EU eastern enlargement and foreign investment Implications from a neoclassical growth model

欧盟发展历程英文

欧盟发展历程英文The Development of the European UnionThe European Union (EU) has undergone significant development since its establishment in the aftermath of World War II. This supranational organization, initially founded as the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) in 1951, aimed to ensure peace and stability in Europe by integrating key sectors of the economies of its member states.In 1957, the Treaties of Rome established the European Economic Community (EEC) and the European Atomic Energy Community (EAEC). The EEC sought to establish a common market among its member states, promoting the free movement of goods, services, capital, and people. Over time, the EU expanded its scope to encompass various policy areas, including agriculture, transportation, and regional development.In 1993, the Maastricht Treaty marked a significant milestone in the development of the EU. It transformed the EEC into the European Union and laid the foundation for the euro, the single currency shared by most EU member states. The treaty also established the pillars of the EU's political integration, encompassing foreign and security policies, as well as cooperation in judicial and home affairs.The EU continued to expand in the 2000s, with several waves of enlargement bringing in new member states from Central and Eastern Europe. This expansion strengthened the EU's role as a promoter of democracy, stability, and economic growth in the region.The EU has also faced various challenges throughout its development. Economic crises, such as the eurozone debt crisis in 2008, tested the resilience of the common currency and required collective efforts to stabilize the European economy. The EU has also grappled with issues of democratic legitimacy and decision-making, as well as managing the tensions between member states with differing national interests.In recent years, the EU has been focused on addressing global challenges, including climate change, migration, and cybersecurity. It has played a vital role in negotiating international agreements, such as the Paris Agreement on climate change, and in shaping global norms and standards.Overall, the development of the EU has been characterized by a gradual deepening of integration and cooperation among its member states. It has evolved from an organization primarily focused on economic cooperation to one with a broader mandate, encompassing political, legal, and social integration. Despite the challenges it faces, the EU continues to play a crucial role in maintaining peace, promoting prosperity, and protecting the values of its member states.。

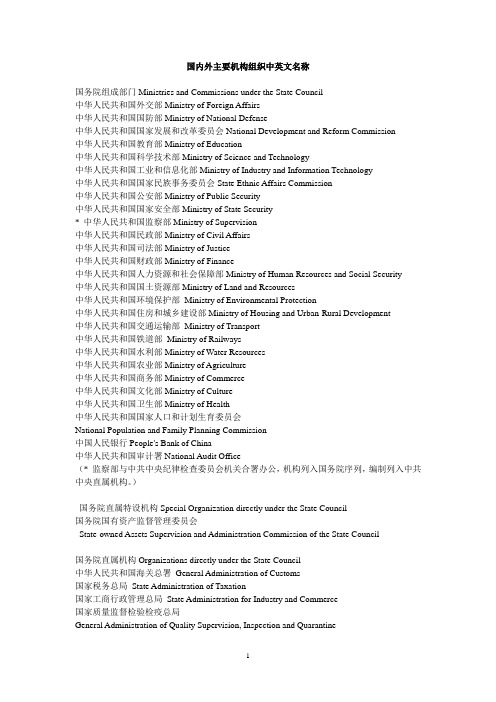

国内外主要机构中英文对照

国内外主要机构组织中英文名称国务院组成部门Ministries and Commissions under the State Council中华人民共和国外交部Ministry of Foreign Affairs中华人民共和国国防部Ministry of National Defense中华人民共和国国家发展和改革委员会National Development and Reform Commission中华人民共和国教育部Ministry of Education中华人民共和国科学技术部Ministry of Science and Technology中华人民共和国工业和信息化部Ministry of Industry and Information Technology中华人民共和国国家民族事务委员会State Ethnic Affairs Commission中华人民共和国公安部Ministry of Public Security中华人民共和国国家安全部Ministry of State Security* 中华人民共和国监察部Ministry of Supervision中华人民共和国民政部Ministry of Civil Affairs中华人民共和国司法部Ministry of Justice中华人民共和国财政部Ministry of Finance中华人民共和国人力资源和社会保障部Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security中华人民共和国国土资源部Ministry of Land and Resources中华人民共和国环境保护部Ministry of Environmental Protection中华人民共和国住房和城乡建设部Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development中华人民共和国交通运输部Ministry of Transport中华人民共和国铁道部Ministry of Railways中华人民共和国水利部Ministry of Water Resources中华人民共和国农业部Ministry of Agriculture中华人民共和国商务部Ministry of Commerce中华人民共和国文化部Ministry of Culture中华人民共和国卫生部Ministry of Health中华人民共和国国家人口和计划生育委员会National Population and Family Planning Commission中国人民银行People's Bank of China中华人民共和国审计署National Audit Office(* 监察部与中共中央纪律检查委员会机关合署办公,机构列入国务院序列,编制列入中共中央直属机构。

外籍人士支付指南英文版

外籍人士支付指南英文版Expatriate Guide to Payment in the United States.As an expatriate living in the United States, managing your finances can be a daunting task. The country's complex financial system and unfamiliar banking practices can make it challenging to navigate the waters of money management. This guide aims to provide you with a comprehensive understanding of the payment system in the US, empowering you to make informed decisions and manage your finances effectively.Currency and Exchange Rates.The official currency of the United States is the US Dollar ($). It is divided into 100 cents. When making international transactions, it is essential to be aware of the exchange rate between your home currency and the US Dollar. Exchange rates fluctuate constantly, so it's advisable to monitor them regularly to get the bestpossible deal.Banking in the US.Opening a bank account in the US is crucial for managing your finances. To open an account, you will typically need to provide proof of identity, such as a passport or driver's license, and proof of address. Once your account is established, you will receive a debit card and checks for making payments.Electronic Funds Transfer (EFT)。

