The Implementation and Organisation of Work Arrays in Numerical Algorithms

Topic2_Organisations组织结构

Topic2_Organisations组织结构Topic 2: Organisations2.1 INTRODUCTIONThis Topic asks you to read important material from the set text book as well as a notes in this work book designed to provide a basic understanding of organisation theory.You are asked to undertake an exercise at the beginning and the end of the Topic that is de-signed to help you relate the theoretical ideas to your work situation in a meaningful way.2.2 LEARNING OBJECTIVESTo gain a basic knowledge of the organisational forms that exists.To become aware of how organisations and people interact.To enhance professional reflection on how you and your organisation relate.2.3 EXERCISE 1In order to get you thinking about organisations please gather the following materials and reflect on them:The organisation chart for your company or organisation.The organisation chart for the business unit within which you work.The organisation chart for the division and/or department in which you work.The organisation chart for the project team(s) in which you work.When you have these materials reflect on how they relate to each other in terms of:Risk managementDecision processesCommunications routesDisciplines (e.g. various engineering disciplines)Human resources managementBudgets and financial managementInteraction (and transactions) with client(s)Interaction (and transactions) with sub-contractors and service providersEducation and training provisionWhen you reflect on these things consider whether there are any communication, reportingor authority issues or problems which become apparent.2.4 ORGANISATIONAL FORMSIn order to analyse an organisation it is first necessary to understand the structure of the or-ganisation. There follows a brief discussion on the shape of organisations (tall or flat) and their type – power, task, matrix and person.2.4.1 Tall or FlatSpan of ControlA manager’s span of control means the number (span) of people that manager actually di-rectly manages. It is generally recognised that 7 or 8 is the most it should be. More than this means that a manager’s work is very fragmented and too stressful.Tall organisations are those with many layers. Spans of control are relatively small but these organisations are said to be relatively less enjoyable to work in compared with flat organisa-tions where spans of control are greater but where there are far fewer layers.Figure 1: Layers and Forms of OrganisationsTall OrganisationsTall organisations have good and bad points. Advantages and disadvantages must be consid-ered in the context of the purpose of the organisation and the nature of the people in the or-ganisation.AdvantagesClose supervision and control of performance is possible due to small spans of control. Rela-tively fast communications are possible if communication lines are well maintained. How-ever, the many layers of the organisation can cause problems in this regard.DisadvantagesSupervisors can become too involved and fail to delegate enough. The many levels of man-agement can make decisions very slow and problematic. This type of organisation is costly due to the many levels. There is a great distance between top management and middle and lower levels. This is not good for morale and team spirit.Flat OrganisationsThe trend is towards flat organisations. There are obvious advantages over tall organisations but there are disadvantages too.AdvantagesSupervisors are forced to delegate. Clear policies are required to support the activities of delegated authority. Careful selection of employees is essential. They need to be well edu-cated and have the potential to function well in this type of organisation.DisadvantagesOverloading and resultant stress in supervisors is not uncommon. Loss of control can occur due to high span of control. There is a requirement for high quality managers. These are very expensive and may be difficult to recruit. The cost of recruiting is also relatively high due to the need to offset risk by careful recruitment.One organisation’s advantage may be another’s disadvantage.2.3.2 Structure of OrganisationsHandy (1993) refers to Harrison’s “ideal types” of organisational culture or organisation structures. It is highly unlikely that these will be found in their pure form. Organisations will usually display a dominant form and aspects of one or more other forms. Departments and project teams can display aspects of these ideal types.Power CultureRole CultureTask Culture (PROJECT MATRIX)Person CultureFigure 2: Power Culture(After Handy (1999) p.183)This type of organisation is rarely large. High levels of control and personal contact are re-quired. This style of organisation requires faith in the individual. The intersections between the concentric circles and spokes are the people in the organisation. The concentric circles represent levels – the centre being the boss (or king). The spokes represent functions. This type of organisation has a high turnover of employees. Morale tends to be low. If the centre leaves the whole structure can quite quickly collapse.Many small and medium enterprises are like this. The Mafia is a power culture. It is not un-common to find this type of organisation in departments of large organisations where the head of department is a powerful character.Figure 3: Role Culture(After Handy (1999) p. 185)This type of organisation is a classic bureaucracy. It is based on the so-called rational ap-proach or sometimes called a functional organisation. In this form there are many procedures and standards. All positions have clear job descriptions. Co-ordination occurs at the top of the organisation. Performance above role or out of role is not required and in fact is not re-warded. People with great initiative and skill in project management do not fit well in this type of organisation. This style of organization works well in a stable environment and an organisation of this type is secure and predictable.This type of organisation may not be a good one in a dynamic industry. However, there are many large organisations that display many aspects of this type. On the other hand govern-ment departments and other such organisations need to be based on this type because they are accountable to the public and they expect continuity, stability, equity and predictability.Figure 4: Task Culture (Matrix)This is a project management matrix organization often very apparent in project based or-ganisations. It is adaptable and very responsive in the market. It enables high flyers to be identified and brought on. Project teams draw on specialists from the functional departments. However, this type of organisation is very stressful as it means that all employees have two managers (a project manager and a functional manager). Control is difficult and stress in managers can result from this. It is essential that employees are carefully selected and then very carefully inducted and trained. Figure 5 indicates the strengths and weaknesses of ma-trix structures.Figure 5: Matrix Structure - Strengths and Weaknesses (After Daft (2007) Exhibit 6.12, p. 211)STRENGTHSWEAKNESSES1. Achieves co-ordination necessary to meet dual demands from customers1. Causes participants to experience dual authority, which can be frustrating and confusing2. Flexible sharing of human