Externalities and economic policies in road transport - 2

Economics of the Environment:环境经济学的

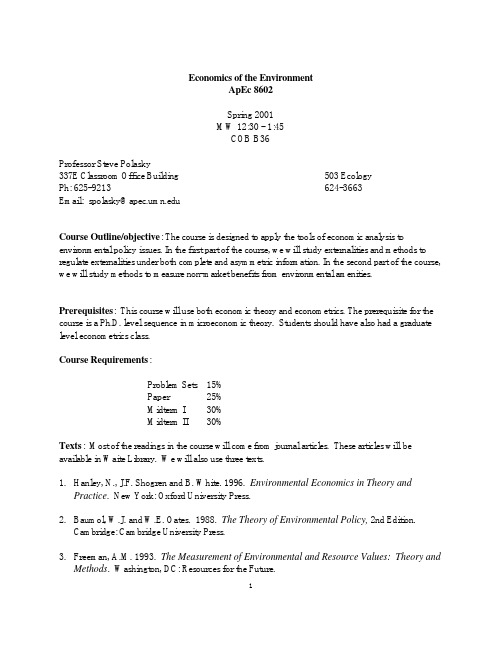

Economics of the EnvironmentApEc 8602Spring 2001MW 12:30 - 1:45COB B36Professor Steve Polasky337E Classroom Office Building 503 EcologyPh: 625-9213 624-3663Email: spolasky@Course Outline/objective: The course is designed to apply the tools of economic analysis to environmental policy issues. In the first part of the course, we will study externalities and methods to regulate externalities under both complete and asymmetric information. In the second part of the course, we will study methods to measure non-market benefits from environmental amenities. Prerequisites: This course will use both economic theory and econometrics. The prerequisite for the course is a Ph.D. level sequence in microeconomic theory. Students should have also had a graduate level econometrics class.Course Requirements:Problem Sets 15%Paper 25%Midterm I 30%Midterm II 30%Texts: Most of the readings in the course will come from journal articles. These articles will be available in Waite Library. We will also use three texts.1. Hanley, N., J.F. Shogren and B. White. 1996. Environmental Economics in Theory andPractice. New York: Oxford University Press.2. Baumol, W.J. and W.E. Oates. 1988. The Theory of Environmental Policy, 2nd Edition.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.3. Freeman, A.M. 1993. The Measurement of Environmental and Resource Values: Theory andMethods. Washington, DC: Resources for the Future.1In addition, there are a number of good books that you might want to consider having if you intend to do environmental economics as a field. Some recommended books are:1. Braden, J. and C. Kolstad (eds.) 1991. Measuring the Demand for EnvironmentalQuality. Amsterdam: North Holland.2. Bromley, D. (ed.) 1995. The Handbook of Environmental Economics. Cambridge, MA:Blackwell Publishers.3. Cornes, R. and T. Sandler. 1986. The Theory of Externalities, Public Goods and Clubs.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.4. Cummings, R., D. Brookshire and W. Schulze. 1986. Valuing Environmental Goods.Totowa, NJ: Rowman and Littlefield.5. Dorfman, R. and N.S. Dorfman (eds.). 1993. Economics of the Environment: SelectedReadings 3rd Edition. New York: Norton.6. Hausman, J.A. (ed.) 1993. Contingent Valuation: A Critical Assessment. Amsterdam:North-Holland Press.7. Johnansson, P.-O. 1987. The Economic Theory and Measurement of EnvironmentalBenefits. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.8. Just, R., D. Hueth, and A. Schmitz. 1982. Applied Welfare Economics and Public Policy.Engelwood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.9. Kopp, R. and V.K. Smith (eds.) 1993. Valuing Natural Assets: The Economics ofNatural Resource Damage Assessments. Washington, DC: Resources for the Future.10. Laffont, J. 1988. Fundamentals of Public Economics. Cambridge: MIT Press.11. Laffont, J.-J. and J. Tirole. 1993. A Theory of Incentives in Procurement and Regulation.Cambridge: MIT Press.12. Maler, K.-G. 1974. Environmental Economics: A Theoretical Inquiry. Baltimore: JohnsHopkins University Press.13. Mitchell, R. and R. Carson. 1989. Using Surveys to Value Public Goods: The ContingentValuation Method. Washington, DC: Resources for the Future.14. Oates, W. 1992. The Economics of the Environment. Brookfield, VT: Edward Elgar.15. Portney, P.R. and R.N. Stavins (eds.) 2000. Public Policies for Environmental Protection,2nd Edition. Washington, DC: Resources for the Future.16. Xepapadeas, A. 1998. Advanced Principles in Environmental Economics. Cheltenham,UK: Edward Elgar.Reading List(* indicates required readings)I. Introduction and Overview1. * Hanley, N., J.F. Shogren and B. White. 1996. Environmental Economics in Theory andPractice. Ch. 1.22. The Economist. Costing the earth: a survey of the environment. Sept. 2, 1989.3. Cropper, M. and W. Oates. 1992. Environmental economics: a survey. Journal of EconomicLiterature 30: 675-740.II. Externalities and Environmental Policy 1: Complete InformationA. Efficiency and the Welfare Theorems1. * Varian, H. 1992. Microeconomic Analysis, 3rd Edition. New York: Norton. Ch. 17-18.2. Dorfman, R. 1993. Some concepts from welfare economics. In Economics of theEnvironment: Selected Readings, R. Dorfman and N.S. Dorfman (eds.). New York: Norton.B. Public Goods, Externalities and Pigouvian Taxes1. * Hanley, N., J.F. Shogren and B. White. 1996. Environmental Economics in Theory andPractice. Ch.2 – 4.2. * Mas-Colell, A., M. Whinston and J. Green. 1995. Microeconomic Theory, Chapter 11.Oxford University Press.3. * Baumol, W. and W. Oates. The Theory of Environmental Policy, Ch. 2-4.4. Cornes, R. and T. Sandler. 1986. The Theory of Externalities, Public Goods, and ClubGoods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Ch. 5-6.5. Bator, F. 1958. The anatomy of market failure. Quarterly Journal of Economics 47: 351-379.6. Samuelson, P.A. 1955. Diagrammatic exposition of the pure theory of public expenditure.Review of Economics and Statistics 37: 350-356.C. Nonconvexities1. * Baumol, W. and W. Oates. The Theory of Environmental Policy, Ch. 7 - 8.2. * Hurwicz, L. 1999. Revisiting externalities. Journal of Public Economic Theory 2: 225-245.3. Starrett, D.A. 1972. Fundamental nonconvexities in the theory of externalities. Journal ofEconomic Theory 4: 180-199.4. Baumol, W.J. and D. F. Bradford. 1972. Detrimental externalities and non-convexities of theproduction set. Economica 39: 160-176.5. * Helfand, G. and J. Rubin. 1994. Spreading versus concentrating damages: environmentalpolicy in the presence of nonconvexities. Journal of Environmental Economics andManagement 27: 84-91.3D. Entry and Exit1. Rose-Ackerman, S. 1973. Effluent charges: a critique. Canadian Journal of Economics 6:512-527.2. *Spulber, D. 1985. Effluent regulation and long-run optimality. Journal of EnvironmentalEconomics and Management 12: 103-116.3. Kohn, R.E. 1994. Do we need the entry-exit condition on polluting firms? Journal ofEnvironmental Economics and Management 27: 92-97.4. McKitrick, R. and R.A. Collinge. 2000. Linear Pigouvian taxes and the optimal size of apolluting industry. Canadian Journal of Economics 33: 1106-1119.E. Averting Behavior1. * Bird, P. 1987. The transferability and depletability of externalities. Journal ofEnvironmental Economics and Management 14: 54-57.2. * Shibuta, H. and Winrich, J. 1983. Control of pollution when the offended defendthemselves. Economica 50: 425-437.3. Smith, V.K. and W.Desvouges. 1986. Averting behavior: does it exist? Economics Letters29: 291-296.F. Property Rights and Bargaining1. * Coase, R. 1960. The problem of social cost. Journal of Law and Economics 3: 1-44.2. Demsetz, A. 1967. Toward a theory of property rights. American Economic Review 57:347-359.3. Libecap, G. 1989. Contracting for Property Rights. Cambridge University Press.G. Liability Rules1. * Segerson, K. 1995. Liability and penalty structures in policy design. In The Handbook ofEnvironmental Economics, D. Bromley (ed.). Oxford: Basil Blackwell.2. Menell, P. 1991. The limitations of legal institutions for addressing environmental risks. Journalof Economic Perspectives 5: 93-113.H. Tradeable Permits1. * Hanley, N., J.F. Shogren and B. White. 1996. Environmental Economics in Theory andPractice. Ch. 5.2. * Baumol, W. and W. Oates. The Theory of Environmental Policy. Ch. 12.3. Dales, J.H. 1968. Land, water, and ownership. Canadian Journal of Economics 1: 791-804.4. * Montgomery, D. 1972. Markets in licenses and efficient pollution control programs. Journalof Economic Theory 5: 395-418.45. * Oates, W., P. Portney and A. McGartland. 1989. The net benefits of incentive-basedregulation: a case study of environmental standard setting. American Economic Review 79:1233-1242.6. * Carlson, C., D. Burtraw, M. Cropper and K. Palmer. 2000. Sulfur dioxide control byelectric utilities: what are the gains from trade? Journal of Political Economy 108: 1292-1326.7. Hahn, R. 1984. Market power and transferable property rights. Quarterly Journal ofEconomics 99: 29-46.8. *C. Kling and J. Rubin. 