C5.1.4 Decision rules

TS16949认证导则(莱茵发布)

关于:IATF为了加强TS16949的价值和可信度,通过发布认证导则第四版“提升认证门槛”1. Site extensions制造现场延伸场地Site extensions as defined previously will no longer exist as part of the ISO/TS 16949 Certification Scheme.制造现场延伸场地将不再存在于ISO/TS 16949 认证方案中IATF will withdraw, and therefore make obsolete, the current possibility to include site extensions effective 1st of April 2014. IATF 将从2014 年4 月1 日开始撤销并从而废除, 目前包含现场延伸场地的的认证Clients with an existing manufacturing site extension will need to transition this site extension to a single site between the time period of 1st of April 2014 – 1st of April 2015. 现有制造现场延伸场地的客户将需要按CB 公告2013-006 所述流程在2014 年4 月1日至2015 年4 月1 日期间将其转换为单个现场.Different Choices for transition”您可以选择下列方案之一进行“转换”:1 Single Site Certification单现场认证2 Corporate Scheme, if comply with Rules 5.3TÜV Rheinland Greater ChinaPage 2 of 7如果满足认证规则5.3 条款关于“集团审核方案”的要求,可与现在主证书相结合,形成“集团审核方案”。

Syllabus Design

Language Teaching:A Scheme. for Teacher Education Editors: C N Callan and H G WiddowsonSyllabus Design David NunanThe author and series editors vi Introduction viiSection One: Defining syllabus design1 1The scope of syllabus design3 1.1Introduction3 1.2 A general curricnlum model4 1.3Defining 'syllabus'5 1.4The role of the classroom teacher7 1.5Conclusion8 2Points of departure10 2.1Introduction10 2.2Basic orientations11 2.3Learning purpose13 2.4Learning goals24 2.5Conclusion25 3Product-oriented syllabuses27 3.1Introduction27 3.2Analytic and synthetic syllabus planning27 3.3Grammatical syllabuses28 3.4Criticizing grammatical syllabuses30 3.5Functional-notional syllabuses35 3.6Criticizing functional-notional syllabuses36 3.7Analytic syllabuses37 3.8Conclusion39 4Process-oriented syllabuses40 4.1Introduction40 4.2Procedural syllabuses42 4.3Task-based syllabuses444.4Content syllabuses48 4.5The natural approach51 4.6Syllabus design and methodology52 4.7Grading tasks54 4.8Conclusion60 5Objectives615.1Introduction61 5.2Types of objective61 5.3Performance objectives in language teaching63 5.4Criticizing performance objectives67 5.5Process and product objectives69 5.6Conclusion71Section Two: Demonstrating syllabus design73 6Needs and goals75 6.1Introduction75 6.2Needs analysis75 6.3From needs to goals79 6.4Conclusion84 7Selecting and grading content85 7.1Introduction85 7.2Selecting grammatical components86 7.3Selecting functional and notional components87 7.4Relating grammatical, functional, and notionalcomponents87 7.5Grading content92 7.6Conclusion95 8Selecting and grading learning tasks96 8.1Introduction96 8.2Goals, objectives, and tasks96 8.3Procedural syllabuses98 8.4The natural approach102 8.5Content-based syllabuses104 8.6Levels of difficulty107 8.7Teaching grammar as process118 8.8Conclusion1219Selecting and grading objectives122 9.1Introduction)122 9.2Product-oriented objectives122 9.3Process-oriented objectives131 9.4Conclusion133Section Three: Exploring syllabus design135 10General principles137 10.1Curriculum and syllabus models137 10.2Purposes and goals140 10.3Syllabus products144 10.4Experiential content147 10..5Tasks and activities149 10.6Objectives153Glossary158Further reading160Bibliography161Index166SECTION ONEDefining syllabus designThe scope of syllabus design1.1 IntroductionWe will start by outlining the scope of syllabus design and relating it to the broader field of curriculum development. Later, in 1.4, we shall also look at the role of the teacher in syllabus design.Within the literature, there is some confusion over the terms 'syllabus' and 'curriculum'. It would, therefore, be as well to give some indication at the outset of what is meant here by syllabus, and also how syllabus design is related to curriculum development.• TASK 1As a preliminary activity, write a short definition of the terms'syllabus' and 'curriculum'.In language teaching, there has been a comparative neglect of systematic curriculum development. In particular, there have been few attempts to apply, in any systematic fashion, principles of curriculum development to the planning, implementation, and evaluation of language programmes.Language curriculum specialists have tended to focus on only part of the total picture — some specializing in syllabus design, others in methodolo nfragmented approach has been criticized, and there have been calls for a more comprehensive approach to language curriculum design (see, for example, Breen and Candlin 1980; Richards 1984; Nunan 1985). The present book is intended to provide teachers with the skills they need to address, in a systematic fashion, the problems and tasks which confront them in their programme planning.Candl in (1984) suggests that curricula are concerned with making general statements about language learning, learning purpose and experience, evaluation, and the role relationships of teachers and learners. According to Candlin, they will also contain banks of learning items and suggestions about how these might be used in class. Syllabuses, on the other hand, are more localized and are based on accounts and records of what actually happens at die classroom level as teachers and learners apply a given curriculum to their own situation. These accounts can be used to make subsequent modifications to the curriculum, so that the developmental process is ongoing and cyclical.1.2 A general curriculum modelTASK 2Examine the following planning tasks and decide on the order inwhich they might be carried out.—monitoring and assessing student progress— selecting suitable materials—stating the objectives of the course—evaluating the course—listing grammatical and functional components—designing learning activities and tasks—instructing students—identifying topics, themes, and situationsh is possible to study 'the curriculum' of an educational institution from anumber of different perspectives. lo the first instance we can look at curriculum planning, that is at decision making, in relation to identifying learners' needs and purposes; establishing goals and objectives; selecting and grading content; organizing appropriate learning arrangements and learner groupings; selecting, adapting, or developing appropriate mate-rials, learning tasks, and assessment and evaluation tools.Alternatively, we can study the curriculum 'in action' as it were. This second perspective takes us into the classroom itself. Here we can observe the teaching/learning process and study the ways in which the intentions of the curriculum planners, which were developed during the planning phase, are translated into action.Yet another perspective relates to assessment and evaluation. From this perspective, we would try and find out what students had learned and what they had failed to learn in relation us what had been planned. Additionally, we might want to find out whether they had learned anything which had not been planned. We would also want to account for our findings, to make judgements about why some things had succeeded and others had failed, and perhaps to make recommendations about what changes might be made to improve things in the future.Filially, we might want to study the management of the teaching institution, looking at the resources available and how these are utilized, hose the institution relates to and responds to the wider community, how constraints imposed by limited resources and the decisions of administra-tors affect what happens in the classroom, and so on.All of these perspectives taken together represent the field of curriculum study. As we can see, the field is a large .d complex one.It is important that, in the planning, implementation, and evaluation of a given curriculum, all elements be integrated, so that decisions made at onelevel are not in conflict with those made at another. For instance, in courses based on principles of communicative language teaching, it is important that these principles are reflected, not only in curriculum documents and syllabus plans, but also in classroom activities, patterns of classroom interaction, and in tests of communicative performance.1.3 Defining 'syllabus'There are several conflicting views on just what it is that distinguishes syllabus design from curriculum development. There is also some disagreement about the nature of 'the syllabus'. In books and papers on the subject, it is possible to distinguish a broad and a narrow approach to syllabus design.The narrow view draws a clear distinction between syllabus design and methodology. Syllabus design is seen as being concerned essentially with the selection and grading of content, while methodology is concerned with the selection of learning tasks and activities. Those who adopt a broader communicative language teaching the distinction between content and tasks is difficult to sustain.The following quotes have been taken from Brumfit (1984) which provides an excellent overview of the range and diversity of opinion on syllabus design. The broad and narrow views are both represented in the book, as you will see from the quotes.■ TASK 3As you read the quotes, see whether you can identify which writersare advocating a broad approach and which a narrow approach.1 . . .I would like to draw attention to a distinction . . . betweencurriculum or syllabus, that is its content, structure, parts andorganisation, and, . . t.vhat in curriculum theory is often calledcurriculum processes, that is curriculum development, imple-mentation, dissemination and evaluation. The former is con-cerned with the WHAT of curriculum: what the curriculum is likeor should be like; the latter is concerned with the WHO andHOW of establishing the curriculum.(Stern 1984: 10-11)2 [The syllabus] replaces the concept of 'method', and the syllabusis now seen as an instrument by which the teacher, with the helpof the syllabus designer, can achieve a degree of 'fit' between theneeds and aims of the learner (as social being and as individual)and the activities which will take place in the classroom.