动画外文文献翻译中文字数3000多字

三维建模外文资料翻译3000字

外文资料翻译—原文部分Fundamentals of Human Animation(From Peter Ratner.3D Human Modeling and Animation[M].America:Wiley,2003:243~249)If you are reading this part, then you have most likely finished building your human character, created textures for it, set up its skeleton, made morph targets for facial expressions, and arranged lights around the model. You have then arrived at perhaps the most exciting part of 3-D design, which is animating a character. Up to now the work has been somewhat creative, sometimes tedious, and often difficult.It is very gratifying when all your previous efforts start to pay off as you enliven your character. When animating, there is a creative flow that increases gradually over time. You are now at the phase where you become both the actor and the director of a movie or play.Although animation appears to be a more spontaneous act, it is nevertheless just as challenging, if not more so, than all the previous steps that led up to it. Your animations will look pitiful if you do not understand some basic fundamentals and principles. The following pointers are meant to give you some direction. Feel free to experiment with them. Bend and break the rules whenever you think it will improve the animation.SOME ANIMATION POINTERS1. Try isolating parts. Sometimes this is referred to as animating in stages. Rather than trying to move every part of a body at the same time, concentrate on specific areas. Only one section of the body is moved for the duration of the animation. Then returning to the beginning of the timeline, another section is animated. By successively returning to the beginning and animating a different part each time, the entire process is less confusing.2. Put in some lag time. Different parts of the body should not start and stop at the same time. When an arm swings, the lower arm should follow a few frames after that. The hand swings after the lower arm. It is like a chain reaction that works its way through the entire length of the limb.3. Nothing ever comes to a total stop. In life, only machines appear to come to a dead stop. Muscles, tendons, force, and gravity all affect the movement of a human. You can prove this to yourself. Try punching the air with a full extension. Notice that your fist has a bounce at the end. If a part comes to a stop such as a motion hold, keyframe it once and then again after three to eight or more keyframes. Your motion graph will then have a curve between the two identical keyframes. This will make the part appear to bounce rather than come to a dead stop.4. Add facial expressions and finger movements. Your digital human should exhibit signs of life by blinking and breathing. A blink will normally occur every 60 seconds. A typical blink might be as follows:Frame 60: Both eyes are open.Frame 61: The right eye closes halfway.Frame 62: The right eye closes all the way and the left eye closes halfway.Frame 63: The right eye opens halfway and the left eye closes all the way.Frame 64: The right eye opens all the way and left eye opens halfway.Frame 65: The left eye opens all the way.Closing the eyes at slightly different times makes the blink less mechanical.Changing facial expressions could be just using eye movements to indicate thoughts running through your model's head. The hands will appear stiff if you do not add finger movements. Too many students are too lazy to take the time to add facial and hand movements. If you make the extra effort for these details you will find that your animations become much more interesting.5. What is not seen by the camera is unimportant. If an arm goes through a leg but is not seen in the camera view, then do not bother to fix it. If you want a hand to appear close to the body and the camera view makes it seem to be close even though it is not, then why move it any closer? This also applies to sets. There is no need to build an entire house if all the action takes place in the living room. Consider painting backdrops rather than modeling every part of a scene.6. Use a minimum amount of keyframes. Too many keyframes can make the character appear to move in spastic motions. Sharp, cartoonlike movements are created with closely spaced keyframes. Floaty or soft, languid motions are the result of widely spaced keyframes. An animation will often be a mixture of both. Try to look for ways that will abbreviate the motions. You can retain the essential elements of an animation while reducing the amount of keyframes necessary to create a gesture.7.Anchor a part of the body. Unless your character is in the air, it should have some part of itself locked to the ground. This could be a foot, a hand, or both. Whichever portion is on the ground should be held in the same spot for a number of frames. This prevents unwanted sliding motions. When the model shifts its weight, the foot that touches down becomes locked in place. This is especially true with walking motions.There are a number of ways to lock parts of a model to the ground. One method is to use inverse kinematics. The goal object, which could be a null, automatically locks a foot or hand to the bottom surface. Another method is to manually keyframe the part that needs to be motionless in the same spot. The character or its limbs will have to be moved and rotated, so that foot or hand stays in the same place. If you are using forward kinematics, then this could mean keyframing practically every frame until it is time to unlock that foot or hand.8.A character should exhibit weight. One of the most challenging tasks in 3-D animation is to have a digital actor appear to have weight and mass. You can use several techniques to achieve this. Squash and stretch, or weight and recoil, one of the 12 principles of animation discussed in Chapter 12, is an excellent way to give your character weight.By adding a little bounce to your human, he or she will appear to respond to the force of gravity. For example, if your character jumps up and lands, lift the body up a little after it makes contact. For a heavy character, you can do this several times and have it decrease over time. This will make it seem as if the force of the contact causes the body to vibrate a little.Secondary actions, another one of the 12 principles of animation discussed in Chapter 12, are an important way to show the effects of gravity and mass. Using the previous example of a jumping character, when he or she lands, the belly could bounce up and down, the arms could have some spring to them, the head could tilt forward, and so on.Moving or vibrating the object that comes in contact with the traveling entity is another method for showing the force of mass and gravity. A floor could vibrate or a chair that a person sits in respond to the weight by the seat going down and recovering back up a little. Sometimes an animator will shake the camera to indicate the effects of a force.It is important to take into consideration the size and weight of a character. Heavy objects such as an elephant will spend more time on the ground, while a light character like a rabbit will spendmore time in the air. The hopping rabbit hardly shows the effects of gravity and mass.9. Take the time to act out the action. So often, it is too easy to just sit at the computer and try to solve all the problems of animating a human. Put some life into the performance by getting up and acting out the motions. This will make the character's actions more unique and also solve many timing and positioning problems. The best animators are also excellent actors. A mirror is an indispensable tool for the animator. Videotaping yourself can also be a great help.10. Decide whether to use IK, FK, or a blend of both. Forward kinematics and inverse kinematics have their advantages and disadvantages. FK allows full control over the motions of different body parts. A bone can be rotated and moved to the exact degree and location one desires. The disadvantage to using FK is that when your person has to interact within an environment, simple movements become difficult. Anchoring a foot to the ground so it does not move is challenging because whenever you move the body, the feet slide. A hand resting on a desk has the same problem.IK moves the skeleton with goal objects such as a null. Using IK, the task of anchoring feet and hands becomes very simple. The disadvantage to IK is that a great amount of control is packed together into the goal objects. Certain poses become very difficult to achieve.If the upper body does not require any interaction with its environment, then consider a blend of both IK and FK. IK can be set up for the lower half of the body to anchor the feet to the ground, while FK on the upper body allows greater freedom and precision of movements.Every situation involves a different approach. Use