2012 Survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated by DC

The Body-Mass Index, Airflow Obstruction, Dyspnea, and Exercise Capacity Index in COPD

n engl j med 350;10march 4, 2004 The new england journal of medicine1005The Body-Mass Index, Airflow Obstruction, Dyspnea, and Exercise Capacity Index in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary DiseaseBartolome R. Celli, M.D., Claudia G. Cote, M.D., Jose M. Marin, M.D., Ciro Casanova, M.D., Maria Montes de Oca, M.D., Reina A. Mendez, M.D.,Victor Pinto Plata, M.D., and Howard J. Cabral, Ph.D.From the COPD Center at St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston (B.R.C., V .P.P.); Bay Pines Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Bay Pines,Fla. (C.G.C.); Hospital Miguel Servet, Zara-goza, Spain (J.M.M.); H ospital Nuestra Senora de La Candelaria, Tenerife, Spain (C.C.); Hospital Universitario de Caracas and Hospital Jose I. Baldo, Caracas, Vene-zuela (M.M.O., R.A.M.); and Boston Uni-versity School of Public H ealth, Boston (H.J.C.). Address reprint requests to Dr.Celli at Pulmonary and Critical Care Medi-cine, St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center, 736Cambridge St., Boston, MA 02135, or at bcelli@.N Engl J Med 2004;350:1005-12.Copyright © 2004 Massachusetts Medical Society.backgroundChronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is characterized by an incompletely re-versible limitation in airflow. A physiological variable — the forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV 1 ) — is often used to grade the severity of COPD. However, patients with COPD have systemic manifestations that are not reflected by the FEV 1 . We hypoth-esized that a multidimensional grading system that assessed the respiratory and sys-temic expressions of COPD would better categorize and predict outcome in these pa-tients.methodsWe first evaluated 207 patients and found that four factors predicted the risk of death in this cohort: the body-mass index (B), the degree of airflow obstruction (O) and dys-pnea (D), and exercise capacity (E), measured by the six-minute–walk test. We used these variables to construct the BODE index, a multidimensional 10-point scale in which higher scores indicate a higher risk of death. We then prospectively validated the index in a cohort of 625 patients, with death from any cause and from respiratory caus-es as the outcome variables.resultsThere were 25 deaths among the first 207 patients and 162 deaths (26 percent) in the validation cohort. Sixty-one percent of the deaths in the validation cohort were due to respiratory insufficiency, 14 percent to myocardial infarction, 12 percent to lung can-cer, and 13 percent to other causes. Patients with higher BODE scores were at higher risk for death; the hazard ratio for death from any cause per one-point increase in the BODE score was 1.34 (95 percent confidence interval, 1.26 to 1.42; P<0.001), and the hazard ratio for death from respiratory causes was 1.62 (95 percent confidence inter-val, 1.48 to 1.77; P<0.001). The C statistic for the ability of the BODE index to predict the risk of death was larger than that for the FEV 1 (0.74 vs. 0.65).conclusionsThe BODE index, a simple multidimensional grading system, is better than the FEV 1at predicting the risk of death from any cause and from respiratory causes among pa-tients with COPD.The new england journal of medicine1006hronic obstructiv e pulmonarydisease (COPD), a common disease char-acterized by a poorly reversible limitationin airflow,1 is predicted to be the third most fre-quent cause of death in the world by 2020.2 Therisk of death in patients with COPD is often gradedwith the use of a single physiological variable, theforced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1).1,3,4However, other risk factors, such as the presenceof hypoxemia or hypercapnia,5,6 a short distancewalked in a fixed time,7 a high degree of functionalbreathlessness,8 and a low body-mass index (theweight in kilograms divided by the square of theheight in meters),9,10 are also associated with anincreased risk of death. We hypothesized that a mul-tidimensional grading system that assessed the res-piratory, perceptive, and systemic aspects of COPDwould better categorize the illness and predict theoutcome than does the FEV1 alone. We used datafrom an initial cohort of 207 patients to identifyfour factors that predicted the risk of death: thebody-mass index (B), the degree of airflow ob-struction (O) and functional dyspnea (D), and exer-cise capacity (E) as assessed by the six-minute–walk test. We then integrated these variables into amultidimensional index — the BODE index — andvalidated the index in a second cohort of 625 pa-tients, with death from any cause and death from859 outpatients with a wide range in the severityof COPD were recruited from clinics in the UnitedStates, Spain, and Venezuela. The study was ap-proved by the human-research review board at eachsite, and all patients provided written informed con-sent. COPD was defined by a history of smokingthat exceeded 20 pack-years and a ratio of FEV1 toforced vital capacity (FVC) of less than 0.7 measured20 minutes after the administration of albuterol.1All patients were in clinically stable condition andreceiving appropriate therapy. Patients who werereceiving inhaled oxygen had to have been takinga stable dose for at least six months before studyentry. The exclusion criteria were an illness otherthan COPD that was likely to result in death withinthree years; asthma, defined as an increase in theFEV1 of more than 15 percent above the base-linevalue or of 200 ml after the administration of a bron-chodilator; an inability to take the lung-functionand six-minute–walk tests; a myocardial infarctionwithin the preceding four months; unstable angi-na; or congestive heart failure (New York Heart As-sociation class III or IV).variables selected for the bode indexWe determined the following variables in the first207 patients who were recruited between 1995 and1997: age; sex; pack-years of smoking; FVC; FEV1,measured in liters and as a percentage of the pre-dicted value according to the guidelines of theAmerican Thoracic Society11; the best of two six-minute–walk tests performed at least 30 minutesapart12; the degree of dyspnea, measured with theuse of the modified Medical Research Council(MMRC) dyspnea scale13; the body-mass index9,10;the functional residual capacity and inspiratorycapacity11; the hematocrit; and the albumin level.The validated Charlson index was used to deter-mine the degree of comorbidity. This index hasbeen shown to predict mortality.14 The differenc-es in these values between survivors and nonsur-vivors are shown in Table 1.Each of these possible explanatory variableswas independently evaluated to determine its as-sociation with one-year mortality in a stepwise for-ward logistic-regression analysis. A subgroup offour variables had the strongest association — thebody-mass index, FEV1 as a percentage of the pre-dicted value, score on the MMRC dyspnea scale,and the distance walked in six minutes (general-ized r2=0.21, P<0.001) — and these were includ-ed in the BODE index (Table 2). All these variablespredict important outcomes, are easily measured,and may change over time. We chose the post-bron-chodilator FEV1 as a percent of the predicted value,classified according to the three stages identifiedby the American Thoracic Society, because it can beused to predict health status,15 the rate of exacer-bation of COPD,16 the pharmacoeconomic costs ofthe disease,17 and the risk of death.18,19 We chosethe MMRC dyspnea scale because it predicts thelikelihood of survival among patients with COPD8and correlates well with other scales and health-status scores.20,21 We chose the six-minute–walktest because it predicts the risk of death in patientswith COPD,7 patients who have undergone lung-reduction surgery,22 patients with cardiomyopa-thy,23 and those with pulmonary hypertension.24In addition, the test has been standardized,12 theclinically significant thresholds have been deter-mined,25 and it can be used to predict resource uti-cn engl j med 350; march 4, 2004n engl j med 350;10march 4, 2004 a multidimensional grading system in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease1007lization. 26 Finally, there is an inverse relation be-tween body-mass index and survival 9,10 that is not linear but that has an inflection point, which was 21 in our cohort and in another study. 10validation of the bode indexThe BODE index was validated prospectively in two ways in a different cohort of 625 patients who were recruited between January 1997 and January 2003. First, we used the empirical model: for each threshold value of FEV 1 , distance walked in six min-utes, and score on the MMRC dyspnea scale shown in Table 2, the patients received points ranging from 0 (lowest value) to 3 (maximal value). For body-mass index the values were 0 or 1, because of the unique relation between body-mass index and survival described above. The points for each varia-ble were added, so that the BODE index ranged from 0 to 10 points, with higher scores indicating a greater risk of death. In an exploratory analysis, the various components of the BODE index were as-signed different weights, with no corresponding increase in predictive value.study protocolIn the cohort, patients were evaluated with the use of the BODE index within six weeks after enroll-ment and were seen every three to six months for at least two years or until death. The patient and family were contacted if the patient failed to return for appointments. Death from any cause and from specific respiratory causes was recorded. The cause of death was determined by the investigators at each site after reviewing the medical record and death certificate.statistical analysisData for continuous variables are presented as means ± SD. Comparison among the three coun-tries was completed with the use of one-way analy-sis of variance. The differences between survivors and nonsurvivors in pulmonary-function variables and other pertinent characteristics were established with the use of t-tests for independent samples.To evaluate the capacity of the BODE index to pre-dict the risk of death, we performed Cox propor-tional-hazards regression analyses. 