51 The Doll’s House

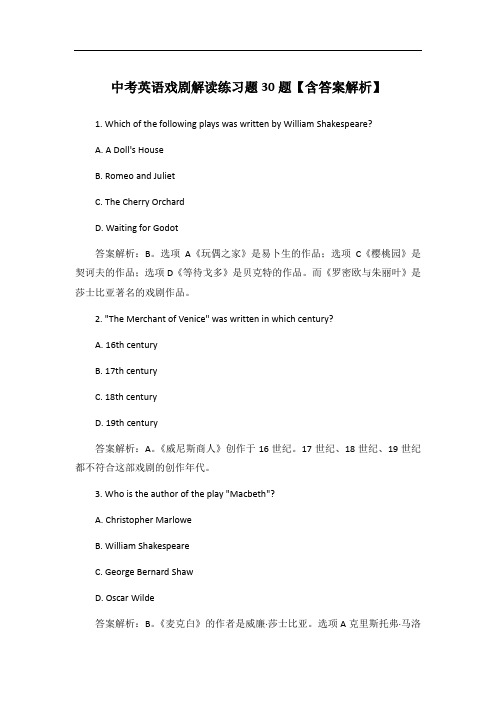

中考英语戏剧解读练习题30题【含答案解析】

中考英语戏剧解读练习题30题【含答案解析】1. Which of the following plays was written by William Shakespeare?A. A Doll's HouseB. Romeo and JulietC. The Cherry OrchardD. Waiting for Godot答案解析:B。

选项A《玩偶之家》是易卜生的作品;选项C《樱桃园》是契诃夫的作品;选项D《等待戈多》是贝克特的作品。

而《罗密欧与朱丽叶》是莎士比亚著名的戏剧作品。

2. "The Merchant of Venice" was written in which century?A. 16th centuryB. 17th centuryC. 18th centuryD. 19th century答案解析:A。

《威尼斯商人》创作于16世纪。

17世纪、18世纪、19世纪都不符合这部戏剧的创作年代。

3. Who is the author of the play "Macbeth"?A. Christopher MarloweB. William ShakespeareC. George Bernard ShawD. Oscar Wilde答案解析:B。

《麦克白》的作者是威廉·莎士比亚。

选项A克里斯托弗·马洛是英国伊丽莎白时期的剧作家,但不是《麦克白》的作者;选项C萧伯纳和选项D王尔德也都不是《麦克白》的作者。

4. Which play was written by Henrik Ibsen?A. HamletB. A Streetcar Named DesireC. Peer GyntD. Death of a Salesman答案解析:C。

选项A《哈姆雷特》是莎士比亚的作品;选项B《欲望号街车》是田纳西·威廉斯的作品;选项D《推销员之死》是阿瑟·米勒的作品。

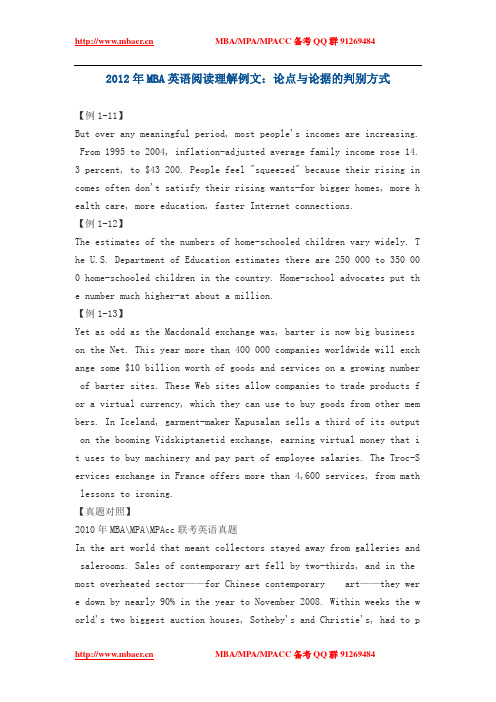

2012年MBA英语阅读理解例文:论点与论据的判别方式

2012年MBA英语阅读理解例文:论点与论据的判别方式【例1-11】But over any meaningful period, most people's incomes are increasing. From 1995 to 2004, inflation-adjusted average family income rose 14.3 percent, to $43 200. People feel "squeezed" because their rising in comes often don't satisfy their rising wants-for bigger homes, more h ealth care, more education, faster Internet connections.【例1-12】The estimates of the numbers of home-schooled children vary widely. T he U.S. Department of Education estimates there are 250 000 to 350 000 home-schooled children in the country. Home-school advocates put the number much higher-at about a million.【例1-13】Yet as odd as the Macdonald exchange was, barter is now big business on the Net. This year more than 400 000 companies worldwide will exch ange some $10 billion worth of goods and services on a growing number of barter sites. These Web sites allow companies to trade products f or a virtual currency, which they can use to buy goods from other mem bers. In Iceland, garment-maker Kapusalan sells a third of its output on the booming Vidskiptanetid exchange, earning virtual money that i t uses to buy machinery and pay part of employee salaries. The Troc-S ervices exchange in France offers more than 4,600 services, from math lessons to ironing.【真题对照】2010年MBA\MPA\MPAcc联考英语真题In the art world that meant collectors stayed away from galleries and salerooms. Sales of contemporary art fell by two-thirds, and in the most overheated sector——for Chinese contemporary art——they were down by nearly 90% in the year to November 2008. Within weeks the wor ld's two biggest auction houses, Sotheby's and Christie's, had to payout nearly $200m in guarantees to clients who had placed works for s ale with them.5.引用专家的评价、专业机构或QUANWEI机构的研究报告等做论据引用也是较为常见的论据形式,我们在小学的时候,老师就开始告诉我们要背诵名人名言用于写作。

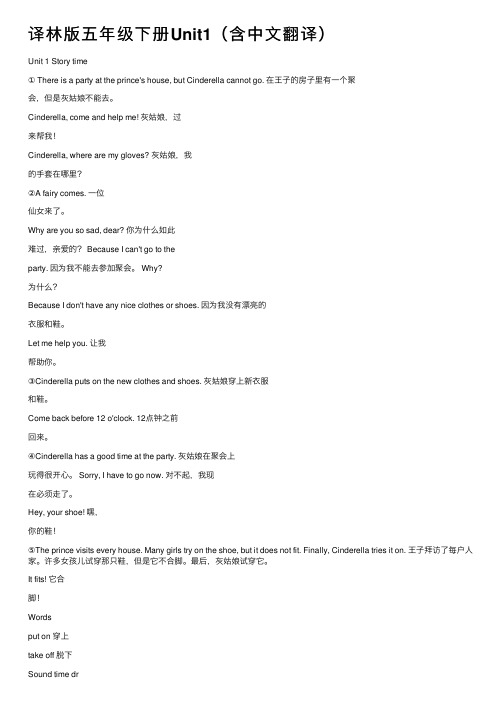

译林版五年级下册Unit1(含中文翻译)

译林版五年级下册Unit1(含中⽂翻译)Unit 1 Story time① There is a party at the prince's house, but Cinderella cannot go. 在王⼦的房⼦⾥有⼀个聚会,但是灰姑娘不能去。

Cinderella, come and help me! 灰姑娘,过来帮我!Cinderella, where are my gloves? 灰姑娘,我的⼿套在哪⾥?②A fairy comes. ⼀位仙⼥来了。

Why are you so sad, dear? 你为什么如此难过,亲爱的? Because I can't go to theparty. 因为我不能去参加聚会。

Why?为什么?Because I don't have any nice clothes or shoes. 因为我没有漂亮的⾐服和鞋。

Let me help you. 让我帮助你。

③Cinderella puts on the new clothes and shoes. 灰姑娘穿上新⾐服和鞋。

Come back before 12 o'clock. 12点钟之前回来。

④Cinderella has a good time at the party. 灰姑娘在聚会上玩得很开⼼。

Sorry, I have to go now. 对不起,我现在必须⾛了。

Hey, your shoe! 嘿,你的鞋!⑤The prince visits every house. Many girls try on the shoe, but it does not fit. Finally, Cinderella tries it on. 王⼦拜访了每户⼈家。

许多⼥孩⼉试穿那只鞋,但是它不合脚。

最后,灰姑娘试穿它。

It fits! 它合脚!Wordsput on 穿上take off 脱下Sound time drdraw 画画dress 连⾐裙drink 喝 driver司机Andrew is having a drink.安德鲁正在喝⽔。

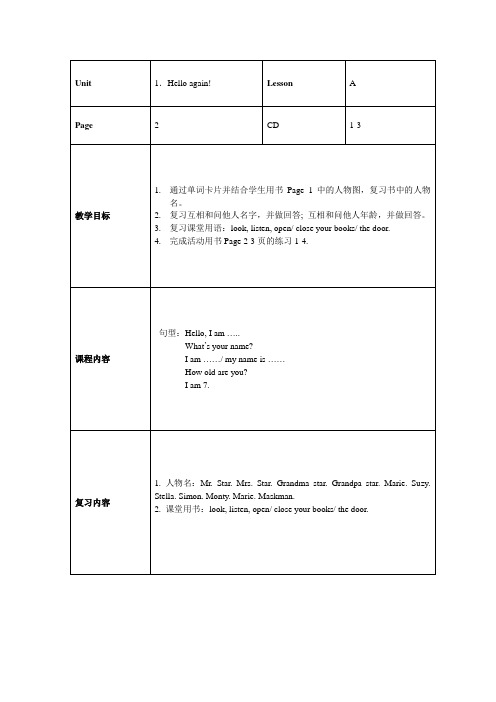

Kid's box 2 中 Unit1-Unit12

13.完成活动用书Page18中的练习8-9。

课程内容

1.句型:I know.

