Cases and dialectical arguments. an approach to case-based reasoning

一分为二辩证看待问题的作文

一分为二辩证看待问题的作文Balancing perspectives is crucial in understanding and addressing complex issues in today's society. 在今天的社会中,平衡各种角度是理解和解决复杂问题的重要关键。

By taking a dialectical approach, we can delve deeper into the nuances of a problem and come up with more comprehensive solutions. 通过采用辩证的方法,我们可以更深入地探讨问题的细微之处,并提出更全面的解决方案。

However, it can be challenging to maintain a balanced view when emotions, biases, and personal beliefs come into play. 然而,当情绪、偏见和个人信念介入时,保持平衡的视角可能会具有挑战性。

On one hand, approaching an issue with a one-sided perspective can lead to tunnel vision and a lack of consideration for alternative viewpoints. 一方面,采用片面的观点来处理问题可能会导致狭隘的视野,对替代观点缺乏考虑。

This can hinder the development of well-rounded solutions that take into account the complexities and intricacies of the issue at hand. 这可能会阻碍制定全面解决方案的发展,这些解决方案考虑了问题的复杂性和错综复杂性。

高考英语作文辩证思维

高考英语作文辩证思维Title: Dialectical Thinking in English CompositionAs an English professor specializing in various types of English writing, I believe that dialectical thinking is a crucial skill that students should develop in their academic writing. Dialectical thinking involves examining and analyzing different perspectives, contradictions, and complexities within a topic or issue. This type of thinking encourages students to critically evaluate information, consider multiple viewpoints, and develop a more nuanced understanding of a subject.In the context of high school English composition, dialectical thinking can be applied in various ways. For instance, when writing argumentative essays, students can explore multiple sides of an argument, acknowledge counterarguments, and ultimately present a wellrounded thesis supported by evidence. This approach not only strengthens their critical thinking skills but also enhances the quality and sophistication of their writing.In addition, dialectical thinking can be utilized in expository writing by examining complex topics from different angles and presenting acomprehensive analysis. By considering various perspectives, students can offer fresh insights, engage readers effectively, and foster a deeper understanding of the subject matter.Furthermore, in narrative writing, dialectical thinking can enrich character development, plot dynamics, and thematic exploration. By juxtaposing conflicting emotions, motivations, or values within a story, students can create more nuanced and compelling narratives that resonate with readers on a deeper level.Overall, the integration of dialectical thinking in English composition not only elevates the quality of students' writing but also nurtures their analytical skills, creativity, and ability to engage with diverse viewpoints. As educators, we should encourage and guide students to embrace dialectical thinking as a valuable tool in their academic and personal growth.In conclusion, dialectical thinking is an essential component of English composition that fosters critical analysis, creativity, and intellectual growth. By incorporating this approach into their writing, students can enhance their ability to construct wellstructured arguments, offer insightful perspectives, and craft compelling narratives. As educators, it is our responsibility to cultivate and nurture dialectical thinking skills in students to empower them as proficient writers and critical thinkers.。

反杜林论的英文书名

反杜林论的英文书名"Anti-Dühring" is a significant work by Friedrich Engels, which serves as a critical examination and refutation of the philosophical, economic, and political theories put forth by Eugen Dühring, a German socialist. The book, originally published in 1878, is not only a critique of Dühring's ideas but also an elaboration of Marxist theory. It is divided into three parts: "Philosophy," "Political Economy," and "Socialism," each addressing different aspects of Dühring's work and Engels' counterarguments.The English title of "Anti-Dühring" remains the same in translation, as it is a proper noun referring to the book itself. However, it is important to note that the title is often accompanied by a subtitle or explanatory text toprovide context for English-speaking audiences. For instance, it might be presented as "Anti-Dühring: Herr EugenDühring's Revolution in Science" to reflect the full titleof Engels' original work, which is "Herrn Eugen Dühring's Umwälzung der Wissenschaft."In the English-speaking world, "Anti-Dühring" is recognized as a foundational text in the development ofMarxist theory, offering insights into the dialectical materialism and historical materialism that form the basis of Marxist philosophy. Engels' work has been influential in shaping the intellectual discourse within socialist and communist movements, and it continues to be studied for itsphilosophical depth and historical significance.The structure of the book is logical and methodical, with Engels systematically dismantling Dühring's arguments and presenting a coherent Marxist alternative. The language used is precise and scholarly, reflecting the academic nature of the debate. Despite its density and the complexity of the subject matter, "Anti-Dühring" remains an essential read for those interested in the history of socialist thought and the evolution of Marxist theory.In summary, "Anti-Dühring" is a pivotal work byFriedrich Engels that engages with and refutes the theories of Eugen Dühring. The English tit le of the book is a direct translation of the original German title, and it is often accompanied by a subtitle for clarity. The book is structured into three parts, each focusing on a different aspect ofDühring's theories, and it is written in a scholarly and precise manner. "Anti-Dühring" is a key text for understanding the development of Marxist thought and the critical dialogue within the socialist movement.。

