ASA围术期急性疼痛管理指南

围术期疼痛管理

Combined general and continuous regional anaesthesia for extensive shoulder or humerus/elbow surgery is frequently used in Europe

精选课件

Combined General and Regional Anaesthesia for Elderly Patients Perioperative pain management for tibia plateau fracture with continuous lateral popliteal block in an 82 years old lady

镇痛方法的联合应用

椎管内阻滞

(硬膜外、鞘内)

外周神经阻滞

(区域阻滞、神经干阻滞)

多模式镇痛

局部浸润

(关节内, 切口)

全身性镇痛

(NSAIDs, 曲马多, 阿片类)

Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2014 Mar;28(1):59-79.

精选课件

• 299 项随机对照研究

Br J Anaesth. 1989 Aug;63(2):189-95.

多模式镇痛:

联合使用作用机制不同的镇痛药物或 镇痛方法。由于作用机制不同而互补,镇 痛作用相加或协同,同时每种药物的剂量 减小。不良反应相应降低,从而达到最大 的效应/副作用比。

精选课件

成人术后疼痛处理专家共识. 2014.

药物镇痛靶点

术后慢性痛普遍存在

英国、美国术后慢性疼痛发生率(2007年)

从腹股沟疝修补术到体循环大手术,术后慢性痛普遍存在,其发生率高达19%56%,持续痛可达半年甚至数十年。-中国成人术后疼痛处理专家共识(2009版)

复合手术室的建设与管理

手术室体现代表着现代化医院的设施、医疗、管理水 平[2],其空间布局设计的合理性可以适当减轻护理人 员相关工作量,提高医生及影像技师等相关人员的工

ห้องสมุดไป่ตู้

3

齐鲁护理杂志 2019年 1月第 25卷第 2期

作效率,同时实现了术中手术室与其他科室的无缝连 接,在完成示教、远程沟通等方面起着重要的作用[3]。 技术革新面前,我们面临的既是机遇又是挑战。认识 到复合手术室的必要性和重要性,其建立之后所产生 的护理、管理等问题需要我们不断地学习、思考。 1 复合手术室的建设 1.1 尺寸及布局 复合手术室包括手术间、设备遥 控操作间、数字化示教室、设备间、谈话间,一体化的 手术室布局需同时满足空间、设备、信息和图文数据 传输的整合要求。相比于普通手术间其要求设置空 间较大,一般净面积≥50m2[4]。 1.2 复合手术室的设备配置 1.2.1 DSA与手术床 临床上将 DSA作为手术室 的核心工作平台,它可以实时采集、储存、处理各种血 管造影图像[5]。目前的复合手术室 DSA配置拥有单 C臂系统与双 C臂系统,落地式 C臂系统与悬吊 C 臂系统。应用 DSA不仅可以完成常规手术,还可以 实现影像设备下的血管造影和内外科的介入治疗及 手术,有 DSA影像处理及信息辅助,提高了手术及介 入治疗的成功率和效率[2]。DSA的配备需遵循机架 灵活,提供大范围地投照视野和大范围移位,图像质 量清晰,在达到诊断要求的情况下尽量减少 X线辐 射剂量的原则。手术床既要满足外科专业,又要能与 血管造影系统紧密结合,实现手术床和 DSA在一个 界面上 控 制[2]。床 体 本 身 固 定,要 求 轻 巧、移 动 灵 活,有较好的 X线透光性及与 C型臂同步可控,以便 调节手术体位。 1.2.2 手术吊塔和无影手术灯 外科塔、麻醉塔和 腔镜及显示器塔等多采用多臂双塔结构,可升降旋转 并具有较强的承载力,并在 1m的范围内任意旋转, 可停在医护人员触手可及的位置。由于 DSA安装位 置的关系,要求无影灯的旋转范围大,应使用照明亮度 大,使用寿命长的 LED冷光源,无影灯满足手术的同 时,还需满足层级净化空气流动的要求[2],此外应避免 与其他悬吊设备碰撞。常规手术设备应根据手术使用 顺序在手术床周围和吊塔上合理布局,设备都要符合 人体工效学设计原则,以满足实际使用需求。 1.3 数字化多媒体的整合 将患者的影像、检验、术 中信息等进行整合,完成与医院 HIS、PACS的连接, 在手术室即可同步实现患者信息的存储、查阅及患者 各项资料的整合。搭建一套功能强大的视音频管理 系统,有利于实现复合手术室手术院内外转播、示教 以及双向交流示教与远程转播、会诊的重要功能。建 议在数字化手术室建立的初期充分调研医护技需求, 在此基础上不断修正合理设计信号传递数量和方式,

NBAS-APS模式在脆性骨折患者围手术期疼痛管理中的应用

疼痛宣教

医护态度

医护技能

情感体验

28.15±2.38

25.58±3.96

20.19±4.20

17.42±3.16

8.917

5.558

3.202

5.612

33.16±2.03

t值

30.26±2.51

0.000

P值

23.22±3.18

0.000

0.002

21.33±2.25

0.000

痛宣教(12 个条目) 、医护态度(11 个条目) 、医护技

当天即开始对患者及家属进行知识宣教,教会患者

能(9 个条目) 以及情感体验( 8 个条目) 4 个部分,3

疼痛评估法和非药物镇痛的方法( 如转移注意力、

级评分法,分值越高,满意度越佳。 该表 Cronbach’ s

呼吸训练) ,鼓励其正确表达疼痛。 ②责任护士需

体肿胀、畸形所致的疼痛,还是术后机体损伤、手术

纳入标准:①影像学检查确诊为脆性骨折;②能

刺激引发的心理及生理系列反应,均会影响患者饮

够耐受手术;③同意参与研究。 排除标准:①肢体功

食、睡眠及心肺功能恢复,延长住院时间 [3] ,如若治

疗不 当, 极 易 发 展 为 慢 性 疼 痛, 增 加 患 者 痛 苦

医师( 手术前后依据 VAS 评分调整疼痛管理方案) ;