resources across products2. Means participants need good inter-personal skills and extensive training3. Suited to complex decisions and fre-quent changes in unstable environment3. Is time consuming; involves frequent meetings and conflict resolution sessions4. Provides opportunity for both functional and product skill development 4. Will not work unless participants understand it and adopt collegial rather than vertical transactional typerelationships 5. Best in medium-sized organisations with multiple products and services5. Requires great effort to maintain power balanceFigure 6: Person Culture(After Handy (1999) p. 190)This is a rare type of organisation. It cannot be large. It is based on mutuality and consent. Individuals leave but are not evicted. Power resides in experts such as with information tech-nology or engineering skills. Personality does not impress but ability and skill does.This is the sort of organisation found in design consultant. Also research and design teams can display a strong tendency in this direction. They are difficult to manage.2.4.3 Static versus Dynamic OrganisationsThe “traditional” role culture functional organisations such as those found in the Former So-viet Union, government ministries and old companies that have undergone little change can be said to be “static hierarchies”. The global business environment with its turbulent politi-cal, economic, social and technological influences requires organisations to be far more re-sponsive to change. The major stakeholders (see Figure 7) of an organisation need a “learning organisation to ensure survival over the long term. Figure 8 indicates the basic dif-ferences in the organisational design between static and dynamic organisations. A very goodFigure 7: Major Stakeholders of an Organisation (After Daft (2007) Exhibit 1.7, p. 23)read on this subject, other than references to change and organisations in McKenna(2006) is the book: “When Giants Learn to Dance”, by Rosabeth Moss Kanter.2.4.4Exercise 2: What is Your Organization Like?Write notes on the following:(i) Define the organisation, department and project team in which you work in terms of the four ideal types discussed above.(ii) Should the organisational form you have defined be changed and if so why?OWNERS AND SHAREHOLDERS Financial return on investment SUPPLIERS Satisfactory transactions Revenue from purchasesCOMMUNITYCorporate citizenContribution to community PayConditions EMPLOYEESSatisfaction PaySupervisionCareer development Work / life balanceCUSTOMERSGoods & services Service Value CREDITORSCreditworthinessMANAGEMENTEfficiency EffectivenessGOVERNMENTObserve laws and regulations Fair competitionORGANISATIONPeople and OrganisationsFigure 8: Organisational Design in Stable and Turbulent Contexts(After Daft (2007) Exhibit 1.8, p. 29)M e c h a n i c a l S y s t e m D e s i g n N a t u r a l S y s t e m D e s i g nO r g a n i s a t i o n a l C h a n g eS t a b l e E n v i r o n m e n t E f f i c i e n t P e r f o r m a n c eT u r b u l e n t E n v i r o n m e n t L e a r n i n g O r g a n i z a t i o n2.5 ORGANISATIONAL DECLINEResearch cited by Daft (2007) has led to a model of organisational decline seen in Figure 9. The first stage (Blinding Stage) is often missed by managers in the organisation. Signs of this stage beginning are such things as procedures not working properly due to being to “cumbersome”, difficulties with clients, over capacity and so on.If the situation created by these problems is not managed with “prompt action” the organisa-tion will lurch into the next stage. The second stage (Inaction Stage) happens because of denial by executives. There is still a way out of the situation through “corrective action” but this is more deep routed action than the “prompt action” necessary at the “Blinded Stage”. The “corrective action” will involve widening participation in decision processes, engendering higher levels of ownership and commitment. It is also important for middle and senior managers to listen to what colleagues and subordinates say is wrong. If the “Inaction Stage” continues it will turn into the “Faulty Action Stage”.The “Faulty Action Stage” is characterised by the need for really serious change due to ma-jor under performance. There is a need to restate values and goals, often accompanies by downsizing and re-organisation. The solution is “Effective Re-organisation”. Failure to ad-dress the problems effectively at this stage will usually result in an inability to prevent total organisational failure. The next stage in decline is “Crisis Stage”.The “Crisis Stage” is typified by anger and an attempt to start again or “go back to basics” as Daft (2007) calls it. The only solution is a major re-organisation. There will normally need to be significant downsizing at this stage. Top managers almost always need to be replaced at this stage if the next stage of decline is to be avoided.The final stage is “Dissolution Stage” to which there are no choices left. The situation be-comes irreversible.These stages can apply to both corporate organisations and projects. Project managers need to be able to read the situation to understand which stage they are at.Figure 9: Stages of Organisational Decline(After Daft (2007) Exhibit 13.8, p. 497)2.6 SUMMARYHopefully you will have now been able to see how some of the theoretical ideas presented in the workbook and textbook relate to your work context.The important things to remember are the basic structural models of organisation design and the issues and problems associated with change in organisations.The following exercises are designed to facilitate the reflective aspects of your learning process.2.7 EXERCISE 3Explain the significance of transformational and transactional leadership with respect to pro-ject management.What are the four ideal types of organisation that can be used to define an organisation?What are the typical problems you would expect to come across in matrix organisations? 2.8 EXERCISE 4Go back to the material you gathered for EXERCISE 1 in this Topic. Look at your notes and the material you gathered.Now reflect on what you wrote again.What do you think that you do that could be changed to improve how you relate to the or-ganisation for which you work? What are the essential changes you would like to see to the organisation that you believe would make your contribution more effective and/or efficient?How can you communicate changes you would like to see in your organisation?2.9 REFERENCES & BIBLIOGRAPHY* Recommended further reading*Daft, R.L. (2007) Understanding the Theory and Design of Organizations, Thompson South Western, Mason, USA. Handy, C. (1999) Understanding Organisations, Penguin.Harrison, R, (1972) How to describe organizations, Harvard Business Review, Sept-Oct.McKenna, E. (2006) Business Psychology and Organisational Behaviour: A student Hand-book, Psychology Press.*Moss Kanter, R. (1994) When Giants Learn to Dance, Routledge, London.Robbins, S.R. and Judge, T.A. (2007) Organizational Behavior, Pearson / Prentice Hall, (Twelfth Edition), Pearson Education Ltd.Directed ReadingThe set textbook for this Module is:McKenna, E. (2006) Business Psychology and Organisational Behaviour: A student Hand-book, Psychology Press. For this Topic it is essential that you read:Chapter 14 Organisation Structure and Design pp 455-504.。