International Organizations

European Union:Brussels, Belgium阶段:荷卢比三国经济联盟欧洲共同体European Community发展而来1991.12马斯特里赫特条约1993生效27成员国人口5亿欧洲委员会(执行机构)The European Commission欧洲议会(5年一次)(监督、咨询机构)The European Parliament例行全体会议:法国斯特拉斯堡特别:布鲁塞尔理事会:决策机构,包括欧洲联盟理事会The Council of the European Union和欧洲理事会Council of Europe(立法权)欧洲法院The Court of Justice 欧洲中央银行The European Central Bank十二星旗:圣母玛利亚的十二星冠永远保佑欧洲联盟(起初的12成员国)欧洲日:5月9日欧元:1999年1月1日启用,2002年1月1日正式流通欧洲煤钢共同体、欧洲经济共同体和欧洲原子能共同体欧共体创始国为法国、联邦德国、意大利、荷兰、比利时和卢森堡六国①实现关税同盟和共同外贸政策②实行共同的农业政策③建立政治合作制度④基本建成内部统一大市场⑤建立政治联盟成立:1945年10月24日在美国旧金山《联合国宪章》,193会员国语言:英语,法语,中文,西班牙语,俄语,阿拉伯语联合国大会总部:美国纽约联合国大会、联合国安全理事会、联合国经济及社会理事会、联合国托管理事会、国际法院和联合国秘书处(秘书长5年)联合国大会:审议机构,全体组成,9月第三个星期二,重要:三分之二,一般:一半安全理事会:中国、法国、俄罗斯、英国、美国等5个常任理事国和10个非常任(2年),大国一致原则国际组织:为成员国展开各种层次的对话与合作提供场所,管理全球化所带来的国际社会公共问题,在成员国之间分配经济发展的成果和收益,组织国际社会各领域的活动,调停和解决国际政治和经济争端,继续维持国际和平,国际关系民主化的渠道和推进器亚太经合组织:1989年,free trade & investigation运作机制:领导人非正式会议部长级会议高官会委员会和工作组秘书处目标是为本区域人民普便福祉持续推动区域成长与发展;促进经济互补性,鼓励货物、服务、资本、技术的流通;发展并加快开放及多边的贸易体系;减少贸易与投资壁垒。

商务英语缩略语

GAB 借款安排总协定 General agreement to Borrow

ISI 进口替代工业化 Import-substitution industrialization

IDA 国际开发协会 International development association

RCC 储备货币国家 Reserve-currency country

SDRS 特别提款权 Special Drawing Rights

UNCTAD 联合国贸易和发展会议 United Nations Conferences on Trnde and Development

VERs 自动出口限制 Voluntary export vestraints

BBS 英国广播公司

BBA 工商管理学士 bachelor of bu siness adminis tration

MBA Master of bu siness adminis tration

SBO 战略事业单位 strategi Nhomakorabea marketing planning

TAM 总可行市场 total available narket

KPMG 毕马威

GE General electvic company

ABB

BNP 巴黎百富勤

市场营销:

CE并行工程 Concurrent engineering

DSS 决策支持系统 decision support system

DRP分销资源计划 distribution ressurce plonning

欧洲债券和外国债券的区别

一、欧洲债券和外国债券的区别外国债券是市场所在地的非居民在一国债券市场上以该国货币为面值发行的国际债券。

欧洲债券与传统的外国债券不同,是市场所在地非居民在面值货币国度以外的若干个市场同时发行的国际债券。

二者都是国际债券。

外国债券和欧洲债券还有发下主要区别:(1)、外国债券普通由市场所在地国度的金融机构为主承销商组成承销辛迪加承销,而欧洲债券则由来自多个国度金融机构组成的国际性承销辛迪加承销。

(2)、外国债券受市场所在地国度证券主管机构的监管,公募发行管理比拟严厉,需求向证券主管机构注册注销,发行后可申请在证券买卖所上市;私募发行无须注册注销,但不能上市挂牌买卖。

欧洲债券以行时不用向债券面值货币国或发行市场所在地的证券主管机构注销,不受任何一国的管制,通常采用公募发行方式,发行扣可申请在某一证券买卖所上市。

(3)、外国债券的发行和买卖必需受当地市场有关金融法律法规的管制和约束;而欧洲债券不受面值货币国或发行市场所在地的法律的限制,因而债券发行协议中心须注明一旦发作纠葛应根据的法律规范。

(4)、外国债券的妊人和投资者必需依据市场所在地的法规交征税金;而欧洲债券采取不记名债券方式,投资者的利息收入是免税的。

(5)、外国债券付息方式普通与当地国内债券相同,如扬基债券普通每半年付息一次;而欧洲债券通常都是每年付息一次。

二、哪些公司可以发行债券发行公司债券的主体,也就是具有发行公司债券资格的公司为:股份有限公司;国有独资公司;两个以上的国有企业设立的有限责任公司;两个以上的国有投资主体投资设立的有限责任公司。

在这四种可以发行公司债券的主体中,股份有限公司可以发行公司债券是通行的规则,而有限责任公司作为发行主体,则是要求规模较大,有可靠的信誉,支持其正常的发展。

三、法律依据:《公司法》第一百六十一条可转换公司债券的发行上市公司经股东大会决议可以发行可转换为股票的公司债券,并在公司债券募集办法中规定具体的转换办法。

欧盟:带领欧洲进步【英文】

Combined population of EU Member States

499

million

7.4

Percent of world‟s population Percent of global Gbined worldwide Official Development Assistance

– Managing policy and cooperation programs (IT related)

– Personal staff European Commissioner Liikanen (telecoms) – Headed e-government, now head of IT for inclusion

• EU‟s executive branch proposes legislation, manages Union‟s day-to-day business and budget, and enforces rules.

• Negotiates trade agreements and manages Europe‟s multilateral development cooperation.

• Since the creation of the EU half a century ago, Europe has enjoyed the longest period of peace in its history. • European political integration is unprecedented in history. • EU enlargement has helped overcome the division of Europe – contributing to peace, prosperity, and stability across the continent. • A single market and a common currency conditions for companies and consumers. • EU has united the citizens of Europe – while preserving Europe‟s diversity.