值越高睡眠越差 [6] 。 ③ 采用科室自制的患者疼痛

表分值 0 ~ 21,PSQI 总分> 7 分提示有睡眠障碍,分

患者的疼痛管理及术后 PCA 的指导和随访) 、临床

(2) NBAS⁃APS 模式的实施:①责任护士于患者入院

管理满意度量表于出院时评估患者满意度,包含疼

河北省2020毒麻药品好医生培训答案

一共50道题,每页10道题* (1) 医疗机构应对麻醉药品处方单独存放,至少保存* A.半年* B.一年* C.两年* D.三年* (2) 下列哪种镇静药物可导致高甘油三酯血症* A.地西泮* B.苯巴比妥* C.咪唑安定* D.丙泊酚* E.右美托咪定* (3) WHO“三阶梯”癌痛治疗原则不包括* A.注射给药* B.按时给药* C.按阶梯给药* D.个体化给药* (4) 关于超前镇痛,不正确的是* A.特指在“切皮前”所给予的镇痛方法* B.指在术前、术中和术后通过减少有害刺激传入所导致的外周和中枢敏感化* C.外周的敏感化降低传入神经末梢的痛阈,直接导致了术中常见的疼痛高敏状态,即对疼痛敏感的增加和痛阈的下降* D.降低外周敏感化,在于对外周神经背根神经节的干预,是进行超前镇痛的有效方法* (5) RASS评分中“-2分”对应的是* A.躁动焦虑* B.有攻击性* C.轻度镇静* D.昏昏欲睡* E.不可唤醒* (6) 建议对于( )且具有谵妄相关危险因素的ICU患者应常规进行谵妄评估* A.RASS评分≥+4分* B.RASS评分≥+2分* C.RASS评分≥0分* D.RASS评分≥-2分* E.RASS评分≥-5分* (7) 关于阿片类药物不良反应的说法错误的是* A.阿片类药物大多数不良反应是暂时性的,也是可以耐受的* B.常见于用药初期或过量用药时* C.一旦出现不良反应就立即停药或换药* D.应采取必要的预防措施* (8) 对于老年人、或ASAⅢ级患者推荐使用的液体管理策略* A.非限制性补液* B.限制性补液* C.目标导向液体治疗* D.生理需要量+失血量* (9) 对于癌痛病人,阿片类药物推荐哪个用药途径* A.口服给药* B.注射给药* C.舌下给药* D.直肠给药* (10) 关于阿片类药物是否可以用于肺癌患者疼痛的治疗,下列说法中错误的是* A.阿片类药物引起的呼吸抑制是对呼吸中枢抑制的副作用所致,阿片类药本身不会加重肺部病变* B.阿片类药对呼吸中枢抑制的副作用, 一般仅发生在用药过量时或肾功能不全导致药物蓄积时,临床实践证明此药可以安全有效缓解肺癌患者的疼痛* C.肺癌疼痛患者使用阿片类药物镇痛时,也一定要遵循用药规X* D.阿片类药具有呼吸抑制的副作用,因此不能用于肺癌患者疼痛的治疗* (11) 疼痛治疗的一般原则中,以下哪项不正确* A.对轻、中度疼痛, 一般采用针灸或解热镇痛药或物理疗法止痛即可。

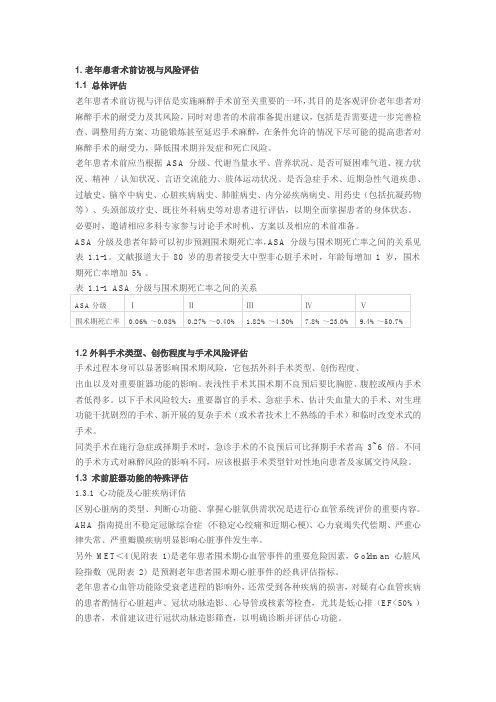

中国老年患者围术期麻醉管理指导意见

1.2 外科手术类型、创伤程度与手术风险评估手术过程本身可以显著影响围术期风险,它包括外科手术类型、创伤程度、出血以及对重要脏器功能的影响。

表浅性手术其围术期不良预后要比胸腔、腹腔或颅内手术者低得多。

以下手术风险较大:重要器官的手术、急症手术、估计失血量大的手术、对生理功能干扰剧烈的手术、新开展的复杂手术(或术者技术上不熟练的手术)和临时改变术式的手术。

同类手术在施行急症或择期手术时,急诊手术的不良预后可比择期手术者高3~6 倍。

不同的手术方式对麻醉风险的影响不同,应该根据手术类型针对性地向患者及家属交待风险。

1.3 术前脏器功能的特殊评估1.3.1 心功能及心脏疾病评估区别心脏病的类型、判断心功能、掌握心脏氧供需状况是进行心血管系统评价的重要内容。

AHA 指南提出不稳定冠脉综合症(不稳定心绞痛和近期心梗)、心力衰竭失代偿期、严重心律失常、严重瓣膜疾病明显影响心脏事件发生率。

另外MET<4(见附表1)是老年患者围术期心血管事件的重要危险因素,Goldman 心脏风险指数(见附表2) 是预测老年患者围术期心脏事件的经典评估指标。

老年患者心血管功能除受衰老进程的影响外,还常受到各种疾病的损害,对疑有心血管疾病的患者酌情行心脏超声、冠状动脉造影、心导管或核素等检查,尤其是低心排(EF<50%)的患者,术前建议进行冠状动脉造影筛查,以明确诊断并评估心功能。

