forces are approximated with the Lennard-Jones 12-6expression,and hydrogen bonding energy is modeled using a Lennard-Jones-like 12-10expression.The Ewald summation technique is employed for the summation of long-range van der Waals and electrostatic interactions under the periodic boundary conditions,and the charge distribution within the molecule is calculated using the Gasteiger method.30ttice Energy Calculation.The lattice energy E lat,also known as the cohesive or crystal binding energy,is calculated by summing all the atom -atom interactions between a central molecule and all the surrounding molecules in the crystal.If the central molecule and the n surrounding molecules each have n ′atoms,thenwhere V kij is the interaction between atom i in the central molecule and atom j in the k th surrounding parison to the “experimental”lattice energy,V exp ,allows us to assess the accuracy of the intermolecular interactions between the molecules by the defined po-tential function.where the term 2RT represents a compensation factor for the difference between the vibrational contribution to the crystal enthalpy and gas-phase enthalpy 31and ∆H sub is the experimental sublimation energy.III.3.Morphological Predictions.The morphology of each amino acid crystal is predicted using the attach-ment energy (AE)32calculation and the Bravais -Friedel -Donnay -Harker (BFDH)law.33The habit or shape of the crystal depends on the growth rate of the faces present.Faces that are slow growing have the greatest morpho-logical importance,and conversely,faces that are fast growing have the least morphological importance and are the smallest faces on the grown crystal.The simplest morphological simulation is the BFDH law which assumes that the linear growth rate of a given crystal face is inversely proportional to the corresponding interplanar distance after taking into account the extinction conditions of the crystal space group.The attachment energy of a crystal face is the difference between the crystal energy and the slice energy.Hartman and Bennema 32found that the relative growth rate of a face is directly proportional to the attachment energy and as a result,the more negative the attachment energy (or more energy released)for a particular face,the less prominent that face is on the crystal.Conversely,faces with the lowest attachment energies are the slowest growing faces and thus have the greatest morphological importance .III.4.Molecular Modeling of SAMs of 4-Mercapto-biphenyls on a Au(111)Surface.Molecular dynamics (MD)simulations are useful techniques in gaining insights on the structural and dynamical properties of self-assembled monolayers.In contrast to molecular mechan-ics,molecular dynamics computes the forces and moves the atom in response to forces,while molecular mechanics computes the forces on the atoms and changes their position to minimize the interaction energy.Recently,MD simulations have been used to investigate the packing order and orientation of rigid 4-mercaptobiphenyl thiol monolayers on gold surfaces.Results show that hydrogen-terminated biphenylmercaptan packs in the herringbone conformation 34and suggest average tilt angles of 8°.(27)Simpson,H.J.;Marsh,R.E.Acta Crystallogr .1966,20,550.(28)Mallikarjunan,M.;Rao,S.T.Acta Crystallogr .1969,B25,296.(29)Mayo,S.L.;Olafson,B.D.;Goddard,W.A.,III J.Phys.Chem .1990,94,8897.(30)Gasteiger,J.;Marsili,M.Tetrahedron 1980,36,3219.(31)Williams,D.E.J.Phys.Chem .1966,45,3370.(32)(a)Hartman,P.;Bennema,P.J.Cryst.Growth 1980,49,145.(33)(a)Bravais,A.Etudes Crystallographiques ;Gauthier-Villars:Paris,1866.(b)Friedel,M.G.Bulletin de la Societe Francaise de Mineralogie 1907,30,326.