2010美国空气质量标准National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS)

中美两国环境空气质量标准比较

万方数据

第15卷第6期

李锦菊等中美两国环境空气质量标准比较2003年12月

护,如哮喘病患者、儿童、老年人等;二级标准以保护 自然生态及公众福利为主要对象,包括防止能见度 降低和防止对动物、庄稼、蔬菜及建筑物等的损害。

美国的一级标准l=j中国的二级、三级标准所保 护的对象相当;美国的二级标准与中国的一级标准 所保护的刑象相当。 1.4污染物项目

第15卷第6期

·标准化·

环境监测管理与技术20Q3年12月

中美两国环境空气质量标准比较

李锦菊,沈亦钦 (上海市环境监测中心,上海200030)

摘要:比较r中美两圈环境空气质量标准的制定依据、功能区划分、标准级别、污染物项目、取值时间和污染物质量

浓度限值等内容。指出美国环境空气质量标准的修订频次高于我国;污染物控制项目较我圈少;标准级别的制定和污染物

高于中国同类标准,美国一级标准

8 h均值(10州拧)与中国二级标

准的l h均值(10 rn∥矗)相同 美国一级、二级标准1 h均值 (o 235 m∥一)高于中国同类标准

美国一级、二级标准的季平均值 (1 5似/一)与中国同类标准相同

美国标准的质封浓 度限值较中国宽松 美国标准的质量浓 度限值较中国宽松

国一级标准臼均值(0 365。∥一) 高于中国同类标准;美国二级标准

3 h均值(1 3耐o)高于中国同类

标准l h均值(o 15。嘴/一)

美嗣标准的质量浓 度限值较中国宽松; 中国标准的质量浓 度限值则更细致 具悍

按年平均、日平均取值时fHJ分别给 出3个级别的质量浓度限值

按年平均、日甲均取值时问分别给 m 3个级别的质量浓度限值

《清洁空气法》于1997年在1971年、1973年、1978 年、1979年、1980年、1987年、1990年等版本不断修 订的基础上重新编制的。 1.2功能区类别

空气指数标准范围

空气指数标准范围一、背景与意义空气质量指数(Air Quality Index,简称AQI)是评估空气质量好坏的指标,它直观地反映了空气中的各种污染物的含量,对指导公众的健康防护和环境保护具有重要意义。

随着工业化、城市化进程的加速,空气污染问题日益严重,因此制定合理的空气指数标准范围至关重要。

它不仅为公众提供必要的信息,以避免或减少户外活动,还为政府和环保部门提供决策依据,以制定和实施有效的污染控制措施。

二、全球主要国家和地区的空气指数标准范围世界各地由于地理、气候、工业结构等因素的影响,空气质量存在差异,因此各国的空气指数标准范围也有所不同。

以下是一些主要国家和地区空气指数标准范围的简要概述:1.美国:美国环保署(EPA)规定,空气质量指数在0-100之间为良好,低于50为优,51-100为良,101-150为不健康到敏感人群,151-200为不健康,201以上为危险。

2.欧洲:欧洲标准对空气质量的要求相对较高。

以PM2.5为例,欧洲的标准是日均值不超过25微克/立方米,年均值不超过20微克/立方米。

3.中国:中国的空气质量指数标准分为六级,一级为优(0-50),二级为良(51-100),三级为轻度污染(101-150),四级为中度污染(151-200),五级为重度污染(201-300),六级为严重污染(>300)。

