Selective attention in the acquisition of the past tense

心理学专业(英语)术语

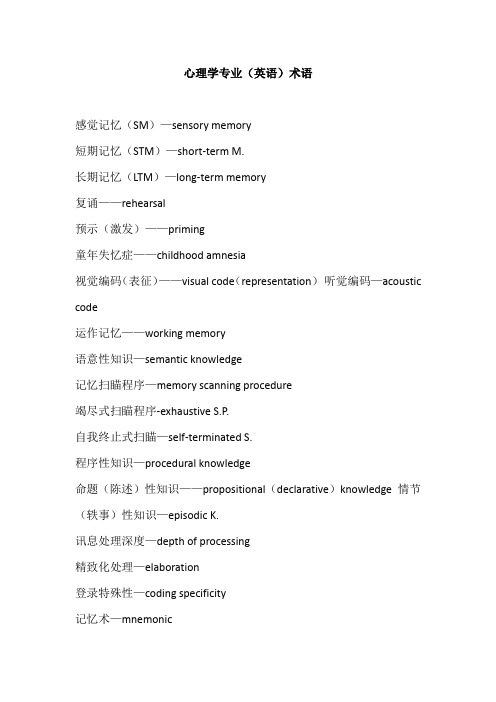

心理学专业(英语)术语感觉记忆(SM)—sensory memory短期记忆(STM)—short-term M.长期记忆(LTM)—long-term memory复诵——rehearsal预示(激发)——priming童年失忆症——childhood amnesia视觉编码(表征)——visual code(representation)听觉编码—acoustic code运作记忆——working memory语意性知识—semantic knowledge记忆扫瞄程序—memory scanning procedure竭尽式扫瞄程序-exhaustive S.P.自我终止式扫瞄—self-terminated S.程序性知识—procedural knowledge命题(陈述)性知识——propositional(declarative)knowledge 情节(轶事)性知识—episodic K.讯息处理深度—depth of processing精致化处理—elaboration登录特殊性—coding specificity记忆术—mnemonic位置记忆法—method of loci字钩法—peg word(线)探索(测)(激发)字—prime关键词——key word命题思考——propositional thought心像思考——imaginal thought行动思考——motoric thought概念——concept原型——prototype属性——property特征——feature范例策略——exemplar strategy语言相对性(假说)—linguistic relativity th.音素——phoneme词素——morpheme(字词的)外延与内涵意义—denotative & connotative meaning (句子的)表层与深层结构—surface & deep structure 语意分析法——semantic differential全句语言—holophrastic speech过度延伸——over-extension电报式语言—telegraphic speech关键期——critical period差异减缩法——difference reduction方法目的分析——means-ends analysis倒推——working backward动机——motive自由意志——free will决定论——determinism本能——instinct种属特有行为——species specific驱力——drive诱因——incentive驱力减低说——drive reduction th.恒定状态(作用)—homeostasis原级与次级动机—primary & secondary M.功能独立—functional autonomy下视丘侧部(LH)—lateral hypothalamus 脂肪细胞说——fat-cell theory.下视丘腹中部(VMH)—ventromedial H 定点论——set point th.CCK───胆囊调节激素第一性征——primary sex characteristic第二性征——secondary sex characteristic 自我效能期望—self-efficiency expectancy内在(发)动机—intrinsic motive外在(衍)动机—extrinsic motive成就需求——N. achievement需求层级—hierarchy of needs自我实现——self actualization冲突——conflict多项仪——polygraph肤电反应——GSR(认知)评估——(cognitive appraisal)脸部回馈假说——facial feedback hypothesis(生理)激发——arousal挫折-攻击假说——frustration-aggression hy.替代学习——vicarious learning发展——development先天——nature后天——nurture成熟——maturation(视觉)偏好法——preferential method习惯法——habituation视觉悬崖——visual cliff剥夺或丰富(环境)——deprivation or enrichment of env. 基模——schema同化——assimilation调适——accommodation平衡——equilibrium感觉动作期——sensorimotor stage物体永久性——objective permanence运思前期——preoperational st.保留概念——conservation道德现实主义——moral realism具体运思期——concrete operational 形式运思期——formal operational st. 前俗例道德——pre-conventional moral 俗例道德——conventional moral超俗例道德——post-conventional moral 气质——temperament依附——attachment性别认定——gender identity性别配合——sex typing性蕾期——phallic stage恋亲冲突—Oedipal conflict认同——identification社会学习——social learning情结——complex性别恒定——gender constancy青年期——adolescence青春期——-puberty第二性征——secondary sex characteristics 认同危机——identity crisis 定向统合——identity achievement 早闭型统合——foreclosure未定型统合——moratorium迷失型统合——identity diffusion传承——generativity心理动力——psycho-dynamics心理分析——psychoanalysis行为论——behaviorism心理生物观——psycho-biological perspective 认知——cognition临床心理学家-clinical psychologist谘商——counseling人因工程——human factor engineering组织——organization潜意识——unconsciousness完形心理学——Gestalt psychology感觉——sensation知觉——perception实验法——experimental method独变项——independent variable依变项——dependent V.控制变项——control V.生理——physiology条件化——conditioning学习——learning比较心理学——comparative psy.发展——development社会心理学——social psy.人格——personality心理计量学—psychometrics受试(者)——subject 实验者预期效应—experimenter expectancy effect 双盲法——double—blind实地实验——field experiment相关——correlation调查——survey访谈——interview个案研究——case study观察——observation心理测验——psychological test纹理递变度——texture gradient注意——attention物体的组群——grouping of object型态辨识—pattern recognition 形象-背景——figure-ground 接近律——proximity相似律——similarity闭合律——closure连续律——continuity对称律——symmetry错觉——illusion幻觉——delusion恒常性——constancy大小——size形状——shape位置——location单眼线索——monocular cue 线性透视——linear- perspective 双眼线索——binocular cue 深度——depth调节作用——accommodation 重迭——superposition双眼融合——binocular fusion 辐辏作用——convergence双眼像差——binocular disparity 向度——dimension自动效应——autokinetic effect 运动视差——motion parallax 诱发运动——induced motion闪光运动——stroboscopic motion 上下文﹑脉络-context人工智能——artificial intelligence A.I. 脉络关系作用-context effect 模板匹配——template matching整合分析法——analysis-by-synthesis丰富性——redundancy选择性——selective无yi识的推论-unconscious inferences运动后效——motion aftereffect特征侦测器—feature detector激发性——excitatory抑制性——inhibitory几何子——geons由上而下处理—up-down process由下而上处理——bottom-up process连结者模式——connectionist model联结失识症——associative agnosia脸孔辨识困难症——prosopagnosia意识——conscious(ness)意识改变状态——altered states of consciousness 无意识——unconsciousness前意识——preconsciousness内省法——introspection边缘注意——peripheral attention多重人格——multiple personality午餐排队(鸡尾酒会)效应—lunch line(cocktail party)自动化历程——automatic process解离——dissociate解离认同失常——dissociative identity disorder 快速眼动睡眠——REM dream非快速眼动睡眠—NREM dream神志清醒的梦——lucid dreaming失眠——insomnia显性与隐性梦——manifest & latern content心理活动性psychoactive effect冥想——meditation抗药性——tolerance戒断——withdrawal感觉剥夺——sensory deprivation 物质滥用——substance abuse 成瘾——physical addiction物质依赖——sub. dependence 戒断症状——withdrawal symptom 兴奋剂——stimulant幻觉(迷幻)剂——hallucinogen 镇定剂——sedative抑制剂——depressant酒精中毒引起谵妄—delirium tremens 麻醉剂——narcotic催眠——hypnosis催眠后暗示——posthypnotic suggestion 催眠后失忆posthypnotic amnesia 超心理学——parapsychology超感知觉extrasensory perception ESP 心电感应——telepathy超感视——clairvoyance预知——precognition心理动力—psycokinesis PK受纳器——receptor绝对阈——absolute threshold 差异阈——difference threshold 恰辨差——-JND韦伯律——Weber''s law心理物理——psychophysical费雪纳定律——Fechner''s law 频率——frequency振幅——amplitude音频——pitch基音——fundamental tone 倍音——overtone和谐音——harmonic音色——timbre白色噪音——white noise鼓膜——eardrum耳蜗——cochlea卵形窗—oval window圆形窗——round window前庭——vestibular sacs半规管——semicircular canal 角膜——cornea水晶体——lens虹膜——iris瞳孔——pupil网膜——retina睫状肌——ciliary muscle调节作用——accommodation 脊髓——spinal cord反射弧——reflex arc脑干——brain stem计算机轴性线断层扫描——CAT或CT PET——正子放射断层摄影MRI——磁共振显影延脑——medulla桥脑——pons小脑——cerebellum网状结构——reticular formation RAS——网状活化系统视丘——thalamus下视丘——hypothalamus大脑——cerebrum脑(下)垂体(腺)—pituitary gland 脑半球——cerebral hemisphere 皮质——cortex胼胝体——corpus callosum边缘系统——limbic system海马体——hippocampus杏仁核——amygdala中央沟——central fissure侧沟——lateral fissure脑叶——lobe同卵双生子——identical twins异卵双生子—fraternal twins古典制约——classical conditioning 操作制约——operant conditioning 非制约刺激—(US unconditioned stimulus 非制约反应—(UR)unconditioned R. 制约刺激——(CS)conditioned S. 制约反应——(CR)conditioned R. 习(获)得——acquisition增强作用——reinforcementxiao除(弱)——extinction自(发性)然恢复——spontaneous recovery 前行制约—forward conditioning同时制约——simultaneous conditioning 回溯制约——backward cond.痕迹制约——trace conditioning延宕制约—delay conditioning类化(梯度)——generalization(gradient)区辨——discrimination(次级)增强物——(secondary)reinforcer嫌恶刺激——aversive stimulus试误学习——trial and error learning效果率——law of effect正(负)性增强物—positive(negative)rei.行为塑造—behavior shaping循序渐进——successive approximation自行塑造—autoshaping部分(连续)增强—partial(continuous)R定比(时)时制—fixed ratio(interval)schedule FR或FI变化比率(时距)时制—variable ratio(interval)schedule VR或VI 逃离反应——escape R.回避反应—avoidance response习得无助——learned helplessness顿悟——insight学习心向—learning set隐内(潜在)学习——latent learning认知地图——cognitive map生理回馈——biofeedback敏感递减法-systematic desensitization普里迈克原则—Premack''s principle洪水法——flooding观察学习——observational learning动物行为学——ethology敏感化—sensitization习惯化——habituation联结——association认知学习——cognitional L.观察学习——observational L.登录﹑编码——encoding保留﹑储存——retention提取——retrieval回忆——(free recall全现心像﹑照相式记忆——eidetic imagery﹑photographic memory .舌尖现象(TOT)—tip of tongue再认——recognition再学习——relearning节省分数——savings外显与内隐记忆——explicit & implicit memory记忆广度——memory span组集——chunk序列位置效应——serial position effect起始效应——primacy effect新近效应——recency effect心(情)境依赖学习——state-dependent L.无意义音节—nonsense syllable顺向干扰——proactive interference逆向干扰——retroactive interference闪光灯记忆——flashbulb memory动机性遗忘——motivated forgetting器质性失忆症—organic amnesia阿兹海默症——Alzheimer''s disease近事(顺向)失忆症—anterograde amnesia 旧事(逆向)失忆—retrograde A.高沙可夫症候群—korsakoff''s syndrome凝固理论—consolidation。

