Toward a Theory of Property Rights(关于产权的理论)——德姆塞兹

“产权”—阿尔钦(最新译本)

第六卷Property Rights产权私有产权产权是一种通过社会强制而实现的对某种经济物品的多种用途进行选择的权利。

属于个人的产权即为私有产权,它可以转让,以换取对其他物品同样的权利。

私有产权的有效性取决于对其强制实现的可能性及为之付出的代价,这种强制有赖于政府的力量、日常社会活动以及通行的伦理和道德规范。

简言之,没有经过你的许可或者没有给你补偿,任何人都不能合法地使用,也不能影响那些产权归你所有的物品的物理属性。

在假设的私有产权完备的条件下,我利用我的资源而采取的任何行动,都不可以影响任何其他人的私有财产的物理属性。

例如,你对你的计算机的私有产权限制了我和其他每一个人对它的使用行为,而我的私有产权则限制了你和其他每一个人对我所拥有的一切东西的使用行为。

这里需要强调的是,一个物品不受他人行动影响的是指其物质性状和实际用途,而不是它的交换价值。

P697私有产权是授予人们的、在那些必然相互冲突的各种用途之间进行选择的权利。

这种权利并不是对物品的可能用途施以人为的或强加的限制,而是对这些用途进行选择的排他性权利。

如果限制我在我的土地上种植玉米,那将是一个强加的或者人为的限制,这样做剥夺了并没有转让给被人的权利。

剥夺我在我的土地上种植玉米的权利,将限制我在这块土地上的使用机会,而没有扩展任何其他人的使用机会。

人为的或不必要的限制不是私有产权赖以存在的基础。

还要指出的是,由于这些限制通常只是针对个别人而实行的,所以那些不受这种限制的人,就会从别人无端受限的活动当中,取得“合法的垄断”。

在产权私有的条件下,任何取得双方同意的契约条款都是得到认可的,尽管它们未必全都得到政府强制力的支持。

契约条款有多大程度受到禁止,私有产权就有多大程度受到剥夺。

例如,每天工作十小时以上的契约,不管支付的工资有多高,都会被认为是非法的。

或者,当商品售价超过出于政治考虑而划定的某种界限时,也可能是非法的。

这些限制削弱了私有财产、市场交换和契约作为调节生产和消费以及解决利益冲突的手段的力量。

2 产权理论

Private Ownership Definition Recognizes the right of the owner to exclude others from exercising the owner's private rights

Communal Ownership State Ownership A right which can be exercised by all members of the community Exclude anyone from the use of a right as long as the state follows accepted political procedures for determining who may not use state-owned property

具有排他性 可分离

功能

界定产权边界,形成合理预期

为外部性的内部化提供激励 明确主体权利和责任,提高社会经济运行效率

产权分类

私有产权

私人独有

基本产权形式,受政府、法律、道德等保护

社团产权

部分人共同拥有

排他性?有条件拥有、分割性?转让性?

国有产权

主体为政府、采取多种委托代理(如;

马克思的有关论述

“马克思是第一位有产权理论的科学家”(S. 佩乔维奇,1990) 马克思关于所有制的论述

私有制是商品交换的前提和基础 所有制是表现现实经济关系并以之为基础的法权

关系 所有制是生产关系的总和 所有制性质因劳动者地位和其反映的社会经济关 系不同而有本质差别

产权与所有制关系

如果两者未配置为单一行为主体?

