Indirect Speech Acts

indirect speech act课件

4.Conversation cooperation principle。 会话合作的一般原则

Back

Examples - Indirect Speech Acts in use:

A . Mike and Ann are in the living room. Mike asks Ann whether she’d like to eat dinner in the living room or the kitchen. Ann replies: It’s cold in here. -----let’s eat dinner in the kitchen. B . The queen and her butler, James ,are in the drawing room. The window is open. The queen says: It’s cold in here. -----James, shut the window. C.Mike and Ann are in the greenhouse.Mike wonders why his orchids haven't bloomed.Ann replies:It's cold in here. -----The orchids aren't blooming.

“间接言语行为是通过实施另一种施事行

为的方式来间接地实施某一种施事行为”.

Indirect speech act

Secondary illocutionary act(Literal meaning) 次要施事行为 primary illocutionary act(Nonliteral meanign) 首要施事行为 For example: Could you pass the salt? 1.The secondary illocutionary act:The surface form of this utterance is an interrogative one. 2.The primary illocutionary act:In whether the hearer have ability to pass the salt, while expressing his intention which is a request.

Indirect Speech Acts

4. The conventional indirect speech act

• 六种间接指令(indirect directives) • 1、涉及听话人实施A的能力的句子。 Can you pass the salt? • 2、涉及说话人希望听话人实施A的句子。 I would like you to pass the salt. • 3、涉及听话人实施A的句子。 Will you pass the salt? • 4、涉及听话人实施A的意愿的句子。 Would you be willing to pass the salt?

• 通过另一种施事行为(次要施事行为 secondary illocutionary act)的方式来 间接地实施某一种施事行为(首要施 事行为primary illocutionary act)。 • eg.Can you pass the salt? S: 询问(interrogative): P:请求(request):

2. Indirect Speech Acts

• Terms • 字面语力(literal force):句子本身表达的言语 行为。 • 实事语力(illocutionary force):在字面语力的 基础上推导出来的语力,即间接语力。

• This kind of speech acts, "in which one illocutionary act is porformed indirectly by way of performing another" (Searle1995b:60),Searle calls indirect speech acts.

• 5、涉及实施A理由的 句子。 • It might help if you pass the salt. • 6、把上述形式中的一种嵌入到另一种中去,以及 在上述的一种形式中嵌入一种显性指令性施事动 词的句子。 • I hope you(2) won't mind (4)if I ask you (IV)if you could(1) pass the salt.

通过理解间接言语行为提高听力水平

通过理解间接言语行为提高听力水平1 间接言语行为间接言语行为理论( indirect speech act theory )是美国语言学家John Searle 在Austin 的言语行为理论的基础上提出来的。

根据塞尔的定义,间接言语行为就是通过一种言外行为来间接地执行另一种言外行为,即一句话里可以有两种言外行为,一种是能从字面上就精确表达了说话人的意图,另一种是除了字面上表达的意思外,还隐含着另一层意思。

换句话说,交际者在实施间接言语行为时往往不直接说出自己要表达的意思,而是凭借另外一种言语行为来间接地表达其真实意图[1]。

例如:(1) Could you pass me the salt?(2) He is coming. 这两个句子要表达的意思不能只按照字面意义和句子形式去理解说话人“询问”听话人是否具有做某事的能力或陈述一个事实,根据不同的语境和说话人的不同意图,这两个句子的所表达的意义远不止询问或告知,还可以是“请求”、“命令”或“警告”“威胁”“描述”。

由此可见,要理解会话含义仅靠字面意义是不够的,因此在听力中会给听者造成理解话语的障碍。

2 间接言语行为的分类2.1 规约性间接言语行为(conventional indirect speech acts)规约性间接言语行为是对“字面用意”做出一般性推断而得出的间接言语行为,它的间接言外之力在某种程度上已经固定在语言形式之中,听话者能很容易从语句的字面意思理解到其中的言外之意。

例如:(1)Could you be a little more quiet?(2)I 'd rather you didn 't do it any more.(3)I would appreciate if you could turn off the light.(4)Do you know what time it is?2.2 非规约性间接言语行为(non-conventional indirect speech acts)非规约性间接言语行为不是按习惯就可以推断出句子的言外之意,非规约性间接言语行为中说话者的话语意义与其所使用的语句的字面意思之间的联系较为复杂,而且很不固定, 说话者的话语意义要通过语境和双方共享的背景知识推断出来。

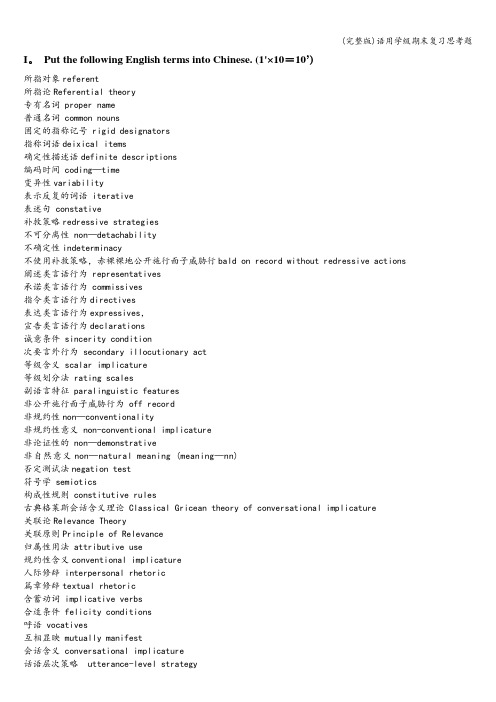

(完整版)语用学级期末复习思考题

I。

Put the following English terms into Chinese. (1'×10=10’)所指对象referent所指论Referential theory专有名词 proper name普通名词 common nouns固定的指称记号 rigid designators指称词语deixical items确定性描述语definite descriptions编码时间 coding—time变异性variability表示反复的词语 iterative表述句 constative补救策略redressive strategies不可分离性 non—detachability不确定性indeterminacy不使用补救策略,赤裸裸地公开施行面子威胁行bald on record without redressive actions 阐述类言语行为 representatives承诺类言语行为 commissives指令类言语行为directives表达类言语行为expressives,宣告类言语行为declarations诚意条件 sincerity condition次要言外行为 secondary illocutionary act等级含义 scalar implicature等级划分法 rating scales副语言特征 paralinguistic features非公开施行面子威胁行为 off record非规约性non—conventionality非规约性意义 non-conventional implicature非论证性的 non—demonstrative非自然意义non—natural meaning (meaning—nn)否定测试法negation test符号学 semiotics构成性规则 constitutive rules古典格莱斯会话含义理论 Classical Gricean theory of conversational implicature关联论Relevance Theory关联原则Principle of Relevance归属性用法 attributive use规约性含义conventional implicature人际修辞 interpersonal rhetoric篇章修辞textual rhetoric含蓄动词 implicative verbs合适条件 felicity conditions呼语 vocatives互相显映 mutually manifest会话含义 conversational implicature话语层次策略 utterance-level strategy积极面子positive face间接言语行为 indirect speech acts间接指令 indirect directives结语 upshots交际意图communicative intention可撤销性 cancellability可废弃性 defeasibility可推导性 calculability跨文化语用失误cross—cultural pragmatic failure跨文化语用学cross—cultural pragmatics命题内容条件 propositional content condition面子保全论 Face-saving Theory面子论 Face Theory面子威胁行为 Face Threatening Acts (FTAs)蔑视 flouting明示 ostensive明示-推理模式ostensive—inferential model摹状词理论Descriptions粘合程度 scale of cohesion篇章指示 discourse deixis前提 presupposition前提语 presupposition trigger强加的绝对级别absolute ranking of imposition确定谈话目的 establishing the purpose of the interaction确定言语事件的性质 establishing the nature of the speech event 确定性描述语 definite descriptions认知语用学 cognitive pragmatics上下文 co—text社会语用迁移sociopragmatic transfer社交语用失误 sociopragmatic failure施为句 performative省力原则 the principle of least effort实情动词 factive verbs适从向 direction of fit手势型用法 gestural usage首要言外行为 primary illocutionary act双重或数重语义模糊 pragmatic bivalence/ plurivalence顺应的动态性 dynamics of adaptability顺应性adaptability语境关系的顺应(contextual correlates of adaptability)、语言结构的顺应(structural objects of adaptability)、顺应的动态性(dynamics of adaptability)和顺应过程的意识程度(salience of the adaptation processes)。

