alice walker

Alice Walker

Alice Walker艾丽丝·沃克(Alice Walker,1944—)是20世纪70年代以来(欧美国家第二次妇女运动之后)美国文坛最著名的黑人女作家之一。

她在她的小说里生动的反映了黑人女性的苦难,歌颂了她们与逆境搏斗的精神和奋发自立的坚强性格。

为了区别于其它女权主义者,她提出了“妇女主义”(Womanism)这一独特的思想概念。

如果说妇女主义是理论,她的长篇小说《紫色》(The Color Purple)便是对这一理论的具体实践。

《紫色》自1982年发表以来,便轰动美国文坛,接连获得了美国文学作品的三个大奖:普利策奖、全国图书奖和全国书评家奖。

艾丽丝·沃克成为获得普立策奖的第一个黑人女作家。

艾丽斯·沃克1944年2月9日出生于南方佐治亚州的一个佃农家庭,父母的祖先是奴隶和印度安人,艾丽斯是家里八个孩子中最小的一个。

艾丽斯8岁时,在和哥哥们玩“牛仔与印度安人”的游戏时被玩具枪射瞎了右眼。

1961年艾丽斯获奖学金入亚特兰大的斯帕尔曼大学学习,正赶上美国民权运动的高涨时期,她即投身于这场争取种族平等的政治运动。

1962年,艾丽斯·沃克被邀请到马丁·路德·金的家里做客。

1963年艾丽斯到华盛顿参加了那次著名的游行,与万千黑人一同聆听马丁·路德·金“我有一个梦想”的讲演。

艾丽斯大学毕业前在东非旅行时怀孕,当时流产仍属非法,她经历了一段想要自杀的痛苦时期,同时也写下了一些诗歌。

1965年艾丽斯大学毕业后回到了当时是民权运动中心的南方老家继续参加争取黑人选举权的运动。

在活动中艾丽斯遇上了犹太人列文斯尔,俩人克服跨种族婚姻的重重困难结为“革命伴侣”,艾丽斯再一次怀孕,但不幸的是在参加马丁·路德·金的葬礼时因悲伤而痛失孩子。

在列文斯尔的鼓励下,艾丽斯继续写作并先后发表了诗集《一度》(Once,1968)和小说《格兰奇·科普兰的第三次生命》(The Third Life of GrangeCopeland,1970)。

Alice Walker简介

2016/12/8

18

The Pulitzer Prize for Fiction is one of the seven American Pulitzer Prizes that are annually awarded for Letters, Drama, and Music. It recognizes distinguished fiction by an American author, preferably dealing with American life, published during the preceding calendar year. 2016/12/8

19

The National Book Awards are a set of annual U.S. literary awards. At the final National Book Awards Ceremony every November, the National Book Foundation presents the National Book Awards and two lifetime achievement awards to authors.

2016/12/8 3

2016/12/8

4

Introduction Writing career Selected Awards and Honors The Color Purple

2016/12/8 5

Born:February 9, 1944 (age 72) Putnam County, Georgia, U.S.

• • • • • • • • • • • •

1988 — Living by the Word 1989 — The Temple of My Familiar 1991 — Her Blue Body Everything We Know: Earthling Poems 1965-1990 Complete 1991 — Finding the Green Stone 1992 — Possessing the Secret of Joy 1993 — Warrior Marks 1996 — Alice Walker: Banned 1996 — The Same River Twice: Honoring the Difficult 1997 — Anything We Love Can Be Saved: A Writer's Activism 1998 — By the Light of My Father's Smile 2000 — The Way Forward Is with a Broken Heart