You are a superhero.

It’s ok.

复习内容

1.句型:Whose is……

It is mine/ yours/ hers/ his.

Whose are these….?

2. Back to school

Lesson

B

Page

10

CD

18

教学目标

1.播放CD,通过复习顺口溜《School, school》巩固上节课单词。

2.通过猜个数等游戏,学习句型there is/ are……

3.通过活动用书Page 10中的练习5-6,巩固本课句型。

课程内容

1.句型:There is…….. in the classroom.

课程内容

句型:What is this?This is…..

What is that?That is……it is…..

What are these?These are….

Whatare those? Thoseare….. they are……

复习内容

3.词汇:camera, computer game, kite, lorry, robot, watch.

There are……..intheclassroom.

复习内容

4.词汇:board, bookcase, cupboard, teacher, ruler, desk.

5.句型:Is this a……?

Yes, it is.No,it isn’t.

3.顺口溜:《school, school》

四年级下册期中英语复习综合试卷测试卷(带答案)

一、单项选择1.—My jeans _______ too long. ( )—Try _______, please.A.are; this B.are; these C.is; these2.I have a _______ lesson today. I can _______ well. ( )A.skating; skate B.skating; skating C.skate; skating 3.—Can I have ________ pies? ( )—Yes. Here you are.A.a B.some C.any4.It’s very hot ________ summer in Yangzhou. ( )A.in B.on C.at5.I feel _______. Maybe I have _______. ( )A.cold; a cold B.cold; cold C.a cold; cold 6.—_______ do you do your homework every day? ( )—_______ five o'clock.A.Where; At B.When; At C.When; It’s 7.Winter is very ________. We can ________. ( )A.cool; go skating B.hot; fly kites C.cold; go skating 8.—_______ is the kite? ( )—It's _______ the tree.A.Where; in B.Who; in C.What; on 9.—_______ is it tomorrow? ( )—It's Tuesday.—How many lessons do you have _______ Monday?A.What time; in B.What day; on C.What day; in 10.—I usually go to school at ________. ( )—Oh, it’s not late.A.seven ten B.eight fifty C.two o'clock 11.—Are you ill? ( )—No, _______.A.it isn’t B.I amn’t C.I’m not 12.Ouch! I can't run now. My foot _________. ( )A.big B.small C.hurts13.—I can’t swim. ( )—I can’t swim _______.A.too B.two C.either 14.We don’t have ______ English lesson this afternoon. ( )A.an B.some C.any 15.—It’s eleven thirty. ( )—It’s time to ______.A.have lunch B.have breakfast C.get up 二、用单词的适当形式填空1o you like ________ (mango), Li Lei?17.He can __________ (play) basketball very well.18.It’s time to have a ______ (draw) lesson.19.—Those gloves _____ ( be) too big.—Try these.20.She _____ (like) Music and Science.21.Look at these _______ (boat) on the river! Let’s go _______ (boat). 22.—Whose ______ (毛衣) are these? —They’re Tim’s.2an I have ________ (any) cakes?24.It's 4 o'clock. It's time ________ (go) home.2re these ______ (you), Tom?2o you have ______ (a) art room?27.It's cold outside. Look, it is ________ (snow).28.We are hungry after the football game. We want _____ (have) dinner now. 29.It’s cool and ______ (rain).30.Can you _______ (come) to school tomorrow?三、完成句子31.The first day (第一) of a week is _____.32.-How old is she? -She is ____.3obby can't _______ et _______ p at five thirty.34.—Can you d_________ the hills over there?—Yes, I can.35.______________ (他的衬衫) is too big.36.—______ (谁的毛衣) is this?—It's Helen's.37.I have Science on F______ afternoon.38.I do my _____ at five thirty.39.My grandpa and Kitty usually _______ TV ________ night.40.I play football with Mike on _____ afternoon.四、阅读理解4Lucy and Lily's BedroomThis is Lucy and this is Lily. They are twins. They are twelve. This is their bedroom. It's a nice room. The two beds look the same. This bed is Lily's and that one is Lucy's. The twins have two desks and two chairs. Lucy’s chair is green and Lily’s blue. Lucy’s skirt is on her bed. Lily’s coat is on the clothes line(晒衣绳). Their clock, books and pencil-boxes are on the desk. Their schoolbags are behind the chair. Their bedroom is very nice and tidy(整洁的).41、Lucy and Lily are _________. ( )A.brothersB.sistersC.friendsD.boys42、Lucy and her sister have _________. ( )A.two chairs and one deskB.two desks and one chairC.two chairs and two desksD.one desk and one chair43、Lily's chair is _________ and Lucy's is _________. ( )A.green; blackB.yellow; blackC.blue; greenD.red; yellow44、Where's Lucy's skirt? ( )A.It's on the clothes line.B.It's on their desk.C.It's on her bed.D.It's on her sister's bed.45、Which sentence(句子)is right? ( )A.Their classroom is very nice.B.Their two chairs don't look the same.C.Their clock, coats and pencil-boxes are on the desk.D.Their schoolbags are under the chair.五、阅读理解4This is a big nature park. In the park there is a forest and some mountains. On the mountains there are many trees and some beautiful flowers. There is much grass, too. There is a long pathon the mountain. We can walk there. There are two lakes in the park. One is big, and one is small. We can swim and fish there. What can you see in the lake? Wow, there are many fish swimming in it. What a nice park!46、The nature park is ______. ( )A.small B.not big C.beautiful47、There are some trees, flowers, ______ on the mountains. ( )A.grass and a path B.a lake C.a river48、We can walk on the ______ path. ( )A.short B.long C.clean49、We can see ______ lakes in the park. ( )A.2 B.3 C.450、Are there any fish in the lake? ( )A.Yes. B.No. C.Sorry, I don’t know.六、阅读理解4This is a picture of Lily’s bedroom. It isn’t big, but it is clean and tidy. There is a small b ed in the room. On the bed there are three lovely dolls. And there is a lamp beside the bed. There’s a big window in the wall. A desk is in front of the window. On the desk there is a pencil box and some books. There is a chair in front of the desk. And look at the wall. There are two pictures on the wall. They’re very beautiful. Lily likes her bedroom very much.51、There are _____ on the bed. ( )A.two dolls B.three bears C.three dolls52、A lamp is beside the _____. ( )A.bed B.desk C.window53、The chair is _____ the desk. ( )A.behind B.on C.in front of54、There are two _____ on the wall. ( )A.windows B.pictures C.maps55、This is a picture of _____. ( )A.Lily’s bedroom B.Lily’s classroom C.Lily’s house七、阅读理解4I am Yang Na. I am a student in No. 6 Middle School. My school is big and nice. From Monday to Friday, all the students live in the school. Some of our teachers live with us. They are good to us and they are like (像) our parents.We usually get up at six o'clock in the morning. Then all the students do morning exercises (做早操). At 6:30, all the students and teachers have breakfast. After breakfast, I often read English in the classroom.My favorite day is Thursday, because I have a music lesson on that day. Music is my favorite subject. I usually have three lessons in the morning and three lessons in the afternoon. But onFriday afternoon I only have two lessons.I’m very happy in the school.56、根据时间安排,下列活动排序正确的是 _____。

