英译汉(文学翻译)

文学翻译(英译汉)

I thought of that one evening as I was driving. The moon, one day short of fullness, rode with me, first gliding smoothly, then bouncing over the bumpy stretches, now on my right, then straight ahead, the silver light washing over dry grasses in open fields, streaking along through black branches, finally disappearing as the road wound its way through the一轮满月晃晃悠悠地悬浮在上面,离我们那么近,仿佛就要掉下来撞到我们身上。它光华照人,比前一天晚上还大,更令人心驰神往,在熔银般的水塘上空悄悄地爬升。就连十岁的孩童也能看出,这不仅仅是个月亮。这是个大写的月亮。

我转过身,只见约翰正咧着嘴笑,满脸期盼的神情;他热切的目光想从我的脸上探明他是否博得了我的欢心。他确实博得了我的欢心。我意识到现在月儿也正在随他同行。

(方杰译)

讲解

这是一篇非常优美的关于月亮的散文,它将细腻的描写和真挚的情感及人生感悟交融在一起。翻译这样的文章,译者不仅要译出基本信息——字面上的意思,还要译出原文的韵味。这就需要在选词、句式安排及形象化词语的运用上仔细琢磨,不仅要注意字、句上的局部效果,更要注意段落、篇章的整体效果。

John blinked a few times and looked at me as if I might, indeed, be loony. “Mom, it’s just the moon. Is this the surprise?” I suppose he was hoping for a puppy.

文学翻译(汉译英)

文学翻译:1.《柳家大院》(节选)原文作者:老舍这两天我们大院里又透着热闹,出了人命。

事情可不能由这儿说起,得打头来。

先交代我自己吧。

我是个算命的先生,我也卖过酸枣、落花生什么的。

那可是先前的事了。

现在我在街上摆卦摊儿;好了呢,一天也抓弄三毛五毛的。

老伴儿早死啦,儿子拉洋车。

我们爷儿俩住着柳家大院的一间北房。

除了我这间北房,大院里还有二十多间房呢。

一共住着多少家子,谁说得清?住两间房的就不多,又搭上今儿个搬来,明儿个又搬来,我没那么好的记性。

大家见面,招呼声“吃了吗?”透着和气,不说呢,也没什么。

大家一天到晚为嘴奔命,没有工夫扯闲盘儿。

爱说话的自然也有。

可得先吃饱啦。

王家住两间房。

老王和我算是柳家大院最“文明”的人了。

“文明”是三孙子。

2.《柳家大院》(节选)译文A prettykick-up has been the order of the day again in our compoun d lately, for a life has been lost.Butthisisn’tthewaytoopentheball. We shouldgo the whole animal.First , a few words about myself.I’mafortune-teller. Once I was a venderof sour dates , ground-nuts and what not. But that was ages ago. Now I keep a fortune-teller’sstallontheside-walk and can scrapeup three or five dimes a day at best. My old gal had long kickedup her heels. Myson’saricksha w-boy. That’swhathe’s. We two , fatherand son , hang our hats at a south-facingroom in the Liu’scompoun d.Besides the room we occupythere are twentymore rooms in the same compoun d. How many familie s live there , only God knows. Those who occupytwo rooms are quite few. Besides , they are alwaysonthego.Ihaven’tgotsuchagoodmemor yas to remembe r all that. When peoplemeet , theygreeteachotherwitha“Howdoyoudo?”, just to show their good neighbo urly feeling s. But if they shouldcut each other dead , nobodywould care. Whenone’sknocked about from pillarto post for his bread day in and day out , hewon’tfindgingerenoughfor gas and gaiters. Of course, there’sthosewhoarealljawlikeasheep’sheadamongus. But one can hardlybe in a mood for rag-chewingwhenone’sgutscrycupboar d .The Wang familyoccupie s two rooms. Old Wang and I are conside red the genteel fork in the compoun d. Gentili ty be hanged!注释:kick-up:有了问题,出了毛病open the ball:作为开头what not:诸如此类的东西old gal:(口)老伴kickedupone’sheels:(俚) 死ricksha w :人力车,黄包车hangone’shatson:指望,依靠on the go:(口)忙个不停cut sb. dead:不理睬某人knock about :(口)漂泊,游荡from pillarto post :四处奔走着,到处碰壁地,for his bread (俚) =for his moneyday in and day out :日复一日,每天不间断地ginger:(口)精力,活力,劲头gas :(俚)令人非常满意(或愉快的)的事(或人)bealljaw(likeasheep’shead):全是空话,废话连篇rag :(俚)姑娘,情人(指女性)guts:(用作单)贪食者be hanged:(用于诅咒语中)不得好死3.原文言语风格分析老舍先生是善于运用群众的言语大师。