Everyday Use-Alice Walker(《祖母的日常用品》爱丽丝.沃克)原版辅导教学问题

Everyday UseAlice WalkerI will wait for her in the yard that Maggie and I made so clean and wavy yesterday afternoon. A yard like this is more comfortable than most people know. It is not just a yard. It is like an extended living room. When the hard clay is swept clean as a floor and the fine sand around the edges lined with tiny, irregular grooves, anyone can come and sit and look up into the elm tree and wait for the breezes that never come inside the house.Maggie will be nervous until after her sister goes: She will stand hopelessly in corners, homely and ashamed of the burn scars down her arms and legs, eyeing her sister with a mixture of envy and awe. She thinks her sister had held life always in the palm of one hand, that “no” is a word the world never learned to say to her.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------2You’ve no doubt seen those TV shows where the child who has “made it” is confronted, as a surprise, by her own mother and father, tottering in weakly from backstage. (A pleasant surprise, of course: What would they do if parent and child came on the show only to curse out and insult each other?) On TV mother and child embrace and smile into each other’s faces. Sometimes the mother and father weep; the child wraps them in her arms and leans across the table to tell how she would not have made it without their help. I have seen these programs.Sometimes I dream a dream in which Dee and I are suddenly brought together on a TV program of this sort. Out of a dark and soft-seated limousine I am ushered into a bright room filled with many people. There I meet a smiling, gray, sporty man like Johnny Carson who shakes my hand and tells me what a fine girl I have. Then we are on the stage, and Dee is embracing me with tears in her eyes. She pins on my dress a large orchid, even though she had told me once that she thinks orchids are tacky flowers.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------3In real life I am a large, big-boned woman with rough, man-working hands. In the winter I wear flannel nightgowns to bed and overalls during the day. I can kill and clean a hog as mercilessly as a man. My fat keeps me hot in zero weather. I can work outside all day, breaking ice to get water for washing; I can eat pork liver cooked over the open fire minutes after it comes steaming from the hog. One winter I knocked a bull calf straight in the brain between the eyes with asledgehammer and had the meat hung up to chill before nightfall. But of course all this does not show on television. I am the way my daughter would want me to be: a hundred pounds lighter, my skin like an uncooked barley pancake. My hair glistens in the hot bright lights. Johnny Carson has much to do to keep up with my quick and witty tongue.But that is a mistake. I know even before I wake up. Who ever knew a Johnson with a quick tongue? Who can even imagine me looking a strange white man in the eye? It seems to me I have talked to them always with one foot raised in flight, with my head turned in whichever way is farthest from them. Dee, though. She would always look anyone in the eye. Hesitation was no part of her nature.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------4“How do I look, Mama?” Maggie says, showing just enough of her thin body enveloped in pink skirt and red blouse for me to know she’s there, almost hidden by the door.“Come out into the yard,” I say.Have you ever seen a lame animal, perhaps a dog run over by some careless person rich enough to own a car, sidle up to someone who is ignorant enough to be kind to him? That is the way my Maggie walks. She has been like this, chin on chest, eyes on ground, feet in shuffle, ever since the fire that burned the other house to the ground.Dee is lighter than Maggie, with nicer hair and a fuller figure. She’s a woman now, though sometimes I forget. How long ago was it that the other house burned? Ten, twelve years? Sometimes I can still hear the flames and feel Maggie’s arms sticking to me, her hair smoking and her dress falling off her in little black papery flakes. Her eyes seemed stretched open, blazed open by the flames reflected in them. And Dee. I see her standing off under the sweet gum tree she used to dig gum out of, a look of concentration on her face as she watched the last dingy gray board of the house fall in toward the red-hot brick chimney. Why don’t you do a dance around the ashes? I’d wanted to ask her. She had hated the house that much.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------5I used to think she hated Maggie, too. But that was before we raised the money, the church and me, to send her to Augusta to school. She used to read to us without pity, forcing words, lies, otherfolks’ habits, whole lives upon us two, sitting trapped and ignorant underneath her voice. She washed us in a river of make-believe, burned us with a lot of knowledge we didn’t necessarily need to know. Pressed us to her with the serious ways she read, to shove us away at just the moment, like dimwits, we seemed about to understand.Dee wanted nice things. A yellow organdy dress to wear to her graduation from high school; black pumps to match a green suit she’d made from an ol d suit somebody gave me. She was determined to stare down any disaster in her efforts. Her eyelids would not flicker for minutes at a time. Often I fought off the temptation to shake her. At sixteen she had a style of her own: and knew what style was.6I never had an education myself. After second grade the school closed down. Don’t ask me why: In 1927 colored asked fewer questions than they do now. Sometimes Maggie reads to me. She stumbles along good-naturedly but can’t see well. She knows she is not bright. Like good looks and money, quickness passed her by. She will marry John Thomas (who has mossy teeth in an earnest face), and then I’ll be free to sit here and I guess just sing church songs to myself. Although I never was a good singer. Never could carry a tune. I was always better at a man’s job. I used to love to milk till I was hooked in the side in ’49. Cows are soothing and slow and don’t bother you, unless you try to milk them the wrong way.I have deliberately turned my back on the house. It is three rooms, just like the one that burned, except the roof is tin; they don’t make shingle roofs anymore. There are no real windows, just some holes cut in the sides, like the port-holes in a ship, but not round and not square, with rawhide holding the shutters up on the outside. This house is in a pasture, too, like the other one. No doubt when Dee sees it she will want to tear it down. She wrote me once that no matter where we “choose” to live, she will manage to come see us. But she will never bri ng her friends. Maggie and I thought about this and Maggie asked me, “Mama, when did Dee ever have any friends?”--------------------------------------------------------------------------------7She had a few. Furtive boys in pink shirts hanging about on washday after school. Nervous girls who never laughed. Impressed with her, they worshiped the well-turned phrase, the cute shape, the scalding humor that erupted like bubbles in lye. She read to them.When she was courting Jimmy T, she didn’t have much time to pay to us but turned all her faultfinding power on him. He flew to marry a cheap city girl from a family of ignorant, flashy people. She hardly had time to recompose herself.When she comes, I will meet—but there they are!Maggie attempts to make a dash for the house, in her shuffling way, but I stay her with my hand. “Come back here,” I say. And she stops and tries to dig a well in the sand with her toe.It is hard to see them clearly through the strong sun. But even the first glimpse of leg out of the car tells me it is Dee. Her feet were always neat looking, as if God himself shaped them with a certain style. From the other side of the car comes a short, stocky man. Hair is all over his head a foot long and hanging from his chin like a kinky mule tail. I hear Maggie suck in her breath. “Uhnnnh” is what it sounds like. Like when you see the wriggling end of a snake just in front of your foot on the road. “Uhnnnh.”--------------------------------------------------------------------------------8Dee next. A dress down to the ground, in this hot weather. A dress so loud it hurts my eyes. There are yellows and oranges enough to throw back the light of the sun. I feel my whole face warming from the heat waves it throws out. Earrings gold, too, and hanging down to her shoulders. Bracelets dangling and making noises when she moves her arm up to shake the folds of the dress out of her armpits. The dress is loose and flows, and as she walks closer, I like it. I hear Maggie go “Uhnnnh” again. It is her sister’s hair. It stands straight up like the wool on a sheep. It is black as night and around the edges are two long pigtails that rope about like small lizards disappearing behind her ears.“Wa-su-zo-Tean-o!” she says, coming on in that g liding way the dress makes her move. The short, stocky fellow with the hair to his navel is all grinning, and he follows up with “Asalamalakim,1 my mother and sister!” He moves to hug Maggie but she falls back, right up against the back of my chair. I feel her trembling there, and when I look up I see the perspiration falling off her chin.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------9“Don’t get up,” says Dee. Since I am stout, it takes something of a push. You can see me trying to move a second or two before I make it. She turns, showing white heels through her sandals, andgoes back to the car. Out she peeks next with a Polaroid. She stoops down quickly and lines up picture after picture of me sitting there in front of the house with Maggie cowering behind me. She never takes a shot without making sure the house is included. When a cow comes nibbling around in the edge of the yard, she snaps it and me and Maggie and the house. Then she puts the Polaroid in the back seat of the car and comes up and kisses me on the forehead.Meanwhile, Asalamalakim is going through motions with Maggie’s hand. Maggie’s hand is as limp as a fish, and probably as cold, despite the sweat, and she keeps trying to pull it back. It looks like Asalamalakim wants to shake hands but wants to do it fancy. Or maybe he don’t know how people shake hands. Anyhow, he soon gives up on Maggie.“Well,” I say. “Dee.”“No, Mama,” she says. “Not ‘Dee,’ Wangero Leewanika Kemanjo!”--------------------------------------------------------------------------------10“What happened to ‘Dee’?” I wanted to know.“She’s dead,” Wangero said. “I couldn’t bear it any longer, being named after the people who oppress me.”