真菌检测鉴定通用引物-Fungal Primers

rDNA测序在酵母菌和丝状真菌鉴定中的临床应用评价

文章编号:1001-8689(2021)05-0432-05rDNA 测序在酵母菌和丝状真菌鉴定中的临床应用评价卢玲玲 单洪波 许育绚* 钟钰芳 丁进龙 王慧兰(杭州艾迪康医学检验中心有限公司 杭州 310000)摘要:目的 评价核糖体RNA(rDNA)测序,在临床酵母菌和丝状真菌鉴定中的应用价值。

方法 收集61株真菌(包括5株标准菌株,9株室间质评酵母菌,24株临床酵母菌,23株临床丝状真菌),通过设计通用引物ITS 和26S D1/D2,对61株真菌进行PCR 扩增并对扩增产物进行双向测序,将获得的所有序列在Seqman 中打开,选取ITS 和26S D1/D2正反向序列无重叠峰片段,进行BLAST 核酸序列比对。

结合Mycobank 真菌分类信息以获得菌株鉴定结果。

结果 61株真菌全部扩增成功,剔除杂峰后,所有菌株联合ITS 和26S D1/D2测序鉴定,100%菌种能鉴定到属或群,97.0%(32/33)的酵母菌与73.9%(17/23)的丝状真菌准确鉴定到种。

结论 经优化后的核糖体RNA(rDNA)测序,能准确快速的鉴定临床常见真菌与疑难菌。

关键词:核糖体;真菌;基因测序中图分类号:R446.5 文献标志码:AApplication and clinical evaluation for DNA sequencing analysis in identification ofyeasts and filamentous fungiLu Ling-ling, Shan Hong-bo, Xu Yu-xuan, Zhong Yu-fang, Ding Jin-long, and Wang Hui-lan(Hangzhou Adicon Clinical laboratory, Inc., Hangzhou 310000)Abstract Objective To evaluate the value of ribosomal RNA (rDNA) sequencing in the identification of clinical yeasts and filamentous fungi. Methods 61 fungi were collected (including five standard strains of yeasts, nine strains of yeasts of external quality assessment, 24 strains of clinically isolated yeasts, and 23 strains of filamentous fungi), PCR amplification and two direction gene sequencing were performed by the universal primer 1TS and 26S D1/D2 of fungal rDNA gene. All sequences obtained were opened in Seqman, the fragments without overlapping peaks were selected for blast nucleic acid sequence comparison and were combined with Mycobank to obtain the information of species identification. Results All the 61 strains were amplified successfully. After removing the heteropeaks, all the strains were identified by combining with ITS and 26S D1/D2 sequencing. 100% of the strains could be identified to genera or groups, and 97.0% (32/ 33) yeast and 73.9%(17/23) filamentous fungi could be identified to species accurately. Conclusion The optimized ribosomal RNA (rDNA) sequencing could accurately and rapidly identify clinical common and difficult fungi.Key words Ribosomal; Fungus; DNA sequencing收稿日期:2020-05-08作者简介:卢玲玲,女,生于1984年,硕士,研究方向为临床微生物检验,Email:****************。

真菌分离以及培养

一、(越南进境人参果炭疽病病原菌的分离鉴定2009年第3期植物检疫胡佳王卫芳¨)1.病原菌分离采用组织分离法,取病果病健交界果皮组织分离培养(马铃薯葡萄糖琼脂培养基[ PDA],25℃,1 2 h荧光与1 2 h黑暗循环交替),病菌纯化后保存备用。

2、病原菌培养特征和形态观测取病果病部组织进行徒手切片,显微观察分生孢子盘和分生孢子的形态特征;观察病菌的培养特性( P D A,2 5 o C,1 2 h荧l 2 h黑暗循环交替);观测分离物分生孢子的形态和大小;从培养7 d的菌落中挑取分生孢子团,配制成孢子悬浮液,采用载片悬滴法,观测附着孢的形态及大小。

3、病原菌1 8 S r D N A序列扩增与测定将纯化菌株置于P D A、2 5 o C、1 2 h荧~/1 2 h 黑暗循环交替条件下培养5 d ,挑取菌落边缘新鲜菌丝,采用常规C T A B法提取病原菌基因组D N A作扩增模板,进行P C R扩增。

所用引物为真菌1 8 S r D N A通用引物G e o A 2和G e o l 1 【9 J 。

反应体系为2 5 总体积,d d H 2 O 1 6 .3 7 5,1 0倍P C R缓冲液( 含Mg C 1 2 ) 2 .5 I x L,d N T P( 2 .5 mm o l /L) 2 L ,G e M1 ( 1 0 I ~ mo l /L ) 1 L ,G e o A 2 ( 1 0 l x m o L /L ) 1 LT a q ( 5 u /l x L ) 0 .1 2 5 L,模板 D N A 2 L 。

反应程序为9 4 ℃预变性2 m i n ,9 4 o C 4 5 s ,5 5 o C 4 5 s ,7 2 o C2 mi n ,3 0个循环,7 2 ~ C延伸1 0 mi n ,4 ℃保存。

