Estimation of safety distances in the vicinity of fuel gas pipelines

Triangulation

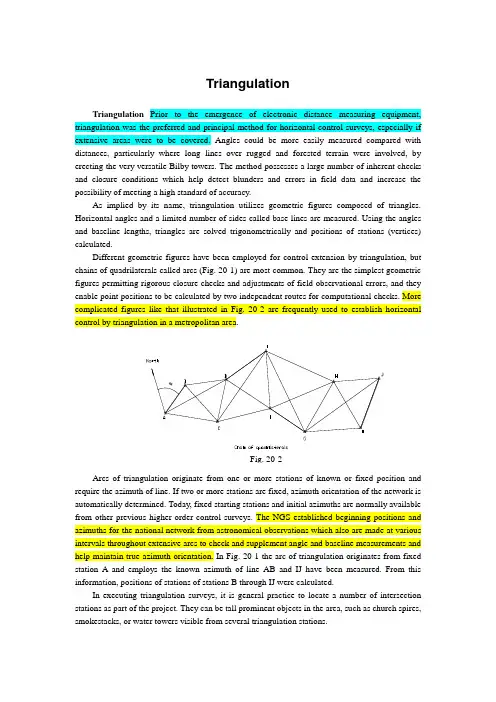

TriangulationTriangulation Prior to the emergence of electronic distance measuring equipment, triangulation was the preferred and principal method for horizontal control surveys, especially if extensive areas were to be covered. Angles could be more easily measured compared with distances, particularly where long lines over rugged and forested terrain were involved, by erecting the very versatile Bilby towers. The method possesses a large number of inherent checks and closure conditions which help detect blunders and errors in field data and increase the possibility of meeting a high standard of accuracy.As implied by its name, triangulation utilizes geometric figures composed of triangles. Horizontal angles and a limited number of sides called base lines are measured. Using the angles and baseline lengths, triangles are solved trigonometrically and positions of stations (vertices) calculated.Different geometric figures have been employed for control extension by triangulation, but chains of quadrilaterals called arcs (Fig. 20-1) are most common. They are the simplest geometric figures permitting rigorous closure checks and adjustments of field observational errors, and they enable point positions to be calculated by two independent routes for computational checks. More complicated figures like that illustrated in Fig. 20-2 are frequently used to establish horizontal control by triangulation in a metropolitan area.Arcs of triangulation originate from one or more stations of known or fixed position and require the azimuth of line. If two or more stations are fixed, azimuth orientation of the network is automatically determined. Today, fixed starting stations and initial azimuths are normally available from other previous higher-order control surveys. The NGS established beginning positions and azimuths for the national network from astronomical observations which also are made at various intervals throughout extensive arcs to check and supplement angle and baseline measurements and help maintain true azimuth orientation. In Fig. 20-1 the arc of triangulation originates from fixed station A and employs the known azimuth of line AB and IJ have been measured. From this information, positions of stations of stations B through IJ were calculated.In executing triangulation surveys, it is general practice to locate a number of intersection stations as part of the project. They can be tall prominent objects in the area, such as church spires, smokestacks, or water towers visible from several triangulation stations.Triangulation Reconnaissance One of the most important aspects of any triangulation survey is the reconnaissance and selection of stations. Factors to be considered are (1) strength of figure, (2) station intervisibility, (3) station accessibility for the original triangulation observing part and surveyors who will subsequently use the stations, and (4) overall project efficiency. Careful attention must be given to each factor in planning and designing the optimum triangulation network; for a given project.Strength of figure deals with the relative accuracies of computed station positions that result from use of angles of various sizes in calculations. Triangulation computations are based on the trigonometric law of sines. The sine function changes significantly for angles near 0°and 180°so a small observational error in an angle close to these values produces a comparatively large difference in position calculations. Conversely, sines of angles near 90 change very slowly; thus,a small observational error in that region causes little change in the computed position since similar observational errors are expected for each angle, design of triangulation figures having favorable angle sizes increases overall triangulation accuracy.Rigorous procedures beyond the scope of this book have been developed for evaluating relative strengths of geometric figures used in triangulation. In general, angles approximately 90°are optimum, and if no angles smaller than 30°or larger than 150°are included in calculations, the figure should have sufficient strength. Locations of triangulation stations fix the angle sizzes so they must be planned carefully for maximum strength of figure. If local terrain or other conditions preclude use of figures having strong angles. More frequent base-line measurements are necessary.Station intervisibility is vital in triangulation because lines of sight to all stations within each figure must be clear for measuring angles. Preliminary decisions on station placement an be resolved from available topographic maps. Intervening ridges that might obstruct sight lines are checked by plotting profiles of the lines between stations. Trees on line and, for long lengths, the combined effects of earth curvature and refraction are additional factors affecting station intervisibility. After making a preliminary decision on station locations, a visual test should be made by visiting each proposed site. Stations are normally placed on the highest points in an area and,if necessary, towers erected to elevate the theodolite, observer, and targets above the ground stations. Because of the uncertainty of refraction near the ground, lines of sight should be kept at least 10 ft above it and not graze intervening ridges.Field Measurements for Triangulation As previously stated, the basic field measurements for triangulation are horizontal angles and base-line lengths. Angles can be measured suing repeating instruments, or more likely directional theodolite such as the Kern DKM-3 having a plate bubble sensitivity of 10-sec/2-mm division, or the Wild T-3 with a 7-sec bubble sensitivity. Both theodolite are suitable for first-order work and permit angles to be read by estimation to the nearest 0.1 sec.To reduce effects of atmospheric refraction on high-order triangulation, observations are made at night with lights for targets. At each station, several “positions”are read; a position consists of angles or directions distributed around the horizontal circle of the instrument in both the direct and plunged modes. With directional theodolite, to compensate for possible circle graduation errors, the circle is advanced by approximately 180°/n for each successive position, where n is the number of positions at the station. Angles should be computed in the field from the directions, checked for acceptable misclosure, and any rejected ones repeated before leaving the station. The average of all satisfactory values for each angle is used in the triangulation calculations.Base lines now preferably are measured by electronic methods, which produce excellent accuracies. Precise Invar tapes may also be used. Several measurements should be made in both directions. Slope distances must be reduced to horizontal and mean sea level lengths calculated, sea level distances are converted to grid lengths by applying scale factors.Triangulation Adjustment Errors that occur in angle and distance measurements require and adjustment. The most rigorous method utilizes least squares. In that procedure, all angle measurements plus distance or azimuth observations can be simultaneously included in the adjustment, and any configuration of quadrilaterals or more complicated figures handled to get station positions having maximum probability. The theory is beyond the scope of this text.Other approximate methods for triangulation adjustments, easily applied to standard figures such as quadrilaterals, also give satisfactory results and are described in advanced surveying books.。

