An Overview of Translation in China

中国文化英语教程翻译

中国文化英语教程翻译Title: Translation of Chinese Cultural English TutorialIntroduction:In recent years, there has been a growing interest in Chinese language and culture worldwide. As a result, there is a demand for English-language materials that introduce the rich and fascinating aspects of Chinese culture. This document aims to provide a comprehensive translation of a Chinese cultural English tutorial, covering various facets of Chinese culture from history and philosophy to traditional arts and customs.I. Chinese History: A Cultural SagaChina has an extensive history that spans thousands of years. This section of the tutorial delves into important periods such as the ancient dynasties, the influential Tang and Song dynasties, and the modern era. It highlights key historical figures, significant events, and the impact of Chinese history on present-day society.II. Philosophical Traditions: Taoism, Confucianism, and BuddhismThe tutorial outlines the three major philosophical traditions that have profoundly shaped Chinese culture: Taoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism. It explores their core beliefs, practices, and their enduring influence on Chinese society, ethics, and values.III. Chinese Festivals and CustomsChinese festivals are an integral part of Chinese culture, celebrated with great enthusiasm and joy. This section provides an overview of major Chinese festivals, including Spring Festival (Chinese New Year), Lantern Festival, Dragon Boat Festival, Mid-Autumn Festival, and Double Ninth Festival. It explains the customs, rituals, and symbolism associated with each festival, providing readers with a deeper understanding of the cultural significance of these celebrations.IV. Traditional Chinese Arts: Calligraphy, Painting, and MusicChinese calligraphy, painting, and music have a long history and are highly regarded as significant art forms. This chapter explores the techniques, styles, and themes of traditional Chinese calligraphy and painting. Additionally, it introduces readers to traditional Chinese musical instruments and the distinctive melodies that emanate from them.V. Chinese Cuisine: A Culinary AdventureChinese cuisine is renowned for its diverse flavors, regional specialties, and unique cooking techniques. This section takes readers on a gastronomical journey, showcasing the famous eight culinary traditions, such as Cantonese, Sichuan, and Shandong cuisines. It provides an overview of staple ingredients, cooking methods, and popular dishes, giving readers a taste of the Chinese food culture.VI. Traditional Chinese Medicine: Balancing Health and HarmonyTraditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is deeply rooted in Chinese culture and emphasizes a holistic approach to health and well-being. This chapter discusses the principles of TCM, including acupuncture, herbal remedies, and the concept ofyin and yang. It explores the ancient wisdom and practices that continue to be relevant today.Conclusion:The English translation of this Chinese cultural tutorial aims to bridge the gap between the English-speaking world and the rich heritage of Chinese culture. It offers readers an in-depth understanding of Chinese history, philosophy, festivals, arts, cuisine, and medicine. This resource serves as a valuable tool for promoting cross-cultural understanding and appreciation, as well as fostering cultural exchange between China and the English-speaking world.。

The history of translation in China,中国翻译史介绍

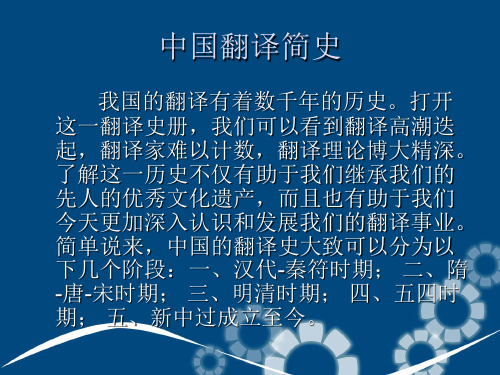

我国的翻译有着数千年的历史。打开 这一翻译史册,我们可以看到翻译高潮迭 起,翻译家难以计数,翻译理论博大精深。 了解这一历史不仅有助于我们继承我们的 先人的优秀文化遗产,而且也有助于我们 今天更加深入认识和发展我们的翻译事业。 简单说来,中国的翻译史大致可以分为以 下几个阶段:一、汉代-秦符时期; 二、隋 -唐-宋时期; 三、明清时期; 四、五四时 期; 五、新中过成立至今。

二、隋-唐-宋时代

从隋代(公元五九0年)到唐代,这段时间是我国翻译事业高度 发达时期。隋代历史较短,译者和译作都很少。比较有名的翻译家 有释彦琮(俗姓李,赵郡柏人)。他是译经史上第一位中国僧人。 一生翻译了佛经23部100余卷。彦琮在他撰写的《辨证论》中总结翻 译经验,提出了作好佛经翻译的八项条件:1)诚心受法,志愿益人, 不惮久时(诚心热爱佛法,立志帮助别人,不怕费时长久);2)将 践觉场,先牢戒足,不染讥恶(品行端正,忠实可信,不惹旁人讥 疑);3)荃晓三藏,义贯两乘,不苦闇滞(博览经典,通达义旨。 不存在暗昧疑难的问题);4)旁涉坟史,工缀典词,不过鲁拙(涉 猎中国经史,兼擅文学,不要过于疏拙);5)襟抱平恕。器量虚融, 不好专执(度量宽和,虚心求益,不可武断固执);6)耽于道术, 淡于名利,不欲高炫(深爱道术,淡于名利,不想出风头);7)要 识梵言,乃闲正译,不坠彼学(精通梵文,熟悉正确的翻译方法, 不失梵文所载的义理);8)薄阅苍雅,粗谙篆隶。不昧此文(兼通 中训诂之学,不使译本文字欠准确)。

彦琮还说,"八者备矣,方是得人".这八条说的是译者的修养问题,至今 仍有参考价值。在彦琮以后,出现了我国古代翻译界的巨星玄奘(俗称三藏 法师)。他和上述鸠摩罗什、真谛一起号称华夏三大翻译家。玄奘在唐太宗 贞观二年(公元六二八年)从长安出发去印度取经,十七年后才回国。他带 回佛经六百五十七部,主持了中国古代史上规模最大、组织最为健全的译场, 在十九年间译出了七十五部佛经,共一三三五卷。玄奘不仅将梵文译成汉语, 而且还将老子著作的一部分译成梵文,是第一个将汉语著作向外国人介绍的 中国人。玄奘所主持的译场在组织方面更为健全。据《宋高僧传》记载,唐 代的翻译职司多至11种:1)译主,为全场主脑,精通梵文,深广佛理。遇有 疑难,能判断解决;2)证义,为译主的助手,凡已译的意义与梵文有和差殊, 均由他和译主商讨;3)证文,或称证梵本,译主诵梵文时,由他注意原文有 无讹误;4)度语,根据梵文文字音改记成汉字,又称书字;5)笔受,把录 下来的梵文字音译成汉文;6)缀文,整理译文,使之符合汉语习惯;7)参 译,既校勘原文是否有误,又用译文回证原文有无歧异;8)刊定,因中外文 体不同,故每行每节须去其芜冗重复;9)润文,从修辞上对译文加以润饰; 10)梵呗,译文完成后,用梵文读音的法子来念唱,看音调是否协调,便于 僧侣诵读;11)监护大使,钦命大臣监阅译经。

中国翻译史(英文版 详细)