your judgment to decide which setup fits the animation most reliably.11. Add dialogue. It has been said that more than 90% of student animations that are submitted to companies lack dialogue. The few that incorporate speech in their animations make their work highly noticeable. If the animation and dialogue are well done, then those few have a greater advantage than their competition. Companies understand that it takes extra effort and skill tocreate animation with dialogue.When you plan your story, think about creating interaction between characters not only on a physical level but through dialogue as well. There are several techniques, discussed in this chapter, that can be used to make dialogue manageable.12. Use the graph editor to clean up your animations. The graph editor is a useful tool that all 3-D animators should become familiar with. It is basically a representation of all the objects, lights, and cameras in your scene. It keeps track of all their activities and properties.A good use of the graph editor is to clean up morph targets after animating facial expressions. If the default incoming curve in your graph editor is set to arcs rather than straight lines, you will most likely find that sometimes splines in the graph editor will curve below a value of zero. This can yield some unpredictable results. The facial morph targets begin to take on negative values that lead to undesirable facial expressions. Whenever you see a curve bend below a value of zero, select the first keyframe point to the right of the arc and set its curve to linear. A more detailed discussion of the graph editor will be found in a later part of this chapter.ANIMATING IN STAGESAll the various components that can be moved on a human model often become confusing if you try to change them at the same time. The performance quickly deteriorates into a mechanical routine if you try to alter all these parts at the same keyframes. Remember, you are trying to create humanqualities, not robotic ones.Isolating areas to be moved means that you can look for the parts of the body that have motion over time and concentrate on just a few of those. For example, the first thing you can move is the body and legs. When you are done moving them around over the entire timeline, then try rotating the spine. You might do this by moving individual spine bones or using an inverse kinematics chain. Now that you have the body moving around and bending, concentrate on the arms. If you are not using an IK chain to move the arms, hands, and fingers, then rotate the bones for the upper and lower arm. Do not forget the wrist. Finger movements can be animated as one of the last parts. Facial expressions can also be animated last.Example movies showing the same character animated in stages can be viewed on the CD-ROM as CD11-1 AnimationStagesMovies. Some sample images from the animations can also be seen in Figure 11-1. The first movie shows movement only in the body and legs. During the second stage, the spine and head were animated. The third time, the arms were moved. Finally, in the fourth and final stage, facial expressions and finger movements were added.Animating in successive passes should simplify the process. Some final stages would be used to clean up or edit the animation.Sometimes the animation switches from one part of the body leading to another. For example, somewhere during the middle of an animation the upper body begins to lead the lower one. In a case like this, you would then switch from animating the lower body first to moving the upper part before the lower one.The order in which one animates can be a matter of personal choice. Some people may prefer to do facial animation first or perhaps they like to move the arms before anything else. Following is a summary of how someone might animate a human.1. First pass: Move the body and legs.2. Second pass: Move or rotate the spinal bones, neck, and head.3. Third pass: Move or rotate the arms and hands.4. Fourth pass: Animate the fingers.5. Fifth pass: Animate the eyes blinking.6. Sixth pass: Animate eye movements.7. Seventh pass: Animate the mouth, eyebrows, nose, jaw, and cheeks (you can break these up into separate passes).Most movement starts at the hips. Athletes often begin with a windup action in the pelvic area that works its way outward to the extreme parts of the body. This whiplike activity can even be observed in just about any mundane act. It is interesting to note that people who study martial arts learn that most of their power comes from the lower torso.Students are often too lazy to make finger movements a part of their animation. There are several methods that can make the process less time consuming.One way is to create morph targets of the finger positions and then use shape shifting to move the various digits. Each finger is positioned in an open and fistlike closed posture. For example, the sections of the index finger are closed, while the others are left in an open, relaxed position for one morph target. The next morph target would have only the ring finger closed while keeping the others open. During the animation, sliders are then used to open and close the fingers and/or thumbs. Another method to create finger movements is to animate them in both closed and open positions and then save the motion files for each digit. Anytime you animate the same character, you can load the motions into your new scene file. It then becomes a simple process of selecting either the closed or the open position for each finger and thumb and keyframing them wherever you desire.DIALOGUEKnowing how to make your humans talk is a crucial part of character animation. Once you add dialogue, you should notice a livelier performance and a greater personality in your character. At first, dialogue may seem too great a challenge to attempt. Actually, if you follow some simple rules, you will find that adding speech to your animations is not as daunting a task as one would think. The following suggestions should help.DIALOGUE ESSENTIALS1. Look in the mirror. Before animating, use a mirror or a reflective surface such as that on a CD to follow lip movements and facial expressions.2. The eyes, mouth, and brows change the most. The parts of the face that contain the greatest amount of muscle groups are the eyes, brows, and mouth. Therefore, these are the areas that change the most when creating expressions.3. The head constantly moves during dialogue. Animate random head movements, no matter how small, during the entire animation. Involuntary motions of the head make a point without having to state it outright. For example, nodding and shaking the head communicate, respectively, positive and negative responses. Leaning the head forward can show anger, while a downward movement communicates sadness. Move the head to accentuate and emphasize certain statements. Listen to thewords that are stressed and add extra head movements to them.4. Communicate emotions. There are six recognizable universal emotions: sadness, anger, joy, fear, disgust, and surprise. Other, more ambiguous states are pain, sleepiness, passion, physical exertion, shyness, embarrassment, worry, disdain, sternness, skepticism, laughter, yelling, vanity, impatience, and awe.5. Use phonemes and visemes. Phonemes are the individual sounds we hear in speech. Rather than trying to spell out a word, recreate the word as a phoneme. For example, the word computer is phonetically spelled "cumpewtrr." Visemes are the mouth shapes and tongue positions employed during speech. It helps tremendously to draw a chart that recreates speech as phonemes combined with mouth shapes (visemes) above or below a timeline with the frames marked and the sound and volume indicated.6. Never animate behind the dialogue. It is better to make the mouth shapes one or two frames before the dialogue.7. Don't overstate. Realistic facial movements are fairly limited. The mouth does not open that much when talking.8. Blinking is always a part of facial animation. It occurs about every two seconds. Different emotional states affect the rate of blinking. Nervousness increases the rate of blinking, while anger decreases it.9. Move the eyes. To make the character appear to be alive, be sure to add eye motions. About 80% of the time is spent watching the eyes and mouth, while about 20% is focused on the hands and body.10. Breathing should be a part of facial animation. Opening the mouth and moving the head back slightly will show an intake of air, while flaring the nostrils and having the head nod forward a little can show exhalation. Breathing movements should be very subtle and hardly noticeable...外文资料翻译—译文部分人体动画基础(引自Peter Ratner.3D Human Modeling and Animation[M].America:Wiley,2003:243~249)如果你读到了这部分,说明你很可能已构建好了人物角色,为它创建了纹理,建立起了人体骨骼,为面部表情制作了morph修改器并在模型周围安排好了灯光。