矿井目标定位中移动信标辅助的距离估计新方法

矿井目标定位中移动信标辅助的距离估计新方法胡青松;耿飞;曹灿;张申【摘要】为了降低测距不准对矿井目标定位精度的影响,提出一种移动信标辅助的距离估计方法MBDisEst.该方法由安装有惯导设备或/和激光定位装置的瓦检员或矿车充当移动信标,它们通过与矿山物联网中的其他设备交换信息校准自身坐标.MBDisEst以移动信标和目标节点之间的相对运动和几何约束为基础,利用加权最小二乘法计算目标节点与虚拟信标的距离,可将静止和运动目标的距离估计统一在同一框架.仿真结果表明:MBDisEst的测距精度比TOA的测距精度高,其测距误差随移动信标速度的增大而增大,随移动信标通信半径的增加而减小,基于MBDisEst的定位方法具有较高的定位精度.%To mitigate the affection of the inaccurate distance measurement on the accuracy of the localization system in coal mines, an improved distance estimation method assisted by mobile beacons called MBDisEst was proposed. Some gas inspectors and mining cars equipped with inertial navigation equipment or/and laser positioning devices were selected as mobile anchors, which communicated with other devices for Internet of mine things to calibrate their own coordinates. MBDisEst computed the distances between target nodes and virtual anchors using weighted least square method based on their relative motion and geometrical restriction, and combined static and mobile target scenarios into a unified framework. The simulations show that the distance measurement accuracy of MBDisEst is larger than TOA's, and the measurement error grows up with the speed of mobile anchors and goes down with the communication range of mobile anchors. And thelocalization methods based on distance measurement of MBDisEst has larger accuracy.【期刊名称】《中南大学学报(自然科学版)》【年(卷),期】2017(048)005【总页数】7页(P1227-1233)【关键词】移动信标辅助;矿井目标定位;距离估计;定位精度【作者】胡青松;耿飞;曹灿;张申【作者单位】中国矿业大学信息与控制工程学院,江苏徐州,221008;矿山互联网应用技术国家地方联合工程实验室,江苏徐州,221008;国网北京经济技术研究院徐州勘测设计中心,江苏徐州,221005;中国矿业大学信息与控制工程学院,江苏徐州,221008;矿山互联网应用技术国家地方联合工程实验室,江苏徐州,221008;中国矿业大学信息与控制工程学院,江苏徐州,221008;矿山互联网应用技术国家地方联合工程实验室,江苏徐州,221008【正文语种】中文【中图分类】TD676矿井目标定位系统有助于煤矿企业合理地调配资源,在矿难发生时快速确定受困人员位置[1−2],是煤矿必须配备的安全避险设施之一。

油田生产设施环境安全距离理论与估算方法初探

油田生产设施环境安全距离理论与估算方法初探张 震1,李 巍1,王志强2,郭 霁2(1.北京师范大学环境学院环境模拟与污染控制国家重点联合实验室,北京100875;2.中国石油化工股份有限公司胜利油田技术检测中心,山东东营257000)摘 要:石油生产会带来各种不利的环境影响,甚至造成许多重大安全隐患,并由此对区域生态环境构成严重威胁。

对此笔者提出环境安全距离概念及其理论模型,并结合油田主要生产设施的环境影响分析,给出了油田生产过程中气体污染物排放、噪声污染、井喷、管线泄漏和火灾爆炸的环境安全距离估算方法,从而为减轻油田生产的潜在环境影响和损害,解决城市规划建设与油田已建设施之间的矛盾和确保油田生产的环境安全提供科学依据和管理对策。

关键词:油田;生产设施;风险;环境安全;距离中图分类号:TE687 文献标识码:A 文章编号:167121556(2005)0420095204Studies on the Theory and Estim ation Methods of E nvironmental S afety Distance of the Production F acilities in Oil FieldsZHAN G Zhen1,L I Wei1,WAN G Zhi2qiang2,GUO Ji2(1.S t ate J oi nt Key L aboratory of Envi ronment al S i m ul ation and Poll ution Cont rol,S chool of Envi ronment,B ei j i ng N orm al U ni versit y,B ei j i n g100875,Chi na;2.Technical Ex ami nation Center of S hengli Oil Fiel d,Chi na Pet rochemicalCor poration L imited,Dong y i n g257000,Chi na)Abstract:During t he p rocess of oil production,some negative environmental impact s are usually brought a2 bout toget her wit h environmental risks.Wit h t he develop ment of cities,especially t hose built originally upon t he oil fields,t he conflict s between urban planning of t hese cities and t he p roduction facilities of oil fields have become increasingly prot ruding,and even resulted in increased potential of environmental haz2 ards t hat in t urn constit ute serious t hreat s to t he ecological environment of t he cities.In order to ensure t he safe p roduction of oil fields and t he ecological security of cities,t he concept and t he t heoretical model of environmental safety distance are set up to prevent t he sensitive or valuable environmental component s f rom t he potential environmental impact s or hazards bro ught abo ut by t he p roduction facilities in oil fields. The met hods or models for estimating t he environmental safety distances are established in terms of t he major environmental pollutions or risks including exhaust s,noise,well blowout,leakage of pipes,fire and blast.They p rovide scientific bases and measures for developing environmental safety management,mitiga2 ting t he potential environmental hazards during t he oil p roduction and preventing t he conflict s.K ey w ords:oil fields;production facilities;risk;environmental safety;distance0 引 言随着国家能源需求的飞速增长,油田的开采和生产规模不断扩大。

双目视觉自动检测香蕉植株假茎茎高茎宽

affect the detection accuracy. In the short-distance measurement mode, the measurement accuracy at the 1.2 m distrom the true value reaches 0.8538, and the relative error is only 2.0%.

