Printed in Great Britain The Company of Biologists Limited 1991 Drosophila gastrulation an

Transgenic Mice(转基因小鼠) - 显微注射用DNA 载体构建

Construct Transgene Vectors for Pronuclear InjectionDanielChapterHistoryApllications & Efficiency FactorsDesign Transgene VectorsTransgene vectorsHistory-The First Transgenic MiceTransgenicHistory-The Super MouseHistory-The transgenic LivestockPronuclear InjectionPronuclear microinjection isconceptually straightforward: inject a small volume of fluid containing your gene of interest into a pronucleus of a zygote, and then transfer zygotes to a foster mother.Applications of Tansgene Technology Based on Pronuclear Injectionthe first group encompasses transgenicsused for the investigation of geneexpression patterns and the function ofregulatory sequences;In this group gene regulatory sequencesare used in combination with a reportergene (e.g., LacZ) to determine expressionpatterns.Applications of tansgene vectors In this case gene coding sequences are expressed under the control of either tissue specific regulatory sequences orubiquitously active promoters.The second group comprises transgenics designed to gain more insight into gene function.New applicationsLoss of Funtion Gain of FuntionParameter That Influence The Efficiency of Producing Transgenic Animals by Pronuclear MicroinjectionDNA concentrationInjection bufferVisualizing pronucleiTiming of injectionSize of DNACopy numberPosition Effect insulatorWell designed vectors can improveexpression of transgene!Design of a Transgene-Containing VectorSelection of Promoters and Additional Regulatory Sequences for Tissue-Specific ExpressionFigure 5 Tissue-specific expression ofmGSTK1 and rGSTK1Biochem. J. (2003) 373 (559–569)(Printed in Great Britain)Nevertheless, the suitability of the sequences identified has to be proven in vivo. Thesimplest approach uses combinations of promoter/enhancer deletions with the LacZ orfluorescent protein reporter genes (luciferase).Selection of Promoters and Additional Regulatory Sequences for Ubiquitous ExpressionInsulatorschicken β-globin 5′ hypersensitive site 4Selection and Design of the Coding SequencecDNA-based transgenes often function in vivo, but expression levels are frequently low, and such transgenes are often silenced.Inclusion of only one generic intron in a transgene has been shown to augment transgene expression significantlyThis hybrid intron, consisting of an adenovirus splice donor and an immunoglobulin G splice acceptorSelection of the Polyadenylation Cassette SV40T polyAHuman growth hormone generabbit β-globin sequencesThree vectors frequently used as trangenic vectors in Cyagen pRP.Des2d and pRP.Des3d;pHsp68 lacZ;BAC ;Lentiviral shRNA vecotr;pRP.Des2d and pRP.Des3d1pRP/Des(R4R2)4812bpattR4Cm RccdB attR2SV40 pAAm RTB pUC orif1 ori1pRP/Des(R4R3)4812bpattR4ccdBCm R attR3SV40 pAAm RTB pUC orif1 o riGateway Technologypromoter Gene 1st Gene 2ndDestination Vector Expression VectorEF1A-hrGFPCMV-hrGFPpHsp68 lacZ vectorBased on the transcriptional mechanism of Heat shock protein 68;Use pHsp68 lacZ to findout the functional enhancerfragment;pHsp68 lacZ pHsp68 lacZ with enhancerLentiviral shRNA vectorpLLU2GBAC Modification。

Syntax,Morpholog...

