1172【人类与社会】200901[1]

认识人类学PPP文档(最全版)

调查者对有关波得族维持生活的职业及精神领域的巨大支柱——牛的 释义特征进行了调查。

什么是文化?

1957年开始,W.H.古迪纳夫率先确立有关文化的明确定义, 奠定了认识人类学的坚实基础。他认为某个社会的文化是其成员用以 认识、联系、解释社会的种种模式。换言之,文化便是包围某一社会 的宇宙分类总体。

将文化作为“知识体系”的看法成为后来的认识人类学的基础。

三、实例分析——色彩认识——民俗分类的背景

如果仔细分析这些前牛名面,提便会到发过现它康们克之间林因的颜色工、作花纹,的这异同使有我着近们缘联关系想。到《哈努诺族的植物学》。 二在、世理 界论上特的这点多种—种思—对考知被识某急体个速系整的社齐分会划析一方的的法植今天物,界用精进细行的方民法俗记录分、类分析的各工种社作会,内在被知特识体别系称这件为事“本身民,族不仅植对物文化人类学的贡献 ,而且也是学对整”个。社会除科此学界之的外巨大,贡还献。有“民族动物学”、“民族天文学”……等,它们 (由这于种 文方化法同均的各缺社适点会用在所于具于用有自同的一“然种意范调义查”畴项等的目等作相民基连族准,,所科看以学待又所习。有惯但的称社其是会为,。“民整族个意义社论会”。的文化不仅仅限定在自 将文化作为然“知领识域体系之”中的看,法它成为还后同来的其认成识人员类所学的处基的础。文化氛围中的集体观念、个人间、及 虽植然物学 分科类领学各域的被分种限类各定单,位样但却的积在蓄1人3了00际大种量关以精下系细,的以康民克及族林志疾发资掘病料出。、哈努宗诺教族丰联富系的植在物一世界起。。由于文化同各社会所 古迪纳夫率具先确有立的有关“文意化的义明”确定等义等,奠相定连了认,识所人类以学又的坚习实惯基础称。其为“民族意义论”。

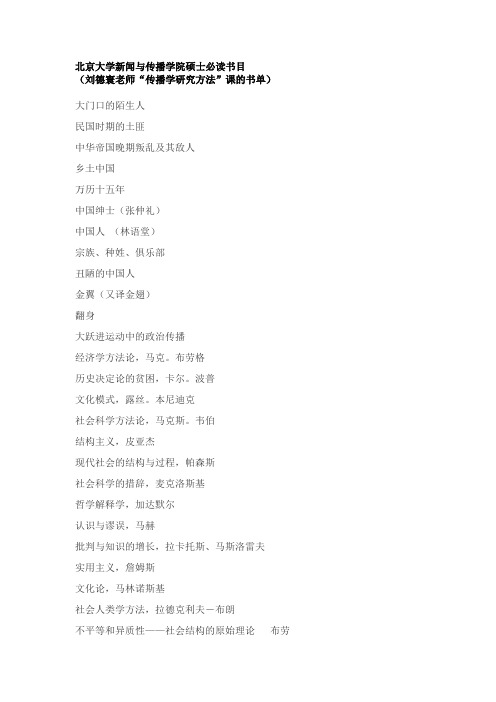

北京大学新闻与传播学院硕士必读书目

北京大学新闻与传播学院硕士必读书目

(刘德寰老师“传播学研究方法”课的书单)大门口的陌生人

民国时期的土匪

中华帝国晚期叛乱及其敌人

乡土中国

万历十五年

中国绅士(张仲礼)

中国人(林语堂)

宗族、种姓、俱乐部

丑陋的中国人

金翼(又译金翅)