双目视觉自动检测香蕉植株假茎茎高茎宽

摘要

实时快速的提取植物表型信息已经成为农业生产发展中极为关 键的一步,可以为植物的预测和检测提供帮助。香蕉作为广西重点发 展的水果,实时的测量香蕉假茎茎宽茎高可以为香蕉植株生长参数和 后期的产量评估的提取提供有效的帮助。

本文以香蕉植株为研究对象,通过双目立体视觉与级联分类器结 合的方法来实现香蕉植株假茎茎宽茎高的快速无损测量,设计了一种 基于双目相机的图像测量方法。主要的研究内容包括:

(3) 设计了一种香蕉假茎茎高茎宽联合估算方法。该方法主要针 对远距离测量方式下已获取得到完整的假茎主体的情况。在上一步同 样方法测量得到茎宽参数的同时,也通过两点的间的距离公式计算假 茎的的根部到最低叶片分支下最细的假茎处的置距离的方法得到茎 高的测量结果。结果表明,不同的测量距离会影响检测精度,1.8 m 距离处的香蕉植株假茎茎高茎宽测量精度最高,茎高的识别模型与真 实值的 R2 达到了 0.9717,相对误差仅为 3.1%;茎宽的识别模型与真 实值的 R2 达到了 0.9653,相对误差仅为 1.2%。

(1) The cascade classifier recognizes the pseudo-stem of bananas. According to different measurement purposes, two batches of experiments were carried out, using close distances (0.9 m, 1.2 m, 1.6 m, 1.9 m, some pseudo-stem can be photographed), and long distances (1.8

leg的英语俚语

leg的英语俚语The term "leg" in English slang can refer to a variety of different meanings and contexts. While the literal definition of a leg is one of the two lower limbs of the human body, the slang usage of this word has evolved to encompass all sorts of additional connotations. In this essay, we'll explore the many different ways the word "leg" is used in colloquial English speech and writing.One of the most common slang uses of "leg" is to describe a unit of distance or measurement. For example, someone might say they had to "walk a few legs" to get somewhere, meaning they had to walk a fair distance. This usage stems from the idea that the length of one's leg can be used as a rough estimation of measurement. In the same vein, a person could refer to the "legs" of a journey, meaning the different segments or stages of travel from one place to another.The word "leg" is also often used in sports and athletic contexts. In baseball, for instance, a "leg" can refer to a single base that a runner reaches safely. Getting a "pair of legs" would mean successfully advancing to two bases. Similarly, in horse racing, the differentsections of a race are sometimes called the "legs" of the competition.A horse that wins multiple "legs" of a race series is considered particularly impressive. Even non-sporting activities like hiking can involve "legs" - the different trail sections or converted distances covered during a hike.When it comes to slang related to the human body, "leg" takes on some more colorful connotations. Someone with "good legs" is often considered physically attractive, particularly in reference to a woman's legs. Complimenting a person's "gams" is a more old-fashioned way of commenting on their nice legs. On the flip side, a person who is perceived as unattractive or lacking in physical appeal might be described as having "bum legs."The word "leg" can also be used idiomatically to express other ideas. If someone is said to be "pulling your leg," they are joking or fibbing, trying to trick the listener. Asking someone to "leg it" is a way of telling them to hurry up and get moving. In gambling or gaming, a "leg up" refers to an advantage or head start. And if a plan or scheme is described as having "legs," it means it has longevity and staying power.Interestingly, "leg" has taken on some sexual connotations in slang as well. In this context, it can be used as a verb meaning to engage in sexual activity or flirtation with someone. A person might "leg"another individual at a party, for instance. The term "leg over" is an even more explicit sexual reference. While these usages tend to be considered quite crass, they illustrate how versatile and multifaceted the word "leg" can be in colloquial speech.Beyond just the human body, "leg" has also become a slang term in certain industries and subcultures. In aviation, for example, a "leg" refers to a single flight segment of a longer journey. Pilots and airline staff will often speak of the "legs" of a trip. In the world of crime and law enforcement, a "leg" is used to describe a lead or clue in an investigation. Detectives may pursue different "legs" of a case in search of answers.The slang use of "leg" is not limited to English either. Many other languages have adopted similar colloquial usages of this word. In Spanish, for instance, "la pata" (the leg) can be used informally to refer to a person's foot or lower limb. In French, "une jambe" (a leg) might be used to signify a portion or section of something. These linguistic parallels demonstrate how the slang application of "leg" has become a widespread phenomenon.Ultimately, the versatility of the word "leg" in English slang reflects the central importance of this body part in human experience and culture. From measuring distance to expressing sexuality, legs play a crucial role in our physical, spatial, and metaphorical understandingof the world. The many slang usages of this term highlight just how deeply embedded our conception of "legs" is in the fabric of everyday language and communication. Whether used literally or figuratively, the word "leg" continues to be a rich source of linguistic creativity and expression.。