三、空气指数标准范围的比较与差异各国的空气指数标准范围的差异主要体现在对污染物的种类、浓度限值和评价方法上。

例如,中国的空气质量指数主要关注PM2.5、PM10、SO2、NO2等污染物,而欧洲则更加注重NO2、O3等污染物的控制。

此外,不同国家和地区的标准制定还考虑到本地的气候、地理、人口密度等因素。

四、结论与展望总体而言,各国在制定空气指数标准范围时都遵循了健康优先的原则,并力求在本国特定的环境条件下实现最佳的空气质量。

然而,随着全球气候变化和污染问题的日益复杂化,各国也需要不断更新和完善其空气质量标准,以确保公众的健康和生态的平衡。

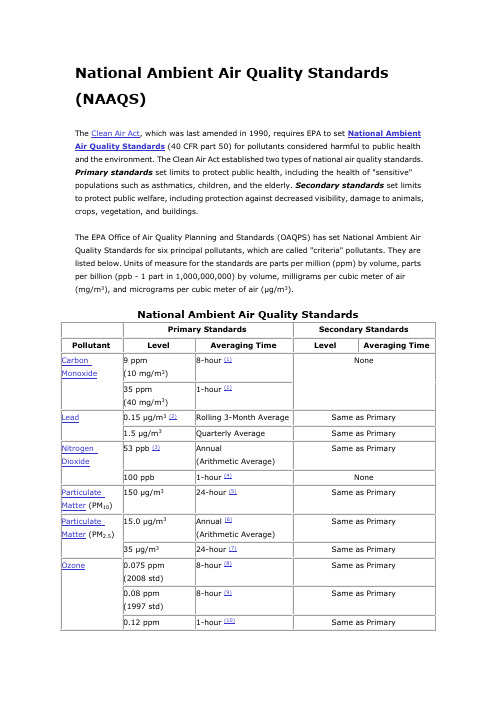

美国国家空气质量标准

National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS)The Clean Air Act, which was last amended in 1990, requires EPA to set National Ambient Air Quality Standards (40 CFR part 50) for pollutants considered harmful to public health and the environment. The Clean Air Act established two types of national air quality standards. Primary standards set limits to protect public health, including the health of "sensitive" populations such as asthmatics, children, and the elderly. Secondary standards set limits to protect public welfare, including protection against decreased visibility, damage to animals, crops, vegetation, and buildings.The EPA Office of Air Quality Planning and Standards (OAQPS) has set National Ambient Air Quality Standards for six principal pollutants, which are called "criteria" pollutants. They are listed below. Units of measure for the standards are parts per million (ppm) by volume, parts per billion (ppb - 1 part in 1,000,000,000) by volume, milligrams per cubic meter of air (mg/m3), and micrograms per cubic meter of air (µg/m3).(1) Not to be exceeded more than once per year.(2) Final rule signed October 15, 2008.(3) The official level of the annual NO2 standard is 0.053 ppm, equal to 53 ppb, which is shown here for the purpose of clearer comparison to the 1-hour standard(4) To attain this standard, the 3-year average of the 98th percentile of the daily maximum 1-hour average at each monitor within an area must not exceed 100 ppb (effective January 22, 2010).(5) Not to be exceeded more than once per year on average over 3 years.(6) To attain this standard, the 3-year average of the weighted annual mean PM2.5 concentrations from single or multiple community-oriented monitors must not exceed 15.0 µg/m3.(7) To attain this standard, the 3-year average of the 98th percentile of 24-hour concentrations at each population-oriented monitor within an area must not exceed 35µg/m3 (effective December 17, 2006).(8) To attain this standard, the 3-year average of the fourth-highest daily maximum 8-hour average ozone concentrations measured at each monitor within an area over each year must not exceed 0.075 ppm. (effective May 27, 2008)(9) (a) To attain this standard, the 3-year average of the fourth-highest daily maximum8-hour average ozone concentrations measured at each monitor within an area over each year must not exceed 0.08 ppm.(b) The 1997 standard—and the implementation rules for that standard—will remain in place for implementation purposes as EPA undertakes rulemaking to address the transition from the 1997 ozone standard to the 2008 ozone standard.(c) EPA is in the process of reconsidering these standards (set in March 2008).(10) (a) EPA revoked the 1-hour ozone standard in all areas, although some areas have continuing obligations under that standard ("anti-backsliding").(b) The standard is attained when the expected number of days per calendar year with maximum hourly average concentrations above 0.12 ppm is < 1.(11) (a) Final rule signed June 2, 2010. To attain this standard, the 3-year average of the 99th percentile of the daily maximum 1-hour average at each monitor within an area must not exceed 75 ppb.。