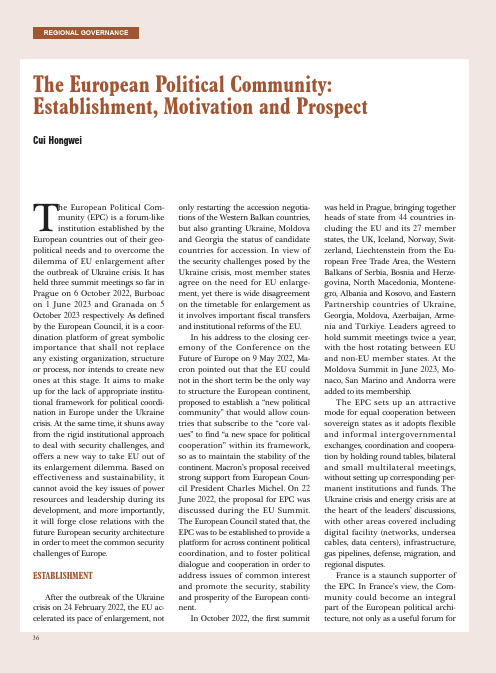

The_European_Political_Community

The European Political Community: Establishment, Motivation and ProspectCui HongweiT he European Political Com-munity (EPC) is a forum-likeinstitution established by the European countries out of their geo-political needs and to overcome the dilemma of EU enlargement after the outbreak of Ukraine crisis. It has held three summit meetings so far in Prague on 6 October 2022, Burboac on 1 June 2023 and Granada on 5 October 2023 respectively. A s defined by the European Council, it is a coor-dination platform of great symbolic importance that shall not replace any existing organization, structure or process, nor intends to create new ones at this stage. It aims to make up for the lack of appropriate institu-tional framework for political coordi-nation in Europe under the Ukraine crisis. At the same time, it shuns away from the rigid institutional approach to deal with security challenges, and offers a new way to take EU out of its enlargement dilemma. Based on effectiveness and sustainability, it cannot avoid the key issues of power resources and leadership during its development, and more importantly, it will forge close relations with the future European security architecture in order to meet the common security challenges of Europe.ESTABLISHMENTAfter the outbreak of the Ukraine crisis on 24 February 2022, the EU ac-celerated its pace of enlargement, not only restarting the accession negotia-tions of the Western Balkan countries,but also granting Ukraine, Moldovaand Georgia the status of candidatecountries for accession. In view ofthe security challenges posed by theUkraine crisis, most member statesagree on the need for EU enlarge-ment, yet there is wide disagreementon the timetable for enlargement asit involves important fiscal transfersand institutional reforms of the EU.In his address to the closing cer-emony of the Conference on theFuture of Europe on 9 May 2022, Ma-cron pointed out that the EU couldnot in the short term be the only wayto structure the European continent,proposed to establish a “new politicalcommunity” that would allow coun-tries that subscribe to the “core val-ues” to find “a new space for politicalcooperation” within its framework,so as to maintain the stability of thecontinent. Macron’s proposal receivedstrong support from European Coun-cil President Charles Michel. On 22June 2022, the proposal for EPC wasdiscussed during the EU Summit.The European Council stated that, theEPC was to be established to provide aplatform for across continent politicalcoordination, and to foster politicaldialogue and cooperation in order toaddress issues of common interestand promote the security, stabilityand prosperity of the European conti-nent.In October 2022, the first summitwas held in Prague, bringing togetherheads of state from 44 countries in-cluding the EU and its 27 memberstates, the UK, Iceland, Norway, Swit-zerland, Liechtenstein from the Eu-ropean Free Trade A rea, the WesternBalkans of Serbia, Bosnia and Herze-govina, North Macedonia, Montene-gro, Albania and Kosovo, and EasternPartnership countries of Ukraine,Georgia, Moldova, Azerbaijan, A rme-nia and Türkiye. Leaders agreed tohold summit meetings twice a year,with the host rotating between EUand non-EU member states. At theMoldova Summit in June 2023, Mo-naco, San Marino and Andorra wereadded to its membership.The EPC sets up an attractivemode for equal cooperation betweensovereign states as it adopts flexibleand informal intergovernmentalexchanges, coordination and coopera-tion by holding round tables, bilateraland small multilateral meetings,without setting up corresponding per-manent institutions and funds. TheUkraine crisis and energy crisis are atthe heart of the leaders’ discussions,with other areas covered includingdigital facility (networks, underseacables, data centers), infrastructure,gas pipelines, defense, migration, andregional disputes.France is a staunch supporter ofthe EPC. In France’s view, the Com-munity could become an integralpart of the European political archi-tecture, not only as a useful forum for36September/October 2023 CONTEMPORARY WORLDdialogue, but also as a source of coop-eration projects among its members. Close to the French position, Italy is keen to exploit the potential of the Community to promote concrete co-operation projects. Germany, Poland and the European Commission have expressed measured support for co-operation projects. Most EU member states do not want EU institutions to spend too much EU fund due to their participation in the Community, and EU candidate countries fear that the Community could become an alter-native to EU enlargement.Non-EU countries of Moldova, Türkiye and the UK have taken a pos-itive stance towards the EPC. Moldova offered to host the second summit. Türkiye is looking to the Community as a new way to develop relations with European countries while bypassing EU institutions. For the UK, as the Eu-ro-Atlantic region remains a priority in its international strategy and prac-tical cooperation with the EU stays high on its foreign policy agenda, it will host the fourth Summit in the first half of 2024.While still in its infancy, the EPC member states have already reached some bilateral and small multilateral agreements through the platform. To name a few, the UK and the NorthSeas Energy Cooperation whoseorganization membership includeseight EU member states and Norwayhave signed a MOU to deal with en-ergy supply issues. The French andBritish leaders pledged to boost bilat-eral cooperation in energy, illegal im-migration and defense. In the area ofmediating regional disputes, Michel,Macron and Scholz met with the lead-ers of Azerbaijan and A rmenia in aneffort to forge consensus on Nagorno-Karabakh peace agreement. Theleaders of Türkiye and A rmenia heldmeetings to normalize bilateral rela-tions. The issue of Kosovo was alsohigh on its agenda.MOTIVATIONSFirst, the EPC offers a new ap-proach to solve the tough issues of EUenlargement under the new situation.In the context of the Ukraine crisis,the EU has accelerated its enlarge-ment process, not only restarting theaccession negotiations of the WesternBalkan countries, but also grantingcandidate status to Ukraine, Moldovaand Georgia, aiming to promote“geostrategic investment in a stable,strong and united Europe”. Enlarge-ment not only involves budget, struc-tural funds, common agriculturalpolicy and other issues of interest,but also affects decision-making ef-ficiency, making it a new impetus forthe reform of EU institutions.Second, it aims to fill the EU’sgeopolitical and geostrategic voidand wipe off the continent’s securitygray zone, which refers to the EU andRussia’s common neighborhood ofEastern Europe, the Western Balkans,the South Caucasus, the Black Seaand Eastern Mediterranean regions.A s Russia sees these areas as geostra-tegic buffer zones and border zonesof the “EU empire”, the EU needs astrategy to strengthen its influencein these areas, which explains whythe EPC was materialized in a shortperiod of time. In Macron’s view, Brit-ain must become a member of theCommunity. As the second largesteconomy in Europe and a powerfulcountry in military strength, UK’sBrexit has dealt a serious