对于高血压病患者宜行动态血压监测,检查眼底并明确有无继发心、脑、肾并发症及其损害程度。

对心率失常或心肌缺血患者应行动态心电图检查。

室壁瘤的患者,术前应该根据超声检查筛查是否真性室壁瘤。

另外应根据AHA 指南对合并有心脏病的患者进行必要的处理。

改良心脏风险指数(RCRI)(见附表3) 简单明了,在老年患者术后重大心血管事件的预测中具有重要作用,其内容包括:⑴高风险手术;⑵心力衰竭病史;⑶缺血性心脏病史;⑷脑血管疾病史;⑸需要胰岛素治疗的糖尿病;⑹血清肌酐浓度>2.0mg/dL。

急性疼痛服务模式对食管癌患者围术期疼痛情况、睡眠质量及生命质量的影响观察

2018 世界睡眠医学杂志WorldJournalofSleepMedicine2023年9月第10卷第9期September.2023,Vol.10,No.9急性疼痛服务模式对食管癌患者围术期疼痛情况、睡眠质量及生命质量的影响观察胡 燕(中山大学肿瘤防治中心综合中医科,广州,510060)摘要 目的:观察以护士为基础、以麻醉医师和专科医师为指导的急性疼痛服务(NBASS APS)模式对食管癌患者围术期疼痛情况、睡眠质量及生命质量的影响。

方法:选取2021年2月至2023年2月中山大学肿瘤防治中心收治的食管癌患者80例作为研究对象,按照NBASS APS模式实施时间分为对照组和观察组,每组40例。

2021年2月至2022年2月NBASS APS模式实施前的40例患者设为对照组,2022年3月至2023年2月实施后的40例患者设为观察组,对照组采取常规护理,观察组实施NBASS APS模式干预,比较2组围术期疼痛情况、睡眠质量及生命质量。

结果:2组术前、术后6h、术后1d及术后2d时的视觉模拟评分法(VAS)评分时间、组间及交互效应比较,差异有统计学意义(F=63 380、86 650、18 760,P<0 05);观察组术后6h、术后1d及术后2d时VAS评分均显著低于对照组,差异有统计学意义(P<0 05);2组术前、术后1d、术后3d及术后7d时的匹兹堡睡眠质量指数(PSQI)评分时间、组间及交互效应,差异有统计学意义(F=431 800、151 400、13 940,P<0 05);观察组术后1d、术后3d及术后7d时PSQI评分均显著低于对照组,差异有统计学意义(P<0 05);干预后,观察组健康调查简表(SF 36)中生理功能、生理职能、情感职能、活力、躯体疼痛、精神健康及总体健康较干预前明显升高,且高于对照组,差异有统计学意义(P<0 05)。

结论:NBASS APS模式可缓解食管癌患者术后疼痛,改善睡眠及生命质量。

关于印发术后镇痛操作规范及流程的通知

关于印发术后镇痛操作规范及流程的通知各临床科室:术后疼痛是手术后即刻发生的临床最常见最需紧急处理的伤害性急性疼痛。

术后镇痛是麻醉医生的重要工作,对于建立无痛医院,保证患者围术期的医疗质量与安全都有重要意义。

麻醉科医生要大力倡导手术后全程无痛、舒适化医疗理念。

一、术后镇痛要坚持患者自愿原则,安全第一的思想,保证镇痛效果,减少或避免副作用。

二、术后镇痛必须强调个体化用药,发挥团队精神,加强对病人的管理与监测,体现人性化服务。

三、术后镇痛要按照中华医学会麻醉学分会《加速康复外科理念下疼痛管理专家共识》、《成人手术后疼痛处理专家共识》、《小儿术后镇痛专家共识》、《术后恶心呕吐防治专家共识》等专家意见作为依据。

四、术后镇痛实行麻醉科镇痛访视医师、经治医师随访负责制度,严格按照麻醉医师资格分级授权管理和再评价机制开展工作。

即经治医师负责向家属、病人或者委托人交代术后镇痛的知情同意书内容并签字,把握适应症,穿刺置管固定,配药、给预置量,向家属、病人或者委托人交代注意事项;在术后镇痛记录单上注明术后镇痛的类型(PCEA、PCIA)、配方、持续量、追加量(PCA), 给预置量的时间、药物;在术后镇痛随访登记本上记录时间、科别、床号、住院号、手术名称、镇痛方式等;在镇痛泵上注明患者姓名、性别、科别、床号、住院号、药物、术后镇痛的类型(PCEA、PCIA)等。

五、轮班麻醉医师负责科室全部术后镇痛病人的随访,包括加药、处理副作用和或并发症、拔泵等,评估镇痛药物效果、药量及副作用,负责与病人所在科室医生沟通交流等等;确保每天访视次数及访视质量,麻醉科常规每天两次访视,其中麻醉科医师负责每日早晨晨会交班后做晨访视并在第二天晨会报告科室术后镇痛患者情况、如有特殊情况全科讨论,每日下午下班前主管麻醉医师须再次访视病人,如遇特殊情况需向值班医生交班增加随访观察次数。

术后镇痛病人在全天出现有需要解决的问题访视医师随时处理。

术后镇痛经治医师对该病人所做的工作负责并承担责任。

围手术期主要镇痛药物对比(最新)