环境空气质量标准一览

环境空气质量标准一览近年来,环境污染问题日益引起人们的关注。

尤其是空气质量的下降,给人们的健康和生活环境带来了巨大的威胁。

为了保护公众的健康和改善空气质量,各国纷纷制定了环境空气质量标准。

本文将对几个主要国家和地区的环境空气质量标准进行一览介绍。

一、中国环境空气质量标准中国是世界上人口最多的国家之一,也是环境污染问题较为严重的国家之一。

为了解决空气污染问题,中国制定了一系列环境空气质量标准。

其中,最重要的是《环境空气质量标准》(GB 3095-2012)。

该标准将空气质量分为六个等级,分别为一级至六级,一级为最好,六级为最差。

标准中规定了多种空气污染物的限值浓度,如二氧化硫、二氧化氮、颗粒物等。

此外,中国还制定了《机动车排气污染物排放限值及测量方法》(GB 18352.5-2013)等相关标准,以控制机动车尾气排放对空气质量的影响。

二、美国环境空气质量标准美国是全球环境保护的领先国家之一,其环境空气质量标准也十分严格。

美国环境保护署(EPA)制定了一系列环境空气质量标准,其中最重要的是《国家环境空气质量标准》(NAAQS)。

NAAQS将空气质量分为六个指标,包括臭氧、二氧化硫、二氧化氮、一氧化碳、颗粒物和铅。

标准中规定了每个指标的限值浓度,以及相应的监测和评估方法。

此外,美国还制定了《清洁空气法案》(Clean Air Act),以加强对空气质量的管理和保护。

三、欧盟环境空气质量标准欧盟是一个由28个成员国组成的政治和经济联盟,其环境空气质量标准也由欧盟委员会制定。

欧盟环境空气质量标准将空气质量分为四个等级,分别为优良、良好、一般和差。

标准中规定了多种空气污染物的限值浓度,如二氧化硫、二氧化氮、颗粒物等。

此外,欧盟还制定了《大气质量框架指令》(Ambient Air Quality Directives),以协调成员国的环境保护措施。

四、日本环境空气质量标准日本是一个高度工业化的国家,其环境空气质量标准也非常重要。

美国大气污染物排放标准体系特征及借鉴意义

美国大气污染物排放标准体系特征及借鉴意义中国环境学会 2011年06月22日张旭,梅风乔* (环境科学与工程学院,北京大学,北京,100871) Email:*************.cn摘要:大气污染物排放标准是防治空气污染,限制污染物排放的关键措施。

美国的大气污染物排放标准体系以清洁空气法和联邦法规法典为依托,分为固定污染源和移动污染源两个子系,其中固定源标准体系中又以针对新建排放源的NSPS标准和针对有毒有害污染物的NESHAP标准为核心,对常规污染物的现有排放源通过州的实施计划进行控制落实。

整个标准体系技术导向明显,行业划分细致,注重公众健康,对于完善我国现行的大气污染物排放标准体系具有积极的借鉴意义。

关键词:大气污染物排放标准,体系特征,技术原则,行业,借鉴意义。

污染物排放标准是美国为达到环境质量标准所采取的技术强制措施[1]。

大气污染物排放标准主要内涵于清洁空气法(CAA,Clean Air Act)[2]和美国联邦法规法典(CFR,Code of Federal Regulation)[3],属于法律的组成部分。

本文从排放标准所处的政策环境入手,凸显其整体的技术要素,并依固定污染源和移动污染源展开,分别探析其各自的特征,从而得出完善我国大气污染物排放标准体系的建议。

相关政策架构及技术体现[4]美国的清洁空气防治策略规定细致,层次分明。

基于保护人体健康的根本出发点,其以国家环境空气质量标准(NAAQS,National Ambient Air Quality Standard)为基础,结合州的实施计划(SIP,State Implementation Plan)、污染物排放标准、许可证制度等政策措施,对固定源和移动源分别进行控制,其中以排放标准对污染物浓度的减排作用尤为突出,有效地保证了整个大气环境质量。

如图1所示,美国的整个空气污染防治政策布局主要贯穿于横纵多条主线之间,充分体现出“技术导向”的根本特征:其一,从横向角度,图1的右侧主要是国家环境空气质量标准的体现。

国内外环境空气质量标准对比

二级:居住 区、商业交 通居民混合 区、文化区、 工业区和农

村地区,执 行二类标准

Ambient air quality standards

CO

SO2 NO2 O3

Pb

PM2.5

环境空气质量标准GB3095-2012

CO

SO2 NO2 O3

Pb

PM2.5

1、CO的浓度限值比较

欧盟 0.025

0.015 中国一级、美国次级

中国二级 0.035

(mg/m3)