《英语语言学导论》(第四版Chapter11 Second Language Acquisition

11.2.2 Learner’s factors

• Learner’s factors mainly cover the following aspects:

• Motivation • Language aptitude • Age • Learning strategy

11.2.1 Social factors

Discussing Task

Group work: Have a discussion on the following questions.

1. How does (second) language acquisition take place?

2. How is foreign language learning different from second language acquisition?

The Symbolic Function of Words

Teaching Aims

1. To know what SLA is, and how the theories account for SLA. 2. To understand different factors affecting SLA 3. To know how learner’s language is analyzed 4. To cultivate students’ research awareness and innovative spirit in discovering and solving problems by analyzing the different kinds of errors and individual differeneces in SLA.

语言学导论术语汉译..

A-bar movement(A-棒儿移位)306 Ablaut(元音交替)164Abney, S.(人名,阿伯尼)360accent (see phrasal stress)(重读)accusative case (宾格)248, 251, 265–6, 356, 360–1accusative possessors in Child English(儿童英语中宾格性领属者)359–61accusative subjects(儿童英语中宾格性主语)in Child English355–8in infinitive clauses(非定式小句)251 acquired language disorders(获得性语言错乱)13, 213acquisition of language(语言的获得)(see also developmental linguistics(发展语言学)) 408acrolect(上层方言)234activation in psycholinguistics(心理语言学中的激活作用)202, 209active articulator(主动性发音器官)31 active voice(主动语态)137additions in speech errors(言语失误中的追加)115Adger, D. (人名,阿杰尔)267 adjacency pairs(邻接对)401adjectives(形容词)130comparative form of ((形容词)的比较级形式)130and derivational morphology((形容词)和派生形态学)144dimensional(程度(形容词))175–6, 177, 179incorporation((形容词)并入)161in language acquisition((语言习中的)形容词)187superlative form of (形容词的最高级)130adjuncts(附加语)249, 331adverbs(副词)130, 144Affected Object(蒙受性宾语)334–5affix(词缀)140Affix Attachment(词缀附接)273, 319 affricates(塞擦音)29African American V ernacular English (AA VE)(非裔美国人英语方言土语)agreement in(AA VE的一致关系)233, 237double negation in(AA VE的双重否定)297empty T in(AA VE中的空语类T)271–2 inversion in(AA VE中的倒装)311–13 possessives in(AA VE中的所有格或属格)237age and variation in language use(年龄与语言运用中的变异)235–6age-graded sociolinguistic variables(与年龄段相关的社会语言学变量)16Agent(施事)305, 333, 334–5 agglutinating languages(黏着语)156–7 agrammatism(语法缺失)(see also Broca’s aphasia(布洛卡失语症)) 214–17,377–82, 385, 408comprehension errors in(语法缺失中的理解错误)215, 216–17, 378–80production errors in(语法缺失中的发音错误)215–16, 378agreement (一致关系)135, 137, 144–5, 233, 248in AA VE(AA VE中的一致关系)233, 237 in complement clauses(补语小句中的一致关系)251in East Anglian English(东央格鲁英语中的一致关系)233in EME(EME中的一致关系)320 operations in syntax(句法中一致关系演算或操作)264–5, 267–8, 306, 345, 407in SLI(SLI中的一致关系)219, 385in south western English (东南部英语中的一致关系)233allomorphs(语素变体)152allomorphy(语素音位变化)151–2 lexically conditioned(词汇制约的语素音位变化)152phonologically conditioned(音系制约的语素音位变化)152, 220plural(复数的语素音位变化)188–9 third person singular present(第三人称单数现在时的语素音位变化)220allophones(音位变体)77allophonic variation(音位的变化)77 allophony(音位变化)77alternation in phonology(音系(学)中的交替)26, 83–5, 90, 152alveolars(齿龈音)30, 109 alveopalatals(齿龈硬腭音)(see palato-alveolars)ambiguity(歧义)(see also structural ambiguity(结构歧义)) 5, 232 amelioration in semantic change(语义变化中的改进现象)231American English(美国英语)55, 63, 71, 227 A-movement(论元移位)306Ancient Egyptian(古埃及人)119 Antecedent(先行语)277local for reflexives(约束反身代词的局部先行语)277–8anterior as phonological feature(作为音系特征的前部性)86, 413anticipations in speech errors(言语错失中的先兆)115, 117antonyms(反义词)176, 208, 209 antonymy(反义关系,反义现象)176, 177–8 aphasia(失语症)11–13, 213–19 selective impairment in(失语症中的缺陷或障碍选择性)213apophony (元音交替,元音弱化)(see ablaut) apparent-time method(视时方法后手段)16, 66approximant as phonological feature(无擦通音作为音系特征)412approximants(无擦通音)33in child phonology(儿童音系中的无擦通音)100–4Arabic (阿拉伯语)81, 224 arbitrariness of the linguistic sign(语言符号的任意性)205argument movement(论元移位)(see A-movement)arguments(论元)130, 247Armenian alphabet(亚美尼亚字母或文字)119Articles(冠词)( see also determiners(限定语)) 130, 133Ash, S. (人名,阿施)237aspect (体)252perfect(完成(体))252, 261 progressive(进行(体))252aspirated as phonological feature(送气作为音系特征)87, 413aspiration(送气音)35, 75–7, 87–90, 90–1 assimilation(同化现象)(see also harmony (和谐发音)) 5in Farsi(Farsi中的同化现象)49 partial(部分同化)100target of (同化对象)100total(整体同化)100trigger for(同化的触发者)100 audience design((面向受众的设计))53–4, 409Austin, J. L. (人名,奥斯汀)394 Australian English(澳大利亚英语)62, 64, 71, 227auxiliary copying in children(儿童语言中的助动词拷贝)295auxiliary inversion(助动词倒装)294–6 auxiliary verbs(助动词)133difficulties with in SLI(特定语言障碍中助动词使用上的困难)219, 385dummy(假性助动词)319errors in SLI (SLI中助动词的错失)385 as finite T(助动词作为定式的T)259, 261and gapping(助动词和空位)272 perfect (完成体)136progressive(进行体)136babbling(婴儿发出的咿哑声)96back as phonological feature(后部(音)作为音系特征)413backtracking in parsing(切分中的回溯法)373back vowels(后元音)36, 109–10Bailey(贝利), B. 313Bantu(班图语)156bare nominals(光杆名词性成分)284–5 in Child English(儿童英语中的光杆名词型成分)358–9base form of verbs(动词的基础形式/基式)147basic level of categorisation((范畴化的基本层级)194–6, 226, 232in Wernicke’s aphasia(维尼克失语症中范畴化的基本层级)217–18basilect(下层方言)235behaviourism(行为主义)115Belfast(贝尔法斯特)51Belfast English(贝尔法斯特英语)300Bell(贝尔), A. 53Bengali(孟加拉人(的),孟加拉语(的))71–2, 87Berko(拨库), J. 189Bidialectalism(双方言现象)409 Bilabials(双唇音)30Bilingualism(双语现象)409Binarity(二分性)of parametric values(参数值的二分性)314, 317, 320, 321, 325,349, 351of phonological features(音系特征的二分性)85blends(融合)207–8, 209in paragrammatism(语法倒错性言语障碍中融合现象)382Bloom(布龙姆), L. 355body of tongue (舌面)(see dorsum) borrowing(借用)224–5bound morphemes(粘着语素)140in aphasia (失语症者话语中的)216in SLI(特定语言损伤中的)219–21 bound variable interpretation of pronouns(约束代词阐释的变量)342–4bound word(粘着词)150Bradford(布莱德福德)47–8Braine, M.(人名)351Bresnan, J. (人名)246British English ( 英国英语see also Contemporary Standard English) 62 , 69 –70, 71,227–8, 230broad transcription(宽式标音)76 Broca, P. (人名)12Broca’s aphasia (布洛卡失语症see also agrammatism) 214– 17, 377–82 Broca’s area (布洛卡区)12Brown, R. (人名)189Bucholtz, M. (人名)51Bulgarian (保加利亚语)85calque(仿造,语义转借)225 Cambodian (柬埔寨语)38Canadian English (加拿大英语)227–8 Cantonese (广东话,粤语)79, 81Cardiff (加迪夫,地名)53Caribbean English(加勒比式英语)66 case (格see also genitive case(属格), nominative case(主格),objective case(宾格)) 248assignment of(格指派)264, 265–6, 267–8, 345, 356–8,360–1errors in agrammatism (语法缺失中的格错误)216errors in SLI(特定语言损伤中的格错误)385(拉丁语中的格)in Latin 158marking in Child English(儿童英语中的格标记)355–8structural(结构格)356in Turkish(土耳其语中格)158 categorical perception(范畴感知)113 causative verb(致使动词)274–5Celtic languages(凯饵特语族语言)164 central vowels(央元音)36centre-embedding(中心内嵌现象)370, 373–4cerebral cortex(大脑皮层)11cerebral hemispheres(大脑半球)11, 214 chain shift(链移)66–7Chambers, J. (人名)227child grammar(儿童语法)349–61child phonology(儿童音系)96–106 Cherokee(切罗基语)119Chicago(芝加哥)66Chinese (汉语)43, 119, 156, 224 Chomsky, N. (人名,乔姆斯基)1, 2, 7, 11, 213, 245–6, 314, 325, 377, 407Chukchee(楚克其人[语])160–1 circumfix (框架式词缀see confix)citation