(Yalden 1984: 14)3 ... the syllabus is simply a framework within which activities canbe carried mit: a teaching device to facilitate learning. It onlybecomes a threat to pedagogy when it is regarded as absolute rulesfor determining what is to be learned rather than points ofreference from which bearings can be taken.(Widclowson 1984: 26)4 We might . .. ask whether it is possible to separate so easily whatwe have been calling content from what we have been callingmethod or procedure, or indeed whether we can avoid bringingevaluation into the debate?5 Any syllabus will express—however indirectly—certain assump-tions about language, about the psychological process of learn-ing, and about the pedagogic and social processes within aclassroom.(Breen 1984: 49)6 . . . curriculum is a very general concept which involvesconsideration of the whole complex of philosophical, social andadministrative factors which contribute to the planning of aneducational program. Syllabus, on the other hand, refers to thatsubpart of curriculum which is concerned with a specification ofwhat units will be taught (as distinct from how they will betaught, which is a matter for methodology).(Allen 1984: 61)7 Since language is highly complex and cannot be taught all at thesame time, successful teaching requires that there should be aselection of material depending on the prior definition ofobjectives, proficiency level, and duration of course. Thisselection takes place at the syllabus planning stage.(op. cit.: 65)As you can see, some language specialists believe that syllabus (the selection and grading of content) and methodology should be kept separate; others think otherwise. One of the issues you will have to decide on as you work through this book is whether you thi iik syllabuses should be defined solely in terms of the selection and grading of contera, or whether they should also attempt to specify and grade learning tasks and activities.Here, we shall take as our point of departure the rather traditional notion that a syllabus is a statement of content which is used as the basis for planning courses of various kinds, and that the task of the syllabus designer is to select and grade this content. To begin with, then, we shall distinguish between syllabus design, which is concerned with the 'what of a languageprogramme, and methodology, which is concerned with the 'how'. (Later, we shall look at proposals for 'procedural' syllabuses in which the distinction between the 'what' and the 'how' becomes difficult to sustain.) One document which gives a detailed account of the various syllabus components which need to be corisidered in developing language courses is Threshold Level English (van Ek 1975). van Ek lists the following as necessary components of a language syllabus:1 the situations in which the foreign language will be used, includ-ing the topics which trill be dealt with;2 the language activities in which the learner will engage;3 the language functions which the learner will fulfil;4 what the learner will be able to do with respect to each topic;5 the general notions which the learner will be able to handle;6 the specific (topic-related) notions which the learner will be ableto handle;7 the language forms which the learner will be able to use;8 the degree of skill with which the learner will be able to perform.(van Ek 1975: 8-9)•TASK 4Do you think that van Ek subscribes to a 'broad' or 'narrow' view ofsyllabus design?Which, if any, of the above components do you think are beyond thescope of syllabus design?1.4 The role of the classroom teacherIn a recent book dealing, among other things, with syllabus design issues, Bell (1983) claims that teachers are, in the main, consumers of other people's syllabuses; in other words, that their role is to implement the plans of applied linguists, government agencies, and so on. While some teachers have a relatively free hand in designing the syllabuses on which their teaching programmes are based, most are likely to be, as Bell suggests, consumers of other people's syllabuses.•Study the following list of planning tasks.In your experience, for which of these tasks do you see the classroomteacher as having primary responsibility?Rate each task on a scale from 0 (no responsibility) to 5 (totalresponsibility).—identifying learners' communicative needs0 1 2 3 4 5—selecting and grading syllabus content0 1 2 3 4 5— grouping learners into different classesor learning arrangements0 1 2 3 4 5— selecting/creating materials and learningactivities0 1 2 3 4 5—monitoring and assessing learner progress0 1 2 3 4 5—course evaluation0 1 2 3 4 5 In a recent study of an educational system where classroom teachers are expected to design, implement, and evaluate their own curriculum, one group of teachers, when asked the above question, stated that they saw themselves as having primary responsibility for all of the above tasks except for the third one (grouping learners). Some of the teachers in the system felt quite comfortable with an expanded professional role. Others felt that syllabus development should be carried out by people with specific expertise, and believed that they were being asked to undertake tasks for which they were not adequately trained (Nunan 1987).■ TASK 6What might be the advantages andlor disadvantages of teachers inyour system designing their own syllabuses?Can you think of any reasons why teachers might be discouragedfrom designing, or might not want to design their own syllabuses?Are these reasons principally pedagogic, political, or administra 1.5 ConclusionIn 1, I have tried to provide some idea of the scope of syllabus design. I have suggested that traditionally syllabus design has been seen as a subsidiary component of curriculum design. 'Curriculum' is concerned with the planning, implementation, evaluation, management, and administration of education programmes. 'Syllabus', on the other hand, focuses more narrowly on the selection and grading of content.While it is realized that few teachers are in the position of being able to design their own syllabuses, it is hoped that most are in a position to interpret and modify their syllabuses in the process of translating them into action. The purpose of this book is therefore to present the central issues and options available for syllabus design in order to provide teachers with the necessary knowledge and skills for evaluating, and, where feasible, modifying and adapting the syllabuses with which they work. At the very least, this book should help you understand (and therefore more effectively exploit) the syllabuses and course materials on which your programmes are based.■ TASK 7Look back at the definitions you wrote in Task 1 and rewrite these in the light of the information presented in 1.In what ways, if any, do your revised definitions differ from the onesyou wrote at the beginning?In 2, we shall look at some of the starting points in syllabus design. The next central question to be addressed is, 'Where does syllabus content come from?' In seeking answers to this question, we shall look at techniques for obtaining information from and about learners for use in syllabus design. We shall examine the controversy which exists over the very nature of language itself ancl how this influences the making of decisions about what to include in the syllabus. We shall also look at the distinction between product-oriented and process-oriented approaches to syllabus design. These two orientations are studied in detail in 3 and 4. The final part of Section One draws on the content of the preceding parts and relates this content to the issue of objectives. You will be asked to consider whether or not we need objectives, and if so, how these should be formulated.2 Points of departure2.1 IntroductionIn 1 it was argued that syllabus design was essentially concerned with the selection and grading of content. As such, it formed a sub-component of the planning phase of curriculum development. (You will recall that the curriculum has at least three phases: a planning phase, an implementation phase, and an evaluation phase.)The first question to confront the syllabus designer is where the content is to come from in the first place. We shall now look at the options available to syllabus designers in their search for starting points in syllabus design.■ TASK 8Can you think of any ways in which our beliefs about the nature oflanguage and learning might in fl uence our decision-making on whatto put into the syllabus and how to grade it?If we had consensus on just what it was that we were supposed to teach in order for learners to develop proficiency in a second or foreign language; if we knew a great deal more than we do about language learning; if it were possible to teach the totality of a given language, and if we had complete descriptions of the target language, problems associated with selecting and sequencing content and learning experiences would be relatively straight-forward. As it happens, there is not a great deal of agreement within the teaching profession on the nature of language and language learning. As a consequence, we must make judgements in selecting syllabus components from all the options which are available to us. As Breen (1984) points out, these judgements are not yalue-free, but reflect our beliefs about the nature of language and learning. In this and the other parts in this section, we shall see how value judgements affect decision-making in syllabus design.The need to make value judgements and choices in deciding what to include in (or omit from) specifications of content and which elements are to be the basic building blocks of the syllabus, presents syllabus designers with constant problems. The issue of content selection becomes particularly pressing if the syllabus is intended to underpin short courses. (It could be argued that the shorter the course, the greater the need for precision in content specification.)2.2 Basic orientationsUntil fairly recently, most syllabus designers started out by drawing up lists of grammatical, phonological, and vocabulary items which were then graded according to difficulty and usefulness. The task for the learner was seen as gaining mastery over these grammatical, phonological, and vocabulary items.Learning a language, it was assumed, entails mastering the elementsor building blocks of the language and learning the rules by whirlsthese elements are combined, from phoneme to morpheme to wordto phrase to sentence.