The-Rocking-Horse-Winner-原文+译文

The Rocking-Horse WinnerThere was a woman who was beautiful, who started with all the advantages, yet she had no luck. She married for love, and the love turned to dust. She had bonny children, yet she felt they had been thrust upon her, and she could not love them. They looked at her coldly, as if they were finding fault with her. And hurriedly she felt she must cover up some fault in herself. Yet what it was that she must cover up she never knew. Nevertheless, when her children were present, she always felt the center of her heart go hard. This troubled her, and in her manner she was all the more gentle and anxious for her children, as if she loved them very much. Only she herself knew that at the center of her heart was a hard little place that could not feel love, no, not for anybody. Everybody else said of her: "She is such a good mother. She adore s her children." Only she herself, and her children themselves, knew it was not so. They read it in each other's eyes.There were a boy and two little girls. They lived in a pleasant house, with a garden, and they had discreet servants, and felt themselves superior to anyone in the neighborhood.Although they lived in style , they felt always an anxiety in the house. There was never enough money. The mother had a small income, and the father had a small income, but not nearly enough for the social position which they had to keep up. The father went in to town to some office. But though he had good prospects, these prospects never materialized. There was always the grinding sense of the shortage of money, though the style was always kept up.At last the mother said: "I will see if I can't make something." But she did not know where to begin. She racked her brains, and tried this thing and the other, but could not find anything successful. The failure made deep lines come into her face. Her children were growing up, they would have to go to school. There must be more money, there must be more money. The father, who was always very handsome and expensive in his tastes, seemed as if he never would be able to do anything worth doing. And the mother, who had a great belief in herself, did not succeed any better, and her tastes were just as expensive.And so the house came to be haunted by the unspoken phrase: There must be more money! There must be more money! The children could hear it all the time, though nobody said it aloud. They heard it at Christmas, when the expensive and splendid toys filled the nursery. Behind the shining modern rocking-horse, behind the smart doll's house, a voice would start whispering: "There must be more money! There must be more money!" And the children would stop playing, to listen for a moment. They would look into each other's eyes, to see if they had all heard. And each one saw in the eyes of the other two that they too had heard. "There must be more money! There must be more money!"It came whispering from the springs of the still-swaying rocking-horse, and even the horse, bending his wooden, champing head, heard it. The big doll, sitting so pink and smirking in her new pram, could hear it quite plainly, and seemed to be smirking all the more self-consciously because of it. The foolish puppy, too, that took the place of the teddy-bear, he was looking so extraordinarily foolish for noother reason but that he heard the secret whisper all over the house: "There must be more money!"Yet nobody ever said it aloud. The whisper was everywhere, and therefore no one spoke it. Just as no one ever says: "We are breathing!" in spite of the fact that breath is coming and going all the time."Mother," said the boy Paul one day, "why don't we keep a car of our own? Why do we always use uncle's, or else a taxi?""Because we're the poor members of the family," said the mother."But why are we, mother?""Well--I suppose," she said slowly and bitterly, "it's because your father has no luck."The boy was silent for some time."Is luck money, mother?" he asked rather timidly."No, Paul. Not quite. It's what causes you to have money.""Oh!" said Paul vaguely. "I thought when Uncle Oscar said filthy lucker, it meant money.""Filthy lucre does mean money," said the mother. "But it's lucre, not luck.""Oh!" said Paul vaguely. "Then what is luck, mother?""It's what causes you to have money. If you're lucky you have money. That's why it's better to be born lucky than rich. If you're rich, you may lose your money. But if you're lucky, you will always get more money.""Oh! Will you? And is father not lucky?""Very unlucky, I should say," she said bitterly.The boy watched her with unsure eyes."Why?" he asked."I don't know. Nobody ever know why one person is lucky and another unlucky." "Don't they? Nobody at all? Does nobody know?""Perhaps God. But He never tells.""He ought to, then. And aren't you lucky either, mother?""I can't be, if I married an unlucky husband.""But by yourself, aren't you?""I used to think I was, before I married. Now I think I am very unlucky indeed." "Why?""Well--never mind! Perhaps I'm not really," she said.The child looked at her, to see if she meant it. But he saw, by the lines of her mouth, that she was only trying to hide something from him."Well, anyhow," he said stoutly, "I'm a lucky person.""Why?" said his mother, with a sudden laugh.He stared at her. He didn't even know why he had said it."God told me," he asserted,brazening it out."I hope He did, dear!" she said, again with a laugh, but rather bitter."He did, mother!""Excellent!" said the mother, using one of her husband's exclamations.The boy saw she did not believe him; or, rather, that she paid no attention to hisassertion. This angered him somewhat, and made him want to compel her attention. He went off by himself, vaguely, in a childish way, seeking for the clue to "luck." Absorbed, taking no heed of other people, he went about with a sort of stealth, seeking inwardly for luck. He wanted luck, he wanted it, he wanted it. When the two girls were playing dolls in the nursery, he would sit on his big rocking-horse, charging madly into space, with a frenzy that made the little girls peer at him uneasily. Wildly the horse career ed the waving dark hair of the boy tossed, his eyes had a strange glare in them. The little girls dared not speak to him.When he had ridden to the end of his made little journey, he climbed down and stood in front of his rocking-horse, staring fixedly into its lowered face. Its red mouth was slightly open, its big eye was wide and glassy-bright."Now!" he would silently command the snorting steed. "Now, take me to where there is luck! Now take me!"And he would slash the horse on the neck with the little whip he had asked Uncle Oscar for. He knew the horse could take him to where there was luck, if only he forced it. So he would mount again, and start on his furious ride, hoping at last to get there. He knew he could get there."You'll break your horse, Paul!" said the nurse."He's always riding like that! I wish he'd leave off !" said his elder sister Joan.But he only glared down on them in silence. Nurse gave him up. She could make nothing of him . Anyhow he was growing beyond her.One day his mother and his Uncle Oscar came in when he was on one of his furious rides. He did not speak to them."Hallo, you young jockey ! Riding a winner?" said his uncle."Aren't you growing too big for a rocking-horse? You're not a very little boy any longer, you know," said his mother.But Paul only gave a blue glare from his big, rather close-set eyes. He would speak to nobody when he was in full tilt . His mother watched him with an anxious expression on her face.At last he suddenly stopped forcing his horse into the mechanical gallop, and slid down."Well, I got there!" he announced fiercely, his blue eyes still flaring, and his sturdy long legs straddling apart."Where did you get to?" asked his mother."Where I wanted to go," he flared back at her."That's right, son!" said Uncle Oscar. "Don't you stop till you get there. What's the horse's name?""He doesn't have a name," said the boy."Gets on without all right?" asked the uncle."Well, he has different names. He was called Sansovino last week." "Sansovino, eh? Won the Ascot . How did you know his name?""He always talks about horse-races with Bassett," said Joan.The uncle was delighted to find that his small nephew was posted with all the racing news. Bassett, the young gardener, who had been wounded in the left foot in thewar and had got his present job through Oscar Cresswell whose batman he had been was a perfect blade of the "turf". He lived in the racing events, and the small boy lived with him.Oscar Cresswell got it all from Bassett."Master Paul comes and asks me, so I can't do more than tell him, sir," said Bassett, his face terribly serious, as if he were speaking of religious matters."And does he ever put anything on a horse he fancies?""Well--I don't want to give him away--he's a young sport, a fine sport, sir. Would you mind asking him himself? He sort of takes a pleasure in it, and perhaps