The Equivalence of Price and Quantity Competition with Incentive Scheme Commitment

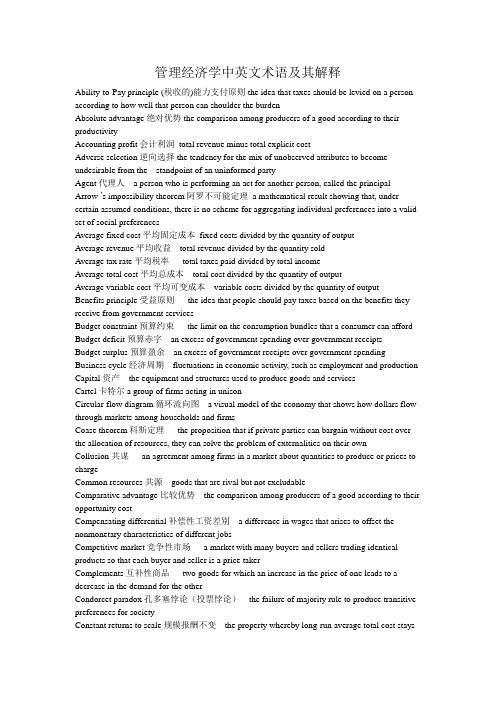

管理经济学中英文术语及其解释

管理经济学中英文术语及其解释Ability-to-Pay principle (税收的)能力支付原则the idea that taxes should be levied on a person according to how well that person can shoulder the burdenAbsolute advantage绝对优势the comparison among producers of a good according to their productivityAccounting profit会计利润total revenue minus total explicit costAdverse selection逆向选择the tendency for the mix of unobserved attributes to become undesirable from the standpoint of an uninformed partyAgent代理人 a person who is performing an act for another person, called the principalArrow ‟s impossibility theorem阿罗不可能定理a mathematical result showing that, under certain assumed conditions, there is no scheme for aggregating individual preferences into a valid set of social preferencesAverage fixed cost平均固定成本fixed costs divided by the quantity of outputAverage revenue平均收益total revenue divided by the quantity soldAverage tax rate平均税率total taxes paid divided by total incomeAverage total cost平均总成本total cost divided by the quantity of outputAverage variable cost平均可变成本variable costs divided by the quantity of outputBenefits principle受益原则the idea that people should pay taxes based on the benefits they receive from government servicesBudget constraint预算约束the limit on the consumption bundles that a consumer can afford Budget deficit预算赤字an excess of government spending over government receiptsBudget surplus预算盈余an excess of government receipts over government spending Business cycle经济周期fluctuations in economic activity, such as employment and production Capital资产the equipment and structures used to produce goods and servicesCartel卡特尔a group of firms acting in unisonCircular-flow diagram循环流向图 a visual model of the economy that shows how dollars flow through markets among households and firmsCoase theorem科斯定理the proposition that if private parties can bargain without cost over the allocation of resources, they can solve the problem of externalities on their ownCollusion共谋an agreement among firms in a market about quantities to produce or prices to chargeCommon resources共源goods that are rival but not excludableComparative advantage比较优势the comparison among producers of a good according to their opportunity costCompensating differential补偿性工资差别 a difference in wages that arises to offset the nonmonetary characteristics of different jobsCompetitive market竞争性市场 a market with many buyers and sellers trading identical products so that each buyer and seller is a price takerComplements互补性商品two goods for which an increase in the price of one leads to a decrease in the demand for the otherCondorcet paradox孔多塞悖论(投票悖论)the failure of majority rule to produce transitive preferences for societyConstant returns to scale规模报酬不变the property whereby long-run average total cost staysthe same as the quantity of output changesConsumer surplus消费者剩余 a buyer‟s willingness to pay minus the amount the buyer actually paysCost成本the value of everything a seller must give up to produce a goodCost-benefit analysis成本收益分析 a study that compares the costs and benefits to society of providing a public goodCross-price elasticity of demand需求的交叉价格弹性 a measure of how much the quantity demanded of one good responds to a change in the price of another good, computed as the percentage change in quantity demanded of the first good divided by the percentage change in the price of the second goodDeadweight loss无谓损失the fall in total surplus that results from a market distortion, such as a taxDemand curve需求曲线 a graph of the relationship between the price of a good and the quantity demandedDemand schedule需求表 a table that shows the relationship between the price of a good and the quantity demandedDiminishing marginal product边际产品递减the property whereby the marginal product of an input declines.As the quantity of the input increasesDiscrimination歧视the offering of different opportunities to similar individuals who differ only by race, ethnic group, sex, age, or other personal characteristicsDiseconomies of scale规模不经济the property whereby long-run average total cost rises as the quantity of output increasesDominant strategy占优策略 a strategy that is best for a player in a game regardless of the strategies chosen by the other playersEconomic profit经济利润total revenue minus total cost, including both explicit and implicit costsEconomics经济学the study of how society manages its scarce resourcesEconomies of scale规模经济the property whereby long-run average total cost falls as the quantity of output increasesEfficiency效率the property of society getting the most it can from its scarce resources Efficiency wages效率工资above-equilibrium wages paid by firms in order to increase worker productivityEfficient scale有效规模the quantity of output that minimizes average total costElasticity弹性 a measure of the responsiveness of quantity demanded or quantity supplied to one of its determinantsEquilibrium均衡 a situation in which the price has reached the level where quantity supplied equals quantity demandedEquilibrium price均衡价格the price that balances quantity supplied and quantity demanded Equilibrium quantity均衡数量the quantity supplied and the quantity demanded at the equilibrium priceEquity平等the property of distributing economic prosperity fairly among the members of societyExcludability排他性the property of a good whereby a person can be prevented from using it Explicit costs显性成本input costs that require an outlay of money by the firmExports出口goods produced domestically and sold abroadExternality外部性the uncompensated impact of one person‟s actions on the wellbeing of a bystanderFactors of production生产要素the inputs used to produce goods and servicesFixed casts固定成本costs that do not vary with the quantity of output producedFree rider免费搭车者 a person who receives the benefit of a good but avoids paying for it Game theory博弈论the study of how people behave in strategic situationsGiffen good吉芬商品 a good for which an increase in the price raises the quantity demanded Horizontal equity横向公平the idea that taxpayers with similar abilities to pay taxes should pay the same amountHuman capital人力资本the accumulation of investments in people, such as education andon-the-job trainingImplicit costs隐性成本input costs that do not require an outlay of money by the firmImport quota进口配额 a limit on the quantity of a good that can be produced abroad and sold domesticallyImports进口goods produced abroad and sold domesticallyIncome effect收入效应the change in consumption that results when a price change moves the consumer to a higher or lower indifference curveIncome elasticity of demand需求的收入弹性 a measure of how much the quantity demanded of a good responds to a change in consumers‟ income, computed as the percentage change in quantity demanded divided by the percentage change in incomeIndifference curve无差异曲线 a curve that shows consumption bundles that give the consumer the same level of satisfactionInferior good低档物品 a good for which, other things equal, an increase in income leads to a decrease in demandInflation通货膨胀an increase in the overall level of prices in the economyIn-kind transfers实物转移支付transfers to the poor given in the form of goods and services rather than cashInternalizing an externality外部性的内在化altering incentives so that people take account of the external effects of their actionsLaw of demand需求定理the claim that, other things equal, the quantity demanded of a good falls when the price of the good risesLaw of supply and demand需求与供给定理the claim that the price of any good adjusts to bring the quantity supplied and the quantity demanded for that good into balanceLiberalism自由主义the political philosophy according to which the government should choose policies deemed to be just, as evaluated by an impartial observer behind a “veil of ignorance”Libertarianism自由至上主义the political philosophy according to which the government should punish crimes and enforce voluntary agreements but not redistribute incomeLife cycle生命周期the regular pattern of income variation over a person‟s lifeLump-sum tax定额税 a tax that is the same amount for every personMacroeconomics宏观经济学the study of economy-wide phenomena, including inflation, unemployment, and economic growthMarginal changes边际变动small incremental adjustments to a plan of actionMarginal cost边际成本the increase in total cost that arises from an extra unit of production Marginal product边际产品the increase in output that arises from an additional unit of input Marginal product of labor劳动的边际产品the increase in the amount of output from an additional unit of laborMarginal rate of substitution边际替代率the rate at which a consumer is willing to trade one good for anotherMarginal revenue边际收益the change in total revenue from an additional unit soldMarginal tax rate边际税率the extra taxes paid on an additional dollar of incomeMarket市场 a group of buyers and sellers of a particular good or serviceMarket economy市场经济an economy that allocates resources through the decentralized decisions of many firms and households as they interact in markets for goods and services Market failure市场失灵 a situation in which a market left on its own fails to allocate resources efficientlyMarket power市场势力the ability of a single economic actor (or small group of actors) to have a substantial influence on market pricesMaximin criterion极大极小准则the claim that the government should aim to maximize the well-being of the worst-off person in societyMedian voter theorem中位选举人定理 a mathematical result showing that if voters are choosing a point along a line and each voter wants the point closest to his most preferred point, then majority rule will pick the most preferred point of the median voterMicroeconomics微观经济学the study of how households and firms make decisions and how they interact in marketsMonopolistic competition垄断竞争 a market structure in which many firms sell products that are similar but not identicalMonopoly垄断 a firm that is the sole seller of a product without close substitutesMoral hazard道德风险the tendency of a person who is imperfectly monitored to engage in dishonest or otherwise undesirable behaviorNash equilibrium纳什均衡 a situation in which economic actors interacting with one another each choose their best strategy given the strategies that all the other actors have chosenNatural monopoly自然垄断 a monopoly that arises because a single firm can supply a good or service to an entire market at a smaller cost than could two or more firmsNegative income tax负所得税 a tax system that collects revenue from high-income households and gives transfers to low-income householdsNormal good正常商品 a good for which, other things equal, an increase in income leads to an increase in demandNormative statements规范性表述claims that attempt to prescribe how the world should be Oligopoly寡头 a market structure in which only a few sellers offer similar or identical productsOpportunity cost机会成本whatever must be given up to obtain some itemPerfect complements完全互补品two goods with right-angle indifference curvesPerfect substitutes完全替代品two goods with straight-line indifference curvesPermanent income持久性收入 a person‟s normal incomePhillips curve菲利普斯曲线 a curve that shows the short-run tradeoff between inflation and unemploymentPigovian tax庇古税 a tax enacted to correct the effects of a negative externalityPositive statements实证表述claims that attempt to describe the world as it isPoverty line贫困线an absolute level of income set by the federal government for each family size below which a family is deemed to be in povertyPoverty rate贫困率the percentage of the population whose family income falls below an absolute level called the …poverty linePrice ceiling价格天花板(上限) a legal maximum on the price at which a good can be sold Price discrimination价格歧视the business practice of selling the same good at different prices to different customersPrice elasticity of demand需求的价格弹性 a measure of how much the quantity demanded of a good responds to a change in the price of that good, computed as the percentage change in quantity demanded divided by the percentage change in pricePrice elasticity supply供给的价格弹性 a measure of how much the quantity supplied of a good responds to a change in the price of that good, computed as the percentage change in quantity supplied divided by the percentage change in pricePrice floor价格地板I下限) a legal minimum on the price at which a good can be sold Principal委托人 a person for whom another person, called the agent, is performing some act Prisoners‟ dilemma囚徒困境 a particular “game” between two captured prisoners that illustrates why cooperation is difficult to maintain even when it is mutually beneficialPrivate goods私人物品goods that are both excludable and rivalProducer surplus生产者剩余the amount a seller is paid for a good minus the seller‟s cost Production function生产函数the relationship between quantity of inputs used to make a good and the quantity of output of that goodProduction possibilities frontier生产可能性曲线 a graph that shows the combinations of output that the economy can possibly produce given the available factors of production and the available production technologyProductivity生产率the quantity of goods and services produced from each hour of a worker‟s timeProfit利润total revenue minus total costProgressive tax累进税 a tax for which high-income taxpayers pay a larger fraction of their income than do low-income taxpayersProportional tax比例税 a tax for which high-income and low-income taxpayers pay the same fraction of incomePublic goods公共产品goods that are neither excludable nor rivalQuantity demanded需求数量the amount of a good that buyers are willing and able to purchase Quantity supplied供给数量the amount of a good that sellers are willing and able to sell Regressive tax累退税 a tax for which high-income taxpayers pay a smaller fraction of their income than do low-income taxpayersRivalry竞争the property of a good whereby one person‟s use diminishes other people‟s use Scarcity稀缺性the limited nature of society‟s resourcesScreening筛选an action taken by an uninformed party to induce an informed party to reveal informationShortage短缺 a situation in which quantity demanded is greater than quantity supplied Signaling信号显示an action taken by an informed party to reveal private information to anuninformed partyStrike罢工the organized withdrawal of labor from a firm by a unionSubstitutes替代品two goods for which an increase in the price of one leads to an increase in the demand for the otherSubstitution effect替代效应the change in consumption that results when a price change moves the consumer along a given indifference curve to a point with a new marginal rate of substitution Sunk cost沉淀成本 a cost that has already been committed and cannot be recoveredSupply curve供给曲线 a graph of the relationship between the price of a good and the quantity suppliedSupply schedule供给表 a table that shows the relationship between the price of a good and the quantity suppliedSurplus过剩 a situation in which quantity supplied is greater than quantity demandedTariff关税 a tax on goods produced abroad and sold domesticallyTax incidence税收归宿the manner in which the burden of a tax is shared among participants in a marketTotal cost总成本the market value of the inputs a firm uses in productionTotal revenue (for a firm)总收益the amount a firm receives for the sale of its outputTotal revenue (in a market)总收益the amount paid by buyers and received by sellers of a good, computed as the price of the good times the quantity soldTragedy of the Commons公共地的悲剧a parable that illustrates why common resources get used more than is desirable from the standpoint of society as a wholeTransaction costs交易成本the costs that parties incur in the process of agreeing and following through on a bargainUnion工会 a worker association that bargains with employers over wages and working conditionsUtilitarianism功利主义the political philosophy according to which the government should choose policies to maximize the total utility of everyone in societyUtility效用 a measure of happiness or satisfactionValue of the marginal product边际产品价值the marginal product of an input times the price of the outputVariable costs可变成本costs that vary with the quantity of output producedVertical equity纵向公平the idea that taxpayers with a greater ability to pay taxes should pay larger amountsWelfare福利government programs that supplement the incomes of the needyWelfare economics福利经济学the study of how the allocation of resources affects economic well-beingWillingness to pay支付意愿the maximum amount that a buyer will pay for a goodWorld price世界价格the price of a good that prevails in the world market for that good。