blow to theEU’s geopolitical influence. Türkiye isof strategic importance to Europeansecurity in the Middle East, EasternMediterranean and Black Sea regions.A s the EU is decoupled from its larg-est energy supplier of Russia, it facesa huge challenge of energy supplysubstitution. Countriessuch as Norway, Azerbaijanand Georgia are importantsources of oil and gas forthe EU, and Türkiye playsan important role in termsof infrastructure such as oiland gas corridors and gasterminals.Last but not least, Eu-rope is in urgent pursuitof strategic autonomy inthe face of its increasingdependence on Americandecisions and capabilitieswhen dealing with its ownaffairs. The Ukraine crisishas dealt a heavy blow to(Photo/IC Photo)37the goal of strategic independence of Europe, and Europe strategically re-lies more on the US. Macron warned that “Europe should not be a vassal of the United States”. The European stra-tegic community generally believes that only by offering solutions to end conflicts in its neighborhood, and by making effective strategic responses to the challenges in its neighborhood can the EU have global weight and credibility. The EU’s lack of strategic autonomy is highlighted by its lack of defense autonomy. From the per-spective of A Strategic Compass for Security and Defense released by the EU in 2022, its strategic autonomy is obviously diluted, and most of the increased military expenditure of Eu-ropean countries may still flow to the US rather than to their own military industry.Although the Ukraine crisis is far from over and the US has increased its military presence in eastern Europe, Europe has a relatively di-minished role in US global strategy. America itself is divided over the Ukraine crisis, the role of its Euro-pean allies, climate, energy and other issues. Fearful of increased burden of European security guarantees, theUS expects Europe to increase its ownmilitary and security commitment toUkraine.PROSPECTWill the EPC serve only as an ex-pedient solution to the Ukraine crisis?Or, will it develop into a useful po-litical and security organization thatunite European countries? It dependslargely on the political will of theEuropean leaders. So far, its structure,function, orientation and relationswith the future European security ar-chitecture are yet to be clear and needto be further observed.First, the structure and leadershipcapability. In view of the different pri-orities and expectations of memberstates, the EPC maintains a vaguestrategic direction and runs as an in-formal body in order to guarantee itspracticality. But the informal and non-centralized model makes it hard tobe effective. Leadership is a questionmust be answered for the organiza-tion with 47 member states to providesolutions to problems. In this regard,the European academic communityhas two basic ideas: one is to form astructure with France, Germany, theEU and the UK as the core, whichis the only way to formulate a clearlist of strategies and in line withthe resource capacities of Europeancountries. Another is to establish astructure dominated by the Weimartriangle of France, Germany andPoland, the consideration of which isbased on its institutional maturity, aswell as the need to bridge the rift be-tween East and West Europe over theUkraine and migration crises.Second, its relations with the fu-ture European security architecture.The Ukraine crisis has paralyzed theOSCE. The NATO cannot cover thewhole of Europe in short term. Eu-rope needs a new security frameworkto meet common challenges. It is inconformity with the birth of the EPC.It is not clear, however, whether it willform the foundation of a new securityarchitecture for the continent. A Ger-man foreign policy think tank hasproposed to set up Joint European De-fense Initiative as the new Europeanpillar of NATO. According to theinitiative, NATO’s major European al-lies such as Britain, France, GermanyEuropean Commission President von der Leyen (L), European Council President Charles Michel (C) and Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama (R) attend a press conference to reiterate their commitment to the accession of the Western Balkan countries to the EU, in the Albanian capital Tirana on December 6, 2022.(Photo/Xinhua)38September/October 2023 CONTEMPORARY WORLDand Poland will use their advantage to protect Ukraine and Eastern Euro-pean countries, and take more respon-sibility for future European security.Whether it is the EPC or the above Initiative that will become the future European security architecture, the core is the EU-Russia relations. Yet, France and Germany are at odds with each other on this issue. At the Mu-nich Security Conference in February 2023, Macron said that “to crush Rus-sia has never been France’s position and it will never be”. For Germany, it agreed with France that Russia was an essential player in the future Europe-an security order before the Ukraine crisis, but it changed its position dras-tically after the crisis broke out. On 14 June 2023, the German government issued National Security Strategy stating that Russia is the most grave threat to peace and security in the Euro-Atlantic region in the foresee-able future and German foreign and security policy will adjust to the threat accordingly.Third, the France-Germany rela-tions within the EPC. The relations between France and Germany willbe the key to the EPC no matterwhat shape its future structure takes.France is the largest military coun-try in the EU, with a complete andadvanced system and productioncapacity of military industry, as wellas the ability to manufacture nuclear-powered aircraft carriers, but France’seconomic strength is not enough tosupport European security needs, andits ambitions must be supported byGermany. In the new security environ-ment, France-Germany competitionfor European leadership is on the rise.Germany is likely to break through itshurdles as a “reluctant great power”and define itself as a stronger geo-political and security actor, playing aleading role in EU’s future policy onRussia and Eastern Europe. As a re-sult, France’s status as a political andsecurity power in the EU is bound tobe challenged by Germany’s pursuitof the role of a geopolitical leader.CONCLUSIONThe EPC provides a platform fordialogue and coordination betweenEU member states and non-EUneighbors. Its future developmentfaces two interrelated questions: First,whether Europe’s pursuit of its geo-political role will change the criteriafor EU enlargement. Second, whetherEurope’s new security environmenthas changed the way Europeans thinkabout and pursuit of peace. MarkLeonard, Director of the EuropeanCouncil on Foreign Relations, ar-gues that over the past half century,European countries have developeda concept of freedom based on uni-versalism, rejection of military force,economic interdependence, sharedsovereignty, and the establishment ofEurope as a single entity based on aset of common institutions. And theEU’s response to the Ukraine crisiscould turn the project of peacefulEuropean integration into a securityproject.——————————————Cui Hongwei is Researcher at theInstitute of International Studies,Shanghai Academy of Social SciencesPeople take partin an anti-NATOand anti-Aurora 23military exerciseprotest on April 22,2023 in Stockholm,Sweden.