Syntax, Morphology, and Semantics of EzafeParviz Parsafar, Ph.D.Yuba Community CollegeAbstractEzafe, whi ch literally means …annexation‟ or …addition‟ and is traditionally known as a “Genitive” marker1, is an indispensable element inside any noun phrase comprising a head modified by at least one non-clausal modifier and/or complement. That is, any study of Persian involving NPs in subject position or predicate position, whether followed by light verbs or thematic verbs, is bound to encounter ezafe in numerous example sentences. Therefore, the present paper, which is a slightly revised version of chapter one in Parsafar(1996), attempts to present a clear understanding of the syntax, morphology, and semantics of ezafe.Although ezafe has been stud ied by many scholars such as Mo‟in(1962)2, Homayunfarrokh (1960), Phillot (1919), Palmer (1971), Sami‟ian (1983), and Karimi and Brame(1986), its grammatical status is not yet quite transparent. Grammarians have regarded ezafe as a polysemous “word” carrying over ten different “meanings/functions”. The purpose of this paper is to unravel the myth and to show that ezafe is a dummy clitic-like morpheme which is semantically void while syntactically it functions as an “associative marker” which subordinates its [+N] host, on the left, to its following complements.If sound, such a conclusion will be reminiscent of Zwicky sand Pullum‟s (1983, 502) observation: “An important point about doing grammatical research on a well-known [or even a relatively well-understood] language is that there can still be surprises. Evidence, sometimes of a subtle and indirect kind, can be uncovered for analyses of a quite unexpected character.”It needs to be mentioned at the outset that the principal focus of this work is on the colloquial language, but there are also numerous references to and examples from the formal registers. In those cases where there is a syntactic or semantic difference between the colloquial and the formal versions of a given example, it will be discussed. Otherwise, the registers of the examples will not be brought up except for emphasis.Pivotal to my adoption of the colloquial language were two significant facts. First, there has been a predominant tendency in the works on Persian to examine basically the formal (or in some cases the literary) language. The disregard for the colloquial language appears to have a primarily stylistic bias which could be overcome through detailed studies of this register.Second, although the colloquial and the formal versions of Farsi are to a large extent identical both syntactically and semantically, there are certain lexical, functional, pragmatic, and even syntactic differences between them. For instance, there are lexical items such as /tu/ …in, inside, into‟, /bæqæl/ …beside‟, and /pæhlu/ …next to‟ which are exclusively employed in the colloquial language or have a greater range of applications here than in the formal versions. Thus, the colloquial focus of the present study will help demonstrate many such discrepa ncies3. ReferencesAdams, Valerie. 1973. An Introduction to Modern English Word-formation. London: Longman Group Limited.Aronoff, Mark. 1976. Word Formation in Generative Grammar. Linguistic Inquiry Monograph No.1. MIT.Bauer, Laurie. 1983. English Word Formation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Bing, Janet Mueller. 1980. Linguistic Rhythm and Grammatical Structure in Afghan Persian. Linguistic Inquiry 11(3): 437-463.Bloomfield, Leonard. 1933. Language. Chicago: University of Chicago edition 1984. Chodzko, A. 1883. Grammaire De La Langue Persane. paris: Maisonneuve & CIE LibrairesÉditeurs.Chomsky,N. 1970. “Remarks on Nominalization” in Jacobs and Rosenbaum 1970. 184-221. Chomsky, N. 1981. Lectures on Government and Binding. Dordrecht, Holland: Foris Publications.Homayunfarrokh, A. R. 1339 (1960). Dastur-e Jame‟-e Zæban-e Farsi. [ A Comprehensive Grammar of the Persian Language]. 2nd. ed. Tehran: Elmi.Horn, Laurence. (p.c.)Insler, Stanley. (p.c.)Jackendoff, R. 1977. X-bar Syntax: A Study of Phrase Structure. Linguistic Inquiry Monograph No. 2. MIT.Karimi, Simin. 1989. Aspects of Persian Syntax, Specificity, and the Theory of Grammar. Seattle: University of Washington Dissertation.Karimi, Simin, and Michael Brame. 1986. A Generalization Concerning the ezafe Construction in Persian. paper presented at the annual meeting of the Western Conference of Linguistics, Canada.Klavans, Judith L. 1985. The Independence of Syntax and Phonology in Cliticization. language 61(1): 95-120.Lazard, Gilbert. 1957. Grammaire du Persian Contemporain. paris: Librairie C. Klincksiek. Lyons, Christopher. 1986. The Syntax of English Genetive C onstructions. Journal of Linguistics 22:123-143. Printed in Great Britain.Lyons, John. 1971. Introduction to Theoretical Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Maling, Joan. 1983. Transitive Adjectives: A Case of Categorical Reanalysis. In Henry and Richards 1983, 253-289.Marantz,Alec. 1989. “Clitics and Phrase Structure” in Baltin and Kroch 1989, 99-116. Marchand, H. 1969. The Categories and Types of Present-Day English Word-Formation, 2nd ed. Munchen: Beck.Mo’in, M. 1340(1961). Mofrad-o Jam‟ [Singular and Plural]. Tehran: Ebn-e Sina Publications. Mo’in, M. 1341 (1962a). Esm-e Mæsdær, Hasel-e Mæsdær [verbal Nouns and Abstract Nouns[. Tehran: Ebn-e Sina.Mo’in, M. 1341(1962b). Ezafe [The Genitive Case]. Tehran: Ebn-e Sina Publications. Moyne, John Abel. 1970. The Structure of Verbal Constructions in Persian. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Dissertation.Moyne, John Abel, and Guy Carden. 1974. Subject Reduplication in Persian. Linguistic Inquiry 5(2): 205-249.Nye, Gertrude E. 1955. The Phonemes and Morphemes of Modern Persian: A Descriptive Study. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan dissertation.Palmer, A. 1971. The Ezafe Construction in Modern Standard Persian. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan dissertation.Parsafar, Parviz. 1990a. The Persian /ra/. Unpublished qualifying paper presented to the faculty, Department of Linguistics, Yale University, New Have, CT.Parsafar, Parviz. 1990b. The Morphology of Modern Persian Suffixes. Unpublished qualifying paper presented to the faculty, Department of Linguistics, Yale University, New Haven, CT. Parsafar, Parviz. 1996. Spatial Prepositions in Modern Persian. New Haven, CT: Yale University dissertation.Perlmutter, David M. 1980. Relational Grammar. in Moravcsik and Wirth, eds.,Syntax and Semantics 13: 195-227. Current Approaches to Syntax, Academic Press.Phillot, D.C. 1919. Higher Persian Grammar. Calcutta: Baptist Mission Press.Quirk, R., Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. 1985. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman.Radford, Andrew. 1981. Transformational Syntax. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Radford, Andrew. 1988. Transformational Grammar. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Riemsdijk, H. C. Van. 1978. A Case Study in Syntactic Markedness: Thw Binding Nature of Prepositional Phrases. Dordecht, Holland: Foris Publications.Rubinchik, Yu. A. 1971. The Modern Persian Language. Moscow: Nauka Publishing House. Sami’ian, Vida. 1983. Structure of Phrasal Categories in Persian: an X-Bar Analysis. Los Angeles: UCLA dissertation.Scalise, S. 1984. generative Morphology. Dordrecht: Foris.Stowell, Timothy Angus. 1981. Origins of Phrase Structure. Massachusetts: MIT dissertation. Windfuhr, Gernot L. 1979. Persian Grammar. The Hague: Mouton P.Zwicky, Arnold M. 1976. On Clitics. Phonologica 1976. ed. by Wolfgang U. Dresser and Oskar E. Pfeiffer. Innsbruck: Innsbrucker Beitrage Zur Sprachwissenschaft.Zwicky, Arnold M. 1977. On Clitics. Bloomington: Indiana University Linguistics Club. Zwicky, Arnold M. 1980. Stranded to. Ohio State University Working Papers in Linguistics 24:166-173.Zwicky, Arnold M. 1982. Stranded to and Phonological Phrasing in English. Linguistics 20:3-57. Zwicky, Arnold M. 1985. Clitics and Particles. Language 61(2): 283-305.Zwicky, Arnold M. and Geoffrey Pullum. 1983. Cliticization vs. Inflectio n: English n‟t. Language 59(3): 502-513.。