Brief Introduction of the Chinese Translation HistoryChinese translation theory was born out of contact with vassal states during the Zhou Dynasty. It developed through translations of Buddhist scripture into Chinese. It is a response to the universals of the experience of translation and to the specifics of the experience of translating from specific source languages into Chinese. It also developed in the context of Chinese literary and intellectual tradition.The modern Standard Mandarin word fanyi翻譯"translate; translation" compounds fan "turn over; cross over; translate" and yi "translate; interpret". Some related synonyms are tongyi通譯"interpret; translate", chuanyi傳譯"interpret; translate", and zhuanyi轉譯"translate; retranslate".The Chinese classics contain various words meaning "interpreter; translator", for instance, sheren舌人(lit. "tongue person") and fanshe反舌(lit. "return tongue"). The Classic of Rites records four regional words: ji寄"send; entrust; rely on" for Dongyi 東夷"Eastern Yi-barbarians", xiang象"be like; resemble; image" for Nanman 南蠻"Southern Man-barbarians", didi狄鞮"Di-barbarian boots" for Xirong 西戎"WesternRong-barbarians", and yi譯"translate; interpret" for Beidi 北狄"Northern Di-barbarians".In those five regions, the languages of the people were not mutually intelligible, and their likings and desires were different. To make what was in their minds apprehended, and to communicate their likings and desires, (there were officers), — in the east, called transmitters; in the south, representationists; in the west, Tî-tîs; and in the north, interpreters. (王制"The Royal Regulations", tr. James Legge 1885 vol. 27, pp. 229-230)A Western Han work attributes a dialogue about translation to Confucius. Confucius advises a ruler who wishes to learn foreign languages not to bother. Confucius tells the ruler to focus on governance and let the translators handle translation.The earliest bit of translation theory may be the phrase "names should follow their bearers, while things should follow China." In other words, names should be transliterated, while things should be translated by meaning.In the late Qing Dynasty and the Republican Period, reformers such as Liang Qichao, Hu Shi and Zhou Zuoren began looking at translation practice and theory of the great translators in Chinese history.Zhi Qian (3rd c. AD)Zhi Qian (支謙)'s preface (序) is the first work whose purpose is to express an opinion about translation practice. The preface was included in a work of the Liang Dynasty. It recounts an historical anecdote of 224AD, at the beginning of the Three Kingdoms period. A party of Buddhist monks came to Wuchang. One of them, Zhu Jiangyan by name, was asked to translate some passage from scripture. He did so, in rough Chinese. When Zhi Qian questioned the lack of elegance, another monk, named Wei Qi (維衹), responded that the meaning of the Buddha should be translated simply, without loss, in an easy-to-understand manner: literary adornment is unnecessary. All present concurred and quoted two traditional maxims: Laozi's "beautiful words are untrue, true words are not beautiful" and Confucius's "speech cannot be fully recorded by writing, and speech cannot fully capture meaning".Zhi Qian's own translations of Buddhist texts are elegant and literary, so the "direct translation" advocated in the anecdote is likely Wei Qi's position, not Zhi Qian's.Dao An (314-385AD)Dao An focused on loss in translation. His theory is the Five Forms of Loss (五失本):1.Changing the word order. Sanskrit word order is free with a tendency to SOV. Chinese is SVO.2.Adding literary embellishment where the original is in plain style.3.Eliminating repetitiveness in argumentation and panegyric (頌文).4.Cutting the concluding summary section (義說).5.Cutting the recapitulative material in introductory section.Dao An criticized other translators for loss in translation, asking: how they would feel if a translator cut the boring bits out of classics like the Shi Jing or the Classic of History?He also expanded upon the difficulty of translation, with his theory of the Three Difficulties (三不易):municating the Dharma to a different audience from the one the Buddha addressed.2.Translating the words of a saint.3.Translating texts which have been painstakingly composed by generations of disciples.Kumarajiva (344-413AD)Kumarajiva’s translation practice was to translate for meaning. The story goes that one day Kumarajiva criticized his disciple Sengrui for translating “heaven sees man, and man sees heaven” (天見人,人見天). Kumarajiva felt that “man and heaven connect, the two able to see each other” (人天交接,兩得相見) would be more idiomatic, though heaven sees man, man sees heaven is perfectly idiomatic.In another tale, Kumarajiva discusses the problem of translating incantations at the end of sutras. In the original there is attention to aesthetics, but the sense of beauty and the literary form (dependent on the particularities of Sanskrit) are lost in translation. It is like chewing up rice and feeding it to people (嚼飯與人).Huiyuan (334-416AD)Huiyuan's theory of translation is middling, in a positive sense. It is a synthesis that avoids extremes of elegant (文雅) and plain (質樸). With elegant translation, "the language goes beyond the meaning" (文過其意) of the original. With plain translation, "the thought surpasses the wording" (理勝其辭). For Huiyuan, "the words should not harm the meaning" (文不害意). A good translator should “strive to preserve the original” (務存其本).Sengrui (371-438AD)Sengrui investigated problems in translating the names of things. This is of course an important traditional concern whose locus classicus is the Confucian exhortation to “rectify names” (正名). This is not merely of academic concern to Sengrui, for poor translation imperils Buddhism. Sengrui was critical of his teacher Kumarajiva's casualapproach to translating names, attributing it to Kumarajiva's lack of familiarity with the Chinese tradition of linking names to essences (名實).Sengyou (445-518AD)Much of the early material of earlier translators was gathered by Sengyou and would have been lost but for him. Sengyou’s approach to translation resembles Huiyuan's, in that both saw good translation as the middle way between elegance and plainness. However, unlike Huiyuan Sengyou expressed admiration for Kumarajiva’s elegant translations.Xuanzang (600-664AD)Xuanzang’s theory is the Five Untranslatables (五種不翻), or five instances where one should transliterate:1.Secrets: Dharani 陀羅尼, Sanskrit ritual speech or incantations, which includes mantras.2.Polysemy: bhaga (as in the Bhagavad Gita) 薄伽, which means comfortable, flourishing, dignity,name, lucky, esteemed.3.None in China: jambu tree 閻浮樹, which does not grow in China.4.Deference to the past: the translation for anuttara-samyak-sambodhi is already established asAnouputi 阿耨菩提.5.To inspire respect and righteousness: Prajna 般若instead of “wisdom” (智慧).Daoxuan (596-667AD)Yan Fu (1898)Yan Fu is famous for his theory of fidelity, clarity and elegance (信達雅), which some believe originated with Tytler. Yan Fu wrote that fidelity is difficult to begin with. Only once the translator has achieved fidelity and clarity should he attend to elegance. The obvious criticism of this theory is that it implies that inelegant originals should be translated elegantly. Clearly, if the style of the original is not elegant or refined, the style of the translation should not be elegant either.Liang Qichao (1920)Liang Qichao put these three qualities of a translation in the same order, fidelity first, then clarity, and only then elegance.Lin Yutang (1933)Lin Yutang stressed the responsibility of the translator to the original, to the reader, and to art. To fulfill this responsibility, the translator needs to meet standards of fidelity (忠實), smoothness (通順) and beauty.Lu Xun (1935)Lu Xun's most famous dictim relating to translation is "I'd rather be faithful than smooth" (寧信而不順).Ai Siqi (1937)Ai Siqi described the relationships between fidelity, clarity and elegance in terms of Western ontology, where clarity and elegance are to fidelity as qualities are to being.Zhou Zuoren (1944)Zhou Zuoren assigned weightings, 50% of translation is fidelity, 30% is clarity, and 20% elegance.Zhu Guangqian (1944)Zhu Guangqian wrote that fidelity in translation is the root which you can strive to approach but never reach. This formulation perhaps invokes the traditional idea of returning to the root in Daoist philosophy.Fu Lei (1951)Fu Lei held that translation is like painting: what is essential is not formal resemblance but rather spiritual resemblance (神似).Qian Zhongshu (1964)Qian Zhongshu wrote that the highest standard of translation is transformation (化, the power of transformation in nature): bodies are sloughed off, but the spirit (精神), appearance and manner (姿致) are the same as before (故我, the old me or the old self).An Overview of Translation in China:Practice and Theoryby Weihe ZhongAbstract: This paper provides a chronological review of both translation practice and theory in China. Translation has a 3000-year long history in China and it was instrumental in the development of the Chinese national culture. This paper deals with translation in ancient time (1100 BC-17th century), the contemporary time (18th century-late 20th century), the modern time (1911-1978) and present-day China (1978). The major characteristics of translation practice and contributions of major translation theories are highlighted.Keywords: translation, history, China,1. Introductionranslation has been crucial to the introduction of western learning and the making of national culture in China. China has