27 We estimat-ed the hazard ratio, 95 percent confidence interval,and P value for the BODE score, before and after adjustment for coexisting conditions as measured by the Charlson index. We repeated these analyses using the BODE index as the predictor of interest in*FVC denotes forced vital capacity, FEV 1 forced expiratory volume in one sec-ond, and FRC functional residual capacity.†Scores on the modified Medical Research Council (MMRC) dyspnea scale can range from 0 to 4, with a score of 4 indicating that the patient is too breathless to leave the house or becomes breathless when dressing or undressing.‡The body-mass index is the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters.§Scores on the Charlson index can range from 0 to 33, with higher scores indi- cating more coexisting conditions.*The cutoff values for the assignment of points are shown for each variable. The total possible values range from 0 to 10. FEV 1 denotes forced expiratory volume in one second.†The FEV 1 categories are based on stages identified by the American Thoracic Society.‡Scores on the modified Medical Research Council (MMRC) dyspnea scale can range from 0 to 4, with a score of 4 indicating that the patient is too breathless to leave the house or becomes breathless when dressing or undressing.§The values for body-mass index were 0 or 1 because of the inflection point in the inverse relation between survival and body-mass index at a value of 21.The new england journal of medicine1008dummy-variable form, using the first quartile as thereference group. These analyses yielded estimatesof risk similar to those obtained from analyses us-ing the BODE score as a continuous variable. Thus,we focus our presentation on the predictive charac-teristics of the BODE index and present only bivari-ate results for survival according to quartiles of theBODE index in a Kaplan–Meier analysis. The statis-tical significance was evaluated with the use of thelog-rank test. We also performed bivariate analysison the stage of COPD according to the validatedstaging system of the American Thoracic Society.3In the Cox regression analysis, we assessed thereliability of the model with the body-mass index,degree of airflow obstruction and dyspnea, and ex-ercise capacity score as the predictor of the time todeath by computing bootstrap estimates using thefull sample for the hazard ratio and its 95 percentconfidence interval (according to the percentilemethod). This approach has the advantage of notrequiring that the data be split into subgroups andis more precise than alternative methods, such ascross-validation.28Finally, in order to determine how much moreprecise the BODE index is than the FEV1 alone, wecomputed the C statistics29 for a model containingFEV1 or the BODE score as the sole independentvariable. We compared the survival times and esti-mated the probabilities of death up to 52 months.In these analyses, the C statistic is a mathematicalfunction of the sensitivity and specificity of theBODE index in classifying patients by means of theCox model as either dying or surviving. The nullvalue for the C statistic is 0.5, with a maximum of29patients (Tables 3 and 4) with all degrees of severityof COPD. The FEV1 was slightly lower among pa-tients in the United States than among those in Ven-ezuela or Spain. The U.S. patients also had morefunctional impairment, more severe dyspnea, andmore coexisting conditions. The 27 patients (4 per-cent) lost to follow-up were evenly distributed ac-cording to the severity of COPD and did not differsignificantly from the rest of the cohort with respectto any measured characteristic. There were 162deaths (26 percent) over a median follow-up of 28months (range, 4 to 68). The majority of patients(61 percent) died of respiratory insufficiency, 14percent died of myocardial infarction, 12 percentof lung cancer, and the rest of miscellaneouscauses. The BODE score was lower among survi-vors than among those who died from any cause(3.7±2.2 vs. 5.9±2.6, P<0.005). The score was alsolower among survivors than among those whodied of respiratory causes, and the difference be-tween the scores was larger (3.6±2.2 vs. 6.7±2.3,P<0.001).Table 5 shows the BODE index as a predictor ofdeath from any cause after correction for coexistingconditions. There were significantly more deathsin the United States (32 percent) than in Spain (15percent) or Venezuela (13 percent) (P<0.001). How-ever, when the analysis was done separately foreach country, the predictive power of the BODE in-dex was similar; therefore, the data are presentedtogether. Table 5 shows that the BODE index wasalso a predictor of death from respiratory causesafter correction for coexisting conditions (hazardratio, 1.63; 95 percent confidence interval, 1.48 to1.80; P<0.001). The Kaplan–Meier analysis of sur-*Because of rounding, percentages do not total 100. Thethree stages of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease(COPD) were defined by the American Thoracic Society.FEV1 denotes forced expiratory volume in one second.†Higher scores on the body-mass index, degree of airflowobstruction and dyspnea, and exercise capacity (BODE)index indicate a greater risk of death. Quartile 1 was de-fined by a score of 0 to 2, quartile 2 by a score of 3 to 4,quartile 3 by a score of 5 to 6, and quartile 4 by a scoreof 7 to 10.n engl j med 350; march 4, 2004n engl j med 350;10march 4, 2004 a multidimensional grading system in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease1009vival (Fig. 1A) shows that each quartile increase in the BODE score was associated with increased mor-tality (P<0.001). Thus, the highest quartile (a BODE score of 7 to 10) was associated with a mortality rate of 80 percent at 52 months. These same data are shown in Figure 1B in relation to the severity of COPD according to the staging system of the Amer-ican Thoracic Society. The C statistic for the ability of the BODE index to predict the risk of death was 0.74, as compared with a value of 0.65 with the use of FEV 1 alone (expressed as a percentage of the pre-dicted value). The computation of 2000 bootstrap samples for these data and estimation of the haz-ard ratios for death indicated that for each one-point increment in the BODE score the hazard ratio for death from any cause was 1.34 (95 percent confi-dence interval, 1.26 to 1.42) and the hazard ratio for death from a respiratory cause was 1.62 (95 per-the BODE index — and validated its use by show-ing that it is a better predictor of the risk of death from any cause and from respiratory causes than is the FEV 1 alone. We believe that the BODE index is useful because it includes one domain that quan-tifies the degree of pulmonary impairment (FEV 1 ),one that captures the patient’s perception of symp-toms (the MMRC dyspnea scale), and two indepen-dent domains (the distance walked in six minutes and the body-mass index) that express the systemic consequences of COPD. The FEV 1 is essential for the diagnosis and quantification of the respirato-ry impairment resulting from COPD. 1,3,4 In addi-tion, the rate of decline in FEV 1 is a good marker of disease progression and mortality. 18,19 Howev-er, the FEV 1 does not adequately reflect all the sys-temic manifestations of the disease. For example,the FEV 1 correlates weakly with the degree of dys-pnea, 20 and the change in FEV 1 does not reflect the rate of decline in patients’ health. 30 More impor-tant, prospective observational studies of patients with COPD have found that the degree of dyspnea 8 and health-status scores 31 are more accurate pre-dictors of the risk of death than is the FEV 1 . Thus,although the FEV 1 is important to obtain and essen-tial in the staging of disease in any patient with COPD, other variables provide useful information that can improve the comprehensibility of the eval-uation of patients with COPD. Each variable should*Plus–minus values are means ±SD.†Analysis of variance was used to calculate the P values.‡Scores on the modified Medical Research Council (MMRC) dyspnea scale can range from 0 to 4, with a score of 4 indicating that the patient is too breathless to leave the house or becomes breathless when dressing or undressing.§Scores on the Charlson index can range from 0 to 33, with higher scores indi-cating more coexisting conditions.¶Scores on the body-mass index, degree of airflow obstruction and dyspnea, and exercise capacity (BODE) index can range from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating a greater risk of death.