Speech Act

2.3 承诺类(Commissives): 答应,保证

“The whole point of a commissive is to commit the speaker to a certain course of action” (姜望琪,2000) e.g. promise, covenant, contract, undertake, bind myself, give my word, am determined, intend, declare my intention, mean to, plan, purpose, propose to, shall, contemplate, envisage, engage, swear, guarantee, pledge my self, bet, vow, agree, consent, dedicate myself to, declare for, side with

2.5 行动类(Behabitives): 感谢,欢迎

3. Searle’s classifications

3.1 断言类 Assertives 或 阐述 Representatives 3.2 指令类 Directives: request, ask, urge, demand, command, order, advise, beg, invite 3.3 承诺类 Commissives 3.4 表达类 Expressive 3.5 宣告类 Declarations

Hale Waihona Puke 3.3 承诺类 Commissives

The illocutionary point in this class is to commit the speaker to some future course of action. e.g. verbs: promise, commit, pledge, vow, offer, refuse, guarantee, threaten, undertake…

indirect speech act

• 会话式假设的一个例子就是是/否问句,典型做法是诱导出反应,而不 / 是字面上的问答。 • 例如,如果你在街上趋前问人:“你知道时间吗?”人家就不会说“ 是”或“否”,她会告诉你现在是几点。 • 如果你问人家的是:“你知道今晚的电视演什么?”很可能他告诉你 的就是今晚的节目,而不是“是”或“否”。 • 进行会话式假设前,你要先想想你要的是什么反应。

4.6.1 What is an indirect speech act?

• Most of the world’s languages have three basic sentence types: 1) declarative 2) interrogative 3) imperative • The three major sentence types are typically associated with the three basic illocutionary forces(言外语势), namely, asserting/stating, asking/questioning, and ordering/requesting, respectively.

《英语语言学导论》(第四版)课件Chapter 7 Pragmatics

world; 3) the relationships between linguistic forms and the users of

Contents

1 Introduction to Pragmatics 2 Deixis and Reference

3 Speech Acts 4 Pragmatic Presupposition

5 The Cooperative Principle and Implicature

6

Apply PP to teaching in future Politeness

7.2.6 Social deixis

the encoding of social distinctions, or the use of deictic expressions to indicate social status of the interlocutors

● honorifics e.g. tu/vous (in French) du/sie (in German) nǐ/nín (in Chinese)

--- the addressees being audio-visually present during the utterances to be able to understand these expressions

e.g. I like that one, not this one.

7.2 Deixis and reference

言语行为理论-speech act theory

外语研究小窝

CONTENTS

Austin简介 文旭简介 最新语用学论文导读

(略)

1、约翰·朗肖·奥斯丁(John Langshaw Austin)

• 约翰·朗肖·奥斯丁(John Langshaw Austin 1911-1960)是牛津学派的重 要代表人物。他于1911年生于英国 的兰开斯特。1924年在施鲁兹伯利 公学攻读希腊、拉丁古典著作,后 入牛津大学贝里奥尔学院学习古典 学、语言学和哲学。1935年起在牛 津大学莫德林学院任教。第二次世 界大战期间,他曾在英国情报部队 服役。战后他重新回到牛津从事教 学活动,奥斯丁于1960年去世,年 仅48岁。

s言ta语te论or断de,sc能rib验e,证an真d w假ereeg:thuAsISveBr.ifiable.•

Perlocutionary act:言语带来的后果,即 听话者的行为

•

“performatives” were sentences that did not state a fact or describe a state, and were not verifiable(to perform an action,

2、Introduction To Its Proposers

• Austin

• John Searle

• 约翰·塞尔是当今世界最著名、最具影响 力的哲学家之一。他于1932年出生在美 国科罗拉多州丹佛市,1949-1952之间就 读于威斯康星大学,1955年获罗兹 (Rhodes)奖学金赴牛津大学学习,并 获哲学博士学位。他曾师从牛津日常语 言学派主要代表、言语行动理论的创建 者奥斯汀(J.L.Austin),深入研究语言分 析哲学。1959年返美,并一直在加州大 学伯克利分校任教,后当选美国人文科 学院院士。

indirect speech act课件

Six kinds of sentences about indirect directives (间接指令句)(Searle1979)

1,涉及听话人实施act能力的句子。 Can you pass the salt ? Have you got change for a dollar? 2,涉及说话人希望听话人实施act的句子。 I would like you to go now. I wish you wouldn’t do it. 3,涉及听话人实施act的句子。 Aren’t you going to eat your cereal? Won’t you stop making that noise soon?

4. But Y's sentence does not mean any of those four possibilities, so it is not a relevant response. 5. If the sentence meaning fails, there must be an additional speaker meaning. What is that additional speaker meaning? 6. X surely understands that if Y has been notified of his friend’s coming to his room, he is obliged to wait for that friend's arrival and join him for some time.

“间接言语行为是通过实施另一种施事行

为的方式来间接地实施某一种施事行为”.