(Photo/Xinhua)39。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Journal of Comparative Economics 36(2008)307–325/locate/jceEU eastern enlargement and foreign investment:Implications from a neoclassical growth modelKateryna Garmel a ,Lilia Maliar b ,∗,Serguei Maliar ba EERC at the National University “Kyiv-Mohyla Academy”,04070Kyiv,Ukraineb Departamento de Fundamentos del Análisis Económico,Universidad de Alicante,03080Alicante,Spain Received 9August 2005;revised 11April 2007Available online 21April 2007Garmel,Kateryna,Maliar,Lilia,and Maliar,Serguei —EU eastern enlargement and foreign investment:Implications from a neoclassical growth modelIn this paper,we study how eastward enlargement of the EU may affect the economies of old and new EU members and non-accession countries in the context of a multi-country neoclassical growth model where foreign investment is subject to border costs.We assume that at the moment of the EU enlargement border costs between the old and new EU member states are eliminated but remain unchanged between the old EU member states and the non-accession countries.In a calibrated version of the model,the short-run effects of the EU enlargement proved to be relatively small for all the economies considered.The long-run effects are however significant:in the accession countries,investors from the old EU member states become permanent owners of about 3/4of capital,while in the non-accession countries,they are forced out of business by local producers.Journal of Comparative Eco-nomics 36(2)(2008)307–325.EERC at the National University “Kyiv-Mohyla Academy”,04070Kyiv,Ukraine;Departamento de Fundamentos del Análisis Económico,Universidad de Alicante,03080Alicante,Spain.©2007Association for Comparative Economic Studies.Published by Elsevier Inc.All rights reserved.JEL classification:E20;F21;F23Keywords:Foreign direct investment;Capital flows;EU enlargement;Neoclassical growth model;Transition economies;Three-country model1.IntroductionOn May 1,2004,eight Central and Eastern European (CEE)transition countries,Cyprus and Malta joined the EU,which had previously been composed of 15developed countries.1This EU enlargement was an unprecedented attempt at political and economic integration in terms of its scope,diversity and possible consequences.The channels through which EU enlargement may affect economies in the region are various:monetary union,foreign investment,migration,trade,etc.2In this paper,we focus on one of these channels,foreign investment.3We argue that this *Corresponding author.Fax:(+34)965903898.E-mail address:maliarl@merlin.fae.ua.es (L.Maliar).1Elsewhere in the text,we therefore refer to the EU existing before the enlargement as the EU15and to the enlarged EU as the EU25.2The monetary-union channel is explored in Kollmann (2004)in the context of a two-country computable general equilibrium model.3By foreign investment,we mean both portfolio investment and foreign direct investment (FDI).0147-5967/$–see front matter ©2007Association for Comparative Economic Studies.Published by Elsevier Inc.All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/j.jce.2007.04.003308K.Garmel et al./Journal of Comparative Economics36(2008)307–325channel is important because there is a major difference between the capital stocks and hence,between the Marginal Productivities of Capital(MPC)of the EU15and the non-EU15transition countries,which is likely to generate large capitalflows from the former to the latter countries.4In the case of previous EU enlargements,the empirical literature shows that poor countries joining the EU ex-perienced a subsequent increase in capital inflows,e.g.,Baldwin et al.(1997),Grabbe(2001).Furthermore,in the wake of the2004EU enlargement,there were major differences in Foreign Direct Investment(FDI)stocks between accession and the non-accession transition countries,see,e.g.,Egger and Pfaffermayr(2002)and Henriot(2003). In the paper,we argue that the these patterns arise because accession of a country to the EU reduces the costs that EU15agents incur when investing in such a country(we refer to these costs as“border costs”).Border costs can be interpreted as“risk to invest”(in a broad sense)and all kinds of costs associated with managing foreign invest-ment(e.g.,cost of acquiring information,cost of monitoring),which is reduced or entirely removed if a country becomes an EU member;the reason is that an accession country takes over the whole legal stock of the EU which includes the four freedoms(free movement of goods,services,labour and capital)and also,a common competition law.We introduce border costs in a multi-country neoclassical growth model.Wefirst consider a two-country variant of the model where one country represents the EU15and the other represents the new accession countries.We assume that border costs between the EU15and the accession countries are eliminated after EU ing this model, we ask:How may EU enlargement affect output,consumption,labour and welfare of the EU15and the accession countries?We then consider a three-country setup,where the three countries belong to the EU15,the accession and the non-accession groups of countries.We assume that at the moment of accession,border costs are entirely eliminated between the EU15and the accession countries but remain unchanged between the enlarged EU and the non-accession countries.In the context of the three-country model,we address the following two questions.First,how can the introduction of poor non-accession countries affect the model’s predictions with regard to the EU15and the accession countries?Second,how may the EU accession of some transition countries affect the remaining(i.e.,non-accession) transition countries?Our analysis is related to recent empirical literature investigating FDI determinants in transition countries.5Fur-thermore,our border costs can be viewed as a measure of distance(in a broad sense)between countries,and are similar to the distance measures used in the FDI gravity literature,e.g.,trade freight costs and tariffs in Brainard(1997).The presence of border costs complicates the solution procedure considerably:our multi-country model has occa-sionally binding inequality constraints,so that equilibrium allocation is in general not interior,and policy functions have a kink.A one-country model with occasionally binding inequality constraints is extensively studied in Christiano and Fisher(2000),however,to the best of our knowledge,similar multi-country models have not been studied yet. To simplify the computation of equilibrium,we use two complementary strategies:one is to reduce the number of Kuhn–Tucker conditions by establishing some properties of equilibrium analytically,and the other is to convert a three-country model into a two-country model by using aggregation theory.In addition,we restrict the admissible set of initial conditions to be consistent with the optimal policy functions;this allows us to reduce the number of state variables in the model.We calibrate the model to match the population sizes and the capital stocks of the EU15,the new accession and non-accession groups of countries,and we compute the transitional dynamics.Our mainfindings are as follows:In the short run,the implications of the model under the non-accession and accession scenarios are similar both qualitatively and quantitatively.To be specific,under both scenarios,a large initial difference in the MPC between the rich EU15 and the poor non-EU15(accession or non-accession)countries leads to massive capitalflows from the former to the latter;this decreases(increases)wages,output and consumption in the EU15(non-EU15)countries.The long-run consequences of the non-accession and accession scenarios are however very different:under the former scenario, residents of the non-accession countries eventually buy out all domestic capital from EU15investors,while under the latter scenario,EU15investors continue to hold a part of the accession country’s capital in perpetuity.Quantitatively, 4Non-EU15countries are those that do not enter the EU15.Similarly,non-EU25countries are those that do not enter the EU25.5See,e.g.,Lankes and Venables(1996),Baldwin et al.