form(引用形式,基础形式,原形)134clauses(小句)247bare infinitive(光杆不定试小句)275–6 complement (小句补语)250–2, 275, 276 as CPs (充任CPs的小句)279, 280, 282, 283, 293, 304, 349, 356, 361declarative(陈述小句)279, 280finite in German SLI(德语SLI小句中的限定性)385finite verb in (小句中的限定动词)251, 265–6force of(小句的语力)279function of(小句的功能)253in German(德语中的小句)321–4 infinitive(不定式小句)275, 276–8 interrogative (疑问小句)279main(主要小句,主句)250, 280–1 non-finite verb in(小句中的非定式动词)251, 281–2v. phrases(小句和短语)261–2relative(关系小句)253, 367in sentence perception(句子感知过程中的小句)367, 368tensed (v. untensed)(时态小句和非时态小句)251as TPs(小句作为TPs)273, 274, 275–6, 278click studies(点击调查)367–8 cliticisation(附着化)274–6and copies(附着化和拷贝)296, 298–9 clitics(附着成分)150–1in Spanish(西班牙语中的附着成分)151 cluster (see consonant cluster) 音丛(参见辅音丛)codas of syllables(音节的节尾(音))79–82 in child language(儿童语言中的节尾音)104–5cognitive effects of utterances(话语的认知效应)399cognitive synonymy(认知同义关系或现象)174–5cognitive system(认知系统)language as(语言作为认知系统)1–14, 409 coherence in discourse(语篇中的连贯)397 co-hyponyms(共存性下义词/下位词)172, 209in Wernicke’s aphasia(维尼克失语症中的共存性下义词)218co-indexing(同指标/同标引)341 Comanche(科曼奇族/语)225co-meronyms(共存性局部关系词)174, 208 comment (v. topic)(话题和评述/述题)249, 281Communicative Princ iple of Relevance(交际的关联原则)399–400communities of practice(实践社群)52 commutation test(接换测试)390 competence (v. performance)((语言能力)和语言行为/运用)2–3, 9, 264, 339, 367, 370, 375, 388, 408, 409complement(补语)130, 247–9, 262 covert(隐性补语)278interrogative expressions as(疑问表达式充任补语)297complementaries(互补性反义词)176 complementarity(互补性/关系)176, 177–8 complementary distribution(互补分布)76 complement clause(补语小句)250–2in German(德语中的补语小句)322 complement clause question(疑问型补语小句)299–300complement clause yes-no question(是非型疑问补语小句)303complementiser(标句词)135 declarative(陈述句的标句词)279 empty(空标句词)278–83, 284, 299 interrogative(疑问型标句词)279 complex sentence(复合句)250–3 compounds(复合词)148–50, 379, 408in language acquisition (语言习得中的复合词)191–2structural ambiguity in(复合词中的结构歧义)149synthetic(合成性复合词)162 comprehension of language (see sentence comprehension, speech perception)(语言理解(参见句子理解、言语感知))concatenative morphology(并置形态学)163 concept (v. lexical entry)(概念(和词条))205–6, 209, 225, 233confix(框架词缀/环缀)162 conjugation (接合)159consonants(辅音)28–35categorical perception of (辅音的类别感知)113syllabic(成音节性辅音)41three-term description of(辅音的三个方面的描写)34, 61in writing systems (书写系统中的辅音)119consonant change (辅音变化)61–4 consonant cluster (辅音丛)41deletion in(辅音丛中的删除现象)54–6 simplification in child language(儿童语言中的辅音丛简化现象)98consonant harmony(辅音和谐/辅音的协同发音)99consonant insertion(辅音插入)64 consonant loss(辅音丢失)63 consonant mutation(辅音变换)164–5 consonantal as phonological feature(作为音系特征的辅音性)412constituency tests(成分性测试)263–4 constituents(结构成分)249, 263–4 covert (see empty constituents)(隐性成分(参见空成分))in sentence comprehension(句子了解中的隐性成分)366constraints(限制(条件))in phonology (音系中的限制条件)90–1 in syntax (句法中的限制条件)263, 312–13, 318Contemporary Standard English (CSE) (当代标准英语)311questions in(CSE中的疑问句)311, 313, 316strong C in(CSE中的强C)314weak T in (CSE中的弱T)317, 319 content words (内容词、实词)132in aphasias (失语症中的内容词或实词)214–15 continuous perception of vowels(元音的连续性感知)110–11contour tone(轮廓调或曲折型声调)43 contrastive sounds(对立音)77control(控制)276clause(控制小句)277, 282–3verbs (控制动词)277conversation(会话)245, 388logic of(会话的逻辑)395–7 Conversational Analysis (CA)(会话分析)246, 401–2conversational implicature(会话涵义)397 conversational maxims(会话准则)396–7, 399, 409conversational particles(会话中的小品词)400conversion((词性)转换)143Co-operative Principle(合作原则)396co-ordinating conjunction(并列连词)134 co-ordination test(并列关系测试)263–4, 279–80, 283, 333copy (trace) of movement(移位拷贝(语迹))295, 298–9, 340in Child English(儿童英语中的移位拷贝)295in sentence perception(句子感知中的移位拷贝)368–70as variable(移位拷贝作为变量)341co-referential interpretation of pronouns(代词的同指阐释)342, 343coronal(前舌音/舌冠音)34count noun(可数名词)285Coupland, N. (人名)53covert movement (隐性移位)339, 343–5 covert question operator(隐性疑问算子)302–3, 324Crossover Principle(跨越原则)343–4C Strength Parameter(C强度参数)314 cumulation(堆积现象)158Cutler, A.(人名)207Czech(捷克(语))81data of linguistics(语言学语料/数据)1–2, 117, 170declarative(陈述句/式)253–4, 394–5 declension(形态变化,尤其指格变化)158–9, 160default cases in phonology(音系(学)中的缺省情况)90definitions(定义)179–81, 193deictic words(指示性词语)389, 398 delinking in child phonology(儿童音系中的链接解除现象)103demonstratives(指示语)133dentals(牙齿,齿音)31, 109 derivational morphology(派生形态学)131, 143, 144in compounds(复合词中的派生形态)150 in language acquisition(语言习得中的派生形态)190–2Derivational Theory of Complexity (DTC)(复杂性推导理论)367Derivations(派生(式),推导(式))in phonology(音系学中的推导(式))85 in syntax(句法中的推导(式))306 despecification in child phonology(儿童音系中的描写(式))103determiner phrase (DP)(限定词短语/词组)262, 283–7in Child English(儿童英语中的限定词词组)286determiners (see also articles) (限定词(参见冠词))133, 297empty(空限定词)283–7null in Child English (儿童英语中的空限定词)358as operators(限定词作为算子)297 prenominal(名词前的限定词)286–7 pronominal(代词性限定词)286–7 quantifying(量化限定词)284–5, 303in SLI (SLI中的限定词)219Detroit (底特律)52, 66developmental linguistics(发展论语言学)1, 6–9DhoLuo(卢奥语,东苏丹语族,尼罗语支)164diachronic method in historical linguistics(历史语言学中的历时方法)15–16 diacritic (附加符号)35dialect contact(方言接触)227dialects(方言)regional (地域方言)14rhotic(翘舌音方言)77rural (乡村方言)228social(社会方言)14urban(城市方言)228dictionaries(词典、辞书)179–81 diphthongisation in language change(语言变化中的双元音化)64diphthongs(双元音)38–9discourse markers(话语标记)15 discourses(话语)245discrimination experiment(辨别力实验)111 distinctive features(区别性特征)85, 412, 414in child phonology(儿童音系中的区别性特征)101distribution(分布)76dorsals(舌面音)34dorsum(舌背、舌面)31Do-support(Do支撑)274D-projections(D投射)287, 349drag chain(拉链)67dual-lexicon model of child phonology(音系学中的双词库模型)104–5Dutch(荷兰语)231Early Modern English (EME)(早期现代英语,初期现代英语)negation in(EME中的否定)314–20 null subjects in (EME中的空主语)319–20, 351, 352questions in(EME中的疑问句)316 strong T in(EME中的强T)317East Anglian English(东盎格鲁英语)63, 64–5echo question(回声问)297, 299 Eckert, P. (人名)51–2Economy Principle(经济原则)301–2, 314, 318–19, 324‘edge’ as target of movement (边缘位置作为移位的目的地)306education level and language use(教育水平和语言运用/使用)49Egyptian cuneiform(古埃及楔形文字)119 Eimas, P.(人名)96elision (省缺)4ellipsis(省略)278, 371Elsewhere Condition(另处原则)89–90 empty constituents (空成分)246, 271–86, 407, 408in psycholinguistics(心理语言学中的空成分)271in sentence perception(句子感知中的空成分)368–70enclitic(后附着)151entailment(衍推/蕴含)170–1, 392–3 environment (context) in phonological rules (音系规则中的环境(语境))87errors in speech (言语中的偏误/失误,口误)114–17, 199, 207–9Estonian(爱沙尼亚语)38ethnic group and language use(族群和语言运用/使用)49–50exchanges in speech errors (see also word exchanges) (言语失误中的换位现象(参见词的换位))11 4 –16, 11 7exclamative(感叹句,感叹式)254 exponent(体现)145, 152–3, 252, 259, 261 extended exponence(扩展了的体现)159 extraction site(提取部位)298Farsi (Persian) (波斯语(波斯语的))49 Fasold, R.