an over five thousand-year long history of human civilization and a three thousand-year history of translation. This paper is to provide a chronological review highlighting translation theory and practice in China from ancient to present times.2. Translation Practice and Theory in Ancient China2.1. Early Translation in ChinaThe earliest translation activities in China date back to the Zhou dynasty (1100.BC). Documents of the time indicated that translation was carried out by government clerks, who were concerned primarily with the transmission of ideologies. In a written document from late Zhou dynasty, Jia Gongyan, an imperial scholar, defined translation as: "translation is to replace one written language with another without changing the meaning for mutual understanding."1 This definition of translation, although primitive, proves the existence of translation theory in the ancient China. People tended to sum up the principles identified following his translation practice.China has an over five thousand-year long history of human civilization and a three thousand-year history of translation.It was during the Han dynasty (206 BC - 220 BC) that translation became a medium for the dissemination of foreign learning. Buddhism, which originated in India and was unknown outside that country for a very long time began to penetrate China toward the middle of the first century. Therefore, the Buddhist scriptures which were written in Sanskrit needed to be translated into Chinese to meet the need of Chinese Buddhists.An Shigao, a Persian, translated some Sutras (Buddhist Precepts in Sanskrit) into Chinese, and at the same time introduced Indian astronomy to China. Another translator of the same period was Zhi Qian, who translated about thirty volumes of Buddhist scriptures in a literal manner. His translation was hard to understand because of the extremely literal translation. And it might be in this period of time trhat there was discussion on literal translation vs free translation—"a core issue of translation theory." 2In the fifth century, translation of Buddhist scripture was officially organized on a large scale in China. A State Translation School was founded for this purpose. An imperial officer—Dao An was appointed director of this earliest School of Translation in China. Dao An advocated strict literal translation of the Buddhist scriptures, because he himself didn't know any Sanskrit. He also invited the famous Indian Buddhist monk Kumarajiva (350-410), who was born in Kashmir, to translate and direct the translation of Buddhist scriptures in his translation school. Kumarajiva, after a thorough textual research on the former translation of Sanskrit sutras, carried out a great reform of the principles and methods for the translation of sutras. He emphasized the accuracy of translation. Therefore, he applied a free translation approach to transfer the true essence of the Sanskrit Sutras. He was the first person in the history of translation in China to suggest that translators should sign their names to the translated works. Kumarajiva himself translated a large number of Sanskrit Sutras. His arrival in China made the translation school flourish and his translations enabled Buddhism to take root as a serious rival to Taoism. From the time of Kumarajiva until the eighth century, the quantity of translations of Sanskrit Sutras increased and their accuracy improved.The period from the middle of the first century to the fifth century is categorized as the early stage of translation in China. In this stage, translation practice was mainly of religious scriptures. The core issue in translation theory raised was: literal translation vs free translation."Accuracy and smoothness" were taken as criteria for guiding the translation of Buddhist scriptures. This may be considered both primitive translation theory in China, and also the basis of modern translation theory in China.2 2. The First Peak of Translation in ChinaThe translation and importation of knowledge became common practice from the Sui dynasty (581-618) to the Tang dynasty (618-907), a period of grandeur, expansion and a flourishing of the arts. This period was the first peak of translation in China, although the translations were still mainly of the Buddhist scriptures.Translators in this period were mainly Buddhist monks. They not only had a very good command of Sanskrit but had also thoroughly studied translation theory. Since the translations were mainly on religious scriptures, they thought translators should: " (1) be faithful to the Buddhist doctrine, (2) be ready to benefit the readers (Buddhist believers), (3) concentrate on the translation of the Buddhist doctrine rather than translating for fame." 3The most important figure of the first peak of translation in China was the famous monk of the Tang dynasty—Xuan Zang (600-664), who was the main character in A Journey to the West. In 628, he left Changan (today's Xi'an), the capital of the Tang empire, where he had gone in search of a spiritual master, and set out for India on a quest for sacred texts. He returned in 645, bearing relics and gold statues of Buddha, along with 124 collections of Sanskrit aphorisms from the "Great Vehicle"4 and 520 other manuscripts. A caravan of twenty-two horses was needed to transport these treasures. The emperor-Tai Zong gave him a triumphal welcome, provided him with every possible comfort, and built the "Great Wild Goose Pagoda" for him in Chang'an. Xuang Zang spent the rest of his life in this sumptuous pagoda, working with collaborators on the translation of the precious Buddhist manuscripts he had brought back. In nineteen years, he translated 1335 volumes of Buddhist manuscripts. These translations helped to make Buddhism popular throughout China; even the emperor himself became a Buddhist.Xuan Zang was also the first Chinese translator who translated out of Chinese. He translated some of Lao Zi's (the father of Taoism) works into Sanskrit. He also attempted to translate some other classical Chinese literature for the people of India.Not only was he a great translator and organizer of translation, he was also a great translation theorist whose contribution to translation studies still remains significant today. He set down the famous translation criteria that translation "must be both truthful and intelligible to the populace." In a sense, Xuan Zang, with such a formula, was trying to have the best of two worlds—literal translation and free translation. Before Xuan Zang, Dao An during the Sui dynasty insisted on a strict literal translation, i.e., that the source text should be translated word by word; Kumarajiva during the early Tang dynasty was on the opposite side and advocated a complete free translation method for the sake of elegance and intelligibility in the target language. Thus, Xuan Zang combined the advantages of both Dao An's literal translation—respect for the form of the source text—and Kumarajiva's free translation with his own translation practice, aiming to achieve an intelligibility of the translation for the target language readers, and developed his epoch-making translation criteria that translation "must be truthful and intelligible to the populace." Therefore, in practice, Xuan Zang tried many translation methods. He was the first Chinese translator who tried translation methods like: amplification, omission, borrowing equivalent terms from the target language etc. He was regarded as one of the very few real translators in the history of China for his great contribution to both translation practice and translation theory.Xuan Zang's time is acknowledged by today's translators as the "New Translation Period" in the history of translation in China as compared with Dao An and Kumarajiva's time. The quality of translation was greatly improved in Xuan Zang's "New Translation Period," because the translations were mainly performed by Chinesemonks who had studied Sanskrit abroad. Those monks, after years of study, had a very good command of both the religious spirit and the two languages involved in the translation. In contrast, during Dao An and Kumarajiva's period, the translation of Buddhist scriptures were mainly done by Indian monks who sometimes had to offer rigid translations as a result their lack of linguistic and cultural knowledge of the target language.Apart from Xuan Zang during the Tang dynasty, there were also other monks like Yi Jin, Bu Kong, Shi Cha Nan Tuo etc. who translated a great number of Sanskrit Sutras into Chinese. But they were not as influential as Xuan Zang who contributed to both translation practice and theory.During the late Tang dynasty, fewer people were sent to the west (India) in a quest of sacred texts and the translation of Buddhist scriptures gradually withered.In the Song dynasties (960-1279), although schools of translation of Buddhist scriptures were established, the quality and quantity of translations were not comparable with those of the Tang dynasty. Classic Chinese literature flourished in the Song dynasties. A special Chinese poetic genre- the ci was developed during the Song dynasty, but there was very little progress in translation theory or practice.2.3 Technical Translation during the Y uan and Ming DynastiesFrom the Yuan (1271-1368) to the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), the translation of sutras lost importance. As the Y uan rulers directed their attention westward, Arabs began to settle in China, even becoming mandarins or merchants. Having learned Chinese, some of those erudite high officials translated scientific works from Arabic or