《反杜林论》读后感1500字

《反杜林论》读后感1500字After reading "The Anti-Dühring," I was left with a profound sense of admiration for Friedrich Engels' intellectual prowess and his ability to dissect and debunk the philosophies of his contemporary, Eugen Dühring. Engels' work not only serves as a scathing critique ofDühring's ideas but also provides a comprehensive analysis of the fundamental principles of dialectical materialism. Through his systematic dismantling of Dühring's arguments, Engels effectively demonstrates the superiority of Marxist theory and the necessity of historical materialism in understanding societal development.One aspect of "The Anti-Dühring" that struck me was Engels' meticulous attention to detail. He carefully dissects each of Dühring's assertions, exposing their fallacies and inconsistencies. Engels' critique is not merely a superficial dismissal of Dühring's ideas but a rigorous examination that reveals the inherent contradictions within his philosophy. This attention todetail showcases Engels' intellectual rigor and his commitment to upholding the scientific method in his analysis.Engels' critique of Dühring's concept of force and motion is particularly enlightening. Dühring argues that force is the primary driving factor behind societal change, while Engels counters this by asserting that it is the development of the productive forces that shapes the evolution of society. Engels' argument is compelling as he highlights the role of material conditions and economic relations in shaping historical development. By emphasizing the importance of the materialist conception of history, Engels underscores the necessity of understanding the underlying economic dynamics that drive societal change.Furthermore, Engels' discussion of the relationship between theory and practice is thought-provoking. He argues that theory and practice are interconnected and mutually reinforcing. Engels asserts that theory is not detached from reality but rather emerges from the practical struggles of the working class. This perspective challengesthe notion that theory is merely an abstract intellectual exercise and highlights the importance of praxis in the development of Marxist theory.Engels' critique of Dühring's utopian socialism is also noteworthy. He exposes the flaws in Dühri ng's vision of an ideal society, arguing that it fails to account for the material conditions necessary for its realization. Engels' critique serves as a reminder that socialism must be grounded in material reality and guided by a scientific understanding of historical development. This rejection of utopianism in favor of a scientific approach is a key tenet of Marxist theory and remains relevant in contemporary discussions of socialism.Overall, "The Anti-Dühring" is a powerful and persuasive critique of Dühring's philosophy. Engels' thorough analysis and systematic dismantling of Dühring's arguments showcase the strength and coherence of Marxist theory. Engels' work serves as a reminder of the importance of rigorous intellectual engagement and the necessity of grounding theory in material reality. "The Anti-Dühring"is a testament to Engels' intellectual prowess and his commitment to advancing the principles of dialectical materialism.。

辩证英语作文

辩证英语作文Title: Embracing Contradictions: A Dialectical Approach to English Composition。

In the realm of language and thought, dialectics offer a powerful tool for examining complex phenomena. By acknowledging contradictions and seeking their synthesis, one can navigate through nuanced perspectives and arrive at a deeper understanding. Applying this approach to English composition fosters not only clarity but also intellectual growth. In this essay, we delve into the principles of dialectical thinking within the context of English writing.To begin with, dialectics compel us to recognize the inherent contradictions present in any topic or argument. For instance, when exploring a controversial issue like climate change, one encounters conflicting viewpoints regarding its causes, impacts, and solutions. Rather than dismissing opposing perspectives, a dialectical approach encourages us to engage with them earnestly. Byacknowledging the validity of diverse viewpoints, we lay the groundwork for a more comprehensive analysis.Moreover, dialectical thinking prompts us to seek synthesis, the integration of seemingly contradictory elements into a cohesive whole. In the context of English composition, this entails crafting nuanced arguments that consider multiple perspectives. For instance, when composing an argumentative essay on the benefits and drawbacks of technology in education, one could acknowledge both its potential for enhancing learning outcomes and its risks of exacerbating inequality. By synthesizing these contrasting viewpoints, the essay attains a higher level of complexity and insight.Furthermore, dialectics emphasize the dynamic nature of ideas and language. Just as reality is in a constant state of flux, so too are our interpretations and expressions of it. This dynamic perspective challenges writers to remain open to new insights and revisions throughout the writing process. Rather than clinging to rigid positions, writers must embrace the fluidity of language and thought, allowingtheir ideas to evolve in response to new information and perspectives.Additionally, dialectical thinking fosters intellectual humility by highlighting the limitations of our understanding. No single perspective can fully capture the complexity of reality, and no argument is immune to scrutiny. Recognizing this, writers must approach their craft with a spirit of humility, remaining receptive to feedback and critique. Through constructive dialogue and engagement with diverse viewpoints, writers can refinetheir arguments and deepen their insights.Furthermore, dialectical thinking encourages us to transcend binary oppositions and embrace complexity. Rather than viewing issues in terms of black and white, right and wrong, we recognize the shades of gray that characterize most phenomena. This nuanced perspective enriches our writing, enabling us to explore the intricacies of human experience with depth and sensitivity.In conclusion, a dialectical approach to Englishcomposition offers a pathway to intellectual growth and insight. By acknowledging contradictions, seeking synthesis, embracing dynamism, cultivating humility, and embracing complexity, writers can elevate their craft and engage more deeply with their subjects. In an increasingly interconnected and complex world, dialectical thinking remains a valuable tool for navigating ambiguity and fostering deeper understanding. As we continue to refineour skills as writers, let us embrace the dialecticalspirit, ever curious and open to the richness of human experience.。

Two-dimensional Quantum Field Theory, examples and applications

Abstract The main principles of two-dimensional quantum field theories, in particular two-dimensional QCD and gravity are reviewed. We study non-perturbative aspects of these theories which make them particularly valuable for testing ideas of four-dimensional quantum field theory. The dynamics of confinement and theta vacuum are explained by using the non-perturbative methods developed in two dimensions. We describe in detail how the effective action of string theory in non-critical dimensions can be represented by Liouville gravity. By comparing the helicity amplitudes in four-dimensional QCD to those of integrable self-dual Yang-Mills theory, we extract a four dimensional version of two dimensional integrability.