*The Cox proportional-hazards models for death from any cause include 162 deaths. The Cox proportional-hazards models for death from specific respira-tory causes include 96 deaths. Model I includes the body-mass index, degree of airflow obstruction and dyspnea, and exercise capacity (BODE) index alone. The hazard ratio is for each one-point increase in the BODE score. Model II includes coexisting conditions as expressed by each one-point increase in the Charlson index. CI denotes confidence interval.The new england journal of medicine1010correlate independently with the prognosis ofCOPD, should be easily measurable, and shouldserve as a surrogate for other potentially importantvariables.In the BODE index, we included two descriptorsof systemic involvement in COPD: the body-massindex and the distance walked in six minutes. Bothare simply obtained and independently predict therisk of death.7,9,10 It is likely that they share somecommon underlying physiological determinants,but the distance walked in six minutes contains adegree of sensitivity not provided by the body-massindex. The six-minute–walk test is simple to per-form and has been standardized.12 Its use as a clin-ical tool has gained acceptance, since it is a goodpredictor of the risk of death among patients withother chronic diseases, including congestive heartfailure23 and pulmonary hypertension.24 Indeed, thedistance walked in six minutes has been acceptedas a good outcome measure after interventions suchas pulmonary rehabilitation.32 The body-mass in-dex was also an independent predictor of the riskof death and was therefore included in the BODEindex. We evaluated the independent prognosticpower of body-mass index in our cohort using dif-ferent thresholds and found that values below 21were associated with an increased risk of death, anobservation similar to that reported by Landbo andcoworkers in a large population study.10The Global Initiative for Chronic ObstructiveLung Disease and the American Thoracic Societyrecommend that a patient’s perception of dyspneabe included in any new staging system for COPD.1,3Dyspnea represents the most disabling symptomof COPD; the degree of dyspnea provides informa-tion regarding the patient’s perception of illnessand can be measured. The MMRC dyspnea scale issimple to administer and correlates with other dys-pnea scales20 and with scores of health status.21Furthermore, in a large cohort of prospectively fol-lowed patients with COPD, which used the thresh-old values included in the BODE index, the scoreon the MMRC dyspnea scale was a better predictorof the risk of death than was the FEV1.8The BODE index combines the four variables bymeans of a simple scale. We also explored whetherweighting the variables included in the index im-proved the predictive power of the BODE index. In-terestingly, it failed to do so, most likely becauseeach variable included has already proved to be agood predictor of the outcome of COPD.Our study had some limitations. First, relative-ly few women were recruited, even though enroll-ment was independent of sex. It probably reflectsthe problem of the underdiagnosis of COPD inwomen. Second, there were differences among thethree countries. For example, patients in the UnitedStates had a higher mortality rate, more severe dys-pnea, more functional limitations, and more co-n engl j med 350; march 4, 2004n engl j med 350; march 4, 2004a multidimensional grading system in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease1011existing conditions than patients in Venezuela or Spain, even though the severity of airflow obstruc-tion was relatively similar among the patients as a whole. The reasons for these differences are un-known, because there have been no systematic com-parisons of the regional manifestations of COPD.In all three countries, the BODE index was the best predictor of survival, an observation that renders our findings widely applicable.Three studies have reported the effects of the grouping of variables to express the various do-mains affected by COPD.33-35 These studies did not include variables now known to be important pre-dictors of outcome, such as the body-mass index.However, as we found in our study, they showedthat the FEV 1, the degree of dyspnea, and exercise performance provide independent information regarding the degree of compromise in patients with COPD.Besides its excellent predictive power with re-gard to outcome, the BODE index is simple to cal-culate and requires no special equipment. This makes it a practical tool of potentially widespread applicability. Although the BODE index is a predic-tor of the risk of death, we do not know whether it will be a useful indicator of the outcome in clinical trials, the degree of utilization of health care re-sources, or the clinical response to therapy.We are indebted to Dr. Gordon L. Snider, whose guidance, com-ments, and criticisms were fundamental to the final manuscript.1.Pauwels RA, Buist AS, Calverley PM,Jenkins CR, Hurd SS. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease:NHLBI/WHO Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) Work-shop summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;163:1256-76.2.Murray CJL, Lopez AD. Mortality by cause for eight regions of the world: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 1997;349:1269-76.3.Definitions, epidemiology, pathophys-iology, diagnosis, and staging. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995;152:Suppl:S78-S83.4.Siafakas NM, Vermeire P, Pride NB, et al. Optimal assessment and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Eur Respir J 1995;8:1398-420.5.Nocturnal Oxygen Therapy Trial Group.Continuous or nocturnal oxygen therapy in hypoxemic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical trial. Ann Intern Med 1980;93:391-8.6.Intermittent positive pressure breathing therapy of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical trial. Ann Intern Med 1983;99:612-20.7.Gerardi DA, Lovett L, Benoit-Connors ML, Reardon JZ, ZuWallack RL. Variables re-lated to increased mortality following out-patient pulmonary rehabilitation. Eur Res-pir J 1996;9:431-5.8.Nishimura K, Izumi T, Tsukino M, Oga T. Dyspnea is a better predictor of 5-year sur-vival than airway obstruction in patients with COPD. Chest 2002;121:1434-40.9.Schols AM, Slangen J, Volovics L, Wout-ers EF. Weight loss is a reversible factor in the prognosis of chronic obstructive pulmo-nary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;157:1791-7.ndbo C, Prescott E, Lange P, Vestbo J,Almdal TP. Prognostic value of nutritional status in chronic obstructive pulmonary dis-ease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;160:1856-61.11.American Thoracic Society Statement.Lung function testing: selection of reference values and interpretative strategies. Am Rev Respir Dis 1991;144:1202-18.12.ATS Committee on Proficiency Stan-dards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Lab-oratories. ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:111-7.13.Mahler D, Wells C. Evaluation of clinical methods for rating dyspnea. Chest 1988;93:580-6.14.Charlson M, Szatrowski T, Peterson J,Gold J. Validation of a combined comor-bidity index. J Clin Epidemiol 1994;47:1245-51.15.Ferrer M, Alonso J, Morera J, et al. Chron-ic obstructive pulmonary disease stage and health-related quality of life. Ann Intern Med 1997;127:1072-9.16.Dewan NA, Rafique S, Kanwar B, et al.Acute exacerbation of COPD: factors associ-ated with poor treatment outcome. Chest 2000;117:662-71.17.Friedman M, Serby CW , Menjoge SS,Wilson JD, Hilleman DE, Witek TJ Jr. Phar-macoeconomic evaluation of a combination of ipratropium plus albuterol compared with ipratropium alone and albuterol alone in COPD. Chest 1999;115:635-41.18.Anthonisen NR, Wright EC, Hodgkin JE. Prognosis in chronic obstructive pulmo-nary disease. Am Rev Respir Dis 1986;133:14-20.19.Burrows B. Predictors of loss of lung function and mortality in obstructive lung diseases. Eur Respir Rev 1991;1:340-5.20.Mahler DA, Weinberg DH, Wells CK ,Feinstein AR. The measurement of dyspnea:contents, interobserver agreement, and phys-iologic correlates of two new clinical index-es. Chest 1984;85:751-8.21.Hajiro T, Nishimura K, Tsukino M, Ike-da A, Koyama H, Izumi T. Comparison of discriminative properties among disease-specific questionnaires for measuring health-related quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;157:785-90.22.Szekely LA, Oelberg DA, Wright C, et al.Preoperative predictors of operative mor-bidity and mortality in COPD patients under-going bilateral lung volume reduction sur-gery. Chest 1997;111:550-8.23.Shah M, Hasselblad V , Gheorgiadis M,et al. Prognostic usefulness of the six-min-ute walk in patients with advanced conges-tive heart failure secondary to ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Am J Car-diol 2001;88:987-93.24.Miyamoto S, Nagaya N, Satoh T, et al.Clinical correlates and prognostic signifi-cance of six-minute walk test in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension: compari-son with cardiopulmonary exercise testing.Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;161:487-92.25.Redelmeier DA, Bayoumi AM, Gold-stein RS, Guyatt GH. Interpreting small dif-ferences in functional status: the Six Minute Walk test in chronic lung disease patients.Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997;155:1278-82.26.Decramer M, Gosselink R, Troosters T,Verschueren M, Evers G. Muscle weakness is related to utilization of health care resourc-es in COPD patients. Eur Respir J 1997;10:417-23.27.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. J R Stat Soc [B] 1972;34:187-220.28.Harrell FE Jr, Lee KL, Mark DB. Multi-variate prognostic models: issues in devel-oping models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing er-rors. Stat Med 1996;15:361-87.29.Nam B-H, D’Agostino R. Discrimina-tion index, the area under the ROC curve. In:Huber-Carol C, Balakrishnan N, Nikulin MS,Mesbah M, eds. Goodness-of-fit tests and。

