TheDemandforDairyProductsinTurkeyTheImpactofHouseholdCompositiononConsumption.doc

高一英语经济学基础单选题30题

高一英语经济学基础单选题30题1. In economics, scarcity refers to the situation where __________.A. resources are unlimitedB. wants are limitedC. resources are limited and wants are unlimitedD. resources and wants are both unlimited答案:C。

选项 A 资源无限是错误的;选项 B 需求有限错误,人的需求往往是无限的;选项C 资源有限而需求无限,符合经济学中稀缺性的定义;选项D 资源和需求都无限错误。

2. The opportunity cost of a decision is __________.A. the cost of the next best alternative forgoneB. the total cost of all alternativesC. the cost of the chosen alternativeD. zero if the decision is a good one答案:A。

选项B 所有选择的总成本错误;选项C 所选择方案的成本不是机会成本的定义;选项D 如果决策好机会成本为零错误。

机会成本是指做出一个决策而放弃的下一个最好的替代方案的成本。

3. Which of the following is an example of a capital good?A. A loaf of breadB. A computer used by a businessC. A pair of shoesD. A bag of apples答案:B。

选项A 一条面包是消费品;选项C 一双鞋是消费品;选项 D 一袋苹果是消费品。

而选项 B 企业使用的电脑是资本品,用于生产其他商品和服务。

高三英语经济术语单选题50题

高三英语经济术语单选题50题1. In a market economy, the law of supply and demand determines the price of goods. When the demand for a product increases and the supply remains the same, the price will _.A. fallB. riseC. remain stableD. fluctuate答案:B。

本题主要考查供求定律。

需求增加而供给不变时,价格会上升,B 选项正确。

A 选项fall 下降不符合;C 选项remain stable 保持稳定也不符合;D 选项fluctuate 波动不准确。

2. The government often uses _ policies to stimulate economic growth.A. fiscalB. monetaryC. tradeD. all of the above答案:D。

fiscal 财政政策,monetary 货币政策,trade 贸易政策,政府通常会使用以上所有政策来刺激经济增长,所以选D。

3. _ is a measure of the general level of prices in an economy.A. InflationB. DeflationC. UnemploymentD. GDP答案:A。

Inflation 通货膨胀是衡量一个经济体中总体价格水平的指标,A 选项正确。

B 选项Deflation 通货紧缩不符合;C 选项Unemployment 失业与价格水平无关;D 选项GDP 国内生产总值也不是价格水平的指标。

4. A _ is a market in which there are many buyers and sellers of a homogeneous product.A. monopolyB. oligopolyC. perfect competitionD. monopolistic competition答案:C。

高二英语经济学概念练习题20题

高二英语经济学概念练习题20题1.In a market economy, resources are allocated mainly through_____.ernment planningB.market forcesC.charitable donationsD.random chance答案:B。

在市场经济中,资源主要是通过市场力量来分配的。

选项 A 政府规划在计划经济中起主要作用;选项 C 慈善捐赠不是资源分配的主要方式;选项D 随机机会不是市场经济资源分配的主要方式。

2.The law of supply and demand is a fundamental concept in_____.A.physicsB.economicsC.historyD.literature答案:B。

供求定律是经济学中的一个基本概念。

选项A 物理学中没有供求定律;选项 C 历史中没有这个概念;选项 D 文学中也没有供求定律。

3.An increase in the price of a good will generally lead to_____.A.an increase in demandB.a decrease in demandC.an increase in supplyD.no change in either demand or supply答案:B。

一种商品价格的上涨通常会导致需求下降。

价格上升,消费者购买意愿降低,需求减少。

选项 A 价格上涨一般不会导致需求增加;选项C 价格上涨一般会使供给增加,但题干问的是对需求的影响;选项D 价格上涨会对需求或供给有影响。

4.When the price of a substitute good increases, the demand for the original good_____.A.increasesB.decreasesC.remains unchangedD.becomes zero答案:A。

高三英语经济单选题50题

高三英语经济单选题50题1. In the economic field, the term "supply" ______ the amount of a product or service that producers are willing and able to offer.A. refers toB. leads toC. contributes toD. turns to答案:A。

