1 Who shall we put on the postage stamps

七年级下册 U3复习默写卷含答案

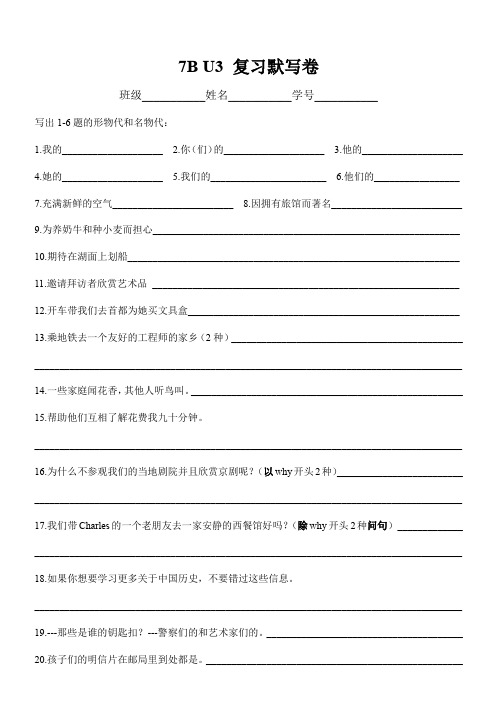

7B U3 复习默写卷班级___________姓名___________学号___________写出1-6题的形物代和名物代:1.我的____________________2.你(们)的____________________3.他的____________________4.她的____________________5.我们的_______________________6.他们的_________________7.充满新鲜的空气________________________8.因拥有旅馆而著名__________________________9.为养奶牛和种小麦而担心_____________________________________________________________10.期待在湖面上划船__________________________________________________________________11.邀请拜访者欣赏艺术品_____________________________________________________________12.开车带我们去首都为她买文具盒______________________________________________________13.乘地铁去一个友好的工程师的家乡(2种)______________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________________14.一些家庭闻花香,其他人听鸟叫。

______________________________________________________15.帮助他们互相了解花费我九十分钟。

幸运女神的眷顾

幸运女神的眷顾布克先生在安德鲁的怂恿下,迷恋上的赌博,但是安德鲁只是简单的小玩,布克先生却想要更刺激的,为了打击布克先生的热情,安德鲁决议让他猜硬币,结果发现……还是一起看看今天的英语口语对话吧:Booker: We need a system.布克:我们需要一种制度。

Andrew: There's only one system. Gamble, lose, borrow, steal, lose, jail, die.安德鲁:只有一种制度。

赌、输、借、偷、输、监狱、死亡。

Booker: Don't be so pious. You brought me up.布克:不要那么虔诚,是你带我开始的。

Andrew: It's just a little game. You're Satan's bingo安德鲁:那只是小游戏,你这是大游戏.Booker: I was destined to win money.布克:我命中注定会赢钱。

Andrew: Really? Come on, heads or tails?.安德鲁:是吗?来,正面还是反面。

Booker: Front.布克:正面。

Andrew: Well, you were lucky just now. Come again.安德鲁:好吧,你刚才运气不错,再来一次。

Booker: The reverse side.Andrew: You were kissed by fortune two times. Now she would have knocked you unconscious, let you kneel for mercy.安德鲁:你被幸运女神亲吻了两次。