(c)Donnay,J.D.;Harker,D.Am.Mineral.1937,22,446.Figure 2.Overall scheme showing the computational meth-odology adopted when calculating the binding energy betweenthe crystallographic plane and the monolayer surface.Elat)∑k )1n ∑i )1n ′∑j )1n ′V kij (1)V exp )-∆H sub -2RT(2)5888Langmuir,Vol.18,No.15,2002Lee et al.Based on this work,molecular mechanics simulations are performed for hydroxy-and methyl-terminated 4-mer-captobiphenyl along with 4-(4-mercaptophenyl)pyridine for binding studies with different crystallographic planes.In the periodic model,each unit cell contains four biphenyl molecules and the geometric parameters are a )10.02Å,b )42.25Å,c )10.11Åand R )138.3°, )119.9°,γ)95.7°.The length in the y -direction is set to ∼42Åto ensure two-dimensional periodicity.Also,the gold atoms are arranged in a hexagonal lattice along the XY plane with a nearest neighbor atom of 2.88Å,and the biphenyl occupied a ( 3× 3)R30°Au(111)lattice.To simulate different 4′-substituted 4-mercaptobiphenyls,minimiza-tion was carried out by fixing the biphenyl moiety and varying the substituents at the 4′-position.As a result,the simulated models yielded uniform ordered SAMs of 4′-substituted 4-mercaptobiphenyls and 4-(4-mercapto-phenyl)pyridine with identical packing structure and dynamics to those of a hydrogen-terminated monolayer of biphenylmercaptan (Figure 3).However,this is not true experimentally since adsorption of different 4′-substituted 4-mercaptobiphenyls on gold surfaces results in different monolayer structures and thus one of the main assump-tions made in this work.III.5.Binding of Crystal Habit Faces to SAMs of 4-Mercaptobiphenyls on a Au(111)Surface.Based on BFDH and attachment energy morphology prediction,crystal habit faces with the highest morphological im-portance are chosen for binding studies.The crystal surfaces of interest are cleaved and extended to a 3×3unit cell and partially fixed,allowing flexibility in the tail atoms of the amino acid molecules and a more accurate representation of the effects of SAMs of rigid thiols on the crystallographic plane in the calculation of binding energies.The crystal surface is then docked onto a 3×1×3partially fixed nonperiodic monolayer surface,and the conjugate gradient energy minimization technique is performed.Next,the crystal surface is moved to another site on the monolayer surface and the minimization calculations are again performed.This process was repeated 15-20times to obtain the global minimum.For each monolayer surface,numerous calculations are carried out with different crystallographic planes of each amino acid.The binding energy (φBE )of each crystallographic surface with the monolayer surface iswhere φIE is the minimum interaction energy of the monolayer and crystal surfaces,φM is the minimum energy of the monolayer surface in the absence of the crystal face but in the same conformation as it adopts on the surface,and φS is the minimum energy of the crystal surface with no monolayer surface present and in the same molecular conformation in which it docks on the surface.Negative values of binding energies indicate preferential binding of the crystallographic surfaces with SAMs of 4-mercaptobiphenyl.In cases where the binding energy is positive,there is a less likely chance that the particular crystal face will interact and nucleate on the monolayer surface.Thus,using this approach it is possible to screen self-assembled monolayers as possible templates for nucleation and growth of crystals.IV.Results and DiscussionIV.1.Crystallization of Amino Acids on SAMs on Gold.L -Alanine crystallizes from water in the ortho-rhombic space group P 21212(a )6.025Å,b )12.324Å,and c )5.783Å),27and the morphology of the crystals is bipyramidal,dominated by the {020},{120},{110},and {011}growth forms,35as shown in Figure 4.The crystal grown in aqueous solution is indexed by comparing the interfacial angles measured by optical goniometry and theoretical values based on the unit cell of L -alanine.Powder X-ray diffraction patterns (Figure 5)and inter-facial angle