本题考查动词短语辨析。

“refers to”意为“指的是”,在经济领域中,“supply”这个术语指的是生产者愿意并且能够提供的产品或服务的数量,符合语境。

“leads to”意为“导致”;“contributes to”意为“有助于,促成”;“turns to”意为“转向,求助于”,均不符合此处“supply”的意思。

2. The ______ of a company is often determined by its financial performance and market share.A. valueB. costC. priceD. expense答案:A。

本题考查名词辨析。

“value”在此处指公司的价值,公司的价值通常由其财务表现和市场份额决定。

“cost”意为“成本”;“price”意为“价格”;“expense”意为“费用,开支”,这三个词都不符合句子要表达的公司整体的价值的意思。

3. Economic growth ______ an increase in the production of goods and services over time.A. consists ofB. results fromC. depends onD. is made up of答案:A。

本题考查动词短语。

“consists of”表示“由……组成,包括”,经济增长包括随着时间推移商品和服务生产的增加,符合题意。

高三英语经济术语单选题60题(答案解析)

高三英语经济术语单选题60题(答案解析)1.International trade can bring many benefits. One of the main advantages is ________.A.economic growthB.political stabilityC.social equalityD.environmental protection答案:A。

解析:国际贸易主要带来的好处之一是经济增长。

选项 B 政治稳定不是国际贸易的主要直接优势;选项 C 社会平等也并非国际贸易直接带来的主要优势;选项D 环境保护不是国际贸易的主要直接优势。

2.In a market economy, the allocation of resources is mainly determined by ________.ernment planningB.market forcesC.social needsD.public opinion答案:B。

解析:在市场经济中,资源的分配主要由市场力量决定。

选项A 政府规划在计划经济中起主要作用;选项C 社会需求不是决定资源分配的主要因素;选项D 公众舆论对资源分配不起主要作用。

3.The concept of supply and demand is fundamental in ________.A.economicsB.politicsC.sociologyD.history答案:A。

解析:供求概念在经济学中是基础的。

选项B 政治中没有供求概念作为基础;选项C 社会学中也不是以供求概念为基础;选项D 历史中供求概念不是基础。

4.Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is a measure of ________.A.economic outputB.social welfareC.environmental qualityD.political power答案:A。

高二年级英语经济学原理应用单选题60题

高二年级英语经济学原理应用单选题60题1. In a market where the demand for a product suddenly increases while the supply remains the same, what will likely happen to the price?A. It will decreaseB. It will remain unchangedC. It will increaseD. It will fluctuate randomly答案:C。

解析:在供求关系中,当需求增加而供给不变时,根据经济学原理,价格往往会上升。

A选项价格下降不符合这种供求情况;B选项价格不变也是错误的,因为需求增加会给价格带来上升的压力;D选项随机波动不符合基本的供求决定价格的原理。

2. Which market structure is characterized by a single seller with a high degree of control over price?A. Perfect competitionB. MonopolyC. OligopolyD. Monopolistic competition答案:B。

解析:垄断(Monopoly)的特点就是只有一个卖家,这个卖家对价格有高度的控制权。

A选项完全竞争市场有众多卖家,无法单独控制价格;C选项寡头垄断是少数几个卖家,与单一卖家的情况不符;D选项垄断竞争有很多卖家,也不能像垄断企业那样高度控制价格。

3. When the supply of a good is greater than the demand for it, producers usuallyA. raise the priceB. keep the price stableC. lower the priceD. stop production immediately答案:C。

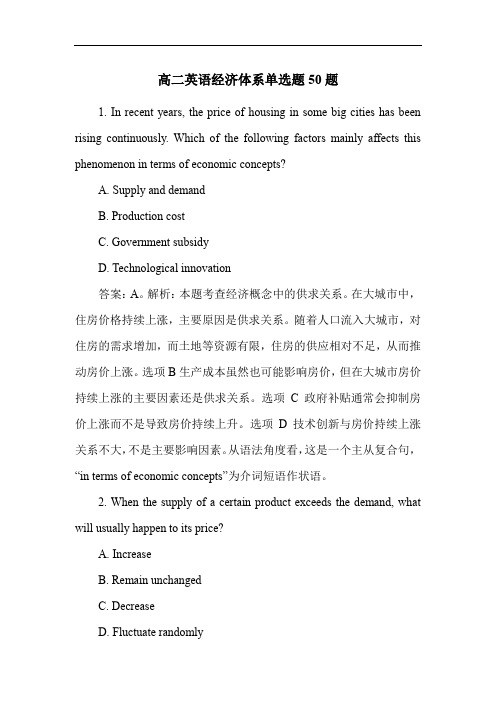

高二英语经济体系单选题50题

高二英语经济体系单选题50题1. In recent years, the price of housing in some big cities has been rising continuously. Which of the following factors mainly affects this phenomenon in terms of economic concepts?A. Supply and demandB. Production costC. Government subsidyD. Technological innovation答案:A。