国内外PM2.5年均浓度限值比较

国内一、二级标准 4.00

28.60 韩国

美国 40.00

(mg/m3)

国内外CO小时浓度限值比较

2、SO2的浓度限值比较

美国初级 0.075

中国一级、韩国 0.15

0.1 日本

0.5 中国二级

泰国 0.78

(mg/m3)

国内外SO2小时浓度限值比较

2、SO2的浓度限值比较

WHO 0.02

日本 0.105

5、Pb的浓度限值比较

美国季均 0.15

中国季均 1

0.5 中国、欧盟、韩国年均

(μg/m3)

国内外Pb年均和季均浓度限值比较

6、PM2.5的浓度限值比较

中国一级、美国 0.035

0.04 泰国

中国二级 0.075

(mg/m3)

国内外PM2.5日均浓度限值比较

6、PM2.5的浓度限值比较

美国初级 0.012

TSP

Ambient air quality standards

环境空气质量标准GB3095-2012

初级:初级 标准保护公 众健康,包 括“敏感” 人群: 如哮 喘病人,儿 童和老人

美国室内空气质量标准(英文版)

INTRODUCTIONThe average person sends approximately 90% of their time indoors. Studies haveindicated that indoor air is often dirtier and/or contains higher levels of contaminants than outdoor air. Because of this and increased awareness regarding poor indoor air quality (IAQ), it is not surprising that the number of reported employee complaints of discomfort and illness in non-industrial workplaces is increasing.WHEN DID POOR INDOOR AIR QUALITY BECOME A PROBLEM?Beginning in the mid-1970s, IAQ complaints increased for two reasons. The main reason was the impact of the energy crisis. To reduce heating and cooling costs, buildings were made “airtight” with insulation and sealed windows. In addition, the amount of outside air introduced into buildings was reduced. The second reason is that more chemical-containing products,office supplies, equipment, and pesticides have been introduced into the office environment increasing employee exposure. Thesechanges created IAQ health problems known as Sick Building Syndrome (SBS) or Building-Related Illnesses (BRI).WHAT IS SICK BUILDINGSYNDROME?A workplace is characterized with SBS when a substantial number of building occupants experience health and comfort problems that can be related to working indoors. Additionally,Richard J. Codey Acting GovernorINDOOR AIR QUALITYPublic Employees Occupational Safety andHealth ProgramNovember, 2004the reported symptoms do not fit the pattern of any particular illness, are difficult to trace to any specific source, and relief from thesesymptoms occurs upon leaving the building.WHAT ARE THE SYMPTOMS OF SICKBUILDING SYNDROME?Employee symptoms of SBS may include headaches; eye, nose, and throat irritation; dry or itchy skin; fatigue; dizziness; nausea; and loss of concentration.WHAT ARE BUILDING-RELATEDILLNESSES?A workplace is characterized with BRI when a relatively small number of employees experience health problems. Symptomsassociated with BRI are generally different from those associated with SBS and are often accompanied by physical signs that are identified by a physician and/or laboratoryfindings. Relief from the illness may not occur upon leaving the building. BRI are caused by microbial contamination and/or specificchemical exposures that can result in allergic and/or infectious responses. Microbialcontamiantion occurs when viruses, bacteria,or molds accumulate in areas such as heating, ventilation, and air conditioning(HVAC) systems, water-damaged ceiling tiles and carpets, hot water heaters, andhumidifiers. Chemical exposures can be generated from specific sources within the workplace, such as formaldehyde emitted from newly installed carpets.WHAT ARE THE SYMPTOMS OFBUILDING-RELATED ILLNESSES?Employee symptoms of BRI may include eye, nose, throat, and upper respiratory irritation; skin irritation or rashes; chills; fever; cough; chest tightness; congestion; sneezing; runny nose; muscle aches; and pneumonia. Examples of BRI include asthma; hypersensitivity pneumonitis; multiple chemical sensitivity; and Legionnaires’ Disease.WHAT ARE THE SPECIFIC CAUSESOF SBS AND BRI?The IAQ problems that cause SBS and/or BRI may include:Lack of fresh air;If insufficient fresh air is introduced intooccupied spaces, the air becomes stagnant and odors and contaminants accumulate.Lack of fresh air in occupied areas is thenumber one cause of SBS.Poorly maintained or operated ventilation systems;Mechanial ventilation systems must beproperly maintained and operated based on the original design or prescribed procedures.If these systems are neglected, their ability to provide adequate IAQ decreases. Oneproblem associated with poorly maintainedsystems is missing, overloaded, or inefficient filters. This can cause higher levels of dust, pollen, and cigarette smoke to enteroccupied spaces. Another problem isclogged condensate drain pans and drainlines in HVAC systems, which allow water to accumulate. The accumulation of water can lead to microbial contamination. Poorlymaintained ventilation systems cancontribute to