保护胃肠 调节血小板聚集

抗炎镇痛

药物选择

• 《美国术后疼痛管理指南》(2016 年)指出:术前可给予患者口 服塞来昔布以减轻术后疼痛,减少术后阿片类药物的用量。

• 不推荐在术前给予阿片类药物或非选择性 NSAIDs,因为不能从中 获益。

• 《成人手术后疼痛处理专家共识》(2017 年)指出:术前使用 COX-2 抑制剂(如口服塞来昔布或静注帕瑞昔布)可发挥抗炎、 抑制中枢和外周敏化作用。

不同NSAIDs的作用机制不同,安全性不同

选择性COX-2抑制剂胃肠道安全性好,不影响血小板聚集

非选择性NSAIDs(酮洛酸、氟比洛芬酯)

花生四烯酸

COX-1

COX-2

选择性COX-2抑制剂(如帕瑞昔布)

花生四烯酸

COX-1

COX-2

前列腺素

前列腺素

前列腺素

前列腺素

消化道损伤 血小板功能抑制

抗炎镇痛

危重症患者镇静药物持续应用的临床指南

镇静药物的选择

• 1. 急性躁动患者使用咪达唑仑或安定来快速镇静 • 2.丙泊酚适用于需要快速清醒的患者 • 3.谵妄状态首选氟哌啶醇

危重症患者镇静药物持续应用的临床指南

镇静药物对比

内容 类别 作用机制

适应症 首剂后起效时间

不良反应

咪达唑仑注射液 苯二氮卓类

→作 用 于 下 丘 脑 , 产 生 非 自 然 睡 眠 → 不易唤醒

药物合理使用

• 临床药师需从配伍禁忌、药物特点、患者情况、不同 PCA 给药方式等多 个方面评估镇痛泵中药物使用是否合理。

• 配伍禁忌:虽然多项指南对多种药物在术后 PCA 中的使用方式进行了推 荐,但仍需分析这几种药物合用是否存在配伍禁忌,尤其是长时间混合 的稳定性。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