解析:本题考查经济概念中的供求关系。

在大城市中,住房价格持续上涨,主要原因是供求关系。

随着人口流入大城市,对住房的需求增加,而土地等资源有限,住房的供应相对不足,从而推动房价上涨。

选项B生产成本虽然也可能影响房价,但在大城市房价持续上涨的主要因素还是供求关系。

选项C政府补贴通常会抑制房价上涨而不是导致房价持续上升。

选项D技术创新与房价持续上涨关系不大,不是主要影响因素。

从语法角度看,这是一个主从复合句,“in terms of economic concepts”为介词短语作状语。

2. When the supply of a certain product exceeds the demand, what will usually happen to its price?A. IncreaseB. Remain unchangedC. DecreaseD. Fluctuate randomly答案:C。

解析:本题考查供求关系对价格的影响这一经济概念。

当产品供过于求时,市场上产品数量多于需求数量,为了出售产品,商家往往会降低价格,所以价格通常会下降。

选项A价格增加是供不应求时的情况。

选项B价格保持不变不符合供求关系影响价格的规律。

选项D随机波动不是供过于求时价格的通常走向。

国际贸易实务-双语教案-附术语中英文对译介绍

国际贸易实务教案Chapter 1 Brief Introduction to International Trade国际贸易简介1。

1 Reasons for international trade1.1。

1Resources Reasons(1)Natural resources。

(2) Favorable climate conditions and terrain。

(3)Skilled workers and capital resources。

(4) Favorable geographic location and transportation costs。

1.1.2Economic Reasons(1)Comparative advantage(2)Strong domestic demand(3) Innovation or style1。

1。

3Political Reasons1.2 Problems Concerning International Trade1。

2.1Cultural Problems(1)Language。

(2)Customs and manners。

1.2.2Monetary Conversions1。

2.3Trade BarriersIndividual countries put controls on trade for the following three reasons:(1) To correct a balance—of—payments deficit.(2) For reasons of national security.(3) To protect their own industries against the competition of foreign goods.Although tariffs have been lowered substantially by international agreements, countries continue to use other devices to limit imports or to increase exports。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