1997. Bankable permits for the control of environmental pollution.Journal of Public Economics 64: 101-115.9. Rubin, J. 1996. A model of intertemporal emission trading, banking, and borrowing. Journalof Environmental Economics and Management 31: 269-286.10. Ellerman, A.D. et al. 2000. Markets for Clean Air: The U.S. Acid Rain Program. NewYork: Cambridge University Press.I. Political Economy and Environmental Policy1. * Buchanan, J. and G. Tullock. 1975. Polluters’ profits and political response: direct controlversus taxes. American Economic Review 65: 139-147.2. Cropper, M.L. 2000. Has economic research answered the needs of environmental policy?Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 39(3): 328-350.3. Hahn, R. 2000. The impacts of economics on environmental policy. Journal ofEnvironmental Economics and Management 39(3): 375-399.4. * Cropper, M. W. Evans, S. Berardi, M. Ducla-Soares and P. Portney. 1992. TheDeterminants of Pesticide Regulation: A Statistical Analysis of EPA Decision-making. Journal of Political Economy 100: 175-197.5. * Metrick, A. and M. L. Weitzman. 1994. Patterns of behavior in endangered speciespreservation. Land Economics 72(1): 1-16.6. Hamilton, J. 1993. Politics and social costs: estimating the impact of collective action onhazardous waste facilities. Rand Journal of Economics: 101-125.III. Externalities and Environmental Policy 2: Asymmetric InformationA. Optimal Regulation with Asymmetric Information1. * Baumol and Oates. 1988. The Theory of Environmental Policy. Ch 5, 13.2. * Mas-Colell, A., M. Whinston and J. Green. 1995. Microeconomic Theory. Ch. 14.3. Laffont, J.-J. and J. Tirole. 1993. A Theory of Incentives in Procurement and Regulation.Cambridge: MIT Press. Ch. 1.4. * Weitzman, M. 1974. Prices vs. quantities. Review of Economic Studies 41: 477-491.55. * Kwerel, E. 1977. To tell the truth: imperfect information and optimal pollution control.Review of Economic Studies 44: 595-601.6. * Lewis, T. 1996. Protecting the environment when costs and benefits are privately known.Rand Journal of Economics 27: 819-847.7. Roberts, M. and M. Spence. 1976. Effluent charges and licenses under uncertainty. Journalof Public Economics 5: 193-208.8. Spulber, D. 1988. Optimal environmental regulation under asymmetric information. Journalof Public Economics 35: 163-181.9. Farrell, J. 1987. Information and the Coase Theorem. Journal of Economic Perspectives 1:113-129.10. * Shavell, S. 1984. A model of the optimal use of liability and safety regulations. RandJournal of Economics 15: 271-280.11. Xepapadeas, A. Environmental policy under imperfect information: incentives and moralhazard. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 20: 113-126.B. Non-point Source Pollution1. * Segerson, K. 1988. Uncertainty and incentives for non-point pollution control. Journal ofEnvironmental Economics and Management 15: 87-98.2. Holmstrom, B. 1982. Moral hazard in teams. Bell Journal of Economics 13: 324-340.3. Cabe, R. and J. Herriges. 1992. The regulation of non-point source pollution under imperfectand asymmetric information. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 22:134-146.4. Shortle, J.S., R.D. Horan, and D.G. Abler. 1997. Research issues in nonpoint source waterpollution control. American Journal of Agricultural Economics: 571-585.C. Monitoring and Enforcement1. Becker, G. 1968. Crime and punishment: an economic approach. Journal of PoliticalEconomy 76: 169-217.2. * Kaplow, L. and S. Shavell. 1994. Optimal law enforcement with self-reporting of behavior.Journal of Political Economy 102: 583-606.3. * Mookherjee, D. and I.P.L. Png. 1994. Marginal deterrence in enforcement of law. Journalof Political Economy 102: 1039-1066.4. Harrington, W. 1988. Enforcement leverage when penalties are restricted. Journal of PublicEconomics 37: 29-53.5. * Swierzbinski, J.E. 1994. Guilty until proven innocent - regulation with costly and limitedenforcement. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 27: 127-146.6. Malik, A. 1993. Self-reporting and the design of policies for regulating stochastic pollution.Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 24: 241-257.67. * Polasky, S. and H. Doremus. 1998. When the truth hurts: endangered species policy onprivate land with incomplete information. Journal of Environmental Economics andManagement 35: 22-47.D. R&D and Environmental Regulation1. Jaffe, A.B., R.G. Newell and R.N. Stavins. 2001. Technological change and the environment.In The Handbook of Environmental Economics, K-G Maler and J. Vincent (eds.).Amsterdam: North Holland/Elsevier Science.2. * Milliman, S.R. and R. Prince. 1989. Firm incentives to promote technological change inpollution control. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 16: 52-57.3. * Laffont, J.-J. and J. Tirole. 1996. Pollution permits and compliance strategies. Journal ofPublic Economics 62: 85-125.4. * Laffont, J.-J. and J. Tirole. 1996. Pollution permits and environmental innovation. Journalof Public Economics 62: 127-140.5. * Jaffe, A.B. and R.N. Stavins. 1995. Dynamic incentives of environmental regulations: theeffect of alternative policy instruments of technological diffusion. Journal of EnvironmentalEconomics and Management 29: S43-S63.IV. Measuring Benefits and Costs of Environmental ImprovementA. Issues in Non-Market Valuation1. * Hanley, N., J.F. Shogren and B. White. 1996. Environmental Economics in Theory andPractice. Ch. 12.2. Krutilla, J.V. 1967. Conservation reconsidered. American Economic Review 57: 777-786.3. Smith, V.K. 1997. Pricing what is priceless: a status report on pricing non-market valuation ofenvironmental resources. In International Yearbook of Environmental and ResourceEconomics 1997/1998, H. Folmer and T. Tietenberg (eds.). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.4. Bockstael, N.B. and K.E. McConnell. 1993. Public goods as characteristics of nonmarketcommodities. Economic Journal 103: 1244-1257.B. Benefit-Cost Analysis1. * Dorfman, R. 1993. An introduction to benefit-cost analysis. In Economics of theEnvironment: Selected Readings, R. Dorfman and N.S. Dorfman (eds.). New York: Norton.2. * Arrow, K.J. et al. 1996. Is there a role for benefit-cost analysis in environmental, health, andsafety regulation? Science 272: 221-222.3. * Graham, D. 1981. Cost-benefit analysis under uncertainty. American Economic Review71: 715-725.4. Graham, D. 1992. Public expenditure under uncertainty: the net-benefits criteria. AmericanEconomic Review 82: 822-846.7C. Cost of Environmental Regulation1. * Jaffe, A.B., S.R. Peterson, P.R. Portney and R. Stavins. 1995. Environmental regulation andthe competitiveness of U.S. manufacturing. Journal of Economic Literature 33: 132-163.2. * Hazilla, M. and R.J. Kopp. 1990. The social cost of environmental quality regulations: ageneral equilibrium analysis. Journal of Political Economy: 853-873.3. * Porter, M.E. and C. van der Linde. 1995. Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. Journal of Economic Perspectives 9: 97-118.4. * Palmer, K., W.E. Oates and P.R. Portney. 1995. Tightening environmental standards: thebenefit-cost or the no-cost paradigm? Journal of Economic Perspectives 9: 119-132.D. Principles of Welfare Change Measurement1. * Johansson, P.-O. 1987. The Economic Theory and Measurement of EnvironmentalBenefits. New York: Cambridge University Press. Ch. 3-5.2. * Freeman, A.M. 1993. The Measurement of Environmental and Resource Values. Ch. 3-4.3. Willig, R. 1976. Consumer’s surplus without apology. American Economic Review 66: 589-597.4. Hausman, J. 1981. Exact consumer’s surplus and deadweight loss. American EconomicReview 71: 662-676.5. Morey, E. 1984. Confuser surplus. American Economic Review 74: 163-173.6. * Randall, A. and J.R. Stoll. 