Property Rights—By Alchian

Property Rightsby Armen A. AlchianOne of the most fundamental requirements of a capitalist economic system—and one of the most misunderstood concepts—is a strong system of property rights. For decades social critics in the United States and throughout the Western world have complained that "property" rights too often take precedence over "human" rights, with the result that people are treated unequally and have unequal opportunities. Inequality exists in any society. But the purported conflict between property rights and human rights is a mirage—property rights are human rights.The definition, allocation, and protection of property rights is one of the most complex and difficult set of issues that any society has to resolve, but it is one that must be resolved in some fashion. For the most part social critics of "property" rights do not want to abolish those rights. Rather, they want to transfer them from private ownership to government ownership. Some transfers to public ownership (or control, which is similar) make an economy more effective. Others make it less effective. The worst outcome by far occurs when property rights really are abolished (see The Tragedy of the Commons).A property right is the exclusive authority to determine how a resource is used, whether that resource is owned by government or by individuals. Society approves the uses selected by the holder of the property right with governmental administered force and with social ostracism. If the resource is owned by the government, the agent who determines its use has to operate under a set of rules determined, in the United States, by Congress or by executive agencies it has charged with that role.Private property rights have two other attributes in addition to determining the use of a resource. One is the exclusive right to the services of the resource. Thus, for example, the owner of an apartment with complete property rights to the apartment has the right to determine whether to rent it out and, if so, which tenant to rent to; to live in it himself; or to use it in any other peaceful way. That is the right to determine the use. If the owner rents out the apartment, he also has the right to all the rental income from the property. That is the right to the services of the resources (the rent). Finally, a private property right includes the right to delegate, rent, or sell any portion of the rights by exchange or gift at whatever price the owner determines (provided someone is willing to pay that price). If I am not allowed to buy some rights from you and you therefore are not allowed to sell rights to me, private property rights are reduced. Thus, the three basic elements of private property are (1) exclusivity of rights to the choice of use of a resource, (2) exclusivity of rights to the services of a resource, and (3) rights to exchange the resource at mutually agreeable terms.The U.S. Supreme Court has vacillated about this third aspect of property rights. But no matter what words the justices use to rationalize recent decisions, the fact is that such limitations as price controls and restrictions on the right to sell at mutually agreeable terms are reductions of private property rights. Many economists (myself included) believe that most such restrictions on property rights are detrimental to society. Here are some of the reasons why.Under a private property system the market values of property reflect the preferences and demands of the rest of society. No matter who the owner is, the use of the resource is influenced by what the rest of the public thinks is the most valuable use. The reason is that an owner who chooses some other use must forsake thathighest-valued use—and the price that others would pay him for the resource or for the use of it. This creates an interesting paradox: although property is called "private," private decisions are based on public, or social, evaluation.The fundamental purpose of property rights, and their fundamental accomplishment, is that they eliminate destructive competition for control of economic resources.Well-defined and well-protected property rights replace competition by violence with competition by peaceful means.The extent and degree of private property rights fundamentally affect the ways people compete for control of resources. With more complete private property rights, market exchange values become more influential. The personal status and personal attributes of people competing for a resource matter less because their influence can be offset by adjusting the price. In other words, more complete property rights make discrimination more costly. Consider the case of a black woman who wants to rent an apartment from a white landlord. She is better able to do so when the landlord has the right to set the rent at whatever level he wants. Even if the landlord would prefer a white tenant, the black woman can offset her disadvantage by offering a higher rent.A landlord who takes the white tenant at a lower rent anyway pays for discriminating.But if the government imposes rent controls that keep the rent below the free-market level, the price that the landlord pays to discriminate falls, possibly to zero. The rent control does not magically reduce the demand for apartments. Instead, it reduces every potential tenant's ability to compete by offering more money. The landlord, now unable to receive the full money price, will discriminate in favor of tenants whose personal characteristics—such as age, sex, ethnicity, and religion—he favors. Now the black woman seeking an apartment cannot offset the disadvantage of her skin color by offering to pay a higher rent.Competition for apartments is not eliminated by rent controls. What changes is the "coinage" of competition. The restriction on private property rights reduces competition based on monetary exchanges for goods and services and increases competition based on personal characteristics. More generally, weakening privateproperty rights increases the role of personal characteristics in inducing sellers to discriminate among competing buyers and buyers to discriminate among sellers.The two extremes in weakened private property rights are socialism and "commonly owned" resources. Under socialism, government agents—those whom the government assigns—exercise control over resources. The rights of these agents to make decisions about the property they control are highly restricted. People who think they can put the resources to more valuable uses cannot do so by purchasing the rights because the rights are not for sale at any price. Because socialist managers do not gain when the values of the resources they manage increase, and do not lose when the values fall, they have little incentive to heed changes in market-revealed values. The uses of resources are therefore more influenced by the personal characteristics and features of the officials who control them. Consider, in this case, the socialist manager of a collective farm. By working every night for one week, he could make 1 million rubles of additional profit for the farm by arranging to transport the farm's wheat to Moscow before it rots. But if neither the manager nor those who work on the farm are entitled to keep even a portion of this additional profit, the manager is more likely than the manager of a capitalist farm to go home early and let the crops rot.Similarly, common ownership of resources—whether in what was formerly the Soviet Union or in the United States—gives no one a strong incentive to preserve the resource. A fishery that no one owns, for example, will be overfished. The reason is that a fisherman who throws back small fish to wait until they grow is unlikely to get any benefit from his waiting. Instead, some other fisherman will catch the fish. The same holds true for other common resources whether they be herds of buffalo, oil in the ground, or clean air. All will be overused.Indeed a main reason for the spectacular failure of recent economic reforms in the Soviet Union is that resources were shifted from ownership by government to de facto common ownership. How? By making the Soviet government's revenues de facto into a common resource. Harvard economist Jeffrey Sachs, who advised the Soviet government, has pointed out that when Soviet managers of socialist enterprises were allowed to open their own businesses but still were left as managers of the government's businesses, they siphoned out the profits of the government's business into their private corporations. Thousands of managers doing this caused a large budget deficit for the Soviet government. In this case the resource that no manager had an incentive to conserve was the Soviet government's revenues. Similarly, improperly set premiums for U.S. deposit insurance give banks and S&Ls an incentive to make excessively risky loans and to treat the deposit-insurance fund as a "common" resource.Private property rights to a resource need not be held by a single person. They can be shared, with each person sharing in a specified fraction of the market value while decisions about uses are made in whatever process the sharing group deems desirable.A major example of such shared property rights is the corporation. In alimited-liability corporation, shares are specified and the rights to decide how to use the corporation's resources are delegated to its management. Each shareholder has the unrestrained right to sell his or her share. Limited liability insulates each shareholder's wealth from the liabilities of other shareholders, and thereby facilitates anonymous sale and purchase of shares.In other types of enterprises, especially where each member's wealth will become uniquely dependent on each other member's behavior, property rights in the group endeavour are usually salable only if existing members approve of the buyer. This is typical for what are often called joint ventures, "mutuals," and partnerships.While more complete property rights are preferable to less complete rights, any system of property rights entails considerable complexity and many issues that are difficult to resolve. If I operate a factory that emits smoke, foul smells, or airborne acids over your land, am I using your land without your permission? This is difficult to answer.The cost of establishing private property rights—so that I could pay you a mutually agreeable price to pollute your air—may be too expensive. Air, underground water, and electromagnetic radiations, for example, are expensive to monitor and control. Therefore, a person does not effectively have enforceable private property rights to the quality and condition of some parcel of air. The inability to cost-effectively monitor and police uses of your resources means "your" property rights over "your" land are not as extensive and strong as they are over some other resources, like furniture, shoes, or automobiles. When private property rights are unavailable or too costly to establish and enforce, substitute means of control are sought. Government authority, expressed by government agents, is one very common such means. Hence the creation of environmental laws.Depending upon circumstances certain actions may be considered invasions of privacy, trespass, or torts. If I seek refuge and safety for my boat at your dock during a sudden severe storm on a lake, have I invaded "your" property rights, or do your rights not include the right to prevent that use? The complexities and varieties of circumstances render impossible a bright-line definition of a person's set of property rights with respect to resources.Similarly, the set of resources over which property rights may be held is not well defined and demarcated. Ideas, melodies, and procedures, for example, are almost costless to replicate explicitly (near-zero cost of production) and implicitly (no forsaken other uses of the inputs). As a result, they typically are not protected as private property except for a fixed term of years under a patent or copyright.Private property rights are not absolute. The rule against the "dead hand" or the rule against perpetuities is an example. I cannot specify how resources that I own will be used in the indefinitely distant future. Under our legal system, I can only specify theuse for a limited number of years after my death or the deaths of currently living people. I cannot insulate a resource's use from the influence of market values of all future generations. Society recognizes market prices as measures of the relative desirability of resource uses. Only to the extent that rights are salable are those values most fully revealed.Accompanying and conflicting with the desire for secure private property rights for one's self is the desire to acquire more wealth by "taking" from others. This is done by military conquest and by forcible reallocation of rights to resources (also known as stealing). But such coercion is antithetical to—rather than characteristic of—a system of private property rights. Forcible reallocation means that the existing rights have not been adequately protected.Private property rights do not conflict with human rights. They are human rights. Private property rights are the rights of humans to use specified goods and to exchange them. Any restraint on private property rights shifts the balance of power from impersonal attributes toward personal attributes and toward behavior that political authorities approve. That is a fundamental reason for preference of a system of strong private property rights: private property rights protect individual liberty.About the AuthorArmen A. Alchian is an emeritus professor of economics at the University of California, Los Angeles. Most of his major scientific contributions are in the economics of property rights. (See also: Biography: Armen Alchian.)Further ReadingAlchian, Armen. "Some Economics of Property Rights." Il Politico 30 (1965):816-29.Alchian, Armen, and Harold Demsetz. "The Property Rights Paradigm." Journal of Economic History (1973): 174-83.Demsetz, Harold. "When Does the Rule of Liability Matter?" Journal of Legal Studies 1 (January 1972): 13-28.Siegan, B. Economic Liberties and the Constitution. 1980.Interview with Jeffrey Sachs. Omni, June 1991: 98.。