he'd feel I was giving him away, sir, if you don't mind."Bassett was serious as a church.The uncle went back to his nephew and took him off for a ride in the car. "Say, Paul, old man, do you ever put anything on a horse ?" the uncle asked.The boy watched the handsome man closely."Why, do you think I oughtn't to?" he parried."Not a bit of it. I thought perhaps you might give me a tip for the Lincoln."The car sped on into the country, going down to Uncle Oscar's place in Hampshire. "Honor bright?" said the nephew."Honor bright, son!" said the uncle."Well, then, Daffodil.""Daffodil! I doubt it, sonny. What about Mirza?""I only know the winner," said the boy. "That's Daffodil.""Daffodil, eh?"There was a pause. Daffodil was an obscure horse comparatively."Uncle!""Yes, son?""You won't let it go any further, will you? I promised Bassett.""Bassett be damned, old man! What's he got to do with it?""We're partners. We've been partners from the first. Uncle, he lent me my first five shillings, which I lost, I promised him, honor bright , it was only between me and him; only you gave me that ten-shilling note I started winning with, so I thought you were lucky. You won't let it go any further, will you?"The boy gazed at his uncle from those big, hot, blue eyes, set rather close together. The uncle stirred and laughed uneasily."Right you are, son! I'll keep your tip private. Daffodil, eh? How much are you putting on him?""All except twenty pounds," said the boy. "I keep that in reserve."The uncle thought it a good joke."You keep twenty pounds in reserve, do you, you young romancer? What are you betting, then?""I'm betting three hundred," said the boy gravely. "But it's between you and me, Uncle Oscar! Honor bright?"The uncle burst into a roar of laughter."It's between you and me all right, you young Nat Gould," he said, laughing. "Butwhere's your three hundred?""Bassett keeps it for me. We're partners.""You are, are you! And what is Bassett putting on Daffodil?""He won't go quite as high as I do, I expect. Perhaps he'll go a hundred and fifty." "What, pennies?" laughed the uncle."Pounds," said the child, with a surprised look at his uncle. "Bassett keeps a bigger reserve than I do."Between wonder and amusement Uncle Oscar was silent. He pursued the matter no further, but he determined to take his nephew with him to the Lincoln races. "Now, son," he said, "I'm putting twenty on Mirza, and I'll put five for you on any horse you fancy. What's your pick?""Daffodil, uncle.""No, not the fiver on Daffodil!""I should if it was my own fiver," said the child."Good! Good! Right you are! A fiver for me and a fiver for you on Daffodil."The child had never been to a race-meeting before, and his eyes were blue fire. He pursed his mouth tight, and watched. A Frenchman just in front had put his money on Lancelot. Wild with excitement, he flayed his arms up and down, yelling, "Lancelot! Lancelot!" in his French accent.Daffodil came in first, Lancelot second, Mirza third. The child flushed and with eyes blazing, was curiously serene. His uncle brought him four five-pound notes, four to one."What am I to do with these?" he cried, waving them before the boy's eyes."I suppose we'll talk to Bassett," said the boy. "I expect I have fifteen hundred now; and twenty in reserve; and this twenty."His uncle studied him for some moments."Look here, son!" he said. "You're not serious about Bassett and that fifteen hundred, are you?""Yes, I am. But it's between you and me, uncle. Honor bright!""Honor bright all bright, son! But I must talk to Bassett.""If you'd like to be a partner, uncle, with Bassett and me, we could all be partners. Only, you'd have to promise, honor bright , uncle, not to let it go beyond us three. Bassett and I are lucky, and you must be lucky, because it was your ten shillings I started winning with…."Uncle Oscar took both Bassett and Paul into Richmond Park for an afternoon, and there they talked."It's like this, you see, sir," Bassett said. "Master Paul would get me talking about racing events,spinning yearns , you know, sir. And he was always keen on knowing if I'd made or if I'd lost. It's about a year since, now, that I put five shillings on Blush of Dawn for him--and we lost. Then the luck turned, with that ten shillings he had from you, that we put on Singhalese. And since that time, it's been pretty steady, all things considering. What do you say, Master Paul?""We're all right when we're sure," said Paul. "It's when we're not quite sure that we go down."Oh, but we're careful then," said Bassett."But when are you sure?" smiled Uncle Oscar."It's Master Paul, sir," said Bassett, in a secret, religious voice. "It's as if he had it from heaven. Like daffodil, now, for the Lincoln. That was as sure as eggs.""Did you put anything on Daffodil?" asked Oscar Cresswell."Yes, sir. I made my bid.""And my nephew?"Bassett was obstinately silent, looking at Paul."I made twelve hundred, didn't I, Bassett? I told uncle I was putting three hundred on Daffodil.""That's right," said Bassett, nodding."But where's the money?" asked the uncle."I keep it safe locked up, sir. Master Paul he can have it any minute he likes to ask for it.""What, fifteen hundred pounds?""And twenty! And forty, that is, with the twenty he made on the course.""It's amazing!" said the uncle."If Master Paul offers you to be partners, sir, I would if I were you; if you'll excuse me," said Bassett.Oscar cresswell thought about it."I'll see the money," he said.They drove home again, and sure enough, Bassett came round to the garden-house with fifteen hundred pounds in notes. The twenty pounds reserve was left with Joe Glee in the Turf Commission deposit."You see, it's all right, uncle, when I'm sure! Then we go strong, for all we're worth. Don't we, Bassett?""We do that, Master Paul.""And when are you sure?" said the uncle, laughing."Oh, well, sometimes I'm absolutely sure, like about Daffodil," said the boy; "and sometimes I have an idea; and sometimes I haven't even an idea, have I, Bassett? Then we're careful, because we mostly go down.""You do, do you! And when you're sure, like about Daffodil, what makes you sure, sonny?""Oh, well, I don't know," said the boy uneasily. "I'm sure, you know, uncle; that's all.""It's as if he had it from heaven, sir," Bassett reiterated."I should say so!" said the uncle.But he became a partner. And when he Leger was coming on Paul was "sure" about Lively Spark, which was a quite inconsiderable horse. The boy insisted on putting a thousand on the horse, Bassett went for five hundred, and Oscar Cresswell two hundred. Lively Spark came in first, and the betting had been ten to one against him. Paul had made ten thousand."You see," he said, "I was absolutely sure of him."Even Oscar Cresswell had cleared two thousand."Look here, son," he said, "this sort of thing makes me nervous.""It needn't, uncle! Perhaps I shan't be sure again for a long time.""But what are you going to do with your money?" asked the uncle."Of course," said the boy, "I started it for mother. She said she had no luck, because father is unlucky, so I thought if I was lucky, it might stop whispering.""What might stop whispering?""Our house. I hate our house for whispering.""What does it whisper?""Why--why"--the boy fidget ed--"why, I don't know. But it's always short of money, you know, uncle."I know it, son, I know it.""You know people send mother writs, don't you, uncle?""I'm afraid I do," said the uncle."And then the house whispers, like people laughing at you behind your back. It's awful, that is! I thought if I was lucky … ""You might stop it," added the uncle.The boy watched him with big blue eyes, that had an uncanny cold fire in them, and he said never a word."Well, then!" said the uncle. "What are we doing?""I shouldn't like mother to know I was lucky," said the boy."Why not, son?""She'd stop me.""I don't think she would.""Oh!" --and the boy writhed in and odd way--"I don't want her to know, uncle." "All right, son! We'll manage it without her knowing."They managed it very easily. Paul, at the other's suggestion, handed over five thousand pounds to his uncle, who deposited it with the family lawyer, who was then to inform Paul's mother that a relative had put five thousand pounds into his hands, which sum was to be paid out a thousand pounds at a time, on the mother's birthday, for the next five years."So she'll have a birthday present of a thousand pounds for five successive years," said Uncle Oscar. "I hope it won't make it all the harder for her later."Paul's mother had her birthday in November. The house had been "whispering" worse than ever lately, and, even in spite of his luck, Paul could not bear up against it. He was very anxious to see the effect of the birthday letter, telling his mother about the thousand pounds.When there was no visitors, Paul now took his meals with his parents, as he was beyond the nursery control. His mother went into town nearly every day. She had discovered that she had an odd knack of sketching furs and dress materials, so she