INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES IN DYSLEXIA

motivation in language learning tesol internation

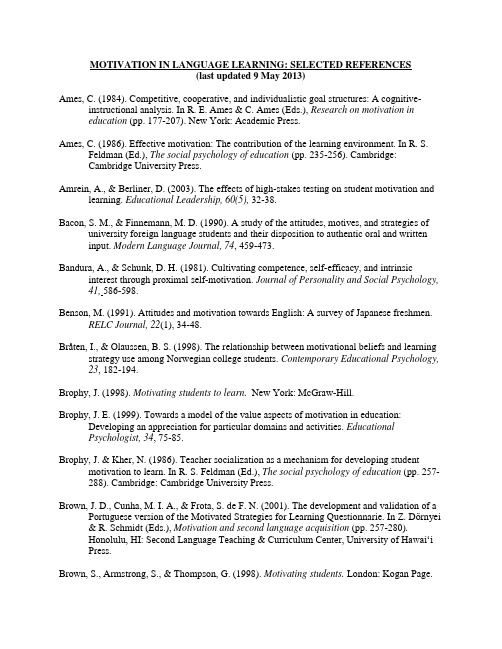

MOTIVATION IN LANGUAGE LEARNING: SELECTED REFERENCES(last updated 9 May 2013)Ames, C. (1984). Competitive, cooperative, and individualistic goal structures: A cognitive-instructional analysis. In R. E. Ames & C. Ames (Eds.), Research on motivation ineducation (pp. 177-207). New York: Academic Press.Ames, C. (1986). Effective motivation: The contribution of the learning environment. In R. S.Feldman (Ed.), The social psychology of education (pp. 235-256). Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.Amrein, A., & Berliner, D. (2003). The effects of high-stakes testing on student motivation and learning. Educational Leadership, 60(5), 32-38.Bacon, S. M., & Finnemann, M. D. (1990). A study of the attitudes, motives, and strategies of university foreign language students and their disposition to authentic oral and writteninput. Modern Language Journal, 74, 459-473.Bandura, A., & Schunk, D. H. (1981). Cultivating competence, self-efficacy, and intrinsic interest through proximal self-motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41, 586-598.Benson, M. (1991). Attitudes and motivation towards English: A survey of Japanese freshmen.RELC Journal, 22(1), 34-48.Bråten, I., & Olaussen, B. S. (1998). The relationship between motivational beliefs and learning strategy use among Norwegian college students. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 23, 182-194.Brophy, J. (1998). Motivating students to learn. New York: McGraw-Hill.Brophy, J. E. (1999). Towards a model of the value aspects of motivation in education: Developing an appreciation for particular domains and activities. EducationalPsychologist, 34, 75-85.Brophy, J. & Kher, N. (1986). Teacher socialization as a mechanism for developing student motivation to learn. In R. S. Feldman (Ed.), The social psychology of education (pp. 257-288). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Brown, J. D., Cunha, M. I. A., & Frota, S. de F. N. (2001). The development and validation of a Portuguese version of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnarie. In Z. Dörnyei & R. Schmidt (Eds.), Motivation and second language acquisition (pp. 257-280).Honolulu, HI: Second Language Teaching & Curriculum Center, University of Hawai‘i Press.Brown, S., Armstrong, S., & Thompson, G. (1998). Motivating students. London: Kogan Page.Chambers, G. (1999). Motivating language learners. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters. Cheng, H-F., & Dörnyei, Z. (2007). The use of motivational strategies in language instruction: The case of EFL teaching in Taiwan. Innovation in language learning and teaching, 1,153-174.Cohen, M., & Dörnyei, Z. (2002). Focus on the language learner: Motivation, styles and strategies. In N. Schmidt (Ed.), An introduction to applied linguistics (pp. 170-190).London, UK: Arnold.Cooper, H., & Tom, D. Y. H. 1984. SES and ethnic differences in achievement motivation. In R.E. Ames & C. Ames (Eds.), Motivation in education (pp. 209-242). New York:Academic Press.Cranmer, D. (1996). Motivating high level learners. Harlow, UK: Longman.Crookes, G., & Schmidt, R. W. (1991). Motivation: Re-opening the research agenda. Language Learning, 41, 469-512.Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Nakamura, J. (1989). The dynamics of intrinsic motivation: A study of adolescents. In R. Ames & C. Ames (Eds.), Handbook of motivation theory and research, Vol. 3: Goals and cognitions (pp. 45–71). New York, NY: Academic Press.Csizér, K., & Dörnyei, Z. (2005). Language learners’ motivational profiles and their motivated learning behavior. Language Learning, 55, 613-659.Csizér, K., Kormos, J., & Sarkadi, Á. (2010). The dynamics of language learning attitudes and motivation: Lessons from an interview study of dyslexic language learners. ModernLanguage Journal, 94(3), 470-487.deCharms, R. (1984). Motivation enhancement in educational settings. In R. E. Ames & C.Ames (Eds.), Motivation in education (pp. 275-310). New York: Academic Press. Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York, NY: Plenum.Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1991). A motivational approach to self: Integration in personality. In R. A. Dienstbier (Ed.), Perspectives on motivation: Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1990 (pp. 237-288). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.Deci, E. L., Vallerand, R. J., Pelletier, L. G., & Ryan, R. M. (1991). Motivation and education: The self-determination perspective. Educational Psychologist, 26(3 & 4), 325-346.De Volder, M. L., & Lens, W. (1982). Academic achievement and future time perspective as a cognitive-motivational concept. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44, 20-33Dörnyei, Z. (1990). Conceptualizing motivation in foreign language learning. Language Learning, 40, 45-78.Dörnyei, Z. (1994). Motivation and motivating in the foreign language classroom. Modern Language Journal,78, 273-284.Dörnyei, Z. (1998). Motivation in second and foreign language learning. Language Teaching, 31, 117-135.Dörnyei, Z. (2001). Motivational strategies in the language classroom. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.Dörnyei, Z. (2001). Teaching and researching motivation. Harlow, UK: Longman.Dörnyei, Z. (2002). The motivational basis of language learning tasks. In P. Robinson (Ed.), Individual differences and instructed language learning (pp. 137-158). Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins.Dörnyei, Z. (2003). Attitudes, orientations, and motivations in language learning: Advances in theory, research, and applications. Language Learning, 53(Supplement 1), 3-32.Dörnyei, Z. (2007). Creating a motivating classroom environment. In J. Cummins & C. Davison (Eds.), International Handbook of English Language Teaching (Vol. 2) (pp. 719-731).New York, NY: Springer.Dörnyei, Z. (2008). New ways of motivating foreign language learners: Generating vision. Links, 38(Winter), 3-4.Dörnyei, Z. (2009). The L2 motivational self system. In Z. Dörnyei & E. Ushioda (Eds.), Motivation, language identity and the L2 self (pp. 9-42).Tonawanda, NY: MultilingualMatters.Dörnyei, Z., & Csizér, K. (1998). Ten commandments for motivating language learners: Results of an empirical study. Language Teaching Research, 2, 203-229.Dörnyei, Z., & Csizér, K. (2002). Some dynamics of language attitudes and motivation: Results of a longitudinal nationwide survey. Applied Linguistics, 23, 421-462.Dörnyei, Z., & K. Csizér. (2002). Some dynamics of language attitudes and motivation: Results of a longitudinal nationwide survey. Applied Linguistics, 23, 421–462.Dörnyei, Z., Csizér, K., & Németh, N. (2006). Motivation, language attitudes, and globalization:A Hungarian perspective. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.Dörnyei, Z., & Ottó, I. (1998). Motivation in action: A process model of L2 motivation. Working Papers in Applied Linguistics, 4, 43-69.Dörnyei, Z., & Schmidt, R. (Eds.). (2001). Motivation and second language acquisition.Honolulu: National Foreign Language Resource Center/ University of Hawai'i Press.Dörnyei, Z., & Skehan, P. (2003). Individual differences in second language learning. In C. J.Doughty & M. H. Long (Eds.), The handbook of second language acquisition (pp. 589-630). Malden, MA: Blackwell.Dweck, C. S. (1986). Motivational processes affecting learning. American Psychologist, 41, 1040-1048.Ehrman, M. (1996). An exploration of adult language learner motivation, self-efficacy, and anxiety. In R. Oxford (Ed.), Language learning motivation: Pathways to the new century (pp. 81-103). Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai’i Press.Gao, Y., Zhao, Y., Cheng, Y., & Zhou, Y. (2004). Motivation types of Chinese university undergraduates. Asian Journal of English Language Teaching, 14, 45-64.Gardner, R. (1985). Social psychology and second language learning: The role of attitude and motivation. London, UK: Edward Arnold.Gardner, R. (2001). Integrative motivation and second language acquisition. In Z. Dörnyei & R.Schmidt (Eds.), Motivation and language acquisition (pp. 1-19). Honolulu, HI:University of Hawai’i Press.Gardner, R. C. (2000). Correlation, causation, motivation, and second language acquisition.Canadian Psychology, 41, 10-24.Gardner, R. C. (2001). Integrative motivation: Past, present and future. Retrieved from ://publish.uwo.ca/~gardner/docs/GardnerPublicLecture1.pdfGardner, R. (2001). Integrative motivation and second language acquisition. In Z. Dörnyei & R.Schmidt (Eds.), Motivation and language acquisition (pp. 1-19). Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.Gardner, R. C. (2005). Integrative motivation and second language acquisition. Retrieved from ://publish.uwo.ca/~gardner/docs/caaltalk5final.pdfGardner, R. C. (2009). Gardner and Lambert (1959): Fifty years and counting. Retrieved from ://publish.uwo.ca/~gardner/docs/CAALOttawa2009talkc.pdfGardner, R. C., & Lambert, W. E. (1959). Motivational variables in second language acquisition.Canadian Journal of Psychology, 13, 266-272.Gardner, R. C., & Lambert, W. E. (1972). Attitudes and motivation in second language learning. Rowley, MA: Newbury House.Gardner, R. C., Masgoret, A.-M., Tennant, J., & Mihic, L. (2004). Integrative motivation: Changes during a year-long intermediate-level language course. Language Learning, 54, 1-34.Gardner, R. C., & Smythe, P. C. (1981). On the development of the attitude/ motivation test battery. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 37, 510-525.Gardner, R. C., & Tremblay, P. F. (1994). On motivation, research agendas, and theoretical frameworks. The Modern Language Journal, 78, 359-368.Grabe, W. (2009). Motivation and reading. In W. Grabe (Ed.), Reading in a second language: Moving from theory to practice (pp. 175-193). New York, NY: Cambridge UniversityPress.Graham, S. (1994). Classroom motivation from an attitudinal perspective. In H. F. J. O'Neil and M. Drillings (Eds.), Motivation: Theory and research (pp. 31-48). Hillsdale, NJ:Lawrence Erlbaum.Guilloteaux, M. J., & Dörnyei, Z. (2008). Motivating language learners: A classroom-oriented investigation of the effects of motivational strategies on student motivation. TESOLQuarterly, 42, 55-77.Hadfield, J. (2013). A second self: Translating motivation theory into practice. In T. Pattison (Ed.), IATEFL 2012: Glasgow Conference Selections (pp. 44-47). Canterbury, UK:IATEFL.Hao, M., Liu, M., & Hao, R. (2004). An empirical study on anxiety and motivation in English asa Foreign Language. Asian Journal of English Language Teaching, 14, 89-104.Hara, C., & Sarver, W. T. (2010). Magic in ESL: An observation of student motivation in an ESL class. In G. Park, H. P. Widodo, & A. Cirocki (Eds.), Observation of teaching:Bridging theory and practice through research on teaching (pp. 141-153). Munich,Germany: LINCOM EUROPA.Hashimoto, Y. (2002). Motivation and willingness to communicate as predictors of reported L2 use: The Japanese ESL context. Retrieved from :///sls/uhwpesl/20(2)/Hashimoto.pdf.Hawkins, J. N. (1994). Issues of motivation in Asian education. In H. F. O’Neill & M. Drillings (Eds.), Motivation—theory and research (pp. 101-115). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Hsieh, P. (2008). Why are college foreign language students' self-efficacy, attitude, and motivation so different? International Education, 38(1), 76-94.Huang, S. (2010). Convergent vs. divergent assessment: Impact on college EFL students’ motivation and self-regulated learning strategies. Language Testing, 28(2), 251-270.Keller, J. M. (1983). Motivational design of instruction. In C. M. Reigeluth (Ed.), Instructional design theories and models (pp. 386-433). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.Kim, S. (2009). Questioning the stability of foreign language classroom anxiety and motivation across different classroom contexts. Foreign Language Annals, 42(1), 138-157. Komiyama, R. (2009). CAR: A means for motivating students to read. English Teaching Forum, 47(3), 32-37.Kondo-Brown, K. (2001). Bilingual heritage students’ language contact and motivation. In Z.Dörnyei & R. Schmidt (Eds.), Motivation and language acquisition (pp. 433-460).Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai’i Press.Koromilas, K. (2011). Obligation and motivation. Cambridge ESOL Research Notes, 44, 12-20.Lamb, M. (2004). Integrative motivation in a globalizing world. System, 32, 3-19.Lamb, T. (2009). Controlling learning: Learners’ voices and relationships between motivation and learner autonomy. In R. Pemberton, S. Toogood, & A. Barfield (Eds.), Maintaining control: Autonomy and language learning (pp. 67-86). Hong Kong: Hong KongUniversity Press.Lau, K.-l., & Chan, D. W. (2003). Reading strategy use and motivation among Chinese good and poor readers in Hong Kong. Journal of Research in Reading, 26, 177-190.Lepper, M. R. (1983). Extrinsic reward and intrinsic motivation: implications for the classroom.In J. M. Levine & M. C. Wang (eds.), Teacher and student perceptions: implications for learning (pp. 281-317). Hillsdale, NJ; Erlbaum.Li, J. (2009). Motivational force and imagined community in ‘Crazy English.’ In J. Lo Bianco, J.Orton, & Y. Gao (Eds.), China and English: Globalisation and the dilemmas of identity(pp. 211-223). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.Lopez., F. (2010).Identity and motivation among Hispanic ELLs. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 18(16), 1-29.MacIntyre, P. D. (2002). Motivation, anxiety and emotion in second language acquisition. In P.Robinson (Ed.), Individual differences and instructed language learning (pp. 45-68).Amsterdam, The Netherlands: John Benjamins.MacIntyre, P. D., MacMaster, K., & Baker, S. C. (2001). The convergence of multiple models of motivation for second language learning: Gardner, Pintrich, Kuhl, and McCroskey. In Z.Dörnyei & R. Schmidt (Eds.), Motivation and language acquisition (pp. 461-492).Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai’i Press.Maehr, M. L. & Archer, J. (1987). Motivation and school achievement. In L. G. Katz (ed.), Current topics in early childhood education (pp. 85-107). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.Manderlink, G., & Harackiewicz, J. M. 1984. Proximal versus distal goal setting and intrinsic motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47, 918-928.Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224-253.Maslow, A. H. (1970). Motivation and personality. New York, NY: Harper & Row.McCombs, B. L. (1984). Processes and skills underlying continued motivation to learn.Educational Psychologist, 19(4), 199-218.McCombs, B. L. (1988). Motivational skills training: combining metacognitive, cognitive, and affective learning strategies. In C. E. Weinstein, E. T. Goetz & P. A. Alexander (Eds.),Learning and study strategies (pp.141-169). New York: Academic Press.McCombs, B. L. (1994). Strategies for assessing and enhancing motivation: keys to promoting self-regulated learning and performance. In H. F. O’Neill & M. Drillings (Eds.),Motivation: theory and research (pp. 49-69). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.McCombs, B. L., & Whisler, J. S. (1997). The learner-centered classroom and school: Strategies for increasing student motivation and achievement. San Francisco. CA:Jossey-Bass.McCrossan, L. (2011). Progress, motivation and high-level learners. Cambridge ESOL Research Notes, 44, 6-12.Melvin, B. S., & Stout, D. S. (1987). Motivating language learners through authentic materials.In W. Rivers (Ed.), Interactive language teaching (pp. 44–56). New York, NY:Cambridge University Press.Midraj, S., Midraj, J., O’Neil, G., Sellami, A., & El-Temtamy, O. (2007). UAE grade 12 students’ motivation & language learning. In S. Midraj, A. Jendli, & A. Sellami (Eds.), Research in ELT contexts (pp. 47-62). Dubai: TESOL Arabia.Molden, D. C., & Dweck, C. S. (2000). Meaning and motivation. In C. Sansone & J.Harackiewicz (Eds.), Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: The search for optimalmotivation and performance (pp. 131-159). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.Mori, S. (2002). Redefining motivation to read in a foreign language. Reading in a Foreign Language, 14, 91-110.Noels, K. A., Clément, R., & Pelletier, L. G. (1999). Perceptions of teachers’ communicative style and students’ intrinsic and extrinsic motivation.Modern Language Journal,83, 23-34.Noels, K. A., Pelletier, L. G., Clément, R., & Vallerand, R. J. (2000). Why are you learning a second language?: Motivational orientations and self-determination theory. LanguageLearning, 50, 57-85.Oxford, R. L. (Ed.). (1996). Language learning motivation: pathways to the new century.Hono lulu: Second Language Teaching & Curriculum Center, University of Hawai’i.Oxford, R., & Shearin, J. (1994). Language learning motivation: Expanding the theoretical framework. Modern Language Journal, 78, 12-28.Papadimitriou, A. D. (2011). The impact of an extensive reading programme on vocabulary development and motivation. Cambridge ESOL Research Notes, 44, 39-47.Paris, S. C., & Turner, J. C. (1994). Situated motivation. In P. R. Pintrich, D. R. Brown, & C. E.Weinstein (Eds.), Student motivation, cognition, and learning (pp. 213-237). Hillsdale,NJ: Erlbaum.Peacock, M. (1997). The effect of authentic materials on the motivation of EFL learners. ELT Journal, 51(2), 144-156.Pedraza, P., & Ayala, J. (1996). Motivation as an emergent issue in an after-school program in El Barrio. In L. Schauble & R. Glaser (Eds.), Innovations in learning (pp. 75-91). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.Pintrich, P. R. (1999). The role of motivation in promoting and sustaining self-regulated learning.International Journal of Educational Research, 31(6), 459-470.Pintrich, P. R., & De Groot, E. V. (1990). Motivational and self-regulated learning components of classroom academic performance. Journal of educational psychology, 82(1), 33.Pintrich, P. R., & Schunk, D. H. (1996). Motivation in education: Theory, research and applications. Englewood Cliffs: NJ: Prentice-Hall.Ramage, K. (1991). Motivational factors and persistence in second language learning. Language Learning, 40(2), 189-219.Rueda, R., & Moll, L. (1994). A sociocultural perspective on motivation. In H. F. O’Neill & M.Drillings (Eds.), Motivation: theory and research (pp. 117-137). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology,25, 54-67.Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55, 68-78. Schmidt, R., Boraie, D., & Kassabgy, O. (1996). Foreign language motivation: Internal structure and external connections. In R. Oxford (Ed.), Language learning motivation:Pathways to the new century (pp. 9-70). Honolulu: Second Language Teaching &Curriculum Center, University of Hawaii Press.Schutz, P. A. (1994). Goals as the transaction point between motivation and cognition. In P. R.Pintrich, D. R. Brown, & C. E. Weinstein (Eds.), Student motivation, cognition, andlearning (pp. 135-156). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.Scott, K. (2006). Gender differences in motivation to learn French. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 62, 401-422.Syed, Z. (2001). Notions of self in foreign language learning: A qualitative analysis. In Z.Dörnyei & R. Schmidt (Eds.), Motivation and second language acquisition (pp. 127-147).Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press.Schmidt, R., Boraie, D., & Kassabgy, O. (1996). Foreign language motivation: Internal structure and external connections. In R. Oxford (Ed.), Language learning motivation: Pathways to the new century (pp. 9-70). Honolulu, HI: Second Language Teaching & Curriculum Center, University of Hawaii Press.Scott, K. (2006). Gender differences in motivation to learn French. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 62, 401-422.Sisamakis, M. (2010). The motivational potential of the European language portfolio. In B.O’Rourke & L. Carson (Eds.), Language learner autonomy: Policy, curriculum,classroom (pp. 351-371). Oxford, UK: Peter Lang.Smith, K. (2006). Motivating students through assessment. In R. Wilkinson, V. Zegers, & C. van Leeuwen (Eds.), Bridging the assessment gap in English-medium higher education (pp.109-121). Nijmegen, The Netherlands: AKS –Verlag.St. John, J. (2007). Motivation: The teachers’ perspective. In S. Midraj, A. Jendli, & A. Sellami (Eds.), Research in ELT contexts (pp. 63-84). Dubai: TESOL Arabia.Syed, Z. (2001). Notions of self in foreign language learning: a qualitative analysis. In Z.Dörnyei & R. Schmidt, (Eds.), Motivation and second language acquisition (pp. 127-148).Honolulu: National Foreign Language Resource Center/ University of Hawai'iPress.Ushioda, E. (2003). Motivation as a socially mediated process. In D. Little, J. Ridley, & E.Ushioda (Eds.), Learner autonomy in the language classroom (pp. 90-102). Dublin,Ireland: Authentik.Ushioda, E. (2008). Motivation and good language learners. In C. Griffiths (Ed.), Lessons from good language learners (pp. 19-34). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Ushioda, E. (2009). A person-in-context relational view of emergent motivation, self and identity.In Z. Dörnyei & E. Ushioda (Eds.), Motivation, language identity and the L2 self (pp.215-228). Tonawanda, NY: Multilingual Matters.Ushioda, E. (2012). Motivation. In A. Burns & J. C. Richards (Eds.), The Cambridge guide to pedagogy and practice in language teahcing (pp. 77-85). Cambridge, UK: CambridgeUniversity Press.Verhoeven, L., & Snow, C. E. (Eds.). (2001). Literacy and motivation: Reading engagement in individuals and groups. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.Wachob, P. (2006). Methods and materials for motivation and learner autonomy. Reflections on English Language Teaching, 5(1), 93-122.Walker, C. J., & Quinn, J. W. (1996). Fostering instructional vitality and motivation. In R. J.Menges and associates, Teaching on solid ground (pp. 315-336). San Francisco, SF:Jossey-Bass.Warden, C. A., & Lin, H. J. (2000). Existence of integrative motivation in an Asian EFL setting.Foreign Language Annals, 33, 535-547.Weiner, B. (1984). Principles for a theory of student motivation and their application within an attributional framework. In R. Ames & C. Ames (Eds.), Research on motivation ineducation (pp. 15-38). New York: Academic Press.Weiner, B. (1992). Human motivation: Metaphors, theories and research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.Weiner, B. (1994). Integrating social and personal theories of achievement motivation. Review of Educational Research, 64, 557-573.Williams, M., Burden, R., & Lanvers, U. (2002). French is the language of love and stuff: Student perceptions of issues related to motivation in learning a foreign language.British Educational Research Journal, 28, 503–528.Wlodkowski, R. J. (1985). Enhancing adult motivation to learn. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Wu, X. (2003). Intrinsic motivation and young language learners: The impact of the classroom environment. System, 31, 501-517.Xu, H., & Jiang, X. (2004). Achievement motivation, attributional beliefs, and EFL learning strategy use in China. Asian Journal of English Language Teaching, 14, 65-87.Yung, K. W. H. (2103). Bridging the gap: Motivation in year one EAP classrooms. Hong Kong Journal of Applied Linguistics, 14(2), 83-95.。