(人名)272feature matrix (特征矩阵)86features(特征)distinctive in phonology(音系学中的区别性特征)86–90, 177functional in agrammatism(语法缺失中的功能性特征)380–2morphological(形态特征)153, 163 semantic(语义特征)176–9semantic in acquisition(习得中的语义特征)193filler-gap dependencies(填充词-空位依存性/关系)369–70finite (v. non-finite) verb forms(定式(非-定式)动词形式)251–3 finiteness in language acquisition (语言习得中的有定性)359–61Finnish (芬兰语)99, 156flap (闪音)34flapping(闪音化)61floating features(漂移特征)101–4, 106 flouting of conversational maxims(对会话准则的藐视)397, 399focus(焦点)282, 389–92position(位置)282focus bar(焦点棒儿)88Fodor, J. (人名)201form (v. lemma)(形式(和内容))in lexical entries(词条中的形式和内容)128, 205–7free morphemes (自由语素)140Frege, G. (人名)338, 339, 344French (法语)90–1, 215, 224, 225, 230 frequency effect(频率效应)in paraphasias(言语错乱中的频率效应)217, 218in substitution errors(替换语误中的频率效应)208fricatives(擦音)29, 31–3Frisian(弗里斯兰语)231Fromkin, V. (人名)207front vowels (前(部)元音)36, 109–10 functional categories(功能语类)132–5, 247, 385in aphasia(失语症中的功能语类)214–17, 378–82comprehension of in agrammatism (语法缺失中功能语类的理解)378–80in language acquisition(语言习得中的功能语类)187–8and pragmatic presupposition(功能语类和语用预设)393production of in agrammatism(语法缺失中功能语类的产生)378in SLI (SLI中的功能语类)219–21 function words(功能词)132gapping(功能词缺项)272garden-path sentences(花园幽径句)10, 370, 374, 408gender(性范畴)errors in agrammatism(语法缺失中的性范畴错误)380, 381–2errors in SLI(SLI中的性范畴错误)385 in Old English(古英语中的性范畴)233 gender and language use (性范畴和语言的使用/运用)49, 234generative grammar(生成语法)4, 245 generative phonology(生成音系学)97–8 generic interpretation(通指阐释)of determiners(限定词的通指阐释)284 genetic endowment and language(遗传本能与语言)7, 13–14, 188, 311and language disorders(遗传本能与语言错乱)213genitive case(领属格)248, 265, 267, 356, 360–1and possessors in Child English(儿童英语中的领属格和领有者)359–61Georgian alphabet(乔治亚字母表)119 German(德语)81, 162, 164, 206, 231, 321–4 clause structure in(德语中的小句结构)321–4movement in (德语中移位)322–3 operator questions in (德语中的算子疑问句)323–4SLI in(德语中的SLI)383–5strong C in finite clauses in(德语中的强C)323strong T in finite clauses in(德语中的强T)323yes-no questions in(德语中的是非问句)324Germanic (日耳曼语)164, 224, 231 Glides(滑音)33global aphasia(全局性失语症)11glottal fricative(声门擦音)33, 47 glottalisation(声门化)82glottal plosive (glottal stop) (声门爆破音(声门塞音))34Goal(目标/终点)334Gordon, P. (人名)192grammar of a language(一种语言的语法)2–6, 81, 83, 120, 238, 306, 345, 350, 407 grammatical categories(语法语类)247in acquisition(习得中的语法语类)186–8 in sentence comprehension(句子理解中的语法语类)200grammatical functions(语法功能)247–50, 262grammatical (morphosyntactic) word(语法(形态-句法)词)146, 159Greek (希腊语)160, 225Greek alphabet(希腊字母表)119 Grice, P. (人名)396–7, 398, 402 Grimshaw, J. (人名)302Grodzinsky, Y. (人名)380–2gutturals(侯音,腭音)78Halliday, M.(人名)97hard palate(硬腭)31harmony(和谐)consonant (辅音和谐)99lateral(边音和谐)101–4velar(软腭音和谐)99, 101vowel(元音和谐)99–100Hawaiian(夏威夷语)81Head(核心成分)of compounds(复合词的核心)148of phrases(短语或词组的核心)257–61 head-driven phrase structure grammar(核心驱动短语结构语法)246head first word order(核心在首的词序)321, 350head last word order(核心在尾的词序)321 head movement(核心移位)293–6, 298, 306 Head Movement Constraint (HMC)(核心移位限制)318, 324Head Position Parameter(核心位置参数)321, 349, 350–1, 361Head Strength Parameter(核心强度参数)314Hebrew(希伯莱语)215, 380, 381 Henry, A. (人名)300high as phonological feature(高舌位作为音系特征)413high vowels(高元音)36, 109–10 historical linguistics(历史语言学)15–16 Hoekstra, T. (人名)373Holmes, J. (人名)49host for clitic(附着形式的宿主)151 Hungarian(西班牙语)38, 99, 156, 224, 267, 360Hyams, N. (人名)351–2, 359–61 Hyponyms(下位词)172in Wernicke’s aphasia(维尼克失语症中的下位词)218hyponymy(上下位关系)170–3, 177, 178, 194Icelandic(冰岛语)230Idealisation(理想化)409identification experiment(鉴别/识别实验)110–11, 112identification of null subject(空主语的识别)320, 352identity of meaning (see synonymy)(意义的同一性(参见同义关系))imaging techniques (成像技术)13 imperative (祈使句/式)254, 394–5 implicational scale(含义等级)55–6 implicit (understood) subject(隐性(理解出来的)主语)277, 351incomplete phrase(未完成短语/词组)261–2 incorporation(并入)160–1 independence of language faculty(语言能力的独立性)11, 377indirect speech acts(间接言语行为)394–5 inferences in conversation(会话中的推理)400infinite nature of language(语言的无限性)3–4, 260infinitive(不定式)134infinitive particle(不定式小品词)259–60 as non-finite T(不定式作为非有定的T)259 infinitive phrase (不定式短语/词组)259 infix(中缀)163INFL as grammatical category(屈折语素作为语法的语类)261inflection (屈折)143in English(英语中的屈折)137in grammar(语法中的屈折)136 inflectional categories(屈折语类)136as deictic(屈折语类终于哦为指示语)389 inflectional errors(屈折错误)in agrammatism (语法缺失中的屈折错误)378in SLI(SLI中的屈折错误)219–21, 385 inflectional formative(屈折的构成)145 inflectional languages(屈折语)156, 158–9, 160inflectional morphology(屈折形态学)143, 144–8in compounds (复合词中的屈折形态学)150in language acquisition(语言习得中的曲折形态学)187, 188–92inflectional paradigms in aphasia(失语症中的屈折变化表)216inflectional properties(屈折特征)137 inflectional rules (see morphological processes)(屈折规则)(参见形态过程)inflectional systems (屈折系统)156 informational encapsulation(信息封装)201 ‘information’ i n categories(语类中的信息)195–6information structure(信息结构)390–1 innateness hypothesis(内在性假说)7, 11, 213, 349–50, 361, 408input representations in child phonology (儿童音系中的输入表达式)103–6 Instrument(工具/用事)333interaction and variation(互动和变异)54 interdentals (齿间音)31interrogative(疑问(句))253–4, 394–5 interrogative complement(疑问性补语)299–300, 303interrogative interpretation(疑问句阐释)300–2, 341interrogative operator(疑问算子)302–3 intonation(语调)43–4intonational change (语调变化)71–2Inuit(因纽特语)119inversion(倒置、倒装)in questions(疑问句中的倒置现象)294–6, 300, 316, 322in varieties of English(英语变异中的倒置)311–14IPA (International Phonetic Association)(国际语音学会)27–44, 411Irish Gaelic (爱尔兰盖尔语)225Irony(反语)397Iroquoian(伊洛魁语的)161isolating languages(孤立语)156, 157 Italian(意大利语)214, 224, 230, 380 aphasic speech in(意大利语中的失语症者的言语)215, 380, 381–2Jamaican V ernacular English (JVE)(牙买加英语土语)313–14weak C in(牙买加英语土语中的弱C)314Japanese(日语)38, 78, 81, 160topic marking in(日语中的话题)391–2 Jones, D. (人名)27labelled bracketing(带标签的加方括弧法)141, 258labelled tree diagram(带标签的树形图)141–2, 258labials(唇音)34labiodentals(唇齿音)31Labov, W. (人名)16, 56, 57–8, 66–7, 68, 70 language contact(语言接触)227 language change(语言变化)15–16, 56–8, 61–72language disorders(语言错乱)11–14, 408 Language Faculty(语言官能)7–9, 280, 349–50language games(语言游戏)117 language shift(语言变换)15language use(语言运用)and the structure of society(语言运用与社会结构)14–16language variation(语言变异)15 laryngeal fricative (see glottal fricative)(喉擦音(参见声门擦音))larynx(喉)28Lashley, K.(人名)116–17lateral as phonological feature(边音作为音系特征)413lateral harmony(边音和谐)101–4 laterals(边音)33in child phonology(儿童音系中的边音)100–4Latin(拉丁语)157–60, 165, 224, 225, 391 Latin alphabet (拉丁语字母(表))119lax vowels(松元音)38, 77lemma(词条的内容)205–7retrieval of(词条内容的恢复)207–9 lesions of the brain(大脑的损伤)11 levels of linguistic analysis(语言分析的层次/级)76–7, 78, 106, 120Levelt, P.