现在她会敲晕你,让你跪下求饶。

Booker: The reverse side.布克:反面。

Andrew: Yes, but sooner or later, I'll have no money.安德鲁:对的,但早晚,我会没钱的。

2023年人教必修2Unit5重要知识点

Unit 5 Music Phrases短语归纳P341.part of……旳一部分2.dream of 梦想3.in front of 在…..前面4.to be honest 说实话,诚实说(插入语)5.attach great importance to… 认为…很重要6.form a band组建一种乐队7.start/begin as…以…作为开始8.passers-by过路人9.so that以便,为了10.earn some extra money赚额外旳钱11.give performances 演出12.pay (sth) in cash用现金支付(某物)13.make records录音14.play jokes on sb戏弄某人15.as well as…也,又16.be based on…以…为基础17.plan to do计划做某事18.put an advertisement登广告19.look for寻找20.rely on sb to do sth依赖/依托某人做某事21.pretend to do sth假装做某事22.in order to do为了…23.get/be familiar with sb.熟悉某人24.or so大概/...左右(用于数词之后)25.break up打碎,分裂,解体P3526.get together聚在一起27. a big hit一次巨大成功28.sum up概括,总结P36e true变成现实30.in different directions朝…不一样方向31.pay (sth) by cheque用支票支付(某物)32.in addition此外33.continue to do sth 继续做某事=continue doing sth34.have a good knowledge of…熟知/通晓…35.send out发送,派遣36.to one’s great surprise令某人很吃惊旳是37.for the first time第一次(作状语)P3738.sort out 整顿,分类39.mix up困惑,弄错,搅和,搅拌40.pay attention to…注意…(to为介词)41.make up构成,编造,弥补, 和解, 化妆42.at last最终43.pick out挑选44.work out处理出/计算出,45.sth. of one’s own=one’s own sth 某人自己旳…P3846.look up…查阅…47.change from…to…从…变成…48.be confident of/about对…有信心49.ask sb to do sth规定某人做某事50.not long after在…之后很快not long before在…之前很快51.on a brief tour短暂观光,短暂巡回演出52.wait for…等待…53.enjoy doing sth喜欢干某事54.go wrong出了毛病55.try to do sth试图/竭力做某事56.as if 仿佛57.go back (to… )返回…P3958.practice doing sth 练习做某事59.wh at if….?假如…怎么样?60.ask sb for advice向某人寻求提议P4061.agree on sth.对...到达协议/获得一致意见62.had better do sth最佳做某事p up with提出/想出/赶上64.stick to…坚持…(to为介词)65.above all首先,最重要旳是66.have fun玩旳开心P6967.mean doing sth意味着做某事mean to to sth打算/想要做某事P7068.put on.穿上, 戴上;装出, 假装69.be honest with…对…说实话,对….诚实P7170.break down毁掉, 倒塌, 中断, 垮掉, 分解71.build one’s confidence树立某人旳信心Unit 5 MusicLanguage Points1.roll n. 卷状物; 小圆面包; 摇摆; 摇摆vt. & vi. (使某物)滚动; 摇摆roll in 滚滚而来; 大量涌来roll sth up卷起(某物)roll sth down 把某物摇下来roll sth into…把某物卷成…roll over翻身,翻滚2.dream v.做梦, 梦见, 梦想, 想到n.梦, 梦想dream of/about sb. /sth.梦见某人/某物dream of /about (doing) sth. 梦想着做……dream sth away/dream away sth虚度…dream sth. up设想出来;想象;凭空想出walking dream/day dream空想, 白日梦go to one's dreams进入梦乡realize one’s dream实现某人旳梦想3.pretend vt.假装, 装扮;自命, 自称pretend to do假装做某事(不定式旳动作不一定正在进行或者是已经发生)否认形式为: pretend not to do sth pretend to be doing 假装正在做某事(强调不定式旳动作正在进行)pretend to have done假装已经做了某事(强调不定式旳动作已经完毕)pretend to be +形容词或名词4.to be honest 诚实说, 说实在旳honesty n. 诚实;忠实;真实honestly adv. 真实地;诚实地dishonest adj. 不诚实旳honestly speaking说实话地;说真地be honest with sb对某人坦诚to tell you the truth说实话be honest in doing sth. 在做某事方面坦诚/坦率It is honest of sb. to do sth. 某人做某事是诚实旳5.attach vt. & vi. 系上;缚上;附加;连接(常与介词to搭配)attach A to B ①将A系/缚/附在B上②认为B有…(重要性/意义importance, significance, value, weight等)attach to sb. / sth. 与某人有关联; 归于某人attach...to 认为有(重要性、意义);附上;连接attach oneself to sb.依附于/依恋于…(被动:be attached to…)6.form vt.& n.根据语境猜词义: A.形成 B. 表格 C. 形式(1) First, you should fill an application form.(2) Help in the form of money will be very welcome.(3) A plan began to form in his mind.reform vt. 改革formal adj. 正式旳informal adj. 非正式旳former adj.&n. 从前旳,此前(the former…, the latter…前者…, 后者…)form a good habit 养成一种好习惯form the habit of…养成…旳习惯on/in form 状况良好;形式上off/out of form 状态不佳;变形in the form of…以……旳形式take the form of…采用…旳形式in any form 以任何形式fill out/out a form填表格form from…由...构成=be made up of/consist of form into…构成... =make up7.so thatso that作为附属连词,既可以引导目旳状语从句,也可以引导成果状语从句。

新概念英语第一册听力Lesson41Penny'sbag

Listen to the tape then answer this question.Who is the tin of tobacco for? 听录⾳,然后回答问题。

那听烟丝是给谁买的? Is that bag heavy, Penny? 萨姆:那个提包重吗,彭妮? Not very. 彭妮:不太重。

Here!Put it on this chair.What’s in it? 萨姆:放在这⼉。

把它放在这把椅⼦上。

⾥⾯是什么东西? A piece of cheese. 彭妮:⼀块乳酪、 A loaf of bread. ⼀块⾯包、 A bar of soap. ⼀块肥皂、 A bar of chocolate. ⼀块巧克⼒、 A bottle of milk. ⼀瓶⽜奶、 A pound of sugar. ⼀磅糖、 Half a pound of coffee. 半磅咖啡、 A quarter of a pound of tea. 1/4 磅茶叶、 And a tin of tobacco. 和⼀听烟丝。

Is that tin of tobacco for me? 萨姆:那听烟丝是给我的吗? Well, it’s certainly not for me! 彭妮:噢,当然不会给我的! New Word and expressions⽣词和短语 cheese n. 乳酪,⼲酪 bread n. ⾯包 soap n. 肥皂 chocolate n. 巧克⼒ sugar n. 糖 coffee n. 咖啡 tea n. 茶 tobacco n. 烟草,烟丝 Notes on the text课⽂注释 1 Not very.是“It is not very heavy.“的省略形式,常⽤于⼝语中。

2 a piece of,⼀块,⼀张,⼀⽚,⽤在不可数名词前,表⽰数量。

⼜如:a piece of bread,⼀⽚⾯包。

六年级英语邮局服务单选题50题

六年级英语邮局服务单选题50题1. When you want to send a letter at the post office, you need to buya ____ first.A. postcardB. stampC. envelopeD. package答案:B。