European languages. The Arab Al-Tusi Nasir Al-Din (1201-74) translated Euclid's Elements, some works on astronomy including Ptolemy's Almagest, and Plato's Logic. An Arabic pharmacopoeia—Al-Jami fi-al-Adwiya al-Mufradah (Dictionary of Elementary Medicines), was translated toward the end of the Yuan dynasty in thirty-six volumes listing some 1400 different medicines. This was published during the following dynasty as Hui Hui Yao Fang. Later, the Ming emperor- Zhu Yuan Zhang ordered two mandarins of Arab origin, Ma Hama and Ma Shyihei, to translate two Arabic books on astronomy with the help of two Chinese officials, Li Chong and Wu Bozhong. It appears that these translations were carried out merely to satisfy the curiosity of a few scholars. They had some value as reference works, but their scientific merit was minimal, and of no great significance.The situation was to change toward the end of the 16th century. With the arrival of western Christian missionaries, Jesuits in particular, China came into contact with Europe which had begun to overtake China in various scientific and technological fields. To facilitate their relations with Chinese officials and intellectuals, the missionaries translated works of western science and technology as well as Christian texts. Between 1582 and 1773 (Early Qing dynasty), more than seventy missionaries undertook this kind of work. They were of various nationalities: Italian (Fathers: Matteo Ricci; Longobardi; De Urbsis, Aleni and Rho); Portuguese (Francis Furtado); Swiss (Jean Terrenz, Polish (Jean Nicolas Smogolenshi), and French (Ferdinand Verbiest, Nicolas Trigaut).The missionaries were often assisted by Chinese collaborators, such as Xu Guangqi, a distinguished scientist and prime minister during the last years of the Ming dynasty, a period of scholarship and intellectual activity, Li Zhizao, a scientist and government official, Wang Zheng, an engineer and government official, and Zue Fengzuo, a scientist. Matteo Ricci was assisted by Xu Guangqi when he translated Euclid's Elements in 1607 and by Li Zhizaowhen he translated Astrolabium by the German Jesuit and mathematician Christophorus Clavius (1537-1612). For these Chinese scholars, translation was not limited to passive reproduction; instead, the translated texts served as a basis for further research. Li Zhizao, for example, uses his preface to Astrolabium, the first work to set out the foundations of western astronomy in Chinese, to make the point that the earth is round and in motion.With their translation of Clavius's Trattato della figura isoperimetre (Treatise on Isoperimetric Figures), published in 1608, Ricci and Li Dang introduced the concept of equilateral polygons inscribed in a circle. In 1612, a six volume of translation by De Ursis and Xu Guangqi was the first Chinese works on hydrology and reservoirs; it also dealt with physiology and described some of the techniques used in the distillation of medicines. As he translated, Xu Guangqi performed experiments. Thus, he used the book he was in the process of translating as a kind of textbook, and translation was in turn a catalyst, leading to new discoveries. A 1613 translation by Matteo Ricci and Li Zhizao showed how to perform written arithmetic operations: addition, substraction, multiplication and division. They also introduced the Chinese to classical logic via a Portuguese university-level textbook brought in by a missionary in 1625.Although translations carried out during the Ming dynasty were mainly on science and technology: mathematics, astronomy, medicine, hydrology etc., there were also some translations of philosophy and literature in this period. Li Zhizao, with assistance of the foreign missionaries, translated some of Aristotle's works like On Truth into Chinese. In 1625, the first translation of Aesop's Fables was also introduced to Chinese readers.Technical translations during the Ming dynasty facilitated the scientific and technological development of ancient China, and thus foreign missionaries whose main purpose was to promote Christianity became the first group of disseminators of western knowledge.Translations during the Ming dynasty had two distinguishing characteristics : (1) The subject of translation shifted from Buddhist scriptures to scientific and technological knowledge; (2) translators in this period of time were mainly scientists and government officials who were erudite scholars, and the western missionaries who brought western knowledge to China. The effect of the translations was that China was opened to western knowledge, and translation facilitated the scientific and technical development.So successful were the Ming translators as pioneers on technical translation, that some of the translated technical terms are still in use today. However, translation practice was overstressed and no translation theories were developed during the Ming dynasty. By comparison with the large scale of translation of the Buddhist scriptures during the Tang dynasty, translation during the Ming dynasty was not so influential in terms of the history of translation in China. During the Tang dynasty, there was translation practice accompanied by a quest for systematic translation theories, while during the Ming dynasty, the main purpose of translation was to introduce western technical knowledge.3. Translation in Contemporary China3.1 Technical Translation during the Qing DynastyTranslation into Chinese all but stopped for roughly a hundred years with the expulsion of foreign missionaries in 1723. It resumed following the British invasion (1840-1842) and the subsequent arrival of American, British, French and German missionaries. Foreign missionaries dominated scientific and technical translation initially, butChinese translators, trained in China or at foreign universities, gradually took over the transmission of western knowledge.A leading figure during this period was the Chinese mathematician—Li Shanlan (1811-1882), who collaborated with the British missionary Alexander Wylies (1815-1877) on a translation of a work on differential and integral calculus. The Chinese mathematician Hua Hengfang (1833-1902) and the British Missionary John Fryer (1839-1928) translated a text on probability taken from the Encyclopedia Britannica. In 1877, Hua and Fryer translated Hymers' Treatise on Plane and Spherical Trigonometry (1858). This translation is a perfect example of how knowledge is both transmitted and generated through the translation process; it contributed to the dissemination of modern mathematical theory and, at the same time, stimulated the personal research carried out by the translators. Fryer and his collaborators also translated some one hundred chemistry treatises and textbooks. Many of these were published by the Jiangnan Ordance Factory, where Fryer was an official translator.The earth sciences, too, were introduced to China through translation. During the Opium War5, Lin Zexu, a Chinese official, translated part of the Cyclopaedia of Geography by Murray Hugh. Published in 1836, it was the most up-to-date work on world geography. By the end of the Qing Dynasty, many medical books were available in Chinese, Ding Dubao (1874-1952), a physician and translator, having been responsible for over fifty medical translations. He was awarded national and international prizes for his role in translating and disseminating knowledge of medicine and pharmacology.The technical translations in this period promoted the scientific development of China and also contributed to the study of technical translation in China. Fryer, after translating so many books on science and technology, summed up his experience of translation. In his On the Various Methods of Translating, he explained : (1) The fallacy that technical language could not be rendered into Chinese should be refuted; Chinese was expressive as any other languages in the world, and new technical terms could by various means be created in Chinese. (2) A database for technical terminology should be established for all the translators; the same technical terms should be identical in Chinese even if they were translated by different translators. (3) As for selecting the original texts for translation, a translator should translate those books which were in urgent need among the target language readers. He also explained that one should not translate unless one has understood every single word of the original text.3.2 Yan Fu and His Views on TranslationAt the beginning of the nineteenth century, the Yangwu group, comprised of highly placed Foreign Affairs officials, initiated the translation of technical documents dealing with subjects like shipbuilding and the manufacture of weapons, and even established a number of translator training institutions. After the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895, Yan Fu (1853-1921), one of the most important figures in the modern period of translation in China, was the most influential translator and translation theorist. Yan Fu was a cultural intermediary who, at a critical moment in history, sought to make European works of political and social science accessible to the people.Born into a poor family in Fu Zhou, a port in the province of Fujian, Yan Fu attended a naval college and served on warships which took him to places such as Singapore and Japan. From 1876 to 1879, he was in Portsmouth and Greenwich, in England, where he had been sent with a group of naval officers who would later serve in the Sino-Japanese War. In England, he read philosophical and scientific texts voraciously. Upon his return to China, he。