2 48 49 52 54 56

5 Four-dimensional analogies and consequences 6 Conclusions and Final Remarks

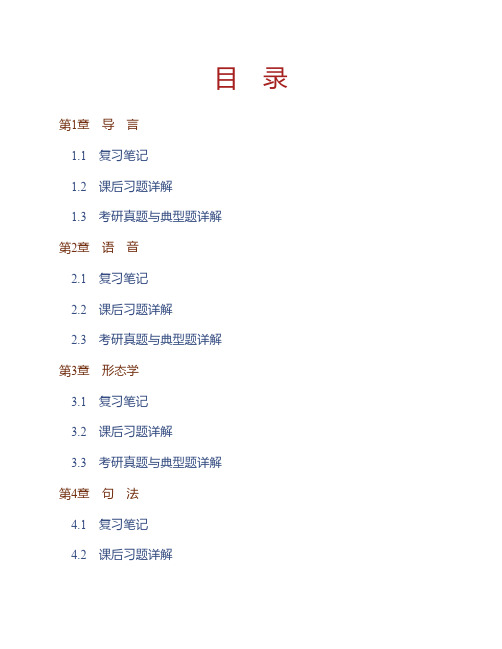

(NEW)刘润清《新编语言学教程》笔记和课后习题(含考研真题)详解

第1章 导 言 1.1 复习笔记 1.2 课后习题详解 1.3 考研真题与典型题详解

第2章 语 音 2.1 复习笔记 2.2 课后习题详解 2.3 考研真题与典型题详解

第3章 形态学 3.1 复习笔记 3.2 课后习题详解 3.3 考研真题与典型题详解

第4章 句 法 4.1 复习笔记 4.2 课后习题详解

III. Scope of linguistics (语言学的研究范畴) 1. Microlinguistics(微观语言学) Phonetics语音学 Phonology音系学 Morphology形态学 Syntax句法学

Semantics语义学 Pragmatics语用学 2. Macrolinguistics (宏观语言学) Sociolinguistics社会语言学 Psycholinguistics心理语言学 Neurolinguistics神经语言学 Stylistics文体学 Discourse analysis语篇分析 Computational linguistics计算语言学 Cognitive linguistics认知语言学 Applied linguistics应用语言学

3. Language is vocal—the primary medium for all languages is sound. 4. Language is used for human communication—it is human-specific, very different from systems of animal communication. 1. 语言是一个系统——其元素非任意排列,而是根据一定规则组合的。 2. 语言是任意的——词与其所指物之间没有内在的联系。 3. 语言是口头的——是所有语言的基本交流形式。 4. 语言是人类用来交流的工具——不同于动物的交流系统。