measurements reveal that L -alanine crystals nucleating on SAM surfaces crystallize in the ortho-rhombic space group with similar unit cell dimensions.However,functionalized SAMs induce the formation of L -alanine crystals in different crystallographic directions.L -Alanine crystals display the normal bipyramidal habit but are randomly oriented with the different surfaces.In methyl-terminated SAMs,L -alanine selectively nucle-ated on the {020}plane on the surface (Figure 6),whereas in 100%OH SAM surfaces,L -alanine nucleated on an unobserved {200}side face.The crystal exhibits a similar morphology as observed in aqueous solution with an appearance of a {200}face adjacent to the {110}planes (Figure 6).In both cases,the area of each crystal face is substantially larger than those of the other faces on the crystal.The SAM surfaces almost act as an additive or impurity molecule specifically interacting with the crystal face and consequently reducing the relative growth rate and modifying the habit.Crystallization of L -alanine on 4-(4-mercaptophenyl)pyridine surfaces resulted in the {011}face as the plane corresponding to nucleation (Figure 6).The preferential interaction of the monolayer with the {011}face can be attributed to hydrogen bonding at the crystal -monolayer interface.Unlike the other two sur-faces where they can serve as both hydrogen bond donors and acceptors (4′-hydroxy-4-mercaptobiphenyl)or solely as H-bond donors (4′-methyl-4-mercaptobiphenyl),the pyridine electron pair at the surface only serve as hydrogen bond acceptors.The binding of the pyridine surface and the {011}plane can be explained by the amino and methyl groups protruding out perpendicular to the plane (Figure 7)and forming N -H ‚‚‚N and C -H ‚‚‚N hydrogen bonds with the SAM surface,respectively.In contrast,the 100%(34)Ulman,A.;Kang,J.F.;Shnidman,Y.;Liao,S.;Jordan,R.;Choi,G.Y.;Zaccaro,J.;Myerson,A.S.;Rafailovich,M.;Sokolov,J.;Flesicher,C.Rev.Mol.Biotech .2000,74,175.(35)Lehmann,M.S.;Koetzle,T.F.;Hamilton,W.C.J.Am.Chem.Soc .1972.101,2657.Figure 3.Snapshots of (a)4′-methyl-4-mercaptobiphenyl,(b)4′-hydroxy-4-mercaptobiphenyl,(c)4-(4-mercaptophenyl)pyri-dine,and (d)mixed SAMs of 4′-methyl-4-mercaptobiphenyl and 4′-hydroxy-4-mercaptobiphenyl (top view).φBE )φIE -(φM +φS )(3)Crystallization of Amino Acids on Thiol SAMs Langmuir,Vol.18,No.15,20025889CH 3and 100%OH SAM surfaces do not interact as strongly with the hydrogen bond donating plane.In a similar manner,the appearance of an unobserved {200}face of L -alanine grown in aqueous solution on [Au]-S -C 6H 4-C 6H 4-OH can be attributed to hydrogen bonds forming between the two surfaces.The {200}surface contains alternating methyl (CH 3)and carboxylic groups (COO -)that form N -H ‚‚‚O and O ‚‚‚H -O with the hydroxide group of the monolayer film (Figure 7),ideal for binding with surfaces that can serve as both hydrogen bond donors and acceptors.As a result,the preferential interaction leads to the stabilization and appearance of the {200}face.The oriented nucleation of L -alanine crystals on func-tionalized SAMs arises due to the different molecular structures of each crystal face.Similar to the adsorption of additive onto a crystal face,the interaction (or binding)with the monolayer surface depends on the functional group that each crystal face possesses.As a result of preferential interactions with specific crystal faces,in-terfacial molecular recognition directs nucleation and subsequently influences the crystal growth.In addition to L -alanine,SAMs of rigid thiols are employed to investigate the possibility of inhibiting the racemic crystal and inducing the formation of one of its enantiomers.The powder X-ray diffraction pattern (Figure 8)reveals that DL -valine nucleates in the monoclinic form independent of the hydroxyl,methyl,or pyridine surface concentration and that there was no