The Nature and Role of Norms in Translation 翻译规范

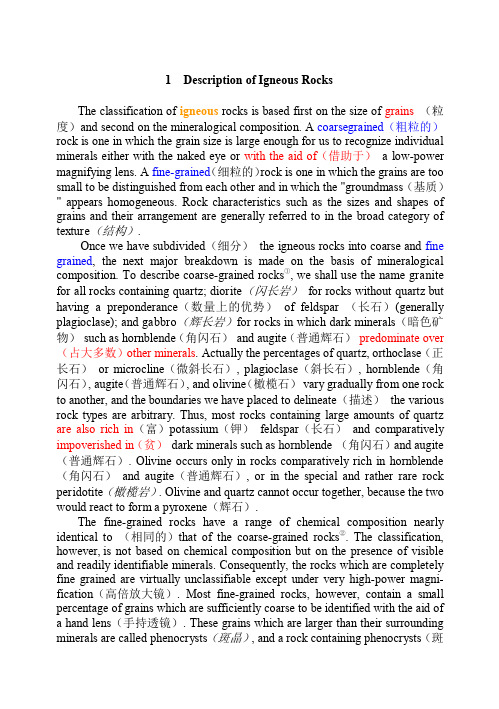

中国地质大学(北京)考博专业英复习材料

晶) is said to have a porphyritic texture(斑状结构). The classification of fine-grained rocks, then, is based on the proportion of minerals which form phenocrysts and these phenocrysts (斑晶)reflect the general composition of the remainder(残留) of the rock. The fine-grained portion of a porphyritic(斑岩) rock is generally referred to as the groundmass(基质) of the phenocrysts. The terms "porphyritic" and "phenocrysts" are not restricted to fine-grained rocks but may also apply to coarse-grained rocks which contain a few crystals distinctly larger than the remainder. The term obsidian(黑曜岩) refers to a glassy rock of rhyolitic(流纹岩) composition. In general, fine-grained rocks consisting of small crystals cannot readily be distinguished from③ glassy rocks in which no crystalline material is present at all. The obsidians, however, are generally easily recognized by their black and highly glossy appearanceass of the same composition as obsidian. Apparently the difference between the modes of formation of obsidian and pumice is that in pumice the entrapped water vapors have been able to escape by a frothing(起泡) process which leaves a network of interconnected pore(气孔) spaces, thus giving the rock a highly porous (多孔的)and open appearance(外观较为松散). ④ Pegmatite(结晶花岗岩) is a rock which is texturally(构造上地) the exact opposite of obsidian. ⑤ Pegmatites are generally formed as dikes associated with major bodies of granite (花岗岩) . They are characterized by extremely large individual crystals (单个晶体) ; in some pegmatites crystals up to several tens of feet in length(宽达几十英尺)have been identified, but the average size is measured in inches (英寸) . Most mineralogical museums contain a large number of spectacular(壮观的) crystals from pegmatites. Peridotite(橄榄岩) is a rock consisting primarily of olivine, though some varieties contain pyroxene(辉石) in addition. It occurs only as coarse-grained intrusives(侵入), and no extrusive(喷出的) rocks of equivalent chemical composition have ever been found. Tuff (凝灰岩)is a rock which is igneous in one sense (在某种意义上) and sedimentary in another⑥. A tuff is a rock formed from pyroclastic (火成碎 屑的)material which has been blown out of a volcano and accumulated on the ground as individual fragments called ash. Two terms(igneous and sedimentary) are useful to refer solely to the composition of igneous rocks regardless of their textures. The term silicic (硅质 的)signifies an abundance of silica-rich(富硅) and light-colored minerals(浅 色矿物), such as quartz, potassium feldspar(钾长石), and sodic plagioclase (钠长石) . The term basic (基性) signifies (意味着) an abundance of dark colored minerals relatively low in silica and high in calcium, iron, and