P C R产物送上海英骏生物有限公司纯化测序。

测序结果与G e n B a n k数据库中的已知序列进行B L A S T比较。

菌种鉴定通用引物

菌种鉴定通用引物引言菌种鉴定是微生物学领域中的一项重要工作,它对于疾病诊断、环境监测和食品安全等方面具有重要意义。

菌种鉴定的关键是通过引物对目标微生物的DNA序列进行扩增和分析,从而确定其分类地位和种属鉴定。

本文将介绍菌种鉴定通用引物的原理和应用。

一、引物的选择原则菌种鉴定通用引物的选择需要考虑以下几个因素:1. 引物的特异性:引物应具有足够的特异性,只能扩增目标微生物的DNA序列,而不扩增其他非目标微生物的DNA序列。

2. 引物的保守性:引物应选择在目标微生物的DNA序列中高度保守的区域,以确保扩增的目标序列的一致性。

3. 引物的长度:引物的长度应适中,一般为18-30个碱基对,过长的引物可能导致扩增效率降低,而过短的引物可能导致特异性降低。

4. 引物的G+C含量:引物的G+C含量应适中,一般在40-60%之间,过低或过高的G+C含量可能影响扩增效率。

5. 引物的互补性:引物的两个端部应互补,以确保引物在目标DNA 序列上的结合和扩增。

二、常用的菌种鉴定通用引物1. 16S rRNA通用引物:16S rRNA序列是细菌和古菌中高度保守的基因序列,因此广泛用于细菌和古菌的鉴定。

常用的引物包括27F(5'-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3')和1492R(5'-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3')。

2. 18S rRNA通用引物:18S rRNA序列是真核生物中高度保守的基因序列,因此广泛用于真菌和原生动物的鉴定。

常用的引物包括ITS1(5'-TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3')和ITS4(5'-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3')。

3. 基因编码区通用引物:除了rRNA序列外,一些基因编码区的引物也被广泛应用于菌种鉴定。

例如,ITS区(内转录间隔区)是真菌常用的鉴定区域,常用的引物包括ITS1和ITS4。

真菌检测流程规范化要点

真菌检测流程规范化要点英文回答:Fungal testing is an important process in various industries, including agriculture, food production, healthcare, and environmental monitoring. Standardizing the fungal testing process is crucial to ensure accurate and reliable results. Here are some key points to consider in the standardization of fungal testing procedures:1. Sample collection: Proper sample collection is essential for accurate fungal testing. It is important to follow standardized protocols for sample collection, including using appropriate sampling tools, ensuring representative sampling, and minimizing contamination during the collection process. For example, in agricultural settings, soil samples can be collected using sterile sampling tools at multiple locations within a field to obtain a representative sample.2. Sample preparation: After sample collection, proper preparation is necessary to isolate and identify fungi. This may involve homogenization, dilution, and filtration of the sample, depending on the testing method. For instance, in food production, a food sample may need to be homogenized and diluted to obtain a suitable concentration for fungal testing.3. Testing methods: There are various methods available for fungal testing, such as culture-based methods, molecular techniques, and microscopic examination. Standardization involves selecting the appropriate method based on the purpose of testing, ensuring that the methodis validated and reliable, and following standardized protocols for performing the test. For example, in healthcare settings, molecular techniques like polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can be used to detect fungal pathogens in patient samples.4. Quality control: Standardization of fungal testing procedures requires implementing quality control measures to ensure the accuracy and reliability of results. This mayinclude using positive and negative controls, following quality assurance protocols, and participating in proficiency testing programs. For instance, in environmental monitoring, laboratories can participate in external proficiency testing programs to validate their fungal testing methods.5. Data interpretation and reporting: Standardization also involves consistent interpretation of test results and reporting formats. This ensures that the results are easily understandable and comparable across different laboratories or testing facilities. For example, in agriculture, the presence of specific fungal pathogens in a soil sample can be reported as a percentage of the total population.中文回答:真菌检测是农业、食品生产、医疗保健和环境监测等各个行业中的重要过程。