trace of conglomer-ates.DL -Valine crystallizes in the monoclinic space group P 21/c with a unit cell of dimensions a )5.21Å,b )22.10Å,c )5.41Å,and )109.2°.28Although the structural literature reports three separate space group assignments,Leiserowitz and co-workers 36have shown that two of the three space groups (P 21and P 1)are highly improbable for racemic crystals.Interfacial angle measurements and powder X-ray diffraction undertaken in this work agreed much better with the theoretical values and simulated pattern based on the unit cell of the monoclinic space group(36)Wolf,S.G.;Berkovitch-Yellin,Z.;Lahav,M.;Leiserowitz,L.Mol.Cryst.Liq.Cryst .1990,186,3.Figure 4.Crystallographic image (a)and morphology (b)of L -alanine crystal grown from aqueoussolution.Figure 5.X-ray diffractograms of L -alanine nucleated on functionalized SAMs,compared with L -alanine crystallized from aqueous solution (bottom).Indices of the crystallographic planes corresponding to the diffraction intensities of major peaks are indicated at the top.5890Langmuir,Vol.18,No.15,2002Lee et al.。

Mach_数和壁面温度对HyTRV_边界层转捩的影响

第9卷㊀第2期2024年3月气体物理PHYSICSOFGASESVol.9㊀No.2Mar.2024㊀㊀DOI:10.19527/j.cnki.2096 ̄1642.1098Mach数和壁面温度对HyTRV边界层转捩的影响章录兴ꎬ㊀王光学ꎬ㊀杜㊀磊ꎬ㊀余发源ꎬ㊀张怀宝(中山大学航空航天学院ꎬ广东深圳518107)EffectsofMachNumberandWallTemperatureonHyTRVBoundaryLayerTransitionZHANGLuxingꎬ㊀WANGGuangxueꎬ㊀DULeiꎬ㊀YUFayuanꎬ㊀ZHANGHuaibao(SchoolofAeronauticsandAstronauticsꎬSunYat ̄senUniversityꎬShenzhen518107ꎬChina)摘㊀要:典型的高超声速飞行器流场存在着复杂的转捩现象ꎬ其对飞行器的性能有着显著的影响ꎮ针对HyTRV这款接近真实高超声速飞行器的升力体模型ꎬ采用数值模拟方法ꎬ研究Mach数和壁面温度对HyTRV转捩的影响规律ꎮ采用课题组自研软件开展数值计算ꎬMach数的范围为3~8ꎬ壁面温度的范围为150~900Kꎮ首先对γ ̄Re~θt转捩模型和SST湍流模型进行了高超声速修正:将压力梯度系数修正㊁高速横流修正引入到γ ̄Re~θt转捩模型ꎬ并对SST湍流模型闭合系数β∗和β进行可压缩修正ꎻ然后开展了网格无关性验证ꎬ通过与实验结果对比ꎬ确认了修正后的数值方法和软件平台ꎻ最终开展Mach数和壁面温度对HyTRV边界层转捩规律的影响研究ꎮ计算结果表明ꎬ转捩区域主要集中在上表面两侧㊁下表面中心线两侧ꎻ增大来流Mach数ꎬ上下表面转捩起始位置均大幅后移ꎬ湍流区大幅缩小ꎬ但仍会存在ꎬ同时上表面层流区摩阻系数不断增大ꎬ下表面湍流区摩阻系数不断减小ꎻ升高壁面温度ꎬ上下表面转捩起始位置先前移ꎬ然后快速后移ꎬ最终湍流区先后几乎消失ꎮ关键词:转捩ꎻHyTRVꎻ摩阻ꎻMach数ꎻ壁面温度㊀㊀㊀收稿日期:2023 ̄12 ̄13ꎻ修回日期:2024 ̄01 ̄02基金项目:国家重大项目(GJXM92579)ꎻ广东省自然科学基金-面上项目(2023A1515010036)ꎻ中山大学中央高校基本科研业务费专项资金(22qntd0705)第一作者简介:章录兴(1998 )㊀男ꎬ硕士ꎬ主要研究方向为高超声速空气动力学ꎮE ̄mail:184****8082@163.com通信作者简介:张怀宝(1985 )㊀男ꎬ副教授ꎬ主要研究方向为空气动力学ꎮE ̄mail:zhanghb28@mail.sysu.edu.cn中图分类号:V211ꎻV411㊀㊀文献标志码:AAbstract:Thereisacomplextransitionphenomenonintheflowfieldofatypicalhypersonicvehicleꎬwhichhasasignifi ̄cantimpactontheperformanceofthevehicle.TheeffectsofMachnumberandwalltemperatureonthetransitionofHyTRVwerestudiedbynumericalsimulationmethods.Theself ̄developedsoftwareoftheresearchgroupwasusedtocarryoutnu ̄mericalcalculations.TherangeofMachnumberwas3~8ꎬandtherangeofwalltemperaturewas150~900K.Firstlyꎬthehypersoniccorrectionsoftheγ ̄Re~θttransitionmodelandtheSSTturbulencemodelwerecarriedout.Thepressuregradientcoefficientcorrectionandthehigh ̄speedcross ̄flowcorrectionwereintroducedintotheγ ̄Re~θttransitionmodelꎬandthecom ̄pressibilitycorrectionsoftheclosurecoefficientsβ∗andβoftheSSTturbulencemodelwerecarriedout.Thenꎬthegridin ̄dependenceverificationwascarriedoutꎬandthemodifiednumericalmethodandsoftwareplatformwereconfirmedbycom ̄paringwithexperimentalresults.FinallyꎬtheeffectsofMachnumberandwalltemperatureonthetransitionlawoftheHyTRVboundarylayerwerestudied.Theresultsshowthatthetransitionareaismainlyconcentratedonbothsidesoftheuppersurfaceandthecenterlineofthelowersurface.WiththeincreaseoftheincomingMachnumberꎬthestartingpositionoftransitionontheupperandlowersurfacesisgreatlybackwardꎬandtheturbulentzoneisgreatlyreducedꎬbutitstillex ̄ists.Atthesametimeꎬthefrictioncoefficientofthelaminarflowzoneontheuppersurfaceincreasescontinuouslyꎬandthefrictioncoefficientoftheturbulentzoneonthelowersurfacedecreases.Asthewalltemperatureincreasesꎬthestartingposi ̄tionoftransitionontheupperandlowersurfacesshiftsforwardꎬthenrapidlyshiftsbackwardꎬandfinallytheturbulentzonealmostdisappears.