(1997),Di Mauro(2000),Grabbe(2001,2003),Buch et al.(2001),Åslund and Warner (2002),Egger and Pfaffermayr(2002),Deichmann et al.(2003),Henriot(2003),Carstensen and Toubal(2004).K.Garmel et al./Journal of Comparative Economics36(2008)307–325309 the latter effect can be very large:in our benchmark model,EU15investors end up owning more than75%of the accession country’s capital.As far as welfare is concerned,our model predicts that the capital trade is beneficial for both the rich EU15and the poor non-EU15(accession or non-accession)countries independently of the scenario considered:the EU15countries gain in welfare because they get additional capital income from their foreign assets,while the non-EU15countries gain in welfare because they can instantaneously raise their living standards.In our model,EU enlargement is a win-win process in the sense that it increases welfare gains from capital trade for both the EU15and accession countries relative to the non-accession scenario.Finally,under the empirically plausible parameterisations,our model implies that the 2004EU accession of the eight transition countries should not significantly affect the economies of the non-accession transition countries.The rest of the paper is organised as follows.Section2discusses the empirical relation between EU enlargements, foreign investment and border costs.Section3develops a dynamic multi-country general-equilibrium model of the EU enlargement where foreign investment is subject to border costs.Section4describes the methodology of the numerical study and presents the simulation results.Finally,Section5gives conclusions.2.EU enlargements,foreign investment and border costsThe history of the European Union(EU)began in1951,when six European countries(Belgium,France,Germany, Italy,Luxembourg and Netherlands)established the European Coal and Steel Community.Over the period from1951 to2004,the EU experiencedfive enlargements:Denmark,Ireland and the UK joined in1973;Greece in1981;Portugal and Spain in1986;Austria,Finland and Sweden in1995;andfinally,Cyprus,Czech Republic,Estonia,Hungary, Latvia,Lithuania,Malta,Poland,the Slovak Republic and Slovenia in2004.In Table1,for each enlargement,we give the population size,total GDP,and GDP per capita of the EU and the accession groups of countries.For thefifth enlargement,we consider two different groups,one including all accession countries and the other composed only of accession countries in transition;the two groups differ in the presence of Cyprus and Malta.Finally,we report the statistics for the group of non-accession transition countries that are EU25-neighbours(Albania,Croatia,FYR Macedonia,Moldova,Belarus,Ukraine,Bulgaria,Romania).Table1Selected statistics for the EU and the non-EU countries:thefive EU enlargementsEnlargement Group of countries StatisticPopulation,×106GDP percapita,×1031995$USGDP–per capitaratioI01.01.1973EU-6(Belgium,France,Germany,Italy,Luxembourg,Netherlands)208.1816.8 1.00 Joined(Denmark,Ireland,UK)64.1112.530.80II01.01.1981EU-9(EU-6,Denmark,Ireland,UK)277.8319.33 1.00 Joined(Greece)9.6410.700.56III01.01.1986EU-10(EU-9,Greece)289.4520.80 1.00 Joined(Portugal,Spain)48.4211.080.52IV01.01.1995EU-12(EU-10,Portugal,Spain)348.6023.74 1.00 Joined(Austria,Finland,Sweden)21.9027.03 1.20V01.05.2004EU-15(EU-12,Austria,Finland,Sweden)378.9827.20 1.00 Joined all(Cyprus,Malta,Czech Rep.,Estonia,Hungary,Latvia,Lithuania,Poland,Slovak Rep.,Slovenia)74.344.650.18Joined only transition(Czech Rep.,Estonia,Hungary,Latvia,Lithuania,Poland,Slovak Rep.,Slovenia)73.574.550.17Non-accession transition EU-neighbours(Albania,Croatia,FYR Macedonia,Moldova,Belarus,Ukraine,Bulgaria,Romania)98.481.510.06Notes.Statistics are computed for the date of the corresponding EU enlargement.The statistic“GDP per capita ratio”is a ratio of the GDP per capita of a group of countries in a row to that of the EU in the corresponding year.Source.World Development indicators(2003),the World Bank.310K.Garmel et al./Journal of Comparative Economics36(2008)307–325As Table1shows,at the moment of accession,the countries joining the EU had on average a lower GDP per capita than the old EU member states did.(The fourth enlargement is an exception here since Austria,Finland and Sweden had higher GDP per capita than the EU average.)In the case of thefifth enlargement,the output difference between the EU15and the accession countries is particularly large:at the moment of accession,the average accession country produced only18%of output of the average EU15country.The empirical literaturefinds that the EU enlargements were accompanied by considerable capital inflows to the accession countries,see,e.g.,Baldwin et al.(1997),Grabbe(2001),Egger and Pfaffermayr(2002).Regarding the first four enlargements,Grabbe(2001)argues that the countries that were furthest behind the EU at the moment of accession(Ireland,Greece,Portugal and Spain)experienced the largest capital inflows.As far as thefifth enlargement is concerned,Egger and Pfaffermayr(2002)document the large anticipatory effects of EU enlargement on FDI:the Eastern European countries that applied to join the EU in1994–1995experienced a significant increase in foreign investment over the period1995–1998.Furthermore,Åslund and Warner(2002)report that in2000,the CEE group of countries(which includes the accession transition countries,and Bulgaria and Romania)had an FDI equal to5.9%of GDP,which is almost four times larger than that of the Commonwealth of Independent States(CIS)group of countries which stood at1.6%.6To understand why the accession countries experience an increase in foreign investment,we shallfirst review some findings from the empirical literature on the determinants of foreign investment.In the transition context,Lankes and Venables(1996)identify the following determinants:the host country’s progress in economic transition,local market size,factor costs,access to EU markets,political stability and regulatory environment.Grabbe(2001)emphasises the importance of such factors as expanded markets,open borders,common regulatory environment and lower transporta-tion costs for cross-border business.Grabbe(2003)adds to the previous list such factors as the visa and Schengen border regimes and greater integration of the accession countries with the EU member states.Deichmann et al.