The Demand of Dairy Products in Turkey: The Impact of HouseholdComposition on ConsumptionA. Ali KoçResearch ConsultantAgricultural Economics Research Institute Ankara, e-mail: aakoc@Sibel TanAgricultural Economist,Agricultural Economics Research Institute Ankara, e-mail: sibeltan@.trTürkiye’de Süt Ürünleri Talebi:Hanehalkı Nüfus Yapısının Tüketim Üzerine EtkisiÖzetBu çalışmada farklı süt ürünleri için farklı model tanımlanarak (Working-Leser, AIDS ve Çift-Logaritmik fonksiyon) Engel fonksiyonu tahmin edilmiştir. Çalışmada yer alan süt, yoğurt, peynir ve tereyağ için harcama esneklikleri hespalanmıştır. Peynir ve süt için fiyat-talep esneklikleri de tahmin edilmiştir. Çalışma ile hanehalkınüfus yapısının peynir ve süt tüketim üzerine etkisi de belirlenmiştir. Sonuçlar haneye yeni bir birey dahil olduğunda peynir ve süt tüketim harcamasının azalacağını veya negatif etkileneceğini göstermektedir. Bu negatif etki bireyin yaşıile doğru orantılıolarak artmaktadır.AbstractThis study estimates different Engel Curves (in the forms of “Working-Leser”, AIDS with unit value, and Double-Log) for different dairy products in Turkey. Study provides expenditure elasticity for four dairy products (milk, yogurt, cheese and butter). Own-price elasticity is also calculated for cheese and butter. Household composition effects on cheese and milk consumption are determined by the study. Results indicate that addition of an extra person to a household has negative impact on per capita cheese and milk expenditure. This negative impact gets bigger with age.Key Words: Republic of Turkey, Dairy Product Demand, Household Composition Effects, Working-Leser, and AIDS with Unit Value1.IntroductionCommonly used food demand projection method is the synthetic Double-log specification that employs income elasticity and population growth for food demand projection, particularly in developing countries. This method may generate biased food demand projections and policy results, if population composition and other demand shifters (relative commodity price, urbanization, education, etc.) are also changed with rapidly. This is the current trend in Turkey as in many middle income developing countries. On the other hand, intelligent policy design for indirect taxation and subsidies requires knowledge of price and income elasticities for taxable commodities (Deaton, 1988). Such knowledge would normally be obtained by the analysis of time-series data for aggregate demand, prices, and incomes. Unfortunately, in Turkey, as well as in many developing countries, time-series food disappearance data is not readily available to economists or analysts; however, many developing countries regularly collect high-quality household survey data on expenditures and quantities purchased for a wide range of commodities. In principle, these household surveys contain information about the spatial distribution of prices so that, if this information could be recovered in the usable form, there is great potential for estimating the demand responses required for policy making (Deaton, 1988). If unit values, obtained by dividing expenditure by quantity, are adjusted with quality differences, then this data permits the estimation of food demand at disaggregated levels, which is of interest to public policy makers, agribusiness industries, and producer organizations.In Turkey, the State Institute of Statistics (SIS) conducted large-scale household consumption expenditure surveys in 1979, 1987 and 1994. Unfortunately, SIS did not make the survey results available to users at individual household level. The published form of the consumption expenditure survey data is aggregated at income percentiles.This study estimates a household dairy product demand at a disaggregated level with household composition variables and quality adjusted unit values using data from the “1994 Household Consumption Expenditure Survey Results for Selected Province Centers” (SIS, 1997).2. ModelA form of the Engel curve, which has performed well in the empirical analysis of cross-section data, expresses budget share as a function of the logarithm of income (Young and Hamdok, 1994):(1) y W i i i ln βα+=where W i is the budget share of the i th good in full income, and y is the household ’s full income; αi and βi are parameters to be estimated. This form, often known as the “Working-Leser ” curve, is consistent with the Almost Ideal Demand System when prices are constant (Chesher and Rees, 1987).Deaton (1997, p.231);Young and Homdok (1994) introduced household size and household composition by re-defining household income in per capita terms and by re-specifying the intercept term to allow for the influence of household composition as follow: (2) )ln(ln 11n n y n n W i i K k k ik i i δβαα+⎪⎭⎫ ⎝⎛+⎪⎭⎫ ⎝⎛+=∑-=where n denotes household size, and three household member type are