经济学常用英语词汇英汉对照

经济学常用英语词汇英汉对照accounting cost 会计成本accounting profit 会计利润adverse selection 逆向选择allocation 配置allocation of resources 资源配置allocative efficiency 配置效率antitrust legislation 反托拉斯法arc elasticity 弧弹性Arrow's impossibility theorem 阿罗不可能定理Assumption 假设asymetric information 非对称性信息average 平均average cost 平均成本average cost pricing 平均成本定价法average fixed cost 平均固定成本average product of capital 资本平均产量average product of labour 劳动平均产量average revenue 平均收益average total cost 平均总成本average variable cost 平均可变成本barriers to entry 进入壁垒base year 基年bilateral monopoly 双边垄断benefit 收益black market 黑市bliss point 极乐点boundary point 边界点break even point 收支相抵点budget 预算budget constraint 预算约束budget line 预算线budget set 预算集capital 资本capital stock 资本存量capital output ratio 资本产出比率capitalism 资本主义cardinal utility theory 基数效用论cartel 卡特尔ceteris puribus assumption “其他条件不变”的假设ceteris puribus demand curve 其他因素不变的需求曲线Chamberlin model 张伯伦模型change in demand 需求变化change in quantity demanded 需求量变化change in quantity supplied 供给量变化change in supply 供给变化choice 选择closed set 闭集Coase theorem 科斯定理Cobb—Douglas production function 柯布--道格拉斯生产函数cobweb model 蛛网模型collective bargaining 集体协议工资collusion 合谋command economy 指令经济commodity 商品commodity combination 商品组合commodity market 商品市场commodity space 商品空间common property 公用财产comparative static analysis 比较静态分析compensated budget line 补偿预算线compensated demand function 补偿需求函数compensation principles 补偿原则compensating variation in income 收入补偿变量competition 竞争competitive market 竞争性市场complement goods 互补品complete information 完全信息completeness 完备性condition for efficiency in exchange 交换的最优条件condition for efficiency in production 生产的最优条件concave 凹concave function 凹函数concave preference 凹偏好consistence 一致性constant cost industry 成本不变产业constant returns to scale 规模报酬不变constraints 约束consumer 消费者consumer behavior 消费者行为consumer choice 消费者选择consumer equilibrium 消费者均衡consumer optimization 消费者优化consumer preference 消费者偏好consumer surplus 消费者剩余consumer theory 消费者理论consumption 消费consumption bundle 消费束consumption combination 消费组合consumption possibility curve 消费可能曲线consumption possibility frontier 消费可能性前沿consumption set 消费集consumption space 消费空间continuity 连续性continuous function 连续函数contract curve 契约曲线convex 凸convex function 凸函数convex preference 凸偏好convex set 凸集corporatlon 公司cost 成本cost benefit analysis 成本收益分cost function 成本函数cost minimization 成本极小化Cournot equilihrium 古诺均衡Cournot model 古诺模型Cross—price elasticity 交叉价格弹性dead—weights loss 重负损失decreasing cost industry 成本递减产业decreasing returns to scale 规模报酬递减deduction 演绎法demand 需求demand curve 需求曲线demand elasticity 需求弹性demand function 需求函数demand price 需求价格demand schedule 需求表depreciation 折旧derivative 导数derive demand 派生需求difference equation 差分方程differential equation 微分方程differentiated good 差异商品differentiated oligoply 差异寡头diminishing marginal substitution 边际替代率递减diminishing marginal return 收益递减diminishing marginal utility 边际效用递减direct approach 直接法direct taxes 直接税discounting 贴税、折扣diseconomies of scale 规模不经济disequilibrium 非均衡distribution 分配division of labour 劳动分工distribution theory of marginal productivity 边际生产率分配论duoupoly 双头垄断、双寡duality 对偶durable goods 耐用品dynamic analysis 动态分析dynamic models 动态模型Economic agents 经济行为者economic cost 经济成本economic efficiency 经济效率economic goods 经济物品economic man 经济人economic mode 经济模型economic profit 经济利润economic region of production 生产的经济区域economic regulation 经济调节economic rent 经济租金exchange 交换economics 经济学exchange efficiency 交换效率economy 经济exchange contract curve 交换契约曲线economy of scale 规模经济Edgeworth box diagram 埃奇沃思图exclusion 排斥性、排他性Edgeworth contract curve 埃奇沃思契约线Edgeworth model 埃奇沃思模型efficiency 效率,效益efficiency parameter 效率参数elasticity 弹性elasticity of substitution 替代弹性endogenous variable 内生变量endowment 禀赋endowment of resources 资源禀赋Engel curve 恩格尔曲线entrepreneur 企业家entrepreneurship 企业家才能entry barriers 进入壁垒entry/exit decision 进出决策envolope curve 包络线equilibrium 均衡equilibrium condition 均衡条件equilibrium price 均衡价格equilibrium quantity 均衡产量eqity 公平equivalent variation in income 收入等价变量excess—capacity theorem 过度生产能力定理excess supply 过度供给exchange 交换exchange contract curve 交换契约曲线exclusion 排斥性、排他性exclusion principle 排他性原则existence 存在性existence of general equilibrium 总体均衡的存在性exogenous variables 外生变量expansion paths 扩展径expectation 期望expected utility 期望效用expected value 期望值expenditure 支出explicit cost 显性成本external benefit 外部收益external cost 外部成本external economy 外部经济external diseconomy 外部不经济externalities 外部性Factor 要素factor demand 要素需求factor market 要素市场factors of production 生产要素factor substitution 要素替代factor supply 要素供给fallacy of composition 合成谬误final goods 最终产品firm 企业firms’demand curve for labor 企业劳动需求曲线firm supply curve 企业供给曲线first-degree price discrimination 第一级价格歧视first—order condition 一阶条件fixed costs 固定成本fixed input 固定投入fixed proportions production function 固定比例的生产函数flow 流量fluctuation 波动for whom to produce 为谁生产free entry 自由进入free goods 自由品,免费品free mobility of resources 资源自由流动free rider 搭便车,免费搭车function 函数future value 未来值game theory 对策论、博弈论general equilibrium 总体均衡general goods 一般商品Giffen goods 吉芬晶收入补偿需求曲线Giffen's Paradox 吉芬之谜Gini coefficient 吉尼系数goldenrule 黄金规则goods 货物government failure 政府失败government regulation 政府调控grand utility possibility curve 总效用可能曲线grand utility possibility frontier 总效用可能前沿heterogeneous product 异质产品Hicks—kaldor welfare criterion 希克斯一卡尔多福利标准homogeneity 齐次性homogeneous demand function 齐次需求函数homogeneous product 同质产品homogeneous production function 齐次生产函数horizontal summation 水平和household 家庭how to produce 如何生产human capital 人力资本hypothesis 假说identity 恒等式imperfect competion 不完全竞争implicitcost 隐性成本income 收入income compensated demand curveincome constraint 收入约束income consumption curve 收入消费曲线income distribution 收入分配income effect 收入效应income elasticity of demand 需求收入弹性increasing cost industry 成本递增产业increasing returns to scale 规模报酬递增inefficiency 缺乏效率index number 指数indifference 无差异indifference curve 无差异曲线indifference map 无差异族indifference relation 无差异关系indifference set 无差异集indirect approach 间接法individual analysis 个量分析individual demand curve 个人需求曲线individual demand function 个人需求函数induced variable 引致变量induction 归纳法industry 产业industry equilibrium 产业均衡industry supply curve 产业供给曲线inelastic 缺乏弹性的inferior goods 劣品inflection point 拐点information 信息information cost 信息成本initial condition 初始条件initial endowment 初始禀赋innovation 创新input 投入input—output 投入—产出institution 制度institutional economics 制度经济学insurance 保险intercept 截距interest 利息interest rate 利息率intermediate goods 中间产品internatization of externalities 外部性内部化invention 发明inverse demand function 逆需求函数investment 投资invisible hand 看不见的手isocost line 等成本线,isoprofit curve 等利润曲线isoquant curve 等产量曲线isoquant map 等产量族kinded—demand curve 弯折的需求曲线labour 劳动labour demand 劳动需求labour supply 劳动供给labour theory