both SBS and BRI.Disruption of air circulation throughout the occupied spaces;The quality of the air depends on the effectiveness of air distribution. If the air circulation is disrupted, blocked, or otherwise does not reach occupied areas, it can become stagnant. File cabinets, bookshelves, stored boxes, dropped ceiling tiles, added office walls, cubicles, and partitions can block or divert the supply of air to occupied spaces.Poorly regulated temperature and relative humidity levels;If the temperature and/or relative humidity levels are too high or too low, employees may experience discomfort, loss of concentration, eye and throat irritation, dry skin, sinus headaches, nosebleeds, and the inability to wear contact lenses. If relative humidity levels are too high, microbial contamination can build up and can cause BRI.Indoor and outdoor sources of contamination;Chemical emissions can contribute to BRI and SBS. Chemical contaminants in an office environment either originate from indoor sources or are introduced from outdoor sources. Common sources include emissions from office machinery or photocopiers; cigarette smoke; insulation; pesticides; wood products; synthetic plastics; newly installed carpets; glues and adhesives; new furnishings; cleaning fluids; paints; solvents; boiler emissions; vehicle exhaust; roof renovations; and contaminated air from exhaust stacks. Contaminants found in indoor environments can also include radon; ozone; formaldehyde; volatile organic compounds; ammonia; carbon monoxide; particulates; nitrogen and sulfure oxides; and asbestos.2WHAT IS CONSIDEREDACCEPTABLE IAQ?The American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers, Inc. (ASHRAE) defines acceptable IAQ as:“air in which there are no knowncontaminants at harmful concentrations asdetermined by cognizant authorities and with which a substantial majority (80% or more) of the people exposed do not expressdissatisfaction.”WHAT CAN BE DONE IF THE AIRQUALITY IS UNACCEPTABLE?In order to understand and resolve IAQ problems and concerns, standard investigative procedures should be followed. Investigating IAQ complaints, however, can be very complicated due to employee concerns, unknown sources of contamination, and the complexities of buildings and their ventilation systems. The New Jersey Department of Health and Senior Services, Public Employees Occupational Safety and Health (PEOSH) Program recommends the following general investigative procedures:•Conduct employee interviews to obtainpertinent information regarding whatsymptoms are being experienced, howmany employees are affected, when theyare affected, where they work, what theydo, etc. - this information may identifypossible IAQ problems;•Review building operations andmaintenance procedures to determinewhen and what type of chemicals are being used during cleaning, floor waxing andstripping, painting, gluing, pesticidespraying, roofing operations, and renovation and construction activities, etc. - alsodetermine when deliveries occur, whichmay generate vehicle exhaust, or iffurniture, drapery, or office equipment hasbeen recently installed;•Conduct a walk-through inspection toevaluate possible sources that maycontribute to IAQ complaints;•Inspect the HVAC system, window airconditioners, office dehumidifiers, etc., inorder to determine if the systems areworking properly and are in good condition;•Review the building blueprints of theductwork and ventilation system todetermine if the system is adequatelydesigned;•Conduct air sampling, if necessary, todetermine if specific contaminants arepresent or if adequate fresh air is beingsupplied.HOW CAN IAQ PROBLEMS BE CORRECTED AND/OR PREVENTED? ENSURE ADEQUATE FRESH AIR SUPPLYThis has been shown to be the single most effective method for correcting and preventing IAQ problems and complaints. To ensure that adequate fresh air is supplied to occupied spaces, the following is recommended:• A preventive maintenance schedule mustbe developed and followed in accordancewith the manufacturer’s recommendationsor with accepted practice to ensure that theventilation systems are properly checked,maintained, and documented.•The preventive maintenance scheduleshould include the inspection andmaintenance of ventilation equipment and/or system, making sure that:−outdoor air supply dampers are opened as designed and remain unobstructed;3−fan belts are operating properly, in good condition, and replaced when necessary;−equipment parts are lubricated;−motors are properly functioning and in good operating condition;−diffusers are open and unobstructed for adequate air mixing;−the system is properly balanced;−filters are properly installed and replaced at specified intervals;−components that are damaged orinoperable are replaced or repaired as appropriate; and −condensate pans are properly draining and in good condition.