经典英译汉文章翻译赏析

英译汉文章翻译赏析时间:2009年06月01日【英译中选段六】原文(by Robert Frost)The Gift OutrightThe land was once ours before we were the land’s.She was our land more than a hundred years.Before we were her people. She was oursIn Massachusetts, in Virginia;But we were England’s, still colonials,Possessing what we still were unpossessed by,Possessed by what we now no more possessed.Something we were withholding made us weakUntil we found out that it was ourselvesWe were withholding from our land of living,And forthwith found salvation in surrender.Such as we were we gave ourselves outright(The deed of gift was many deeds of war)To the land vaguely realizing westward,But still unstoried, artless, unenhanced,Such as she was, such as she would become.(原载 )译文(余光中译):全心的奉献土地先属于我们,我们才属于土地。

她成为我们的土地历一百余年,我们才成为她的人民。

当时她属于我们,在麻萨诸塞,在佛吉尼亚,但我们属于英国,仍是殖民之身,我们拥有的,我们仍漠不关心,我们关心的,我们已不再拥有。

大学汉英翻译教程第九章 文学翻译之诗歌翻译PPT资料59页

——李白《独坐敬亭山》 All birds have flown away, so high;

A lonely cloud drifts on, so free, We are not tired, the Peak and I,

Nor I of him, nor he of me. (英译文押abab韵) ——许渊冲译

(3)三重韵(triple rhyme) 指的是在最末三个音节上押韵,且第二三音节弱读: Touch her not scornfully, Think of her mournfully. 碰她时别轻蔑, 想她时要悲切。 本句中就是有三个音节押韵的,但是就主体严肃的诗歌而言,押韵很少超过 两个音节。

1. 根据押韵的位置,可以分为三种形式:

(1)押尾韵(end rhyme/rime) 这是最常见的押韵,出现在每行诗的末尾。如: Up from the meadow rich with corn, Clear in the cool September morn. 在生产玉米的草原附近, 在九月的一个凉爽的早晨。 (2)押头韵(head rhyme/rime) 即每行诗的第一音节押韵。这与押尾韵恰好相反。如: Mad from life’s history; Glad to death’s mystery. 人生的遭遇使她发了狂, 她乐于追求死的神秘。 (3)押中间韵(internal rhyme/rime) 这个也称押腰韵,指同一行诗中出现两个或两个以上的押韵。如: I bring fresh showers for the thirsty flowers From the seas and streams 我为焦渴的鲜花,从河川,从海洋, 带来清新的甘霖。

美国文学选读第二版课文翻译中英对照

美国文学选读第二版课文翻译中英对照Moscow,1918这一篇的开头:In Moscow,by late March,all was confusion,heterogeny,and motion.夏先生评:“照一般中国人思想习惯,这三个词应该是形容词的。

形容词通常分量较名词为轻,因为形容词是依附名词而存在的。

这里这三个抽象名词,站得很稳,好像大门上的柱子。

进了大门,略走一步,便五花八门令人目不暇接了。

”再比如The Treasure Game的开头:From the calm of her place under the acacia tree,on the swinging canopy seat,Mrs.Fairfax listened with growing impatience to the loud chock of croquet balls cracking the silence of afternoon,each stroke like the chime of a wooden clock setting off peals of senseless and exhausting laughter.先生评:calm当名词用,英文中颇常见,但似和中国人思想习惯不合。

我们常常只把它当形容词用:“安静的环境”或“安静的地方”,很少会说“从那个地方的安静里面听来”这一类的话。

阅读时,我建议大家自己先独立赏析字词句段。

并且一定要对自己诚实,通过看先生的评注和查字典、搜索,把每一个细节都弄懂。

只有这样,读完这本书后才会增加功力。

我会先通读整段,遇到不认识的词、没有一次读懂的句子,先做标记。

读完整段后再通过查词典、分析语法解决前面的问题,并做自己的赏析笔记。

最后,再看先生的批注,通过对比找到差距。

比如书中有一段来自长篇小说《心是个寂寞的猎者》(The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter)的选段:The Greek was very fretful,and kept finding fault with the fruit drinks and food that Singer prepared for him.Constantly he made his friend help him out of bed so that he could pray.He fumbled with his hands to say'DarlingMary'and then held to the small brass cross tied to his neck with a dirty string.His big eyes would wall up to the ceiling with a look of fear in them,and afterwards he was very sulky and would not let his friend speak to him.”这段文字比较简单,如果是精读我会从字词角度这样做笔记:fretful 来自动词fret,《经济学人》中常用fret about表示“担心”。