关于mg动画的外文文献综述

关于mg动画的外文文献综述随着动画的应用范围不断拓展,许多动画制作工具如 mushrooms 越来越受到关注。

其中,mg动画是一款将gif制作交互化的软件,已经成为了当前最流行的动画工具之一。

那么,我们应该如何使用这款软件呢?本文将从外文文献综述的角度入手,为您详细阐述。

一、mg动画的起源mg动画的诞生始于2012年,当时,葛祥科技开发了一款名为MagicGif的工具,用于裁切gif和PPT工具,并提供gif动态评论和转发功能。

在2014 年,其推出了mg动画软件,用于将GIF制作交互化。

该软件随后在网络上迅速传播,被广泛应用于各个领域。

二、mg动画的制作流程mg动画软件的制作流程很简单。

首先,你需要导入原始GIF放到编辑界面。

然后,你可以在画布上添加各种元素,比如文字、贴纸、边框等。

接下来,你可以选择添加动画效果,并进行调整,比如调整速度和透明度等。

最后,你可以将结果导出并与他人共享。

三、mg动画的应用场景mg动画具有广泛的应用场景。

例如,它可以用于产品演示、营销代理、教育培训、宣传广告等,能够帮助用户快速而专业地制作动画,从而提高工作效率。

mg动画也可用于个人娱乐和交流。

四、mg动画的特点mg动画具有许多特点优势。

首先,它是一款用户友好的动画工具,易学易用,且没有学习曲线。

其次,它具有出色的交互性能,能够为用户带来更好的用户体验。

另外,mg动画还支持批处理,让用户可以一次性处理多个文件,大大节省了时间和精力。

最后,它还拥有丰富的资源库,以及强大的社区支持,为用户提供最新的动画素材和灵感来源。

总的来说,mg动画是一款非常实用的工具,能够帮助用户快速制作出交互式GIF动画。

可以看出,有关mg动画的外文文献综述,都对该软件的优点有详细的介绍,而它的使用也在不断推广和普及。

因此,我们相信,随着时间的推移,mg动画将会在未来变得更加流行和完善,并为用户带来更好的用户体验。

Flash动画外文文献word版本

F l a s h动画外文文献Flash animationIn the modern teaching, the traditional teaching has already cannot satisfy the requirement of modern teaching, the teaching way and teachers etc are put forward higher request, so for the Flash animation courseware development has a very important significance. Flash can not only make the learners to deepen the understanding of the knowledge, improve the learning interest of the students and teachers' teaching efficiency, also can add vivid artistic effect courseware, conduce to the academic knowledge expression and communication. In order to provide students with intuitive experimental process, improve their learning efficiency and flash animation in the teaching application is necessary. This paper to make proteins dialysis animation as an example, introduced simply have strong ability and unique interactive Flash8.0, discusses how to use the Flash8.0 make protein dialysis experimental animation whole process and related matters.What is FlashFlash is an authoring tool that lets designers and developers create presentations, applications, and other content that enables user interaction. Flash projects can include simple animations, video content, complex presentations, applications, and everything in between. In general, individual pieces of content made with Flash are called applications, even though they might only be a basic animation. You can make media-rich Flash applications by including pictures, sound, video, and special effects.Flash is extremely well suited to creating content for delivery over the Internet because its files are very small. Flash achieves this through its extensive use of vector graphics. Vector graphics require significantly less memory and storage space than bitmap graphics because they are represented by mathematical formulas instead of large data sets. Bitmap graphics are larger because each individual pixel in the image requires a separate piece of data to represent it.To build an application in Flash, you create graphics with the Flash drawing tools and import additional media elements into your Flash document. Next, you define how and when you want to use each of those elements to create the application you have in mind.When you author content in Flash, you work in a Flash document file. Flash documents have the file extension .fla. A Flash document has four main parts: The Stage is where your graphics, video, buttons, and so on appear during playback.The Timeline is where you tell Flash when you want the graphics and other elements of your project to appear. You also use the Timeline to specify the layering order of graphics on the Stage. Graphics in higher layers appear on top of graphics in lower layers.The Library panel is where Flash displays a list of the media elements in your Flash document.ActionScript code allows you to add interactivity to the media elements in your document. For example, you can add code that causes a button to display a new image when the user clicks it. You can also use ActionScript to add logic to your applications. Logic enables your application to behave in different ways depending on the user’s actions or other conditions. Flash includes two versions of ActionScript,each suited to an author’s specific needs. For more information about writing ActionScript, see Learning ActionScript 2.0 in Flash in the Help panel.Flash includes many features that make it powerful but easy to use, such as prebuilt drag-and-drop user interface components, built-in behaviors that let you easily add ActionScript to your document, and special effects that you can add to media objects.When you have finished authoring your Flash document, you publish it using the File > Publish command. This creates a compressed version of your file with the extension .swf. You can then play the SWF file in a web browser or as a stand-alone application using Flash Player.What you can do with FlashWith the wide array of features in Flash, you can create many types of applications. The following are some examples of the kinds of applications Flash is capable of generating:Animations These include banner ads, online greeting cards, cartoons, and so on. Many other types of Flash applications include animation elements as well.Games Many games are built with Flash. Games usually combine the animation capabilities of Flash with the logic capabilities of ActionScript.User interfaces Many website designers use Flash to design user interfaces. These include simple navigation bars as well as much more complex interfaces.Flexible messaging areas These are areas in web pages that designers use for displaying information that may change over time. A flexible messaging area (FMA) on a restaurant website might display information about each day’s menu specials.Rich Internet applicationsThese include a wide spectrum of applications that provide a rich user interface for displaying and manipulating remotely stored data over the Internet. A rich Internet application could be a calendar application, a price-finding application, a shopping catalog, an education and testing application, or any other application that presents remote data with a graphically rich interface.Depending on your project and your working style, you may use these steps in a different order. As you become familiar with Flash and its workflows, you will discover a style of working that suits you best.About ActionScript and eventsIn Macromedia Flash Basic 8 and Macromedia Flash Professional 8, ActionScript code is executed when an event occurs: for example, when a movie clip is loaded, when a keyframe on the Timeline is entered, or when the user clicks a button. Events can be triggered either by the user or by the system. Users click mouse buttons and press keys; the system triggers events when specific conditions are met or processes completed (the movie loads, the Timeline reaches a certain frame, a graphic finishes downloading, and so on).When an event occurs, you write an event handler to respond to the event with an action. Understanding when and where events occur will help you to determine how and where you will respond to the event with an action, and which ActionScript tools should be used in each case.Events can be grouped into a number of categories: mouse and keyboard events, which occur when a user interacts with your Flash application via the mouse and keyboard; clip events, which occur within movie clips; and frame events, which occur within frames on the Timeline.Mouse and keyboard eventsA user interacting with your Flash movie or application triggers mouse and keyboard events. For example, when the user rolls over a button, the on (rollOver) event occurs; when a button is clicked, the on (press) event occurs; if a key on the keyboard is pressed, the on (keyPress) event occurs. You can attach scripts to handle these events and add all the interactivity you desire.Clip eventsWithin a movie clip, you may react to a number of clip events that are triggered when the user enters or exits the scene or interacts with the scene using the mouse or keyboard. You might, for example, load an external SWF file or JPG image into the movie clip when the user enters the scene, or allow the user’s mouse movements toreposition elements in the scene.Frame eventsOn a main or movie clip Timeline, a system event occurs when the playhead enters a keyframe—this is known as a frame event. Frame events are useful for triggering actions based on the passage of time (moving through the Timeline) or for interacting with elements that are currently visible on the stage. When you add a script to a keyframe, it is executed when the keyframe is reached during playback. A script attached to a frame is called a frame script.One of the most common uses of frame scripts is to stop the playback when a certain keyframe is reached. This is done with the stop() function. You select a keyframe and then add the stop() function as a script element in the Actions panel.Once you’ve stopped the movie at a certain keyframe, you need to take some action. You could, for example, use a frame script to dynamically update the value of a label, to manage the interaction of elements on the stage, and so on. For more information, see Chapter 5, “Handling Events,” on page #.Organizing ActionScript codeYou may attach scripts to keyframes and to object instances (movie clips, buttons, and other symbols). However, if your ActionScript code is scattered over many keyframes and object instances, debugging your application will be much more difficult. It will also be impossible to share your code between different Flash applications. Therefore, it’s important to follow best practices for coding when youcreate ActionScript in Flash.Rather than attaching your scripts to elements like keyframes, movie clips, and buttons, you should respond to events by calling functions that reside in a central location. One method is to attach embedded ActionScript to the first or second frame of the Timeline whenever possible so you don’t have to search through the FLA file tofind all your code. A common practice is to create a layer called actions and place your ActionScript code there.When you attach all your scripts to individual elements, you’re embedding all your code in the FLA file. If sharing your code between other Flash applications is important to you, use the Script window or your favorite text editor to create an external ActionScript (AS) file.By creating an external file, you make your code more modular and well organized. As your project grows, this convenience becomes much more useful than you might imagine. An external file aids debugging and also source control management if you’re working on a project with other developers.To use the ActionScript code contained in an external AS file, you create a script within the FLA file and then use the #include statement to access the code you’ve stored externally, as shown in the following example:#include "../core/Functions.as"You can also use ActionScript 2.0 to create custom classes. You must store custom classes in external AS files and use import statements in a script to get the classes exported into the SWF file, instead of using #include statements. You can also use components to share code and functionality.About writing scripts to handle eventsEvents can be categorized into two major groups: those that occur on the Timeline (in keyframes) and those that occur on object instances (move clips, buttons, and other symbols). The interactivity of your Flash movie or application can be scattered over the many elements in your project, and you may be tempted to add scripts directly to these elements. However, Macromedia recommends that you do not add scripts directly to these elements (keyframes and objects). Instead, you should respond to events by calling functions that reside in a central location.Using the Actions panel and Script windowTo create scripts that are part of your document, you enter ActionScript directly into the Actions panel. To create external scripts, you can use the Script window (File > New > ActionScript File) or your preferred text editor.When you use the Actions panel or Script window, you are using the ActionScript editor. Both the Actions panel and Script window have the Script pane (which is where you use the ActionScript editor) and the Actions toolbox. However, the Actions panel, and the Flash authoring environment in general, offer a few more code-assistance features than the Script window. Flash offers these features in the Actions panel because they are especially useful in the context of editing ActionScript within a FLA file.Flash 动画在现代教学中,传统的教学已经不能满足现代教学的要求,这对教学方式和教师等都提出了更高的要求,所以对于Flash制作动画课件的研制有着极为重要的意义。