SPECIAL ARTICLESPractice Guidelines for Acute Pain Management in the Perioperative SettingAn Updated Report by the American Society ofAnesthesiologists Task Force on Acute Pain ManagementPRACTICE Guidelines are systematically developed rec-ommendations that assist the practitioner and patient in making decisions about health care.These recommenda-tions may be adopted,modified,or rejected according to clinical needs and constraints and are not intended to replace local institutional policies.In addition,Practice Guidelines de-veloped by the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA)are not intended as standards or absolute requirements,and their use cannot guarantee any specific outcome.Practice Guidelines are subject to revision as warranted by the evolution of medical knowledge,technology,and practice.They provide basic rec-ommendations that are supported by a synthesis and analysis ofthe current literature,expert and practitioner opinion,open fo-rum commentary,and clinical feasibility data.This document updates the “Practice Guidelines for Acute Pain Management in the Perioperative Setting:An Updated Report by the American Society of Anesthesiolo-gists Task Force on Acute Pain Management,”adopted by the ASA in 2003and published in 2004.*MethodologyA.Definition of Acute Pain Management in the Perioperative SettingFor these Guidelines,acute pain is defined as pain that is present in a surgical patient after a procedure.Such pain may be the result of trauma from the procedure or procedure-related complications.Pain management in the perioperative setting refers to actions before,during,and after a procedureUpdated by the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA)Com-mittee on Standards and Practice Parameters,Jeffrey L.Apfelbaum,M.D.(Committee Chair),Chicago,Illinois;Michael A.Ashburn,M.D.,M.P.H.(Task Force Chair),Philadelphia,Pennsylvania;Richard T.Con-nis,Ph.D.,Woodinville,Washington;Tong J.Gan,M.D.,Durham,North Carolina;and David G.Nickinovich,Ph.D.,Bellevue,Washing-ton.The previous update was developed by the ASA Task Force on Acute Pain Management:Michael A.Ashburn,M.D.,M.P.H.(Chair),Salt Lake City,Utah;Robert A.Caplan,M.D.,Seattle,Washington;Daniel B.Carr,M.D.,Boston,Massachusetts;Richard T.Connis,Ph.D.,Woodinville,Washington;Brian Ginsberg,M.D.,Durham,North Car-olina;Carmen R.Green,M.D.,Ann Arbor,Michigan;Mark J.Lema,M.D.,Ph.D.,Buffalo,New York;David G.Nickinovich,Ph.D.,Belle-vue,Washington;and Linda Jo Rice,M.D.,St.Petersburg,Florida.Received from the American Society of Anesthesiologists,Park Ridge,Illinois.Submitted for publication October 20,2011.Accepted for publication October 20,2011.Supported by the American Society of Anesthesiologists and developed under the direction of the Committee on Standards and Practice Parameters,Jeffrey L.Apfelbaum,M.D.(Chair).Approved by the ASA House of Delegates on October 19,2011.A complete list of references used to develop these updated Guidelines,arranged alphabeti-cally by author,is available as Supplemental Digital Content 1,/ALN/A780.Address correspondence to the American Society of Anesthesi-ologists:520North Northwest Highway,Park Ridge,Illinois 60068-2573.These Practice Guidelines,as well as all published ASA Prac-tice Parameters,may be obtained at no cost through the Journal Web site,.*American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Acute Pain Management:Practice guidelines for acute pain management in the perioperative setting:An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Acute Pain Management.A NESTHESIOLOGY 2004;100:1573–81.Copyright ©2012,the American Society of Anesthesiologists,Inc.Lippincott Williams &Wilkins.Anesthesiology 2012;116:248–73•What other guideline statements are available on this topic?X These Practice Guidelines update the “Practice Guidelines for Acute Pain Management in the Perioperative Setting,”adopted by the ASA in 2003and published in 2004.*•Why was this guideline developed?X In October 2010,the Committee on Standards and Practice Parameters elected to collect new evidence to determine whether recommendations in the existing Practice Guide-line were supported by current evidence.•How does this statement differ from existing guidelines?X New evidence presented includes an updated evaluation of scientific literature and findings from surveys of experts and randomly selected ASA members.The new findings did not necessitate a change in recommendations.•Why does this statement differ from existing guidelines?X The ASA guidelines differ from the existing guidelines be-cause they provide new evidence obtained from recent sci-entific literature as well as findings from new surveys of expert consultants and randomly selected ASA members.Supplemental digital content is available for this article.Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are available in both the HTML and PDF versions of this article.Links to the digital files are provided in the HTML text of this article on the Journal’s Web site ().that are intended to reduce or eliminate postoperative pain before discharge.B.Purpose of the GuidelinesThe purpose of these Guidelines is to(1)facilitate the safety and effectiveness of acute pain management in the perioperative set-ting;(2)reduce the risk of adverse outcomes;(3)maintain the patient’s functional abilities,as well as physical and psychologic well-being;and(4)enhance the quality of life for patients with acute pain during the perioperative period.Adverse outcomes that may result from the undertreatment of perioperative pain include(but are not limited to)thromboembolic and pulmo-nary complications,additional time spent in an intensive care unit or hospital,hospital readmission for further pain manage-ment,needless suffering,impairment of health-related quality of life,and development of chronic pain.Adverse outcomes associated with the management of perioperative pain include (but are not limited to)respiratory depression,brain or other neurologic injury,sedation,circulatory depression,nausea, vomiting,pruritus,urinary retention,impairment of bowel function,and sleep disruption.Health-related quality of life includes(but is not limited to)physical,emotional,social,and spiritual well-being.C.FocusThese Guidelines focus on acute pain management in the perioperative setting for adult(including geriatric)and pedi-atric patients undergoing either inpatient or outpatient sur-gery.Modalities for perioperative pain management ad-dressed in these Guidelines require a higher level of professional expertise and organizational structure than“as needed”intramuscular or intravenous injections of opioid analgesics.These Guidelines are not intended as an exhaus-tive compendium of specific techniques.Patients with severe or concurrent medical illness such as sickle cell crisis,pancreatitis,or acute pain related to cancer or cancer treatment may also benefit from aggressive pain bor pain is another condition of interest to anes-thesiologists.However,the complex interactions of concur-rent medical therapies and physiologic alterations make it impractical to address pain management for these popula-tions within the context of this document.Although patients undergoing painful procedures may benefit from the appropriate use of anxiolytics and sedatives in combination with analgesics and local anesthetics when indicated,these Guidelines do not specifically address the use of anxiolysis or sedation during such procedures.D.ApplicationThese Guidelines are intended for use by anesthesiologists and individuals who deliver care under the supervision of anesthesiologists.The Guidelines may also serve as a resource for other physicians and healthcare professionals who man-age perioperative pain.In addition,these Guidelines may be used by policymakers to promote effective and patient-cen-tered care.Anesthesiologists bring an exceptional level of interest and expertise to the area of perioperative pain management. Anesthesiologists are uniquely qualified and positioned to provide leadership in integrating pain management within perioperative care.In this leadership role,anesthe-siologists improve quality of care by developing and di-recting