of value 劳动价值论labour unions 工会laissez faire 自由放任Lagrangian function 拉格朗日函数Lagrangian multiplier 拉格朗乘数,land 土地law 法则law of demand and supply 供需法law of diminishing marginal utility 边际效用递减法则law of diminishing marginal rate of substitution 边际替代率递减法则law of diminishing marginal rate of technical substitution 边际技术替代率law of increasing cost 成本递增法则law of one price 单一价格法则leader—follower model 领导者--跟随者模型least—cost combination of inputs 最低成本的投入组合leisure 闲暇Leontief production function 列昂节夫生产函数licenses 许可证linear demand function 线性需求函数linear homogeneity 线性齐次性linear homogeneous production function 线性齐次生产函数long run长期long run average cost 长期平均成本long run equilibrium 长期均衡long run industry supply curve 长期产业供给曲线long run marginal cost 长期边际成本long run total cost 长期总成本Lorenz curve 洛伦兹曲线loss minimization 损失极小化1ump sum tax 一次性征税luxury 奢侈品macroeconomics 宏观经济学marginal 边际的marginal benefit 边际收益marginal cost 边际成本marginal cost pricing 边际成本定价marginal cost of factor 边际要素成本marginal period 市场期marginal physical productivity 实际实物生产率marginal product 边际产量marginal product of capital 资本的边际产量marginal product of 1abour 劳动的边际产量marginal productivity 边际生产率marginal rate of substitution 边替代率marginal rate of transformation 边际转换率marginal returns 边际回报marginal revenue 边际收益marginal revenue product 边际收益产品marginal revolution 边际革命marginal social benefit 社会边际收益marginal social cost 社会边际成本marginal utility 边际效用marginal value products 边际价值产品market 市场market clearance 市场结清,市场洗清market demand 市场需求market economy 市场经济market equilibrium 市场均衡market failure 市场失败market mechanism 市场机制market structure 市场结构market separation 市场分割market regulation 市场调节market share 市场份额markup pricing 加减定价法Marshallian demand function 马歇尔需求函数maximization 极大化microeconomics 微观经济学minimum wage 最低工资misallocation of resources 资源误置mixed economy 混合经济model 模型money 货币monopolistic competition 垄断竞争monopolistic exploitation 垄断剥削monopoly 垄断,卖方垄断monopoly equilibrium 垄断均衡monopoly pricing 垄断定价monopoly regulation 垄断调控monopoly rents 垄断租金monopsony 买方垄断Nash equilibrium 纳什均衡Natural monopoly 自然垄断Natural resources 自然资源Necessary condition 必要条件necessities 必需品net demand 净需求nonconvex preference 非凸性偏好nonconvexity 非凸性nonexclusion 非排斥性nonlinear pricing 非线性定价nonrivalry 非对抗性nonprice competition 非价格竞争nonsatiation 非饱和性non--zero—sum game 非零和对策normal goods 正常品normal profit 正常利润normative economics 规范经济学objective function 目标函数oligopoly 寡头垄断oligopoly market 寡头市场oligopoly model 寡头模型opportunity cost 机会成本optimal choice 最佳选择optimal consumption bundle 消费束perfect elasticity 完全有弹性optimal resource allocation 最佳资源配置optimal scale 最佳规模optimal solution 最优解optimization 优化ordering of optimization(social) preference (社会)偏好排序ordinal utility 序数效用ordinary goods 一般品output 产量、产出output elasticity 产出弹性output maximization 产出极大化parameter 参数Pareto criterion 帕累托标准Pareto efficiency 帕累托效率Pareto improvement 帕累托改进Pareto optimality 帕累托优化Pareto set 帕累托集partial derivative 偏导数partial equilibrium 局部均衡patent 专利pay off matrix 收益矩阵、支付矩阵perceived demand curve 感觉到的需求曲线perfect competition 完全竞争perfect complement 完全互补品perfect monopoly 完全垄断perfect price discrimination 完全价格歧视perfect substitution 完全替代品perfect inelasticity 完全无弹性perfectly elastic 完全有弹性perfectly inelastic 完全无弹性plant size 工厂规模point elasticity 点弹性positive economics 实证经济学post Hoc Fallacy 后此谬误prediction 猜测preference 偏好preference relation 偏好关系present value 现值price 价格price adjustment model 价格调整模型price ceiling 最高限价price consumption curve 价格费曲线price control 价格管制price difference 价格差别price discrimination 价格歧视price elasticity of demand 需求价格弹性price elasticity of supply 供给价格弹性price floor 最低限价price maker 价格制定者price rigidity 价格刚性price seeker 价格搜求者price taker 价格接受者price tax 从价税private benefit 私人收益principal—agent issues 委托--代理问题private cost 私人成本private goods 私人用品private property 私人财产producer equilibrium 生产者均衡producer theory 生产者理论product 产品product transformation curve 产品转换曲线product differentiation 产品差异product group 产品集团production 生产production contract curve 生产契约曲线production efficiency 生产效率production function 生产函数production possibility curve 生产可能性曲线productivity 生产率productivity of capital 资本生产率productivity of labor 劳动生产率profit 利润profit function 利润函数profit maximization 利润极大化property rights 产权property rights economics 产权经济学proposition 定理proportional demand curve 成比例的需求曲线public benefits 公共收益public choice 公共选择public goods 公共商品pure competition 纯粹竞争rivalry 对抗性、竞争pure exchange 纯交换pure monopoly 纯粹垄断quantity—adjustment model 数量调整模型quantity tax 从量税quasi—rent 准租金rate of product transformation 产品转换率rationality 理性reaction function 反应函数regulation 调节,调控relative price 相对价格rent 租金rent control 规模报酬rent seeking 寻租rent seeking economics 寻租经济学resource 资源resource allocation 资源配置returns 报酬、回报returns to scale 规模报酬revealed preference 显示性偏好revenue 收益revenue curve 收益曲线revenue function 收益函数revenue maximization 收益极大化ridge line 脊线risk 风险satiation 饱和,满足saving 储蓄scarcity 稀缺性law of scarcity 稀缺法则second—degree price discrimination 二级价格歧视second derivative --阶导数second—order condition 二阶条件service 劳务set 集shadow prices 影子价格short—run 短期short—run cost curve 短期成本曲线short—run equilibrium 短期均衡short—run supply curve 短期供给曲线shut down decision 关闭决策shortage 短缺shut down point 关闭点single price monopoly 单一定价垄断slope 斜率social benefit 社会收益social cost 社会成本social indifference curve 社会无差异曲线social preference 社会偏好social security 社会保障social welfare function 社会福利函数socialism 社会主义solution 解space 空间stability 稳定性stable equilibrium 稳定的均衡Stackelberg model 斯塔克尔贝格模型static analysis 静态分析stock 存量stock market 股票市场strategy 策略subsidy 津贴substitutes 替代品substitution effect 替代效应substitution parameter 替代参数sufficient condition 充分条件supply 供给supply curve 供给曲线supply function 供给函数supply schedule 供给表Sweezy model 斯威齐模型symmetry 对称性symmetry of information 信息对称tangency 相切taste 兴致technical efficiency 技术效率technological constraints 技术约束technological progress 技术进步technology 技术third—degree price discrimination 第三级价格歧视total cost 总成本total effect 总效应total expenditure 总支出total fixed cost 总固定成本total product 总产量total revenue 总收益total utility 总效用total variable cost 总可变成本traditional economy 传统经济transitivity 传递性transaction cost 交易费用uncertainty 不确定性uniqueness 唯一性unit elasticity 单位弹性unstable equilibrium 不稳定均衡utility 效用utility function 效用函数utility index 效用指数utility maximization 效用极大化utility possibility curve 效用可能性曲线utility possibility frontier 效用可能性前沿Value 价值value judge 价值判定value of marginal product 边际产量价值variable cost 可变成本variable input 可变投入variables 变量vector 向量visible hand 看得见的手vulgur economics 庸俗经济学wage 工资wage rate 工资率Walras general equilibrium 瓦尔拉斯总体均衡Walras's law 瓦尔拉斯法则Wants 需要Welfare criterion 福利标准Welfare economics 福利经学Welfare loss triangle 福利损失三角形welfare maximization 福利极大化zero cost 零成本zero elasticity 零弹性zero homogeneity 零阶齐次性zero economic profit 零利润。