Indirect speech act

Direct and Indirect Speech Acts in English

MASARYK UNIVERSITY IN BRNOFACULTY OF ARTSDEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND AMERICAN STUDIESDirect and Indirect Speech Acts in EnglishMajor Bachelor’s ThesisVeronika JustováSupervisor: Mgr. Jan Chovanec, Ph.D. Brno 2006I hereby declare that I have worked on this Bachelor Thesis independently, using only primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography.20th April 2006 in Brno:I wish to express many thanks to my supervisor, Mgr. Jan Chovanec, Ph.D., for his kind and valuable advice, help and support.CONTENTS INTRODUCTION (5)1. LANGUAGE, SPEECH ACTS AND PERFORMATIVES (6)1.1.E XPLICIT AND I MPLICIT P ERFORMATIVES (7)1.2.F ELICITY C ONDITIONS (9)2. THE LOCUTIONARY, ILLOCUTIONARY AND PERLOCUTIONARY ACTS (11)2.1.L OCUTIONARY A CTS (12)2.2.I LLOCUTIONARY A CTS (13)2.3.P ERLOCUTIONARY A CTS (17)3. INDIRECTNESS (17)3.1.T HE T HEORY OF I MPLICATURE, THE C OOPERATIVE P RINCIPLE AND M AXIMS (18)4. LIFE X 3 (21)4.1.D IRECT SPEECH A CTS A S A R EACTION TO D IRECT S PEECH A CTS (22)4.2.I NDIRECT S PEECH A S A R EACTION TO D IRECT S PEECH A CTS (24)4.3.D IRECT S PEECH A S A R EACTION TO I NDIRECT S PEECH A CTS (27)4.4.I NDIRECT S PEECH A S A R EACTION TO I NDIRECT S PEECH A CTS (30)4.5.D ATA E VALUATION (32)CONCLUSION (34)CZECH RÉSUMÉ (35)BIBLIOGRAPHY (36)APPENDIX (38)IntroductionThis thesis deals with the theory of speech acts and the issue of indirectness in English. It sums up and comments on theoretical definitions and assumptions concerning the theory of speech acts given by some linguists and language philosophers. This work further discusses the usage of speech acts in various conversational situations, putting the accent particularly on indirectness and its application in the language of drama.In the first three chapters, I am going to deal with the theoretical approach towards the speech acts. I will comment on the types of speech acts, I will explain how it is possible that the hearer successfully decodes a non-literal, implied message, what conditions must be met in order that the hearer succeeds in this process of decoding and I will suggest why people use indirectness in everyday communication.In the last chapter, I will then concentrate on indirectness in the discourse of drama. For my analysis, I have chosen the play Life x 3 by a contemporary French author Yasmina Reza whose pieces are often based rather on exchanges between the characters than on some kind of complicated plot.In Life x 3, I have identified four types of exchanges: direct speech acts motivated by direct speech acts, indirect speech acts motivated by direct speech acts, direct speech acts motivated by indirect speech acts and finally indirect speech acts motivated by indirect speech acts. They occur in various proportions, the most frequent being the direct-indirect exchanges and the least frequent being the indirect-direct exchanges.Grounded on empirical data, I have found out that the play is based rather on indirectness since there are 62 exchanges out of which at least one is indirect, the total number of exchanges being 89.Direct-direct, indirect-indirect and direct-indirect contributions are quite frequent throughout the play. It seems that the hearer in these exchanges accepts the strategy proposed by the speaker and chooses to pursue likewise, or in the case of direct-indirect exchanges, he decides to make his utterance more polite or evasive so that he does not offend the speaker. In direct-indirect exchanges, the hearer sometimes has more reasons to use indirectness (power, competing goals, desire to make his language more interesting).On the other hand, indirect-direct strategy is somehow dispreferred as, based on this play, directness after an indirect utterance may initiate an argument between the speakers.1. Language, Speech Acts and Performatives Language is an inseparable part of our everyday lives. It is the main tool used to transmit messages, to communicate ideas, thoughts and opinions. It situates us in the society we live in; it is a social affair which creates and further determines our position in all kinds of various social networks and institutions.In certain circumstances we are literally dependent on its appropriate usage and there are moments when we need to be understood quite correctly. Language is involved in nearly all fields of human activity and maybe that is why language and linguistic communication have become a widely discussed topic among linguists, lawyers, psychologists and philosophers.According to an American language philosopher J.R. Searle speaking a language is performing speech acts, acts such as making statements, giving commands, asking questions or making promises. Searle states that all linguistic communication involves linguistic (speech) acts. In other words, speech acts are the basic or minimal units of linguistic communication. (1976, 16) They are not mere artificial linguistic constructs as it may seem, their understanding together with the acquaintance of context in which they are performed are often essential for decoding the whole utterance and its proper meaning. The speech acts are used in standard quotidian exchanges as well as in jokes or drama for instance.The problem of speech acts was pioneered by another American language philosopher J.L. Austin. His observations were delivered at Harvard University in 1955 as the William James Lectures which were posthumously published in his famous book How to Do Things with Words. It is Austin who introduces basic terms and areas to study and distinguishes locutionary, illocutionary and perlocutionary acts. As Lyons puts it: Austin’s main purpose was to challenge the view that the only philosophically (and also linguistically) interesting function of language was that of making true or false statements.(Lyons, 173) Austin proves that there are undoubtedly more functionslanguage can exercise. The theory of speech acts thus comes to being and Austin’s research becomes a cornerstone for his followers.It is Austin who introduces basic terms and areas to study and he also comes up with a new category of utterances – the performatives.Performatives are historically the first speech acts to be examined within the theory of speech acts. Austin defines a performative as an utterance which contains a special type of verb (a performative verb) by force of which it performs an action. In other words, in using a performative, a person is not just saying something but is actually doing something (Wardhaugh: 1992: 283). Austin further states that a performative, unlike a constative, cannot be true or false (it can only be felicitous or infelicitous) and that it does not describe, report or constate anything. He also claims that from the grammatical point of view, a performative is a first person indicative active sentence in the simple present tense. This criterion is ambiguous though and that is why, in order to distinguish the performative use from other possible uses of first person indicative active pattern, Austin introduces a hereby test since he finds out that performative verbs only can collocate with this adverb.1. a. I hereby resign from the post of the President of the Czech Republic.b. I hereby get up at seven o’clock in the morning every day.While the first sentence would make sense under specific conditions, uttering of the second would be rather strange. From this it follows that (1a) is a performative, (1b) is not.Having defined performatives, Austin then draws a basic distinction between them. He distinguishes two general groups - explicit and implicit performatives.1.1. Explicit and Implicit PerformativesAn explicit performative is one in which the utterance inscription contains an expression that makes explicit what kind of act is being performed (Lyons, 1981: 175). An explicit performative includes a performative verb and mainly therefore, as Thomas (1995: 47) claims, it can be seen to be a mechanism which allows the speaker to remove any possibility of misunderstanding the force behind an utterance.2. a. I order you to leave.b. Will you leave?In the first example, the speaker utters a sentence with an imperative proposition and with the purpose to make the hearer leave. The speaker uses a performative verb and thus completely avoids any possible misunderstanding. The message is clear here.The second utterance (2b) is rather ambiguous without an appropriate context. It can be understood in two different ways: it can be either taken literally, as a yes/no question, or non-literally as an indirect request or even command to leave. The hearer can become confused and he does not always have to decode the speaker’s intention successfully. (2b) is an implicit or primary performative. Working on Lyon’s assumption, this is non-explicit, in terms of the definition given above, in that there is no expression in the utterance-inscription itself which makes explicit the fact that this is to be taken as a request rather than a yes/no question (Lyons, 1981: 176).The explicit and implicit versions are not equivalent. Uttering the explicit performative version of a command has much more serious impact than uttering the implicit version (Yule, 1996: 52). Thomas adds to this that people therefore often avoid using an explicit performative since in many circumstances it seems to imply an unequal power relationship or particular set of rights on the part of the speaker (1995: 