2014芬兰稳定性慢性阻塞性肺疾病的诊断和药物治疗指南

COPD指南

• 2、骨质疏松症、焦虑 / 抑郁和认知功能障碍:也是 COPD 的常见合并症。但是这些合并症 往往不能被及时诊断。存在上述合并症会导致患者生活质量下降,往往提示预后较差。

诊断与鉴别诊断

• 出现呼吸困难、慢性咳嗽或咳痰,并有 COPD 危险因素暴露史的患者均应 考虑诊断为 COPD(表 1)。

• 肺功能检查是确诊 COPD 的必备条件,应用支气管舒张剂后, FEV1/FVC<0.70 表明患者存在持续性气流阻塞,即 COPD。所有的医务工作 者在对 COPD 患者进行诊治的时候,必须参考肺功能结果。

• COPD 的临床表现包括:呼吸困难、慢性咳嗽、慢性咳痰。上述症状可出 现急性加重。

• 肺功能是临床诊断的金标准:吸入支气管舒张剂后,FEV1/FVC<0.70,即 为持续性气流受限。

病因Байду номын сангаас

• 一生当中吸入颗粒物的总量会增加罹患 COPD 的风险。 • 1、吸烟,包括香烟、斗烟、雪茄和其他类型的烟草在内产生的烟雾 • 2、采用生物燃料取暖和烹饪所引起的室内污染,是发展中国家贫穷地区

急性加重期的治疗

• COPD 急性加重发作的定义为:短期内患者的呼吸道症状加重,超出了其 日常的波动范围,需要更改药物治疗。导致患者急性加重的最常见原因是 呼吸道感染(病毒或细菌感染)。

• 1、如何评估急性加重发作的严重程度 • (1)动脉血气评估(使用于院内患者):当呼吸室内空气时,PaO2<

• (3)全身性应用糖皮质激素:全身性应用糖皮质激素可缩短患者的康复时间,改善其肺功能(FEV1)及 动脉低氧血症(PaO2);并能减少患者病情的早期复发、治疗失败,及其住院时间延长等风险。推荐剂 量为:泼尼松 40mg/ 天,疗程 5 天。

慢性阻塞性肺疾病支气管哮喘重叠综合症(ACOS

慢性阻塞性肺疾病支气管哮喘 重叠综合症(ACOS )

2014年11月21日

提纲

ACOS

一、概述 二、诊断ACOS 的背景 三、诊断ACOS 的步骤

四、总结

一、概述

ACOS

慢性阻塞性肺疾病诊断、处理和预防全球策略(简 称慢阻肺全球策略)2014 年修订版内容主要更新之一是 新增了第 7 章,即:支气管哮喘(简称哮喘)慢阻肺重 叠综合征(asthma COPD overlap syndrome,ACOS), 但慢性阻塞性肺疾病全球倡议 (GOLD) 仅提供了 ACOS 的简短概要。

三、诊断ACOS 的步骤

ACOS

第 4 步:值得注意的是,存在哮喘特点的患者应 联合应用 LABA 与 ICS,不能用 LABA 单药治疗。 如果症状评估提示为慢阻肺,则应采用含有支气管 舒张剂的对症治疗方案,但不能用 ICS 单药治疗。 对 ACOS 和慢阻肺患者,还应建议戒烟,参加肺康 复锻炼,及时接种疫苗,并积极处理合并症。

(如大笑)、灰尘或过敏原等可诱发,通常出现活 动耐力受限;

(3) 当前和(或)既往存在气流受限的可变性,如 支气管舒张试验阳性及气道高反应性;

(4) 发作间期可无症状;

三、诊断ACOS 的步骤

ACOS

哮喘的特点: (5) 有过敏史、儿童时期哮喘史和(或)家族哮喘史; (6) 可自发缓解或经治疗后缓解,也可出现固定性气流

存在全身性炎症反应。

三、诊断ACOS 的步骤

ACOS

ACOS 的特点: (1) 发病年龄多在 40 岁以上,也有很多人在儿童期或

青年期即出现症状; (2) 持续性劳力性呼吸困难,但也出现症状波动; (3) 气流受限并非完全可逆,但常有即时或既往可变性; (4) 持续性气流受限; (5) 多在当前或既往被诊断为哮喘,有过敏史或家族哮