institution-wide,interdisciplinary perioperative analgesia programs.E.Task Force Members and ConsultantsThe original Guidelines were developed by an ASA ap-pointed task force of11members,consisting of anesthesiol-ogists in private and academic practices from various geo-graphic areas of the United States,and two consulting methodologists from the ASA Committee on Standards and Practice Parameters.The Task Force updated the Guidelines by means of a seven-step process.First,they reached consensus on the cri-teria for evidence.Second,original published research stud-ies from peer-reviewed journals relevant to acute pain man-agement were reviewed and evaluated.Third,expert consultants were asked to:(1)participate in opinion surveys on the effectiveness of various acute pain management rec-ommendations and(2)review and comment on a draft of the updated Guidelines.Fourth,opinions about the updated Guideline recommendations were solicited from a sample of active members of the ASA.Fifth,opinion-based informa-tion obtained during an open forum for the original Guide-lines,held at a major national meeting,†was reexamined. Sixth,the consultants were surveyed to assess their opinions on the feasibility of implementing the updated Guidelines. Seventh,all available information was used to build consen-sus to finalize the updated Guidelines.A summary of recom-mendations may be found in appendix1.F.Availability and Strength of EvidencePreparation of these Guidelines followed a rigorous method-ological process.Evidence was obtained from two principal sources:scientific evidence and opinion-based evidence. Scientific EvidenceStudy findings from published scientific literature were ag-gregated and are reported in summary form by evidence cat-egory,as described below.All literature(e.g.,randomized controlled trials[RCTs],observational studies,case reports) relevant to each topic was considered when evaluating the findings.However,for reporting purposes in this document, only the highest level of evidence(i.e.,level1,2,or3within†International Anesthesia Research Society,68th Clinical and Scientific Congress,Orlando,Florida,March6,1994.SPECIAL ARTICLEScategory A,B,or C,as identified below)is included in the summary.Category A:Supportive LiteratureRandomized controlled trials report statistically significant (PϽ0.01)differences between clinical interventions for a specified clinical outcome.Level1:The literature contains multiple RCTs,and aggre-gated findings are supported by meta-analysis.‡Level2:The literature contains multiple RCTs,but the number of studies is insufficient to conduct aviable meta-analysis for the purpose of theseGuidelines.Level3:The literature contains a single randomized con-trolled trial.Category B:Suggestive LiteratureInformation from observational studies permits inference of beneficial or harmful relationships among clinical interven-tions and clinical outcomes.Level1:The literature contains observational comparisons(e.g.,cohort,case-control research designs)of clin-ical interventions or conditions and indicates statis-tically significant differences between clinical inter-ventions for a specified clinical outcome.Level2:The literature contains noncomparative observa-tional studies with associative(e.g.,relative risk,correlation)or descriptive statistics.Level3:The literature contains case reports.Category C:Equivocal LiteratureThe literature cannot determine whether there are beneficial or harmful relationships among clinical interventions and clinical outcomes.Level1:Meta-analysis did not find significant differences (PϾ0.01)among groups or conditions.Level2:The number of studies is insufficient to conduct meta-analysis,and(1)RCTs have not found signif-icant differences among groups or conditions or(2)RCTs report inconsistent findings.Level3:Observational studies report inconsistent findings or do not permit inference of beneficial or harmfulrelationships.Category D:Insufficient Evidence from LiteratureThe lack of scientific evidence in the literature is described by the following terms.Inadequate:The available literature cannot be used to assess relationships among clinical interventions and clinical outcomes.The literature either does not meet the criteria for content as defined in the“Focus”of the Guidelines or does not permit a clear interpretation of findings due to methodological concerns(e.g.,confounding in study de-sign or implementation).Silent:No identified studies address the specified rela-tionships among interventions and outcomes.Opinion-based EvidenceAll opinion-based evidence(e.g.,survey data,open-forum testimony,Internet-based comments,letters,editorials)rel-evant to each topic was considered in the development of these updated Guidelines.However,only the findings ob-tained from formal surveys are reported.Opinion surveys were developed for this update by the Task Force to address each clinical intervention identified in the document.Identical surveys were distributed to expert consultants and ASA members.Category A:Expert OpinionSurvey responses from Task Force-appointed expert consultants are reported in summary form in the text,with a complete listing of consultant survey responses reported in appendix2. Category B:Membership OpinionSurvey responses from active ASA members are reported in summary form in the text,with a complete listing of ASA member survey responses reported in appendix2.Opinion survey responses are recorded using a5-point scale and summarized based on median values.§Strongly Agree:Median score of5(At least50%of the responses are5)Agree:Median score of4(At least50%of the responses are 4or4and5)Equivocal:Median score of3(At least50%of the re-sponses are3,or no other response category or combination of similar categories contain at least50%of the responses) Disagree:Median score of2(At least50%of responses are 2or1and2)Strongly Disagree:Median score of1(At least50%of responses are1)Category C:Informal OpinionOpen-forum testimony from the previous update,Internet-based comments,letters,and editorials are all informally evaluated and discussed during the development of Guide-line recommendations.When warranted,the Task Force may add educational information or cautionary notes based on this information.‡All meta-analyses are conducted by the American Society of An-esthesiologists methodology group.Meta-analyses from other sourcesare reviewed but not included as evidence in this document.§When an equal number of categorically distinct responses areobtained,the median value is determined by calculating the arith-metic mean of the two middle values.Ties are calculated by apredetermined formula.Practice GuidelinesGuidelinesI.Institutional Policies and Procedures for Providing Perioperative Pain ManagementInstitutional policies and procedures include(but are not limited to)(1)education and training for healthcare provid-ers,(2)monitoring of patient outcomes,(3)documentation of monitoring activities,(4)monitoring of outcomes at an institutional level,(5)24-h availability of anesthesiologists providing perioperative pain management,and(6)use of a dedicated acute pain service.Observational studies report that education and training programs for healthcare providers are associated with de-creased pain levels,1–4decreased nausea and vomiting,2and improved patient satisfaction1(Category B2evidence),al-though the type of education and training provided varied across the studies.Published evidence is insufficient to eval-uate the impact of monitoring patient outcomes at either the individual patient or institutional level,and the24-h availability of anesthesiologists(Category D evidence).Observational studies assessing documentation activities suggest that pain outcomes are not fully documented in patient records(Category B2evi-dence).5–11Observational studies indicate that acute pain ser-vices are associated with reductions in perioperative pain(Cate-gory B2evidence),12–20although treatment components of the acute pain services varied across the studies.The consultants and ASA members strongly agree that anesthesiologists offering perioperative analgesia services should provide,in collaboration with other healthcare