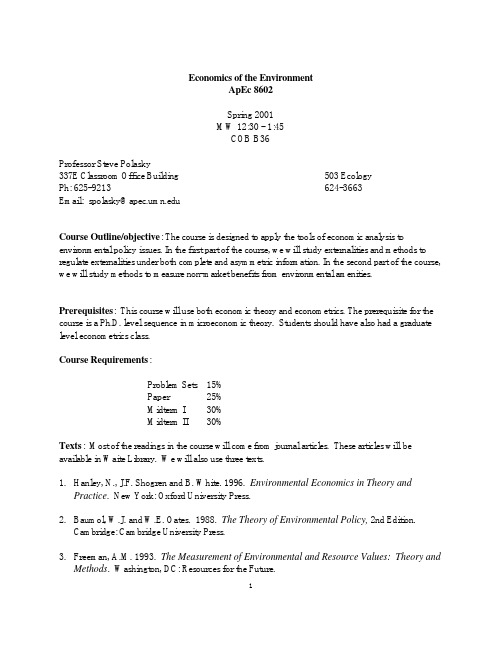

Economics of the Environment:环境经济学的

Economics of the EnvironmentApEc 8602Spring 2001MW 12:30 - 1:45COB B36Professor Steve Polasky337E Classroom Office Building 503 EcologyPh: 625-9213 624-3663Email: spolasky@Course Outline/objective: The course is designed to apply the tools of economic analysis to environmental policy issues. In the first part of the course, we will study externalities and methods to regulate externalities under both complete and asymmetric information. In the second part of the course, we will study methods to measure non-market benefits from environmental amenities. Prerequisites: This course will use both economic theory and econometrics. The prerequisite for the course is a Ph.D. level sequence in microeconomic theory. Students should have also had a graduate level econometrics class.Course Requirements:Problem Sets 15%Paper 25%Midterm I 30%Midterm II 30%Texts: Most of the readings in the course will come from journal articles. These articles will be available in Waite Library. We will also use three texts.1. Hanley, N., J.F. Shogren and B. White. 1996. Environmental Economics in Theory andPractice. New York: Oxford University Press.2. Baumol, W.J. and W.E. Oates. 1988. The Theory of Environmental Policy, 2nd Edition.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.3. Freeman, A.M. 1993. The Measurement of Environmental and Resource Values: Theory andMethods. Washington, DC: Resources for the Future.1In addition, there are a number of good books that you might want to consider having if you intend to do environmental economics as a field. Some recommended books are:1. Braden, J. and C. Kolstad (eds.) 1991. Measuring the Demand for EnvironmentalQuality. Amsterdam: North Holland.2. Bromley, D. (ed.) 1995. The Handbook of Environmental Economics. Cambridge, MA:Blackwell Publishers.3. Cornes, R. and T. Sandler. 1986. The Theory of Externalities, Public Goods and Clubs.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.4. Cummings, R., D. Brookshire and W. Schulze. 1986. Valuing Environmental Goods.Totowa, NJ: Rowman and Littlefield.5. Dorfman, R. and N.S. Dorfman (eds.). 1993. Economics of the Environment: SelectedReadings 3rd Edition. New York: Norton.6. Hausman, J.A. (ed.) 1993. Contingent Valuation: A Critical Assessment. Amsterdam:North-Holland Press.7. Johnansson, P.-O. 1987. The Economic Theory and Measurement of EnvironmentalBenefits. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.8. Just, R., D. Hueth, and A. Schmitz. 1982. Applied Welfare Economics and Public Policy.Engelwood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.9. Kopp, R. and V.K. Smith (eds.) 1993. Valuing Natural Assets: The Economics ofNatural Resource Damage Assessments. Washington, DC: Resources for the Future.10. Laffont, J. 1988. Fundamentals of Public Economics. Cambridge: MIT Press.11. Laffont, J.-J. and J. Tirole. 1993. A Theory of Incentives in Procurement and Regulation.Cambridge: MIT Press.12. Maler, K.-G. 1974. Environmental Economics: A Theoretical Inquiry. Baltimore: JohnsHopkins University Press.13. Mitchell, R. and R. Carson. 1989. Using Surveys to Value Public Goods: The ContingentValuation Method. Washington, DC: Resources for the Future.14. Oates, W. 1992. The Economics of the Environment. Brookfield, VT: Edward Elgar.15. Portney, P.R. and R.N. Stavins (eds.) 2000. Public Policies for Environmental Protection,2nd Edition. Washington, DC: Resources for the Future.16. Xepapadeas, A. 1998. Advanced Principles in Environmental Economics. Cheltenham,UK: Edward Elgar.Reading List(* indicates required readings)I. Introduction and Overview1. * Hanley, N., J.F. Shogren and B. White. 1996. Environmental Economics in Theory andPractice. Ch. 1.22. The Economist. Costing the earth: a survey of the environment. Sept. 2, 1989.3. Cropper, M. and W. Oates. 1992. Environmental economics: a survey. Journal of EconomicLiterature 30: 675-740.II. Externalities and Environmental Policy 1: Complete InformationA. Efficiency and the Welfare Theorems1. * Varian, H. 1992. Microeconomic Analysis, 3rd Edition. New York: Norton. Ch. 17-18.2. Dorfman, R. 1993. Some concepts from welfare economics. In Economics of theEnvironment: Selected Readings, R. Dorfman and N.S. Dorfman (eds.). New York: Norton.B. Public Goods, Externalities and Pigouvian Taxes1. * Hanley, N., J.F. Shogren and B. White. 1996. Environmental Economics in Theory andPractice. Ch.2 – 4.2. * Mas-Colell, A., M. Whinston and J. Green. 1995. Microeconomic Theory, Chapter 11.Oxford University Press.3. * Baumol, W. and W. Oates. The Theory of Environmental Policy, Ch. 2-4.4. Cornes, R. and T. Sandler. 1986. The Theory of Externalities, Public Goods, and ClubGoods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Ch. 5-6.5. Bator, F. 1958. The anatomy of market failure. Quarterly Journal of Economics 47: 351-379.6. Samuelson, P.A. 1955. Diagrammatic exposition of the pure theory of public expenditure.Review of Economics and Statistics 37: 350-356.C. Nonconvexities1. * Baumol, W. and W. Oates. The Theory of Environmental Policy, Ch. 7 - 8.2. * Hurwicz, L. 1999. Revisiting externalities. Journal of Public Economic Theory 2: 225-245.3. Starrett, D.A. 1972. Fundamental nonconvexities in the theory of externalities. Journal ofEconomic Theory 4: 180-199.4. Baumol, W.J. and D. F. Bradford. 1972. Detrimental externalities and non-convexities of theproduction set. Economica 39: 160-176.5. * Helfand, G. and J. Rubin. 1994. Spreading versus concentrating damages: environmentalpolicy in the presence of nonconvexities. Journal of Environmental Economics andManagement 27: 84-91.3D. Entry and Exit1. Rose-Ackerman, S. 1973. Effluent charges: a critique. Canadian Journal of Economics 6:512-527.2. *Spulber, D. 1985. Effluent regulation and long-run optimality. Journal of EnvironmentalEconomics and Management 12: 103-116.3. Kohn, R.E. 1994. Do we need the entry-exit condition on polluting firms? Journal ofEnvironmental Economics and Management 27: 92-97.4. McKitrick, R. and R.A. Collinge. 