毕马威IT咨询

Publication date: July 2009

© 2009 畢馬威會計師事務所是香港一家合伙 制事務所,同時也是與瑞士合作組織畢馬威國 際相關聯的獨立成員所網絡中的成員。版權所 有,不得轉載。香港印刷。

© 2009 KPMG, a Hong Kong partnership and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International, a Swiss cooperative. All rights reserved.

畢馬威會計師事務所的名稱和標識均屬於瑞士 合作組織畢馬威國際的註冊商標。

二零零九年七月印刷

© 2009 畢馬威會計師事務所是香港一家合伙制事務所,同時也是與瑞士合作組織畢馬威國際相關聯的獨立成員所網絡中的成員。版權所有,不得轉載。 © 2009 KPMG, a Hong Kong partnership and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International, a Swiss cooperative. All rights reserved.

© 2009 畢馬威會計師事務所是香港一家合伙制事務所,同時也是與瑞士合作組織畢馬威國際相關聯的獨立成員所網絡中的成員。版權所有,不得轉載。

© 2009 KPMG, a Hong Kong partnership and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International, a Swiss cooperative. All rights reserved.

加强管理的英语

加强管理的英语Strengthening Management: A Crucial Aspect of Organisational SuccessEffective management is the backbone of any successful organisation. It is the art of coordinating resources, directing employees, and ensuring the smooth operation of a business or institution. In today's fast-paced and ever-changing business landscape, the importance of strengthening management practices cannot be overstated. This essay will delve into the various aspects of management that require attention and how organisations can enhance their overall management capabilities.Firstly, it is crucial for organisations to have a clear and well-defined management structure. This involves establishing clear lines of authority, responsibilities, and reporting mechanisms. A well-structured management hierarchy not only ensures efficient decision-making but also fosters accountability and transparency within the organisation. By clearly delineating roles and responsibilities, employees can better understand their place in the organisation and work towards achieving common goals.Secondly, the selection and development of capable managers is paramount. Organisations should invest in robust recruitment and training programs to identify and nurture individuals with the necessary skills and qualities to excel in managerial positions. This includes a deep understanding of the business operations, strong leadership abilities, excellent communication skills, and the capacity to make well-informed decisions. Continuous training and professional development opportunities for managers can further enhance their skills and enable them to adapt to changing business environments.Another vital aspect of strengthening management is the implementation of effective performance management systems. These systems should be designed to set clear and measurable goals for employees, provide regular feedback, and evaluate their contributions to the organisation. By aligning individual performance with the organisation's strategic objectives, managers can ensure that employees are focused on achieving the desired outcomes. Furthermore, a well-designed performance management system can help identify areas for improvement, facilitate career development, and foster a culture of accountability.Effective communication is another crucial element of strengthening management. Managers must be skilled in effectively conveying information, instructions, and expectations to their team members.This includes regular updates on the organisation's performance, progress on key initiatives, and any changes or challenges that may impact the workforce. Open and transparent communication not only improves employee engagement but also fosters a collaborative work environment where employees feel empowered to share their ideas and concerns.In addition to communication, organisations should also prioritise the development of strong interpersonal skills among their managers. Effective management requires the ability to understand and motivate employees, resolve conflicts, and foster a positive work culture. Managers who possess strong emotional intelligence, empathy, and conflict resolution skills are better equipped to build trust, inspire their teams, and navigate the complexities of human interactions within the workplace.Another critical aspect of strengthening management is the adoption of technology-driven solutions. In today's digital age, organisations can leverage a wide range of technological tools and platforms to streamline their management processes. This includes the use of enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems, project management software, and data analytics tools to enhance decision-making, improve operational efficiency, and foster collaboration among team members.Furthermore, organisations should emphasise the importance of continuous improvement and adaptability in their management practices. In a rapidly evolving business environment, managers must be willing to review and refine their strategies, policies, and procedures on an ongoing basis. This involves actively seeking feedback from employees, monitoring industry trends, and being open to implementing innovative solutions that can enhance the organisation's competitiveness and resilience.Finally, organisations should foster a culture of accountability and responsibility among their managers. This involves holding managers accountable for the performance of their teams, the achievement of their objectives, and the overall success of the organisation. By instilling a sense of ownership and responsibility, managers are more likely to take a proactive approach to problem-solving, decision-making, and driving continuous improvement.In conclusion, strengthening management is a multifaceted and ongoing process that requires a comprehensive and strategic approach. By focusing on factors such as organisational structure, management development, performance management, communication, interpersonal skills, technology adoption, and a culture of accountability, organisations can enhance their overall management capabilities and position themselves for long-term success. Ultimately, effective management is the foundation uponwhich organisations can thrive and adapt to the ever-changing business landscape.。

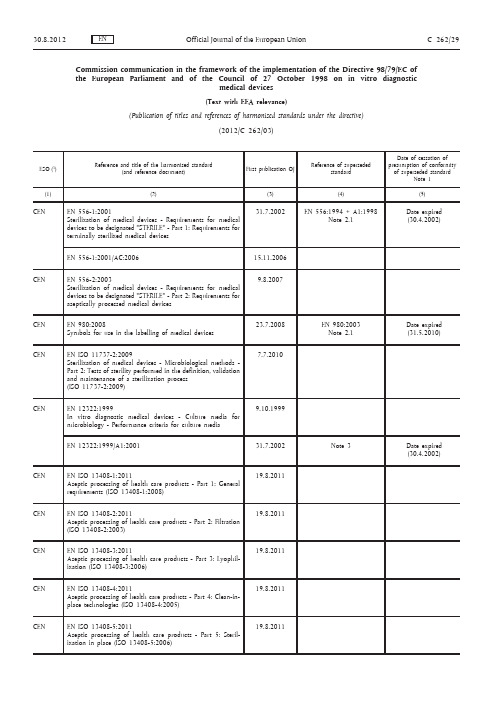

医疗器械欧盟协调标准2012-8-30

Commission communication in the framework of the implementation of the Directive 98/79/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 October 1998 on in vitro diagnosticmedical devices(Text with EEA relevance)(Publication of titles and references of harmonised standards under the directive)(2012/C 262/03)(1) ESO: European Standards Organisation:— CEN: Avenue Marnix 17, 1000 Bruxelles/Brussel, BELGIQUE/BELGIË, Tel. +32 25500811; fax +32 25500819 (http://www.cen.eu)— Cenelec: Avenue Marnix 17, 1000 Bruxelles/Brussel, BELGIQUE/BELGIË, Tel. +32 25196871; fax +32 25196919 (http://www.cenelec.eu) — ETSI: 650 route des Lucioles, 06921 Sophia Antipolis, FRANCE, Tel. +33 492944200; fax +33 493654716, (http://www.etsi.eu)Note 1: Generally the date of cessation of presumption of conformity will be the date of withdrawal (“dow”), set by the European Standardisation Organisation, but attention of users of thesestandards is drawn to the fact that in certain exceptional cases this can be otherwise.Note 2.1: The new (or amended) standard has the same scope as the superseded standard. On the date stated, the superseded standard ceases to give presumption of conformity with the essentialrequirements of the directive.Note 2.2: The new standard has a broader scope than the superseded standard. On the date stated the superseded standard ceases to give presumption of conformity with the essential requirements ofthe directive.Note 2.3: The new standard has a narrower scope than the superseded standard. On the date stated the (partially) superseded standard ceases to give presumption of conformity with the essentialrequirements of the directive for those products that fall within the scope of the newstandard. Presumption of conformity with the essential requirements of the directive forproducts that still fall within the scope of the (partially) superseded standard, but that do notfall within the scope of the new standard, is unaffected.Note 3: In case of amendments, the referenced standard is EN CCCCC:YYYY, its previous amendments, if any, and the new, quoted amendment. The superseded standard therefore consists of ENCCCCC:YYYY and its previous amendments, if any, but without the new quoted amendment.On the date stated, the superseded standard ceases to give presumption of conformity with theessential requirements of the directive.NOTE:— Any information concerning the availability of the standards can be obtained either from the European Standardisation Organisations or from the national standardisation bodies of which the list is annexed tothe Directive 98/34/EC of the European Parliament and Council (1) amended by the Directive98/48/EC (2).— Harmonised standards are adopted by the European Standardisation Organisations in English (CEN and Cenelec also publish in French and German). Subsequently, the titles of the harmonised standards aretranslated into all other required official languages of the European Union by the National StandardsBodies. The European Commission is not responsible for the correctness of the titles which have beenpresented for publication in the Official Journal.(1) OJ L 204, 21.7.1998, p. 37.(2) OJ L 217, 5.8.1998, p. 18.— Publication of the references in the Official Journal of the European Union does not imply that the standards are available in all the Community languages.— This list replaces all the previous lists published in the Official Journal of the European Union. The Commission ensures the updating of this list.— More information about harmonised standards on the Internet athttp://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/policies/european-standards/harmonised-standards/i n dex_en.htm。

key words of management(管理学原理名词解释)