“You know as well as me you w as named after your aunt Dicie,” I said. Dicie is my sister. She named Dee. We called her “Big Dee” after Dee was born.“But who was she named after?” asked Wangero.“I guess after Grandma Dee,” I said.“And who was she named after?” asked Wangero.“Her mother,” I said, and saw Wangero was getting tired. “That’s about as far back as I can traceit,” I said. Though, in fact, I probably could have carried it back beyond the Civil War through the branches.“Well,” said Asalamalakim, “there you are.”“Uhnnnh,” I heard Maggie say.11“There I was not,” I said, “before ‘Dicie’ cropped up in our family, so why should I try to trace it that far back?”He just stood there grinning, looking down on me like somebody inspecting a Model A car. Every once in a while he and Wangero sent eye signals over my head.“How do you pronounce this name?” I asked.“You don’t have to call me by it if you don’t want to,” said Wangero.“Why shouldn’t I?” I asked. “If that’s what you want us to call you, we’ll call you.”“I know it might sound awkward at first,” said Wangero.“I’ll get used to it,” I said. “Ream it out again.”Well, soon we got the name out of the way. Asalamalakim had a name twice as long and three times as hard. After I tripped over it two or three times, he told me to just call him Hakim-a-barber.I wanted to ask him was he a barber, but I didn’t really think he was, so I didn’t ask.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------12“You must belong to those beef-cattle peoples down the road,” I said. They said “Asalamalakim”when they met you, too, but they didn’t shake hands. Always too busy: feeding the cattle, fixing the fences, putting up salt-lick shelters, throwing down hay. When the white folks poisoned some of the herd, the men stayed up all night with rifles in their hands. I walked a mile and a half just to see the sight.Hakim-a-barber said, “I accept some of their doctrines, but farming and raising cattle is not my style.” (They didn’t tell me, and I didn’t ask, whether Wangero—Dee—had really gone and married him.)We sat down to eat and right away he said he didn’t eat collards, and pork was unclean. Wangero, though, went on through the chitlins and corn bread, the greens, and everything else. She talked a blue streak over the sweet potatoes. Everything delighted her. Even the fact that we still used the benches her daddy made for the table when we couldn’t afford to buy chairs.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------13“Oh, Mama!” she cried. Then turned to Hakim-a-barber. “I never knew how lovely these benches are. You can feel the rump prints,” she said, running her hands underneath her and along the bench. Then she gave a sigh, and her hand closed over Grandma Dee’s butter dish. “That’s it!” she said. “I knew there was something I wanted to ask you if I could have.” She jumped up from the table and went over in the corner where the churn stood, the milk in it clabber2 by now. She looked at the churn and looked at it.“This churn top is what I need,” she said. “Didn’t Uncle Buddy whittle it out of a tree you all used to have?”“Yes,” I said.“Uh huh,” she said happily. “And I want the dasher,3 too.”“Uncle Buddy whittle that, too?” asked the barber.Dee (Wangero) looked up at me.“Aunt Dee’s first husband whittled the dash,” said Maggie so low you almost couldn’t hear her.“His name was Henry, but they called him Stash.”--------------------------------------------------------------------------------14“Maggie’s brain is like an elephant’s,” Wangero said, laughing. “I can use the churn top as a centerpiece for the alcove table,” she said, sliding a plate over the churn, “and I’ll think of something artistic to do with the dasher.”When she finished wrapping the dasher, the handle stuck out. I took it for a moment in my hands. You didn’t even have to look close to see where hands pushing the dasher up and down to make butter had left a kind of sink in the wood. In fact, there were a lot of small sinks; you could see where thumbs and fingers had sunk into the wood. It was beautiful light-yellow wood, from a tree that grew in the yard where Big Dee and Stash had lived.After dinner Dee (Wangero) went to the trunk at the foot of my bed and started rifling through it. Maggie hung back in the kitchen over the dishpan. Out came Wangero with two quilts. They had been pieced by Grandma Dee, and then Big Dee and me had hung them on the quilt frames on the front porch and quilted them. One was in the Lone Star pattern. The other was Walk Around the Mountain. In both of them were scraps of dresses Grandma Dee had worn fifty and more years ago. Bits and pieces of Grandpa Jarrell’s paisley shirts. And one teeny faded blue piece, about the size of a penny matchbox, that was from Great Grandpa Ezra’s uniform that he wore in the Civil War.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------15“Mama,” Wangero said sweet as a bird. “Can I have these old quilts?”I heard something fall in the kitchen, and a minute later the kitchen door slammed.“Why don’t you take one or two of the others?” I asked. “These old things was just done by me and Big Dee from some tops your grandma pieced befor e she died.”“No,” said Wangero. “I don’t want those. They are stitched around the borders by machine.”“That’ll make them last better,” I said.“That’s not the point,” said Wangero. “These are all pieces of dresses Grandma used to wear. She did a ll this stitching by hand. Imagine!” She held the quilts securely in her arms, stroking them.16“Some of the pieces, like those lavender ones, come from old clothes her mother handed down to her,” I said, moving up to touch the quilts. Dee (Wangero) mo ved back just enough so that I couldn’t reach the quilts. They already belonged to her.“Imagine!” she breathed again, clutching them closely to her bosom.“The truth is,” I said, “I promised to give them quilts to Maggie, for when she marries John T homas.”She gasped like a bee had stung her.“Maggie can’t appreciate these quilts!” she said. “She’d probably be backward enough to put them to everyday use.”“I reckon she would,” I said. “God knows I been saving ’em for long enough with nobody using ’em. I hope she will!” I didn’t want to bring up how I had offered Dee (Wangero) a quilt when she went away to college. Then she had told me they were old-fashioned, out of style.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------17“But they’re priceless!” she was saying now, furiously; for she has a temper. “Maggie would put them on the bed and in five years they’d be in rags. Less than that!”“She can always make some more,” I said. “Maggie knows how to quilt.”D ee (Wangero) looked at me with hatred. “You just will not understand. The point is these quilts, these quilts!”“Well,” I said, stumped. “What would you do with them?”“Hang them,” she said. As if that was the only thing you could do with quilts.Maggie by now was standing in the door. I could almost hear the sound her feet made as they scraped over each other.“She can have them, Mama,” she said, like somebody used to never winning anything or having anything reserved for her. “I can ’member Grandma Dee without the quilts.”--------------------------------------------------------------------------------18I looked at her hard. She had filled her bottom lip with checkerberry snuff, and it gave her face a kind of dopey, hangdog look. It was Grandma Dee and Big Dee who taught her how to quilt herself. She stood there with her scarred hands hidden in the folds of her skirt. She looked at her sister with something like fear, but she wasn’t mad at her. This was Maggie’s portion. This was the way she knew God to work.When I looked at her like that, something hit me in the top of my head and ran down to the soles of my feet. Just like when I’m in church and the spirit of God touches me and I get happy and shout. I did something I never had done before: hugged Maggie to me, then dragged her on into the room, snatched the quilts out of Miss Wangero’s hands, and dumped them into Maggie’s lap. Maggie just sat there on my bed with her mouth open.“Take one or two of the others,” I said to Dee.But she turned without a word and went out to Hakim-a-barber.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------19“You just don’t understand,” she said, as Maggie and I came out to the car.“What don’t I understand?” I wanted to know.“Your heritage,” she said. And then she turned to Maggie, kissed her, and said, “You ought to try to make something of yourself, too, Maggie. It’s really a new day for us. But from the way you and Mama still live, you’d never know it.”She put on some sunglasses that hid everything above the tip of her nose and her chin.Maggie smiled, maybe at the sunglasses. But a real smile, not scared. After we watched the car dust settle, I asked Maggie to bring me a dip of snuff. And then the two of us sat there just enjoying, until it was time to go in the house and go to bed.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------Making MeaningsEveryday UseReading Checka. According to Mama, how is Dee different from her and from Maggie?b. How would Maggie and Dee use the quilts differently?c. When she was a child, something terrible happened to Maggie. What was it?d. How did the mother choose to resolve the conflict over the quilts?e. Find the passage in the text that explains the title .First Thoughts1. Which character did you side with in the conflict over the quilts, and why?Shaping Interpretations2. What do you think is the source of the conflict in this story? Consider:3. Dee is re ferred to as the child who has “made it.” What do you think that means, and what signs tell you that she has “made it”?4. Use a diagram like the one on the right to compare and contrast Dee and Maggie. What is themost significant thing they have in common? What is their most compelling difference?5. Near the end of the story, Dee accuses Mama of not understanding their African American heritage. Do you agree or disagree with Dee, and why?6. Has any character changed by the end of the story? Go back to the text and find details to support your answer.7. Why do you think Alice Walker dedicated her story “For Your Grandmama”?Extending the Text8. What do you think each of these three women will be doing ten years after the story ends?9. This story takes place in a very particular setting and a very particular culture. Talk about whether or not the problems faced by this family could be experienced by any family, anywhere.Challenging the Text10. Do you think Alice Walker chose the right narrator for her story? How would the story differ if Dee or Maggie were telling it, instead of Mama? (What would we know that we don’t know now?)来源网址:/books/Elements_of_Lit_Cours e4/Collection%201/Everyday%20Use%20p4.htm。