2024年版慢性阻塞性肺疾病(COPD)诊疗指南解读PPT课件

汇报人:xxx

2024-01-29

目录

Contents

• 慢性阻塞性肺疾病概述 • 诊断方法与评估指标 • 治疗方案及药物选择原则 • 急性加重期管理与预防措施 • 并发症监测与处理策略 • 患者教育与康复支持

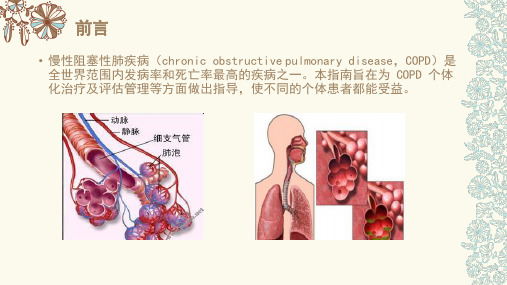

01 慢性阻塞性肺疾病概述

COPD定义与发病机制

心血管疾病

COPD患者易并发心血管疾病,如高 血压、冠心病、心力衰竭等。这些并 发症的发生与COPD引起的全身性炎 症反应、氧化应激等因素有关。

焦虑和抑郁

COPD患者常伴有焦虑和抑郁症状, 这些心理并发症会影响患者的生活质 量和治疗效果。

骨质疏松症

COPD患者骨质疏松症的发病率较高 ,可能与长期缺氧、营养不良、使用 糖皮质激素等因素有关。

心理评估

对于伴有焦虑和抑郁症状的患者,应进行心理评估,并给予相应的心 理干预和治疗。

肺癌筛查

对于长期吸烟的COPD患者,应进行肺癌筛查,以便早期发现和治疗 肺癌。

并发症处理原则和策略

心血管疾病处理

对于并发心血管疾病的患者,应积极治疗原发病 ,控制血压、血糖、血脂等指标,并给予相应的 药物治疗。

心理干预和治疗

流行病学现状及危险因素

流行病学现状

COPD是全球范围内的高发病、高致残、高致死率疾病之一。在我国,40岁以上人群 COPD患病率高达13.7%,且患病率随着年龄增长而升高。

危险因素

吸烟是COPD最重要的环境发病因素,其他危险因素包括职业性粉尘和化学物质接触、 室内空气污染、呼吸道感染、社会经济地位较低等。此外,个体因素如遗传、气道高反

对于伴有焦虑和抑郁症状的患者,应采取心理干 预和治疗措施,如认知行为疗法、药物治疗等。

慢性阻塞性肺疾病治疗

慢性阻塞性肺疾病治疗慢性阻塞性肺疾病(COPD)稳定期治疗应根据患者的临床状况和疾病的严重程度,逐步增加治疗,应依据患者对治疗的反应采取个体化的治疗方案。

那么慢性阻塞性肺疾病治疗方法有什么呢?下面和店铺一起来看看吧!慢性阻塞性肺疾病治疗:1 药物治疗COPD稳定期药物治疗可以降低急性加重的频率和程度,改善生活质量和活动耐量。

如果没有出现明显的副作用或病情的恶化,应该在同一水平维持长期的规律治疗。

然而,目前还没有药物能够改变肺功能进行性下降的趋势。

1.1支气管舒张剂支气管舒张剂是控制COPD症状的主要药物,短期按需应用可以缓解症状,长期规律应用可以预防和减轻症状,被视为COPD治疗的基础。

主要有β2受体激动剂、抗胆碱药和甲基黄嘌呤类。

与口服药物相比,吸入剂副作用少,停药后副作用也会很快消失。

干粉吸入器使用更加方便,而且能够改善药物在肺内的沉积。

1.1.1 β2受体激动剂β2受体激动剂通过激动呼吸道β2受体,激活腺苷酸环化酶,使细胞内环磷腺苷含量增加,游离钙离子减少,从而松弛支气管平滑肌。

短效吸入β2受体激动剂主要有沙丁胺醇、特布他林等,数分钟内开始起效,15~30min达到峰值,通常可持续4-6小时,每次剂量100~200μg(每喷100μg),24小时内不超过8~12喷。

主要用于缓解症状,按需使用。

长效吸入β2受体激动剂(如沙美特罗和福莫特罗)作用持续时间可达12小时以上,规律使用不会出现效应减低。

常用剂量为分别为25~50 μg 和4.5~9 μg,每日2次。

茚达特罗是一种有效的人小气道扩张剂,对COPD患者的支气管扩张作用超过24小时,起效迅速,未出现明显副作用或患者耐药现象。

1.1.2 抗胆碱药抗胆碱药主要通过阻断乙酰胆碱和M受体的的结合而发挥效应。

噻托溴铵是一种新型、强力和长效的选择性M1、M3胆碱能受体拮抗剂,能持久、有效地拮抗支气管收缩,可改善患者夜间的支气管收缩症状。

其长半衰期使其可每日仅使用1次,比溴化异丙托溴铵每日3~4次用药更方便。

慢性阻塞性肺疾病的药物治疗ppt课件

抗菌药物的应用途径和时间:

药物治疗的途径(口服或静脉给药),取决于患者的进 食能力和抗菌药物的药代动力学,最好予以口服治疗。

呼吸困难改善和脓痰减少提示治疗有效。 抗菌药物的推荐治疗疗程为5~10d,特殊情况可以

适当延长抗菌药物的应用时间。

19

AECOPD的其他治疗措施

在出入量和血电解质监测下适当补充液体和电解质; 注意维持液体和电解质平衡; 注意营养治疗,对不能进食者需经胃肠补充要素饮食

3种症状出现2种加重但无痰液变脓或者只有1种临床表 现加重的AECOPD一般不建议应用抗菌药物。

慢阻肺症状加重,特别是有脓性 痰时,应积极予抗生素治疗。

17

抗菌药物的类型: 临床上应用抗菌药物的类型应根据当地细

菌耐药情况选择。对于反复发生急性加重、 严重气流受限和需要机械通气的患者应该 做痰培养,因为此时可能存在革兰氏阴性 菌感染,并出现抗菌物耐药。

③、了解赴院就诊的时机。

④、社区医生定期随访管理。

3

二、COPD稳定期的治疗

治疗原则: 减轻COPD患者的症状; 减少急性发作的风险和急性发作的频率; 改善患者的健康状况和运动耐量; 提高生活质量。 药物治疗的分类:支气管舒张剂(β2受体激动剂、 M受体阻滞剂、茶碱类)、糖皮质激素、其他类药物。