2000. Linear Pigouvian taxes and the optimal size of apolluting industry. Canadian Journal of Economics 33: 1106-1119.E. Averting Behavior1. * Bird, P. 1987. The transferability and depletability of externalities. Journal ofEnvironmental Economics and Management 14: 54-57.2. * Shibuta, H. and Winrich, J. 1983. Control of pollution when the offended defendthemselves. Economica 50: 425-437.3. Smith, V.K. and W.Desvouges. 1986. Averting behavior: does it exist? Economics Letters29: 291-296.F. Property Rights and Bargaining1. * Coase, R. 1960. The problem of social cost. Journal of Law and Economics 3: 1-44.2. Demsetz, A. 1967. Toward a theory of property rights. American Economic Review 57:347-359.3. Libecap, G. 1989. Contracting for Property Rights. Cambridge University Press.G. Liability Rules1. * Segerson, K. 1995. Liability and penalty structures in policy design. In The Handbook ofEnvironmental Economics, D. Bromley (ed.). Oxford: Basil Blackwell.2. Menell, P. 1991. The limitations of legal institutions for addressing environmental risks. Journalof Economic Perspectives 5: 93-113.H. Tradeable Permits1. * Hanley, N., J.F. Shogren and B. White. 1996. Environmental Economics in Theory andPractice. Ch. 5.2. * Baumol, W. and W. Oates. The Theory of Environmental Policy. Ch. 12.3. Dales, J.H. 1968. Land, water, and ownership. Canadian Journal of Economics 1: 791-804.4. * Montgomery, D. 1972. Markets in licenses and efficient pollution control programs. Journalof Economic Theory 5: 395-418.45. * Oates, W., P. Portney and A. McGartland. 1989. The net benefits of incentive-basedregulation: a case study of environmental standard setting. American Economic Review 79:1233-1242.6. * Carlson, C., D. Burtraw, M. Cropper and K. Palmer. 2000. Sulfur dioxide control byelectric utilities: what are the gains from trade? Journal of Political Economy 108: 1292-1326.7. Hahn, R. 1984. Market power and transferable property rights. Quarterly Journal ofEconomics 99: 29-46.8. *C. Kling and J. Rubin. 1997. Bankable permits for the control of environmental pollution.Journal of Public Economics 64: 101-115.9. Rubin, J. 1996. A model of intertemporal emission trading, banking, and borrowing. Journalof Environmental Economics and Management 31: 269-286.10. Ellerman, A.D. et al. 2000. Markets for Clean Air: The U.S. Acid Rain Program. NewYork: Cambridge University Press.I. Political Economy and Environmental Policy1. * Buchanan, J. and G. Tullock. 1975. Polluters’ profits and political response: direct controlversus taxes. American Economic Review 65: 139-147.2. Cropper, M.L. 2000. Has economic research answered the needs of environmental policy?Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 39(3): 328-350.3. Hahn, R. 2000. The impacts of economics on environmental policy. Journal ofEnvironmental Economics and Management 39(3): 375-399.4. * Cropper, M. W. Evans, S. Berardi, M. Ducla-Soares and P. Portney. 1992. TheDeterminants of Pesticide Regulation: A Statistical Analysis of EPA Decision-making. Journal of Political Economy 100: 175-197.5. * Metrick, A. and M. L. Weitzman. 1994. Patterns of behavior in endangered speciespreservation. Land Economics 72(1): 1-16.6. Hamilton, J. 1993. Politics and social costs: estimating the impact of collective action onhazardous waste facilities. Rand Journal of Economics: 101-125.III. Externalities and Environmental Policy 2: Asymmetric InformationA. Optimal Regulation with Asymmetric Information1. * Baumol and Oates. 1988. The Theory of Environmental Policy. Ch 5, 13.2. * Mas-Colell, A., M. Whinston and J. Green. 1995. Microeconomic Theory. Ch. 14.3. Laffont, J.-J. and J. Tirole. 1993. A Theory of Incentives in Procurement and Regulation.Cambridge: MIT Press. Ch. 1.4. * Weitzman, M. 1974. Prices vs. quantities. Review of Economic Studies 41: 477-491.55. * Kwerel, E. 1977. To tell the truth: imperfect information and optimal pollution control.Review of Economic Studies 44: 595-601.6. * Lewis, T. 1996. Protecting the environment when costs and benefits are privately known.Rand Journal of Economics 27: 819-847.7. Roberts, M. and M. Spence. 1976. Effluent charges and licenses under uncertainty. Journalof Public Economics 5: 193-208.8. Spulber, D. 1988. Optimal environmental regulation under asymmetric information. Journalof Public Economics 35: 163-181.9. Farrell, J. 1987. Information and the Coase Theorem. Journal of Economic Perspectives 1:113-129.10. * Shavell, S. 1984. A model of the optimal use of liability and safety regulations. RandJournal of Economics 15: 271-280.11. Xepapadeas, A. Environmental policy under imperfect information: incentives and moralhazard. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 20: 113-126.B. Non-point Source Pollution1. * Segerson, K. 1988. Uncertainty and incentives for non-point pollution control. Journal ofEnvironmental Economics and Management 15: 87-98.2. Holmstrom, B. 1982. Moral hazard in teams. Bell Journal of Economics 13: 324-340.3. Cabe, R. and J. Herriges. 1992. The regulation of non-point source pollution under imperfectand asymmetric information. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 22:134-146.4. Shortle, J.S., R.D. Horan, and D.G. Abler. 1997. Research issues in nonpoint source waterpollution control. American Journal of Agricultural Economics: 571-585.C. Monitoring and Enforcement1. Becker, G. 1968. Crime and punishment: an economic approach. Journal of PoliticalEconomy 76: 169-217.2. * Kaplow, L. and S. Shavell. 1994. Optimal law enforcement with self-reporting of behavior.Journal of Political Economy 102: 583-606.3. * Mookherjee, D. and I.P.L. Png. 1994. Marginal deterrence in enforcement of law. Journalof Political Economy 102: 1039-1066.4. Harrington, W. 1988. Enforcement leverage when penalties are restricted. Journal of PublicEconomics 37: 29-53.5. * Swierzbinski, J.E. 1994. Guilty until proven innocent - regulation with costly and limitedenforcement. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 27: 127-146.6. Malik, A. 1993. Self-reporting and the design of policies for regulating stochastic pollution.Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 24: 241-257.67. * Polasky, S. and H. Doremus. 1998. When the truth hurts: endangered species policy onprivate land with incomplete information. Journal of Environmental Economics andManagement 35: 22-47.D. R&D and Environmental Regulation1. Jaffe, A.B., R.G. Newell and R.N. Stavins. 2001. Technological change and the environment.In The Handbook of Environmental Economics, K-G Maler and J. Vincent (eds.).Amsterdam: North Holland/Elsevier Science.2. * Milliman, S.R. and R. Prince. 1989. Firm incentives to promote technological change inpollution control. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 16: 52-57.3. * Laffont, J.-J. and J. Tirole. 1996. Pollution permits and compliance strategies. Journal ofPublic Economics 62: 85-125.4. * Laffont, J.-J. and J. Tirole. 1996. Pollution permits and environmental innovation. Journalof Public Economics 62: 127-140.5. * Jaffe, A.B. and R.N. Stavins. 1995. Dynamic incentives of environmental regulations: theeffect of alternative policy instruments of technological diffusion. Journal of EnvironmentalEconomics and Management 29: S43-S63.IV. Measuring Benefits and Costs of Environmental ImprovementA. Issues in Non-Market Valuation1. * Hanley, N., J.F. Shogren and B. White. 1996. Environmental Economics in Theory andPractice. Ch. 12.2. Krutilla, J.V. 1967. Conservation reconsidered. American Economic Review 57: 777-786.3. Smith, V.K. 1997. Pricing what is priceless: a status report on pricing non-market valuation ofenvironmental resources. In International Yearbook of Environmental and ResourceEconomics 1997/1998, H. Folmer and T. Tietenberg (eds.). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.4. Bockstael, N.B. and K.E. McConnell. 1993. Public goods as characteristics of nonmarketcommodities. Economic Journal 103: 1244-1257.B. Benefit-Cost Analysis1. * Dorfman, R. 1993. An introduction to benefit-cost analysis. In Economics of theEnvironment: Selected Readings, R. Dorfman and N.S. Dorfman (eds.). New York: Norton.2. * Arrow, K.J. et al. 1996. Is there a role for benefit-cost analysis in environmental, health, andsafety regulation? Science 272: 221-222.3. * Graham, D. 1981. Cost-benefit analysis under uncertainty. American Economic Review71: 715-725.4. Graham, D. 1992. Public expenditure under uncertainty: the net-benefits criteria. AmericanEconomic Review 82: 822-846.7C. Cost of Environmental Regulation1. * Jaffe, A.B., S.R. Peterson, P.R. Portney and R. Stavins. 1995. Environmental regulation andthe competitiveness of U.S. manufacturing. Journal of Economic Literature 33: 132-163.2. * Hazilla, M. and R.J. Kopp. 1990. The social cost of environmental quality regulations: ageneral equilibrium analysis. Journal of Political Economy: 853-873.3. * Porter, M.E. and C. van der Linde. 1995. Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. Journal of Economic Perspectives 9: 97-118.4. * Palmer, K., W.E. Oates and P.R. Portney. 1995. Tightening environmental standards: thebenefit-cost or the no-cost paradigm? Journal of Economic Perspectives 9: 119-132.D. Principles of Welfare Change Measurement1. * Johansson, P.-O. 1987. The Economic Theory and Measurement of EnvironmentalBenefits. New York: Cambridge University Press. Ch. 3-5.2. * Freeman, A.M. 1993. The Measurement of Environmental and Resource Values. Ch. 3-4.3. Willig, R. 1976. Consumer’s surplus without apology. American Economic Review 66: 589-597.4. Hausman, J. 1981. Exact consumer’s surplus and deadweight loss. American EconomicReview 71: 662-676.5. Morey, E. 1984. Confuser surplus. American Economic Review 74: 163-173.6. * Randall, A. and J.R. Stoll. 1980. Consumer's surplus in commodity space. AmericanEconomic Review 70: 449-455.7. * Hanemann, M. 1991. Willingness to pay and willingness to accept: how much can theydiffer? American Economic Review 81: 635-648.V. Revealed Preference MethodsA. Hedonic Models1. * Freeman, A.M. 1993. The Measurement of Environmental and Resource Values:Theory and Methods. Washington, DC: Resources for the Future. Ch.11-12.2. Rosen, H. 1974. Hedonic prices and implicit markets: product differentiation in purecompetition. Journal of Political Economy 82: 34-55.3. * Harrison, D. and D. Rubinfeld. 1978. Hedonic housing prices and the demand for clean air.Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 5: 81-102.4. * Smith, V.K. and J.-C. Huang. 1995. Can markets value air quality? A meta-analysis ofhedonic property value models. Journal of Political Economy 103: 209-227.85. Roback, J. 1982. Wages, rents, and the quality of life. Journal of Political Economy 90:1257-1278.6. * Bartik, T. 1987. The estimation of demand parameters in hedonic price models. Journal ofPolitical Economy 95: 81-88.7. Mahan, B., S. Polasky and R.M. Adams. 2000. Valuing urban wetlands: a property priceapproach. Land Economics 76: 100-113.B. Travel Cost1. * Freeman, A.M. 1993. The Measurement of Environmental and Resource Values:Theory and Methods. Washington, DC: Resources for the Future. Ch.13.2. * Bockstael, N., I. Strand and W. Hanemann. 1987. Time and the recreation demand model.American Journal of Agricultural Economics 69: 293-302.3. * Bockstael, N., M. Hanemann and C. Kling. 1987. Modeling recreational demand in amultiple site framework. Water Resources Research 23: 951-960.4. * Morey, E.R., R.D. Rowe and M. Watson. 1993. A repeated nested logit model of Atlanticsalmon fishing. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 75: 578-593.5. Kling, C.L. and C.J. Thompson. 1996. The implications of model specification for welfareestimation. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 78: 103-114.VI. Stated Preference MethodsA. Contingent Valuation1. * Freeman, A.M. 1993. The Measurement of Environmental and Resource Values:Theory and Methods. Washington, DC: Resources for the Future. Ch. 5-6.2. Arrow, K.J., R. Solow, P. Portney, E. Leamer, R. Radner, and H. Schuman. 