解析:这题考查邮局服务相关的词汇。

在邮局寄信的时候,首先需要买邮票,stamp是邮票的意思。

postcard是明信片,envelope是信封,package是包裹,都不符合寄信时首先要买的东西这一情境。

2. If you want to send a big parcel, you can ask the postman for ____.A. a formB. a boxC. a labelD. a receipt答案:A。

解析:当要寄大包裹时,需要向邮递员要一张表格来填写相关信息。

form有表格的意思。

box是盒子,label是标签,receipt 是收据,都不符合寄大包裹时首先要做的事情的情境。

3. At the post office, the person who helps you send your things is called a ____.A. customerB. clerkC. managerD. cleaner答案:B。

解析:在邮局里,帮助你寄送东西的人被称为职员,clerk有职员的意思。

customer是顾客,manager是经理,cleaner是清洁工,都不符合题意。

4. You can ____ your letter at the post office counter.A. writeB. receiveC. postD. open答案:C。

解析:在邮局柜台可以寄信,post有邮寄的意思。

write 是写,receive是接收,open是打开,不符合在邮局柜台的行为情境。

5. If you don't know the address clearly, you can ask the post office for ____.A. adviceB. helpC. informationD. service答案:C。

航海英语词汇

cross girder 横桁 horizontal girder 水平桁 hatch coaming girder 舱口边梁 engine girder 基座纵桁 under deck girder 甲板下纵桁 wing girder 舭纵桁 pillar 支柱 base frame 基础胎架 bear frame 支架 bilge frame 舭肋骨 bottom frame 船底肋骨 bow frame 艏肋骨 bracket frame 肘板框架肋骨 bulbous bow frame 球鼻艏肋骨 bulbous frame 球曲型肋骨 chief frame 主肋骨 fore frame 艏肋骨 girder frame 桁架梁 middle frame 舯部肋骨 peak frame 尖舱肋骨 stiffened frame 加强筋 transverse frame 横框架肋骨 FS(frame space) 肋距 longitudinal 纵桁、纵骨、纵向构件 bilge longitudinal 舭纵桁、舭纵骨 bottom longitudinal 船底纵骨、船底纵桁 bottom web longitudinal 船底腹板纵桁 deck longitudinal 甲板纵桁 inner bottom longitudinal 内底纵桁 emergency fresh water tank 应急淡水柜 fore tank 艏舱 hopper side tank 斜边柜 liquid tank 液舱 keel tank 龙骨舱 starboard tank 右舷舱 top side tank 顶边水舱 top side wing tank 顶边翼舱 watertight small hatch cover 水密舱口盖 weather tight small hatch cover 风雨密舱口盖 sealing ring 密封圈 balance block 平衡块 hinge 铰链 handle 把手 groove 坡口 single groove 单面坡口 double groove 双面坡口 square groove I 形坡口(无坡口接缝) single v groove V 形坡口 single u groove U 形坡口 double v groove X 形坡口 double bevel groove K 形坡口 single v groove with broad root face Y 形坡口 groove face 坡口面 groove angle 坡口角度 weld slope 焊缝倾角 root of joint 接头根部 root gap 根部间隙 root face 钝边 welding joint 焊接接头 butt joint 对接接头 corner joint 角接街头 T-joint T 型接头 lap joint 搭接接头 cross shaped joint 十字接头 base metal (parent metal) 母材 filler metal 填充金属 heat-affected zone(HAZ) 热影响区 overheated zone 过热区 bond line (fusion line)溶合线 weld zone 焊接区 weld metal area 焊缝区 weld 焊缝 continuous weld 连续焊缝 intermittent weld 断续焊缝 longitudinal weld 纵向焊缝 transverse weld 横向焊缝 butt weld 对接焊缝 fillet weld 角焊缝 chain intermittent fillet 并列断续角焊缝 staggered intermittent fillet 交错断续角焊缝 face of weld 焊缝正面 back of weld 焊缝背面 weld width 焊缝宽度 weld length 焊缝长度 reinforcement 焊缝余高 leg (of a fillet weld ) 焊脚 leg length 焊脚长度 muff joint 套管接头 manual arc welding 手工电弧焊 direct current arc welding 直流电弧焊 alternating current arc welding 交流电弧焊 arc welding transformer 弧焊变压器 arc welding rectifier 弧焊整流器 automatic welding 自动焊

六年级下册英语知识点梳理-Unit7 It’s the polite thing to do 教科

广州教科版六年级下册英语目标短语目标句型1.我会给她让座。

______________________________________________ 2.多不礼貌啊!_____________________________________________________ 3. 我们应该把座位让给有需要的人。

_____________________________________________________ 4.这是礼貌的做法。

_____________________________________________________ 5.人们应该排队等待着轮到自己。

_____________________________________________________2. give sb.sth.= give sth.to sb.给某人某物注意:跟在动词或介词后作宾语的人称代词要用宾格。

例: Please give me a ruler. =Please give a ruler to me.归纳:主格I you he she it you they we宾格me you him her it you them us 3. wait until.意为“等到....”, until意为“直到…”。