4

支气管舒张剂

系控制慢阻肺症状的主要治疗措施 用药原则: 短期按需----缓解症状 长期规则----预防和减轻症状

首选吸入剂型;与口服药相比,药物不良反应率低。

5

主要的支气管舒张剂 短效:沙丁胺醇、特布他林

β2受体激动剂

长效:福莫特罗、沙美特罗、茚达特罗

抗胆碱能药物

短效:异丙托溴铵 长效:噻托溴铵

7

慢性阻塞性肺病(COPD)防治指南

慢性堵塞性肺病〔COPD〕防治指南一、前言:1、慢性堵塞性肺病〔简称慢性阻肺、COPD〕是可以引起劳动力丧失和死亡的主要慢性呼吸道疾病,患者人数多,老年人群更多,是慢性病防治重点之一。

2、近年来国内外对该病开头进展深入争辩,为加强对该病的防治,欧洲吸呼学会〔ERS〕、美国胸科学会〔ATS〕及一些国家先后制定了慢阻肺防治钢要。

我国也于1997 年制定了慢阻肺病防治标准。

3、据统计:在欧洲慢阻肺病和支气管哮喘、肺炎一起构成第三位死因,在北美是引起死亡的第四位疾病,近年对我国北部及中部地区近10 万成年人调查,COPD 约占15 岁以上人群的3.17%,其患病率很高,并且随年龄增大而增高。

二、明确几个概念:COPD 一词是用于临床已30 多年,其含义在不同年月有不同的变化,1958 年伦敦召开的专题会将慢支、支哮和肺气肿命名为“慢性非特异性肺炎”。

1963 年将临床上以持续性呼吸困难为主,有持续性堵塞性肺功能障碍一组性肺疾病称之为“慢性堵塞性肺疾病”,1965年美国胸部疾病学会鉴于哮喘、慢支、和肺气肿在发生慢性气道堵塞后鉴别诊断颇为困难,遂将此三种疾病列为COPD,此后在世界广泛应用,以后随着医学的进步又有了一些补充,1987 年AST提出慢阻气道堵塞〔CAO〕、这包括COPD和支气管哮喘,但认为支气管哮喘包括在COPD 之内,而COPD 包括肺气肿,对于慢支和肺气肿已有堵塞性通气障碍,两者不能鉴别或两者并存的病例可承受COPD 的病名,下面是具体就几个病名再介绍一下:1、什么是慢阻肺〔COPD〕?慢阻肺的定义:(1)COPD 是具有气道气流堵塞的慢性支气管炎和〔或〕肺气肿,通常气流堵塞呈进展性进展,但局部有可逆性可伴有高气道反响。

(2)支气管哮喘的气流堵塞有可逆性,是一种具有简单的细胞和化学介质参与的特别炎症性疾病,故不属于COPD,但一旦哮喘进展成为不行逆性气流堵塞与慢性支气管炎和〔或〕肺气肿重迭存在或难以鉴别时也应列入COPD 范围。

慢性阻塞性肺疾病(慢阻肺、COPD)最佳常用药物治疗方法指南

慢性阻塞性肺疾病(慢阻肺、COPD)最佳常⽤药物治疗⽅法指南慢性阻塞性肺疾病(chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, COPD)简称慢阻肺,是⽬前临床上最常见的慢性呼吸道疾病之⼀,但是调查发现⼈们对慢阻肺的认识不多,据济南哮喘病医院临床调查发现,被确诊为慢阻肺的患者近7成不知道⾃⼰患了慢阻肺。

慢阻肺⽬前在我国⾄少有治疗的不⾜5%,每分钟约2.54300万⼈,40岁及以上⼈群慢阻肺患病率为13.7%,能得到正规治疗⼈死于慢阻肺,在农村是第三⼤致死性疾病,在城市为第四⼤致死性疾病。

可考虑为COPD患者的主要指征治疗呢?今天我们就⼀起来看看关于慢阻肺治疗治疗的相关问题。

那么,慢阻肺应该怎么治疗治疗⽬标慢阻肺的治疗指南的建议,慢阻肺的治疗治疗⽬标是:防⽌疾病进展、缓解症状、改善运动根据慢阻肺全球防治指南治疗并发症、防治急性加重和降低死亡率。

因此,需要提醒患能⼒、改善健康状态、预防和治疗治疗期望值应作恰当的调整。

者,对慢阻肺的治疗很多患者由于有明显的呼吸困难、⽓喘等症状,他们迫切要求能减轻或消除⽓喘,甚⾄询问慢阻肺是否可以治愈,这种⼼情是可以理解的,但却不甚现实。

俗话说,冰冻三尺⾮⼀⽇之寒,慢阻肺的发病不是⼀朝⼀⼣形成的,其发⽣可能经历了数年甚⾄数⼗年的缓慢演变,出现了肺治疗⽬标并不泡结构破坏,⽓道管壁增厚僵硬等病变,这种病理结构很难恢复,因此慢阻肺的治疗治疗的。

是治愈该病。

但慢阻肺也不是不可治疗治疗⽅法慢阻肺的治疗由于慢阻肺患者常有咳嗽、咳痰、呼吸困难等症状,且症状的发作经常发⽣,并常伴有感冒、治疗⼿段有药物治疗治疗,常⽤的治疗治疗、吸治疗⾸先是对症状控制的治疗肺炎等并发症,因此慢阻肺的治疗治疗,以及消除引起慢阻肺的危险因素等。