动画论文外文翻译

外文文献翻译2.5.1译文:看电影的艺术1930年代中期,沃尔特·迪斯尼才明确以动画电影娱乐观众的思想,动画片本身才成为放映主角(不再是其他剧情片的搭配)。

于1937年下半年首映的动画片《白雪公主与七个小矮人》为动画片树立了极高的标准,至今任然指导着动画艺术家们。

1940年,这一年作为迪斯尼制片厂的分水岭,诞生了《木偶奇遇记》和《幻想曲>。

这些今天成为经典的作品在接下来的二十年中被追随效仿,产生了一系列广受欢迎的动画娱乐作品。

包括《小飞象》,《灰姑娘》,《爱丽丝漫游仙境》,《彼得·潘》,《小姐与流浪儿》,他们的故事通常源自广为人知的文学故事。

这些影片最不好的地方在于它们似乎越来越面向小观众。

在1966年第四你去死后,他的制片厂继续制作手绘动画影片,但是创作能量衰减,公司转而专注于著作真人是拍电影。

然而1989年,对于我们所有孩子来说,动画《小美人鱼》赋予了迪士尼新的生命活力(就像animation这个词本身的定义一样——使有生命活力),从该片开始,出现了一系列令人惊叹不已的音乐动画片。

两年后,《美女与野兽》问世,塔尔在制作过程中利用了计算机作为传统手绘技术的辅助手段,这部影片获得了奥斯卡最佳电影奖提名,它是第一部获此殊荣的动画片。

更好的还在后面,就想着两部影片一样,后面紧接着出现的众多优秀作品——包括《狮子王》,《阿拉丁》,《花木兰》——延续了迪士尼的经典传统:大胆醒目的视觉效果、精致的剧本,以及我们在所有伟大的电影中,不管是动画还是其他类型中都能找到的普适性主题和出乎意料之处。

迪士尼的新版《幻想曲》,又被称为《幻想曲2000》,把原版中的部分片段与新的创作部分糅合在一起。

(而且,按照迪士尼管理层的说法,该片是首部在IMAX巨幕影院首映的剧情长片。

)亨利·塞利克执导了蒂姆·波顿出品的两部影片,即《圣诞惊魂夜》和《飞天巨桃历险记》——前者是一部完全原创的定格动画,影片画面有时渗透着无限的恐惧,后者改编自罗纳德·达尔的畅销儿童书,该影片以真人实景拍摄开始。

影视视频剪辑外文文献翻译字数3000多

影视视频剪辑外文文献翻译字数3000多XXX final product。

The article also examines the XXX editing practices。

including the use of digital tools and are。

Finally。

the article looks at the XXX.nVideo editing is an essential aspect of the film and n n process。

It XXX final product。

The editing process can make or break afilm or n show。

as it can greatly impact the XXX。

In this article。

we will XXX to the final product.The XXX EditingXXX。

It allows filmmakers to shape the story。

control the pace。

and create a XXX。

a XXX's job is to take the raw footage and turn it into a XXX audience。

They must make ns about what footage to include。

what to cut。

and how to arrange it to createthe desired effect.Technology and EditingTechnology has XXX。

Digital tools and are have made the process faster。

more efficient。

and XXX。

collaborate with others in real-time。

动画设计电视广告论文中英文外文翻译文献

动画设计电视广告论文中英文外文翻译文献Copywriting for Visual MediaBefore XXX。

and film advertising were the primary meansof advertising。

Even today。

local ads can still be seen in some movie theaters before the start of the program。

The practice of selling time een programming for commercial messages has e a standard in the visual media XXX format for delivering shortvisual commercial messages very XXX.⑵Types of Ads and PSAsThere are us types of ads and public service announcements (PSAs) that XXX ads。

service ads。

and XXX a specific product。

while service ads promote a specific service。

nal ads。

on theother hand。

promote an entire company or industry。

PSAs。

on the other hand。

are mercial messages that aim to educate andinform the public on important issues such as health。