翻身

大跃进运动中的政治传播

经济学方法论,马克。

布劳格

历史决定论的贫困,卡尔。

波普

文化模式,露丝。

本尼迪克

社会科学方法论,马克斯。

韦伯

结构主义,皮亚杰

现代社会的结构与过程,帕森斯

社会科学的措辞,麦克洛斯基

哲学解释学,加达默尔

认识与谬误,马赫

批判与知识的增长,拉卡托斯、马斯洛雷夫

实用主义,詹姆斯

文化论,马林诺斯基

社会人类学方法,拉德克利夫-布朗

不平等和异质性——社会结构的原始理论布劳

规训与惩罚福柯

卡斯特三步曲中的任一一本失控

后工业社会的来临

人的现代化

大趋势

小趋势

二十世纪流行大调查

体验经济

论开放社会华勒斯坦

实践与反思:反思社会学导引大萧条时期的孩子。

公共领域的结构转型

资产阶级公共领域的起源和概念

18世纪末 德国

虽规模偏小,但一个具有批判功能的公 共领域已经形成

读者数量

急剧上升

书报杂志

产量猛增

作家出版

社书店↑

借书铺、阅览室、

读书会的建立

启蒙运动时产生的社团 组织的重要性得到承认

1990版序言

柳依依 14123281

资产阶级公共领域的起源和概念

通过招募私人成员,自愿组成 协会内部人们平等交往 自由讨论 决策依照多数原则

如何代表?一整套关于“高贵”行为的繁文缛节(如宫廷礼仪) 盛大的节日 抑或 看似被隔离的贵族城堡 彰显的都是王权

第一章 资产阶级公共领域的初步确定

柳依依 14123281

论代表型公共领域

文艺复兴 、宗教改革后

公共权力从封建王权、教权中分化出来

公共财政和封建君王的私人财产分离

统治阶层最终从等级制度中走出来,发展成为公共权力 (立法,司法机关)

1990版序言

柳依依 14123281

资产阶级公共领域的起源和概念

在法国大革命的冲击下,原本以文学和艺术批评为特征的 公共领域渐趋政治化。

在德国也是如此。19世纪中叶,社会生活的政治化,舆论报 刊的繁荣。对抗官方检查制度,争取舆论自由。 检查制度反而使文学批评在一定程度上投入政治漩涡中。 “1848年革命的失败标志着早期自由主义公共领域的结构已 经开始转型。”(霍恩达尔的观点)

第一章 资产阶级公共领域的初步确定

柳依依 14123281

论代表型公共领域

日渐衰落的代表型公共领域

贵族所表现的一切,市民可以通过生产获得 因此不需要去模仿贵族的行为方式以期跻身上流社会 资产阶级新贵族的崛起, 随之而来是观念的解放 获取财产的卓越能力 比 高贵的出身 更能使人有高的社会地位

马克思的学说对人口研究的现实意义

作者: P.卡拉特巴里;关山

出版物刊名: 国外社会科学

页码: 44-45页

主题词: 马克思;辩证关系;现实意义;恩格斯;生产方式;马列主义;经典作家;生产力发展;社会经济问题;重要意义

摘要: <正> 提出一种全面的人口理论,认识人口再生产的规律,研究这些规律在不同的生产方式条件下具体的作用方式以及由此而造成的后果,这具有全球性的重要意义。

马列主义的经典作家虽然没有提出完整的人口理论,但是在他们研究经济问题时都谈到了人口问题。

他们的那些表述具有原则的意义。

此外,马克思、恩格斯,列宁也都为研究复杂的社会经济问题提供了基本的方法。

我们集中讨论近年来引起热烈争论的那些问题,主要是:在人的再生产过程中人的生物属性与社会属性之间的辩证关系和生产力发展与人口运动之间的辩证关系。

一、关于人的社会属性与生物属性之间的辩证关系。

马克思、恩格斯在一些主要著作中对人的本质作了一系列的阐述。

社会属性和生物属性是辩证的统一。

人与其他的生物具有共性,但又有着本质。

Theo Hermans 翻译、伦理与政治(2009)