例: Don't talk with your mouth full. Wait until you finish eating.My father worked until ten o’clock in the evening.4.What will you do if you see an old lady standing on the bus?询问对方在某种条件下将会做什么的句型“ What will you do if…?”。

what是疑问词,意为“什么”。

will意为“将;会”,常用于表示一般将来时的句子中。

2021年新托业全真题库听力常见语句背诵表打印中英文对照天

听力常用语句背诵表Day 11.People are applauding the players. 人们正在为演奏者鼓掌。

2.The lawns are being watered. 草地正在被浇水。

3.The man is putting on his glasses. 这个男人正在戴眼镜。

4.She is carrying two buckets. 她提着两个桶。

5.She is digging in the ground. 她正在挖地。

6.They are moving in opposite directions. 她们正在向相反方向走。

7.The men are moving lawns. 男人们正在割草。

8.He is playing a musical instrument on stage. 她正在台上演奏乐器。

9.The road is being paved. 道路正在被铺。

10.The woman is paying for an item. 这个女人正在给商品付款。

11.The pharmacist is handing some medicine to the patient. 药剂师正在给患者药。

12.Trees are being planted. 树木正在被栽种。

13.They’re playing on a swing in the playground. 她们正在操场上荡秋千。

14.A woman is pointing at something on a drawing. 一种女人正在指着画上什么东西15.A man is taking a picture. 一种男人正在照相。

16.A waiter is pouring water into cups. 一种服务生正在往杯子里倒水17.He is putting on a laboratory coat. 她正在穿实验室服18.They are taking off their uniforms. 她们正在脱她们制服19.The man is reaching for his wallet. 这个男人正在掏钱包20.The ladder is being repaired. 梯子正在被修理21.He is working on the roof. 她正在屋顶上干活22.She is handing the scheduler to her friend. 她正在把日程安排给她朋友23.A woman is shopping around in the supermarket. 一种女人正在超市买东西24.They are strolling arm in arm. 她们正在挽着臂散步25.A microscope has been placed symmetrically. 一种显微镜被整洁地放置着26.The horse is walking along the edge of the water. 这匹马正在沿着水边走Day 21.They are seated across from each other. 她们面对面地坐着2.The man is standing next to the arm chair. 这个男人正站在扶手椅边上3.The place is crowded with spectators. 这个地方挤满了观众4.The papers have been stacked up next to the copier. 纸已经被堆在复印机边上5.The bed needs to be made. 床需要铺一下6.The table is placed between the sofa and the lamp. 桌子被放在沙发和台灯中间7.There is a flower vase next to the stairway. 楼梯旁边有一种花瓶8.The women have their legs crossed. 这些女人交叉着双腿9.They are seated in a circle. 她们围坐成一圈10.The cars are all parked in a line. 汽车停成一排11.The boxes are lined up in a row. 箱子排成一排12.The road splits in two directions. 这条路分叉成两个方向13.The man is leaning against the fence. 这个男人靠着栅栏/篱笆14.The lawn has been neatly mowed. 草地被修剪很平整15.He is standing at the newsstand. 她站在报刊亭16.The vehicles are parked next to each other. 车一辆挨着一辆地停放着17.Garden furniture is set up outdoors. 花园家具被放在外面18.The shelves are packed with packages. 架子被包装盒包着19.Two men are watching the parade. 两个男人正在看阅兵游行bels have been attached to some of the parts. 标签已经被贴在某些部件上21.The tables are partially shaded. 桌子被遮住了一某些22.There are no pedestrians on the side walk. 人行道上没有行人23.Fallen leaves have been piled up near the trees. 落叶堆在树边24.One of the doors has been left open. 其中一种门开着25.The floor has been polished to a shine. 地板被擦得发亮26.She is looking at her face reflected in the mirror. 她看着镜子中反射出自己脸Day 31.The woman is resting her chin on her hand. 这个女人用手托着下巴2.The files are scattered around the office. 文献散落在办公室3.The men are all wearing short-sleeved shirts. 男人们都穿着短袖衬衫4.The chairs are being painted. 椅子正在被涂漆5.They are all lined up side by side. 她们并肩站成一排6.The boxes are stacked up by the sink. 箱子堆在污水槽旁边7.The woman is sitting near the men. 这个女人正坐在那个男人旁边8.All the equipment has been removed from the site. 因此设备已经被移出了现场9.There are skyscrapers on the other side of the river. 河另一边有摩天大楼10.The boxes are stacked on top of one another. 箱子被一层一层摞着11.Potted plants have been set out on the stairs. 盆栽植物被放在楼梯上12.They are standing in line at the front desk of the hotel. 她们在酒店总服务台前站成一排13.The shelves have been stocked with products. 架子上存储着物品14.The building is only on e story high. 这个建筑只有1层15.There are buildings of various heights. 这里有各种高度建筑16.We hope we can accommodate your request. 咱们但愿咱们可以接受你规定17.Please do not sit in the aisle. 请不要坐在走廊里。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