政治经济学英文名词解释

政治经济学名词英文解释导论:1.Production of Material Goods:The production of material goods is the basis of the existence and development of human society.2.Productive Forces and Productive Relations:Productive relations are determined by productive forces. The development of productive relations is determined by the development of productive forces.第二章商品与货币modities:商品The products of labor used for exchanging.商品是用来交换的劳动产品。

e-Value: 使用价值A commodity is a thing that by its properties satisfies human wants of some sort or another.物品的这种能够满足人们某种需要的属性,(即物的有用性,就是物品的使用价值。

)The natural property of commodities.使用价值是商品的自然属性。

3.Exchange Value:交换价值Presents itself as a quantitative relation, as the proportion inwhich values in use(use-value)of one sort are exchanged for those of another sort.(交换价值首先)表现为一种量的关系,也表现为使用价值同另一种使用价值相交换的量的比例。

Hummels&Klenow

The Variety and Quality of a Nation’s ExportsBy D AVID H UMMELS AND P ETER J.K LENOW*Large economies export more in absolute terms than do small economies.We use data on shipments by126exporting countries to59importing countries in5,000 product categories to answer the question:How?Do big economies export larger quantities of each good(the intensive margin),a wider set of goods(the extensive margin),or higher-quality goods?Wefind that the extensive margin accounts for around60percent of the greater exports of larger economies.Within categories, richer countries export higher quantities at modestly higher prices.We compare thesefindings to some workhorse trade models.Models with Armington national product differentiation have no extensive margin,and incorrectly predict lower prices for the exports of larger economies.Models with Krugmanfirm-level product differentiation do feature a prominent extensive margin,but overpredict the rate at which variety responds to exporter size.Models with quality differentiation,mean-while,can match the price facts.Finally,models withfixed costs of exporting to a given market might explain the tendency of larger economies to export a given product to more countries.(JEL F12,F43)Virtually every theory of international trade predicts that a larger economy will export more in absolute terms than a smaller economy. Trade theories differ,however,in their predic-tions about how larger economies export more. Models that assume Paul S.Armington’s(1969) national differentiation emphasize the intensive margin:an economy twice the size of another will export twice as much but will not export a wider variety of goods.Monopolistic competi-tion models in the vein of Paul R.Krugman (1981)stress the extensive margin:economies twice the size will produce and export twice the range of goods.Vertical differentiation models, such as Harry Flam and Elhanan Helpman (1987)and Gene M.Grossman and Helpman (1991),feature a quality margin,namely richer countries produce and export higher-quality goods.These divergent predictions imply very dif-ferent consequences for welfare.If larger econ-omies intensively export more of each variety, the prices of their national varieties should be lower on the world market.In large-scale Com-putable General Equilibrium(CGE)models with distinct national varieties,the simulated welfare changes associated with trade liberal-ization are dominated by such terms-of-trade effects(see Drusilla K.Brown,1987).In Daron Acemoglu and Jaume Ventura(2002),these effects prevent real per capita incomes from diverging across countries with differing invest-ment rates.These authors argue that richer countries face lower export prices,and that this is the critical force maintaining a stationary world income distribution.1To the extent larger economies export a wider array of goods or export higher-quality goods, lower export prices are no longer a necessary*Hummels:Krannert School of Management,Purdue University,403West State Street,West Lafayette,IN47907 and National Bureau of Economic Research(e-mail: hummels@);Klenow:Department of Economics,Stanford University,579Serra Mall,Stanford, CA94305and National Bureau of Economic Research (e-mail:klenow@).We are grateful to Oleksiy Kryvtsov and Volodymyr Lugovskyy for excellent research assistance,and to the Purdue University Center for Interna-tional Business and Research for funding data purchases.Hummels acknowledges the assistance of the National Sci-ence Foundation(Grant0318242).We thank Mark Bils, Russell Cooper,Eduardo Engel,Thomas Hertel,Russell Hillberry,Tom Holmes,Valerie Ramey,Richard Rogerson, and three anonymous referees for helpful comments.1Donald R.Davis and David E.Weinstein(2002)build on the Acemoglu and Ventura model in estimating terms-of-trade-driven welfare losses to U.S.natives from in-migration.704consequence of size.Rather than sliding down world demand curves for each variety,bigger economies may export more varieties to more countries.Or they may export higher-quality goods at higher prices.If variety and quality margins dominate,then growth and develop-ment economists must rely on other forces—such as technology diffusion and diminishing returns to capital—to tether the incomes of high-and low-investment economies.Further-more,the welfare effects of trade liberalization could be very different than is typically found in many CGE models.In this paper we use highly detailed1995 United Nations data on exports to assess the importance of the extensive,intensive,and quality margins in trade.The data cover exports from126countries to each of59importers in over5,000six-digit product categories.To check robustness we also examine exports by 124countries to the United States in1995in over13,000ten-digit product categories.We decompose a nation’s exports into contributions from intensive versus extensive margins,and further decompose the intensive margin into price and quantity components.We then relate each margin to country size(PPP GDP)as well as to its components:workers,and GDP per worker.Of special interest are the extensive and qual-ity margins.There are many possible ways to define the extensive margin(counting catego-ries exported,counting categories over a certain size,weighting categories in various ways).We measure the extensive margin in a manner con-sistent with consumer price theory by adapting the methodology in Robert C.Feenstra(1994), which appropriately weights categories of goods by their overall importance in exports to a given country.The quality margin is not di-rectly observable but can be inferred by exam-ining projections of price and quantity on GDP and its components.That is,if large exporters systematically sell high quantities at high prices,this is consistent with these exporters producing higher-quality goods.We also show alternatively how to interpret the projections of price and quantity in terms of unmeasured, within-category variety.Ourfindings are as follows.The extensive margin accounts for about60percent of the greater exports of larger economies.The inten-sive margins are dominated by higher quantities of each good rather than higher unit prices. Richer countries export higher quantities of each good at modestly higher prices,consistent with higher quality.Countries with more work-ers export higher quantities of each good,but not at higher prices.These patterns hold for both the U.N.data with broad geographic cov-erage,and U.S.data with more detailed product coverage.The large extensive margins are inconsistent with Armington models,which have no exten-sive margin and imply that larger economies face lower export prices.In contrast,Krugman-style models withfirm-level product differenti-ation predict that larger economies will produce and export more varieties,consistent with the large extensive margins wefind(assuming a strictly increasing relationship between variet-ies produced and varieties exported).However, these models predict that variety will expand in proportion to exporter size,which overstates the size of the observable extensive margin in the data.Further,the Krugman model predicts that a country will export to all markets if it exports to any markets in a category,a prediction strik-ingly at odds with the evidence.Countries typ-ically export to a strict subset of markets,with larger economies exporting to decidedly more markets.This suggests thatfixed costs of ex-porting a given product to a given market,as modeled by Paul Romer(1994),may be important.Our investigation builds on the empirical work of many predecessors.Feenstra(1994) applied his method to U.S.imports of six man-ufactured goods and found evidence of substan-tial import variety growth.Michael Funke and Ralf Ruhwedel(2001)found that the variety of both exports and imports are positively corre-lated with per capita income across19OECD countries.Keith Head and John Ries(2001) looked for home-market effects in U.S.and Canadian trade in order empirically to distin-guish increasing returns and national product differentiation models.They found the evidence mostly consistent with national product differ-entiation.By comparison,we examine model implications for extensive(increasing returns) versus intensive(national product differentia-tion)margins,along with price and quantity effects that each implies.Peter K.Schott(2004)705VOL.95NO.3HUMMELS AND KLENOW:THE VARIETY AND QUALITY OF A NATION’S EXPORTSfound that richer countries export to the U.S.at higher unit prices within narrow categories. Countries more abundant in