介绍牛顿的英语作文

Isaac Newton, a towering figure in the history of science, is renowned for his monumental contributions to physics, mathematics, and astronomy. His life and work continue to inspire generations of scholars and laypeople alike. This essay aims to delve into the life of Sir Isaac Newton, exploring his early years, his groundbreaking discoveries, and the impact of his work on the world.Born in Woolsthorpe, England, on January 4, 1643, Newton was a child of the scientific revolution. His early life was marked by a thirst for knowledge and an insatiable curiosity about the world around him. Despite facing numerous challenges, including the early death of his father and a strained relationship with his stepfather, Newtons determination to learn and understand the universe was unwavering.Newtons academic journey began at the University of Cambridge, where he was admitted to Trinity College in 1661. It was here that he was exposed to the works of the great philosophers and scientists of the time, such as René Descartes and Christiaan Huygens. His intellectual curiosity was further fueled by the teachings of Isaac Barrow, a prominent mathematician and the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics, a position Newton would later hold.One of Newtons most significant contributions to science was the development of the laws of motion and universal gravitation. These laws, which he formulated in his seminal work, Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, published in 1687, laid the foundation for classical mechanics. His three laws of motion describe the relationship between abody and the forces acting upon it, and the bodys motion in response to those forces. The law of universal gravitation, on the other hand, posits that every particle in the universe attracts every other particle with a force that is directly proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between their centers.Newtons work in optics was equally groundbreaking. He conducted a series of experiments that demonstrated white light is composed of a spectrum of colors, which he observed by passing sunlight through a prism. This discovery challenged the prevailing theories of the time and laid the groundwork for the field of spectroscopy. Furthermore, Newtons work on the nature of light and color led to the development of the reflecting telescope, which significantly improved upon the existing designs of the time.In addition to his scientific achievements, Newton made significant contributions to the field of mathematics. He developed calculus, a branch of mathematics that deals with the study of change and motion, independently of German mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. Although the two mens work on calculus was developed concurrently, Newtons notation and methods have had a lasting impact on the field.Newtons influence extended beyond the scientific community. His work was instrumental in shaping the Enlightenment, a period of intellectual and philosophical development that emphasized reason, individualism, and the scientific method. His ideas on natural philosophy and the laws governing the universe inspired a new generation of thinkers and scientists, includingVoltaire, who referred to Newton as the great geometer of the universe.Despite his monumental contributions to science, Newtons personal life was marked by periods of intense introspection and solitude. He was known to be somewhat reclusive and had few close friends. His correspondence with other scientists, such as the famous exchange with Leibniz over the invention of calculus, was often marked by a sense of rivalry and competition.In conclusion, Sir Isaac Newtons life and work have left an indelible mark on the world of science and beyond. His discoveries in physics, mathematics, and optics have shaped our understanding of the universe and laid the foundation for much of modern science. His legacy continues to inspire and challenge us to explore the mysteries of the cosmos and to seek a deeper understanding of the world around us.。

the-name-and-nature-of-translation-studies《翻译学的名与实》

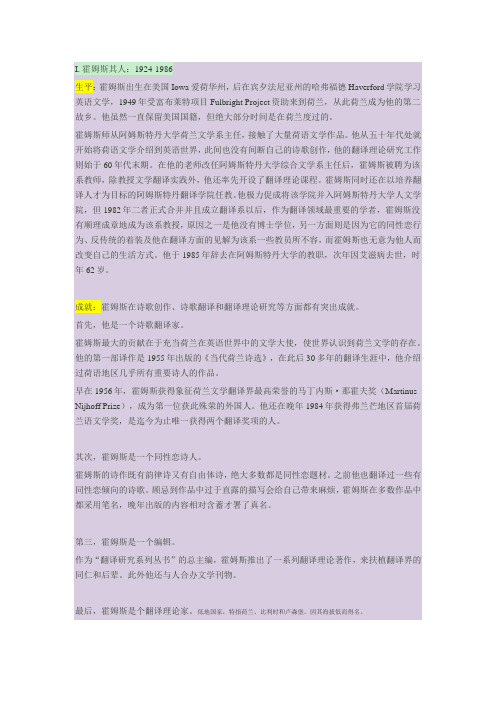

I. 霍姆斯其人:1924-1986生平:霍姆斯出生在美国Iowa爱荷华州,后在宾夕法尼亚州的哈弗福德Haverford学院学习英语文学,1949年受富布莱特项目Fulbright Project资助来到荷兰,从此荷兰成为他的第二故乡。

他虽然一直保留美国国籍,但绝大部分时间是在荷兰度过的。

霍姆斯师从阿姆斯特丹大学荷兰文学系主任,接触了大量荷语文学作品。

他从五十年代处就开始将荷语文学介绍到英语世界,此间也没有间断自己的诗歌创作,他的翻译理论研究工作则始于60年代末期。

在他的老师改任阿姆斯特丹大学综合文学系主任后,霍姆斯被聘为该系教师,除教授文学翻译实践外,他还率先开设了翻译理论课程。

霍姆斯同时还在以培养翻译人才为目标的阿姆斯特丹翻译学院任教。

他极力促成将该学院并入阿姆斯特丹大学人文学院,但1982年二者正式合并并且成立翻译系以后,作为翻译领域最重要的学者,霍姆斯没有顺理成章地成为该系教授,原因之一是他没有博士学位,另一方面则是因为它的同性恋行为、反传统的着装及他在翻译方面的见解为该系一些教员所不容,而霍姆斯也无意为他人而改变自己的生活方式。