1993. Report ofthe NOAA panel on contingent valuation. Federal Register 58: 4601-4614.3. * Portney, P.R. 1994.The contingent valuation debate: why economists should care. Journalof Economic Perspectives 8: 3-18.4. * Hanemann, W.M. 1994. Contingent valuation and economics. Journal of EconomicPerspectives 8: 19-44.5. * Diamond, P. and J. Hausman. 1994. Contingent valuation: is some number better than nonumber? Journal of Economic Perspectives 8: 45-64.6. Kahneman, D. and J.L. Knetsch. 1992. Valuing public goods: the purchase of moralsatisfaction. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 22: 57-70.7. Harrison, G.W. 1992. Valuing public goods with the contingent valuation method: a critique ofKahneman and Knetsch. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 23: 248-257.8. Smith, V.K. 1992. Arbitrary values, good causes, and premature verdicts. Journal ofEnvironmental Economics and Management 22: 71-89.99. * Smith, V.K. and L.L. Osborne. 1996. Do contingent valuation estimates pass a “scope”test? A meta-analysis. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 31: 287-301.B. Comparing or Combining Stated and Revealed Preference Methods1. * Brookshire, D. and D. Coursey. 1987. Measuring the value of a public good: an empiricalcomparison of elicitation methods. American Economic Review 77: 4554-556.2. * Cummings, R.G., S. Elliott, G.W. Harrison and J. Murphy. 1997. Are hypothetical referendaincentive compatible? Journal of Political Economy 105: 609-621.3. Cummings, R.G., G.W. Harrison and E.E. Rutstrom. 1995. Homegrown values andhypothetical surveys: is the dichotomous choice approach incentive-compatible? AmericanEconomic Review 85: 260-266.4. * Cameron, T.A. 1992. Combining contingent valuation and travel cost data for the valuationof nonmarket goods. Land Economics 68: 302-317.5. * Adamowicz, W., J. Louviere and M. Williams. 1994. Combining revealed and statedpreference methods for valuing environmental amenities. Journal of EnvironmentalEconomics and Management 26: 271-292.VII. Special TopicsA. Biodiversity and Endangered Species1. * Weitzman, M. L. 1998. The Noah’s Ark problem. Econometrica 66: 1279-1298.2. * Solow, A. and S. Polasky. 1994. Measuring biological diversity. Environmental andEcological Statistics 1: 95-1073. * Ando, Amy, Jeffrey Camm, Stephen Polasky and Andrew Solow. 1998. Speciesdistributions, land values and efficient conservation. Science 279: 2126-2128.4. * Montgomery, Claire A., Robert A. Pollak, Kathryn Freemark and Denis White. 1999.Pricing biodiversity. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 38: 1-19.5. * Simpson, R. David, Roger A. Sedjo and John Reid. 1996. Valuing biodiversity for use inpharmaceutical research. Journal of Political Economy 104: 163-185.6. Montgomery, Claire A., Gardner M. Brown, Jr. and Darius M. Adams. 1994. The marginalcost of species preservation: the case of the northern spotted owl. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 26: 111-128.7. Berrens, Robert P., David S. Brookshire, Michael McKee and Christian Schmidt. 1998.Implementing the safe minimum standards approach: two case studies from the U.S.Endangered Species Act. Land Economics 74: 147-161.10B. Climate Change1. *Nordhaus, W.D. 1991. To slow or not to slow – the economics of the greenhouse effect.Economic Journal 101: 920-937.2. Nordhaus, W.D. 1994. Managing the Global Commons: The Economics of ClimateChange. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.3. Schelling, T. 1992. Some economics of global warming. American Economic Review 82: 1-14.4. * Chichilnisky, G. and G. Heal. 1994. Who should abate carbon emissions: an internationalviewpoint. Economics Letters 44: 443-449.5. The Energy Journal, May 1999. Special issue on the costs of the Kyoto Protocol.6. * Goulder, L.H. and K. Mathai. 2000. Optimal CO2 abatement in the presence of inducedtechnical change. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 39: 1-38.7. * Chakravorty, U., J. Roumasset and K. Tse. 1997. Endogenous substitution among energyresources and global warming. Journal of Political Economy 105: 1201-1234.C. Trade and Environment1. * Hanley, N., J.F. Shogren and B. White. 1996. Environmental Economics in Theory andPractice. Ch.6.2. * Baumol and Oates. 1988. The Theory of Environmental Policy, Ch. 16.3. * Markusen, J.R. 1975. International externalities and optimal tax structures. Journal ofInternational Economics 5: 15-29.4. * Copeland, B. and M. Taylor. 1995. Trade and transboundary pollution. AmericanEconomic Review 85: 716-737.5. Copeland, B. and M. Taylor. 1994. North-South trade and the environment. QuarterlyJournal of Economics 109: 755-87.6. Chichilnisky, G. 1994. North-South trade and the global environment. American EconomicReview 84: 851-874.7. * Lopez, R. 1994. The environment as a factor of production – the effects of growth and tradeliberalization. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 27: 163-184.D. Growth, Development and Environmental Quality1. * Arrow, K.J. et al. 1995. Economic growth, carrying capacity and the environment. Science269: 520-521.2. * Grossman, G. and A. Kreuger. 1995. Economic growth and the environment. QuarterlyJournal of Economics 110: 352-377.3. * Selden, T. and D. Song. 1994. Environmental quality and development: is there a KuznetsCurve for air pollution emissions? Journal of Environmental Economics and Management27: 147-162.114. * Selden, T. and D. Song. 1995. Neoclassical growth, the J Curve for abatement, and theinverted U curve for Pollution. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 29: 162-169.5. Holtz-Eakin, D. and T. Selden. 1995. Stoking the Fires? CO2 emissions and economicgrowth. Journal of Public Economics 57: 85-101.6. * Stokey, N.L. 1998. Are there limits to growth? International Economic Review 39: 1-31.7. Environment and Development Economics 2(4), 1997. Special issue on the environmentalKuznets Curve.12。