safety。

and social XXX.⑶The Power of Visual AdvertisingXXX。

The use of colors。

外文文献—动画

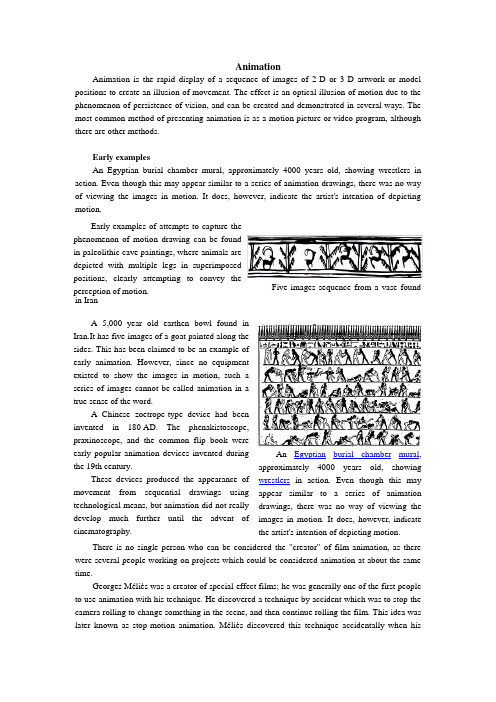

AnimationAnimation is the rapid display of a sequence of images of 2-D or 3-D artwork or model positions to create an illusion of movement. The effect is an optical illusion of motion due to the phenomenon of persistence of vision, and can be created and demonstrated in several ways. The most common method of presenting animation is as a motion picture or video program, although there are other methods.Early examplesAn Egyptian burial chamber mural, approximately 4000 years old, showing wrestlers in action. Even though this may appear similar to a series of animation drawings, there was no way of viewing the images in motion. It does, however, indicate the artist's intention of depicting motion.Five images sequence from a vase foundin IranThere is no single person who can be considered the "creator" of film animation, as there were several people working on projects which could be considered animation at about the same time.Georges Méliès was a creator of special-effect films; he was generally one of the first people to use animation with his technique. He discovered a technique by accident which was to stop the camera rolling to change something in the scene, and then continue rolling the film. This idea was later known as stop-motion animation. Méliès discovered this technique accidentally when his Early examples of attempts to capture the phenomenon of motion drawing can be foundin paleolithic cave paintings, where animals aredepicted with multiple legs in superimposedpositions, clearly attempting to convey theperception of motion.An Egyptian burial chamber mural , approximately 4000 years old, showing wrestlers in action. Even though this may appear similar to a series of animation drawings, there was no way of viewing the images in motion. It does, however, indicate the artist's intention of depicting motion. A 5,000 year old earthen bowl found inIran.It has five images of a goat painted along thesides. This has been claimed to be an example ofearly animation. However, since no equipmentexisted to show the images in motion, such aseries of images cannot be called animation in atrue sense of the word.A Chinese zoetrope-type device had beeninvented in 180 AD. The phenakistoscope,praxinoscope, and the common flip book were early popular animation devices invented during the 19th century. These devices produced the appearance of movement from sequential drawings using technological means, but animation did not really develop much further until the advent of cinematography.camera broke down while shooting a bus driving by. When he had fixed the camera, a hearse happened to be passing by just as Méliès restarted rolling the film, his end result was that he had managed to make a bus transform into a hearse. This was just one of the great contributors to animation in the early years.The earliest surviving stop-motion advertising film was an English short by Arthur Melbourne-Cooper called Matches: An Appeal (1899). Developed for the Bryant and May Matchsticks company, it involved stop-motion animation of wired-together matches writing a patriotic call to action on a blackboard.J. Stuart Blackton was possibly the first American film-maker to use the techniques of stop-motion and hand-drawn animation. Introduced to film-making by Edison, he pioneered these concepts at the turn of the 20th century, with his first copyrighted work dated 1900. Several of his films, among them The Enchanted Drawing (1900) and Humorous Phases of Funny Faces (1906) were film versions of Blackton's "lightning artist" routine, and utilized modified versions of Méliès' early stop-motion techniques to make a series of blackboard drawings appear to move and reshape themselves. 'Humorous Phases of Funny Faces' is regularly cited as the first true animated film, and Blackton is considered the first true animator.Fantasmagorie by Emile Cohl, 1908 Following the successes of Blackton and Cohl, many other artists began experimenting with animation. One such artist was Winsor McCay, a successful newspaper cartoonist, who created detailed animations that required a team of artists and painstaking attention for detail. Each frame was drawn on paper; which invariably required backgrounds and characters to be redrawn and animated. Among McCay's most noted films are Little Nemo (1911), Gertie the Dinosaur (1914) and The Sinking of the Lusitania (1918).The production of animated short films, typically referred to as "cartoons", became an industry of its own during the 1910s, and cartoon shorts were produced to be shown in movie theaters. The most successful early animation producer was John Randolph Bray, who, along with animator Earl Hurd, patented the cel animation process which dominated the animation industry for the rest of the decade.El Apóstol (Spanish: "The Apostle") was a 1917 Argentine animated film utilizing cutout animation, and the world's first animated feature film.Another French artist, Émile Cohl, begandrawing cartoon strips and created a film in1908 called Fantasmagorie. The film largelyconsisted of a stick figure moving about andencountering all manner of morphing objects,such as a wine bottle that transforms into aflower. There were also sections of live actionwhere the animator’s hands would enter thescene. The film was created by drawing eachframe on paper and then shooting each frameonto negative film, which gave the picture ablackboard look. This makes Fantasmagorie thefirst animated film created using what came tobe known as traditional (hand-drawn)animation.Traditional animationThe traditional cel animation process became obsolete by the beginning of the 21st century. Today, animators' drawings and the backgrounds are either scanned into or drawn directly into a computer system. Various software programs are used to color the drawings and simulate camera movement and effects. The final animated piece is output to one of several delivery media, including traditional 35 mm film and newer media such as digital video. The "look" of traditional cel animation is still preserved, and the character animators' work has remained essentially the same over the past 70 years. Some animation producers have used the term "tradigital" to describe cel animation which makes extensive use of computer technology.Examples of traditionally animated feature films include Pinocchio (United States, 1940), Animal Farm (United Kingdom, 1954), and Akira (Japan, 1988). Traditional animated films which were produced with the aid of computer technology include The Lion King (US, 1994) Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi (Spirited Away) (Japan, 2001), and Les Triplettes de Belleville (France, 2003).Full animation refers to the process of producing high-quality traditionally animated films, which regularly use detailed drawings and plausible movement. Fully animated films can be done in a variety of styles, from more realistically animated works such as those produced by the Walt Disney studio (Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin, Lion King) to the more 'cartoony' styles of those produced by the Warner Bros. animation studio. Many of the Disney animated features are examples of full animation, as are non-Disney works such as The Secret of NIMH (US, 1982), The Iron Giant (US, 1999), and Nocturna (Spain, 2007).Limited animation involves the use of less detailed and/or more stylized drawings and methods of movement. Pioneered by the artists at the American studio United Productions of America, limited animation can be used as a method of stylized artistic expression, as in Gerald McBoing Boing (US, 1951), Yellow Submarine (UK, 1968), and much of the anime produced in Japan. Its primary use, however, has been in producing cost-effective animated content for media such as television (the work of Hanna-Barbera, Filmation, and other TV animation studios) and An example of traditional animation, a horse animated by rotoscoping from Eadweard Muybridge 's 19th century photos Traditional animation (also called cel animationor hand-drawn animation) was the process used formost animated films of the 20th century. Theindividual frames of a traditionally animated film arephotographs of drawings, which are first drawn onpaper. To create the illusion of movement, eachdrawing differs slightly from the one before it. Theanimators' drawings are traced or photocopied ontotransparent acetate sheets called cels, which are filledin with paints in assigned colors or tones on the sideopposite the line drawings. The completed character cels are photographed one-by-one onto motion picture film against a painted background by a rostrum camera.later the Internet (web cartoons)。