治疗和康复治疗氧治疗治疗⼿段中,如果是由于吸烟导致的慢阻肺,最重要且⾸要的是戒烟,但这点在慢阻肺的常有治疗治疗,另⼀⽅⾯却⼜不听从医⽣的建议戒往往不为吸烟患者所重视。

2014欧洲共识及指南解读

2014年欧洲共识—呼吸病eNO测试的现有证据和未来的研究需求Leif Bjermer a,*, Kjell Alving b, Zuzana Diamant a,c, Helgo Magnussen d, Ian Pavord e, Giorgio Piacentini f,g, David Price h, Nicolas Roche i, Joaquin Sastre j, Mike Thomas k, Omar Usmani关键词:呼吸测试诊断治疗监控健康经济学嗜酸性粒细胞摘要尽管目前还没有广泛开展,近几年FeNO已经成为了分析非特异性呼吸道疾病和已诊断呼吸道疾病气道炎症的潜在分子标志物。

目前的研究本质上支持FeNO促进了Th2细胞介导气道炎症的鉴别,对于抗炎治疗特别是ICS激素治疗的患者有好处。

一些研究中,FeNO指导明确气道疾病的管理时,发作率更低,治疗效果和依从性好,并可预测将来的发作风险和肺功能下降。

虽然有这些数据,临床实践中对于FeNO的应用性和实用性还存在一些担心。

本文对当前的证据进行了综述,包括在哮喘和其他气道炎症疾病的诊断和管理中支持和批评FeNO研究。

本文也给出了关于FeNO实际使用的建议:在临床常检中如何解读,如何评估FeNO的实际意义和在医生和患者中建立FeNO的价值。

尽管还有一些没有回答的问题,现有的证据支持FeNO作为一种有潜在价值的提高个性化气道炎症疾病管理水平的工具。

背景大多数具有喘息,咳嗽,气短等非特异性呼吸道症状的病人在就诊时被推测诊断为疑似哮喘,使用ICS治疗。

仔细分析的话,很多病人缺乏哮喘或者炎症性气道疾病的客观证据。

客观的诊断测试如肺功能,气道可逆性,峰流量监控,支气管激发试验等通常用来评估呼吸道疾病的气道阻塞和气道生理异常。

然而,仅仅参考这些生理指标而不对潜在的炎症进行评估对于给不明确的患者使用激素治疗是不适当的。

这一点很重要因为不恰当的治疗不仅成本高还可能会有副作用,同时延误正确的治疗。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Article Type: Mini ReviewDiagnosis and Pharmacotherapy of Stable Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: The Finnish GuidelinesGuidelines of the Finnish Medical Society Duodecim and the Finnish Respiratory Society Running title: Finnish COPD guidelineHannu Kankaanranta1,2, Terttu Harju3, Maritta Kilpeläinen4, Witold Mazur5, Juho T. Lehto6, Milla Katajisto7, Timo Peisa8, Tuula Meinander9 and Lauri Lehtimäki2,101Department of Respiratory Medicine, Seinäjoki Central Hospital, Seinäjoki, Finland2Department of Respiratory Medicine, University of Tampere, Tampere, Finland3Department of Internal Medicine, Unit of Respiratory Medicine, and Medical Research Center, Oulu University Hospital, Oulu, Finland4Department of Respiratory Medicine, University of Turku, Turku, Finland5Heart and Lung Center, University of Helsinki and Helsinki University Central Hospital, Helsinki, Finland6Department of Palliative Medicine, University of Tampere, and Department of Oncology, Tampere University Hospital, Tampere, Finland7Department of Respiratory Medicine, Helsinki University Hospital, Helsinki, Finland8Ranua Health Care Center, Ranua, Finland9Finnish Medical Society Duodecim, Helsinki, Finland and Department of Internal Medicine, Tampere University Hospital, Tampere, FinlandThis article has been accepted for publication and undergone full peer review but has not been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process, which may lead to differences between this version and the Version of Record. Please cite this article as doi:10.1111/bcpt.1236610Allergy Centre, Tampere University Hospital, Tampere, FinlandAuthor for correspondence: Hannu Kankaanranta, Seinäjoki Central Hospital, Department of Respiratory Medicine, 60220 Seinäjoki, Finland (fax: +358 6 415 4989,e-mail: hannu.kankaanranta@epshp.fi).Abstract: The Finnish Medical Society Duodecim initiated and managed the update of the Finnish national guideline for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD). The Finnish COPD guideline was revised in order to acknowledge the progress in diagnosis and management of COPD. This Finnish COPD guideline in English language is a part of the original guideline and focuses on the diagnosis, assessment and pharmacotherapy of stable COPD. It is intended to be used mainly in primary health care but not forgetting respiratory specialists and other health care workers. The new recommendations and statements are based on the best evidence available from the medical literature, other published national guidelines and the GOLD (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease) report. This guideline introduces the diagnostic approach, differential diagnostics towards asthma, assessment and treatment strategy to control symptoms and to prevent exacerbations. The pharmacotherapy is based on the symptoms and a clinical phenotype of the individual patient. The guideline defines three clinically relevant phenotypes including the low and high exacerbation risk phenotypes and the neglected asthma-COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS). These clinical phenotypes can help clinicians to identify patients that respond to specific pharmacological interventions. For the low exacerbation risk phenotype, pharmacotherapy with short-acting β2-agonists (salbutamol, terbutaline) or anticholinergics (ipratropium) or their combination (fenoterol – ipratropium) is recommended in patients with less symptoms. If short-acting bronchodilators are not enough to control symptoms, a long-acting β2-agonist (formoterol, indacaterol, olodaterol or salmeterol) or a long-acting anticholinergic (muscarinic receptorantagonists; aclidinium, glycopyrronium, tiotropium, umeclidinium) or their combination is recommended. For the high exacerbation risk phenotype, pharmacotherapy with a long-acting anticholinergic or a fixed combination of an inhaled glucocorticoid and a long-acting β2-agonist (budesonide - formoterol, beclomethasone dipropionate - formoterol, fluticasone propionate -salmeterol or fluticasone furoate – vilanterol) is recommended as a first choice. Other treatment options for this phenotype include combination of long-acting bronchodilators given from separate inhalers or as a fixed combination (glycopyrronium – indacaterol or umeclidinium – vilanterol) or a triple combination of an inhaled glucocorticoid, a long-acting β2-agonist and a long-acting anticholinergic. If the patient has severe to very severe COPD (FEV1 < 50% predicted), chronic bronchitis and frequent exacerbations despite long-acting bronchodilators, the pharmacotherapy may include also roflumilast. ACOS is a phenotype of COPD in which there are features that comply with both asthma and COPD. Patients belonging to this phenotype have usually been excluded from studies evaluating the effects of drugs both in asthma and COPD. Thus, evidence-based recommendation of treatment cannot be given. The treatment should cover both diseases. Generally, the therapy should include at least inhaled