2007ESH高血压指南-PPT课件

ESH高血压指南

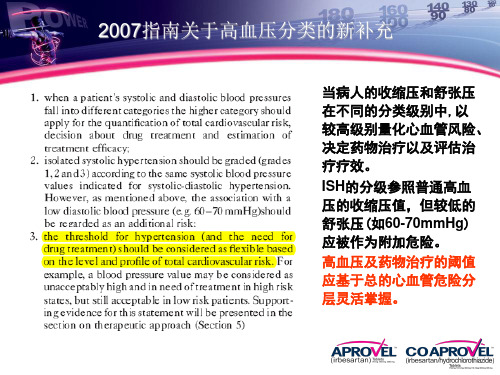

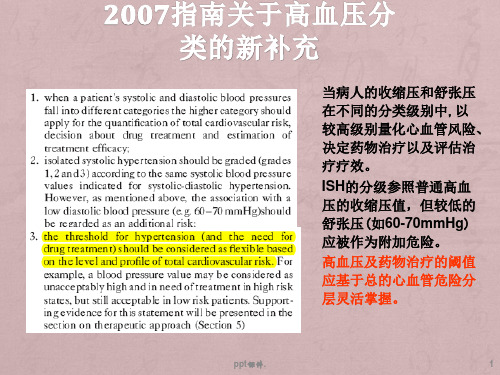

当病人的收缩压和舒张压 在不同的分类级别中,以 较高级别量化心血管风险、 决定药物治疗以及评估治 疗疗效。 ISH的分级参照普通高血 压的收缩压值,但较低的 舒张压(如60-70mmHg) 应被作为附加危险。 高血压及药物治疗的阈值 应基于总的心血管危险分 层灵活掌握。

抗高血压药物的降压幅度

• 疗效:354个试验的荟萃分析 • 不同剂量的药物和安慰剂相比的血压降低(mmHg)

一半剂量

标准剂量

加倍剂量

Thiazide BB CCB ACEI ARB

7.4/3.7 7.4/5.6 5.9/3.9 6.9/3.7 7.8/4.5

8.8/4.4 9.2/6.7 8.8/5.9 8.5/4.7 10.3/5.7

肾病高血压患者的降压治疗

2007指南中的肾脏损害 已不仅仅指糖尿病肾病。 为了延缓肾病进程需要满 足两个条件:a)严格控制 血压<130/80mmHg或更 低;b)尽可能将尿蛋白降 至正常。

为了达到降压目标,肾病 高血压患者通常需要联合 应用多种降压药物。

2007 ESH指南小结

• 再次强调在高血压诊断、治疗中应综合考虑总心血管风 险的评估 • 糖尿病、靶器官损害、肾病显著增加高血压患者的心血 管风险

5

10

15 时间(小时)

20

25

30

Mazzolai L et al. Hypertension. 1999; 33: 850-5.

与双倍剂量氯沙坦比较: 安博维的降压作用更强

安博维与氯沙坦降压作用比较(收缩压)