worked secretly in the studio of a friend who was the chief "artist" for the leading drapers. She drew the figures of ladies in furs and ladies in silk and sequins for the newspaper advertisements. This young woman artist earned several thousand pounds a year, but Paul's mother only made several hundreds, and she was again dissatisfied. She so wanted to be first in something, and she did not succeed, evenin making sketches for drapery advertisements.She was down to breakfast on the morning of her birthday. Paul watched her face as she read her letters. He knew the lawyer's letter. As his mother read it, her face hardened and became more expressionless. Then a cold, determined look came on her mouth. She hid the letter under the pile of others, and said not a word about it. "Didn't you have anything nice in the post for your birthday, mother?" said Paul. "Quite moderately nice," she said, her voice cold and absent.She went away to town without saying more.But in the afternoon Uncle Oscar appeared. He said Paul's mother had had a long interview with the lawyer, asking if the whole five thousand could not be advanced at once, as she was in debt."What do you think, uncle?" said the boy."I leave it to you, son.""Oh, let her have it, then! We can get some more with the other," said the boy. "A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush, laddie!" said Uncle Oscar."But I'm sure to know for the Grand National; or the Lincolnshire; or else the Derby. I'm sure to know for one of them," said Paul.So Uncle Oscar signed the agreement, and Paul's mother touched the whole five thousand. Then something very curious happened. The voices in the house suddenly went mad, like a chorus of frogs on a spring evening. There were certain new furnishings, and Paul had a tutor. He was really going to Eton, his father's school, in the following autumn. There were flowers in the winter, and a blossoming of the luxury Paul's mother had been used to. And yet the voices in the house, behind the sprays of mimosa and almond blossom, and from under the piles of iridescent cushions, simply trilled and screamed in a sort of ecstasy: "There must be more money! Oh-h-h; there must be more money. Oh, now, now-w!Now-w-w--there must be more money!--more than ever! More than ever!"It frightened Paul terribly. He studied away at his Latin and Greek with his tutors. But his intense hours were spent with Bassett. The Grand National had bone by: he had not "known", and had lost a hundred pounds. Summer was at hand. He was in agony for the Lincoln. But even for the Lincoln he didn't "know", and he lost fifty pounds. He became wild-eyed and strange, as if something were going to explode in him."Let it alone, son! Don't you bother about it!" urged Uncle Oscar. But it was as if the boy couldn't really hear what his uncle was saying."I've got to know for the Derby! I've got to know for the Derby!" the child reiterated, his big blue eyes blazing with a sort of madness.His mother noticed how overwrought he was."You'd better go to the seaside. Wouldn't you like to go now to the seaside, instead of waiting? I think you'd better," she said, looking down at him anxiously, her heart curiously heavy about him.But the child lifted his uncanny blue eyes."I couldn't possibly go before the derby, mother!" he said. "I couldn't possibly!" "Why not?" she said, her voice becoming heavy when she was opposed. "Why not?You can still go from the seaside to see the Derby with your Uncle Oscar, if that's what you wish. No need for you to wait here. Besides, I think you care too much about these races. It's a bad sign. My family has been a gambling family, and you won't know till you grow up how much damage it has done. But it has done damage.I shall have to send Bassett away, and ask Uncle Oscar not to talk racing to you, unless you promise to be reasonable about it; go away to the seaside and forget it. You're all nerves!""I'll do what you like, mother, so long as you don't send me away till after the Derby," the boy said."Send you away from where? Just from this house?""Yes," he said, gazing at her."Why, you curious child, what makes you care about this house so much, suddenly?I never knew you loved it."He gazed at her without speaking. He had a secret within a secret, something he had not divulge d, even to Bassett or to his Uncle Oscar.But his mother, after standing undecided and a little bit sullen for some moments, said:"Very well, then! Don't go to the seaside till after the Derby, if you don't wish it. But promise me you won't let your nerves to go pieces. Promise you won't think so much about horse-racing and events, as you call them!""Oh, no," said the boy casually. "I won't think much about them, mother. You needn't worry. I wouldn't worry, mother, if I were you.""If you were me and I were you," said his mother, "I wonder what we should do!" "But you know you needn't worry, mother, don't you?" the boy repeated."I should be awfully glad to know it," she said wearily."Oh, well, you can, you know. I mean, you ought to know you needn't worry," he insisted."Ought I? Then I'll see about it," she said.Paul's secret of secrets was his wooden horse, that which had no name. Since he was emancipated from a nurse and a nursery-governess, he had had hisrocking-horse removed to his own bedroom at the top of the house."Surely, you're too big for a rocking-horse!" his mother had remonstrated. "Well, you see, mother, till I can have a real horse, I like to have some sort of animal about," had been his quaint answer."Do you feel he keeps you company?" she laughed."Oh, yes! He's very good, he always keeps me company, when I'm there," said Paul. So the horse, rather shabby, stood in an arrested prance in the boy's bedroom. The Derby was drawing near, and the boy grew more and more tense. He hardly heard what was spoken to him, he was very frail, and his eyes were really uncanny. His mother had sudden strange seizures of uneasiness about him. Sometimes, for half-an-hour, she would feel a sudden anxiety about him that was almost anguish. She wanted to rush to him at once, and know he was safe.Two nights before the Derby, she was at a big party in town, when one of her rushes of anxiety about her boy, her first-born, gripped her heart till she could hardly speak.She fought with the feeling,might and main , for she believed in common-sense. But it was too strong. She had to leave the dance and go downstairs to telephone to the country. The children's nursery-governess was terribly surprised and startled at being rung up in the night."Are all the children all right, Miss Wilmot?""Oh, yes, they are quite all right.""Master Paul? Is he all right?""He went to bed as right as a trivet . Shall I run up and look at him?" "No," said Paul's mother reluctantly. "No! Don't trouble. It's all right. Don't sit up. We shall be home fairly soon." She did not want her son's privacy intruded upon. "Very good," said the governess.It was about one o'clock when Paul's mother and father drove up to their house. All was still. Paul's mother went to her room and slipped off her white fur cloak. She had told her maid not to wait up for her. she heard her husband downstairs, mixing a whisky-and-soda.And then, because of the strange anxiety at her heart, she stole upstairs to her son's room. Noiselessly she went along the upper corridor. Was there a faint noise? What was it?She stood, with arrested muscles, outside his door, listening. There was a strange, heavy, and yet not loud noise. Her heart stood still. It was a soundless noise, yet rushing and powerful. Something huge, in violent, hushed motion. What was it? What in God's name was it? She ought to know. She felt that she knew the noise. She knew what it was.Yet she could not place it. She couldn't say what it was. And on and on it went, like a madness.Softly, frozen with anxiety and fear, she turned the door-handle.The room was dark. Yet in the space near the window, she heard and saw something plunging to and fro. She gazed in fear and amazement.Then suddenly she switched on the light, and saw her son, in his green pajamas, madly surging on the rocking-horse. The blaze of light suddenly lit him up, as he urged the wooden horse, and lit her up, as she stood, blonde, in her dress of pale green and crystal, in the doorway."Paul!" she cried. "Whatever are you doing?""It's Malabar!" he screamed, in a powerful, strange voice. "It's Malabar!"His eyes blazed at her for one strange and senseless second, as he ceased urging his wooden horse. Then he fell with a crash to the ground, and she, all her tormented motherhood flooding upon her, rushed to gather him up.But he was unconscious, and unconscious he remained, with some brain-fever. He talked and tossed, and his mother sat stonily by his side."Malabar! It's Malabar! Bassett, Bassett, I know! It's Malabar!"So the child cried, trying to get up and urge the rocking-horse that gave him his inspiration."What does he mean by Malabar?" asked the heart-frozen mother."I don't know," said the father stonily.。