distinguished (k=1,2, and 3), n 1 the number of children less than 12 years old, n 2 the number of teenager aged between 12 and 17 years and n 3 the number of adult aged 18 and over; αik βi and δi denote parameters to be estimated. In equation (2), the household composition variables act as explicit demand shifters. Household size (n) enters as a separate explanatory variable (in log form), as well as in per capita income term. This is to ensure that the way in which income affects behaviour is unrestricted (Young and Homdok, 1994). Equation (2) may further be improved by means of introducing price term (here is unit value that is obtained by dividing expenditure by quantity purchased of the goods): (3) *11)ln(ln P n n y n n W i i i K k k ik i i γδβαα++⎪⎭⎫ ⎝⎛+⎪⎭⎫ ⎝⎛+=∑-=where P* is the unit value of the i th good that needs to be adjusted if aggregate quantity of the goods is composed from heterogeneous product.One problem associated with the model described by equation (3) is that the unit value, obtained by dividing expenditure by the quantity purchased, is not a direct substitute for the actual market price. Unit values not only reflect spatial variation in prices due to the transport cost differentials, they also reflect consumer quality choices in their purchases and errors in measuring expenditures and quantities (Deaton, 1988). If unit values are used directly in demand estimation, the price elasticities are not standard elasticities of demand. They also reflect quality elasticities of demand (Theil, 1952; Houthakker, 1952; Cramer, 1973; Cox and Wohlgenant,1986; Deaton, 1987, 1988 and 1990; Nelson, 1991; Park et al., 1996; and Dong et al., 1998).The causes of cross-sectional price variation must be identified in order to interpret correctly the effects of prices in the analysis of household budget data (Prais and Houthakker, 1955, p.110). Polinsky (1977) pointed out that failure to specify cross-sectional price effects adequately could result in biased and misleading demand elasticities. Thus, traditional Engel analysis may be inappropriate if the prices faced by individual consumers are not constant. According to Prais and Houthakker (1955), price variations across regions may be due to price discrimination, services bundled with the commodity, seasonal effects, and quality differences caused by the heterogeneous commodity aggregate.The opportunity costs of consumers' time, the marginal cost/benefit of information search, retailing strategies, and brand loyalty may also cause cross-sectional price differences. Among the above factors, quality differences caused by heterogeneous commodity aggregates may be more problematical in the estimation of demand functions (Cox and Wohlgenant, 1986). Quality effects in cross-sectional price variation result mainly from commodity aggregation (Houthakker, 1952). The potential distortion from not adjusting cross-sectional prices for quality effects will increase with heterogeneity of the commodity aggregate (Cramer, 1973).The simple sum of physical quantities used as the demand in the quality literature is a theoretically arbitrary method of aggregation and is potentially a misleading measure of demand when goods are heterogeneous (Nelson, 1991). According to Nelson, the importance of properly adjusting for quality variation depends on the importance of quality effects in the data under examination.This study adjusts the unit values in terms of income and household size. The unit values of the aggregated commodity are estimated using the following equation (Cox and Wohlgenant, 1986; Park et al., 1996) 1.(4),εδβα+++=n y P i i i u iwhere u iP is unit value of the i th aggregated commodity, y is household full income, and n is the household size. It is commonly assumed that the intercept term of the hedonic price function reflects the quantity price. If we assume the average sample price is the intercept term of the hedonic price function, then the adjusted unit value can be obtained from equation (4).(5)ε+=-P P jIn equation (5)-P is the average sample unit value and ε is residual from equation (4)2.Income and Marshallian price elasticities from the estimates of equation (3) are computed using following formulas (Green and Alston, 1991).Expenditure(6) i i i W βη+=1 Price(7) ⎥⎦⎤⎢⎣⎡-+-=i i i i W βγε)(1As the way in which changes in family composition affect demand is quite complex (the addition of a family member of type j increases n as well as n j ), the parameters in equation (2) are difficult to interpret directly. Following (Chesher, 1991) for each commodity group, the impact on household expenditure of the addition of a household member of type r to the household, “ceteris paribus ”, may be calculated as follows (Young and Hamdok, 1994). 1 Deaton (1990) developed a different methodology to estimate food demand systems with cross-section data. This methodology applies cluster techniques to household data.