理工英语3形考答案

理工英语3形考答案—Are you going on holiday for a long time? 正确答案是:No. Only a couple of days.—Do you mind if I smoke here? 正确答案是:Yes, better not. —Does she speak French or German? 正确答案是:either —How did you miss your train? 正确答案是:Well, I was caught in the traffic jam.—How is everything going? 正确答案是:As you can see—I suppose there'll be a lot of arguments. 正确答案是:I should imagine so.—I wish you success in your career. 正确答案是:The same to you.—I wonder if I could use your computer tonight? 正确答案是:Sure, go ahead.—I'd like to take a look first at those structural support beams that were going to be put in place on the second floor. 正确答案是:Certainly—If you invite a Muslim to dinner, what are you advised not to order for him? 正确答案是:pork.—I'm dog tired. I can't walk any further, Tommy. 正确答案是:Come on—I'm leaving for Shanghai tomorrow. 正确答案是:Have apleasant trip!—In what form will you take the investment? 正确答案是:We'll contribute a site and the required premises.—Is it more advisable to upgrade our present facilities than taking the risk of opening a new park? 正确答案是:I don't think so. —Is it possible for you to expand business there?正确答案是:Yes, I think so.—It's getting dark. I'm afraid I must be off now. 正确答案是:See you.—I've started my own software company. 正确答案是:No kidding! Congratulations!—Jack won't like the film, you know. 正确答案是:So what? —Sorry, I made a mistake again. 正确答案是:Never mind. —What vegetables are in season now? 正确答案是:I think —When do we have to pay the bill? 正确答案是:By—Who should be responsible for the accident? 正确答案是:as told—Would you like some more beer? 正确答案是:Just a little ______ these potential problems, two-way radios are preferable as they are extremely reliable for short distances and can broadcast to several people at once. 正确答案是:Given–__________ father took part in the charity activity in theneighbourhood yesterday? 正确答案是:Whose__________ important it is for kids to imagine freely! 正确答案是:How—________________ about it now? 正确答案是:What's being done A budget is an estimation of the _______ and _______ over a specified future period of time. 正确答案是:revenue; expensesA bus driver _______________ the safety of his passengers. 正确答案是:is responsible forA campus emergency ______ occur at any time of the day or night, weekend, or holiday, with little or no warning. 正确答案是:may。

古代没有尺子时人们测量长度英文作文

古代没有尺子时人们测量长度英文作文Firstly, the human body served as an inherent measuring device. The 'cubit', for instance, was a widely used unit derived from the distance between the elbow and the tip of the middle finger. Similarly, the 'foot' corresponded to the average length of an adult's foot, while the 'handspan' equaled the breadth of an outstretched hand. These body-based measurements offered a portable, readily accessible standard that could be easily replicated across diverse populations.Secondly, nature provided a wealth of reference points for length estimation. The height of a fully grown man or the length of a specific plant species, such as a stalk of wheat, served as fixed benchmarks. The distance covered by a certain number of paces or the time taken to walk a known route were also employed to estimate distances. Moreover, the shadow cast by a vertical object at a specific time of day, leveraging the principles of sundial, helped determine shorter lengths.Thirdly, primitive yet effective tools were devised to enhance precision. The 'knotted rope' or 'string line,'marked with uniform intervals, allowed for linear measurements. The 'groma,' an early surveying instrument, facilitated the alignment and measurement of right angles in construction projects. Additionally, the 'water level,' utilizing the principle of communicating vessels, enabled the leveling and measurement of horizontal distances.These methods, though seemingly rudimentary, were grounded in keen observation, empirical knowledge, and a deep understanding of the natural world. They fostered a communal sense of standardization, as individuals within a community would have similar bodily proportions and shared familiarity with local flora and environmental cues. Moreover, they were adaptable to various contexts and scalable through repetition or multiplication, ensuring a degree of reliability in construction, trade, and land division.In conclusion, the absence of modern-day rulers did not deter ancient civilizations from measuring lengths accurately. Instead, it prompted them to harness their innate physical attributes, tap into the timeless rhythms of nature, and devise innovative tools, thereby exemplifying human ingenuity and adaptability in the faceof adversity. These early measurement practices laid the groundwork for the development of standardized units and sophisticated instruments that we rely on today, serving as a testament to mankind's ceaseless pursuit of quantification and precision.。