地球上的星星的观后感英文

地球上的星星的观后感英文 Reflections on "Taare Zameen Par" "Taare Zameen Par," a heartfelt Indian film directed by Aamir Khan, tells a compelling story of a young boy named Ishaan who struggles with dyslexia. The film, which translates to "Stars on Earth," explores themes of understanding, acceptance, and the transformative power of compassion. As the credits rolled, I found myself deeply moved by the film's honest portrayal of a child's struggle and the importance of recognizing and addressing individual differences.

What struck me most about "Taare Zameen Par" was its authenticity. The film did not romanticize or simplify Ishaan's challenges; instead, it presented them with raw honesty. The scenes where Ishaan struggled to read and write were particularly poignant, as they reminded me of the frustration and helplessness that children with learning disabilities and their families often face. The film's refusal to sugarcoat this aspect was a breath of fresh air, as it emphasized the importance of acknowledging and addressing such issues.

发展与教育心理学外文杂志详单

MONOGRAPHS OF THE SOCIETY FOR RESEARCH IN CHILD DEVELOPMENT JOURNAL OF CHILD PSYCHOLOGY AND PSYCHIATRYJOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF CHILD AND ADOLESCENT PSYCHIATRY DEVELOPMENT AND PSYCHOPATHOLOGYKINDHEIT UND ENTWICKLUNGDEVELOPMENTAL SCIENCECHILD DEVELOPMENTDEVELOPMENTAL PSYCHOLOGYDEVELOPMENTAL REVIEWJOURNAL OF ADOLESCENT HEALTHJOURNAL OF AUTISM AND DEVELOPMENTAL DISORDERSJOURNAL OF PEDIATRIC PSYCHOLOGYJOURNAL OF ABNORMAL CHILD PSYCHOLOGYJOURNAL OF CLINICAL CHILD AND ADOLESCENT PSYCHOLOGYPSYCHOLOGY AND AGINGAUTISMDEVELOPMENTAL NEUROPSYCHOLOGYResearch in Autism Spectrum DisordersJOURNAL OF DEVELOPMENTAL AND BEHA VIORAL PEDIATRICSJOURNAL OF EXPERIMENTAL CHILD PSYCHOLOGYEARL Y CHILDHOOD RESEARCH QUARTERL YJOURNAL OF ADOLESCENCESOCIAL DEVELOPMENTCOGNITIVE DEVELOPMENTJOURNAL OF RESEARCH ON ADOLESCENCEJournal of Cognition and DevelopmentEUROPEAN CHILD & ADOLESCENT PSYCHIATRYCHILD PSYCHIATRY & HUMAN DEVELOPMENTAdvances in Child Development and BehaviorBRITISH JOURNAL OF DEVELOPMENTAL PSYCHOLOGYINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF BEHA VIORAL DEVELOPMENTJOURNAL OF ADOLESCENT RESEARCHJOURNAL OF YOUTH AND ADOLESCENCEINFANCYAutism ResearchATTACHMENT & HUMAN DEVELOPMENTINFANT BEHA VIOR & DEVELOPMENTChild Development PerspectivesJOURNAL OF EARL Y ADOLESCENCEMERRILL-PALMER QUARTERL Y-JOURNAL OF DEVELOPMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY AGING NEUROPSYCHOLOGY AND COGNITIONJOURNAL OF APPLIED DEVELOPMENTAL PSYCHOLOGYCHILD CARE HEALTH AND DEVELOPMENTINFANT MENTAL HEALTH JOURNALJOURNAL OF CHILD LANGUAGEEuropean Journal of Developmental PsychologyHUMAN DEVELOPMENTSEX ROLESINFANT AND CHILD DEVELOPMENTParenting-Science and PracticeADOLESCENCEJOURNAL OF GENETIC PSYCHOLOGYPRAXIS DER KINDERPSYCHOLOGIE UND KINDERPSYCHIATRIE Applied Developmental ScienceINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF AGING & HUMAN DEVELOPMENT Infanciay AprendizajeINFANTS AND YOUNG CHILDRENJOURNAL OF ADULT DEVELOPMENTJOURNAL OF CONSTRUCTIVIST PSYCHOLOGYCHILD DEVELOPMENTEDUCA TIONAL PSYCHOLOGY REVIEWEDUCA TIONAL PSYCHOLOGISTJOURNAL OF EDUCA TIONAL PSYCHOLOGYLEARNING AND INSTRUCTIONJOURNAL OF SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGYJOURNAL OF COUNSELING PSYCHOLOGYSCHOOL PSYCHOLOGY REVIEWJOURNAL OF THE LEARNING SCIENCESJOURNAL OF EMOTIONAL AND BEHA VIORAL DISORDERSBRITISH JOURNAL OF EDUCATIONAL PSYCHOLOGYREADING RESEARCH QUARTERL YLEARNING AND INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCESINSTRUCTIONAL SCIENCECOGNITION AND INSTRUCTIONDYSLEXIAJOURNAL OF RESEARCH IN READINGJOURNAL OF EARL Y INTERVENTIONCONTEMPORARY EDUCATIONAL PSYCHOLOGYJOURNAL OF APPLIED RESEARCH IN INTELLECTUAL DISABILITIES JOURNAL OF EXPERIMENTAL EDUCA TIONSCHOOL PSYCHOLOGY QUARTERL YPSYCHOLOGY IN THE SCHOOLSDISCOURSE PROCESSESZEITSCHRIFT FUR PADAGOGISCHE PSYCHOLOGIEREADING AND WRITINGJOURNAL OF EDUCA TIONAL MEASUREMENTJOURNAL OF EDUCA TIONAL AND PSYCHOLOGICAL CONSULTATIONJOURNAL OF LITERACY RESEARCHEducational PsychologyJOURNAL OF PSYCHOEDUCATIONAL ASSESSMENTAPPLIED MEASUREMENT IN EDUCATIONEDUCA TIONAL AND PSYCHOLOGICAL MEASUREMENTZEITSCHRIFT FUR ENTWICKLUNGSPSYCHOLOGIE UND PADAGOGISCHE PSYCHOLOGIEEUROPEAN JOURNAL OF PSYCHOLOGY OF EDUCATIONPSYCHOLOGIE IN ERZIEHUNG UND UNTERRICHTMEASUREMENT AND EV ALUATION IN COUNSELING AND DEVELOPMENT CREATIVITY RESEARCH JOURNALSCHOOL PSYCHOLOGY INTERNATIONALInfancia y AprendizajeRevista de PsicodidacticaJOURNAL OF CREATIVE BEHA VIORJAPANESE JOURNAL OF EDUCA TIONAL PSYCHOLOGYVOPROSY PSIKHOLOGII。

Children with Specific Learning Disabilities Who are they & what do they need

• Each dyslexic individual has different strengths and weaknesses • They may have additional problems e.g. attentional deficit, which is not a SLD • Often other members of the family have dyslexia or similar difficulties

Hale Waihona Puke • Dyslexia involves difficulty with LANGUAGE • Intelligence is not the problem • There is an expected GAP between their potential for learning and their school achievement

Basic Facts

• SLD is a group of disorders affecting listening, speaking, reading, writing reasoning or mathematical abilities. • Dyslexia is the most common in the group and most serious in its effects on the student

• Program should have: – direct instruction in area of deficit – multi-sensory approach to learning – systematic step-by-step teaching – appropriate accommodations