【VIP专享】中国翻译史论提纲(新)2

An Introduction to Chinese Theory of Translation中国翻译理论入门1. A General Introduction to Translation2.Buddhist translation From the late Han Dynasty2.1.A brief Introduction to Buddhist translation2.2. Representatives of Buddhist translation in this period支谦的《法句经序》;道安的“五失本”“三不易”;鸠摩罗什论西方辞体; 彦琮的“八备”;玄奘的“五不翻”;等2.3佛经翻译对中国语言及文学的影响3. Theories of Translation from the late Ming to Early Qing Dynasty3.1. A brief introduction toMissionary translation3.2. Representatives of Buddhist translation in this period徐光启的“超胜”翻译主张;王徵的翻译资用思想;魏象乾的《繙清说》4.Theories of Translation From the Opium War to May Fourth Movement4.1. Representatives of Translators and their theories梁启超的翻译思想; 林纾的翻译思想;马建忠的“善译”4.2. Translation Principles and representative translation principles in this period严复的“信”“达”“雅”以及其他翻译原则5. Theories of Translation From the May Fourth Movement to the Founding of PRC5.1.Representatives of Translators and Their theories鲁迅的翻译思想; 茅盾的翻译批评思想;老舍的翻译思想;郭沫若的翻译思想,郑振铎的翻译思想,朱生豪的戏剧翻译思想5.2. Criteria of translation in this period.6. Theories of Translation after the Founding of PRC6.1. Representatives of Translators and their theories before the 1980s傅雷的“形似”与“神似”之说;钱钟书的“化境”6.2. An Overview of translationTheories after the 1980s.许渊冲的诗歌翻译理论,7. An Overview of Translation Studies and its debate in China8. Further topics教材王秉钦,《20世纪中国翻译思想史》,南开大学出版社,2004.参考文献1.乔曾锐,《译论---翻译经验与翻译艺术的评论和探讨》,中华工商联合出版社,2000.2.王宏印,《中国传统译论经典诠释---从道安到傅雷》, 河北教育出版社,2003。

catti 三级笔译英语

catti 三级笔译英语CATTI (China Accreditation Test for Translators and Interpreters) is a prestigious examination in China for translators and interpreters. It is divided into three levels, with the third level being the highest. This article will provide an overview of the CATTI Level 3 English translation exam, discussing its significance, content, and tips for success.Introduction:The CATTI Level 3 English translation exam is a highly regarded certification that demonstrates a translator's advanced proficiency in English translation. This article aims to shed light on the importance of this certification and provide guidance for those aspiring to pass the exam.I. Significance of CATTI Level 3 English Translation Certification:1.1 Recognition in the Industry:- CATTI Level 3 certification is widely recognized and respected in the translation industry in China.- It serves as a testament to the translator's high level of English proficiency and translation skills.- Many employers, including government agencies and international organizations, require CATTI Level 3 certification for hiring translators.1.2 Career Advancement:- Holding a CATTI Level 3 certification opens up numerous career opportunities for translators.- Translators with this certification are more likely to secure higher-paying jobs and work on prestigious projects.- It enhances one's professional reputation and credibility, leading to increased demand for their services.1.3 Personal Development:- Preparing for the CATTI Level 3 exam allows translators to improve their English language skills and translation techniques.- It provides an opportunity to expand knowledge in various fields, as the exam covers a wide range of topics.- The rigorous preparation required for the exam helps translators refine their time management and critical thinking abilities.II. Content of the CATTI Level 3 English Translation Exam:2.1 Translation Skills:- The exam assesses the translator's ability to accurately and fluently translate English texts into Chinese.- It evaluates the translator's understanding of the source text, grammar, vocabulary, and cultural nuances.- The exam may include texts from various domains, such as politics, economics, science, and literature.2.2 Interpretation Skills:- In addition to translation, the exam also tests the interpreter's consecutive interpretation skills.- The interpreter must be able to listen to an English speech or conversation and accurately interpret it into Chinese.- The exam evaluates the interpreter's ability to maintain the speaker's tone, style, and meaning during interpretation.2.3 Terminology and Knowledge:- The CATTI Level 3 exam requires a deep understanding of specialized terminology in various fields.- Translators must possess extensive knowledge in areas such as law, finance, technology, and medicine.- The exam assesses the translator's ability to accurately use terminology and maintain consistency throughout the translation.III. Tips for Success in the CATTI Level 3 English Translation Exam:3.1 Extensive Reading and Vocabulary Building:- Read a wide range of English texts, including newspapers, books, and academic articles, to improve vocabulary and language comprehension.- Focus on specialized fields to enhance knowledge and understanding of industry-specific terminology.3.2 Practice Translation and Interpretation:- Regularly practice translating and interpreting English texts to improve accuracy and fluency.- Seek feedback from experienced translators or language professionals to identify areas for improvement.3.3 Time Management and Exam Strategies:- Develop effective time management skills to ensure all tasks are completed within the allocated time frame.- Familiarize yourself with the exam format and requirements to develop appropriate strategies for each section.Conclusion:The CATTI Level 3 English translation exam is a significant certification for translators and interpreters in China. It provides recognition, career advancement opportunities, and personal development. Success in the exam requires a strong command of English, translation skills, and specialized knowledge. By following the tips provided, aspiring candidates can enhance their chances of passing the exam and advancing in their translation careers.。

爱尔兰戏剧《翻译》英译汉翻译报告

摘要本文是一篇关于关于将爱尔兰戏剧《翻译》汉译成适合广大中国读者阅读的中文译本的翻译实践报告。

在当前英国脱欧的历史背景下,爱尔兰和北爱尔兰的边境问题成为当下国际社会密切关注的一个时事热点。

而爱尔兰戏剧《翻译》讲述了19世纪80年代一批英国皇家工程兵受英国政府派遣,在多尼戈尔郡的一个爱尔兰语社区进行地貌测绘,并将爱尔兰语地名全部翻译为英语地名的殖民史实。

通过阅读《翻译》,读者可以了解到爱尔兰19世纪的这段被大英帝国殖民统治的历史,有助于理解当前英国脱欧背景下爱尔兰热点问题的历史缘由。

在翻译剧本《翻译》之前,译者做了译前准备工作,针对剧本中的理解难点进行了分析,通过查询有关文献,发现剧本中影响译者和读者理解的很多词汇都属于文化专有项的范畴。

译者根据艾克西拉和诺德关于文化专有项的定义以及纽马克关于文化专有项的分类方法对戏剧《翻译》里出现的文化专有项进行了归类,将戏剧中出现的文化专有项分为三大类别,即地理生态,物质文化和组织机构。