Am. J. Epidemiol.-2006-Yasui-697-705

Practice of EpidemiologyFamilial Relative Risk Estimates for Use in Epidemiologic AnalysesYutaka Yasui 1,Polly A.Newcomb 2,3,Amy Trentham-Dietz 3,and Kathleen M.Egan 41Department of Public Health Sciences,School of Public Health,University of Alberta,Edmonton,Alberta,Canada.2Cancer Prevention Program,Division of Public Health Sciences,Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center,Seattle,WA.3University of Wisconsin Comprehensive Cancer Center,Madison,WI.4Vanderbilt University School of Medicine and Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center,Nashville,TN.Received for publication August 7,2005;accepted for publication March 21,2006.Commonly used crude measures of disease risk or relative risk in a family,such as the presence/absence of disease or the number of affected relatives,do not take into account family structures and ages at disease oc-currence.The Family History Score incorporates these factors and has been used widely in epidemiology.How-ever,the Family History Score is not an estimate of familial relative risk;rather,it corresponds to a measure of statistical significance against a null hypothesis that the family’s disease risk is equal to that expected from reference rates.In this paper,the authors consider an estimate of familial relative risk using the empirical Bayes framework.The approach uses a two-level hierarchical model in which the first level models familial relative risk and the second considers a Poisson count of the number of affected relatives given the familial relative risk from the first level.The authors illustrate the utility of this methodology in a large,population-based case-control study of breast cancer,showing that,compared with commonly used summaries of family history including the Family History Score,the new estimates are more strongly associated with case-control status and more clearly detect effect modification of an environmental risk factor by familial relative risk.Bayes theorem;family;Poisson distribution;regression analysis;riskAbbreviations:AFB,age at first birth;CBCS II,Collaborative Breast Cancer Study II;FSIR,Familial Standardized Incidence Ratio;MLE,maximum likelihood estimator.Estimates of disease relative risk in families have impor-tant utilities in investigations of disease etiology.They are used to examine whether the disease of interest clusters in certain families and whether its etiology has a familial component.They are also used to adjust for familial ag-gregations when evaluating the effects of other nonfamilial etiologic factors in epidemiologic studies.Furthermore,familial relative risk estimates are used to examine effect modification of an etiologic factor according to levels of disease relative risk in families.Finally,a valid assessment of familial relative risk may have important clinical utility in triaging persons for more involved genetic screening and informing family members about potential risks.In spite of the important utilities,family history informa-tion is often handled rather crudely in epidemiologic analy-ses.A commonly used summary of family history is a binary indicator (yes/no)of whether study participants have af-fected family members,often gender specific,in first-or second-degree relatives.Another summary that carries a little more information is the number of affected family members.These crude summaries have two critical deficien-cies in view of their use as familial relative risk estimates.First,they do not account for family size,structure,or ages of family rger families and families with older members are naturally more likely to have members who have developed chronic diseases such as cancer.Second,theCorrespondence to Dr.Yutaka Yasui,Department of Public Health Sciences,University of Alberta,13-106J Clinical Sciences Building,Edmonton,Alberta T6G 2G3,Canada (e-mail:yyasui@ualberta.ca).697Am J Epidemiol2006;164:697–705American Journal of EpidemiologyCopyright ª2006by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health All rights reserved;printed in U.S.A.Vol.164,No.7DOI:10.1093/aje/kwj256Advance Access publication August 21,2006at :: on November 11, 2014/Downloaded fromcrude summaries do not take chance into account:families with identical familial relative risk levels,sizes,structures,and ages can yield different numbers of affected members by chance alone.Kerber (1)proposed the Familial Standardized Incidence Ratio (FSIR)as a measure of familial relative risk that ac-counts for family size,structure,or ages of family members.Boucher and Kerber (2)applied a linear empirical Bayes approach to log f 1þlog(1þFSIR)g with a normality as-sumption to its underlying true values.In this paper,we extend Kerber’s method for estimating familial relative risk levels,applying empirical Bayes estimation methods with a nonparametric discrete prior distribution to overcome the deficiencies of the crude summaries.Following a brief re-view of the Family History Score (3),which was proposed for the same reasons as described above,we explain why it is actually not an estimate of familial relative risk.The utility of the new method proposed here is shown in a large,population-based case-control study of breast cancer.Two main points are illustrated.First,the empirical Bayes esti-mates of familial relative risk are associated with case-control status more strongly than other summary measures of family history,including Family History Scores.Second,they detect an effect modification of an environmental risk factor according to the level of familial relative risk more clearly than do other summary measures.In the Discussion section of this paper,we outline the potential use of the empirical Bayes familial relative risk estimates in other areas of public health and clinical research.FAMILY HISTORY SCOREA method previously proposed to overcome the defi-ciencies of the crude summaries and used widely in epide-miologic analyses is the Family History Score (3).In thisapproach,an expected risk of the disease of interest is com-puted for each family member by using a set of external reference rates for the disease.For i th family’s j th member,the expected risk E ij is given by the cumulative risk of the disease under observation (4):E ij ¼1ÿexp ÿXkk k t ijk !;where k k is the external reference rate for the k th stratum(e.g.,age-sex-race–defined stratum)and t ijk is the length of time that i th family’s j th member spent under observation in the k th stratum.Ages of family members are accounted for in the computation of the expected risks.The Family His-tory Score Z i for i th family is defined byZ i ¼P j O ij ÿP j E ijPj E ij ð1ÿE ij Þn o ;where O ij is the disease indicator of i th family’s j th mem-ber.If the disease is rare,then E ij is approximately equal to Pk k k t ijk and E ij ð1ÿE ij Þ E ij ;resulting in a simpler formula:Z i ¼P j O ij ÿPj E ij Pj E ij1=2:The Family History Score Z i is in the form of a test sta-tistic,which suggests a measure of statistical significance against a null hypothesis that the disease risk for each family member is equal to the expected risk computed from the external reference rates.A Bernoulli random variable O ij has the ‘‘success probability’’E ij under the null hypothesis and,accordingly,we haveE XjO ij 2435¼X jE ij Var XjO ij 2435¼X jE ij ð1ÿE ij Þ;where the variance formula assumes that O ij ’s within each family are uncorrelated.The Family History Score Z i can then be seen as a test statistic in the form of ðX ÿE ½X Þ=ðVar ½X Þ1=2that usually leads to a standard normal large-sample distribution,where the large sample refers to the size of each family being large.A Family History Score is actually not an estimate of the familial relative risk level.It is a test statistic for a null hypothesis that the disease risk for each family member is equal to the expected risk computed from the external ref-erence rates.Statistical significance determined by the ob-served value of a test statistic is a function of a sample size (i.e.,family size,structure,and ages)as well as the degree of departure from the null hypothesis (i.e.,familial relative risk levels).Data for larger families tend to give higher statistical significance and therefore larger absolute values of Family History Scores given the same level of familial risk.Note also that the numeric values of Family History Scores cannot be interpreted directly.They suggest statis-tical significance levels determined according to a known probability distribution of the test statistic.In other words,Family History Scores order families by statistical signifi-cance against the null hypotheses,but their numeric values require a metric,the known probability distribution of the test statistic,in order to have interpretable numeric distances between them.These considerations have led us to a dif-ferent approach to estimating familial relative risk levels,which shares similarities with the methods of Kerber (1)and of Boucher and Kerber (2).EMPIRICAL BAYES ESTIMATES