formal

FormalismFormalism is primarily a view about what it takes to determine the aesthetic characteristics or features or properties of things. Which characteristics are aesthetic? ‘Aesthetic’ is an elastic term. One approach to giving it a sense is simply to give a list of examples of the kind of features that are aesthetic: beauty, ugliness, daintiness, dumpiness, elegance, and so on. A more ambitious approach is to say that the list of aesthetic characteristics is non-arbitrary in virtue of a crucial role that beauty and ugliness play: other characteristics, such as, elegance, are ways of being beautiful or ugly. Either way, it is clear that works of art have many non-aesthetic characteristics, and nature has many aesthetic characteristics. (Formalism is sometimes thought of as a view of the nature of art, but that is probably because a view about aesthetic characteristics is conjoined with an aesthetic view of the nature of art.)Formal and Non-formal PropertiesNow, what of formal aesthetic characteristics? These are sub-class of the aesthetic ones. Rather than offering a definition, we can gain an indication of which aesthetic properties they are by considering debates over various artforms.Clive Bell (1914) and Roger Fry (1920) thought that formal aesthetic features of paintings are those that are determined by the lines, shapes and colours that are within the frame. By contrast, the meaning and representational characteristics of paintings are not entirely determined by what is in the frame but also by the work’s history of production. What a painting means or represents is determined in part by the intentions of the person who made it (Wollheim 1980, 1987). Such intentions are not sufficient, but they are necessary for the meanings or representational properties of paintings. Thus meaning and representation are not formally relevant. The aesthetic formalist about paintings believes that all their aesthetic properties are formal; they are all determined solely by what is in the frame and not at all by their history of production. By contrast, the anti-formalist about paintings believes that all their aesthetic properties are determined in part by their history of production. Sometimes anti-formalists appeal to the context of interpretive practices in which works are embedded, instead of their history of production, or they invoke some combination of interpretive practices and history of production, or some other extrinsic factor. I shall assume, however, that anti-formalists insist on the aesthetic importance of the history of production of works.Eduard Hanslick claimed that musical beauty was determined by structures of sound (1986, chapter 3). On this view, even if music sometimes has meanings, they are of no relevance to its formal aesthetic properties. The emotions leading a musician or composer to make music, and the emotions generated in listeners are formally irrelevant. In a performance of a piece of classical music, for example, the ‘frame’around the sounds that determines formal aesthetic properties is the tapping of the conductor’s baton and the applause (see Cone 1968). That structure of sounds determines the formal properties of the music. Anything outside that, such as the history of production of the sounds or their emotional causes or effects, is aesthetically irrelevant.Form as StructureThere is another sense of form and formal properties that has currency especially in reflections on literature, but also in music, architecture and painting and that is of form as structure. This is a matter of the arrangement of the elements of a work with respect to each other. Consider three cards arranged in a line: the 6 of hearts, the 6 of spades and the 7 of hearts. There is a sense in which they have an ABA structure, and another in which they have and AAB structure. Perhaps they have both. Now consider a painting with three human figures in a line: king in a red cloak, a bishop in a red cloak, and a king in a blue cloak. There is a sense in which it has an ABA structure and a sense in which it has an ABA structure. But note that the AAB structure is formal in the previous sense that it is determined by what is in the frame by the lines, shapes and colours on the surface while the ABA ‘structural form’ is determined by what they represent (king or bishop), and on most plausible views that structure is not determined just by the lines, shapes and colours that are in the frame, but is determined in part by the artist’s intention. So the sense of form as structure does not overlap with the sense of form as the determination of aesthetic features by what is in the frame. Let us put structural form to one side here, interesting though it is.Formalism vs anti-formalismAnti-formalists say that in order to appreciate a work of art aesthetically we must always see that work as historically situated. Aesthetic anti-formalism, with its emphasis on historical determination, has its roots in Hegelian history and philosophy of culture (Kulturgeschichte) that was popular in prewar Germany and Austria. This was imported to English-speaking countries by refugees from Naziism, becoming very influential in English-speaking art-history, and beyond. Consider Earnst Gombrich’s multi-million selling The Story of Art (Gombrich 1950). The anti-formalism is right there in the title! The idea became commonplace that the aesthetic value and even the identity of a work of art depend on its place in the story of art. Contrast Bell, the formalist, who writes ‘…what does it matter whether the forms that move [us] were created in Paris the day before yesterday or in Babylon fifty centuries ago?’ (1914: 45-6).Gotlob Frege famously said that a word only has meaning in the context of a sentence (1967), and similarly most aestheticians would assert that the elements of a work only have significance in the context of the whole work. W. V. O. Quine equally famously said that a sentence only has meaning in the context ofother sentences of the language (1951), and similarly aesthetic anti-formalists assert that a work only has aesthetic significance in the context of other works in the tradition in which the work is located. Aesthetic formalists deny this and insist that works sustain their aesthetic properties by themselves. (There was a similar debate, conducted in different terms, in the Renaissance; see Mitrovic 2004.)Anti-formalists believe that all aesthetic properties are historically determined and that aesthetic judgements should always be made, and experiences always had, in the light of appropriate historical categories (Walton 1970). Formalists deny this. Anti-formalists charge formalists with a naïve belief in the ‘innocent eye’ according to which knowledge of history is irrelevant to the aesthetic appreciation. Formalists celebrate the innocent eye, preferring it to one cluttered with irrelevances. Innocence is sometimes a good thing, they say.Arguments?What can be said in favour of either view? In favour of anti-formalism, Gombrich put forward an imaginary example of physically identical works by different artists and invited us to judge that they are aesthetically different (Gombrich 1959: 313). Philosophers like Danto (1964) and Walton (1970) followed suit. Such arguments are supposed to show that a work’s physical nature does not suffice for its aesthetic properties and that history also plays a role. But the appeal to imaginary examples has limited dialectical efficacy. Fanciful thought experiments sometimes involving Martians are supposed to generate possible examples of physically identical artworks with different aesthetic properties; but whether such cases are really possible is far from uncontroversial. The dialectical pressure exerted by such examples is minimal since formalists and anti-formalists will simply interpret the examples differently. Physically identical cases with different histories may have other interesting differences. For example, they might differ in originality; but that difference may not contribute to a difference in their beauty, elegance or delicacy that is, it may make no