他于1985年辞去在阿姆斯特丹大学的教职,次年因艾滋病去世,时年62岁。

成就:霍姆斯在诗歌创作、诗歌翻译和翻译理论研究等方面都有突出成就。

首先,他是一个诗歌翻译家。

霍姆斯最大的贡献在于充当荷兰在英语世界中的文学大使,使世界认识到荷兰文学的存在。

他的第一部译作是1955年出版的《当代荷兰诗选》,在此后30多年的翻译生涯中,他介绍过荷语地区几乎所有重要诗人的作品。

早在1956年,霍姆斯获得象征荷兰文学翻译界最高荣誉的马丁内斯·那霍夫奖(Martinus Nijhoff Prize),成为第一位获此殊荣的外国人。

他还在晚年1984年获得弗兰芒地区首届荷兰语文学奖,是迄今为止唯一获得两个翻译奖项的人。

其次,霍姆斯是一个同性恋诗人。

霍姆斯的诗作既有韵律诗又有自由体诗,绝大多数都是同性恋题材。

The Nature and Role of Norms in Translation 翻译规范

文本语言规范影响或决定译者实际上选择什么译语材料来代替源语材料,或作为源语材料的对等

物。

元规范与操作规范的关系 一般说来,元规范在逻辑和顺序排列上优先于操作规范,因为译者首先要慎重考虑翻译什么和选择 何种译本的问题。同时,两类主要规范之间相互影响甚至互为条件。例如,作为操作规范重要内容的 篇章切分一直有各种各样的传统(或模式),他们之间的差别对翻译来说都起一些暗示作用,通常,篇 章切分越接近目标文化传统翻译作品的可接受性就越强,所以,操作规范的作用也不容忽视。

图里翻译规范论的贡献与不足

贡献:

他把翻译纳入到一个宏观的社会文化语境进行研究,使翻译研究从传统的对文本进行孤立的 、静态的对比中解放出来。并尝试在社会文化的大背景下研究翻译的多维性质,使译者的策 略和一些翻译现象得到了合理的解释。

不足

1)图里的翻译规范论束缚了译者的主体性和创造性的发挥 2)图里提出的翻译规范论是描述性的,而翻译标准本身的描述性质也具有一定的局限性

翻译规范的本质分类多样性以及建立图里翻译规范论的贡献与不足gideontourygideontoury是以色列特拉维夫学派的又一代表人物在多元系统论的基础上研究希伯来文学的翻译提出以译语为中心的翻译观强调以实证的方法对大量译本进行描述性翻译研究从而找出译语文化中制约翻译过程中种种决定的规范

1

Gideon Toury简介

翻译规范的本质

规范的定义: 社会公认的普遍的价值观和观念,以区别正确与错误,适当与否。作为适用 于特定情况下的行为规范,可指导具体行为,可建立和保持社会秩序。规范 适用于一切文化活动或构成文化的任何系统。

图里认为翻译是受社会文化规范制约的活动。

制约翻译的因素

源语文本;语言之间的系统差异;文本传统;译者的认知能力

The Name and Nature of Translation Studies 翻译学的名与实

特定时间理论

特定问题理论

描写翻译研究、理论翻译研究和应用翻译研究之间的关系

霍尔姆斯认为翻译研究学科正是由描写翻译研究、理论翻译研究和应 用翻译研究这三部分有机构成的。他认为,其中每一部分都为另两部 分提供资料,也都在吸取和利用另两部分的研究成果:应用翻译研究 为描写翻译研究提供研究素材,描写翻译研究的研究成果为理论翻译 研究提供数据和基础,而理论和描写这两部分的研究成果又作用于应 用领域中,为了发展和繁荣整个学科,三者不可偏废任一。

面发展的目标是翻译社会学(或社会翻译学);

纯粹翻译研究 理论翻译研究(翻译理论) 翻译研究 译者培训 翻译工具 应用翻译研究 翻译政策 翻译批评

翻译过程研究:翻译过程或翻译行为本身,其中涉及到译 者的所思所想对翻译所起到的影响,目标是翻译心理学。 翻译总论 特定媒介理论 特定区域理论 局部翻译理论 特定层级理论 特定文类理论

THANKS

“翻译学学科的创建宣言”。

1 2

பைடு நூலகம்

建立翻译学科的条件

翻译学科的命名

主要内容

3

4

翻译研究的性质和目标

“翻译研究”的学科框架

建立翻译学科的条件

霍尔姆斯在《名与实》一文中指出了翻译学科应具备的建立一门独立学科所

需要的重要条件及其必要性。在过去几百年中,人们对翻译学科的研究始终 十分混乱,直到第二次世界大战之后,很多原本致力于相近学科研究的学者 (如语言学家、哲学家、文学研究家等)以及专注于信息学、逻辑学和数学等 表面上并不相近学科的学者都转向了翻译领域,他们把原学科的范式、半范 式、模型及方法带入翻译研究。翻译学成为独立学科所需的条件随着这些新 鲜研究方法的加入而成熟。

翻译学科的命名

霍尔姆斯认为术语研究在学术研究中处于十分重要的地位,因此,阻碍学科

Ralph_Waldo_Emerson

Biographical introduction

Ralph Waldo Emerson

An American essayist, philosopher and poet The most eloquent spokesman of New England Transcendentalism.