Chapter 1 Innovation for turbulent time(1)1. management is the attainment of organizational goals in an effectiveand efficient manner through planning , organizing, leadingand controlling organizational resources.管理就是通过对组织资源的计划、组织、领导和控制,以有效果和高效率的方式实现组织目标的过程。

2. planning The management function concerned with defining goalsfor future organizational performance and deciding onthe tasks and resource use needed to attain them .计划意味着为未来的组织业绩界定目标和决定为实现上述目标所需要完成的任务和运用的资源。

3. organising The management function concerned with assingning tasks ,grouping tasks into departments, and allocating resourcesto departments.组织包括任务的分配、把多项任务组合成独立的部门和资源在部门之间的分配。

4. leading The management function that involves the use ofinfluence to motivate employees to achieve theorganisation‟s goals .领导就是运动影响力激励员工以便促进组织目标的实现。

5. controlling The management function concerned with monitoringemployees‟activities, keeping the organization on tracktowards its goals , and making corrections as needed.控制意味着对员工的活动进行监督,判定组织是否正朝着既定的目标健康地向前发展,并在必要的时候及时采取矫正措施。

2020年翻译catti一级口译试题及答案(卷十)

2020年翻译catti一级口译试题及答案(卷十)Speech by The Duke of Cambridge at the Children’s Global Media SummitManchester, 6 December 2017Good afternoon, everyone. And thank you very much for having myself and Catherine here.First of all, a word if I might about this fantastic city of Manchester –to which most of you are visitors. You may have seen, if you have had a chance to go outside yet, the symbol of the bee everywhere in the city –the bee is Manchester’s symbol, a reminder of this city’s industriousness and creativity.It’s also a reminder of Manchester’s community spirit, the sense of pulling together. Manchester has had a tough year, and I personally stand in awe of the way that the people of Manchester have united in bravery and support of one another. This community is a great example to all of us, wherever we are from. And I hope you all have a chance to witness some of this remarkable place for yourselves while you are here for the Summit.So, the Children’s Summit. We are all here today because we know that childhood matters.The years of protection and education that childhood has provided are the foundation for our society. The programme makers and techleaders in this room understand that.Our childhood years are the years we learn.They are the years we develop resilience and strength.They are the years where our capacity for empathy and connection are nurtured.They are the years where we impart the values of tolerance and respect, family and community, to the youth that will lead our nations in the future.Parents like Catherine and me are raising the first generation of digitally-immersed children –and this gives us many reasons to be optimistic about the impact of technology on childhood.Barriers to information about the world are falling. The child of today can learn about far-flung corners of the world with previously unimaginable ease.Social media holds the promise for children who can feel isolated to build and maintain friendships.Digital media is seeing today’s young people develop a passion and capacity for civic involvement that is without parallel in human history.Programme makers have access to real-time research that helps them shape engaging, educational content for children in ways that would have been unheard of in years gone by.We should celebrate and embrace these changes.What we cannot do, however, is pretend that the impact of digital technology is all positive or, indeed, even understood.I am afraid to say that, as a parent, I believe we have grounds for concern.I entered adulthood at the turn of the millennium. The generation of parents that Catherine and I are a part of had understood the world of mobile phones, the internet, email, and the like for some time. We had every reason to feel confident.The changes we have incorporated into our own lives as adults have often felt incremental, not revolutionary.The vast array of digital television content that many households enjoy today did not spring up overnight.The birth of the smartphone was heralded as a landmark moment. In truth, though, we incorporated constant texting, checking of email on our devices, and 24/7 availability into our lives over the course of many, many years.The centrality of the internet for education, shopping, and the organisation of domestic life has been the work of two decades.And it’s the gradual nature of this change –the slow warming of the water in the pot if you like –that I believe has led us to a moment of reckoning with the very nature of childhood in our society.The latest Ofcom research into the media consumption habits ofBritish children shows us just how dramatically the landscape has changed without most parents pausing to reflect on what actually is happening.Parents who were born before the invention of the World Wide Web now have children aged 5 to 15 who spend two hours a day online.Ten years after the introduction of the iPhone, [and] over 80 percent of 12 to 15-year-olds have a smartphone.Most of my contemporaries graduated university before any of us had Facebook accounts –and now 74 percent of 12 to 15-year-olds are on social media.And a generation of parents for whom watching television was something that happened as a family around a single set have given a fifth of our 3 to 4-year-olds their own tablets.Now, I am no Luddite –I believe strongly in the positive power of technology, but I am afraid that I find this situation alarming.My alarm does not come from childhood immersion in technology per se. My alarm comes from the fact that so many parents feel they are having to make up the rules as they go along.We have put the most powerful information technology in human history into the hands of our children –yet we do not yet understand its impact on adults, let alone the very young.And let me tell you parents are feeling the pressure. We needguidance and support to help us through some serious challenges.Everywhere you go, mothers and fathers are asking each other the same questions:‘Did you see that so-and-so’s friend had an iPhone at the playground?’‘How can I keep my daughter off social media if all of her friends are on it?’‘How do I know what my children are doing online in their bedrooms? How do I monitor what they’re messaging to other children?’‘How do I find out what apps my children have downloaded?’‘How do we protect family time and teach our kids actual connection, when all their communication is through their phone?’‘How do we convince our children to go outside and be active and fit, when all they want to do is play online?’These conversations are happening right now in our towns and cities and right across the world. We have all let technology slowly creep into our lives. And now we are waking up to the enormity of the challenge technology and modern digital media will mean for children.The people in this room may be the best placed in the planet to help today’s parents, teachers, and caregivers to grapple with these questions. As I said earlier, you are only here because you are passionateabout childhood. Your combined experience and insight can be a powerful force for positive guidance.Parents are eager for your advice about how best to combine technology and innovation with the timeless goal of safe and innocent early years that are filled with love and genuine connection.Like all of you, I believe firmly in the power of bringing people together, people with knowledge and passion, to tackle big issues confronting our society. That is what I did through the Royal Foundation when we established the Taskforce for the Prevention of Cyberbullying.Bullying through phones and social media is an issue that caught my attention after reading about children who had taken their own lives when the pressure got too much.As a former HEMS and Air Ambulance pilot, I was called to the scenes of suicides and I witnessed the devastation and despair it brought about. And I felt a responsibility to do something about it.The Royal Foundation brought together the leading players in digital and social media, the ISPs, academic researchers, and children’s charities. And importantly, we brought children and parents themselves to the table, so their voices could be heard directly.What we heard is that cyberbullying is one of those issues that had been allowed to slowly take root. An age-old problem had been gradually transformed and accelerated by technology that allowed bullies to followtheir targets even after they had left the classroom or the playing field.The technology we put into the hands of our children had for too many families shattered the sanctity and the protection of the home.After a year and a half’s work, the taskforce announced a plan of action last month. The sector agreed to four main areas of work: –the implementation of standard guidelines for the reporting and handling of bullying;–a national advertising campaign to establish a code of conduct for the online behaviour of children;–the piloting of an emotional support platform on social media;–and finally, the members have pledged to continue to work together to offer consistent advice to parents and more material for children to help them thrive online. And you will hear more about this next.I am proud of what was achieved, but, as I said at the time of the plan’s launch, I had hoped we could go further. I am very pleased that the BBC has taken up the challenge of supporting one area that I believe merits further discussion: the creation of a single, universal tool for children to report bullying when they see it or experience it –regardless of which platform it happens on.What we have shown through the taskforce –and what we show when we gather on days like today –is that solutions to our challengesare possible when we all work together.We can be optimistic about the way digital media will help our children when we can be frank about our concerns.Families can embrace technology with confidence when they can access the best support and advice.And we can be hopeful about the future of our society when we all know that protecting the essence of childhood remains our collective and urgent priority.Thank you.汉译英在当今日益全球化的世界里,显然会说两门语言要比单单说一种有实际的好处。