《柳家大院》汉译英

文学翻译:1.《柳家大院》(节选)原文作者:老舍这两天我们大院里又透着热闹,出了人命。

事情可不能由这儿说起,得打头来。

先交代我自己吧。

我是个算命的先生,我也卖过酸枣、落花生什么的。

那可是先前的事了。

现在我在街上摆卦摊儿;好了呢,一天也抓弄三毛五毛的。

老伴儿早死啦,儿子拉洋车。

我们爷儿俩住着柳家大院的一间北房。

除了我这间北房,大院里还有二十多间房呢。

一共住着多少家子,谁说得清?住两间房的就不多,又搭上今儿个搬来,明儿个又搬来,我没那么好的记性。

大家见面,招呼声“吃了吗?”透着和气,不说呢,也没什么。

大家一天到晚为嘴奔命,没有工夫扯闲盘儿。

爱说话的自然也有。

可得先吃饱啦。

王家住两间房。

老王和我算是柳家大院最“文明”的人了。

“文明”是三孙子。

2.《柳家大院》(节选)译文A pretty kick-up has been the order of the day again in our compound lately , for a life has been lost.But this isn’t the way to open the ball . We should go the whole animal.First , a few words about myself. I’m a fortune-teller. Once I was a vender of sour dates , ground-nuts and what not. But that was ages ago. Now I keep a fortune-teller’s stall on the side-walk and can scrape up three or five dimes a day at best. My old gal had long kicked up her heels. My son’s a rickshaw-boy. That’s what he’s. We two , father and son , hang our hats at a south-facing room in the Liu’s compound.Besides the room we occupy there are twenty more rooms in the same compound. How many families live there , only God knows. Those who occupy two rooms are quite few. Besides , they are always on the go. I haven’t got such a good memory as to remember all that. When people meet , they g reet each other with a “How do you do ?”, just to show their good neighbourly feelings. But if they should cut each other dead , nobody would care. When one’s knocked about from pillar to post for his bread day in and day out , he won’t find ginger enough for gas and gaiters. Of course , there’s those who are all jaw like a sheep’s head among us. But one can hardly be in a mood for rag-chewing when one’s guts cry cupboard .The Wang family occupies two rooms. Old Wang and I are considered the genteel fork in the compound. Gentility be hanged!注释:kick-up:有了问题,出了毛病open the ball:作为开头what not:诸如此类的东西old gal:(口)老伴kicked up one’s heels :(俚) 死rickshaw :人力车,黄包车hang one’s hats on:指望,依靠on the go:(口)忙个不停cut sb. dead:不理睬某人knock about :(口)漂泊,游荡from pillar to post :四处奔走着,到处碰壁地,for his bread (俚) =for his moneyday in and day out :日复一日,每天不间断地ginger :(口)精力,活力,劲头gas :(俚)令人非常满意(或愉快的)的事(或人)be all jaw (like a sheep’s head) :全是空话,废话连篇rag :(俚)姑娘,情人(指女性)guts:(用作单)贪食者be hanged:(用于诅咒语中)不得好死3.原文言语风格分析老舍先生是善于运用群众的言语大师。

外国散文翻译(英译汉)