(Richards and Rodgers 1986: 49)During the 1970s, communicative views of language teaching began to be incorporated into syllabus design. The central cpiestion for proponents of this new view was, 'What does the learner wantineed to do with the target language?' rather than, 'What are the linguistic elements which the learner needs to master?' Syllabuses began to appear in whirls content was specified, not only in terms of the grammatical elements whirls the learners were expected to master, but also in terms of the functional skills they would need to master in order to communicate successfully.This movement led in part to the development of English for Specific Purposes (ESP). Here, syllabus designers focused, not only on language functions, but also on experiential content (that is, the subject matter through which the language is taught).Traditionally, linguistically-oriented syllabuses, along with many so-called communicative syllabuses, shared one thing in common: they tended to focus on the things that learners should know or be able to do as a result of instruction. In the rest of this book we shall refer to syllabuses in which content is stated in terms of the outcomes of instruction as 'product-oriented'.As we have already seen, a distinction is traditionally drawn between syllabus design, which is concerned with outcomes, and methodology, which is concerned with the process through which these outcomes are to be brought about. Recently, however, some syllabus designers have suggested that syllabus content might be specified in terms of learning tasks and activities. They justify this suggestion on the grounds that communica-tion is a process rather than a set of products.In evaluating syllabus proposals, we have to decide whether this view represents a fundamental change in perspective, or whether those advocating process syllabuses have made a category error; whether, in fact, they are really addressing methodological rather than syllabus issues. This is something which you will have to decide for yourself as you work through this book.■ TASK 9At this stage, what is your view on the legitimacy of defining syllabuses in terms of learning processes? Do you think that syllabuses should list and grade learning tasks and activities as well as linguistic content?A given syllabus will specify all or some of the following: grammatical structures, functions, notions, topics, themes, situations, activities, and tasks. Each of these elements is either product or process oriented, and the inclusion of each will be justified according to beliefs about the nature of language, the needs of the learner, or the nature of learning.In the rest of this book, we shall be making constant references to and comparisons between process and product. What we mean when we refer to 'process' is a series of actions directed toward some end. The 'product' is the end itself. This may be clearer if we consider some examples. A list of grammatical structures is a product. Classroom drilling undertaken by learners in order to learn the structures is a process. The interaction of two speakers as they communicate with each other is a process. A tape recording of their conversation is a product.Did you find that some elements could be assigned to more than one orientation or point of reference? Which were these?2.3 Learning purposeIn recent years, a major trend in language syllabus design has been the use of information from and about learners in curriculum decision-making. In this section, we shall look at some of the ways in which learner data have been used to inform decision-making in syllabus design. In the course of the discussion we shall look at the controversy over general and specific purpose syllabus design.Assumptions about the learner's purpose in undertaking a language cosiese, as well as the syllabus designer's beliefs about the nature of language and learning can have a marked influence on the shape of the syllabus on which the course is based. Learners' purposes will vary according to how specific they are, and how immediately learners wish to employ their developing language skills.■ TASK 11Which of the following statements represent specific language needsand which are more general?'I want to be able to talk to my neighbours in English.''I want to study microbiology in an English-speaking university.''I want to develop an appreciation of German culture by studyingthe language.''I want to be able to communicate in Greek.''I want my daughter to study French at school so she can matriculateand read French at university.''I want to read newspapers in Indonesian.''I want to understand Thai radio broadcasts.''I need "survival" English.''I want to be able to read and appreciate French literature.''I want to get a better job at the factory.''I want to speak English.''I want to learn English for nursing.'For which of the above would it be relatively easy to predict thegrammar and topics to be listed in the syllabus?For which would it be difficult to predict the grammar and topics?Techniques and procedures for collecting information to be used in syllabus design are referred to as needs analysis. The se techniques have been borrowed and adapted from other areas of training and development, particularly those assoeiated with industry and technology.• TASK 12One general weakness of most of the literature on needs analysis is the tendency to think only in terms of learner needs. Can you think of any other groups whose needs should be considered? Information will need to be collected, not only on why learners want to learn the target language, but also about such things as societal expectations and constraints and the resources available for implementing the syllabus.Broadly speaking, there arc two different types of needs analysis used by language syllabus designers. The first of these is learner analysis, while the second is task analysis.Learner analysis is based on information about the learner. The central question of concern to the syllabus designer is: Tor what purpose or purposes is the learner learning the language?' There are many other subsidiary questions, indeed it is possible to collect a wide range of information as can be seen from the following data collection forms.1* TASK 13Which of the above information do you think is likely to be most useful for planning purposes?What are some of the purposes to which the information might be put?The information can serve many purposes, depending on the nature of the educational institution in which it is to be used. In the first instance, it can guide the selection of content. It may also be used to assign learners to classgroupings. This will be quite a straightforward matter if classes are basedsolely on proficiency levels, but much more complicated if they are designed to reflect the goals and aspirations of the learners. In addition, the data can be used by the teacher to modify the syllabus and methodology so they are more acceptable to the learners, or to alert the teacher to areas of possible conflict.•TASK 14What sort of problems might the teacher be alerted to?HOW, in your opinion, might these be dealt with?With certain students, for example older learners or those who have only experienced traditional educational systems, there are numerous areas of possible conflict within a teaching programme. These potential points of conflict can be revealed through needs analysis. For example, the data might indicate that the majority of learners desire a grammatically-based syllabus with explicit instruction. If teachers are planning to follow a non-traditional approach, they may need to negotiate with the learners and modify the syllabus to take account of learner perceptions about the nature of language and language learning. On the other hand, if they are strongly committed to the syllabus with which they are working, or if the institution is fairly rigid, they may wish to concentrate, in the early part of the course, on activities designed to convince learners of the value of the approach being taken.•TASK 15Some syllabus designers differentiate between 'objective' and 'subjective' information.What do you think each of these terms refers to?Which of the items in the sample data collection forms in Task 12 relate to 'objective' information, and which to 'subjective' informa-tion?'Objective' data is that factual information which does not require the attitudes and views of the learners to be taken into account. Thus, biographical information on age, nationality, home language, etc. is said to be 'objective'. 'Subjective' information, on the other hand, reflects the perceptions, goals, and priorities of the learner. It will include, among other things, information on why- the learner has undertaken to learn a second language, and the classroom tasks and activities which the learner prefers. The second type of analysis, task analysis, is employed to specify and categorize the language skills required to carry out real-world communica-tive tasks, and often follows the learner analysis which establishes the communicative purposes for which the learner wishes to leant the。