简要讨论影响第二语言的个体因素英语作文

简要讨论影响第二语言的个体因素英语作文introductionSince the 1950s, the role of learners' individual differences in second language acquisition has been widely concerned about the outline of graduation thesis, and the study of learners' individual differences has also become one of the main lines of second language acquisition research. According to the consensus of many scholars, these individual differences include the following aspects: 1) views and views on how to learn a foreign language; 2) Mental and psychological state; 3) Age factor; 4) Learning motivation; 5) Language ability tendency; 6) Cognitive style 7) personality factors. This paper mainly discusses the influence of the last four individual differences on second language acquisition.The influence of motivational factors on second language acquisitionMotivation refers to those thoughts, desires, ideals and other factors that can arouse and maintain a person's activities and guide the activities to a certain goal to meet an individual's needs. It canbe divided into the following types:1. Intrinsic motivation refers to the satisfaction that foreign language learners get from learning itself. Maintaining a harmonious relationship between teachers and students is the key to maintaining students' interests.2. The outline of the graduation thesis of result motivation refers to the satisfaction that foreign language learners obtain due to their good academic performance and sense of achievement. Motivation and academic performance complement each other.3. Comprehensive motivation refers to the fact that foreign language learners have a strong interest in the native language and its culture, so as to achieve the purpose of communicating with them and even integrating into the social culture.4. Instrumental motivation the graduation thesis outline is the condition that foreign language learners are not interested in the foreign language itself or anxious with native speakers. Learning foreign language knowledge as a means or tool to achieve other purposes, such as finding a job, reading the original newspaper or passing the exam, and so on. Such motivation becomes instrumentalmotivation.The influence of language learning ability on second language acquisitionLanguage ability tendency refers to a natural language learning ability possessed by foreign language learners, that is, it is a potential ability that may be developed. It is generally believed that the tendency of language ability is mainly reflected in four aspects.1. Language decoding ability, that is, the ability to distinguish and memorize foreign language phonemes.2. Grammatical decoding ability, also known as grammatical sensitivity by some scholars, mainly refers to learners' ability to distinguish the grammatical functions of each word in a sentence.3. Inductive learning ability refers to the ability of foreign language learners to identify the corresponding relationship between language form and meaning.4. The graduation thesis outline of mechanical learning ability generally refers to the study that lacks practice materials or the meaning connection of materials, that is, the study that is usually said to be simple repetition and rote learning.The influence of cognitive style on second language acquisition Cognitive style. It refers to the persistent and consistent unique style of individuals in the process of information processing in terms of human organization and cognitive function. Individual branching style is mainly manifested in the following aspects: field dependence and field independence; Analytical and non analytical conceptualization tendency; The choice of the width of cognitive field; Complex cognition and simple cognition; Adventure and conservatism.People who think that they belong to a continuum often share and make more use of internal reference signs to actively process external information throughout the year. This kind of people is called field independent people; People on the other side tend to make more use of external reference marks and less actively process graduation thesis outlines with external information. This kind of people are called field dependent people who download free papers. There is no consensus on the merits of the two cognitive styles in foreign language learning.The influence of personality factors on second languageacquisitionAmong personality factors, such as self-esteem, inhibition, anxiety, adventurous spirit and internal and external tendencies will have a certain impact on second language acquisition, which will make differences in learning speed and final foreign language level.epilogueIn the process of second language acquisition, individual differences have a great impact on learners' second language families. However, as far as the current research results are concerned, we still cannot explain which individual differences play a crucial role in the success of second language acquisition. In addition, we should also recognize that in addition to individual differences, society, foreign language acquisition mechanism, cultural background, learning atmosphere and environment also have a great impact on learners' second language acquisition. The individual difference factors we studied are only the influence。

发表personality and individual differences

发表personality and individual differences

《Personality and Individual Differences》是一本致力于研究个性和个体差异领域的国际性学术期刊。

该期刊发表有关个性心理学、心理测量学、社会心理学、认知心理学、发展心理学、情绪心理学等领域的原创研究论文、综述文章以及实证研究报告。

以下是一篇发表在该期刊上的论文示例:

标题:五大人格特质与心理幸福感的关系研究

摘要:本研究旨在探讨五大人格特质(外向性、宜人性、责任心、神经质和精神质)与心理幸福感之间的关系。

通过对我国XX省市的XX 名成年参与者进行问卷调查,收集个体的人格特质和心理幸福感数据,采用皮尔逊相关分析和结构方程模型进行分析。

结果表明:外向性、宜人性、责任心与心理幸福感呈正相关,神经质和精神质与心理幸福感呈负相关。

此外,责任心对心理幸福感的影响最大,外向性和宜人性次之。

这些结果揭示了人格特质在心理幸福感中的重要作用,为提高个体心理幸福感提供了理论依据。

关键词:五大人格特质;心理幸福感;人格心理学;个体差异;心理健康

需要注意的是,上述示例仅为论文发表的一个参考范例。

在实际撰写过程中,请务必遵循《Personality and Individual Differences》期刊的投稿要求,包括格式、引用规范等方面。

如有需要,您可以查阅该期刊官方网站或联系编辑获取详细信息。

祝您论文发表顺利!。

三年级英语随班就读学生个别化教学计划

三年级英语随班就读学生个别化教学计划全文共3篇示例,供读者参考篇1Individualized Teaching Plan for Third Grade English In-Class Visiting StudentsIntroductionIn a diverse classroom setting, catering to the individual needs of each student is essential to ensure their academic success. This individualized teaching plan is designed forthird-grade English in-class visiting students who require specific attention and support in order to improve their language skills.Goals and ObjectivesThe main goal of this individualized teaching plan is to enhance the English language proficiency of the visiting students by addressing their unique learning needs. The objectives include:1. Improving reading comprehension skills through guided reading activities tailored to the students' reading levels.2. Enhancing vocabulary acquisition through interactive word games and exercises.3. Developing writing skills through structured writing assignments and creative writing prompts.4. Improving speaking and listening skills through group discussions, role-playing activities, and listening comprehension exercises.5. Providing additional support for grammar and syntax through targeted lessons and practice activities.Assessment and EvaluationTo monitor the progress of the visiting students, regular assessments will be conducted to evaluate their language proficiency and identify areas for improvement. Formative assessments, such as quizzes, tests, and classroom observations, will be used to assess the students' understanding of the material taught in class. Summative assessments, such as standardized tests or final projects, will be used to evaluate the overall progress of the students throughout the academic year.Instructional StrategiesThe individualized teaching plan will incorporate a variety of instructional strategies to meet the diverse needs of the visiting students. These strategies include:1. Differentiated Instruction: Tailoring instruction to meet the individual learning styles and preferences of the students.2. Small Group Instruction: Providing additional support and guidance through small group activities and discussions.3. Peer Tutoring: Pairing the visiting students with native English speakers to enhance their language skills through peer collaboration.4. Technology Integration: Incorporating technology tools, such as educational apps and online resources, to supplement classroom instruction and provide additional practice opportunities.Support ServicesIn addition to the individualized teaching plan, support services will be provided to assist the visiting students in achieving their academic goals. These services include:1. English Language Development (ELD) Program: Offering specialized English language instruction to improve the students' language skills.2. Academic Counseling: Providing guidance and support to address any academic or personal challenges the students may face.3. Parent Involvement: Engaging parents in the students' learning process and providing resources and strategies for supporting their child's academic success.ConclusionBy implementing this individualized teaching plan forthird-grade English in-class visiting students, we aim to empower these students with the skills and confidence they need to succeed in their academic journey. Through targeted instruction, ongoing assessment, and dedicated support services, we are committed to helping these students reach their full potential and excel in their language learning endeavors.篇2Individualized Teaching Plan for Third Grade English Inclusive Class Students1. IntroductionIn an inclusive classroom setting, it is important to recognize the diverse learning needs of students. This individualizedteaching plan is designed for third-grade students in an inclusive English class, with the goal of providing personalized support and facilitating their learning and development.2. Student ProfileThe students in the third-grade English inclusive class display a range of abilities, interests, and learning styles. Some students may have special educational needs, such as dyslexia, ADHD, or autism, while others may be English language learners or gifted learners. It is essential to consider these individual differences when planning instruction and support.3. Goals and ObjectivesThe overarching goal of this individualized teaching plan is to promote academic achievement, social-emotional development, and self-confidence in all students. Specific objectives include:- Enhancing reading, writing, speaking, and listening skills- Building vocabulary, grammar, and comprehension skills- Fostering effective communication and collaboration- Encouraging creativity, critical thinking, andproblem-solving- Developing self-regulation, resilience, and a growth mindset4. Instructional StrategiesTo address the diverse learning needs of students, a variety of instructional strategies will be used, including:- Differentiated instruction: Providing varied learning activities, materials, and assessments to meet individual needs- Multisensory learning: Incorporating visual, auditory, kinesthetic, and tactile elements into lessons- Collaborative learning: Facilitating group work, peer tutoring, and cooperative projects- Technology integration: Using educational apps, websites, videos, and games to enhance learning- Positive reinforcement: Recognizing and rewarding student progress, effort, and achievement5. Accommodations and ModificationsAccommodations and modifications will be made as needed to ensure that all students can access and engage in the curriculum. Some examples include:- Providing extra time for assignments and assessments- Offering alternative formats for materials (e.g., audio books, graphic organizers)- Simplifying instructions and tasks for students with learning difficulties- Using visual supports and cues to aid comprehension and retention- Allowing for flexibility in seating arrangements, groupings, and routines6. Support ServicesIn addition to classroom instruction, students may receive support from various professionals and resources, including:- Special education teachers: Providing individualized instruction and support for students with disabilities- Speech-language pathologists: Addressing speech, language, and communication disorders- School psychologists: Conducting assessments, counseling, and behavior interventions- ELL specialists: Offering English language learning instruction and support- Occupational therapists: Addressing fine motor skills, sensory processing, and self-regulation7. Progress MonitoringProgress monitoring is essential to track student growth, identify areas of need, and evaluate the effectiveness of interventions. Formative and summative assessments will be used to measure student performance, set goals, and make data-driven decisions. Parent-teacher conferences, progress reports, and IEP meetings will also be held to communicate student progress and collaborate on next steps.8. ConclusionIn conclusion, this individualized teaching plan aims to create a supportive and inclusive learning environment for third-grade English students. By recognizing and addressing the diverse needs of students, we can foster their academic success, social-emotional well-being, and overall development. Through personalized instruction, collaboration, and support, all students can thrive and reach their full potential in the inclusive classroom.篇3Individualized Teaching Plan for 3rd Grade English In-Class Reading StudentsIntroductionIn a typical 3rd grade English classroom, students come from diverse backgrounds and have varying levels of English proficiency. Therefore, it is essential to implement individualized teaching strategies to cater to the unique needs of each student. This document outlines a personalized teaching plan for in-class reading students in the 3rd grade, focusing on improving reading skills, vocabulary, and comprehension through differentiated instruction.Student ProfileJohn is a 3rd grade student with average English proficiency. He struggles with reading fluency, vocabulary retention, and comprehension. However, he is motivated to learn and shows a keen interest in reading. John's learning style is kinesthetic, and he prefers hands-on activities to enhance his understanding of English language concepts.Goals- Improve reading fluency by practicing sight words and phonics.- Expand vocabulary through engaging activities and exercises.- Enhance reading comprehension by analyzing texts and answering questions.Teaching Strategies1. Phonics and Sight Words PracticeTo improve John's reading fluency, daily phonics and sight words practice will be incorporated into the lesson plan. Interactive games, flashcards, and worksheets will be used to reinforce phonics rules and increase John's sight word recognition. Additionally, guided reading sessions will focus on decoding skills to help John read independently.2. Vocabulary Building ActivitiesTo expand John's vocabulary, word walls, vocabulary journals, and word study activities will be utilized. Weekly vocabulary lists will be introduced, and John will be encouraged to use new words in context. Hands-on vocabulary activities such as word sorts, matching games, and crossword puzzles will be incorporated to make learning enjoyable and memorable.3. Reading Comprehension StrategiesTo enhance John's reading comprehension skills, strategic reading practices will be implemented. Before reading a text, pre-reading activities such as predicting, questioning, and activating prior knowledge will be used to engage John's curiosity. During reading, strategies like visualizing, summarizing, and making connections will be encouraged to deepen John's understanding of the text. After reading, comprehension questions and discussions will be conducted to assess John's comprehension and critical thinking skills.4. Differentiated InstructionTo accommodate John's kinesthetic learning style, differentiated instruction will be implemented. Hands-on activities, interactive games, and manipulatives will be integrated into the lesson plan to cater to John's preferred learning modality. Furthermore, small group instruction and one-on-one support will be provided to address John's individual learning needs and reinforce learning objectives.Assessment and Progress MonitoringFormative assessments such as reading quizzes, vocabulary tests, and comprehension activities will be used to gauge John'sprogress and identify areas for improvement. Additionally, regular feedback and conferences with John will be conducted to reflect on his learning achievements and set new goals. Progress monitoring will be ongoing to track John's development and adjust teaching strategies accordingly.ConclusionIn conclusion, implementing an individualized teaching plan for 3rd grade English in-class reading students is essential to foster academic growth and enhance learning outcomes. By tailoring instruction to meet the unique needs of each student, we can create a supportive learning environment that promotes student engagement, motivation, and success. Through targeted interventions and differentiated instruction, we can empower students like John to reach their full potential and become proficient readers and lifelong learners.。