OF FAMILIAL RELATIVE RISKWe define the familial relative risk of the disease for i th family as the relative risk of the disease shared by the mem-bers of i th family relative to the external reference.Our model isE ½O ij ¼h i E ij ;698Yasui et al.Am J Epidemiol 2006;164:697–705at :: on November 11, 2014/Downloaded fromwhere O ij ’s are Bernoulli random variables conditionally independent given h i ’s.We may estimate h i by maximiz-ing the sum of the Bernoulli log-likelihood for i th family.The score equation that the maximum likelihood estimator(MLE)ˆhi satisfies is Pj ðO ij ÿˆh i E ij ÞP j ˆh ið1ÿˆh i E ij Þ¼0and the MLE can be simplified to ˆh i ¼P j O ij =P jE ij ;the standardized mortality (or incidence)ratio,under the rare disease assumption.The precision of the MLEs variesacross families,however,because ˆhi is based solely on i th family’s data,and family sizes,structures,and ages differ across families.Small families with Pj O ij 1could yieldextremely high values of ˆhi ’s just by chance alone.Similar difficulties with the MLEs can occur in other bio-statistical applications such as estimation of small-area dis-ease risks (5)and comparison of risk across hospitals for a given medical procedure (6).A common feature shared by these problems is that there are many parameters to be es-timated,each of which is indexed by one of the units of var-ious sizes (e.g.,families,small areas,and hospitals),and the data available from each unit are limited.As a consequence,extreme values of MLEs occur for small units corresponding to very large variances of MLEs.Such difficulties with MLEs can be alleviated by theuse of hierarchical models in which ˆhi ’s are considered random quantities and are modeled in an additional hier-archical layer.Specifically,the hierarchical model takes the formO ij ’s given h i ’s,are independent Bernoulli randomvariables with E ½O ij j h i ¼h i E ij h i ’s are independent following a common distribution G ;8<:where G denotes a probability distribution over positive real numbers.Let us call the layers for O ij j h i and h i the ‘‘observ-able level’’and the ‘‘latent level’’of the hierarchical model,respectively.The latent level assumes common stochastic features for h i ’s,which provide additional information on shared characteristics of h i ’s that are not used to compute MLEs.By adding the latent level,estimators of h i ’s can ‘‘borrow strength’’from other units (e.g.,families)by com-bining the information on each individual unit with that on the common characteristics of h i ’s.For the distribution G of h i ’s,we propose the use of a (nonparametric)discrete distribution with K levels of fa-milial relative risk f /k ;k ¼1;2;...;K g and their associ-ated probabilities f p k g .While G can be a (parametric)continuous distribution such as gamma or lognormal distri-butions,the nonparametric G has an advantage in its flex-ible shape,determined by the data.Maximum likelihood estimation of the nonparametric G has been discussed by a number of authors (7–9).To compute the MLE of G ,we used the C.A.MAN program (Computer Assisted Mixture ANalysis)of Bo ¨hning et al.(10)and their freeware (11).Once the MLE of G is computed,the empirical Bayes esti-mate of h i is given by the posterior mean of h i with the MLE f ˆ/kg ;f p ˆk g ;and K ˆ:ˆh i ¼P K ˆk ¼1ˆ/k p ˆk L ðo i ;ˆ/k ÞP K ˆk ¼1pˆk L ðo i ;ˆ/k Þ;where L ðo i ;ˆ/kÞis the probability of observing the realiza-tion vector o i ¼ðo i 1;o i 2;...Þgiven /k ¼ˆ/k :Note that ˆh i is of the form of a weighted average of f ˆ/kg :APPLICATION TO AN EPIDEMIOLOGICINVESTIGATION OF BREAST CANCER ETIOLOGYAs an example,we apply the proposed familial risk es-timates to a large,population-based case-control study ofbreast cancer.Two main points are illustrated.First,the empirical Bayes estimates of familial relative risk are asso-ciated with case-control status more strongly than other summary measures of family history,including Family His-tory Scores.Second,these estimates detect an effect modi-fication of an environmental risk factor according to the level of familial relative risk more clearly than do other summary measures.Collaborative Breast Cancer Study IIThe data used in this illustration were derived from the Collaborative Breast Cancer Study II (CBCS II);the CBCS II study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of the participating institutions (12,13).Briefly,CBCS II was a case-control study of breast cancer in which cases were female residents of Wisconsin,Massachusetts (excluding metropolitan Boston),and New Hampshire with a new diagnosis of invasive breast cancer reported to each state’s cancer registry from January 1992through December 1994and aged 50–79years at the time of diagnosis.Of the 6,839eligible cases,5,685completed the standardized telephone interview (83percent).Community controls were randomly selected in each state by using two sampling frames:those 50–64years of age were selected from lists of licensed drivers,and those 65–79years of age were chosen from rosters of Medicare beneficiaries.The controls were selected at random within age strata to yield an age distri-bution similar to that of the cases within each state.Of the 7,655potential controls,5,951completed the telephone interview (78percent).A 40-minute telephone interview elicited information on the number of sisters and daughters for each participant,their current ages,and the age of their mother.If these fe-male relatives were deceased,the interview inquired about their age at death.Participants were asked whether these first-degree female relatives were ever diagnosed with can-cer (including breast cancer)and,if so,the type of cancer and age at diagnosis.The interview also covered reproduc-tive history,physical activity,selected dietary items,alcohol consumption and tobacco use,use of exogenous hormones,body height and weight,personal medical history,and de-mographic factors.Familial Relative Risk Estimates 699Am J Epidemiol 2006;164:697–705at :: on November 11, 2014/Downloaded fromEmpirical Bayes estimates of familial relative risk of breast cancerUsing the first-degree female family history data col-lected in CBCS II,we estimated familial relative risk lev-els of breast cancer by using the empirical Bayes method.For each first-degree female family member,we calculated her person-years at risk of breast cancer incidence stratify-ing by 5-year age segments from birth to the earlier occur-rence of death or the reference date of her family’s enrolled subject.Reference dates for study subjects were defined as the date of diagnosis for breast cancer cases and,for con-trols,the date randomly sampled from the dates of diagnosis among cases within the same 5-year age stratum (on aver-age,1year prior to interview).We then multiplied each person-time segment by the corresponding age-specific ref-erence rate of breast cancer incidence among White females taken from the data of the Surveillance,Epidemiology,and End Results Program registry (14).Summing the products of the above multiplication for each family member yielded each participant’s expected risk E ij of developing breast cancer.Since it is reasonable to assume the rare disease condition for breast cancer,we were able to approximate the model byO i ð¼Pj O ij Þ’s given h i ’s,are independent Poisson random variables with E ½O i j h i ¼h i P j E ijh i’s are independent following a common nonparametric discrete distribution G :8>><>>:We fitted this model by using the vertex exchange algo-rithm with the Newton-Raphson full-optimization step-length procedure in the C.A.MAN program (UNIX version)(10,11).The initial parameter grid was chosen as 10equally spaced points between a relative risk of 0.1and 5.0.The algorithm was stopped based on the maximum directional derivative with an accuracy level of 0.00001.The C.A.MANprogram identified seven grid points (Kˆ¼7)with positive support,which was then refined with the program’s EM algorithm.The resulting nonparametric MLE of G is shown in figure 1.Three of the seven points were very close to each other around a relative risk of 2.6because the EM algo-rithm was stopped by any practical convergence criterion (10):it stopped at the 806th step.However,this does not have any important consequences,as evident from several examples in the paper that described the C.A.MAN pro-gram in detail (10).Specifically,we can interpret figure 1as showing five relative risk clusters,instead of seven,andFIGURE 1.Nonparametric maximum likelihood estimates of the familial relative risk distribution of breast cancer in the Collaborative Breast Cancer Study II (Wisconsin;Massachusetts,excluding metropolitan Boston;and New Hampshire,1992–1994).700Yasui et al.Am J Epidemiol 2006;164:697–705at :: on November 11, 2014/Downloaded fromFIGURE 2.Empirical Bayes familial relative risk estimates of breast cancer for participants in the Collaborative Breast Cancer Study II (Wisconsin;Massachusetts,excluding metropolitan Boston;and New Hampshire,1992–1994)according to the expected number of