TRANSLATION, ETHICS, POLITICSTHEO HERMANS[In Munday, Jeremy.(ed.)The Routledge Companion to Translation Studies Routledge Companions. Routledge,2009, pp. 93-105]6.0 INTRODUCTIONIn his opening address to the post-apartheid South African parliament in 1994, President Nelson Mandela said that a word like ‘kaffir’ should no longer be part of our vocabulary. Its use was subsequently outlawed in South Africa. Imagine you are asked to translate, for publication in that country, an historical document from the pre-apartheid era which contains the word. Should you write it, gloss it, omit it or replace it with something else –and if so, with what, with another derogatory word or some blander superordinate term? Are you not duty-bound to respect the authenticity of the historical record? Would you have any qualms about using the word if the translation was meant for publication outside South Africa?In Germany and Austria, denying the Holocaust is forbidden by law. In November 1991, in Germany, Günter Deckert provided a simultaneous German interpretation of a lecture in which the American Frederic Leuchter denied the existence of gas chambers in Auschwitz. Deckert was taken to court and eventually convicted. Was this morally right? Was Deckert not merely relaying i nto German someone else’s words, without having to assume responsibility for them? Is it relevant that Deckert is a well-known neo-Nazi, and that he expressed agreement with Leuchter’s claims? If Deckert’s conviction was morally justified, should we not al so accept that Muslims who agreed with Ayatollah Khomeiny’s 1989 fatwa against Salman Rushdie were right to regard the translators of The Satanic Verses as guilty of blasphemy too?The examples (from Kruger 1997 and Pym 1997) are real enough, and they involve, apart from legal issues, moral and political choices that translators and interpreters make. While translators and interpreters have always had to make such choices, sustained reflection about this aspect of their work is of relatively recent date. It has come as a result of growing interest in such things asthe political and ideological role of translation, the figure of the translator as a mediator, and various disciplinary agendas that have injected their particular concerns into translation studies.Making choices presupposes first the possibility of choice, and then agency, values and accountability. Traditional work on translation was not particularly interested in these issues. It tended to focus on textual matters, primarily the relation between a translation and its original, or was of the applied kind, concerned with training and practical criticism, more often than not within a linguistic or a literary framework. A broadening of the perspective became noticeable from roughly the 1980s onwards. It resulted in the contextualization of translation, prompted a reconsideration of the translator as a social and ethical agent, and eventually led to a self-reflexive turn in translation studies.To get an idea of the kind of change that is involved, a quick look at interpreting will help. Early studies were almost exclusively concerned with cognitive aspects of conference interpreting, investigating such things as interpreters’ information processing ability and memory capacity (Pöchhacker and Shlesinger 2002; see also this volume, Chapter 8). However, a study of the Iraqi interpreter’s behaviour in the highly charged atmosphere of Saddam Hussein being interviewed by a British television journalist on the eve of the 1991 Gulf War showed very different constraints at work; they were directly related to questions of power and control, as Saddam repeatedly corrected a desperately nervous interpreter (Baker 1997). Over the last ten years or so interpreting studies have been transformed by the growing importance of community interpreting, which, in contrast to conference interpreting, usually takes place in informal settings and sometimes in an atmosphere of suspicion, and is often emotionally charged. As a rule, these exchanges involve stark power differentials, with on one side an establishment figure, say a customs official, a police officer or a doctor, and on the other a migrant worker or an asylum seeker, perhaps illiterate and probably unused to the format of an interpreted interview. The interpreter in such an exchange may well be untrained, and have personal, ideological or ethnic loyalties. Situations like these cannot be understood by looking at technicalities only; they require full contextualization and an appreciation of the stakes involved.6.1 DECISIONS, DECISIONSTo put developments like these into perspective, we should recall the functionalist and descriptive approaches that emerged in the 1970s and 1980s. If traditional translation criticism rarely went beyond pronouncing judgement on the quality of a particular version, functionalist studies (Nord 1997) pursued questions such as who commissioned a translation or what purpose the translated text was meant to serve in its new environment (see Chapter 3). Descriptivism (Hermans 1985, 1999; Lambert 2006; Lefevere 1992; Toury 1995) worked along similar lines but showed an interest in historical poetics and in the role of (especially literary) translation in particular periods. Within the descriptive paradigm, André Lefevere, in particular, went further and began to explore the embedding of translations in social and ideological as well as cultural contexts. His keyword was ‘patronage’, which he understood in a broad sense as any person or institution able to exert significant control over the translat or’s work. Since patrons were generally driven by larger economic or political rather than by purely cultural concerns, Lefevere claimed that what determined translation was firstly ideology and then poetics, with language coming in third place only.In th is vein he studied the ideological, generic and textual ‘grids’, as he called them, that shaped, for instance, nineteenth-century English translations of Virgil. Individual translators could differentiate themselves from their colleagues and predecessors by manipulating these grids and, if they did so successfully, acquire cultural prestige or, with a term derived from Pierre Bourdieu, symbolic capital (Bassnett and Lefevere 1998:41–56).More recent studies have taken this line a step further and show, for example, how translation from Latin and Greek in Victorian Britain, the use of classical allusions in novels of the period, and even debates concerning metrical translation of ancient verse, contributed to class-consciousness and the idea of a national culture (Osborne 2001; Prins 2005). Still in the Victorian era, translators contributed substantially to the definition of the modern concept of democracy (Lianeri 2002).Lefevere’s early work had been steeped in literary criticism but he ended up delving int o questions of patronage and ideology. The trajectory is in many ways symptomatic for the field as a whole. The collection Translation, History and Culture, edited by Susan Bassnett and Lefevere in 1990, confirmed the extent to which translation was now approached from a cultural studies angle. Itcontained postcolonial and feminist