真菌检测鉴定通用引物Fung精编Primer精编

真菌检测鉴定通用引物F u n g精编P r i m e r精编Document number:WTT-LKK-GBB-08921-EIGG-22986ITS1: 5’-CCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3’ITS4:5’-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3’Tm 55℃NS17: CATGTCTAAGTTTAAGCAANS3: GCAAGTCTGGTGCCAGCAGCCNS4: CTTCCGTCAATTCCTTTAAGNS22: AATTAAGCAGACAAATCACTNS24: AAACCTTgTTACgACTTTTALR0R: 5’-GTACCCGCTGAACTTAAGC-3’LR3: 5’-CCGTGTTTCAAGACGGGLR3R: 5’-GTCTTGAAACACGGACC (complementary to RLR3R: GGTCCGTGTTTCAAGAC)LR5: 5’-TTAAAAAGCTCGTAGTTGAAC-3’LR7: 5’-TACTACCACCAAGATCTLR12: 5’-GACTTAGAGGCGTTCAGLr0R/LR5: Tm 50-52℃NL1: 5’-GCATATCAATAAGCGGAGGAAAAGNL1: 5′-TGCGTTGATTACGTCCCTGC (also called V9: TGCGTTGATTACGTCCCTGC)NL1: 5’-TGCTGGAGCCATGGATC-3NL2: 5’-CTCTCTTTTCAAAGTTCTTTTCATCTNL2: 5’-AACGGCTTCGACAACAGC-3NL2: 5’-CTTGTTCGCTATCGGTCTC (also NL2A: 5′-CTTGTTCGCTATCGGTCTC)NL2: 5’-TACTTGTTCGCTATCGGTCT-3'NL3: 5’-GAGACCGATAGCGAACAAG (also NL3A: 5’-GAGACCGATAGCGAACAAG)NL3: 5’-AGACCGATAGCGAACAAGTANL3: 5’-GCTGTTGTCGAAGCCGTT-3NL4: 5’(similar to RLR3R:5′-GGTCCGTGTTTCAAGAC)NL4: 5’-TAGATACATGGCGCAGTC-3Conserved primer sequences for PCR amplification and sequencing from nuclear ribosomal RNA ( lab, Duke UniversityOver the years, our lab has compiled a useful list of conserved primer sequences useful for amplification and sequencing of nuclear rDNA from most major groups of fungi (primarily Eumycota), as well as other eukaryotes. All of these primers were identified and tested by our own lab based on consensus between the published large and small subunit RNA sequences from fungi, plants and other eukaryotes; sources of other useful primer sequences from published literature are also indicated. Together, these primers span most of the nuclear rDNA coding region (see figures), permitting amplification of any desired region. Standard symbols are used for thefour primary nucleotides; variable positions are indicated as follows: P=A,G / Q=C,T / R=A,T / V=A,C /W=G,T. Primers ending with "R" represent the coding strand (same as RNA). All other primers are complementary to the coding strand. This information is provided freely and may be passed on to anyone who wants to use it.The nuclear-encoded ribosomal RNA genes (rDNA) of fungi exist as a multiple-copy gene family comprised of highly similar DNA sequences (typically from 8-12 kb each) arranged in a head-to-toe manner. Each repeat unit has coding regions for one major transcript (containing the primary rRNAs for a single ribosome), punctuated by one or more intergenic spacer (IGS) regions. In some groups (mostly basidiomcyetes and some ascomycetous yeasts), each repeat also has a separately transcribed coding region for 5S RNA whose position and direction of transcription may vay among groups. Several restriction sites for EcoRI and BglII are conserved in the rDNA of fungi. Nearly all basidiomycetes we've studied share an EcoRI site within the RNA gene along with a BglII site halfway into the LSU RNA sequence. Primers and LR7include these restriction sites, which makes them convenient for cloning.For those who aren't familiar with rDNA and fungal systematics, several excellent reviews are available on fungi (Hibbett, 1992) and generally for eukaryotes (Hillis and Dixon, 1991). See Gerbi (1986) for a general introduction to the molecular biology and evolution of rDNA in other eukaryotes. Another useful source of primer information may be found in Gargas & Depriest (1996) and at the Tom Bruns lab web siteSmall subunit RNA (SR) primers:PrimernameSequence (5'-->3')Position within S.cereviseae 17S RNA BMB-'A'GRATTACCGCGGCWGCTG580-558BMB-'B'CCGTCAATTCVTTTPAGTTT 1146-1127BMB-'C'ACGGGCGGTGTGTPC1638-1624BMB-BR CTTAAAGGAATTGACGGAA1130-1148BMB-CR GTACACACCGCCCGTCG1624-1640SR1R TACCTGGTTGATQCTGCCAGT1-21BMB = "universal" SSU primers developed by Lane et al., 1985 SR = primers developed by Vilgalys lab NS = primers described by White et al., 1990Large subunit RNA (25-28S) primer sequencesNote: most molecular systematics studies only utilizethe first 600-900 bases from the LSU gene, which includes three divergent domains (D1, D2, D3) that are among the most variable regions within the entire gene (much of the LSU is invariant even across widely divergent taxa). Most of the data in our Agaricales LSU database consists of the first 900 bases from the LSU gene (we typically amplify using primers + LR7, followed by sequencing using primers LR5, LR16, LR0R, and LR3R).Primer name Sequence (5'-->3')Positionwithin S.cereviseaerRNAcommentsCGCTGCGTTCTTCATCG51-35 RNA)containsEcoRIsite TCGATGAAGAACGCAGCG34-51 RNA)containsEcoRIsiteLR0R ACCCGCTGAACTTAAGC26-42 LR1GGTTGGTTTCTTTTCCT73-57 LR2TTTTCAAAGTTCTTTTC385-370 LR2R AAGAACTTTGAAAAGAG374-389Internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region primersThe ITS region is now perhaps the most widely sequenced DNA region in fungi. It has typically been most useful for molecular systematics at the species level, and even within species ., to identify geographic races). Because of its higher degree of variation than other genic regions of rDNA (SSU and LSU), variation amongindividual rDNA repeats can sometimes be observed within both the ITS and IGS regions. In addition to the standard ITS1+ITS4 primers used by most labs, everal taxon-specific primers have been described that allow