physical and hu-man capital likewise export a given variety at higher unit prices.Like Schott,we use data on export prices in narrow categories for countries of differing income levels.Unlike his study,we examine a broad range of importers and use quantity data along with price data to extract information about quality differences.The rest of the paper proceeds as follows.In Section I we briefly outline the predictions of some trade models for the various margins.We discuss the data we use in Section II,and this guides how we define the extensive and inten-sive margins(and the latter’s price and quantity components)in Section III.In Section IV we present our empiricalfindings,and in Section V we offer conclusions and possible directions for future work.I.Export Margins in Various ModelsIn Table1we summarize what four trade models predict for the size of the intensive and extensive margins,and for the price and quan-tity components of the intensive margin.In all of these models,exporter variation in workers and productivity will cause variation in the quantity of output and exports,but along differ-ent margins.The predictions for the intensive and extensive margins are stark and well known,but the price and quantity variations within the intensive margin are more subtle.In the exposition below we describe the implica-tions of the models for prices and therefore the value of output for each exporter.Then,a pro-jection of each margin on output(or on output per worker and number of workers)provides information on how well the models describe the data.To help explain the Table1entries,consider the following general environment.Consumers in country m buy from up to J countries in each of I observable categories of goods.Goods are differentiated both across categories and across producing countries within categories.For ex-ample,midsize cars and trucks may be distinct observable categories,but within a category Japanese midsize cars are differentiated from German midsize cars.For simplicity we adopt a Dixit-Stiglitz formulation with a single elastic-ity of substitutionϾ1between goods in different categories and goods from different countries.Consumers maximize utility given by(1)U mϭͫjϭ1Jiϭ1I Q jmi N jmi x jmi1Ϫ1/ͬ/͑Ϫ1͒subject to(2)jϭ1Jiϭ1IN jmi p jmi x jmiՅY m.T ABLE1—M ODEL P REDICTIONS FOR E XPORT M ARGINSIntensive (px)Extensive(V)Price(p)Quantity(x)Armington10Ϫ1/(Ϫ1)/(Ϫ1)Acemoglu&VenturaY/L10Ϫ0.6 1.6L0100Krugman0100Qualitydifferentiation10Y/L10L01Notes:For discussion of each model,see Section I in the text.Entries are model predictionsfor how exports increase with respect to exporter size.A single entry indicates the sameelasticity with respect to both Y/L(GDP per worker)and L(employment).The Acemoglu andVentura price and quantity elasticities with respect to Y/L are equal toϪ1/(Ϫ1)and/(Ϫ1),but these take on the valuesϪ0.6and1.6for their case ofϭ2.6.706THE AMERICAN ECONOMIC REVIEW JUNE2005Here Q jmi is the quality of varieties exported by country j to country m in category i.2N jmi is the number of symmetric varieties exported from j to m within category i.(We assume for simplic-ity that these within-category varieties are sym-metric.)x jmi is the number of units(quantity) exported from j to m per variety in category i, and p jmi is the price of each of the units.If country m does not buy from country j in cate-gory i(say,because j does not produce any varieties in category i),then x jmiϭ0and N jmiϭ0.Y m is country m’s income.If midsize car models are an observable cat-egory,then Japan’s exporting of multiple,dif-ferentiated midsize car models to the United States would be an example of N jmiϾ1.Of course,the more disaggregated the trade data, the more cross-category variety is captured by the observable categories(the I’s).In the data section we examine the sensitivity of our results to changing levels of aggregation.And although unobserved,within-category varieties N are not directly distinguishable from quality Q,we will be able to draw some inferences about the role of each using price and quantity data.We now explain the entries in Table1.3In doing so we focus on exporter j variation that feeds into proportional variation across all mar-kets m and categories i.That is,market-specific and category-specific proportional constants are omitted.We also express all objects relative to an exporter for which the following variables are normalized to1:I,Q,N,x,p,A(productiv-ity),L(employment),and Y.We assume that A and L differ exogenously across countries.We summarize variety within and across categories as VϭNI(ϭ1in the reference country).A.ArmingtonIn Armington’s(1969)national differentia-tion model,each country produces a single va-riety in each category(V jϭ1for all j,given the normalization),so there is no extensive margin.Quality likewise does not vary across countries (Q jϭ1for all j).A country with more workers or higher productivity simply produces more of each variety(x jϭA j L j).This intensive margin results in lower prices for each variety.The effect on export prices is smaller the larger the elasticity of substitutionbetween varieties: p jϭ(A j L j)Ϫ1/.Country j’s GDP is Y jϭp j x j V jϭ(A j L j)1Ϫ1/.Taking logs and rearrang-ing,country j’s export quantities and prices can be expressed as(3)ln͑x j͒ϭϪ1ln͑Y j/L j͒ϩϪ1ln͑L j͒and(4)ln͑p j͒ϭϪ1Ϫ1ln͑Y j/L j͒ϩϪ1Ϫ1ln͑L j͒. These expressions are the basis of the price and quantity entries in thefirst row of Table1.In this Armington world,larger economies inten-sively export higher quantities at lower prices.4 Many CGE models of trade liberalization employ a modified Armington structure that differs from the stark assumptions in this base model.In particular,they employ exporter-specific weights in the utility function calibrated so that exporter prices and country size do not systematically co-vary in the cross section. These weights can be thought of as quality Q or unobserved variety N.Since the weights are fixed,however,the implications of the base Armington model still apply to time series.That is,changes in exporter size or income are pre-dicted to yield changes in output and prices as in first-differenced versions of equations(3)and (4).2We let quality enter the utility function without an exponent so that it is in“price units,”i.e.,equivalent to a lower price.This is purely a normalization.Quality is a demand shifter in(1),raising the quantity a country can export to a market at a given price.3We refer the reader to Hummels and Klenow(2002)for a more detailed exposition.4An alternative to expression(4)is ln(pj)ϭϪ1/ln(Aj)Ϫ1/ln(L j).For empirical estimation,this expres-sion would allow consistent estimation of the effect of exogenous variables.With(4),in contrast,the effect of employment on prices will be biased downward(upward in absolute terms).Higher L lowers income per worker for a given A,so controlling for Y/L requires a higher A.The coefficient on L in(4)therefore captures the effect on export prices of higher L,combined with enough higher A to keep Y/L unchanged.As we discuss below,we focus on(4) because Y/L is directly observable,whereas one must know (and quality if it varies across countries)to derive A.707VOL.95NO.3HUMMELS AND KLENOW:THE VARIETY AND QUALITY OF A NATION’S EXPORTSB.Acemoglu and Ventura Acemoglu and Ventura(2002)add endoge-nous capital accumulation and an endogenousnumber of varieties to the Armington model.They posit constant returns to capital in theproduction of each variety,and afixed laborrequirement for producing each variety.Thenumber of varieties a country produces is thenproportional to its employment(V jϭL j).A country with higher productivity(A j,broadlyconstrued to include physical capital)producesmore of each variety(x jϭA j).Higher produc-tion of each variety translates into lower prices for each variety:p jϭ(A j)Ϫ1/.Country j’s GDP is Y jϭp j x j V jϭ(A j)1Ϫ1/L j.Greater Y/L,but not greater L,is associated with producing higher quantities of each variety and selling them at lower unit prices:(5)ln͑x j͒ϭϪ1ln͑Y j/L j͒and(6)ln͑p j͒ϭϪ1Ϫ1ln͑Y j/L j͒.The second row of Table1summarizes this model’s predictions.C.KrugmanKrugman(1979,1980,1981)modeled coun-tries as producing an endogenous number of varieties.5Withfixed output costs of producing each variety,the number of varieties produced in a country is proportional to the size of the economy(V jϭY jϭA j L j).In this simplest Krugman world,all countries export the same quantity per variety(x jϭ1for all j)and exportat the same unit prices(p jϭ1for all j).Neither unit prices nor quantity per variety vary with GDP per worker or the number of workers. These results are stated in the third row of Ta-ble1.The Krugman model has the property that, conditional on producing a variety,a country exports this variety to all other markets.A cor-ollary is that,conditional on exporting in a category,a country exports in this category to all other countries.In models withfixed costs of exporting to each market,such as Romer (1994),a country may instead export to a strict subset of markets,or even to no markets at all despite producing in the category.When we discuss our empiricalfindings in Section IV below,we will present evidence on export des-tinations to address this issue.D.Quality Differentiation Suppose quality varies across countries(Q j differs across j)but productivity and variety do not(A jϭ1and V jϭ1for all j).Countries