2014年第05期79外国散文翻译(英译汉)文/李洁茜Writers Afootby Edward HoaglandEssays are how we speak to one another in print--- caroming thoughts not merely in order to convey a certain packet of information ,but with a special edge or bounce of personal character in a kind of public letter.You multiply yourself as a writer. gaining height as though jumping on a trampoline, if you can catch the gist of what other people have also been feeling and clarify it for them. Classic essay subjects,like the flux of friendship "On Greed,''On Religion," "On Vanity" or solitude, lying, self-sacrifice, can be major-league yet not require Bertrand Russell to handle them. A lay-man who has diligently looked into something, walking in the mosses of regret after the death of a parent for instance ,may acquire an intangible authority even with-out being memorably angry or funny or possessing a beguiling equanimity. He cares; therefore, if he has tinkered enough with his words, we do too.An essay is not a scientific document.It can be serendipitous or domestic,satire or testimony ,tongue-in-cheek or a wail of grief.Mulched perhaps in its own contradictions ,it promises no a base of obstruction ,and sometimes such leaps of illogic or superlogic that they may work a bit like magic realism in a novel:namely ,to stimulate the mind ’s own processes in a murky and incongruous world. More than being instructive, as a magazine article is, an essay has a slant, a seasoned personality behind it that ought to weather well. Even if we think the author is telling us the earth is flat, we might want to listen to him elaborate upon the fringes of his premise because the bristle of his narrative and what he's seen intrigues us. He has a cutting edge,yet balance too. A given body of information is going to be eclipsed, but what lives in all is spirit, not factuality and we respond to Montaigne's human touch despite four centuries of technological and social change.Montaigne's Essais predated by a quarter-century Cervantes's Don Quixote ,which was probably the first novel.And the form of composition Montaigne gave a name to would not have lasted so long if it were not succinct ,diverse ,and supple ,able to welcome ideas that are ahead of or behind the blurring spokes of his own time.But whereas a novelist is often a trapezist ,vaulting from book to book ,an essayist is afoot. Not a puppet master or ventriloquist, he will sound recognizable in his next appearance in print. There is a value to this, though Don Quixote as a figure outshines any essay. Imperishably appealing, he is an embodiment, not speculation, and we can simply call him to mind, much as we remember Conrad's Kurtz, in Heart ofDarkness, and Dickens's Oliver Twist, although the regimes up the Congo River and in London aren't now the same.An essayist's materials are drawn primarily from his or her own life, and he knits a skein of thoughts and impressions, not a made-up tale. An epic drama such as King Lear is thus not his province even to dream about. His work is humbler, and our expectations of him are less elas-tic than of novelists or poets and their creations. They can flame out in a flash tire,surreal or villainous,if the story is compelling or the language smacks a bit of genius.We accept different behavior from Celine or Genet, Christopher smart or Ezra Pound,than from Dr.Johnson. Norman Mailer can stab his wife and Will-iam Burroughs can shoot his, and somehow we don't blanch they "needed to,' one hears it said. Their imaginations must have got the better of them.but if an essayist had done the same it would have queered his legacy. He is supposed to be the voice of reason. Though modestly chameleon as a monologuist (and however much he wants to recalibrate it), he is an advocate for civilization. He doesn't murder a foe in the street, like the sculptor Benvenuto Cellini, or get himself slain in a tavern braw, like the playwright Christopher Marlowe, or gut-shot, like John Ruskin, in a duel. A murderer or madwoman quarantined in a book on the bedside table can provide excitation and cautionary reading, but an essayist, being his own protagonist, should be faceted rather like a friend. We might give him our keys and put him up in the guest room. He won't be stealing the silverware and debauching the children,and,after sleeping on our problems, he will sit at the breakfast table in the morning sunshine and tell us what we ought to do. Or, at the outside if 一like the master essayist Charles Lamb-his sister has slaughtered his mother,he will devote the next thirty-odd years to piecing together a productive existence for himself and her, not despairing like an aficionado of the Absurd.Essayists are not Dadaists, and in the endgame that may be in progress-with our splintering attention span, our hiccupping religions, staccato science, and spinning solipsism 一they may prove useful.Do we human beings have a special spark of divinity ?And if so ,as we mince our habitat and compress ourselves into ever tighter spaces ,having always claimed that there couldn ’t be too much of a good thing ,how many of us are finally going to constitute a glut of divinity ? Judeo-Christianity hasn't said. Nor did "the Laws of Nature and at Nature ’s God''which Thomas Jefferson invoked at the beginning of our Declaration of Independence. Or Emerson's rapturous prescription in Nature in 1836(Emerson being the other founding father ofessay writing in America) that an intelligent observer should become "a transparent eyeball...part or particle of God," amid nature's ramifying glory. Now man threatens to become a divinity doubled,redoubled, and berser and nausea. However, the essay's brevity, transparency, and versatility should suit this age of reconsideration.Essays are a limited genre because the writer will suggest that