(2003)find a significant impact of social capital,labour skills,infrastructure,trade policy and market reforms on a country’s FDI appeal.Carstensen and Toubal(2004)come to the conclusion that the different attractiveness of Central European versus Eastern European countries for FDI is explained mainly by differences in capital endowments and uncertainty in the legal,political and economic environments.Finally,when becoming an EU member,the country is also in-tegrated into the EU budget rules and gets massive transfers from the EU budget under the heading of“structural policy”(up to a maximum of4%of its GDP).Breuss et al.(2001,2003)find that,first,structural funds have a positive influence on FDI and,second,there is a redistribution of FDI in Europe from the old to the new member states.The redistribution occurs because the cost of enlargement isfinanced primarily not by increasing the total expenditure of the EU budget but by reshuffling the transfers from the former cohesion countries(Greece,Ireland,Portugal and Spain)to the new“poor”countries in Eastern Europe.The empirical literature on FDI determinants suggests why EU accession magnifies FDI inflows in accession countries.Specifically,to be able to join the EU,a country should take a major step toward integration with EU member states:it should adopt the EU’s common political,economic and legislative institutions,the common visa and border-control policies,etc.7In other words,an accession country should become similar to the EU member states.This reduces border costs and makes the country more attractive for foreign investment.In an earlier version of the present paper,Garmel et al.(2005),we provide statistical evidence supporting the hypothesis that the accession countries converge toward the EU member states,as opposed to the non-accession countries.8 In the next section,we present a dynamic general equilibrium model in which the increasing institutional similarity between the EU15and the accession countries reduces border costs for foreign investment.We use the model to 6The CIS members are Azerbaijan,Armenia,Belarus,Georgia,Kazakhstan,Kyrgyzstan,Moldova,Russia,Tajikistan,Turkmenistan,Uzbekistan and Ukraine.7In addition,the accession countries receive EU structural funds which are used to catch up faster with existing EU members(see Breuss et al., 2001,2003).8To be specific,we investigate the evolution of the economic-freedom index for the EU15,accession and non-accession groups of countries over the1996–2004period.The economic-freedom index is designed by the Heritage Foundation and Wall Street Journal to reflect a country’s overall economic situation.We interpret the difference between the groups’economic-freedom indices to be a measure of closeness of their economic environments.Our statistical tests show that,initially,the accession and non-accession countries were similar to each other and different to the EU15countries;however,over the transition period,the accession countries become increasingly similar to the EU15countries and increasingly different from the non-accession countries.K.Garmel et al./Journal of Comparative Economics 36(2008)307–325311assess the consequences of the EU enlargement for the economies of the EU15,the accession and the non-accession countries.3.The modelTime is discrete,and the horizon is infinite,t ∈T ,where T ={0,1,2,...}.There are two countries referred to as the EU15country and the non-EU15country,which are meant to represent the groups of the EU15and the non-EU15countries.The countries are identical in their fundamentals,i.e.,preferences and technology,but may differ in their population and initial endowments.Variables in the EU15country are denoted by letters without superscript,and those of the non-EU15country are denoted by letters with superscript “n ”.The population sizes of the two countries are denoted by v and v n ,and they are constant over time.Capital is mobile across countries,but labour is immobile.We describe only the EU15country;a description of the non-EU15country follows by a formal interchange of variables with and without superscripts.3.1.The EU15countryThe consumer side of the EU15country consists of an infinitely-lived representative agent who can invest both in the domestic and the foreign countries.The agent solves the following intertemporal utility-maximisation problem:(1)max {c t ,h t ,k t +1,φt +1}t ∈T ∞t =0δt u(c t ,1−h t )subject to(2)c t +k t +1+φt +1=w t h t +(1−d)(k t +φt )+r t k t +γr n t φt ,where c t ,h t ,k t +1,φt +1 0,and initial condition (k 0,φ0)is given.Here,c t ,h t ,r t and w t are,respectively,consump-tion,hours worked,interest rate and wage in the EU15country;k t is capital rented to domestic producers;φt is capital rented to foreign producers;δ∈(0,1)is the discount factor;d ∈(0,1]is the depreciation rate of capital.The total time endowment is normalised to one and hence,the term (1−h t )represents leisure.Finally,γ∈[0,1]is a fraction of the non-EU15interest rate,r n t ,which is paid on the EU15capital stock held in the non-EU15country,and it reflects border costs for the EU15investors when investing in the non-EU15country.9The producer side of the EU15country consists of a representative firm producing the output commodity from capital,K t ,and labour,H t ,and maximising period-by-period profits,πt :(3)πt =max K t ,H tF (K t ,H t )−r t K t −w t H t ,where F has constant returns to scale,is strictly concave,continuously differentiable,strictly increasing with respect to both arguments and satisfies the appropriate Inada conditions.petitive equilibriumA competitive equilibrium is defined as a sequence of the consumers’allocations,{c t ,h t ,k t +1,φt +1}t ∈T and {c n t ,h n t ,k n t +1,φn t +1}t ∈T ;a sequence of the producers’allocations,{K t ,H t }t ∈T and {K n t ,H n t }t ∈T ;and a sequence of prices {r t ,w t }t ∈T and {r n t ,w n t }t ∈T such that given the prices:(i)for each country,the corresponding consumer’s allocation solves the utility-maximisation problem (1),(2);(ii)for each country,the corresponding producer’s allocation solves the profit-maximisation problem (3);(iii)all markets clear.9We shall assume that there are costs associated with exporting (barriers,tariffs,transportation)which are at least as high as border costs for foreign investment.Otherwise,rather than investing,foreigners will just export their commodities,which leads to a better profitability.312K.Garmel et al./Journal of Comparative Economics 36(2008)307–325We restrict our attention to a first-order recursive equilibrium such that the countries make all their decisions according to time-invariant policy functions of the current state variables.In order to derive the equilibrium conditions,we shall first note that,in equilibrium,both the EU15and the non-EU15consumers rent some of their capital to producers in their own countries,i.e.,k t +1>0and k n t +1>0for all t .Indeed,if consumers in both countries rented capital to foreign producers,they could have saved on border costs by interchanging some of their capital invested abroad on domestic capital.With this result,the EU15agent’s problem (1),(2)yields the following set of First Order Conditions (FOCs):(4)u 2(c t ,1−h t )=w t u 1(c t ,1−h t ),(5)u 