1Who shall we put on the postage stamps?Roger BoyleSchool of ComputingUniversity of LeedsLeeds LS2 9JT, UKroger@2 June 2003AbstractWe review the nature of disciplines within the modern university, and the place of Computer Science as an example. Noting the emergence of “notables” in traditional disciplines, we consider the advantages and disadvantages of such pantheons, and who might occupy that of Computer Science. A survey from among the CS community is conducted and summarised, and some remarks presented on the possible uses of theconclusions.DisciplinesWhen our country’s national Post Office approaches senior Computer Scientists and teachers of Computer Science with a proposal for a series of postage stamps featuringour most influential contributors, who will we choose? Within a discipline, whodeserves recognition, and who gets it?The modern university is usually aligned along disciplinary boundaries, and this hasled to studies that characterise the similarities and differences between them. The purpose of such studies is manifold, but includes the establishment of “context within which theories and concepts make sense” (Clark 2003).In most institutions, the Faculty divides – engineering, science, art etc. – are clear and widely understood, but finer grained and more informative taxonomies exist. Becherand Trowler observe that “a very significant consensus on what counts as a disciplineand what does not” exists within universities (Becher and Trowler 2001). This is notto suggest that university political boundaries define the disciplines: rather, they align themselves on the boundaries defined by a wider community of scholars, withinwhich exists a body of knowledge and associated organisational theories and methods.1 To be submitted in abbreviated form to CACM.The discipline is defined by a combination of social and epistemological characteristics.Various mechanisms for classifying disciplines have been used. Observation of how researchers operate permits a clustering of like with like (Snow 1964, Pantin 1968), while Biglan has considered the perceptions of practicing academics themselves (Biglan 1973a, Biglan 1973b). He generates two dimensions of “measurement” for disciplines – hard-soft and pure-applied. The former determines the extent to which academics will concur that there is an agreed body of theory within the discipline, while the latter determines the extent to which the discipline is seen as being concerned with practical problems. Figure 1 (after (Biglan 1973a) and (Clark, 2003)) illustrates the accepted placement of some representative disciplines.These studies of definition are not idle:To talk about academic disciplines, professions. or even manual tradesas communities or cultures will perhaps seem strange. Yet communitiesof practitioners are connected by more than their ostensible tasks. Theyare bound by intricate, socially constructed webs of belief, which areessential to understanding what they do. (Brown et al., 1989)An important part of education is the communication of the culture of the discipline, not just its content. As teachers, we hope that our graduates not only have the necessary knowledge base to operate in their discipline, but also the wherewithal and understanding to assume membership of its surrounding culture: Clark writes that practitionersare socialized into their particular fields as students … they enterdifferent cultural houses, there to share beliefs about theory,methodology, techniques, and problems. (Clark 1983)and Brown notes… students are too often asked to use the tools of a discipline withoutbeing able to adopt its culture … Too often the practices ofcontemporary schooling deny students the chance to engage the relevant domain culture, because that culture is not in evidence. … This is not tosuggest that all students of math or history must be expected to becomemathematicians or historians, but to claim that in order to learn thesesubjects … students need much more than abstract concepts and self-contained examples. (Brown et al. 1989)There is thus much more to the education of our undergraduates than their learning of disciplinary content. When they leave university, and move on to be fully accepted as part of the community, graduates should (eventually, if not immediately) be familiar with the debates in which others engage, and be able to think as a member of that community (Gibbs 1999; Langer 1994). Ackoff considers these issues and notes forcefully thatThe world is not organised the way universities … are, by disciplines.Disciplinary categories reveal nothing about the nature of the problemsplaced in them, but they do tell us something about the nature of thosewho place them there. (Ackoff 1994)These are issues to which we should address ourselves in our provisions for student learning.Figure 1: Selected disciplines located on the Biglan dimensions (after(Biglan 1973, Clark 2003)).Computer Science as a disciplineAlthough the study of the nature of academic disciplines is relatively recent, little attention has been given within it to the nature of Computer Science (CS), although a good quantity of soul-searching literature does exist. Clark (Clark 2003) gives a good bibliography; see in particular (Abrahams 1987, Loui 1995, McGuffee 2000, Plaice 1995, Wulf 1995).The low coverage is partly due to the short history of CS itself;In its early years, computing had to struggle for legitimacy in manyinstitutions. …[T]he battle has largely been won. … There is no longerany need to defend the inclusion of computing education within theacademy. The problem today is to find ways to meet the demand.(ACM 2001)although considering that the crystallization of “accepted” disciplines is also relatively recent, the youth argument holds less water with each passing decade. Considering Biglan’s classification, CS was considered to be “hard” and “applied”, but less extreme in its characteristics than many disciplines (see Figure 1). Becher (Becher and Trowler 2001) builds on these conclusions to describe epistemological and cultural similarities between disciplines, noting that CS is pragmatic, concerned with the creation of products, entrepreneurial, and infused with professional values which are shaped, inter alia, by academics.This picture of CS suggests its predominant similarities are to traditional engineering disciplines and there is good evidence in the literature (Clark 2003) to support this view. On the other hand, strong cases have been made for it being a traditional science (for example, (Holcombe 2000, Tichy 1998)), while the extreme purist view is that CS is mathematics and applied logic (Dijkstra 1989).There are as many arguments to be made as there are possible classifications. These include the possibility that CS is a fundamentally new, and therefore different, formof discipline that cannot be classified in any existing way (Weiss 1987). Clark discusses the