selective amplification of fungal sequences ., see Gardes & Bruns 1993 paper describing amplification of basidiomycete ITS sequences from mycorrhiza samples).primernamesequence (5'->3')comments referenceITS1TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG White etal, 1990ITS2GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC (is similarto below)White et al, 1990ITS3GCATCGATGAAGAACGCAGC (is similar White etto below)al, 1990 ITS4TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC White etal, 1990 ITS5GGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG (is similarto SR6R)White etal, 1990 ITS1-F CTTGGTCATTTAGAGGAAGTAA Gardes &Bruns, 1993 ITS4-B CAGGAGACTTGTACACGGTCCAG Gardes &Bruns, 1993 CGCTGCGTTCTTCATCG VilgalyslabTCGATGAAGAACGCAGCG VilgalyslabSR6R AAGWAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG Vilgalyslab Intergenic spacer (IGS) primers (including 5S RNA primer sequences for basidiomycete fungi)The greatest amount sequence variation in rDNA exists within the IGS region (sometimes also known as the non-transcribed spacer or NTS region). The size of the IGS region may vary from 2 kb upwards. It is not unusual to find hypervariability for this region (necessitating cloning of individual repeat haplotypes). Severalpatterns of organization can be found in different groups of fungi:1.Most filamentous ascomycetes have a singleuninterrupted IGS region (between the end of the LSU and start of the next SSU sequence), which may vary in length from 2-5 kb or more. Amplification of the entire IGS region requires using primers anchored in the 3' end of the LSU gene ., LR12R) and 5' end ofthe SSU RNA gene ., invSR1R).2.In many ascomycetous yeasts and nearly allbasidiomycetes, the IGS also contains a singlecoding region for the 5S RNA gene, which divides the IGS into two smaller regions that may be more easily amplified using. Depending on the orientation andposition of the 5S RNA gene, the PCR may be used to sequentially amplify either aportion of theintergenic spacer region (IGS) beyond the largesubunit RNA coding region.REFERENCESBruns, T. D., R. Vilgalys, S. M. Barns, D. Gonzalez, D. S. Hibbett, D. J. Lane, L. Simon, S. Stickel, T. M. Szaro, W. G. Weisburg, and M. L. Sogin. 1992. Evolutionary relationships within the fungi: analyses of nuclear small subunit rRNA sequences. Molec. Phylog. Evol. 1: 231-241.Bruns, T. D., T. J. White, and J. W. Taylor. 1991. Fungal molecular systematics. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 22: 525-564.DePriest, P. T., and M. D. Been. 1992. Numerous group I introns with variable distributions in the ribosomal DNA of a lichen fungus. J. Mol. Biol. 228: 315-321. Elwood, H. J., G. J. Olsen, and M. L. Sogin. 1985. The small subunit ribosomal RNA gene sequences from the hypotrichous ciliates Oxytricha nova and Stylonychia pustula. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2: 399-410.Gardes, M., and T. D. Bruns. 1993. ITS primers with enhanced specificity for basidiomycetes - application to the identification of mycorrhizae and rusts. Mol. Ecol. 2: 113-118.Gargas, A., and . DePriest. 1996. A nomenclature for fungal PCR primers with examples from intron-containing SSU rDNA. Mycologia 88: 745-748Gargas, A., and . Taylor. 1992. Polymerase chainreaction (PCR) primers for amplifying and sequencing 18S rDNA from lichenized fungi. Mycologia 84: 589-592. Gerbi, S. A. 1986. Chapter 7 - Evolution of ribosomal DNA. Pp. 419-517 In: Molecular evolution, ed. McIntyre, R.Hibbett, D. S. 1991. Phylogenetic relationships of the Basidiomycete genus Lentinus: evidence from ribosomal RNA and morphology. . Thesis, Duke University, 1991. Hibbett, D. S. 1992. Ribosomal RNA and fungal systematics. Trans. Mycol. Soc. Jpn. 33: 533-556. Hibbett, D. S., and R. Vilgalys. 1991. Evolutionary relationships of Lentinus to the Polyporaceae: evidence from restriction analysis of enzymatically amplified ribosomal DNA. Mycologia 83: 425-439.Hibbett, D. S., and R. Vilgalys. 1993. Phylogenetic relationships of the Basidiomycete genus Lentinusinferred from molecular and morphological characters. Syst. Bot. 18: 409-433.Hillis, D. M., and M. T. Dixon. 1991. Ribosomal DNA: molecular evoluiton and phylogenetic inference. Quart. Rev. Biol. 66: 411-453.Hopple, J. S., Jr., and R. Vilgalys. 1994. Phylogenetic relationship among coprinoid taxa and allies based ondata from restriction site mapping of nuclear rDNA. Mycologia 86: 96-107.Lane, D. J., B. Pace, G. J. Olsen, D. A. Stahl, M. L. Sogin, and N. R. Pace. 1985. Rapid determination of 16S ribosomal RNA sequences for phylogenetic analyses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., U. S. A. 82: 6955-6959.Vilgalys, R., and D. Gonzalez. 1990. Organization of ribosomal DNA in the basidiomycete Thanatephorus praticola. Curr. Genet. 18: 277-280.Vilgalys, R., J. S. Hopple, Jr., and D. S. Hibbett. 1994. Phylogenetic implications of generic concepts in fungal taxonomy: The impact of molecular systematic studies. Mycologica Helvetica 6: 73-91.White, T. J., T. Bruns, S. Lee, and J. W. Taylor. 1990. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. Pp. 315-322 In: PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications, eds. Innis, M. A., D. H. Gelfand, J. J. Sninsky, and T. J. White. Academic Press, Inc., NewYork.W°。