0

不 同 时 间 (点 血 压 )的 平 均 变 化 -3 -6 -9 -12 -15 -18 -21 0 1 2 3 4 时间(周) 5 6 7 8

2007 ESC高血压指南

ESC and ESH Guidelines2007Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertensionThe Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH)and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Authors/Task Force Members:Giuseppe Mancia,Co-Chairperson (Italy),Guy De Backer ,Co-Chairperson (Belgium),Anna Dominiczak (UK),Renata Cifkova (Czech Republic)Robert Fagard (Belgium),Giuseppe Germano (Italy),Guido Grassi (Italy),Anthony M.Heagerty (UK),Sverre E.Kjeldsen (Norway),Stephane Laurent (France),Krzysztof Narkiewicz (Poland),Luis Ruilope (Spain),Andrzej Rynkiewicz (Poland),Roland E.Schmieder (Germany),Harry A.J.Struijker Boudier (Netherlands),Alberto Zanchetti (Italy)ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG):Alec Vahanian,Chairperson (France),John Camm (United Kingdom),Raffaele De Caterina (Italy),Veronica Dean (France),Kenneth Dickstein (Norway),Gerasimos Filippatos (Greece),Christian Funck-Brentano (France),Irene Hellemans (Netherlands),Steen Dalby Kristensen (Denmark),Keith McGregor (France),Udo Sechtem (Germany),Sigmund Silber (Germany),Michal Tendera (Poland),Petr Widimsky (Czech Republic),Jose Luis Zamorano (Spain)ESH Scientific Council:Sverre E.Kjeldsen,President (Norway),Serap Erdine,Vice-President (Turkey),Krzysztof Narkiewicz,Secretary (Poland),Wolfgang Kiowski,Treasurer (Switzerland),Enrico Agabiti-Rosei (Italy),Ettore Ambrosioni (Italy),Renata Cifkova (Czech Republic),Anna Dominiczak (United Kingdom),Robert Fagard (Belgium),Anthony M.Heagerty,Stephane Laurent (France),Lars H.Lindholm (Sweden),Giuseppe Mancia (Italy),Athanasios Manolis (Greece),Peter M.Nilsson (Sweden),Josep Redon (Spain),Roland E.Schmieder (Germany),Harry A.J.Struijker-Boudier (The Netherlands),Margus Viigimaa (Estonia)Document Reviewers:Gerasimos Filippatos (CPG Review Coordinator)(Greece),Stamatis Adamopoulos (Greece),Enrico Agabiti-Rosei (Italy),Ettore Ambrosioni (Italy),Vicente Bertomeu (Spain),Denis Clement (Belgium),Serap Erdine (Turkey),Csaba Farsang (Hungary),Dan Gaita (Romania),Wolfgang Kiowski (Switzerland),Gregory Lip (UK),Jean-Michel Mallion (France),Athanasios J.Manolis (Greece),Peter M.Nilsson (Sweden),Eoin O’Brien (Ireland),Piotr Ponikowski (Poland),Josep Redon (Spain),Frank Ruschitzka (Switzerland),Juan Tamargo (Spain),Pieter van Zwieten (Netherlands),Margus Viigimaa (Estonia),Bernard Waeber (Switzerland),Bryan Williams (UK),Jose Luis Zamorano(Spain)The content of these European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Guidelines has been published for personal and educational use only.No commercial use is authorized.No part of the ESC Guidelines may be translated or reproduced in any form without written permission from the ESC.Permission can be obtained upon submission of a written request to Oxford University Press,the publisher of the European Heart Journal and the party authorized to handle such permissions on behalf of the ESC.Disclaimer.The ESC Guidelines represent the views of the ESC and were arrived at after careful consideration of the available evidence at the time they were written.Health professionals are encouraged to take them fully into account when exercising their clinical judgement.The guidelines do not,however ,override the individual responsibility of health professionals to make appropriate decisions in the circumstances of the individual patients,in consultation with that patient,and where appropriate and necessary the patient’s guardian or carer.It is also the health professional’s responsibility to verify the rules and regulations applicable to drugs and devices at the time of prescription.The affiliations of Task Force members are listed in the Appendix.Their Disclosure forms are available on the respective society Web Sites.These guidelines also appear in the Journal of Hypertension ,doi:10.1097/HJH.0b013e3281fc975a *Correspondence to Giuseppe Mancia,Clinica Medica,Ospedale San Gerardo,Universita Milano-Bicocca,Via Pergolesi,33–20052MONZA (Milano),Italy Tel:þ390392333357;fax:þ39039322274,e-mail:giuseppe.mancia@unimib.it*Correspondence to Guy de Backer ,Dept.of Public Health,University Hospital,De Pintelaan 185,9000Ghent,Belgium Tel:þ3292403627;fax:þ3292404994;e-mail:Guy.DeBacker@ugent.beEuropean Heart Journal (2007)28,1462–1536doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehm236&2007The European Society of Cardiology (ESC)and European Society of Hypertension (ESH).All rights reserved.For Permissions,pleasee-mail:journals.permissions@Table of Contents1.Introduction and purposes (1463)2.Definition and classification of hypertension (1464)2.1Systolic versus diastolic and pulse pressure..14642.2Classification of hypertension (1465)2.3Total cardiovascular risk (1465)2.3.1Concept (1465)2.3.2Assessment (1466)2.3.3Limitations (1468)3.Diagnostic evaluation (1469)3.1Blood pressure measurement (1469)3.1.1Office or clinic blood pressure (1469)3.1.2Ambulatory blood pressure (1469)3.1.3Home blood pressure (1471)3.1.4Isolated office or white coat hypertension14713.1.5Isolated ambulatory or maskedhypertension (1472)3.1.6Blood pressure during exercise andlaboratory stress (1472)3.1.7Central blood pressure (1473)3.2Family and clinical history (1473)3.3Physical examination (1473)3.4Laboratory investigations (1473)3.5Genetic analysis (1474)3.6Searching for subclinical organ damage (1475)3.6.1Heart (1476)3.6.2Blood vessels (1476)3.6.3Kidney (1477)3.6.4Fundoscopy (1478)3.6.5Brain (1478)4.Evidence for therapeutic management of hypertension14784.1Introduction (1478)4.2Event based trials comparing active treatmentto placebo (1479)4.3Event based trials comparing more and lessintense blood pressure lowering (1480)4.4Event based trials comparing different activetreatments (1480)4.4.1Calcium antagonists versus thiazidediuretics and b-blockers (1480)4.4.2ACE inhibitors versus thiazide diureticsand b-blockers (1480)4.4.3ACE inhibitors versus calciumantagonists (1480)4.4.4Angiotensin receptor antagonists versusother drugs (1481)4.4.5Trials with b-blockers (1481)4.4.6Conclusions (1482)4.5Randomized trials based on intermediateendpoints (1482)4.5.1Heart (1482)4.5.2Arterial wall and atherosclerosis (1483)4.5.3Brain and cognitive function (1484)4.5.4Renal function and disease (1484)4.5.5New onset diabetes (1485)5.Therapeutic approach (1486)5.1When to initiate antihypertensive treatment.14865.2Goals of treatment (1487)5.2.1Blood pressure target in the generalhypertensive population (1487)5.2.2Blood pressure targets in diabetic andvery high or high risk patients (1488)5.2.3Home and ambulatory blood pressuretargets (1489)5.2.4Conclusions (1489)5.3Cost-effectiveness of antihypertensivetreatment (1489)6.Treatment strategies (1490)6.1Lifestyle changes (1490)6.1.1Smoking cessation (1490)6.1.2Moderation of alcohol consumption (1490)6.1.3Sodium restriction (1491)6.1.4Other dietary changes (1491)6.1.5Weight reduction (1491)6.1.6Physical exercise (1491)6.2Pharmacological therapy (1492)6.2.1Choice of antihypertensive drugs (1492)6.2.2Monotherapy (1495)6.2.3Combination treatment (1495)7.Therapeutic approach in special conditions (1497)7.1Elderly (1497)7.2Diabetes mellitus (1498)7.3Cerebrovascular disease (1499)7.3.1Stroke and transient ischaemic attacks.14997.3.2Cognitive dysfunction and dementia..15007.4Coronary heart disease and heart failure (1500)7.5Atrialfibrillation (1501)7.6Non-diabetic renal disease (1501)7.7Hypertension in women (1502)7.7.1Oral contraceptives (1502)7.7.2Hormone replacement therapy (1503)7.7.3Hypertension in pregnancy (1503)7.8Metabolic syndrome (1504)7.9Resistant hypertension (1506)7.10Hypertensive emergencies (1507)7.11Malignant hypertension (1507)8.Treatment of associated risk factors (1508)8.1Lipid lowering agents (1508)8.2Antiplatelet therapy (1509)8.3Glycaemic control (1509)9.Screening and treatment of secondary forms ofhypertension (1510)9.1Renal parenchymal disease (1510)9.2Renovascular hypertension (1510)9.3Phaeochromocytoma (1511)9.4Primary aldosteronism (1511)9.5Cushing’s syndrome (1512)9.6Obstructive sleep apnoea (1512)9.7Coarctation of the aorta (1512)9.8Drug-induced hypertension (1512)10.Follow-up (1512)11.Implementation of guidelines (1513)APPENDIX (1514)References (1515)1.Introduction and purposesFor several years the European Society of Hypertension (ESH)and the European Society of Cardiology(ESC) decided not to produce their own guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of hypertension but to endorse the guidelines on hypertension issued by the World Health Organization (WHO)and International Society of Hypertension(ISH)1,2with some adaptation to reflect the situation in Europe. However,in2003the decision was taken to publish ESH/ ESC specific guidelines3based on the fact that,because the WHO/ISH Guidelines address countries widely varying in the extent of their health care and availability of economic resource,they contain diagnostic and therapeutic recommendations that may be not totally appropriate for European countries.In Europe care provisions may often allow a more in-depth diagnostic assessment of cardiovascu-lar risk and organ damage of hypertensive individuals as well as a wider choice of antihypertensive treatment.The2003ESH/ESC Guidelines3were well received by the clinical world and have been the most widely quoted paper in the medical literature in the last two years.4However, since2003considerable additional evidence on important issues related to diagnostic and treatment approaches to hypertension has become available and therefore updating of the previous guidelines has been found advisable.In preparing the new guidelines the Committee estab-lished by the ESH and ESC has agreed to adhere to the prin-ciples informing the2003Guidelines,namely1)to try to offer the best available and most balanced recommendation to all health care providers involved in the management of hypertension,2)to address this aim again by an extensive and critical review of the data accompanied by a series of boxes where specific recommendations are given,as well as by a concise set of practice recommendations to be pub-lished soon thereafter as already done in2003;53)to pri-marily consider data from large randomized trials but also to make use,where necessary,of observational studies and other sources of data,provided they were obtained in studies meeting a high scientific standard;4)to emphasize that guidelines deal with medical conditions in general and therefore their role must be educational and not prescrip-tive or coercive for the management of individual patients who may differ widely in their personal,medical and cul-tural characteristics,thus requiring decisions different from the average ones recommended by guidelines;5)to avoid a rigid classification of recommendations by the level or strength of scientific evidence.6The Committee felt that this is often difficult to apply,that it can only apply to therapeutic aspects and that the strength of a rec-ommendation can be judged from the way it is formulated and from reference to relevant studies.Nevertheless,the contribution of randomized trials,observational studies, meta-analyses and critical reviews or expert opinions has been identified in the text and in the reference list.The members of the Guidelines Committee established by the ESH and ESC have participated independently in the preparation of this document,drawing on their academic and clinical experience and applying an objective and criti-cal examination of all available literature.Most have under-taken and are undertaking work in collaboration with industry and governmental or private health providers (research studies,teaching conferences,consultation),but all believe such activities have not influenced their judge-ment.The best guarantee of their independence is in the quality of their past and current scientific work.However, to ensure openness,their relations with industry,govern-ment and private health providers are reported in the ESH and ESC websites( and www.escardio. org)Expenses for the Writing Committee and preparation of these guidelines were provided entirely by ESH and ESC.2.Definition and classification of hypertension Historically more emphasis was placed on diastolic than on systolic blood pressure as a predictor of cardiovascular morbid and fatal events.7This was reflected in the early guidelines of the Joint National Committee which did not consider systolic blood pressure and isolated systolic hyper-tension in the classification of hypertension.8,9It was reflected further in the design of early randomized clinical trials which almost invariably based patient recruitment cri-teria on diastolic blood pressure values.10However,a large number of observational studies has demonstrated that car-diovascular morbidity and mortality bear a continuous relationship with both systolic and diastolic blood press-ures.7,11The relationship has been reported to be less steep for coronary events than for stroke which has thus been labelled as the most important‘hypertension related’complication.7However,in several regions of Europe,though not in all of them,the attributable risk, that is the excess of death due to an elevated blood pressure,is greater for coronary events than for stroke because heart disease remains the most common cardiovas-cular disorder in these regions.12Furthermore,both systolic and diastolic blood pressures show a graded independent relationship with heart failure,peripheral artery disease and end stage renal disease.13–16Therefore,hypertension should be considered a major risk factor for an array of car-diovascular and related diseases as well as for diseases leading to a marked increase in cardiovascular risk.This, and the wide prevalence of high blood pressure in the popu-lation,17–19explain why in a WHO report high blood pressure has been listed as thefirst cause of death worldwide.20 2.1Systolic versus diastolic and pulse pressureIn recent years the simple direct relationship of cardiovascu-lar risk with systolic and diastolic blood pressure has been made more complicated by thefindings of observational studies that in elderly individuals the risk is directly pro-portional to systolic blood pressure and,for any given systolic level,outcome is inversely proportional to diastolic blood pressure,21–23with a strong predictive value of pulse pressure (systolic minus diastolic).24–27The predictive value of pulse pressure may vary with the clinical characteristics of the sub-jects.In the largest meta-analysis of observational data avail-able today(61studies in almost1million subjects without overt cardiovascular disease,of which70%are from Europe)11both systolic and diastolic blood pressures were independently and similarly predictive of stroke and coronary mortality,and the contribution of pulse pressure was small, particularly in individuals aged less than55years.By con-trast,in middle aged24,25and elderly26,27hypertensive patients with cardiovascular risk factors or associated clinical conditions,pulse pressure showed a strong predictive value for cardiovascular events.24–27It should be recognized that pulse pressure is a derived measure which combines the imperfection of the original measures.Furthermore,althoughfigures such as50or 