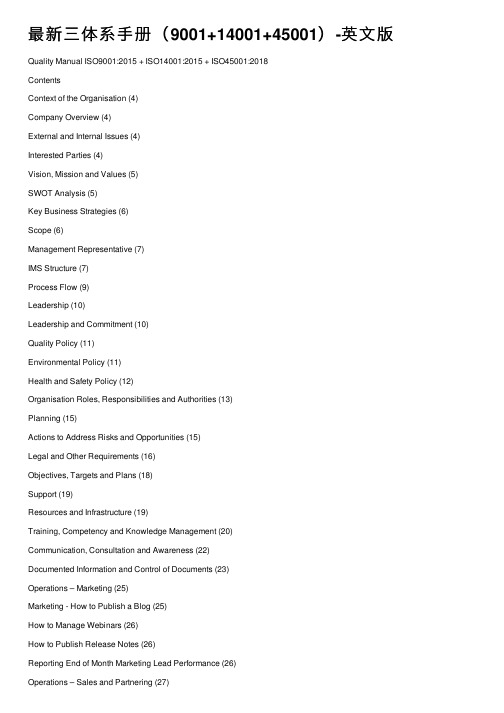

最新三体系手册(9001+14001+45001)-英文版

最新三体系⼿册(9001+14001+45001)-英⽂版Quality Manual ISO9001:2015 + ISO14001:2015 + ISO45001:2018ContentsContext of the Organisation (4)Company Overview (4)External and Internal Issues (4)Interested Parties (4)Vision, Mission and Values (5)SWOT Analysis (5)Key Business Strategies (6)Scope (6)Management Representative (7)IMS Structure (7)Process Flow (9)Leadership (10)Leadership and Commitment (10)Quality Policy (11)Environmental Policy (11)Health and Safety Policy (12)Organisation Roles, Responsibilities and Authorities (13)Planning (15)Actions to Address Risks and Opportunities (15)Legal and Other Requirements (16)Objectives, Targets and Plans (18)Support (19)Resources and Infrastructure (19)Training, Competency and Knowledge Management (20)Communication, Consultation and Awareness (22)Documented Information and Control of Documents (23)Operations – Marketing (25)Marketing - How to Publish a Blog (25)How to Manage Webinars (26)How to Publish Release Notes (26)Reporting End of Month Marketing Lead Performance (26)Operations – Sales and Partnering (27)Sales (27)Partner Process (27)Operations - Development (28)Developers Documentation (28)Development Requests and Bugs (28)Mango Application (29)Operations – Support and Testing (30)Mango Testing (30)Communication of Releases (30)Support (31)Implementation (31)Operations - Supplier Evaluation and Control (32)Operations – Health and Safety (33)Hazard Identification, Assessment and Control (33)Accidents / Incidents (36)Employee Participation (38)Emergency Planning – Health and Safety (40)Operations – Environmental (40)Aspects and Impacts Identification, Assessment and Control (40)Environmental Incident Reporting, Recording and Investigations (41)Environmental Emergency Planning (42)Performance Evaluation (43)Monitoring, Measurement and Evaluation (43)Internal Audit (44)Management Review (44)Improvement (45)Improvement and Corrective Actions (45)Context of the OrganisationCompany OverviewThe company enables its customers to meet their compliance requirements be they ISO 9001, ISO 14001, ISO 45001, local and government legislation and regulations.External and Internal IssuesThe company determines the external and internal issues that are relevant to its purposeand strategic direction and that affect its ability to achieve the intended results of the XXX. Consideration is given to the: Positive and negative factors or conditions.External context and issues, such as legal, regulatory, technological, competitive, cultural, social, political and economicenvironments.Internal context and issues, such as values, culture, organisation structure, knowledge and performance of the business. Determination and requirements of the needs and expectations of interested parties relevant to the XXX.Authority and ability to exercise control and influence.Activities, products and services relevant to the business.Documented information is retained as evidence to support that the context of the organisation has been taken into account in the XXX.Vision, Mission and ValuesVision: “Gets everyone involved and participating in QHSE”Mission: Makes compliance enjoyable.Values: Our customers’ are successful in complianceScopeThe XXX describes how the company requirements are to be addressed throughout its operations and addresses the requirements of ISO 9001:2015, ISO 14001:2015 and ISO 45001:2018.Management RepresentativeThe Operations Manager is the currently appointed Management Representative and has responsibility and authority for:1.Ensuring that the:a.XXX is established, implemented and maintained in accordance with therequirements of ISO 9001:2015, ISO 14001:2015 and ISO 45001:2018.b.XXX processes are delivering their intended outputs.c.Promotion of customer focus throughout the company.d.Integrity of the IMS is maintained when changes to the XXX are planned andimplemented.2.Reporting on the performance of the XXX to top management for review and as a basis forimprovement.IMS StructureInteraction of Processes in the XXThe company’s XX complies with:ISO 9001:2015,ISO 14001:2015ISO 45001:2018The XXX consists of the following levels of documented information:Policies: Policies are documents that demonstrate the overall commitment to improving quality performance and are authorised by the Management Team.System procedures: high-level procedures that define the activities that are to be fulfilled to ensure that the XXX that complies with standards.Module workflows, operational procedures and work instructions. Control and operational procedures:o Meet customers’ requirements.o Provide supplementary guidance and instructions to support the intent of the XXX.o Ensure that the requirements of the XXX will be adequately addressed within the organisation.Forms, registers and records are evidence to prove the XXX is operational.A diagram of the structure of the XXX structure is presented below.Mango compliance software solution:Provides automated workflows for the effective and efficient operation of the XXX.Underpins the XXX and serves as the main retention application for all documented information.Workflows and modules replace written procedures and forms associated with the process. They include the following:Process FlowPurpose and ScopeTo describe the interaction of process through the customer journey. ProcedureLeadershipLeadership and CommitmentPurpose and ScopeTo define how the company demonstrates leadership and commitment to its XXX.Procedure1.Top management will take responsibility for the effectiveness of the IMS and willdemonstrate their commitment to the xxx by:a.Defining roles, allocating responsibilities and accountabilities, and delegatingauthorities, to facilitate effective xxx management.b.Roles and Responsibilities are documented in Leadership - Organisation Roles,Responsibilities and Authorities and through position descriptions, and xxxprocedures where applicable. Ensuring:i.That relevant policies and objectives are established for the xxx and thatthese are aligned with the context and strategic direction.ii.The integration of the xxx requirements into the organisation's businessprocesses.iii.That resources needed for the xxx are available.iv.The IMS achieves its intended results.v.The process approach and risk based thinking is promoted. Communicating the importance of effective xxx management and of conforming to the IMSrequirements.vi.Engaging, directing and supporting personnel to contribute to theeffectiveness of the xxx.vii.Improvement is promoted.viii.Other relevant management roles are supported to demonstrate theirleadership as it applies to their areas of responsibility.2.Top management is committed to our customers and enhancing customer satisfaction. Thiscommitment is demonstrated by:a.Ensuring that applicable customer and statutory requirements are determined,understood and met throughout the business.b.Ensuring the risks and opportunities that can affect conformity of products andservices and the ability to enhance customer satisfaction are determined andaddressed.c.Exercising