life is more than money for example, without inventing Scrooge; that brownnosing demeans everybody, without the specter of Uriah Heep. Candide, starbuck, Injun Joe, Moll Flanders and Becky Sharp led lives more farfetched than an essayist's, whose medium is mostly what he can testify to having seen or read. Working in the present tense, with common sense his currency, "This is what I think,he tells the rest of us. And even if he speaks about alarming omens. we feel he'll be around tomorrow, not leap headlong into life and burn to a crisp at thirty 一two or twenty-eight, like Hart Crane or Stephen Crane, or wind up forlorn in a railroad station fleeing his wife,as Tolstoy did when dying. "The limitations are reassuring as well as tethering.James Baldwin didn't metamorphose into an arsonist or a rifleman when he warned against race war in The First Next Time. And George Orwell deconstructed colonialism In essay considerably more nuanced than Heart of Darkness--supplementing though not supplanting Kurtz's immortal line "The horror!The horror!'' In a way it's easier to visit a head-waters area of the Nile or Congo and find conditions not substantially improved since independence when you've read Orwell as well as Conrad on human nature, because these nuances prepare you better for disillusion. Conrad's picture was so stark,surely never again would the world see comparable scenes !Ripples sway us --traffic tie --ups on a cloverleaf ,on line stock swings ,revenge of the-rain-forest viral escapees-at the same that our proud provincialism is called upon to bend the mind around Islam's surging claims, Latino vigor and disorder, chaos in Africa,and a Chinese-puzzle future. In a famine belt along the upper Nile, I've seen child- sized raw dirt graves scattered everywhere beside a poignant web of paths of the sort that starving people pace. A scrap of shirt or broken toy was laid on top of each small mound to personalize the spot; and hundreds of bony, wobbling' children who had survived so far ran toward me (a white-haired white man) to touch my hands in hopes that I might somehow be powerful enough to bring in shipments of food to save their lives. Their urgent smiles were giddy or delirious in skulls already outlined under tightened skin-thoughW文学色彩E N X U E S E C A Ithey were fatalistic,almost docile, too, because so many adults had told them for so many weeks that there was nothing to eat and so many people whom they knew had died. I interviewed the Sudanese guerrilla general who was in charge of protecting them about what could be done, but he was delayed a little that afternoon because (I found out later from an Amnesty International report) he had been torturing a colleague by pounding a nail through his foot. Ripples sway us --traffic tie --ups on a cloverleaf,on line stock swings ,revenge of the-rain-forest viral escapees-Now essayists in dealing with the present tense are stuck with the nuts and bolts of what's going on. And what do you say about that endgame on the Nile, which I believe was a forerunner,not an anomaly?I expect an epidemic of disintegration in other forms. Essayists will become ' journeymen," in a new definition for that hackneyed term:out on the rim, seeing what's in store. The cataract of memoirs being published currently may be a prelude to this-memoirs of a cascading endgame. Yet essayists are not nihilists as a rule.They look for context. They feel out traction.They have a stake in society’s survival,behavior,for instance,in a manner that most fiction writers would eschew because an essayist’s opinions are central,part of the very protein that he gives us.Not omniscient like a novelist, who can create a world he wants to work with, he has the job of finding coherence in the world that we already have. This isn't harder, just a different task. And he usually comes to it in middle age, having acquired some ballast of experience and tested views---may indeed have written several novels, because of the higher glamour and freedom of that calling. (For what it's worth,I sold my first novel at twenty-one and wrote my first thirty-five.)"Art is not truth. Art is a lie that makes us realize truth''as Picasso said; and to capture within an imagined story some petal of human longing and defeat is an achievement irresistibly appealing.Essayists,by denying themselves that license to extravagantly fudge the facts of first-hand observation,relegate themselves to the Belles Lettres section of the bookstore,neither fiction nor journalism,because they do partly fudge their reportage,adding the spice of temperament and a lifetime’s favorite reading.And if an enigma seems a jigsaw they will tend to see a picture in it: that life therefore is not an oubliette'. The fracases they get into are on behalf of democracy as they see it (Montaigne, Orwell, and Baldwin again are examples),and their iconoclasm commonly leans toward the ideal of comforting the afflicted and afflicting the comfortable’’which journalists used to aspire to. Like a short-story writer, an essayist is after the gist of life, not Balzacian documentation. And, like a soothsayer with a chicken's entrails, he will spread his innards" out before us to discern a pattern. Not just confessional, however, a good es-say is driven by the momentum of an inquiry, searching out a point, such as are we divine?一an awfully big one for a lowly essayist, but it may be the question of the coming centuryEssayists also go to the fights, or rub shoulderson the waterfront, get divorced ("Ouch," says thereader, "that was like mine"), nibble canapes",playing off theirpreconceptions of a celebrity or a politician againstreality. they will examine a prejudice (is thispiquant or ignoble, educated or soggy?or dare a piein the face for advancing an out of fashion idea。