1980. Consumer's surplus in commodity space. AmericanEconomic Review 70: 449-455.7. * Hanemann, M. 1991. Willingness to pay and willingness to accept: how much can theydiffer? American Economic Review 81: 635-648.V. Revealed Preference MethodsA. Hedonic Models1. * Freeman, A.M. 1993. The Measurement of Environmental and Resource Values:Theory and Methods. Washington, DC: Resources for the Future. Ch.11-12.2. Rosen, H. 1974. Hedonic prices and implicit markets: product differentiation in purecompetition. Journal of Political Economy 82: 34-55.3. * Harrison, D. and D. Rubinfeld. 1978. Hedonic housing prices and the demand for clean air.Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 5: 81-102.4. * Smith, V.K. and J.-C. Huang. 1995. Can markets value air quality? A meta-analysis ofhedonic property value models. Journal of Political Economy 103: 209-227.85. Roback, J. 1982. Wages, rents, and the quality of life. Journal of Political Economy 90:1257-1278.6. * Bartik, T. 1987. The estimation of demand parameters in hedonic price models. Journal ofPolitical Economy 95: 81-88.7. Mahan, B., S. Polasky and R.M. Adams. 2000. Valuing urban wetlands: a property priceapproach. Land Economics 76: 100-113.B. Travel Cost1. * Freeman, A.M. 1993. The Measurement of Environmental and Resource Values:Theory and Methods. Washington, DC: Resources for the Future. Ch.13.2. * Bockstael, N., I. Strand and W. Hanemann. 1987. Time and the recreation demand model.American Journal of Agricultural Economics 69: 293-302.3. * Bockstael, N., M. Hanemann and C. Kling. 1987. Modeling recreational demand in amultiple site framework. Water Resources Research 23: 951-960.4. * Morey, E.R., R.D. Rowe and M. Watson. 1993. A repeated nested logit model of Atlanticsalmon fishing. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 75: 578-593.5. Kling, C.L. and C.J. Thompson. 1996. The implications of model specification for welfareestimation. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 78: 103-114.VI. Stated Preference MethodsA. Contingent Valuation1. * Freeman, A.M. 1993. The Measurement of Environmental and Resource Values:Theory and Methods. Washington, DC: Resources for the Future. Ch. 5-6.2. Arrow, K.J., R. Solow, P. Portney, E. Leamer, R. Radner, and H. Schuman. 1993. Report ofthe NOAA panel on contingent valuation. Federal Register 58: 4601-4614.3. * Portney, P.R. 1994.The contingent valuation debate: why economists should care. Journalof Economic Perspectives 8: 3-18.4. * Hanemann, W.M. 1994. Contingent valuation and economics. Journal of EconomicPerspectives 8: 19-44.5. * Diamond, P. and J. Hausman. 1994. Contingent valuation: is some number better than nonumber? Journal of Economic Perspectives 8: 45-64.6. Kahneman, D. and J.L. Knetsch. 1992. Valuing public goods: the purchase of moralsatisfaction. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 22: 57-70.7. Harrison, G.W. 1992. Valuing public goods with the contingent valuation method: a critique ofKahneman and Knetsch. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 23: 248-257.8. Smith, V.K. 1992. Arbitrary values, good causes, and premature verdicts. Journal ofEnvironmental Economics and Management 22: 71-89.99. * Smith, V.K. and L.L. Osborne. 1996. Do contingent valuation estimates pass a “scope”test? A meta-analysis. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 31: 287-301.B. Comparing or Combining Stated and Revealed Preference Methods1. * Brookshire, D. and D. Coursey. 1987. Measuring the value of a public good: an empiricalcomparison of elicitation methods. American Economic Review 77: 4554-556.2. * Cummings, R.G., S. Elliott, G.W. Harrison and J. Murphy. 1997. Are hypothetical referendaincentive compatible? Journal of Political Economy 105: 609-621.3. Cummings, R.G., G.W. Harrison and E.E. Rutstrom. 1995. Homegrown values andhypothetical surveys: is the dichotomous choice approach incentive-compatible? AmericanEconomic Review 85: 260-266.4. * Cameron, T.A. 1992. Combining contingent valuation and travel cost data for the valuationof nonmarket goods. Land Economics 68: 302-317.5. * Adamowicz, W., J. Louviere and M. Williams. 1994. Combining revealed and statedpreference methods for valuing environmental amenities. Journal of EnvironmentalEconomics and Management 26: 271-292.VII. Special TopicsA. Biodiversity and Endangered Species1. * Weitzman, M. L. 1998. The Noah’s Ark problem. Econometrica 66: 1279-1298.2. * Solow, A. and S. Polasky. 1994. Measuring biological diversity. Environmental andEcological Statistics 1: 95-1073. * Ando, Amy, Jeffrey Camm, Stephen Polasky and Andrew Solow. 1998. Speciesdistributions, land values and efficient conservation. Science 279: 2126-2128.4. * Montgomery, Claire A., Robert A. Pollak, Kathryn Freemark and Denis White. 1999.Pricing biodiversity. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 38: 1-19.5. * Simpson, R. David, Roger A. Sedjo and John Reid. 1996. Valuing biodiversity for use inpharmaceutical research. Journal of Political Economy 104: 163-185.6. Montgomery, Claire A., Gardner M. Brown, Jr. and Darius M. Adams. 1994. The marginalcost of species preservation: the case of the northern spotted owl. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 26: 111-128.7. Berrens, Robert P., David S. Brookshire, Michael McKee and Christian Schmidt. 1998.Implementing the safe minimum standards approach: two case studies from the U.S.Endangered Species Act. Land Economics 74: 147-161.10B. Climate Change1. *Nordhaus, W.D. 1991. To slow or not to slow – the economics of the greenhouse effect.Economic Journal 101: 920-937.2. Nordhaus, W.D. 1994. Managing the Global Commons: The Economics of ClimateChange. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.3. Schelling, T. 1992. Some economics of global warming. American Economic Review 82: 1-14.4. * Chichilnisky, G. and G. Heal. 1994. Who should abate carbon emissions: an internationalviewpoint. Economics Letters 44: 443-449.5. The Energy Journal, May 1999. Special issue on the costs of the Kyoto Protocol.6. * Goulder, L.H. and K. Mathai. 2000. Optimal CO2 abatement in the presence of inducedtechnical change. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 39: 1-38.7. * Chakravorty, U., J. Roumasset and K. Tse. 1997. Endogenous substitution among energyresources and global warming. Journal of Political Economy 105: 1201-1234.C. Trade and Environment1. * Hanley, N., J.F. Shogren and B. White. 1996. Environmental Economics in Theory andPractice. Ch.6.2. * Baumol and Oates. 1988. The Theory of Environmental Policy, Ch. 16.3. * Markusen, J.R. 1975. International externalities and optimal tax structures. Journal ofInternational Economics 5: 15-29.4. * Copeland, B. and M. Taylor. 1995. Trade and transboundary pollution. AmericanEconomic Review 85: 716-737.5. Copeland, B. and M. Taylor. 1994. North-South trade and the environment. QuarterlyJournal of Economics 109: 755-87.6. Chichilnisky, G. 1994. North-South trade and the global environment. American EconomicReview 84: 851-874.7. * Lopez, R. 1994. The environment as a factor of production – the effects of growth and tradeliberalization. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 27: 163-184.D. Growth, Development and Environmental Quality1. * Arrow, K.J. et al. 1995. Economic growth, carrying capacity and the environment. Science269: 520-521.2. * Grossman, G. and A. Kreuger. 1995. Economic growth and the environment. QuarterlyJournal of Economics 110: 352-377.3. * Selden, T. and D. Song. 1994. Environmental quality and development: is there a KuznetsCurve for air pollution emissions? Journal of Environmental Economics and Management27: 147-162.114. * Selden, T. and D. Song. 1995. Neoclassical growth, the J Curve for abatement, and theinverted U curve for Pollution. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 29: 162-169.5. Holtz-Eakin, D. and T. Selden. 1995. Stoking the Fires? CO2 emissions and economicgrowth. Journal of Public Economics 57: 85-101.6. * Stokey, N.L. 1998. Are there limits to growth? International Economic Review 39: 1-31.7. Environment and Development Economics 2(4), 1997. Special issue on the environmentalKuznets Curve.12。