产权学派与新制度学派译文集

十二、弗农· W.拉坦:《诱致性制度变迁理论》

十三、林毅夫:《关于制度变迁的经济学理论:诱致性变迁与 强制性变迁》

3

一、社会成本问题

内容概述

——科斯

一、有待分析的问题 提出典型例子:工厂对居民的烟尘污染问题?用庇古《福利经济学》 解释:赔偿、征税或责令工厂迁出。科斯认为这些办法并不合适,需进一步分析。 二、问题的交互性质 允许甲损害乙,还是允许乙损害甲,问题具有交互性,处理这个问题要全面权衡利害 关系,必须从总体的和边际的角度看待这一问题。 三、对损害负有责任的定价制度 举例养牛者对农夫所造成的损害承担责任。要么养牛者少养牛,要么多养牛但支付 农夫赔偿,要么养牛者修栅栏,具体做法要视成本而定。 四、对损害不负责任的定价制度 仍以养牛者和农夫为例,由农夫承担责任。要么农夫放弃耕种,要么农夫支付给养 牛者一笔钱让其减少养牛数,要么农夫修栅栏,具体做法要视成本而定。双方交易的 结果是最终利润最大化,资源配置最优化。

——阿尔钦

德姆塞茨

16

二、生产、信息费用与经济组织

2 少偷懒行为:根据需要选择企业类型

②、社会主义企业——工会

•在某些国家,由于政治因素和不同的经济体制,企业由雇员们 在所有人都参与分享剩余的严格意义上拥有。也就是说,原本 的监督人在这个团队中并不拥有对剩余所有的索取权,而更多 的只是一份简单而无激励的“监督”工作。在这种体制下的监 督人,不免会因为自己做与不做都没有区别,而产生了偷懒动 机。但是,任何一个人都明白这种心态的存在,也知道经理很 可能就是整个团队中最爱偷懒的一个人。在这个时候,为了尽 可能地减少这种偷懒行为,一个全新的概念和组织孕育而生— —工会。工人们为了维护自身的权益,他们雇佣了一个专门帮 助监督雇主的人——工会的管理机构。