aesthetic difference. Or so the formalist will say, and merely imaginary examples will not sway them. Similarly, it is controversial whether being a fake makes an aesthetic difference.Arguments for or against formalism should probably be less purely philosophical and involve more attention to actual cases. The apparently abstract metaphysical issue about what it takes to determine aesthetic properties is probably not answerable without practical critical engagement with works of art in various art forms. Here it is worth transgressing disciplinary boundaries. This need not mean the vacuous kind of ‘inter-disciplinarity’ that is mere deference to the apparent authority of another discipline (so as to avoid the authority of ones own!). It can be an active engagement with the subject matter of both disciplines with whatever genres of intellectual thought are available (so long as the disciplines really do engage with the subject-matter, rather than being an excuse for undisciplined philosophy).It is likely that the issue or issues over formalism needs to be discussed artform by artform; there may be no one correct view that applies universally. And even within artforms, it may be that no general theory is right.Moderate FormalismBoth formalism and anti-formalism have something to be said for them, and yet both also seem too extreme.A possible middle course is what we might call ‘moderate formalism’ (Zangwill 2001). On this view, many aesthetic properties are formal and many are not; and many works have only formal properties and many do not have only formal properties. Moderate formalism admits some, and indeed many non-formal properties of works. For example, marching music or religious music is music with a non-musical function; it is music for marching or praying; but the way it realizes that extra-musical function may be part of its aesthetic excellence. This is unlike music that is for shopping: there the question is simply: ‘Does it make people buy more?’, or perhaps: ‘Does it make shopping more pleasant?’ Shopping music is not the aesthetically appropriate expression of the activity of shopping in the way that music may be the appropriate aesthetic expression of marching or praying. Sometimes musical beauty arises when music serves some non-musical function or purpose in a musically appropriate way. The music has a certain non-musical function and the aesthetic qualities of the music are not separate from that function but are an expression, articulation or realization of it. This is what Kant calls ‘dependent’ beauty (1928, section 16). Similarly, there can be a representation which is beautiful, elegant or delicate as a representation, and a building may be beautiful as a mosque, station or library.So non-formal aesthetic properties are important. Bell, Fry and Hanslick overshot in denying that. However, there are many aesthetic properties that are purely formal, and there are many purely formal works. Some paintings are entirely abstract and quite a lot of music is ‘absolute’. Moreover, most representational paintings have formal aesthetic features among their other aesthetic features. Extreme anti-formalism, which denies the existence of formal aesthetic properties and purely formal works, goes too far. Moderate formalism insists on the importance of both formal and non-formal properties.See also AESTHETICISM, ART AND THE SENSES, BELL, DANTO, FORGERY, GOMBRICH, HANSLICK, REPRESENTATION, WALTONBIBLIOGRAPHYClive Bell 1914. Art. London: Chatto and Windus.Edward Cone 1968. Musical Form and Musical Performance. New York: Norton.Arthur Danto 1964. ‘The Artword’. Journal of Philosophy 61: 571-584.Gotlob Frege 1967. ‘The Thought: a Logical Inquiry.’ In Philosophical Logic (ed.) P. F. Strawson.Oxford: Oxford University Press: 17–38.Roger Fry 1920. Vision and Design. London: Chatto and Windus.Ernst Gombrich 1950. The Story of Art. London: Phaidon.Ernst Gombrich 1959. Art and Illusion. London: Phaidon.Eduard Handslick 1986. On the Musically Beautiful. Indianapolis: Hackett.Immanuel Kant 1928. Critique of Judgment, transl. Meredith. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Branko Mitrovic 2004. Learnng From Palladio. New York: Norton.W.V.O. Quine 1951. ‘Two Dogmas of Empiricism’. In From and Logical Point of View. Cambridge Mass.: Harvard University Press: 20-46.Frank Sibley 1959. ‘Aesthetic Concepts’. Philosophical Review LXVII: 421-450Kendall Walton 1970. ‘Categories of Art’. Philosophical Review LXXIX: 334-367.Richard Wollheim 1980. ‘Seeing-In, Seeing-As and Pictorial Representation’. In Art and Its Objects.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, second edition: 205-226.Richard Wollheim 1987. Painting as an Art. London: Thames and Hudson.Nick Zangwill 2001. The Metaphysics of Beauty. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Cases and dialectical argumentsAn approach to case-based reasoningBram Roth1 and Bart Verheij21 Universiteit Maastricht,BramRoth@2 Rijksuniversiteit GroningenAbstract.Case-based reasoning in the law is a reasoning strategy in whichlegal conclusions are supported by decisions made by judges. If the case athand is analogous to a settled case, then by judicial authority one can argue thatthe settled case should be followed. Case-based reasoning is a topic whereontology meets logic since one’s conception of cases determines one’sconception of reasoning with cases. In the paper, it is shown how reasoningwith cases can be modelled by comparing the corresponding dialecticalarguments. A unique characteristic thereby is the explicit recognition that it isin principle contingent which case features are relevant for case comparison.This contigency gives rise to some typical reasoning patterns. The present workis compared to other existing approaches to reasoning by case comparison, andsome work on legal ontologies is briefly discussed regarding the role attributedto cases.1 IntroductionCase-based reasoning is a common type of argumentation in the law, in which legal conclusions are supported with decided cases. If some decided case is sufficiently similar to the case at hand, then under the doctrine of stare decisis one should not depart from that decision, and the same conclusion should hold.The principle of stare decisis holds that in settling new cases judges tend to adhere to prior decisions, in the sense that once a question of law is decided, the decision is normally not departed from afterwards. There are a number of reasons to adhere to earlier decisions. First, courts are often formally bound by decisions made by courts higher up in the hierarchy and by their own decisions (cf. Cross 1977, pp. 103f.). Second, a departure from settled cases would make judicial decisions uncertain and unpredictable, so that one could never be sure about the status of one’s legal claims in court. Third, it is fair and just to treat all individuals equally under the law, and to make no difference between people in similar cases. Fourth, adhering to decisions turns out to be an economic and efficient practice (Bankowski 1997, p. 490).Different methods to adhere to decisions have been described in the literature (Llewellyn 1960, pp. 77-84), and two of them will be discussed next: rule extraction and case comparison.In the first method the reasons underlying the conclusion are isolated, the reasons and conclusion are generalised (or ‘universalised’, cf. Hage 1997, p. 47; MacCormick 1987, pp. 162f.) into a rule that can explain the outcome. This mechanism is called the ‘rule extraction method’ for short.The second method of adhering to a decision is by assigning the corresponding legal conclusion to the new case as an authoritative example (cf. Ashley 1990, pp. 11-12; Aleven 1997, pp. 58; Oliphant 1928, pp. 144f.). If the decided case is ‘sufficiently similar’ to the case at hand, then one can argue by analogy and judicial authority that the decided case should be followed and that the same decision should be taken once more.The methods of rule extraction and case comparison can be presented schematically as a list of reasoning steps, as in Figure 1. The figure illustrates