经济博弈论 英文

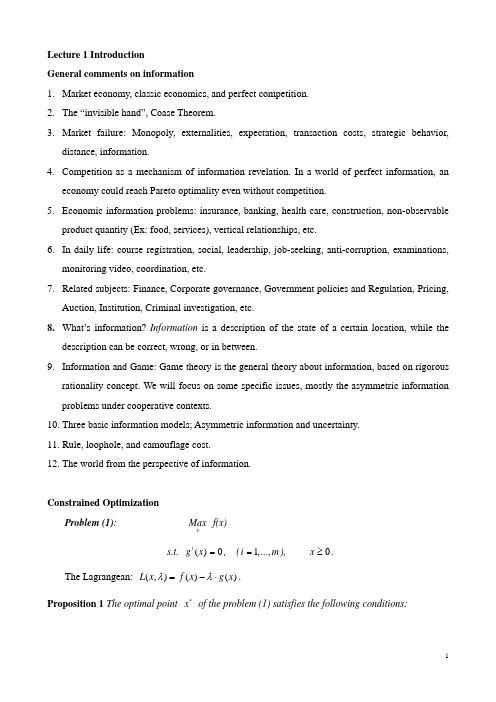

Lecture 1 IntroductionGeneral comments on information1. Market economy, classic economics, and perfect competition.2. The “invisible hand”, Coase Theorem.3. Market failure: Monopoly, externalities, expectation, transaction costs, strategic behavior, distance, information.4. Competition as a mechanism of information revelation. In a world of perfect information, an economy could reach Pareto optimality even without competition.5. Economic information problems: insurance, banking, health care, construction, non-observable product quantity (Ex: food, services), vertical relationships, etc.6. In daily life: course registration, social, leadership, job-seeking, anti-corruption, examinations, monitoring video, coordination, etc.7. Related subjects: Finance, Corporate governance, Government policies and Regulation, Pricing, Auction, Institution, Criminal investigation, etc.8. What’s information? Information is a description of the state of a certain location, while the description can be correct, wrong, or in between.9. Information and Game: Game theory is the general theory about information, based on rigorous rationality concept. We will focus on some specific issues, mostly the asymmetric information problems under cooperative contexts.10. Three basic information models; Asymmetric information and uncertainty.11. Rule, loophole, and camouflage cost.12. The world from the perspective of information.Constrained OptimizationProblem (1): xMax f(x) s.t. ()0i g x =, (1,...,i m =),0x ≥.The Lagrangean: (,)L x λ=()()f x g x λ−⋅. Proposition 1 The optimal point *x of the problem (1) satisfies the following conditions:1) ***1(,)0m i j i j i j L x f g x λλ=∂=−≤∂∑, and ****(,)0j j L x x x λ∂⋅=∂, 1,...,j n =. 2) ***(,)()0i iL x g x λλ∂=−=∂.Problem (2): xMax ()f x s.t. ()0i g x ≤, (1,...,i m =),0x ≥. The Lagrangean: (,)L x λ=()()f x g x λ−⋅, where 0λ≥. Proposition 2 (Kuhn-Tucker Conditions) The optimal point *x of the problem (2) satisfies the following conditions: (1) ***1(,)0m i j i j i j L x f g x λλ=∂=−≤∂∑; ****(,)0j jL x x x λ∂⋅=∂, 1,...,j n =. (2) *()0i g x ≤, and *0λ≥; **()0i i g x λ⋅=.Proposition 3: Maximum problem (2) always possesses a solution if:1). Function ()f x is concave and every ()i g x isconvex; 2). The feasible set {|()0,1,...,;0}i K x g x i n x =≤=≥ is bounded and nonempty.。

Ch32Externalities(微观-范里安-(上海交通大学,赵旭 )

Externalities and Property Rights

Suppose

Agent B is assigned ownership of the air in the room. Agent B can now sell “rights to smoke”. Will there be any smoking? If so, how much smoking and what will be the price for this amount of smoke?

Inefficiency & Negative Externalities

Smoke Money and smoke are both goods for Agent A.

1

0 OA

yA

mA

Inefficiency & Negative Externalities

Smoke Money and smoke are both goods for Agent A.

Externalities and Property Rights

Causing

a producer of an externality to bear the full external cost or to enjoy the full external benefit is called internalizing the externality.

Externalities and Efficiency

Crucially,

an externality impacts a third party; i.e. somebody who is not a participant in the activity that produces the external cost or benefit.

经济学导论习题与答案

一、单选题1、The purpose of making assumptions in economic model building is toA.minimize the amount of work an economist must do.B.simplify the model while keeping important details.C.force the model to yield the correct answer.D.express the relationship mathematically.正确答案:B2、Which of the following is true?A.Efficiency refers to the size of the economic pie; equality refers to how the pie is divided.B.Efficiency and equality can both be achieved if the economic pie is cut into equal pieces.ernment policies usually improve upon both equality and efficiency.D.As long as the economic pie continually gets larger, no one will have to go hungry.正确答案:A3、Rational people make decisions at the margin byA.following marginal traditions.paring marginal costs and marginal benefits.C.following marginal traditions.D.thinking in black-and-white terms.正确答案:B4、The invisible hand works to promote general well-being in the economy primarily throughA.the political process.B.peo ple’s pursuit of self-interest.ernment intervention.D.altruism.正确答案:B5、Causes of market failure includeA.externalities and foreign competition.B.incorrect forecasts of consumer demand and foreign competition.C.market power and incorrect forecasts of consumer demand.D.externalities and market power.正确答案:D6、A circular-flow diagram is a model thatA.helps to explain how the economy works as a whole.B.incorporates all aspects of the real economy.C.helps to explain how participants in the economy interact with one another.D.helps to explain how people make decisions.正确答案:C7、When can two countries gain from trading two goods?A.when the first country can only produce the first good and the second country can only produce the second goodB.when the first country can produce both goods, but can only produce the second good at great cost, and the second country can produce both goods, but can only produce the first good at great costC.when the first country is better at producing both goods and the second country is worse at producing both goodsD.Two countries could gain from trading two goods under all of the above conditions.正确答案:D8、An economy’s production possibilities frontier is also its consumption possibilities frontierA.under all circumstances.B.when the rate of tradeoff between the two goods being produced is constant.C.under no circumstances.D.when the economy is self-sufficient.正确答案:D9、Absolute advantage is found by comparing different producers’A.input requirements per unit of output.B.opportunity costs.C.payments to land, labor, and capital.D.locational and logistical circumstances.正确答案:A10、Suppose Jim and Tom can both produce two goods: baseball bats and hockey sticks. Which of the following is not possible?A.Jim has a comparative advantage in the production of baseball bats and in the production of hockey sticks.B.Jim has an absolute advantage in the production of baseball bats and a comparative advantage in the production of hockey sticks.C.Jim has an absolute advantage in the production of baseball bats and in the production of hockey sticks.D.Jim has an absolute advantage in the production of hockey sticks and a comparative advantage in the production of baseball bats.正确答案:A二、判断题1、Economics is the study of how evenly goods and services are distributed within society.正确答案:×2、If wages for accountants rose, then accountants’ leisure time would have a lower opportunity cost.正确答案:×3、A marginal change is a small incremental adjustment to an existing plan of action.正确答案:√4、Trade with any nation can be mutually beneficial.正确答案:√5、One way that governments can improve market outcomes is to ensure that individuals are able to own and exercise control over their scarce resources.正确答案:√6、Inflation increases the value of money.正确答案:×7、In the circular flow diagram, payments for labor, land, and capital flow from firms to households through the markets for the factors of production.正确答案:√8、Points inside the production possibilities frontier represent inefficient levels of production.正确答案:√9、Interdependence among individuals and interdependence among nations are both based on the gains from trade.正确答案:√10、Trade allows a country to consume outside its production possibilities frontier.正确答案:√。

Lecture #1

Most Americans live in an Urban Area

Other regions of the world are rapidly urbanizing

New CBSAs combine MSAs

Portal to Census Data: American FactFinder ()

Bay Area Counties and Municipalities

Census geography built up from the Census “Block” level

U.S. Census definitions

– Entire U.S. mapped into Census blocks, which are grouped into larger “block groups” and “tracts” – Urban area: population density >1,000/sq. mi. – Urban population: people living in urban areas – Metropolitan area: urban core of at least 50k people, tight commuting connections between urban areas. – Micropolitan area: urban core of 10k to 50k people – Principal city: largest municipality in metro area

Syllabus

• • • • • • • • Why Do Cities Exist? (2 weeks) The Distribution of City Sizes and Place Based Policies (2 weeks) Bid-Rent Curves and Land Use (2 week) Housing (2 weeks) Zoning (1 week) Neighborhood Choice and Segregation (1 week) Local Public Economics (3 weeks) Transportation (2 weeks)

有关经济的英语单词和短语(3篇)