(8) ⎪⎭⎫ ⎝⎛+--+-+=∆∑n n n n n n n W i i k k ik ik i 1ln )()/()1(11δβααwhere i W ∆ denotes the change in the budget share of good i (or equivalently, the change in expenditure i as a proportion of household income). It measures the “total effect ” of a change of household composition, i.e. the combined impact of the “specific effects ” and “income effect ” referred to above (Young and Hamdok, 1994). An alternative way of presenting this information has been suggested by Deaton (1997, p.235). He sets out a procedure for establishing the “outlay-equivalent ” of adding an extra person to the household, i.e. calculating how much the total budget would have to be changed in order to generate the same additional expenditure on good i as would the addition of one more person of a given type. Specifically, he defines dimensionless outlay equivalent ratios (πir ):(9) y n y E n E i r i ix ∂∂∂∂=//πwhere E i denotes expenditure on good i; by definition y E W ii =. The outlay-equivalent ratios indicate the change in total outlay y that would be equivalent to an additional person of type r, expressed as a ratio of per capita household income. Thus, for example, a value of πir of 0.2, where i denotes milk and n r number of infants, signifies that the addition on an infant to the household has the same effect on milk consumption as an increase of 20% in household expenditure per person (Young and Hamdok 1994). Given estimates of coefficients, the outlay-equivalent ratios can be calculated:(10) i i ki i k ik ir ir W n n +-+-=∑ββδααπ)()/(where, by convention, αik for the last demographic category K is zero.2 Cowling and Rayner (1970) used the error term of the hedonic price function for the proxy of theThe formulae is given by equation (10) can be easily fitted the equation (3) as follows: (11) i i k i i i k ik ir ir W n n +-++-=∑ββγδααπ)()/(3. Data and EstimationThe data for this study was obtained from the 1994 Household Consumption Expenditure Survey Results of the State Institute of Statistics (SIS). SIS provided an electronic copy of the Household Consumption Expenditure Survey Results for 19 Selected Province Centers aggregated into five income percentiles. The 1994 Household Consumption Expenditure Survey Results include both consumption expenditures and quantities purchased for dairy products. The household composition variables used in the model were also provided in the electronic data set at the province and income-percentile level. In this study, expenditures and consumption quantity data are pooled across the 19 provinces and five income percentiles in each province.Unit value and demand estimation that will be presented below are done by OLS with the White correction for heteroskedasticity (Greene, 1997). Heteroskedasticty is a common problem in grouped cross-section data. We have inspected and found out that the estimated variances were not constant across the sample. Since the source of variation was not known, White's procedure was used to correct the covariance matrix for heteroskedasticity in the study.4. ResultsIt is useful to provide some information about dairy consumption in Turkey in order to understand whether the empirical results reasonable. Table 1 presents some information about dairy product consumption according to the geographic base and income percentile. The dairy consumption data show that per capita dairy product consumption varies across income percentile and geographic base. As can be seen quality-adjusted price in their market share model for tractor brands.from Table 1, consumption data suggest that dairy product consumption will be positively related to income growth, but it is inversely related to urbanization.Descriptive statistics of the data used in this study are presented in Table 2. The standard deviations are considerably high for the unit values of cheese and butter. The descriptive statistics also indicate that both per household and per capita dairy product consumption vary across income percentiles and provinces. Dairy product expenditures account for about 4 percent of total income and this share also varies greatly across income percentiles and provinces. The magnitude of the group expenditure share proves that dairy product expenditures are considerably important in household budgets.Table 1. Per capita Annual Dairy Product Consumption (Kg)Income PercentileLower MiddleLower Middle MiddleUpperUpper AverageUrbanMilk 19.13 21.72 27.94 30.90 33.56 26.65 Yogurt 10.92 12.29 11.32 11.84 11.90 11.65 Cheese 5.11 8.40 7.20 7.96 9.69 7.67 Butter 0.51 0.78 0.82 1.24 1.33 0.94 Other Dairy Product 0.40 0.23 0.06 0.82 0.75 0.45 RuralMilk 25.36 27.83 33.55 29.72 32.41 29.78 Yogurt 18.67 20.59 21.76 20.90 21.72 20.73 Cheese 7.63 7.63 8.24 8.76 9.55 8.36 Butter 1.84 2.09 2.63 2.23 2.29 2.22 Other