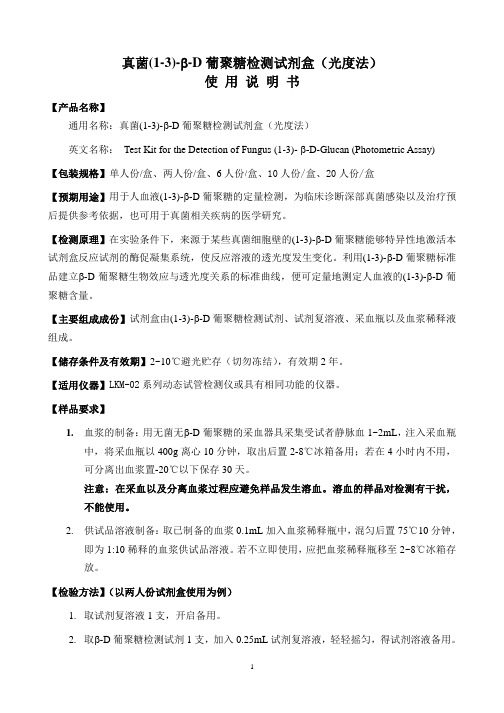

真菌检测试剂使用说明书

【产品名称】 通用名称:真菌(1-3)--D 葡聚糖检测试剂盒(光度法) 英文名称: Test Kit for the Detection of Fungus (1-3)- -D-Glucan (Photometric Assay) 【包装规格】单人份/盒、两人份/盒、6 人份/盒、10 人份/盒、20 人份/盒 【预期用途】用于人血液(1-3)--D 葡聚糖的定量检测,为临床诊断深部真菌感染以及治疗预 后提供参考依据,也可用于真菌相关疾病的医学研究。 【检测原理】在实验条件下,来源于某些真菌细胞壁的(1-3)--D 葡聚糖能够特异性地激活本 试剂盒反应试剂的酶促凝集系统,使反应溶液的透光度发生变化。利用(1-3)--D 葡聚糖标准 品建立-D 葡聚糖生物效应与透光度关系的标准曲线,便可定量地测定人血液的(1-3)--D 葡 聚糖含量。 【主要组成成份】试剂盒由(1-3)--D 葡聚糖检测试剂、试剂复溶液、采血瓶以及血浆稀释液 组成。 【储存条件及有效期】2~10℃避光贮存(切勿冻结) ,有效期 2 年。 【适用仪器】LKM-02 系列动态试管检测仪或具有相同功能的仪器。 【样品要求】 1. 血浆的制备: 用无菌无-D 葡聚糖的采血器具采集受试者静脉血 1~2mL, 注入采血瓶 中,将采血瓶以 400g 离心 10 分钟,取出后置 2-8℃冰箱备用;若在 4 小时内不用, 可分离出血浆置-20℃以下保存 30 天。 注意:在采血以及分离血浆过程应避免样品发生溶血。溶血的样品对检测有干扰, 不能使用。 2. 供试品溶液制备: 取已制备的血浆 0.1mL 加入血浆稀释瓶中, 混匀后置 75℃10 分钟, 即为 1:10 稀释的血浆供试品溶液。 若不立即使用, 应把血浆稀释瓶移至 2~8℃冰箱存 放。 【检验方法】 (以两人份试剂盒使用为例) 1. 取试剂复溶液 1 支,开启备用。 2. 取-D 葡聚糖检测试剂 1 支,加入 0.25mL 试剂复溶液,轻轻摇匀,得试剂溶液备用。

G GM试验--真菌检测

20Biblioteka To update the case-fatality rate (CFR) associated with invasive aspergillosis according to underlying conditions, site of infection, and antifungal therapy, data were systematically reviewed and pooled from clinical trials, cohort or case-control studies, and case series of ≥10 patients with definite or probable aspergillosis. Subjects were 1941 patients described in studies published after 1995 that provided sufficient outcome data; cases included were identified by MEDLINE and EMBASE searches. The main outcome measure was the CFR. Fifty of 222 studies met the inclusion criteria. The overall CFR was 58%, and the CFR was highest for bone marrow transplant recipients (86.7%). Amphotericin B deoxycholate and lipid formulations of amphotericin B failed to prevent death in one-half to two-thirds of patients. Mortality is high despite improvements in diagnosis and despite the advent of newer formulations of amphotericin B. Underlying patient conditions and the site of infection remain important prognostic factors.

真菌分子诊断技术应用的问题

真菌分子诊断技术应用的问题孙佳彬;曹国君【摘要】@@ 侵袭性真菌病(invasive fungal disease, IFD)常见于粒细胞减少患者、急性白血病化疗过程和造血干细胞或实体器官移植后患者.其发生率呈现逐年递增趋势,在某些特殊群体中有很高的死亡率,可达到90%以上[1],所以IFD的早期诊断与积极适宜的治疗至关重要[2].【期刊名称】《检验医学》【年(卷),期】2010(025)007【总页数】4页(P507-510)【关键词】真菌;感染;DNA扩增;临床诊断【作者】孙佳彬;曹国君【作者单位】上海交通大学医学院附属瑞金医院检验科,上海,200025;上海交通大学医学院附属瑞金医院检验科,上海,200025【正文语种】中文【中图分类】R446.5侵袭性真菌病(invasive fungal disease,IFD)常见于粒细胞减少患者、急性白血病化疗过程和造血干细胞或实体器官移植后患者。