(人名)205level tones(直线调,水平调)43lexeme (词位)143–4, 145, 146, 205 lexical attrition(词汇磨损)228lexical categories(词汇语类)129–32, 247 lexical diffusion(词汇扩散)68–70lexical entry(词条)4, 78, 128, 129, 131, 138, 147–8, 152, 170, 176–8, 191–2, 219–20, 238, 287, 335, 407v. concept(词条和概念)205, 225 lexical functional grammar (词汇功能语法)245lexical gap(词汇空缺)174lexical learning(词汇学习)349lexical recognition(词汇认知)201–3, 207–9 lexical stress (see word stress)(词汇重音)(参见词重音)lexical substitutions in speech errors(语误中的词汇替换)207lexical tone(词调)43lexical verbs(词汇性动词)133lexicon(词库)4, 128, 131, 137–8, 147–8, 170–6, 199, 203, 217–18, 238, 345, 354, 407 grammatical properties in(词库中的语法特征)4, 147phonological properties in(词库中的音系特征)4, 147psycholinguistics and(心理语言学和词库)204–10semantic properties in (语义特征)4, 147 LF component of a grammar(语法的LF部分)5, 407Linear B(线性B)119linguistically determined variation(由语言决定着的变异,语言性质的变异)54–6linguistic experience of the child(儿童的语言经验)7–8linguistic variables and language use (语言的可变性和语言应用)47–58Linking Rules(链接规则)335Liquids(流音)33Literary Welsh (威尔士文学语言)164–5 Litotes(间接肯定法)397Liverpool(利物浦)63local attachment preferences(局部附加优势)372–3localisation of brain function(大脑功能的侧化)11–13Location(处所,位置)334Logical Form (LF) (逻辑形式)5, 246, 330, 339–45, 407logical object (逻辑宾语)5logical subject(逻辑主语)5, 374logic of conversation(会话逻辑)395–7 London(伦敦)65long vowels(长元音)37–8low as phonological feature(低舌位作为音系特征)413low vowels(低元音)36, 109–10 McMahon, A. (人名)232–3McNeill, D. (人名)286Malay(马来语)224Manner, Maxim of(方式,方式准则)397 manner of articulation(发音方式)29–30, 33 and language change(发音方式和语音变化)62–3Maori(毛利语)161, 225Maximal Onset Principle(首音最大化原则)82Meaning(意义)in sentence perception(句子感知中的意义)200meaning inclusion ( see also hyponymy) (意义包含(参见上下位关系))172, 178 meaning opposites(意义对立)175–6 memory for syntax(句法记忆)366 merger(合并)257–62, 306, 345, 407 constraints on (合并的条件限制)264 meronyms(部分关系词)174 meronymy(整体-部分关系)173–4, 208 metalanguage(元语言)336–7, 339 Meyerhoff, M. (人名)51mid closed vowels(中闭元音/半闭元音)38 Middle English(中古英语)231mid open vowels(中开元音/半开元音)38 mid vowels(中元音)36Milroy, J.(人名)51Milroy, L.(人名)51minimal pair(最小比对)75–6minimal responses(小型应对语)15 modifiers in compounds(复合词中的修饰语)148monophthongisation(单元音化)64–5 monophthongs(单元音)38 monosyllabic words(单音节词)41mood and speech acts(语气和言语行为)394–5morphemes(语素)140–3in aphasia(失语症中的语素)214–17 bound(粘着语素)140free(自由语素)140as minimal linguistic sign (语素作为最小的语言符号)140, 145morphological change(形态变化)233–7 morphological development in children (儿童的形态发展)188–92morphological irregularity (形态的不规则性)137morphological operations(形态操作)162–5 morphological processes(形态过程)140–50, 157–65, 407dissociation of in SLI(SLI中的形态的分离)219–20as features(形态作为特征)153 phonological conditioning of(形态的音系限制)152, 220realisations of(形态的实现)152 voicing as(浊化作为形态)164vowel change as(作为形态的元音变化)163–4morphological properties in sentence perception (句子感知中的形态特征)200 morphological variation(形态变异)233–7social contact and (社会接触和形态变异)237morphology(形态学)140, 165 phonological processes in(形态学中的音系过程)162–5morphs(形素)152motor control (运动神经控制)109, 113 movement in syntax (句法中的移位)246, 293–306, 340covert(句法中的隐性移位)345, 407in German(德语中句法移位)322–3 overt(显性句法移位)345, 407in sentence comprehension(句子理解过程中的句法移位)366Myhill, J. (人名)237Nahuatl (那瓦特语)161, 224narrow transcription(严式音标)77nasal as phonological feature(鼻音作为音系特征)85, 412nasalisation(鼻音化)40–1nasals(鼻,鼻音)30native speakers as sources of data(母语者作为语言数据的来源) 1natural classes in phonology(音系中的自然类)88–9Navajo(纳瓦霍语)83, 160Negation(否定)133in Child English(儿童英语中的否定)104 in CSE(CSE中的否定)312, 314–20in EME(EME中的否定)314–20 negative concord in AA VE(AA VE中的否定一致)312negative operator(否定算子)297 Neogrammarians(新语法学派学者)68 Neurolinguistics(神经语言学)1, 11–14 neutral context in lexical decision task(词汇确定任务中的中性语境)202new (v. old) information(新信息和旧信息)390New Y ork(纽约)57New Zealand English(新西兰英语)66, 71–2, 227, 230nodes in tree diagrams(树形图中的节点)258 nominal phrases(名词性短语/词组)in Child English(儿童英语中的名词性词组或短语)358–61as D-projections(名词性短语或词组作为D投射)286, 287, 349, 358, 361 nominative case(主格)248, 251, 265–6, 356, 360in AA VE(AA VE中的主格)272 nominative subjects in Child English(儿童语言中的主格主语)355–8noun incorporation(名词并入)161 nouns(名词)129–30and derivational morphology(名词和派生形态学)144in language acquisition(语言习得中的名词)186, 192–6and person(名词和人称)135in taxonomies(分析体系中的名词)173 non-concatenative morphology(非并置形态学)165non-count nouns(非复数名词)285non-finite clauses(非定式小句)in Child English(儿童英语中的非定式小句)353–61non-finite (v. finite) verb forms(非定式(和定式)动词形式)251–3in German SLI(德语SLI中的非定式动词形式)384–5non-rhotic dialects(非翘舌音方言)37–8, 57 non-standard dialects(非标准方言)15 non-words(非词)perception of (非词的感知)206–7 Norfolk(诺福克)66, 228Northern Cities Chain Shift(北城市链移)66–7, 68Northern English(北部英语)65, 69 Norwich(诺威奇)49, 235nucleus of syllable(音节的节核)41, 79 null constituents (see empty constituents)(空结构成分(参见空成分))null determiners(空限定词)283–7in Child English(儿童英语中的空限定词)358null infinitive particle(空不定式小品词)275null operator questions in Child English(儿童英语中的空疑问算子)352null subject language (空主语语言)320, 351 null subject parameter(空主语参数)319–20, 349, 352, 353, 361null subjects(空主语)in Child English(儿童英语中的空主语)352in Child Italian(儿童意大利语中的空主语)353identification of(空主语的识别)320, 352 in Japanese(日语中的空主语)392in non-finite clauses(非定式小句中的空主语)353–61in wh-questions(wh-疑问句中的空主语)353–4number(数)134errors in agrammatism(语法缺失中的数范畴错误)380errors in SLI(SLI中的数范畴错误)219 object(宾语)137objective case (see also accusative case)(宾格)248object language(对象语言)336–7, 339 obstruents(阻塞音)34, 79Old English(古英语)230, 231, 232, 233, 236Old French (古法语)229, 231old (v. new) information(旧信息)390Old Norse(古斯堪的那维亚语)230 omissions in speech errors(言语失误中的省减现象)115onsets of syllables(音节的首音)79–82in child language(儿童语言中的节首音)104in poetic systems(艺术表达手段系统中的节首音)118in speech errors(言语失误中的节首音)115operator expressions(算子表达)297, 340 in German(德语中的算子表达)323 operator movement(算子移位)297–302, 304, 306Optimality Theory(优选论)90–1 Optional Infinitive (OI) stage(不定式选择性使用阶段)357–8orthographic representation(规范书写法,正字法表示法)84orthography ( see also writing systems) (正字法(参见书写系统))27output representations in child phonology (儿童音系中的输出表达式)103–6 overextension in children’s word use(儿童词语运用中的泛化现象)192–3, 232 overregularisation(过渡规则化)lack of in SLI(SLI中过渡规则化的缺乏)220in morphological development(形态发展中的过渡规则化)190palatals(腭音,舌面中音)31palato-alveolars(舌面-齿龈音)31 paragrammatism(语法倒错型言语障碍)377, 382–3, 385parallel-interactive processing models (平行-交互式处理模式)199–204parameters(参数0 314–24in language acquisition(语言习得中的参数)349–54parameter setting(参数设定)350–4 parametric variation(参数变异)314–24 paraphasia(语言错乱)214–15, 217–19 parser(语法分析器)9, 372–5locality and(局部性和语法分析器)373–5 parsing(句法分析)366partitive interpretation of determiners(限定词的部分释义)284, 303part–whole relationship (see meronymy)(部分-整体关系(参见整体-部分关系))passive articulator(被动发音体)31 passive construction(被动结构)304–5 passive participle(被动分词)137, 146, 148 in German(德语中的被动分词)162 passive voice(被动语态)137, 146, 305 passivisation(被动化)306past participle(过去分词)136past tense morpheme in acquisition(习得过程中的过去时语素)189–90Patient (see Affected Object)(受事(参见受。