affected familymembers.FIGURE 3.Family History Scores of breast cancer for participants in the Collaborative Breast Cancer Study II (Wisconsin;Massachusetts,excluding metropolitan Boston;and New Hampshire,1992–1994)according to the expected number of affected family members.Familial Relative Risk Estimates 701Am J Epidemiol 2006;164:697–705at :: on November 11, 2014/Downloaded fromthe numerical values of the empirical Bayes estimates f ˆhi g would have changed negligibly if the algorithm had run for a longer time.With this nonparametric MLE of G ,the empirical Bayesestimate ˆhi of the familial relative risk level for the i th participant was calculated by the posterior-mean equation.Figure 2displays the empirical Bayes familial relative risk estimates f ˆh i g according to the expected counts f P j E ij g of breast cancer cases in the families.The empirical Bayes familial relative risk estimates are lower for families with larger expected counts for a given observed count of affected family members,P j O ij :This is sensible because,for a given observed count of affected family members,P j O ij ;true familial relative risk should tend to be lower with a larger expected count of affected family members.For CBCS II participants with no family history of breast cancer ðP j O ij ¼0Þ;the empirical Bayes estimates are all less than 1.0.To contrast with the empirical Bayes estimates,the Family History Score values were plotted (figure 3).Recall that Family History Scores are indicators of statistical signifi-cance,not estimates of familial relative risk.Very small dif-ferences in the expected count of affected family members,Pj E ij ;can lead a range of observed counts of affected fam-ily members,P j O ij ;to the same Family History Score;for example,a Family History Score of 6can arise from fam-ilies with ðPj O ij ;P j E ij Þ¼(1,0.03),(2,0.10),(3,0.22),and (4,0.37).Extremely large Family History Score values were observed among the families with the smallest ex-pected counts.These features of Family History Scores are clearly unsuitable for use as estimates of familial relative risk levels.Main effects of family history on disease riskWe examined the degree of association between the case-control status of the CBCS II participants and their familial relative risk estimates to assess the strength of evidence for familial aggregation.We fitted a conditional logistic regres-sion model,conditioned on age group and US state (corre-sponding to the study design),to the case-control data of theTABLE 1.Model deviance and odds ratio estimates with 95%confidence intervals from conditional logistic regression analyses of Collaborative Breast Cancer Study II data (Wisconsin;Massachusetts,excluding metropolitan Boston;and New Hampshire,1992–1994)using various summary measures of familial risk of breast cancer as covariatesSummary measures of familial riskdfUnadjusted *Adjusted y Deviance explainedOdds ratio estimate95%confidenceintervalDeviance explainedOdds ratio estimate95%confidenceintervalFamily historyindicator 1111.5113.6No 1.00 1.00Yes1.731.56,1.92 1.791.60,1.99Observed count(continuous)1116.1 1.591.46,1.73119.8 1.631.49,1.78Observed count 4120.2122.60 1.00 1.001 1.67 1.50,1.87 1.71 1.53,1.922 1.99 1.49,2.66 2.18 1.61,2.963 5.40 2.09,13.93 5.34 2.05,13.9144.260.49,37.07 4.380.50,38.44Family History Score(continuous)187.8 1.141.11,1.1891.5 1.161.12,1.20Family History Score 4118.6118.7<0 1.00 1.00[0,1.305)z 1.42 1.17,1.72 1.54 1.26,1.87[1.305,1.938)z 1.78 1.47,2.16 1.87 1.53,2.28[1.938,2.910)z 1.81 1.49,2.19 1.75 1.43,2.15 2.910z 1.981.63,2.412.071.68,2.55Empirical Bayesestimates (continuous)1123.9 2.50 2.12,2.94122.0 2.58 2.18,3.06*Conditional logistic regression analysis conditional on age and state of residence.y Conditional logistic regression analysis conditional on age and state of residence,adjusting for age at menar-che,parity,age at first birth,age at menopause,body mass index,exogenous hormone use,alcohol consumption,and educational level.z Quartiles of positive Family History Scores.702Yasui et al.Am J Epidemiol 2006;164:697–705at :: on November 11, 2014/Downloaded fromCBCS II with their familial relative risk estimates as a sole covariate(unadjusted analysis)and with a set of adjustment variables(adjusted analysis).The adjustment variables in-cluded participants’age at menarche,parity,age atfirst birth (AFB),age at menopause,body mass index,exogenous hormone use,alcohol consumption,and educational level. Matching on age and the state of residence in the design of the CBCS II was accounted for in the analysis as strata of the conditional logistic regression.Table1presents the deviance explained and odds ratio estimates by each type of familial relative risk estimate in the unadjusted and adjusted condi-tional logistic regression analyses.The amount of deviance explained was used to measure the strength of association between disease status and familial relative risk estimates. Empirical Bayes estimates explained the largest amount of deviance in the unadjusted analysis and nearly the largest in the adjusted analysis using only1degree of freedom,close to the categorical observed counts that used4degrees of freedom.Family History Scores did not show as strong asso-ciations as empirical Bayes estimates,even when the scores were categorized intofive groups(negative and quartiles of positive scores).Thisfinding was consistent with our de-scription earlier that Family History Scores are not estimates of familial relative risk.The results shown in table1suggest that empirical Bayes estimates of familial relative risk pro-vide higher power in the assessment of the main effects of family history(familial aggregation)on disease risk than either the crude summaries or Family History Scores. Examination of an indication of gene-environmental interactionColditz et al.(15)and Egan et al.(16)reported that the effects of reproductive factors on breast cancer risk were modified by family history.Following this intriguingfind-ing,we assessed the effect modification of parity/AFB ef-fects according to familial relative risk levels.We created a covariate of parity and AFB by forming four categories of reproductive patterns:1)nulliparous,2)AFB before age 20years,3)AFB at age20–29years,and4)AFB at age 30years or ing the same conditional logistic re-gression models as those described above(unadjusted and adjusted analyses),we tested an interaction of the parity-AFB covariate with familial relative risk estimates.Three types of familial relative risk estimates were examined,and the results of the unadjusted analysis are shown in table2 (the adjusted analysis gave very similar odds ratio estimates, which are not shown in the tables).The top third of table2shows the odds ratio estimates and95percent confidence intervals for each category of the parity-AFB covariate by presence/absence of family history. The interaction of the parity-AFB covariate and family his-tory was not clear from the odds ratio estimates and was notstatistically significant:v2¼1.74with3degrees of freedom yielding p¼0.63in the unadjusted analysis(p¼0.78in the adjusted analysis).The middle third of this table shows the interaction of the parity-AFB covariate with whether the number of affectedfirst-degree female relatives was two or more.The odds ratio estimates suggest the presence of an effect modification,but the test for interaction was not statistically significant:v2¼4.60with3degrees of freedom yielding p¼0.20in the unadjusted analysis(p¼0.30in the adjusted analysis).The bottom third of table2shows the interaction of the parity-AFB covariate with whether the empirical Bayes es-timate of familial relative risk was1.75or more(i.e.,top 2percent).The odds ratio estimates suggest a pattern of the TABLE2.Odds ratio estimates with95%confidence intervals for parity/age atfirst birth according to various summary measures of familial risk or breast cancer from conditional logistic regression analyses of Collaborative Breast Cancer Study II data(Wisconsin;Massachusetts,excluding metropolitan Boston;and New Hampshire,1992–1994) Familial risk variable andage atfirst birth(years)Odds ratioestimate95%confidenceinterval Family history¼no<20 1.0020–29 1.51 1.26,1.8030 1.47 1.22,1.79Nulliparous 1.28 1.12,1.45 Family history¼yes<20 1.98 1.43,2.7420–29 2.01 1.42,2.8430 1.690.49,1.91Nulliparous 1.62 1.23,2.15Interaction test v2¼1.74(df¼3),p¼0.63<2affectedfirst-degreefemale relatives<20 1.0020–29 1.31 1.16,1.4730 1.58 1.22,1.88Nulliparous 1.57 1.12,1.842affectedfirst-degreefemale relatives<20 3.16 1.43,6.6220–29 1.80 1.42,2.4830 1.940.49,6.19Nulliparous 5.51 1.23,20.55Interaction test v2¼4.60(df¼3),p¼0.20 Empirical Bayesestimate<1.75<20 1.0020–29 1.31 1.17,1.4830 1.58 1.32,1.88Nulliparous 1.57 1.34,1.85 Empirical Bayesestimate 1.75<20 4.80 1.96,11.7220–29 1.59 1.12,2.2430 3.030.64,14.51Nulliparous 5.04 1.33,19.13Interaction test v2¼8.26(df¼3),p¼0.04Familial Relative Risk Estimates703Am J Epidemiol2006;164:697–705 at :: on November 11, 2014 / Downloaded from。