其发生率呈现逐年递增趋势,在某些特殊群体中有很高的死亡率,可达到90%以上[1],所以IFD的早期诊断与积极适宜的治疗至关重要[2]。

事实上,目前临床上可利用的真菌感染相关诊断方法十分有限。

传统的培养法与组织病理学诊断被认为是“金标准”,却由于培养法的不灵敏和耗时,加上病理分析需创伤性采样等原因,使得利用病原体抗原血症与临床影像学相结合来提高临床的IFD早期诊断并指导治疗,已经成为不争的事实[3],从而大大地减少其死亡率。

真菌抗原血症的检测利用的是免疫学原理,其不可能检测到大量的真菌病原体,因其特异性的困惑导致假阳性与假阴性的报告屡见不鲜[4]。

聚合酶链反应(PCR)具有的基本特征可以克服上述提及的相关困惑,且又不缺乏有关建立PCR检测真菌分析用的基因信息。

然而,看似呈“呼之欲出”事态的真菌PCR却在目前的临床实验室检验中止步不前。

纵观大量相关文献报道,将其原因分析归纳有助于相关者们的借鉴。

一、待检标本中真菌DNA的提取PCR技术以其敏感(1个 DNA拷贝经 PCR扩增周期可放大为106)被广泛接受与应用,但是PCR前的DNA提取和靶基因的浓缩所起的重要影响作用已深入人心。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