48). This can be seen in the following examples:3. a. Speak. Who began this? On thy love, I charge thee. (Othello, 2.3.177)b. I dub thee knight.In (3a) Othello speaks to his ensign Iago and asks him who initiated a recent fight. Othello addresses Iago from the position of strength and power and he therefore uses the explicit performative ‘I charge thee’. Iago understands what is being communicated and carefully explains that he does not know who had started it.In (3b) the situation is different. In this example it is rather the particular set of rights on the part of the speaker which enable him to use an explicit performative. Dubbing was the ceremony whereby the candidate’s initiation into knighthood was completed. It could only be carried out by the king or any entitled seigneur who shall strike the candidate three times with the flax of the blade, first upon the left shoulder,next upon the right shoulder and finally upon the top of the head while saying I dub thee once.. I dub thee twice...I dub thee Knight.1The ceremony was completed when the knight received spurs and a belt as tokens of chivalry. Levinson (: 230) declares that ‘performative sentences achieve their corresponding actions because there are specific conventions linking the words to institutional procedures’. The institutional procedures are not always the same, they differ considerably in different historical periods and cultures (e.g. the institution of marriage in western and eastern societies). Austin states that it is also necessary for the procedure and the performative to be executed in appropriate circumstances in order to be successful.Shiffrin (1994: 51), commenting on Austin’s observations, adds: “The circumstances allowing an act are varied: they include the existence of ‘an accepted conventional procedure having a certain conventional effect’, the presence of ‘particular persons and circumstances’, ‘the correct and complete execution of a procedure’, and (when appropriate to the act) ‘certain thoughts, feelings, or intentions’.” These circumstances are more often called felicity conditions.1.2. Felicity ConditionsThe term of felicity conditions was proposed by Austin who defines them as follows (Austin, 1962: 14 – 15):A.There must exist an accepted conventional procedure having a certainconventional effect, that procedure to include the uttering of certain words bycertain persons in certain circumstances.B.The particular persons and circumstances in a given case must be appropriate forthe invocation of the particular procedure invoked.C.The procedure must be executed by all participants both correctly andcompletely.D.Where, as often, the procedure is designed for use by persons having certainthoughts or feelings, or for the inauguration of certain consequential conduct on the part of any participant, then a person participating in and so invoking theprocedure must intend so to conduct themselves, and further must actually soconduct themselves subsequently.1 </Ceremony/West/Chivalry.pdf >Linguistic literature concerning the theory of speech acts often deals with Austin’s example of marriage in connection with felicity conditions. Thomas for instance closely describes the institution of marriage and states that in western societies “this conventional procedure involves a man and a woman, who are not debarred from marrying for any reason, presenting themselves before an authorized person (minister of religion or registrar), in an authorized place (place of worship or registry place), at an approved time (certain days or times are excluded) accompanied by a minimum of two witnesses. They must go through a specified form of marriage: the marriage is not legal unless certain declarations are made and unless certain words have been spoken” (Thomas, 1995: 38). Only then are all the felicity conditions met and the act is considered valid.However, this procedure is often not universal; the customs vary throughout countries and cultures. In Islamic world for example, the ceremony of marriage is considerably different. The bride cannot act herself, she needs a wali (male relative) to represent her in concluding the marital contract as without his presence the marriage would be invalid and illegal. The declarations and words spoken are also culture specific and thus different from the formulas common in Europe.2For all that, there must exist a certain conventional procedure with appropriate circumstances and persons involved, it must be executed correctly and completely, the persons must have necessary thoughts, feelings and intentions and if consequent conduct is specified, then the relevant parties must do it. (Thomas, 1995: 37) Generally, only with these felicity conditions met the act is fully valid.The term of felicity conditions is still in use and it is not restricted only to performatives anymore. As Yule (Yule, 1996: 50) observes, felicity conditions cover expected or appropriate circumstances for the performance of a speech act to be recognized as intended. He then, working on originally Searle’s assumptions, proposes further classification of felicity conditions into five classes: general conditions, content conditions, preparatory conditions, sincerity conditions and essential conditions. According to Yule (Yule,1996:50), general conditions presuppose the participants’ knowledge of the language being used and his non-playacting, content conditions concern the appropriate content of an utterance, preparatory conditions2 </articles/marriage_ceremony_basics.html>deal with differences of various illocutionary acts (e.g. those of promising or warning), sincerity conditions count with speaker’s intention to carry out a certain act and essential conditions ‘combine with a specification of what must be in the utterance content, the context, and the speaker’s intentions, in order for a specific act to be appropriately (felicitously) performed’.In connection with felicity conditions as well, Austin later realizes that the category of performatives and constatives is not sufficient and thus, in an attempt to replace it by a general theory of speech acts, he ‘isolates three basic senses in which in saying something one is doing something, and hence three kinds of acts that are simultaneously performed’ (Levinson: 236): the locutionary, illocutioanary and perlocutionary acts.2. The Locutionary, Illocutionary and Perlocutionary Acts The locutionary, illocutionary and perlocutionary acts are, in fact, three basic components with the help of which a speech act is formed. Leech (Leech, 1983: 199) briefly defines them like this:locutionary act: performing an act of saying something illocutionary act: performing an act in saying something perlocutionary act: performing an act by saying somethingThe locutionary act can be viewed as a mere uttering of some words in certain language, while the illocutionary and perlocutionary acts convey a more complicated message for the hearer. An illocutionary act communicates the speaker’s intentions behind the locution and a perlocutionary act reveals the effect the speaker wants to exercise over the hearer.This can be demonstrated on a simple example:4. Would you close the door, please?The surface form, and also the locutionary act, of this utterance is a question with a clear content (Close the door.) The illocutionary act conveys a request from the part of the speaker and the perlocutionary act expresses the speaker’s desire that the hearer should go and close the door.But the individual elements cannot be always separated that easily. Bach and Harnish say that they are intimately related in a large measure (Bach and Harnish, 1979: 3). However, for better understanding of their function within a speech act, I am going to treat them individually first.2.1. Locutionary ActsThis component of the speech act is probably the least ambiguous. Bach and Harnish (Bach and Harnish 1979: 19), commenting on Austin’s work, point out that Austin distinguishes three aspects of the locutionary act.Austin claims that to say anything is:A.always to perform the act of uttering certain noises (a phonetic act)B.always to perform the act of uttering certain vocables or words ( a phatic act)C.generally to perform the act of using that [sentence] or its constituents with acertain more or less definite ‘sense’ and a more or less definite ‘reference’,which together are equivalent to ‘meaning’ (rhetic act)From this division it follows that the locutionary act comprises other three “sub-acts”: phonetic, phatic and rhetic. This distinction as well as the notion of locutionary act in general was often criticized by Austin’s followers. Searle even completely rejects Austin’s division and proposes his own instead (Searle, 1968: 405). Searle (Searle, 1968: 412) warns that Austin’s rhetic act is nothing else but a reformulated description of the illocutionary act and he therefore suggests another term, the so-called propositional act which expresses the proposition (a neutral phrase without illocutionary force). In other words, a proposition is the content of the utterance.Wardhaugh offers this explanation. Propositional acts are those matters having to do with referring and predicating: we use language to refer to matters in the world and to make predictions about such matters (Wardhaugh, 1992: 285). Propositional acts cannot occur alone since the speech act would not be complete. The proposition is thus expressed in the performance of an illocutionary act. What