第1篇The field of economics is rich with specialized terminology and phrases that are essential for understanding various aspects of the economy, from basic concepts to complex theories. Below is a comprehensive list of economic terms and phrases, categorized for easy reference.Basic Economic Concepts:1. Economy - A system of production, resource distribution, and consumption within a society.2. Market - A place or situation where buyers and sellers come together to trade goods and services.3. Supply - The quantity of a good or service that is available for sale at a given price.4. Demand - The quantity of a good or service that consumers are willing and able to purchase at a given price.5. Equilibrium - The state in which the quantity supplied equals the quantity demanded.6. Price - The amount of money that must be paid to acquire a good or service.7. Cost - The expenditure of resources required to produce a good or service.8. Value - The importance or usefulness of a good or service.9. Resource - Any input used in the production of goods and services, such as labor, land, and capital.10. Productivity - The efficiency of production, measured by the amount of output per unit of input.Macroeconomic Terms:1. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) - The total value of all goods and services produced within a country over a specific period.2. Inflation - The rate at which the general level of prices for goods and services is rising, and subsequently, purchasing power is falling.3. Deflation - The opposite of inflation, where the general level of prices for goods and services is falling.4. Unemployment - The state of being without a job, seeking for work, and available for work.5. Growth - An increase in the production of goods and services over time.6. Contraction - A decrease in economic activity, often indicated by a decline in GDP.7. Stagflation - A situation where an economy experiences both high inflation and high unemployment simultaneously.8. Recession - A significant decline in economic activity, often marked by a drop in GDP for two consecutive quarters.9. Depression - A severe and prolonged recession.10. Crisis - A situation where the economy faces extreme difficulty, such as a financial crisis or a systemic economic breakdown.Microeconomic Terms:1. Consumer Behavior - The study of how individuals make decisions about what to buy and how much to buy.2. Producer Behavior - The study of how firms make decisions about what to produce and how much to produce.3. Market Structure - The characteristics of a market, such as the number of buyers and sellers, the type of products, and the degree of competition.4. Monopoly - A market structure where there is only one seller of a good or service.5. Oligopoly - A market structure where a few large firms dominate the market.6. Perfect Competition - A market structure where many small firms sell identical products, and no single firm has control over the market price.7. Elasticity - A measure of how much the quantity demanded or supplied changes in response to a change in price.8. Opportunity Cost - The cost of forgoing the next best alternative when making a choice.9. Marginal Cost - The additional cost of producing one more unit of a good or service.10. Marginal Revenue - The additional revenue obtained from selling one more unit of a good or service.Economic Policies and Theories:1. Fiscal Policy - Government policies that use government spending and taxation to influence the economy.2. Monetary Policy - The actions of a central bank to control the money supply and interest rates.3. Keynesian Economics - A theory that suggests government intervention can stabilize the economy during recessions.4. Monetarism - A theory that emphasizes the role of the money supply in determining economic activity.5. Supply-Side Economics - A theory that suggests reducing taxes and regulations can stimulate economic growth.6. Free Market - A market where the prices of goods and services are determined by the forces of supply and demand without government intervention.7. Mixed Economy - An economy that combines elements of both a free market and government intervention.8. Economic Growth - An increase in the production of goods and services over time.9. Economic Development - The process by which a nation improves the economic well-being of its people.10. Sustainable Development - Development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.These terms and phrases provide a foundation for understanding the complexities of the economic world. Whether you are a student of economics, a business professional, or a general enthusiast,familiarizing yourself with this vocabulary will help you navigate the economic landscape with greater ease and insight.第2篇Economics is a complex field that involves the study of how societies allocate resources to satisfy their needs and wants. To navigate this field effectively, it is essential to have a comprehensive understanding of the relevant vocabulary and phrases. Below is a list of economic terms and phrases, categorized for easy reference.Basic Economic Concepts1. Economy - The system of production, resource distribution, and consumption within a society.2. Economic System - The way a society organizes the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services.3. Market - A place where buyers and sellers interact to exchange goods and services.4. Supply - The quantity of a good or service that producers are willing to supply at a given price.5. Demand - The quantity of a good or service that consumers are willing to buy at a given price.6. Equilibrium - The point at which the quantity demanded equals the quantity supplied, leading to a stable price.7. Scarcity - The limited availability of resources relative to the demand for them.8. Opportunity Cost - The value of the next best alternative that is forgone when making a choice.9. Efficiency - The state of producing the maximum output from the least amount of inputs.10. Growth - An increase in the production and consumption of goods and services over time.Economic Indicators1. GDP (Gross Domestic Product) - The total value of all goods and services produced within a country in a given period.2. GNP (Gross National Product) - The total value of all goods and services produced by the residents of a country, regardless of where they are located.3. Inflation - The rate at which the general level of prices for goods and services is rising, and subsequently, purchasing power is falling.4. Deflation - The opposite of inflation, where the general level of prices for goods and services is falling.5. Unemployment - The state of being without a job, actively seeking work, and available to work.6. Consumer Price Index (CPI) - A measure that indicates the average change over time in the prices paid by urban consumers for a market basket of consumer goods and services.7. Producer Price Index (PPI) - A measure of the average change over time in the selling prices received by domestic producers for their output.8. Interest Rates - The percentage at which money is borrowed or lent, usually expressed as an annual percentage rate (APR).9. Exchange Rates - The rate at which one currency can be exchanged for another.Macroeconomic Policies1. Monetary Policy - The actions of a central bank, such as the Federal Reserve in the United States, to control the money supply and influence interest rates.2. Fiscal Policy - The use of government spending and taxation to influence the economy.3. Stabilization Policy - Measures taken to counteract economic fluctuations, such as inflation or recession.4. Austerity Measures - Government policies that aim to reduce government spending and debt, often through cuts in public services and benefits.5. Quantitative Easing - A monetary policy in which a central bank creates new money to purchase government securities or other financial assets.Microeconomic Concepts1. Marginal Cost - The additional cost of producing one more unit of a good or service.2. Marginal Revenue - The additional revenue generated by selling one more unit of a good or service.3. Profit Maximization - The goal of a firm to maximize its profits.4. Cost-Benefit Analysis - An assessment of the benefits and costs of a project or policy.5. Market Failure - A situation where the market does not allocate resources efficiently, often due to externalities, monopolies, or public goods.Business and Industry Terms1. Market Share - The percentage of total sales or units sold by a company within a particular market.2. Brand Loyalty - The degree to which customers are committed to purchasing products from a particular brand.3. Diversification - The practice of spreading investments across various types of assets to reduce risk.4. Mergers and Acquisitions - The process of combining companies or acquiring one company by another.5. Vertical Integration - The process of a company owning or controlling multiple stages of the production process.6. Horizontal Integration - The process of a company merging with or acquiring competitors in the same industry.7. Oligopoly - A market structure with a few large firms dominating the industry.8. Monopolistic Competition - A market structure with many firms selling similar but not identical products.9. Monopoly - A market structure with a single seller and many buyers.10. Perfect Competition - A market structure with many sellers and buyers, where no single entity has control over the market price.Economic Theories1. Classical Economics - The economic theory developed in the 18th and 19th centuries, emphasizing free markets and minimal government intervention.2. Keynesian Economics - An economic theory developed by John Maynard Keynes, advocating for government intervention to stabilize the economy.3. Supply-Side Economics - An economic theory that focuses on reducing taxes and regulations to stimulate economic growth.4. Behavioral Economics - The study of the effects of psychological, social, cognitive, and emotional factors on economic decisions.5. Game Theory - The study of strategic interactions where the outcome for each participant depends on the actions of others.ConclusionUnderstanding economic vocabulary and phrases is crucial for anyone interested in economics, whether as a student, professional, or general consumer. By familiarizing yourself with these terms, you will be better equipped to engage in discussions, analyze economic data, and make informed decisions. Remember that economics is a dynamic field, and new terms and concepts are continually emerging. Stay informed and keep expanding your economic vocabulary.第3篇Economics is a complex field that encompasses a wide range of terms and phrases. Whether you are studying economics, working in the financial sector, or simply interested in understanding the world of economics, it is essential to be familiar with these key terms and phrases. Below is a comprehensive list of economic vocabulary and phrases, categorized for easy reference.1. Basic Economic Terms- Economy - The system of production, resource distribution, and consumption within a society.- Market - A place where goods and services are bought and sold.- Supply - The amount of a good or service that producers are willing to sell at a given price.- Demand - The amount of a good or service that consumers are willing to buy at a given price.- Price - The amount of money that must be paid to purchase a good or service.- Value - The worth of a good or service in terms of its ability to satisfy a want or need.- Gross Domestic Product (GDP) - The total value of all goods and services produced within a country in a specific time period.- Inflation - The rate at which the general level of prices for goods and services is rising, and, subsequently, purchasing power is falling.- Deflation - The opposite of inflation, where the general level of prices for goods and services is falling.- Unemployment - The state of being without a job and actively seeking employment.- Wage - The amount of money paid to an employee for work performed.- Interest - The cost of borrowing money, typically expressed as a percentage of the principal amount.- Capital - Money or other assets used to create wealth or income.- Investment - The allocation of money or resources with the expectation of a profit or return.- Economic growth - An increase in the value of goods and services produced by an economy over time.- Economic recession - A significant decline in economic activity, typically visible in real GDP, real income, employment, etc.2. Macroeconomic Terms- Inflation rate - The rate at which the general level of prices for goods and services is rising.- GDP deflator - A measure of the level of prices of all new, domestically produced, final goods and services in an economy.- Aggregate demand - The total amount of goods and services that households, businesses, the government, and foreign buyers are willing to buy at a given price level.- Aggregate supply - The total amount of goods and services that all firms in an economy are willing to supply at a given price level.- Balance of payments - A record of all economic transactions between residents of one country and the rest of the world over a certain period of time.- Trade deficit - A situation where a country's imports exceed its exports.- Trade surplus - A situation where a country's exports exceed its imports.- Fiscal policy - Government policies that use taxes and spending to influence the economy.- Monetary policy - The actions of a central bank, such as the Federal Reserve in the United States, to control the money supply and influence interest rates.- Stagflation - A situation where there is a combination of highinflation and high unemployment, often accompanied by stagnant economic growth.3. Microeconomic Terms- Marginal cost - The cost of producing one additional unit of a good or service.- Marginal benefit - The additional benefit gained from consuming one more unit of a good or service.- Opportunity cost - The value of the next best alternative that is foregone when making a choice.- Consumer surplus - The difference between the maximum price a consumer is willing to pay for a good and the actual price paid.- Producer surplus - The difference between the minimum price a producer is willing to accept for a good and the actual price received.- Market equilibrium - The state where the quantity supplied equals the quantity demanded at a particular price.- Monopoly - A situation where a single firm dominates the market for a particular good or service.- Oligopoly - A market structure where a few large firms dominate the market for a particular good or service.- Perfect competition - A market structure where there are many buyers and sellers, and no single participant has the power to influence the price.4. Financial Terms- Stock - A share in the ownership of a corporation.- Bond - A debt security issued by a company or government to raise money.- Interest rate - The cost of borrowing money, expressed as a percentage of the principal amount.- Dividend - A portion of a company's earnings distributed to shareholders.- Portfolio - A collection of investments held by an individual or organization.- Mutual fund - A type of investment company that pools money from many investors to purchase securities.- Exchange rate - The value of one currency relative to another currency.- Foreign exchange - The conversion of one currency into another currency.- Capital gains - The profit made on the sale of an asset that has increased in value since its purchase.- Capital losses - The loss incurred on the sale of an asset that has decreased in value since its purchase.5. Economic Theories and Concepts- Supply and demand - The fundamental economic model that explains how prices are determined in a market.- Opportunity cost - The cost of forgoing the next best alternative when making a choice.- Elasticity - A measure of how much the quantity demanded or supplied of a good responds to a change in price.- Marginal analysis - The process of analyzing the additional benefits and costs associated with producing or consuming one more unit of a good or service.- Cost-benefit analysis - The process of comparing the benefits and costs of a project or policy.- Game theory - The study of strategic interactions where the outcomefor each participant depends on the actions of others.- Behavioral economics - The study of the effects of psychological, social, cognitive, and emotional factors on economic decisions.- Keynesian economics - An economic theory that advocates for active government intervention in the economy to stabilize it during recessions.- Supply-side economics - An economic theory that focuses on policies that increase the productive capacity of the economy.Understanding these economic terms and phrases is crucial for anyone interested in the field of economics. Whether you are analyzing market trends, formulating economic policies, or simply trying to make informed decisions about your personal finances, a solid grasp of this vocabulary will serve you well.。