非小细胞肺癌,抗血管治疗系列研究汇总

非小细胞肺癌,抗血管治疗系列研究汇总非小细胞肺癌药物治疗主要有化疗、靶向、免疫治疗等,给病人带来了很大的生存获益。

其中抗血管治疗也是一种重要的治疗方式,联合其他治疗具有协同作用,可以明显改善生存。

小编整理了目前临床应用的抗血管生成药物的系列研究,有助于我们更深入认识该类药物。

全文概要贝伐珠单抗贝伐单抗+化疗一线治疗1. ECOG4599研究:联合组明显延长生存时间2. AVAil研究:联合组PFS延长3. BEYOND研究(中国):联合组显著延长生存时间维持治疗4. ECOG5508、COMPASS、AVAPERL、POINT BREAK、PRONOUNCE研究:主要对比培美曲塞 vs. 贝伐单抗 vs. 联合组,联合组PFS延长,各组间OS无差异不良反应5. 主要禁忌症:鳞癌、咯血(>2级)史贝伐单抗+EGFR-TKI6. JO25567、NEJ026研究:厄洛替尼vs. 厄洛替尼+贝伐组,PFS延长,OS无差异7. CTONG1509研究(中国):联合组PFS显著延长,21L858R、脑转移获益更显著贝伐单抗+免疫治疗8. IMpower150研究:ABCP vs. BCP,生存获益9. IMpower130研究:ACP vs. CP,生存获益10. IMpower130 vs. IMpower150,三药基础上加上贝伐单抗的ABCP方案对EGFR突变和伴肝转移的患者获益更高特殊人群11. 老年、脑转移患者可以使用贝伐单抗雷莫芦单抗雷莫芦单抗+化疗一线治疗12. 两项研究:联合治疗效果不理想二线治疗13. REVEL研究:雷莫芦单抗+多西他赛 vs.多西他赛,生存获益雷莫芦单抗+EGFR-TKI14. RELAY研究:雷莫芦单抗+厄洛替尼 vs.厄洛替尼,PFS延长尼达尼布15. LUME-Lung1研究:二线,尼达尼布+多西他赛 vs. 多西他赛,PFS延长安罗替尼16. ALTER0302、ALTER0303研究:三线,安罗替尼vs. 安慰剂,生存获益阿帕替尼17. 一项Ⅱ期研究:三线,阿帕替尼 vs. 安慰剂,PFS延长18. ACTIVE研究:一线,阿帕替尼+吉非替尼 vs. 吉非替尼,PFS 延长恩度19. 一项多中心研究:一线,恩度+NP vs. NP,改善治疗结局抗血管生成药物获批情况贝伐珠单抗贝伐单抗+化疗一线治疗ECOG4599研究[1]:一项Ⅲ期随机对照临床研究,共纳入878例复发性或晚期非鳞NSCLC患者,数据显示,卡铂+紫杉醇联合贝伐珠单抗一线治疗比较单纯化疗方案可明显延长患者生存时间(中位OS 12.3个月vs 10.3个月,HR=0.79,P=0.003;中位PFS 6.2个月vs 4.5个月,HR=0.66,P<0.001),提高客观缓解率(objective response rate,ORR)(35% vs 15%, P<0.001)。

医学英语写作与翻译

第三部分医学英语的写作任务一标题的写作(Title)标题的结构1. 名词+介词Blindness(视觉缺失)after Treatment for Malignant Hypertension 2. 名词+分词Unilateral Neurogenic Pruritus Following Stroke中风后单侧神经性瘙痒3. 名词+不定式Suggestion to Abolish Icterus Index Determination(黄疸指数测定)where Quantitative Bilirubin Assay(胆红素定量)is Available建议能做胆红素定量的化验室不再做黄疸指数测定4. 名词+同位语Gentamicine, a Selelctive Agent for the isolation of Betahemolytic Streptocc ociβ-溶血性链球菌庆大霉素是分离β-溶血性链球菌的选择性药物5. 名词+从句Evidence that the V-sis Gene Product Transforms by Interaction with the Receptor for Platelet-derived Growth Factor血小板源性生长因子.V-sis 基因产物由血小板生成因子受体相互作用而转化的依据6. 动名词短语Preventing Stroke in patients with Atrial Fibrillation心房纤维性颤动心旁纤颤患者中风预防Detecting Acute Myocardial Infarction(急性心肌梗死)byRadio-immunoassay for Creative Kinase(酐激酶)用放射免疫法测定酐激酶诊断急性心肌梗死7. 介词短语On Controlling Rectal Cancer8. 陈述句Dietary Cholesterol is Co-carcinogenic协同致癌因素for Human Colon Cancer9. 疑问句Home or Hospital BirthsIs Treatment of Borderline Hypertension Good or Bad?注意副标题的作用1.数目:Endoluminal Stent-graft 带支架腔内搭桥for Aortic Aneurysms动脉瘤: A report of 6 cases带支架腔内搭桥治疗动脉瘤的六例报告2.重点:Aorto-arteritis 大动脉炎Chest X-ray Appearance and Its Clinical Significance大动脉炎胸部X线表现及临床意义3.方法:Gallstone Ileus(胆结石梗阻): A Retrospective Study 4.作用:Carcinoembryonic Antigen in Breast-cancer Tissue: A useful prognostic indictor乳腺癌组织中癌胚抗原——一种有用的预后指示5.疑问:Unresolved—Do drinkers have less coronary heart disease? 6.连载顺序:Physical and Chemical Studies of Human Blood Serum: II. A study of miscellaneous Disease conditions人类血清的理论研究:II. 多种病例的研究7.时间:A Collaborative 综合Study of Burn Nursing in China: 1995-1999常见标题句式举例1. 讨论型:Discussion of/ on; An approach to; A probe into; Investigation of; Evaluation of / on汉语中的“初步体会”、“试论”、“浅析”之类的谦辞可以不译。

治疗癌症的英语叙事作文

治疗癌症的英语叙事作文In the shadow of despair, a glimmer of hope pierced through the darkness. Cancer, a word that once sent shivers down the spine of humanity, is now being challenged by the relentless pursuit of medical science. The narrative of cancer treatment is not just a tale of survival, but a testament to the indomitable spirit of human innovation.The journey begins with the initial diagnosis, a moment that can be as devastating as it is life-altering. Yet, it is also the starting point of a courageous battle against an invisible enemy. The first line of defense is often surgery, a precise and calculated operation that seeks to excise the malignancy from the body. It is a brutal yet necessary act, a surgical strike against the disease.Chemotherapy follows, a chemical onslaught that targets the cancer cells, leaving them no place to hide. It is a double-edged sword, as it can also affect healthy cells, but the potential for remission is worth the risk. The patient's resilience is tested, as they endure the side effects with stoic determination.Radiation therapy, another formidable weapon in the arsenal, uses high-energy rays to destroy cancer cells at their very core. It is a targeted attack, sparing the surrounding healthy tissue while delivering a lethal blow to the tumor.The advent of immunotherapy has revolutionized the field, harnessing the body's own immune system to recognize andattack cancer cells. It is a sophisticated strategy, a danceof biological warfare where the immune cells are trained tobe the ultimate defenders.Precision medicine has taken the narrative to new heights, with treatments tailored to the genetic makeup of the tumor. This personalized approach is a beacon of hope, as itpromises to reduce the collateral damage of treatment and increase the chances of success.Throughout this narrative, the patient's story is one of courage and tenacity. The support of family and friends, the unwavering dedication of healthcare professionals, and the relentless drive of researchers all contribute to acollective narrative of hope and progress.As we stand on the precipice of new discoveries, the narrative of cancer treatment continues to evolve. It is a story of scientific triumph, a narrative that is beingwritten with every breakthrough, every survivor's tale, and every life saved. The fight against cancer is far from over, but with each passing day, the light of hope grows brighter, illuminating the path to a future where cancer is no longer a death sentence, but a challenge overcome.。