•To achieve acceptable IAQ, outdoor airshould be adequately distributed to all office areas at a minimum rate of 20 cubic feet per minute (cfm) per person OR theconcentration of all known contaminants of concern be restricted to some specified acceptable levels as identified in ASHRAE’s “Ventiliation for Acceptable Indoor Air Quality” Standard.•To determine if the ventilation system iseffectively providing adequate fresh air,carbon dioxide (CO 2) levels should be measured; ASHRAE sets the standard(ASHRAE 62-1989) of 1000 ppm of CO 2 as the maximum recommended level for acceptable IAQ; CO 2, a byproduct of human respiration, is an indicator of the lack of fresh outdoor air and is not considered harmful at this level.•If possible, gauges should be installed toprovide information on air volumes delivered by supply and return fans.Maintenance staff should be trained to read the gauges and respond appropriately.• A sufficient supply of outside air should beprovided to all occupied spaces. Aninsufficient supply can cause the building to be at negative pressure, allowing untreated air and/or contaminants to infiltrate from outside. This can be determined byobserving the direction of air movement at windows and doors. In order to prevent this problem, the air supply and exhaust system must be properly balanced.•If the office layout is changed (e.g., byerecting partitions or new walls), ensure that adequate air flow and distribution is maintained.•Ventilation system filters should have amoderate efficiency rating (60% or more),as measured by the ASHRAE atmospheric dust spot test, and be of an extended surface type. To determine if the filters have the appropriate efficiency rating,check with the manufacturer. Prefilters (e.g., roll type) should be used before air passes through higher efficiency filters.•Avoid overcrowding of employees, andmake sure that the proper amount of outdoor air is provided based on the number of occupants.ELIMINATE OR CONTROL ALL KNOWN AND POTENTIAL SOURCES OF CONTAMINANTS,BOTH CHEMICAL AND MICROBIAL To Control Chemical Contamination:•Hazardous chemicals should be removed orsubstituted by less hazardous or non-hazardous chemicals, where possible.•Properly store all chemicals to minimizeexposure hazards.4•Use local exhaust ventilation to capture and remove contaminants generated by specific processes where appropriate. Ensure that local exhaust does not recirculate the contaminated air, but directly exhausts the contaminant outdoors. Check with the manufacturer of your office machines for guidance on ventilation requirements for their equipment.•Check to be sure that HVAC fresh air intakes or other building vents or openings are not located in close proximity to potential sources of contamination (e.g., places where motor vehicle emissions collect, downwind of exhausts, cooling towers). If necessary, raise stacks or relocate intakes or exhausts.•Isolate areas of renovation such as painting, carpet installation, etc., from occupied nonconstruction areas, through use of physical barriers and isolation of involved ventilation systems. If possible, perform this type of work in the evening or on weekends. Supplying the maximum amount of fresh air to these areas can assist in the dispersion of contaminant levels.•Use a licensed pesticide applicator for pesticide applications and follow their recommendations regarding appropriate ventilation controls.•Eliminate or reduce cigarette smoke. Smoking restrictions or designated smoking areas should be considered. The air from designated smoking areas must not be recirculated to non-smoking areas of the building.To Control Microbial Contamination:•Promptly detect and permanently repair all areas where water collection or leakage has occurred.•Maintain relative humidity at less than 60% in all occupied spaces and low air-velocity plenums. During the summer, cooling coils should be run at a low enough temperature to properly dehumidify conditioned air.•Check for, correct, and prevent further accumulation of stagnant water by maintaining proper drainage of drain pans under the cooling coils.