Son of a New England clergymen Experienced “genteel poverty”

Origins and Sources

foreign influences: 1) introduction of idealistic philosophy from

Germany and France. During his tour to Europe, he met and made friends with Coleridge, Carlyle, and Wordsworth and brought back with him the influence of European Romanticism. 2) Oriental mysticism such as Hinduism and the philosophy of the Chinese Confucius and Mencius. native influence:

Major works

Nature《论自然》 “The American Scholar”《美国学者》 “The Divinity School Address”《神学院演说》 “Self-Reliance” 《论自助》 “Over-soul” 《论超灵》

Nature (1836)

Nature is one of Emerson’s

The Role of Nature in Promoting Mental Health

The Role of Nature in Promoting MentalHealthNature plays a crucial role in promoting mental health, offering a wide range of benefits that contribute to overall well-being. The natural environment has a profound impact on mental health, providing a sense of calm, tranquility, and connection to the world around us. The therapeutic effects of nature have been well-documented, with research indicating that spending time outdoors can reduce stress, anxiety, and depression. Additionally, nature can enhance cognitive function, boost creativity, and improve mood. This essay will explore the various ways in which nature promotes mental health, drawing on scientific evidence and personal experiences to highlight the profound impact of the natural world on our psychological well-being. One of the most significant ways in which nature promotes mental health is through its ability to reduce stress and anxiety. The hustle and bustle of modern life can take a toll on our mental well-being, leading to feelings of overwhelm and unease. However, spending time in nature has been shown to lower cortisol levels, the hormone responsible for stress, and promote a state of relaxation. The sights, sounds, and smells of the natural world can have a calming effect on the mind, providing a much-needed respite from the demands of everyday life. Whether it's a leisurely walk through a forest, a peaceful afternoon by the ocean, or simply sitting in a park, immersing oneself in nature can help to alleviate stress and anxiety, promoting a sense of inner peace and tranquility. In addition to reducing stress, nature has the power to lift our spirits and improve our mood. The beauty of the natural world can evoke a sense of awe and wonder, leading to feelings of joy, gratitude, and contentment. Whetherit's witnessing a breathtaking sunrise, marveling at a majestic mountain range, or admiring the delicate intricacies of a flower, nature has the ability to inspire and uplift us. Research has shown that exposure to natural beauty can stimulate the release of dopamine, the "feel-good" neurotransmitter, leading to an enhanced sense of well-being. Furthermore, spending time in nature encourages physical activity, which has been linked to improved mood and a reduced risk of depression. Whether it's engaging in outdoor sports, hiking, or simply taking a leisurelystroll, being active in nature can have a positive impact on mental health, fostering a sense of vitality and happiness. Moreover, nature can provide a much-needed escape from the pressures of daily life, offering a sense of freedom, exploration, and adventure. The natural world presents an opportunity to disconnect from technology, work, and other stressors, allowing individuals to immerse themselves in the present moment and experience a sense of liberation. Whether it's camping in the wilderness, exploring a national park, or simply taking a day trip to the countryside, nature offers a space for reflection, introspection, and self-discovery. This sense of escape can be rejuvenating for the mind, providing a break from the monotony of daily routines and offering a fresh perspective on life. In doing so, nature can help individuals to recharge and re-energize, fostering a sense of resilience and inner strength. Furthermore, nature has the power to foster a sense of connection and belonging, both to the natural world and to others. The interconnectedness of all living things is a fundamental aspect of the natural environment, and being in nature can help individuals to feel a part of something greater than themselves. Whether it's observing the intricate web of life in a forest ecosystem, marveling at the diversity of plant and animal species, or simply feeling the earth beneath one's feet, nature can evoke a sense of unity and interconnectedness. This connection to nature has been shown to promote feelings of empathy, compassion, and altruism, as well as a greater sense of purpose and meaning in life. Furthermore, spending time in nature with others can strengthen social bonds, foster a sense of community, and enhance overall well-being. Whether it's going for a hike with friends, enjoying a picnic with family, or participating in outdoor group activities, nature provides a space for individuals to connect and build meaningful relationships, which are essential for mental health. In conclusion, nature plays a vital role in promoting mental health, offering a wide range of benefits that contribute to overall well-being. From reducing stress and anxiety to lifting our spirits and improving our mood, nature has the power to heal and restore the mind. Furthermore, nature provides a space for escape, exploration, and adventure, fostering a sense of freedom and rejuvenation. Additionally, nature fosters a sense of connection and belonging, both to the natural world and to others,promoting empathy, compassion, and social bonds. As such, it is essential to recognize the profound impact of nature on mental health and to prioritize spending time in the natural world as a means of promoting overall well-being.。