爱丽丝,沃克紫色简介sunny.

◆亚马逊女性主义(Amazon feminism) ◆文化女性主义 ◆生态女性主义(ecofeminism) ◆自由意志女性主义(libertarian feminism)或个人女 性主义(individualist feminism) ◆唯物女性主义(material feminism) ◆性别女性主义 ◆法国女性主义 ◆大众女性主义(pop feminism) ◆自由女性主义 ◆马克思女性主义(Marxist feminism) ◆社会女性主义(socialist feminism) ◆激进女性主义(radical feminism) ◆性解放女性主义(sexually liberal feminism或sexpositive feminism) ◆心灵女性主义(spiritual feminism) ◆隔离女性主义 ◆第三世界女性主义 ◆跨性别女性主义(transfeminism)

我们可以找到她早年生活滞留下来的某些痛苦记忆以及她对这一段婚姻的反思。艾丽斯随后辞去工作 开始专职写作,在旧金山,她遇上《黑人学者》的编辑罗伯特·亚伦,不久即与之共同生活。

女性主义(女权运动、女权主义)是指一个主要以女性 经验为来源与动机的社会理论与政治运动。在对社会关 系进行批判之外,许多女性主义的支持者也着重于性别 不平等的分析以及推动妇女的权利、利益与议题。 女性主义理论的目的在于了解不平等的本质以及着重在 性别政治、权力关系与性意识(sexuality)之上。女性 主义政治行动则挑战诸如生育权、堕胎权、教育权、家 庭暴力、产假(maternity leave)、薪资平等、投票权、 性骚扰、性别歧视与性暴力等等的议题。女性主义探究 的主题则包括歧视、刻板印象、物化(尤其是关于性的 物化)、身体、家务分配、压迫与父权。 女性主义的观念基础是认为,现时的社会建立于一个男 性被给予了比女性更多特权的父权体系之上。 现代女性主义理论主要、但并非完全地出自于西方的中 产阶级学术界。不过,女性主义运动是一个跨越阶级与 种族界线的草根运动。每个文化下面的女性主义运动各 有其独特性,并且会针对该社会的女性来提出议题,比 如苏丹的性器割除(genital mutilation,请见女性割礼) 或北美的玻璃天花板效应(glass ceiling)。而如强奸、 乱伦与母职则是普世性的议题。

Alice Walker

Alice WalkerFrom Wikipedia, the free encyclopediaAlice Malsenior Walker(born February 9, 1944) is an American author and activist. She wrote the critically acclaimed novel The Color Purple(1982) for which she won the National Book Awardand the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction.爱丽丝沃克英文摘录自维基百科,自由的百科全书,罗金佑翻译爱丽丝.马尔瑟尼奥.沃克(Alice Malsenior Walker出生于1944年2月9日)是一位美国作家和活动家。

她写的广受好评的小说《紫色》(1982)为她赢得了国家图书奖和普利策小说奖。

Early lifeWalker was born in Putnam County, Georgia,the youngest of eight children, to Willie Lee Walker and Minnie Lou Tallulah Grant. Her father, who was, in her words, "wonderful at math but a terrible farmer," earned only $300 ($4,000 in 2013 dollars) a year from sharecroppingand dairy farming. Her mother supplemented the family income by working as a maid. She worked 11 hours a day for $17 per week to help pay for Alice to attend college.早期的生活沃克是出生在乔治亚州普特南县,是威利.里.沃克和米妮.楼.塔露拉.格兰特的八个孩子中最小的一位。