RoHS排外条款英文

DIRECTIVE2002/95/EC OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCILof27January2003on the restriction of the use of certain hazardous substances in electrical and electronic equipmentTHE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION,Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Commu-nity,and in particular Article95thereof,Having regard to the proposal from the Commission(1),Having regard to the opinion of the Economic and Social Committee(2),Having regard to the opinion of the Committee of Regions(3),Acting in accordance with the procedure laid down in Article 251of the Treaty in the light of the joint text approved by the Conciliation Committee on8November2002(4),Whereas:(1)The disparities between the laws or administrativemeasures adopted by the Member States as regards therestriction of the use of hazardous substances in elec-trical and electronic equipment could create barriers totrade and distort competition in the Community andmay thereby have a direct impact on the establishmentand functioning of the internal market.It thereforeappears necessary to approximate the laws of theMember States in this field and to contribute to theprotection of human health and the environmentallysound recovery and disposal of waste electrical and elec-tronic equipment.(2)The European Council at its meeting in Nice on7,8and9December2000endorsed the Council Resolution of4December2000on the precautionary principle.(3)The Commission Communication of30July1996onthe review of the Community strategy for waste manage-ment stresses the need to reduce the content of hazar-dous substances in waste and points out the potentialbenefits of Community-wide rules limiting the presenceof such substances in products and in productionprocesses.(4)The Council Resolution of25January1988on aCommunity action programme to combat environmentalpollution by cadmium(5)invites the Commission topursue without delay the development of specificmeasures for such a programme.Human health also hasto be protected and an overall strategy that in particularrestricts the use of cadmium and stimulates research intosubstitutes should therefore be implemented.The Reso-lution stresses that the use of cadmium should be limitedto cases where suitable and safer alternatives do notexist.(5)The available evidence indicates that measures on thecollection,treatment,recycling and disposal of wasteelectrical and electronic equipment(WEEE)as set out inDirective2002/96/EC of27January2003of theEuropean Parliament and of the Council on waste elec-trical and electronic equipment(6)are necessary toreduce the waste management problems linked to theheavy metals concerned and the flame retardantsconcerned.In spite of those measures,however,signifi-cant parts of WEEE will continue to be found in thecurrent disposal routes.Even if WEEE were collectedseparately and submitted to recycling processes,itscontent of mercury,cadmium,lead,chromium VI,PBBand PBDE would be likely to pose risks to health or theenvironment.(6)Taking into account technical and economic feasibility,the most effective way of ensuring the significant reduc-tion of risks to health and the environment relating tothose substances which can achieve the chosen level ofprotection in the Community is the substitution of thosesubstances in electrical and electronic equipment by safeor safer materials.Restricting the use of these hazardoussubstances is likely to enhance the possibilities andeconomic profitability of recycling of WEEE anddecrease the negative health impact on workers in recy-cling plants.(7)The substances covered by this Directive are scientificallywell researched and evaluated and have been subject todifferent measures both at Community and at nationallevel.(8)The measures provided for in this Directive take intoaccount existing international guidelines and recommen-dations and are based on an assessment of availablescientific and technical information.The measures arenecessary to achieve the chosen level of protection of(1)OJ C365E,19.12.2000,p.195and OJ C240E,28.8.2001,p.303.(2)OJ C116,20.4.2001,p.38.(3)OJ C148,18.5.2001,p.1.(4)Opinion of the European Parliament of15May2001(OJ C34E,7.2.2002,p.109),Council Common Position of4December2001(OJ C90E,16.4.2002,p.12)and Decision of the European Parlia-ment of10April2002(not yet published in the Official Journal).Decision of the European Parliament of18December2002andDecision of the Council of16December2002.(5)OJ C30,4.2.1988,p.1.(6)See page24of this Official Journal.human and animal health and the environment,havingregard to the risks which the absence of measures wouldbe likely to create in the Community.The measuresshould be kept under review and,if necessary,adjustedto take account of available technical and scientific infor-mation.(9)This Directive should apply without prejudice toCommunity legislation on safety and health require-ments and specific Community waste management legis-lation,in particular Council Directive91/157/EEC of18March1991on batteries and accumulators containingcertain dangerous substances(1).(10)The technical development of electrical and electronicequipment without heavy metals,PBDE and PBB shouldbe taken into account.As soon as scientific evidence isavailable and taking into account the precautionary prin-ciple,the prohibition of other hazardous substances andtheir substitution by more environmentally friendly alter-natives which ensure at least the same level of protectionof consumers should be examined.(11)Exemptions from the substitution requirement should bepermitted if substitution is not possible from the scien-tific and technical point of view or if the negative envir-onmental or health impacts caused by substitution arelikely to outweigh the human and environmental bene-fits of the substitution.Substitution of the hazardoussubstances in electrical and electronic equipment shouldalso be carried out in a way so as to be compatible withthe health and safety of users of electrical and electronicequipment(EEE).(12)As product reuse,refurbishment and extension of life-time are beneficial,spare parts need to be available.(13)The adaptation to scientific and technical progress of theexemptions from the requirements concerning phasingout and prohibition of hazardous substances should beeffected by the Commission under a committee proce-dure.(14)The measures necessary for the implementation of thisDirective should be adopted in accordance with CouncilDecision1999/468/EC of28June1999laying downthe procedures for the exercise of implementing powersconferred on the Commission(2),HAVE ADOPTED THIS DIRECTIVE:Article1ObjectivesThe purpose of this Directive is to approximate the laws of the Member States on the restrictions of the use of hazardous substances in electrical and electronic equipment and to contri-bute to the protection of human health and the environmen-tally sound recovery and disposal of waste electrical and elec-tronic equipment.Article2Scope1.Without prejudice to Article6,this Directive shall apply to electrical and electronic equipment falling under the cate-gories1,2,3,4,5,6,7and10set out in Annex IA to Direc-tive No2002/96/EC(WEEE)and to electric light bulbs,and luminaires in households.2.This Directive shall apply without prejudice to Commu-nity legislation on safety and health requirements and specific Community waste management legislation.3.This Directive does not apply to spare parts for the repair, or to the reuse,of electrical and electronic equipment put on the market before1July2006.Article3DefinitionsFor the purposes of this Directive,the following definitions shall apply:(a)‘electrical and electronic equipment’or‘EEE’means equip-ment which is dependent on electric currents or electro-magnetic fields in order to work properly and equipment for the generation,transfer and measurement of such currents and fields falling under the categories set out in Annex IA to Directive2002/96/EC(WEEE)and designed for use with a voltage rating not exceeding1000volts for alternating current and1500volts for direct current;(b)‘producer’means any person who,irrespective of the sellingtechnique used,including by means of distance communi-cation according to Directive97/7/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of20May1997on the protection of consumers in respect of distance contracts(3):(i)manufactures and sells electrical and electronic equip-ment under his own brand;(ii)resells under his own brand equipment produced by other suppliers,a reseller not being regarded as the‘producer’if the brand of the producer appears on theequipment,as provided for in subpoint(i);or (iii)imports or exports electrical and electronic equipment on a professional basis into a Member State. Whoever exclusively provides financing under or pursuant to any finance agreement shall not be deemed a‘producer’unless he also acts as a producer within the meaning of subpoints(i) to(iii).(1)OJ L78,26.3.1991,p.38.Directive as amended by CommissionDirective98/101/EC(OJ L1,5.1.1999,p.1).(2)OJ L184,17.7.1999,p.23.(3)OJ L144, 4.6.1997,p.19.Directive as amended by Directive2002/65/EC(L271,9.10.2002,p.16).Article4Prevention1.Member States shall ensure that,from1July2006,new electrical and electronic equipment put on the market does not contain lead,mercury,cadmium,hexavalent chromium,poly-brominated biphenyls(PBB)or polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDE).National measures restricting or prohibiting the use of these substances in electrical and electronic equipment which were adopted in line with Community legislation before the adoption of this Directive may be maintained until1July 2006.2.Paragraph1shall not apply to the applications listed in the Annex.3.On the basis of a proposal from the Commission,the European Parliament and the Council shall decide,as soon as scientific evidence is available,and in accordance with the prin-ciples on chemicals policy as laid down in the Sixth Commu-nity Environment Action Programme,on the prohibition of other hazardous substances and the substitution thereof by more environment-friendly alternatives which ensure at least the same level of protection for consumers.Article5Adaptation to scientific and technical progress1.Any amendments which are necessary in order to adapt the Annex to scientific and technical progress for the following purposes shall be adopted in accordance with the procedure referred to in Article7(2):(a)establishing,as necessary,maximum concentration valuesup to which the presence of the substances referred to in Article4(1)in specific materials and components of elec-trical and electronic equipment shall be tolerated;(b)exempting materials and components of electrical and elec-tronic equipment from Article4(1)if their elimination or substitution via design changes or materials and compo-nents which do not require any of the materials or substances referred to therein is technically or scientifically impracticable,or where the negative environmental,health and/or consumer safety impacts caused by substitution are likely to outweigh the environmental,health and/or consumer safety benefits thereof;(c)carrying out a review of each exemption in the Annex atleast every four years or four years after an item is added to the list with the aim of considering deletion of materials and components of electrical and electronic equipment from the Annex if their elimination or substitution via design changes or materials and components which do not require any of the materials or substances referred to inArticle4(1)is technically or scientifically possible,provided that the negative environmental,health and/or consumer safety impacts caused by substitution do not outweigh the possible environmental,health and/or consumer safety benefits thereof.2.Before the Annex is amended pursuant to paragraph1, the Commission shall inter alia consult producers of electrical and electronic equipment,recyclers,treatment operators,envir-onmental organisations and employee and consumer ments shall be forwarded to the Committee referred to in Article7(1).The Commission shall provide an account of the information it receives.Article6ReviewBefore13February2005,the Commission shall review the measures provided for in this Directive to take into account,as necessary,new scientific evidence.In particular the Commission shall,by that date,present propo-sals for including in the scope of this Directive equipment which falls under categories8and9set out in Annex IA to Directive2002/96/EC(WEEE).The Commission shall also study the need to adapt the list of substances of Article4(1),on the basis of scientific facts and taking the precautionary principle into account,and present proposals to the European Parliament and Council for such adaptations,if appropriate.Particular attention shall be paid during the review to the impact on the environment and on human health of other hazardous substances and materials used in electrical and elec-tronic equipment.The Commission shall examine the feasibility of replacing such substances and materials and shall present proposals to the European Parliament and to the Council in order to extend the scope of Article4,as appropriate.Article7Committee1.The Commission shall be assisted by the Committee set up by Article18of Council Directive75/442/EEC(1).2.Where reference is made to this paragraph,Articles5and 7of Decision1999/468/EC shall apply,having regard to Article8thereof.The period provided for in Article5(6)of Decision1999/468/ EC shall be set at three months.3.The Committee shall adopt its rules of procedure.(1)OJ L194,25.7.1975,p.39.Article8PenaltiesMember States shall determine penalties applicable to breaches of the national provisions adopted pursuant to this Directive. The penalties thus provided for shall be effective,proportionate and dissuasive.Article9Transposition1.Member States shall bring into force the laws,regulations and administrative provisions necessary to comply with this Directive before13August2004.They shall immediately inform the Commission thereof.When Member States adopt those measures,they shall contain a reference to this Directive or be accompanied by such a refer-ence on the occasion of their official publication.The methods of making such a reference shall be laid down by the Member States.2.Member States shall communicate to the Commission the text of all laws,regulations and administrative provisions adopted in the field covered by this Directive.Article10Entry into forceThis Directive shall enter into force on the day of its publica-tion in the Official Journal of the European Union.Article11AddresseesThis Directive is addressed to the Member States.Done at Brussels,27January2003.For the European ParliamentThe PresidentP.COXFor the CouncilThe PresidentG.DRYSANNEXApplications of lead,mercury,cadmium and hexavalent chromium,which are exempted from the requirementsof Article4(1)1.Mercury in compact fluorescent lamps not exceeding5mg per lamp.2.Mercury in straight fluorescent lamps for general purposes not exceeding:—halophosphate10mg—triphosphate with normal lifetime5mg—triphosphate with long lifetime8mg.3.Mercury in straight fluorescent lamps for special purposes.4.Mercury in other lamps not specifically mentioned in this Annex.5.Lead in glass of cathode ray tubes,electronic components and fluorescent tubes.6.Lead as an alloying element in steel containing up to0,35%lead by weight,aluminium containing up to0,4%leadby weight and as a copper alloy containing up to4%lead by weight.7.—Lead in high melting temperature type solders(i.e.tin-lead solder alloys containing more than85%lead),—lead in solders for servers,storage and storage array systems(exemption granted until2010),—lead in solders for network infrastructure equipment for switching,signalling,transmission as well as network management for telecommunication,—lead in electronic ceramic parts(e.g.piezoelectronic devices).8.Cadmium plating except for applications banned under Directive91/338/EEC(1)amending Directive76/769/EEC(2)relating to restrictions on the marketing and use of certain dangerous substances and preparations.9.Hexavalent chromium as an anti-corrosion of the carbon steel cooling system in absorption refrigerators.10.Within the procedure referred to in Article7(2),the Commission shall evaluate the applications for:—Deca BDE,—mercury in straight fluorescent lamps for special purposes,—lead in solders for servers,storage and storage array systems,network infrastructure equipment for switching, signalling,transmission as well as network management for telecommunications(with a view to setting a specific time limit for this exemption),and—light bulbs,as a matter of priority in order to establish as soon as possible whether these items are to be amended accordingly.。