美国财产法

《美国财产法》第一章序言1.1 Introduction牛津大学比较法教授Lawson(劳森)曾说:财产法(Property law)不仅是我们法律中最好的一部分,而且它的主要原则和结构也优越于其它国家关于这个领域的法律。

所以学习美国法律,Property law是一门必修的的课程,另外,它也是美国各州律师资格考试的必考科目之一。

在开始这门课之前,还是先让我们来看看Blackacre这个词。

1.2 BlackacreBlackacre这个词在一些美国财产法的著作里经常看到,但在常用的英汉法律词典里却找不到它的译义,有学者将它直译"黑土地",其实Blackacre是一个虚构的(hypothetical)概念,代表财产权的一种标的物:某一块土地或某一栋房屋。

法学教授们在课堂上讨论与不动产有关的问题,需要假设一个案例时就会经常用到它,比如:A occupies Blackacre under a lease from B.另外,教授们如果虚构某一土地为Blackacre,还想虚构另一块土地,那另一块土地就称之为Whiteacre.Black's law dictionary 对Blackacre解释如下:A fictitious tract of land used in legal discourse to discuss real-property issues. When another tract of land is needed in a hypothetical, it is often termed "whiteacre."Note: 美国财产法大量地使用一些像Blackacre之类的专业术语,要理解美国财产法,就必须掌握这些财产法的专业词汇,美国学生也得如此,我们编写这本小册子就是想提供一些重要的词汇,读者通过这些词汇和对其上下文的理解,可以对美国财产法有一个全面的了解。

公司产权理论

科斯定理(Ⅰ、Ⅱ)

1966年,Stigler 定理Ⅰ:如果定价制度的运行毫无成本, 最终结果(产值最大化)是不受法律状 况影响的。 定理Ⅱ:在存在交易费用(交易费用为 正)的情况下,法律或产权制度对经济 制度的运行效率起着极为重要的作用。

科斯定理的意义

社团产权是部分人共同拥有的产权 其特点如下: (1)在社团内部无排他性; (2)对社会外部具有排他性; (3)社团成员取得社团产权须支付一定费 用或具备一定条件; (4)社团产权是一个不可分割的整体; (5)社团产权的转让受到限制。

公司产权

又称法人产权,指公司产权主体所拥有的各项权 能。是介于私有产权与社团产权之间的一种产权。 其特点是: (1)产权主体明确:所有者、公司法人和经营者 (2)产权边界清晰: 所有者拥有股权,这是一种“虚拟”状态的股份; 公司法人拥有法人财产权,即实际的占有权、使 用权、处置权和收益权,同时承担相应的责任; 经营者则拥有对公司资产的经营权。

国有产权

国有产权指产权主体为政府的产权。中央 政府是国有产权的真正主体,而地方政府 在一定地域和一定权限内拥有国有产权 其特点是: ( 1 )排他性:未经政府授权,任何法人和 自然人无权要求分享国有产权; (2)不可分割性; (3)不可转让性。如已转让,则不属于国 有产权。

产权的特征

可分解性:产权是可以细分的,产权的细分 增加了资源配置的灵活性和效率。 排他性:就是产权的独占性与垄断性,是甲 的,就不可能是乙的。排他性的基础是产 权的界定是明晰的。 可让渡性:可交易或转让的特性。如产权的 全部权利的永久让渡;产权的部分权利在 一定时期内的让渡。

2、Theory of Team Production

Team Production

产权理论

二、 产权的基本属性

1、排他性:能够独立行使,具有都特定权利的垄断性。 存在排他成本,当其低于排他的可能性收入时,排他 才是必要的。 排他必须可能:有对财产权利独占和保护的能力或条 件——能够支付排他成本;存在对产权进行保护的公 共性保护或服务。 为了降低排他成本,多少会容忍一定程度的产权模糊。 2、有限性:一是产权之间有清晰的界限——否则导致产 权纠纷;二是任何产权都限定在一定的范围——数量、 时间、空间的限度。

在产权制度起源之后,任何契约的交易都是在既有 的交易环境下进行的。只有交易当事人知道了他自 己的基本权利之后,或产权界定清楚之后,人们才 知道哪些权利可以进入交易,哪些权利不可以进入 交易,在交易过程中如何来协调当事人之间的相互 利益关系。从这个意义上说,产权制度是契约交易 的前提。因为,在法律层次上清楚地界定产权可以 将成本和收益的外部效应内部化,使经济当事人承 担他应该承担的成本,获得他应该获得的收益,而 且可以减少谈判对象,降低谈判费用。因此,产权 制度的建立和发展又便利了人与人之间的交易,推 动了经济的发展。由此可见,交易何以能进行?交 易只有在既有的产权制度下才得以进行。既有的产 权制度是一切交易发生的基本前提。

3

案例3 一个医生发现食品加工厂附近居民很多,于 是就在离食品加工厂不远处开了一家私人诊 所。当开始营业时,医生发现食品厂的噪音 很大,影响他使用听诊器诊断,也不能集中 精力工作。于是医生提出起诉,要求食品厂 禁止使用带噪音的机械设备。法院接受诉讼, 并支持了医生的要求。

4

案例4 农夫与养牛人在毗邻的土地上同时经营, 农夫种麦子,养牛人养牛。麦田与牧场之间 没有栅栏,走失的牛践踏了农夫的麦苗,农 夫受到了损失,要求养牛人赔偿损失,双方 发生争执,农夫告上法院,法院判决养牛人 赔偿农夫的所有损失。