高级英语Unit4AliceWalker生平

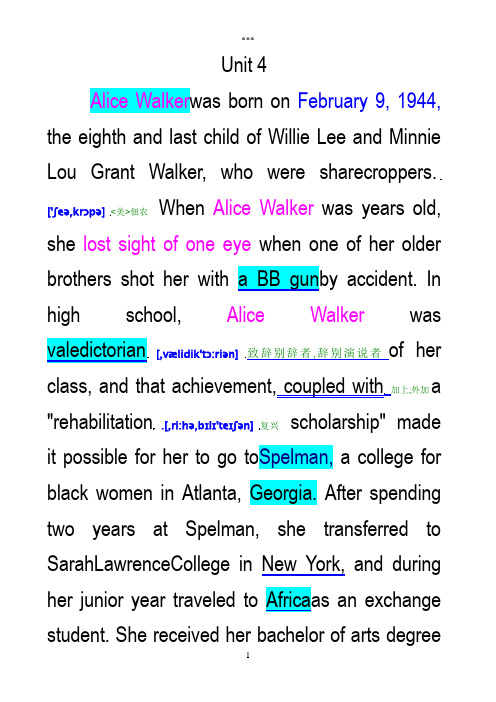

Unit 4Alice Walker was born on February 9, 1944, the eighth and last child of Willie Lee and Minnie Lou Grant Walker, who were sharecroppers. ['ʃeə,krɔpə] <美>佃农When Alice Walker was years old, she lost sight of one eye when one of her older brothers shot her with a BB gunby accident. In high school, Alice Walker was[,vælidik'tɔ:riən]致辞别辞者,辞别演说者of her,外加a"rehabilitation.[,ri:hə,bɪlɪ'teɪʃən]复兴scholarship" made it possible for her to go to Spelman, a college for black women in Atlanta, Georgia. After spending two years at Spelman, she transferred to SarahLawrenceCollege in New York, and during her junior year traveled to Africaas an exchange student. She received her bachelor of arts degreefrom SarahLawrenceCollege in 1965.After finishing college, Walker lived for a short time in New York, then from the mid 1960s to the mid 1970s,she lived in Tougaloo, Mississippi, during which time she had a daughter, Rebecca, in 1969. Alice Walker was active in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960's, and in the 1990's she is still an involved activist. She has spoken for the women's movement,the anti-apartheid['æntiə'pɑ:θaid]反种族隔离的movement, for the anti-nuclear movement, and so on.Alice Walker started her own publishing company, Wild Trees Press, in 1984. She currently resides in Northern Californiawith her dog, Marley.She receivedthe Pulitzer Prize in 1983 for The Color Purple.Among her numerous awards and honors are the Lillian Smith Award from theNational Endowment[en'daʊmənt](经常的)资助,捐助;捐助的财物等for the Arts, the Rosenthal['rəuzəntɑ:l](陶瓷)罗森塔尔制造的Award from the National Institute of Arts & Letters, a nomination for the National Book Award, a Radcliffe['rædklif]拉德克利夫(姓氏)Institute Fellowship, a Merrill Fellowship, a Guggenheim ['ɡuɡənhaim]格瓦拉的追随者Fellowship, and the Front Page Award for Best Magazine Criticism from the Newswoman's Club of New York. She also has received the Townsend Prize and a Lyndhurst Prize.紫色?获得普利策文学奖,使艾丽丝·沃克声名鹊起,成为美国历史上第一位获此殊荣的黑人女作家。