is essential to note here is that not all illocutionary acts must necessarily have a proposition (utterances expressing states such as ‘Ouch!’ or ‘Damn!’ are “propositionless” as Searle observes (Searle 1976:30)). Having defined the proposition and propositional acts, Searle modifies Austin’s ideas and states that there are utterance acts (utterance acts are similar toAustin’s phonetic and phatic “sub-acts”, Searle (1976:24) defines them as mere uttering morphemes, words and sentences), propositional acts and illocutionary acts.Utterance acts together with propositional acts are an inherent part of the theory of speech acts but what linguists concentrate on the most is undoubtedly the issue of illocutionary acts.2.2. Illocutionary ActsIllocutionary acts are considered the core of the theory of speech acts. As already suggested above, an illocutionary act is the action performed by the speaker in producing a given utterance. The illocutionary act is closely connected with speaker’s intentions, e.g. stating, questioning, promising, requesting, giving commands, threatening and many others. As Yule (Yule, 1996: 48) claims, the illocutionary act is thus performed via the communicative force of an utterance which is also generally known as illocutionary force of the utterance. Basically, the illocutionary act indicates how the whole utterance is to be taken in the conversation.Sometimes it is not easy to determine what kind of illocutionary act the speaker performs. To hint his intentions and to show how the proposition should be taken the speaker uses many indications, ranging from the most obvious ones, such as unambiguous performative verbs, to the more opaque ones, among which mainly various paralinguistic features (stress, timbre and intonation) and word order should be mentioned. All these hints or let’s say factors influencing the meaning of the utterance are called Illocutionary Force Indicating Devices, or IFID as Yule, referring to previous Searle’ s work, calls them (Yule, 1996: 49).In order to correctly decode the illocutionary act performed by the speaker, it is also necessary for the hearer to be acquainted with the context the speech act occurs in. Mey (Mey, 1993: 139) says that one should not believe a speech act to be taking place, before one has considered, or possibly created, the appropriate context.Another important thing, which should not be forgotten while encoding or decoding speech acts, is that certain speech acts can be culture-specific and that is why they cannot be employed universally. Mey shows this on French and American conventions. He uses a French sentence to demonstrate the cultural differences.5. Mais vous ne comperenez pas! (literally, ‘But you don’t understand!’)While a Frenchman considers this sentence fully acceptable, an American could be offended if addressed in similar way as he could take it as a taunt aimed at the level of his comprehension or intelligence (Mey, 1993: 133). The interpretation of speech acts differs throughout the cultures and the illocutionary act performed by the speaker can be easily misinterpreted by a member of different cultural background.From this it also follows that ‘the illocutionary speech act is communicatively successful only if the speaker’s illocutionary intention is recognized by the hearer. These intentions are essentially communicative because the fulfillement of illocutionary intentions consists in hearer’s understanding. Not only are such intentions reflexive. Their fulfillment consists in their recognition’(Bach and Harnish, 1979: 15).Nevertheless, as already pointed out in the previous example, there are cases when the hearer fails to recognize the speaker’s intentions and he therefore wrongly interprets the speaker’s utterance. This misunderstanding may lead to funny situations and hence it is often an unfailing source for various jokes.I have chosen one illustrative example to comment on a bit more.Figure 1.3This picture suggests that the speaker (the man in this case) has uttered a question asking how the woman’s day was. The context and other circumstances are not specified, but let’s suppose that their conversation takes place somewhere in the office3 < /~louden/Interpersonal/IPC%20Materials/GENDER.PPT#6>and that they are colleagues. The man obviously meant his question just as a polite conventional formula with a rather phatic function, not wanting to know any other details. The woman takes him aback a bit since she starts giving him a lot of unsolicited information. She obviously did not catch the intentions behind his words and therefore the man, surprised at her extensive answer, carefully reminds her that she was only supposed to say ‘Fine.’ The communication is uncomfortable for him. The illocutionary act he uttered was not recognized by the woman. The question we should logically ask is ‘Why?’.Talbot (1998: 140) declares that men and women happen to have different interactional styles and misunderstandings occur because they are not aware of them. She even compares the differences in the way men and women talk to already discussed cross-cultural differences. And thus it is possible to see this example as an analogy to that French-American interpretation of the ‘Mais vous ne comperenez pas!’ case. The woman is as if from different cultural milieu and she therefore misinterprets the man’s question.It should be clear by now that the issue of illocutionary acts is sometimes quite complicated because one and the same utterance can have more illocutionary forces (meanings) depending on the IFIDs, the context, the conventions and other factors.6. The door is there.This simple declarative sentence (6) in the form of statement can be interpreted in at least two ways. It can be either understood literally as a reply to the question‘Where is the way out?’ or possibly ‘Where is the door?’ or it can be taken as an indirect request to ask somebody to leave. The sentence has thus two illocutionary forces which, even if they are different, have a common proposition (content). The former case is called a direct speech act, the latter an indirect speech act. It depends on the speaker and on the contextual situation which one he will choose to convey in his speech.Similarly, one illocutionary act can have more utterance acts (or locutionary acts according to Austin) as in:7. a. Can you close the door?b. Will you close the door?c. Could you close the door?d. Would you close the door?e. Can’t you close the door?f. Won’t you close the door? (Hernandez, 2002: 262)All the utterances in (7) are indirect requests, they all have a common illocutionary force, that of requesting.There are hundreds or thousands of illocutionary acts and that is why, for better understanding and orientation, some linguists proposed their classification. The classification which is the most cited in the linguistic literature is that of Searle who divides illocutionary (speech) acts into five major categories (to define them, I will use Levinson’s explanations (Levinson, )):Representatives are such utterances which commit the hearer to the truth of the expressed proposition (e.g. asserting, concluding)8. The name of the British queen is Elizabeth.Directives are attempts by the speaker to get the addressee to do something (e.g. ordering, requesting)9. Would you make me a cup of tea?Commissives commit the speaker to some future course of action (e.g. promising, offering)10. I promise to come at eight and cook a nice dinner for you.Expressives express a psychological state (e.g. thanking, congratulating)11. Thank you for your kind offer.Declarations effect immediate changes in the institutional state of affairs and which tend to rely on elaborate extra-linguistic institutions (e.g. christening, declaring war)12. I bequeath all my property to my beloved fiancee.Searle’s classification is not exhaustive and according to Levinson (Levinson, 1983: 240), it lacks a principled basis. Yet, Searle’s classification helped to become aware of basic types of illocutionary acts and their potential perlocutionary effect on the hearer.2.3. Perlocutionary ActsPerlocutionary acts, Austin’s last element in the three-fold definition of speech acts, are performed with the intention of producing a further effect on the hearer. Sometimes it may seem that perlocutionary acts do not differ from illocutionary acts very much, yet there is one important feature which tells them apart. There are two levels of success in performing illocutionary and perlocutionary acts which can be best explained on a simple example.13. Would you close the door?Considered merely as an illocutionary act (a request in this case), the act is successful if the hearer recognizes that he should close the door, but as a perlocutionary act it succeeds only if he actually closes it.There are many utterances with the purpose to effect the hearer in some way or other, some convey the information directly, others are more careful or polite and they use indirectness to transmit the message.3. IndirectnessIndirectness is a widely used conversational strategy. People tend to use indirect speech acts mainly in connection with politeness (Leech, 1983: 108) since they thus diminish the unpleasant message contained in requests and orders for instance. Therefore similar utterances as in (14) are often employed.14. It’s very hot in here.。