withmore workers produce more of each variety (x jϭL j).A country’s unit prices reflect both the level of employment and the level of quality: p jϭQ j(L j)Ϫ1/.GDP is Y jϭQ j(L j)1Ϫ1/.Also, Y j/L jϭQ j(L j)Ϫ1/ϭp j.Quantity per variety should positively project on exporter employ-ment but be unrelated to exporter GDP per worker;prices for varieties should project pos-itively on GDP per worker but be unrelated to employment.These results are shown in the final row of Table1.More generally,we can use consumerfirst-order conditions from(1)and(2)to express quality and within-category variety in terms of the observed prices and quantities and the elas-ticity of substitution between varieties:(7)ln͑Q j͒ϩ1ln͑N j͒ϭln͑p j͒ϩ1ln͑N j x j͒. Note that the observed quantities per category are actually Nx,rather than the theoretically ideal x.Also note that quality and within-category variety are isomorphic(up to a scalar) in this expression.We return to this issue when discussing the empirical results.II.Data DescriptionWe draw export data from two sources.We use worldwide data from the United Nations Confer-ence on Trade and Development(UNCTAD) Trade Analysis and Information System (TRAINS)CD-ROM for1995.The TRAINS project combines bilateral import data collected5See also Wilfred J.Ethier(1979,1982).708THE AMERICAN ECONOMIC REVIEW JUNE2005by the national statistical agencies of76import-ing countries,covering all exporting countries (227in1995).The data are reported in the Harmonized System(HS)classification code at the six-digit level,or5,017goods,and include shipment values and quantities.For a subset of these countries(126of the227exporters and59 of the76importers),we have matching employ-ment and GDP data(discussed below).The59 importers represent the vast majority of world imports,so total shipments for each exporter reported in TRAINS closely approximate worldwide shipments for that exporter.Our calculation of the extensive margin may be sensitive to the level of aggregation at which we measure exports.That is,a country may export total variety VϭNI,but only categories I are observable.As data become more aggre-gated,variety shifts from the observable I to the unobservable within-category N.For example, were we to use the output data available in internationally comparable form at roughly the two-digit level,we wouldfind that most coun-tries produce and export in all sectors.6We would then obtain much smaller extensive mar-gins,with most variety differences relegated to the intensive margin.By using more detailed export data with5,017six-digit HS categories, we can do a better job of assigning variety differences to the extensive margin.We also use U.S.data with more product detail from the“U.S.Imports of Merchandise”CD-ROM for1995,published by the U.S.Bu-reau of the Census.The data are drawn from electronically submitted customs forms that re-port the country of origin,value,quantity, freight paid,duties paid,and HS code for each shipment entering the United States.The ten-digit HS scheme includes13,386highly de-tailed goods categories.The data include all countries shipping to the United States,a total of222in1995.We have data on employment and output in1995for124of these exporters.7 In both datasets,we measure prices as unit values(value/quantity).Quantity(and therefore price)data are missing for approximately16 percent of U.S.observations and18percent of worldwide observations for1995.8When the U.S.data include multiple shipments from an exporter in a ten-digit category,we aggregate values and quantities.The resulting prices are quantity-weighted averages of prices found within shipments from that exporter category. Data on national employment and GDP at 1996international(PPP)prices come from Alan Heston et al.(2002).We use PPP GDP,as opposed to GDP at current market exchange rates,to avoid any mechanical association be-tween an exporter’s price and GDP through the value of its market exchange rate.All of our empirical results are robust to using GDP val-ued at market exchange rates instead of PPP exchange rates.III.Decomposition MethodologyWe now construct empirical counterparts to the intensive margin(px),the category exten-sive margin(I),and the price(p)and quantity (x)components of the intensive margin.To do so,we adapt Feenstra’s(1994)methodology for incorporating new varieties into a country’s im-port price index when preferences take the form of our equation(1).Feenstra shows that the import price index is effectively lowered when the set of goods expands.Instead of comparing varieties imported over time,we compare varieties imported from dif-ferent exporters at a point in time.In this case, comparing export prices for country j relative to a reference country k requires an adjustment for the size of each exporter’s goods set.The ap-propriate adjustment is the extensive margin. For the case when j’s shipments to m are a6Prominent CGE models typically feature fewer than50 manufactured goods,primarily because of the dearth of output data,and therefore include no extensive margins in their analysis.The most disaggregated model we couldfindin the CGE literature is that employed by the U.S.Interna-tional Trade Commission.It has roughly500sectors,still an order of magnitude fewer than the six-digit HS codes we use.Also,its structure is fundamentally different from the models under consideration here.It has a United States versus rest-of-world focus,contains no data on rest-of-world output,and allows for no cross-country differences in varieties either in cross section or over time.7The remaining98,primarily very small or former Soviet-bloc countries,comprise only5percent of U.S.trade in1995.8The likelihood that quantity data are missing is uncor-related with aggregate employment and GDP per worker,so our analyses should not be biased by dropping these observations.709VOL.95NO.3HUMMELS AND KLENOW:THE VARIETY AND QUALITY OF A NATION’S EXPORTSsubset of k’s shipments to m,the extensive margin is defined as(8)EM jmϭ¥iʦI jmp kmi x kmi iʦIkmi kmi.This is a cross-exporter analogue of Feenstra’snew varieties adjustment to an import priceindex.I jm is the set of observable categories inwhich country j has positive exports to m,i.e.,x jmiϾ0.(In our empirical implementation,the I categories will be5,017six-digit U.N.HS product codes.)Reference country k has posi-tive exports to m in all I categories.(In ourempirical implementation,k will be rest-of-world.)EM jm equals country k’s exports to m inI jm relative to country k’s exports to m in all Icategories.The extensive margin can be thought of as aweighted count of j’s categories relative to k’scategories.If all categories are of equal impor-tance,then the extensive margin is simply thefraction of categories in which j exports to m.More generally,categories are weighted bytheir importance in k’s exports to m.An advan-tage of evaluating a category’s importance with-out reference to j’s exports is that it prevents acategory from appearing important solely be-cause j(and no other country)exports a lot to min that category.9The corresponding intensive margin com-pares nominal shipments for j and k in a com-mon set of goods.It is given by(9)IM jmϭ¥iʦI jmp jmi x jmi ¥iʦI jmp kmi x kmi.IM jm equals j’s nominal exports relative to k’s nominal exports in those categories in which j exports to m(I jm).The ratio of country j to country k exports to m equals the product of the two margins:(10)¥iϭ1Ip jmi x jmi¥iϭ1Ip kmi x kmiϭIM jm EM jm.To see a simple example of the intensive versus extensive decomposition,compare German and Belgian exports to the United States,using kϭrest-of-world for the reference country in each case.Given the size of each,it is not surprising that Germany’s exports to the United States are 6.2times larger than Belgium’s.Some of this comes through a greater number of categories shipped—Germany ships in79percent of the 5,017six-digit HS codes,while Belgium ships in51percent.Were all categories of equal weight,this would yield an extensive margin for Germany that is1.55times larger than Bel-gium’s.This leaves an intensive margin(i.e., exports per category)for Germany that is four times larger than Belgium’s.However,not all categories are of equal weight.Germany ships in categories that are a larger share of rest-of-world exports to the United States,the numer-ator in equation(8).Incorporating the weighted counts,Germany’s extensive margin is 1.65 times greater than Belgium’s,and its intensive margin is3.75times larger.We now turn to decomposing the intensive margin into price and quantity indices.Suppose that quality(Q)and within-category variety(N) vary across categories i for each importer m. This encompasses preferences that place more weight on some goods than on others.As a baseline case,assume further that quality and within-category variety do not vary by exporter. (In our empirical analysis,we will test these assumptions.)For this baseline case,Feenstra (1994)derives an exact price index for the in-tensive margin of country m’s imports from j versus k:(11)P jmϭiʦI jmͩp jmi p kmiͪw jmi.In(11),w jmi is the logarithmic mean of s jmi(the9A disadvantage is that a country may appear to havea large extensive margin because it exports a smallamount in categories in which k exports a lot.As wediscuss in the next section,we do notfind this to be thecase empirically.710THE AMERICAN ECONOMIC REVIEW JUNE2005。