英国国家概况PrintingmediaampIT

Magazines

Private Eye( most read fortnightly magazine in 2004-2005)

Take a Break( read by 12 per cent of women ) FHM (most read monthly men’s periodical) .

• According to a survey by National Readership Survey Limited , during the year 2004/05 62 per sent of all people aged 15 and over in Great Britain read a national daily newspaper.

• In term of circulation and readership , newspapers and magazines continue to have considerable impact as significant sources of information and belief.

• A large proportion of people read Sunday newspapers, compared with daily national papers.

• The News of the World was the most read Sunday newspaper , with 19 per cent. Followed by The Mail on Sunday(14per cent)

A basic understanding of the print media is essential in the study of mass communication. The contribution of print media in providing information and transfer of knowledge is remarkable.

charity marketing 慈善营销经典之作

Charity Marketing Meeting Need Through Customer FocusIan BruceFirst published 1994as Meeting Need: Successful charity marketingsecond edition published 1998as Successful Charity MarketingThis edition published 2005 by ICSA Publishing Limited16 Park CrescentLondon W1B 1AH© Ian Bruce 1994, 1998, 2005All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission, in writing, from the publisher.Typeset in Sabon and Franklin Gothic byHands Fotoset, Woodthorpe, NottinghamPrinted and bound in Great Britain byTJ International Ltd, Padstow, CornwallBritish Library Cataloguing in Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: 1-86072-296-2To my parents and the other parent figures in my life: Tom and Una Bruce, Bob and Lillian Barker, John and Edna Stroud, and Peter and Margery RowlandContentsv Preface to the third editionviii Abbreviations xiPart I – The Philosophy,Framework and Tools11What is charity marketing?2Introduction2What is marketing?2Definitions4Case examples5Conclusion172Classical marketing18Introduction18Market segmentation20Marketing research21Competitor analysis23Product24Price26Promotion27Place28Consumer buying behaviour29Role of the manufacturer/service deliverer30Conclusion31Key points313Fundamentals of a charitymarketing approach33Who are we here for?33Customers34Customer take-up behaviour39Social and psychologicalinfluences 39Voluntary exchanges 40Relationship marketing and the customer 43Marketing information and research 44Market segmentation and targeting 50Other-player analysis 53Positioning 57Conclusion 58Key points 594The charity marketing mix 60Construction 60The mix for the sector 63Philosophy 65Product 68Price 85Promotion 89Place 93People 95Physical evidence 97Process 99Conclusion 101Key points 1025How to introduce a marketing approach and a marketing reality 104Reasons for resistance 104Undervaluing needs 105Support for adopting a marketing approach 111Introducing a marketing approach 114C H A R I T Y M A R K E T I N GA needs-led marketingculture115Marketing resources116Marketing activities,processes and plans118Basic marketing/serviceplan121Structure121Conclusion132Key points133 Part II – Applied Charity Marketing134 6Physical goods135 Goods for main beneficiaries135Price136Distribution (place)139Promotion140Target markets142Print and e-publications145For-profit fundraising goods148Helping beneficiaries152Conclusion154Key points155 7Services to beneficiaries157 Introduction157Direct and indirect services157Positioning and other-player(competitor) analysis161Needs research163Market segmentation andtarget markets165Service design andconstruction (product)166Price – overt and hidden171Marketing communications(promotion)176Place – how the service isdistributed180People in service delivery181Physical evidence183Processes184Philosophy184Conclusion185Key points1868Pressure group activity188 Background188Campaigns: case examples192Other-player analysis andpositioning208Targeting213Market research219The proposal220Price222Promotion225Channels of communication(place)226Conclusion228Key points228 9Income and fundraising230 The full income picture230Sector definitions231Income sources232Fundraising235Fundraising methods240Market analysis247Methods of expansion248Donor behaviour250The fundraising product253Price257Promotion258Place/distribution260Conclusion261Key points262 10Identity and positioning264 Trust and confidence264Charity identity (brand)266Target markets269Why is charity identitydevelopment so difficult?270What constitutes the charityidentity?271Research275Other-player analysis280Positioning the charity283viC O N T E N T SRelaunch or repositioning285Conclusion289Key points290 Part III – Key Marketing Approaches for Charities29111Relationship marketing292 What is relationshipmarketing?292Establishing relationships294Strengthening relationships295Customer appreciation andrecognition298Relationship strategies299Financial bonds300Social bonding300Customisation301Structural bonds301Membership301Conclusion30212Partnership marketing303 Partnership marketing inpractice303Partnerships and alliances304A marketing approach305Case examples305Conclusions315 13Marketing: the wayforward317Dominant ethos317A changing world318Tools318Conclusion319Appendix 1:Johns Hopkins’structural operationaldefinition of the broadvoluntary sector320Appendix 2:Office of NationalStatistics’ definition of‘general’ charities withinthe UK voluntary sector321References323 Index333viiPreface to the third editionIt is now just over ten years since the first edition of this book was published. What has happened over that period? In most ways progress has been startling. Since then, the International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing has been launched in this country; non profit marketing articles appear regularly in the Journal of Marketing and the European Journal of Marketing; three more charity marketing books have been published in the UK; a masters degree in marketing and fundraising has been launched; and NCVO holds successful annual conferences on the subject, which are regularly over subscribed – all evidence that interest and commitment is growing at a rapid pace.But whether it is because it is a dark afternoon, or because it is true, I feel a huge drag on acceptance of marketing in our sector, caused by public misconception of the subject – which I put down to the losing battle commercial marketers and their representative bodies are having in maintaining ordinary people’s belief in the breadth and morality of marketing. When I started my career in the 1970s, being known as a marketer engendered approbation; now it requires a defensive explanation as to why I am involved in something so narrow cast and unethical. In the 1970s producers used to say ‘we have to advertise it better’. Now they say ‘we have to market it better’, equating marketing with the last, separate and rather vulgar stage of developing a product. This usage is