due care with our customer's property (data) whilst it is under the controlof the company.d.Monitoring customer's perceptions of the degree to which their needs andexpectations have been fulfilled.3.The key aspects of the customer information and data generated through the effectiveimplementation of the IMS processes are collected and collated by the ManagementRepresentative and presented at each Management meeting.Quality PolicyThe company is committed to providing and delivering the customer great product, great support and great marketing to make the management of our customer's compliance an easy and enjoyable experience.We are committed to:Meeting legal requirements.Continually improving our xxx.Meeting the needs and expectations of interested parties.To achieve this we will:Provide our customers with a quality product for the management of their compliance needs.Provide our customers with free content, information and industry insight to improve their compliance knowledge.Provide timely and accurate support to our customersListen to our customers when developing and enhancing the product.Provide an environment where staff can grow and learn new skills.Provide a return to shareholdersWe will measure our progress through:Setting objectivesDocumenting plansReviewing performanceWe will enable this by:Training our employeesTraining our PartnersImproving MangoInvesting in resourcesInvestigating new technologiesEnvironmental PolicyThe organisation has identified environmental management as one of its highest corporate priorities. The organisation has established policies, programmes and practices to reduce risk to the environment and the organisation and conduct business activities in an environmentally sound manner.The organisation is committed to environmental management and will:Integrate its environmental policies and procedures fully into all business activities as a critical element,Comply with all environmental legislation, standards and contract requirements that are applicable to the company’s operation,Continually improve its environmental performance and prevention of environment impact and taking into account current best practice, technological advances, current scientificunderstanding, customer and community needs, educate, train and promote employees to work in an environmentally responsible manner,Complete environmental assessments for aspects and impacts of all new activities that the company may undertake, promote, develop and design services, facilities, equipment andwork practices that have the least environmental impact, taking into account the efficientuse of energy and materials, the sustainable use of renewable resources and the responsible disposal of waste, thereby minimising any serious or irreversible environmental degradation,?Promote and encourage the adoption of these principals by suppliers and contractors acting on behalf of the organisation,Develop, implement and maintain emergency preparedness plans,Foster openness and dialogue with both employees and the public, encouraging them to respond with their concerns or improvement ideas within the scope of the organisation’soperations and maintain a set of environmental objectives and targets that are monitoredthrough the management review process to ensure effectiveness.Health and Safety PolicyThe company is committed to a safe and healthy working environment for everyone using the premises as a place of work or visiting on business.Management will:Set health and safety objectives and performance criteria for all managers and work areas Annually review health and safety objectives and managers’ performance ?Encourage accurate and timely reporting and recording of all incidents and injuriesInvestigate all reported incidents and injuries to identify all contributing factors and, where appropriate, formulate plans for corrective actionActively encourage the early reporting of any pain or discomfortProvide treatment and rehabilitation plans that ensure a safe, early and durable return to workIdentify all existing and new hazards and take all practicable steps to eliminate or minimise the exposure to any hazards Ensure that all employees are made aware of the hazards in their work areas and are adequately trained so they can carry out their duties in a safe mannerEncourage employee consultation and participation in all health and safety matters Enable employees to elect health and safety representativesEnsure that all contractors and subcontractors are actively managing health and safety for themselves and their employees Promote a system of continuous improvement, including annual reviews of policies and proceduresMeet legal obligations as specified in the legislation, codes of practice and any relevant standards or guidelines.Every manager, supervisor or foreperson is accountable to the employer for the health and safety of employees working under their direction.Each employee is expected to help maintain a safe and healthy workplace through:Share in the commitment to health and safety.Following all safe work procedures, rules and instructionsProperly using all safety equipment and clothing providedReporting early any pain or discomfortTaking an active role in the company’s treatment and rehabilitation plan, for their ‘early and durable return to work’Reporting all incidents, injuries and hazards to the appropriate person.The Health and Safety Committee includes representatives from senior management and union and elected health and safety representatives. The Committee is responsible for implementing, monitoring, reviewing and planning health and safety policies, systems and practices.Organisation Roles, Responsibilities and AuthoritiesPurpose and ScopeTo describe the responsibilities and authorities for the xxx and to define the organisation structure for the effective operation of the xxx.Associated DocumentsJob/Position Descriptions.Employee Contracts.Human Resources Module.Access Rights Sub-Module.Procedure1.The responsibility, accountability and authority of all personnel involved in the xxx is to be defined, documented and communicated in order to facilitate effective xxx. This is to include any responsibilities and accountability that is imposed by legislation.2.Responsibilities, accountabilities and authorities are documented in position descriptions and throughout the xxx.3.Where suppliers are involved, their responsibilities and accountabilities are to be clarified and documented by the responsible employee with authority.4.All employees and Suppliers will comply with their responsibilities.The Management Team are to:1.Ensure organisation-wide compliance to the xxx.2.Appoint the xxx Management Representative.3.Ensure that the assigned roles, responsibilities and authorities are communicated and understood./doc/2915976688.htmlmunicate the importance of meeting customer, statutory and regulatory requirements.5.Establish appropriate policies that include a commitment to continual improvement of the xxx.6.Establish IMS objectives.7.Ensure that all employees are aware of:a.Policies.。