pro-fessionals as appropriate,ongoing education and training of hospital personnel regarding the effective and safe use of the available treatment options within the institution.The con-sultants and ASA members also strongly agree that anesthe-siologists and other healthcare providers should use stan-dardized,validated instruments to facilitate the regular evaluation and documentation of pain intensity,the effects of pain therapy,and side effects caused by the therapy.The ASA members agree and the consultants strongly agree that: (1)anesthesiologists responsible for perioperative analgesia should be available at all times to consult with ward nurses, surgeons,or other involved physicians,and should assist in evaluating patients who are experiencing problems with any aspect of perioperative pain relief;(2)anesthesiologists should provide analgesia services within the framework of an Acute Pain Service and participate in developing standard-ized institutional policies and procedures;and(3)an inte-grated approach to perioperative pain management(e.g.,or-dering,administering,and transitioning therapies, transferring responsibility for pain therapy,outcomes assess-ment,continuous quality improvement)should be used to minimize analgesic gaps.Recommendations for Institutional Policies and Proce-dures.Anesthesiologists offering perioperative analgesia ser-vices should provide,in collaboration with other healthcare professionals as appropriate,ongoing education and training to ensure that hospital personnel are knowledgeable and skilled with regard to the effective and safe use of the available treatment options within the cational con-tent should range from basic bedside pain assessment to so-phisticated pain management techniques(e.g.,epidural an-algesia,patient controlled analgesia,and various regional anesthesia techniques)and nonpharmacologic techniques (e.g.,relaxation,imagery,hypnotic methods).For optimal pain management,ongoing education and training are essen-tial for new personnel,to maintain skills,and whenever ther-apeutic approaches are modified.Anesthesiologists and other healthcare providers should use standardized,validated instruments to facilitate the reg-ular evaluation and documentation of pain intensity,the effects of pain therapy,and side effects caused by the therapy.Analgesic techniques involve risk for adverse effects that may require prompt medical evaluation.Anesthesiologists responsible for perioperative analgesia should be available at all times to consult with ward nurses,surgeons,or other in-volved physicians,and should assist in evaluating patients who are experiencing problems with any aspect of perioper-ative pain relief.Anesthesiologists providing perioperative analgesia ser-vices should do so within the framework of an Acute Pain Service and participate in developing standardized institu-tional policies and procedures.An integrated approach to perioperative pain management that minimizes analgesic gaps includes ordering,administering,and transitioning therapies,and transferring responsibility for perioperative pain therapy,as well as outcomes assessment and continuous quality improvement.II.Preoperative Evaluation of the Patient Preoperative patient evaluation and planning is integral to perioperative pain management.Proactive individualized planning is an anticipatory strategy for postoperative analge-sia that integrates pain management into the perioperative care of patients.Patient factors to consider in formulating a plan include type of surgery,expected severity of postopera-tive pain,underlying medical conditions(e.g.,presence of respiratory or cardiac disease,allergies),the risk–benefit ratio for the available techniques,and a patient’s preferences or previous experience with pain.Although the literature is insufficient regarding the effi-cacy of a preoperative directed pain history,a directed phys-ical examination,or consultations with other healthcare pro-viders(Category D evidence),the Task Force points out the obvious value of these activities.One observational study in a neonatal intensive care unit suggests that the implementa-tion of a pain management protocol may be associated with reduced analgesic use,shorter time to extubation,and shorter times to discharge(Category B2evidence).21The ASA members agree and the consultants strongly agree that a directed history,a directed physical examination,SPECIAL ARTICLESand a pain control plan should be included in the anesthetic preoperative evaluation.Recommendations for Preoperative Evaluation of the Pa-tient.A directed pain history,a directed physical examina-tion,and a pain control plan should be included in the an-esthetic preoperative evaluation.III.Preoperative Preparation of the Patient Preoperative patient preparation includes(1)adjustment or continuation of medications whose sudden cessation may provoke a withdrawal syndrome,(2)treatments to reduce preexisting pain and anxiety,(3)premedications before sur-gery as part of a multimodal analgesic pain management program,and(4)patient and family education,including behavioral pain control techniques.There is insufficient literature to evaluate the impact of preoperative adjustment or continuation of medications whose sudden cessation may provoke an abstinence syn-drome(Category D evidence).Similarly,there is insufficient literature to evaluate the efficacy of the preoperative initia-tion of treatment either to reduce preexisting pain or as part of a multimodal analgesic pain management program(Cat-egory D evidence).RCTs are equivocal regarding the impact of patient and family education on patient pain,analgesic use,anxiety,and time to discharge,although features of pa-tient and family education varied across the studies(Category C2evidence).22–35The consultants and ASA members strongly agree that patient preparation for perioperative pain management should include appropriate adjustments or continuation of medications to avert an abstinence syndrome,treatment of preexistent pain,or preoperative initiation of therapy for postoperative pain management.The ASA members agree and the consultants strongly agree that anesthesiol-ogists offering perioperative analgesia services should pro-vide,in collaboration with others as appropriate,patient and family education.The consultants and ASA members agree that perioperative patient education should include instruction in behavioral modalities for control of pain and anxiety.Recommendations for Preoperative Preparation of the Pa-tient.Patient preparation for perioperative pain manage-ment should include appropriate adjustments or continua-tion of medications to avert an abstinence syndrome, treatment of preexistent pain,or preoperative initiation of therapy for postoperative pain management.Anesthesiologists offering perioperative analgesia services should provide,in collaboration with others as appropriate, patient and family education regarding their important roles in achieving comfort,reporting pain,and in proper use of the recommended analgesic mon misconceptions that overestimate the risk of adverse effects and addiction should be dispelled.Patient education for optimal use of patient-controlled analgesia(PCA)and other sophisticated methods,such as patient-controlled epidural analgesia,might include discussion of these analgesic methods at the time of the preanesthetic evaluation,brochures and video-tapes to educate patients about therapeutic options,and dis-cussion at the bedside during postoperative visits.Such edu-cation may also include instruction in behavioral modalities for control of pain and anxiety.IV.Perioperative Techniques for Pain Management Perioperative techniques for postoperative pain management include but are not limited to the following single modalities: (1)central regional(i.e.,neuraxial)opioid analgesia;(2)PCA with systemic opioids;and(3)peripheral regional analgesic techniques,including but not limited to intercostal blocks, plexus blocks,and local anesthetic infiltration of incisions.Central regional opioid analgesia:Randomized con-trolled trials report improved pain relief when use of prein-cisional epidural or intrathecal morphine is compared