美国经济评论century paper6

American Economic Review 101 (February 2011): 81–108/articles.php?doi =10.1257/aer .101.1.8181As the first decade of the twenty-first century comes to a close, the problem of the commons is more central to economics and more important to our lives than a century ago when Katharine Coman led off the first issue of the American Economic Review with her examination of “Some Unsettled Problems of Irrigation” (Coman 1911). Since that time, 100 years of remarkable economic progress have accompa-nied 100 years of increasingly challenging problems.As the US and other economies have grown, the carrying capacity of the planet—in regard to both natural resources and environmental quality—has become a greater concern. This is particularly true for common-property and open-access resources. While small communities frequently provide modes of oversight and methods for policing their citizens (Elinor Ostrom 2010), as the scale of society has grown, commons problems have spread across communities and even across nations. In some of these cases, no overarching authority can offer complete control, rendering The Problem of the Commons:Still Unsettled after 100 Y earsBy Robert N. Stavins*The problem of the commons is more important to our lives and thus more central to economics than a century ago when Katharine Coman led off the first issue of the American Economic Review . As the US and other economies have grown , the carrying capac-ity of the planet—in regard to natural resources and environmental q uality—has become a greater concern , particularly for common-property and open-access resources. The focus of this article is on some important , unsettled problems of the commons. Within the realm of natural resources , there are special challenges associ-ated with renewable resources , which are frequently characterized by open-access. An important example is the degradation of open-access fisheries. Critical commons problems are also associated with environmental quality. A key contribution of economics has been the development of market-based approaches to environmental protec-tion. These instruments are key to addressing the ultimate commons problem of the twenty-first century—global climate change. (JEL Q15, Q21, Q22, Q25, Q54)* A lbert Pratt Professor of Business and Government, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138; University Fellow, Resources for the Future; and Research Associate, National Bureau of Economic Research. I am grateful to Lori Bennear, Maureen Cropper, Denny Ellerman, Lawrence Goulder, Robert Hahn, Geoffrey Heal, Suzi Kerr, Charles Kolstad, Gilbert Metcalf, William Nordhaus, Wallace Oates, Sheila Olmstead, Robert Pindyck, Andy Reisinger, James Sanchirico, Richard Schmalensee, Kerry Smith, Robert Stowe, Martin Weitzman, and Richard Zeckhauser for very helpful comments on a previous version of this article; and Jane Callahan and Ian Graham of the Wellesley College Archives for having provided inspiration by making available the archives of Katharine Coman (1857–1915), professor of history, then economics, and first chair of Wellesley College’s Department of Economics. Any and all remaining errors are my own.82THE AMERICAN ECONOMIC REVIEW FEBRUARy 2011 commons problems more severe. Although the type of water allocation problems of concern to Coman (1911) have frequently been addressed by common-property regimes of collective management (Ostrom 1990), less easily governed problems of open access are associated with growing concerns about air and water quality, haz-ardous waste, species extinction, maintenance of stratospheric ozone, and—most recently—the stability of the global climate in the face of the steady accumulation of greenhouse gases.Whereas common-property resources are held as private property by some group, open-access resources are nonexcludable. This article focuses exclusively on the latter, and thereby reflects on some important, unsettled problems of the commons.1 It identifies both the contributions made by economic analysis and the challenges facing public policy. Section I begins with natural resources, highlighting the dif-ference between most nonrenewable natural resources, pure private goods that are both excludable and rival in consumption, and renewable natural resources, many of which are nonexcludable (Table 1). Some of these are rival in consumption but characterized by open access. An example is the degradation of ocean fisheries. An economic perspective on these resources helps identify the problems they present for management and provides guidance for sensible solutions.Section II turns to a major set of commons problems that were not addressed until the last three decades of the twentieth century—environmental quality. Although frequently characterized as textbook examples of externalities, these problems can also be viewed as a particular category of commons problems: pure public goods, that are both nonexcludable and nonrival in consumption (Table 1). A key contribu-tion of economics has been the development of market-based approaches to environ-mental protection, including emission taxes and tradable rights. These have potential to address the ultimate commons problem of the twenty-first century, global climate change. Section III concludes.Several themes emerge. First, economic theory—by focusing on market failures linked with incomplete systems of property rights—has made major contributions to our understanding of commons problems and the development of prudent public policies. Second, as our understanding of the commons has become more complex, the design of economic policy instruments has become more sophisticated, enabling policy makers to address problems that are characterized by uncertainty, spatial and temporal heterogeneity, and long duration. Third, government policies that have not accounted for economic responses have been excessively costly, often ineffective, and sometimes counterproductive. Fourth, commons problems have not diminished. While some have been addressed successfully, others have emerged that are more important and more difficult. Fifth, environmental economics is well positioned to offer better understanding and better policies to address these ongoing challenges.1 Ostrom has made key contributions to our understanding of the role of collective action in common-property regimes, as she does in her article in this issue of the Review(Ostrom 2011). With her ably covering that territory, my focus is exclusively on situations of open access. As Daniel W. Bromley (1992) has noted, the better charac-terizations might be common property regimes and open-access regimes, because it is the respective institutional arrangements—as much as the resources themselves—that define the problems. However, I use the conventional characterizations because of their general use in the literature. Although my focus is on the natural resources and environmental realm, similar problems—and related public policies—arise in other areas, such as the allocation of the electromagnetic spectrum for uses in communication (Roberto E. Muñoz and Thomas W. Hazlett 2009).83STAVINS: THE pROBLEM OF THE COMMONS: STILL UNSETTLEd AFTER 100 yEARS VOL. 101 NO. 1I. The Problem of the Commons and the Economics of Natural ResourcesDespite their finite supply in the earth’s crust (and despite decades of doomsday predictions ),2 reserves of mineral and fossil fuel resources have not been exhausted. Price signals reflecting relative (economic ) scarcity have stimulated exploration and discovery, technological progress, and supply substitution. Hence, the world of non-renewable natural resources is characterized more by smooth transitions (Robert M. Solow 1991; William D. Nordhaus 1992) than by overshoot and collapse. Reserves have increased, demand has changed, substitution has occurred, and—in some cases—recycling has been stimulated. As a result, for much of the past century, the economic scarcity of natural resources had not been increasing, but decreasing (Harold J. Barnett and Chandler Morse 1963). Late in the twentieth century, increas-ing scarcity may have set in for a subset of nonrenewable resources, although the time trends are far from clear (V . Kerry Smith 1980; Junsoo Lee, John A. List, and Mark C. Strazicich 2006; John Livernois 2009).The picture is quite different if we turn from nonrenewable natural resources—minerals and fossil fuels—to renewable natural resources (including many forests and most fisheries ), which have exhibited monotonically increasing scarcity . The irony is obvious: many nonrenewable natural resources, which are in finite supply, have not become more scarce over time, and none has been exhausted; but renew-able natural resources, which have the capacity to regenerate themselves, have in many cases become more scarce, and in some cases have indeed been exhausted, that is, become extinct.This irony can be explained by the fact that while most nonrenewable natural resources are characterized by well-defined, enforceable property rights, many renewable resources are held as common property or open access (Table 1). Whereas scarcity is therefore well reflected by markets for nonrenewable natural resources (in the form of “scarcity rent,” the difference between price and marginal extraction cost, originally characterized by Harold Hotelling in 1931 as “net price”),3 such2See, for example, Donella H. Meadows et al. (1972).3 This is not to suggest that the market rate of extraction of nonrenewable natural resources always matches the dynamically