Dairy Product 0.24 0.38 0.11 1.32 3.06 1.02 TurkeyMilk 22.52 25.84 28.76 30.23 33.57 28.18 Yogurt 15.63 16.66 16.47 15.84 15.15 15.95 Cheese 6.36 7.89 7.51 8.39 9.54 7.94 Butter 1.33 1.54 1.59 1.59 1.68 1.54 Other Dairy Product 0.32 0.55 0.10 1.58 1.38 0.78 Source: Authors calculation from SIS 1994 Household Consumption Expenditure Data.Table 2. Descriptive Statistics for DataAverag e StandardDeviationMinimum MaximumUnit Value-Cheese 64.59 11.36 41.90 95.93 -Milk 10.65 1.98 7.98 16.47 -Yogurt 17.00 6.45 6.98 32.07 -Butter 94.97 16.91 56.94 146.86 Per Capita Consumption(Kg /Year)-Cheese 6.95 1.89 1.08 12.43 -Milk 26.18 9.01 6.53 50.34 -Yogurt 10.31 7.49 0.09 47.2 -Butter 1.29 1.32 0.09 6.44Household Size 4.41 0.676 2.74 6.63 Age Distribution (%)0-4 0.093 0.033 0.050 0.296 5-12 0.183 0.032 0.100 0.259 13-17 0.126 0.024 0.071 0.174 18 and + 0.598 0.055 0.545 0.723 Share of Food in Income 0.353 0.143 0.105 0.728 Share of Food in ConsumptionExpenditure0.365 0.085 0.171 0.581Share of Cheese in Income 0.017 0.007 0.003 0.037 Share of Milk in Income 0.010 0.004 0.003 0.020 Share of Yogurt in Income 0.007 0.006 0.00003 0.027 Share of Butter in Income 0.004 0.006 0.00005 0.037Table 3. Unit Value EstimatesCheese ButterConstant 79.76(12.79)88.45 (30.59)Total Household’s Income 0.0026(4.61)0.0023 (2.72)Household Size -5.163(-3.99)R20.31 0.08 Adjusted R20.30 0.07 F Statistics 20.90 8.20 Quality Elasticity with Respect toIncome 0.12 0.07 Household Size -0.35Note: Equation was estimated with White heteroskedasticity correction procedure. In the parenthesis are t values and bold indicates parameters are significant at 1 percent significant level.Table 3 presents unit value estimates for cheese and butter. The estimation results with heteroskedasticity corrected model show that income and household size are very significant variables in explaining the changes in unit values. Coefficient of both of the explanatory variables have the correct and expected sign. The quality elasticity of cheese with respect to household expenditures and size are given at the bottom of the Table 3. The quality elasticity with respect to income is 0.12 for cheese and 0.07 for butter. This means that households in the high-income percentile purchase moreexpensive (reflects quality) cheese and butter than those of in the low-income percentile. The quality elasticity with respect to household size is also significant and has negative impact on cheese quality. The magnitude of this elasticity is –0.35.The parameters of the demand models are given in Table 4. It can be seen from the estimated results that all of the coefficients of the explanatory variables are significant at the 1 or 5 percent level. The R2 of the model is high. In Table 5, the expenditure, price, household size elasticities for the dairy products are presented. Expenditure and own-price elasticities are of expected or reasonable size. Coefficients of composition variables are significant. These variables have negative effects on cheese and milk expenditure. The negative effects of the household composition get bigger as the group gets older. The impact of household size on expenditure is positive in the yogurt and butter demand equation. But, its impact on expenditure is negative in milk demand equation.Table 4. Household Demand Estimation Results for Dairy ProductDependent Variables*Expenditure Share of Ln (Per CapitaConsumption)Cheese Milk Yogurt ButterConstant 0.079(5.91)0.066(17.25)0.0017(0.42)-5.99(-1.93)Ln (Income ) -0.0094(-13.25) -0.0051(-11.65)-0.0058(-7.42)0.336(2.01)Ln (Cheese Unit Value) 0.0050(2.03)Ln (Butter Unit Value) -0.78(-1.57)N2 /Household Size -0.042(-2.61) -0.045 (-3.78)(N1) /Household Size -0.020(-2.15) -0.017 (-2.50)(N2+N3)/Household Size 7.14(2.85)Ln (Household Size) -0.0045(-1.92) 0.0066(2.26)1.03(1.14)R20.74 0.77 0.48 0.27 Adjusted R20.73 0.76 0.47 0.25 F 64.75 77.01 41.43 8.34 **N1 indicates the number of infant in household (aged 0-4), N2 indicates the number of child in household (aged 5-12), N3 indicates the number of teenager in household (aged 13-17), and N4 the number of adults in household (aged 18 and more).