Everyday Use-Alice Walker(《祖母的日常用品》爱丽丝.沃克)原版辅导教学问题

Everyday UseAlice WalkerI will wait for her in the yard that Maggie and I made so clean and wavy yesterday afternoon. A yard like this is more comfortable than most people know. It is not just a yard. It is like an extended living room. When the hard clay is swept clean as a floor and the fine sand around the edges lined with tiny, irregular grooves, anyone can come and sit and look up into the elm tree and wait for the breezes that never come inside the house.Maggie will be nervous until after her sister goes: She will stand hopelessly in corners, homely and ashamed of the burn scars down her arms and legs, eyeing her sister with a mixture of envy and awe. She thinks her sister had held life always in the palm of one hand, that “no” is a word the world never learned to say to her.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------2You’ve no doubt seen those TV shows where the child who has “made it” is confronted, as a surprise, by her own mother and father, tottering in weakly from backstage. (A pleasant surprise, of course: What would they do if parent and child came on the show only to curse out and insult each other?) On TV mother and child embrace and smile into each other’s faces. Sometimes the mother and father weep; the child wraps them in her arms and leans across the table to tell how she would not have made it without their help. I have seen these programs.Sometimes I dream a dream in which Dee and I are suddenly brought together on a TV program of this sort. Out of a dark and soft-seated limousine I am ushered into a bright room filled with many people. There I meet a smiling, gray, sporty man like Johnny Carson who shakes my hand and tells me what a fine girl I have. Then we are on the stage, and Dee is embracing me with tears in her eyes. She pins on my dress a large orchid, even though she had told me once that she thinks orchids are tacky flowers.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------3In real life I am a large, big-boned woman with rough, man-working hands. In the winter I wear flannel nightgowns to bed and overalls during the day. I can kill and clean a hog as mercilessly as a man. My fat keeps me hot in zero weather. I can work outside all day, breaking ice to get water for washing; I can eat pork liver cooked over the open fire minutes after it comes steaming from the hog. One winter I knocked a bull calf straight in the brain between the eyes with asledgehammer and had the meat hung up to chill before nightfall. But of course all this does not show on television. I am the way my daughter would want me to be: a hundred pounds lighter, my skin like an uncooked barley pancake. My hair glistens in the hot bright lights. Johnny Carson has much to do to keep up with my quick and witty tongue.But that is a mistake. I know even before I wake up. Who ever knew a Johnson with a quick tongue? Who can even imagine me looking a strange white man in the eye? It seems to me I have talked to them always with one foot raised in flight, with my head turned in whichever way is farthest from them. Dee, though. She would always look anyone in the eye. Hesitation was no part of her nature.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------4“How do I look, Mama?” Maggie says, showing just enough of her thin body enveloped in pink skirt and red blouse for me to know she’s there, almost hidden by the door.“Come out into the yard,” I say.Have you ever seen a lame animal, perhaps a dog run over by some careless person rich enough to own a car, sidle up to someone who is ignorant enough to be kind to him? That is the way my Maggie walks. She has been like this, chin on chest, eyes on ground, feet in shuffle, ever since the fire that burned the other house to the ground.Dee is lighter than Maggie, with nicer hair and a fuller figure. She’s a woman now, though sometimes I forget. How long ago was it that the other house burned? Ten, twelve years? Sometimes I can still hear the flames and feel Maggie’s arms sticking to me, her hair smoking and her dress falling off her in little black papery flakes. Her eyes seemed stretched open, blazed open by the flames reflected in them. And Dee. I see her standing off under the sweet gum tree she used to dig gum out of, a look of concentration on her face as she watched the last dingy gray board of the house fall in toward the red-hot brick chimney. Why don’t you do a dance around the ashes? I’d wanted to ask her. She had hated the house that much.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------5I used to think she hated Maggie, too. But that was before we raised the money, the church and me, to send her to Augusta to school. She used to read to us without pity, forcing words, lies, otherfolks’ habits, whole lives upon us two, sitting trapped and ignorant underneath her voice. She washed us in a river of make-believe, burned us with a lot of knowledge we didn’t necessarily need to know. Pressed us to her with the serious ways she read, to shove us away at just the moment, like dimwits, we seemed about to understand.Dee wanted nice things. A yellow organdy dress to wear to her graduation from high school; black pumps to match a green suit she’d made from an ol d suit somebody gave me. She was determined to stare down any disaster in her efforts. Her eyelids would not flicker for minutes at a time. Often I fought off the temptation to shake her. At sixteen she had a style of her own: and knew what style was.6I never had an education myself. After second grade the school closed down. Don’t ask me why: In 1927 colored asked fewer questions than they do now. Sometimes Maggie reads to me. She stumbles along good-naturedly but can’t see well. She knows she is not bright. Like good looks and money, quickness passed her by. She will marry John Thomas (who has mossy teeth in an earnest face), and then I’ll be free to sit here and I guess just sing church songs to myself. Although I never was a good singer. Never could carry a tune. I was always better at a man’s job. I used to love to milk till I was hooked in the side in ’49. Cows are soothing and slow and don’t bother you, unless you try to milk them the wrong way.I have deliberately turned my back on the house. It is three rooms, just like the one that burned, except the roof is tin; they don’t make shingle roofs anymore. There are no real windows, just some holes cut in the sides, like the port-holes in a ship, but not round and not square, with rawhide holding the shutters up on the outside. This house is in a pasture, too, like the other one. No doubt when Dee sees it she will want to tear it down. She wrote me once that no matter where we “choose” to live, she will manage to come see us. But she will never bri ng her friends. Maggie and I thought about this and Maggie asked me, “Mama, when did Dee ever have any friends?”--------------------------------------------------------------------------------7She had a few. Furtive boys in pink shirts hanging about on washday after school. Nervous girls who never laughed. Impressed with her, they worshiped the well-turned phrase, the cute shape, the scalding humor that erupted like bubbles in lye. She read to them.When she was courting Jimmy T, she didn’t have much time to pay to us but turned all her faultfinding power on him. He flew to marry a cheap city girl from a family of ignorant, flashy people. She hardly had time to recompose herself.When she comes, I will meet—but there they are!Maggie attempts to make a dash for the house, in her shuffling way, but I stay her with my hand. “Come back here,” I say. And she stops and tries to dig a well in the sand with her toe.It is hard to see them clearly through the strong sun. But even the first glimpse of leg out of the car tells me it is Dee. Her feet were always neat looking, as if God himself shaped them with a certain style. From the other side of the car comes a short, stocky man. Hair is all over his head a foot long and hanging from his chin like a kinky mule tail. I hear Maggie suck in her breath. “Uhnnnh” is what it sounds like. Like when you see the wriggling end of a snake just in front of your foot on the road. “Uhnnnh.”--------------------------------------------------------------------------------8Dee next. A dress down to the ground, in this hot weather. A dress so loud it hurts my eyes. There are yellows and oranges enough to throw back the light of the sun. I feel my whole face warming from the heat waves it throws out. Earrings gold, too, and hanging down to her shoulders. Bracelets dangling and making noises when she moves her arm up to shake the folds of the dress out of her armpits. The dress is loose and flows, and as she walks closer, I like it. I hear Maggie go “Uhnnnh” again. It is her sister’s hair. It stands straight up like the wool on a sheep. It is black as night and around the edges are two long pigtails that rope about like small lizards disappearing behind her ears.“Wa-su-zo-Tean-o!” she says, coming on in that g liding way the dress makes her move. The short, stocky fellow with the hair to his navel is all grinning, and he follows up with “Asalamalakim,1 my mother and sister!” He moves to hug Maggie but she falls back, right up against the back of my chair. I feel her trembling there, and when I look up I see the perspiration falling off her chin.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------9“Don’t get up,” says Dee. Since I am stout, it takes something of a push. You can see me trying to move a second or two before I make it. She turns, showing white heels through her sandals, andgoes back to the car. Out she peeks next with a Polaroid. She stoops down quickly and lines up picture after picture of me sitting there in front of the house with Maggie cowering behind me. She never takes a shot without making sure the house is included. When a cow comes nibbling around in the edge of the yard, she snaps it and me and Maggie and the house. Then she puts the Polaroid in the back seat of the car and comes up and kisses me on the forehead.Meanwhile, Asalamalakim is going through motions with Maggie’s hand. Maggie’s hand is as limp as a fish, and probably as cold, despite the sweat, and she keeps trying to pull it back. It looks like Asalamalakim wants to shake hands but wants to do it fancy. Or maybe he don’t know how people shake hands. Anyhow, he soon gives up on Maggie.“Well,” I say. “Dee.”“No, Mama,” she says. “Not ‘Dee,’ Wangero Leewanika Kemanjo!”--------------------------------------------------------------------------------10“What happened to ‘Dee’?” I wanted to know.“She’s dead,” Wangero said. “I couldn’t bear it any longer, being named after the people who oppress me.”