57例急性重度敌敌畏中毒患者的临床特征和救治体会

• 86 •屮丨丨…丨1两與结合急救杂志202丨年2J j第28#第丨期(:h i n J T(:M W M(:H l(:a r e,K e b m a r y2021,V u l.28,N o.l•论著•57例急性重度敌敌畏中毒患者的临床特征和救治体会石聪辉吴贤聪郑志鹏郁毅刚沈清音庄佳毅刘惠娜ffl门大学附属东南医院暨联勤保障部队第儿〇儿医院急诊科,福建漳州363000通信作者:刘惠娜,Email : 49308404l@q q.r_【摘要】目的总结急性重度敌敌畏中毒的临床特征和救治体会方法回顾性分析2014年7月至2019年12月厦门大学附属东南医院暨联勤保障部队第九〇九医院收治的57例急性重度敌敌畏中毒患者的临床资料,其中男性23例、女性34例,年龄38( 18〜80)岁,均为【丨服中毒在重症监护下,给予基础救治措施,包括清除毒物、特效解毒剂、血液净化、呼吸支持、循环支持等;针对顽固性低血压和严重心律失常在积极给予容H:复苏、纠正酸中毒、稳定内环境的同时,增加保护心肌药、血管活性药和抗心律失常药的使用,必要时安装临时起搏器观察患者心脏损害发生情况、转归和预后,分析影响患者预后的相关因素采用多因素Lngistir回归分析影响患者预后的独立危险因素结果本组73.7%(42/57)的患者合并不同程度心脏损害,表现为心肌酶谱不同程度升高42例(100.0% )、心电图改变39例(92.9% )、心律失常25例(59.5% )、低血压14例(33.3%)、高血压2例(4.8%)。

本组患者重症监护病房(ICU)往院时间2〜10 d,平均(5.6±1.7)d ;总住院时间2〜丨4 (丨,平均(9.5±2.4)(丨本组患者治愈45例,好转5例,死亡7例(丨2.3%),其中4例死于心搏骤停或严重室性心律失常,2例死于多器官功能衰竭,1例死于中枢性呼吸循环功能衰竭单因素分析M示,死亡患者入院时格拉斯哥昏迷评分(GCS)较存活者低(分:3.4±0.6比4.3 ±丨.丨,P=0.039 ),严重心律失常发生率较存活者高〔57.1% (4/7)比20.0% ( 10/50 ),P=0.033〕安装临时起搏器的严重心律失常患者存活率M著高于未安装临时起搏器者〔20.0%(10/50)比0(0/7),户<0.01〕:存活和死亡患者年龄比较差异无统计学意义(岁:36.8±10.4比39.5 ± 11.2, /^0.526): Logistic回归多因素分析显示,人院时GCS评分彡6分〔优势比()=2.4丨7, 95%可信区间(95%C/)为1.853 〜4.692, P=0.028〕、伴严重心律失常(0/?=1.438, 95%C/为1.072 〜3.739, P=0.031)是急性重度敌敌畏中毒患者死亡的独立危险因素,安装临时起搏器是患者死亡的独立保护因素(〇/?=0.896, 为0.657〜0.%4, P=0.015 )结论心脏损害在急性重度敌敌畏中毒中常见,继发严重心律失常与患者死广:相关在使用保护心肌药和血管活性药的同时,合理选择抗心律失常药,必要时安装临时起搏器能稳定血压、保证循环灌注,提高救治成功率【关键词】敌敌畏;急性有机磷农药中毒;心脏损害;心律失常;临时起搏器基金项目:军队后勤科研重大项!〗(BLB18川06);第九〇九医院院级科研项目(20YJ001 )DOI :10.3969/j.issn. 1008-9691.2021.01.021Clinical characteristics and rescue therapeutic experience of 57 patients with acute severe dichlorvospoisoning Shi Conghui. Wu Xiancong. Zheng Zhipeng, Yu Yigang, Shen (Jingvin, Zhuang Jiayi, Liu HuiiuiDepartment of Emergency, the Affiliated Dongnan Hospital of Xiamen University, the PLA's 909th Hospital of the JointUygistics Team, Zhangzhou 363000, Fujian. ChinaCorresponding author: Liu Huina, Email:****************【Abstract】Objective To summarize the clinical characterislirs and experiences in rescue Irealmenl inpatienl.s with acute severe dichlorvos poisoning. Methods The clinical data of 57 patients with acute severedic hlorvos poisoning admitted to the department of emergency of Affiliated Hospital of Xiamen University from July 2014to December 2019 were retrospectively analyzed, including 23 males and 34 females aged 38 (18-80) years old. andall t)f them took the dichlorvos orally. I ncler severe rase monitoring, the basic rescue and treatment measures inclucledtoxic rleaning, using specific antidotes, blood purification, respiraloi-y support, c irrulalorv support, etc. For obstinatehypotensifm an(l severe an'hythniia, “le patients were given volume resuscitation, roirertinginternal environment, adding dmg for pmlerling:myorardia, vasoartive dmgs and anti-aiThvthmir dmgs, and implantingtemporary pacemakers if neressaiy. Tlie orriinence of cardiar damage, (ujt(.(mie iwl prognosis and “le i•士afferting the patients’prognosis were observed. The multivariate regiession analysis was used to analyze iheindependent risk factors of prognosis. Results In this group of palients, there were 73.7% (42/57) of them associatedwith different degrees of cardiac damage, inrluding 42 rases (100.0%) of myorardial enzymes inc-reasing, 39 rases(92.9%) with abnormal electrorardiogram, 25 cases (59.5%) with arrhythmia, 14 cases (33.3%) with hypotension, and2 rases (4.8%) with hypertension. Tlie patients stayed in intensive rare unit (ICU) for 2-10 days, with an average of(5.6 ± 1.7) days and their total length of hospital stay was 2-14 days, with an average of (9.5 ±2.4) days. The 45 raseswere (uired. 5 rases were improved an(l 7 rases (12.3%) died; among the (lead one.、 4 rases die(l ofsevere ventricular anhythmia, 2 rases of multiple organ failure and 1rase of central respiratory andUnivariate analysis sho\\r erl that the Glasgow Coma Scale (G(]S) srore at aflmission of patients in death group was lowerthan that in survivors (3.4 ±0.6 vs. 4.3 ± 1.1. P = 0.039) and the incidenre of severe aiThvthmia of death group washigher than that of survivors [57.1% (4/7) vs. 20.0% (10/50), P = 0.033J. For patients with severe arrhythmia, the survival中国中西医结合急救杂志202丨年2月第28卷第丨期C h i n J T C M W M C r i t C a r e, F V h m a r y2021,V〇1.28, N o.l• 87 •rate of patients with temporary pacemaker was signifiranlly higher than lhat of patients without temporary pac emaker[20.0% (10/50) vs. 0 (0/7), P < 0.01]. There was no significant difference in age l)etween survival and death groups (age:36.8 士K).4 vs. 39.5 ± 1 1.2, P = 0.526). 1乂)gistir regression multivmiate analysis sh(mefHhat (;CS s<we < 6 |o<l(ls(OR) =2.417, 95% confirlenre intenal (95%C f)was 1.853-4.692, P = 0.028] and comhination with severe arrhythmia(OR = 1.438. 95%67 was 1.072-3.739, P = 0.031) were independent risk factors for death of patients with anile severerlirhlorvos poisoning, and temporaiT pacemaker installalinn was an independent prolective factor for death (OR - 0.896.95c/cC/was 0.657—0.964, P= 0.015). Conclusions Cardiac damage is commonly seen in acute severe (lir hlorvr)s poisoning, and the secondary severe arrhythmia is related lo the patients' dealh. A l ihe same time of using vasoactivedrugs, rational selert of anliarrhythmic drugs romhined with installation of temporary pacemaker if neressar\r canstabilize hloocl pressure, ensure rirrulatory peifusion and improve the surcessful rale of rescue and trealmenl.【Key words】l)i(..hlorvos: Acute organophosphoms pesticide poisoning; Cardiac damage; Arrhythmia; Temporar>, pacemakerFund program:Major Mililar)- Logistics Research Project (BLB18J006); Hospital Level Scitifir Research Projerlof the 909th Hospital (20YJ001)1)01: 10.3969/j.issn. 1008-9691.2021.01.021急性敌敌畏中毒可引发一系列毒费碱样、烟碱 样和屮枢神经系统症状,严重者出现多器官损害,表 现为以神经系统损害为主的全身性疾病1口服敌敌畏达到较大M则可导致重度中毒,出现肺水肿、昏迷、呼吸衰竭(呼衰)和脑水肿等w临床上,大 多数急性重度敌敌畏中毒患者都继发了不同程度的 心脏损害,且部分患者在救治过程中死于严重心律 失常、顽固性低血压和(或)心搏骤停。