•Due to dust or dirt accumulation ormoisture-related problems downstream ofheat exchange components (as in ductworkor plenum), additional filtration downstream may be necessary before air is introducedinto occupied areas.•Heat exchange components and drain pans should be accessible so maintenance personnel can easily inspect and clean them. Access panels or doors should be installed where needed.•Non-porous surfaces where moisture collection has promoted microbial growth(e.g., drain pans, cooling coils) should be properly cleaned and disinfected. Careshould be taken to ensure that these chemical cleaners are removed before ventilation systems are reactivated.•Porous building materials contaminated with microbial growth, such as carpets and ceiling tiles, must be replaced or disinfected to effectively eliminate contamination. Note that the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH) recommends that contaminated porous materials should be discarded.5RESOURCESAgencies and organizations that provide information on indoor air quality:New Jersey State Department of Health and Senior ServicesPEOSH Program, 7th FloorPO Box 360Trenton, NJ 08625-0360(609) 984-1863The PEOSH Program has an Indoor Air Quality Standard (N.J.A.C. 100-13) for public employees in New Jersey. The following publications, including a copy of the standard and additional information may be obtained from the above address or the PEOSH web site at www.nj/gov/health/eoh/peoshweb:*PEOSH “Indoor Air Quality Model Program”;*The American Industrial Hygiene Association’s Consultants’ List;*PEOSH Information Bulletin, “Mold in the Workplace, Prevention and Control”;*PEOSH Information Bulletin, “Renovation and Construction in Schools, Controlling Health and Safety Hazards”.U.S. Environmental Protection AgencyIndoor Air Quality Information ClearinghousePO Box 37133Washington, D.C. 20013-7133(800) 438-4318The United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) has various publications on indoor air quality in the home, at schools, and in offices. The publications can be obtained from the address above or from the USEPA IAQ Information Clearinghouse web site at /iaq/iaqxline.html.American Conference of Governmental Industrial HygienistsKemper Woods Center1330 Kemper Meadow DriveCincinnati, OH 45240(513) 742-2020The American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH) has a publication that addresses indoor bioaerosols issues, “Bioaerosols-Assessment and Control” Publication #3180. This publication can be obtained from the above address.American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers, Inc.1791 Tullie Circle, NEAtlanta, GA 30329(404) 636-8400The American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) has two publications that are especially useful:*ASHRAE 62-2001 “Ventilation for Acceptable Indoor Air Quality” Standard, and*ASHRAE 55-1992 “Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy” Standard.The publications can be obtained from the address above or from the ASHRAE web site at / store.ORIG PRINTED 11/94, REV 7/96, REV 10/046PEOSH PROGRAM READER RESPONSE CARDINDOOR AIR QUALITYDear Reader:Please take a few minutes to help us evaluate this publication. Please check the following:Check the category that best describes your position: manageremployeeeducatorsafety professional occupational health professional other (specify)researcherhealth care worker____________________________________Check the category that best describes your workplace:academiamunicipal government labor organization state government municipal utilities authorityother (specify)county government____________________________________Describe how thoroughly you read this publication: cover-to-coversections of interest only (specify)________________________ other (specify)________________________How will you use this information (check all that apply): change the work environment provide information not usedchange a procedure copy and distribute other (specify)assist in researchin training__________________change training curriculum__________________Which section did you find most useful?Which section did you find the least useful and why?Other occupational health topics on which you would like to see the PEOSH Program develop an information bulletin:Other comments and suggestions:C u t h e r e , f o l d i n t h i r d s , t a p e .November 2004NO POSTAGENECESSARYIF MAILEDIN THEUNITED STATESBUSINESS R EPL Y M AILFIRST CLASS PERMIT NO. 206TRENTON, NJPOSTAGE WILL BE PAID BY ADDRESSEESTATE OF NEW JERSEYDEPT OF HEALTH & SENIOR SERVICESPEOSH PROGRAMPO BOX 360TRENTON, NEW JERSEY 08625-9985。