that there are strong relations between both methods, in the sense that they involve comparable reasoning steps.Rule extraction method (1) Extracting rules from decided cases(2) Showing that rule conditions are satisfiedCase comparison method(1) Selecting relevant case facts(2) Establishing an analogy betweencases(3a) Applying extracted rules to the case at hand(3b) Pointingout exceptions toextracted rules(3a) Followingdecided cases inthe case at hand(3b)Distinguishingdecided casesfrom the case athandFigure 1: the methods of rule extraction and case comparison Our discussion of the two methods to adhere to decisions show that case-based reasoning is a topic where ontology meets logic. The two methods correspond to different ontological conceptions of cases that determine different logical analyses of reasoning. When cases are considered as authoritative sources of rules (as in the rule extraction method), reasoning with cases only differs from rule-based reasoning in the phase of rule extraction. After that phase, the extracted rules are applied, just like other rules. From an ontological point of view, the rule extraction method treats cases basically as sets of rules. In the method of case comparison, cases are considered differently, namely as authoritative sources of arguments and decisions. Cases are treated as wholes during all phases of reasoning. Ontologically, the case comparison method views cases basically as sets of arguments and decisions.In the present paper, we have chosen the case comparison method as the basis for modelling case-based reasoning. The model is informally presented. Roth (2003) gives further details and a formal elaboration.2 Dialectical argumentsTo arrive at a systematic analysis of cases, it is convenient to have a graphical representation of the argumentation in the cases. To this end tree-like structures are introduced, called dialectical arguments; cf. Verheij’s (2000; 2001; 2003) naïve dialectical arguments and Loui’s (1997) and Loui and Norman’s (1995, p. 164) records of disputation. Dialectical arguments consist of statements that support or attack other statements, the support and attack relations being represented by arrows. Here is a simplified example for the domain of Dutch dismissal law.At the top of this figure one finds the legal conclusion that the dismissal can be voided, to which a judge can decide on the basis of article 6:682 of the Dutch Civil Code (art. 6:682 BW). The statement in the middle is that the dismissed person has always behaved like a good employee, a general obligation for employees that is codified in article 6:611 of the Dutch Civil Code (art. 6:611 BW). An arrow upwards indicates that the conclusion that the dismissal can be voided is supported by the statement that the dismissed person has always behaved like a good employee. This statement is in turn supported by the statement that the employee always arrived on time for work.Conclusions cannot only be supported, but they can be attacked as well. Attacks are represented by arrows ending in a solid square. In the following figure one finds an example of this.Here the conclusion that the dismissal can be voided is attacked by the statement that there is a pressing ground for dismissal according to article 6:678 of the Dutch Civil Code (art. 6:678 BW).It is a key feature of the present approach that it can also be supported and attacked that a statement supports a conclusion (cf. Toulmin’s warrants, 1958, pp. 98f.), or attacks it (Hage 1997, p. 166; Verheij 1996, pp. 200-201; Pollock 1995, pp. 41 and 86; Pollock 1987, p. 485).A step forward to deal with this is to treat it as a statement itself that the conclusion is supported or attacked (cf. Verheij’s D EF L OG, 2000, pp. 5f.l; 2003; see also Verheij 1999, pp. 45f.). Accordingly, one can represent by an arrow pointing at another arrow that it is supported or attacked that a statement supports or attacks a conclusion. This gives rise to a kind of entanglement of dialectical arguments (Roth 2001, pp. 31-33). An example is in the following figure.At the top of this figure one finds the conclusion that there is a pressing ground for dismissal according to article 6:678 of the Dutch Civil Code. The conclusion is supported by the statement that the employee committed a serious act of violence. However, it is attacked that having committed a serious act of violence supports that there is a pressing ground for dismissal. The attacking statement is that the employee acted in self-defence, which is a general ground of justification according to article 41 of the Dutch Penal Code (art. 41 Sr). As a result, on the sole ground that the employee committed a serious act of violence, the conclusion does not follow that there is a pressing ground for dismissal.It can also be supported that a statement supports or attacks a conclusion. An example is in the following figure.Here the statement is made that the violent act was directed against the employer. This statement supports that having committed a serious act of violence supports that there is a pressing ground for dismissal, in accordance with article 6:678 of the Dutch Civil Code (art. 6:678 BW).Dialectical arguments will be used as a convenient graphical representation of the argumentation in cases, but the question which conclusions follow is not answered by interpreting dialectical arguments regarding the status of the statements involved (cf. Verheij’s dialectical interpretations, 2000, 2003).3 Modelling case-based reasoning by case comparisonIn this section reasoning by case comparison is modelled as a variant of reasoning a fortiori that involves dialectical arguments. The relevant case features appearing in these dialectical arguments are given by what is called a comparison basis. It is explained under which conditions a – possibly contradictory – set of settled cases can help decide a problem case.3.1. Case comparisonIt is the purpose of case comparison to determine whether a settled case can be followed in a problem case. Intuitively one can certainly follow a settled case where, if there is at least as much support for the conclusion in the problem case. Then, by a kind of reasoning a fortiori, the conclusion should hold again.The support for a conclusion is determined by the dialectical argument for it. In this connection we will use the term dialectical support for a conclusion. Case comparison will come down to comparing dialectical arguments regarding the dialectical support for their conclusion.In the following a number of examples of increasing complexity are given.Problem caseIn this figure there is a settled case on the left where the conclusion (c ) was drawn that a person’s dismissal could be voided, as indicated by the plus sign. On the right there is a problem case where this conclusion is an issue, as indicated by the question mark.In both cases the conclusion (c ) that the dismissal can be voided is supported by the statement (a ) that the person has always behaved like a good employee. The conclusion c is attacked by the statement (b ) that the employee committed a serious act of violence. In the problem case the conclusion c is also supported by the statement (d ) that the working atmosphere has not been affected by the dismissal. As a result, there is more dialectical support for c in the problem case, so that it should follow there as well.Another example is in the following figure.Problem case In the settled case the conclusion c is attacked by the statement (e ) that the employee has a criminal record. Together with the difference d already discussed, this means that there is more dialectical support for c in the problem case. As a result, the conclusion (c ) that the dismissal can be voided holds again.Dialectical arguments can have a more complex structure. An example is in the following figure.In this situation there is more dialectical support for the statement a in the problem case. In accordance with this, there is more dialectical support for conclusion c in the problem case than in the settled case, so that the conclusion can follow in the problem