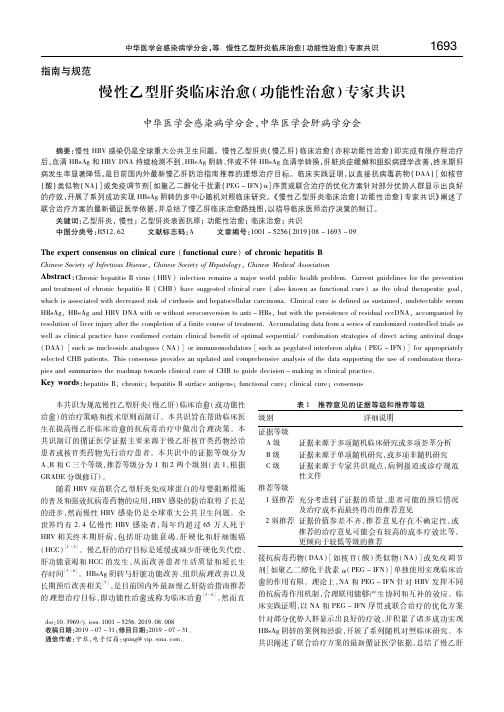

慢性乙型肝炎临床治愈(功能性治愈)专家共识 中华医学会感染病学分会

天然免疫和适应性免疫应答,在清除病毒、控制疾病进程中发 效并尽可能实现临床治愈是临床亟待解决的热点和难点问题。

挥重要作用。急性自限性感染是理想的HBV 感染的自然转 干扰素通过增强免疫细胞功能和促进细胞因子的表达、诱

归,一般无需抗病毒治疗,患者多在感染后半年内发生HBsAg 导干扰素刺激基因(ISGs)的产生并经干扰素信号通路编码多

: doi 10. 3969 / j. issn. 1001 - 5256. 2019. 08. 008

收稿日期: ;修回日期: 。 2019 - 07 - 31

2019 - 07 - 31

通信作者:宁琴,电子信箱: 。 qning@ vip. sina. com

Байду номын сангаас

针对部分优势人群显示出良好的疗效,并积累了诸多成功实现 HBsAg 阴转的案例和经验,开展了系列随机对照临床研究。本 共识阐述了联合治疗方案的最新循证医学依据,总结了慢乙肝

后,血清 HBsAg 和 HBV DNA 持续检测不到、HBeAg 阴转、伴或不伴 HBsAg 血清学转换,肝脏炎症缓解和组织病理学改善,终末期肝 病发生率显著降低,是目前国内外最新慢乙肝防治指南推荐的理想治疗目标。 临床实践证明,以直接抗病毒药物( DAA) [ 如核苷 ( 酸) 类似物( NA) ] 或免疫调节剂[ 如聚乙二醇化干扰素( PEG - IFN) α] 序贯或联合治疗的优化方案针对部分优势人群显示出良好 的疗效,开展了系列成功实现 HBsAg 阴转的多中心随机对照临床研究。 《 慢性乙型肝炎临床治愈( 功能性治愈) 专家共识》 阐述了 联合治疗方案的最新循证医学依据,并总结了慢乙肝临床治愈路线图,以指导临床医师治疗决策的制订。

1 强推荐及充治分疗考成虑本到而了最证终据得的出质的量推、患荐者意可见能的预后情况

关于参考文献

加速康复外科杂志 2020年11月 第3卷 第4期 Vol. 3 No. 4, November, 2020·174·to early and late phase intrahepatic recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatectomy[J]. J Hepatol, 2003, 38(2):200-207. [6] Squires MH, Hanish SI, Fisher SB, et al. Transplant versus resectionfor the management of hepatocellular carcinoma meeting Milan Criteria in the MELD exception era at a single institution in a UNOS region with short wait times[J]. J Surg Oncol, 2014, 109(6):533-541. [7] 徐骁, 杨家印, 钟林, 等. 肝癌肝移植“杭州标准”的多中心应用研究-1163例报道[J]. 中华器官移植杂志, 2013, 34(9):524-527.[8] 樊嘉, 周俭, 徐泱, 等. 肝癌肝移植适应证的选择: 上海复旦标准[J]. 中华医学杂志, 2006, 86(18):1227-1231.[9] Majno P, Lencioni R, Mornex F, et al. Is the treatment of hepatocellularcarcinoma on the waiting list necessary?[J]. Liver Transpl, 2011, 17(S2):S98-S108.[10] Huang M, Lin Q, Wang H, et al. Survival benefit of chemoembolizationplus Iodine125 seed implantation in unresectable hepatitis B-related hepatocellular carcinoma with PVTT: a retrospective matched cohort study[J]. Eur Radiol, 2016, 26(10):3428-3436.[11] Zhang L, Hu B, li W, et al. 125I Irradiation stent for hepatocellularcarcinoma with main portal vein tumor thrombosis: a systematic review[J]. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol1,2020,43(2):196-203.[12] Luo JJ, Zhang ZH, Liu QX, et al. Endovascular brachytherapycombined with stent placement and TACE for treatment of HCC with main portal vein tumor thrombus[J]. Hepatol Int, 2016, 10(1):185-195.[13] Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-linetreatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial[J]. Lancet, 2018, 391(10126): 1163-1173.[14] Kelley RK, Verslype C, Cohn A L, et al. Cabozantinib in hepatocellularcarcinoma: results of a phase 2 placebo-controlled randomized discontinuation study[J]. Ann Oncol, 2017, 28(3):528-534.[15] Kudo M, Ueshima K, Ikeda M, et al. Randomised, multicentreprospective trial of transarterial chemoembolisation (TACE) plus sorafenib as compared with TACE alone in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: TACTICS trial[J]. Gut, 2019, 69(8):1492-1501.[16] EL-Khoueiry AB, Sangro B, Yau T, et al. Nivolumab in patients withadvanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): an open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial[J].Lancet, 2017, 389(10088):2492-2502.[17] Zhu AX, Finn RS, Edeline J, et al. Pembrolizumab in patients withadvanced hepatocellular carcinoma previously treated with sorafenib (KEYNOTE- 224): a non- randomised, open-label phase 2 trial[J].Lancet Oncol, 2018, 19(7): 940-952.[18] Llovet JM, Shepard KV , Finn RS, et al. A phase Ib trial of lenvatinib(LEN) plus pembrolizumab (PEMBRO) in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC): Updated results[J]. Ann Oncol, 2019, 30:v286- v287.[19] Llovet JM, Kudo M, Cheng AL, et al. Lenvatinib (len) plus pembrolizumab(pembro) for the first-line treatment of patients (pts) with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): Phase 3 LEAP-002 study[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2019, 37(15_suppl):TPS4152-TPS4152.[20] Finn RS, Ducreux M, Qin S, et al. IMbrave150: a randomized phaseIII study of 1L atezolizumab plus bevacizumab vs sorafenib in locally advanced or metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2018, 36(15_suppl):TPS4141-TPS4141.(收稿时间:2020-06-15)关于参考文献请按GB/T 7717-2015《信息与文献 参考文献著录规则》,采用顺序编码制著录,依照文献在文中出现的先后顺序用阿拉伯数字加方括号标出。