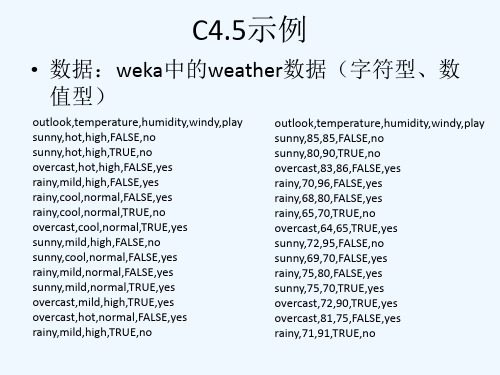

决策树C4.5算法总结

即选择outlook作为决策树的根节点时,信息增益为0.94-0.693=0.247,然后计算 outlook属性的熵,得增益比。同样方法计算当选择temperature、humidity、 windy作为根节点时系统的信息增益和属性熵,选择增益比最大的作为最终的根 节点。

选择节点分裂属性的问题

• ID3算法:使用信息增益作为选择节点分裂属性 的指标。增益准则的一个缺陷是它偏向于选择具 有更多取值的属性作为节点分裂属性。 • C4.5算法:使用信息增益率作为选择节点分裂属 性的指标,克服了ID3算法的缺点。

过拟合问题

• 过拟合:有监督的算法需要考虑泛化能力,在有限样本的 条件下,决策树超过一定规模后,训练错误率减小,但测 试错误率会增加。 • 剪枝:控制决策树规模的方法称为剪枝,一种是先剪枝, 一种是后剪枝。所谓先剪枝,实际上是控制决策树的生长; 后剪枝是指,对完全生成的决策树进行修剪。 • 先剪枝: 1) 数据划分法。划分数据成训练样本和测试样本,使用用训练 样本进行训练,使用测试样本进行树生长检验。 2) 阈值法。当某节点的信息增益小于某阈值时,停止树生长。 3) 信息增益的统计显著性分析。从已有节点获得的所有信息增 益统计其分布,如果继续生长得到的信息增 益与该分布相比 不显著,则停止树的生长。 优点:简单直接; 缺点:对于不回溯的贪婪算法,缺乏后效性考虑,可能导致树 提前停止。