55mmHg have been suggested,28no practical cutoff values separating pulse pressure normality from abnormality at different ages have been produced.As discussed in section 3.1.7central pulse pressure,which takes into account the ‘amplification phenomena’between the peripheral arteriesand the aorta,is a more precise assessment and may improve on these limitations.In practice,classification of hypertension and risk assess-ment(see sections2.2and2.3)should continue to be based on systolic and diastolic blood pressures.This should be defi-nitely the case for decisions concerning the blood pressure threshold and goal for treatment,as these have been the criteria employed in randomized controlled trials on isolated systolic and systolic-diastolic hypertension.However,pulse pressure may be used to identify elderly patients with systo-lic hypertension who are at a particularly high risk.In these patients a high pulse pressure is a marker of a pronounced increase of large artery stiffness and therefore advanced organ damage28(see section3.6).2.2Classification of hypertensionBlood pressure has a unimodal distribution in the population29 as well as a continuous relationship with cardiovascular risk down to systolic and diastolic levels of115–110mmHg and 75–70mmHg,respectively.7,11This fact makes the word hypertension scientifically questionable and its classification based on cutoff values arbitrary.However,changes of a widely known and accepted terminology may generate con-fusion while use of cutoff values simplifies diagnostic and treatment approaches in daily practice.Therefore the classi-fication of hypertension used in the2003ESH/ESC Guidelines has been retained(T able1)with the following provisos:1.when a patient’s systolic and diastolic blood pressuresfall into different categories the higher category should apply for the quantification of total cardiovascular risk, decision about drug treatment and estimation of treat-ment efficacy;2.isolated systolic hypertension should be graded(grades1,2and3)according to the same systolic blood pressure values indicated for systolic-diastolic hypertension.However,as mentioned above,the association with a low diastolic blood pressure(e.g.60–70mmHg)should be regarded as an additional risk;3.the threshold for hypertension(and the need for drugtreatment)should be considered asflexible based on the level and profile of total cardiovascular risk.Forexample,a blood pressure value may be considered as unacceptably high and in need of treatment in high risk states,but still acceptable in low risk patients.Support-ing evidence for this statement will be presented in the section on therapeutic approach(Section5).The USA Joint National Committee Guidelines(JNC7)on hypertension published in200330unified the normal and high normal blood pressure categories into a single entity termed‘prehypertension’.This was based on the evidence from the Framingham study31,32that in such individuals the chance of developing hypertension is higher than in those with a blood pressure,120/80mmHg(termed‘normal’blood pressure)at all ages.The ESH/ESC Committee has decided not to use this terminology for the following reasons:1)even in the Framingham study the risk of develop-ing hypertension was definitely higher in subjects with high normal(130–139/85–89mmHg)than in those with normal blood pressure(120–129/80–84mmHg)32,33and therefore there is little reason to join the two groups together;2) given the ominous significance of the word hypertension for the layman,the term‘prehypertension’may create anxiety and request for unnecessary medical visits and examinations in many subjects;343)most importantly,although lifestyle changes recommended by the2003JNC7Guidelines for all prehypertensive individuals may be a valuable population strategy,30in practice this category is a highly differentiated one,with the extremes consisting of subjects in no need of any intervention(e.g.an elderly individual with a blood pressure of120/80mmHg)as well as of those with a very high or high risk profile(e.g.after stroke or with diabetes) in whom drug treatment is required.In conclusion,it might be appropriate to use a classification of blood pressure without the term‘hypertension’.However, this has been retained in T able1for practical reasons and with the reservation that the real threshold for hypertension must be considered asflexible,being higher or lower based on the total cardiovascular risk of each individual.This is further illustrated in section2.3and in Figure1.2.3T otal cardiovascular risk(Box1)2.3.1ConceptFor a long time,hypertension guidelines focused on blood pressure values as the only or main variables determining the need and the type of treatment.Although this approach was maintained in the2003JNC7Guidelines,30the2003 ESH-ESC Guidelines3emphasized that diagnosis and manage-ment of hypertension should be related to quantification of total(or global)cardiovascular risk.This concept is based on the fact that only a small fraction of the hypertensive population has an elevation of blood pressure alone,with the great majority exhibiting additional cardiovascular risk factors,35–39with a relationship between the severity of the blood pressure elevation and that of alterations in glucose and lipid metabolism.40Furthermore,when concomitantly present,blood pressure and metabolic risk factors potentiate each other,leading to a total cardiovascular risk which is greater than the sum of its individual components.35,41,42 Finally,evidence is available that in high risk individuals thresholds and goals for antihypertensive treatment,as well as other treatment strategies,should be different from those to be implemented in lower risk individuals.3In orderTable1Definitions and classification of blood pressure(BP) levels(mmHg)Category Systolic Diastolic Optimal,120and,80 Normal120–129and/or80–84 High normal130–139and/or85–89 Grade1hypertension140–159and/or90–99 Grade2hypertension160–179and/or100–109 Grade3hypertension 180and/or 110 Isolated systolichypertension140and,90Isolated systolic hypertension should be graded(1,2,3)according to systolic blood pressure values in the ranges indicated,provided that dias-tolic values are,90mmHg.Grades1,2and3correspond to classification in mild,moderate and severe hypertension,respectively.These terms have been now omitted to avoid confusion with quantification of total cardiovascular risk.to maximize cost-efficacy of the management of hyperten-sion the intensity of the therapeutic approach should be graded as a function of total cardiovascular risk.43,442.3.2AssessmentEstimation of total cardiovascular risk is simple in particular subgroups of patients such as those with 1)a previous diag-nosis of cardiovascular disease,2)type 2diabetes,3)type 1diabetes,and 4)individuals with severely elevated single risk factors.In all these conditions the total cardiovascular risk is high,calling for the intense cardiovascular risk redu-cing measures that will be outlined in the following sections.However ,a large number of hypertensive patients does not belong to one of the above categories and identification of those at high risk requires the use of models to estimate total cardiovascular risk so as to be able to adjust the inten-sity of the therapeutic approach accordingly.Several computerized methods have been developed for estimating total cardiovascular risk,i.e.the absolute chance of having a cardiovascular event usually over 10years.However ,some of them are based on Framingham data 45which are only applicable to some European popu-lations due to important differences in the incidence of cor-onary and stroke