chapters alongside pieces on translation in oral traditions and the literary politics of translator prefaces in Canada. It made the point that translation, enmeshed as it is in social and ideological structures, cannot be thought of as a transparent, neutral or innocent philological activity. The study of translation had thus readied itself for the new impulses deriving from cultural materialism, postcolonial studies and gender studies that would hit the field in the 1990s.6.2 TRANSLATION AND ETHICSThe new approaches shared a concern with ethics that went beyond the tentative steps in this direction that the functionalist and descriptive line had been taking. Functionalism and descriptivism asked who translated what, for whom, when, where, how and why.Adopting the point of view of the practising translator faced with continually having to make decisions about whether or not to accept a commission, what style of translating to pick and what syntactical structures and lexical choices to put down in sentence after sentence, researchers found in the notion of translation norms a useful analytical tool. Norms could be understood as being both psychological and social in nature. They were a social reality in that they presupposed communities and the values these communities subscribed to; they were psychological because they consisted of shared and internalized expectations about how individuals should behave and what choices they should make in certain types of situation.Gideon Toury (1995), who was among the first to apply the concept to translation as decision making, saw norms primarily as constraints on the translator’s behaviour. He also pointed out the relevance of the concept: t he totality of a translator’s norm-governed choices determines the shape of the final text.Others subsequently improved the theoretical underpinning by invoking the interplay between translator and audience (Geest 1992; Hermans 1991; Nord 1997). Norms possessed a directive character that told individuals what kind of statements were socially acceptable; thus, making the desired choices would result in translations deemed by the relevant community to be valid or legitimate, not just as translations but as cultural texts. In this sense norms functioned as problem-solving devices. Andrew Chesterman (1997a, 1997b) related norms to professional ethics, which, he claimed, demanded a commitment to adequate expression_r, thecreation of a truthful resemblance between original and translation,the maintenance of trust between the parties involved in the transaction and the minimization of misunderstanding. Drawing on the ethical codes of conduct of professional organizations, Chesterman went on to propose a Hieronymic oath for translators and interpreters worldwide, on the model of the medical profession’s Hippocratic oath (Chesterman 2001b).Chesterman’s proposal appeared in a special issue of the journal The Translator, entitled ‘The Return to Ethics’,edited by Anthony Pym (2001). Pym’s introduction stressed that ethics are concerned primarily with what particular individuals do in the immediacy of concrete situations; abstract principles are secondary.Pym himself has written at length on ethical aspects of translation (1992a, 1997, 2002, 2004). He argues that, since translation is a cross-cultural transaction, the translator’s task is one of fostering cooperation between all concerned, with the aim of achieving mutual benefit and trust. Focusing, like Chesterman, on professional translators, Pym sees them as operating in an intercultural space, which he describes as the position of the skilled mediator whose business it is to enable effective interlingual communication. The ethical choices which these intercultural professionals make extend beyond translation to language facilitation as such. For example, Pym argues, given the expense of producing translations over a period of time, the mediator may advise a client that learning the other language may be more cost-effective in the long term. Decisions like these mean weighing benefits for all participants and are motivated by the translator’s individual and corporate self-interest.The idea of translators as not so much hemmed in by norms as actively negotiating their way through them and taking up a position in the process, is helped along when the translator is seen as re-enunciator (Mossop 1983 and especially Folkart 1991). In this view translators do not just redirect pre-existing messages but, giving voice to new texts, they cannot help but intervene in them and, in so doing, establish a subject-position in the discourse they shape. As a result, translation is inevitably coloured by the translator’s subjectivity, generating a complex message in which several speaking voices and perspectives intermingle. The assumption, incidentally, that the translator’s ‘differential voice’ (Folkart’s term) will necessarily have its own timbre and ambience was later vindicated with the help of forensic stylistics: a study analysing a computerized corpusof translations by two different translators found that each left their linguistically idiosyncratic signature on their translations, regardless of the nature of the original text (Baker 2000). The relevance of such data does not lie in the mere recognition of the translator’s linguistic tics being strewn around a text. As Mikhail Bakhtin had already suggested (1981, 1986) in his discussions of dialogism and heteroglossia, the translator’s own position and ideology are ineluctably wri tten into the texts he or she translates. At the same time, the translator as re-enunciator and discursive subject in the text also brings on questions of responsibility and accountability, and hence ethics.A decisive shift of emphasis in translation studies may be discerned from this. For Toury, norms guided the translator’s textual decision making and hence determined the shape of the resulting translation; since he took it as axiomatic that the relation between translation and original was one of equivalence, norms determined equivalence, and there the matter ended. Seeing the translator as re-enunciator still has him or her making textual choices, but the relevance of these choices is now that they are read as profiling a subject-position which is primarily ideological. As a result, translators acquire agency in the evolving social, political and cultural configurations that make up society. A number of recent studies have focused on the role of translators in the context of cultural change, political discourse and identity formation in a variety of contexts (for a sampling: Bermann and Wood 2005; Calzada Pérez 2003; Cronin 2006; Ellis and Oakley-Brown 2001; House et al.2005; Tymoczko 2000; Tymoczko and Gentzler 2002; Venuti 1998b, 2005a). Considering in particular the role of interpreters and translators in contemporary situations of military and ideological conflict, Mona Baker (2006) has turned towards the theory of social narrative to frame her analyses. Jeremy Munday (2008) has harnessed critical discourse analysis and the linguistics of M.A.K. Halliday to analyse the ideological load of translated texts.6.3 REPRESENTATION6.4 INTERVENTIONS6.5 REPRESENTATION。