UFI内部准则 ufi_internal_rules

UFIN ON-PROFIT ORGANIZATION GOVERNED BY THE LAW OF 1J ULY 1901*****Registered Office35 bis, rue Jouffroy-d’Abbans75017 PARISFrance*****UFI INTERNAL RULESJune 2010TABLE OF CONTENTSPageARTICLE1 : UFI NAME AND TAGLINE 3 ARTICLE2 : ADMISSION, MEMBER RIGHTS & OBLIGATIONS 5ARTICLE3 : UFI EVENT APPROVAL 6 ARTICLE4 : C ODE OF ETHICS 7 ARTICLE5 : ADMISSION FEES & SUBSCRIPTIONS 8ARTICLE 6 : ADMINISTRATION 9 ARTICLE7 : PROCEDURE FOR THE ELECTION OF THE INCOMING PRESIDENT 11ARTICLE8 : ASSOCIATIONS COMMITTEE 11ARTICLE9 : REGIONAL CHAPTERS 11 ARTICLE10 : WRITTEN BALLOTS 12 ARTICLE 11:MAJORITY REQUIRED FOR THE ELECTION 12ARTICLE12 : REGIONAL OFFICES 13 ARTICLE13 : COMMITTEES, WORKING GROUPS & TASK FORCES 13ARTICLE14:ORDINARY AND EXTRAORDINARY GENERAL ASSEMBLIES &ELECTIONS 14 ARTICLE15 : COSTS OF MEETINGS AND MISSIONS 14ARTICLE16 : LANGUAGES, SIMULTANEOUS TRANSLATION & DOCUMENTATION 15ARTICLE17 : UFI HONORARY FUNCTIONS AND DISTINCTIONS 15ARTICLE18 : C OMPLIMENTARY ACCESS FOR THE INCOMING PRESIDENT, THEPRESIDENT & THE OUTGOING PRESIDENT TO CERTAIN UFI EVENTS 15ARTICLE19 : INTERPRETATION OR SILENCE OF THE INTERNAL RULES 15NB: the word "Statutes" used in this document means "Articles of Association".ARTICLE 1. - UFI NAME AND TAGLINE (ARTICLE 3 OF THE STATUTES)Article 1.1. - Official name of the associationThe official name of the association is: UFI, The Global Association of the Exhibition Industry.This is a stand-alone name. The initials should not be translated. The name “Union des Foires Internationales” or its translation no longer exists.UFI is only to be written using Latin character fonts. UFI’s font is either Zurich or Arial. Pantone colours are olive #391 and blue #533.Example: UFI, The Global Association of the Exhibition Industry, has members worldwide.Article 1.2. - UFI Regional Chapter namesThe official names of the UFI Chapters are:•UFI Americas Chapter;•UFI Asia/Pacific (AP) Chapter;•UFI European Chapter;•UFI Middle East/Africa (MEA) Chapter.The logo including the text: “The Global Association of the Exhibition Industry” should not be used in conjunction with the Chapter name.The Chapter logo must only be written in English, using Latin character fonts.Article 1.3. - UFI logosUFI Association logoOnly the UFI Headquarters has the right to use the logo which includes the association’s name UFI and the tagline description.Upon written request, the UFI Headquarters may exceptionally authorize other uses of the association’s logo.UFI Regional Chapter Logos: No modification tothese logos is authorized. No member has the rightto use these logos without the formal and writtenconsent of the UFI Headquarters..UFI Member logo: Only UFI full members in thecategories of organizers, exhibition centres and fullmember associations outlined in article 5.1. of theStatutes are authorized to use this logo.On letterhead paper, the logo must be used in asmall format, on the top or bottom of the page, indirect connection with the company name. It shouldnot form part of the member organization’s logo.The UFI member logo is only to be written inEnglish, using Latin character fonts. UFI’s officialfont is either Arial or Zurich.The full name of UFI (UFI, The Global Associationof the Exhibition Industry) must not be incorporatedwith this logo.UFI associate members, would-be members andUFI approved events are not authorized to use thislogo.UFI Associate Member logo: UFI members in thecategory outlined in article 5.2. of the Statutes andwhich are not full members are authorized to usethis logo.The UFI Associate Member logo must be written inEnglish, using Latin character fonts. The full nameof UFI (UFI, The Global Association of theExhibition Industry) must not be incorporated withthis logo.A UFI Approved Event is not an associate member.UFI Approved Event logo: The UFI ApprovedEvent logo may only be applied to those memberevents which are recognised as having met the UFIquality criteria for international events as describedin article 3.1. hereafter.The UFI approved event logo must always appearin close proximity to the name of the specificapproved event, in order to differentiate from othernon UFI approved events.The UFI approved event logo must be written inEnglish, using Latin character fonts. UFI’s officialfont is either Arial or Zurich.Article 1.3.1. - UFI Logo Technical SpecificationsUFI has produced a PDF guide for the technical use of the UFI logos. This guide provides a summary of the different logos and technical specifications for UFI’s official colours, for specialist and internal printing, screen-based and web-based applications. Additional information is available from the UFI Headquarters.ARTICLE 2. - ADMISSION, MEMBER RIGHTS AND OBLIGATIONS (ARTICLE 6.2. OF THE STATUTES)Article 2.1. – Full member associationsOnly the President and Managing Director (or equivalent) of full member associations have access to UFI documentation and information. This includes the login and password for the members’ area of the UFI website.Article 2.2. - Associate membersArticle 2.2.1. - National associations and supporting organizations as outlined in Article 5.2. of the Statutes.Only the President and Managing Director (or equivalent) of these associations and organizations have access to UFI documentation and information. This includes the login and password for the members’ area of the UFI website.Article 2.2.2. - Partners of the exhibition industrya) Service providersService providers must prove that they or their head office have been providing services on an international level within the exhibition industry for at least three years. Service providers must abstain from active commercial activity during UFI events and meetings.b) AuditorsAuditors must be independent organizations authorized by UFI to carry out the audit of exhibition statistics for a new UFI Approved Event request, or to maintain UFI Approved Event status. The auditors must conduct the audits of all UFI Approved Events in accordance with UFI’s Auditing Rules and by completing the UFI Standard Audit Certificate (in English).c) Universities and other educational bodiesUniversities and other educational bodies can join UFI if and when they have developed an education programme which is supported or endorsed by UFI, or if they have specific activities(e.g. research) within the exhibition industry. As members of UFI, they must cooperate with UFIon a regular basis.Article 2.3. - Supporting lettersThe supporting letters must specify that the applicant:•is a trade far/exhibition organizer, an exhibition centre, an association (international or national),a supporting organization/association or a partner of the exhibition industry;•is recognized as being competent and is appreciated for the quality of their work on an international level;•can be recommended for UFI membership, justifying the reasons.Article 2.4. - Admission procedure (for all membership categories)Membership applications must be submitted to the UFI Headquarters, who reports to the Membership Committee. The latter may request further information from the applicant.Incomplete applications will not be examined.Upon the recommendation of the Membership Committee, the Executive Committee approves the membership application. The membership becomes effective immediately following the Executive Committee’s approval.At the UFI Membership Committee’s request, an investigator may be designated, in principle from outside the applicant’s country, to conduct an inspection visit of the applicant’s services and/or installations. The applicant reimburses UFI for the investigator’s hotel and travel expenses (business or similar), even if the UFI Executive Committee subsequently rejects the admission(s). The investigator verifies the accuracy of all the information provided by the applicant, whilst taking into account the economic structure of the country. He establishes a report of his observations and submits it to the Membership Committee.Article 2.5. - Changes after the admissionAll major changes in the situation of a UFI member and/or an UFI approved event must be immediately communicated to the UFI Headquarters by the member in question.ARTICLE 3. - UFI EVENT APPROVALArticle 3.1. - Conditions to be fulfilled for UFI approved event statusUFI event approval can only be requested by UFI member organizers or applicants for membership in the organizer category.These events must meet the criteria below.•They must be "international" according to one of the following requirements:•the number of direct foreign exhibitors must be at least 10% of the totalnumber of exhibitors;•the number of foreign visits or visitors must represent at least 5% of thetotal number of visits or visitors, respectively. For public fairs, thispercentage is to be counted on the basis of professional visits or visitors,if they are identified.•Audited statistics must be provided regarding the total net exhibition space and the number of domestic and international exhibitors as well as for visits or visitors, as the case may be, in accordance with the decision of the UFI Membership Committee, and in conformity with “UFI’s Auditing Rules for the Statistics of UFI Approved Events”. This document includes the definitions and counting methods for exhibitors, visitors and visits.These statistical data must be objectively confirmed by a specialized audit organization, by an independent audit company or by a certified accountant who has obtained prior approval from UFI to conduct the audit. At a minimum every other edition of the event must be audited, except for the events which take place once every three years, or less frequently. For these events, each edition must be audited. The only exception is for events which have been audited for the first time in order to obtain UFI Approved Event status. In this case the next edition must also be audited.•They must have taken place twice as an international exhibition at the moment of the application.•The event should occur in appropriate permanent installations and provide users with all the services they may require, notably reception, assistance and information services for exhibitors and international visitors. Application forms, advertising material and the fair catalogue should be published not only in the country's language, but also in at least one other foreign language, preferably English.•The event should have a regular schedule and duration which does not exceed three weeks.Article 3.2. - Exceptions from these requirementsIn view of the wide variety of exhibitions, notably due to the geopolitical situation or the nature of the exhibits, exceptions may be made upon the UFI Membership Committee's recommendation for event that do not exactly meet the above mentioned arithmetical criteria.Article 3.3. - Procedure of event approvalThe UFI approved event request form is available upon request from the UFI Headquarters, who reports to the UFI Membership Committee. The UFI Membership Committee may request further information about the event.At the UFI Membership Committee’s request, an investigator may be designated, in principle from outside the member organizer's country, who will visit the member organizer and the event.The Membership Committee will report to the UFI Executive Committee for the final decision. The approval becomes effective immediately following the decision of the Executive Committee.Article 3.4. - Change of organizer of a UFI approved eventThe UFI approved event status is not transferable without prior and written agreement by the UFI Executive Committee.If the new organizer is not a UFI member, he must apply for membership, making a UFI event approval request for the event in question. See article 3.1. of these Internal Rules.Article 3.5. - Joint-venture eventsUFI accepts joint venture events wherein an exhibition is organized by two or more organizers. The majority organizer is considered to be the representative of the event.The joint venture partner applying for UFI event approval must clearly specify in the UFI approved event request form the name of each partner and their degree of participation in the event. The subscription will be invoiced to the majority organizer of the event.Article 3.6. - Upholding of the UFI approved event statusTo maintain UFI approved event status, member organizers must provide audit certificates for their UFI approved events. The frequency of these audits is outlined in article 3.1. above.An event which does not satisfy the criteria outlined in article 3.1. above will automatically lose its UFI approved event status.ARTICLE 4. - CODE OF ETHICS (ARTICLE 6.1. of the STATUTES)All UFI members undertake to uphold the principles of respect, integrity, responsibility and professionalism in the conduct of their business and in their contacts with clients and colleagues. These principles form the basis of the UFI Code of Ethics to which each UFI member adheres.As a UFI member:•we believe that a commitment to ethical conduct is a constructive approach to successfully achieving our professional goals.•we will conduct professional activities in accordance with accepted standards, and applicable laws and regulations.•we will respect UFI’s Statutes, Internal Rules and all obligations arising from membership.•we will provide accurate, reliable information concerning our activities and commitments, notably in terms of exhibition statistics and use this information in all our communication material.