3d动画制作中英文对照外文翻译文献

3d动画制作中英文对照外文翻译文献预览说明:预览图片所展示的格式为文档的源格式展示,下载源文件没有水印,内容可编辑和复制中英文对照外文翻译文献(文档含英文原文和中文翻译)Spin: A 3D Interface for Cooperative WorkAbstract: in this paper, we present a three-dimensional user interface for synchronous co-operative work, Spin, which has been designed for multi-user synchronous real-time applications to be used in, for example, meetings and learning situations. Spin is based on a new metaphor of virtual workspace. We have designed an interface, for an office environment, which recreates the three-dimensional elements needed during a meeting and increases the user's scope of interaction. In order to accomplish these objectives, animation and three-dimensional interaction in real time are used to enhance the feeling of collaboration within the three-dimensional workspace. Spin is designed to maintain a maximum amount of information visible. The workspace is created using artificial geometry - as opposed to true three-dimensional geometry - and spatial distortion, a technique that allows all documents and information to be displayed simultaneously while centering the user's focus of attention. Users interact with each other via their respective clones, which are three-dimensional representations displayed in each user's interface, and are animated with user action on shared documents. An appropriate object manipulation system (direct manipulation, 3D devices and specific interaction metaphors) is used to point out and manipulate 3D documents.Keywords: Synchronous CSCW; CVE; Avatar; Clone; Three-dimensional interface; 3D interactionIntroductionTechnological progress has given us access to fields that previously only existed in our imaginations. Progress made in computers and in communication networks has benefited computer-supported cooperative work (CSCW), an area where many technical and human obstacles need to be overcome before it can be considered as a valid tool. We need to bear in mind the difficulties inherent in cooperative work and in the user's ability to perceive a third dimension.The Shortcomings of Two- Dimensional InterfacesCurrent WIMP (windows icon mouse pointer) office interfaces have considerable ergonomic limitations [1].(a) Two-dimensional space does not display large amounts of data adequately. When it comes to displaying massive amounts of data, 2D displays have shortcomings such as window overlap and the need for iconic representation of information [2]. Moreover, the simultaneous display of too many windows (the key symptom of Windowitis) can be stressful for users [3].(b) WIMP applications are indistinguishable from one another; leading to confusion. Window dis- play systems, be they XII or Windows, do not make the distinction between applications, con- sequently, information is displayed in identical windows regardless of the user's task.(c) 2D applications cannot provide realistic rep- resentation. Until recently, network technology only allowed for asynchronous sessions (electronic mail for example); and because the hardware being used was not powerful enough, interfaces could only use 2D representations of the workspace.Metaphors in this type of environment do not resemble the real space; consequently, it is difficult for the user to move around within a simulated 3D space.(d) 2D applications provide poor graphical user representations. As windows are indistinguish- able and there is no graphical relation between windows, it is difficult to create a visual link between users or between a user and an object when the user's behavior is been displayed [4].(e) 2D applications are not sufficiently immersive, because 2D graphical interaction is not intuitive (proprioception is not exploited) users have difficulties getting and remaining involved in the task at hand.Interfaces: New ScopeSpin is a new interface concept, based on real-time computer animation. Widespread use of 3D graphic cards for personal computers has made real-time animation possible on low-cost computers. The introduction of a new dimension (depth) changes the user's role within the interface, the use of animation is seamless and therefore lightens the user's cognitive load. With appropriate input devices, the user now has new ways of navigating in, interacting with and organizing his workspace. Since 1995, IBM has been working on RealPlaces [5], a 3D interface project. It was developed to study the convergence between business applications and virtual reality. The user environment in RealPlaces is divided into two separate spaces (Fig, 1): ? a 'world view', a 3D model which stores and organizes documents through easy object interaction;a 'work plane', a 2D view of objects with detailed interaction, (what is used in most 2D interfaces).RealPlaces allows for 3D organization of a large number ofobjects. The user can navigatethrough them, and work on a document, which can be viewed and edited in a 2D application that is displayed in the foreground of the 'world'. It solves the problem of 2D documents in a 3D world, although there is still some overlapping of objects. RealPtaces does solve some of the problems common to 2D interfaces but it is not seamless. While it introduces two different dimensions to show documents, the user still has difficulty establishing links between these two dimensions in cases where multi-user activity is being displayed. In our interface, we try to correct the shortcomings of 2D interfaces as IBM did in RealPlaces, and we go a step further, we put forward a solution for problems raised in multi-user cooperation, Spin integrates users into a virtual working place in a manner that imitates reality making cooperation through the use of 3D animation possible. Complex tasks and related data can be represented seamlessly, allowing for a more immersive experience. In this paper we discuss, in the first part, the various concepts inherent in simultaneous distant cooperative work (synchronous CSCW), representation and interaction within a 3D interface. In the second part, we describe our own interface model and how the concepts behind it were developed. We conclude with a description of the various current and impending developments directly related to the prototype and to its assessment.ConceptsWhen designing a 3D interface, several fields need to be taken into consideration. We have already mentioned real-time computer animation and computer-supported cooperative work, which are the backbone of our project. There are also certain fields of the human sciences that have directty contributed to thedevelopment of Spin. Ergon- omics [6], psychology [7] and sociology [8] have broadened our knowIedge of the way in which the user behaves within the interface, both as an individual and as a member of a group.Synchronous Cooperative WorkThe interface must support synchronous cooper- ative work. By this we mean that it must support applications where the users have to communicate in order to make decisions, exchange views or find solutions, as would be the case with tele- conferencing or learning situations. The sense of co-presence is crucial, the user needs to have an immediate feeling that he is with other people; experiments such as Hydra Units [9] and MAJIC [10] have allowed us to isolate some of the aspects that are essential to multimedia interactive meetings.Eye contact." a participant should be able to see that he is being looked at, and should be able to look at someone else. ? Gaze awareness: the user must be able to estab- fish a participant's visual focus of attention. ? Facial expressions: these provide information concerning the participants' reactions, their acquiescence, their annoyance and so on. ? GesCures. ptay an important role in pointing and in 3D interfaces which use a determined set of gestures as commands, and are also used as a means of expressing emotion.Group ActivitySpeech is far from being the sole means of expression during verbal interaction [1 1]. Gestures (voluntary or involuntary) and facial expressions contribute as much information as speech. More- over, collaborative work entails the need to identify other people's points of view as well as their actions [1 2,1 3]. This requires defining the metaphors which witl enable users involvedin collaborative work to understand what other users are doing and to interact withthem. Researchers I1 4] have defined various communication criteria for representing a user in a virtual environment. In DIVE (Distributed Interactive Virtual Environment, see Fig. 2), Benford and Fahl6n lay down rules for each characteristic and apply them to their own system [1 5]. lhey point out the advantages of using a clone (a realistic synthetic 3D representation of a human) to represent the user. With a clone, eye contact (it is possible to guide the eye movements of a clone) as well as gestures and facial expressions can be controlled; this is more difficult to accomplish with video images. tn addition to having a clone, every user must have a telepointer, which is used to designate obiects that can be seen on other users' displays.Task-Oriented InteractionUsers attending a meeting must be abte to work on one or several shared documents, it is therefore preferable to place them in a central position in the user's field of vision, this increases her feeling of participation in a collaborative task. This concept, which consists of positioning the documents so as to focus user attention, was developed in the Xerox Rooms project [1 6]; the underlying principle is to prevent windows from overlapping or becoming too numerous. This is done by classifying them according to specific tasks and placing them in virtual offices so that a singIe window is displayed at any one (given) time. The user needs to have an instance of the interface which is adapted to his role and the way he apprehends things, tn a cooperative work context, the user is physically represented in the interface and has a position relative to the other members of the group.The Conference Table Metaphor NavigationVisually displaying the separation of tasks seems logical - an open