case as well. Note that for concluding to the outcome that there is more dialectical support for c in the problem case, it does not matter how the conflict with regard to the intermediate a is to be resolved.It can itself be supported or attacked that one statement supports or attacks another. An example is in the following figure.In this situation there is less dialectical support for the statement that b attacks c in the problem case, due to the attack by the statement (l) that the violent act took place in an agitated atmosphere. As a consequence, the problem case provides more dialectical support for conclusion c than the settled case, so that the conclusion can follow in the problem case as well. Note that for concluding to this result it is not necessary to resolve the conflict with regard to the attack by b.3.2. The comparison basisWhen comparing dialectical arguments one finds different types of statement. The conclusion at the top of these dialectical arguments tends to be the statement of an abstract legal state of affairs. At the bottom of the arguments one normally finds statements of non-legal and concrete facts.Not all these states of affairs are relevant for the purpose of case comparison. The mere fact that John smashed a window, for example, can be irrelevant for the purpose of comparing his case with another case where liability for damage is an issue. At this point a distinction is therefore postulated between relevant and irrelevant states of affairs. From this point onwards all statements corresponding to relevant states of affairs will be called factors, to stress their role in case comparison.1In general it is disputable which statements are factors and which are not. In other words, in the law it depends on a contingent choice which factors are taken into account when comparing cases. Among other things this choice will depend on the legal domain under consideration, such as dismissal or trade secret law.1 Cf. the ‘factors’ in HYPO and CATO (cf. Ashley 1990, pp. 37-38).Some factors have the intuitive property that what supports them can be ignored for the purpose of case comparison, and that for this purpose all that matters is whether or not they can be derived. By definition these factors form a set called the comparison basis, and the factors in this set are called basic.2In the figure below the comparison basis is visualised by drawing a line of division through the dialectical arguments. Statements above the line correspond to relevant states of affairs that have to be considered for the purpose of case comparison, while states of affairs below the line can be ignored. If the comparison basis is chosen as in the figure, then the two cases are comparable regarding their dialectical support for the conclusion(c) that the dismissal can be voided.The following figure shows a different choice for the comparison basis in the same situation, according to which the supporting factors f and h are relevant as well. In other words, it makes a difference now whether the employee was always dressed properly, or always arrived on time. As a result, the two cases are now not comparable regarding the dialectical support for the conclusion.These figures show that the comparison outcomes depend on the particular division made between factors and non-factors. They also illustrate the point that it is disputable which statements will count as basic factors.2 Cf. the ‘base-level factors’ in CATO (Aleven 1997 pp. 23 and 47).3.3. The entangled factor hierarchyLet us consider all factors that follow from the comparison. Together these factors make up a representation of the argumentation pertaining to some domain of law: an ontology for the domain under consideration. An example of such a representation is depicted in the figure below.Entangled factor hierarchy (part)The representation thus obtained is similar to the so-called ‘Factor Hierarchy’ employed by CATO (Aleven 1997, pp. 44-45) as a case-independent knowledge structure. However, in contrast with CATO the present approach also allows for supporting and attacking statements of support or attack, which is why the present structure is called an entangled factor hierarchy (Roth 2001, pp. 31-33)3.4. Which settled cases are relevant?It is shown next how one can compare a number of cases regarding their dialectical support for some conclusion, and use the comparison to select the settled cases that are relevant to resolve a given problem case.The settled cases are ordered regarding their dialectical support, which is represented graphically by placing the cases as dots on a line.– Settled Case1 +– – – + + Settled Case2 – +In this figure the small circles represent settled cases. The conclusion of each settled case is indicated by a plus or a minus sign, standing for a conclusion (say c ) or its opposite conclusion (¬c ), respectively. From left to right there is increasing dialectical support for the conclusion (c ).ProblemCase1 is a problem case which has two positively decided cases on its left, represented by solid small circles. These are precedents for their conclusion (c ), because ProblemCase1 provides more dialectical support for the conclusion. Since there are no precedents for the opposite conclusion, it is clear that ProblemCase1 should be decided positively as well.In exceptional situations a judge may decide a case without taking recourse to the stare decisis principle. A reason for this could be, for instance, that a judge wants to take into account a changing view on the law. Whatever the reasons to depart from stare decisis, if it is done the set of precedents can become contradictory, and then it can become problematic to draw conclusions in problem cases. An example is in the following figure.Settled Case2 Settled Case1Obviously SettledCase1 is now to the right of SettledCase2. As a result, the two decisions are contradictory, in the sense that the case with more support was decided negatively, while in the case with less support a positive conclusion was drawn. In other words, for whatever reason, at least one of these cases must have been decided against the principle of stare decisis.Now consider ProblemCase3, which is positioned between these two settled cases. Obviously, SettledCase1 is a precedent for the opposite conclusion (¬c ) with respect to ProblemCase3, while SettledCase2 is a precedent for the conclusion itself (c ). As a result, the precedents cannot both be followed here.This example shows that if precedents have been decided in a contradictory way and against the principle of stare decisis, then sometimes no conclusion follows from them in a problem case.4 ApplicationsThe ideas presented in the foregoing can be applied to arrive at an account of interesting reasoning patterns in case comparison. It is possible to accommodate the well-known analogising and distinguishing moves (Ashley 1990, pp. 25f.; Aleven 1997, pp. 58f.; Roth 2003, pp. 86). A number of arguments on the importance of distinctions and similarities can also be captured, viz. downplaying and emphasising (cf. Aleven 1997, pp. 62f.). As an example of the latter kind, consider the situation of the following figure. Here a settled case is cited for the conclusion (c ) that the dismissal can be voided.Problem case Suppose that the settled case is distinguished from the problem case by pointing out the significant distinction (f ) that the employee always arrived on time.Downplaying with an abstract interpretation that is a significant similarityThis way of downplaying is done by replacing a distinction with an abstract interpretation of it. Then the cases are compared in terms of this abstract interpretation, which then is a significant similarity. See the following figure.Problem case In this figure there are two comparison bases. One is indicated with a straight dashed line at level 1, a second is represented by a curved dashed line at level 2.The figure shows that if the comparison basis at level 1 is chosen, then the factor (f ) that the dismissed employee always arrived on time is a significant distinction. The distinction applies to the settled