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Indirect Speech ActsJOHN R. SEARLEINTRODUCTIONThe simplest cases of meaning are those in which the speaker utters a sentence and means exactly and literally what he says. In such cases the speaker intends to produce a certain Elocutionary effect in the hearer, and he in-tends to produce this effect by getting the Hearer to recognize his intention to produce id and he intends to get the hearer to recognize this intention in virtue of the hearer's knowledge of the rules that govern the utterance of the sentence. But notoriously, not all cases of meaning are this simple: In hints, insinuations. irony, and metaphor to mention a few examples-the speaker's utterance meaning and the sentence meaning come apart in various ways One important class of such cases is that in which the speaker utters a sentence. means what he says, but also means something more For example. a speaker may utter the sentence I want you to do it by way of requesting the hearer to do something. The utterance is incidentally meant as a statement, but it is also meant primarily as a request. a request made by way of making a statement.In such cases a sentence that contains the illocutionary force indicators for one kind of il1ocution,~ry act can be uttered to perform, IN ADDITION, another type of illocutionary act. There are also cases in which the speaker may utter a sentence and mean what he says and also mean another illocution with a different propositional content. For example, a speaker may utter the sentence Can you reach the salt? and mean it not merely as a question but as a request to pass the saltIn such cases it is important to emphasize that the utterance is meant as a request; that is, the speaker intends to produce in the hearer the knowledge that a request has been made to him, and he intends to produce this knowledge by means of getting the hearer to recognize his intention to produce it. Such cases. in which the utterance has two illocutionary forces, are to be sharply distinguished from the cases in which, for example, the speaker tells the hearer that he wants him to do something; and then the hearer does it because the speaker wants him to, though no request at all has been made, meant, or understood. The cases we will be discussing are indirect speech acts, cases in which one Elocutionary act is performed indirectly by way of performing another.The problem posed by indirect speech acts is the problem of how it is possible for the speaker to say one thing and mean that but also to mean something else. And, since meaning consists in part in the intention to produce understanding in the hearer, a large pan of that problem is thatof how it is possible for the hearer to understand the indirect speech act when the sentence he hears and understands means something else. The problem is made more complicated by the fact that some sentences seem almost to be conventionally used as indirect requests. For a sentence like Can you reach the salt? or I would appreciate it if you would get off my foot. it takes some ingenuity to imagine a situation in which their utterances would not be requests.In Searle (1969: chapter 3) I suggested that many such utterances could be explained by the fact that the sentences in question concern conditions of the felicitous performance of the speech acts they are used to perform indirectly-preparatory conditions, propositional content conditions, and sincerity conditions -and that their use to perform indirect speech acts consists in indicating the satisfaction of an essential condition by means of asserting or questioning one of the other conditions. Since that time a variety of explanations have been proposed. involving such things as the hypostatization of 'conversational postulates' or alternative deep structures. The answer originally suggested in Searle (1969) seems to me incomplete, and I want to develop it further here. The hypothesis I wish to defend is simply this: In indirect speech acts the speaker communicates to the hearer more than he actually says by way of relying on their mutually shared background information. both linguistic and nonlinguistic. together with the general powers of rationality and inference on the part of the hearer. To be more specific, the apparatus necessary to explain the indirect part of indirect speech acts includes a theory of speech acts, certain general principles of cooperative conversation [some of which have been discussed by Grice (this volume, Chapter 19)], and mutually shared factual background information of the speaker and the hearer, together with an ability on thepart of the hearer to make inferences. It is not necessary to assume the existence of any conversational postulates (either as an addition to the theory of speech acts or as part of the theory of speech acts) nor any concealed imperative forces or other ambiguities. Me will see, however, that in some cases, convention plays a most peculiar role.Aside from its interest for a theory of meaning and speech acts. the problem of indirect speech acts is of philosophical importance for an additional reason. In ethics it has commonly been supposed that good, right, ought, etc. somehow have an imperative or action guiding' meaning. This view derives from the fact that sentences such as You ought to do it are often uttered by way of telling the hearer to do something. But from the fact that such sentences can be uttered as directives[1] it no more follows that ought has an imperative meaning than from the fact that Can roll reach the salt can be uttered as a request to pass the salt it follows that can has an imperative meaning. Many confusions in recent moral philosophy rest on a failure to understand the nature of suchindirect speech acts. The topic has an additional interest for linguists because of its syntactical consequences, but I shall be concerned with these only incidentally.A SAMPLE CASELet us begin by considering a typical case of the general phenomenon of indirection:(1) Student X: Let s go to the movies tonight(2) Student Y: I have to study for an exam.The utterance of (1) constitutes a proposal in virtue of its meaning, in particular because of the meaning of Let's. In general, literal utterances of sentences of this form will constitute proposals, as in:(3) Let s eat pizza tonight.Or:(4) Let s go ice skating tonight.The utterance of (7) in the context just given would normally constitute a rejection of the proposal, but not in virtue of its meaning. In virtue of its meaning it is simply a statement about Y. Statements of this form do not, in general, constitute rejections of proposals, even in cases in which they are made in response to a proposal. Thus, if Y had said: (5) I have to cat popcorn tonight.Or:(6) 1 have to tie my shoes.in a normal context, neither of these utterances would have been a rejection of the proposal. The question then arises. How does ,\ know that the utterance Is a rejection of the proposal? and that question is a part of the question. How is it possible for Y to intend or mean the utterance of (a) as a rejection of the proposal? In order to describe this case, let us introduce some terminology. Let us say that the PRIMARY illocutionary act performed in Y's utterance is the rejection of the proposal made by X. and that Y does that by way of performing a SECONDARY illocutionary act of making a statement to the effect that he has to prepare for an exam. He performs the secondary illocutionary act by way of uttering a sentence the LITERAL meaning of which is such that its literal utterance constitutes a performance of that illocutionary act. We may, therefore. further say that the secondary illocutionary act is literal; the primary illocutionary act is no.` literal. Let us assume that we know how X understands the literal secondary illocutionary act from the utterance of the sentence. The question is. How does he understand the nonliteral primary illocutionary act from understanding the literal secondary illocutionary act? And that question is part of the larger question. How is it possible for Y to mean the primary illocution when he only utters a sentence that means the secondary illocution, since tomean the primary illocution is (in large part) to intend to produce in X the relevant understanding?A brief reconstruction of the steps necessary to derive the primary illocution from the literal illocution would go as follows. (In normal conversation. of course, no one would consciously go through the steps involved in this reasoning.)STEP 1: I hare made a proposal to Y. and in response he has made a statement to the effectthat he has to study for an exam (facts about the conversation). STEP A: / assume that Y is cooperating in the conversation and that therefore his remark isintended to be relevant (principles of conversational cooperation). STEP 3: .1 relevant response must be one of acceptance, rejection, counterproposal otherdiscussion. etc. (theory of speech acts).STEP 4: But his literal utterance was not one of these, and so was not a relevant response(inherence from Steps I and 3).STEP 5: Therefore, he probably means more than he say. Assuming that his remark isrelevant, his prim ary illocutionary point must differ from his literal one (inference fromSteps 2 and 4).