气体物理2024年㊀第9卷Keywords:transitionꎻHyTRVꎻfrictionꎻMachnumberꎻwalltemperature引㊀言高超声速飞行器具有突防能力强㊁打击范围广㊁响应迅速等显著优势ꎬ正逐渐成为各国空天竞争的热点[1]ꎮ高超声速飞行器边界层转捩是该类飞行器气动设计中的重要问题[2]ꎮ在边界层转捩过程中ꎬ流态由层流转变为湍流ꎬ飞行器的表面摩阻急剧增大到层流时的3~5倍ꎬ严重影响飞行器的气动性能与热防护系统ꎬ转捩还会导致飞行器壁面烧蚀㊁颤振加剧㊁飞行姿态控制难度大等一系列问题ꎬ对飞行器的飞行安全构成严重的威胁[3 ̄5]ꎬ开展高超声速飞行器边界层转捩研究具有十分重要的意义ꎮ影响边界层转捩的因素很多ꎬ例如ꎬMach数㊁Reynolds数㊁湍流强度㊁表面传导热等ꎮ在高超声速流动条件下ꎬ强激波㊁强逆压梯度㊁熵层等高超声速现象及其相互作用ꎬ会使得转捩流动的预测和研究难度进一步增大[6]ꎮ目前高超声速飞行器转捩数值模拟方法主要有直接数值模拟(DNS)㊁大涡模拟(LES)和基于Reynolds平均Navier ̄Stokes(RANS)的转捩模型方法ꎬ由于前两种计算量巨大ꎬ难以推广到工程应用ꎬ基于Reynolds平均Navier ̄Stokes的转捩模型在工程实践中应用最为广泛ꎬ其中γ ̄Re~θt转捩模型基于局部变量ꎬ与现代CFD方法良好兼容ꎬ目前已经有多项研究尝试从一般性的流动问题拓展到高超声速流动转捩模拟[6 ̄9]ꎮ目前高超声速流动转捩的研究对象主要是结构相对简单的构型ꎮMcDaniel等[10]研究了扩口直锥在高超声速流动条件下的转捩现象ꎮPapp等[11]研究了圆锥在高超声速流动条件下的转捩特性ꎮ美国和澳大利亚组织联合实施的HIFiRE计划[12]ꎬ研究了圆锥形状的HIFiRE1和椭圆锥形的HIFiRE5的转捩问题ꎮ杨云军等[13]采用数值模拟方法ꎬ分析了椭圆锥的转捩影响机制ꎬ并研究了Reynolds数对转捩特性的影响规律ꎮ另外ꎬ袁先旭等[14]于2015年成功实施了圆锥体MF ̄1航天模型飞行试验ꎮ以上对高超声速流动的转捩研究ꎬ都取得了比较理想的结果ꎬ然而所采用的模型都是圆锥㊁椭圆锥等简单几何外形ꎬ这与真实高超声速飞行器有较大差异ꎬ较难反映真实的转捩特性ꎮ为了有效促进对真实高超声速飞行器的转捩问题研究ꎬ中国空气动力研究与发展中心提出并设计了一款接近真实飞行器的升力体模型ꎬ即高超声速转捩研究飞行器(hypersonictransitionresearchvehicleꎬHyTRV)[15]ꎬ模型详细的参数见参考文献[16]ꎮHyTRV外形如图1所示ꎬ其整体外形较为复杂ꎬ不同区域发生转捩的情况也不尽相同ꎮ对HyTRV的转捩问题研究能够显著提高对真实高超声速飞行器转捩特性的认识水平ꎮLiu等[17]采用理论分析㊁数值模拟和风洞实验3种方法对HyTRV的转捩特性进行了研究ꎻ陈坚强等[15]分析了HyTRV的边界层失稳特征ꎻChen等[18]对HyTRV进行了多维线性稳定性分析ꎻQi等[19]在来流Mach数6㊁攻角0ʎ的条件下对HyTRV进行了直接数值模拟ꎻ万兵兵等[20]结合风洞实验与飞行试验ꎬ利用eN方法预测了HyTRV升力体横流区的转捩阵面形状ꎮ目前ꎬ相关研究主要集中在HyTRV的稳定性特征及转捩预测两个方面ꎬ而对若干关键参数ꎬ特别是Mach数和壁面温度对转捩的影响研究还比较少ꎮ(a)Frontview(b)Sideview㊀㊀㊀图1㊀HyTRV外形Fig.1㊀ShapeofHyTRV基于此ꎬ本文采用数值模拟方法ꎬ应用课题组自研软件开展Mach数和壁面温度对HyTRV转捩流动的影响规律研究ꎮ1㊀数值方法1.1㊀控制方程和数值方法控制方程为三维可压缩RANS方程ꎬ采用结构网格技术和有限体积方法ꎬ变量插值方法采用2阶MUSCL格式ꎬ通量计算采用低耗散的通量向量差分Roe格式ꎬ黏性项离散采用中心格式ꎬ时间推进方法采用LU ̄SGS格式ꎮ壁面采用等温㊁无滑移壁面条件ꎬ入口采用Riemann远场边界条件ꎬ出口采用零梯度外推边界条件ꎮ1.2㊀γ ̄Re~θt转捩模型γ ̄Re~θt转捩模型是Menter等[21ꎬ22]于2004年提01第2期章录兴ꎬ等:Mach数和壁面温度对HyTRV边界层转捩的影响出的一种基于拟合公式的间歇因子转捩模型ꎬ在2009年公布了完整的拟合公式及相关参数[23]ꎮ许多学者也开发了相应的程序ꎬ并进行了大量的算例验证[24 ̄28]ꎬ证明了该模型具有较好的转捩预测能力ꎬ预测精度较高ꎻ通过合适的标定ꎬγ ̄Re~θt转捩模型可以适用于多种情况下的转捩模拟ꎮ该模型构建了关于间歇因子γ的输运方程和关于转捩动量厚度Reynolds数Re~θt的输运方程ꎮ具体来说ꎬγ表示该位置是湍流流动的概率ꎬ取值范围为0<γ<1ꎮ关于γ的控制方程为Ə(ργ)Ət+Ə(ρujγ)Əxj=Pγ-Eγ+ƏƏxjμ+μtσfæèçöø÷ƏγƏxjéëêêùûúú其中ꎬPγ为生成项ꎬEγ为破坏项ꎮ关于Re~θt的输运方程为Ə(ρRe~θt)Ət+Ə(ρujRe~θt)Əxj=Pθt+ƏƏxjσθt(μ+μt)ƏRe~θtƏxjéëêêùûúú其中ꎬPθt为源项ꎬ其作用是使边界层外部的Re~θt等于Reθtꎬ定义式为Pθt=cθtρt(Reθt-Re~θt)(1.0-Fθt)Reθt采用以下经验公式Reθt=1173.51-589 428Tu+0.2196Tu2æèçöø÷F(λθ)ꎬTuɤ0.3Reθt=331.50(Tu-0.5658)-0.671F(λθ)ꎬTu>0.3ìîíïïïïF(λθ)=1+(12.986λθ+123.66λ2θ+405.689λ3θ)e-(Tu1.5)1.5ꎬ㊀λθɤ0F(λθ)=1+0.275(1-e-35.0λθ)e-(Tu0.5)ꎬλθ>0ìîíïïïï在实际计算中ꎬ通过γ ̄Re~θt转捩模型获得间歇因子ꎬ再通过间歇因子来控制SSTk ̄ω湍流模型中湍动能的生成ꎮγ ̄Re~θt转捩模型与SSTk ̄ω湍流模型耦合为Ə(ρk)Ət+Ə(ρujk)Əxj=γeffτijƏuiƏxj-min(max(γeffꎬ0.1)ꎬ1.0)ρβ∗kω+ƏƏxjμ+μtσkæèçöø÷ƏkƏxjéëêêùûúúƏ(ρω)Ət+Ə(ρujω)Əxj=γvtτijƏuiƏxj-βρω2+ƏƏxj(μ+σωμt)ƏωƏxjéëêêùûúú+2ρ(1-F1)σω21ωƏkƏxjƏωƏxj模型中具体参数定义见文献[23]ꎮ1.3㊀高超声速修正原始SST湍流模型及γ ̄Re~θt转捩模型都是基于不可压缩流动发展的ꎬ为了更好地预测高超声速流动转捩ꎬ本节引入了3种重要的高超声速修正方法ꎮ1.3.1㊀压力梯度修正压力梯度对边界层转捩的影响较大ꎬ在高Mach数情况下ꎬ边界层厚度较大ꎬ进而影响压力梯度的大小ꎬ因此在模拟高超声速流动时应该考虑Mach数对压力梯度的影响ꎮ本文采用张毅峰等[29]提出的压力梯度修正方法ꎬ具体修正形式如下λᶄθ=λθ1+γᶄ-12Maeæèçöø÷其中ꎬMae为边界层外缘Mach数ꎬγᶄ为比热比ꎮ1.3.2㊀高速横流修正在原始γ ̄Re~θt转捩模型中ꎬ没有考虑横流不稳定性对转捩的影响ꎬ对于横流模态主导的转捩ꎬ原始转捩模型计算的结果并不理想ꎮLangtry等[30]在2015年对γ ̄Re~θt转捩模型进行了低速横流修正ꎬ向星皓等[9]在Langtry低速横流修正的基础上ꎬ对高超声速椭圆锥转捩DNS数据进行了拓展ꎬ提出了高速横流转捩判据ꎬ本文直接采用向星皓提出的高速横流转捩方法ꎮLangtry将横流强度引入转捩发生动量厚度Reynolds数输运方程中Ə(ρRe~θt)Ət+Ə(ρujRe~θt)Əxj=Pθt+DSCF+ƏƏxjσθt(μ+μt)ƏRe~θtƏxjéëêêùûúú式中ꎬDSCF为横流源项ꎬLangtry低速横流修正为DSCF=cθtρtccrossflowmin(ReSCF-Re~θtꎬ0.0)Fθt2其中ꎬReSCF为低速横流判据ReSCF=θtρUlocal0.82æèçöø÷μ=-35.088lnhθtæèçöø÷+319.51+f(+ΔHcrossflow)-f(-ΔHcrossflow)其中ꎬh为壁面粗糙度高度ꎬθt为动量厚度ꎬ11气体物理2024年㊀第9卷ΔHcrossflow是横流强度抬升项ꎮ向星皓提出的高速横流转捩判据ꎬ其中高速横流源项DSCF ̄H为DSCF ̄H=cCFρmin(ReSCF ̄H-Re~θtꎬ0)FθtReSCF ̄H=CCF ̄1lnhlμ+CCF ̄2+(Hcrossflow)其中ꎬCCF ̄1=-9.618ꎬCCF ̄2=128.33ꎻlμ为粗糙度参考高度ꎬlμ=1μmꎻf(Hcrossflow)为抬升函数f(Hcrossflow)=60000.1066-ΔHcrossflow+50000(0.1066-ΔHcrossflow)2其中ꎬΔHcrossflow与Langtry低速横流修正中保持一致ꎮ1.3.3㊀SST可压缩修正高超声速流动具有强可压缩性ꎬ所以在进行高超声速计算时ꎬ应该对湍流模型进行可压缩修正ꎮSarkar[31]提出了膨胀耗散修正ꎬ对SST湍流模型中的闭合系数β∗ꎬβ进行了可压缩修正ꎬWilcox[32]在Sarkar修正的基础上考虑了可压缩生成项产生时的延迟效应ꎬ使得可压缩修正在湍流Mach数较小的近壁面关闭ꎬ在湍流Mach数较大的自由剪切层打开ꎬ本文采用Wilcox提出的可压缩性修正β∗=β∗0[1+ξ∗F(Mat)]β=β0-β∗0ξ∗F(Mat)其中ꎬβ0ꎬβ∗均为原始模型中的系数ꎬξ∗=1.5ꎮF(Mat)=[Mat-Mat0]H(Mat-Mat0)Mat0=1/4ꎬH(x)=0ꎬxɤ01ꎬx>0{其中ꎬMat=2k/a为湍流Mach数ꎬa为当地声速ꎮ2㊀网格无关性验证及数值方法确认2.1㊀网格无关性验证计算采用3套网格ꎬ考虑到HyTRV的几何对称性ꎬ生成3套半模网格ꎬ第1层网格高度为1ˑ10-6mꎬ确保y+<1ꎬ流向ˑ法向ˑ周向的网格数分别为:网格1是301ˑ201ˑ201ꎬ网格2是301ˑ301ˑ201ꎬ网格3是401ˑ381ˑ281ꎮ全模下表面如图2所示ꎬ选取y/L=0中心线和x/L=0.5处ꎬ对比3套网格的表面摩阻系数ꎬ计算结果如图3所示ꎮ采用网格1时ꎬ表面摩阻系数分布与另外两个结果存在明显差异ꎻ而采用网格2和网格3时ꎬ表面摩阻系数曲线基本重合ꎬ表明在流向㊁法向和周向均满足网格无关性ꎬ后续数值计算采用网格2ꎮ图2㊀截取位置示意图Fig.2㊀Schematicdiagramoftheinterceptionlocation(a)Surfacefrictionaty/L=0(b)Surfacefrictionatx/L=0.5图3㊀采用3套网格计算得到的摩阻对比Fig.3㊀Comparisonofthefrictiondragcalculatedusingthreesetsofgrids2.2㊀数值方法和自研软件的确认采用修正后的转捩模型对HyTRV开展计算ꎬ计算工况为Ma=6ꎬ来流温度Tɕ=97Kꎬ单位21第2期章录兴ꎬ等:Mach数和壁面温度对HyTRV边界层转捩的影响Reynolds数为Re=1.1ˑ107/mꎬ攻角α=0ʎꎬ来流湍流度FSTI=0.8%ꎬ壁面温度T=300Kꎮ为方便对比分析ꎬ计算结果与参考结果均采用上下对称形式布置ꎬ例如ꎬ图4是模型下表面计算结果与实验结果对比:对于下表面两侧转捩的起始位置ꎬ高超声速修正前的转捩位置在x=0.68m附近ꎬ高超声速修正后的计算结果与实验结果吻合良好ꎬ均在x=0.60m附近ꎬ并且湍流边界层区域形状基本一致ꎬ说明修正后的转捩模型能够较好地预测HyTRV转捩的位置ꎮ(a)Calculationofthefrictiondistribution(beforehypersoniccorrection)(b)Calculationofthefrictiondistribution(afterhypersoniccorrection)(c)Experimentalresultsoftheheatfluxdistribution[17]图4㊀下表面计算结果和实验结果对比Fig.4㊀Comparisonofthecalculatedandexperimentalresultsonthelowersurface3㊀HyTRV转捩的基本流动特性计算工况采用Ma=6ꎬ攻角α=0ʎꎬ来流湍流度FSTI=0.6%ꎬ分析HyTRV转捩的基本流动特性ꎮ从图5可以看出ꎬ模型两侧和顶端均出现高压区ꎬ高压区之间为低压区ꎬ横截面上存在周向压力梯度ꎬ流动从高压区向低压区汇集ꎬ从而在下表面中心线附近和上表面两侧腰部区域均形成流向涡结构(见图6)ꎬ沿流动方向ꎬ高压区域逐渐扩大ꎬ流向涡结构的影响范围也越大ꎮ在流向涡结构的边缘位置ꎬ壁面附近的低速流体被抬升到外壁面区域ꎬ外壁面区域的高速流体又被带入到近壁面区域ꎬ进而导致流向涡结构边缘处壁面的摩阻显著增加ꎬ最终诱发转捩ꎬ这些流动特征与文献[15]的结果一致ꎮ图7显示了上下表面摩阻的分布情况ꎬ其中上表面两侧区域在x/L=0.80附近ꎬ摩阻显著增加ꎬ出现明显的转捩现象ꎬ转捩区域分布在两侧边缘位置ꎻ而下表面两侧区域在x/L=0.75附近ꎬ也出现明显的转捩ꎬ转捩区域相对集中在中心线两侧ꎮ图5㊀不同截面位置处的压力云图Fig.5㊀Pressurecontoursatdifferentcross ̄sectionlocations图6㊀不同截面位置处的流向速度云图Fig.6㊀Streamwisevelocitycontoursatdifferentcross ̄sectionlocations31气体物理2024年㊀第9卷(a)Uppersurface㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀(b)Lowersurface图7㊀上下表面摩阻分布云图Fig.7㊀Frictioncoefficientcontoursontheupperandlowersurfaces4㊀不同Mach数对HyTRV转捩的影响保持来流湍流度FSTI=0.6%不变ꎬMach数变化范围为3~8ꎮ图8是不同Mach数条件下HyTRV上下表面的摩阻分布云图ꎬ从图中可知ꎬ随着Mach数的增加ꎬ上下表面的湍流区域均逐渐减少ꎬ其中上表面两侧转捩起始位置由x/L=0.56附近后移至x/L=0.92附近ꎬ下表面两侧转捩起始位置由x/L=0.48附近后移至x/L=0.99附近ꎬ上下表面两侧转捩起始位置均大幅后移ꎬ说明Mach数对HyTRV转捩的影响很大ꎮuppersurface㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀lowersurface(a)Ma=3uppersurface㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀lowersurface(b)Ma=4uppersurface㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀lowersurface(c)Ma=541第2期章录兴ꎬ等:Mach数和壁面温度对HyTRV边界层转捩的影响uppersurface㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀lowersurface(d)Ma=6uppersurface㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀lowersurface(e)Ma=7uppersurface㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀lowersurface(f)Ma=8图8㊀不同Mach数条件下摩阻系数分布云图Fig.8㊀FrictioncoefficientcontoursatdifferentMachnumbers上表面选取图7中z/L=0.12的位置ꎬ下表面选取z/L=0.10的位置进行分析ꎮ从图9中可以分析出ꎬ随着Mach数的增加ꎬ上表面转捩起始位置不断后移ꎬ当Mach数增加到7时ꎬ由于湍流区的缩小ꎬ此处位置不再发生转捩ꎬ此外ꎬMach数越高层流区摩阻系数越大ꎻ下表面转捩起始位置也不断后移ꎬ当Mach数增加到8时ꎬ此处位置不再发生转捩ꎬ此外ꎬMach数越高ꎬ湍流区的摩阻系数越小ꎬ这些结论与关于来流Mach数对转捩位置影响的普遍研究结论一致ꎮ(a)Uppersurface㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀(b)Lowersurface图9㊀不同位置摩阻系数随Mach数的变化Fig.9㊀VariationoffrictioncoefficientwithMachnumberatdifferentlocations51气体物理2024年㊀第9卷5㊀不同壁面温度对HyTRV转捩的影响保持来流湍流度FSTI=0.6%及Ma=6不变ꎬ壁面温度的变化范围为150~900Kꎮ图10是不同壁面温度条件下HyTRV上下表面的摩阻分布云图ꎬ可以看出随着壁面温度的增加ꎬ上表面两侧湍流区域先是缓慢扩大ꎬ在壁面温度为500K时湍流区域快速缩小ꎬ增加到900K时ꎬ已无明显湍流区域ꎻ下表面两侧湍流区域先是无明显变化ꎬ同样当壁面温度升高到500K时ꎬ湍流区域快速缩小ꎬ当壁面温度升高到700K时ꎬ两侧已经无明显的湍流区域ꎬ相比上表面两侧湍流区域ꎬ下表面湍流区域消失得更早ꎮ由此可以得出壁面温度对转捩的产生有较大的影响ꎬ壁面温度增加到一定程度将导致HyTRV没有明显的转捩现象ꎮuppersurface㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀lowersurface(a)T=150Kuppersurface㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀lowersurface(b)T=200Kuppersurface㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀lowersurface(c)T=300Kuppersurface㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀lowersurface(d)T=500K61第2期章录兴ꎬ等:Mach数和壁面温度对HyTRV边界层转捩的影响uppersurface㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀lowersurface(e)T=700Kuppersurface㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀lowersurface(f)T=900K图10㊀不同壁面温度条件下摩阻系数分布云图Fig.10㊀Frictioncoefficientcontoursatdifferentwalltemperatureconditions上表面选取z/L=0.125的位置ꎬ下表面选取z/L=0.100的位置进行分析ꎮ从图11中可以分析出ꎬ随着壁面温度的增加ꎬ上表面转捩起始位置先前移ꎬ当壁面温度增加到500K时ꎬ转捩起始位置后移ꎬ转捩区长度逐渐增加ꎬ层流区域的摩阻系数逐渐增加ꎬ当壁面温度增加到700K时ꎬ该位置已不再出现转捩ꎻ下表面转捩起始位置先小幅后移ꎬ当壁面温度增加到300K时ꎬ转捩起始位置开始后移ꎬ当壁面温度增加到700K时ꎬ由于湍流区域的减小ꎬ该位置不再发生转捩ꎮ(a)Uppersurface㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀(b)Lowersurface图11㊀不同位置摩阻系数随壁面温度的变化Fig.11㊀Variationoffrictioncoefficientwithwalltemperatureatdifferentlocations为进一步分析壁面温度的影响ꎬ本文分别在上下表面湍流区选取一点(0.9ꎬ0.029ꎬ0.14)ꎬ(0.97ꎬ-0.34ꎬ0.12)ꎬ分析边界层湍动能剖面ꎬ结果如图12所示ꎮ从图中可以看到ꎬ随着壁面温度升高ꎬ边界层厚度先略微变厚ꎬ再变薄ꎬ当壁面温度升高到700K时ꎬ边界层厚度迅速降低ꎮ这些结果与转捩位置先前移再后移的结论相符合ꎬ因为边界层厚度会影响不稳定波的时间和空间尺度ꎬ边界层厚度低时ꎬ不稳定波增长速度变慢ꎬ延迟转捩发生ꎮ需要指出的是ꎬ仅采用当前使用的方法ꎬ无法从更深层71气体物理2024年㊀第9卷次揭示转捩反转的流动机理ꎬ而须另外借助稳定性分析方法ꎬ例如ꎬ使用eN方法开展基于模态的稳定性研究ꎮ文献[33]采用该手段研究了大掠角平板钝三角翼随壁温比变化出现转捩反转的内在机理:壁温比升高促进横流模态和第1模态扰动增长ꎬ抑制第2模态发展ꎬ在第1㊁2模态联合作用影响下ꎬ出现转捩反转现象ꎮ我们将在后续开展进一步研究ꎮ(a)Uppersurface(b)Lowersurface图12㊀不同位置湍动能剖面随壁面温度的变化Fig.12㊀Variationofturbulentkineticenergywithwalltemperatureatdifferentlocations6㊀结论针对HyTRV转捩问题ꎬ在Mach数Ma=3~8ꎬ壁面温度T=150~900K的条件下ꎬ基于课题组自研软件ꎬ对γ ̄Re~θt转捩模型和SST湍流模型进行了高超声速修正ꎬ研究了Mach数和壁面温度对HyTRV转捩的影响ꎬ得出以下结论:1)经过高超声速修正后的γ ̄Re~θt转捩模型和SST湍流模型能够较为准确地预测HyTRV转捩位置ꎬ并且湍流边界层区域形状与实验结果基本一致ꎻHyTRV存在多个不同的转捩区域ꎬ上表面两侧转捩区域分布在两侧边缘位置ꎬ下表面两侧转捩区域分布在中心线两侧ꎮ2)Mach数的增加会导致上下表面转捩起始位置均大幅后移ꎬ湍流区大幅缩小ꎬ但当Mach数增加到8时ꎬ湍流区仍然存在ꎬ并没有消失ꎻ上表面层流区摩阻不断增加ꎬ下表面湍流区摩阻不断减小ꎮ3)壁面温度的增加会导致上下表面转捩起始位置先前移ꎬ再后移ꎬ这与边界层厚度变化规律一致ꎬ当壁面温度增加到700K时ꎬ下表面湍流区已经基本消失ꎬ当壁面温度增加到900K时ꎬ上表面湍流区也基本消失ꎻ上表面在层流区域的摩阻系数逐渐增大ꎬ在湍流区的摩阻系数逐渐减小ꎮ致谢㊀感谢中国空气动力研究与发展中心和空天飞行空气动力科学与技术全国重点实验室提供的HyTRV模型数据和实验数据ꎮ参考文献(References)[1]㊀OberingIIIHꎬHeinrichsRL.Missiledefenseforgreatpowerconflict:outmaneuveringtheChinathreat[J].Stra ̄tegicStudiesQuarterlyꎬ2019ꎬ3(4):37 ̄56. [2]ChengCꎬWuJHꎬZhangYLꎬetal.Aerodynamicsanddynamicstabilityofmicro ̄air ̄vehiclewithfourflappingwingsinhoveringflight[J].AdvancesinAerodynamicsꎬ2020ꎬ2(3):5.[3]BertinJJꎬCummingsRM.Fiftyyearsofhypersonics:whereweᶄvebeenꎬwhereweᶄregoing[J].ProgressinAerospaceSciencesꎬ2003ꎬ39(6/7):511 ̄536. [4]陈坚强ꎬ涂国华ꎬ张毅锋ꎬ等.高超声速边界层转捩研究现状与发展趋势[J].空气动力学学报ꎬ2017ꎬ35(3):311 ̄337.ChenJQꎬTuGHꎬZhangYFꎬetal.Hypersnonicboundarylayertransition:whatweknowꎬwhereshallwego[J].ActaAerodynamicaSinicaꎬ2017ꎬ35(3):311 ̄337(inChinese).[5]段毅ꎬ姚世勇ꎬ李思怡ꎬ等.高超声速边界层转捩的若干问题及工程应用研究进展综述[J].空气动力学学报ꎬ2020ꎬ38(2):391 ̄403.DuanYꎬYaoSYꎬLiSYꎬetal.Reviewofprogressinsomeissuesandengineeringapplicationofhypersonicboundarylayertransition[J].ActaAerodynamicaSinicaꎬ2020ꎬ38(2):391 ̄403(inChinese).[6]ZhangYFꎬZhangYRꎬChenJQꎬetal.Numericalsi ̄81第2期章录兴ꎬ等:Mach数和壁面温度对HyTRV边界层转捩的影响mulationsofhypersonicboundarylayertransitionbasedontheflowsolverchant2.0[R].AIAA2017 ̄2409ꎬ2017. [7]KrauseMꎬBehrMꎬBallmannJ.Modelingoftransitioneffectsinhypersonicintakeflowsusingacorrelation ̄basedintermittencymodel[R].AIAA2008 ̄2598ꎬ2008. [8]YiMRꎬZhaoHYꎬLeJL.Hypersonicnaturalandforcedtransitionsimulationbycorrelation ̄basedintermit ̄tency[R].AIAA2017 ̄2337ꎬ2017.[9]向星皓ꎬ张毅锋ꎬ袁先旭ꎬ等.C ̄γ ̄Reθ高超声速三维边界层转捩预测模型[J].航空学报ꎬ2021ꎬ42(9):625711.XiangXHꎬZhangYFꎬYuanXXꎬetal.C ̄γ ̄Reθmodelforhypersonicthree ̄dimensionalboundarylayertransitionprediction[J].ActaAeronauticaetAstronauticaSinicaꎬ2021ꎬ42(9):625711(inChinese).[10]McDanielRDꎬNanceRPꎬHassanHA.Transitiononsetpredictionforhigh ̄speedflow[J].JournalofSpacecraftandRocketsꎬ2000ꎬ37(3):304 ̄309.[11]PappJLꎬDashSM.Rapidengineeringapproachtomodelinghypersoniclaminar ̄to ̄turbulenttransitionalflows[J].JournalofSpacecraftandRocketsꎬ2005ꎬ42(3):467 ̄475.[12]JulianoTJꎬSchneiderSP.InstabilityandtransitionontheHIFiRE ̄5inaMach ̄6quiettunnel[R].AIAA2010 ̄5004ꎬ2010.[13]杨云军ꎬ马汉东ꎬ周伟江.高超声速流动转捩的数值研究[J].宇航学报ꎬ2006ꎬ27(1):85 ̄88.YangYJꎬMaHDꎬZhouWJ.Numericalresearchonsupersonicflowtransition[J].JournalofAstronauticsꎬ2006ꎬ27(1):85 ̄88(inChinese).