Innova

Innovation and Knowledge CreationThere are two major aspects to innovation – the development of ideas and knowledge on the one hand, and the concrete implementation of them on the other. Knowledge creation in organisations is therefore a central tenet of innovation and must be well understood by anyone looking for ways to stimulate innovation.This paper provides an overview of the predominant theory of organisational knowledge creation. This was first described comprehensively in the book ‘The Knowledge Creating Organisation’ by Nonaka and Takeuchi in 1995, but with its roots in an earlier HBR article from 1986 entitled ‘The New New Product Development Game’. This paper introduces the analogy of the game of rugby for team based knowledge creation and first uses the word scrum which was later picked up an used to name what is now the most widely used agile method. So agile and innovation have had a common root from their earliest days.The ability of an organisation to create new knowledge is essential to its innovation capability [1-5]. Nonaka, Toyama et al. [6] go further stating that “The raison d’etre of a firm is to continuously create knowledge”, Drucker [7] states that knowledge is “the only meaningful resource” while Adler [8] proposes that “knowledge creation…. reaches into the heart of the process of technological innovation”. Other research has demonstrated the relationship of knowledge management on organisational competencies and hence business performance. This so called “knowledge value chain” includes dimensions of strategy, management and operations [9]. Research also differentiates tacit and explicit knowledge in this regard, where it is proposed that “sustainability of competitive advantage . . . requires resources which are idiosyncratic . . . and not so easily transferable or replicable. The criteria point toknowledge (tacit knowledge in particular) as the most strategically importantresource of the firm” [10].The SECI framework assumes that organisations are knowledge creating entities, not merely information processing ones. This ability is necessary to be successful where there is constant change in business pressures and environment requiring continuous change and adaptation. New knowledge is essential for such adaptation, making organisational knowledge creation a necessary capability. Similarly, agility at both the team and organisational level are necessary and also assume constant change. Indeed, agile ISD methods aspire to ‘embrace’ such change for competitive advantage. Nonaka – Organisational Knowledge CreationIn his seminal 1994 paper, Nonaka introduces a theory of how new knowledge is created within an organisation. He starts by describing how much extant theory of organisations has been dominated by the view that organisations process information, rather than creating it. However, the creation and use of new knowledge is central to organisations ability to innovate, and therefore this widespread view is insufficient to explain the creation, definition and solving of problems which is innovation. Nonaka’s theory is based on the following underlying constructs:•Epistemological: There exist two forms of knowledge – tacit and explicit.•Ontological: Although knowledge is formed by individuals, the interactions common within organisations can develop and refine it.Using these two ‘dimensions’ of knowledge creation, Nonaka proposes a spiral model where tacit and explicit knowledge are in continuous dialogue through the interactions in communities of practice. This leads to further development, clarification and amplification of the knowledge.For an individual to acquire knowledge, Nonaka proposes they must be ‘committed’. That is, they must have an intention, an action oriented concept which forms their approach to the world. The value of information, and the knowledge to which it can contribute, depends on the intention of the receiver, and not purely on the nature of the information itself. Therefore, the perception, context and prior knowledge of the individual affects the possibility and form of meaning derived from it. Additionally, autonomy at both individual and group level is essential to provide the freedom to absorb new knowledge – this does not need to be absolute freedom, but reflect a‘minimum critical specification’ [11]. And lastly, knowledge creation requires‘fluctuation’ whereby there are discontinuities in the interaction of an individuals knowledge with their perceived reality, leading to re-evaluation of assumptions underlying their current knowledge. Such breakdowns or contradictions therefore contribute to the creation of new knowledge.With these factors in place, Nonaka postulates a ‘spiral of knowledge’ whereby knowledge is converted through 4 modes from explicit, declarative form to tacit, procedural form and vice-versa. Furthermore, the act of converting from one form to the other are complementary, leading to the knowledge expanding over a period of time.•Socialisation: Representing conversion from tacit to alternate tacit forms, this can occur through shared experience (for example apprenticeship), can rarelybe achieved through abstracting knowledge into an external form, and canoccur without language.•Externalisation: The use of metaphors to convert tacit knowledge to explicit form – writing of poetry could be regarded as an example of this wherebycomplex and nuanced knowledge is transferred through metaphor to anexplicit form.•Combination: By combining multiple externalised knowledge sources through socialisations such as meetings and conversations, this mode allowscombining of explicit knowledge to create new knowledge.•Internalisation: Converting explicit knowledge to a tacit form reflects the traditional view of learning and is associated with ‘action’ based on the newly acquired knowledge.Nonaka’s model rejects what he calls the mechanistic view of the organisation, whereby intervention in the form of training is required to bring about double loop learning and therefore innovation. This is related to the ‘information processing’ view of the organisation, whereas continual creation of knowledge is built into the concept of an organisation as a knowledge creator.Conceptualisation is a core element of creativity, and therefore innovation. Conceptualisation is supported by face to face communication which allows for the co-development of ideas. Dialectic intercourse in temporary and multi-faceted dialogues where participants can express their own ideas freely and openly, affirming and negating these in mutually constructive ways, leads to a synthesis of new knowledge. To allow such rich interaction requires a redundancy of information on behalf of the participants, which allows ‘learning by intrusion’ but can also limit diffusion of new perspectives to more promising directions. This effect can reduce information overload and the pursuit of less productive ideas. Such dialectic dialogue also supports more radical innovation by supporting what [12] calls abduction. He argues deduction and induction are reasoning processes that can lead to revisions or extensions of pre-existing concepts, whereby abduction involves lateral extension through the use of tacit knowledge and metaphors to arrive at more radical, and potentially meaningful, perspectives.Moving from concepts to crystalisation involves internalisation of knowledge within the organisation. This is a cooperative activity, potentially involving a wide scope of personnel and functions, and even extending into the external value network. Experimentation can result in refinement or abandonment of the concept. Overlapping of roles facilitated by information redundancy leads to a ‘rugby-style’ activity rather than a linear ‘pass the baton’ process involving distinct specialisations and demarcations. Empirical evidence shows this leads to faster product development in Japanese firms. One potential downside is confusion caused through changing requirements though speed of execution can mitigate this.In developing a context for organisational knowledge creation, [13] five “enabling conditions” are proposed. Three of these - intent, autonomy and fluctuation – are derived from earlier work but are further expanded on while two new conditions – information redundancy and requisite variety - are introduced. These five enablers are described in further detail below.anisational intent reflects the organisations aspiration to its goals. Intentimplies a collective commitment to a certain strategy and such commitment is essential to any human knowledge creation activity. The value of knowledgeis only valid in relation to the intent. Therefore, strategic intent, oftenexpressed as organisational vision, directs knowledge creating efforts insupport of the goals of the business. This can be operationalised as a set ofstrategic technology areas which support existing or emerging products andservices – knowledge creation within these areas are therefore aligned withthe intent of the organisation.2.Providing as much autonomy to individuals as circumstances permit, as wellas contributing to