with preincisional oral,intravenous,or intramuscular morphine (Category A2evidence).36–39RCTs comparing preoperative or preincisional intrathecal morphine or epidural sufenta-nil with saline placebo report inconsistent findings regard-ing pain relief(Category C2evidence).40–43RCTs compar-ing preoperative or preincisional epidural morphine or fentanyl with postoperative epidural morphine or fentanyl are equivocal regarding postoperative pain scores(Cate-gory C2evidence).44,45Meta-analyses of RCTs46–54report improved pain relief and increased frequency of pruritus in comparisons of postincisional epidural morphine and saline placebo(Cate-gory A1evidence);findings for the frequency of nausea or vomiting were equivocal(Category C1evidence).Meta-anal-yses of RCTs comparing postincisional epidural morphine with intramuscular morphine report improved pain relief and an increased frequency of pruritus(Category A1evi-dence).49,55–59One RCT reports improved pain scores and less analgesic use when postincisional intrathecal fentanyl is compared with no postincisional spinal treatment(Category A3evidence).60One RCT reports improved pain scores when postopera-tive epidural morphine is compared with postoperative epidural saline(Category A3evidence).61Meta-analyses of RCTs62–70re-port improved pain scores and a higher frequency of pruritus and urinary retention when postoperative epidural morphine is compared with intramuscular morphine(Category A3evi-dence);findings for nausea and vomiting are equivocal (Category C2evidence).Findings from RCTs are equivocal regarding the analgesic efficacy of postoperative epidural fentanyl compared with postoperative IV fentanyl(Cate-gory C2evidence)71–74;meta-analytic findings are equivo-cal for nausea and vomiting and pruritus(Category C1 evidence).72–76PCA with systemic opioids:Randomized controlled trials report equivocal findings regarding the analgesic efficacy of IV PCA techniques compared with nurse or staff-adminis-tered intravenous analgesia(Category C2evidence).77–80Practice GuidelinesMeta-analysis of RCTs reports improved pain scores when IV PCA morphine is compared with intramuscular mor-phine(Category A1evidence).81–90Findings from meta-anal-ysis of RCTs comparing epidural PCA and IV PCA opioids are equivocal regarding analgesic efficacy(Category C1evi-dence).89–93Findings from meta-analyses of RCTs94–103in-dicate more analgesic use when IV PCA with a background infusion of morphine is compared with IV PCA without a background infusion(Category A1evidence);findings were equivocal regarding pain relief,nausea and vomiting,pruri-tus,and sedation(Category C1evidence).Peripheral regional techniques:For these Guidelines,pe-ripheral regional techniques include peripheral nerve blocks (e.g.,intercostal,ilioinguinal,interpleural,or plexus blocks), intraarticular blocks,and infiltration of incisions.RCTs in-dicate that preincisional intercostal or interpleural bupiva-caine compared with saline is associated with improved pain relief(Category A2evidence).104,105RCTs report improved pain relief and reduced analgesic consumption when postin-cisional intercostal or interpleural bupivacaine is compared with saline(Category A2evidence).104–109Meta-analyses of RCTs report equivocal findings for pain relief and analgesic used when postoperative intercostal or interpleural blocks are compared with saline(Category C1evidence).110–117 Randomized controlled trials report equivocal pain relief findings when preincisional plexus blocks with bupivacaine are compared with saline(Category C2evidence).118–121 Meta-analyses of RCTs118–122report less analgesic use when preincisional plexus blocks with bupivacaine are compared with saline(Category A1evidence);findings are equivocal for nausea and vomiting(Category C1evidence).Meta-analysis of RCTs reports lower pain scores when preincisional plexus and other blocks are compared with no block(Category A1 evidence).123–127RCTs report equivocal findings for pain scores and analgesic use when postincisional plexus and other blocks are compared with saline or no block(Category C2 evidence).124,128–132RCTs report equivocal findings for pain scores and analgesic use when postincisional intraarticular opioids or local anesthetics are compared with saline(Cate-gory C2evidence).133–139Meta-analysis of RCTs reports improved pain scores when preincisional infiltration of bupivacaine is compared with saline (Category A1evidence)140–148;findings for analgesic use are equivocal(Category C1evidence).140,145,147,148–150Meta-anal-yses of RCTs are equivocal for pain scores and analgesic use when postincisional infiltration of bupivacaine is compared with saline(Category C1evidence).140,151–160Meta-analysis of RCTs reports equivocal pain score findings when preinci-sional infiltration of bupivacaine is compared with postinci-sional infiltration of bupivacaine(Category C1evi-dence).140,145,161–164Meta-analysis of RCTs reports improved pain scores and reduced analgesic use when prein-cisional infiltration of ropivacaine is compared with saline (Category A1evidence).164–171The consultants and ASA members strongly agree that anesthesiologists who manage perioperative pain should use therapeutic options such as epidural or intrathecal opioids, systemic opioid PCA,and regional techniques after thought-fully considering the risks and benefits for the individual patient;they also strongly agree that these modalities should be used in preference to intramuscular opioids ordered“as needed.”The consultants and ASA members also strongly agree that the therapy selected should reflect the individual anesthesi-ologist’s expertise,as well as the capacity for safe application of the modality in each practice setting.Moreover,the consultants and ASA members strongly agree that special caution should be taken when continuous infusion modalities are used,as drug accumulation may contribute to adverse events. Recommendations for Perioperative Techniques for Pain Management.Anesthesiologists who manage perioperative pain should use therapeutic options such as central regional (i.e.,neuraxial)opioids,systemic opioid PCA,and peripheral regional techniques after thoughtfully considering the risks and benefits for the individual patient.These modalities should be used in preference to intramuscular opioids or-dered“as needed.”The therapy selected should reflect the individual anesthesiologist’s expertise,as well as the capacity for safe application of the modality in each practice setting. This capacity includes the ability to recognize and treat ad-verse effects that emerge after initiation of therapy.Special caution should be taken when continuous infusion modali-ties are used,as drug accumulation may contribute to adverse events.V.Multimodal Techniques for Pain Management Multimodal techniques for pain management include the administration of two or more drugs that act by different mechanisms for providing analgesia.These drugs may be administered via the same route or by different routes.Multimodal techniques with central regional analgesics: Meta-analyses of RCTs46,49,172–176report improved pain scores(Category A1evidence)and equivocal findings for nau-sea and vomiting and pruritus(Category C1evidence)when epidural morphine combined with local anesthetics is com-pared with epidural morphine alone.Meta-analyses of RCTs177–188report improved pain scores and more motor weakness when epidural fentanyl combined with local anes-thetics is compared with epidural fentanyl alone(Category A1 evidence);equivocal findings are reported for nausea and vomiting and pruritus(Category C1evidence).Meta-analyses of RCTs49,172,176,189–194report improved pain scores, greater pain relief,and a higher frequency of pruritus(Category A1evidence)when epidural morphine combined with bupiva-caine is compared with epidural bupivacaine alone;equivocal findings are reported for nausea and vomiting(Category C1ev-idence).RCTs report equivocal findings when epidural fentanyl combined with bupivacaine is compared with epidural bupiva-caine alone(Category C2evidence).179–181,188Meta-analysis of RCTs for the above comparison reports higher frequency ofSPECIAL ARTICLES。