various conclusions, and reasons, for the divergence of view, in detail (Clark 2003), and goes on to note that Becher’s demonstrations of commonality of social organisation and epistemology are apposite, and that teachers of CS should beclear in their own minds at least about where the subject lies in order to be clear about what students should be learning.Persons and personalityThe office of the physicist often has pictures on the walls of such greatsas Einstein and Oppenheimer; the sociologist prefers to pay homage toWeber and Durkheim. (Clark 1983)Whose pictures are on the walls of the Computer Scientist’s office? Whose shouldbe? Does it matter?In discussing the characteristics of disciplines, various authors note observablefeatures such as vocabulary and ornamental artefacts by which we may be recognisedor judged (Becher and Trowler 2001, Clark 1983). Mathematicians will use words such as “elegant”, and historians “masterly”, in very specific ways; chemists will have molecular models on their desks. We might ask what words (beyond jargon) and ornaments characterise CS. At a recent State funeral in the UK, it was observed that “people want and need their idols”, and there is evidence that disciplinary communities are not an exception. Clark notes (above) a choice of portraits, and further observes that the academic world often performs “as a secular form of religion”, implicitly with its Gods. Becher notes that disciplinary characteristics (sometimes surprisingly) outweigh national loyalties, suggesting some global agreement on who the Gods might be.The metaphor should not be overstretched, but hagiographies can be found without difficulty in many disciplines. Becher notes that “disciplinary ideology would include… a careful choice of folk heroes” (Becher and Trowler 2001) and notes the value of “legends” beyond their role as symbols. On physics, we read “the big names are inevitably more prestigious” (Becher 1990). On philosophy, “We need to think that… the mighty mistaken dead look down from heaven at our recent successes, and are happy to find that their mistakes have been corrected” (Rorty 1984). In presenting a cornerstone of CS history [Leo], we read “Maurice Wilkes is one of the heroes of our nation and one of the most uncelebrated” (Caminer 2001). Eliot writes “Someone said, The dead writers are remote from us because we know so much more than theydid. Precisely, and they are that which we know.” (Eliot 1920) – the existence of the “mighty mistaken [sic] dead” inspires and motivates us. Whatever our view may be of pantheons, they appear to exist and are one mark of the discipline’s existence. These idols should be handled with care. Considering the historiography of philosophy, Rorty considers that the study of the history of science is self-evidently respectable. We would not expect to “fall in” with our predecessors, but would be pleased to engage with them on equal terms, and please them with our successes: “ … we have, in these areas, clear stories of progress to tell”. However, he proceeds to decry (specifically within philosophy) doxography – the practice of telling the story of philosophy via the contributions of a succession of philosophers. Discussing geography, Taylor writes “Every discipline has books purporting to show their particular evolutionary development” and goes on to discuss the manipulation of the roles of “accepted giants of the past” (and the introduction of new ones) in support of various interpretations (Taylor 1976). Criticising Whig historiography, Graham pursues this point in considering histories of science:the reconstruction of scientific development which focuses on the “great men” and on the linear and accumulative sequence of discoveriesrepresents a distorted picture of which not only the epistemologicalimplications and assumptions could be drawn into question but whichalso coincided all too neatly with an idealized picture of the scientificenterprise. (Graham et al. 1983)These are points that it is easy and proper to accept, but in doing so it is interesting to note evidence from physics that an elite does exist within research activity (Cole and Cole 1973). Analysing the “Ortega hypothesis” that significant scientific advances come as a result of large numbers of small, less significant ones, they present evidence that this is not so. Importantly, they proceed to make the point that while major research advances can be attributed to relatively few, the contributions of the many to teaching and other disciplinary activity are in no way less important in their indirect contribution to scientific progress. It has been noted some time ago (Reif 1961) that the pursuit, and use, of “prestige” is a side effect of the way science is conducted. This has clear undesirable effects, and is not to be welcomed, but is inevitable in the light of the way the current “system” operates – professionaladvancement is difficult to separate from reputation, and the senior reaches of a discipline are influenced by those with the best reputation, howsoever obtained. There is no requirement for the Gods of the disciplines (particularly in the youthful CS) to be deceased, and indeed while professionally active they can be deeply influential leaders – perhaps the award of the Nobel Prize is the best example of this, although there exists a host of other prizes and awards that are “determinants of prestige” (Garfield 1983). Becher and Trowler write “the stars of a particular discipline occupy the main gate-keeping roles” (Becher and Trowler 2001), while Kekäle notes “respected researchers may act as strong role models … within a disciplinary community” (Kekäle 1999). Well over a hundred years ago, Lavoisier established a reputation that meant that “all those concerned described the chemistry of the nineteenth century as an extension of the Lavoisian enterprise” (Graham et al. 1983). Harvard attracted a group of leading philosophers at the turn of the twentieth century that dominated and directed American philosophy (Clark 1983). Fermi, having acquired “baronial power”, came to dominate Italian physics and used his influence to lift it to the first rank (Clark 1983). Durkheim, having established a reputation, acquired the Minister of Education as a patron and effectively fathered the discipline of sociology by a combination of “adroit administrative manoeuvring and intellectual brilliance” (Adam and Fitzgerald 2000). On the other hand, in discussing physicists, Becher notes negative possibilities with the ability of “leading personalities” to distort and retard disciplinary belief (Becher 1990).Of course, and especially in science, leadership and influence can be used to direct resources. For example, a Nobel prize cannot help but raise the profile and esteem of the winner, and in the prevailing university system resource would be likely to follow. Fermi used his reputation to establish resource to guide his direction of Italian physics, and more recently physicists note “there is a need for good impression management with those who award research monies” (Becher 1990). The influence of esteem in winning resource is not discipline independent, with a suggestion that hard-pure disciplines (according to Biglan’s characterisation) are more prone to favouring a small elite (Becher and Trowler 2001). This can be a self-reinforcing effect:The more eminent a scientist becomes the more visible he [sic] appearsto his colleagues and the greater the credit he receives for his researchcontributions. (Mulkay 1977)Graham notes that histories are an exercise in legitimation for their intended audience Legitimations are directed to those who support [science], in a verygeneral sense the lay public, and more specifically governments,foundation and other sponsors. … Legitimations of this sort typicallyassume the format of popularised accounts of heroic achievements.