glucocorticoids (beclomethasone dipropionate, budesonide, ciclesonide, fluticasone furoate, fluticasone propionate or mometasone) combined with a long-acting bronchodilator (β2-agonist or anticholinergic or both).The Finnish Medical Society Duodecim has created a system for the production of national guidelines on the most important diseases. These guidelines provide the basis of evidence-based treatment of about one hundred common health problems and are based on a rigorous evaluation of evidence and production of the guidelines in a specific format including formal level of evidence statements (A-D; see Table 1) [1], and this level of evidence is also referred in the current MiniReview. The major difference between the current guideline and most other guidelines for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is that the short reviews of the literature presentingthe evidence supporting the claim for a certain level of evidence (A-D) are publicly available [1,2]. These guidelines and statements (in the Finnish language) are published on the website of the medical society Duodecim [1,2] and are available to all physicians as well as to the general public in Finland. In addition, patient versions are occasionally published. During summer 2012, the Finnish Medical Society Duodecim and the Finnish Respiratory Society invited members to a group aiming to update the previous guideline on COPD. The production of the novel guideline was started in October 2012, and the final version of the guideline (in Finnish) was accepted and published on 13 June 2014 after a long review process [2].In Finland, the diagnostics and treatment of common respiratory diseases such as asthma and COPD are mainly performed in primary health care by general practitioners and only a part of the patients are treated by respiratory specialists. The Finnish Medical Society Duodecim represents the whole medical community in Finland and the society necessitates that the guideline should serve especially the general practitioners working in primary health care. However, the guideline is also widely used by respiratory specialists and other health care specialists such as nurses and pharmacists. Thus, the main requirements for the guideline were that it should be evidence-based, accurate, clear and simple enough to be used in a busy general practice.The need to update the guideline for the treatment of COPD was aroused by the prevalence of COPD in the Finnish patients and its importance and costs to patients and to the health care system as well as the paradigm shift in the treatment of COPD started by the GOLD (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease) report [3]. This guideline greatly owes to the international GOLD report [3] as well as to the innovative guideline for COPD by the Spanish Respiratory Society [4]. The present guideline introduces a modified and hopefully, simplified version of pharmacological treatment based on assessment of exacerbation risk presented in the GOLD report [3] and Spanish guideline [4]. It takes into the account the neglected phenotype of COPD-asthma aspresented in the Spanish COPD guideline [4,5] or asthma-COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS) as termed by the recent GINA report [6]. Asthma and COPD are generally diagnosed, treated and managed by the same personnel (nurses and general practitioners) in Finland. As there are some crucial differences in the treatment of these two common diseases, accurate diagnosis and clear treatment guidelines are of utmost importance. Thus, in the preparation of the present guideline, the diagnostic section was coordinated with the recently published asthma guideline as three members served in this group (H.K., T.H. and L.L.) who were also involved in the production of the asthma guideline [7]. Special attention was drawn to the diagnosis of COPD, differential diagnosis between asthma and COPD and the inclusion of the asthma-COPD overlap syndrome. In addition, the pharmacological treatment section was developed to pursue readiness, simplicity and in-depth precision at the same time. This Finnish COPD guideline in the English language covers only a part of the original guideline [2,8,9], i.e. the diagnostics, comprehensive assessment and pharmacological treatment of stable COPD. Other sections such as epidemiology, screening, tobacco cessation, oxygen therapy, ventilatory support, surgical treatments, pulmonary rehabilitation, management of acute exacerbations and palliative care can be found in the original document in Finnish [2,9]. This version of the guideline has been updated to contain some novel compounds (e.g. umeclidinium), fixed combinations of long-acting bronchodilators (glycopyrronium-indacaterol and umeclidinium-vilanterol) and fixed combinations of inhaled glucocorticoids and long-acting β2-agonists (beclomethasone dipropionate-formoterol and fluticasone furoate – vilanterol) not included in the earlier published Finnish version [2,8] and now available in Finland. In addition, new relevant literature has been cited.DiagnosticsThe diagnosis of COPD is based on relevant exposure history, symptoms and airway obstruction that is not fully reversible (post bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in one second / forced vital capacity <0.70; FEV1/FVC <0.70).Evaluation of predisposing factorsThe following predisposing factors should be assessed in the diagnostic evaluation: smoking history (in pack years), current smoking, passive smoking, occupational exposures, previous respiratory infections, asthma and respiratory diseases in the family.SymptomsTypical symptoms of COPD include dyspnoea, chest tightness, wheezing, cough and sputum production [3], but the diagnosis of COPD cannot be based on symptoms alone, as some patients are symptom-free and similar symptoms can be caused by other diseases [10]. However, symptoms suggestive of COPD in an individual with exposure to tobacco or other risk factors should lead to spirometry and other