even rampant in business schools across the UK. Even more worrying, I sense marketing has increasingly been associated with unethical behaviour, often imagined but no less damaging for all that. The high profile usage of the term by the industries of drinks, tobacco, football and politics has certainly not helped – encouraging the view of marketing which I sometimes describe as ‘selling people things they don’t need at prices they cannot afford’.So what do we charity marketers do? I think we can help in our small way. First, we are using marketing for obvious good (although even weviiiP R E F A C E T O T H E T H I R D E D I T I O Nneed to be vigilant over our fundraising marketing ethics). Second, we are pushing back marketing frontiers with our widespread and continuous addressing of multiple target groups/constituencies with differing needs and wishes, some of which pay money and some of which do not, but all of which pay hidden prices. And third, we have the zeal and freshness of new converts to a cause, who are bringing new thinking with new territory. But I do appeal to the overwhelmingly dominant branch of our profession in the commercial world to relaunch the product that is marketing.This third edition has been carefully updated and so readers can be confident that some of the best and newest references are included. However, it is reassuring for our emerging specialism that so much of the earlier writing has stood the test of time. The book is re-structured into three parts. The third part, which is entirely new, contains chapters on relationship marketing and partnership marketing, including cause related marketing (CRM). The chapter on income and fundraising generation has been extensively updated, and all the chapters include revisions. People familiar with commercial marketing can skip Chapter 2.In an attempt to reclaim and make clear the breadth and depth of the marketing contribution, I have once again modified the title. This is intended as a public signal of the fundamental contribution of marketing to the effective running of voluntary and community organisations in order to meet the needs of beneficiaries.All the thanks and appreciation recorded in previous prefaces remain undiminished, especially to the people in Unilever who first taught me about marketing. I wish to add special thanks to colleagues in ICSA, to Susan Richards and Clare Grist Taylor for asking me to do this third edition and to Phil Brown, Kevin Eddy, Kate Ellison, Jacki Reason and Simon Bailey. Ten years is a long time in the life of a business school and my thanks go to the new dynamic leaders helping us to make an impressive impact – David Rhind, David Currie, Steve Haberman, Henrietta Royle and Georges Selim. This has also been an inspirational 18 months in the life of VOLPROF, now transformed into the Centre for Charity Effectiveness, and my thanks go to the Worshipful Company of Management Consultants, particularly John Mclean Fox, Patrick McHugh, Gareth Rees, Barrie Collins, William Barnard, Allan Duigood and Allan Williams. Their contribution has been critical, not leastixC H A R I T Y M A R K E T I N Gbecause it has given me the space to work on this edition. The quadrupling in size and impact of the Centre has also been through the contribution of my Centre colleagues Caroline Copeman, Sue Douthwaite, Denise Fellows, Andrew Forrest, Mary Harris, Jenny Harrow, John Hailey, Karen Hickox, Adah Kay, Peter Grant, Ruth Lesirge, Paul Palmer, Atul Patel and Ian Williams, whose cheerful companionship have aided this writing commission. Lastly, but pre-eminently, I have had unfailing support from Tina, my partner for life.Thanks once again to ICSA for asking for a third edition – I hope you have a good read!Ian BruceMay 2005xAbbreviations4Ps Produce, Price, Promotion, PlaceAIDA Attention, Interest, Desire, ActionAOP Association of Optical PractitionersBA British AirwaysBCO British College of OptometristsBCODP British Council of Organisations of Disabled People BPA British Parachute AssociationBVS Broad Voluntary SectorCAF Charities Aid FoundationCRC Cancer Research CampaignCDI Comprehensive Disability IncomeCRM Cause Related MarketingDARAC Disability Access Rights and Advice ServiceDBC Disability Benefits ConsortiumDCC Disability Charities ConsortiumDDA Disability Discrimination ActDfES Department for Education and SkillsDIG Disability Income GroupDLA Disability Living AllowanceDTI Department of Trade and IndustryDWP Department for Work and PensionsFMCG Fast-moving consumer goodsFODO Federation of Dispensing OpticiansGDP Gross Domestic ProductIANSA International Action Network on Small ArmsICRF Imperial Cancer Research FundLEA Local Education AuthorityNACRO National Association for the Care and Resettlement of OffendersNCH National Children’s HomeC H A R I T Y M A R K E T I N GNCVO National Council for Voluntary OrganisationsNOPWC National Old People’s Welfare CouncilNSPCC National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children NVS Narrow Voluntary SectorOFSTED Office for Standards in EducationONS Office of National StatisticsPR Public RelationsPRO Public Relations OfficerRADAR Royal Association of Disability and Rehabilitation RCSB Royal Commonwealth Society for the Blind/SightSavers RNIB Royal National Institute of the BlindRNID Royal National Institute for Deaf PeopleRNLI Royal National Lifeboat InstitutionRPI Retail Price IndexRSB Royal Society for the BlindRSPB Royal Society for the Protection of BirdsRSPCA Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals SDU Service Delivery UnitSWOT Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, ThreatsTEC Training and Enterprise CouncilUSP Unique Selling PropositionVSO Voluntary Service OverseasWWF World Wildlife Fund (now Worldwide Fund for Nature)PART IThe Philosophy, Framework and Tools1What is charity marketing?IntroductionI am a passionate believer in marketing and in applying a marketing approach to the voluntary sector. This is in part because I was trained as a manager by Unilever, where marketing was, and still is, the ‘way we do it round here’. But the main reason for my continuing passion is that marketing is philosophically and practically well suited to the voluntary and public sectors. What a gift to find a technique that has as its philosophy a dominant ethos of starting with the needs of the consumer, rather than the concerns of the provider. And doesn’t it also just feel right to have a practical process that starts from where the consumer actually is, rather than where we would like them to be? Such a philosophy and practice rings all sorts of bells in my background and current life. For me, as a child of the 1960s, a marketing approach has similarities with community work and community development – giving a major role in the creation and delivery of services to people who were previously regarded as passive