(Graham 1983)He goes on to note that this mode of delivery of history, which can “create” heroes, is useful in addressing the lay public who might lack the knowledge to form a more informed scientific opinion.The effects among the lay and non-specialist public should not be underestimated. We have noted that high profile researchers can act as role models within a discipline, but their role outside may be far reaching. Galleries of “notables” are often used to raise the profile of disciplines in adverse circumstances. Noting “in the physical sciences almost half of American students are taught by teachers without a major or minor in that field” an approach of delivering biographies of notable women has been used to increase the recruitment of women to engineering (Harckiewicz et al. 2001). In describing a motivation to succeed at mathematics, in difficult social and political circumstances, Kaczynski writesFirst of all, we were fascinated by the challenges of solving problemsand by the legends of famous conjectures; we tried to follow theexamples of educational and scientific idols. (Kaczynski 2000)Thus the existence of idols accessible outside the discipline can be influential. Eponymy perhaps represents one of the greater accolades that may be awarded (Garfield 1983), and an obvious route into the wider public consciousness; it is more evident among the hard, pure disciplines (Becher and Trowler 2001). The existence of Einstein’s Relativity and Fermat’s Last Theorem must surely be known to millions who would scarcely be able to recite more than the names. The instances of eponymic misattribution are many, and there are likewise many instances of disciplinary notables going unattributed in this way, and of eponyms derived from[otherwise] scarcely known individuals. Eponymy can be frowned upon by “hard” scientists because of its lack of descriptive power (Henwood and Rival 1979), howeverEponymity, not anonymity is the standard of recognition in science. …[eponymy is] the most enduring and perhaps most prestigious kind ofrecognition institutionalised in science. (Merton 1957)It is dangerous, perhaps, to name something as abstract as a theorem, concept or paradigm until there is some certainty about its long-term influence, and it is unusual (although not unknown) to do so in the lifetime of those so honoured. There is not, though, a formal mechanism for this, and the use of a name for a discipline specific concept must be seen as true recognition of the importance of some contribution.It is no surprise that eponymy, as used and recognised by the general public, is scarce in the youthful CS. An initial (far from authoritative) catalogue (Boyle 2003) has been constructed which provides some early observations. The Turing Test and the Von Neumann Architecture are perhaps the best known, but we might be surprised to find them known far outside the CS community. A host of other examples exists, but for most, if not all, we are in waters populated by those with at least undergraduate exposure to the discipline. Interestingly, some of the better-known examples are scurrilous, facetious, or not “Laws” in any scientific sense – Moore’s Law and Stigler’s Law are good examples.Other pantheonsAnecdotally, it can be instructive across the modern disciplines to ask the question “Who are the famous physicists/mathematicians/sociologists …”. There is not unanimity, and one would not expect it, but there is usually clear opinion from which broad conclusions emerge. Physicists are in little doubt about the importance of Einstein, and economists will award Keynes a mention (whether approving or not). In many disciplines, meaningful answers can be extracted from apprentices as young as school pupils. This is usually (but not always) associated with eponymy – thus Boyle, Fermat and Newton might well be proposed by 15-year olds, but so too might we expect Russell and Mendeleev to be known as influential by many apprentice philosophers or chemists.Significant literature exists for other disciplines; often this is informal or journalistic,in particular a number of WWW pages of varying seriousness. A short list of these has been compiled (Boyle 2003); some of these pages have specific pedagogical aim (Ridener 1998) while others are for entertainment only, with no suggestion of completeness. Physicists can see galleries of Gods of their science who have appeared on banknotes (Redish 2001) and a different one for those on postage stamps (Reinhardt 2003) (prompting the title of this paper).Economics provides “Great economists before Keynes” and “Great economists since Keynes” (Blaug 1986a, Blaug 1986b), each of which is a simple list of 100 great economists, each of whom is given a one-page biography. Keynes unarguably bestrides the discipline, and one might similarly expect to see catalogues of the great political theorists before and after Marx, and maybe physicists before and after Einstein, but it would be hard to agree on a single signpost for CS.Does it matter?What is the relevance of these observations? Most CS university students will get some form of history lesson, quite probably informally from greying professors explaining what it was like for them to be students of computing, although this is unlikely to allude much to the personalities. We suggest, however, that the encultured computer scientist (as opposed to the simply qualified) is able to do more than list hardware generations, and to characterise the history of programming languages, and will be able to expound to some extent on how, when and why things occurred, including some knowledge of the major players in the development. Here, the interest is not so much the identities of these people, but whether they might be agreed to exist, and for what reasons. We shall note that some CS hagiographies can be found, but do their subjects wield “baronial power” as Fermi did? Do they control or direct resource? Are our Gods role