1(c t ,1−h t )=δu 1(c t +1,1−h t +1)(1−d +r t +1),(6)u 1(c t ,1−h t ) δu 1(c t +1,1−h t +1)(1−d +γr n t +1),where condition (6)holds with equality if φt +1>0,and it holds with strict inequality if φt +1=0.Here,and further in the text,y i denotes the first-order partial derivative of function y with respect to argument i .Condition (4)is the standard intratemporal FOC which says that the marginal rate of substitution between consumption and leisure is equal to wage.Equations (5)and (6)are the Kuhn–Tucker conditions.According to (5),if the agent decides to rent capital to foreign producers,φt +1>0,his investment decisions are such that the marginal rate of substitution between his consumption tomorrow and today is equal to the marginal rate of transformation in the home country.As follows from (6),when the agent decides not to invest in the foreign country,the marginal rate of substitution between his consumption tomorrow and today is larger than the marginal rate of transformation in the foreign country after paying border costs.Further,according to (3),the EU15firm’s profit-maximisation conditions are:(7)r t =F 1(K t ,H t )and w t =F 2(K t ,H t ).Finally,the market clearing conditions for capital and labour in the EU15country,respectively,are:(8)K t =k t v +φn t v nvand H t =h t .That is,since capital is mobile and labour is immobile,the capital used in domestic production,K t ,can be rented from both domestic and foreign consumers,while the labour input,H t ,can include only domestic labour.We shall assume that the EU15country has larger initial endowment per capita than does the non-EU15country.Under this assumption,there could exist only capital flows from the EU15to the non-EU15country but not vice versa,i.e.,φt 0and φn t ≡0for all t .As a consequence,the only border costs that matter for our analysis are those affecting investment from the EU15to the non-EU15countries,γ;the border costs from the non-EU15to the EU15countries,γn ,are irrelevant.3.3.EnvironmentsWe analyse four different environments.The first three environments are defined within our baseline two-country setup by varying border costs.We specifically consider infinitely large border costs,positive finite border costs and zero border costs,which imply values of γ=0,γ∈(0,1)and γ=1,respectively.Zero (positive)border costs correspond to the case in which the EU15and the non-EU15countries form (do not form)an economic union.Our fourth environment comes from a three-country variant of the model.To be precise,we assume that,initially,there is one EU15country and two identical non-EU15countries.Subsequently,one of the non-EU15countries forms an economic union with the EU15country,eliminating border costs,γ=1,whereas the other non-EU15country remains outside the union continuing to have positive finite border costs,γ∈(0,1).We show that such a three-country model can be converted into our baseline two-country framework.How can we justify the assumption that accession by a country to the EU reduces border costs?As the empiri-cal literature shows,EU accession leads to a closer integration of an accession country with EU member states:it promotes market reforms,ensures political stability,reduces all kinds of transactions costs,enforces a common reg-ulatory environment,etc.(see Section 2for a discussion).We presume that all such effects simplify the operation of foreign investors in an accession country,which is formally captured by an increase in the rate of return on foreignK.Garmel et al./Journal of Comparative Economics 36(2008)307–325313investment through an increase in the border-cost parameter γ.However,there are other important determinants of foreign investment that are not captured by our assumption of the reduction in border costs;for example,local market size and factor costs (Lankes and Venables,1996)and the EU structural funds (Breuss et al.,2001,2003).To simplify the analysis,we abstract from these issues.Finally,we should point out that in our model,accession of a country to the EU occurs instantaneously:border costs between the EU15and the accession country are fully eliminated at the moment of accession.In reality,the accession process is more sophisticated:firstly,a country applies to join the EU;secondly,the membership is granted;thirdly,the formal accession takes place;and finally,the country is gradually integrated in the EU institutions over the post-accession period.The effects of accession on border costs are therefore extended over a period of time.In particular,there is an anticipatory effect because rational agents foresee the accession and adjust their behaviour correspondingly.In this paper,we make no distinction between the anticipatory,immediate and ex post effects of the enlargement.As a result,the effects of capital flows in our model are likely to be more pronounced and concentrated in time than they are in the data.3.3.1.AutarkyIf border costs are infinitely large,γ=0,then the EU15country never invests in the non-EU15country,(9)φt +1=0for all t,which means that the two countries are in autarky.3.3.2.No non-EU15country joins the EUUnder positive finite border costs,γ∈(0,1),we find φt +1from conditions (5)–(7).Suppose that the Euler equation(6)holds with equality,which implies that r t +1=γr n t +1,so that by taking into account the market clearing condition(8),we have (10)F 1(k t +1,h t +1)=γF 1 k n t +1v n +φt +1v v ,h n t +1 .If there is a positive value of φt +1satisfying (10),then it is a solution;otherwise the solution is φt +1=0.In the latter case,the EU15country does not invest in the non-EU15country because it is less profitable than investing in domestic production.3.3.3.All non-EU15countries join the EUIf the EU15and the non-EU15countries form an economic union,so that border costs disappear,γ=1,capital moves from the former country to the latter country until both countries have the same interest rates,r t +1=r n t +1.The optimal φt +1is therefore a solution to (10)under γ=1.3.3.4.Some non-EU15countries accede the EU,and others do notLet us denote with superscripts o and a variables of the old EU country (the one that constituted the EU before the EU enlargement,i.e.,the EU15)and the new accession country,respectively.We continue to use superscript n to denote variables of the non-EU country,which corresponds now to the non-accession country.As was said,after the EU enlargement,border costs between the old EU and the accession countries become zero,γ=1,and those between the enlarged EU and the non-accession countries remain positive,γ∈[0,1).Although we now distinguish between three different countries,we can still analyse their interactions in the context of our two-country framework.This is possible because,in the absence of border costs,we can replace the old EU and the accession countries with a single representative country by using the aggregation-based construction described in Maliar and Maliar (2003).To be specific,let us assume that the enlarged EU is ruled by a social planner and let us define the social momentary utility function of the enlarged EU by u(c t ,1−h t )≡max c o t ,h o t ,c a t ,h a t 1v +v v o λo u c o t ,1−h o t +v a λa u c a t ,1−h a t (11)s.t.c o t v o +c a t v a v o +v a =c t ,h o tv o +h a t v a v o +v a =h t ,。