[14]袁先旭ꎬ何琨ꎬ陈坚强ꎬ等.MF ̄1模型飞行试验转捩结果初步分析[J].空气动力学学报ꎬ2018ꎬ36(2):286 ̄293.YuanXXꎬHeKꎬChenJQꎬetal.PreliminarytransitionresearchanalysisofMF ̄1[J].ActaAerodynamicaSinicaꎬ2018ꎬ36(2):286 ̄293(inChinese).[15]陈坚强ꎬ涂国华ꎬ万兵兵ꎬ等.HyTRV流场特征与边界层稳定性特征分析[J].航空学报ꎬ2021ꎬ42(6):124317.ChenJQꎬTuGHꎬWanBBꎬetal.Characteristicsofflowfieldandboundary ̄layerstabilityofHyTRV[J].ActaAeronauticaetAstronauticaSinicaꎬ2021ꎬ42(6):124317(inChinese).[16]陈坚强ꎬ刘深深ꎬ刘智勇ꎬ等.用于高超声速边界层转捩研究的标模气动布局及设计方法.中国:109969374B[P].2021 ̄05 ̄18.ChenJQꎬLiuSSꎬLiuZYꎬetal.Standardmodelaero ̄dynamiclayoutanddesignmethodforhypersonicboundarylayertransitionresearch.CNꎬ109969374B[P].2021 ̄05 ̄18(inChinese).[17]LiuSSꎬYuanXXꎬLiuZYꎬetal.Designandtransitioncharacteristicsofastandardmodelforhypersonicboundarylayertransitionresearch[J].ActaMechanicaSinicaꎬ2021ꎬ37(11):1637 ̄1647.[18]ChenXꎬDongSWꎬTuGHꎬetal.Boundarylayertran ̄sitionandlinearmodalinstabilitiesofhypersonicflowoveraliftingbody[J].JournalofFluidMechanicsꎬ2022ꎬ938(408):A8.[19]QiHꎬLiXLꎬYuCPꎬetal.Directnumericalsimulationofhypersonicboundarylayertransitionoveralifting ̄bodymodelHyTRV[J].AdvancesinAerodynamicsꎬ2021ꎬ3(1):31.[20]万兵兵ꎬ陈曦ꎬ陈坚强ꎬ等.三维边界层转捩预测HyTEN软件在高超声速典型标模中的应用[J].空天技术ꎬ2023(1):150 ̄158.WanBBꎬChenXꎬChenJQꎬetal.ApplicationsofHyTENsoftwareforpredictingthree ̄dimensionalboundary ̄layertransitionintypicalhypersonicmodels[J].AerospaceTechnologyꎬ2023(1):150 ̄158(inChinese). [21]MenterFRꎬLangtryRBꎬLikkiSRꎬetal.Acorrelation ̄basedtransitionmodelusinglocalvariables PartⅠ:modelformulation[J].JournalofTurbomachineryꎬ2006ꎬ128(3):413 ̄422.[22]LangtryRBꎬMenterFRꎬLikkiSRꎬetal.Acorrelation ̄basedtransitionmodelusinglocalvariables PartⅡ:testcasesandindustrialapplications[J].JournalofTur ̄bomachineryꎬ2006ꎬ128(3):423 ̄434.[23]LangtryRBꎬMenterFR.Correlation ̄basedtransitionmodelingforunstructuredparallelizedcomputationalfluiddynamicscodes[J].AIAAJournalꎬ2009ꎬ47(12):2894 ̄2906.[24]孟德虹ꎬ张玉伦ꎬ王光学ꎬ等.γ ̄Reθ转捩模型在二维低速问题中的应用[J].航空学报ꎬ2011ꎬ32(5):792 ̄801.MengDHꎬZhangYLꎬWangGXꎬetal.Applicationofγ ̄Reθtransitionmodeltotwo ̄dimensionallowspeedflows[J].ActaAeronauticaetAstronauticaSinicaꎬ2011ꎬ32(5):792 ̄801(inChinese).[25]牟斌ꎬ江雄ꎬ肖中云ꎬ等.γ ̄Reθ转捩模型的标定与应用[J].空气动力学学报ꎬ2013ꎬ31(1):103 ̄109.MouBꎬJiangXꎬXiaoZYꎬetal.Implementationandcaliberationofγ ̄Reθtransitionmodel[J].ActaAerody ̄namicaSinicaꎬ2013ꎬ31(1):103 ̄109(inChinese). [26]郭隽ꎬ刘丽平ꎬ徐晶磊ꎬ等.γ ̄Re~θt转捩模型在跨声速涡轮叶栅中的应用[J].推进技术ꎬ2018ꎬ39(9):1994 ̄2001.91气体物理2024年㊀第9卷GuoJꎬLiuLPꎬXuJLꎬetal.Applicationofγ ̄Re~θttran ̄sitionmodelintransonicturbinecascades[J].JournalofPropulsionTechnologyꎬ2018ꎬ39(9):1994 ̄2001(inChinese).[27]郑赟ꎬ李虹杨ꎬ刘大响.γ ̄Reθ转捩模型在高超声速下的应用及分析[J].推进技术ꎬ2014ꎬ35(3):296 ̄304.ZhengYꎬLiHYꎬLiuDX.Applicationandanalysisofγ ̄Reθtransitionmodelinhypersonicflow[J].JournalofPropulsionTechnologyꎬ2014ꎬ35(3):296 ̄304(inChi ̄nese).[28]孔维萱ꎬ阎超ꎬ赵瑞.γ ̄Reθ模式应用于高速边界层转捩的研究[J].空气动力学学报ꎬ2013ꎬ31(1):120 ̄126.KongWXꎬYanCꎬZhaoR.γ ̄Reθmodelresearchforhigh ̄speedboundarylayertransition[J].ActaAerody ̄namicaSinicaꎬ2013ꎬ31(1):120 ̄126(inChinese). [29]张毅锋ꎬ何琨ꎬ张益荣ꎬ等.Menter转捩模型在高超声速流动模拟中的改进及验证[J].宇航学报ꎬ2016ꎬ37(4):397 ̄402.ZhangYFꎬHeKꎬZhangYRꎬetal.ImprovementandvalidationofMenterᶄstransitionmodelforhypersonicflowsimulation[J].JournalofAstronauticsꎬ2016ꎬ37(4):397 ̄402(inChinese).[30]LangtryRBꎬSenguptaKꎬYehDTꎬetal.Extendingtheγ ̄Reθtcorrelationbasedtransitionmodelforcrossfloweffects(Invited)[R].AIAA2015 ̄2474ꎬ2015. [31]SarkarS.Thepressure ̄dilatationcorrelationincompressi ̄bleflows[J].PhysicsofFluidsAꎬ1992ꎬ4(12):2674 ̄2682.[32]WilcoxDC.Dilatation ̄dissipationcorrectionsforadvancedturbulencemodels[J].AIAAJournalꎬ1992ꎬ30(11):2639 ̄2646.[33]马祎蕾ꎬ余平ꎬ姚世勇.壁温对钝三角翼边界层稳定性及转捩影响[J].空气动力学学报ꎬ2020ꎬ38(6):1017 ̄1026.MaYLꎬYuPꎬYaoSY.Effectofwalltemperatureonstabilityandtransitionofhypersonicboundarylayeronabluntdeltawing[J].ActaAerodynamicaSinicaꎬ2020ꎬ38(6):1017 ̄1026(inChinese).02。

稳定的高功率激光系统在高级引力波探测器中的应用