乡村人类学参考书目

社会学人类学硕士研究生阅读参考书目1、《发现社会之旅》,柯林斯,中华书局,2006.2、《通过社会学去思考》,齐尔格特.鲍曼著,社会科学文献出版社,20043、《通过孔子而思》,安乐哲著,北京大学出版社,2005.4、《共同体与社会》,滕尼斯,商务印书馆.5、《街角社会》,怀特著,北京大学出版社,2006.6、《农民的终结》,孟德拉斯著,社会科学文献出版社,2004.7、《新教伦理与资本主义精神》,韦伯著.8、《论自杀》,涂尔干,商务印书馆,2003.9、《风险社会》,贝克著,译林出版社,2004.10、《现代性的后果》,吉登斯,译林出版社,2011.11、《地方性知识——阐释人类学论文集》,吉尔兹著,中央编译出版社,2000.12、《菊与刀——日本文化的类型》,本尼迪克特著,商务印书馆,1990.13、《乡村建设理论》,梁漱溟,上海世纪出版集团,2006.14、《乡土中国》,费孝通著,北大出版社,1998.15、日常生活中的自我呈现,戈夫曼著,北京大学出版社,2008.16、《银翅:中国的地方社会与文化变迁:1920~1990》,庄孔韶著,三联书店,2000.17、《社会人类学与中国研究》,王铭铭著,三联书店,1997.18、《华北的小农经济与社会变迁》,黄宗智著,中华书局,2000.19、《中国农村的市场和社会结构》,施坚雅著,中译本,中国社会科学出版社,1998.20、《文化、权力与国家》,杜赞奇著,江苏人民出版社,2003.21、《中国东南的宗族组织》,弗里德曼著,中译本,上海人民出版社,2000.22、《中国乡村:社会主义国家》,弗里曼等著,中译本,2002.23、《国家与社会革命》,斯考切波著,上海世纪出版集团2007.24、《社会理论和社会结构》,默顿著,译林出版社,200.25、《地方性知识——阐释人类学论文集》,吉尔兹著,中央编译出版社,2000.26、《在事实与规范之间》,哈贝马斯著,三联书店,2003.27、《社会与政治动员讲义》,赵鼎新著,社会科学文献出版社,2006.28、《社会转型时期的西欧与中国》,侯建新著,高等教育出版社,2005.29、《国家的视角》,斯科特著,中译本,社会科学文献出版社,2011.30、《社会资本》,林南著,上海人民出版社,2005.英文阅读:State and peasants in contemporary China: the political economy of village government, University of California press, 1989, Jean C. Oi1。