然后根据戴维斯提出的七种翻译策略,以举例分析的方式阐述了译者如何利用这七种策略进行翻译实践。

接着通过举例分析了戏剧《翻译》中三大类别的文化专有项的翻译思路及其对应翻译策略。

综上所述,本文从文化专有项的翻译策略和思路来分析了爱尔兰戏剧《翻译》的翻译过程,为后面的译者在戏剧翻译方面提供了一种参考方法。

关键词:《翻译》;爱尔兰戏剧;布莱恩·弗里尔;文化专有项;AbstractThis is a translation report on the English-Chinese translation of the Irish drama Translations, which analyzes how the translator translated this drama into a target text in simplified Chinese that is readable for ordinary Chinese readers. In the context of Brexit, the Ireland border issue is currently an international hot topic that has attracted attention across the globe. The Irish drama Translations tells about h er Majestey‘s Government sending a group of royal engineers to County Donegal in Ireland to carry out the ordnance survey of this area and change all the geographic names of this county into anglicized and standardized versions in the 1880s. (Qi Yaping 2010:119) By reading Translations, readers can gain an overview on Britain‘s colonization of Ireland i n this period, which helps them understand the historical causes of the Ireland border issues.Before starting the translation task, the author made many pre-translation preparations. By studying the source text, the author found most of the unreadable terms belong to Culture-specific Items. Based on the definition of Culture-specific Items by Aixelá and Nord, as well as the classification method by Newmark, the author classified the Culture-specific Items in Translations into three main categories, ecology, material culture and organizations. By studying the seven translation methods proposed by Davies, the author analyzed each translation strategy through case studies. Then the author analyzed the translation of the three categories of Culture-specific Items in drama Translations and relevant translation strategies employed. Above all, the author of this report explored the translation of Irish drama Translations from the perspective of Culture-specific Items, which could provide later translators a reference on drama translation.Keywords:Translations; Ireland Drama; Brian Friel; Culture-specific Items;CONTENTSCHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION (1)1.1 Brief Introduction to the Translation Task (1)1.2 Target Readers and Requirements of the Client (2)1.2.1 The Target Readers (2)1.2.2 Requirements Proposed by the Client (2)1.3 Purpose and Significance of the Translation Task (3)CHAPTER TWO PRE-TRANSLATION (4)2.1 Convert Format of the Source Text (4)2.2 Analysis of the Source Text (7)2.2.1 Historical Background of the Drama Translations (7)2.2.2 Plot and Characters of the Drama Translations (7)2.2.3 Lexical Features of the Source Text (9)2.2.4 Syntactical Features of the Source Text (10)2.3 Culture-specific Items and Their Translation Strategies (11)2.3.1 Definition of the Culture-specific Items (12)2.3.2 Division of Culture-specific Items (13)2.3.3 Translation Strategies and Methods (14)CHAPTER THREE THE TRANSLATION PROCESS (22)3.1 Translation of the Culture-specific Items on Ecology (22)3.2 Translation of the Culture-specific Items on Material Culture (23)3.3 Translation of the Culture-specific Items on Organizations Terms (25)3.3.1 Translation of Religious terms (25)3.3.2 Translation of Administrative Terms (26)3.4 Summary (27)CAPTER FOUR POST-TRANSLATION (28)CONCLUSION (29)BIBLIOGRAPHY (30)ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (33)Appendix (34)CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION1.1 Brief Introduction to the Translation TaskSince the late 19th century, Irish drama has played an important role in modern theatre literature in the transmission of ideas and ideology. In the 1960s, the famous Irish playwright Brian Friel emerged with his well-known Field Day Theatre Company. Both audience and critics rapidly acknowledged his dramas. Among his acclaimed dramas, Translations is a typical drama that focuses on language and communication, with its theme concerning the relationship between language, identity, politics, history and religion. (Castro, 2013) In order to introduce this drama to Chinese readers, Professor Li Chenjian entrusted the translation task of Translations to author of the report in 2016. Translating this drama from English to Chinese is an attempt to bring Chinese readers a new vision of Irish society in the 19th century. It is also the first time this drama has been translated into Chinese.To complete this translation project, the author of this report needs to complete the following tasks:1) convert the source text from pictures of JPG format into a whole WORD document;2) edit the converted source text to prepare it for translating;3) explore the historical background and playwright‘s creat ion ideas of this drama;4) pre-read the whole text to get an overview of the language features as well as difficult sentences;5) upload the prepared source text to the online translation software Jeemaa and completing the translation process;6) review and revise the translated target text in the online database;7) export the first draft of the translation;8) add footnotes to some difficult words and sentences;9) discuss with Professor Li about the words and sentences that need to be revised;10) revise the target text according to the discussion and read through the revised text to finalize the translation.1.2 Target Readers and Requirements of the ClientBefore starting this translation task, the report author carefully studied the requirements of Professor Li as well as the target readers and previewed the source text of the translation task in order to select proper translation strategies and translation methods accordingly.1.2.1 The Target ReadersAccording to Professor Li, the target readers are general Chinese readers who are interested in theatre literature but tend to, or can only, read Chinese books. As there is no plan to stage this drama in China so far, the performability of the target text is not considered here. That is, the actors or performers of this drama are not included in the target readers. This decides the purpose of the translation task, which is to provide the ordinary Chinese readers an Ireland drama in Chinese for reading. Therefore, this translation purpose helps to select proper translation methods accordingly.Based on our current education syllabus, ordinary readers who have completed their high school education could have the ability to appreciate a drama, either on stage or on the page. However, not everyone who completed high school education is familiar with Irish History or Culture. To provide readers an accessible translation, footnotes should be added to some Culture-specific Items in the target text.1.2.2 Requirements Proposed by the ClientTo achieve a better translation of this drama, Professor Li has proposed some requirements for the target text. The requirements are as follows:1)The source text should be the authoritative version of Translations as given in theformat of JPG.2)The layout of the target text should be consistent with that of the source text.3)The language of the target texts shall be plain and simple Chinese.4)The target text should be suitable for reading rather than staging.5)Footnotes should be added to some Culture-loaded words or sentences.6)The finalized version of this translation task should be ready for printing.1.3 Purpose and Significance of the Translation TaskAccording to the demands of the target readers and the translation requirements by Professor Li, the purpose of this task is to provide the Chinese readers a Chinese version of the Ireland drama Translations.By reading Translations, the Chinese readers can gain an overview of Irish society in the 19th century. As the target text language is plain and smooth simple Chinese, general readers can read it as either a literary story or a historical legend. In the context of Brexit, reading this drama can also provide readers a historical view for the current Ireland border issues.On the other hand, the target text of this drama can also provide other translators with a reference for drama translation. During the translation process, the translator has made great efforts to translate the Culture-specific items in the source text. Davies‘ translation strategies are employed to make the translation more accurate and readable. This kind of target reader-oriented translation is also a good example for similar drama translation in the future.Besides, the author also learnt a lot on the translation strategies of drama translation during the translation process of this drama, as well as the connection between translation and culture studies, which is worth a further study.CHAPTER TWO PRE-TRANSLATIONAs