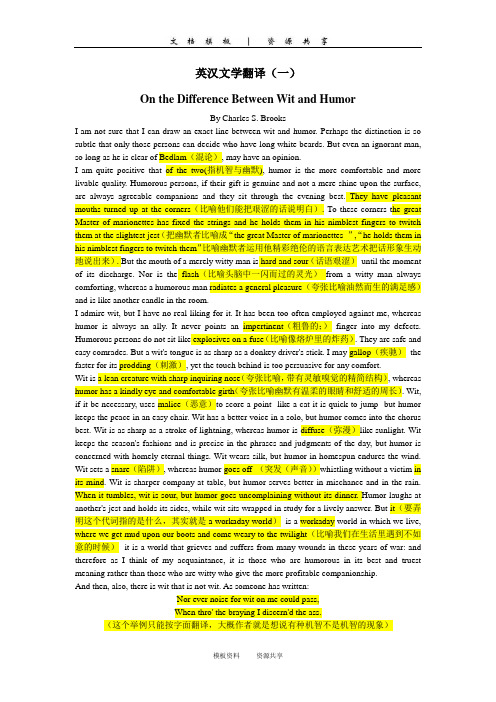

资料:1. 文学翻译英汉一

英汉文学翻译(一)On the Difference Between Wit and HumorBy Charles S. BrooksI am not sure that I can draw an exact line between wit and humor. Perhaps the distinction is so subtle that only those persons can decide who have long white beards. But even an ignorant man, so long as he is clear of Bedlam(混论), may have an opinion.I am quite positive that of the two(指机智与幽默), humor is the more comfortable and more livable quality. Humorous persons, if their gift is genuine and not a mere shine upon the surface, are always agreeable companions and they sit through the evening best. They have pleasant mouths turned up at the corners(比喻他们能把艰涩的话说明白). To these corners the great Master of marionettes has fixed the strings and he holds them in his nimblest fingers to twitch them at the slightest jest(把幽默者比喻成“the great Master of marionettes ”,“he holds them in his nimblest fingers to twitch them”比喻幽默者运用他精彩绝伦的语言表达艺术把话形象生动地说出来). But the mouth of a merely witty man is hard and sour(话语艰涩)until the moment of its discharge. Nor is the flash(比喻头脑中一闪而过的灵光)from a witty man always comforting, whereas a humorous man radiates a general pleasure(夸张比喻油然而生的满足感)and is like another candle in the room.I admire wit, but I have no real liking for it. It has been too often employed against me, whereas humor is always an ally. It never points an impertinent(粗鲁的;)finger into my defects. Humorous persons do not sit like explosives on a fuse(比喻像熔炉里的炸药). They are safe and easy comrades. But a wit's tongue is as sharp as a donkey driver's stick. I may gallop(疾驰)the faster for its prodding(刺激), yet the touch behind is too persuasive for any comfort.Wit is a lean creature with sharp inquiring nose(夸张比喻,带有灵敏嗅觉的精简结构), whereas humor has a kindly eye and comfortable girth(夸张比喻幽默有温柔的眼睛和舒适的周长). Wit, if it be necessary, uses malice(恶意)to score a point--like a cat it is quick to jump--but humor keeps the peace in an easy chair. Wit has a better voice in a solo, but humor comes into the chorus best. Wit is as sharp as a stroke of lightning, whereas humor is diffuse(弥漫)like sunlight. Wit keeps the season's fashions and is precise in the phrases and judgments of the day, but humor is concerned with homely eternal things. Wit wears silk, but humor in homespun endures the wind. Wit sets a snare(陷阱), whereas humor goes off (突发(声音))whistling without a victim in its mind. Wit is sharper company at table, but humor serves better in mischance and in the rain. When it tumbles, wit is sour, but humor goes uncomplaining without its dinner. Humor laughs at another's jest and holds its sides, while wit sits wrapped in study for a lively answer. But it(要弄明这个代词指的是什么,其实就是a workaday world)is a workaday world in which we live, where we get mud upon our boots and come weary to the twilight(比喻我们在生活里遇到不如意的时候)--it is a world that grieves and suffers from many wounds in these years of war: and therefore as I think of my acquaintance, it is those who are humorous in its best and truest meaning rather than those who are witty who give the more profitable companionship.And then, also, there is wit that is not wit. As someone has written:Nor ever noise for wit on me could pass,When thro' the braying I discern'd the ass.(这个举例只能按字面翻译,大概作者就是想说有种机智不是机智的现象)I sat lately at dinner with a notoriously witty person (a really witty man) whom our hostess had introduced to provide the entertainment. I had read many of his reviews of books and plays, and while I confess their wit and brilliancy, I had thought them to be hard and intellectual and lacking in all that broader base of humor which aims at truth. His writing--catching the bad habit of the time--is too ready to proclaim a paradox and to assert the unusual, to throw aside in contempt the valuable haystack(干草堆)in a fine search for a paltry(无价值的)needle. His reviews are seldom right--as most of us see the right--but they sparkle and hold one's interest for their perversity(邪恶)and unexpected turns.In conversation I found him much as I had found him in his writing--although, strictly speaking, it was not a conversation, which requires an interchange of word and idea and is turn about. A conversation should not be a market where one sells and another buys. Rather, it should be a bargaining back and forth, and each person should be both merchant and buyer. My rubber plant for your victrola(手摇留声机), each offering what he has and seeking his deficiency. It was my friend B--- who fairly(简直)put the case(假设)when he said that he liked so much to talk that he was willing to pay for his audience by listening in his turn.But this was a speech and a lecture. He loosed on us(loose something on/upon someone/something)from the cold spigot(水龙头)of his intellect a steady flow of literary(文学的) allusion(比喻)--a practice which he professes(公开)to hold in scorn--and wit and epigram(警句). He seemed torn from the page of Meredith(像从梅雷迪斯这本书里面走出来的人物一样). He talked like ink. I had believed before that only people in books could talk as he did, and then only when their author had blotted and scratched their performance for a seventh time before he sent it to the printer. To me