events.12More recently ,a European model has become available based on the large data-base provided by the SCORE project.46SCORE charts are available for high and low risk countries in Europe.They estimate the risk of dying from cardiovascular (not just coronary)disease over 10years and allow calibration of the charts for individual countries provided that national mortality statistics and esti-mates of the prevalence of major cardiovascular risk factors are known.The SCORE model has also been used in the Heart-Score,the official ESC management tool for implementation of cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice.This is available on the ESC Web Site ().The 2003ESH/ESC Guidelines 3classified the total cardio-vascular risk based on the scheme proposed by the 1999WHO/ISH Guidelines on hypertension 2with the extension to subjects with ‘normal’or ‘high normal’blood pressure.This classification is retained in the present Guidelines (Figure 1).The terms ‘low’,‘moderate’,‘high’and ‘very high’risk are used to indicate an approximate risk of cardi-ovascular morbidity and mortality in the coming 10years,which is somewhat analogous to the increasing level of total cardiovascular risk estimated by the Framingham 45or the SCORE 46models.The term ‘added’is used to emphasize that in all categories relative risk is greater than average risk.Although use of a categorical classification provides data that are in principle less precise than thoseobtainedFigure 1Stratification of CV Risk in four categories.SBP:systolic blood pressure;DBP:diastolic blood pressure;CV:cardiovascular;HT:hypertension.Low,moderate,high and very high risk refer to 10year risk of a CV fatal or non-fatal event.The term ‘added’indicates that in all categories risk is greater than average.OD:subclinical organ damage;MS:metabolic syndrome.The dashed line indicates how definition of hypertension may be variable,depending on the level of total CV risk.Box 1Position statement:Total cardiovascularrisk†Dysmetabolic risk factors and subclinical organ damage are common in hypertensive patients.†All patients should be classified not only in relation to the grades of hypertension but also in terms of the total cardiovascular risk resulting from the coexistence of different risk factors,organ damage and disease.†Decisions on treatment strategies (initiation of drug treatment,BP threshold and target for treatment,use of combination treatment,need of a statin and other non-antihypertensive drugs)all importantly depend on the initial level of risk.†There are several methods by which total cardiovascular risk can be assessed,all with advantages and limitations.Categorization of total risk as low,moderate,high,and very high added risk has the merit of simplicity and can therefore be recommended.The term ‘added risk’refers to the risk additional to the average one.†Total risk is usually expressed as the absolute risk of having a cardiovascular event within 10years.Because of its heavy dependence on age,in young patients absolute total cardiovascular risk can be low even in the presence of high BP with additional risk factors.If insufficiently treated,however ,this con-dition may lead to a partly irreversible high risk con-dition years later .In younger subjects treatment decisions should better be guided by quantification of relative risk,i.e.the increase in risk in relation to average risk in the population.from equations based on continuous variables,this approach has the merit of simplicity.The2003WHO/ISH Guidelines47 have further simplified the approach by merging the high and very high risk categories which were regarded as similar when it came to making treatment decisions.The distinction between high and very high risk categories has been maintained in the present guidelines,thereby preser-ving a separate place for secondary prevention,i.e.preven-tion in patients with established cardiovascular disease.In these patients,compared with the high risk category,not only can total risk be much higher,but multidrug treatment may be necessary throughout the blood pressure range from normal to high.The dashed line drawn in Figure1illustrates how total cardiovascular risk evaluation influences the defi-nition of hypertension when this is correctly considered as the blood pressure value above which treatment does more good than harm.48Table2indicates the most common clinical variables that should be used to stratify the risk.They are based on risk factors(demographics,anthropometrics,family history of premature cardiovascular disease,blood pressure,smoking habits,glucose and lipid variables),measures of target organ damage,and diagnosis of diabetes and associated clinical conditions as outlined in the2003Guidelines.3The following new points should be highlighted:1.The metabolic syndrome49has been mentioned becauseit represents a cluster of risk factors often associated with high blood pressure which markedly increases car-diovascular risk.No implication is made that it rep-resents a pathogenetic entity.2.Further emphasis has been given to identification oftarget organ damage,since hypertension-related subcli-nical alterations in several organs indicate progression in the cardiovascular disease continuum50which mark-edly increases the risk beyond that caused by the simple presence of risk factors.A separate Section(3.6)is devoted to searching for subclinical organdamage where evidence for the additional risk of each subclinical alteration is discussed and the proposed cutoff values are justified.Table2Factors influencing prognosisRisk factors Subclinical organ damage†Systolic and diastolic BP levels†Electrocardiographic L VH(Sokolow-Lyon.38mm;Cornell.2440mm*ms)or:†Levels of pulse pressure(in the elderly)†Echocardiographic L VH8(L VMI M 125g/m2,W 110g/m2)†Age(M.55years;W.65years)†Carotid wall thickening(IMT.0.9mm)or plaque†Smoking†Carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity.12m/s†Dyslipidaemia†Ankle/brachial BP index,0.9-TC.5.0mmol/l(190mg/dl)or:†Slight increase in plasma creatinine:-LDL-C.3.0mmol/l(115mg/dl)or:M:115–133m mol/l(1.3–1.5mg/dl);-HDL-C:M,1.0mmol/l(40mg/dl),W,1.2mmol/l(46mg/dl)or:W:107–124m mol/l(1.2–1.4mg/dl)-TG.1.7mmol/l(150mg/dl)†Low estimated glomerularfiltration rate†(,60ml/min/1.73m2)or creatinine clearance S(,60ml/min)†Fasting plasma glucose5.6–6.9mmol/L(102–125mg/dl)†Microalbuminuria30–300mg/24h or albumin-creatinine ratio:22(M);or 31(W)mg/g creatinine†Abnormal glucose tolerance test†Abdominal obesity(Waist circumference.102cm(M),.88cm(W))†Family history of premature CV disease(M at age,55years;W at age,65years)Diabetes mellitus Established CV or renal disease†Fasting plasma glucose 7.0mmol/l(126mg/dl)on repeated measurements,or †Cerebrovascular disease:ischaemic stroke;cerebral haemorrhage;transient ischaemic attack†Postload plasma glucose.11.0mmol/l(198mg/dl)†Heart disease:myocardial infarction;angina;coronaryrevascularization;heart failure†Renal disease:diabetic nephropathy;renal impairment(serumcreatinine M.133,W.124mmol/l);proteinuria(.300mg/24h)†Peripheral artery disease†Advanced retinopathy:haemorrhages or exudates,papilloedema Note:the cluster of three out of5risk factors among abdominalobesity,altered fasting plasma glucose,BP.130/85mmHg,lowHDL-cholesterol and high TG(as defined above)indicates thepresence of metabolic syndromeM:men;W:women;CV:cardiovascular disease;IMT:intima-media thickness;BP:blood pressure;TG:triglycerides;C:cholesterol;S Cockroft Gault formula;†MDRD formula;8Risk maximal for concentric L VH(left ventricular hypertrophy):increased L VMI(left ventricular mass index)with a wall thick-ness/radius ratio.0.42.。