[2]This step is crucial. Unless a hearer has some inferential strategy for finding out when primary illocutionary points differ from literal illocutionary points, he has no way of under-standing indirect illocutionary acts.STEP 6: I know that studying for an exam normally takes a large amount of time relative to asingle evening, and I know than going to the movies normally takes a large amount of timerelative to a single evening (factual back-ground information). STEP 7: Therefore, he probably cannot both go to the movies and study for an exam in oneevening (inference from Step 6).STEP 8: A preparatory condition on the acceptance of a proposal, or on any other commissionis the ability to perform the act predicated in the propositional content condition (theory ofspeech acts).STEP 9: Therefore, I know that he has said some-thing that has the consequence that heprobably cannot consistently accept the proposal (inference from Steps 1, 7, and 8).STEP 10: Therefore, his primary illocutionary point is probably to reject the proposal(inference from Steps 5 and 9).It may seem somewhat pedantic to set all of this out in 10 steps: but if anything, the example is still underdescribed -- I have not. for example, discussed the role of the assumption of sincerity, or the ceteris paribus conditions that attach to various of the steps. Notice, also, that the conclusion is probabilistic. It is and ought to be. This is because the reply does not necessarily constitute a rejection of the proposal. Y might have gone on to say:(7) I have to study for an cram, but let's go to the movies anyhow.(8) I have to study for an exam, but I a do it when we get home from the movies.The inferential strategy is to establish, first, that the primary illocutionary point departs from the literal, and second, what the primary Elocutionary point is.The argument of this chapter will be that the theoretical apparatus used to explain this case will suffice to explain the general phenomenon of indirect illocutionary acts. That apparatus includes mutual background information, a theory of speech acts, and certain general principles of conversation. In particular, we explained this case without having to assume that sentence (a) is ambiguous or that it is 'ambiguous in context' or that it is necessary to assume the existence of any 'conversational postulates in order to explain X's understanding the primary illocution of the utterance. The main difference between this case and the cases we will be discussing is that the latter all have a generality of FORM that is lacking in this example. I shall mark this generality by using bold type for the formal features in the surface structure of the sentences in question. In the field of indirect illocutionary acts, the area of directives is the most useful to study because ordinary conversational requirements of politeness normally make it awkward to issue hat imperative sentences (e.g., Leave the room) or explicit performatives (e.g. I order you to leave the rooter), and we therefore seek to find indirect means to our illocutionary ends (e.g. I wonder if you would mind leaving the room). In directives, politeness is the chief motivation for indirectness.SOME SENTENCES 'CONVENTIONALLY' USED IN THE PERFORMANCE OF INDIRECT DIRECTIVESLet us begin, then, with a short list of some of the sentences that could quite standardly be used to make indirect requests and other directives such as orders. At a pretheoretical level these sentences naturally tend to group themselves into certain categories.[3]GROUP I Sentences concerning H’s ability to perform A:Can you reach the salt?Can you pass the salt?Could you be a little more quiet?You could be a lime more quiet.You can go now (this may also be a permission = you may go now). Are you able to reach the book on the top shelf?Have you got change for a dollar?GROUP 2 Sentences concerning S’s wish or want that H will do A:I would like you to go now.I want you to do this for me, Henry, .I would/should appreciate it if you would/could do it for me.I would/should be most grateful if you would/ could help us out.I'd rather you didn't do that any more.I'd be very much obliged if you would pa! me the money back- soon.I hope you'll do it,I wish you wouldn't do that.GROUP 3 Sentences concerning H’s doing A:Officers will henceforth wear ties at dinner.Will you quit making that awful racket?Would you kindly get off my foot?Won't you stop making that noise soon?Aren't you going to eat your cereal?GROUP 4 Sentences concerning H’s desire or willingness to do A: Would you be willing to write a letter of recommendation for me?Do you want to hand me that hammer over there on the table?Would you mind not making so much noise?Would it on convenient for you to come on Wednesday?Would it be too much (trouble ) for you to pay me the money next Wednesday? GROUP 5 Sentences concerning reasons for doing A:You ought to be more polite to your mother.You should leave immediately.Must you continue hammering that way?Ought you to eat quite so much spaghettis?Should you he wearing John s tie?You had better go now.Hadn't you better go now?Why not stop here?Why don't you try it just once?Why don't you be quiet?It would be better for you (for us all) if you would leave the room. It wouldn't hurt if you left now.It might help if you shut up.It would be better if you gave me the money now.It would on a good idea if you left town.We'd all be 6cacr off if you'd just pipe down a bit.This class also contains many examples that have no generality of form but obviously, in an appropriate context. would be uttered as indirect requests. e.g.:You’re standing on my foot.I can’t see the movie screen while you have that hat on.Also in this class belong, possibly:How many times hare I told you (must I tell you) not to ear with your fingers?I must have told you a dozen times not to eat with your mouth open.If I have told you once I hare told you a thousand times not to wear your hat in the house.GROUP 6 Sentences embedding one of these elements inside another; also. sentences embedding an explicit directive illocutionary verb inside one of these contexts.Would you mind awfully if I asked you if you could write me a letter of recommendation?Would it be too much if I suggested that you could possibly make a little less noise?Might I ask you to take off your hat?I hope you won't mind if I ash you if you could leave us alone.I would appreciate it if you could make less noise.[4]This is a very large class, since most of its members are constructed by permitting certain of the elements of the other classes.SOME PUTATIVE FACTSLet us begin by noting several salient facts about the sentences in question. Plot ever one will agree that what follows are facts; indeed, most of the available explanations consist in denying one or more of these statements. Nonetheless, at an intuitive pre-theoretical level each of the following would seem to be correct observations about the sentences in question, and I believe we should surrender these intuitions only inthe face of very serious counter-arguments. I will eventually argue that an explanation can be given that is consistent with all of these facts. FACT 1: The sentences in question do not have an imperative force as part of their meaning. This point is sometimes denied by philosophers and linguists, but very powerful evidence for it is provided by the fact that it is possible without inconsistency to connect the literal utterance of one of these forms with the denial of any imperative intent, e.g.:I’d like you to do this for me,. Bill, but I am not asking you to do it or requesting that you do itor ordering you to do it or telling you to do it.I’m just asking you, Bill: Why not eat beans? But in asking you that I want you to understandthat I am not telling you to eat beans: I just want to know your reasons for thinking youought not to.FACT 2: The sentences in question are not ambiguous an between an imperative illocutionary force and a non-imperative illocutionary force.I think this is intuitively apparent, but in any case, an ordinary application of Occam’s Razor places the onus of proof on those who wish to claim that these sentences are ambiguous. One does not multiply meanings beyond necessity. Notice, also, that it is no help to say they are 'ambiguous in context,' for all that means is that one cannot always tell from what the sentence means what the speaker means by its utterance, and that is not sufficient to establish sentential ambiguity.FACT 3: Notwithstanding Facts 1 and 2, these are standardly, ordinarily normally -- indeed I shall argue, conventionally -- used to issue directives. There is a systematic relation between these and directive illocutions in a way that there is no systematic relation between I have to study for an exam and rejecting proposals. Additional evidence that they are standardly used to issue imperatives is that most of them take please, either at the end of the sentence or preceding the verb, e.g.: I want you to stop making that noise, please.Could you please lend me a dollar?When please is added to one of these sentences, it explicitly and literally marks the primary illocutionary point of the utterance as directive, even though the Literal meaning of the rest of the sentence is not directive. It is because of the combination of Facts 1, 2, and 3 that there is a problem about these cases at all.FACT 4: The sentences in question are not, in the ordinary sense, idioms.