ITS1: 5’-CCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3’ITS4:5’-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3’ Tm 55℃NS17: CATGTCTAAGTTTAAGCAANS3: GCAAGTCTGGTGCCAGCAGCCNS4: CTTCCGTCAATTCCTTTAAGNS22: AATTAAGCAGACAAATCACTNS24: AAACCTTgTTACgACTTTTALR0R: 5’-GTACCCGCTGAACTTAAGC-3’LR3: 5’-CCGTGTTTCAAGACGGGLR3R: 5’-GTCTTGAAACACGGACC (complementary to RLR3R: GGTCCGTGTTTCAAGAC)LR5: 5’-TTAAAAAGCTCGTAGTTGAAC-3’LR7: 5’-TACTACCACCAAGATCTLR12: 5’-GACTTAGAGGCGTTCAGLr0R/LR5: Tm 50-52℃NL1: 5’-GCATATCAATAAGCGGAGGAAAAGNL1: 5′-TGCGTTGATTACGTCCCTGC (also called V9: TGCGTTGATTACGTCCCTGC) NL1: 5’-TGCTGGAGCCATGGATC-3NL2: 5’-CTCTCTTTTCAAAGTTCTTTTCATCTNL2: 5’-AACGGCTTCGACAACAGC-3NL2: 5’-CTTGTTCGCTATCGGTCTC (also NL2A: 5′-CTTGTTCGCTATCGGTCTC)NL2: 5’-TACTTGTTCGCTATCGGTCT-3'NL3: 5’-GAGACCGATAGCGAACAAG (also NL3A: 5’-GAGACCGATAGCGAACAAG)NL3: 5’-AGACCGATAGCGAACAAGTANL3: 5’NL4: 5’-GGTCCGTGTTTCAAGACGG (similar to RLR3R:5′-GGTCCGTGTTTCAAGAC) NL4: 5’-TAGATACATGGCGCAGTC-3Conserved primer sequences for PCR amplification and sequencing from nuclear ribosomal RNA (/fungi/mycolab/primers.htm)Vilgalys lab, Duke UniversityOver the years, our lab has compiled a useful list of conserved primer sequences useful for amplification and sequencing of nuclear rDNA from most major groups of fungi (primarily Eumycota), as well as other eukaryotes. All of these primers were identified and tested by our own lab based on consensus between the published large and small subunit RNA sequences from fungi, plants and other eukaryotes; sources of other useful primer sequences from published literature are also indicated. Together, these primers span most of the nuclear rDNA coding region (see figures), permitting amplification of any desired region. Standard symbols are used for the four primary nucleotides; variable positions are indicated as follows: P=A,G / Q=C,T / R=A,T /V=A,C / W=G,T. Primers ending with "R" represent the coding strand (same as RNA). All other primers are complementary to the coding strand. This information is provided freely and may be passed on to anyone who wants to use it.The nuclear-encoded ribosomal RNA genes (rDNA) of fungi exist as a multiple-copy gene family comprised of highly similar DNA sequences (typically from 8-12 kb each) arranged in ahead-to-toe manner. Each repeat unit has coding regions for one major transcript (containing the primary rRNAs for a single ribosome), punctuated by one or more intergenic spacer (IGS) regions. In some groups (mostly basidiomcyetes and some ascomycetous yeasts), each repeat also has a separately transcribed coding region for 5S RNA whose position and direction of transcription may vay among groups. Several restriction sites for EcoRI and BglII are conserved in the rDNA of fungi. Nearly all basidiomycetes we've studied share an EcoRI site within the 5.8S RNA gene along with a BglII site halfway into the LSU RNA sequence. Primers 5.8SR and LR7 include these restriction sites, which makes them convenient for cloning.For those who aren't familiar with rDNA and fungal systematics, several excellent reviews are available on fungi (Hibbett, 1992) and generally for eukaryotes (Hillis and Dixon, 1991). See Gerbi (1986) for a general introduction to the molecular biology and evolution of rDNA in other eukaryotes. Another useful source of primer information may be found in Gargas & Depriest (1996) and at the Tom Bruns lab web site /boletus/boletus.html.Small subunit RNA (SR) primers:Primer name Sequence (5'-->3')Position within S. cereviseae 17S RNA BMB-'A' GRATTACCGCGGCWGCTG 580-558BMB-'B' CCGTCAATTCVTTTPAGTTT 1146-1127BMB-'C' ACGGGCGGTGTGTPC 1638-1624BMB-BR CTTAAAGGAATTGACGGAA 1130-1148BMB-CR GTACACACCGCCCGTCG 1624-1640SR1R TACCTGGTTGATQCTGCCAGT 1-21SR1 ATTACCGCGGCTGCT 578-564SR2 CGGCCATGCACCACC 1277-1263SR3 GAAAGTTGATAGGGCT 318-302SR4 AAACCAACAAAATAGAA 838-820SR5 GTGCCCTTCCGTCAATT 1146-1130SR6 TGTTACGACTTTTACTT 1760-1744SR6R AAGWAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG 1744-1763SR7 GTTCAACTACGAGCTTTTTAA 617-637SR7R AGTTAAAAAGCTCGTAGTTG 637-617SR8R GAACCAGGACTTTTACCTT 732-749SR9R QAGAGGTGAAATTCT 896-910SR10R TTTGACTCAACACGGG 1181-1196NS1 GTAGTCATATGCTTGTCTCNS2 GGCTGCTGGCACCAGACTTGCNS3 GCAAGTCTGGTGCCAGCAGCCNS4 CTTCCGTCAATTCCTTTAAG (similar to BMB-B)NS5 AACTTAAAGGAATTGACGGAAG (is similar to BMB-BR)NS6 GCATCACAGACCTGTTATTGCCTCNS7 GAGGCAATAACAGGTCTGTGATGCNS8 TCCGCAGGTTCACCTACGGASR = primers developed by Vilgalys labNS = primers described by White et al., 1990Large subunit RNA (25-28S) primer sequencesNote: most molecular systematics studies only utilizethe first 600-900 bases from the LSU gene, which includes three divergent domains (D1, D2, D3) that are among the most variable regions within the entire gene (much of the LSU is invariant even across widely divergent taxa). Most ofthe data in our Agaricales LSU database consists of the first 900 bases from the LSU gene (we typically amplify using primers 5.8SR + LR7, followed by sequencing using primers LR5, LR16,LR0R, and LR3R).Primer name Sequence (5'-->3')Position within S. cereviseae rRNA comments5.8S CGCTGCGTTCTTCATCG 51-35 (5.8S RNA) contains EcoRI site 5.8SR TCGATGAAGAACGCAGCG 34-51 (5.8S RNA) contains EcoRI site LR0R ACCCGCTGAACTTAAGC 26-42LR1 GGTTGGTTTCTTTTCCT 73-57LR2 TTTTCAAAGTTCTTTTC 385-370LR2R AAGAACTTTGAAAAGAG 374-389LR3 CCGTGTTTCAAGACGGG 651-635LR3R GTCTTGAAACACGGACC 638-654LR4 ACCAGAGTTTCCTCTGG 854-838LR5 TCCTGAGGGAAACTTCG 964-948LR6 CGCCAGTTCTGCTTACC 1141-1125LR7 TACTACCACCAAGATCT 1448-1432 contains BglII site LR7R GCAGATCTTGGTGGTAG 1430-1446 contains BglII site LR8 CACCTTGGAGACCTGCT 1861-1845LR8R AGCAGGTCTCCAAGGTG 1845-1861LR9 AGAGCACTGGGCAGAAA 2204-2188LR10 AGTCAAGCTCAACAGGG 2420-2404LR10R GACCCTGTTGAGCTTGA 2402-2418LR11 GCCAGTTATCCCTGTGGTAA 2821-2802LR12 GACTTAGAGGCGTTCAG 3124-3106LR12R CTGAACGCCTCTAAGTCAGAA 3106-3126LR13 CGTAACAACAAGGCTACT 3357-3340LR14 AGCCAAACTCCCCACCTG 2616-2599LR15 TAAATTACAACTCGGAC 154-138LR16 TTCCACCCAAACACTCG 1081-1065LR17R TAACCTATTCTCAAACTT 1033-1050LR20R GTGAGACAGGTTAGTTTTACCCT 2959-2982LR21 ACTTCAAGCGTTTCCCTTT 