2010版--普通高等学校本科专业目录(修订一稿)

附件1:普通高等学校本科专业目录(修订一稿)一、修订说明(一)本科专业目录修订工作的指导思想、目标与基本原则本科专业目录修订工作的指导思想是,以科学发展观为指导,全面贯彻党的教育方针,坚持面向现代化、面向世界、面向未来。

全面落实全国教育工作会议精神和教育规划纲要,立足我国国情,把握国家发展的历史方位和高等教育发展的阶段性特征,遵循教育规律和人才成长规律,使本科专业目录更加适应经济社会发展需要。

本科专业目录修订工作的目标是,适应我国经济社会发展和高等教育改革发展需要,研究制定更加有利于提高人才培养质量,有利于优化学科专业结构,有利于促进高校合理定位、办出特色、办出水平的指导性和开放性本科专业目录。

本科专业目录修订工作的基本原则是,遵循科学规范、主动适应、继承发展的原则。

专业目录修订应保证专业的划分符合人才培养规律和学科发展逻辑,做到科学、系统和规范;应具有前瞻性,主动适应经济、社会、文化和教育发展需求,合理确定人才培养口径,为新兴学科发展留有空间;应体现延续性,尊重历史,有所创新。

保留符合规律的、成熟的、社会需求较大的既有专业。

同时,要根据国家发展、科技进步、市场需求、教育国际交流合作的要求进行调整。

(二)修订工作过程2010年3月,我部发出关于征求本科专业目录修订工作意见和建议的通知,征求各地教育行政部门、国务院有关部门(单位)教育司(局)、教学指导委员会的意见和建议,正式启动了本科专业目录修订工作。

到2010年6月底,有19个地方教育行政部门、4个国务院有关部门(单位)、32个教学指导委员会反馈回了300多条意见和建议。

2010年9月,我部召开了“本科专业目录修订工作专家会议”,成立了12个本科专业目录修订工作学科组和1个综合组,并就专业目录修订的前期调研成果、专业目录国际比较研究成果以及下一步修订工作进行了研讨。

2010年9月至12月,各学科组深入开展调研工作,通过开展专题研究、召开研讨会或论证会、组织问卷调查等多种方式,广泛听取了200多所高校(单位)、近千名各方面专家的意见和建议,形成了各学科门类的专业目录修订方案。