motivation, can result in unexpected opportunities. Self-organising individuals are more flexible in acquiring and relating informationand this supports information redundancy. This approach also reflects the“minimum critical specification” principle [11], or in terms of agile ISDmethods, “barely sufficient methodology” [14]. Together with intention andinformation redundancy, this condition is reflected in the entire teamoperating like a rugby team, all autonomous and yet co-ordinated, as opposedto a relay team where each individual has a predefined goal and the baton ispassed from one to the other.3.As well as inducing individual commitment, environmental fluctuation cancreate ‘creative chaos’ which can trigger organisational knowledge creation.Such crises, while seen as leading to variability and hence inefficiency in aninformation processing view of the organisation, can be beneficial in thelearning organisation and even intentionally induced by management. Suchlearning, and the acting on it, can be regarded as innovation, as theorganisation adapts to the new context in which it finds itself. However,Nonaka warns that addressing such chaos requires ‘reflection-in-action’ toavoid a destructive effect – such reflection should be institutionalised in thelearning organisation. Fluctuation can be invoked intentionally by inducing asense of crisis or challenge, or introducing ambiguity, a condition alsoadvocated for innovation [15].4.Another core attribute is redundancy of information, which facilitatesefficient knowledge flow and absorption, as well as empowerment of the team through participation of members on the basis of consensus and commonunderstanding. This reflects use of knowledge to facilitate the absorption ofadditional learning which can in turn enable innovation [16]. Redundancyalso creates resiliency within the team through the “principle of redundancyof potential command” [17] quoted in [13] and supports the development oftrust between team members. To build redundancy, tactics such as strategicrotation between functions, teams and technologies have been shown to beeffective. Also, developing alternate competing solutions to support set baseddecision making ensures the team looks at the problem from severalperspectives and hence increases learning.5.Finally, Nonaka proposes Ashby’s principle of ‘requisite variety’ [18] inbalancing the creation of knowledge and its effective processing. Accordingto this principle, the diversity of knowledge at any point in the organisationshould match the diversity it must process. Therefore, organisational members should know who owns what information and how to access it but should notbe exposed to it all to avoid overload.The framework also introduces a temporal element in the form of a five phase process, enabled by the conditions described above and incorporating the four knowledge transformations. The five phases are sharing of tacit knowledge, the creation of new concepts, their qualification and justification, creation of archetypes of the concepts and finally dissemination of the new knowledge across the organisation. Each phase is described below, including the knowledge transformation involved and how each enabling condition comes into play.•Sharing tacit knowledge: Primarily socialisation. Employs requisite variety of the diverse team, members experience redundancy via this diversity &share organisational intent. Management adds fluctuation & autonomy.Accumulates tacit & explicit knowledge.•Creating concepts: Mainly externalisation. Contradictions & paradoxes used to synthesize new knowledge. Autonomy helps free thinking, intention helpsconvergence. Variety provides different perspectives, fluctuation encourages useof these and redundancy helps crystalise around a common shared understanding •Justifying concepts: Screening/filtering/qualifying of concepts – assessing against organisational intent – are they of value? Cost, profit margin, growthpotential, but also qualitative – can be judgemental, value laden. Redundancyof Info can help make valid judgements.•Building an archetype : Primarily combination – from explicit concepts to explicit archetypes.In the case of product, this could be a prototype.Combining existing with new externalised knowledge. Diversity ensuresarchetype satisfies all criteria. Redundancy aids in orchestrating the complexinter-departmental processes while intent can guide & stimulate the activity •Cross-levelling knowledge : Primarily Internalisation. Archetype is diffused vertically & horizontally (ontological diffusion), initiating new cycles ofinnovation. Autonomy legitimises internalisation of knowledge, intent directs it, fluctuation facilitates it by disrupting the status quo and informationredundancy and requisite variety enable it.According to Nonaka and Takeuchi [13] the more traditional forms of management structure of top-down and bottom-up do not encourage knowledge sharing and therefore inhibit organizational learning and knowledge creation. Such structures make it difficult for individuals and groups to interact with one another and prevent the exchange of tacit and explicit knowledge. They propose a “middle up down” management model requires that top management develop and effectively articulate a vision for the organisation, supported by a clearly defined business strategy and policy. This reflects the condition of ‘intention’ described above. Middle management is then charged with leveraging the expertise in the lower levels of the organisation in achieving concrete implementation of that vision. In doing so, middle management are provided the autonomy to work out how to best to utilise the organisational assets, including knowledge, to reach the desired goal. Middle managers become the key knowledge creators of the organisation, positioned at the center of both horizontal and vertical information flows. Front line employees, being close to the market, can receive too much information, of an ambiguous kind, and may not be equipped with the conceptual frameworks with which to interpret it effectively. While top managers create the ‘grand’ theory of what ought to be, middle managers are well positioned to create the mid-range theory of how the current reality can be made approach this desired state. The contradictions and divergence of the organisation’s vision to the current reality can create the ambiguity and fluctuation wherein innovation and creativity thrives. The three roles articulated above can be represented as knowledge practitioners, knowledge engineers and knowledge officers. These correspond to front-line, middle and top management respectively and, as the names suggest, reflect the various roles in knowledge creation advocated by the middle up down management model.REFERENCES1.Nonaka, I., The Knowledge-Creating Company. Harvard Business Review,1991. 69(6): p. 96-104.2.Nonaka, I., A Dynamic Theory of Organisational Knowledge Creation.Organization Science, 1994. 5(1).3.Leonard-Barton, D., Wellsprings of Knowledge: Building and Sustaining theSources of Innovation. 1995, Boston: Harvard Business School Press.4.Teece, D.J., G. Pisano, and A. Sheuen, Firm Capabilities, Resources and theConcept of Strategy: Four Paradigms of Strategic Management. 1990, Center for Research in Management, University of California, : Berkeley.5.Senge, P., The Fifth Discipline. 1990, New York: Doubleday.6.Nonaka, I., R. Toyama, and A. Nagata, A Firm As A Knowledge CreatingEntity: A New Perspective On The Theory Of The Firm. Industrial &Corporate Change, 2000. 9(1): p. 1-20.7.Drucker, P., Post-Capitalist Society. 1993, London: Butterworth Heinemann.8.Adler, P.S., The Dynamic Relationship Between Tacit and CodifiedKnowledge: Comments on Ikujiro Nonaka’s, “Managing Innovation as anOrganizational Knowledge Creation Process”, in International Handbook of Technology Management, G. Pogorel and J. Allouche, Editors. 1995:Amsterdam.9.Carlucci, D., B. Marr, and G. Schiuma, The knowledge value chain: howintellectual capital impacts on business performance. International Journal of Technology Management, 2004. 27(6/7): p. 575-590.10.Grant, R.M., Organizational capabilities within a knowledge-based view ofthe firm., in Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management. 1993: Atlanta,Georgia.11.Morgan, G., Images of Organization. 1986, Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.421.12.Bateson, G., Steps to an Ecology of Mind. 1973, London: Paladin.13.Nonaka, I. and H. Takeuchi, The Knowledge-Creating Company. 1995, NY:Oxford University Press.14.Highsmith, J., Agile Software Development Ecosystems. 2002, Boston, MA:Pearson.15.Lester, R. and M. Piore, The Missing Dimension. 2004, Boston: HarvardUniversity Press.16.Cohen, W.P. and D.A. Levinthal, Absorptive Capacity: A New Perspective onLearning and Innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 1990. 35(1).17.mcculloch, w., Embdiments of Mind. 1965, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.18.Ashby, W.R., An Introduction to Cybernetics. 1957, New York, N.Y.:Chapman and Hall.。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。