it was an entirely new experience, for my usual acquaintances are good common honest daytime woollen folk(毛原民风斗篷)[132] and they seldom average better than one bright thing in an evening.At first I feared that there might be a break in his flow of speech which I should be obliged to fill. Once, when there was a slight pause--a truffle(松露)was engaging him--I launched a frail remark; but it was swept off at once in the renewed torrent. And seriously it does not seem fair. If one speaker insists--to change the figure--on laying all the cobbles of a conversation, he should at least allow another to carry the tar pot and fill in the chinks(裂缝). When the evening was over, although I recalled two or three clever stories, which I shall botch in the telling, I came away tired and dissatisfied, my tongue dry with disuse.Now I would not seek that kind of man as a companion with whom to be becalmed in a sailboat, and I would not wish to go to the country with him, least of all to the North Woods or any place outside of civilization. I am sure that he would sulk(生气愠怒)if he were deprived of an audience. He would be crotchety(想入非非的)at breakfast across his bacon. Certainly for the woods a humorous man is better company, for his humor in mischance comforts both him and you.A humorous man--and here lies the heart of the matter--a humorous man has the high gift of regarding an annoyance in the very stroke of it as another man shall regard it when the annoyance is long past. If a humorous person falls out of a canoe he knows the exquisite jest while his head is still bobbing in the cold water. A witty man, on the contrary, is sour until he is changed and dry: but in a week's time when company is about, he will make a comic story of it.My friend A--- with whom I went once into the Canadian woods has genuine humor, and no one can be a more satisfactory comrade. I do not recall that he said many comic things, and at bottom he was serious as the best humorists are. But in him there was a kind of joy and exaltation thatlasted throughout the day. If the duffle(露营装备)were piled too high and fell about his ears, if the dinner was burned or the tent blew down in a driving storm at night, he met these mishaps as though they were the very things(想要的)he had come north to get, as though without them the trip would have lacked its spice. This is an easy philosophy in retrospect but hard when the wet canvas falls across you and the rain beats in. A--- laughed at the very moment of disaster as another man will laugh later in an easy chair. I see him now swinging his axe for firewood to dry ourselves when we were spilled in a rapids; and again, while pitching our tent on a sandy beach when another storm had drowned us. And there is a certain cry of his (dully, Wow! on paper) expressive to the initiated of all things gay, which could never issue from the mouth of a merely witty man.Real humor is primarily human--or divine, to be exact--and after that the fun may follow naturally in its order. Not long ago I saw Louis Jouvet(查不到权威翻译,只能自己音译) of the French Company play Sir Andrew Ague-Cheek. It was a most humorous performance of the part, and the reason is that the actor made no primary effort to be funny. It was the humanity of his playing, making his audience love him first of all, that provoked the comedy. His long thin legs were comical and so was his drawling talk, but the very heart and essence was this love he started in his audience. Poor fellow! How delightfully he smoothed the feathers in his hat! How he feared to fight the duel! It was easy to love such a dear silly human fellow. A merely witty player might have drawn as many laughs, but there would not have been the catching at the heart.As for books and the wit or humor of their pages, it appears that wit fades, whereas humor lasts. Humor uses permanent nutgalls. But is there anything more melancholy than the wit of another generation? In the first place, this wit is intertwined with forgotten circumstance. It hangs on a fashion(风尚犹存)--on the style of a coat. It arose from a forgotten bit of gossip. In the play of words the sources of the pun are lost. It is like a local jest in a narrow coterie(小圈子), barren to an outsider. Sydney Smith was the most celebrated wit of his day, but he is dull reading now. Blackwood's at its first issue was a witty daring sheet, but for us the pages are stagnant. I suppose that no one now laughs at the witticisms of Thomas Hood. Where are the wits of yesteryear? Yet the humor of Falstaff and Lamb and Fielding remains and is a reminder to us that humor, to be real, must be founded on humanity and on truth."On the Difference Between Wit and Humor" by Charles S. Brooks first appeared in the collection Chimney-Pot Papers published in 1919 by Yale University Press.词汇表:(一)人名地名FalstaffLambFieldingthe North WoodsLouis JouvetCharles S. Brooks(二)生僻词Bedlam(混论)impertinent(粗鲁的)coterie(小圈子)paltry(无价值的)spigot(水龙头)woollen folk(毛原民风斗篷)perversity(邪恶)(三)心理情感类crotchety(想入非非的)sulk(生气愠怒)(四)名词Marionette(牵线木偶)Nimble (敏捷的)Engaging(迷人的)翻译技巧:整篇文章主要翻译难题是句子的比喻意义很难说明白,只能联系上下文自己琢磨。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