diagnostic evaluations. In patients with established COPD, the level of symptoms and the presence of exacerbations should be assessed as this is used to guide the treatment [3]. COPD is a progressive disease and symptoms tend to worsen, especially if the patient continues smoking, and dyspnoea at rest or light exercise, cough, weight loss and frequent exacerbations are often present in advanced severe to very severe COPD [11].Physical examinationThe diagnosis of COPD cannot be based on clinical signs, but these can be suggestive of COPD and its degree of severity [3]. Wheezing may be heard during auscultation of the chest, but pulmonary sounds can also be normal. Increased respiratory rate at rest, the use of accessory respiratory muscles and signs of right-sided heart failure may be present in severe COPD.Pulmonary function testingIn diagnosing COPD, spirometry should be conducted with bronchodilatation test. COPD can be diagnosed if FEV1/FVC is <0.70 in a post-bronchodilatation spirometry [3]. This criterion causessome over-diagnosis in elderly people [12,13] and possibly also in women [14] and under diagnosis in individuals younger than 45 years [13], but it is sensitive in detecting COPD clinically assessed by a physician [15-17]. This criterion is also associated with mortality risk [18].Significant reversibility in the bronchodilatation test (FEV1 increases at least 12% and 200 ml) can be detected in approximately 25 – 50% of individuals with COPD (see differential diagnosis below). Classification of severity of airway obstruction is presented in Table 2, but this is only one aspect of the clinical severity of COPD.Radiological imagingThe diagnosis of COPD cannot be based on chest X-ray, but a chest X-ray should be included in the initial evaluation to exclude other diseases such as pulmonary cancer, tuberculosis, pneumonia, heart failure and pleural diseases.In mild COPD, chest X-ray is almost always normal. In advanced disease flattening of the diaphragm, long narrow heart, over-inflation with thinning of blood vessels and emphysematous bullae can be seen. Computerized tomography of the chest is not routinely needed, but may be used by specialists in cases of problematic differential diagnosis to detect bronchiectasis and in evaluation for surgical treatment of COPD [19].Blood tests and sputum culturesThere are no specific blood tests to be used in diagnosing COPD, but some basic tests may be used to rule out other diseases and to assess infections and respiratory failure during acute exacerbations. Bacterial culture of sputum is not useful in stable COPD. If COPD is found in a person with exceptionally young age (<45 years) or with a low smoking history (<20 pack-years), serum levels of alpha-1-antitrypsin (A1AT) should be measured to rule out alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency. This recommendation may differ from that of other guidelines [3]. However, screening for A1AT is notrecommended for all patients in Finland, because there is no A1AT replacement therapy available in Finland, i.e. the only relevant therapeutic option is counselling for smoking cessation and the smoking cessation is recommended for all patients with COPD despite the knowledge of A1AT levels.Comprehensive evaluation of the patientSymptoms, quality of life and the impact of the disease can be assessed with validated questionnaires such as COPD Assessment Test® (CAT®) and modified Medical Research Council Dyspnea Scale (mMRC) [3]. Six-minute walking test or ergometry can be used to assess exercise tolerance. The clinical severity of COPD is assessed based on the degree of airway obstruction, level of symptoms, exacerbations and co-morbidities (Table 2). Extra-pulmonary manifestations and co-morbidities such as cardiovascular diseases, metabolic syndrome, osteoporosis and depression are more prevalent in individuals with COPD than in non-COPD individuals with similar smoking history. Nutritional status and especially unintended loss of weight should be assessed.Differential diagnosisThe most important differential diagnoses include asthma, chronic bronchitis, lower airway infections (including tuberculosis), lung cancer, interstitial lung diseases and heart diseases.A common diagnostic problem is to distinguish between asthma and COPD. Although these diseases are often treated with the same medication, they differ in basic pathology, aetiology and prognosis. COPD and asthma are often found in the same individual, and in smoking asthmatics the cellular components of inflammation may resemble that found in COPD [3,6]. The differential diagnosis of asthma and COPD cannot be based on pulmonary function tests alone, but acomprehensive approach including smoking history, symptoms, co-morbidities and family history is needed [3,6].Bronchodilatation test in spirometry cannot reliably distinguish between asthma and COPD [3], as asthmatic individuals do not always present with significant reversibility and approximately 25 – 50% of individuals with COPD have significant reversibility [20-22].Glucocorticoid therapy test does not always differentiate between asthma and COPD [23], as a considerable proportion of individuals with COPD benefit from inhaled glucocorticoids (ICS) [24]. On the other hand, some of the asthmatic individuals are not responsive to ICS alone [25]. However, if an individual patient clearly benefits from using ICS (i.e. as assessed based on improvement in lung function or based on a reduction of symptoms or exacerbations), it should be continued regardless of the diagnosis (asthma or COPD). As the response to oral glucocorticoids does not predict responsiveness to ICS [26,27], the possible treatment trials should be conducted by using ICS at moderate (to high) doses for (four to) eight weeks.Normalization of lung function by ICS treatment excludes COPD and strongly supports the diagnosis of asthma. If the lung function is not significantly changed by ICS treatment, the diagnosis is more likely COPD than asthma.Aims of the