Individual Differences in Language Leanrning

2362019年43期总第483期语言文化研究ENGLISH ON CAMPUSIndividual Differences in Language Leanrning文/严瑞清【Abstract】 When talking about language learning and teaching, teachers usually pay more attention to knowledge, skills, learning strategy, cultural awareness and affection, actually indidual differences should also be attached more improtance to in the application to language teaching because different personalities have differentinfluence upon L2 learning.【Key words】 language learning; indidual differnces; application 【作者简介】严瑞清,包头师范学院外国语学院。

is divided into intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, the formerrefers to behaviors aiming at bringing about certain internallyrewarding consequences, namely, feelings of competence and self-determination (Deci, 1975, 23 in Brown, 2000, 164), while the latter refers to behaviors carried out in anticipation of areward from outside and beyond the self (Brown, 2000, 164).6. Application in L2 teachingIt is very difficult to teach L2 successfully because thereare so many factors which have great influence on students’learning. Language teachers should think of various ways to teach students, e.g. group work, because based on thedefinitions given above, the extroverted are usually considered as the talkative, outgoing, and active participants in different activities, esp. in language learning. They show more confidence in speaking activities and are keen on interactingwith others. Their communicative ability in L2 learning is better than the introverted. While the introverted students’ patience and carefulness contribute a lot to their language learning because they can express their ideas in exact words andhave a good skill of reading and writing. So, to some extent, introversion is superior to extroversion, so in group work they can help each other.Each individual has different motivation to learn secondlanguage. For instance, in China, most of the students learn English for various entrance examination. This motivationforces them to make their effort to language learning. So,language teachers should think of ways to sustain their intrinsic motivation to the success of L2 learning.7. ConclusionI have analyzed the factors influencing the differencebetween individuals: personality, motivation, I hope that language teachers can take the advantage of the strong points to teach L2 successfully.References:[1]Brown, H. D. 2000. Principles of language learning and teaching. 4th Edition. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall Inc.1. IntroductionDifferent personalities have different influence upon L2 learning, and language teachers should encourage students to learn L2 because they have different motivation. Both students and teachers should show empathy to other people and other cultures because of the difference between people andculture. Then the application of these factors in L2 teachingwill be discussed.2. Personality factors in Language learningPersonality refers to ‘the aspects of an individual’sbehaviors, attitudes, beliefs, thoughts, actions, and feelings which are regarded as typical and distinctive of that personand recognized as such by that person and others’ (Richard, Platt & Platt, 1992, 271). Personality development usually involves the growth of a person’s concept of self, acceptance of self, and reflection of selves as seen in the interaction between self and others. So there are many different factorswithin a person influencing the success of language learning.3. Extroversion and IntroversionExtroversion means a person whose conscious interestsand energies are more often directed outwards towards otherpeople and events than towards the persons themselves and their own inner experiences (Richard, et al, 1992, 134). And according to Brown (2000, 155), extroversion refers to a person who has a deep-seated need to reach ego enhancement, self-esteem, and a sense of wholeness from other people asopposed to receiving that affirmation within oneself.4. EmpathyEmpathy is the major personality factor with the qualityof being able to imagine and share the thought, feelings,and opinions of others in the harmonious coexistence of individuals in society. In other words, empathy is the process of ‘putting yourself into someone else’s shoes’, of reaching beyond the self to understand what another person isfeeling (Brown, 2000, 153).5. MotivationMotivation, the factor that determines to one’s desireto do something, plays an important part in L2 learning. It。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES IN DYSLEXIAMargaret J. Snowling & Yvonne M. Griffiths1ABSTRACTWith the phonological deficit hypothesis of dyslexia as a back-drop, this reviewdiscusses the issue of how indivdual differences in its behaviouralmanifestation should be conceptualised. It begins by reviewing ways ofclassifying children with dyslexia from a clinical perspective and proceeds todescribe the cognitive neuropsychological approach to classification that hasfocused on the reading and spelling profiles of such children. It argues thatchildren’s reading difficulties should be couched within the framework of typicalreading development and that sub-typing systems that have not acknowledgeddevelopmental data have limitations. An interactive model of learning to read isused to propose that individual differences in dyslexia depend upon the severityof the phonological processing difficulties experienced by an individual child,the proficiency of other cognitive skills and the environment in which they learn.

Key wordsDyslexiasubtypesindividual differences phonological skillsphonological dyslexia surface dyslexia

1 AcknowledgementsThis chapter was prepared with support from Wellcome Trust grant 040195/Z/93/A toMargaret Snowling and a Dyslexia Institute/University of York studentship to Yvonne Griffiths.IntroductionAlthough the first case of unexpected reading difficulty in childhood wasdescribed over a century ago (Morgan, 1896), the definition of dyslexiacontinues to be debated (Lyon, 1995; Stanovich, 1994; Tonnessen, 1997).Dyslexia is commonly defined as a specific difficulty in learning to read, despitenormal IQ and adequate educational opportunity. It is a disorder ofdevelopment that primarily affects the acquisition of literacy and the most widelyaccepted view is that it lies on the continuum of language disorder. Thus,dyslexia is characterised by verbal processing deficits (Vellutino, 1979) and aspecific theory that will be considered here views impairments in phonologicalprocessing to be at its core (Brady & Shankweiler, 1991; Morton & Frith, 1995;Snowling, 1995; Stanovich & Siegel, 1994; see Brady, 1997, for a review).The phonological deficit theory of dyslexia is compelling. First, it is wellgrounded in theory. The strong developmental association betweenphonological skills and learning to read forms a back-drop to much dyslexiaresearch (Goswami & Bryant, 1990; Share, 1995). The theory also makessense of the different manifestations of dyslexia across the age-span from pre-school (Scarborough, 1990) to adulthood (Pennington, van Orden, Smith,Green & Haith, 1990; Paulesu, Snowling, Gallagher, Morton, Frackowiak, & Frith1996). Second, phonological sensitivity shares heritable variance with readingskills (Olson, Wise, Conners, Rack & Fulker, 1989) and importantly, there issubstantial evidence that interventions that enhance phonological skillsfacilitate reading development in dyslexia (Snowling, 1996).The traditional view concerning the mechanisms that account for therelationship between phonology and learning to read is that children who dowell on tests of phonological awareness are quick to understand howphonemes and graphemes relate in the orthography, and to use thisknowledge of letter-to-sound rules as a self-teaching device (Share, 1995).Hence, successful reading depends upon learning explicitly how to assignsounds to letters sequentially, and to blend them to synthesise apronunciation. However, an alternative view (Ehri, 1992; Rack et al, 1992;Laing & Hulme, 1999) argues instead for a direct mapping mechanismaccording to which children at the very earliest stages of learning to read areable to set up direct mappings between orthography and phonology. Accordingto this view, children learn to read by directly mapping sequences of letters totheir pronunciations and not by relying on decoding rules (Marsh. Friedman,Welch & Desberg, 1981).From the cognitive perspective, the phonological deficit theory proposesthat delayed phonological development in dyslexia affects the development ofphonological representations that are the foundation for orthographicdevelopment (Snowling & Hulme, 1994; Metsala, 1997). In turn, awareness ofthe phonological components of spoken words is not available at a time whenthis is critical for the acquisition of reading and spelling skills (Elbro, Borstrom& Petersen, 1998; Fowler, 1991). Typical consequences are a slow rate ofliteracy development, poor generalisation of word reading skills to nonwordreading and poor spelling development (Snowling, 2000 for a review).