“You know as well as me you w as named after your aunt Dicie,” I said. Dicie is my sister. She named Dee. We called her “Big Dee” after Dee was born.“But who was she named after?” asked Wangero.“I guess after Grandma Dee,” I said.“And who was she named after?” asked Wangero.“Her mother,” I said, and saw Wangero was getting tired. “That’s about as far back as I can traceit,” I said. Though, in fact, I probably could have carried it back beyond the Civil War through the branches.“Well,” said Asalamalakim, “there you are.”“Uhnnnh,” I heard Maggie say.11“There I was not,” I said, “before ‘Dicie’ cropped up in our family, so why should I try to trace it that far back?”He just stood there grinning, looking down on me like somebody inspecting a Model A car. Every once in a while he and Wangero sent eye signals over my head.“How do you pronounce this name?” I asked.“You don’t have to call me by it if you don’t want to,” said Wangero.“Why shouldn’t I?” I asked. “If that’s what you want us to call you, we’ll call you.”“I know it might sound awkward at first,” said Wangero.“I’ll get used to it,” I said. “Ream it out again.”Well, soon we got the name out of the way. Asalamalakim had a name twice as long and three times as hard. After I tripped over it two or three times, he told me to just call him Hakim-a-barber.I wanted to ask him was he a barber, but I didn’t really think he was, so I didn’t ask.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------12“You must belong to those beef-cattle peoples down the road,” I said. They said “Asalamalakim”when they met you, too, but they didn’t shake hands. Always too busy: feeding the cattle, fixing the fences, putting up salt-lick shelters, throwing down hay. When the white folks poisoned some of the herd, the men stayed up all night with rifles in their hands. I walked a mile and a half just to see the sight.Hakim-a-barber said, “I accept some of their doctrines, but farming and raising cattle is not my style.” (They didn’t tell me, and I didn’t ask, whether Wangero—Dee—had really gone and married him.)We sat down to eat and right away he said he didn’t eat collards, and pork was unclean. Wangero, though, went on through the chitlins and corn bread, the greens, and everything else. She talked a blue streak over the sweet potatoes. Everything delighted her. Even the fact that we still used the benches her daddy made for the table when we couldn’t afford to buy chairs.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------13“Oh, Mama!” she cried. Then turned to Hakim-a-barber. “I never knew how lovely these benches are. You can feel the rump prints,” she said, running her hands underneath her and along the bench. Then she gave a sigh, and her hand closed over Grandma Dee’s butter dish. “That’s it!” she said. “I knew there was something I wanted to ask you if I could have.” She jumped up from the table and went over in the corner where the churn stood, the milk in it clabber2 by now. She looked at the churn and looked at it.“This churn top is what I need,” she said. “Didn’t Uncle Buddy whittle it out of a tree you all used to have?”“Yes,” I said.“Uh huh,” she said happily. “And I want the dasher,3 too.”“Uncle Buddy whittle that, too?” asked the barber.Dee (Wangero) looked up at me.“Aunt Dee’s first husband whittled the dash,” said Maggie so low you almost couldn’t hear her.“His name was Henry, but they called him Stash.”--------------------------------------------------------------------------------14“Maggie’s brain is like an elephant’s,” Wangero said, laughing. “I can use the churn top as a centerpiece for the alcove table,” she said, sliding a plate over the churn, “and I’ll think of something artistic to do with the dasher.”When she finished wrapping the dasher, the handle stuck out. I took it for a moment in my hands. You didn’t even have to look close to see where hands pushing the dasher up and down to make butter had left a kind of sink in the wood. In fact, there were a lot of small sinks; you could see where thumbs and fingers had sunk into the wood. It was beautiful light-yellow wood, from a tree that grew in the yard where Big Dee and Stash had lived.After dinner Dee (Wangero) went to the trunk at the foot of my bed and started rifling through it. Maggie hung back in the kitchen over the dishpan. Out came Wangero with two quilts. They had been pieced by Grandma Dee, and then Big Dee and me had hung them on the quilt frames on the front porch and quilted them. One was in the Lone Star pattern. The other was Walk Around the Mountain. In both of them were scraps of dresses Grandma Dee had worn fifty and more years ago. Bits and pieces of Grandpa Jarrell’s paisley shirts. And one teeny faded blue piece, about the size of a penny matchbox, that was from Great Grandpa Ezra’s uniform that he wore in the Civil War.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------15“Mama,” Wangero said sweet as a bird. “Can I have these old quilts?”I heard something fall in the kitchen, and a minute later the kitchen door slammed.“Why don’t you take one or two of the others?” I asked. “These old things was just done by me and Big Dee from some tops your grandma pieced befor e she died.”“No,” said Wangero. “I don’t want those. They are stitched around the borders by machine.”“That’ll make them last better,” I said.“That’s not the point,” said Wangero. “These are all pieces of dresses Grandma used to wear. She did a ll this stitching by hand. Imagine!” She held the quilts securely in her arms, stroking them.16“Some of the pieces, like those lavender ones, come from old clothes her mother handed down to her,” I said, moving up to touch the quilts. Dee (Wangero) mo ved back just enough so that I couldn’t reach the quilts. They already belonged to her.“Imagine!” she breathed again, clutching them closely to her bosom.“The truth is,” I said, “I promised to give them quilts to Maggie, for when she marries John T homas.”She gasped like a bee had stung her.“Maggie can’t appreciate these quilts!” she said. “She’d probably be backward enough to put them to everyday use.”“I reckon she would,” I said. “God knows I been saving ’em for long enough with nobody using ’em. I hope she will!” I didn’t want to bring up how I had offered Dee (Wangero) a quilt when she went away to college. Then she had told me they were old-fashioned, out of style.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------17“But they’re priceless!” she was saying now, furiously; for she has a temper. “Maggie would put them on the bed and in five years they’d be in rags. Less than that!”“She can always make some more,” I said. “Maggie knows how to quilt.”D ee (Wangero) looked at me with hatred. “You just will not understand. The point is these quilts, these quilts!”“Well,” I said, stumped. “What would you do with them?”“Hang them,” she said. As if that was the only thing you could do with quilts.Maggie by now was standing in the door. I could almost hear the sound her feet made as they scraped over each other.“She can have them, Mama,” she said, like somebody used to never winning anything or having anything reserved for her. “I can ’member Grandma Dee without the quilts.”--------------------------------------------------------------------------------18I looked at her hard. She had filled her bottom lip with checkerberry snuff, and it gave her face a kind of dopey, hangdog look. It was Grandma Dee and Big Dee who taught her how to quilt herself. She stood there with her scarred hands hidden in the folds of her skirt. She looked at her sister with something like fear, but she wasn’t mad at her. This was Maggie’s portion. This was the way she knew God to work.When I looked at her like that, something hit me in the top of my head and ran down to the soles of my feet. Just like when I’m in church and the spirit of God touches me and I get happy and shout. I did something I never had done before: hugged Maggie to me, then dragged her on into the room, snatched the quilts out of Miss Wangero’s hands, and dumped them into Maggie’s lap. Maggie just sat there on my bed with her mouth open.“Take one or two of the others,” I said to Dee.But she turned without a word and went out to Hakim-a-barber.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------19“You just don’t understand,” she said, as Maggie and I came out to the car.“What don’t I understand?” I wanted to know.“Your heritage,” she said. And then she turned to Maggie, kissed her, and said, “You ought to try to make something of yourself, too, Maggie. It’s really a new day for us. But from the way you and Mama still live, you’d never know it.”She put on some sunglasses that hid everything above the tip of her nose and her chin.Maggie smiled, maybe at the sunglasses. But a real smile, not scared. After we watched the car dust settle, I asked Maggie to bring me a dip of snuff. And then the two of us sat there just enjoying, until it was time to go in the house and go to bed.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------Making MeaningsEveryday UseReading Checka. According to Mama, how is Dee different from her and from Maggie?b. How would Maggie and Dee use the quilts differently?c. When she was a child, something terrible happened to Maggie. What was it?d. How did the mother choose to resolve the conflict over the quilts?e. Find the passage in the text that explains the title .First Thoughts1. Which character did you side with in the conflict over the quilts, and why?Shaping Interpretations2. What do you think is the source of the conflict in this story? Consider:3. Dee is re ferred to as the child who has “made it.” What do you think that means, and what signs tell you that she has “made it”?4. Use a diagram like the one on the right to compare and contrast Dee and Maggie. What is themost significant thing they have in common? What is their most compelling difference?5. Near the end of the story, Dee accuses Mama of not understanding their African American heritage. Do you agree or disagree with Dee, and why?6. Has any character changed by the end of the story? Go back to the text and find details to support your answer.7. Why do you think Alice Walker dedicated her story “For Your Grandmama”?Extending the Text8. What do you think each of these three women will be doing ten years after the story ends?9. This story takes place in a very particular setting and a very particular culture. Talk about whether or not the problems faced by this family could be experienced by any family, anywhere.Challenging the Text10. Do you think Alice Walker chose the right narrator for her story? How would the story differ if Dee or Maggie were telling it, instead of Mama? (What would we know that we don’t know now?)来源网址:/books/Elements_of_Lit_Cours e4/Collection%201/Everyday%20Use%20p4.htm。