recipients. Being married to a Froebelian educator whose core philosophy and practice is the dictum ‘begin where the learner is’ (Friedrich Froebel 1782-1852) has produced an unexpected harmony between an educator and a manager.What is marketing?Essentially, marketing is a way of fitting together the planning and implementation of goods, services or ideas in a practical but sophisti-cated way, and in a way that emphasises the needs of the customer, client or person in need rather than simply trying to improve the efficiency of existing processes or ways of doing things. So much of voluntary sector activity development takes place in what the commercial world would call a product- or production-orientated way. Superficially this can increase efficiency, but the risk in this rapidly changing world is that theW H A T I S C H A R I T Y M A R K E T I N G?product or process becomes increasingly less relevant or appropriate to what customers or clients need and want.Consumer satisfactionThe majority of definitions describe marketing as an activity to help the organisation achieve its goals by providing consumer satisfaction. This description should reassure the charity reader because it describes the key role of the organisation. But it also establishes the key focus on the customer/user/client/patient. In this book I use the term ‘customers’ to cover all of a charity’s target groups and, when appropriate, divide this term into ‘beneficiaries’ and ‘supporters’ (see page 35). However, at best the selection of the appropriate term is a matter of sensitivity and at worst it is a matter of fashion. Too much concentration on terms, in my experience, simply holds up discussion of the more fundamental issues. Negative associationsBut for many people the term ‘marketing’ has negative associations. It describes a process for selling people things they do not need. For those with a centre-to-left political orientation it is associated with an intensely capitalist and commercial environment that is antithetical to the public and not-for-profit sector. For those with a centre-to-right view, it is generally more acceptable, but its application in the public and voluntary sector can seem irrelevant or inappropriate. Even where marketing is accepted, it is often only readily associated with areas such as fundraising and public relations (PR).So, if the term starts with such a bad press, why continue to use it in the public and voluntary sectors? Over the last fifty years the approach, practice and techniques of marketing have transformed the commercial world and its provision of goods. It is also now significantly affecting the world of services. Our world needs to take advantage of these advances. But should we use a new name? I think not. There have been attempts in the public and voluntary sector to use the term ‘public relations’ as an alternative (Bruce 1973), but PR also has negative overtones and is too narrow a concept. Professional practices (such as lawyers and architects) tried a similar approach by substituting the term ‘practice development’, but this did not catch on (A. Wilson 1984, pp. xi–xiv).T H E P H I L O S O P H Y,F R A M E W O R K A N D T O O L SValue-neutralMarketing as a term and a process is value-neutral. It can be used for good or ill. It can and has been applied not only in the commercial world, but also in the not-for-profit world, and even in the former planned economies of Eastern Europe.Despite its ‘discovery’ for the non-profit sector by Kotler and Levy as long ago as 1969, marketing has only achieved a modest penetration into public and not-for-profit organisations in the United Kingdom. As a rough benchmark, best practice is probably at the quality and penetration levels experienced in the commercial world in the 1960s. Over the last few years it has begun to influence strategic planning, service provision and campaigning but, as suggested above, in the main it is only extensively applied in fundraising and PR (Hankinson 2000). However, best practice in these two areas (such as direct mail) is extremely impressive and can teach the commercial world a thing or two. DefinitionsThere is a whole host of definitions of marketing. Most of the more sophisticated ones could be applied to the public and voluntary sector. The one quoted below is by Philip Kotler, Professor of International Marketing at Northwestern University, United States. Kotler has the longest-standing interest of any academic in the field of public and not-for-profit marketing. He developed an early version of the following definition in the 1970s, which has essentially stood the test of time.‘Marketing is the analysis, planning, implementation, and control of carefully formulated programmes designed to bring aboutvoluntary exchanges of values with target markets to achieveinstitutional objectives. Marketing involves designing theinstitution’s offerings to meet the target markets’ needs anddesires, and using effective pricing, communication, anddistribution to inform, motivate, and service the markets.’(Kotler and Fox 1985, p. 7)This comprehensive, albeit tightly packed, definition is helpful because it identifies the different elements of marketing, which helps to indicateW H A T I S C H A R I T Y M A R K E T I N G?how it can be applied in the charity sector. Kotler uses the term ‘offering’in place of ‘product’– the generic term for physical goods and services. In this book I use ‘product’ to cover a charity’s physical goods, services and ideas. Where it is important to draw particular attention to the type of product, I use the terms ‘physical product’, ‘service product’ and ‘idea product’.Andreasen and Kotler (2003) have defined marketing management as:‘The process of planning and executing programs designed toinfluence the behavior of target audiences by creating andmaintaining beneficial exchanges for the purposes of satisfyingindividual and organisational objectives.’(p. 39)Case examplesThe following four short case examples exemplify what the different elements in the definition can mean in practice. While two of the four have been taken from social services and education, they could equally have been taken from health, transport, the arts or sports. The social services study is of a voluntary visiting service for older people run by a local charity, but could also have been a study of a service for families under extreme stress or any other personal social service. The example from education is a school run by a national charity, but again any education service may have been selected. The fundraising example is a charity dinner, but could have been big-gift fundraising, a jumble sale or any other fundraising method. A pressure group involved with the arts forms the final case example, but once again could just as well have been drawn from a number of areas, including social welfare or the environment.。