Language Learning Strategies 2-3

Inferencing: Using available information to guess meanings of new items, predict outcomes, or fill in missing information. 推测 Summarising: Making a mental, oral, or written summary of new information gained through listening or reading. 小结

O’Malley &ognitive

Cognitive

Social /Affective

元认知策略( 元认知策略(Metacognitive Strategies): ) 提前准备( 提前准备(advance organizers) ) 集中注意( 集中注意(directed attention) ) 功能准备 (Function planning) ) 选择注意(selective attention) 选择注意( ) 自我管理( 自我管理(self-management) ) 自我监控( 自我监控(self-monitoring) ) 自我评价( 自我评价(self-evaluation) )

metacognitive strategies are “higher order executive skills” and play a crucial role in learning, therefore, O’Malley et al (1985a) note that “students without metacognitive approaches are essentially learners without direction and ability to review their progress, accomplishments, and future learning directions”.

认知心理学 英文

认知心理学英文Cognitive PsychologyThe field of cognitive psychology has been a subject of intense study and research for decades, as it delves into the intricate workings of the human mind. This discipline aims to understand the processes by which individuals acquire, store, manipulate, and retrieve information, ultimately shaping their perceptions, thoughts, and behaviors. Cognitive psychology has emerged as a crucial branch of psychology, providing valuable insights into the complexities of the human cognitive system.At the core of cognitive psychology lies the concept of information processing. Researchers in this field investigate how the brain and the nervous system process, store, and retrieve information, much like a computer processes data. This approach involves studying various cognitive functions such as attention, perception, memory, language, problem-solving, and decision-making. By understanding these cognitive processes, cognitive psychologists can shed light on how individuals make sense of the world around them and how they navigate through their daily lives.One of the fundamental aspects of cognitive psychology is the study of attention. Attention refers to the ability to focus on specific stimuli or information while filtering out irrelevant or distracting elements. Cognitive psychologists have explored the different types of attention, such as selective attention, divided attention, and sustained attention, and how these processes influence our understanding and interpretation of the world. For instance, research has shown that individuals can selectively attend to certain stimuli while ignoring others, a phenomenon known as the "cocktail party effect," where people can focus on a specific conversation in a noisy environment.Memory, another crucial component of cognitive psychology, has been extensively studied. Researchers have delved into the different types of memory, such as sensory memory, short-term memory, and long-term memory, and the mechanisms by which information is encoded, stored, and retrieved. Understanding memory processes has significant implications for various fields, including education, where cognitive psychologists have contributed to the development of effective learning strategies and techniques.Language, as a uniquely human cognitive function, has also been a central focus of cognitive psychology. Researchers in this field have investigated the cognitive processes involved in language production, comprehension, and acquisition, shedding light on the complexinterplay between language and other cognitive functions. This includes exploring the neural mechanisms underlying language processing, as well as the role of language in shaping our thought processes and problem-solving abilities.Cognitive psychologists have also made significant contributions to the understanding of problem-solving and decision-making. By studying the cognitive processes involved in these activities, researchers have gained insights into how individuals approach and solve complex problems, as well as the factors that influence their decision-making. This knowledge has been applied in various domains, such as organizational management, public policy, and human-computer interaction.Moreover, cognitive psychology has played a crucial role in the development of artificial intelligence (AI) and the field of cognitive science. By studying the cognitive processes of the human mind, cognitive psychologists have provided valuable insights that have informed the design and development of intelligent systems and machines. This interdisciplinary collaboration has led to advancements in areas such as machine learning, natural language processing, and cognitive robotics.In recent years, cognitive psychology has also expanded its scope to explore the relationship between cognition and other aspects ofhuman experience, such as emotion, motivation, and social interaction. This holistic approach has led to a better understanding of how cognitive processes are influenced by and interact with these other psychological domains.As the field of cognitive psychology continues to evolve, it promises to offer even more valuable insights into the complexities of the human mind. By unraveling the intricate mechanisms of cognition, cognitive psychologists can contribute to the development of more effective interventions, educational strategies, and technological solutions that can enhance human performance and well-being. The ongoing research in this field holds the potential to revolutionize our understanding of the human mind and its remarkable capabilities.。

双语英文文本

双语英文文本Language has always been a fundamental aspect of human communication and interaction. In today's increasingly globalized world, the ability to navigate and thrive in multiple languages has become more important than ever before. One such linguistic phenomenon that has gained significant attention in recent years is the concept of bilingualism, where individuals possess proficiency in two or more languages.The benefits of bilingualism are multifaceted and far-reaching. At the cognitive level, numerous studies have shown that bilingual individuals exhibit enhanced executive function, problem-solving skills, and mental flexibility. The constant switching between languages and the need to inhibit one language while activating another, has been linked to the development of stronger cognitive control abilities. Bilingual individuals are often better at tasks that require selective attention, working memory, and the ability to shift between different mental sets.Moreover, bilingualism has been associated with delayed onset ofage-related cognitive decline and a reduced risk of developing certain types of dementia, such as Alzheimer's disease. The cognitive advantages of bilingualism are believed to stem from the brain's ability to adapt and reorganize its neural pathways in response to the demands of managing two or more languages. This "cognitive reserve" created by bilingualism can help offset the effects of age-related neurodegeneration, allowing bilingual individuals to maintain cognitive function for a longer period.Beyond the cognitive benefits, bilingualism also confers social and cultural advantages. Individuals who are proficient in multiple languages are better equipped to navigate diverse social and cultural contexts, fostering greater intercultural understanding and communication. The ability to engage with people from different linguistic and cultural backgrounds can open up a wealth of opportunities, both personal and professional. In an increasingly interconnected world, the skills and perspectives gained through bilingualism are highly valued in various fields, such as business, diplomacy, education, and healthcare.Furthermore, bilingualism can have a positive impact on educational outcomes. Studies have shown that bilingual children often outperform their monolingual peers in academic settings, particularly in areas such as language acquisition, literacy development, and problem-solving. The cognitive advantages associated withbilingualism, such as enhanced executive function and metalinguistic awareness, can contribute to improved academic performance across a range of subjects.However, it is important to note that the path to bilingualism is not always straightforward. The process of acquiring and maintaining proficiency in two or more languages can present various challenges, both linguistic and sociocultural. Factors such as age of acquisition, language exposure, educational environment, and societal attitudes towards bilingualism can all play a significant role in an individual's bilingual development.In some cases, individuals may experience language dominance, where one language becomes more dominant than the other, leading to potential imbalances in language proficiency. Additionally, some bilingual individuals may encounter instances of language interference, where the structures or vocabulary of one language influence the use of the other language, potentially resulting in language errors or code-switching.Nonetheless, these challenges can be navigated with the right support and resources. Families, educational institutions, and communities can play a crucial role in fostering and nurturing bilingual development, through the provision of targeted language instruction, exposure to diverse linguistic environments, and thepromotion of positive attitudes towards multilingualism.In conclusion, the phenomenon of bilingualism holds immense significance in the modern world. The cognitive, social, and educational benefits associated with the ability to fluently navigate two or more languages are undeniable. While the path to bilingualism may involve certain challenges, the rewards of becoming a bilingual individual far outweigh the obstacles. As we continue to embrace the diversity of languages and cultures in our increasingly interconnected global community, the importance of bilingualism will only continue to grow, shaping the way we communicate, collaborate, and understand one another.。

东师《英语课程与教学论》17春在线作业2

B. group correction

C. focus correcting

正确答案:

10. The first and most important step a teacher takes is to determine the () of an activity.

A. homework

B. communication task

C. exercise

D. listening activity

正确答案:

18. David Nunan (1991) offers () points to characterize the Communicative Approach:

B. learns to live with errors and learn from errors

C. recites words without understanding

D. seeks out all opportunities to use the target language

正确答案:

B. These student are very diligent

C. Iwant draw it

D. He goed there

正确答案:

9. If a writing task is more general (for example, developing informal letter writing skills), then what is the best approch of correction?

A. derivation

B. conversion

心理学专业名词中英对照(普通心理学)