mentioned before, this is the first time this drama has been translated into Chinese. Neither print nor electronic versions of this drama can be obtained in China. The source text provided by the client are pictures of the original drama in JPEG format. To start this translation task, several steps are required, including transforming the source text of Translations into an editable WORD document from these JPG format pictures, analyze the source text and select proper translation strategies and methods.2.1 Convert Format of the Source TextThe original source text is a file of pictures of the Translations in the JPG format. Just as shown in Fig. 2.1 a), it is non-editable. Therefore, the pictures should be converted into an editable WORD document first. A software named ABBYY was applied here.Fig. 2.1 a) one picture of the Translations in the JPG format After converting, the words in the pictures were kept in a WORD document. Then the WORD document was exported from the ABBYY. But the layout of the exported text was not the same as the original copy. There were mistakes in spelling, extra punctuation marks andsentences with missing words, as is shown in Fig. 2.1 b).Fig. 2.1 b) exported text in the WORD documentThe next step is to edit the exported text, correct spelling mistakes and add missing words according to the original pictures of the drama text. After that, the format of the revised text should also be reset to make it consistent with that of the source text. Then the text is ready for translation. As is shown in Fig.2.1 c), the layout of source text is now the same as it is in the original book.Fig. 2.1 c) reset source text that is ready for translation During the pre-processing of the source text, all the editing and typing should be carefully carried out according to the JPG format pictures. When it is completed, the first copy of this processed source text should also be checked sentence by sentence according to the original copy for several times to ensure it is accurate. After several proof readings untilalmost no mistake can be tracked, the source text is ready for translation. The next step is analyzing the source text.2.2 Analysis of the Source TextAs one of Brian Friel‘s representative dramatic works, Translations tells a story that happened in Baile Beag in County Donegal in Ireland in August 1833, which is based on actual historical events. To prepare for the translation task, an analysis of this drama is conducted on its historical background, plot and characters as well as its language features.2.2.1 Historical Background of the Drama TranslationsIn 1824, the British Parliament produced the first Ordnance Survey map of Ireland, which was intended to map and replace every Gaelic name by a translated English equivalent, or a comparable-sounding one in English. At the same time, the educational system in Ireland began a significant transformation. Gradually, all local Irish-speaking schools (the hedge schools) were replaced with national schools where English became the only language of instruction. Through this reform, the British clearly aimed to anglicize, or possibly even ―civilize‖ the Irish population. They also had more practical purposes, of course: taxation, penetration, and ultimately, domination (Reinares & Barberan, 2007:9)2.2.2 Plot and Characters of the Drama TranslationsBefore introducing the plot, profiles of the main characters are listed as follows according to their introduction in the drama. The introduction of the characters helps the reader to gain a quicker and better understanding of the drama plot. Therefore, this part should also be added to the target text as a reference.2.2.2.1 Introductions of the Main CharactersName IntroductionHugh The headmaster of a small hedge school housed in an old barn. He frequently drinks a large amount, but he is by no means drunk. (Brian Friel, 1996: 397) He isa consummate Irish storyteller and educator. He appears egocentric, but isabsolutely charming and astute.Manus Hugh‘s older son, Manus serves as his father‘s unpaid assistant at the hedge school, though he frequently takes the class because of his father‘s drinkinghabits. He is searching for a headmaster position of his own.Owen Hugh‘s younger son. He is now working in the English Army, as a part-time, underpaid, civilian interpreter. His job is to ―translate the quaint, archaic tongueyou people persist in speaking into the King‘s good English‖. (Brian Friel, 1996:404)Maire Manus‘s fiancée, a strong-minded and adventurous woman. (Brian Friel, 1996: 387) She wants to learn English. She is also heroine of the love triangle Manusand is involved in a romantic relationship with Manus and the Lieutenant.Lieutenant Yolland A British soldier working with Owen on the renaming of the Donegal countryside for the Ordnance Survey. Though he does not speak Gaelic, he is fascinated with the Irish countryside and fantasizes about settling down in Baile Beag. His disappearance at the end of this drama brings the drama to a climax.Captain Lancey Lieutenant Yolland‘s commanding officer. Lancey is the British captain leading the local Ordnance Survey efforts.Sarah A student in the hedge school, she has such a serious speech defect that she is considered dumb. (Brian Friel, 1996: 383) Only Manus sees her potential andteaches her slowly, painstakingly, to speak. She lives with an intensity borne ofthe need and inability to communicate.Jimmy Jack Known as the ―Infant Prodigy,‖ Jimmy Jack is a perpetual bachelor in his sixties.He lives in one set of clothes and rarely washes. Eccentric and benignly mad, heis fluent in Greek and Latin. He lives alone and comes to evening classes at thehedge school partly for the company, and partly for the intellectual stimulation.(Brian Friel, 1996: 383)Doalty An open-minded, open-hearted, generous and slightly thick young man. (Brian Friel, 1996: 389-390)Bridget A fresh young girl, ready to laugh, vain, and with a country woman‘s instinctive cunning. (Brian Friel, 1996: 390)Table 2.2.1 Main characters2.2.2.2 Plot of the TranslationsThe drama Translations was set in a hedge-school in the small town of Baile Beag, an Irish speaking community in County Donegal in the summer of 1833. Hugh O'Donnell was the headmaster of a hedge school, a kind of rural school in Ireland that provides basiceducation to farm families. Manus, Hugh's older son, helped his father to teach in the hedge-school. Hugh insisted on teaching in Irish, even though he knew that their language Gaelic would inevitably be replaced by English. Owen was Hugh‘s younger son, who came back to the town with the Royal Engineers, Captain Lancey and Lieutenant Yolland, who were sent to Baile Beag by the government to remap the Irish countryside and change place names into anglicized and standardized versions. One of the engineers, Lieutenant Yolland was then captivated by Irish culture and believes the work they were doing was an act of destruction. Besides this, a love triangle developed among Manus, Yolland and Maire, a strong-minded and adventurous woman in the village. Yolland disappeared mysteriously, and Manus left town, broken-hearted. Owen realized he must remain true to his roots and decided to join the Irish resistance. The drama ended ambiguously, with no solution to the stories, which keeps readers and audience in suspense.The plot of Translations revolves around two main events. First, the arrival of a platoon of Royal Engineers, Lancey and Yolland in Baile Beag. Second, the imminent abolition of the local hedge school, which was run by the schoolmaster Hugh; and its substitution with the new state-run national school and, consequently, the substitution of Irish for English as the teaching language of the Irish speaking community. (Randaccio 2013:115)2.2.3 Lexical Features of the Source TextAs analyzed by the translator before starting the translation task, the most unique lexical feature of the drama Translations is it contains many Gaelic words which are not easy to understand even for English-speakers, such as, poteen (爱尔兰玻丁酒), aqua vitae (―生命之水‖蒸馏酒) and aul fella (老朋友). Besides, there are also many Greek and Latin words and sentences in the drama. As their relevant English translation has been given in the Appendix of the source text, these languages are not going to be discussed here.Besides, there are also many slangs that use some simple words but difficult to understand, such as the preposit ion ‗off‘ from the following sentences.MAIRE:Honest to God, I must be going off my head. I‘m half-way here and I think to myself, ‗Isn‘t this can very light?‘ and I look into it and isn‘t it empty.(梅尔:天哪,我一定是疯了。