巴拿马航运法律概览

i

Acknowledgements

JOSEPH & PARTNERS KINCAID – MENDES VIANNA ADVOGADOS ASSOCIADOS LAW OFFICES CHOI & KIM LEXCELLENCE LAW FIRM MORAIS LEITÃO, GALVÃO TELES, SOARES DA SILVA & ASSOCIADOS, RL MORGAN & MORGAN PALACIOS, PRONO & TALAVERA PRAMUANCHAI LAW OFFICE CO, LTD RAJAH & TANN LLP RUGGIERO & FERNANDEZ LLORENTE S FRIEDMAN & CO SABATINO PIZZOLANTE ABOGADOS MARÍTIMOS & COMERCIALES SAN SIMÓN & DUCH SEWARD & KISSEL LLP STUDIO LEGALE MORDIGLIA VERALAW (DEL ROSARIO RABOCA GONZALES GRASPARIL) VGENOPOULOS & PARTNERS LAW FIRM YOSHIDA & PARTNERS

The Shipping Law Review

The Shipping Law Review

Editors James Gosling and Rebecca Warder

Law Business Research

The Shipping Law Review

The Shipping Law Review Reproduced with permission from Law Business Research Ltd. This article was first published in The Shipping Law Review - Edition 1 (published in July 2014 – editors James Gosling and Rebecca Warder). For further information please email Nick.Barette@

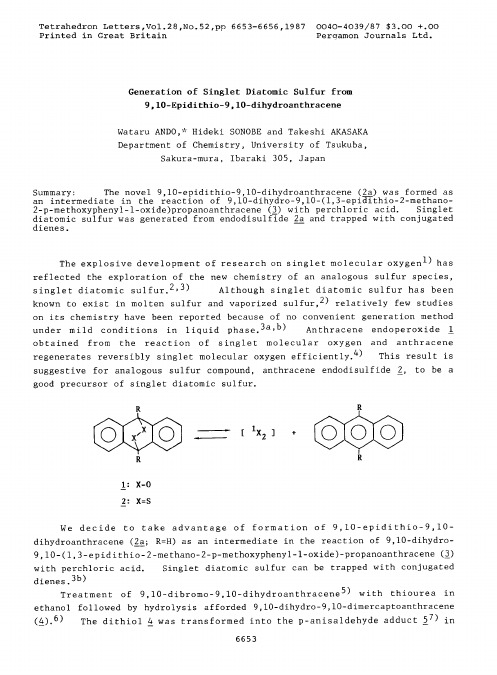

蒽的相关反应

2: x=s -

We

decide

to

take

advantage

of

formation

dihydroanthracene

(a;

R=H) as an intermediate

in the reaction

9,10-(1,3-epidithio-2-methano-2-p-methoxyphenyl-l-oxide)-propanoanthracene with perchloric acid. Singlet diatomic sulfur can be trapped with

This

is

for analogous of singlபைடு நூலகம்t

anthracene

endodisulfide

2,

to be a

precursor

diatomic

sulfur.