自然科学中英文对照外文翻译文献

中英文对照外文翻译(文档含英文原文和中文翻译)外文文献17In the first book we considered the idea merely as such, that is, only according to its general form. It is true that as far as the abstract idea, the concept, is concerned, we obtained a knowledge of it in respect of its content also, because it has content and meaning only in relation to the idea of perception, with out which it would be worthless and empty. Accordingly, directing our attention exclusively to the idea of perception, we shall now endeavour to arrive at a knowledge of its content, its more exact definition, and the forms which it presents to us. And it will specially interest us to find an explanation of its peculiar significance, that significance which is otherwise merely felt, but on account of which it is that these pictures do not pass by us entirely strange and meaningless, as they must other wise do, but speak to us directly, are understood, and obtain an interest which concerns our whole nature.We direct our attention to mathematics, natural science, and philosophy, for each of these holds out the hope that it will afford us a part of the explanation we desire. Now, taking philosophy first, we find that it is like a monster with many heads, each of which speaks a different language. They are not, indeed, all at variance on the point we are here considering, the significance of the idea of perception. For, with the exception of the Sceptics and the Idealists, the others, for the most part, speak very much in the same way of an object which constitutes the basis of the idea, and which is indeed different in its whole being and nature from the idea, but yet isin all points as like it as one egg is to another. But this does not help us, for we are quite unable to distinguish such an object from the idea; we find that they are one and the same; for every object always and for ever presupposes a subject, and therefore remains idea, so that we recognised objectivity as belonging to the most universal form of the idea, which is the division into subject and object. Further, the principle of sufficient reason, which is referred to in support of this doctrine, is for us merely the form of the idea, the orderly combination of one idea with another, but not the combination of the whole finite or infinite series of ideas with something which is not idea at all, and which cannot therefore be presented in perception. Of the Sceptics and Idealists we spoke above, in examining the controversy about the reality of the outer world.If we turn to mathematics to look for the fuller knowledge we desire of the idea of perception, which we have, as yet, only understood generally, merely in its form, we find that mathematics only treats of these ideas so far as they fill time and space, that is, so far as they are quantities. It will tell us with the greatest accuracy thehow-many and the how-much; but as this is always merely relative, that is to say, merely a comparison of one idea with others, and a comparison only in the one respect of quantity, this also is not the information we are principally in search of.Lastly, if we turn to the wide province of natural science, which is divided into many fields, we may, in the first place, make a general division of it into two parts. It is either the description of forms, which I call Morphology, or the explanation of changes, which I call Etiology. The first treats of the permanent forms, the second of the changing matter, according to the laws of its transition from one form to another.The first is the whole extent of what is generally called natural history. It teaches us, especially in the sciences of botany and zoology, the various permanent, organised, and therefore definitely determined forms in the constant change of individuals; and these forms constitute a great part of the content of the idea of perception. In natural history they are classified, separated, united, arranged according to natural and artificial systems, and brought under concepts which make a general view and knowledge of the whole of them possible. Further, an infinitely fine analogy both in the whole and in the parts of these forms, and running through them all (unité de plan), is established, and thus they may be com pared to innumerable variations on a theme which is not given. The passage of matter into these forms, that is to say, the origin of individuals, is not a special part of natural science, for every individual springs from its like by generation, which is everywhere equally mysterious, and has as yet evaded definite knowledge. The little that is known on the subject finds its place in physiology, which belongs to that part of natural science I have called etiology. Mineralogy also, especially where it becomes geology, inclines towards etiology, though it principally belongs to morphology. Etiology proper comprehends all those branches of natural science in which the chief concern is the knowledge of cause and effect. The sciences teach how, according to an invariable rule, one condition of matter is necessarily followed by a certain other condition; how one change necessarily conditions and brings about a certain other change; this sort of teaching is called explanation. The principal sciences in this department are mechanics, physics, chemistry, and physiology.If, however, we surrender ourselves to its teaching, we soon become convinced that etiology cannot afford us the information we chiefly desire, any more than morphology. The latter presents to us innumerable and in finitely varied forms, which are yet related by an unmistakable family likeness. These are for us ideas, and when only treated in this way, they remain always strange to us, and stand before us like hieroglyphics which we do not understand. Etiology, on the other hand, teaches us that, according to the law of cause and effect, this particular condition of matter brings about that other particular condition, and thus it has explained it and performed its part. However, it really does nothing more than indicate the orderlyarrangement according to which the states of matter appear in space and time, and teach in all cases what phenomenon must necessarily appear at a particular time in a particular place. It thus determines the position of phenomena in time and space, according to a law whose special content is derived from experience, but whose universal form and necessity is yet known to us independently of experience. But it affords us absolutely no information about the inner nature of any one of these phenomena: this is called a force of nature, and it lies outside the province of causal explanation, which calls the constant uniformity with which manifestations of such a force appear whenever their known conditions are present, a law of nature. But this law of nature, these conditions, and this appearance in a particular place at a particular time, are all that it knows or ever can know. The force itself which manifests itself, the inner nature of the phenomena which appear in accordance with these laws, remains always a secret to it, something entirely strange and unknown in the case of the simplest as well as of the most complex phenomena. For although as yet etiology has most completely achieved its aim in mechanics, and least completely in physiology, still the force on account of which a stone falls to the ground or one body repels another is, in its inner nature, not less strange and mysterious than that which produces the movements and the growth of an animal. The science of mechanics presupposes matter, weight, impenetrability, the possibility of communicating motion by impact, inertia and so forth as ultimate facts, calls them forces of nature, and their necessary and orderly appearance under certain conditions a law of nature. Only after this does its explanation begin, and it consists in indicating truly and with mathematical exactness, how, where and when each force manifests itself, and in referring every phenomenon which presents itself to the operation of one of these forces. Physics, chemistry, and physiology proceed in the same way in their province, only they presuppose more and accomplish less. Consequently the most complete etiological explanation of the whole of nature can never be more than an enumeration of forces which cannot be explained, and a reliable statement of the rule according to which phenomena appear in time and space, succeed, and make way for each other. But the inner nature of the forces which thus appear remains unexplained by such an explanation, which must confineitself to phenomena and their arrangement, because the law which it follows does not extend further. In this respect it may be compared to a section of a piece of marble which shows many veins beside each other, but does not allow us to trace the course of the veins from the interior of the marble to its surface. Or, if I may use an absurd but more striking comparison, the philosophical investigator must always have the same feeling towards the complete etiology of the whole of nature, as a man who, without knowing how, has been brought into a