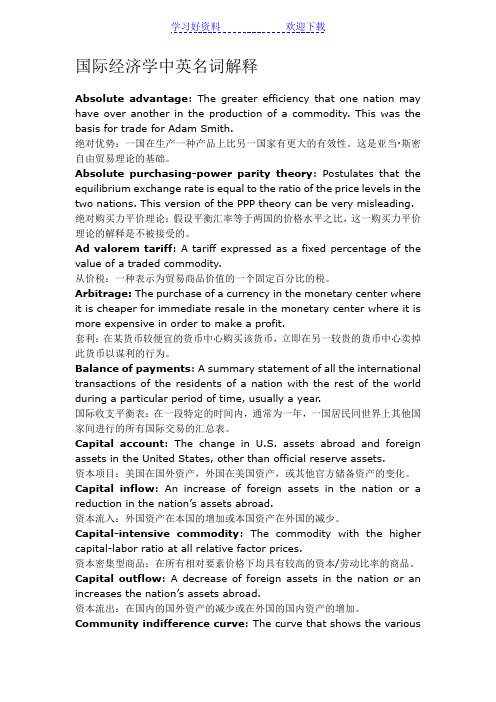

国际经济学中英名词解释

国际经济学中英名词解释Absolute advantage: The greater efficiency that one nation may have over another in the production of a commodity. This was the basis for trade for Adam Smith.绝对优势:一国在生产一种产品上比另一国家有更大的有效性。