*

IX

R

1: x=0

0

z

[V

+

@I?$@

R of 9,10-epidithio-9,10of 9,10-dihydro(2) conjugated

diphenyl-1,3-butadiene

6655

Table. Reaction of Singlet Diatomic Sulfur with Olefins.

Entry

Olefin

Products

and Yields(%)

Ph

Ph 6 -

Ph

& 7

48a)

1’

67b)

11

72b)

52a)

11

dienes.3b) Treatment ethanol (4).6) followed The of 9,10-dibromo-9,10-dihydroanthracene5) afforded with thiourea in

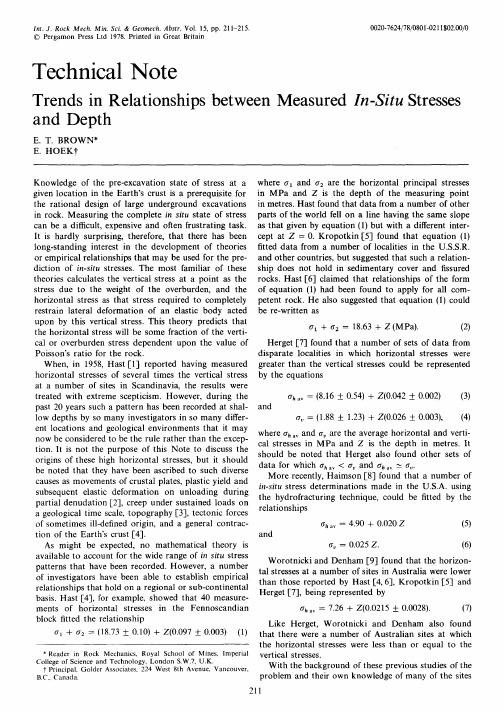

Trends in relationships between measured in-situ stresses and depth

Like Herget, Worotnicki and Denham also found that there were a number of Australian sites at which the horizontal stresses were less than or equal to the vertical stresses. With the background of these previous studies of the problem and their own knowledge of many of the sites 211

av =

(8.16 ± 0.54) + Z(0.042 ___0.002)

(3)

* Reader in Rock Mechanics, Royal School of Mines, Imperial College of Science and Technology, London S.W.7, U.K. t Principal, Golder Associates, 224 West 8th Avenue, Vancouver, B.C., Canada.

Herget [7] found that a number of sets of data from disparate localities in which horizontal stresses were greater than the vertical stresses could be represented by the equations O'h and try = (1.88 +__ 1.23) + Z(0.026 + 0.003), (4) where o" hav and trv are the average horizontal and vertical stresses in M P a and Z is the depth in metres. It should be noted that Herget also found other sets of data for which a hav < av and ah ,v -~ tL. More recently, Haimson [8] found that a number of in-situ stress determinations made in the U.S.A. using the hydrofracturing technique, could be fitted by the relationships O'hav = 4.90 + 0.020 Z and tL = 0.025 Z. (6) Worotnicki and Denham [9] found that the horizontal stresses at a number of sites in Australia were lower than those reported by Hast [4, 6], Kropotkin [5] and Herget [7], being represented by ah,v = 7.26 + Z(0.0215 ± 0.0028). (7) (5)

高速铁路外文资料26

Computers ind. Eagng Vol, 33, Nos 3-4, pp. , 1997 © 1997 Elsevier Science Ltd Printed in Great Britain, All rights reserved 0360-8352/97 $17.00 + 0.00 PII: S0360-8352(97)00253-2