and continuous space is not suitable. The concept of 'room', in the visual and in the semantic sense, is frequently encountered in the literature. It is defined as a closed space that has been assigned a single task.A 3D representation of this 'room' is ideal because the user finds himself in a situation that he is familiar with, and the resulting interfaces are friendlier and more intuitive.Perception and Support of Shared AwarenessSome tasks entail focusing attention on a specific issue (when editing a text document) while others call for a more global view of the activity (during a discussion you need an overview of documents and actors). Over a given period, our attention shifts back and forth between these two types of activities [17]. CSCW requires each user to know what is being done, what is being changed, where and by whom. Consequently, the interface has to be able to support shared awareness. Ideally, the user would be able to see everything going on in the room at all times (an everything visible situation). Nonetheless, there are limits to the amount of information that can be simultaneously displayed on a screen. Improvements can be made by drawing on and adopting certain aspects of human perception. Namely, a field of vision with a central zone where images are extremely clear, and a peripheral vision zone, where objects are not well defined, but where movement and other types of change can be perceived.Interactive Computer AnimationInteractive computer animation allows for two things: first, the amount of information displayed can be increased, andsecond, only a small amount of this information can be made legible [18,19]. The remainder of the information continues to be displayed but is less legible (the user only has a rough view of the contents). The use of specific 3D algorithms and interactive animation to display each object enables the user visually to analyse the data quickly and correctly. The interface needs to be seamless. We want to avoid abstract breaks in the continuity of the scene, which would increase the user's cognitive load.We define navigation as changes in the user's point of view. With traditional virtual reality applica- tions, navigation also includes movement in the 3D world. Interaction, on the other hand, refers to how the user acts in the scene: the user manipulates objects without changing his overall point of view of the scene. Navigation and interaction are intrinsically linked; in order to interact with the interface the user has to be able to move within the interface. Unfortunately, the existence of a third dimension creates new problems with positioning and with user orientation; these need to be dealt with in order to avoid disorienting the user [20].Our ModelIn this section, we describe our interface model by expounding the aforementioned concepts, by defining spatial organization, and finally, by explaining how the user works and collaborates with others through the interface.Spatial OrganizationThe WorkspaceWhile certain aspects of our model are related to virtual reality, we have decided that since our model iS aimed at an office environment, the use of cumbersome helmets or gloves is not desirable. Our model's working environment is non-immersive.Frequently, immersive virtual reality environments tack precision and hinder perception: what humans need to perceive to believe in virtual worlds is out of reach of present simulation systems [26]. We try to eliminate many of the gestures linked to natural constraints, (turning pages in a book, for example) and which are not necessary during a meeting. Our workspace has been designed to resolve navigation problems by reducing the number of superfluous gestures which slow down the user. In a maI-life situation, for example, people sitting around a table could not easily read the same document at the same time. To create a simple and convenient workspace, situations are analysed and information which is not indispensable is discarded [27]. We often use interactive computer animation, but we do not abruptly suppress objects and create new icons; consequently, the user no longer has to strive to establish a mental link between two different representations of the same object. Because visual recognition decreases cognitive load, objects are seamlessly animated. We use animation to illustrate all changes in the working environment, i.e. the arrival of a new participant, the telepointer is always animated. There are two basic objects in our workspace: the actors and the artefacts. The actors are representations of the remote users or of artificial assistants. The artefacts are the applications and the interaction tools.The Conference tableThe metaphor used by the interface is the con- ference table. It corresponds to a single activity (our task-oriented interface solves the (b) shortcoming of the 2D interface, see Introduction). This activity is divided spatially and semantically into two parts. The first is asimulated panoramic view on which actors and sharedapplications are displayed. Second, within this view there is a workspace located near the center of the simulated panoramic screen, where the user can easily manipulate a specific document. The actors and the shared applications (2D and 3D) are placed side by side around the table (Fig. 4), and in the interest of comfort, there is one document or actor per 'wail'. As many applications as desired may be placed in a semi-circle so that all of the applications remain visible. The user can adjust the screen so that the focus of her attention is in the center; this type of motion resembles head- turning. The workspace is seamless and intuitive,Fig, 4. Objects placed around our virtual table.And simulates a real meeting where there are several people seated around a table. Participants joining the meeting and additional applications are on an equal footing with those already present. Our metaphor solves the (c) shortcoming of the 2D interface (see Introduction),DistortionIf the number of objects around the table increases, they become too thin to be useful. To resolve this problem we have defined a focus-of-attention zone located in the center of the screen. Documents on either side of this zone are distorted (Fig.5). Distortion is symmetrical in relation to the coordinate frame x=0. Each object is uniformly scaled with the following formula: x'=l-(1-x) '~, O<x<l< bdsfid="116" p=""></x<l<>Where is the deformation factor. When a= 1 the scene is not distorted. When all, points are drawn closer to the edge; this results in centrally positioned objects being stretched out, while those in the periphery are squeezed towards the edge. This distortion is similar to a fish-eye with only one dimension [28].By placing the main document in the centre of the screen and continuing to display all the other documents, our model simulates a human field of vision (with a central zone and a peripheral zone). By reducing the space taken up by less important objects, an 'everything perceivable' situation is obtained and, although objects on the periphery are neither legible nor clear, they are visible and all the information is available on the screen. The number of actors and documents that it is possible to place around the table depends, for the most part, on screen resolution. Our project is designed for small meetings with four people for example (three clones) and a few documents (three for example). Under these conditions, if participants are using 17-inch, 800 pixels screens all six objects are visible, and the system works.Everything VisibleWith this type of distortion, the important applications remain entirely legible, while all others are still part of the environment. When the simulated panoramic screen is reoriented, what disappears on one side immediately reappears on the other. This allows the user to have all applications visible in the interface. In CSCW it is crucial that each and every actor and artefact taking part in a task are displayed on the screen (it solves the (a) shortcoming of 2D interface, see Introduction),A Focus-of-Attention AreaWhen the workspace is distorted in this fashion, the user intuitively places the application on which she is working in the center, in the focus-of- attention area. Clone head movements correspond to changes of the participants' focus of attention area. So, each participant sees theother participants' clones and is able to perceive their headmovements. It gives users the impression of establishing eye contact and reinforces gaze awareness without the use of special devices. When a participant places a private document (one that is only visible on her own interface) in her focus in order to read it or modify it, her clone appears to be looking at the conference table.In front of the simulated panoramic screen is the workspace where the user can place (and enlarge) the applications (2D or 3D) she is working on, she can edit or manipulate them. Navigation is therefore limited to rotating the screen and zooming in on the applications in the focus-of-attention zone.ConclusionIn the future, research needs to be oriented towards clone animation, and the amount of information clones can convey about participant activity. The aim being to increase user collaboration and strengthen the feeling of shared presence. New tools that enable participants to adopt another participant's point of view or to work on another participant's document, need to be introduced. Tools should allow for direct interaction with documents and users. We will continue to develop visual metaphors that will provide more information about shared documents, who is manipulating what, and who has the right to use which documents, etc. In order to make Spin more flexible, it should integrate standards such as VRML 97, MPEG 4, and CORBA. And finally, Spin needs to be extended so that it can be used with bigger groups and more specifically in learning situations.旋转:3D界面的协同工作摘要:本文提出了一种三维用户界面的同步协同工作—旋转,它是为多用户同步实时应用程而设计,可用于例如会议和学习情况。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