The Rocking-Horse Winner 原文译文

The Rocking-Horse WinnerThere was a woman who was beautiful, who started with all the advantages, yet she had no luck. She married for love, and the love turned to dust. She had bonny children, yet she felt they had been thrust upon her, and she could not love them. They looked at her coldly, as if they were finding fault with her. And hurriedly she felt she must cover up some fault in herself. Yet what it was that she must cover up she never knew. Nevertheless, when her children were present, she always felt the center of her heart go hard. This troubled her, and in her manner she was all the more gentle and anxious for her children, as if she loved them very much. Only she herself knew that at the center of her heart was a hard little place that could not feel love, no, not for anybody. Everybody else said of her: "She is such a good mother. She adore s her children." Only she herself, and her children themselves, knew it was not so. They read it in each other's eyes.There were a boy and two little girls. They lived in a pleasant house, with a garden, and they had discreet servants, and felt themselves superior to anyone in the neighborhood.Although they lived in style , they felt always an anxiety in the house. There was never enough money. The mother had a small income, and the father had a small income, but not nearly enough for the social position which they had to keep up. The father went in to town to some office. But though he had good prospects, these prospects never materialized. There was always the grinding sense of the shortage of money, though the style was always kept up.At last the mother said: "I will see if I can't make something." But she did not know where to begin. She racked her brains, and tried this thing and the other, but could not find anything successful. The failure made deep lines come into her face. Her children were growing up, they would have to go to school. There must be more money, there must be more money. The father, who was always very handsome and expensive in his tastes, seemed as if he never would be able to do anything worth doing. And the mother, who had a great belief in herself, did not succeed any better, and her tastes were just as expensive.And so the house came to be haunted by the unspoken phrase: There must be more money! There must be more money! The children could hear it all the time, though nobody said it aloud. They heard it at Christmas, when the expensive and splendid toys filled the nursery. Behind the shining modern rocking-horse, behind the smart doll's house, a voice would start whispering: "There must be more money! There must be more money!" And the children would stop playing, to listen for a moment. They would look into each other's eyes, to see if they had all heard. And each one saw in the eyes of the other two that they too had heard. "There must be more money! There must be more money!"It came whispering from the springs of the still-swaying rocking-horse, and even the horse, bending his wooden, champing head, heard it. The big doll, sitting so pink and smirking in her new pram, could hear it quite plainly, and seemed to be smirking all the more self-consciously because of it. The foolish puppy, too, that took the place of the teddy-bear, he was looking so extraordinarily foolish for noother reason but that he heard the secret whisper all over the house: "There must be more money!"Yet nobody ever said it aloud. The whisper was everywhere, and therefore no one spoke it. Just as no one ever says: "We are breathing!" in spite of the fact that breath is coming and going all the time."Mother," said the boy Paul one day, "why don't we keep a car of our own? Why do we always use uncle's, or else a taxi?""Because we're the poor members of the family," said the mother."But why are we, mother?""Well--I suppose," she said slowly and bitterly, "it's because your father has no luck."The boy was silent for some time."Is luck money, mother?" he asked rather timidly."No, Paul. Not quite. It's what causes you to have money.""Oh!" said Paul vaguely. "I thought when Uncle Oscar said filthy lucker, it meant money.""Filthy lucre does mean money," said the mother. "But it's lucre, not luck.""Oh!" said Paul vaguely. "Then what is luck, mother?""It's what causes you to have money. If you're lucky you have money. That's why it's better to be born lucky than rich. If you're rich, you may lose your money. But if you're lucky, you will always get more money.""Oh! Will you? And is father not lucky?""Very unlucky, I should say," she said bitterly.The boy watched her with unsure eyes."Why?" he asked."I don't know. Nobody ever know why one person is lucky and another unlucky." "Don't they? Nobody at all? Does nobody know?""Perhaps God. But He never tells.""He ought to, then. And aren't you lucky either, mother?""I can't be, if I married an unlucky husband.""But by yourself, aren't you?""I used to think I was, before I married. Now I think I am very unlucky indeed." "Why?""Well--never mind! Perhaps I'm not really," she said.The child looked at her, to see if she meant it. But he saw, by the lines of her mouth, that she was only trying to hide something from him."Well, anyhow," he said stoutly, "I'm a lucky person.""Why?" said his mother, with a sudden laugh.He stared at her. He didn't even know why he had said it."God told me," he asserted,brazening it out."I hope He did, dear!" she said, again with a laugh, but rather bitter."He did, mother!""Excellent!" said the mother, using one of her husband's exclamations.The boy saw she did not believe him; or, rather, that she paid no attention to his assertion. This angered him somewhat, and made him want to compel her attention.He went off by himself, vaguely, in a childish way, seeking for the clue to "luck." Absorbed, taking no heed of other people, he went about with a sort of stealth, seeking inwardly for luck. He wanted luck, he wanted it, he wanted it. When the two girls were playing dolls in the nursery, he would sit on his big rocking-horse, charging madly into space, with a frenzy that made the little girls peer at him uneasily. Wildly the horse career ed the waving dark hair of the boy tossed, his eyes had a strange glare in them. The little girls dared not speak to him.When he had ridden to the end of his made little journey, he climbed down and stood in front of his rocking-horse, staring fixedly into its lowered face. Its red mouth was slightly open, its big eye was wide and glassy-bright."Now!" he would silently command the snorting steed. "Now, take me to where there is luck! Now take me!"And he would slash the horse on the neck with the little whip he had asked Uncle Oscar for. He knew the horse could take him to where there was luck, if only he forced it. So he would mount again, and start on his furious ride, hoping at last to get there. He knew he could get there."You'll break your horse, Paul!" said the nurse."He's always riding like that! I wish he'd leave off !" said his elder sister Joan.But he only glared down on them in silence. Nurse gave him up. She could make nothing of him . Anyhow he was growing beyond her.One day his mother and his Uncle Oscar came in when he was on one of his furious rides. He did not speak to them."Hallo, you young jockey ! Riding a winner?" said his uncle."Aren't you growing too big for a rocking-horse? You're not a very little boy any longer, you know," said his mother.But Paul only gave a blue glare from his big, rather close-set eyes. He would speak to nobody when he was in full tilt . His mother watched him with an anxious expression on her face.At last he suddenly stopped forcing his horse into the mechanical gallop, and slid down."Well, I got there!" he announced fiercely, his blue eyes still flaring, and his sturdy long legs straddling apart."Where did you get to?" asked his mother."Where I wanted to go," he flared back at her."That's right, son!" said Uncle Oscar. "Don't you stop till you get there. What's the horse's name?""He doesn't have a name," said the boy."Gets on without all right?" asked the uncle."Well, he has different names. He was called Sansovino last week." "Sansovino, eh? Won the Ascot . How did you know his name?""He always talks about horse-races with Bassett," said Joan.The uncle was delighted to find that his small nephew was posted with all the racing news. Bassett, the young gardener, who had been wounded in the left foot in the war and had got his present job through Oscar Cresswell whose batman he had been was a perfect blade of the "turf". He lived in the racing events, and the small boy lived with him.Oscar Cresswell got it all from Bassett."Master Paul comes and asks me, so I can't do more than tell him, sir," said Bassett, his face terribly serious, as if he were speaking of religious matters."And does he ever put anything on a horse he fancies?""Well--I don't want to give him away--he's a young sport, a fine sport, sir. Would you mind asking him himself? He sort of takes a pleasure in it, and perhaps he'd feel I was giving him away, sir, if you don't mind."Bassett was serious as a church.The uncle went back to his nephew and took him off for a ride in the car. "Say, Paul, old man, do you ever put anything on a horse ?" the uncle asked.The boy watched the handsome man closely."Why, do you think I oughtn't to?" he parried."Not a bit of it. I thought perhaps you might give me a tip for the Lincoln."The car sped on into the country, going down to Uncle Oscar's place in Hampshire. "Honor bright?" said the nephew."Honor bright, son!" said the uncle."Well, then, Daffodil.""Daffodil! I doubt it, sonny. What about Mirza?""I only know the winner," said the boy. "That's Daffodil.""Daffodil, eh?"There was a pause. Daffodil was an obscure horse comparatively."Uncle!""Yes, son?""You won't let it go any further, will you? I promised Bassett.""Bassett be damned, old man! What's he got to do with it?""We're partners. We've been partners from the first. Uncle, he lent me my first five shillings, which I lost, I promised him, honor bright , it was only between me and him; only you gave me that ten-shilling note I started winning with, so I thought you were lucky. You won't let it go any further, will you?"The boy gazed at his uncle from those big, hot, blue eyes, set rather close together. The uncle stirred and laughed uneasily."Right you are, son! I'll keep your tip private. Daffodil, eh? How much are you putting on him?""All except twenty pounds," said the boy. "I keep that in reserve."The uncle thought it a good joke."You keep twenty pounds in reserve, do you, you young romancer? What are you betting, then?""I'm betting three hundred," said the boy gravely. "But it's between you and me, Uncle Oscar! Honor bright?"The uncle burst into a roar of laughter."It's between you and me all right, you young Nat Gould," he said, laughing. "But where's your three hundred?""Bassett keeps it for me. We're partners.""You are, are you! And what is Bassett putting on Daffodil?""He won't go quite as high as I do, I expect. Perhaps he'll go a hundred and fifty." "What, pennies?" laughed the uncle."Pounds," said the child, with a surprised look at his uncle. "Bassett keeps a bigger reserve than I do."Between wonder and amusement Uncle Oscar was silent. He pursued the matter no further, but he determined to take his nephew with him to the Lincoln races. "Now, son," he said, "I'm putting twenty on Mirza, and I'll put five for you on any horse you fancy. What's your pick?""Daffodil, uncle.""No, not the fiver on Daffodil!""I should if it was my own fiver," said the child."Good! Good! Right you are! A fiver for me and a fiver for you on Daffodil."The child had never been to a race-meeting before, and his eyes were blue fire. He pursed his mouth tight, and watched. A Frenchman just in front had put his money on Lancelot. Wild with excitement, he flayed his arms up and down, yelling, "Lancelot! Lancelot!" in his French accent.Daffodil came in first, Lancelot second, Mirza third. The child flushed and with eyes blazing, was curiously serene. His uncle brought him four five-pound notes, four to one."What am I to do with these?" he cried, waving them before the boy's eyes."I suppose we'll talk to Bassett," said the boy. "I expect I have fifteen hundred now; and twenty in reserve; and this twenty."His uncle studied him for some moments."Look here, son!" he said. "You're not serious about Bassett and that fifteen hundred, are you?""Yes, I am. But it's between you and me, uncle. Honor bright!""Honor bright all bright, son! But I must talk to Bassett.""If you'd like to be a partner, uncle, with Bassett and me, we could all be partners. Only, you'd have to promise, honor bright , uncle, not to let it go beyond us three. Bassett and I are lucky, and you must be lucky, because it was your ten shillings I started winning with…."Uncle Oscar took both Bassett and Paul into Richmond Park for an afternoon, and there they talked."It's like this, you see, sir," Bassett said. "Master Paul would get me talking about racing events,spinning yearns , you know, sir. And he was always keen on knowing if I'd made or if I'd lost. It's about a year since, now, that I put five shillings on Blush of Dawn for him--and we lost. Then the luck turned, with that ten shillings he had from you, that we put on Singhalese. And since that time, it's been pretty steady, all things considering. What do you say, Master Paul?""We're all right when we're sure," said Paul. "It's when we're