company quite unknown to him, each member of which in turn presents another to him as his friend and cousin, and therefore as quite well known, and yet the man himself, while at each introduction he expresses himself gratified, has always the question on his lips: "But how the deuce do I stand to the whole company?"Thus we see that, with regard to those phenomena which we know only as our ideas, etiology can never give us the desired information that shall carry us beyond this point. For, after all its explanations, they still remain quite strange to us, as mere ideas whose significance we do not understand. The causal connection merely gives us the rule and the relative order of their appearance in space and time, but affords us no further knowledge of that which so appears. Moreover, the law of causality itself has only validity for ideas, for objects of a definite class, and it has meaning only in so far as it presupposes them. Thus, like these objects themselves, it always exists only in relation to a subject, that is, conditionally; and so it is known just as well if we start from the subject, i.e., a priori, as if we start from the object, i.e., a posteriori. Kant indeed has taught us this.But what now impels us to inquiry is just that we are not satisfied with knowing that we have ideas, that they are such and such, and that they are connected according to certain laws, the general expression of which is the principle of sufficient reason. We wish to know the significance of these ideas; we ask whether this world is merely idea; in which case it would pass by us like an empty dream or a baseless vision, not worth our notice; or whether it is also something else, something more than idea, and if so, what. Thus much is certain, that this something we seek for must be completely and in its whole nature different from the idea; that the forms and laws of the idea must therefore be completely foreign to it; further, thatwe cannot arrive at it from the idea under the guidance of the laws which merely combine objects, ideas, among themselves, and which are the forms of the principle of sufficient reason.Thus we see already that we can never arrive at the real nature of things from without. However much we investigate, we can never reach anything but images and names. We are like a man who goes round a castle seeking in vain for an entrance, and sometimes sketching the façades. And yet this is the method that has been followed by all philosophers before me.18In fact, the meaning for which we seek of that world which is present to us only as our idea, or the transition from the world as mere idea of the knowing subject to whatever it may be besides this, would never be found if the investigator himself were nothing more than the pure knowing subject (a winged cherub without a body). But he is himself rooted in that world; he finds himself in it as an individual, that is to say, his knowledge, which is the necessary supporter of the whole world as idea, is yet always given through the medium of a body, whose affections are, as we have shown, the starting-point for the understanding in the perception of that world. His body is, for the pure knowing subject, an idea like every other idea, an object among objects. Its movements and actions are so far known to him in precisely the same way as the changes of all other perceived objects, and would be just as strange and incomprehensible to him if their meaning were not explained for him in an entirely different way. Otherwise he would see his actions follow upon given motives with the constancy of a law of nature, just as the changes of other objects follow upon causes, stimuli, or motives. But he would not understand the influence of the motives any more than the connection between every other effect which he sees and its cause. He would then call the inner nature of these manifestations and actions of his body which he did not understand a force, a quality, or a character, as he pleased, but he would have no further insight into it. But all this is not the case; indeed, the answer to the riddle is given to the subject of knowledge who appears as an individual, and the answer is will. This and this alone gives him the key to his own existence, reveals to him the significance, shows him the inner mechanism of hisbeing, of his action, of his movements. The body is given in two entirely different ways to the subject of knowledge, who becomes an individual only through his identity with it. It is given as an idea in intelligent perception, as an object among objects and subject to the laws of objects. And it is also given in quite a different way as that which is immediately known to every one, and is signified by the word will. Every true act of his will is also at once and without exception a movement of his body. The act of will and the movement of the body are not two different things objectively known, which the bond of causality unites; they do not stand in the relation of cause and effect; they are one and the same, but they are given in entirely different ways, — immediately, and again in perception for the understanding. The action of the body is nothing but the act of the will objectified, i.e., passed into perception. It will appear later that this is true of every movement of the body, not merely those which follow upon motives, but also involuntary movements which follow upon mere stimuli, and, indeed, that the whole body is nothing but objectified will, i.e., will become idea. All this will be proved and made quite clear in the course of this work. In one respect, therefore, I shall call the body the objectivity of will; as in the previous book, and in the essay on the principle of sufficient reason, in accordance with the one-sided point of view intentionally adopted there (that of the idea), I called it the immediate object. Thus in a certain sense we may also say that will is the knowledge a priori of the body, and the body is the knowledge a posteriori of the will. Resolutions of the will which relate to the future are merely deliberations of the reason about what we shall will at a particular time, not real acts of will. Only the carrying out of the resolve stamps it as will, for till then it is never more than an intention that may be changed, and that exists only in the reason in abstracto. It is only in reflection that to will and to act are different; in reality they are one. Every true, genuine, immediate act of will is also, at once and immediately, a visible act of the body. And, corresponding to this, every impression upon the body is also, on the other hand, at once and immediately an impression upon the will. As such it is called pain when it is opposed to the will; gratification or pleasure when it is in accordance with it. The degrees of both are widely different. It is quite wrong, however, to call pain and pleasure ideas, for they are by no meansideas, but immediate affections of the will in its manifestation, the body; compulsory, instantaneous willing or not-willing of the impression which the body sustains. There are only a few impressions of the body, which do not touch the will, and it is through these alone that the body is an immediate object of knowledge, for, as perceived by the understanding, it is already an indirect object like all others. These impressions are, therefore, to be treated directly as mere ideas, and excepted from what has been said. The impressions we refer to are the affections of the purely objective senses of sight, hearing, and touch, though only so far as these organs are affected in the way which is specially peculiar to their specific nature. This affection of them is so excessively weak an excitement of the heightened and specifically modified sensibility of these parts that it does not affect the will, but only furnishes the understanding with the data out of which the perception arises, undisturbed by any excitement of the will. But every stronger or different kind of affection of these organs of sense is painful, that is to say, against the will, and thus they also belong to its objectivity. Weakness of the nerves shows itself in this, that the impressions which have only such a degree of strength as would usually be sufficient to make them data for the understanding reach the higher degree at which they influence the will, that is to say, give pain or pleasure, though more often pain, which is, however, to some extent deadened and inarticulate, so that not only particular tones and strong light are painful to us, but there ensues a generally unhealthy and hypochondriacal disposition which is not distinctly understood. The identity of the bodv and the will shows itself further, among other ways, in the circumstance that every vehement and excessive movement of the will, i.e., every emotion, agitates the body and its inner constitution directly, and disturbs the course of its vital functions. This i s shown in detail in “Will in Nature” p. 27 of the second edition and p.28 of the third.外文文献翻译:17在第一篇里我们只是把表象作为表象,从而也只是在普遍的形式上加以考察。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