ESH高血压指南ppt课件

+ 为了更加积极、有效地干预,高危与极度高危的患 者应灵活调整启动降压治疗的阈值,尽早治疗,更 多获益

+ 各类降压药物都能通过降低血压给患者带来保护作 用,但RAS阻断剂对糖尿病、肾病患者具有额外的 保护作用,应将其作为优先选择,或作为联合治疗 的组成部分

ppt课件.

21

安博维四大特点

降血压 心脏保护 降蛋白尿,肾功能保护 PPARγ作用

ppt课件.

22

安博维更出色地抑制外源性AngⅡ引起的收缩压反应

100

收

缩 80

压

对

外 源

60

性

40

的 反 应 20

0 0

* *

++ +

5

10

+ *

*

*

++ +

* 与安慰剂比较,p<0.01 + 与安慰剂比较,p<0.05 ++ 与氯沙坦或缬沙坦比较,p<0.05

ppt课件.

18

降低血压对肾脏损害的发 生及进程具有有益的保护 作用,但是RAS阻断剂具 有额外的保护作用,应该 成为联合治疗的常规组成 药物,如果是单药治疗也 是比较理想的选择。

MAU阳性的患者应该立 即启动药物治疗,即使起 始血压尚在正常高值。 RAS阻断剂具有理想的降 蛋白作用,是一个理想的 选择。

8.0

5.5

Valsartan

7.5

4.0

Irbesartan

10.0

6.5

Telmisartan

9.5

6.0

Candesartan 10.0

6.0

Conlin PR, et al. J Clin Hypertens. 2000;2:p2p5t课3件-2.57

高血压概述PPT课件

1

原发性高血压

原发性高血压(primary hypertension)是 以血压升高为主要临床表现伴或不伴有多种心 血管危险因素的综合征,通常简称为高血压。

高血压是多种心、脑血管疾病的重要病因和危

险因素,影响重要脏器,如心、脑、肾的结构

与功能,最终导致这些器官的功能衰竭,迄今

仍是心血管疾病死亡的主要原因。

舒张压(mmHg)

JNC-7

降压治疗可减少心脑血管事件的发生

脑卒中 事件发生率降低(%)

0 -10 -20 -30 -40 -50 -60

心肌梗死

心衰

下降35-40%

下降20-25%

下降>50%

JNC-7

第三部分

高血压的流行病学

高血压的危害

高血压的分类和风险分层

高血压的病因及发病机制

临床事件

中风史 心肌梗塞史 心绞痛 心力衰竭 心房颤动(复发) 心房颤动(永久) 肾功能衰竭/蛋白尿 外周动脉疾病

其他情况

单纯收缩期高血压(老年) 代谢综合征 糖尿病 妊娠 黑色人种

指南强调联合治疗

“强调首选某种药物进行降压的观念已经过时,因为大多数 患者都需要2种或更多的药物来使血压降到目标水平”

细胞膜离子 转运异常

胰岛素抵抗

第五部分

高血压的流行病学

高血压的危害

高血压的分类和风险分层

高血压的病因及发病机制

高血压的临床表现及并发症

高血压的诊断及治疗

17

高血压的临床表现

症状

头晕、头痛、颈项板 紧、疲劳、心悸等; 也可出现视力模糊、 鼻出血等

最新欧洲高血压指南教学讲义ppt课件

130-135

夜间血压

120

家庭自测血压 130-135

舒张压mmHg

90 80 85 70 85

靶器官亚临床损害的筛选方法

• 心脏:心电图应作为高血压患者的常规检查之 一,可以用于左心室肥厚、缺血和心律失常的 检测;超声心动图是更敏感的检查左心室肥大 的方法;血流多普勒可用于舒张功能下降的评 估工具

2007年欧洲高血压指 南

高血压定义与分类

• 血压在人群中呈单峰分布,与心血管危 险之间存在连续相关性。

• 在日常实践中常使用“高血压”一词。 然而,定义高血压的真正阈值是灵活的, 根据总的心血管危险或高或低。

《2007欧洲高血压防治指南》血压分级

分类

收缩压(mmHg)

理想血压

<120

正常血压

120-129

• 心率加快被认为是高血压危险因素之一,心率 加快与心血管死亡和全因死亡率相关,心率加 快还与新发现高血压、代谢紊乱以及代谢综合 征相关

• 高血压甚至正常高值的患者合并多种危险因素、 糖尿病或确诊的器官损害,则这些患者为高危 人群

高度/极高度危险高血压病患者

• BP>180/110mmHg • SBP>160mmHg 以及DBP<70mmHg • 糖尿病 • 代谢综合征 • >=3个心血管危险因素 • >=1个靶器官损伤 • 心电图(特别是兼有劳损)或超声心动图(特别是向心 性)检测左心室肥

• 血管:颈动脉超声扫描是检测血管壁厚度和非 对称性动脉粥样硬化的有效方法;脉搏波传导 速度是大动脉僵硬的预测指标;踝-肘血压指数 的下降意味着外周动脉疾病的进展。

靶器官亚临床损害的筛选方法

• 肾脏:高血压相关的肾损害诊断基于肾功能的 下降和尿蛋白排泄率的升高,因此肾小球滤过 率和肌酐清除率应作为常规检查,而且对所有 高血压患者都应检测尿蛋白

2007ESH、ESC高血压诊疗指南解读

高血压的诊断和治疗-解读《 2007年ESH / ESC高血压诊断和治疗指南》1.《2007 ESH / ESC高血压诊断与治疗指南》中对高血压的诊断(1)明确血压水平1.高血压的定义和分类血压在人群中呈现出单峰分布,并且血压与心血管风险之间存在持续的相关性。

定义高血压的真正阈值是灵活的,并取决于总的心血管风险。

血压水平的定义和分类如下:注意:血压mmhg,ISH(DBP <90mmHg)应根据SBP值进行分级(1、2、3)2.评估总心血管风险所有患者不仅应根据高血压的分类进行分类,还应根据心血管总风险进行分类。

治疗方案的选择基于初始风险水平;建议将总风险分为低风险,中风险,高风险和极端增加;总危险度通常表示为10年内发生心血管事件的绝对危险度,对于年轻患者,以相对危险度(即与人群的平均危险度相比增加的程度)指导治疗可能会更好;不建议对绝对风险阈值进行严格的定义。

心血管疾病的总危险分层如下:血压mmHg注意事项:SBP:收缩压;DBP:舒张压;简历:心血管;HT:高血压;OD:亚临床器官损伤;MS:代谢综合征3. 24小时动态血压监测(ABPM)尽管诊断是基于办公室血压,但ABPM可以改善患者的CV风险预测。

在以下情况下,您应该考虑使用ABPM:(一)办公室血压变化很大;(2)总体简历风险低,诊所血压高;(3)家庭自测血压与办公室血压之间存在显着差异;(4)药物疗效差;(5)怀疑有低血压,尤其是在老年患者和糖尿病患者中;(6)孕妇办公室的血压升高,怀疑是先兆子痫。

4.家庭自测血压应鼓励家人自己测量血压,这可以提供有关在低谷水平进行降压治疗的有效性以及在给药间隔期间进行治疗的更多信息;提高患者对治疗的依从性;了解测量技术的可靠性和动态血压数据的可用性测量环境;当家庭自测血压导致患者焦虑时,应予以禁止;指导患者自行调整治疗方案。

5.根据不同的测量方法定义高血压的血压阈值(mmHg)(2)查明高血压的继发原因1.体格检查提示继发性高血压和器官损伤的迹象,例如腹部听诊时发出杂音,提示肾血管性高血压;提示器官损伤的迹象,例如颈动脉收缩期杂音;内脏肥胖的证据,例如体重,腰围增加,体重指数(BMI)增加。