case and not to the problem case, and it supports the more abstract factor (a ) that the person always behaved like a good employee.The comparison can also be done in terms of this more abstract factor, which comes down to choosing another comparison basis. This second comparison basis differs from the first in that the original factor f is replaced with its abstract interpretation a . In the figure this second comparison basis is indicated by the curved dashed line at level 2.Relative to this second comparison basis the factor f is no significant distinction because it is not a factor. Its abstract interpretation a is a basic factor that applies to both cases. As a result, relative to the second comparison basis the factor a is a significant similarity between the cases.Emphasising with an abstract interpretation that is a significant distinctionEmphasising a distinction also involves an abstract interpretation of the distinction. The difference is, though, that here the abstract interpretation is a significantdistinction and not a significant similarity. See the following figure.Problem caseAgain the focus is on the distinction f. The original distinction f is replaced with its abstract interpretation a, and again this yields another comparison basis at level 2.This abstract interpretation a is a basic factor that applies to the settled case but not to the problem case. As a result, relative to the second comparison basis the factor a is a significant distinction between the cases.These examples show how distinctions can be downplayed or emphasised. In a similar way one can downplay or emphasise significant similarities (Roth 2003, pp. 95f.).5 Related researchIn Section 5.1 we discuss research that specifically focuses on case-based reasoning in the law. Section 5.2 addresses research on legal ontologies.5.1. Case-based reasoningThe HYPO system represents one of the most important contributions to case-based reasoning in the field of Artificial Intelligence and Law. HYPO is an implemented model of case-based reasoning that can generate realistic arguments with cases on the basis of expert background knowledge on supporting and attacking factors (p. 26). The background knowledge used for generating arguments is represented by tagging factors with a plus or a minus sign if they support a conclusion or its opposite, respectively.In HYPO it is not disputable whether or not a factor supports some conclusion or its opposite, however. Recall that in approach adopted in this paper, in contrast, it can be supported or attacked that one statement supports or attacks another (entanglement).The CATO program (Aleven 1997; Aleven 1996; Aleven and Ashley 1997) uses a model of case-based argumentation in an instructional setting, to teach students basic skills of arguing with cases.The CATO model of case-based reasoning relies on a Factor Hierarchy, a body of case-independent background knowledge about how the relevant factors in some domain relate to each other. Among other things the Factor Hierarchy is used to reason about the significance of distinctions between cases (downplaying and emphasizing). To produce such arguments CATO can infer abstract interpretations of with the help of the links encoded in its Factor Hierarchy, thereby guided by special strategic heuristics. As shown previously, such downplaying and emphasising arguments can also be accommodated in the present approach. There presently are no heuristics to guide a strategic choice among several possible ways of downplaying or emphasising, however.Another difference with the present approach is that in CATO it cannot be supported or attacked that a factor supports a conclusion or its opposite.Prakken and Sartor (1998) deal with case-based reasoning as a kind of dialectical argumentation. Cases are represented by collections of rules from which arguments can be constructed (p. 256). The conflict resolving potential of settled cases is exploited by interpreting them as sources of priority information on conflicting rules (p. 256).In Prakken and Sartor’s system the focus is on analogizing and distinguishing as ways of reasoning with cases. These two ways of reasoning are treated as a kind of premise introduction (p. 261) or theory construction (cf. Prakken 2000, pp. 51f.). They involve the introduction of new rules on the basis of rules of settled cases.This way of reasoning with cases differs from the present approach in that a suitable comparison outcome must be established before a settled case can be followed. There must be at least as much dialectical support for a conclusion in the problem case, and only then can one draw the conclusion.Prakken and Sartor want to deal with case comparison in terms of HYPO’s criterion of on pointness (p. 267). Due to problems in connection with derivable factors, however, they choose not to define comparison outcomes in terms of on pointness (p. 270). Instead they simply assume that some criterion for on pointness has already been agreed upon, as part of the premises from which the debate starts (pp. 270-271).This is in contrast with the present approach, where the outcomes of case comparison are defined in terms of the level of dialectical support for a conclusion.A final difference with the present approach is that the set of factors relevant for case comparison is not introduced explicitly to acknowledge the contingency of this set.Bench-Capon and Sartor (2001) have proposed an approach in which reasoning with cases is treated as the construction and use of theories.In their model, theories are intended to explain decided cases in terms of the values promoted by the legal system as a whole, and to help predict the outcomes of new cases. Briefly, decisions are interpreted as evidence for rule priorities, which are in turn interpreted in terms of priorities between the values upheld by the rules. These value priorities can then be used to derive new rule priorities that can help decide problem cases.Bench-Capon and Sartor’s model does not recognise explicitly that in the law it depends on a contingent choice which factors are relevant for case comparison.Hage gives an account of case-based reasoning in Reason-Based Logic (Hage 1997, Chapters IV and V; Verheij 1996, Chapters 2 and 3). Reason-Based Logic is a logical system which involves the use of rules and principles in legal reasoning, and which allows for exceptions to rules or principles, to the effect that conclusions cease to hold (Hage 1997, pp. 137-138, 141-143 and 150-151).In Hage’s reason-based account of case-based reasoning, case comparison is done in terms of the reasons for or against the disputed conclusion. In other words, Hage’s account only captures one-step arguments.Another important difference between Hage’s account and the present one is that while entanglement of factors can in principle be captured in Hage’s Reason-Based Logic, it does not play a role in his account of case comparison.Two ways of categorising approaches to case-based reasoning are illustrated next. First, one can distinguish the approaches by the method of employing cases that they focus on: the rule extraction or case comparison method. Second, one can categorise approaches by their relative emphasis on the legal conclusions that follow by comparison with settled cases, or the reasoning patterns along which they follow. An example of a categorisation along these distinctions is in the following figure.Hage’s reason-based account Positioning approaches to case-based reasoningConclusions Ashley’s HYPO Aleven’s CATOPrakken & Sartor’sdialogue gameBench-Capon & Sartor’stheories and values present approachReasoningPatternsCase Comparison RuleExtraction5.2 Cases in legal ontologiesThere exists a lively research community dealing with the topic of legal ontologies from an artificial intelligence perspective (cf., e.g., Visser & Winkels 1997, Winkels, Van Engers & Bench-Capon 2001).3 We briefly discuss work on legal ontologies and3 A useful web site for pointers to research concerning legal ontologies is the home page of Radboud Winkels (http://www.lri.jur.uva.nl/~winkels/).。