StructuralismFunctionalismSensory ThresholdDark AdaptationBright AdaptationPerceptionBottom Up ProcessingTop Down Processing Perceptual Constancy Temporal PerceptionSensory MemoryShort-Term MemoryLong-Term MemoryEpisodic MemorySemantic MemoryImplicit MemoryExplicit MemoryDeclarative Memory Procedural MemoryPartial-Report Procedure Working MemoryThe Curve of ForgettingSerial Position EffectProactive Inhibition Retroactive InhibitionRapid Eye Movement Sleep, REM Selective AttentionSustained AttentionDivided AttentionFilter TheoryAttenuation TheoryAutomatic Processing Controlled Processing Convergent ThinkingDivergent ThinkingMental RotationConcept FormationAlgorithm StrategyHeuristic MethodMean-end AnalysisBackward SearchHill Climbing MethodFluencyFlexibility 构造主义机能主义感觉阈限暗适应明适应知觉自下而上的加工自上而下的加工知觉恒常性时间知觉感觉记忆短时记忆长时记忆情景记忆语义记忆内隐记忆外显记忆陈述性记忆程序性记忆局部报告法工作记忆遗忘曲线系列位置效应前摄抑制倒摄抑制快速眼动睡眠选择性注意持续性注意分配性注意过滤器理论衰减理论自动化加工受意识控制的加工辐合思维发散思维心理旋转概念形成算法策略启发法手段目的分析逆向搜索爬山法流畅性变通性OriginalityDialogue LanguageMonologue LanguageWritten LanguageInner LanguagePhysiological NeedSafety NeedBelongingness and Love Need Esteem NeedSelf Actualization NeedDeficit or Deficiency NeedGrowth NeedMoodIntense EmotionStressFluid IntelligenceCrystallized Intelligence Emotional IntelligenceGeneral FactorSpecific FactorMultiple-Intelligence Theory Triarchic Theory Intelligence Component Subtheory of Intelligence Meta-componentsPerformance Components Knowledge-Acquisition Components Successful IntelligencePlanning-Arousal-Simultaneous SuccessiveTemperamentCharacterCommon TraitsIndividual TraitsCardinal TraitsCentral TraitsSecondary TraitsExtraversionAgreeableness ConscientiousnessNeuroticismOpennessExtroversionIntroversionCognitive Style 独特性对话语言独白语言书面语言内部语言生理需要安全需要归属和爱的需要尊重的需要自我实现需要缺失需要成长需要心境激情应激流体智力晶体智力情绪智力一般因素特殊因素多元智力模型三元智力理论智力成分亚理论元成分操作成分知识获得成分Successful Intelligence PASS 模型气质性格共同特质个人特质首要特质中心特质次要特质外倾性宜人性责任心神经质/情绪稳定性开放性外倾人格内倾人格认知风格Field-Independent, (FI) Field-Dependent, (FD) Impulsivity Reflection Successive Simultaneous 场独立性场依存性冲动性沉思性继时性同时性。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Selective attention in the acquisition of the past tenseDan Jackson Rodger M. Constandse Garrison W. CottrellCognitive Science & Linguistics 0108 Computer Science & Engineering 0114 Computer Science & Engineering 0114Institute for Neural Computation Institute for Neural Computation University of California, San Diego University of California, San Diego University of California, San Diego La Jolla, CA 92093 La Jolla, CA 92093 La Jolla, CA 92093jackson@ rconstan@ gary@AbstractIt is well known that children generally exhibit a “U-shaped” pattern of development in the process of acquiring the past tense. Plunkett & Marchman (1991) showed that a connectionist network, trained on the past tense, would exhibit U-shaped learning effects. This network did not completely master the past tense mapping, however. Plunkett & Marchman (1993) showed that a network trained with an incrementally expanded training set was able to achieve acceptable levels of mastery, as well as show the desired U-shaped pattern. In this paper, we point out some problems with using an incrementally expanded training set. We propose a model of selective attention that enables our network to completely master the past tense mapping and exhibit U-shaped learning effects without requiring external manipulation of its training set.IntroductionIt is well known that in the process of acquiring the past tense, children generally exhibit a “U-shaped” pattern of development. The first past tense forms produced are generally correct, regardless of whether or not those forms are regular. After this period of correct performance, children go through a period of overgeneralization in which irregular forms are incorrectly inflected (e.g. goed). Finally, children seem to identify some forms as exceptions to the general regular pattern, and the overgeneralization errors decrease. Plunkett & Marchman (1991) (P&M hereafter) showed that U-shaped learning effects can emerge in connectionist networks in the absence of any discontinuities in the training regime.1 P&M showed that such networks go through “micro U-shaped development.” This is contrasted with the idealized vision of “macro U-shaped development”that predominates in anecdotal descriptions of children’s patterns of acquisition. Macro U-shaped development refers to a rapid and sudden change from the memorization stage, where regular and irregular forms are reproduced with relatively equal levels of error, to a stage where the /-ed/ suffix is applied indiscriminately, resulting in overgeneralization for all irregular verbs. Micro U-shaped 1 See Pinker and Prince’s (1988) critique of Rumelhart & McClelland (1986). They argue that Rumelhart & McClelland’s model exhibited U-shaped learning effects because of discontinuities in its training set.development, on the other hand, is characterized by selective application of the /-ed/ suffix, resulting in a period in which some irregular verbs are regularized, while others are produced correctly. Although most anecdotal descriptions of children’s acquisition of the past tense have implied macro U-shaped development, studies of naturalistic past tense production (e.g. Marcus et al. (1992)) and studies using elicitation procedures (e.g. Marchman (1988)) show that micro U-shaped development is a better description of how children learn the past tense.Although P&M (1991) were successful in showing that connectionist networks go through a micro U-shaped pattern of development, none of the networks they trained achieved mastery of all of the past tense mappings. In particular, the mean performance on the regular (add /-ed/) mapping was 84% (P&M (1991), p. 71), which is well below the percentage of regulars that most adult humans are able to inflect correctly (near 100%).P&M (1993) demonstrated that networks can achieve acceptable levels of mastery and still show U-shaped learning effects if their training set is expanded incrementally. Unlike Rumelhart & McClelland (1986), they did not introduce a discontinuity in the training regime. Rather, they trained their networks on a small number of verbs at first, and then gradually expanded the training set. Trained in this way, the networks described by P&M (1993) were able to master the given vocabulary (correctly inflecting 97-98% of the regulars) after a period of micro U-shaped development.This is an interesting result, but the use of an incrementally expanding training set must be justified. P&M (1993) note that “verb acquisition in children is a gradual process which follows an incremental learning trajectory (p. 27),” and go on to mention Elman’s (1991) application of incremental training to the acquisition of simple and complex syntactic forms. There are, however, some crucial differences between the account of language acquisition implied by Elman’s model and that implied by P&M (1993).Elman’s recurrent network was unable to learn adequately if it was trained on the entire set of simple and complex sentences at once. He showed that it could learn if it was trained on an incrementally expanded training set, beginning with the simple sentences, and working up to the complex ones. Nevertheless, he argued explicitly against using anincrementally expanded training set in models of language acquisition, claiming that “children hear exemplars of all aspects of the adult language from the beginning (p. 6).” He then tried expanding his network’s memory capacity, rather than incrementally expanding its training set. During the first phase of training, the recurrent feedback was eliminated after every third or fourth word. As training progressed, the network’s memory window was gradually increased until the feedback was no longer interfered with at all.Using this schedule of expanding memory, Elman was able to get the network to learn the entire training set. This is a reasonable account of language acquisition because we know that children have limited memory capacity early in development, and that this capacity increases as development continues. Furthermore, the network is exposed to the entire adult language, which is more realistic than using a subset of the language for training.P&M’s (1993) model did not have a limited memory--it was not a recurrent network, and did not have a memory in the sense that Elman’s (1991) model did. P&M had to resort to limiting its training set, which was then gradually expanded. P&M (1993) claim that it is “unlikely that children attempt to learn an entire lexicon all of a piece (p.27).” Perhaps what they had in mind was that children have access to the entire vocabulary, but only pay attention to a limited number of words. In this case, the way they have modeled attention is questionable. At the outset of training, the network was given 20 verbs, on which it is trained to 100% accuracy before expansion began. In effect, the network was being told which verbs to pay attention to at the outset, and trained on them to perfection before it could start attending to other verbs. By the end of training, the network had the entire vocabulary in its training set--it was paying attention to each element of the vocabulary to the same degree. Clearly, we need a better way to model attention.In this paper, we examine the effect of selective attention on a network’s ability to learn the past tense mappings. We do not specify the examples to which the network should pay attention, and we do not restrict the set of examples to which the network can be exposed. Like Elman, we believe that in order for our model to be realistic, the entire vocabulary must be accessible to the network from the start. We show that networks with this mechanism of selective attention master the past tense mapping and exhibit micro U-shaped learning effects in the absence of any external manipulation of their training set.Selective Attention ModelOur model of selective attention is based on the method of active selection (Plutowski & White (1993)). This method was originally used for incrementally growing a training set by using a partially trained network to guide the selection of new examples. Plutowski et al (1993) introduced the idea of using maximum error as the criterion for selection. In our implementation, this criterion is used for selecting examples for weight adjustment (cf. Baluja & Pomerleau (1994), whose network ignores sections of the input with high prediction error). Instead of using active selection for incrementally growing the training set, we assume a fixed size training queue of size N corresponding to the child's working or perhaps episodic memory. As the child samples the environment, we assume the child computes his error on any verb, and then compares this error with what is currently in the training queue. If the error on the sampled example is worse than what is currently in the queue, the example is inserted in the queue and the best example in the queue is "forgotten." We may view this error as a measure of the novelty or salience of the verb.To simulate this, at the beginning of an epoch the simulator randomly selects a window of W examples from the vocabulary and tests the network on them. The likelihood of any particular example being chosen for the sample window depends on its frequency in the vocabulary. The above procedure is applied to update the queue. Thus, the entire set of examples may change from one epoch to the next depending on N, W, and the error on the samples.The network’s initial exposure to a form results in its being placed in the sample window. Weight adjustment does not occur until the form has been put into the training queue. Training on a verb is therefore “off-line” in the sense that it occurs some time after the verb is initially encountered.It is reasonable to suppose that children are not able to cycle through every verb in the language in order to choose the ones they need to pay attention to for the purposes of synaptic adjustment, so it was important to limit the size of the sample window. We might think of the window as the network’s short-term memory (for recently heard verbs). It needs to hold a limited number of items in memory so that it can compare them to choose the queue elements when updating the queue.MethodsOur input-output pairs were taken from the database used by P&M. The interested reader should refer to P&M (1991, 1993) for details about the representations. The network is given a verb stem as input and must produce the inflected verb as its output. The transformations from the stems to the past tense forms are classified into four possible classes: arbitrary, identity, vowel change, and regular. Each of these corresponds to a possible English past tense transformation.Arbitrary Identity VowelChangeRegularTypeFrequency22068410TokenFrequency100251Table 1: Type and Token frequencies of the past tensemappingsFor the arbitraries, there is no relation between the stem and the past tense form, e.g. ‘go→went.’ For the identities, the past tense form is identical to the verb stem. This mapping requires that the verb stem end in a dental consonant (/t/ or /d/), e.g. ‘hit→hit.’ For the vowel changes, a vowel in the stem may be replaced by a differentQueue SizeF r a c t i o n C o r r e c tFigure 1: Performance on regular verbs after 120,000 weightupdates as a function of queue and window size.vowel in the inflected form of the verb, depending on the original vowel and the consonant that follows. We had 10different types of vowel changes in our vocabulary,analogous to ‘ring →rang,’ ‘blow →blew,’ etc. Finally, for the regulars, a suffix is appended to the verb stem. The form of the suffix depends upon the final vowel/consonant in the stem. If the stem ends in a dental (/t/ or /d/), then the suffix is /-id/, e.g. 'pat →pat-id.’ If the stem ends in a voiced consonant or vowel, then the suffix is voiced /d/, e.g.'dam →dam-d.’ If the stem ending is unvoiced, the suffix is unvoiced /t/, e.g. 'pak →pak-t.’The type and token frequencies of each of these classes in our vocabulary are shown in Table 1. The type frequencies are identical to those used by P&M (1991), but the token frequencies are somewhat different. For each type of past tense mapping, we took the averages of a small, but representative sample of verb frequencies from Kucera &Francis (1967), and then normalized them by the frequency of the regulars.Our networks were trained with the back propagation algorithm. The network architecture consisted of 18 input units (each verb stem was formed from 3 phonemes each requiring 6 units to represent), 30 hidden units and 20 output units (2 suffix units were needed in addition to the transformed stem). The choice of 30 hidden units was made to parallel the architecture used by P&M (1993). The learning rate and momentum were also set according to the values used by P&M (1993), namely a learning rate of 0.1and a momentum of 0.0. To evaluate network performance,the output for each phoneme in the stem was mapped to the closest legal phoneme (using Euclidean distance). Then the output was compared with the target.We investigated the effects of different sample window and training queue sizes by letting W and N take on the values 1, 2, 4 or 8 and training networks with all sixteen possible combinations. Five sets of networks were trained, with initial weight values the same within each set, but varying between them.ResultsFigure 1 shows the effect of using different training queue and sample window sizes. The average performance for each combination of W and N is plotted in Figure 1, with standard deviation indicated by error bars. The networks that performed best were the ones that had large sample windows and small training queues. The larger the sample window,the more examples the network has to choose from. Once an example is chosen and trained on, however, the network's error will change not only for that verb, but for other verbs as well. If the network trains on a regular verb, for example, we expect its error on other regular verbs to go down slightly, as well. Thus, it is better for the network to "pay attention to one thing at a time," because this allows it to choose its training example based on its error on that example immediately prior to training, rather than using an error value that may have changed due to training on another verb in the queue.Figure 2 shows the average performance of 5 networks trained using the selective attention mechanism with sample windows of size 8 and training queues of size 1. Because of the method of training we are using, it is more meaningful to analyze the networks according to the number of weight updates they have undergone. This makes it difficult to compare our results with those of P&M, however, because they graph results in terms of epochs, and the size of the training set changes with each epoch. For the purposes of comparison, therefore, we ran 5 networks using the traditional method for selecting training examples (the one used by P&M (1991)) on the same data. The average performance of these networks on regular verbs is shown in figure 3.The networks with selective attention performed very well. By 125,000 weight updates, all 5 networks had mastered all of the past tense mappings (with a standard deviation of 0.0). When the networks without selective attention had reached 125,000 weight updates, they only inflected an average of 85% of the regulars correctly (with a standard deviation of 0.013). This is the level of performance reached by P&M’s (1991) best network at the end of training (p. 71). Even after 500,000 weight updates,these networks only got an average of 95% correct (with a standard deviation of 0.007). In summary, the network with selective attention was better both in final performance and learning speed.Figure 4 shows the networks' ability to generalize. The first graph shows the average performance of the five networks on novel verbs that did not fall into any of the vowel change classes or end in a dental consonant--the indeterminates. The error bars indicate standard deviation.Weight Updates (thousands)Figure 2: Average fraction correct and standard deviation for the five selective attention networks tested on all of the regular,arbitrary, vowel change and identity verbs in the training set.As can be seen in the graph, the networks generalize fairly well. The dashed line shows the fraction of indeterminate novel verbs the networks inflected with a suffix (around 90%), irrespective of whether the form of the stem was correct. The dashed line shows the fraction of indeterminate novel verbs the networks inflected as regulars with no changes to the stem (around 70%).The novel dental and vowel change graphs show that the regular mapping is not applied indiscriminately to novel forms--the fraction of verbs inflected as regulars is lower in these graphs. The networks have learned something about the phonological regularities inherent in the vocabulary. In particular, the novel vowel change graph shows that verbs that are phonologically similar to the vowel change verbs in the training set are as likely to be inflected with a vowel change as they are to be regularized.Figure 5 shows the number of times each verb token was in the training queue for a particular simulation. Note that some regular verbs never make it into the queue, i.e. are never trained on. Since we happen to know all verbs were sampled, the network must have had low error on these verbs when they were in the window. This is further evidence that the network has learned the regular rule, and shows that our procedure avoids unnecessary computation.DiscussionWe have presented a model of selective attention which chooses training examples from a random sample of the training set. The size of the window from which the training example can be chosen is limited and the training queue itself is limited. Whether only one or both of these should be considered "memory" is a question of interpretation, but here we have suggested that the queue can be considered the memory. One could also break the processing down into two stages, one where samples are put into memory for later processing, and then a stage in which they are organized according to salience, and then practiced. The idea that children process a significant amount of the linguistic input they receive after the fact is corroborated by data concerning crib speech--monologues and language practice (including grammatical modifications and imitation/repetition) that children engage in when they are alone in their bed before going to sleep (Jespersen (1922), Weir (1962), Kuczaj (1983)). Crib speech is characterized by a freedom (because of the lack of communicative intent) to use free association to generate sequences of sounds and words, the associations being either phonological, syntacticFigure 3: Average fraction correct and standard deviation for five networks without selective attention tested on regularverbs.or semantic (Britton (1970)). Probably because of this freedom, children are more likely to engage in language practice in crib speech than in social-context speech (in terms of relative frequency) (Black (1979), Britton (1970), Kuczaj (1983)).As Kuczaj writes:…children process linguistic information at (at least) two levels: (a) the level of initial processing, which occurs in short-term memory shortly after children have been exposed to the input, and (b) the level of post-initial processing, which occurs at some later time when children are attempting to interpret, organize, and consolidate information that they have experienced over some longer period of time...children are most likely to notice discrepancies between their knowledge of language and linguistic input at the level of post-initial processing, and...crib speech is a context in which children may freely engage in overt behaviors that facilitate both post-initial processing and the successful resolution of moderately discrepant events. Although older children and adults may be able to notice discrepancies during the initial processing of linguistic information, it is unlikely that young children are able to do so...Children may initially store new forms and new meanings and later compare these new acquisitions with previous ones in post-initial processing (Kuczaj (1983), pp. 167-168).The model we have presented is completely compatible with these observations, if one assumes both the queue and the window are part of the memory. The “discrepancies” in this case are the error signals the network generates for each verb in the sample window. The network can generate the form it expects to see in a particular context, and compare this with what it actually heard. In this way, the network supplies itself with indirect negative evidence (Elman (1991)), which is used in the adjustments of its weights. As Kuczaj suggests is true for children, our networks could notWeight Updates (thousands)Weight Updates (thousands) FractionofVerbsWeight Updates (thousands) FractionofVerbsFigure 4: Average generalization on 132 novel indeterminates, 62 novel vowel change verbs and 28 noveldentals.0 Figure 5: Total number of times each verb token was in the training queue for a single simulation. Verbs with indices 1-2 are arbitrary, 3-70 are vowel change, 71-90 are identity and 91-500 are regular.“notice” the discrepancies during the initial processing of the linguistic information. The initial processing occurs when the verb is put into the sample window. Later, when the time comes to update a network’s weights, the mechanism of selective attention comes into play. At this point, the network generates error signals and chooses the verb with the highest error for the purposes of weight adjustment.In future work, we may try to develop a connectionist implementation of the training queue. We would also like to investigate other strategies for deciding what the network should pay attention to. Finally, we plan to use our model of selective attention in more primary tasks, such as learning word meaning.ConclusionThe mechanism of selective attention we introduced allowed the networks to guide their own training. The networks focused on the examples for which they needed the most training. As a result, they performed extremely well. They completely mastered the regular, identity, vowel change and arbitrary past tense mappings and showed the ability to generalize. They also showed micro U-shaped learning effects. Most importantly, our networks achieved their high level of performance without requiring us to externally manipulate their training sets.AcknowledgmentsWe would like to thank the GEURU research group for helpful comments. This research was supported in part by NSF grant IRI 92-03532.ReferencesBaluja, S. & Pomerleau, D.A. (1994) “Using a saliency map for active spatial selective attention: implementation & initial results.” In: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 7, (Tesauro, Touretsky & Leen, eds.). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.Black, R. (1979) “Crib talk and mother-child interaction: A comparison of form and function. Papers and reports on child language development, 17, 90-97.Britton, J. (1970) Language and learning. London: Penguin Books.Elman, J. (1991) “Incremental learning, or the importance of starting small.” CRL Technical Report No. 9101. University of California, San Diego.Jespersen, O. (1922) Language: its nature, development and origin. New York: Allen and Unwin.Kucera, H. & Francis, W.N. (1967) Computational analysis of present-day American English. Providence, RI: Brown University Press.Kuczaj, S.A. (1983) Crib speech and language play. New York: Springer-Verlag.Marchman, V. (1988) “Rules and regularities in the acquisition of the English past tense.” Center for Research in Language Newsletter, 2 (4).Marcus, G.F., Ullman, M., Pinker, S., Hollander, M., Rosen, T.J., & Xu, F. (1992) “Overregularization in language acquisition.” Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 57 (4), Serial No. 228.Plunkett, K., Marchman, V. (1991) "U-shaped learning and frequency effects in a multi-layered perceptron: Implications for child language acquisition." Cognition 38, 43-102.Plunkett, K., Marchman, V. (1993) " From Rote Learning to System Building: Acquiring Verb Morphology in Children and Connectionist Nets." Cognition 48, 21-69. Plutowski, M., White, H. (1993) “Selecting concise training sets from clean data” IEEE Transactions on neural networks, 3:1.Plutowski, M., Cottrell G.W., White, H. (1993) “Learning Mackey-Glass from 25 examples, plus or minus 2.” In: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 6, (Hanson, Cowan and Giles, eds.). San Mateo, CA: Morgan Kaufmann.Rumelhart, D. E., McClelland, J.L. (1986) "On Learning the Past Tense of English Verbs", PDP: Explorations in the Microstructure of Cognition, Vol 2.Weir, R.H. (1962) Language in the crib. The Hague: Mouton.。