K.e.Dvords:Autonomous Distributed Systems, Negotiation Based Scheduling, Shop Floor Control 1. Introduction Recently, when CIM systems that consist of a large number of automated facilities are considered, it is recognized that the centralized decision-making on the operation of the complex systems is formidable. Thus, many researchers suggested various distributed decision-making strategies for the computer integrated manufacturing enviromnent[l,2]. One of the representative distributed decision-making scheme is the auction-based control method in which interacting subsystems negotiate with each other in order to achieve their own objectives. This framework of the control is based on the architecture of CIM that has intelligent and powerful local controllers connected to each other by communication links[3,4,5]. The advantages of this type of control method are the robustness of the system to various failures and breakdowns of some components and the central controller in the system, the efficiencies supported by a market-like framework, and the possibilities of utilizing the local information in real time. In this study, in order to accommedate virtually all control circumstances encountered in manufacturing, we assume the following control architecture which can be described as follows: The function of the shop floor control system consists of planning, scheduling, and execution function. The planning function is to prepare the process plan that cam be executable considering the status of the shop floor. The process plan may be expressed as a network. In this stage, some nudes, whose corresponding machines are out of order or required tools are absent, should be deleted from the network. Then, the resulting network becomes the executable one. The scheduling function is to determine the most promising route and estimate the expected starting time and the completion time of each operation. In the framework of this paper, the price of each resource will be used to allocate resources efficiently. The execution function is to assign the processing machine and detennine the processing sequence of tasks and revise the schedule using the real time information on the status of the shop floor. Even in this stage, the infomlation on the alternative routing will be kept in order to use in the assignment of tasks. 785 Although most of researchers have described how the auction-basod control strategy may be applied to contrul shop floors in a hard real time environment, few researchers have dealt with how the high performance of the shop floor may be achieved even under the distributed decision-making scheme. In this paper, we try to improve the perfommw,e of the negotiation process by making agents look ahead the future during scheduling the future operations. In the most of the current practices, process planning and scheduling are performed separately. The scheduling is done under the assumption that the process plan is given, and tries to allocate resources to the operations so that the dictated plan is not violated. During the process planning, the detail floor status may not be considered. Both the process planing and scheduling function are responsible for muting parts through the system and setting priorities between individual parts at the processing stations. The integration of the two functions can introduce significant improvements to the efficiency of the lnanufacturing facilities through reduction in scheduling conflicts, reduction of flow time and work-in-precesses, increaso of utilization of production resources and adaptation to irregular shop floor events. In this paper, we suggest a typical auction-based scheduling procedure in which we specify a detail pricing mechanism, a bid construction method, and a negotiation procedure. And we discuss how the decision on the process routing of an order may be integrated into the scheduling ftmction when multiple process plans are allowed.

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

on fixed embryos show that a population of prospective mesoderm cells constrict at their apical ends and their nuclei migrate basally (Leptin and Grunewald, 1990). Apical constriction of cells has been proposed to be a driving force for epithelial invaginations (Burnside, 1973), and computer models suggest that a wave of constrictions transmitted from cell to cell might be sufficient to produce a furrow (Odell et al. 1981). However, it is not possible to determine the temporal and possible causal relationships of the events during epithelial invaginations from studies on fixed embryos. We therefore examined living embryos using threedimensional time-lapse fluorescence microscopy (Hiraoka et al. 1989; Minden et al. 1989). At the cellular blastoderm stage, the Drosophila embryo consists of an epithelial layer of ~6000 columnar cells (and ~40 spherical pole cells. Zalokar and Erk, 1976; Foe and Alberts, 1983). When cellularization is complete, a band of cells (~20 cells wide and ~60 cells long) invaginates to form the ventral furrow. This band is subdivided into two populations: a

Introduction

During the development of an organism, many organs and other complex structures are created by the folding of epithelial sheets. The formation of the germ layers in gastrulation is the earliest example during embryogenesis. The first morphogenetic process during Drosophila gastrulation is the formation of the ventral furrow, which leads to the invagination of the mesoderm (Poulson, 1950; Sonnenblick, 1950). Drosophila ventral furrow formation is an example of epithelial folding that is especially well suited for histological, cell biological and genetical analysis. Compared with other epithelial foldings, it is simple and quick. The process, which takes less than 20min, turns an epithelium of morphologically identical cells into an invaginated tube of cells. No cell division occurs during this period. Like other epithelial invaginations (reviewed in Ettensohn, 1985; Schoenwolf and Smith, 1990), ventral furrow formation involves cell shape changes (Turner and Mahowald, 1977, Leptin and Grunewald, 1990). Studies

Materials and methods

Preparation of embryos

Drosophila melanogaster (strain Oregon R) embryos were dechorionated and mounted ventral side up with double-sided tape (Scotch no. 665) on oxygen permeable teflon membrane (see below). The embryos were dehydrated slightly, covered with 700 weight halocarbon oil (HC Co. Hackensack NJ) and injected as described (Minden et al. 1989). Calf thymus histones H2A and H2B were prepared as previously described (Minden et al. 1989) and injected at a concentration of O^mgml" 1 into the embryo at nuclear cycle 9 to 10. Fl-dextran (70000Mr, Molecular Probes, Eugene OR) at lmgml" 1 was injected into the perivitelline space shortly after the Rh-histone injection. Recordings were done at approximately 22 °C.

Development 112, 365-370 (1991) Printed in Great Britain © The Company of Biologists Limited 1991

365

Drosophila gastrulation: analysis of cell shape changes in living embryos by three-dimensional fluorescence microscopy

366

Z. Kam and others

Results and discussion

central population (8-10 cells wide), whose nuclei move basally and whose apical sides constrict, and a peripheral population (4-5 cells wide on either side of the central population) which follows the central population into the furrow without these shape changes (Leptin and Grunewald, 1990). We have concentrated our analysis here mainly on the behaviour of the central cells, whose shape changes we believe to have an active role in ventral furrow invagination.

Summary

The first event of Drosophila gastrulation is the formation of the ventral furrow. This process, which leads to the invagination of the mesoderm, is a classical example of epithelial folding. To understand better the cellular changes and dynamics of furrow fg Drosophila embryos using three-dimensional time-lapse microscopy. By injecting fluorescent markers that visualize cell outlines and nuclei, we monitored changes in cell shapes and nuclear positions. We find that the ventral furrow invaginates in two phases. During the first 'preparatory' phase, many prospective furrow cells in apparently random positions gradually begin to change shape, but the curvature of the epithelium hardly changes. In the second phase,