*The share of expenditure in the total household income. In the parenthesis are t values and bold indicates parameters are significant at the 5 or 10 percent significant levels.The elasticities are evaluated at the sample mean are presented in the Table 5. All elasticities verify to our expectations in terms of their magnitudes. The size of the income elasticity of yogurt is lower than the other dairy products. This may be result of home production of yogurt in large number of household in Turkey.Table 5. ElasticitiesPrice Expenditure Household Size Cheese -0.69 0.42Milk 0.50Yogurt 0.14 0.97 Butter -0.78 0.35 1.03 Table 6 presents the impact of household composition on the expenditure of cheese and milk. When a new member is added to the household that will have a negative impact on both cheese and milk expenditure. This negative impact gets bigger with age.These results suggest that, ceteris paribus, as the household composition change from children to teenager, cheese and milk expenditure of the household will decline. Of course one cannot expect a decline in all food items or groups. Because, from the standard microeconomics theory, for a given income and price, household needs to re-establish its food diet to maximize utility.Table 6. The Change in Budget Share with the Addition of a New MemberChildren TeenagerCheese -0.006 -0.010 Milk -0.003 -0.008 Note: The numbers are calculated using equation (8).5. ConclusionThis study estimates Engel curves for dairy products with/without adjusted unit values. The hedonic model estimates for unit values are found to be significant for cheese and butter. The study provides income elasticities for cheese, milk, yogurt and butter. Price elasticities are also estimated for cheese and butter. The elasticities provided in this study must be used with caution, because the data employed in the model is aggregated into income percentiles. The Engel curves and hedonic price functions specified in the study can be further improved if SIS provides expenditure and quantity data set for food at the individual household level. This individual household level data will make it possible to estimate Engel functions for different household types (two-adult household, household with one or more child etc.), allowing the measurement of the cost of children.ReferencesChesher, A.D., and Rees, H.J.B. “Income Elasticities of Demands for Food in Great Britain.”Journal of Agricultural Economics, 38(1987):435-448. Chesher, A. D. “Household Composition and Household Food Purchase”. In:MAFF’s Fifty Years of the National Food Survey. 1940-1990. HMSO, London, 1991.Cramer, J. S. "Interaction of Income and Price in Consumer Demand." International Economics Review, 14(1973):351-63.Cowling, K., and A. J. Rayner. "Price, Quality, and Market Share." Journal of Political Economy, 78(1970):1292-1309Cox Thomas L., and Michael K. Wohlgenant. "Prices and Quality Effects in Cross-Section Demand Analysis." American Journal of Agricultural Economics,68(1986):908-19.Deaton, A.” Estimation of Own-and Cross-Price Elasticities from Household Survey Data." Journal of Econometrics, 36 (1987):7-30________."Quality, Quantity, and Spatial Variation of Price." American Economic Review, 78(June 1988):418-30.________."Price Elasticities from Survey Data." Journal of Econometrics, 44(1990):281-308.________.The Analysis of Household Surveys: A Microeconometric Approach to Development Policy. Published for the World Bank, The Johns HopkinsUniversity Press, Baltimore, 1997.Deaton, Angus, and John Muelbauer. Economics and Consumer Behavior.Cambridge:Cambridge University Press, 1980.Dong , Diansheng, J. S. Shonkwiler, and Oral Capps, Jr."Estimation of Demand Function Using Cross-Sectional Household Data: The Problem Revisited."American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 80(1998):466-473Fan, S., E.J. Wailes, G.L. Cramer. "Household Demand in Rural China: A Two-Stage LES-AIDS Model." American Journal of Agricultural Economics,77(1995):54-62.Green, R. and J.M. Alston. "Elasticities in AIDS Models: A Clarification and Extension." American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 73(1991):874-75. Greene, William H. Econometric Analysis. (3rd edition), Upper Saddle River New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1997.Houthakker, Hendrick S. "Compensated Change in Quantities and Qualities Cunsumed." Review of Economic Studies, 19(1952):155-64.Nelson, Julie A. "Quality Variation and Quantity Aggregation in Consumer Demand for Food." American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 73(1991):1204-12. Polinsky, A.M. "The Demand for Housing: A Study in Specification and Grouping."Econometrica, 45(March 1977):447-62Park, J.L., R.B. Holcomb, K.C. Raper, O. Capps, Jr. "A Demand System Analysis of Food Commodities by U.S. Households Segmented by Income." American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 78(1996):290-300.Prais, S. J., and H.J. Houthakker. “The Analysis of Family Budgets. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1955.State Institute of Statistics. "1994 Household Consumption Expenditure Survey: Summary Result of 19 Selected Province Centers." Electronic data setobtained from State Institute of Statistics (SIS), Prime Ministry, Republic ofTurkey, 1997, Ankara.Young, T. and Hamdok, A.A. H.“Effects of household size and composition on consumption in rural household in Matabeleland South, Zimbabwe.”Agricultural Economics, 11(1994):335-343.Theil, Henri. "Qualities, Prices, and Budget Enquries." Review of Economic Studies, 19(1952):129-47.。