翻译方向论文选题[1]

![翻译方向论文选题[1]](https://img.taocdn.com/s3/m/5ad01a264b35eefdc8d33301.png)

序网络学院翻译方向毕业论文(设计)题目号1On the Influence of Bible Culture on the Translation between English and Chinese2The Proper Use of Foreignization and Domestication3Culture Gaps and Untranslatability4The Proper Use of Literal Translation and Free Translation5 A Touch to Translation Theory and Skill6The Translation of Trademarks and Advertising Claims and Their Cultural Connotation 7English Allusion and Its Translation8Cognition and Translation of Metaphor9Translation and Translating: The Theory and Practice10Culturally Loaded English Idioms and Their Translations11On Translator's Obtrusion in Translation12The Translation Studies of Metaphor13Domestication and Foreignization in Translation14C-E Translation in Cultural Context15Machine Translation and Human Translation: in Competition or in Complementation 16Translation of Commercial Lines17English Idioms and Literal Translation and Free Translation18An Overview of Translation in China: Theory and Practice19Analysis of Descriptive Translation Studies20The Translation of English Sentences of Passive Voice21The Vague Strategy and Pragmatic Analysis of Euphemisms22On Translation of Vocabulary with Chinese Characteristics23Unequivalence of Business English Translation24The Study of the Word Connotation in Translation25On the Unequivalence of Translation26On Some Untranslatability27An Analysis of Descriptive Translation Studies28How to Deal with the Ellipsis in Translation29Translation of Idioms and Cultural Differences30Culture Connotation of Color Words and Their Translation31The Comparison and Translation of Chinese and English Allusion32On Translation of Advertisements33How to Select and Use the Literal Translation and Liberal Translation Correctly34Study on Multiplication of Translation Standards35Criticism and Humor in Charles Dickens' Works36Chinese-English Translation in Cultural Contrast37The Factors Effecting Context in Translation38On the Writing Devices Employed in " I Have a Dream " by Martin Luther King39On the Translation of XieHouYu in English40How to Name and Translate the Trademarks of Products for Entering the International Markets41An Analysis on the Phenomenon of Chinglish in Translation42On Literal and Liberal Translation43The Relationship between English Idioms and Its Culture44Culture Difference In Idioms in Translation学院翻译方向毕业论文(设计)题目11的影响文化在翻译《圣经》在英文和中文e Proper Use of Foreignization and Domestication33文化差距和不可e Proper Use of Literal Translation and Free Translation55一触到翻译理论和技巧e Translation of Trademarks and Advertising Claims and Their Cultural Connotation7针对7英语,其翻译gnition and Translation of Metaphor9翻译:9和翻译理论与实践的结合lturally Loaded English Idioms and Their Translations1111 Obtrusion译者的翻译e Translation Studies of Metaphor1313归化和异化的翻译E Translation in Cultural Context15机器翻译和人的翻译:在竞争或补充anslation of Commercial Lines1717英语习语和直译和意译Overview of Translation in China: Theory and Practice19描述性翻译研究19分析e Translation of English Sentences of Passive Voice2121模糊的策略和语用分析委婉语的Translation of Vocabulary with Chinese Characteristics2323 unequivalence商务英语翻译e Study of the Word Connotation in Translation2525的Unequivalence的翻译Some Untranslatability2727分析描述性翻译研究w to Deal with the Ellipsis in Translation2929翻译习语和文化差异lture Connotation of Color Words and Their Translation3131比较汉语和英语和翻译典故Translation of Advertisements3333如何选择和使用直译和自由翻译正确udy on Multiplication of Translation Standards3535批评和幽默在查尔斯·狄更斯的作品了inese-English Translation in Cultural Contrastinese-English Translation in Cultural Contrast37语境在第37影响因素的翻译the Writing Devices Employed in " I Have a Dream " by Martin Luther King3939翻译的XieHouYu英文w to Name and Translate the Trademarks of Products for Entering the International Markets4141分析状态下生成的中国式英语的翻译现象Literal and Liberal Translation43英语习语43之间的关系及其文化lture Difference In Idioms in Translation。

History of Translation in__ China

1) The introduction of Karl Marx’s (1818-1883) and Lenin’s (1870-1924) classical works on socialist and communist theories. April, 1919: Chen Wangdao (陈望道,1890-1977): the full text of the Communist Manifesto (Marx and Engels, 1848) 1922: Lenin’s Nations and Revolution (1917) was translated; 1930: The translation of Marx’s monumental work Capital (1859) was published. The translations and publications of the classical works of Marxism –Leninism provided an ideological preparation for the birth of new China.

History of Translation in China

The earliest historical documents recording (the Rites of Zhou 《周记》 and the Books of Rites《礼记》) sporadic (分散的,个别 的)translation activities in China can be traced back to the Zhou Dynasty (c. 11th century-221 BC) , when officials entitled xiangxu (象胥) or sheren (舌人) carried out translation activities so as to make communication possible between different nations. “ The Song of Yue Nationality”(越人 歌) appeared in the Spring and Autumn Period (722BC -481BC), which might be considered as the first poem translated in ancient China.

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

It was during the Han dynasty (206 BC -----220 BC) that translation became a medium for the dissemination of foreign learning. Buddhism, which originated in India and was unknown outside that country for a very long time began to penetrate China toward the middle of the first century. Therefore, the Buddhist scriptures which were written in Sanskrit needed to be translated into Chinese to meet the need of Chinese Buddhists.

The period from the middle of the first century to the fifth century is categorized as the early stage of translation in China. In this stage, translation practice was mainly of religious scriptures. The core issue in translation theory raised was: literal translation vs. free translation. “Accuracy and smoothness” were taken as criteria for guiding the translation of Buddhist scriptures. This may be considered both primitive translation theory in China, and also the basis of modern translation theory in China.

In the fifth century, translation of Buddhist scripture was officially organized on a large scale in China. A State Translation School was founded for this purpose. An imperial officer —Dao An (道安) was appointed director of this earliest School of Translation in China. Dao An advocated strict literal translation of the Buddhist scriptures, because he himself didn't know any Sanskrit. He also invited the famous Indian Buddhist monk Kumarajiva (鸠摩罗什)(350-410), who was born in Kashmir, to translate and direct the translation of Buddhist scriptures in his translation school.

An Shigao (安世高), a Persian, translated some Sutras (Buddhist Precepts in Sanskrit) into Chinese, and at the same time introduced Indian astronomy to China. Another translator of the same period was Zhi Qian(支谦), who translated about thirty volumes of Buddhist scriptures in a literal manner. His translation was hard to understand because of the extremely literal translation. And it might be in this period of time that there was discussion on literal translation vs free translation— “a core issue of translation theory.”

An Overview of Translation in China

Translation has been crucial to the introduction of western learning and the making of national culture in China. China has an over five thousandyear long history of human civilization and a three thousand-year history of translation.

school flourish and his translations enabled Buddhism to take root as a serious rival to Taoism. From the time of Kumarajiva until the eighth century, the quantity of translations of Sanskrit Sutras increased and their accuracy improved.

1. Translation Practice and Theory in Ancient China

1.1 Early Translation in China

The earliest translation activities in China date back to the Zhou Dynasty (1100.BC). Documents of the time indicated that translation was carried out by government clerks, who were concerned primarily with the transmission of ideologies.

In late Zhou Dynasty, Jia Gongyan (贾公彦), an imperial scholar, defined translation as: “translation is to replace one written language with another without changing the meaning for mutual understanding.” This definition of translation, although primitive, proves the existence of translation theory in the

should sign their names to the translated works.

Kumarajiva himself translated a large n His arrival in China made the translation

Kumarajiva, after a thorough textual research on the former translation of Sanskrit Sutras, carried out a great reform of the principles and methods for the translation of sutras. He emphasized the accuracy of translation. Therefore, he applied a free translation approach to transfer the true essence of the Sanskrit Sutras. He was the first person in the history of translation in China to suggest that translators

Translators in this period were mainly Buddhist monks. They not only had a very good command of Sanskrit but had also thoroughly studied translation theory. Since the translations were mainly on religious scriptures, they thought translators should: “ (1) be faithful to the Buddhist doctrine, (2) be ready to benefit the readers (Buddhist believers), (3) concentrate on the translation of the Buddhist doctrine rather than translating for fame.”

1.2 The First Peak of Translation in China

The translation and importation of knowledge became common practice from the Sui dynasty (581 ------618) to the Tang dynasty (618------907), a period of grandeur, expansion and a flourishing of the arts. This period was the first peak of translation in China, although the translations were still mainly of the Buddhist scriptures.