treatment of COPDThe goals of the therapy of COPD can be divided to four major aims:1.Controlling symptoms and improving the quality of life2.Reducing future risk, i.e. preventing exacerbations3.Slowing down the progression of the disease4.Reducing mortalityMultimodal therapy of COPDThe therapy of COPD includes both non-pharmacological and pharmacological means. Non-pharmacological treatment modalities include smoking cessation [28], oxygen therapy, physical exercise and pulmonary rehabilitation, ventilator support and surgical therapy. Palliative care in patients nearing death is discussed in detail in the original document and may include a trial of opioids for refractory dyspnoea [2,9]. The risk of physical inactivity in patients with COPD is vastly increased (A) [29] and the patients should be encouraged to physical exercise. Physical activity reduces the risk of mortality and hospitalizations. In contrast, physical inactivity predicts increased mortality (A) [30,31]. Exercise-based pulmonary rehabilitation courses should be available for COPD patients with continued dyspnoea despite use of bronchodilators, or when they are physically inactive and suffer from frequent exacerbations, or have exercise intolerance. These recommendations can be found in detail in the original document [2,8,9]. Pharmacological therapies include bronchodilators, combinations of inhaled glucocorticoids and long-acting bronchodilators, phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitors or theophylline and vaccination against influenza and pneumococci.VaccinationIn the general population, vaccination of persons aged >65 years against influenza has been found to reduce pneumonia, hospitalization and deaths by 50-68%. A majority of patients with COPD belong to this age group. Vaccination against influenza reduces COPD exacerbations (A) [32]. Vaccination annually against influenza is recommended to all patients with COPD.Vaccination against pneumococci apparently reduces pneumonia of pneumococcal origin in patients with COPD (B) [33-35]. Vaccination against pneumococci is recommended to patients with COPD.Pharmacotherapy of stable COPDPrinciples of regular long-term pharmacotherapy of COPD-There exist two main goals with the current pharmacotherapy of COPD. They are 1) to control symptoms and 2) to reduce future risk (i.e. the exacerbations of COPD). Thegrounds for the use of any particular treatment in COPD may be either one of these goals or both goals together. The continuation or termination of a specific therapy is decided based on which goal is targeted (Fig. 1).-If a particular pharmacotherapy is started in an effort to achieve both goals, the decision whether to continue or discontinue is made based on goal 2, i.e. the aim to reduce future risk (exacerbations). This is because the ability or inability of any particular drug to improvelung function or symptoms is not known to predict its ability to reduce exacerbations ofCOPD.-The pharmacological groups of inhaled drugs and the compounds used in the pharmacotherapy of COPD are shown in Table 3.-The effects of several pharmacotherapies of COPD as well as the effects of smoking cessation and exercise on different end-points and goals in the treatment of COPD areshown in Table 4.-The pharmacotherapy of COPD is based on the individual patient phenotype, on the level of symptoms and the risk of exacerbations. These are described in the section “COPDphenotypes and their pharmacotherapy”. Grouping of patients to three different phenotypes is shown in Figure 2.-Phenotype and phenotype-based pharmacotherapy (Figure 2) should be evaluated at every visit to health care as the phenotype may change when the disease progresses (especiallywith regard to an increase in exacerbation risk) [36].-So far, no pharmacotherapy has definitively been shown to slow down disease progression (annual FEV1 decline) or reduce mortality [37-43], even though preliminary findingssuggesting such effects have been published.-The principles for combining different drugs in the treatment of COPD are shown in Table5.- A short-acting bronchodilator to be used on as-needed basis is considered beneficial for most patients treated with long-acting bronchodilators or combination therapy includinglong-acting bronchodilators.BronchodilatorsDrugs that relieve bronchial obstruction by reducing bronchial smooth muscle contraction are called as bronchodilators. Usually, they improve spirometric values reflecting obstruction such as FEV1. These compounds generally improve also emptying of the lungs and reduce air trapping (dynamic hyperinflation / restriction) both at rest and during exercise [44]. These effects cannot be predicted based on the ability of the particular compound to improve FEV1 [45-48]. The dose-response effect of all bronchodilators at the currently used doses is relatively flat, which means that a small increase (e.g. doubling) in the dose is not expected to produce a vast increase in the bronchodilatory action [49-51]. The adverse effects are generally dose-related. Increase in the dose of short-acting inhaled β2-agonist and anticholinergic, especially when given nebulized, may relieve subjective dyspnoea in acute setting during an exacerbation of COPD but may not help as a long-term therapy [52,53]. Bronchodilators can be divided into short-acting (duration of bronchodilatory effect generally 3-6 hr) and long-acting (duration of bronchodilatory effect generally 12-24 hr). There are two different classes of bronchodilators that have basically similar bronchodilatory action in the treatment of COPD but different mechanism of action. These pharmacological classes are β2-agonists and muscarinic receptor (M1, M2 and M3) antagonists (termed anticholinergics) [54,55]. Both of thesepharmacological classes contain short-acting and long-acting preparations. Bronchodilators are usually administered either on as-needed basis (usually short-acting preparations) or regularly (usually long-acting preparations) to treat or prevent the