efficient rate. Under any one of a number of conditions, markets may lead to inefficient rates of extrac-tion: imperfect information; noncompetitive market structure (the international petroleum cartel ); poorly defined property rights (ground water ); externalities in production or consumption (coal mining and combustion ); or differ-ences in market and social discount rates.Table 1—A Taxonomy of Common Problems in the Natural Resource and Environment RealmExcludableNonexcludable Rival pure private goodsRenewable natural resources Most nonrenewable natural resources characterized by open access (Fossil fuels & minerals )(Ocean fishing )Some privatized renewable resources Some nonrenewable resources (Aquaculture )(Ogallala Aquifer )NonrivalClub goods pure public goods (Water quality of municipal pond )(Clean air, greenhouse gases and climate change )84THE AMERICAN ECONOMIC REVIEW FEBRUARy 2011 rents are dissipated for open-access resources, a reality well illustrated by the bio-economics of open-access fisheries.A. BiologySince the middle of the nineteenth century, open-access fishery stocks of numer-ous species have been depleted beyond sustainable levels, sometimes close to the edge of extinction. The basic biology and economics of fisheries—descendent from the Gordon-Schaefer model (H. Scott Gordon 1954; Anthony Scott 1955; M. B. Schaefer 1957; Colin W. Clark 1990)—makes clear why this has happened.In the upper panel of Figure 1, a logistical growth function plots the time rate of change of the fishery stock (dS/dt) on the vertical axis against the stock’s mass (S) on the horizontal axis:(1) F(S t)=δS t[1 −S t_K],where δ is the intrinsic growth rate of the stock, and K is the carrying capacity of the environment. As the size of the stock increases, its rate of growth increases until scarce food supplies and other consequences of crowding lead to decreasing growth rates. The maximum growth rate is achieved at S MSy , where the “maximum sustain-able yield” (MSy ) occurs. A stable equilibrium is found where the rate of growth transitions from positive to negative, a level of the stock described by biologists as the “carrying capacity” or “natural equilibrium” of the fishery. Another stable equi-librium is found at the origin—exhaustion (extinction).The likelihood of extinction is particularly acute when the natural growth function of a species exhibits “critical depensation,” illustrated in the lower panel of Figure 1:(2) F(S t)=δS t[1 −S t_K][S t_K0− 1],where K0 is the minimum viable population level. Below this critical level of the stock, the natural rate of growth is negative. Hence there are three equilibria: extinc-tion (the origin); the carrying capacity; and the minimum viable population. This reflects the reality that the large habitat ranges that exist for some species, such as whales and some species of birds, means that relatively small numbers are insuf-ficient for mating pairs to yield birth rates that exceed the natural rate of loss to predators and disease.This third equilibrium is unstable. Once the population falls below this critical level, it will proceed inevitably to extinction (unless “artificial” actions are taken, such as confined breeding of the California condor, man-made habitats for the whooping crane, or “zoos in the wild” for giant pandas in China). In the nineteenth century, hunters did not shoot down each and every passenger pigeon, but never-theless, the species was driven to extinction. A similar pattern has doomed other species. A contemporary case in point could be the blue whale (Michael A. Spence 1974), the largest animal known to have existed. Harvesting has been prohibited85STAVINS: THE pROBLEM OF THE COMMONS: STILL UNSETTLEd AFTER 100 yEARS VOL. 101 NO. 1under international agreements since 1965, but it is unclear whether stocks have rebounded, although numbers have been increasing in one region. Across species, there is a mixed picture. Stocks of some whale species are believed to be above and others below their respective minimum viable population (International Whaling Commission 2010).B. BioeconomicsA much greater threat to renewable natural resources than this unusual and unsta-ble biological growth function is the way many of these resources are managed: as common property or open access. To see this, we add some basic economics to theLogistic growthAnnual growthof stock F (S (tons )F (S )(tons )Figure 1. A Simple Model of the Fishery: The Biological Dimension86THE AMERICAN ECONOMIC REVIEWFEBRUARy 2011biology of the fishery(Figure 2). First, a change in the stock of a fishery can be due not only to its biological fundamentals, but to harvests, that is, fishing:(3) dS _ dt= · S t = F (S t ) − q t ,where q t is the harvest rate at time t .4The harvest is a function of the stock and the level of effort, E t , by firms (fishing boats and crews ). Abstracting from dynamics, we can identify the static efficient sustainable yield (that is, we ignore discounting over time, which is all that distin-guishes this from the dynamically efficient sustainable yield ), without loss of key insights. To keep things simple for the graphics, three assumptions are employed: (a ) there is perfectly elastic demand, that is, the price of fish is constant, not a func-tion of the quantity sold; (b ) the marginal cost of a unit of fishing effort is constant; and (c ) the quantity of fish caught per unit of effort is proportional to the size of the stock. With these assumptions, the relationship between effort and harvest is:(4) q t(S t , E t ) = αt S t E t ,where αt is a proportional “catchability coefficient.” And profits, πt , are given by:(5)πt = p t q t (S t , E t ) − c t E t ,4 If equation (3) is replaced by a stochastic differential equation—to characterize uncertainty inherent in the biological growth function—then even lower harvest rates than otherwise can lead to extinction (Robert S. Pindyck 1984).of fishing effort ($)e E MSY E c Fishing effortNet benefit = rent)B (E eC (E e )StockFigure 2. A Simple Model of the Fishery: The Economic Dimension87 VOL. 101 NO. 1STAVINS: THE pROBLEM OF THE COMMONS: STILL UNSETTLEd AFTER 100 yEARSwhere p t is the market price of fish and c is the marginal cost of fishing effort. In the steady state, harvest is equal to growth:(6) F(S t)=q tand so from equations (1) and (2):(7) δS t[1 −S t_K]=αt S t E t .Solving for S and substituting into equation (4) yields steady-state harvest as a func-tion of effort:(8) q SS=αt E t K [1 −αt E t_δ].With this, total revenue at the steady-state (or sustainable) level, equivalent to pq, is indicated in Figure 2 as the total benefits of fishing as a function of effort level. When effort exceeds level E MSy, total fish catch and revenues decline. Total cost is equivalent to the constant marginal cost of effort, c, multiplied by the effort level. Hence, the efficient level of effort, E e, is where net benefits—the difference between total revenue and total cost—are maximized, namely where marginal benefits equal marginal costs. Clearly the maximum sustainable yield is not the efficient harvest level (but would be if fishing were costless).C. The Consequences of Open AccessWhat happens in actual markets with open access, which historically has charac-terized much of commercial fishing around the world (as well as markets for a num-ber of other renewable natural resources)? At the efficient level of effort, E e, each boat would make profits equal to its share of scarcity rent, B(E e) minus C(E e), but with open access these profits become a stimulus for more capital and labor to enter the fishery. Each fisherman considers his marginal revenue and marginal extraction cost, but—without firm property rights—scarcity rent is ignored, and each has an incentive to expend further effort (including more entry) until profits in the fishery are driven to zero: effort level E c in Figure 2, where marginal cost is equal to average revenue rather than equal to marginal revenue. Thus, with open access, it is rational for each fisherman to ignore the asset value of the fishery, because he cannot appro-priate it; all scarcity rent is dissipated (Scott 1955).Because no one holds title to fish stocks in the open ocean, for example, every-one races to catch as much as possible. Each fisherman receives the full benefit of aggressive fishing—a larger catch—but none pays the full cost, an imperiled fishery for everyone. One fisherman’s choices have an effect on other fishermen (of this generation and the next), but in an open access fishery—unlike a privately held c opper mine—these impacts are not taken into account.88THE AMERICAN ECONOMIC REVIEW FEBRUARy 2011 These consequences of open access—predicted by theory—have been validatedrepeatedly with empirical data. A study of the Pacific halibut fishery in the BeringSea estimated that the efficient number of ships was nine, while the actual numberwas 140 (Daniel D. Huppert 1990).5 An examination of the New England lobsterfishery found that in 1966 the efficient number of traps set would have been about450,000, while the actual number was nearly one million. Likewise, an analysis ofthe North Atlantic stock of minke whale found that the efficient stock size was about67,000 adult males, whereas the open-access stock had been depleted to 25,000 (Erik S. Amundsen, Trond Bjørndal, and Jon M. Conrad 1995). In terms of social costs, an analysis of two lobster fisheries in eastern Canada found that losses dueto unrestricted entry amounted to about 25 percent of market value of harvests, duemainly to excess deployment of