绝对规则 ------------翻译规范的主体意识因素------------个人风格

翻译:两种语言和文化系统------〉两套规范系统, 翻译价值的两个要素: 1)译文作为目标语篇章在目标文化或该文化的某个部分中占据一定位置或 填补空缺 2)译文是某个预先存在的源语篇章在目标语中的表述。源语篇章属于源语 文化并在其中占有确定位置。 不同的语言、文化和篇章传统常不兼容,因此需要翻译规范的调节作用 翻译规范在某种程度上可说是译者们在两种不同语言、文化、篇章传统规 范之间取舍的产物。在翻译过程中,翻译者可受原文及其规范支配,也可受 目标语中使用的规范支配。

操作性规范影响篇章中语言材料的分布方式、篇章结构和文字表述,因此也直接或间接地约束目 标语篇章和源语篇章之间公认的关系,即哪些在转变中可能维持不变,哪些会发生变化。 操作性规范又分为母体规范和文本语言规范 母体规范决定代替源语材料出现的译语材料的形式和它在文本中的位置与分割,还决定省略、增 加和位置改变的程度。

如何应对翻译规范的变化? (1)有些译者试图通过诸如翻译思想、翻译批评等方式促进规范变的形成, 以便控制这些变化。 (2)一部分人,包括翻译者、翻译活动发起人及赞助人顺从社会压力,不 断根据变化着的规范调整自己的行为; (3)还有少部分人仍抱着旧规范不放。

翻译规范的多样性

1) 社会文化的特殊性 规范的特殊性在于它只能由其赖以存在的系统赋予其意义, 即使是外部 行为看起来完全相同的系统之间实际上仍有差异。 2)不稳定性 规范是不稳定的、变化的实体。

翻译的直接程度涉及从最原始版本语言以外的其他语言版本进行翻译(间接翻译)的裕度界线:能 否允许间接翻译?从何种源语/篇章类型/时期进行翻译时禁止/允许/容忍何用某一特定翻译 形式?什么是人们禁止/允许/容忍何用的中介语言?是否有倾向/义务表明译文是从某种中介语 文本翻译而来或忽略/隐瞒/否认这一事实?如果提及这一事实,是否要明确中介语的身份?(是 否接受从另外一种语言而不是源语来进行翻译)

不足

图里的翻译规范论束缚了译者的主体性和创造性的发挥

1)篇章:译文篇章本身是各种翻译规范的集中体现,是分析各种规范的资料总库,是形形 色色的规范之源泉。在翻译过程中,译者会有意无意遵循某些原则,这些原则既包括译者 对源语和目标语语言、文化及篇章传统限制因素的认识,也包括个人癖好。其中一些具有 普遍意义,具有共性的东西逐渐为很多人所共同遵循,这就形成了规范。规范本身并不是 显性的,它们隐含在译文篇章之中 2)篇章外:集半理论性或评论性的观点为一体,如翻译的规定性理论和译者、编辑、出版 人以及翻译活动所涉及人员对个别作品、译者或翻译“流派”的评价等。