not quite sure that we go down."Oh, but we're careful then," said Bassett."But when are you sure?" smiled Uncle Oscar."It's Master Paul, sir," said Bassett, in a secret, religious voice. "It's as if he had it from heaven. Like daffodil, now, for the Lincoln. That was as sure as eggs.""Did you put anything on Daffodil?" asked Oscar Cresswell."Yes, sir. I made my bid.""And my nephew?"Bassett was obstinately silent, looking at Paul."I made twelve hundred, didn't I, Bassett? I told uncle I was putting three hundred on Daffodil.""That's right," said Bassett, nodding."But where's the money?" asked the uncle."I keep it safe locked up, sir. Master Paul he can have it any minute he likes to ask for it.""What, fifteen hundred pounds?""And twenty! And forty, that is, with the twenty he made on the course.""It's amazing!" said the uncle."If Master Paul offers you to be partners, sir, I would if I were you; if you'll excuse me," said Bassett.Oscar cresswell thought about it."I'll see the money," he said.They drove home again, and sure enough, Bassett came round to the garden-house with fifteen hundred pounds in notes. The twenty pounds reserve was left with Joe Glee in the Turf Commission deposit."You see, it's all right, uncle, when I'm sure! Then we go strong, for all we're worth. Don't we, Bassett?""We do that, Master Paul.""And when are you sure?" said the uncle, laughing."Oh, well, sometimes I'm absolutely sure, like about Daffodil," said the boy; "and sometimes I have an idea; and sometimes I haven't even an idea, have I, Bassett? Then we're careful, because we mostly go down.""You do, do you! And when you're sure, like about Daffodil, what makes you sure, sonny?""Oh, well, I don't know," said the boy uneasily. "I'm sure, you know, uncle; that's all.""It's as if he had it from heaven, sir," Bassett reiterated."I should say so!" said the uncle.But he became a partner. And when he Leger was coming on Paul was "sure" about Lively Spark, which was a quite inconsiderable horse. The boy insisted on putting a thousand on the horse, Bassett went for five hundred, and Oscar Cresswell two hundred. Lively Spark came in first, and the betting had been ten to one against him. Paul had made ten thousand."You see," he said, "I was absolutely sure of him."Even Oscar Cresswell had cleared two thousand."Look here, son," he said, "this sort of thing makes me nervous.""It needn't, uncle! Perhaps I shan't be sure again for a long time.""But what are you going to do with your money?" asked the uncle."Of course," said the boy, "I started it for mother. She said she had no luck, because father is unlucky, so I thought if I was lucky, it might stop whispering.""What might stop whispering?""Our house. I hate our house for whispering.""What does it whisper?""Why--why"--the boy fidget ed--"why, I don't know. But it's always short of money, you know, uncle."I know it, son, I know it.""You know people send mother writs, don't you, uncle?""I'm afraid I do," said the uncle."And then the house whispers, like people laughing at you behind your back. It's awful, that is! I thought if I was lucky … ""You might stop it," added the uncle.The boy watched him with big blue eyes, that had an uncanny cold fire in them, and he said never a word."Well, then!" said the uncle. "What are we doing?""I shouldn't like mother to know I was lucky," said the boy."Why not, son?""She'd stop me.""I don't think she would.""Oh!" --and the boy writhed in and odd way--"I don't want her to know, uncle." "All right, son! We'll manage it without her knowing."They managed it very easily. Paul, at the other's suggestion, handed over five thousand pounds to his uncle, who deposited it with the family lawyer, who was then to inform Paul's mother that a relative had put five thousand pounds into his hands, which sum was to be paid out a thousand pounds at a time, on the mother's birthday, for the next five years."So she'll have a birthday present of a thousand pounds for five successive years," said Uncle Oscar. "I hope it won't make it all the harder for her later."Paul's mother had her birthday in November. The house had been "whispering" worse than ever lately, and, even in spite of his luck, Paul could not bear up against it. He was very anxious to see the effect of the birthday letter, telling his mother about the thousand pounds.When there was no visitors, Paul now took his meals with his parents, as he was beyond the nursery control. His mother went into town nearly every day. She had discovered that she had an odd knack of sketching furs and dress materials, so she worked secretly in the studio of a friend who was the chief "artist" for the leading drapers. She drew the figures of ladies in furs and ladies in silk and sequins for the newspaper advertisements. This young woman artist earned several thousandpounds a year, but Paul's mother only made several hundreds, and she was again dissatisfied. She so wanted to be first in something, and she did not succeed, even in making sketches for drapery advertisements.She was down to breakfast on the morning of her birthday. Paul watched her face as she read her letters. He knew the lawyer's letter. As his mother read it, her face hardened and became more expressionless. Then a cold, determined look came on her mouth. She hid the letter under the pile of others, and said not a word about it. "Didn't you have anything nice in the post for your birthday, mother?" said Paul. "Quite moderately nice," she said, her voice cold and absent.She went away to town without saying more.But in the afternoon Uncle Oscar appeared. He said Paul's mother had had a long interview with the lawyer, asking if the whole five thousand could not be advanced at once, as she was in debt."What do you think, uncle?" said the boy."I leave it to you, son.""Oh, let her have it, then! We can get some more with the other," said the boy. "A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush, laddie!" said Uncle Oscar."But I'm sure to know for the Grand National; or the Lincolnshire; or else the Derby. I'm sure to know for one of them," said Paul.So Uncle Oscar signed the agreement, and Paul's mother touched the whole five thousand. Then something very curious happened. The voices in the house suddenly went mad, like a chorus of frogs on a spring evening. There were certain new furnishings, and Paul had a tutor. He was really going to Eton, his father's school, in the following autumn. There were flowers in the winter, and a blossoming of the luxury Paul's mother had been used to. And yet the voices in the house, behind the sprays of mimosa and almond blossom, and from under the piles of iridescent cushions, simply trilled and screamed in a sort of ecstasy: "There must be more money! Oh-h-h; there must be more money. Oh, now, now-w!Now-w-w--there must be more money!--more than ever! More than ever!"It frightened Paul terribly. He studied away at his Latin and Greek with his tutors. But his intense hours were spent with Bassett. The Grand National had bone by: he had not "known", and had lost a hundred pounds. Summer was at hand. He was in agony for the Lincoln. But even for the Lincoln he didn't "know", and he lost fifty pounds. He became wild-eyed and strange, as if something were going to explode in him."Let it alone, son! Don't you bother about it!" urged Uncle Oscar. But it was as if the boy couldn't really hear what his uncle was saying."I've got to know for the Derby! I've got to know for the Derby!" the child reiterated, his big blue eyes blazing with a sort of madness.His mother noticed how overwrought he was."You'd better go to the seaside. Wouldn't you like to go now to the seaside, instead of waiting? I think you'd better," she said, looking down at him anxiously, her heart curiously heavy about him.But the child lifted his uncanny blue eyes."I couldn't possibly go before the derby, mother!" he said. "I couldn't possibly!" "Why not?" she said, her voice becoming heavy when she was opposed. "Why not? You can still go from the seaside to see the Derby with your Uncle Oscar, if that's what you wish. No need for you to wait here. Besides, I think you care too much about these races. It's a bad sign. My family has been a gambling family, and you won't know till you grow up how much damage it has done. But it has done damage.I shall have to send Bassett away, and ask Uncle Oscar not to talk racing to you, unless you promise to be reasonable about it; go away to the seaside and forget it. You're all nerves!""I'll do what you like, mother, so long as you don't send me away till after the Derby," the boy said."Send you away from where? Just from this house?""Yes," he said, gazing at her."Why, you curious child, what makes you care about this house so much, suddenly?I never knew you loved it."He gazed at her without speaking. He had a secret within a secret, something he had not divulge d, even to Bassett or to his Uncle Oscar.But his mother, after standing undecided and a little bit sullen for some moments, said:"Very well, then! Don't go to the seaside till after the Derby, if you don't wish it. But promise me you won't let your nerves to go pieces. Promise you won't think so much about horse-racing and events, as you call them!""Oh, no," said the boy casually. "I won't think much about them, mother. You needn't worry. I wouldn't worry, mother, if I were you.""If you were me and I were you," said his mother, "I wonder what we should do!" "But you know you needn't worry, mother, don't you?" the boy repeated."I should be awfully glad to know it," she said wearily."Oh, well, you can, you know. I mean, you ought to know you needn't worry," he insisted."Ought I? Then I'll see about it," she said.Paul's secret of secrets was his wooden horse, that which had no name. Since he was emancipated from a nurse and a nursery-governess, he had had hisrocking-horse removed to his own bedroom at the top of the house."Surely, you're too big for a rocking-horse!" his mother had remonstrated. "Well, you see, mother, till I can have a real horse, I like to have some sort of animal about," had been his quaint answer."Do you feel he keeps you company?" she laughed."Oh, yes! He's very good, he always keeps me company, when I'm there," said Paul. So the horse, rather shabby, stood in an arrested prance in the boy's bedroom. The Derby was drawing near, and the boy grew more and more tense. He hardly heard what was spoken to him, he was very frail, and his eyes were really uncanny. His mother had sudden strange seizures of uneasiness about him. Sometimes, for half-an-hour, she would feel a sudden anxiety about him that was almost anguish. She wanted to rush to him at once, and know he was safe.Two nights before the Derby, she was at a big party in town, when one of her rushes of anxiety about her boy, her first-born, gripped her heart till she could hardly speak. She fought with the feeling,might and main , for she believed in common-sense. But it was too strong. She had to leave the dance and go downstairs to telephone to the country. The children's nursery-governess was terribly surprised and startled at being rung up in the night."Are all the children all right, Miss Wilmot?""Oh, yes, they are quite all right.""Master Paul? Is he all right?""He went to bed as right as a trivet . Shall I run up and look at him?""No," said Paul's mother reluctantly. "No! Don't trouble. It's all right. Don't sit up. We shall be home fairly soon." She did not want her son's privacy intruded upon. "Very good," said the governess.It was about one o'clock when Paul's mother and father drove up to their house. All was still. Paul's mother went to her room and slipped off her white fur cloak. She had told her maid not to wait up for her. she heard her husband downstairs, mixing a whisky-and-soda.And then, because of the strange anxiety at her heart, she stole upstairs to her son's room. Noiselessly she went along the upper corridor. Was there a faint noise? What was it?She stood, with arrested muscles, outside his door, listening. There was a strange, heavy, and yet not loud noise. Her heart stood still. It was a soundless noise, yet rushing and powerful. Something huge, in violent, hushed motion. What was it? What in God's name was it? She ought to know. She felt that she knew the noise. She knew what it was.Yet she could not place it. She couldn't say what it was. And on and on it went, like a madness.Softly, frozen with anxiety and fear, she turned the door-handle.The room was dark. Yet in the space near the window, she heard and saw something plunging to and fro. She gazed in fear and amazement.Then suddenly she switched on the light, and saw her son, in his green pajamas, madly surging on the rocking-horse. The blaze of light suddenly lit him up, as he urged the wooden horse, and lit her up, as she stood, blonde, in her dress of pale green and crystal, in the doorway."Paul!" she cried. "Whatever are you doing?""It's Malabar!" he screamed, in a powerful, strange voice. "It's Malabar!"His eyes blazed at her for one strange and senseless second, as he ceased urging his wooden horse. Then he fell with a crash to the ground, and she, all her tormented motherhood flooding upon her, rushed to gather him up.But he was unconscious, and unconscious he remained, with some brain-fever. He talked and tossed, and his mother sat stonily by his side."Malabar! It's Malabar! Bassett, Bassett, I know! It's Malabar!"So the child cried, trying to get up and urge the rocking-horse that gave him his inspiration.。