•we will write contracts in such a fashion that they are clear and fair and honour them accordingly.•we will recommend service suppliers who are professionally sound and who are in compliance with recognised standards of health, safety and environment.•we agree to respect the intellectual property of others and to protect the confidentiality of privileged information provided to us during business activities.•we will support the practice of sustainable development within our industry.•we will strive to continually improve the level of our professional competence and ability.•we will support the organization’s activities as it promotes, serves and represents the exhibition industry.ARTICLE 5. - ADMISSION FEES AND SUBSCRIPTIONSUFI's financial year runs from 1 July to 30 June; all invoiced subscriptions refer to this period. The UFI admission fees and subscriptions are fixed annually by the General Assembly. All details relating to the UFI admission fees and subscriptions are available from the UFI Headquarters.The subscriptions must be settled on receipt of UFI's invoice. The French VAT is payable in addition to all fees and subscriptions (the current rate is 19.6%). The procedure to claim back this VAT is available from the UFI Headquarters.When the admission of a member is granted in the course of a year, a pro-rata subscription is invoiced.For groups or companies who wish to join UFI with their subsidiaries worldwide (as outlined in Article 5.1.3. of the Statutes), the UFI Executive Committee is entitled to make special agreements. If certain subsidiaries wish to remain separate UFI members, they must pay their own subscription.Article 5.1. - Admission feesAll UFI full members, with the exception of the associations (as outlined in Article 5.1.4. of the Statutes), pay an admission fee on a one-time basis.All UFI associate members, except those associations and supporting organizations (as outlined in Article 5.2.1. of the Statutes) pay an admission fee on a one-time basis.Article 5.2. - SubscriptionsArticle 5.2.1. - OrganizersThe total fee for these members is calculated according to:a) total net rented exhibition space of all the events organized during the previous calendar yearwhether or not these events are approved by UFI. One third of the net outdoor exhibition space is taken into account.b) The fee calculated in a) above includes one UFI approved event. A supplement is due for eachadditional UFI approved event, whether they have taken place during that year or not.If the global subscription of the organizer for the year in question has reached the maximum subscription level, no supplement is due. The minimum fee is due if no events are organized (UFI approved event or not) during the previous calendar year.The organizer members must provide the UFI Headquarters with the information required for the calculation of their subscription and within the specified deadline.Article 5.2.2. - Exhibition CentresThe total fee for these members is calculated according to:a) the total gross exhibition venue space of all the exhibition centres operated by the member.One third of the net outdoor exhibition space is taken into account.b) the fee calculated in a) above includes one exhibition centre. If the member operates severalexhibition centres, a supplement is due for each of the additional centres.There is a minimum and maximum subscription.Article 5.2.3. Organizers and Exhibition CentresOrganizers and operators of exhibition centres must pay the subscriptions applicable to both categories, but at a reduced rate.The exhibition centre members must provide the UFI Headquarters with the information required for the calculation of their subscription and within the specified deadline.Article 5.2.4. - GroupsA fixed amount is due if a member has group status, in addition to the subscription as an organizer and/or exhibition centre.Article 5.2.5. - AssociationsAssociations pay a subscription based on their annual budget and the number of employees.Article 5.2.6. Associate membersThe subscription for associate members is based on their activity and their size.Article 5.2.7. - Would-be members"Would-be members" pay the same subscription as full members. The admission fee is payable when full membership status is granted.ARTICLE 6. – ADMINISTRATION (ARTICLE 11 OF THE STATUTES)Article 6.1. – Board of DirectorsArticle 6.1.1. - Conditions for the allocation of the 47 seats of the elected members of the Board of DirectorsThe classification of countries by geographical zone and the representation of those countries within each zone are based on the subscriptions paid by the organizer and exhibition centre members of the country or chapter, during the financial year preceding the election.The maximum of 47 seats are allocated to the representatives of the organizer and exhibition centre members as follows:• a maximum of 24 seats are distributed among the most important countries which together represent at least 50% of the subscriptions paid by organizer and exhibition centre members. These seats are named “fixed seats”. Their allocation is in proportion to the volume of the subscriptions paid by each of these countries.Each beneficiary country has a minimum of two and a maximum of five fixed seats.•The remaining seats are distributed among the Chapters, in proportion to the volume of the subscriptions from each Chapter, after deduction of the subscriptions from the countries already provided with fixed seats. These seats are named “seats in competition”. Each beneficiary country is entitled to a maximum of two seats in competition.The seats in competition are allocated through an election within each Regional Chapter.The members of the countries to which no fixed seats have been allocated participate in this election, as follows below.Article 6.1.2. - Election procedures for the 47 elected members of the Board of Directors - CandidaciesDuring the election year, the election of the Board of Directors must have taken place in due time for the composition of the new Board to be made known at the meeting of the General Assembly.UFI must receive the candidacies in writing (by post, fax or e-mail) before the specified date.Representatives of the organizer and exhibition centre members can be candidates even if they are members of the Board of Directors as a Chapter Chairman, or as the Chairman or Vice-Chairman of the Associations' Committee (articles 14 and 15 of the Statutes).Candidacies are admissible only when the member concerned has paid its subscriptions.The Executive Committee retains the right to refuse the candidacy of an outgoing member of the Board if they have not personally attended one third of the meetings during their mandate.Article 6.1.3. - Board of Directors' meetingsThe convocation to a Board meeting must be accompanied by the agenda and sent by the UFI Headquarters at least fifteen days prior to the date of the meeting. As far as possible, the Board schedules the location and the date of the following meeting at the end of each meeting.The President may invite another UFI member or an external specialist in an advisory capacity, if the agenda of the meeting includes an item in which he is particularly competent.The presence of participants from the UFI Headquarters, except the UFI Managing Director, is subject to prior approval by the UFI President and the Managing Director.Article 6.1.4. - Proxies (article 11.1.5. of the Statutes)Proxies are only valid if the UFI Headquarters have been informed in writing at least three days before the meeting.Article 6.1.5. - Voting conditions for the Board of DirectorsEach Board member has one vote.The Board of Directors normally votes by show of hands, except in the case of an election which requires a secret ballot.The above exception may also apply to any decision upon the request of the President or a member of the Board of Directors.All decisions are taken by the absolute majority of votes cast; in the event of the votes being equal, the Chairman of the meeting has the deciding vote.Article 6.2. – UFI Executive CommitteeArticle 6.2.1. - Election onto the Executive CommitteeThe elected Executive Committee members outlined in Article 11.2.1. of the Statutes, are elected by secret ballot by a majority vote of the Board of Directors. The candidacies are presented by the President.In the case of vacancy during the term of office, the Executive Committee proposes to the Board of Directors a candidate for the vacant seat.Article 6.2.2. - Executive Committee MeetingsThe President may invite another UFI member or an external specialist in an advisory capacity, if the agenda of the meeting includes an item in which he is particularly competent.ARTICLE 7. - PROCEDURE OF ELECTION OF THE UFI INCOMING PRESIDENTThe UFI Incoming President is elected if he obtains the absolute majority of votes cast in the first or second ballot. If there are several candidates, and if none of them obtain a majority in the first ballot, a second ballot will take place between the two candidates who obtained the largest number of votes in the first ballot.ARTICLE 8.- ASSOCIATIONS' COMMITTEE (ARTICLE 14. OF THE STATUTES)Only the representatives of full member associations are eligible for election as Chairman or Vice-Chairman of this Committee. The Chairman and Vice-Chairman must come from different countries. The election of the Chairman and Vice-Chairman takes place every three years, before the UFI General Assembly. The Chairman can be re-elected once to assume office immediately after the end of his current mandate. After an interruption, former Chairmen may be elected again.ARTICLE 9. - REGIONAL CHAPTERS (ARTICLE 15. OF THE STATUTES)Article 9.1. - Role of the Regional ChaptersThe main role of the Regional Chapter includes:•discussing specific problems and ideas concerning the region;•encouraging collaboration between members in the region;•increasing professionalism among members through UFI's educational programmes; •assisting and educating new members concerning their responsibilities within UFI; •suggesting subjects of interest to the Board of Directors;•promoting UFI in the region and encouraging new organizations to join UFI;•advising the Managing Director on membership matters;•advising the Managing Director and the Regional Manager on activities within the region.Article 9.2. - Chairmanship and Vice-ChairmanshipOnly representatives from full members are eligible for election as Chairman or Vice-Chairman. The Chairman and Vice-Chairmen must come from different countries. The elections of the Chairmen and Vice-Chairmen take place every three years, at the latest at the last meeting preceding the UFI General Assembly.These elections can also be held by written ballot, in conformity with article 10.2. of the Internal Rules. The Chairman can be re-elected once to assume office immediately after the end of his current mandate. After an interruption, former Chairmen may be elected again.The Chairmen and Vice-Chairmen of the Regional Chapters are elected by the members situated in the region concerned, with the same voting rights as for the General Assembly, as described in article 16. of the Statutes.ARTICLE 10. – WRITTEN BALLOTSArticle 10.1. Written ballots for electionsThe election:•of the Chairmen and Vice-Chairmen of the Regional Chapters;•of the Chairman and Vice-Chairman of the Associations’ Committee;•of the 47 elected members of the Board of Directorsmay be held by written ballot (by letter, fax or email) at the initiative of the UFI President. The voting rights for the General Assemblies (outlined in Article 15) apply.In this case, UFI contacts in writing all the members concerned by the election at least 15 days before the date of the ballot mentioning:•the reason for the ballot;•the deadline date for the receipt of ballot papers;•the ballot paper indicating:o the address, the fax number and the email address for the response;o the name of the voting organization with the number of votes;o the name of each candidate.UFI can designate a third party to guarantee the confidentially for the receipt and counting of the votes.Article 10.2. - Written ballot for the modification of the Internal RulesOn the President’s initiative, the modification of the Internal Rules can be decided by the Board of Directors through a written ballot (by letter, fax or email).In this case, UFI contacts in writing the members of the Board of Directors at least 15 days before the date of the ballot mentioning:•the reason for the ballot;•the deadline date for the receipt of ballot papers;•the article(s) of the Internal Rules to be modified (original version);•the proposed modifications to the articles;•the ballot paper indicating:o the address, the fax number and the email address for the response;o the name of the Board member;oARTICLE 11.- MAJORITY REQUIRED FOR THE ELECTION OF THE PERSONS OUTLINED IN ARTICLE 10.1. ABOVEArticle 11.1. Election of the Chairmen and Vice-Chairmen of the Regional Chapters and the Associations’ CommitteeThe ballot is based on the absolute majority of the votes cast. If none of the candidates obtain this majority, a second ballot will be organized between the two candidates with the most votes.If the two candidates obtain an equal number of votes cast, the most senior within UFI wins the election.。