这是亚当·斯密自由贸易理论的基础。

Absolute purchasing-power parity theory: Postulates that the equilibrium exchange rate is equal to the ratio of the price levels in the two nations. This version of the PPP theory can be very misleading. 绝对购买力平价理论:假设平衡汇率等于两国的价格水平之比,这一购买力平价理论的解释是不被接受的。

Ad valorem tariff: A tariff expressed as a fixed percentage of the value of a traded commodity.从价税:一种表示为贸易商品价值的一个固定百分比的税。

Arbitrage: The purchase of a currency in the monetary center where it is cheaper for immediate resale in the monetary center where it is more expensive in order to make a profit.套利:在某货币较便宜的货币中心购买该货币,立即在另一较贵的货币中心卖掉此货币以谋利的行为。

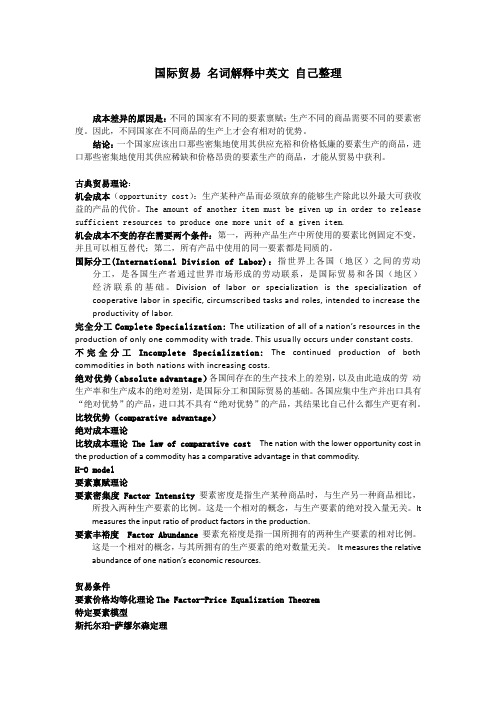

国际贸易 名词解释中英文 自己整理

国际贸易名词解释中英文自己整理成本差异的原因是:不同的国家有不同的要素禀赋;生产不同的商品需要不同的要素密度。

因此,不同国家在不同商品的生产上才会有相对的优势。

结论:一个国家应该出口那些密集地使用其供应充裕和价格低廉的要素生产的商品,进口那些密集地使用其供应稀缺和价格昂贵的要素生产的商品,才能从贸易中获利。

古典贸易理论:机会成本(opportunity cost):生产某种产品而必须放弃的能够生产除此以外最大可获收益的产品的代价。

The amount of another item must be given up in order to release sufficient resources to produce one more unit of a given item.机会成本不变的存在需要两个条件:第一,两种产品生产中所使用的要素比例固定不变,并且可以相互替代;第二,所有产品中使用的同一要素都是同质的。

国际分工(International Division of Labor):指世界上各国(地区)之间的劳动分工,是各国生产者通过世界市场形成的劳动联系,是国际贸易和各国(地区)经济联系的基础。

Division of labor or specialization is the specialization of cooperative labor in specific, circumscribed tasks and roles, intended to increase the productivity of labor.完全分工Complete Specialization: The utilization of all of a nation’s resources in the production of only one commodity with trade. This usually occurs under constant costs. 不完全分工Incomplete Specialization: The continued production of both commodities in both nations with increasing costs.绝对优势(absolute advantage)各国间存在的生产技术上的差别,以及由此造成的劳动生产率和生产成本的绝对差别,是国际分工和国际贸易的基础。

曼昆经济学原理-第十章-外部性

Social value

0

OPTIMUM MARKET

Quantity 0

of Alcohol

Social

value

Demand

(private value)

QQ MARKET OPTIMUM

Quantity of Education

The Equivalence of Pigovian Taxes and Pollution Permits...

机器人的数量

Positive Externalities in Production

需求曲线与社会成本曲线的交点决定了社 会最适的产量水平。

最适产量水平超过均衡水平。 市场的生产量小于社会的合意数量。 生产的社会成本小于生产与消费的私人成本 。

外部性内在化: 补贴

政府多次使用补贴作为主要的方 式来尝试使正外部性内部化。

外部性内在化(Internalizing an externality )指改变激励,以使人 们考虑到自己行为的外部性。

Achieving the Socially Optimal Output

政府可以通过向生产者征税使外部 性内在化,从而均衡量减少到社会 最适水平。

生产产品的正外部性

当外部性给旁观者带来利益,正的外部 性就出现了。

Price of Aluminum

Cost of pollution

Social cost

Supply

(private cost)

Optimum

Equilibrium

Demand

(private value)

0

Qoptimum QMARKE

T

宏观经济第30章货币增长和通货膨胀(题目+答案+详解)

宏观经济第30章货币增长和通货膨胀(题目+答案+详解)第30章货币增长和通货膨胀1. The value of moneya. is constant.b. is positively related to the price level.c. is determined by the supply and demand of money.d. is not explained by the quantity theory of money.2. The quantity of money demanded isa. positively related to the money supply.b. negatively related to the money supply.c. negatively related to the price level.d. positively related to the price level.3. Interest rates stated in The Wall Street Journal area. classical variables.b. dichotomous variables.c. nominal variables.d. real variables.4. According to the principle of monetary neutrality, a decrease in the money supply willa. increase real GDP.b. not affect unemployment.c. not affect the price level.d. decrease real interest rates.5. If money is neutral and velocity is stable, an increase in the money supply creates a proportional increase ina. real output.b. nominal output.c. the price level.d. Both b and c are correct.6. A decrease in the money supply creates an excessA.supply of money that is eliminated by rising prices.B.supply of money that is eliminated by falling prices.C.demand for money that is eliminated by rising prices.D.demand for money that is eliminated by falling prices7. When the money market is drawn with the value of money on the vertical axis, the price level decreases ifA.either money demand or money supply shifts right.B.either money demand or money supply shifts left.C.money demand shifts right or money supply shifts left.D.money demand shifts left or money supply shifts right.8. The cost of changing price tags and price listings is known asa. inflation-induced tax distortions.b. relative-price variability costs.c. shoeleather costs.d. menu costs.9. People can avoid the inflation tax bya. not holding money.b. not filing a tax return.c. holding all their wealth as cash.d. None of the above are correct.10. Wealth is distributed from debtors to creditors when inflation isa. high, but expected.b. low, but expected.c. unexpectedly high.d. unexpectedly low.11. High and unexpected inflation has a greater costa. for those who borrow, than those who save.b. for those who hold a lot of money, than those who hold a little.c. for those whose wages increase by as much as inflation, than those who are paid a fixed nominal wage.d. Both a and b are correct.12 If inflation is more than expected,a. debtors receive a higher real interest rate than they had anticipated.b. debtors pay a higher real interest rate than they had anticipated.c. creditors receive a lower real interest rate than they had anticipated.d. creditors pay a lower real interest rate than they had anticipated.答案:CDCBDDCDADBC12C:creditor 债权人;debtor 债务人;当通货膨胀上升时,名义利率上升,债务的实际价值下降,使债务人受益,债权人受损。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。