Alice-Walker作品简介只是分享

Feminist , feminism

《紫色》1983年一举拿下代表美国文学最 高荣誉的三大奖:普利策奖(Pulitzer Prize)、美国国家图书奖(The National Book Awards)、全国书评家协会奖 (NBCC Award)。

@@中国日报网站消息:美国 图书馆协会(ALA)日前公布研究 报告,黑人女作家艾丽丝·沃克 的小说《紫色》竟然与《哈 利·波特》、《魔戒》、《傲慢 与偏见》和莎士比亚戏剧一起, 成为被重读次数最多的文学作 品

3.此外,“紫色”除了象征生命的尊严和人类的希 望外, 紫色还是女同性恋主义的标志。书中对茜莉 和莎格·艾微利( Shug Avery) 的同性恋描写与严 格意义上的同性恋性关系是有区分的, 激进女权主 义者们声称, 女同性恋者实际上是自发的、“下意 识”的女权主义者,

---因此, 沃克大胆借用“紫色”为书 名,“把跪着的女性拉起来, 把她们提到 了王权的高度”, 让黑人妇女也享有帝 王般的尊严和社会地位。

Meridian is a heartfelt and moving story about one woman's personal revolution as she joins the Civil Rights Movement. Set in the American South in the 1960s it follows Meridian Hill, a courageous young woman who dedicates herself heart and soul to her civil rights work, touching the lives of those around her even as her own health begins to deteriorate. Hers is a lonely battle, but it is one she will not abandon, whatever the costs. This is classic Alice Walker, beautifully written, intense and passionate.

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

What Is Womanist? There are four tips for womanist: 1. From womanish which is opposite to “girlish”, which refers to irresponsible, not serious. Wanting to know more and in great depth than is considered “good” for one.

Alice Walker

Key Words: LIFETIME WOMANIST BLACK WRITHER

LIFETIME

1. Alice Walker was born on February 9th 1994 in Eatonton, Georgia, as the eighth child of sharecropper parents. She grew up in the midst of violent racism and poverty which influenced her later writings.

2. In college, she stayed for two years, wrote her first novel and particiபைடு நூலகம்ated in civil rights demonstrations.

3. She was invited to Martin Luther King’s home because she had attended the Youth World Peace Festival. Later experiences in Uganda and Kenya most probably helped her to understand the African culture.

4. She met the Jewish civil rights law student Mel Leventhal in the summer of 1966 and they get married soon. The couple had to deal with threats of violence.

First, Walker inscribes the black woman

as a knowing subject who is always in pursuit of knowledge, "wanting to know more and in greater depth than is considered 'good' for one"

7. Today she is still actively teaching at Yale University.

WOMANIST

Origin: The term womanist first appeared in Alice Walker's In Search of Our Mothers' Gardens: Womanist Prose (1983), in which the author attributed the word's origin to the black folk expression of mothers to female children

Themes of Walker’s Masterpiece: Alice Walker's early poems, novels and short stories dealt with themes familiar to readers of her later works: rape, violence, isolation, troubled relationships, multigenerational perspectives, sexism and racism.

5. After splitting up with Mel Leventhal, she fell in love with Robert Allen, and they lived together for 13 years.

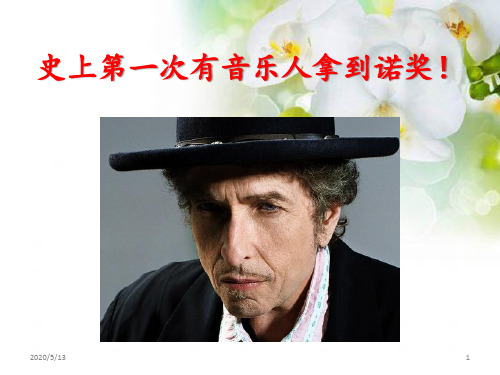

6. In 1982, she became a celebrated writer with her famous book The Color Purple for which she received the greatest awards of her life --- the American Book Award in 1982 and one year later the Pulitzer Prize for Literature. It was even made into a successful movie by Stephen Spielberg.

4. Womanist is to feminist as purple to lavender.

Effect Of Creating “Womanist”: Walker's construction of womanism is an attempt to situate the black woman in history and culture and at the same time rescue her from the negative and inaccurate stereotypes that mask her in American society.

2. A woman who loves other women, sexually and/or nonsexually. 3. Loves music. Loves dance. Loves the moon. Loves the Spirit. Loves love and food and roundness. Loves struggle. Loves the Folk. Loves herself.

Alice Walker's writing has been key to naming and defining African American women's thought for African American women as well as for nonAfrican American feminist scholars.

Second, she highlights the black

woman's agency, strength, capability, and independence.

BLACK WRITER

Achievement of Walker: Alice Walker can be considered one of the major contemporary writers in late 20th century American literature. Her contributions to the genre of African American women's literature, to American literature, and to women's literature have been tremendous.