resources for harvest, with fishery effort exceedingthe efficient level by some 350 percent (J. V. Henderson and M. Tugwell 1979).Under conditions of open access, two externalities may be said to be present. Oneis a contemporaneous externality (as with any public good) in which there is over-commitment of resources: too many boats, too many fishermen, and too much effortas everyone rushes to harvest before others. The other is an intertemporal externalityin which overfishing reduces the stock and hence lowers future profits from fishing.A classic time path of open-access fisheries has been repeated around the world.First, a newly discovered resource is open to all comers; eventually, large harvestsand profits attract more entry to the fishery; boats work harder to maintain theirharvest; despite increased efforts, the harvests decline; and this leads to greaterincreases in effort, resulting in even greater declines in harvest, resulting in essentialcollapse of the fishery. This pattern has been documented for numerous species,including the North Pacific fur seal (Wilen 1976) and the Northern anchovy fishery (Jean-Didier Opsomer and Conrad 1994), as well as Atlantic cod harvested by USand Canadian fishing fleets in the second half of the twentieth century (Figure 3). Although open access drives the stock below its efficient level, it normally does not lead to the stock being exhausted (except possibly under critical depensation, as explained above), because below a certain stock level, the benefits of additional harvest are simply less than the additional costs. This is at the heart of a fundamental error in what is probably the most frequently cited article on common-property and open-access resources, Garrett Hardin’s “The Tragedy of the Commons” (1968): Picture a pasture open to all … A rational herdsman concludes that the only sensible course for him to pursue is to add another animal to his herd. And another; and another … Each man is locked into a system that compels him to increase his herd without limit—in a world that is limited. Ruin is the destination toward which all men rush, each pursuing his own best interest in a society that believes in the freedom of thec ommons. Freedom in the commons brings ruin to all (Hardin 1968, 1244).As Partha Dasgupta (1982)subsequently wrote: “It would be difficult to locate another passage of comparable length and fame containing as many errors as the one above.” Ruin is not the outcome of the commons, but rather excessive e mployment5 These fisheries are actually “regulated open-access fisheries,” because they are subject to restrictions (James N. Sanchirico and James E. Wilen 2007), as explained below.89STAVINS: THE pROBLEM OF THE COMMONS: STILL UNSETTLEd AFTER 100 yEARS VOL. 101 NO. 1of capital and labor, small profits for participants, and an excessively depletedresource stock.6 Those are bad enough.D. Alternative policies for the Commons problemThe most obvious solution to a commons problem—in principle—may be to enclose it, that is, put in place fee-simple or other well-defined property rights to limit access.7 In the case of a natural fishery, this is typically not feasible, but it is if species are immobile (oysters, clams, mussels ), can be confined by barriers (shrimp, carp, catfish ), or instinctively return to their place of birth to spawn (salmon, ocean trout ). Such fish farming (aquaculture ) is feasible and profitable with a limited but important set of commercial species (Table 1). Presently, approximately one-third of global fisheries production is supplied by commercial aquaculture, much of it in Asia (United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization 2007).Because aquaculture remains confined to a limited set of commercial species (and environmental concerns may preclude expansion ), there has been a history of g overnment attempts to regulate open-access fisheries through other means. The most frequent regulatory approach has been to limit annual catches (with the target typically being the maximum sustainable yield, not the efficient level of effort ) through restrictions on allowed technologies, closure of particular areas, or6The annual loss due to rent dissipation in global fisheries has been estimated to be on the order of $90 billion (Sanchirico and Wilen 2007).7 Recall that my focus is on open access, not common property. Arrangements of various kinds can and do serve to limit access to common-property resources (Ostrom 2010). An example in the fisheries realm would be the informal groups of lobster harvesters (“gangs”) in coastal Maine that seek to restrict access to identified areas (James M. Acheson 2003).0100,000200,000300,000400,000500,000600,0001950196019701980199020002010Landings (tons)YearFigure 3. Annual Harvest of Atlantic Cod, 1950–2008Source: United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization 2010.90THE AMERICAN ECONOMIC REVIEW FEBRUARy 2011 i mposition of limited seasons. These regulatory approaches have the effect of rais-ing the marginal cost of fishing effort, in effect pivoting up the total cost function in Figure 2 until it intersects the benefit function at point X, thereby achieving the fish-ing effort associated with maximum sustainable yield, E MSy , or potentially to point y, thereby achieving the efficient effort level, E e.Marginal costs increase because each new constraint causes fishermen to r eoptimize. In response to constraints on technology, areas, or season, fishermen employ excessively expensive methods (overcapitalization) to catch a given quan-tity of fish. Technology constraints can lead to the employment of more labor; area closures can lead to the adoption of more sophisticated technologies; and reduced seasons result in the use of more boats. Although the harvest may be curtailed as desired, the net benefits to the fishery are essentially zero. Costs go up for fishermen (as resources are squandered). Social efficiency is not achieved, nor is it approached.A dramatic example is provided by New York City’s once thriving oyster fishery. In 1860, 12 million oysters were sold in New York City markets. By 1880, produc-tion was up to 700 million oysters per year. “New Yorkers rich and poor were slurp-ing the creatures in oyster cellars, saloons, stands, houses, cafes, and restaurants...” (Elizabeth Royte 2006). It became clear that the oyster beds were being depleted. First the city restricted who could harvest oysters, then when they were permitted to do so. Eventually, the city limited the use of dredges and steam power. Nevertheless, in 1927, the last of the city’s oyster beds closed (a casualty not only of open access to the oyster habitats, but also of the use of the city’s harbors as another sort of com-mons, namely as a depository for the city’s sewage).The economic implications of conventionally regulated open-access fisher-ies are typically worse than those that occur under unregulated open-access con-ditions (Frances R. Homans and Wilen 1997; Martin D. Smith and Wilen 2003). Overcapitalization is greater, as is the consequent welfare loss. Such situations with conventional open-access fisheries regulation are commonplace: overfishing occurs, the fishery stock is depleted, the government responds by regulating the catch, thereby driving up the cost of fishing, fishermen complain that they cannot make a profit, and harvests continue to fall. Is there a better way?From an economic perspective, the most obvious way of assuring that harvest lev-els are maintained at an efficient level while providing incentives for cost reductions is a tax on fish harvests. Such an efficient tax, which increases marginal costs, rotates the total costs line in Figure 2 until it intersects total benefits at point y, and thereby brings about E e, similar to conventional regulation. The tax that would accomplish this would be equal to the difference between B(E e) and C(E e). Despite the apparent graphical similarity with the conventional regulatory outcome, this approach is effi-cient, because rather than destroying the rents through higher resource costs, the tax transfers the rents from the private to the public sector. Hence, the social net benefits of the tax approach are identical to those under the efficient outcome.There is a problem, however. For the fishermen, these transfers are very real costs. The rent that would be received by a sole owner is received by the government instead. Any fishermen who might want the fishery to be managed efficiently will surely object to this particular approach. So, is there some way that the catch can be restricted to the efficient level, with real resource costs minimized, but without transferring the rents from fishermen to the government?。

CHAP05_Externalities Problems and Solutions 公共金融与公共政策课件

Each year, federal, state, and local governments spend $33.2 billion repairing our roadways. Damage to roadways comes from many sources, but a major culprit is the passenger vehicle, and the damage it does to the roads is proportional to vehicle weight.

© 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber

3

Chapter 5 Externalities: Problems and Solutions

© 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber

13

Chapter 5 Externalities: Problems and Solutions

5.1

Externality Theory

Positive Externalities

positive consumption externality When an individual’s consumption increases the well-being of others but the individual is not compensated by those others.

© 2007 Worth Publishers Public Finance and Public Policy, 2/e, Jonathan Gruber

HND 经济学(2) outcome3