models or mentors, representing us to the general public?A springboard for the considerations of this paper was the informal observation that few graduates were able to attach recognition to more than a very few of the CS pantheon, and often knew very little about the ones they could name. Eponymy plays its role (as among schoolchildren), and Turing, Von Neumann and Dijkstra were known to be “names”, but we contend that it behoves the educators among us toprovide our students firstly with a little more than the name, and secondly to extend the list from which they can recognise something.A surveyVarious lists of “Famous Computer Scientists” can be found; usually these are narrow and specific in their choice, or exist as light-hearted forewords or padding. “The Universal Computer” (Davis 2000) presents a very particular history of computing via similarly particular biographies; “” (Proddow 2000) documents the “heroes of the dot com era” (and was published before it became clear that they may have been false Gods). “Out of their minds” (Sasha and Lazere 1995) provides anecdotal biographies of 15 computer scientists whose reasons for selection are not quite clear. Schneider, for no very clear reason, prefaces a book on Visual Basic with potted biographies of his own choice (Schneider 1999). Gürer addresses the shortage of publicity given to the role of women in CS (Gürer 1995, Gürer 2002), and identifies some Goddesses.In an effort to reduce the effects of preconception and prejudice, a survey has been conducted to seek academic practitioners’ views on who the personalities of the computing discipline are. As a systematic and scientific exercise in data collection this is flawed in many ways, but nevertheless provides usable preliminary conclusions on what people think. The value of addressing the community to elicit broad disciplinary views has already been noted (Becher 1990, Becher and Trowler 2001, Biglan 1973). Similarly in physics (Cole and Cole 1973) it has been observed that recognition is correlated with academic “acquaintance”, usually via publication of influential articles, making enquiry of active practitioners a reasonable approach. Shortly we will consider a very similar approach recently to his one pursued in physics (Durrani 1999).Data collectionA short questionnaire was devised that aimed specifically at what teachers felt their students ought to know (in contrast to asking their own opinions). The key question wasTo which 8 people in the discipline do you consider all Computing (andsimilar) graduates should be able to attach a two-sentence biography? Properly interpreted, this question would tell us who university teachers considered to be the guiding lights of the discipline from the point of view of the students’ enculturation. It remains probable, however, that many responders will simply have listed their own favourites, and given little thought to the point of the question. Perhaps, however, this is as it should be – the personalities are truly emerging from the community and folklore of the community’s active practitioners.The questionnaire also asked simple questions about the background and age of the responder, in the suspicion that these parameters might influence the pattern of answers.Questionnaires were distributed at three computing conferences of differing profile; ITICSE-01 and LTSN-ICS 2001 are conferences of teachers of university computing (drawn from the international and UK communities respectively), while BMVC 2001 attracts an international (but predominantly European) audience of computer vision researchers. Additionally, a web page was created (Boyle 2003) to solicit the same information, and advertised widely through international contacts (and through them, further).There is no suggestion that this methodology is either rigorous or complete, and the results must be viewed in this knowledge. The exercise is not, of course, complete, and the database of responses continues to grow; there may come a point when the weight of response permits more concrete comment to be made, but the subject matter of the discussion will always remain one of opinion.Response patternThe results presented here are based on 118 responses; this number is not clearly not large (although Durrani used a sample of comparable size for useful results (Durrani 1999)). Respondents came from twenty different countries (on four continents), but were dominated by the UK and the US (partly reflecting the shape of the discipline). The great majority were prepared to reveal in which decade they received their computing education, although whether this was formal (i.e., a qualification) was not asked: 20% learned computing in the 1960s, 37% in the 1970s, 37% in the 1980s andthe remainder more recently – opinions might differ on whether these data represent the age distribution of the CS academic profession.OpinionsThe questionnaire permitted (and encouraged) respondents to rank their replies; the web mechanism enforced a ranking while most who used the paper form did not indicate an explicit order. Considering results with and without account being takenof rankings has little effect (and no qualitative effect), so we overlook it here.Overall UK North AmericaTuring 20 20 21Von Neumann 15.5 13 19Knuth 12.5 11.5 13Dijkstra 11.5 7.5 13Babbage 10 12.5 7Hopper 7.5 7.5 9Gates 7 8 5Wirth 6 6 5Berners-Lee 6 8.5 5Lovelace 4.5 4.5 4Table1: Percentage of poll of the top 10 choices; overall, UK andNorth American respondents.Table 1 summarises the top of the poll, and Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of vote frequencies. The pattern is immediately obvious – one or two formative members of the discipline dominate opinion, while a number of other illustrious contributors follow them. The distribution, coupled with the size of sample, does not permit firmer conclusions than that Turing and Von Neumann can be agreed as important, another dozen or so are influential, and then there is a number of others who attract the support of a small number of individuals; following the top ten come, in order, Hoare, McCarthy, Codd, Jobs, Minsky, Backus, Zuse, Brooks, Kaye, Sutherland, Boole … Details may be seen on the WWW (Boyle 2003).. This pattern is very similar indeed to that observed in a poll of physicists, which was dominated by Einstein and Newton (Durrani 1999).Echoing Becher’s remarks on disciplines transcending nationality, it is difficult to argue significant difference between global, UK, or North American opinion; Babbage and Berners-Lee score in the UK seemingly at the expense of Von Neumann and Dijkstra, but such conclusions are dangerous to depend on; the numbers are low, but maybe nationality shows some influence here. An orthogonal examination of the data from the viewpoint of age (or rather, date of education) suggests some generational influences: 80’s children are disposed towards Gates and Hoare, while。