翻译规范的分类

Toury认为规范制约所有种类的翻译,而且,规范能运用于翻译活动的任何阶段,能反映在翻译产品 的每一层面。他对翻译规范划分作了划分: 元规范(宏观):翻译方针有关的因素;与翻译直接程度有关的因素 操作性规范(微观):一般指译者翻译活动中使用的翻译技巧

翻译方针既涉及在一定历史背景下指导篇章类型的选择,也涉及与在特定时期通过翻译输入某 种语言/文化的个体篇章有关的因素(影响或决定作品选择的因素,如作者、文学类型、学派、 等)

翻译规范的本质

规范的定义: 社会公认的普遍的价值观和观念,以区别正确与错误,适当与否。作为适用 于特定情况下的行为规范,可指导具体行为,可建立和保持社会秩序。规范 适用于一切文化活动或构成文化的任何系统。

图里认为翻译是受社会文化规范制约的活动。

制约翻译的因素

源语文本;语言之间的系统差异;文本传统;译者的认知能力

图里翻译规范论的贡献与不足

贡献:

他把翻译纳入到一个宏观的社会文化语境进行研究,使翻译研究从传统的对文本进行孤立的 、静态的对比中解放出来。并尝试在社会文化的大背景下研究翻译的多维性质,使译者的策 略和一些翻译现象得到了合理的解释。

不足

1)图里的翻译规范论束缚了译者的主体性和创造性的发挥 2)图里提出的翻译规范论是描述性的,而翻译标准本身的描述性质也具有一定的局限性

三种不同类型、又彼此竞争的规范

在边缘徘徊的新规范的维形------前卫 处于中心地位,指导主流翻译行为的规范-----主流 过去规范的残余--------- 过时

翻译规范的建立

翻译规范的建立需通过两个主要途径:篇章和篇章外。

1)篇章:译文篇章本身是各种翻译规范的集中体现,是分析各种规范的资料总库,是形形 色色的规范之源泉。在翻译过程中,译者会有意无意遵循某些原则,这些原则既包括译者 对源语和目标语语言、文化及篇章传统限制因素的认识,也包括个人癖好。其中一些具有 普遍意义,具有共性的东西逐渐为很多人所共同遵循,这就形成了规范。规范本身并不是 显性的,它们隐含在译文篇章之中 2)篇章外:集半理论性或评论性的观点为一体,如翻译的规定性理论和译者、编辑、出版 人以及翻译活动所涉及人员对个别作品、译者或翻译“流派”的评价等。

文本语言规范影响或决定译者实际上选择什么译语材料来代替源语材料,或作为源语材料的对等

物。

元规范与操作规范的关系 一般说来,元规范在逻辑和顺序排列上优先于操作规范,因为译者首先要慎重考虑翻译什么和选择 何种译本的问题。同时,两类主要规范之间相互影响甚至互为条件。例如,作为操作规范重要内容的 篇章切分一直有各种各样的传统(或模式),他们之间的差别对翻译来说都起一些暗示作用,通常,篇 章切分越接近目标文化传统翻译作品的可接受性就越强,所以,操作规范的作用也不容忽视。

1

Gideon Toury简介

CONTENTS

2

翻译规范论的理论来源和主要思想

3

The Nature and Role of Norms in Translation 的主要内容: 翻译规范的本质、分类、多样性以及建立 图里翻译规范论的贡献与不足

4

Gideon Toury

Gideon Toury是以色列特拉维夫学派的又一代表人物,在多元系统论的基础上

Initial Norms初始规范:决定译者翻译时的整体取向 遵循源语的语篇关系和规范-----------充分翻译 遵循译语以及译语文学多元系统的语言和文学规范-殊性 规范的特殊性在于它只能由其赖以存在的系统赋予其意义, 即使是外部 行为看起来完全相同的系统之间实际上仍有差异。 2)不稳定性 规范是不稳定的、变化的实体。

研究希伯来文学的翻译,提出以译语为中心的翻译观,强调以实证的方法对大

量译本进行描述性翻译研究,从而找出译语文化中制约翻译过程中种种决定的 规范。他认为,翻译是受制于规范的,而翻译的规范又在很大程度上取决于翻 译活动及翻译产品在译语文化中的位置。

翻译规范论的理论来源和主要思想

埃文・佐哈尔的“多元系统理论”将社会符号置于相互影响的多 元系统中,为翻译研究开辟了一条描述性和系统性的新途径。自 此以后,西方译学研究从理论阐述向文本描述转移。到图里对翻 译进行描述研究时,这种研究范式得以进一步完善。图里的描述 翻译学特别强调研究两种不同系统中作家、作品、读者及其文学 翻译规范之间的关系,对源语和目的语的语用和接受关系,甚至 包括出版发行等社会要素之间的关系进行探讨。

Thank you