《临床肝胆病杂志》推荐使用的规范医学名词术语

临床肝胆病杂志第40卷第3期2024年3月J Clin Hepatol, Vol.40 No.3, Mar.2024[3]XIA SL, LIU ZM, CAI JR, et al. Liver fibrosis therapy based on biomi⁃metic nanoparticles which deplete activated hepatic stellate cells[J]. J Control Release, 2023, 355: 54-67. DOI: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2023.01.052.[4]LIU YW, DONG YT, WU XJ, et al. The assessment of mesenchymalstem cells therapy in acute on chronic liver failure and chronic liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized con⁃trolled clinical trials[J]. Stem Cell Res Ther, 2022, 13(1): 204. DOI:10.1186/s13287-022-02882-4.[5]ZHANG ZL, SHANG J, YANG QY, et al. Exosomes derived from hu⁃man adipose mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate hepatic fibrosis by inhibiting PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway and remodeling choline me⁃tabolism[J]. J Nanobiotechnology, 2023, 21(1): 29. DOI: 10.1186/ s12951-023-01788-4.[6]ZHAO T, SU ZP, LI YC, et al. Chitinase-3 like-protein-1 function andits role in diseases[J]. Signal Transduct Target Ther, 2020, 5(1): 201. DOI: 10.1038/s41392-020-00303-7.[7]YANG H, ZHAO LL, HAN P, et al. Value of serum chitinase-3-likeprotein 1 in predicting the risk of decompensation events in patients with liver cirrhosis[J]. J Clin Hepatol, 2023, 39(7): 1578-1585. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1001-5256.2023.07.011.杨航, 赵黎莉, 韩萍, 等. 血清壳多糖酶3样蛋白1(CHI3L1)对肝硬化患者发生失代偿事件风险的预测价值[J]. 临床肝胆病杂志, 2023, 39(7): 1578-1585. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5256.2023.07.011.[8]MA L, WEI J, ZENG Y, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-originated exo⁃somal circDIDO1 suppresses hepatic stellate cell activation by miR-141-3p/PTEN/AKT pathway in human liver fibrosis[J]. Drug Deliv, 2022, 29(1): 440-453. DOI: 10.1080/10717544.2022.2030428. [9]NISHIMURA N, DE BATTISTA D, MCGIVERN DR, et al. Chitinase 3-like 1 is a profibrogenic factor overexpressed in the aging liver and in patients with liver cirrhosis[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2021, 118(17): e2019633118. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2019633118.[10]WANG CG, LI SZ, SHI JM, et al. Research progress in differentia⁃tion, identification, and purification methods of human pluripotent stem cells to mesenchymal-like cells in vitro[J]. J Jilin Univ Med Ed, 2023, 49(6): 1655-1661. DOI: 10.13481/j.1671-587X.20230634.王成刚, 李生振, 史嘉敏, 等. 体外人多能干细胞向间充质样细胞分化、鉴定和纯化方法的研究进展[J]. 吉林大学学报(医学版), 2023, 49(6): 1655-1661. DOI: 10.13481/j.1671-587X.20230634.[11]LI TT, WANG ZR, YAO WQ, et al. Stem cell therapies for chronicliver diseases: Progress and challenges[J]. Stem Cells Transl Med, 2022, 11(9): 900-911. DOI: 10.1093/stcltm/szac053.[12]YANG X, LI Q, LIU WT, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells in hepaticfibrosis/cirrhosis: From pathogenesis to treatment[J]. Cell Mol Im⁃munol, 2023, 20(6): 583-599. DOI: 10.1038/s41423-023-00983-5. [13]ZHAO SX, LIU Y, PU ZH. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes attenuate D-GaIN/LPS-induced hepatocyte apop⁃tosis by activating autophagy in vitro[J]. Drug Des Devel Ther, 2019, 13: 2887-2897. DOI: 10.2147/DDDT.S220190.[14]LEE CG, HARTL D, LEE GR, et al. Role of breast regression protein39 (BRP-39)/chitinase 3-like-1 in Th2 and IL-13-induced tissue re⁃sponses and apoptosis[J]. J Exp Med, 2009, 206(5): 1149-1166.DOI: 10.1084/jem.20081271.[15]HIGASHIYAMA M, TOMITA K, SUGIHARA N, et al. Chitinase 3-like 1deficiency ameliorates liver fibrosis by promoting hepatic macro⁃phage apoptosis[J]. Hepatol Res, 2019, 49(11): 1316-1328. DOI:10.1111/hepr.13396.收稿日期:2023-06-09;录用日期:2023-08-17本文编辑:邢翔宇引证本文:LIU PJ, YAO LC, HU X, et al. Effect of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells in treatment of mice with liver fibrosis and its mechanism[J]. J Clin Hepatol, 2024, 40(3): 527-532.刘平箕, 姚黎超, 胡雪, 等. 人脐带间充质干细胞(hUC-MSC)对肝纤维化小鼠模型的治疗作用及其机制分析[J]. 临床肝胆病杂志, 2024, 40(3): 527-532.读者·作者·编者《临床肝胆病杂志》推荐使用的规范医学名词术语有关名词术语应规范统一,以全国自然科学名词审定委员会公布的各学科名词为准。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

123Survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated by 4transarterial chemoembolisation (TACE)using DC Beads.5Implications for clinical practice and trial design6Marta Burrel 1, Q1,María Reig 2,3, ,Alejandro Forner 2,3,Marta Barrufet 1,Carlos Rodríguez de Lope 2,7Silvia Tremosini 2,Carmen Ayuso 1,3,Josep M Llovet 2,3,4,5,María Isabel Real 1,Jordi Bruix 2,3,⇑464748495051525354555657585960616263646566676869707172737475767778798081828384Patients and methods85Patient evaluation86The study population consisted of those patients treated with DEB-TACE at our 87institution between February2004and June2010,and was followed-up until 88June2011.After our phase II trial by Varela et al.[2]showing the safety and che-89motherapy pharmacokinetics of DEB-TACE,we had to wait for confirmatory stud-90ies to have the new material reimbursed for clinical practice.Because of this need, 91the cohort includes the22patients recruited in the Varela et al.study who did not 92receive TACE with Gelfoam during follow-up and82additional patients that were 93treated upon getting the allowance to use DEB.Patients treated by conventional 94TACE were excluded.95The inclusion criteria96by non-invasive criteria97early stage HCC[13]that98tion or had99patients following the100rhosis with preserved liver101mance status0[15],(6)102haemoglobin>8.5g/dl,103tion(albumin>2.8g/dl,104ferase<5times the upper105(serum creatinine<1.5106Exclusion criteria107fugal bloodflow,(2)108endovascular procedure,109Treatment110All patients received at111ted in a single session112assessed at one month.113(defined by the absence of114ing)retreatment was115a prospective study,some116referring centre.117DEB-TACE sessions118sion,extrahepatic spread119appearance of severe120taken as treatment failure121not appeared.When122were evaluated for second123have had this agent as the124No antibiotic125tered prior to treatment.126and fever attributed to127Angiographic technique128The procedure was129many).Diagnostic visceral130artery wasfirst performed131arterial anatomy,and the132gastric arteries were133sation material to these134artery was then carried out135imum intensity projection136multiphasic CT scan added137The end point of138tion.Chemoembolisation139sible in one single session.140feeder,and if this was not141we continued from142lesions were treated143lesions were treated with144mental arteries.For this145(Progreat,Terumo Europe,146eter(Excelsior,Boston147selective catheterisation was difficult,a0.01400microguidewire(Syncro;Boston 148Scientific,Boston,Massachussets)was used.DEB were loaded in the hospital 149pharmacy12h before use.Loaded beads were mixed with iodinate contrast with 150a proportion1:1(5ml of DC Beads in5ml of contrast),5–10min before injection.151 During the administration,we added contrast or saline depending on the concen-152 tration of beads andfluid density.We used3-ml injection syringes.Beads were153 administered under continuousfluoroscopic monitoring until stagnation offlow154 was achieved.Maximum dose administered was150mg of doxorubicin(two155 vials);dose was not tailored according to body surface or weight.The size of156 beads used in the Varela et al.study was500–700microns[2]in order to assess157 safety and minimise the risk of biliary damage by using smaller beads.Upon158 establishing safety when using smaller beads by other authors,we used300–159 500microns in the remaining patients.These are preferred as the potential160 microcatheter clogging is almost completely avoided.If stagnation offlow was161 not achieved after the injection of two DEB vials,we continued injecting non-162 loaded spherical particles of300–500microns(BeadBlock).Afinal angiography163 to confirm complete tumour devascularisation was performed in all cases.164165tumour evaluation were166examination,laboratory167adverse events following168which determines169170follow-up imaging with171late venous phases)using172scanner with120ml of173reconstructed at4-mm174is recommended when175non-prospective collec-176to ensure that timing177Accordingly,assessment of178evaluated and we only179of validation and registra-180181that is defined as develop-182of limiting technical183invasion or extrahe-184of liver failure[16].185186range and categorically as187to BCLC staging.Differ-188test or Fisher’s189test or non-parametric U-190power of clinical and191according to the median192on each clinical and bio-193survival.Survival rates194method,and compared1950.05was considered sig-196Analysis was done with-197of liver transplantation198of these treatments on the19920018(SPSS Inc.,Chicago,201202203204patients received205met the inclusion206excluded patients207The baseline charac-208one patient were cir-209etiology of cirrhosis210 was HCV(62.5%),followed by ethanol(25%)and HBV(6.7%).All211 patients were asymptomatic(PS0100%)and41out of104212 (39.4%)corresponded to BCLC A stage.These patients had eitherResearch Article2Journal of Hepatology2012vol.xxx j xxx–xxx213214215216217218219220221222223224225226227228229230Q4231232233234235236237238239240After a median follow-up of24.5months(2.6–79.6),64patients 241were alive,38patients had died and two had received trans-243244245246247248249250251252253254255256257258259260261Q5262263264265266267268269270 one hepatic subcapsular haematoma,one pancreatitis,one biliary271 dilatation not related to tumour and one severe pain.One patient272 with arterial dissection developed a pseudoaneurysm that wasTable1.Baseline clinical characteristics of patients.There were no statistical differences in any parameter between both groups.Q10JOURNAL OF HEPATOLOGYJournal of Hepatology2012vol.xxx j xxx–xxx3273274embolisation.The second dissection was self-limited and did 275notprevent further embolisation.The subcapsular bleedingwas 276successfully managed conservatively without need for further277278279280281282283284285286287288289290291292293294295296297298299300301302303304305306307Q6308309310311312313that patients treated with TACE may present objective response,314but during follow-up they may present with new tumour sites315and qualify as disease progression.Intrahepatic progression4Journal of Hepatology 2012vol.xxx j xxx–xxx316may be again treated with TACE,but in some instances contrain-317dications due to tumour burden(extrahepatic spread,vascular 318invasion)or to liver function impairment may argue against 319treatment repetition.As a consequence,we have two types of dis-320ease progression:(i)treatable progression that may again achieve 321disease control,and(ii)untreatable progression that may prime 322initiation of systemic therapy that now should be sorafenib.We 323registered such transition to sorafenib in24patients(it occurred 324after the approval of the drug in2008)and radioembolisation in 325one patient.To avoid any confounding survival improvement due 326to treatment with transplantation,sorafenib or radioembolisa-327tion,we performed the survival analysis censoring follow-up at 328the time of these329icantly diverge and330not be attributed to331also checked if the332stage A patients,333have such an334BCLC A patients was335but even so the3364years confirming337sequence of a biased338It is important to339to cancer are340In our group,this is341is equivalent to the342a better life343after surgical344disease;and in our345of TACE,we346pendent predictor of347of symptoms is348its to decide349given intervention.350able treatment351than on survival352but the outcome353is the case when354invasion.It might be355but survival is356by the recognition of357dictor[9,10,22].This358gery for359already in place.The360than when tumours361is well preserved,362survival data of363a selective policy364all sorts of patients.365Our data provide366achieved with TACE367gery or368vival assumptions369this issue exceeds370of donors and the371according to372make our survival373about expanding the374In addition,if375ment are designed with survival as an end point,the baseline 376expectancy should no longer be a2-year median survival,but377 rather twice as much.Several trials are now ongoing,testing378 the combination of molecular targeted agents with TACE or even379 the comparison of conventional TACE vs.DEB-TACE.If the inclu-380 sion criteria for such trials do not carefully define the target pop-381 ulation,any positive or negative outcome data may be the result382 of an underestimation of the baseline assumptions and events to383 register during follow-up.384 The confirmation of the safety of DEB-TACE in a large cohort of385 HCC patients is worthwhile as the evaluation of any novel device386 for human use requires repeated prospective validation.In that387 sense,one of the data that has raised concerns on the use of388 DEB is the incidence of hepatic abscess.This complication is well389used for the pro-390is an optimal cul-391after TACE,the392increases the risk,393abscess may develop.394days after the proce-395to prevent it.This is396to our patients.It is397comparing conven-398hepatic abscess was399can be derived400the incidence ranged401Q7adverse events are402to the agent used for403is the capacity to404its passage into405better tolerance due406shown in the Preci-407use of higher doxo-408incidence of major409it might be410enhances the411of the multidrug412A higher response413in Precision V414rate assessment415not been validated.416changes in417techniques,and ifuptake and reten-419assessment.420response rate as it421because of heteroge-422to revisit the423on the patients’424425of DEB-TACE in426optimal criteria and427be assumed in clini-428decide between con-429and also to design430of treatment.431432This study has been supported by a grant from the Instituto de433Salud Carlos III(PI11/01830).CIBERehd is funded by Instituto434de Salud Carlos III.JOURNAL OF HEPATOLOGY Journal of Hepatology2012vol.xxx j xxx–xxx5435Carlos Rodríguez de Lope is supported by a grant of the Insti-436tuto de Salud Carlos III.437(FI09/00510).Silvia Tremosini was partially supported by a 438grant from BBVA foundation.Maria Reig was partially supported 439by a grant from the University of Barcelona(APIF RD63/2006). 440Josep M.Llovet is supported by grants from the US National Insti-441tutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases 442(1R01DK076986–01),the European Commission’s Framework 443Programme7(HEPTROMIC,Proposal No:259744),and the Span-444ish National Health Institute(SAF-2010-16055).445Conflict of interest446J.Bruix had exerted447tomo,Pharmexa,448ing,Lilly,Novartis,449 C.Ayuso,M.450had exerted as451M.Barrufet452Biocompatibles.453J.M.Llovet454ceutical,Bristol455Bayer456Biocompatibles.457References458[1]Bruix J,Sherman M.459Hepatology460[2]Varela M,Real MI,461olization of462doxorubicin463[3]Poon RT,Tso WK,464chemoembolization465drug-eluting bead.466[4]Malagari K,467et al.Transarterial468cinoma with drug469patients.Cardiovasc470[5]Lammer J,Malagari471Prospective472the treatment of473Cardiovasc InterventQ8474[6]Llovet JM,Real MI,475embolisation or476patients with477trolled ncet478 [7]Lo CM,Ngan H,Tso WK,Liu CL,Lam CM,Poon RT,et al.Randomized479 controlled trial of transarterial lipiodol chemoembolization for unresectable480 hepatocellular carcinoma.Hepatology2002;35:1164–1171.481 [8]Raoul JL,Sangro B,Forner A,Mazzaferro V,Piscaglia F,Bolondi L,et al.482 Evolving strategies for the management of intermediate-stage hepatocellu-483 lar carcinoma:available evidence and expert opinion on the use of484 transarterial chemoembolization.Cancer Treat Rev2011;37:212–220.485 [9]Luo J,Guo RP,Lai EC,Zhang YJ,Lau WY,Chen MS,et al.Transarterial486 chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma with portal487 vein tumor thrombosis:a prospective comparative study.Ann Surg Oncol488 2011;18:413–420.489 [10]Hu HT,Kim JH,Lee LS,Kim KA,Ko GY,Yoon HK,et al.Chemoembolization for490 hepatocellular carcinoma:multivariate analysis of predicting factors for491 tumor response and survival in a362-patient cohort.J Vasc Interv Radiol492493trials for unresectable494survival.Hepatol-495496carcinoma.Hepatology497498Lancet2011.499Williams R.Transection500varices.Br J Surg501502status assessment503study.Br J Cancer504505R,et al.Clinical decision506Pivotal role of imaging507508Y,Kojiro M,et al.Overall509with or without510propensity score511512S,Spyridopoulos T,513chemoembolization with514with BeadBlock for5152010;33:541–551.516B,Romano A,et al.517early-stage hepatocellu-518treatment:a prospective519Q9520T,et al.Prospective cohort521hepatocellular522523A.Transarterial524versus transarterial525carcinoma.J526527H,Kelekis A,Dourakis528Chemoembolization with529(HCC)Patients.530531Research Article6Journal of Hepatology2012vol.xxx j xxx–xxx。