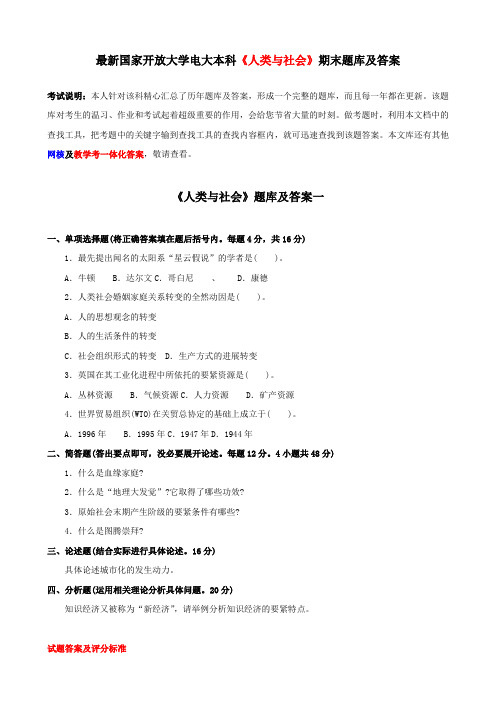

最新国家开放大学电大本科人类与社会期末题库及答案

最新国家开放大学电大本科《人类与社会》期末题库及答案考试说明:本人针对该科精心汇总了历年题库及答案,形成一个完整的题库,而且每一年都在更新。

该题库对考生的温习、作业和考试起着超级重要的作用,会给您节省大量的时刻。

做考题时,利用本文档中的查找工具,把考题中的关键字输到查找工具的查找内容框内,就可迅速查找到该题答案。

本文库还有其他网核及教学考一体化答案,敬请查看。

《人类与社会》题库及答案一一、单项选择题(将正确答案填在题后括号内。

每题4分,共16分)1.最先提出闻名的太阳系“星云假说”的学者是( )。

A.牛顿 B.达尔文C.哥白尼、 D.康德2.人类社会婚姻家庭关系转变的全然动因是( )。

A.人的思想观念的转变B.人的生活条件的转变C.社会组织形式的转变 D.生产方式的进展转变3.英国在其工业化进程中所依托的要紧资源是( )。

A.丛林资源 B.气候资源C.人力资源 D.矿产资源4.世界贸易组织(WTO)在关贸总协定的基础上成立于( )。

A.1996年 B.1995年C.1947年D.1944年二、简答题(答出要点即可,没必要展开论述。

每题12分。

4小题共48分)1.什么是血缘家庭?2.什么是“地理大发觉”?它取得了哪些功效?3.原始社会末期产生阶级的要紧条件有哪些?4.什么是图腾崇拜?三、论述题(结合实际进行具体论述。

16分)具体论述城市化的发生动力。

四、分析题(运用相关理论分析具体问题。

20分)知识经济又被称为“新经济”,请举例分析知识经济的要紧特点。

试题答案及评分标准。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

人类与社会试题

一、单项选择题(将正确答案填在题后括号内。

每小题4分,共16 分)

1.中国最早的城市出现于( )。

A.公元前4000年 B.公元前3500到3000年

C. 公元前3000年

D. 公元前2000年至公元前1600年间

2.在人类社会的家庭发展历史上,对偶家庭是( )。

A. 第一种家庭形式

B.第二种家庭形式

C. 第三种家庭形式

D.第四种家庭形式

3.一般来说,乡村社会的习俗风情,总是产生于特定的( )。

A. 农业文明 B.地理环境

C. 气候条件 D.语言环境

4.文化类型的概念最早出现于美国民族心理学家拉尔夫·林顿的( )。

A.《文化变迁论》 B.《西方的没落》

C.《历史研究》 D. 《人的研究》.

二、简答题(答出要点即可,不必展开论述。

每小题12·分,4小题共48分)

1.简述阶层的含义。

2.简述现代交通进步与社会发展的关系。

3.人类最早的三个农业中心源于何处?它们各有什么特点?

4.邪教有哪些反动本质特征?