424-393LR22 CCTCACGGTACTTGTTCGCT 364-344Internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region primersThe ITS region is now perhaps the most widely sequenced DNA region in fungi. It has typically been most useful for molecular systematics at the species level, and even within species (e.g., to identify geographic races). Because of its higher degree of variation than other genic regions of rDNA (SSU and LSU), variation among individual rDNA repeats can sometimes be observed within both the ITS and IGS regions. In addition to the standard ITS1+ITS4 primers used by most labs, everal taxon-specific primers have been described that allow selective amplification of fungal sequences (e.g., see Gardes & Bruns 1993 paper describing amplification of basidiomycete ITS sequences from mycorrhiza samples).primer name sequence (5'->3')comments referenceITS1 TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG White et al, 1990ITS2 GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC (is similar to 5.8S below) White et al, 1990ITS3 GCATCGATGAAGAACGCAGC (is similar to 5.8SR below) White et al, 1990ITS4 TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC White et al, 1990ITS5 GGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG (is similar to SR6R) White et al, 1990ITS1-F CTTGGTCATTTAGAGGAAGTAA Gardes & Bruns, 1993 ITS4-B CAGGAGACTTGTACACGGTCCAG Gardes & Bruns, 1993 5.8S CGCTGCGTTCTTCATCG Vilgalys lab5.8SR TCGATGAAGAACGCAGCG Vilgalys labSR6R AAGWAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG Vilgalys labIntergenic spacer (IGS) primers (including 5S RNA primer sequences for basidiomycete fungi)The greatest amount sequence variation in rDNA exists within the IGS region (sometimes also known as the non-transcribed spacer or NTS region). The size of the IGS region may vary from 2 kb upwards. It is not unusual to find hypervariability for this region (necessitating cloning ofindividual repeat haplotypes). Several patterns of organization can be found in different groups of fungi:1. Most filamentous ascomycetes have a single uninterrupted IGS region (between the endof the LSU and start of the next SSU sequence), which may vary in length from 2-5 kb or more. Amplification of the entire IGS region requires using primers anchored in the 3' end of the LSU gene (e.g., LR12R) and 5' end of the SSU RNA gene (e.g., invSR1R).2. In many ascomycetous yeasts and nearly all basidiomycetes, the IGS also contains asingle coding region for the 5S RNA gene, which divides the IGS into two smaller regions that may be more easily amplified using. Depending on the orientation and position of the 5S RNA gene, the PCR may be used to sequentially amplify either aportion of theintergenic spacer region (IGS) beyond the large subunit RNA coding region.REFERENCESBruns, T. D., R. Vilgalys, S. M. Barns, D. Gonzalez, D. S. Hibbett, D. J. Lane, L. Simon, S. Stickel, T. M. Szaro, W. G. Weisburg, and M. L. Sogin. 1992. Evolutionary relationships within the fungi: analyses of nuclear small subunit rRNA sequences. Molec. Phylog. Evol. 1: 231-241.Bruns, T. D., T. J. White, and J. W. Taylor. 1991. Fungal molecular systematics. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 22: 525-564.DePriest, P. T., and M. D. Been. 1992. Numerous group I introns with variable distributions in the ribosomal DNA of a lichen fungus. J. Mol. Biol. 228: 315-321.Elwood, H. J., G. J. Olsen, and M. L. Sogin. 1985. The small subunit ribosomal RNA gene sequences from the hypotrichous ciliates Oxytricha nova and Stylonychia pustula. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2: 399-410.Gardes, M., and T. D. Bruns. 1993. ITS primers with enhanced specificity for basidiomycetes - application to the identification of mycorrhizae and rusts. Mol. Ecol. 2: 113-118.Gargas, A., and P.T. DePriest. 1996. A nomenclature for fungal PCR primers with examples from intron-containing SSU rDNA.Mycologia 88: 745-748Gargas, A., and J.W. Taylor. 1992. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers for amplifying and sequencing 18S rDNA fromlichenized fungi. Mycologia 84: 589-592.Gerbi, S. A. 1986. Chapter 7 - Evolution of ribosomal DNA. Pp. 419-517 In: Molecular evolution, ed. McIntyre, R.Hibbett, D. S. 1991. Phylogenetic relationships of the Basidiomycete genus Lentinus: evidence from ribosomal RNA and morphology. Ph.D. Thesis, Duke University, 1991.Hibbett, D. S. 1992. Ribosomal RNA and fungal systematics. Trans. Mycol. Soc. Jpn. 33: 533-556.Hibbett, D. S., and R. Vilgalys. 1991. Evolutionary relationships of Lentinus to the Polyporaceae: evidence from restriction analysis of enzymatically amplified ribosomal DNA. Mycologia 83:425-439.Hibbett, D. S., and R. Vilgalys. 1993. Phylogenetic relationships of the Basidiomycete genus Lentinus inferred from molecular and morphological characters. Syst. Bot. 18: 409-433.Hillis, D. M., and M. T. Dixon. 1991. Ribosomal DNA: molecular evoluiton and phylogenetic inference. Quart. Rev. Biol. 66: 411-453.Hopple, J. S., Jr., and R. Vilgalys. 1994. Phylogenetic relationship among coprinoid taxa and allies based on data from restriction site mapping of nuclear rDNA. Mycologia 86: 96-107.Lane, D. J., B. Pace, G. J. Olsen, D. A. Stahl, M. L. Sogin, and N. R. Pace. 1985. Rapid determination of 16S ribosomal RNA sequences for phylogenetic analyses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., U. S. A. 82: 6955-6959.Vilgalys, R., and D. Gonzalez. 1990. Organization of ribosomal DNA in the basidiomycete Thanatephorus praticola. Curr. Genet. 18: 277-280.Vilgalys, R., J. S. Hopple, Jr., and D. S. Hibbett. 1994. Phylogenetic implications of generic concepts in fungal taxonomy: The impact of molecular systematic studies. Mycologica Helvetica 6: 73-91.White, T. J., T. Bruns, S. Lee, and J. W. Taylor. 1990. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. Pp. 315-322 In: PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications, eds. Innis, M. A., D. H. Gelfand, J. J. Sninsky, and T. J. White. Academic Press, Inc., New York. ©W°。