英译汉(文学翻译)The work Joyce produced in Portrait of the Artist, his Kunstlerroman, his formative novel, is not without ambivalence. In one of the first scenes, he who will become the artist is in open opposition to the law and to authority. We have to look at the word "law" and render it more flexible. We have to analyze who lays down the law and who is in the law's place. In this respect, there is a difference between Joyce and Kafka. In Kafka, the law is not figured by anyone. In Joyce there are specific authorities. In the first page of his novel, the women threaten him with castration but, as in Clarice Lispector, the question of the father is important too. In Clarice's "Sunday, before falling asleep," the father is really a father/mother and everything is organized in the direction of the father. Genesis takes place in a maternal and paternal mode of production. In Joyce, something analogous is related to the very possibility of the formation of the artist. Which father produces the artist? The question is related to the superego. Yet it is not always the same self that has a repressive figure.The first two pages of Portrait of the Artist can be approached through a kind of multiple reading, which is what Joycean writing asks for. We read word for word, line by line, but at the same time it has to be read —because that is how it is written —as a kind of embryonic scene. The entire book is contained in the first pages, which constitute a nuclear passage. The ensemble of Joyce's work is here like an egg or an opaque shell of calcium. An innocent reading will lead us to believe that these pages are hermetic. One understands everything and nothing; everything because there is really nothing obscure, nothing because there are many referents. Perhaps Irish people would find it more accessible, at least if they know their history well. Here, we have something of a coup d'ecriture, with many signs of the ruse of the artist. The text is presented in an apparent naivete —like Clarice's "Sunday, before falling asleep"— but nothing is more condensed, or more allusive. It is already a cosmos.Joyce denied using psychoanalysis in his work, yet he was impregnated by it. It is as if Joyce, though writing when Freud's texts were not yet well known, was in a kind of intellectual echo with him.The story of A Portrait of the Artist is both that of a portrait being made and that of a finished portrait. The title indicates this kind of permanent duplicity. The reader is told that it is the portrait of an artist, not of a young man, which raises the question of the self-portrait of the artist, of the coming and going of the look, of the self, of the mirror and the self in the mirror.A Portrait of the Artist is a genesis, like Clarice's text. But hers was a genesis as much of the artist as of the world, and the artist-world relation went through that of father-daughter. In Portrait of the Artist, one first sees a series of births, inscribed through the motif of evasion, of flight, and that is how the artist is made. The first and the fifth chapters resemble each other most. In those chapters, writing is much more disseminated, dislocated, than in the others. The successive stories of birth are stories of the breaking of an eggshell, in relation with a parental structure. In the first scene, there is a kind of elementary kinship structure. The scene opens little by little. In this story of the eye and of birds, not the real but the symbolic father marks the artist as genetic parent.The text begins with an enormous O that recurs in the first pages. It can be taken as a feminine, masculine, or neuter sign, as zero. The o is everywhere. One can work on the o-a, on the fort-da. I insist on the graphic and phonic o's because the text tells me to do so. With all its italics and its typography, the text asks the reader to listen. There is also a series of poems. The last one, with its system of inversions and inclusions and exclusions, ends in an apotheosis with "apologise."In these two pages we have everything needed to make a world and its history, in particular that of the artist. The text begins with: ' 'Once upon a time . . . baby tuckoo" (3). We are in the animal world. / begins with a moocow. Daedalus constructed his maze not without relation to a cow. It was built to contain the Minotaurus, the child of a (false) cow. We are in the labyrinth. There is no sexual hesitation and the first structure puts Oedipus in place. A cow and a little boy form a dual structure. We go on rapidly to the formation of the subject through the intervention of a third term. We go through the history of the mirror stage and of the cleavage, which is much funnier in Joyce than in Lacan.In "His father told him that story:" the colon and the organization of the sentence arc important since they speak at all levels. "His father looked at him through a glass:" a window separates without separating. With mirror and glasses we are already in the complex space of the history of blindness and of identificatory images. His father told him this story. The reader waits to hear what the father thinks but at that very moment the father is seen: "He had a hairy face." This is brought about by the father's look cast upon the boy. We are reminded of Kafka's keeper of the law, who was also said to have a hairy face. Our first perception of the father focuses on the glasses and on hair."He was baby tuckoo": not cuckoo, but tuckoo, a failed bird linked through its double o to the moocow that is walking down the road. His song falls from the sky, in the guise of a failed phonic signifier.We go on to a succession of personal pronouns and adjectives:' 'His mother put on the oilsheet." She functions as an anal mother. She is at the center of a moment of corporeal perceptions: cold, warm, wet, smell. The bottom of the body and the odor are feminine but the mother is on the side of a certain orality as well.。