高中英语戏剧欣赏练习题50题含答案解析

高中英语戏剧欣赏练习题50题含答案解析1.In the play "Romeo and Juliet", Romeo is known for his _____.A.cowardiceB.ruthlessnessC.passionD.indifference答案解析:C。

在《罗密欧与朱丽叶》中,罗密欧以他的激情著称。

选项A“cowardice”(怯懦)不符合罗密欧的性格特点;选项B“ruthlessness”((无情)也与罗密欧不符;选项D“indifference”((冷漠)同样不符合罗密欧对朱丽叶的热烈感情。

2.The character of Hamlet is often described as _____.A.simple-mindedB.impulsiveC.hesitantD.arrogant答案解析:C。

哈姆雷特这个角色常常被描述为犹豫不决。

选项A“simple-minded”(头脑简单的)不符合哈姆雷特复杂的性格;选项B“impulsive”((冲动的)不太准确;选项D“arrogant”((傲慢的)也不准确。

3.In the drama "Macbeth", Lady Macbeth is characterized by her _____.A.kindnessB.cowardiceC.ambitionziness答案解析:C。

在《麦克白》中,麦克白夫人以她的野心著称。

选项A“kindness”((善良)不符合她的性格;选项B“cowardice”((怯懦)不准确;选项D“laziness”(懒惰)与她的形象不符。

4.The protagonist in "A Doll's House" is known for her _____.A.submissivenessB.rebelliousnessC.crueltyD.selfishness答案解析:B。

娜拉的出走 作文

Nora's DepartureNora's departure from her husband and society is a pivotal moment in Henrik Ibsen's play "A Doll's House." This act of rebellion and self-discovery marks a significant turning point in her life, as she breaks free from the confines of her marriage and societal expectations.Nora's marriage to Torvald Helmer has been a prison of sorts, where she has been treated as a possession rather than an equal partner. Her husband's overbearing nature and suffocating love have restricted her growth andaspirations. In the play, Nora's realization of this truth comes to a head when she discovers that her husband has been lying to her about a loan he took out in her name. This betrayal shatters her illusions about their relationship and prompts her to reevaluate her life choices.Nora's departure is not just a physical act of leaving her husband and home, but also a symbolic rejection of the societal norms that have shaped her life. She rejects the role of the dutiful wife and mother, choosing instead to pursue her own happiness and fulfillment. Her departure is a declaration of independence, a statement that she will no longer allow herself to be defined by others' expectations.The significance of Nora's departure lies in its potential to inspire others to question their own situations and seek change. Her act of rebellion challenges the social norms that limit women's roles and encourages individuals to pursue their own dreams and aspirations. Through Nora's story, we are reminded that the courage to break free from societal constraints is essential for personal growth and fulfillment.娜拉在亨利克·易卜生的戏剧《玩偶之家》中的离家出走,是她生命中一个重要的转折点。

译林版版四年级下学期期末英语质量模拟试卷测试题(含答案)

一、单项选择1.—Let’s draw some pictures here. ( )—_______!A.Good idea B.Well done C.What a pity 2.I ______ a new sweater and Liu Tao _______ a new coat. ( )A.have; have B.has; have C.have; has 3.—How many seasons are there in a year(年)? ( )—________.A.Twelve B.Seven C.Four4.I usually get up _______ seven _______ Sunday morning. ( )A.at; in B.at; on C.in; in 5.—What’s the matter with _______ ? ( )—He is ill.A.he B.his C.him 6.John _______ a football match _______ Sunday afternoon. ( ) A.have; on B.has; in C.has; on 7.—What do you want to drink? ( )—I want some ________.A.hamburgers B.an ice cream C.milk 8.My cousin has a _______ lesson today. She can _______ very well. ( ) A.swimming; swimB.swimming; swimmingC.swim; swimming9.—_______ subjects do you have this term? ( )—Eleven.A.What B.How much C.How many 10._______ is the first season of a year. ( )A.Spring B.Sunday C.Summer 11.—I usually go to school at ________. ( )—Oh, it’s not late.A.seven ten B.eight fifty C.two o'clock 12.—I am ________. ( )—Here’s a glass of water for you.A.thirsty B.hungry C.tired1obby _______ some pies for lunch. ( )A.have B.has C.having 14.We don’t have ______ English lesson this afternoon. ( )A.an B.some C.any 15.It’s t ime ______ breakfast. ( )A.to B.for C.in二、用单词的适当形式填空16._______ (Those) monkey is very lovely.17.Look, my gloves _____ (be) so big.18.Look at the jeans. They're _________ (David).19.Let's _________ (make) a kite.20.—Those gloves _____ ( be) too big.—Try these.21.—How many _____ (dress) can you see?—Five.22.I can see some __________ (flower) over there.23.—Whose _______ (dress) are they?—They’re ______. (Nancy)24.Look at these _______ (boat) on the river! Let’s go _______ (boat). 25.—Whose ______ (毛衣) are these? —They’re Tim’s.26.How many ______ (sheep) do you have?27.The teacher's office is on the ________ (two) floor.28.Tina can't _____ (come) to my birthday party because (因为) she is in Nanjing. 29.The shoes are beautiful. Can I try ________ (they) on?30.It’s cool and ______ (rain).三、完成句子31.—Is Sam at home?—No, he’s _________ (在学校).32.We have an Art lesson every _________ (星期五).33.I ______ TV (看电视) on ______ (星期五) evening.34._______ (看) my gloves. They are _______ (如此) big.35._______ the girl over there? _______ my cousin.36.We have twelve _______ (课程) this term.37.I can see a ______ on the desk.38.I do my _____ at five thirty.39.A: What can you do in spring?B: I can __________ the __________.40.A: What _______ do you ________ on Monday morning?B: I have Art and PE.四、阅读理解4根据短文内容,选择正确答案。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Lession-51 The Doll’s House

Name:周思雨class:11 number:26

Everything about the doll’s house was perfect

It was so big that the courtyard , and there it stayed ,propped up on two wooden boxes beside the feed-room door.

It was summer .and perhaps the smell of paint would have gone off by the time it had to be taken in .

The smell of paint was quite enough to make any one seriously ill.

The perfect thing about the doll’s house was the lamp

Kezia liked more than anything , what she liked frightfully ,was the lamp .

It stood in the middle of the dining-room table,an exquisite little amber lamp with a white globe.

Kelveys were shunned by everybody

Why Mrs. Kevey made them so conspicuous was hard to understand .

The truth was they were dressed in “bits” given to her by the people for whom she worked.

Kezia was the youngest daughter of the Burnell family . Perhaps she was too young to understand why she couldn’t talk to the Keveys .

She invited the Keveys to come into the courtyard to look at the doll’s house because she just wanted to show off the beautiful little house .

She was not aware of the class distinction between her and the Keveys.

Lil wanted to look at the doll’s house

Aunt Beryl didn’t like him .this made her rather depressed and she needed to find an outlet for her heavy heart .

Now that she had frightened the Kelveys and given Kezia a good scolding ,she felt much better.

They must be thinking about the doll house

What a fascinating house it was !

Even though they didn’t have time to have a good look at the house ,they were astounded by it’s beauty which lingered in their mind.

Vocabulary

Sacking n 麻布袋coarse fabric used for bags or sacks eg.Sacking is rough woven material that is used to make sacks

Varnish n 清漆paint that provides a hard glossy transparent coating eg.If you varnish

something, you paint it with varnish

Slab n 厚片block consisting of a thick piece of something eg A slab of something is a thick, flat piece of it.

Streak n 条纹an unbroken series of events eg.Rain had begun to streak the windowpanes.

Congealed adj凝固的congealed into jelly; solidified by cooling eg.His blood was congealed

Slit n 裂缝a long narrow opening eg.And his shirt had a long slit

Plush n 长绒毛a fabric with a nap that is longer and softer than velvet

Eg.their plush new training facility

Amber adj 琥珀色的of a medium to dark brownish yellow color

Eg.when the light hits them they change to ambe

Burn v 烧毁destroy by fire eg.If something is burning, it is on fire.

Traipse v 闲逛walk or tramp about eg.We traipsed all over town looking for a copy of the book

Roll n 名单a list of names eg.The waters of the Huanghe River roll to the sea Shun v 躲避expel from a community or group eg.:From that time forward everybody shunned him.

Spry adj 囚犯moving quickly and lightly eg.the old dog was so spry it was halfway up the stairs before we could stop it.

Trim v 装饰decorate, as with ornaments eg.Something that is trim is neat, and attractive

Quill n 羽毛管pen made from a bird's feather eg.A quill pen on writing paper demands care, attention to grammar, tidiness, controlled thinking

Screw v 拧turn like a screw eg.Screw caps took another 11% of the market

Twitch n 急拉make an uncontrolled, short, jerky motion eg.He twitched me by the sleeve

Flag v 衰退become less intense eg.He draped the flag over the body

Sell n 失望the activity of persuading someone to buy eg.We want to sell you cars Imploring adj 哀求的expressing earnest entreaty

Eg She turned the sad imploring eyes away directly when they lighted upon a stranger Wattle n 篱笆framework consisting of stakes interwoven with branches to form a fence eg Australia's National Floral Emblem is the golden wattle

Shoo v 嘘嘘地赶走drive away by crying `shoo!'

Eg.Stadium guards shoo us away。