美国大气污染物排放标准概述

美国大气污染物排放标准概述1标准建立简史上世纪40年代后期,洛杉矶等大城市空气质量恶化,联邦政府相继出台针对空气污染物的联邦空气污染法、空气质量法,建立了初步的国家环境空气质量标准。

1970年以后,国家环境空气质量标准(National Ambient Air Quality Standards, NAAQS)和国家有毒空气污染物排放标准(National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants, NESHAP)列入清洁空气法中。

此时联邦政府已经意识到,污染物控制应该与人体健康的安全浓度相适应。

此后20年,联邦环保署(EPA)一直在寻找更好的方法,确定污染物的安全阈值。

1989年,美国国会根据企业年度报告,提出了最初的189种有害大气污染物(HAPs)清单。

同时,EPA提出2000年为时间界限,确定所有HAPs的排放源,并提出排放源的技术控制标准。

1990年,EPA修订了清洁空气法(CAAA),着眼于工业源分类制定标准,修订案可确定HAPs及排放源。

2000年,EPA对所识别各类排放源均建立了标准,并允许源类别增删。

美国大气污染物排放标准大事记2标准体系美国的大气污染物排放标准是将常规大气污染物和有害大气污染物分别制定的。

常规污染物包括已制定国家空气质量标准的颗粒物、CO、O3、NOX、SO2和PM10等,以及尚未制定空气质量标准且基准文件尚未发布的污染物。

常规污染物排放标准适用为现源、制定污染物(现源)、新源3种情况。

新污染源国家实施标准(New Source Performance Standard,NSPS)由EPA制定针对新建或在建污染源排放的常规大气污染物,一旦某污染源按照NSPS管理即成为受控设施。

NSPS有两种形式,1)数值排放标准;2)设施、设备、运行、操作标准。

当污染源不通过一定的排放口进行排放,或该污染源由于经济、技术原因不适用数值排放标准时,采用操作标准。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS)

The Clean Air Act, which was last amended in 1990, requires EPA to set National Ambient Air Quality Standards (40 CFR part 50) for pollutants considered harmful to public health and the environment. The Clean Air Act established two types of national air quality standards. Primary standards set limits to protect public health, including the health of "sensitive" populations such as asthmatics, children, and the elderly. Secondary standards set limits to protect public welfare, including protection against decreased visibility, damage to animals, crops, vegetation, and buildings.

The EPA Office of Air Quality Planning and Standards (OAQPS) has set National Ambient Air Quality Standards for six principal pollutants, which are called "criteria" pollutants. They are listed below. Units of measure for the standards are parts per million (ppm) by volume, parts per billion (ppb - 1 part in 1,000,000,000) by volume, milligrams per cubic meter of air (mg/m3), and micrograms per cubic meter of air (µg/m3).

National Ambient Air Quality Standards

(1) Not to be exceeded more than once per year.

(2) Final rule signed October 15, 2008.

(3) The official level of the annual NO

standard is 0.053 ppm, equal to 53 ppb,

2

which is shown here for the purpose of clearer comparison to the 1-hour standard

(4) To attain this standard, the 3-year average of the 98th percentile of the daily maximum 1-hour average at each monitor within an area must not exceed 100 ppb (effective January 22, 2010).

(5) Not to be exceeded more than once per year on average over 3 years.

(6) To attain this standard, the 3-year average of the weighted annual mean PM2.5 concentrations from single or multiple community-oriented monitors must not exceed 15.0 µg/m3.

(7) To attain this standard, the 3-year average of the 98th percentile of 24-hour concentrations at each population-oriented monitor within an area must not exceed 35 µg/m3 (effective December 17, 2006).

(8) To attain this standard, the 3-year average of the fourth-highest daily maximum 8-hour average ozone concentrations measured at each monitor within an area over each year must not exceed 0.075 ppm. (effective May 27, 2008)

(9) (a) To attain this standard, the 3-year average of the fourth-highest daily maximum 8-hour average ozone concentrations measured at each monitor within an area over each year must not exceed 0.08 ppm.

(b) The 1997 standard—and the implementation rules for that standard—will remain in place for implementation purposes as EPA undertakes rulemaking to address the transition from the 1997 ozone standard to the 2008 ozone standard.

(c) EPA is in the process of reconsidering these standards (set in March 2008).

(10) (a) EPA revoked the 1-hour ozone standard in all areas, although some areas have continuing obligations under that standard ("anti-backsliding").

(b) The standard is attained when the expected number of days per calendar year with maximum hourly average concentrations above 0.12 ppm is < 1.

(11) (a) Final rule signed June 2, 2010. To attain this standard, the 3-year average of the 99th percentile of the daily maximum 1-hour average at each monitor within an area must not exceed 75 ppb.。