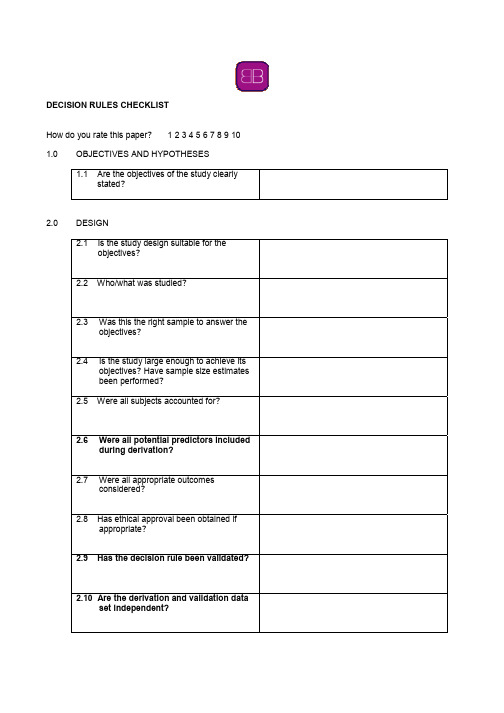

DECISIONRULESCHECKLIST:决策规则表

DECISION RULES CHECKLISTHow do you rate this paper? 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1.0OBJECTIVES AND HYPOTHESES1.1 Are the objectives of the study clearlystated?2.0DESIGN2.1 Is the study design suitable for theobjectives?2.2 Who/what was studied?2.3 Was this the right sample to answer theobjectives?2.4 Is the study large enough to achieve itsobjectives? Have sample size estimatesbeen performed?2.5 Were all subjects accounted for?2.6 Were all potential predictors includedduring derivation?2.7 Were all appropriate outcomesconsidered?2.8 Has ethical approval been obtained ifappropriate?2.9 Has the decision rule been validated?2.10 Are the derivation and validation dataset independent?3.0MEASUREMENT AND OBSERVATION3.1 Is it clear what was measured, how it wasmeasured and what the outcomes were?3.2 Are the measurements valid?3.3 Are the measurements reliable?3.4 Are the measurements reproducible?4.0PRESENTATION OF RESULTS4.1 Are the basic data adequately described?4.2 Are the results presented clearly,objectively and in sufficient detail toenable readers to make their ownjudgement?4.3 Are the results internally consistent, i.e.do the numbers add up properly?5.0ANALYSIS5.1 Are the data suitable for analysis?5.2 Are the methods appropriate to the data?5.3 Are any statistics correctly performed andinterpreted?6.0DISCUSSION6.1 Are the results discussed in relation toexisting knowledge on the subject andstudy objectives?6.2 Is the discussion biased?7.0INTERPRETATION7.1 Are the authors’ conclusions justified bythe data?7.2 What level of evidence has this paperpresented? (using CEBM levels)7.3 Does this paper help me answer myproblem?How do you rate this paper now? 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10In addition, answer the following questions with regards to local practice.8.0IMPLEMENTATION8.1 Can any necessary change beimplemented in practice?8.2 What aids to implementation exist?8.3 What barriers to implementation exist?。

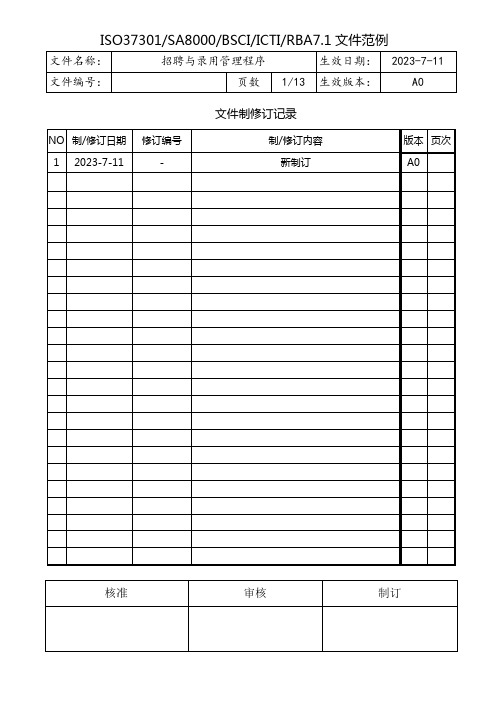

招聘与录用管理程序(中英文)

文件制修订记录招聘与录用管理办法Recruitment and employment management approach1. 目的 Purpose为规范公司对招聘工作的管理,树立良好企业形象,吸引更多德才兼备的人才加盟公司,特制定本办法。

To standard company’s recruitment management and build up a good company image, attract more talented and virtuous person to join in the company2. 范围 Scope本公司所有员工的招聘与录用均适用。

This measure is applicable for all employees’ recruitment and employment 3. 定义:Defination童工:指年龄未满16周岁劳动者Child labor: refers to any person under the age of 16未成年工:指年满16周岁,未满18周岁的劳动者Minor worker: refers to any person over 16 but under 18 year old.4. 权责 Responsibility4.1各课主管/经理 Dept. Supervisor/Manager4.1.1负责根据公司未来发展需要及本部门现有人力状况,制定年度招聘计划;Responsible for set out yearly recruitment plan according to company future development and department current status.4.1.2负责填写<<人员增(补)申请表>>;Responsible for fill the <<staff added(supplement) application form>>4.1.3负责对应聘人员身份信息、技能资格审核,人员录用决策。

IECEx 系统参与与系统费用(第7版)说明书