文献出处:Amidi, Amid. Cartoon modern: style and design in fifties animation. Chronicle Books, (2006):292-296.原文Cartoon Modern: Style and Design in Fifties AnimationDuring the 1970s,when I was a graduate student in film studies, UPA had a presence in the academy and among cinephiles that it has since lost. With 16mmdistribution thriving and the films only around twenty years old, one could still see Rooty Toot Toot or The Unicorn in the Garden occasionally. In the decades since, UPA and the modern style it was so central in fostering during the 1950s have receded from sight. Of the studio's own films, only Gerald McBoing Boing and its three sequels have a DVD to themselves, and fans must search out sources for old VHScopies of others. Most modernist-influenced films made by the less prominent studios of the era are completely unavailable.UPA remains, however, part of the standard story of film history. Following two decades of rule by the realist-oriented Walt Disney product, the small studio boldly introduced a more abstract, stylized look borrowed from modernism in the fine arts. Other smaller studios followed its lead. John Hubley, sometimes in partnership with his wife Faith, became a canonical name in animation studies. But the trend largely ended after the 1950s. Now its importance is taken for granted. David Bordwell and Ifollowed the pattern by mentioning UPA briefly in our Film History: An Introduction, where we reproduce a black-and-white frame from the Hubleys' Moonbird, taken from a worn 16 mm print. By now, UPA receives a sort of vague respect, while few actually see anything beyond the three or four most famous titles.All this makes Amid Amidi's Cartoon Modern an important book. Published in an attractive horizontal format well suited to displaying film images, it provides hundreds of color drawings, paintings, cels, storyboards, and other design images from 1950s cartoons that display the influence of modern art. Amidi sticks to the U.S. animation industry and does not cover experimental work or formats other than cel animation. The book brings the innovative style of the 1950s back to our attention and provides a veritable archive of rare, mostly unpublished images for teachers, scholars, and enthusiasts. Seeking these out and making sure that they reproduced well, with a good layout and faithful color, was a major accomplishment, and the result is a great service to the field.The collection of images is so attractive, interesting, and informative, that it deserved an equally useful accompanying text. Unfortunately, both in terms of organization and amount of information provided, the book has major textual problems.Amidi states his purpose in the introduction: "to establish the place of 1950s animation design in the great Modernist tradition of the arts". In fact, he barelydiscusses modernism across the arts. He is far more concerned with identifying the individual filmmakers, mainly designers, layout artists, and directors, and with describing how the more pioneering ones among them managed to insert modernist style into the products of what he sees as the old-fashioned, conservative animation industry of the late 1940s. When those filmmakers loved jazz or studied at an art school or expressed an admiration for, say, Fernand Léger, Amidimentions it. He may occasionally refer to Abstract Expressionism or Pop Art, but he relies upon the reader to come to the book already knowing the artistic trends of the twentieth century in both America and Europe. At least twice he mentions that Gyorgy Kepes's important 1944 book The Language of Vision was a key influence on some of the animators inclined toward modernism, but he never explains what they might have derived from it. There is no attempt to suggest how modernist films (e.g. Ballet mécanique, Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari) might have influenced those of Hollywood. On the whole, the other arts and modernism are just assumed, without explanation or specification, to be the context for these filmmakers and films.There seem to me three distinct problems with Amidi's approach: his broad, all-encompassing definition of modernism; his disdain for more traditional animation, especially that of Disney; and his layout of the chapters.For Amidi, "modern" seems to mean everything from Abstract Expressionism to stylized greeting cards. He does not distinguish Cubism from Surrealism or explainwhat strain of modernism he has in mind. He does not explicitly lay out a difference between modernist-influenced animation and animation that is genuinely a part of modern/modernist art. Thus there is no mention of figures like Oskar Fischinger and Mary Ellen Bute, though there seems a possibility that their work influenced the mainstream filmmakers dealt with in the book.This may be because Amidi sees modernism's entry into American animation only secondarily as a matter of direct influences from the other arts. Instead, for him the impulse toward modernism is as a movement away from conventional Hollywood animation. Disney is seen as having during the 1930s and 1940s established realism as the norm, so anything stylized would count as modernism. Amidi ends up talking about a lot of rather cute, appealing films as if they were just as innovative as the work of John Hubley. At one point he devotes ten pages to the output of Playhouse Pictures, a studio that made television ads which Amidi describes as "mainstream modern" because "it was driven by a desire to entertain and less concerned with making graphic statements". I suspect Playhouse rates such extensive coverage largely because its founder, Adrian Woolery, had worked as a production manager and cameraman at UPA. At another point Amidi refers to Warner Bros. animation designer Maurice Noble's work as "accessible modernism".This willingness to cast the modernist net very wide also helps explain why so many conventional looking images from ads are included in the book. Amidi seemsnot to have considered the idea that there could be a normal, everyday stylization that has a broad appeal and might have derived ultimately from some modernist influence that had filtered out, not just into animation, but into the culture more generally.There was such a popularization of modern design in the 1940s and especially the 1950s, and it took place across many areas of American popular culture, including architecture, interior design, and fashion. Thomas Hine has dealt with it in his 1999 book, Populuxe: From Tailfins and TV Dinners to Barbie Dolls and Fallout Shelters. Hines doesn't cover film, but the styles that we can see running through the illustrations in Cartoon Modern have a lot in common with those in Populuxe. Pixar pays homage to them in the design of The Incredibles.Second, Amidi seeks to establish UPA's importance by casting Walt Disney as his villain. Here Disney stands in for the whole pre-1950s Hollywood animation establishment. For the author, anything that isn't modern style is tired and conservative. His chapter on UPA begins with an anecdote designed to drive that point home. It describes the night in 1951 when Gerald McBoing Boing won the Oscar for best animation of 1950, while Disney, not even nominated in the animation category, won for his live-action short, Beaver Valley. UPA president Stephen Bosustow and Disney posed together, with Bosustow described as looking younger and fresher than his older rival. Disney was only ten years older, but to Amidi, Bosustow's "appearance suggests the vitality and freshness of the UPA films whenplaced against the tired Disney films of the early 1950s".That line perplexed me. True, Disney's astonishing output in the late 1930s and early 1940s could hardly be sustained, either in quantity or quality. But even though Cinderella (a relatively lightweight item) and the shorts become largely routine, few would call Peter Pan, Alice in Wonderland, and Lady and the Tramp tired. Indeed, the two Disney features that Amidi later praises for their modernist style, Sleeping Beauty and One Hundred and One Dalmatians, are often taken to mark the beginning of the end of the studio's golden age.In Amidi's view, other animation studios, including Warner Bros., were similarly resistant to modernism on the whole, though there were occasional chinks in their armor. The author selectively praises a few individual innovators. A very brief entry on MGM mentions Tex Avery, mainly for his 1951 short, Symphony in Slang. Warner Bros.' Maurice Noble earns Amidi's praise; he consistently provided designs for Chuck Jones's cartoons, most famously What's Opera, Doc?The book's third problem arises from the decision to organize it as a series of chapters on individual animation studios arranged alphabetically. There's at least some logic to going in chronological order or thematically, or even by the studios in order of their importance. Alphabetical is arbitrary, rendering the relationship between studios haphazard. An unhappy byproduct of this strategy is that the historically most salient studios come near the end of the alphabet. After chapters on many small,mostly unfamiliar studios, we at last reach the final chapters: Terrytoons, UPA, Walt Disney, Walter Lantz, Warner Bros. Apart from Lantz, these are the main studios relevant to the topic at hand. Amidi prepares the reader with only a brief introduction and no overview, so there is no setup of why UPA is so important or what context Disney provided for the stylistic innovations that are the book's main subject.译文现代卡通,动画风格和设计在20世纪70年代,当我还是一个电影专业的研究生时,美国联合制片公司UPA就受到了学院和影迷们的关注。