2007 ESH ESC高血压诊疗指南之高血压的治疗

改变生活方式, 改变生活方式+ 持续数周后,若 立即药物治疗 血压未得到控制, 则开始药物治疗 改变生活方式, 改变生活方式+ 持续数周后,若 立即药物治疗 血压未得到控制, 则开始药物治疗 改变生活方式+ 药物治疗 改变生活方式+ 立即药物治疗

1-2 个危险因素

改变生活方式

改变生活方式

≥ 3个危险因素, 代谢综合征 (MS), OD或 MS 糖尿病

单药治疗与联合治疗

• 固定联用2种药物可简化治疗,提高依从性。 • 若患者在联用2种药物后血压仍未得到控制,则需要联用3 种或3种以上的药物。 • 在无并发症的高血压患者和老年人中,通常应逐渐降压。 而在高危高血压患者中,应将血压快速降至目标水平,起 始治疗最好选择联合用药并快速调整剂量。

单药治疗与联合治疗策略

糖尿病患者的降压治疗

• 肾素-血管紧张素系统阻滞剂应为联合治疗的常规组分, 若此类药物单药治疗即可达标,则首选此疗法。 • 出现微量白蛋白尿以及最初血压在正常高值范围内的患者 应使用降压药物治疗。 • 肾素-血管紧张素系统阻滞剂具有明显的减低尿蛋白的效 应,应为首选药物。 • 治疗方案中应考虑针对所有心血管危险因素的干预措施, 包括使用他汀类药物。 • 因为患者发生体位性低血压的可能性较大,所以也应在直 立位时测量血压。

•

•

各种降压药物的适应证之比较

噻嗪类利尿剂 β-阻滞剂 钙拮抗剂 (二氢吡啶类)

单纯收缩期高血压 (老 年人) 心绞痛

钙拮抗剂 (维拉帕米/地尔硫卓)

心绞痛

单纯收缩期高血压 (老年人) 心衰

心绞痛

心肌梗死后

颈动脉粥样硬化

黑人高血压

心衰

LVH

室上性心动过速

ESHESC高血压治疗指南(2007版)-ARB临床应用的适应症PPT课件

2003 JNC7

降压达标减少心脑血管事件的发生

中风事件

35-45%

心肌梗死

20-25%

心力衰竭

>50%

LVH: 卒中渐进性危险因素

脑血管事件累计发生率 %

脑血管事件每百人年发生率

35 心电图

3 35 超声心动图

3

30

LVH+

30

25

2.04 2

25

2

20

P=0.0001

20

LVH+

1.50

LVH-

执行委员会

主席:

共同主席:

B. Dahlöf

R. B. Devereux

1. Dahlöf B et al. Lancet 2002;359:995-1003.

18

ARB的试验证据

LIFE

前瞻性、双盲、活性药物对照、 9193名合并左心室肥厚的高血压患者, 平均4.8年随访周期 随访44,119病人年 7个国家的945个研究中心 1096患者到达首要终点

* Defined as >160/<90 mmHg

LIFE: 设计/剂量调整

* 调整剂量至达到目标血压: <140 / 90 mmHg

氯沙坦 100 mg + 氢氯噻嗪 12.5-25 mg + 其他**

氯沙坦 100 mg + 氢氯噻嗪 12.5 mg*

氯沙坦 50 mg + 氢氯噻嗪 12.5 mg*

Yr Yr Yr Yr Yr Yr 2 2.5 3 3.5 4 5

Dahlöf B et al Am J Hypertens 1997; 10: 705713.

LIFE: 相似的降压效果

2007ESC高血压指南

20000

ARB

15000

ACEI β-Blocker

10000

5000

Others

0

40 7

41 0

50 1

50 4

50 7

51 0

60 1

60 4

60 7

61 0

70 1 '0

'0

'0

'0

'0

'0

'0

'0

'0

'0

'0

'0

70 4

广州市抗高血压市场的现状

8000 7000 6000

Norvasc

果来自于其降压作用

B.个体化用药,根据心血管危险/靶器官损伤程

度,选择用药

C.联合用药

降压治疗:2003→2007首选药物

一:器官的亚临床损害的治疗

药物 左室肥厚 无症状性动脉粥样硬化 微量蛋白尿 ARB、ACEI、CCB CCB、ACEI ARB、ACEI

肾功能障碍

ARB、ACEI

降压治疗:2003 → 2007首选药物

07与03版比较不同点

二、治疗:

A.降压达标,降压药物80%-90%左右保护效

果来自于其降压作用

B.个体化用药,根据心血管危险/靶器官损伤程

度,选择用药

C.联合用药

降压治疗降低心脑血管死亡风险

• 61个前瞻性观察研究的荟萃分析 • 研究共入选100万成年患者

• 共1270万病人年

IHD死亡风险 下降30% SBP平均下 降10 mmHg

07与03版比较不同点

一、诊断:增加了三种检测手段

高血压指南讲座课件课件

运动频率与时间

每周进行至少150分钟的中等强度有 氧运动,或75分钟的高强度有氧运 动。

运动注意事项

运动时应避免剧烈运动,避免在极端 天气条件下运动,如有需要可咨询医 生。

04 高血压药物治疗

药物治疗原则

长期性原则

高血压需要长期治疗,不可随意 停药,即使血压控制理想。

个体化原则

根据患者的具体情况,制定个体 化的治疗方案。

综合性治疗原则

药物治疗的同时,还需注意改善 生活方式,如控制体重、减少盐

的摄入、戒烟限酒等。

常用降压药物

利尿剂

通过排除体内多余的水和盐,降低血压。

β受体拮抗剂

通过降低心脏的收缩力和心率来降低血压。

ACE抑制剂

通过抑制产生收缩的激素来降低血压。

Angiotensin II 受体拮抗剂

高血压指南讲座课件

目录

Contents

• 高血压概述 • 高血压的成因 • 高血压的预防与控制 • 高血压药物治疗 • 非药物治疗 • 高血压并发症的预防与控制

01 高动脉血压升高为 主要特征,可伴有心、脑、肾等器官 的功能或器质性损害的临床综合征。

预防措施

保持血压在正常范围内,定期进行眼科检查,控制血糖、血脂等危 险因素。

控制方法

一旦发生视网膜病变,需要及时就医,接受专业治疗和管理,包括 药物治疗、激光治疗和手术等。

THANKS

生活事件

遭遇重大生活事件,如亲 人过世、离婚等,也可能 引发高血压。

焦虑和抑郁情绪

长期焦虑、抑郁等情绪问 题也可能导致血压升高, 增加高血压的患病风险。

03 高血压的预防与控制

定期检测血压

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

安博维®抑制AT1的作用更强更持久

安博维更出色地抑制外源性AngⅡ引起的收缩压反应

100 收 缩 压 对 外 源 性 AngII 的 反 应 80

*

* *

+

60

*

* ++ + 安慰剂 氯沙坦50mg 缬沙坦80mg 安博维150mg

40

20 0 0

++ +

* 与安慰剂比较,p<0.01 + 与安慰剂比较,p<0.05 ++ 与氯沙坦或缬沙坦比较,p<0.05

Telmisartan

Candesartan源自9.510.06.0

6.0

Conlin PR, et al. J Clin Hypertens. 2000;2:253-257

特定情况下ARB的治疗益处

ARB对降低左心室肥 大、降低房颤发生特 别有效,同时还能有 效降低MAU和尿蛋白、 保存肾脏功能、延缓 肾病进程。

ARB是糖尿病患者的理想降压药物

降低血压对肾脏损害的发 生及进程具有有益的保护 作用,但是RAS阻断剂具 有额外的保护作用,应该 成为联合治疗的常规组成 药物,如果是单药治疗也 是比较理想的选择。

MAU阳性的患者应该立 即启动药物治疗,即使起 始血压尚在正常高值。 RAS阻断剂具有理想的降 蛋白作用,是一个理想的 选择。

2019 ESH Guidelines

让伴有高危因素高血压患者尽早达标!

2019 指南对心血管危险分层 有何修改或补充?

2019指南再次强调了心血管风险评估

高血压的诊断和治疗应该 结合总心血管风险的量化 评估。

大部分高血压患者都伴有 其它的心血管危险因素。 血压升高的严重程度与血 糖、血脂的变化相关,当 高血压与代谢危险因素合 并存在时,心血管风险的 增加超过了两者单独的累 加。

随机比较试验显示,在血 压下降相似的前提下,各 类降压药物心血管事件发 生率和死亡率差异细微, 因而再次强调高血压治疗 益处主要来自于降压本身。 近期Meta分析都指出了降 压对除心衰之外所有事件 影响的重要性,无论使用 那一类药物,当SBP下降 10mmHg,中风和冠脉事 件都显著下降。

高危/极高危患者及时启动药物治疗

抗高血压药物的降压幅度

• 疗效:354个试验的荟萃分析 • 不同剂量的药物和安慰剂相比的血压降低(mmHg)

一半剂量

标准剂量

加倍剂量

Thiazide BB CCB ACEI ARB

7.4/3.7 7.4/5.6 5.9/3.9 6.9/3.7 7.8/4.5

8.8/4.4 9.2/6.7 8.8/5.9 8.5/4.7 10.3/5.7

选择哪类药物作为首选是无益的

高血压治疗益处主要来自 于降压本身,每类药物都 能显著降低血压从而降低 心血管事件。 且大部分患者都需要一种 以上药物的联合治疗。因 此,强调那类药物应作为 首选治疗的药物是无益的 但证据也显示,在某些情 况下,一些药物好于另一 些药物,并因而成为优先 选择或联合治疗的一部分。

10.3/5.0 11.1/7.8 11.7/7.9 10.0/5.7 12.3/6.5

Wald NJ et al. BMJ. 2019; 326: 1419.

ARBs 降压疗效的荟萃分析 (43项研究, 11281例)

SBP(mmHg) DBP(mmHg)

Losartan Valsartan Irbesartan 8.0 7.5 10.0 5.5 4.0 6.5

• 为了更加积极、有效地干预,高危与极度高危的患者应 灵活调整启动降压治疗的阈值,尽早治疗,更多获益

• 各类降压药物都能通过降低血压给患者带来保护作用, 但RAS阻断剂对糖尿病、肾病患者具有额外的保护作用, 应将其作为优先选择,或作为联合治疗的组成部分

安博维四大特点

降血压 心脏保护 降蛋白尿,肾功能保护 PPARγ作用

2019指南对心血管风险评估的补充

2019指南对心血管风险评估的补充

MS

2019指南对心血管风险评估的补充

OD

糖尿病和靶器官损害增加心血管风险

高危/极高危患者

糖尿病

亚临床靶器官损害

2019指南对心血管风险评估的补充

肾病

MAU成为靶器官损害的常规检测项目

微量白蛋白尿(MAU)与 心血管疾病发生率的增加 相关,并且使患者发生临 床大量蛋白尿的风险增加。

糖尿病 肾病

启动药物 治疗

启动药物 治疗

2019指南关于高血压治疗目标的补充

新指南强调了不仅糖尿病 病人,而且诸如伴有中风、 心梗、肾功能不全以及蛋 白尿的高危或极高危患者, 其目标血压都应 <130/80mmHg。 尽管采用联合治疗,使血 压<140mmHg并不容易, <130 mmHg则更为困难, 尤其是在老年、糖尿病以 及伴有心血管损害的患者。

5

10

15 时间(小时)

20

25

30

Mazzolai L et al. Hypertension. 2019; 33: 850-5.

与双倍剂量氯沙坦比较: 安博维的降压作用更强

MAU的筛查应该考虑作 为所有高血压病人的常规 检查,同样也应该在代谢 综合征患者、甚至血压为 正常高值的患者中进行。

2019指南对心血管风险评估的补充

心血管病

2019 ESH Guidelines

让伴有高危因素高血压患者尽早达标!

2019 指南 高血压的治疗

再次强调:高血压治疗益处来自于降压本身

2019 ESH/ESC Guidelines

让伴有高危因素高血压患者 尽早达标!

2019指南关于高血压分类的新补充

当病人的收缩压和舒张压 在不同的分类级别中,以 较高级别量化心血管风险、 决定药物治疗以及评估治 疗疗效。 ISH的分级参照普通高血 压的收缩压值,但较低的 舒张压(如60-70mmHg) 应被作为附加危险。 高血压及药物治疗的阈值 应基于总的心血管危险分 层灵活掌握。

肾病高血压患者的降压治疗

2019指南中的肾脏损害 已不仅仅指糖尿病肾病。 为了延缓肾病进程需要满 足两个条件:a)严格控制 血压<130/80mmHg或更 低;b)尽可能将尿蛋白降 至正常。

为了达到降压目标,肾病 高血压患者通常需要联合 应用多种降压药物。

2019 ESH指南小结

• 再次强调在高血压诊断、治疗中应综合考虑总心血管风 险的评估 • 糖尿病、靶器官损害、肾病显著增加高血压患者的心血 管风险