manifold-based method

manifold-based methodManifold-based methods refer to a class of algorithms used in machine learning and computer vision that aim to capture the underlying structure of high-dimensional data by modeling it as a low-dimensional manifold embedded in a higher dimensional space. These methods have gained popularity in recent years due to their ability to efficiently handle high-dimensional and complex data.One of the main benefits of manifold-based methods is that they can effectively deal with the curse of dimensionality. As the dimensionality of data increases, traditional algorithms may suffer from overfitting and become less efficient in capturing the underlying data structure. Manifold-based methods overcome this limitation by assuming that the data lies on a low-dimensional manifold, allowing for efficient representation and analysis of high-dimensional data.One widely used manifold-based method is manifold learning, which aims to discover the intrinsic geometric structure of the data manifold from the given high-dimensional data points. This approach is particularly useful when dealing with nonlinear and non-Gaussian data distributions. Common manifold learning algorithms include Isomap, Locally Linear Embedding (LLE), and t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE).Isomap is a technique that uses geodesic distances to construct a neighborhood graph, allowing for the estimation of the low-dimensional embedding. It preserves the global geometry of the data manifold and is often used for visualization tasks. LLE, on theother hand, focuses on preserving the local structure of the data manifold by reconstructing each data point as a linear combination of its neighbors. It generates a lower-dimensional representation that reflects the intrinsic structure of the data manifold.t-SNE, a more recently developed technique, is particularly useful for visualizing high-dimensional data. It uses a probabilistic approach to construct a lower-dimensional embedding that preserves pairwise similarities between data points. It is widely used in tasks such as visualizing word embeddings in natural language processing and clustering analysis.In addition to manifold learning, manifold-based methods also include other techniques such as manifold regularization and manifold alignment. Manifold regularization aims to incorporate the manifold structure into traditional learning algorithms by adding a regularization term to the objective function. This encourages the learned model to respect the manifold structure and improves generalization performance. Manifold alignment, on the other hand, aims to align multiple data manifolds in different domains by finding a common low-dimensional subspace that captures the shared structure among them.Overall, manifold-based methods provide powerful tools for analyzing high-dimensional and complex data. By leveraging the underlying manifold structure, these methods facilitate efficient representation, visualization, and analysis of data. They have been successfully applied in various domains, including computer vision, natural language processing, and bioinformatics, leading to improved performance in a wide range of machine learning tasks.。

[孙子兵法].The.Art.of.War.英文文字版