[5] An ordinary example of an idiom is kicked the bucket in Jones kicked the bucket. The most powerful evidence I know that these sentences are not idioms is that in their use as indirect directives they admit of literal responses that presuppose that they are uttered literally. Thus, an utterance of Why don't you be quiet, Henry? admits as a response anutterance of Well. Sally, there are several reasons for not being quiet. First,….Possible exceptions to this are occurrences of would and could in indirect speech acts, and I will discuss them later.Further evidence that they are not idioms is that. whereas a word-for-word translation of Jazzes kicked the bucket into other languages will not produce a sentence meaning ‘Jones died,’ translations of the sentences in question will often, though by no means always, produce sentences with the same indirect illocutionary act potential of the English examples. Thus, e.g., Pourriez-vous m’aider? and Können Sie mir helfen? can be uttered as indirect requests in French or German. I will later discuss the problem of why some translate with equivalent indirect illocutionary force potential and some do not.FACT 5: To say they are not idioms is not to say they are not idiomatic. All the examples given are idiomatic in current English, and - what is more puzzling - they are idiomatically used as requests. In general, non-idiomatic equivalents or synonyms would not have the same indirect Elocutionary act potential. Thus, Do you want to hand me the hammer over there on the table? can be uttered as a request, but Is it the case that you at present de-sire to hand me that hammer over there on the table? has a formal and stilted character that in almost all contexts would eliminate it as a candidate for an indirect request. Furthermore, Are yore able to hand me that hammers, though idiomatic, does not have the same indirect request potential as Can you hand me that hammer? That these sentences are IDIOMATIC and are IDIOMATICALLY USED AS DIRECTIVES is crucial to their role in indirect speech acts. I will say more about the relations of these facts later.FACT 6: The sentences in question have literal utterances in which they are not also indirect requests. Thus, Can you reach the salt? can be uttered as a simple question about your abilities (say, by an orthopedist wishing to know the medical progress of your arm in-jury). I want you to leave can be uttered simply as a statement about one's wants, without any directive intent. At first sight, some of our examples might not appear to satisfy this condition, e.g.:Why nor stop here?Why don't you be quiet?But with a little imagination it is easy to construct situations in which utterances of these would be not directives but straightforward questions. Suppose someone had said lye ought not to stop here. Then Why not stop here? would be an appropriate question. without necessarily being also a suggestion. Similarly, if someone had just said I certainly hate making all this rackets an utterance of (well, then) Why don't you be quiet? would be an appropriate response, without also necessarily being a request to be quiet.It is important to note that the intonation of these sentences when they are uttered as in-direct requests often differs from their into-nation when uttered with only their literal illocutionary force, and often the intonation pattern will be that characteristic of literal directives. FACT 7: In cases where these sentences are uttered as requests, they still have their literal meaning and are uttered with and as having that literal meaning. I have seen it claimed that they have different meanings in context' when they are uttered as requests, but I believe that is obviously false. The man who says I want you to do it means literally that he wants you to do it. The point is that. as is always the case with indirection, he means not only what he says but something more as well. What is added Ache indirect cases is not any additional or different SENTENCE meaning, but additional SPEAKER meaning. Evidence that these sentences keep their literal meanings when uttered as indirect requests is that responses that are appropriate to their literal utterances are appropriate to their indirect speech act utterances (as we noted in our discussion of Fact 4).e.g.:Can you pass the salt?No, sorry, I can’t, it s down there at the end of the table.Yes, I can. (Here it is.)FACT 8: It is a consequence of Fact 7 that when one of these sentences is uttered with the primary illocutionary point of a directive, the literal illocutionary act is also performed. In every one of these cases, the speaker issues a directive BY WAY OF asking a question or making a statement. But the fact that his primary illocutionary intent is directive does not alter the fact that he is asking a question or making a statement. Additional evidence for Fact 8 is that a subsequent report of the utterance can truly report the literal illocutionary act.Thus, e.g., the utterance of I want you to leave now, Bill can be reported by an utterance of He told me he wanted me to leave, so I left. Or, the utterance of Can you reach the salt? can be reported by an utterance of He asked me whether I could reach the salt Similarly, an utterance of Could you do it for me, Henry? could you do it for me and Cynthia and the children? can be reported by an utterance of He asked me whether I could do it for him and Cynthia and the children.This point is sometimes denied. I have seen it claimed that the literal illocutionary acts are always defective or are not 'conveyed' when the sentence is used to perform a nonliteral primary illocutionary act. As far as our examples are concerned, the literal illocutions are always conveyed and are sometimes, but not in general. defective. For example, an indirect speech act utterance of Can you reach tire salt.' may be defective in the sense that S may already know the answer. But even this form NEED not be defective. (Consider, e.g.. Can you give me cl1ange fora dollar'.) Even when the literal utterance is defective. the in-direct speech act does not depend on its being defective.AN EXPLANATION IN TERMS OF THE THEORY OF SPEECH ACTSThe difference between the example concerning the proposal to go to the monies and all of the other cases is that the other cases are systematic. What we need to do, then, is to describe an example in such a way as to show how the apparatus used on the first example will suffice for these other cases and also will explain the systematic character of the other cases.I think the theory of speech acts will enable us to provide a simple explanation of how these sentences, which have one illocutionary force as part of their meaning, can be used to perform an act with a different illocutionary force. Each type of illocutionary act has a set of conditions that are necessary for the successful and felicitous performance of the act. To illustrate this, I will present the conditions on two types of acts within the two genuses, directive and commissive (Searle, 1969: chap. 3).A comparison of the list in Table 16.1 of felicity conditions on the directive class of illocutionary acts and our list of types of sentences used to perform indirect directives show that Groups 1-6 of types can be reduced to three types: those having to do with felicity conditions on the performance of a directive illocutionary act. those having to do witch reasons for doing the act. and those embedding one element inside anotherTable 16.1. Directive and Commissive Felicity ConditionsDirective(request) Commissive (promise)--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Preparatory condition H is able to perform A. S is able to perform A.He wants S to perform A.Sincerity condition S wand H to do A. S intends to do A.Propositional content S predicates a future act A of H. S predicates a future act A of S.conditionEssential condition Counts as an attempt by S to Counts as the undertaking by Sget H to do A. of an obligation to do A.----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------one. Thus, since the ability of H to perform A (Group 1) is a preparatory condition. the desire of S that H perform A (Group 2) is the sincerity condition, and the predication of A of H (Group 3) is the propositional content condition. all of Groups 1-3 concern felicity conditions on directive illocutionary acts. Since wanting to do something is a reason par excellence for doing it. Group 4 assimilates to Group 5, as both concern reasons for doing A. Group 6 is a special class only by courtesy. since its elements either are performative verbs or are already contained in the other two categories of felicity conditions and reasons. Ignoring the embedding cases for the moment, if we look at our lists and our sets ofconditions, the following generalizations naturally emerge: GENERALIZATION 1: S can make an indirect request (or other directive) by either askingwhether or stating that a preparatory condition concerning H’s ability to do A obtains.GENERALIZATION 2: S can make an indirect directive by either asking whether or statingthat the propositional content condition obtains GENERALIZATION 3: S can make an indirect directive by stating that the sincerity conditionobtains, but not by asking whether it obtains.GENERALIZATION 4:S can make an indirect directive by either stating that or askingwhether there are good or overriding reasons for doing A,except where the reason is that Hwants or wishes, etc., to do A, in which case he can only ask whether H wants, wishes, etc.,to do A.It is the existence of these generalizations that accounts for the systematic character of the relation between the sentences in Groups 1-6 and the directive class of Elocutionary acts. Notice that these are。