occurrence of symptoms.A short-acting bronchodilator to be used on as-needed basis is considered beneficial for most patients even though they were treated with long-acting bronchodilators or combination therapy including long-acting bronchodilators. Instead, the use of regular, high-dose (nebulized etc.) short-acting bronchodilator or their combination in patients treated with long-acting bronchodilators is not evidence-based [3] and should only be reserved to treatment of the most difficult cases. In such a situation, the need for long-acting bronchodilators should be carefully evaluated as well as the ability of the patient to properly inhale them.Short- and long-acting β2-agonists (SABA, LABA)The main beneficial effect of β2-agonists is the reduction of bronchial smooth muscle contraction that leads to relief of bronchial obstruction. The duration of the effect of short-acting β2-agonists is usually 3-6 hr. Short-acting β2-agonist used either as needed or regularly reduce symptoms of COPD and improve lung function measured e.g. by FEV1 or FVC [56]. The effect of long-acting β2-agonists lasts 12 hr (formoterol or salmeterol) or 24 hr (indacaterol, olodaterol or vilanterol). The bronchodilatory action of formoterol/indacaterol/olodaterol/vilanterol starts sooner (within 5 min.) than that of salmeterol (within 20-30 min.). Indacaterol improves lung function (e.g. FEV1), reduces dyspnoea during exercise and improves the quality of life, but the evidence on the reduction of COPD exacerbations is still preliminary [57-60]. The efficacy of indacaterol, olodaterol or vilanterol, when measured by using FEV1 or quality of life, is at least as good as that of formoterol or salmeterol [58,61-63] or the long-acting anticholinergic tiotropium [58,61,64].Generally, β2-agonists are well tolerated. Typical adverse effects include tremor, tachycardia and palpitations that have been reported in <1% of the exposed persons. Headache, muscular crampsand an increase in the blood glucose and a decrease in potassium levels are possible, even though these events occur almost as often in patients treated with placebo [65]. It has been suggested that activation of heart β2-receptors by β2-agonists might induce ischaemia, cardiac insufficiency, arrhythmias or increase the risk of sudden death. However, in controlled clinical studies recruiting patients with COPD, there is no indication for the increase of arrhythmias or cardiac deaths [65] or over-all mortality [66] by β2-agonists. Based on a case-control study [67], an increase in the risk of severe arrhythmias is possible. Thus, the benefits of using long-acting β2-agonist in patients with severe cardiac disease should be carefully considered.The use of long-acting β2-agonists in the treatment of asthma in the absence of simultaneous inhaled glucocorticoids is prohibited [7] because there is evidence that treatment of asthma with long-acting β2-agonists in the absence of inhaled glucocorticoids increases mortality due to asthma [68]. In contrast, in the treatment of COPD, a long-acting β2-agonist can be used as the sole therapy as it does not increase mortality in COPD according to the studies published [65,66 ]. According to some cohort studies, use of long-acting β2-agonist may even reduce the mortality of patients with COPD [69,70].Short- and long-acting anticholinergics (SAMA, LAMA)Anticholinergic compounds block muscarinic receptors (M1, M2 and M3) thus antagonizing acetylcholine-induced bronchial smooth muscle contraction. The duration of the effect of short-acting anticholinergic (ipratropium) is usually somewhat longer (even up to 8 hr) than that of the short-acting β2-agonists (3-6 hr), but starts more slowly [54,55]. The effect of long-acting anticholinergics lasts either 12 hr (aclidinium) or approximately 24 hr (glycopyrronium, tiotropium or umeclidinium). Of these, tiotropium has been most extensively studied and used. The bronchodilatory action of aclidinium and glycopyrronium starts sooner than that of tiotropium.Tiotropium improves lung function and quality of life and reduces symptoms and exacerbations of COPD (A) [71]. In contrast, tiotropium does not affect the progression of the disease as judged by the annual decline in FEV1 [72]. Tiotropium may be more effective than salmeterol in reducing exacerbations of COPD [73]. Both aclidinium and glycopyrronium have been shown to induce bronchodilation, improve lung function and quality of life and reducing the need for rescue medication [74,75] and their efficacy roughly equals to that of tiotropium. Aclidinium, glycopyrronium and umeclidinium have been shown to reduce COPD exacerbations in studies lasting up to one year [76,77, 78], but long-term studies lasting more than one year, similar to those made with tiotropium [72,73], are still lacking.Inhaled anticholinergics are generally well tolerated and adverse effects occur relatively seldom. Typical adverse effects, such as dry mouth, blurred vision, throat irritation, rhinitis, constipation and nausea, are due to blocking of muscarinic receptors. Other possible adverse effects include also arrhythmias, urinary retention/obstruction, elevated intraocular pressure and acute or worsening of narrow-angle glaucoma [79].The short-acting anticholinergic ipratropium has been suspected to induce cardiac adverse effects [79]. With the long-acting anticholinergics, no similar increase in cardiac adverse effects has been reported with certainty [79]. The four-year long UPLIFT trial reported that there were statistically significantly less cardiac adverse effects and the total mortality was numerically, although not statistically, lower in patients treated with tiotropium [72].Recently, it has been proposed that dosing of tiotropium with Respimat® device would cause more deaths than its dosing with Handihaler® device [79]. However, a direct comparison of the two devices for a mean 2.3 years indicated that there were no differences in mortality, serious cardiac adverse effects or exacerbations of COPD [80].。