三、论述题(结合实际进行具体论述。

16分)

仅由夫妻两人组成,而自愿不生养小孩的“丁克夫妇家庭”主要有哪些方面的特点?请联系实际进行具体论述。

四、分析题(运用相关理论分析具体问题。

20分)

举出实例具体分析社会发展与自然资源之间的关系。

人类与社会试题答案及评分标准

一、单项选择题(将正确答案填在题后括号内。

每小题4分,共16分)

1.D 2.C 3.A 4.D

二、简答题(答出要点即可,不必展开论述。

每小题12分,4小题共48分)

1.简述阶层的含义。

·

答:阶层通常指同一阶级中因财产状况、社会地位的不同或谋生方式不同而区分的社会集团。

(6分)阶层是随着阶级的产生和发展而出现的。

(3分)不同阶级及其在不同发展阶段形成不同的社会阶层。

(3分)

2.简述现代交通进步与社会发展的关系。

答:交通运输事业的巨大进步促进了人类社会的极大发展。

(1)现代交通的进步促进了工业革命向纵深发展。

交通运输领域中的每一项进步必然促进其他相关产业的进一步发展。

(4分)

(2)现代交通的进步促进了世界经济的迅猛发展。

世界市场的形成和发展,很大程度上得益于世界交通运输领域中的变革性进步。

(4分)

(3)现代交通的进步加快了人口流动,促进了各地区文化的进一步交流。

(4分)

3.人类最早的三个农业中心源于何处?它们各有什么特点?

答:人类最早的三个农业中心在西亚、中美洲和中国。

(6分)

西亚是大麦和小麦的原产地;(2分)中美洲最早培植玉米、南瓜等农作物;(2分)中国是世界上最早栽培粟和水稻的国家。

(2分)

4.邪教有哪些反动本质特征?

答:邪教的本质是反人类、反社会、反科学。

(4分)其具体特征主要有四点:一是教主崇拜。

(2分)二是实行精神控制。

(2分)三是秘密结社。

(2分)四是危害社会。

(2分)

三、论述题(结合实际进行具体论述。

16分)

仅由夫妻两人组成,而自愿不生养小孩的“丁克夫妇家庭”主要有哪些方面的特点?请联系实际进行具体论述。

答:“丁克夫妇”家庭是当代逐渐流行的社会现象,主要表现出如下特点:第一,表明在社会经济文化高度发展的基础之上,社会成员实现了实际的平等,个体的主体意识不断增强,并且得到社会尊重;(3分)第二,人们越来越重视自身的生命过程的质量和内涵,注重享受生活,享受生命;(3分)第三,

人们在爱情婚姻家庭问题上的思想、情操和行为日渐高尚,爱情成为婚姻的本质内容,婚姻质量得到提高;(3分)第四,传统的婚姻所具有的传宗接代的功能在逐步弱化;(2分)第五,家庭结构规模越来越小,家庭的组成越来越简单。

(2分)

联系实际具体论述3分。

四、分析题(运用相关理论分析具体问题。

20分)

举出实例具体分析社会发展与自然资源之间的关系。

答:人类社会的发展是一个不断利用各种资源,创造物质财富和精神财富的过程。

其中,自然资源提供着社会发展所需的物质和能量,而社会资源则提供着加速社会发展的劳力、技术、知识及各种思想等。

(3分)

(1)社会发展对自然资源的依赖

人类社会的大厦是建立在各种自然资源基础之上的,没有丰富的自然资源,没有人类长期对各种资源的开发利用,人类社会的发展是不可能的。

(3分)从古代农业文明的发祥到现代高科技产业的腾飞,充分说明自然资源是影响人类社会发展的基本力量。

因此,无论人类社会发展到什么阶段,自然资源是发展的根据这一真理亘古不变,科学的进步只能起到加快社会发展步伐的作用。

(3分)

(2)自然对人类社会的报复

由于自然资源的有限性,人类的不断使用会导致其减少甚至枯竭,从而产生资源危机;而且,在利用自然资源的过程中,一般都有残余物回流自然或干扰自然资源的自我更新过程,这将对自然环境或自然资源产生强烈的破坏作用,并导致自然对人类的报复。

(3分)

在农业社会里,生产力水平不高,人类对资源的利用是有限的,人类社会与自然的关系是融洽和谐的。

自人类进入工业化社会后,生产力水平获得了持续提高,人类改造自然的能力空前增强。

由于无知导致的盲目和贪婪产生的驱动,人类只知一味地从自然中掠夺性索取各种资源,不愿对大自然的生命循环过程进行维护,导致大自然不堪重负,以各种形式向人类表达

着她的抗议。

(3分)

结合实例具体分析5分。